FROM STATEME N T TO STYLEICON

FROM STATEME N T TO STYLEICON

PAUL REM MADELIEF HOHÉ

TIRZA WESTLAND

CÉCILE NARINX

FOREWORD

Nothing is more personal than clothing. It is literally right next to our skin. It is tangible, and makes its presence felt. The fabric, texture, line, colour, sheen: they all contribute to the overall effect. It stimulates all our senses. The rustling of gowns at a ball – what more immediate evocation of history could one imagine? Clothes make us who we are, or who we want to be. It is no coincidence that costume dramas are so popular, and fashion exhibitions attract such a wide range of visitors.

Dress codes: rules about what to wear. Sometimes specified on an invitation, but often in the form of unwritten rules about ‘the done thing’. Dress codes have always been important at court. A gala dinner, wedding or a tennis match – there was a dress code for every occasion. Those who ignored the rules would exclude themselves from the group. There have always been dress codes, and they play a role not only at court, but also in daily life. We dress in a style we feel comfortable with, whether consciously or not. We dress to belong, or to set ourselves apart.

This exhibition explores dress codes from the past and from the present day. And what do we find? Rules change. Dress codes that in the past applied only at court are now part of popular culture, having shifted from the palace to the red carpets of Hollywood, Cannes and New York. Celebrities, today’s style icons, appear on the red carpet like kings and queens. A star wishing to make a statement will generally look to royal dress codes.

‘Dress Codes – From Statement to Style Icon’ is the first major fashion exhibition to be staged at Paleis Het Loo since it reopened in 2023. It has been developed in collaboration with Kunstmuseum Den Haag. We would like to express our gratitude to the Kunstmuseum and, in particular, to fashion and costume curator Madelief Hohé, fashion and costume historian Tirza Westland, and head of photography and design Alice de Groot for their pleasant and professional collaboration with our project team. The core team at Paleis Het Loo consisted of senior curator Paul Rem, programme designer Adjo Tjon-A-Tsien, marketing manager Laura Meerveld and project lead Marijntje Knapen. The project team was supported by many other staff at Paleis Het Loo, including conservator Hans Schuite.

This book, published to accompany the exhibition, will make the unique costume collection at Paleis Het Loo – whose core consists of items generously provided on long-term loan from the Royal Collections in The Hague –permanently accessible to the public, as well as linking it to contemporary fashion. Many of the works on show can also be accessed via our online collection and Modemuze. The publication is divided into three sections: historical court dress from 1880 to 1940 (by Paul Rem), dress codes today (by fashion journalist Cécile Narinx) and the impact of court dress codes on popular culture (by Madelief Hohé). These sections are interspersed with highlights from the Royal Collections, and the collections of Paleis Het Loo

and Kunstmuseum Den Haag, the latter showcasing court outfits and clothes worn in circles close to the court. Many of the clothes and accessories were recently photographed for this publication, most of them in the historic setting of Paleis Het Loo, Paleis Lange Voorhout (Queen Emma’s palace) or at the Royal House Archives in The Hague. The publication also includes some historical photographs of the Dutch royal family that have never previously been published.

The exhibition has been made possible thanks to items loaned by many museums and private collections. We are particularly grateful to H.M. the King, H.M. the Queen and Their Royal Highnesses Princess Amalia, Princess Irene and Princess Mabel, who have all generously loaned us items of personal property. Thanks also to the Royal Collections in The Hague for the many examples of royal clothing and accessories on long-term and short-term loan.

Our partner Kunstmuseum Den Haag has also loaned a significant number of costumes worn in circles close to the royal family. The other lenders are:

ABN AMRO History Department / long-term loans from the Dutch Silver Museum, MoMu | ModeMuseum Antwerpen, Dries van Noten Antwerp, Princess Diana Museum | The Princess & The Platypus Foundation Los Angeles, Givenchy Patrimoine Paris, Viktor&Rolf Amsterdam, Dutch Cavalry Museum Amersfoort, Gucci Archive Florence, Elie Saab France (SARL), Guo Pei Peking/Paris, Frans Hoogendoorn The Hague, Patrimoine Schiaparelli, Paris, Christian Siriano New York, Geschiedkundige Vereniging OranjeNassau, Stichting tot Instandhouding van het Museum van de Kanselarij der Nederlandse Orden, Edwin Oudshoorn Leiden, Toppers in Concert, Studio Exactitudes Rotterdam and various private lenders.

