Seeing Chandni Chowk

Introduction – Umesh Gaur

Table of Contents

Seeing Chandni Chowk – Swapna Liddle

Three Lenses, Many Histories: Photographing the Old City – Carol Huh

Chandni Chowk: A Photographer’s Paradise – Umesh Gaur

• The Iconic Markets of Chandni Chowk

• Life on the Streets

• Ancestral Families of Chandni Chowk

• Moving the City: The Human Engines of Old Delhi

• The Living Institutions

• The Living Culinary Heritage

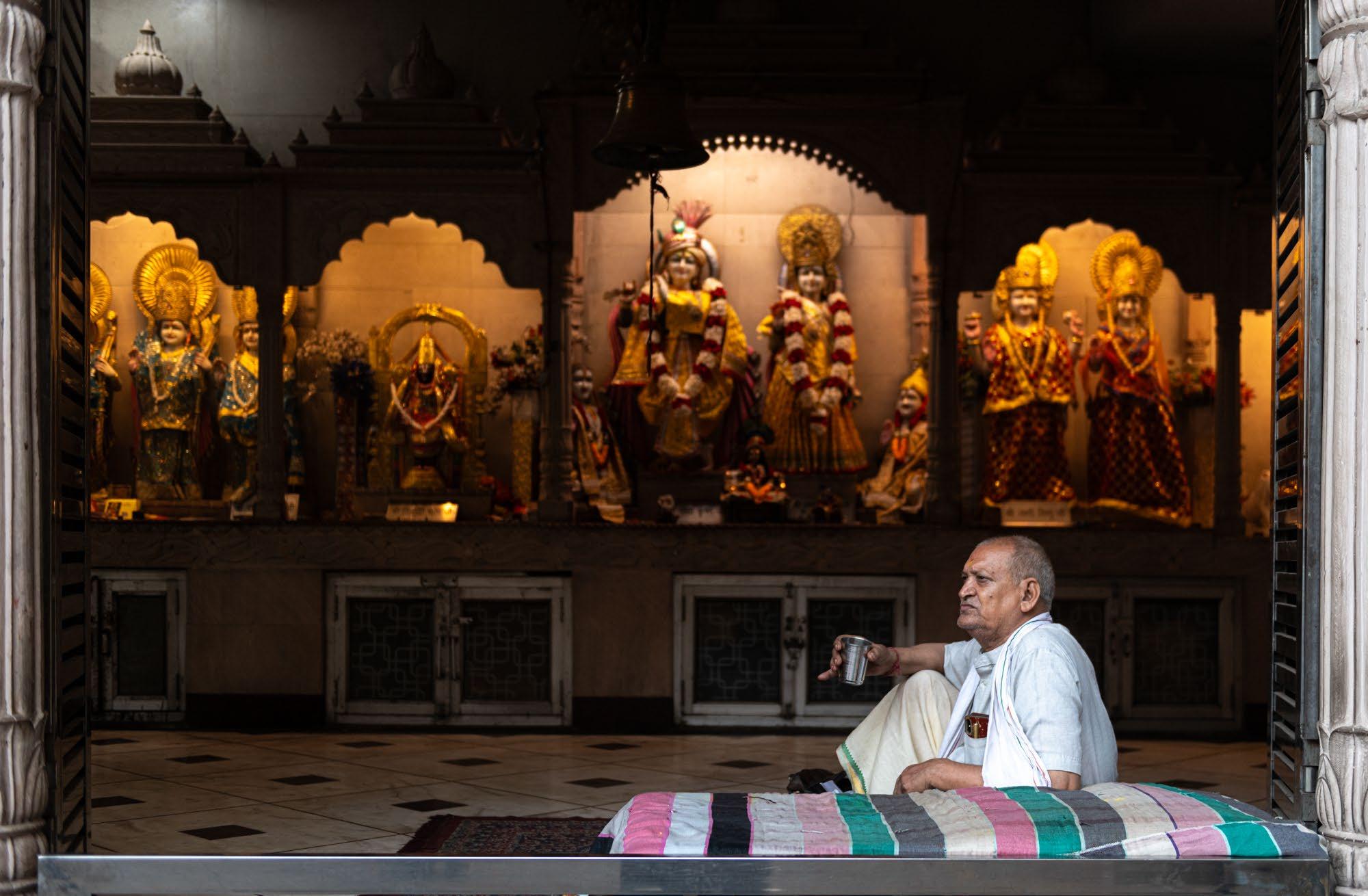

• A Sacred Mosaic: Faith in the Old City

• The Last Keepers of Craft

• Renaissance · Rejuvenation · Resurgence · Revival

Authors and Photographers Biographies

Glossary

Acknowledgements

List of photographs

Introduction

This book is a testament to my enduring love for Chandni Chowk, a place that has been a part of my life for decades. It is not just a place I have photographed; it is where my story begins, a place that holds a special place in my heart.

My mother, Jagrani Gaur, was born in Haveli Haider Quli in Chandni Chowk. My father, Harish Gaur, came from a relatively modest background in a village on the outskirts of Delhi. However, with his hard work and intellect, he rose to become the Dean of the Science Faculty at the University of Delhi, one of India's most prominent universities. He joined the university in the 1950s, during an era when waves of young scholars traveled to the USA for further postdoctoral research. My father went to the University of Illinois for two years. While he was in the US, my sister, mother, and I lived with our grandparents in Chandni Chowk. It was during these years, while walking through the streets of Chandni Chowk and enjoying the street food of Old Delhi, that I formed a lifelong bond rooted in memory, family connections, and enduring love for Chandni Chowk.

My father's love for America and photography was infectious. He brought back with him two cameras, one of which he gave to me. On Sundays, we would venture into Old Delhi together, capturing the essence of Chandni Chowk through our lenses. Under his guidance, I developed a deep love for photography, particularly for Chandni Chowk, a place I have been photographing for over five decades, always finding the poetry of light and shadow in its narrow winding lanes.

Years later, when I read Swapna Liddle’s book on the history of Chandni Chowk, it reignited my interest in revisiting these streets through my camera. I learned a great deal about the history and nuances of Chandni Chowk. At the same time, I realized that a photographic study of this area has never been published. It was this deeply personal encounter that sparked the idea of creating an extended photographic project on Chandni Chowk. What began as a personal response to Swapna's scholarship has now blossomed into this book, which I am honored to coauthor with her. I am deeply grateful for her insight, her generosity, and the wisdom she has brought to this collaboration.

I followed in my father's footsteps and came to America for graduate studies in the 1970s. After obtaining a doctorate, I started working at Johnson & Johnson. After a few years there, I took up an academic position at Princeton. At Princeton, I developed an interest in financial markets, which led to the formation of my asset management firm in the 1990s, which continues to thrive today. Owning my own business allowed me the time and resources to pursue serious photography while traveling worldwide.

It was also around this time that my wife Sunanda and I developed an interest in collecting modern and contemporary Indian art. In the 1990s, auction houses in New York began offering works by senior Indian modernists. Iconic works were coming onto the market, and the collector base was still limited, with few collectors competing for them. Consequently, we were able to rapidly build a significant collection of these works, to the extent that in 2004,

we were named among the "Top 100 Collectors" in America by Arts & Antiques magazine, alphabetically listed just below Bill Gates!

As our collection gained recognition, we began collaborating with museums to organize exhibitions featuring modern and contemporary Indian art. In 2007, I helped organize a major contemporary Indian photography exhibition at the Newark Museum by introducing Paul Sternberger and Gayatri Sinha to the museum, who became the exhibition's curators. Working on this project, we developed an understanding of what makes a photograph a work of art. We learned that art photography transcends representation to evoke emotional and intellectual engagement with the viewer through the interplay of elements such as composition, framing, and lighting. The concepts of gaze, photographic structure, and visual storytelling in a picture became a thrilling discovery. Shortly thereafter, we began adding photography to our growing collection.

One of the first works we acquired was a set of twenty prints by Atul Bhalla based on the Piaus (public water faucets) in Chandni Chowk. As a novice in collecting photography, I reached out to Mary Sue Price, the Director of the Newark Museum at the time, to inquire whether Atul Bhalla's work was included in the upcoming exhibition at the museum. She responded by saying that not only was Atul Bhalla included in the exhibition, but his work was slated to be featured on the cover of the exhibition catalog! This beginner's luck steered us toward building a substantial collection of modern and contemporary Indian photography, which evolved into one of the largest collections of its kind in the US. In 2017, we gifted most of this collection to the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art. Based on our gift, the Smithsonian has organized two exhibitions of contemporary Indian photography, and a third one is currently under development.

Nevertheless, gifting our photographs was somewhat bittersweet. Although we were thrilled that our collection was going to be researched, exhibited, and preserved in the museum, I missed having them at home. My wife gently suggested I print my own photographs. Pulling out my old negatives, however, led to a humbling realization that my own photographs were by no means a match for the works of photography that we had collected and gifted to the Smithsonian. The time had come for me to get some formal photography training.

I started taking courses at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York. After completing a few foundational classes, I enrolled in a travel photography course with Natan Dvir. Natan believed that some of my photographs had strong composition and encouraged me to develop my own project. Inspired by this praise, I took a portraiture course, where I met Harvey Stein. In the first class, Harvey said, "There are two kinds of people in the world those who have been to India and those who have not." I nearly fell out of my chair. I had found my mentor in Harvey, a passionate Indophile who had been photographing in India for many years.

It was through Harvey that I met Margarita Mavromichalis, a Greek photographer who has travelled to India more than twenty-five times. I invited Harvey and Margarita to join me in

photographing in Chandni Chowk. We discovered incredible positive energy between the three of us and have since then visited Chandni Chowk several times together. I'm very grateful for their friendship, guidance, and commitment to this project.

The photographs in this book represent our work over the past decade in Chandni Chowk. During this time, it was also an opportunity for me to relive my childhood memories and connect with the neighborhoods all over again. Some things have changed, but the ambiance in the lanes of Chandni Chowk, the music of street vendors calling out, the kaleidoscope of colors, and the restless energy of its bazaars have remained, just as they were five decades ago.

Nevertheless, the concept of Chandni Chowk, as developed by Jahanara, the daughter of Shah Jahan, in the seventeenth century as an arcade of glamorous trade and intricately built havelis for its affluent residents, is now undergoing a dramatic urban redevelopment. There is now a mall located right in the center of Chandni Chowk. Many traders are moving their businesses to the mall, presenting their merchandise in elaborate showrooms. The mall also features what is now the largest food court in India, as well as several fine-dining restaurants. Dining in an air-conditioned restaurant, however, is no match for a food crawl through the bustling streets of Chandni Chowk while tasting delicious Old Delhi cuisine from decades-old small roadside establishments that serve classic recipes passed down through the

generations. The main road in Chandni Chowk has also been rebuilt, no longer allowing cars during the day. The lack of automotive access is driving many residents to other parts of Delhi, and their havelis are being converted into warehouses at a very rapid pace.

All these developments are dramatically reshaping the character of Chandni Chowk. The dynamics are undeniably shifting. Traditional bazaars, hawker lanes, and generational families now coexist within a modern urban framework. This transformation is bittersweet. While modernization brings much-needed infrastructure, it risks sanitizing the layering, intimacy, and physicality that define Old Delhi. Yet, the soul of Chandni Chowk resides not in its stone façades, but in its timeless spirit. In the midst of modernization, its spirit endures alive, unyielding, luminous as ever.

I hope this book of photographs will help preserve the imagery of Chandni Chowk, so that long after today's dust settles, its voices, its flavors, and its spirit will still be heard, echoing like an unbroken song through the heart of Old Delhi.

