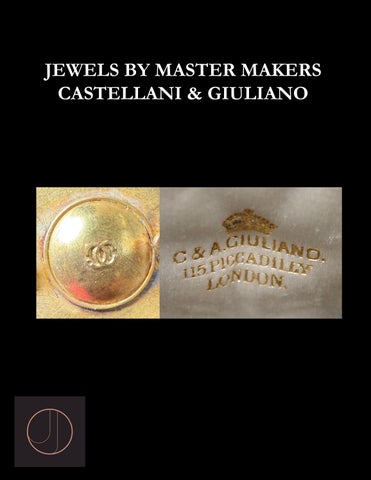

JEWELS BY MASTER MAKERS

CASTELLANI & GIULIANO

Although Fortunato Pio Castellani was based in Rome and hence generally considered the father of classical archaeological revival style in the mid 19th century, the firm experimented in various other styles from the past, including Byzantine, Renaissance, Baroque and, indeed, Egyptian. Cameos and scarabs of previous ages were often incorporated in Castellani’s creations adhering to a faithful rendering of the original form, while subtly enriching with novel and original details.

This gold, steatite and faience scarab and micromosaic necklace and brooch dating around 1860, are brilliant and rare examples of Castellani’s interpretation of Egyptian revival.

The necklace is set with 15 scarabs swivel mounted within gold frames decorated with multicoloured micromosaics of geometric design. The brooch is mounted with a scarab depicting Babi, the Egyptian baboon god, flanked by a pair of wings set with multicoloured mosaics and is an interpretation of the ubiquitous winged scarab dynastic jewels which were stitched to the wrapping over the chest of the mummies.

This Egyptian winged scarab consists of three pieces: an actual scarab beetle and two separately made wings. The wings are not those of a beetle, but those of a bird, as is apparent by their shape and the indication of individual feathers. Each piece features several small holes that were used to fasten the winged scarab to the wrappings of a mummy. Winged scarabs, meant to guarantee the rebirth of the deceased, were very popular funerary amulets | Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The concept of the winged scarab also fascinated Cartier in the second half of the 1920s and resulted in the creation of a number of this jewels with faience elements taken from their stock of apprêts – the fragments from disassembled jewellery and objects, including ancient items from Persian, Indian, Chinese, and Egyptian art.

Jewelled Scarab Belt Buckle, Cartier, Paris, 1926

The cobalt blue faience scarab flanked by turquoise faience wings, the wings edged by round and baguette diamonds set in platinum and with black enamelled details. Note how the holes through which the scarab would have been stitched to the mummy are camouflaged with cabochon sapphires.

The juxtaposition of cobalt blue and turquoise blue is a favourite and very distinctive colour combination of Cartier jewellery of this period.

In this set of jewels Castellani brilliantly and unexpectedly combines Egyptian scarabs with the Roman technique of micromosaics, an eighteenth-century development of an art that from Greek and Roman times had been used to decorate the floors and walls of villas, palaces and early Christian churches.

Unsurprisingly, jewels of Egyptian inspiration were not nearly as popular in Italy as they were becoming in England, where Carlo Giuliano’s production in this style encountered the favour of a small but select group of customers whose passion for Egyptomania had been growing since the beginning of the century. Its popularity in England was partly due to the tireless efforts of Miss Amelia Edwards, founder of the Egyptian Exploration Fund, who was responsible for bringing a large number of antiquities to London, including many scarabs which were collected and mounted by Carlo Giuliano.

A mysterious and intriguing enamel and gem-set bangle by Carlo Giuliano, circa 1870. The jewel is a veritable eclectic mix of myriad influences from popularised Egyptian to Hellenistic. Egyptian art had begun to influence the repertoire of decorative arts in the early 19th century. Jewellers, however, did not become sensitive to this theme until the 1860s. Indeed, it was not until after the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris that the Egyptian style became widely fashionable.

The French jeweller Baugrand’s showcase at the 1867 Universal Exhibition, Paris, is emblematic of the impact that the fascination with Egypt had on the decorative arts. Note the statue of Isis and the Egyptian style casket, and the tiara decorated with lotus motifs, showing on the next page

The elements which played the most important role in the promotion of Egyptian art and of the Egyptian Revival were the publication of Auguste Mariette’s papers on his excavation in Egypt in the 1850s and the arrival at Louvre Museum of the large collection of artefacts he had unearthed in that area.

