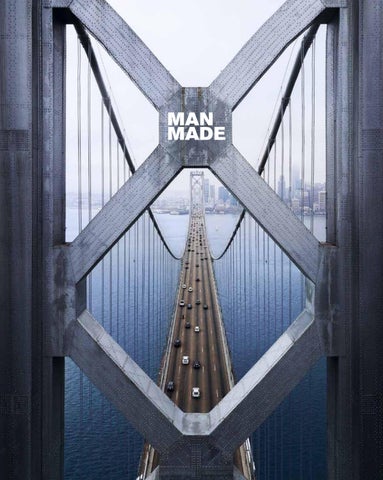

MAN MADE

SÉBASTIEN NAGY

Aerial Views of Human Landscapes

TO BE FREE AS A BIRD may be a cliché, but that is exactly how it feels to me when I view the world from the air. Even before I owned a drone I would climb onto rooftops to photograph my city. I found it incredibly soothing to look down at the teeming streets from my elevated position. It gave me a sense of freedom and deliverance.

I have always been inspired by the vibrance and density of cities. An aerial image contains countless hidden stories that reveal themselves one by one as you study the photograph more closely. I like to draw my viewers in and let them explore the details that take them beyond the initial impression. In nature I let my calmer side prevail and the images are more tranquil, but I still look for the geometric shapes and directional lines that mirror the architecture of cities. This strict aesthetic style is a thread that runs through all my work.

Since I started taking photographs it has been an ambition of mine to compile them in book form. As much as I enjoy sharing them on social media or as prints for clients, a bound collection is the best way to bring my work together and give people a broader view than a single photograph can offer. I believe, too, that you haven’t truly lived until you have travelled and seen for yourself that the world is a richer place than anyone can imagine. In learning about other people, their cultures and their way of life, we also learn something about ourselves. So let me take you on a journey through my photographs that brings new perspectives to both the world around you and the world inside yourself.

Sébastien NagyIntroduction

About Sébastien Nagy – 248 Index – 250

Credits – 256

SÉBASTIEN NAGY began his career with a handheld camera and a head for heights. He scoured the rooftops of Brussels in search of new ways to portray his home city. As his reputation on Instagram grew, he began travelling around Europe in search of new skylines and skyscrapers. But the breakthrough came out of the blue, when a stranger contacted him about an exciting new technology that would transform the way he viewed and photographed the world.

How did your interest in drone photography begin?

I started out in 2015 photographing Brussels from the rooftops, because drones weren’t widely available then. I was inspired by the Instagram feeds of photographers in cities like New York and Hong Kong who took pictures of these beautiful skylines. I was really intrigued by this style of photography and wanted to show Brussels from a different perspective. I’d been doing it for a few months when I got an email from someone in Brussels who followed me on Instagram and admired my work. He said he’d just bought a drone and asked if I wanted to meet him and try it out. It was a sheer coincidence because I didn’t know this person at all, but I thought: sure, why not?

How long did it take to realise it would revolutionise your photography?

The first time I took the drone out it was incredible. I’d been spending months going up and down staircases, sometimes climbing 50 floors for just one shot. Now I could go to a park, send up the drone and get the exact angle I wanted. After only a few minutes I said, I need save up and buy one of these for myself.

How has the technology and your technique advanced since you started using drones?

The drones themselves haven’t changed much, but they’ve evolved just like phones. The camera is more powerful now than when I started in 2017 and has a much bigger range. These days it’s almost as good as an SLR. In the beginning there were people who argued it wasn’t really photography because I was basically just a drone pilot, but now I can use all the same settings as someone with a handheld camera. For example, if you’re taking photos of cities from the air at night you need to know how to set up the camera so the pictures are properly exposed and don’t come out blurred. It’s not just about steering the drone.

Were you surprised to win the aerial photographer of the year award?

Very much, because it was the first competition I’d entered. I only knew about it because a friend of mine told me there was a contest in France and there were people from around 50 countries taking part. So I sent in some photographs and then forgot all about it until I got a call from a French number. They told me I’d won, so I asked them what category, and they explained I’d won several categories. Not only that, but the jury had awarded me first prize overall. I was amazed. Since then I’ve submitted my work for more prizes, because it’s a chance to meet new people and learn more about the latest developments in aerial photography.

Have you changed your approach since winning the competition?

Not especially, because it was good enough to win, ha ha! But it was interesting to see who’d won in other categories such as

nature, people and atmosphere, because some of the photos were in a completely different style from mine, so it gave me an insight into other ways of taking aerial photographs.