The beautiful exhibition design is the work of Tatyana van Walsum (spatial design) and Marline Bakker (graphic design). Marline also designed the catalogue. Our collaboration with Marloes Waanders and Stefanie Klerks of Waanders Uitgevers was as enjoyable and professional as always. Thanks also to the authors listed above and to picture editor Angelique van den Eerenbeemd.

The museum of Paleis Het Loo would like to take this opportunity to express its gratitude to its main benefactors, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science and the VriendenLoterij lottery. We would also like to thank the following funds and sponsors for supporting the Dress Codes exhibition and publication: Cultuurfonds, Fonds 21, the Mondrian Fund, Apeldoorn municipal authority, Zabawas, Gravin van Bylandt Stichting, Stichting Hendrik Mullerfonds and the Dutch Costume Association.

We hope you enjoy your visit to Dress Codes and the publication that accompanies it.

Frans van de Avert,

Director

Annette de Vries, Head of Research, Collection & Programmes

← ←

Queen’ ensemble by Viktor&Rolf Autumn/winter 2021, courtesy of Viktor&Rolf, Amsterdam; background, interior of Paleis Het Loo, Apeldoorn

→ Gown

Worn by Princess Maria of Prussia (1855-1888) in 1878, on her engagement to Prince Hendrik (1820-1879, brother of Willem III.

Maker unknown, 1878

‘Size

Silk, cotton, metal Kunstmuseum Den Haag

Paul Rem

Paul Rem , Madelief Hohé, Tirza Westland

Cécile Narinx

Paul Rem , Madelief Hohé, Tirza Westland

Madelief Hohé

DRESS CODES

FROM STATEMENT TO STYLE ICON

Dress codes are not exclusive to any particular period. This is the story of the Dutch court in the period 1880-1940. This was the age of three female monarchs: Queen Regent Emma (1858-1934), Queen Wilhelmina (1880-1962) and Princess Juliana (1909-2004). Their wardrobes have largely been preserved as part of the Royal Collections. The clothes and accessories were worn at important occasions like weddings and investitures, and also at court festivities or out horseriding – always in line with protocol and the appropriate dress code for the event. Fashion was important in court culture. The right clothes allowed a monarch to stand out from the rest of the court, its staff and visitors. There were dress codes for all kinds of events, from grand ceremonies to outdoor sports, either defined on paper or existing as an unwritten rule. There could be no court life without a dress code in those days, and to be a player, a person had to know the codes and have the money to comply, otherwise they would be excluded. This raises many questions. What exactly were those dress codes? Who wore what at court? How did people ensure they didn’t commit a fashion blunder? And who made the fashionable attire worn by monarchs, ladies-in-waiting and footmen?

The exhibition Dress Codes answers all these questions. The project, initiated by Paleis Het Loo, is a collaboration with Kunstmuseum Den Haag, which has the largest fashion collection in the Netherlands. A logical partnership for this venture, given that the royals’ clothes are kept by Royal Collections and Paleis Het Loo, while those of their ‘entourage’ (ladies-in-waiting and others in court circles) are at Kunstmuseum Den Haag. The two institutions have collaborated on fashion projects in the past. In 1998 Paleis Het Loo in Apeldoorn organised an exhibition and published an accompanying catalogue entitled In Royal Array: Queen Wilhelmina 1880-1962, combining the knowledge and skills of the museums’ costume curators, Elizabeth Braam and Ietse Meij. In 2006 curators Trudie Rosa de Carvalho of Paleis Het Loo and Madelief Hohé of Kunstmuseum Den Haag worked together on Hague Court Fashions, staged at Kunstmuseum Den Haag (then Gemeentemuseum Den Haag). These two institutions, in Apeldoorn and The Hague, have joined forces again for Dress Codes. And the costumes are travelling back and forth again between the two places, just as they did in the days when they were in use, and were transported by carriage or train to ensure that the wearer looked absolutely perfect, whether outdoors in the summer at Apeldoorn, or at one of the many parties and other events that took place at the court in The Hague in the winter months.

→ King Willem-Alexander and Queen Máxima on Prinsjesdag (official opening of parliament) in 2016.