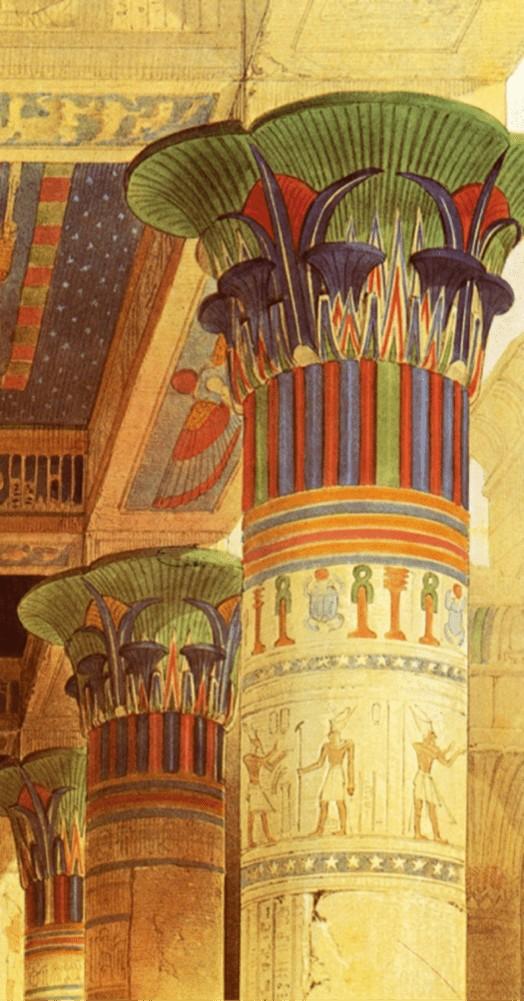

David Roberts, Egypt and Nubia, 1846-49, ‘Grand portico of the Temple of Philae’

Another event that played an important role in the Egyptian focus of the period, was the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 to much international celebration and press attention. Egyptian themes and motifs infiltrated the design and production of all the major European jewellers at this time. Among them, Froment Meurice, Mellerio and Boucheron in Paris; Robert Phillips and Carlo Giuliano in London; and, to a lesser degree, Castellani and Pierret in Rome. These creations were mainly pastiches of pharaonic motifs, unlike the meticulous accuracy of the Greek Archaeological Revival jewels mastered by Castellani and Melillo which were based on genuine archaeological examples.

David Roberts, lithograph, ‘Portico of the Temple of Dendera’, the colourful rendering of the columns’ capitals may well have inspired Giuliano’s creation

This splendidly eccentric, quirky and eclectic jewel created by Carlo Giuliano probably around 1880, is a pastiche of Renaissance motifs combined with others drawn from the esoteric symbolism of the Western Mystery Schools.

Giuliano's gold and enamel gem-set brooch, decorated with the figure of Venus enamelled en ronde bosse, holding a diamond-set mirror and wearing a draped enamelled wrap, under a canopy set with diamonds

The veiled figure of Venus, holding a diamond-set mirror, is drawn directly from mid 16th century iconography as seen in engravings such as those of Virgil Solis and jewels and precious objects in the style of Erasmus Hornick, which were inspirational to other 19th century revivalist jewellers such as Lucien Falize.

Erasmus Hornick (circa 1520-1583), design for a ewer, etching, 1565, from a series of eighteen designs for vases and goblets. The relief is decorated with sea gods and creatures and in the centre Venus is depicted riding two dolphins | Image: Metropolitan Museum of New York