Seeing Chandni Chowk

In the night of 29 April 1639, a momentous ceremony took place beside the river Yamuna, just north of a vast ground on which successive cities had been built over the course of several centuries. These cities had been the capitals of dynasties that had claimed imperial status over large parts of the Indian subcontinent, and eventually came to be subsumed under the name ‘Delhi’. On this night the first steps were being taken to take this imperial legacy forward. At a moment decreed auspicious by the royal astrologers, markings began to be drawn on the ground, delineating the foundations of the imperial palace which would form the core of a new city. The city was to be called Shahjahanabad – named after its founder, the Mughal emperor Shahjahan.

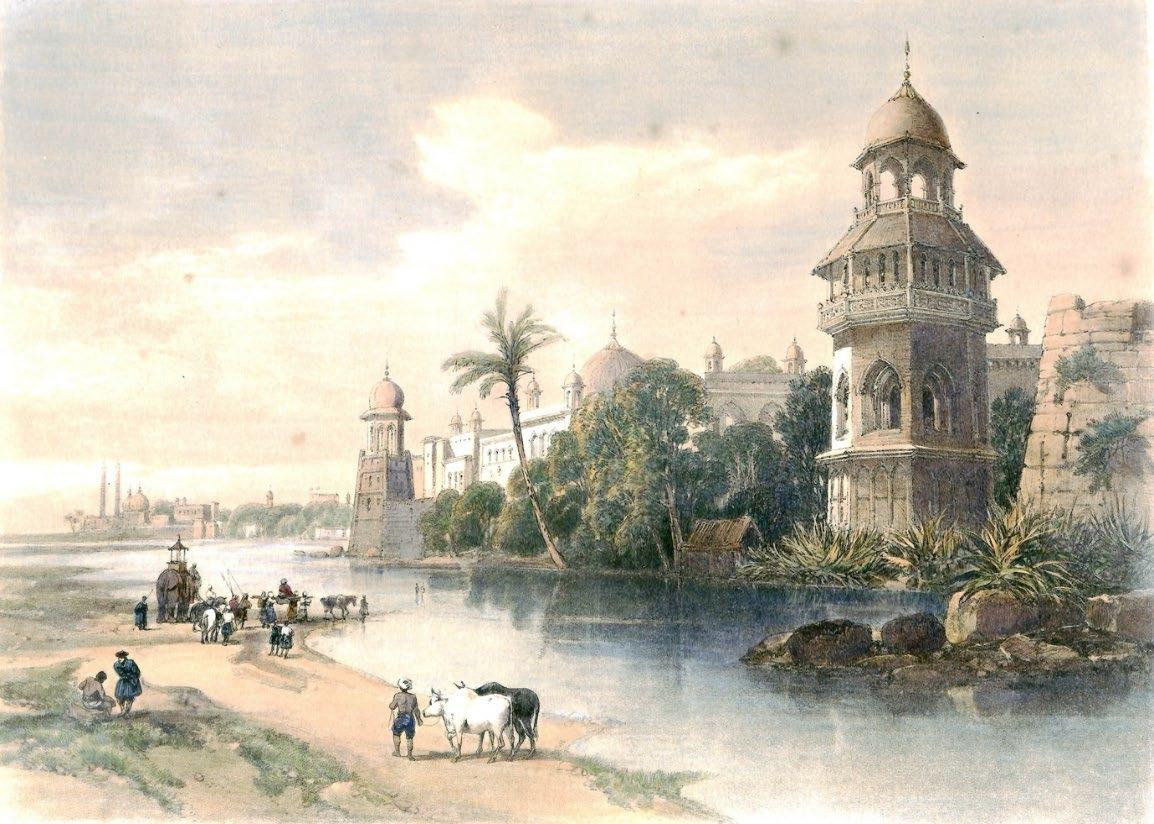

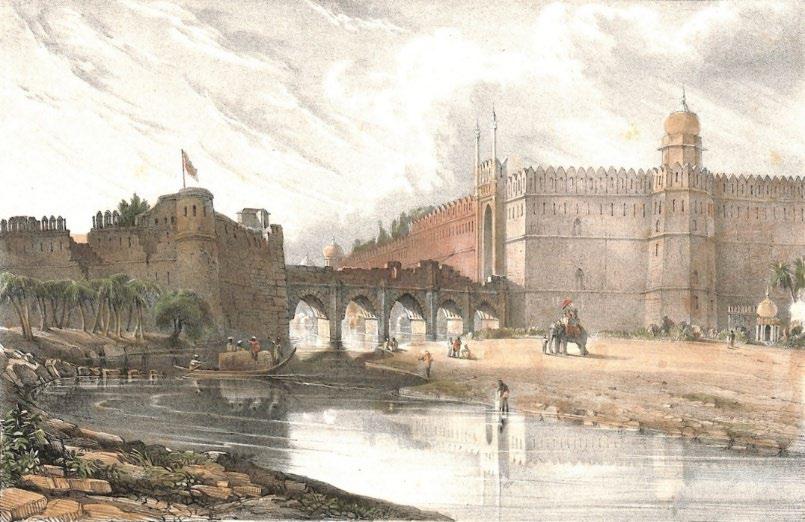

Fig. 1 - A British artist’s conjectural view of the city of Shahjahanabad, drawn in 1858

The ruler of one of the richest and most powerful empires of its time did not just choose a historic spot to build his capital. Shahjahan was the ultimate patron of architecture. The proof of his good taste and ability to marshal talent had already reached an acme in the Taj Mahal, the superlative tomb built over the remains of his chief consort, Mumtaz Mahal. In Shahjahanabad he put to work his most talented architects, Ustad Ahmad and Ustad Hamid, whose work in designing the palace complex he personally supervised. Witness to these events was the court chronicler Inayat Khan, who noted, “skilled artisans were summoned from all parts of the imperial dominions, wherever artificers could be found – whether plain

stone-cutters, ornamental sculptors, masons, or carpenters….and multitudes of common labourers were employed in the work.” 1

The court chroniclers wrote about imperial projects, most notably the palace complex that would later be known as ‘Red Fort’; the congregational mosque or Jama Masjid; and the wall that encircled and protected the city. These grand structures did not only stand as testament to the power, wealth and refinement of the Mughal emperor and the establishment he commanded; they conveyed other powerful messages. So, several of the gates in the city wall took their names from the provinces of the empire they faced – Kashmir, Kabul, Lahore, Ajmer. Everyone in the capital would be reminded that the roads leading from these gates connected far flung regions to the heart of the empire of which they were integral parts.

The decorative schemes within the courts in the palace had messages for the people of this vast realm. In his most intimate court, known as the Khas Mahal, the emperor administered the empire seated under a panel carved with the scales of justice, symbolically projecting him as the fount of justice for all his subjects. In his largest court of audience, known as the Diwan e Aam, his throne was placed under a panel that depicted the Greek god Orpheus playing to the beasts. This conveyed the message that the Mughal empire was one where

1 W.E. Begley and Z. A. Desai, eds., The Shah Jahan Nama of Inayat Khan, translated by A.R. Fuller, Oxford University Press, Delhi 1990, p 407

there was absolute peace, where the strong and the weak were treated equally and none were oppressed. If this did not reflect absolute reality, it at least signalled the ideals espoused by the regime.

Fig. 3 - The Khas Mahal and the panel carved with the scales of justice, under which the Mughal emperor sat

The court and capital of the Emperor attracted people of talent and learning from all around the empire and even from beyond its boundaries; and they were generously patronised. Chandar Bhan Brahman, a secretary in the court of the emperor, described Shahjahan’s interactions with these people in eloquent if somewhat hyperbolic terms:

“Physicians of Greek and Indian medicine present him with summary reports of the success of their skill in administering remedies. Also astronomers, astrologers, superintendents of observatories, calculators of astronomical tables, Brahmins, Pundits, Hindoo versifiers and poets, and others learned in different branches, and professors of every art, discourse on the theory and practice of their several avocations. Likewise limners, painters, mathematicians, and designers, exhibit their different works, and improve by the royal instruction. Professors and teachers in very art and science honestly confess their own ignorance, when compared with his Majesty’s complete and accurate knowledge therein.” 2

The grandeur of the palace complex and its opulent courts was seen by the merchants and diplomats from far and wide who began to visit the new capital soon after it was founded. Some of them have left behind vivid descriptions. The first of these was a Venetian, Niccolao Manucci, who visited Delhi in the 1650s. Manucci was presented at the court of Shahjahan, and in his memoir commented on the grandeur and solemnity of the ceremonial, as well as the opulence of the court – the painted and gilded pillars, the gold and silver railings, the brocade draperies, the precious stone inlays in the marble throne canopy.

Manucci had arrived in India as a young man seeking his fortune and in Delhi had the good fortune of getting employed by the heir apparent at the time, Shahjahan’s oldest son, Dara Shukoh. Other Europeans too flocked to the new capital in search of employment, business opportunities, or just to experience first-hand the magnificence of the ‘Great Mughal’. These included the French physician Francois Bernier, the jewel merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, and the traveller Jean de Thévenot. Each of these described in similar terms the glories of the Mughal court and palace complex, but they have also left behind vivid descriptions of the city of Shahjahanabad and its people.

Fig. 4 - Jean de Thévenot, who travelled to Delhi during the reign of Aurangzeb

Bernier was impressed with the two main streets of the city – one leading southwards from the palace, and the other leading westwards, and compared the buildings in them to the Place Royale of his native Paris:

2 ‘Kowayid us saltanet Shahjehan’, in Francis Gladwin ed. The Persian Moonshee, Calcutta, 1801, p 67

“The two principal streets of the city…may be five-and-twenty or thirty ordinary paces in width. They run in a straight line nearly as far as the eye can reach…In regard to houses the two streets are exactly alike. As in our Place Royale, there are arcades on both sides; with this difference, however, that they are only brick, and that the top serves for a terrace and has no additional building. They also differ from the Place Royale in not having an uninterrupted opening from one to the other, but are generally separated by partitions, in the spaces between which are open shops, where, during the day, artisans work, bankers sit for the despatch of their business, and merchants exhibit their wares. Within the arch is a small door, opening into a warehouse, in which these wares are deposited for the night. The houses of the merchants are built over these warehouses, at the back of the arcades : they look handsome enough from the street, and appear tolerably commodious within; they are airy, at a distance from the dust, and communicate with the terrace-roofs over the shops, on which the inhabitants sleep at night.” 3

These two wide streets were part of the imperial planning of the city, intended as ceremonial avenues ideally suited to the grand processions of the emperor when he emerged from the palace. Down the middle of either of them ran a channel of water, a branch of a canal that had been created to draw water from the river upstream, and carry it to the city, in order that it may run through its streets and gardens. Trees were planted on either side of it to provide shade. One annual royal procession was when the emperor went on the occasion of Eid ud zuha to the Eidgah outside the walls of the city, to perform the ritual sacrifice of a camel. Chandar Bhan Brahman thus described the royal procession on this occasion, as the

emperor and his retinue emerged from the western gate of the Fort, known as the Lahore Gate, and made its way down the long street to the westernmost gate of the city:

“Throughout the city, the doors, walls and shops in the streets and markets are decorated with silken stuffs, of various colours. People innumerable of the city and suburbs are collected together, in houses of three and four storeys, on the edges of roofs, in balconies and galleries, at the same time that all the markets, lanes and streets are thronged by the populace….the monarch…proceeds to the Eidgah on a stately powerful steed, or mounted on an elephant swift as the spheres, and firm as a mountain, whilst abundance of money is flung on all among the populace.” 4

Bernier noted that the other streets of the city were neither so grand nor so symmetrical as these two avenues, and that this was because most of the city was built through individual enterprise at different periods of time. The homes of the rich – nobles, military commanders, administrators, rich merchants and others, were spread through the city, though the highest nobles, including the heir apparent Dara Shukoh, had homes to the north and south of the Red Fort, overlooking the river. To European eyes these houses seemed less grand than the tall stone houses Parisians considered desirable, but Bernier was quick to point out that they were in fact ideally suited to the climate of Delhi. The aim in construction was to have open, airy, spaces. Thus, houses typically did not have many storeys, and were instead spread out around courtyards, and contained gardens with shady trees, fountains, and pools of water.