The king is wearing a morning suit, Queen Máxima is wearing an evening dress by Claes Iversen.

Dress codes might seem like something from the distant past, but nothing could be further from the truth. Dress codes are all around us, whether we are aware of them or not. People often like to express who they are, or the group they belong to, or would like to belong to, through what they wear. Cécile Narinx, fashion journalist and former editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar draws on her many years of experience to discuss today’s dress codes. Her essay ties in seamlessly with the Exactitudes series, in which Dutch photographers Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek have been documenting unwritten dress codes for years. But that is not all. Over the years, court dress codes have increasingly become part of pop culture. While the strict protocol at the Dutch court declined after the Second World War, international dress codes also changed. Fashion became more democratic, as popular culture grew in importance. And who did the film stars, pop stars and, later, even reality TV stars, influencers and YouTubers imitate in their dress style for galas and important events? That’s right: for those important red-carpet moments they copied the court culture of yesteryear, with its ball gowns, long trains, tiaras, expensive embroidery and fur (real or fake).

All of these royal dress codes are still observed by celebrities at society events, sometimes in unique ways, as recently at the Cannes Film Festival (2025) where, a day before the event, guests were urged to keep ‘nudity’ to a minimum, in response to the ‘naked dress’ trend at recent red-carpet events. Backpacks and sneakers were also explicitly forbidden on the red carpet, as well as gowns with trains that might form an obstacle to others. Of course some celebrities paid no heed whatsoever to these dress codes, and there were plenty of naked dresses and long trains at Cannes. Either you’re a style icon, or you’re not. Courtly imagery is still very much alive in pop culture, where the low-cut gown and long train will never go out of style. Even though, at the same time, many European monarchies are gradually modernising, and some have explicitly abolished dress codes. Modern royals increasingly dress like everyone else – their way of making a statement.

In short, this is a story that takes us from statement to style icon. Or, as designers Viktor & Rolf remarked in connection with their own Royals collection (2021), ‘Everybody can be a queen, and everybody is his or her own creation’.

Paul Rem, senior curator at Paleis Het Loo Madelief Hohé, curator of fashion and costume at Kunstmuseum Den Haag

DRESSCODES AT THE D U TCH COURT 1880—1940

PAUL REM

but it would have been inappropriate to appear better dressed.

← Queen Wilhelmina and her ladies-in-waiting Queen Wilhelmina (right) had her photograph taken with her ladies-in-waiting in the park behind Paleis Het Loo. From left to right, they are Anny Rengers (seated) and sisters Bella and Elisabeth Sloet van Marxveld. The queen is wearing a fashionable dress with a train. Her outfit is completed by a hat, parasol and gloves. The ladiesin-waiting followed the queen’s example with their outfits,

Photo J.J.M. Guy de Coral, 1908 Royal Collections, The Hague

← ← Queen Wilhelmina’s court train Paris, Nicaud Paris, circa 1900 Silk, silver thread, glass pearls Paleis Het Loo, on long-term loan from the Royal Collections, The Hague

On 10 January 1879, the Opregte Haarlemsche Courant newspaper described the new queen’s wedding dress for its readers.

‘The Bride’s outfit consisted of a dress of white silk with silver embroidered flowers, and a royal ermine covered her shoulders.’

The black specks on the dress are silver tassels that are now tarnished black. Paris, Corbay-Wenzel, 1878 Silk, cotton, linen, silver thread, glass pearls Paleis Het Loo. On long-term loan from the Royal Collections, The Hague