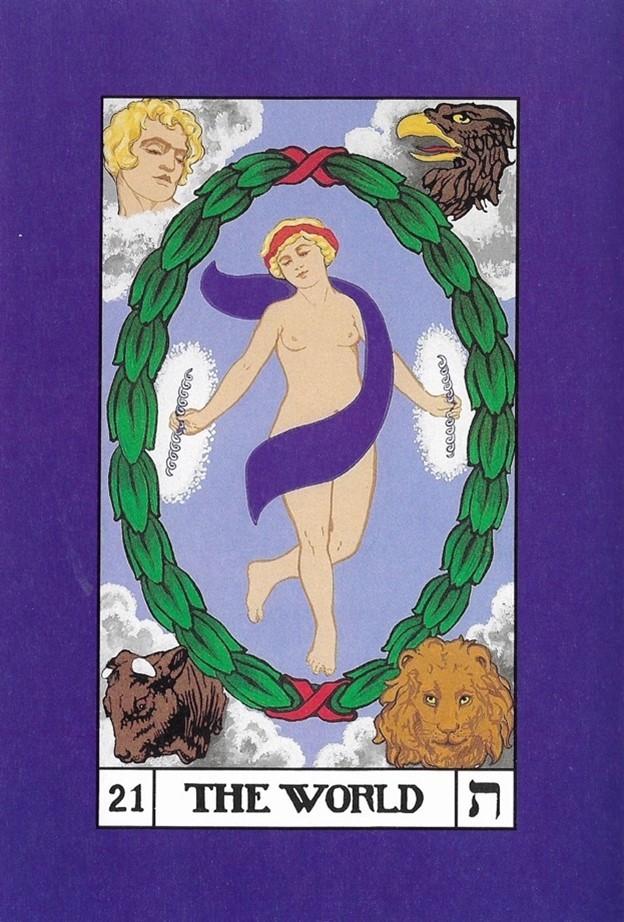

The symbolism, however, is also closely related to the ‘World’, the twenty-second card of The Major Arcana of Tarot. The tarot pack enjoyed renewed interest from the mid-19th century onwards throughout Europe, under the influence of the writings of Eliphas Levi (1810-1875), the French writer.

Lucien Falize (1839-1897), Fortuna pendant, late 19th century

Levi was a widely read and celebrated French esotericist and magician, who was responsible for sparking off the revival of interest in ceremonial magic in Europe and yet was much misunderstood in his day. He is remembered today for his pioneering occult writings and illuminating aphorisms:

‘Nothing can resist the will of man when he knows what is true and wills what is good’.

The World, the twenty-first card of The Major Arcana, the cartomantic tarot pack, from the BOTA deck

We believe it is perfectly possible that this unusual jewel was commissioned by a high grade initiate of one of the important secret esoteric societies such as the Golden Dawn in London which counted among its members, William Butler Yeats, Florence Beatrice Farr and William Wynn Westcott.

This very fine gold brooch by Castellani, circa 1880, is decorated with a micromosaic depicting the head of Medusa, probably made by Luigi Podio who oversaw the Castellani mosaic workshop in Rome between 1851 and 1888. Micromosaic started to be developed in the Vatican mosaic workshop towards the end of the 18th century. The size of the smalti, the small multicoloured glass tesserae or blocks, was minute – in the best examples up to 5000 per square inch. Painstakingly arranged with tweezers the design enhanced with gold and silver filaments.

Note the gold filaments picking out the outlines of the snakes surrounding the features of Medusa Castellani was not alone in employing fine mosaics in jewellery, in fact they had for some time been used for the inevitable jewellery souvenirs so popular with tourists at the beginning of the 19th century, decorated with romantic views of the Campagna Romana and archaeological ruins. However, Castellani is generally accredited with the return to technical excellency and classical subject matter as in this example.

The rendering of the head of Medusa, however, is more indebted to the sensuous, tormented interpretation of Bernini rather than the to the frightening and aggressive apotropaic interpretation of the Classical World.

Marble bust of Medusa, attributed to Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), circa 1638-48 | Capitoline Museums, Rome

This is an outstanding revival jewel by the great master of the genre in the 19th century, Castellani, dating from the 1890s.

Micromosaic brooch with griffin, Castellani, in gold and glass tesserae With its simple outline and bold chromatic scheme, this is one of Castellani’s most powerful and intriguing jewels, and one of our personal favourites. Although this brooch is realised in micromosaic, it reminds us of gold and cloisonné enamel Byzantine medallions depicting religious subjects. In fact, the source of inspiration here is a Byzantine brooch of the 8th or 9th century AD now in the

Louvre Museum, decorated with an enamelled mythological beast at the centre of a gold disk. Generally faithful to the originals, in this case Castellani substitutes the subtle hues of the enamel work with a brightly coloured micromosaic decoration.

Cloisonné medallion with griffin, Byzantine, 8-9th centuries AD, in gold and cloisonné enamel | Campana Collection, Louvre Museum, Paris

These Byzantine gold and cloisonné medallion of Christ, the Virgin and St Peter dating from around 1100AD are from a group of twelve that once surrounded an icon of the archangel Gabriel | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Castellani played an important role in raising the level of the art of the mosaic above the repetitive banality and coarseness of contemporary production which concentrated almost exclusively on Vedute di Roma for tourist consumption.

Predominantly inspired by early Christian examples from Ravenna and Rome, Castellani’s micromosaics were made under the guidance of Luigi Podio who presided over the mosaic workshop between 1851 and 1888 and guaranteed a consistently outstanding quality of production.