There were many ways to cope with the hot weather. Many houses had underground apartments, fitted with fans, where the occupants could rest during the hot afternoon. Others had khas khanas, free-standing chambers made largely of woven khas - the aromatic roots of the vetiver grass. These rooms were placed in a garden close to a pool, from which water could be drawn to moisten the walls. The air passing through the porous wall would then cool and scent the interior. For summer nights the houses had terraces on which beds could be laid out, with a large adjoining room where one could retreat in case of sudden rain, a dust storm, or the sudden drop of temperature in the early hours of the morning.

To European eyes the furnishings of these homes were strange too. Bernier recorded: “The interior of a good house has the whole floor covered with a cotton mattress four inches in thickness, over which a fine white cloth is spread during the summer, and a silk carpet in the winter. At the most conspicuous side of the chamber are one or two mattresses, with fine coverings quilted in the form of flowers and ornamented with delicate silk embroidery, interspersed with gold and silver. These are intended for the master of the house, or any person of quality who may happen to call. Each mattress has a large cushion of brocade to lean upon, and there are other cushions placed round the room, covered with brocade, velvet or flowered satin, for the rest of the company. Five or six feet from the floor, the sides of the room are full of niches, cut in a variety of shapes, tasteful and well proportioned, in which are seen porcelain vases and flower-pots. The ceiling is gilt and painted….”. 5 ,

3 Bernier, p 245

4 ‘Kowayid us saltanet Shahjehan’, p 67

5 Bernier, pp 247-48

Indeed, Manucci had noted seeing Shahjahan himself sitting in a similar style on his throne, with cushions supporting his back and arms; and remarked that “throughout the whole of Hindustan, they do not sit upon chairs, but upon carpets or mattresses, with their legs crossed.” 6

Though many visitors were most impressed by these opulent residences and therefore described them in detail, there were of course homes of all sorts in Shahjahanabad. As one writer of the eighteenth century put it: “The buildings were constructed by the poor and the rich and great men according to their limited or ample means, and they planned them to suit their inclinations and tastes”. 7 Bernier, with his eye for detail, paints a more detailed picture for us, telling us that intermingled with the houses of the rich, which were built of brick and fine white lime plaster, there were numerous small dwellings built of mud and thatched with straw. Some of these were within the compounds of the richer estates, and belonged to the many soldiers and other retainers who served these noble estates; but many were outside these, and belonged to artisans and other workers. These thatched roofs were in fact prone to catching fire, and Bernier reported that large conflagrations were common in the city, noting, “more than sixty thousand roofs were consumed this last year by three fires, during the prevalence of certain impetuous winds which blow generally in summer.” 8

The streets, bazaars and buildings of the new capital were what every observer first remarked on. What made the new capital a truly great city, however, were its people. Sujan Rai Bhandari, a historian writing in the late seventeenth century, said,

“Men of Turkey, Zanzibar, Syria, the English, the Dutch, men of Yemen, Arabia, Iraq, Khorasan, Khwarizm, Turkmenistan, Kabul, Cathay, Khotan, China, Mahachin (greater China), Kashgar, Tibet and Kashmir, and other provinces of Hindustan have chosen to reside in this metropolis. They have learnt the manners and speech of this place, which is the original language of Hindustan, and are employed in their respective work and professions. These different classes of people live together like sentences in a passage of prose, and their manners harmonise like the verses of a poem”. 9

The ethnic diversity of the population also went hand in hand with diverse beliefs and practices, for Sujan Rai added: “in each bazaar, street, lane and courtyard they have constructed mosques, temples, monasteries and seminaries, from which they derive material and spiritual benefits in this world and the next.” 10

Local laws made allowances for the diverse lifestyles of this mixed population. There was a significant population of Europeans living in the city in the seventeenth century, and Manucci tells us that they had the exclusive privilege of distilling liquor within the city, a privilege probably given to them in consideration of their cultural preferences. Manucci however

6 Manucci, Storia do Mogor (translated by William Irvine, John Murray, London, 1907 vol 1 p 88

7 Shah Nawaz Khan, Maathir ul umara, (translated by H Beveridge and Baini Parshad) Vol 2, Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1952, p 271

8 Bernier, p 246

reported that the rules could be circumvented, and he himself was involved in the corruption. He accepted a sum of money from a resident of the city who then distilled spirits nominally under Manucci’s name. 11

Not all the people from far flung lands mentioned by Sujan Rai may have been residents of the city. Many were no doubt visiting traders who came for commercial opportunities offered by the capital of one of the richest empires in the world. Its bazaars held the finest goods from all parts of the empire, and indeed from all parts of the world. Among these bazaars, none was richer than Chandni Chowk. This was the largest square in the city, located on the main east-west street of the city. At its centre lay an octagonal pool that reflected the moonlight, or chandni, which gave it its name. Surrounding it, also on an octagonal plan, were arcades with shops and coffee houses. This square and its buildings were the property of Shahjahan’ s eldest and favourite daughter, Jahanara, who was a wealthy woman with considerable property and mercantile interests. Her property in the new capital was extensive. The official who had supervised the Shahjahanabad project had laid out a large garden to the north of Chandni Chowk. When this was complete, Shahjahan gifted the garden to his daughter. Jahanara soon after built in it a large sarai – accommodation for visitors to the city, most notably rich merchants.

Merchants thronged to Shahjahanabad. It soon became evident that city planners had not quite allowed for the sheer volume of traffic, both goods and people, that would be coming into the city, particularly on the major trade route from the north-west. This road, later known as the Grand Trunk Road, entered the city at the western, or Lahore gate of the city. This portal in the city wall was clearly not wide enough for the traffic passing through it by the time Shahjahan’s successor Aurangzeb came to the throne. Such were the jams here that several times the emperor too, on his way out of the city for a hunt, had to turn back and take another route. He therefore ordered that the gate by widened, and ordered that compensation be paid to the owners of some houses that had to be demolished to make room.

Shahjahanabad had grown into a rich, thriving and populous city within a few years of its founding. Though it had been established by imperial fiat, it flourished on the initiative of its diverse and vibrant population. Cultural vitality became a defining feature of its identity. There were of course the ateliers and soirees in the imperial palace and the noble estates, but what was most visible to the visitor was the cultural life of the streets and squares.

The most renowned of the city’s squares was Chandni Chowk. Dargah Quli Khan, a young nobleman from South India, who lived in Delhi between 1739-41, asserted: “Such rare and precious goods are to be seen here each day that even if one had the treasure of Korah (a

9 Adapted from Shahbaz Amil, ‘Critical edition, translation and annotation of Khulasatut-twarikh of Sujan Rai Bhandari’, Indian Council for Cultural Relations, New Delhi 2003, p 11; and Sujan Rai Bhandari, Khulasatu-t-tawarikh, (M. Zafar Hasan ed.) Delhi, 1981, p 30

10 Ibid. p 13; p 31

11 Manucci, Storia do Mogor, pp 95-96

Biblical/Quranic figure), it would be insufficient (to buy them all)”. 12 He told of shops selling rarities from around the world, rich fabrics and clothing, precious gems and pearls, enticing perfumes, finely made swords and daggers, glass huqqas, Chinese crockery, bowls, jugs, and wine cups. In its coffee shops poets gathered, to recite their poetry and accept the praises of their listeners and peers. Indeed, said Dargah Quli, even the highest nobles could not resist coming here for a stroll.

Less refined but even more vibrant was Chowk Saadullah Khan, a large square that occupied the space outside the two city-facing gates of the Red Fort. Bernier compared it to Pont Neuf in Paris, crowded with hawkers and public entertainers. The most detailed and vivid descriptions however, have been left to us by Dargah Quli Khan. He spoke of the purveyors of various goods that gathered here – sellers of arms, cloth, food, birds and animals; but also of religious preachers, fortune tellers and quack doctors selling exotic remedies. Mimics, dancers and storytellers entertained the crowds of people of all classes that gathered here. One of the most noted, and indeed notorious, of the dancers Dargah Quli described thus:

“The beardless youth, the creator of tumult, Miyan Hinga; his complexion like porcelain, and his clothes like jasmine, are both white. He gathers a crowd every day in front of the fort of the capital.…many respectable people come to the chowk under the pretense of a taking a stroll or buying some rare things, and obtain gratification from the spectacle of Hinga’s beauty. Others gather around the performance seated on their horses and quite frankly and enthusiastically behold the sight of this creation of God….some of those who come here to

12 Dargah Quli Khan, Muraqqa e Dehli, translated into Urdu by Khaliq Anjum, Anjuman Taraqqi- e-Urdu Hind, New Delhi, 1993, p129 (translation mine)

13 Ibid, pp 174-75

buy essentials become so absorbed in the performance that they forget their errands, and go home empty handed, having spent their money on the performance.” 13

Musicians and dancers also filled the assemblies in the Mughal court of that time, when the aesthete Muhammad Shah was the emperor. He was a generous and discerning patron who gave employment to talents of all sorts, including dancers, musicians, singers, and mimics. His entourage had stars such as Nemat Khan, also known as ‘Sada Rang’, a famed musician and vina player. Apart from his performances in the palace, Nemat Khan held a monthly musical gathering at his own home which lasted through the night. Another renowned musician was the qawwal Taj Khan, who also held once-a-month gatherings at his home, where many Sufis and others participated. Other musical luminaries of the city included descendants of Tan Sen, one of the ‘nine jewels’ of the emperor Akbar’s court. 14

7 - Musicians of Delhi, 1820s

Many of the most popular singers in the city were women, most of whom performed at the gatherings held at private homes. The foremost disciple of Nemat Khan was Panna Bai, universally and highly acclaimed. Some of these singers, such as Chamani, who was patronised by the emperor, held regular musical gatherings at their homes. One famous dancer and courtesan of the time, Nur Bai, became a major patron in her own right, and exercised influence at the court and among the nobility. 15

14 Ibid, pp 160-64

15 Ibid, pp 176-78, 182-83

Mohammad Shah’s courtiers took their cue from him in patronising people of talent. The soirees held in their elite homes were characterised by the best performers, and by conversation marked by wit and repartee. Choice food, tobacco and wine flowed freely. Some of these gatherings were particularly riotous. Dargah Quli described one nobleman who organised a large gathering once a month to which a huge crowd came. Singers, mimics, dancers and courtesans provided entertainment, and hawkers set up stalls selling food and other wares. 16

Fig. 8 - A dance performance in a haveli in the late nineteenth century

Dargah Quli described a city in which people enjoyed and patronised the arts, and his portrayal of cultural and material life does not seem very different from the accounts of seventeenth century visitors. There is no doubt however that the high point of the empire during which Shahjahanabad had taken shape had come to an end by the mid eighteenth century. The decades that followed the death of Aurangzeb were marked by civil wars and foreign invasions. In fact Dargah Quli’s sojourn in Delhi saw one of the most devastating of these invasions – that of Nadir Shah, the ruler of Iran, in 1739. This was catastrophic for the city and its inhabitants. In addition to the massacre of around twenty thousand citizens, vast treasures were carried back as loot by Nadir Shah. Famous among these plundered treasures was the opulent jewelled Peacock Throne commissioned by Shahjahan, and the famous Kohinoor diamond.