Do you see aerial photography as a potential career?

To me there’s a difference between photography as an artistic field and making a career out of it. Winning the competition was all about art, but it’s easier to succeed as a photographer taking pictures of weddings or real estate. Those are things where you know there’s always demand and they give you a steady income, whereas if you’re an artist you can sell a photograph for € 5000 but your income goes up and down a lot more. So at the moment I see my artistic photos as a hobby rather than a way of earning a living. I don’t see myself buying a house in two years from my success on Instagram. You see people on Instagram who are fulltime artists and put everything they have into selling editing workshops and filters. But they send out 150 emails a day to prospective clients and invest in advertising, and that’s not the way I want to go. Building up your follower count involves a lot of work and it’s risky, because what do you do if Instagram isn’t there anymore? You don’t want your whole career to be dependent on one platform.

What do you look for in the locations and the subjects you photograph?

Something I like, first of all! I spend a lot of time on Google Earth because it’s the app that’s most similar to the photos I take. I don’t so much look for specific objects as a sense of the place. I’m drawn to things in the lines of the architecture or the landscape that appeal to me. And I’m always researching locations. If I travel

abroad to meet somebody I’ll take 50 screenshots of the area from above so I know what sort of photos to take when I get there.

Do you ever have difficulties with local laws when you’re flying your drone?

There are restrictions on using drones all over the world, but some places are particularly strict. I went with a friend to Giza to shoot the pyramids in a collaboration with a local hotel. When we got to the airport we were greeted by a diplomat who’d been put in charge of looking after us and dealing with customs. He spoke to the security officers in Arabic and made sure we got our electronic equipment through, because they search all your bags before you leave the airport. Without his help it would have been a lot more difficult, so we were very lucky. Even then we were careful not to use the drone too much on site and only flew twice in five days, but the pictures were sold and shared hundreds of times, which was really pleasing.

How much are you influenced by your followers on Instagram?

I try to do things for myself first of all. On Instagram you have a tendency to scroll constantly and the algorithm shows you things that are similar to what you’ve already seen, so I see lots of photographs that are similar to my own. But I’m looking for inspiration, not to reproduce what everybody else has already done. When I come back from a country and post my photographs on Instagram I’m not just showing everyone where I’ve been on my travels: I want to discover things that haven’t been seen before. My first big Instagram hit was in 2017 when I went to Paris and took a photo of the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe from above so you can see the roads fanning out from the round about. It’s the

most basic shot imaginable, but it took me from 10,000 followers to 40,000 in a few months. That was the first real wave of recognition.

Are there any other artists or photographers who’ve inspired you?

Not really, to be honest. It’s a bit like music: I have favorite singers and favorite songs, but I rarely want to listen to a whole album. There are photographers whose style I like or individual photos, but there’s nobody who makes me say I want to be like them.

Your photos look a lot like the work of MC Escher, with strong symmetry and recurring patterns. Was that an inspiration for you?

Actually I hadn’t heard of him until this year when I was in Calpé in Spain at La Muralla Roja, the housing estate by Ricardo Bofill that was the inspiration for the Netflix series Squid Game. I was reading the comments under a photo of the building and someone mentioned Escher, so I looked up his work and I can see there are a lot of similarities. I like to provoke the viewer and make them question what they’re looking at, so they take the time to study it in detail. Also, my photos are designed to be printed in large format. I want to trigger people’s curiosity when they see them from a distance so they’re drawn into the detail. Recurring patterns are a really good way of doing that.

Some of your photos are very minimalist and make your subjects look very small while others are full of detail. How do you strike the balance?

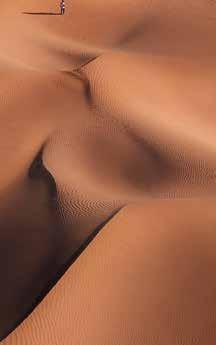

I see a lot of people on Instagram who focus on minimalist landscapes while others are interested in scenes that are packed with detail. I prefer the latter, but I like to have variety too. I don’t take minimalist pictures just to show someone standing in the middle of nowhere, but to contrast them with their surroundings, so people ask: what’s this person doing in this remote place? Or I crop out the horizon so the landscape seems endless. The photo on the

cover of the book, for example, shows an isolated house in the middle of the water. I deliberately didn’t raise the drone too high so the neighboring houses were kept out of shot, to create the impression of solitude.

When you take selfies you make yourself very small in the picture. Are you trying to subvert the idea of the selfie so it focuses on the landscape rather than the person’s face?

