The legendary sinking of the Titanic (in 1912) is one of the most striking historical events of the modern era. The loss of the allegedly unsinkable ship, sunk by an iceberg shortly before the end of its maiden voyage to New York, is etched into our collective memory. The dream of groundbreaking progress and the notion that a different, better world was within reach, collided with fear of a doomsday scenario that could strike at any moment.

The story of the Titanic chimes with a fascination that is deeply rooted in popular culture, which has been manifested in the form of musicals, exhibitions and films. The best-known example is the 1997 movie epic starring Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio, which is still a favourite with the public.

Kunstmuseum Den Haag has been given the unique opportunity to show for the first time in the Netherlands original Oscar-winning costumes from the film. Showing them in combination with a variety of items from our museum’s own fashion collection dating from the first two decades of the twentieth century, and new perspectives by contemporary designers, has allowed us to paint a vivid picture of this turbulent period of history, and highlight links with the present day.

The years leading up to the First World War (1914-1918) can be seen as the end of an age dominated by the aristocracy and the wealthy classes. As the old order fell apart under the influence of global political tensions, great technological progress and social change, the sinking of the Titanic provided the perfect metaphor. Issues that were current at that time are increasingly matters that concern us today, including the impact of new technology, migration, social inequality, gender inequality and the threat of global war. While fascination with the Titanic generally focuses on the disaster and the wreck, the fashion worn onboard tells the story of people. Consigned to a terrible fate, they either perished or survived, in clothes that symbolised their status, origins and expectations.

Issues that were current at the time – like the impact of new technology, migration, social and gender inequality and the threat of global war – increasingly concern us today. For many of us, the most painful parallel with the Titanic is probably the sea, which plays a tragic and pivotal role at so many level’s in today’s society.

I am delighted with the contributions made by today’s innovative and inspiring makers. Their spectacular creations and ‘critical fabulations’ are invaluable, offering new perspectives alongside the historical and Hollywood costumes. Here, too, love and the hope of a better future are often the focus, as they were in the film Titanic, because we cannot survive without love and hope.

Many people devote a great deal of energy, enthusiasm and emotion to an exhibition like this. I would like to thank all the departments and staff at the museum involved in this project for their teamwork and their dedication to this exhibition (conceived by fashion curator Madelief Hohé), catalogue and programme of public events. Maarten Spruyt and Felipe Gonzalez Cabezas are responsible for the fabulous exhibition design. Jasper Abels and Alice de Groot are responsible for the amazing photography, and Loes Claessens beautifully designed this catalogue, which is published by Waanders Publishers. Cathelijne Blok arranged a number of unique loans of items for the exhibition. I would also like to express my gratitude to all those who have provided items on loan, as well as Fonds21 for its generous sponsorship.

Margriet Schavemaker Director, Kunstmuseum Den Haag

Why an exhibition about the Titanic and fashion? And why now? This exhibition is a response to recent fashions, which have been full of references to the 1910s. Suddenly, romantic dresses and blouses, with plenty of lace and broderie anglaise, appeared in the shops. These lovely, delicate fashions contrast starkly with the world around us, which is growing steadily harsher. Around the world, societies are increasingly polarised. For the first time in many years, the threat of global war is present. People are taking to the streets to protest against war and violence, or to campaign, once more, for women’s rights. Have we not seen this all before? Back in the 1910s, the time of the First World War (1914-1918)? Have we learned nothing from history?

Lots happened in the 1910s, a decade that began with boundless optimism. Fashion was alive with new colours and modern ideas. It was the time of radical young designers like Paul Poiret and Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel. Art, music and dance were alight with wild ideas and innovation. Modern technology made life more fun. The telephone, telegraph, cars, steamships and the first planes made humans feel invincible. And then, in 1912, came reports of a ship, the Titanic, that was said to be unsinkable. It was at any rate reputed to be larger, faster, safer and more luxurious than any ship ever built. On its maiden voyage, it would convey passengers from Britain to the United States in just five days. A trip from the old world to the new, as people saw it then. Britain was at the height of its power, including in terms of the extent of its colonies, and in the United States migrants were founding lucrative companies in cities where skyscrapers were being built. The world on board the Titanic was a microcosm of society. There was spacious first-class accommodation, where the wealthiest spent their time on their pleasure or business trip, generally travelling on a return ticket. There was a small second class, as the middle classes were not so big at the time. The majority of passengers were travelling on a third-class ticket, often a single, on their way to start a new life on the other side of the Atlantic. The ship was designed in such a way that the different classes never encountered each other, though the dogs belonging to first-class passengers were walked on the third-class deck. And in order not to ‘mar’ the first-class deck, the lifeboats (too few in number) were located on the second-class deck.