This did throw a pall of gloom on the assemblies held in the palace and in the homes of the nobles. Speaking of one particular nobleman, Latif Khan, Dargah Quli noted that “since he has spread his wealth at the feet of the emperor, the large gatherings of earlier times have

ceased. Yes, some intimate friends still gather, and party till late at night.” 17 Thinking back to the heyday of Muhammad Shah’s reign, Dargah Quli lamented: “What days were those, when entertainment was free!” 18

Nadir Shah’s attack was only the first catastrophe that was to strike the Mughal empire and the capital city. The second half of the eighteenth century saw an intensification of civil wars, with different factions within the Mughal court engaged in contests to control the emperor, or to place their own puppet on the throne. The empire was also breaking up. Governors of several provinces, such as Deccan, Awadh, and Bengal, had for all practical purposes become rulers in their own right, neither taking orders from the emperor, nor making sure that taxes from the territories they controlled reached Delhi. There were also other regional forces that were rising up – the Marathas, Sikhs, Jats and Rohillas. These upheavals within the empire also invited further invasions from without – such as that of Ahmad Shah Abdali, the ruler of Afghanistan.

The city and its cultural life had just about survived the invasion of Nadir Shah, but these cumulative calamities devastated it. It was no longer the capital of a flourishing empire. Trade slowed, the nobility was impoverished, a bewildering succession of emperors came to the throne, many through palace coups, leading to a breakdown in administrative efficiency. People with talent began to leave the city. Among them were poets, who could no longer find patrons in Shahjahanabad. One such was Mirza Muhammad Rafi ‘Sauda’, born in a noble family in Delhi, who decided to join the general exodus from the city. He wrote an ode to the city that lamented its decline:

“How can I describe the desolation of Delhi? There is no house from where the jackal's cry cannot be heard. The mosques at evening are unlit and deserted, and only in one house in a hundred will you see a light burning. Its citizens do not possess even the essential cooking pots, and vermin crawl in the places where in former days men used to welcome the coming of spring with music and rejoicing. The lovely buildings which once made the famished man forget his hunger are in ruins now. In the once-beautiful gardens where the nightingale sang his love songs to the rose, the grass grows waist-high around the fallen pillars and ruined arches. In the villages round about, the young women no longer come to draw water at the wells and stand talking in the leafy shade of the trees. The villages are deserted, the trees themselves are gone, and the wells are full of corpses. Jahanabad (Shahjahanabad), you never deserved this terrible fate, you who were once vibrant with life and love and hope, like the heart of a young lover, you for whom men afloat upon the ocean of the world once set their course as to the promised shore, you from whose dust men came to gather pearls. Not even a lamp of clay now burns where once the chandelier blazed with light. Those who once lived in great mansions now eke out their lives among the ruins….. But Sauda, still your voice, for your strength fails you now. Every heart is aflame with grief, every eye brimming with

16 Ibid, pp 138-39, 142-43

17 Ibid, pp 138-39

18 Ibid, p 164

tears. There is nothing to be said but this: We are living in a special kind of age. So say no more.” 19

Sauda’s contemporary, the poet Mir Taqi ‘Mir’ was also forced to leave Delhi and migrate to Lucknow, where he continued to feel like a stranger, missing his hometown:

“Why do you ask where I come from O Easterners?

Mocking me when you know I am vulnerable Delhi was a city, famed throughout the world, Where lived the chosen ones of the age: Fate looted it and laid it waste, To that ravaged city I belong!” 20

The city lay desolate. Its emperor in the closing years of the eighteenth century was Shah Alam, who lived in exile for many years. When he returned, it was as the puppet of the Marathas. This too was not protection enough, for the city continued to be subject to outside attacks. During one such incursion of the Rohillas, not only were the city and palace looted, but the emperor was blinded.

Few merchants from far off lands came to trade in Delhi, no immigrants came seeking opportunities and patronage. The only opportunities the city still offered were to soldiers, many of whom were migrating into North India at this time, to take advantage of the military market that had arisen as a result of many wars that wracked the country. Some of these freelancing mercenaries were from Central Asia, others from Europe. One of these, AntoineLouis Henri de Polier spent some time in Delhi in the 1770s, in the employment of the Mughal state. He saw a city in ruins. Many of the grand mansions of nobles were dilapidated, their wood taken away for fuel by the Marathas and Rohillas who had intermittently attacked and occupied the city. Polier made his living quarters in the mansion of Qamaruddin Khan who had been the Prime Minister during the reign of Mohammad Shah. He found that he had to share this erstwhile grand dwelling with “a good quantity of bats, owls, swallows and pigeons”. Even the river Yamuna, on the banks of which Shahjahan had built his capital, had deserted it. Polier wrote in a letter that it had recently changed its course, from lapping the walls of the fort, to retreating about a mile away. 21 In later years a garden would be laid out at the foot of the fort here, with tamarind and banyan trees. 22

By the end of the century there was a noticeable increase in the number of Britons who were making their way to Delhi. The British East India Company, which had at one time been only one of the several European trading powers in India, had by the mid 1760s become a territorial power in India, with a strong base in the rich province of Bengal and Bihar. By the

19 Translation in Ralph Russell and Khurshidul Islam, Three Mughal Poets: Mir, Sauda, Mir Hasan, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1968, pp 67-68

20 My translation from Urdu

21 ‘ Extracts of letters from Major Polier at Delhi’, Asiatic Annual Register 1800, Miscellaneous tracts pp 36, 29-30, 38.

1780s some of their civil and military officers were travelling northwards. It was in the company of one such officer that the artists Thomas and William Daniel managed to visit Delhi, while their predecessor, William Hodges had been prevented from doing so just a decade before, because the region around Delhi had been a scene of war. 23

In 1793-94, the British sent a team of military men on an expedition to survey the region of the Doab up to Delhi. A member of that team, Captain W Francklin, wrote a detailed report on Delhi as he found it: “Within the city of new Delhi are the remains of many splendid palaces, belonging to the great Umrahs (nobles) of the empire”, he wrote. Their ruinous and largely unoccupied condition allowed him to inspect the innermost chambers of some of them in great detail. He wrote of the buildings that were a part of the estate of the Governors of Awadh – Sa’adut Khan and his successor Safdar Jung, who had also been powerful courtiers at Delhi:

“Each palace is likewise provided with a handsome set of baths, and a Teh Khana under ground. The baths of Sadut Khan are a set of beautiful rooms, paved, and lined with white marble; they consist of five distinct apartments, into which light is admitted by glazed windows at the top of the domes. Sefdur Jung’s Teh Khana consists of a set of apartments built in a light and delicate style; one long room, in which is a marble reservoir the whole length, and a smaller one raised and balustraded on each side; both faced throughout with white marble.” 24

The Company was also interested in information about the commerce and wealth of the city, which Francklin provided:

“The Bazars in Delhi are at present but indifferently furnished, and the population of late years miserably reduced. The Chandney Choke is the best furnished in the city, though its commerce is but trifling. Cotton cloths are still manufactured, and they export indigo. Their imports are by the northern caravans, which generally come once a year; they bring with them from Cabul and Cashmere shawls, fruits, and horses; the two former articles are procurable in Delhi at a reasonable rate. There is also a manufactory at Delhi for hooka bottoms. Precious stones are also to be had in the Bazars, and the black and red cornelians of the largest and most beautiful size. The adjoining country is well cultivated, and the neighbourhood of the city produces corn, rice, millet and indigo.”

22 Leopold Von Orlich, Travels in India (trans H.E. Lloyd), Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, London, 1845

23 Katherine Prior ed, An illustrated journey round the world by Thomas, William and Samuel Daniell, The Folio Society, London, 2007, pp 61, 68-72

24 W. Francklin, The history of the reign of Shah-Aulum, the present Emperor of Hindostaun, London, 1798, Appendix I, ‘Account of Modern Delhi’, pp 202, 207-08

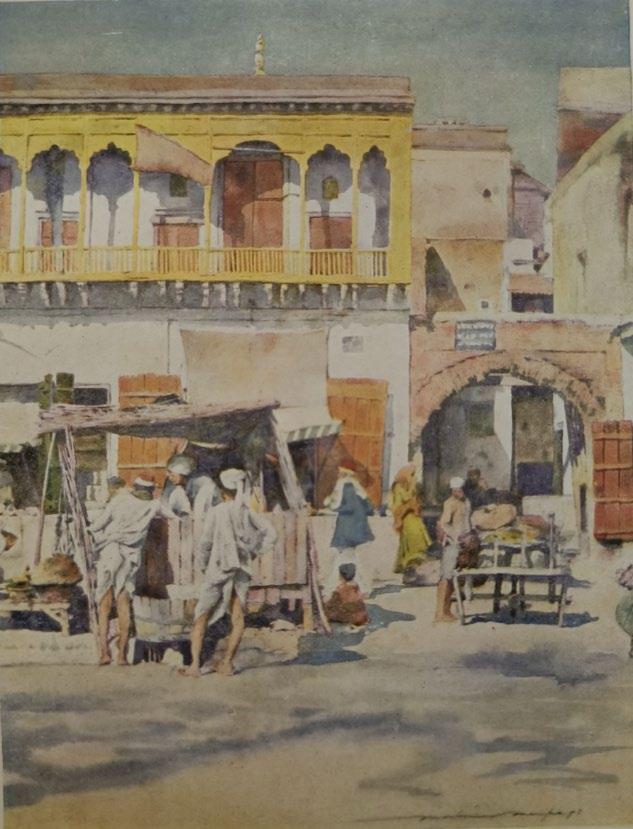

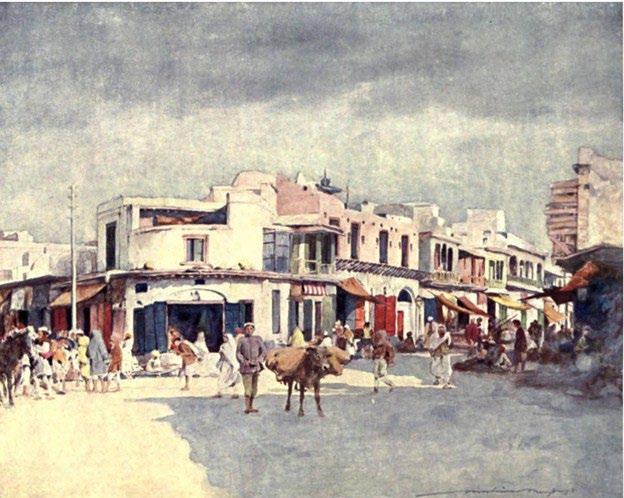

9 - A typical scene in a bazaar, from an early twentieth century painting

Around the same time as Francklin, a young man of a prominent mercantile family visited Delhi. This was Thomas Twining, second son of the founder of the tea business in Britain, that went by the family name. He did not however come to Delhi for commercial opportunities but under the auspices of the British East India Company. His personal wealth

and connections in high places enabled him to arrange the body of armed men that he needed to traverse the country that had been devastated by wars and was still beset by banditry. Arriving in Delhi he saw the same signs of neglect the others had, including that the canal that used to flow down the centre of the main streets and gardens was now dry. The lack of effective administration had caused a silting up of the canal upstream.

Twining also wrote evocatively of the people he saw in the city:

“I afterwards passed through a bazaar, in which were numbers of people, the greater part well wrapped up in white dresses descending a little below the knee, and confined round the waist by a roll of cotton cloth. Many had these dresses quilted for the winter, which now began to be felt in the keenness of the air in the morning and evening. Though white was the prevalent colour for the robes and turbans of the people, some wore printed calicoes of various patterns and colours. The sirdars and men of rank, and many even of the sircars, mahajans, and shraffs (merchants, shopkeepers, and money-changers) wore shawls of different colours and forms, but mostly long, which, descending from the shoulder, or from the head in cooler weather, crossed round the middle of the body, and met in a loose knot behind. It was in this way that I generally wore my own shawl.” 25

He noted a very particular sign of the disturbed times: “A great many of the people carried arms of some sort, generally a scimitar, or convex blade, enclosed in a black scabbard, and a round black shield, with four or five small bosses in the centre. The same lofty military air, observable in the population of Behar, Oude, the Doab, and Agra, was no less striking here.”