I’m not interested in taking portraits or showing facial expressions. The expression comes from the whole photo, so I don’t want the person’s face to distract from the story it’s telling. Often when there are people in my photographs they’re not just far away but looking away from the camera or walking towards the horizon, or absorbed in their thoughts. I want it to appear as if the scene is happening without the camera being there.

When you put yourself in the photos is it to express the solitude you mentioned earlier?

No: it’s because my mother complained that when I went on vacation I never photographed myself in these beautiful places! But it’s also practical. I travel alone sometimes because my friends mostly have steady jobs and they can’t come with me. So I have to do my own modelling. It makes it easier because I know where to put myself in the picture: I don’t need to shout at someone else to move left or right while I’m trying to position the drone. But sometimes I have to rely on someone else who’s passing by, like the photos of surfers in Hawaii, for example, because I can’t surf and pilot a drone at the same time.

What’s your favorite time of day to take photos?

Sunrise and sunset, because the light’s more interesting then. I can play with the shadows to bring out a small detail or illuminate one element, like a side of a building or a person in the light. Aesthetically I prefer a soft blue and a warm yellow, which are the colours you see at dawn and dusk.

You often combine natural and artificial light, such as in your photographs of cities at dusk or in the shade of a mountain. How do you make that work?

It’s more rewarding technically because even though drone technology has improved, it’s not just about the quality of the camera. The exposure on a photograph has to be exactly right, especially at sunset when the sun is behind the buildings and some objects are in the light while others are in the shade. I like the dance of the light on the houses and the city, the way it reinforces the contours. It’s an aesthetic choice.

How much editing do you do?

It depends on the photo, but generally I spend a minimum of 45 minutes to an hour per photo. I could go faster but I’m not interested in editing the photo as quickly as possible just so I can get it up on Instagram for six o’clock. Sometimes it’s good to come back to it a few hours later, or even the next day.

You started out photographing cities, but recently you’ve been concentrating more on nature. What made you change your focus?

I enjoy the noise and the bustle of cities like Shanghai, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Chicago. I’m passionate about visiting cities and they’re amazing places, but I don’t get much rest there. So I thought, why not try nature for a change? I went to Bali and Hawaii, and even though I didn’t take so many pictures and I got fewer responses, I enjoyed being in those places more. I had the same thing last year in Iceland: when I got back I didn’t have a huge number of photos and they weren’t in my usual style, but it was just lovely to be there.

How have you adapted your style for natural subjects?

When I only had a few photos that were predominantly green I felt like they didn’t fit my Instagram feed. It was driving me mad because I pay close attention to the colours in my feed, so I left them out at first. The positive aspect of going on a nature trip