We all know how the story ended. The Titanic, the ‘unsinkable ship’, hit an iceberg in the night of 14 April 1912 and sank. It was a human tragedy, and a majority of the passengers and crew did not survive. A range of books, films and reports have ensured the disaster is imprinted on our collective memory. People are still fascinated by the Titanic, both the reality and the myth. The best-known film about the disaster is without doubt James Cameron’s 1997 epic Titanic, starring the young Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio. The film could be viewed online for many years, so younger generations are also aware of it, and it still feels topical today. The story told in the film is partly fictional, and partly an excellent representation of history. The costumes worn in the film were so well made that some of them look like the historical costumes in Kunstmuseum Den Haag’s collection. Deborah Lynn Scott, the designer, won an Oscar for best costumes in 1998. Kunstmuseum Den Haag is delighted to be able to share the most important costumes from the film with its visitors in this exhibition, alongside historical costumes from its own collection.

What did one wear on the Titanic? That all depended on who you were, and who you could be or wanted to be. Like society, the boat was divided by rank and station. A gentleman wore a hat, a labourer a cap. Clothes make the man, and when Jack wears a borrowed dress suit in the film, he is treated completely differently. Clothes reflected a person’s place in society. Not every woman could wear a silk gown from Paris with fabulous embroidery. Following Paris or London fashions was a sign of opulence in itself. Good-quality, ready-to-wear clothing was increasingly available for the new middle classes, but many people were forced to wear secondhand clothes, or had simple

clothing made for them, if they did not make it themselves. And these garments would not be made of lovely silk fabrics, but of practical, washable cotton or linen, and nice warm woollen fabrics. These were materials that the fashionable upper echelons would also wear, but in the form of a bespoke tweed suit, a wool travelling costume or walking costume, clothes for sports and leisure, cotton morning dresses or pretty summer dresses and children’s clothes. Leisure and luxury took precedence over necessity and practicality.

This exhibition shows the two sides of the coin: the fashionable costumes worn by the wealthy, and the practical, shabby clothes of those who were not in a position to follow the latest fashions. Most of the garments require little explanation: the social class of the wearer is immediately apparent. In this sense, the 1910s was a decade that was pivotal in fashion history. The focus of the exhibition is the period 1908 to 1918: from the moment when Paul Poiret issued his sensational Les Robes de Paul Poiret and Jeanne MargaineLacroix showed her ‘naked dresses’ at Longchamp to the end of the First World War. During this period, which has been rather overlooked, despite the fact that it was revolutionary in terms of fashion history, women’s fashions changed ever more rapidly. Corsets were abandoned and vibrant colours replaced the soft, powdery shades of the belle époque. This was the time of rebellious innovators like Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel, and Lucile, the idiosyncratic British designer who survived the Titanic disaster. It was a time when women demanded the vote and people had boundless faith in technological progress. Feminism was manifested in modern, practical costumes, in a society were class difference and exclusion were also perpetuated by fashion. Modern techniques were gaining ground, and the fashion world was bursting with modernity on the eve of the First World War. After the war, women’s fashion would change forever.

Since a story about the past is even more compelling in a contemporary context, Titanic & Fashion also includes work by several modern designers. Fashion is a mirror of its time, and their work reflects developments in society: issues we are concerned with, that we think and talk about, that perhaps keep us awake at night. The layers created by the combination of film costumes, historical fashion and modern work gives us plenty of food for thought: about the past, and about now. And how, as a society, we want to head into the future.

Madelief Hohé Curator of fashion and costume, Kunstmuseum Den Haag

ike the film itself, the costumes in Titanic have left a lasting impression. We all recall the scene in which the young Rose is introduced. A large car stops, and the driver steps out to open the door for his passenger. We see a white glove with purple details, black shoes and white stockings, a suit of white striped fabric with purple buttons, and, to top it off, a gigantic purple hat with an equally impressive bow in purple and white striped silk. Only once we have seen the entire costume does the wearer lift her head, giving us our first glimpse of Rose, played by Kate Winslet. The costume is introduced before the character.