26

25 Thomas Twining, Travels in India a hundred years ago, James R Osgood, McIlvaine & Co, London, 1893, pp 241-242

26

Change however was imminent. Armies clashed at the gates of the city once again in 1803, but this time war would be followed by more than half a century of peace. The British East India Company had defeated the Marathas to capture Delhi and its surroundings. Indeed as the British emerged victorious in the contest over the erstwhile Mughal empire, wars largely ceased over most parts. In Delhi, though the Mughal emperor continued to live with his extended family in the Red Fort, the British were the true rulers of the city and the territory around. This change of regime made it conducive for a large number of British travellers, both official and otherwise, to visit the city.

High officials came on official tours of work, but also to see the city that had been spoken about as one of the most famed. Among the earliest was the Commander-in Chief of the British army, George Nugent, who visited in 1812, and whose wife Maria recorded the visit in some detail in her diary. Among other things, she wrote of crossing the Yamuna river opposite Shahjahanabad:

“The ford took us some way down the stream, and, as I looked back, the sight was really extremely pretty; all the elephants, the cavalry, an immense number of loaded camels, and boats filled with the infantry escort, were all on the river at the same time. The city opposite, with the sun shining on its gilt domes – the red fort and palace – the different guard all turned out – the whole staff of the district on the banks, with an innumerable number of natives, in their party coloured dresses – had a most striking appearance.” 27

Though few came with such impressive entourages, this crossing the Yamuna by boats was an experience shared by many visitors to the city. Early in the nineteenth century a pontoon bridge was added, but this was a season affair, since it could not withstand the swell of the monsoon and was washed away or taken down only to be rebuilt each winter.

27 Maria Nugent, A Journal from the year 1811 till the year 1815, London, 1839, vol I, pp 407-08

As one observer wrote:

“I had been present at Dehli this season, in the month of July, when the monsoon set in, and had witnessed the sudden rise which took place in the waters of the river: the rains opened at nine o’clock in the morning, and before noon, the Jumna, which had hitherto been almost fordable, had overflowed its banks, and was in many places four and five miles in breadth. Away go all the boats, bridges, huts, houses and gardens, in some cases leaving the inmates scarcely time to save their persons: it is not however frequently thus, the greater part of the habitations within reach of the flood being constructed of planks and mats, which may be removed at a moment’s notice. The havoc in the melon-gardens is always a picture worth beholding; every elephant in this city, so overstocked with them, turns out to take advantage of the general spoliation, and all along the banks are seen these monstrous brutes, wading or swimming about, in search of the fruit, which they at once appropriate.” 28

This crossing of the river by boat to arrive in Delhi was an experience many travellers wrote of right down to the 1860s, when the railway and the accompanying railway bridge was built.

28 Thomas Bacon, Studies from nature in Hindostan, W.H.Allen and Co., London, 1837

From the 1820s the accounts of visitors and residents reveal quite clearly that the city had recovered from the calamities of the eighteenth century. The main bazaar streets were filled with shops selling a variety of goods. Some of these were local manufactures, such as printed and embroidered textiles, gold and silver jewellery, enamelled and set with precious stones.

29 Leopold Von Orlich, Travels in India (trans H.E. Lloyd), Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, London, 1845

30 Captain Mundy, Pen and pencil sketches, John Murray, London, 1833, vol 1, p 363

Another novelty that was popular with European tourist was small paintings on ivory, featuring portraits as well as famous buildings. 29 They were also public spaces for flaneurs, and most prominent among the latter were men, “dressed in the most extravagant colours, with yellow slippers, their muslin skull caps stuck jauntily over one ear, and their long hair frizzed out over the other, like a black mop. If you watched their motions, you might detect knowing looks passing between them and the hundreds of ladies of no very equivocal profession, who sit in the verandahs or behind the trellised chicks of the windows smoking their little houkahs, and displaying to the passengers their thinly clad persons, well antimonied eyes, and henna-tipped fingers.” 30

The area immediately around Jama Masjid had also emerged as a lively public space space. One resident of the city, Syed Ahmad Khan, who would later became famous as an educationist and social reformer, described in great detail the bustle on and around the steps of the mosque every evening. He spoke of food vendors grilling kebabs and selling cooling drinks, other hawkers selling clothes and fabrics, or varieties of birds and animals – from pigeons to horses. This was also the place for the kind of entertainers that had in earlier times plied their trade in the square in front of the fort:

“The biggest spectacle here is of the conjurors and story-tellers. In the evening a story-teller sits here on a stool and recites the tale of Amir Hamza. Elsewhere the story of Hatim Tai, and in another that of Bustan e Khayal is being recounted, and hundreds of people gather to hear these. On another side a conjuror performs magic, turning an old person into a youth, and a youth into an old person.” 31

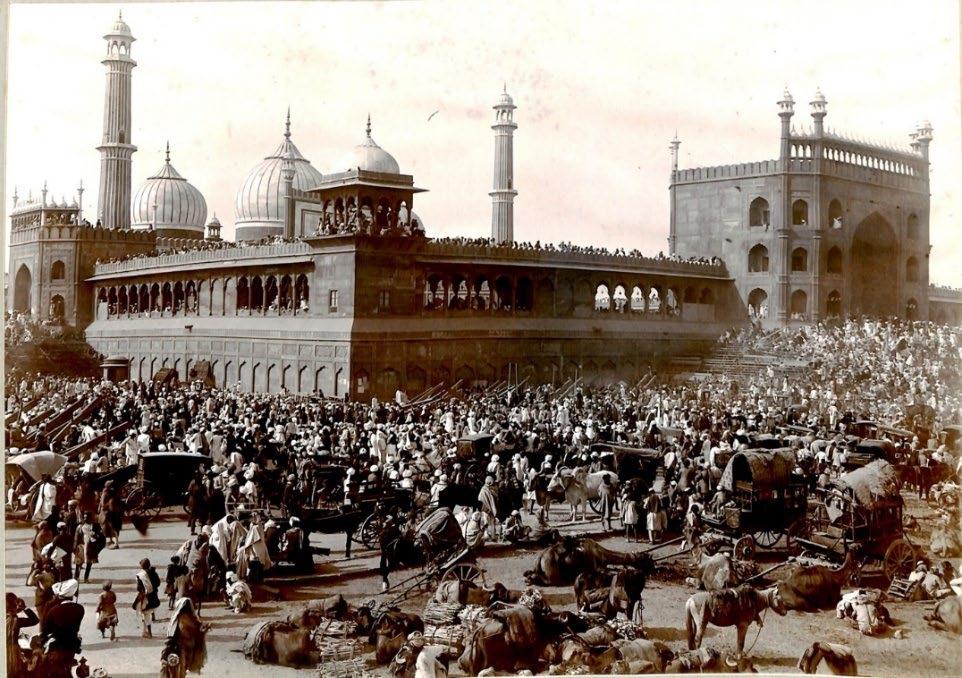

Fig. 14 - A lively scene in front of the Jama Masjid, from a major event in the early twentieth century – the Coronation Durbar of Edward VII

31 Syed Ahmad Khan, Asarussanadid, Urdu Academy, Delhi, 2000, pp 277-83 (78), translation mine

English visitors compared some of these performances to Punch and Judy shows, and also mentioned the popularity of snake charmers and jugglers, and the popularity of kite flying as a sport.

17 –

Some travellers noted an interesting characteristic of Delhi of this period – the openness to European ways and fashions. Emma Roberts, an Englishwoman from Calcutta, noted that nowhere in North India outside of Bengal had she seen so much of a desire to embrace European architecture, clothing, furniture, etc. She noted that many houses had Grecian piazzas, pediments and porticos on their facades. On the main street one could seen several English carriages, with alterations made to suit the climate and Indian tastes. The occasional

33 Emma Roberts, Hindostan illustrated, Fisher, Son and Co, London, vol II; Emma Robert, Scenes and characteristics of Hindostan

man, notably Prince Babur, the second son of the emperor Akbar II, had also taken to wearing European clothes. She noted that not only were the shops filled with European products, they also had sign boards with the names and specializations of their proprietors in Roman letters. Moreover, European visitors would often be greeted on the street by respectable-looking city folk in English – with a ‘good morning’ or ‘how do you do?’

33 The cosmopolitan spirit of the era of Shahjahan and Aurangzeb had clearly survived the devastation of the eighteenth century.

Fig. 20 - The Chandni Chowk street in 1860s. Some European style architecture can be seen, but also by this time the central water channel had been covered over

Like many others who described the city, Emma Roberts remarked on the bustle of the bazaar, the crowds on foots, or in different sorts of vehicles, the colourful attire, but also very vividly the smells and sounds; writing of the fumes of cooking with garlic and other pungent ingredients that almost overpowered the senses, and of

“The cries of the venders of different articles of food, the discordant songs of itinerant musicians, screamed out to the accompaniment of the tom-tom, with an occasional bass volunteered by a cheetah grumbling out in a sharp roar his annoyance at being hawked about the streets for sale, with the shrill distressful cry of the camel, the trumpetings of the elephants, the neighing of horses, and the grumbling of cartwheels, are sounds which assail the ear from sun rise until sunset in the streets of Delhi.” 34

Emma also brought to her descriptions some insights that might have been a product of her gender. For instance she commented on one common feature of the houses on the streets and correctly linked it to very specific domestic practices:

“The houses are, for the most part, white-washed, and the gaiety of their appearance is heightened by the carpets and shawls, strips of cloth of every hue, scarfs and coloured veils, which are hung out over the verandah or on the tops of houses to air, the sun in India being considered a great purifier, a dissipator of bad smells, and even a destroyer of vermin”. 35

Women did bring some unique perspectives to their accounts and observations, and in the first half of the nineteenth there were several English women who came to Delhi and left behind their memoirs. The most interesting of these women was Fanny Parks, the artist wife of a mid-ranking Company official. Fanny was an inquisitive and intrepid traveller, open to new experiences. In Delhi she visited the usual historical sites, spent time visiting the women of the Mughal royal family in the palace. She also ventured into the poorer parts of town, away from the glittering lights of Chandni Chowk. One such visit was to the mosque popularly known as Kali Masjid, a fourteenth century mosque close to the southern periphery of Shahjahanabad:

“In the evening, we drove to the Turkoman gate of the city, to see the Kala Masjid or Black Mosque. We found our way with difficulty into the very worst part of Delhi : my companion had never been there before, and its character was unknown to us ; he did not much like my going over the mosque, amid the wretches that surrounded us ; but my curiosity carried the day….. I wished to sketch the place, but my relative hurried me away” 36

Others, less intrepid, were content with exploring the more obvious monumental sites, such as the Jama Masjid. This congregational mosque of the city was manged under the supervision of the emperor himself, but tourists could visit it. Many also climbed the minarets, which provided a panoramic view over the city. One visitor, Helen Douglas Mackenzie, the wife of an army officer, went up on the roof, which gave her a view of life on the rooftop terraces of the houses around. She commented on one sight in particular:

21 -

34 Emma Robert, Scenes and characteristics of Hindostan , W.H. Allen, London, 1835, vol III, pp 173-74

35 Ibid, vol III, p 172

36 Fanny Parks, Wanderings of a pilgrim in search of the picturesque, Pelham Richardson, London, 1850, vol II, pp 221-22

Fig. 22 - Kalan Masjid, some decades after Fanny Parkes visited it

“Close beneath us (we) saw a sport for which Delhi is famous. On the roof of several houses were men waving little flags to make their flock of pigeon fly, while elder men sat gravely by, smoking. A large hurdle was fixed on the roof for the pigeons to alight upon. When they meet another flock in the air the two parties mingle, and one invariably carries away some from the other. Each flock then returns home, and the owner who has gained some of his neighbour’s birds, goes to him and threatens to sell them if they are not ransomed. It was very pretty to watch two, three, and sometimes four flock of these beautiful birds, of all colours, meeting, mingling, and then parting again.” 37

Helen also participated in another spectator sport of Delhi – watching a wedding procession:

“About five o’clock we drove to a house in the Chandi (sic) Chouk, belonging to one of the native sub-collectors, a Mussalman, who had prepared seats for us, whence we could see everything. The Chandi Chouk is a double street, divided down the middle by a stone watercourse, the edges of which were crowded with people. The procession was passing down the side furthest from us, and turning at the top of this immense street, it paraded before the bride’s house, which was a little way above us, and then came close under our windows. It was more than a mile long! The balconies and flat roofs of the houses, which are generally low, were covered with people; here was a variegated group of men and children, there a bevy of shrouded Muhammadan women, the first I have seen, and the appearance of the crowd was that of a bed of tulips.” 38

Fig.