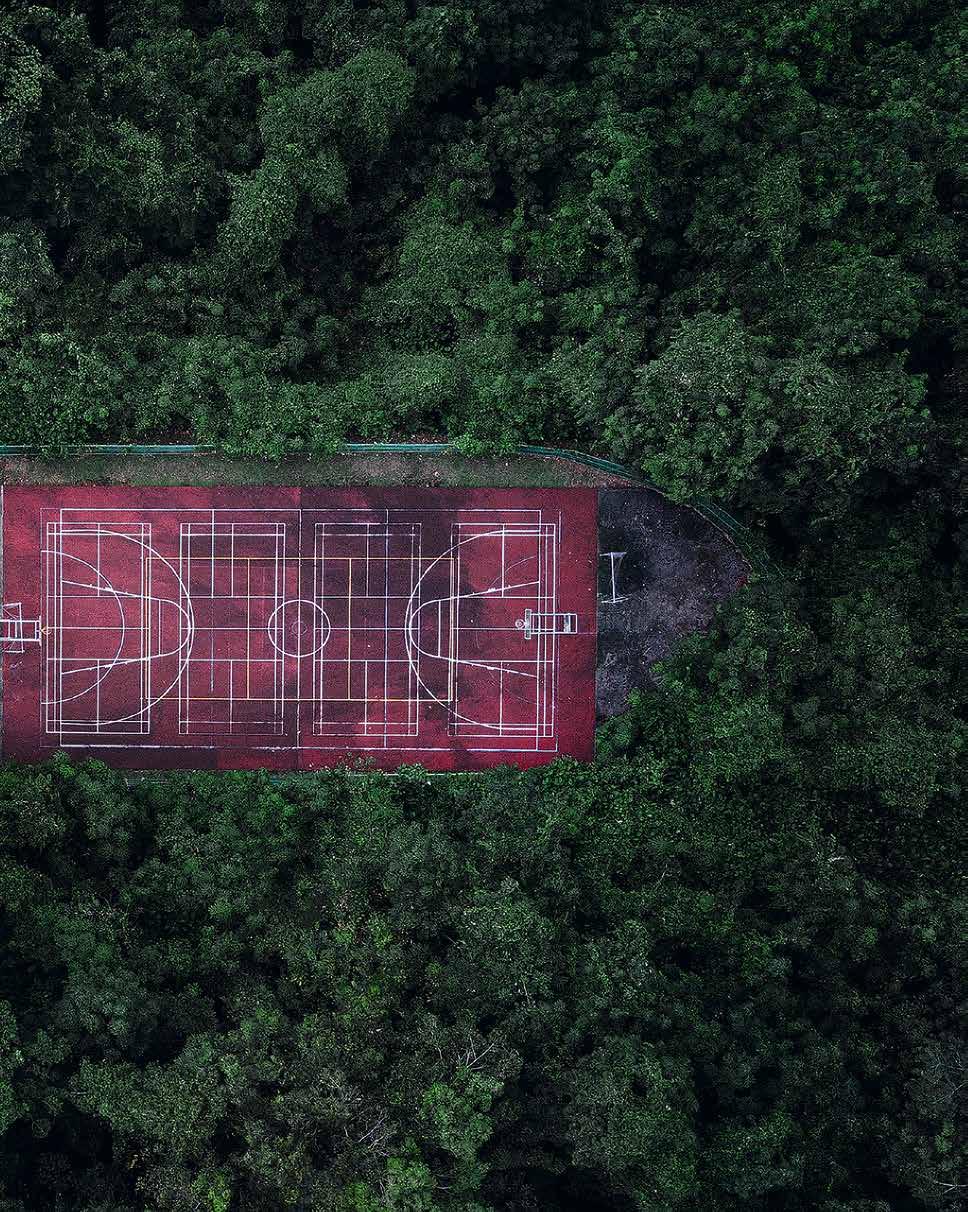

was that I could post a whole string of green photos, so that calmed my mood. I love taking photos of nature, but I like to find elements of architecture even in nature. That’s the basis of the book, in a way. I want to find things in nature that guide you along a route or interact with the light, like a path or a line of trees. I show the imprint of human beings on nature, but also the way nature continues to form our modern world. I’m always looking out for the points where they meet and the shapes that they create together.

Where do you want to go next?

It’s a long list! I’d love to go to the Philippines, because I have a friend whose in-laws live there. I get the impression it’s like Thailand in style but even more beautiful and better preserved. As for cities, I’d love to visit Rajasthan, but I don’t want to go there alone and not many people want to travel with me because of the poverty and the pollution. I don’t mind that: I’m not easily shocked, I want to see different places and experience how people live.

I’ve taken a lot of photos of cities that are very clean, but places like Spain and Italy, or even New York, are losing their novelty now that more people are buying drones. The problem with more distant places is it’s more difficult: I had a ticket to go to a beautiful little village in Algeria, but it’s dangerous there and drones are forbidden, so I need to think about how I do that.

What other ambitions do you have for the future?

Well, one of my biggest dreams was to publish a book, so I’ve achieved that! Maybe later there’ll be other books on particular subjects, or I might just keep publishing books based on my travels, because when I was selecting photos for this book it felt like a never-ending task. So perhaps I’ll visit some new places or try different styles, or just carry on with what I’m doing now.

Gordon Darroch

DESPITE THE ADVANCES of civilization and technology, nature is still the greatest influence on the man-made environment. The shapes and patterns in the natural world, the profile of mountains and the arcs of rivers all have their echoes in the cities we build. Trees are as essential to the urban landscape as houses. And increasingly, humans have made their mark on nature in fields, clifftop settlements and artificial islands. From the air we see how this interdependence shapes the world: the interplay between straight line and curve, brickwork and greenery, hillside and housing block.

“The great advantage of nature is that you can find it everywhere: not just in rural areas, but on the edge of cities or in forests all over Europe. It’s more accessible than the deserts or large expanses of water that you need a boat to get to. I like to find traces of humanity in nature: I look for castles in the forest in Austria or Germany, or little villages in the Dolomites, or a road that leads to a bridge. So many structures lead to or blend in with nature that I can very quickly find interesting things to photograph. And I can put the drone wherever I like, so the objects in the picture aren’t there by accident. What I like to do is frame the shot or position the drone to manipulate the viewer’s eye: even a group of trees or a mountainside, seen from a certain angle, can remind you of a city skyline. It’s what my style of photography is all about, showing people nature in the city, but also elements of the city in nature.”