Queen Emma’s wedding dress

Queen Emma’s (1858-1934) arrival in the Netherlands ushered in a revival of court life. King Willem III’s first wife, Sophie of Württemberg, had performed her duties as queen to perfection, but in the final years of her life she was no longer a vibrant force at the centre of the Dutch court. This changed when Willem III remarried, taking the young German princess Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont as his second wife. The royal wedding took place in the chapel of Emma’s family castle in Arolsen on 7 January 1879. The king wore his Royal Navy admiral’s uniform, with the insignia of his highest Dutch and Waldeck honours. Emma wore a white satin ballgown in the latest Paris fashion, with a train, a smooth bodice and short sleeves. She also wore an ermine cape in the cold chapel. The wedding ceremony was followed by three days of celebrations. The couple then left by train for the Netherlands, to spend their honeymoon at Paleis Het Loo. Emma’s mother had spent a fortune on her trousseau, which travelled with her in trunks. Emma had barely set foot on Dutch soil when the sudden death of Prince Hendrik, the king’s brother, brought the festive welcome to an abrupt end. A series of receptions, balls and dinners, carriage tours and theatre visits had to be postponed, as the chief master of ceremonies announced a period of court mourning on behalf of the king. For four weeks, the court would be in full mourning, followed by four weeks of half mourning and, finally, four weeks of light mourning. The notice was published in all newspapers, because although the pomp and circumstance was to be toned down for three months, some official receptions went ahead. Guests were expected to observe the dress codes for court mourning, published in the annual State Almanac.

The splendour of court life

Guests were only too happy to conform to the rules of court. An invitation to a ceremony at the palace, in the radiant proximity of the royal family, was a privilege. The court was the epitome of civilisation in the age of King Willem III and Queen Emma, and later of Queen Wilhelmina, up to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1940. It was the diplomatic and cultural centre of The Hague, the monarch’s official residence, and of the Netherlands itself –a European nation and colonial power. Protocol, formality, the glamour of expensive outfits, uniforms, jewellery, candlelight, music and footmen in livery reflected the grandeur of the reigning monarchy, which had a strong international orientation. European courts were in competition with each other, and to match their rivals, life at court had to be glamorous. Tradition and continuity have long been important aspects of monarchy. Receptions that proceeded according to fixed formulas, conforming to old rules, reaffirmed the allure of the royal family and its court.

a

Paris, Mellerio dits Meller, 1888 Tortoiseshell, gold, diamonds, paper Royal Collections, The Hague

Emma’s Mellerio fan

Queen Emma owned many fans. One of the most costly was a painted fan with ribs of tortoiseshell decorated with diamonds and rubies, made by the Paris firm Mellerio dits Meller. It was part of a matching set of jewellery that also included a tiara, a choker, a breast ornament, a brooch,

bracelet and a pair of earrings.

Court ranks

A reception at court might have a particular dress code. It gave the court extra lustre. Dress codes ensured that people’s rank at court and in society was instantly recognisable. At official receptions, male servants would wear their finest full dress livery. The gentlemen of the court and men who held public office wore their uniform. The ceremonial dress uniform would be expensive and, depending on the post held by the wearer, be embroidered with gold and silver and symbols referring to their post. Footmen had full dress livery. If a gentleman did not have a ceremonial dress uniform, he could wear a simple but elegant dress suit, with insignia and a sash making an impressive addition. Military personnel wore their dress uniform. Clothing therefore indicated rank at a quick glance.

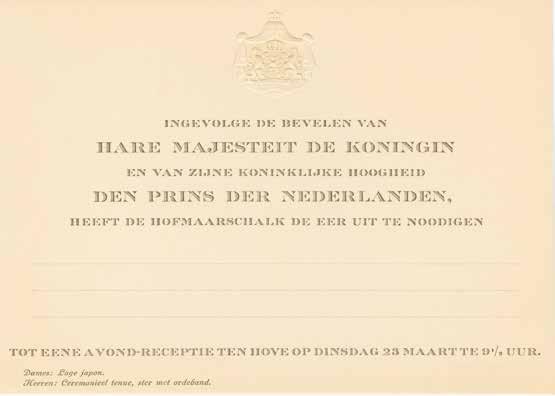

Invitation with dress code, 1926

This invitation to a gala evening at the Royal Palace in Amsterdam requests that ladies wear a ‘low-cut gown’, a dress with décolletage, in other words. Gentlemen should wear their ceremonial uniform: a full dress uniform for military personnel, an official uniform for dignitaries, and a dress suit for other gentlemen. Invitations were still written in French in The Hague at the time.

Royal Collections, The Hague

Wool, silk, leather, gilded metal, gold thread, cockerel feathers Paleis Het Loo, on long-term loan from the Foundation for the Preservation of the Museum of the Chancery of the Netherlands Orders; Paleis Het Loo, on long-term loan from the Royal Collections, The Hague; Paleis Het Loo

Three dignitaries in full regalia From left to right: an envoy, Master of the Hunt and Grand Master of the Royal Hunt.