23

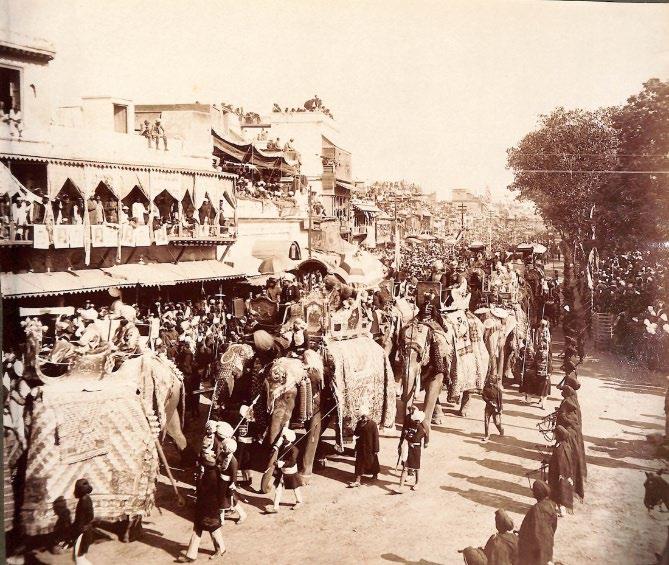

- Procession from Edward VII’s Coronation Durbar in 1902

Helen Mackenzie, like all Europeans referred to the whole street from the fort to Fatehpuri masjid as ‘Chandni Chowk’. This was a new phenomenon of the nineteenth century, and was probably the result of a misunderstanding – the newcomers not understanding that ‘chowk’ was the name only applied to the square. In any event it was probably encouraged by shopkeepers on the street who were happy to embrace this, as it gave them a piece of the reflected glory of the original Chandni Chowk, the royal square still owned by the emperor. The practice therefore, stuck.

The first half of the nineteenth century was a period of prosperity as well as cultural efflorescence in the city, the heyday of poets such as ‘Ghalib’, ‘Momin’, ‘Zauq’, and ‘Zafar’ –the emperor Bahadur Shah. This era was unexpectedly brought to an abrupt close by another calamity that hit the city. In May 1857 a revolt against British rule broke out, and soon spread through large parts of North and Central India. It was centered in Delhi, and at its head was Bahadur Shah. After four months or so however the British forces managed to retake the city, and in the aftermath, exacted a heavy revenge on the people. Captain Charles Griffiths, part of the conquering army, described the scene:

“The portions of the town we passed through on that day had been pillaged to the fullest extent. Not content with ransacking the interior of each house, the soldiers had broken up

37 Mrs. Colin Macenzie, Life in the mission, the camp, and the zenana, Richard Bentley, London, 1853, vol 1, pp 162-63

38 Ibid, pp 179

every article of furniture, and with wanton destruction had thrown everything portable out of the windows. Each street was filled with a mass of debris consisting of household effects of every kind, all lying in inextricable confusion one on top of the other, forming barricades from end to end of a street -many feet high. We entered several of the large houses belonging to the wealthier class of natives, and found every one in the same condition, turned inside out, their ornaments torn to pieces, costly ' articles, too heavy to remove, battered into fragments, and a general air of desolation pervading each building.. …..Dead bodies of sepoys and city inhabitants lay scattered in every direction, poisoning the air for many days, and raising a stench which was unbearable. These in time were almost all cleared away by the native scavengers, but in some distant streets corpses lay rotting in the sun for weeks” 39

The Revolt and its aftermath finally extinguished the remnants of the Mughal empire, with the exile of the last emperor, Bahadur Shah, to Burma. All royal properties were confiscated, and many were demolished – among these was the original square called Chandni Chowk, and Jahanara’s sarai. An area four hundred and fifty yards wide around the perimeter of the fort was cleared of buildings, to provide security to the army that was now quartered in the fort. The poet Ghalib wrote to a friend:

“The city here is being demolished. Extensive, famous markets–Khas bazaar, Urdu bazaar, Khanam ka bazaar, such that each was a small town in itself; now no one can tell where it was located. The owners of shops and houses cannot point out the spots where their properties stood.” 40

24 - The area in front of the Jama Masjid, cleared of buildings

39 Charles John Griffiths, A narrative of siege of Delhi, 1857, John Murray, London, 1910, pp 198, 201

40 Khaliq Anjum ed., Ghalib ke Khutut, New Delhi 1985, vol 2, p 607 (translation mine)

Equally devastating for the life of the city were the cultural losses. The extinguishing of the Mughal court, the death or exile of many of its citizens, particularly people of talent and culture, were blows to the character of the city. Ghalib wrote to a friend bemoaning the changes,

“What are you asking? What can I write? The being of Delhi was essentially centered on a few excitements–the Fort, Chandni Chowk, the daily bazaar in front of the Jama Masjid, the weekly gathering at the Yamuna bridge [there used to be a mini-fair at the bridge that had been built by the British across the river], and the yearly festival of the flower sellers [a festival sponsored by the royal family]. None of these five are there, so say, where is Delhi? Yes, there was once a city by this name in the territory of India.” 41

Shahjahanabad recovered from this catastrophe too. People, spaces and institutions, some old and some new, brought the city slowly alive again, though it was now stamped more thoroughly with a British colonial character. Jahanara’s Chandni Chowk and the adjoining sarai had been demolished. New structures came up in their place and the large garden behind was re-landscaped and renamed. The railway came to Delhi in the 1860s and added to the changed landscape. A popular tourist handbook described the new character thus:

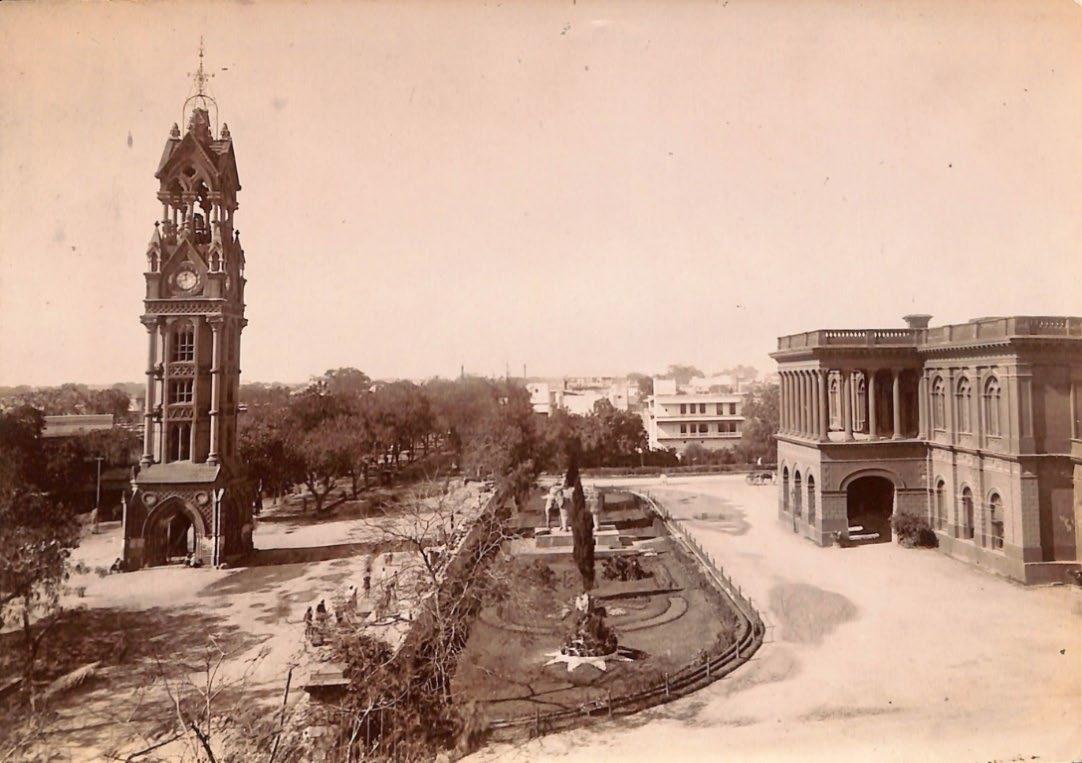

“The visitor will pass repeatedly through the Queen’s Gardens, which lie between the railway and the Chandni Chauk. These are well laid out with beautiful trees and shrubs, and abundant water from a branch of Ali Mardan’s Canal. There is a small collection of wild beasts. The fine building facing the Chauk is the Institute, which contains the station library, a reading-room, the municipal-offices, a museum, public-hall, and a pleasant suite of rooms, used for dances and other social reunions of the English residents. Visitors find admission to all its privileges easy enough, through their bankers or any resident European…… There is a fine clock tower opposite, in the Chandni Chauk, 128 feet high.” 42

Tourists came in ever larger numbers to Delhi, to see the remnants left behind by the Mughal and other dynasties that had ruled from not just Shahjahanabad but the many other capitals that constituted ‘Delhi’. A significant number, particularly the British, also came to visit the sites that were associated with the revolt of 1857. One such visitor, who was in Delhi on the fiftieth anniversary of the Revolt wrote:

“In Delhi an Englishman is treated with more respect than in places further south. Policemen salute when he passes and natives salam and move off the foot-path.

The horrors of the Mutiny are not forgotten in Delhi; and the common people there are very much afraid of an Englishman.” 43

The average tourist was too busy to notice this. Busy not only seeing the monumental historic sights, but buying the many arts and crafts the city was still famous for in the early twentieth century. Visitors often made special appointments to visit the shops of merchants

41 Ibid, pp 514-15

42 W.S. Caine, Picturesque India, George Rutledge and Sons, London, 1890, p 128

43 John Law, Glimpses of hidden India, Thacker, Spink and Co, Calcutta,

that had been recommended to them by their guide books or hotels. Many vendors even came to the hotels, of which there were now several.