Director James Cameron elected to show the costume in such detail for good reason. Before anyone utters a word, the viewer immediately forms an impression of the main character. Even those unfamiliar with the fashions of the time would immediately recognise that this was not just any passenger. Her tailored suit, inspired by men’s fashion, complete with a starched collar, gives Rose a formal but fashionable look, and at the same time tells us something about her personality. This is a modern woman. It must have been a great honour for the film’s costume designer Deborah Lynn Scott to have her work featured so prominently on screen. Her skill was also recognised in the form of the highly prestigious Academy Award (Oscar) for costume design, which she won in 1998.

Clearly, Scott did extensive research for the film, as the costumes are very convincing. They are appropriate to the time in which the story is set, the social status of the people wearing them, the occasion (evening or daytime) and, in the case of the leading roles, even the personality of the different characters. Dressing all the actors and extras was a huge task, on which more than fifty people worked for an entire year.1 To ensure that the entire thing looked as credible as possible, everyone wore a costume that looked authentic. All the female actors in first class, even the extras, wore a corset under their costume, to ensure that their posture was correct. Jewellery, accessories and matching shoes completed the look. Scott herself appears in the film as an extra. Dressed in a black evening gown and somewhat concealed behind a red fan, she descends the famous staircase to the dining room at the same time as Jack and Rose.

As with most costume dramas, some of the clothes were from costume rental companies, so some of the outfits and accessories can also be spotted in other films and series.2 However, a large proportion of the costumes were specially purchased and made for Titanic. Scott also collected many authentic costumes and accessories for the film.3 It was quite common and, above all, practical to wear authentic clothing in films. Even today, some costume rental companies have original items, though often they have been altered or adapted.

New costumes were designed and made for the character Rose. This was a challenge, as they had to be a match for the highly sophisticated original costumes from the era. 4 There were also practical challenges: several versions had to be made for some scenes, for example. Twenty-four versions were eventually made of the dress Rose wears on the night the Titanic sinks. One interesting detail: the thin fabric meant that Kate Winslet could not wear a wetsuit under her costume, as the other actors did to protect them from the cold when filming scenes in the water. For Winslet, therefore, it was ‘mighty cold’, as she herself put it. 5

A clear source of inspiration can be identified for some of the Titanic costumes designed by Scott. The suit in the opening scene, for example. This costume was quite clearly inspired by a suit from the January 1912 issue of French fashion magazine Les Modes. The original was a tailored winter suit, a ‘costume tailleur pour l’apres midi’ to be exact, from fashion house Amy Linker & Co., which specialised in ‘tailleurs’. (p.21) According to the caption, it was made of black-and-white striped wool velours, trimmed with velvet and skunk fur (‘skungs’).6 Tailored suits such as that worn by Rose were very popular in the 1910s, and there are many examples of similar suits from that time.7

Although Rose’s suit was not intended to be a precise copy – the fur was omitted, for example – it is striking that the elements that differ from the original also reveal something of the tastes of the 1990s. Above all, the silhouette was changed – presumably to appeal to a modern audience, or simply because a designer is always influenced by the time in which they live. The shoulders are more defined than they would have been in 1912, and the shape of the collar is more reminiscent of a suit from the 1990s. The biggest difference is probably in the height of the bustline, which was quite low in 1912 due to lower corsets. This was probably adapted for the film because the silhouette would otherwise have appeared strange to modern viewers. The make-up and even the hairstyles also betray late-twentieth-century influences, for the same reason. Think, for example, of Rose’s highly defined curls, and even what appears to be ‘guyliner’ (eyeliner) on her fiancé Cal. They are Hollywood stars after all.

The fact that costumes were adapted to modern tastes is also apparent in Rose’s coral red evening gown, a white version of which she wears in the final scene. It was probably inspired by a gown by Worth in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.8 Although it is not an exact copy, there are clear similarities, in the form of the tapering embroidered tulle edging in the skirt. The billowing bodice in the original is replaced in the film by a fitted bodice that shows off the figure, more in line with 1990s tastes. It is very appropriate that Rose’s gown should be inspired by a design by Worth. For decades, Maison Worth was the best-known fashion house in Paris, and was particularly popular among the American ladies who had the resources to pay its exorbitant prices.9

In the film, the costumes serve the same purpose as outfits did in the age of the Titanic: they signal which class a person belongs to. Think, for example, of the scene in which Jack, wearing a borrowed dress suit, makes his entrance in the first-class dining room. He immediately receives a friendly welcome from a steward. When, a day later, he walks around first class wearing his own cloths (corduroy workman’s trousers and a shirt), the same steward makes it clear he is not welcome there.