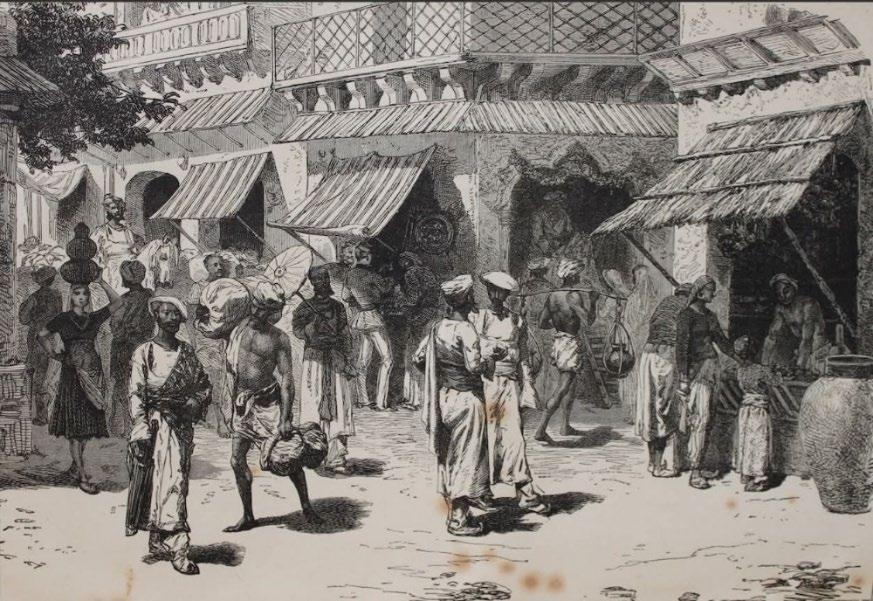

Chandni Chowk was no longer described by the visitor as the typical ‘Eastern bazaar’. The dandies lounging and flirting with courtesans, the bright and varied wares in shops, the variety of vehicles on the streets, are not the subject of the later travelogues. Shahjahanabad had changed of course, but also perhaps the gaze had changed. Frederick Treves, a renowned surgeon, looked at the commonplace in the bazaar, leaving behind an evocative description particularly of those whose daily lives were spent for most part on the street itself:

44 Frederick Treves, The other side of the lantern, Cassell and company, London, 1918, pp 53-54

“The dweller in the bazaar lives in the street, coram populo [in public] and his inner life is generously laid open to the public gaze. In the morning he may think well to wash himself in front of his shop, and to clean his teeth with a stick, while he crouches among his goods and spits into the lane. He sits on the ground in the open to have his head shaved, and watches the flight of the barber’s razor by means of a hand glass. The barber squats in front of him, and from time to time whets his blade upon his naked leg. The shopkeeper will change his clothes before the eyes of the world when he is so moved. He also eats in the open, and after the meal he washes his mouth with ostentatious publicity and empties his bowl into the road.

Every phase of the fine art of cooking with a suppression of no detail can be witnessed by the lounger in the bazaar. At the same time he can note how the Indian woman washes

26 -

her head, by wetting it and rubbing thereon the dust from under her feet. Indeed, in the bazaar, life is seen in its nakedness. There is little that is hidden from the gaze of the curious. There is no suggestion of keeping up appearances, nor is any effort made to practise crude social deceptions. The mysteries of the household are as bluntly laid open as are the apartments of a doll’s house when the front of the establishment is thrown wide by a delighted child. There are deeper shadows in courtyards and mean entries and behind hanging mats which the eye cannot penetrate, but if among the gloom there is the holy of holies of the Indian home, it may well be left in mystery.” 44

Fig. 27 - A street scene of the early twentieth century

The Shahjahanabad that Treves described was on the brink of fundamental changes. In 1912 Delhi became the capital of India, the British having decided to move their seat in India away from Calcutta. This brought new development to Delhi, but Shahjahanabad was marginalised in the process. A new capital, New Delhi, began to be built south of Shahjahanabad, and took nearly two decades to complete. In the meanwhile, the government functioned from a temporary capital that came up north of Shahjahanabad. While all the administration’s attention was on the new areas, Shahjahanabad’s civic infrastructure began to be neglected. The increasing deterioration of amenities and upkeep prompted many of the better off inhabitants to move out of the city to these new areas.

More changes came with the independence of the country from colonial rule in 1947. This was accompanied by the country’s partition into two countries, and a resulting upheaval in the form of translocation of large populations. Delhi was significantly affected by this as

many Muslims left and many more Hindus and Sikhs came in. In the few years following the Partition, Delhi’s population nearly doubled. The reason for this was simple – those migrating into the country were drawn to this large metropolis, which offered so many more opportunities than smaller towns.

This sudden influx of population needed to be housed, and the government undertook to provide housing in the form of many residential ‘colonies’ that were developed, mostly to the west and south of the existing twin cities of New Delhi and ‘Old Delhi’ – as people had now begun to refer to Shahjahanabad. The new migrants however did not just need housing, they needed livelihoods. In particular there were those who wanted commercial property in the form of shops, but wanted these in the heart of the city and not in the still new outlying developments. One of the solutions found was in the many havelis that were now vacant in Shahjahanabad, since the departure of their inhabitants to Pakistan. These were converted into commercial spaces – katras.

Almost overnight the character of Shahjahanabad changed from a substantially residential space with some important bazaars, into a much more commercial district. With the passage of years this trend has only intensified, until today it often seems that all of this historic neighbourhood is one big bazaar. It is therefore understandable why in popular parlance all of Shahjahanabad has now been subsumed in the name of its most famous square –‘Chandni Chowk’. Modern developments such as the metro have facilitated this too. The Metro not only brings shoppers from distant parts of the city, but also enables those who work in shops and other establishments to live outside the neighbourhood, and only come in the morning to open their businesses.

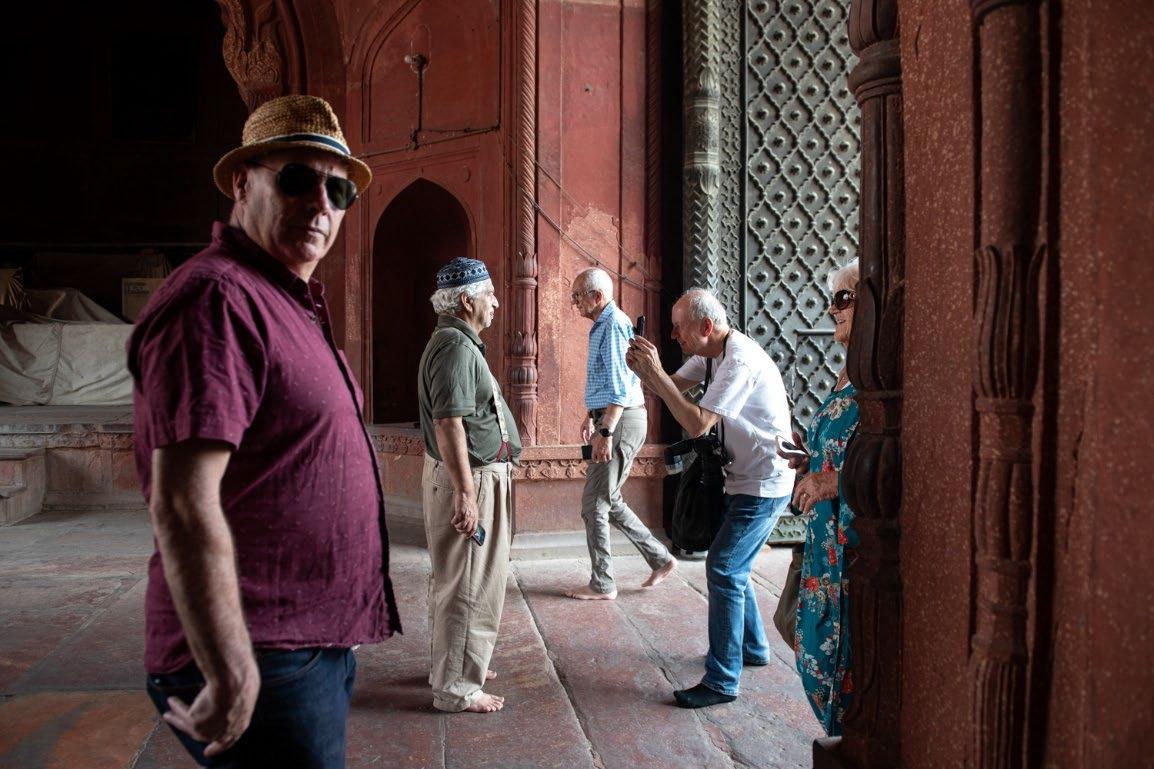

Visitors to Chandni Chowk today see a bit of what every visitor has seen in the city down the centuries. The bustle of crowds, the variety of different kinds of transport, the busy eating places, and the glitter of the shops, is all still there. People still come to see all of this, though today they record their impressions most commonly in ‘reels’. There is much that is picturesque in Chandni Chowk. Hence the reels. The look and feel seems colourful and exciting, and different, even from other parts of Delhi. Those who read history look with nostalgia at what was once one of the most famous cities of the world. They may see the recently landscaped main street and see in its middle a symbolic re-creation of the channel of water that once flowed there. They may see and admire the finely carved doorways that still survive on many house fronts in many streets. They may have visited the interiors of many of its historic buildings – the Red Fort and Jama Masjid certainly, but also the several other places of worship.

I would like to share with them what I see in Shahjahanabad. I see the narrow streets for what they tell me of a city planned many years ago, that still works well. Twining, writing two and a quarter centuries ago, had spoken of houses being “built in lanes near to each other, for the sake of shade” 45, and I am still thankful when I walk in these narrow shady alleys. These narrow streets were not built for motorised transport but for a city that could be traversed from one end to the other on foot. They were built for a slower pace of life, literally

45 Twining, Travels in India, p 252

and metaphorically. The doorways of the old houses are flanked by stone seats, where one may sit and exchange a few words with a neighbour or a passer-by.

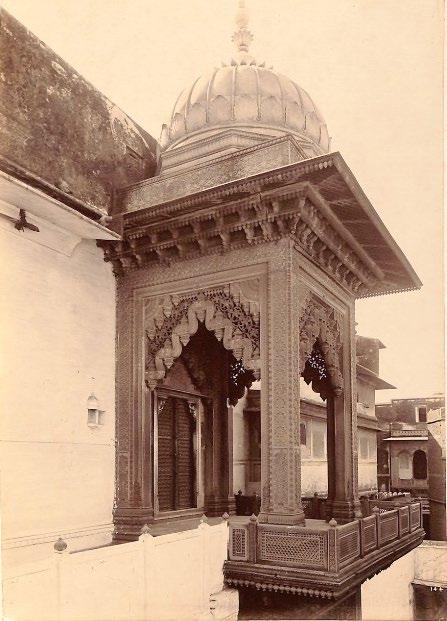

28 - The Naya Jain mandir, built in 1807

The houses are built close to each other but they are not claustrophobic. Their inner courtyards provide private open areas for a piece of the sky, air and light. The rooftop terraces are semi-public places where one might talk to or even go visit ones neighbours without having to step into the street. They are also places for the ever rarer pigeon keepers, and for kite flying contests. Balconies provide a window into the world without, and one’s own private viewing platform for goings-on in the street.

The broad main streets, once built for royal processions, are still used for this purpose, though the processions are now mainly religious ones. The ‘Chandni Chowk Road’ is testament to the multi-cultural history of the city – with its Jain and Hindu temples, mosques, church and gurudwara. Commerce is an important part of Shahjahanabad’s streets, and many of the specialist markets have a history nearly four hundred years old too – the spice market of Khari Baoli, the jewellers’ street known as Dariba Kalan, and the tinsel and spangles market of Kinari Bazaar.

These are integral parts of the city that need to be preserved. Not simply because they are old, or beautiful; but because they hold in them the spirit of a particular way of life. Shahjahanabad has always been a place where people have lived in close proximity with their neighbours – whether poor or rich, largely irrespective of their religious or ethnic identities. It is the form of these narrow streets, courtyard house with their rooftop terraces and open porches, that support this neighbourliness. The o pen bazaar streets which provide room for those who have nowhere else to live, represent an inclusive ideal, that does not prioritise a sanitised neatness over humanity.

The physical structures as well as the ways of life they foster are today being lost at an alarming rate. It seems that every day an old haveli is demolished, to be replaced by a solid block of a commercial building or a block of flats. I wonder if a time will come when each of those courtyards will be erased, and all of Shahjahanabad will be uninterrupted concrete construction, separated only by the narrow lanes? And then, how long will it be before someone says that those narrow lanes have become unsustainable and therefore a more thorough redevelopment is required?

The spirit of the old bazaars is being violated, not only by modern showrooms but by the recent addition of a mall, ironically called ‘Chandni Chowk’. Some of the bigger businesses of the district are moving in, but most of the small shops and eateries will never be able to afford the rents of such a place, while they will face competition from it. People will still come to eat and shop I suppose, in a mall that calls itself Chandni Chowk, but will they be content with a pretence and a travesty of what Chandni Chowk was?

How long can Chandni Chowk/Shahjahanabad retain its very distinct character, and should we even try to preserve it? I think we can, and we should. The argument for preserving the old street plan and historic structures goes beyond a nostalgia for the past. It is time we realise that a sensitive conservation and upgradation of the historic fabric of Shahjahanabad can not only enhance the quality of life of those who live and work there, but can be a powerful tool for the generation of livelihoods. Many great historic towns and cities around the world have used their heritage as an asset to attract tourists, who do not come simply to see ‘monuments’, but to spend time in historic districts, and to imbibe their very distinct flavours.

Chandni Chowk can be such a place – a neighbourhood where more people would like to live, and to visit and spend time in. It needs a vision that takes into account the very particular features of this historic city. For instance, Shahjahanabad needs special building regulations that not only preserve old buildings, but ensure that new constructions do not violate the essential character of the haveli model – for instance the existence of courtyards. It needs a fiscal regulatory framework that enables owners to get easy loans to restore old buildings, rather than incentivising redevelopment. It certainly needs upgrades to its civic infrastructure that go beyond the superficial aims of ‘beautification’. These measures can create a place that enhances the lives of residents and attracts visitors.

Three Lenses, Many Histories: Photographing the Old City (Abstract)

Colorful, chaotic, congested Chandni Chowk has been a favorite subject of photographers shooting in Old Delhi. The diversity of photographic approaches to this vibrant place is truly enlightening. Senior modernist Raghu Rai frames Chandni Chowk as a place of devotion, emotion, and survival. On the other hand, Raghubir Singh, one of the pioneers of color in photography, focuses on crowded bazaars. Mother Mahata has taken an architectural approach in black and white to the chronicle of Chandni Chowk. Contemporary artist Atul Bhalla has taken an entirely different approach. His conceptual works approach the city with a question of water availability and ecology.

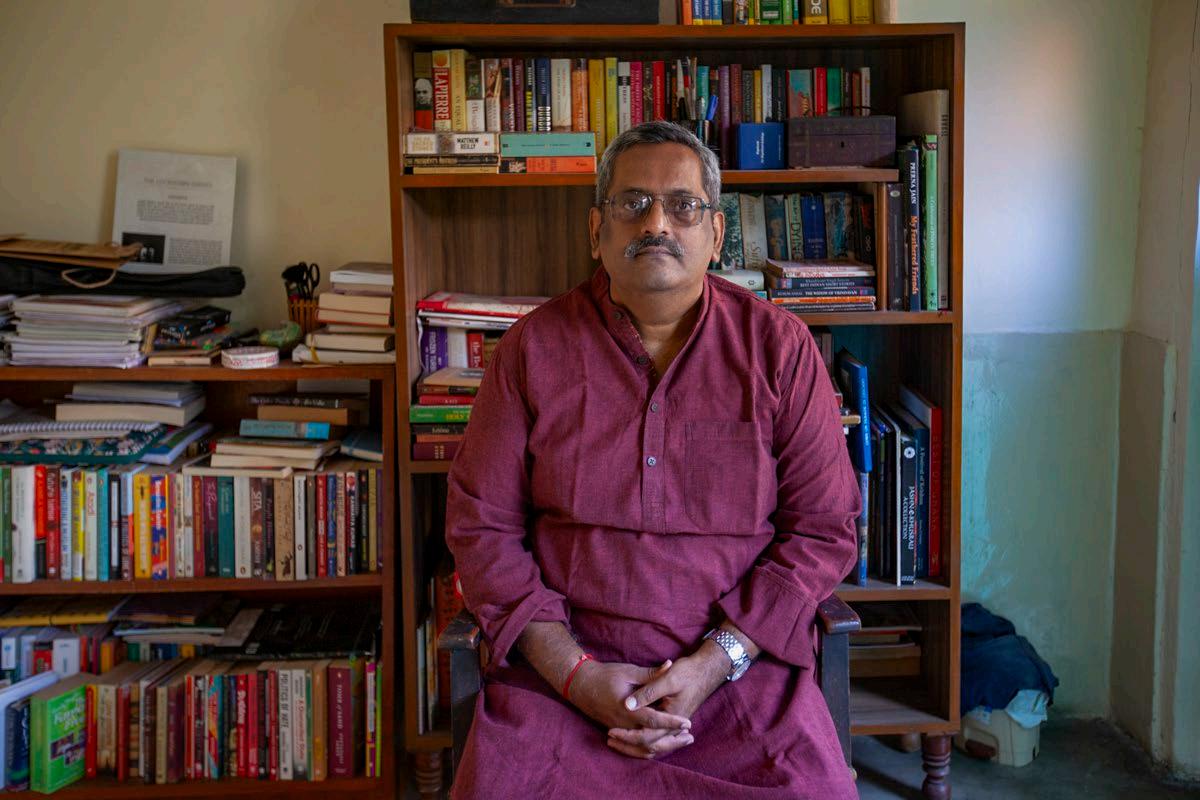

The three photographers featured in this book —Harvey Stein, Margarita Mavromichalis, and Umesh Gaur —present three distinct ways of seeing Chandni Chowk, each in a complementary style of photography. Stein's environmental portraits are theatrical, layered, and symbolic, offering a unique perspective on the city. Mavromichalis's immersive images show gesture, spontaneity, and vitality, providing a fresh and intriguing view. At the same time, Gaur's images are steadier and more archival in style, yet his perspective is equally captivating. Having photographed in Chandni Chowk for over 50 years, his work is an attempt to document rapidly transforming everyday life in the old city for future generations.

This essay presents a comparative analysis of the work of these photographers, focusing on their unique styles, the themes they explore in Chandni Chowk, and the impact of their work on the field of urban photography.

Author: Carol Huh

1500 words + about 10-15 images.

Chandni Chowk: A Photographer’s Paradise

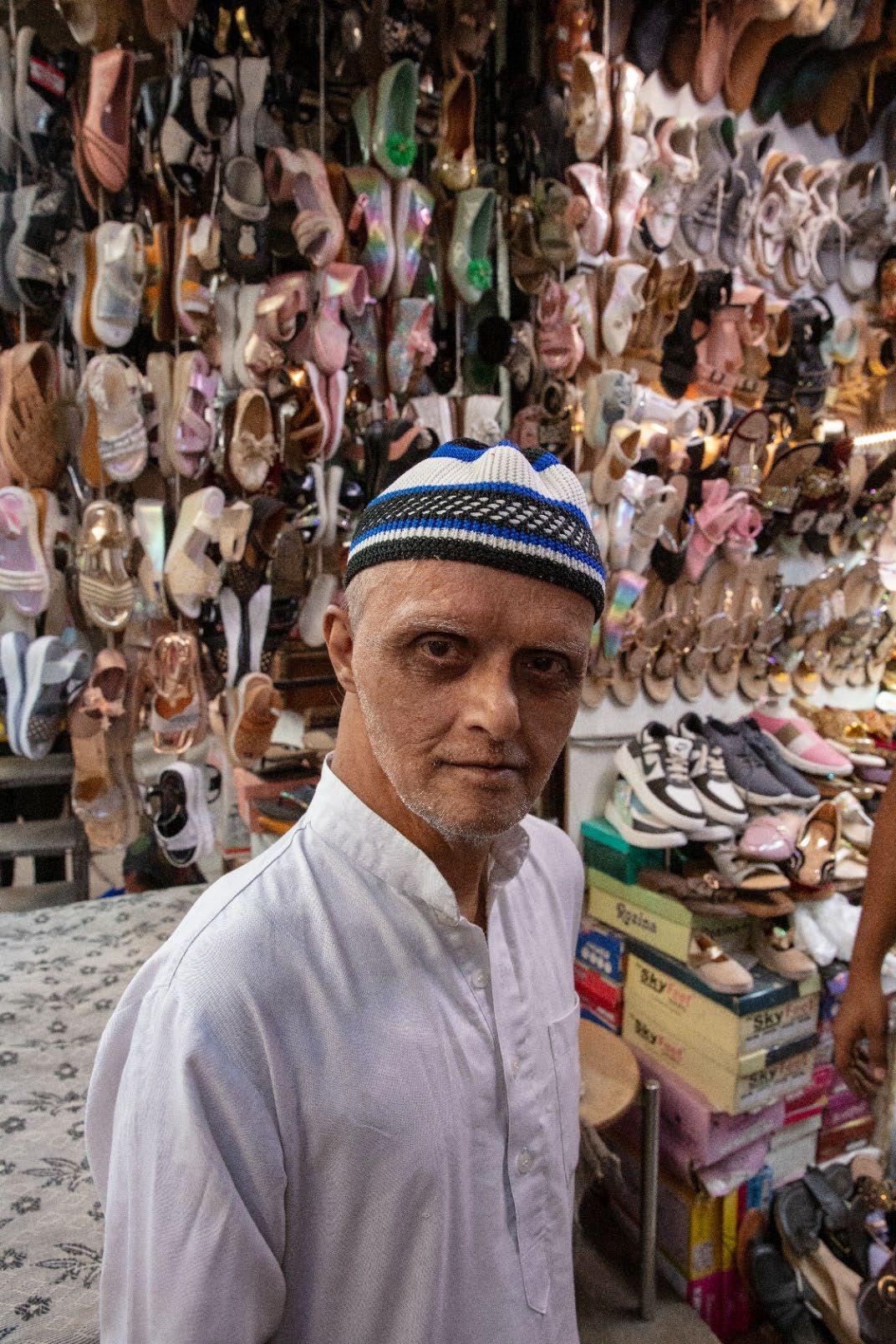

Chandni Chowk is a photographer's dream. The hustle and bustle, the colors, the smells of the streets, the bazaars, and the vibrant havelis of Chandni Chowk can be overwhelming on first encounter. Life at its chaotic best is lived on these streets, day in and day out. It is also a place that can overwhelm you and throw you into a dazzling storm of colors and sounds. Yet, within the chaos lie the kernels of beauty that the passionate, intrepid photographer can discover through patience, persistence, and resilience.

What truly distinguishes Chandni Chowk, in addition to its rich history, is the genuine warmth and openness of its people. Regardless of their busy schedules, the shopkeepers we photographed always made time to offer us chai. The artisans graciously opened up their workshops. The vendors were more than willing to be photographed, often pausing mid-task to strike a pose, as if life itself were a stage. We formed deep connections with many of these individuals, visiting them multiple times to capture their moods and emotions. They are not just subjects in our photographs; they're also in our hearts.

As we, Harvey, Margarita, and I, wandered through the vibrant lanes of Chandni Chowk, we did so without a fixed plan. Instead, we allowed the city and its people to be our guides, leading us into havelis, bazaars, temples, workshops, and iconic eateries. Harvey, a portrait photographer par excellence, was not just capturing appearances but the very essence of a person in a single frame. Margarita, with her