The difference between the clothes of the first- and third-class passengers is huge, mirroring the social distance between the classes. While the firstclass passengers change their expensive, sophisticated outfits several times a day, the third-class passengers have fewer costume changes. The clothes they wear are much more practical in terms of their design and materials than those of the people from the higher social classes. Jack, like many of his fellow steerage passengers, generally wears work clothing made of sturdy fabric. Apart from the borrowed outfit, we see him either in a collarless shirt, or in a brown work shirt made of heavy cotton. In both cases, he wears light brown corduroy trousers.

The stark contrast between the clothes worn in first and third class is very noticeable after the first-class dinner, when Rose accompanies Jack to a party below deck. The clothes worn by the steerage passengers are very diverse, as are their backgrounds. While the men in first class all wear the same solemn black dress suits, white ties and waistcoats, the men below deck wear much more varied outfits, although they are mostly in earthy tones. Some of the women in third class wear regional costume and accessories that show where they come from. (p.72) Although Rose’s clothes are perfectly appropriate for her life among the social elite, they turn out to be a hindrance in steerage. She kicks off her high heels as she dances, and asks Jack to hold her train out of the way when, in a moment of abandon, she shows that she can stand on her toes.

The development of Rose’s character from bored, constrained young lady to self-assured, unprejudiced young woman, is handily reflected in her costumes. There is a world of difference between the stiff suit with the giant hat

1 Heart of the Ocean: The Making of 'Titanic' documentary (1997).

at the start of the film, and the soft colours and fabric of her gown and her loose hair on the evening of the disaster. The fact that Rose has had enough of her first-class life and the clothes that go with also becomes clear in the scene where she lets Jack draw her. Rose specifically chooses to have herself portrayed naked because, as she says, ‘The last thing I need is another picture of me looking like a porcelain doll’. And so one of the best-known moments in this celebrated costume drama is in fact one where no clothes are worn, and an independent modern woman is born.

2 The online platform recycledmoviecostumes.com, for example, has several costumes and accessories worn in films and series before or after Titanic (1997).

3 Emma Robertson, Deborah L. Scott: “The heart of it is always the same”, interview in The Talks . Accessed via the-talks.com. in July 2025.

4 Idem.

5 Heart of the Ocean: The Making of 'Titanic' documentary (1997).

6 Les Modes : revue mensuelle illustrée des arts décoratifs appliqués à la femme, 1 January 1912, p. 38. Accessed via gallica.bnf.fr. in July 2025.

7 There is for example a fashion print in La Femme Chic of a woman wearing a similar striped travelling costume, and in 1912 there was a picture on the cover of a Molstad&Co catalogue showing a woman in another similar striped suit, complete with large purple hat; Kunstmuseum Den Haag and Museum Nord (Norway) respectively.

8 Victoria& Albert Museum, London, inv.no. T.57-196.

9 Chantal Trubert-Tollu et al., The House of Worth 1858-1954. The Birth of Haute Couture , London 2017, p. 28.

he sinking of the Titanic in 1912 was a disaster that attracted global attention, and continues to intrigue many people to this day. Countless stories about the Titanic and its passengers have attained the status of myth, partly as a result of the 1997 film Titanic. Many, for example, regard the main characters from the film, Rose and Jack, as actual people, and ‘diehard’ fans even go so far as to seek ‘evidence’ of their existence. It is indeed true that some characters in the film were real people, including Margaret (‘The Unsinkable Molly’) Brown (1867-1932); Bruce Ismay (1862-1937), director of the White Star Line; Thomas Andrews (1873-1912), chief designer of the Titanic; John Jacob Astor (1864-1912), an American businessman, owner of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and the richest man on the Titanic; and Lord and Lady Duff Gordon (1862-1931 and 1863-1935 respectively). Lady Duff Gordon was the famous fashion designer Lucile, whose company had branches in London, Paris and New York – but more of her later. (p. 70) So what is fact, and what is fiction?

In the film, Jack Dawson ends up on board the Titanic by accident, winning a third-class ticket in a poker game. The character Jack Dawson was born in Chippewa Falls in Wisconsin, United States of America, around 1892. His parents died when he was young. Jack had some artistic talent, and a preference for drawing nudes.1 In the film he soon meets up with his co-star, first-class passenger Rose Dewitt Bukater, also an American. Rose was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1895. In the film she is travelling home from Europe with her mother Ruth to marry her fiancé, one Caledon ‘Cal’ Hockley, in New York. After the death of Rose’s father, the Dewitt Bukater ladies had been left penniless, and Ruth has decided that Rose must marry for money. She regards Cal Hockley, the spectacularly wealthy son of Nathan Hockley, a Pittsburgh steel magnate, as the ideal husband for Rose.2 However, her daughter wishes to live freely and independently, and hates the idea of marrying for money. In a desperate attempt to escape her situation, she tries to take her own life by jumping off the stern of the Titanic. This is where our two heroes meet … Jack saves Rose and the rest is movie history.

But what is the truth of the situation? Did Rose De Witt Bukater and Jack Dawson really exist? Briefly and simply: no. And that is a fact. At the same time, this is where the myth begins. For there was in fact a J. Dawson on board the Titanic. His given name was not Jack, however.

At Fairview cemetery in Halifax, Novia Scotia, Canada, among the other graves of Titanic victims, is grave number 227.3 The inscription on the small stone reads: “Dawson Died April 15, 1912”. When Dawson’s body was recovered from the ocean, it was clear from his clothing that he was a member of the crew. We know that he was wearing dungarees.4 Stokers and trimmers on a steam-driven ocean liner would wear white canvas dungarees, to ensure that they were more visible in the poorly lit boiler room, and any injuries would also become apparent more quickly. 5 They found Dawson’s ‘National Sailors and Firemen’s Union’ card in his jacket pocket.6 But this J. Dawson was actually Joseph Dawson, born in Dublin, Ireland in September 1888. He grew up in poverty, but his father trained him as a carpenter, and he attended a Jesuit school. After the death of his mother, he and his younger sister were sent to relatives in Birkenhead near Liverpool in England. There, he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, and went to work at a large military hospital in the small town of Netley near Southampton. One day he met Nellie Priest, sister of a friend who worked as a stoker on an ocean liner, and fell in love with her. He left the army in June 1911 to go and work as a ‘trimmer’7 on one of the large ocean liners of the White Star Line.8 He departed for his final journey on board the Titanic on 10 April 1912.

After the 1997 movie Titanic, grave number 227 became a place of pilgrimage for all Jack Dawson fans who mistakenly believe that their film hero lies buried there.

And what of Rose? Rose is a completely fictional character. Or is she? It turns out that director James Cameron took inspiration for the character of Rose from dada artist Beatrice Wood (1893-1998), who became famous, particularly in later life, for her ceramic art. Cameron read her biography while making preparations for the film.9 Beatrice Wood, from a wealthy, traditional American family, abandoned her life of privilege to become an artist, just as Rose in the film leaves her old life behind her to lead an independent life, free of her demanding mother. But that is where the similarity ends. So here, too, fact and fiction are intertwined.

1 Via: Jack Dawson, Titanic Wiki, Fandom Accessed on 2-6-2025.

2 Via: Caledon Hockley, Titanic Wiki, Fandom Accessde on 2-6-2025.

3 Number 227 refers to the 227th victim or body recovered after the sinking of the Titanic. Via: The Real Jack Dawson Accessed on 2-6-2025.

4 “His dungarees and other clothing immediately identified him as a member of the crew when his remains were recovered” Via https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/the-real-jackdawson.html Accessed on 2-6-2025.

5 Via: https://www.reddit.com/r/titanic/comments/18os5ju/why_did_the_firemen_and_coal_trimmers_on_the/ Geraadpleegd op Accessed on 2-6-2025.

6 His number and name are given on his union card, and this was how J. Dawson was identified. Via: The Real Jack Dawson Accessed on 2-6-2025.

7 A ‘trimmer’ or coal trimmer on a large ship like the Titanic was responsible for moving coal in the engine room’s coal bunkers, to ensure it was evenly distributed and the ship thus remained stable. This ensured the ship did not start to list, or even capsize. Via: Kolendrager –3 definities –Encyclo and via: wat is een trimmer op een schip als de Titanic –Google Zoeken Accessed on: 2-6-2025.

8 He first spent a few months on the Majestic, a ship built in 1889 for the White Star Line, before joining the crew of the Titanic. Via: The Real Jack Dawson and via: Majestic (ship) –Wikipedia Accessed on 2-6-2025.

9 Via: Beatrice Wood –Wikipedia Accessed on 2-6-2025.

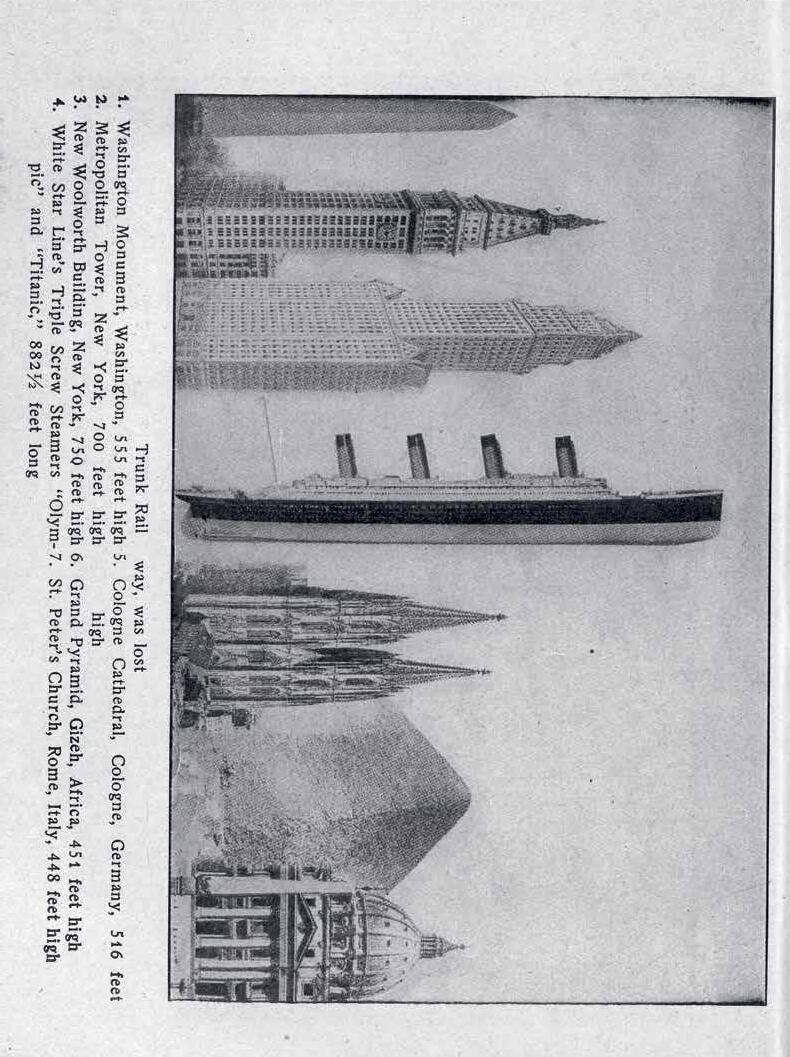

Drawing from c. 1912 comparing the size of the Titanic with well-known buildings around the world.

p. 2

Fashion plate featuring woman’s tailored suit by Jeanne Paquin, in: La Femme Chic , 1915.

p. 14

Kate Winslet as Rose in the opening scene of the film Titanic (1997), wearing a modern tailored suit and hat ( Boarding Suit ), based on fashions in 1912. p. 16 Rose and Jack on the first-class deck of the Titanic in the film of the same name. Rose’s day dress is similar to a yellow velvet dress by Gustav Beer in Kunstmuseum Den Haag’s collection.

p. 15

Gustav Beer, Yellow silk evening gown with floral motifs embroidered on the bodice, Paris c. 1917-1919. Probably worn by Baroness Ada van Hardenbroek van Lockhorst (1889-1971).

p. 17

Maison de Bonneterie, Woman’s suit in lavender silk faille, c. 1913-1914, worn by Adelaide Angelique Mathijsen (1873-1957); Hirsch & Cie, Gown in light grey and lilac satin with embroidery and sailor collar, c. 1915-1917; Morning suit, M.S. de Jong, The Hague, 1913, worn by L. den Beer-Poortugael Esq.; Yorkshire terrier (mounted; this breed was fashionable at the time), on loan from Museon.

p. 18

Photograph of Mrs James J. 'Molly' Brown (1867-1932), one of the survivors of the Titanic, who appears as a character in The Unsinkable Molly Brown (1964), S.O.S. Titanic (1979) and Titanic (1997).

p. 19