dedication

This book is dedicated to the students who shared their stories with vulnerability and wisdom. In reflecting and sharing your story, you create the opportunity for connection, reminding us of our shared humanity and that people cannot be put in a box.

A special thanks to the Theodore and Maxine Murnick Family and Ron Gubitz, who believed in and helped shape my vision of leveraging visual storytelling to change the status quo. Without their support, these important narratives might have remained untold.

To all who engage with these reflections:

May these portraits continue to serve as mirrors, inviting us to turn inward and examine how we can broaden our perspectives and inspire conversations that will transform today's stories into tomorrow's history.

With deep gratitude, Julia Mattis

Foreword

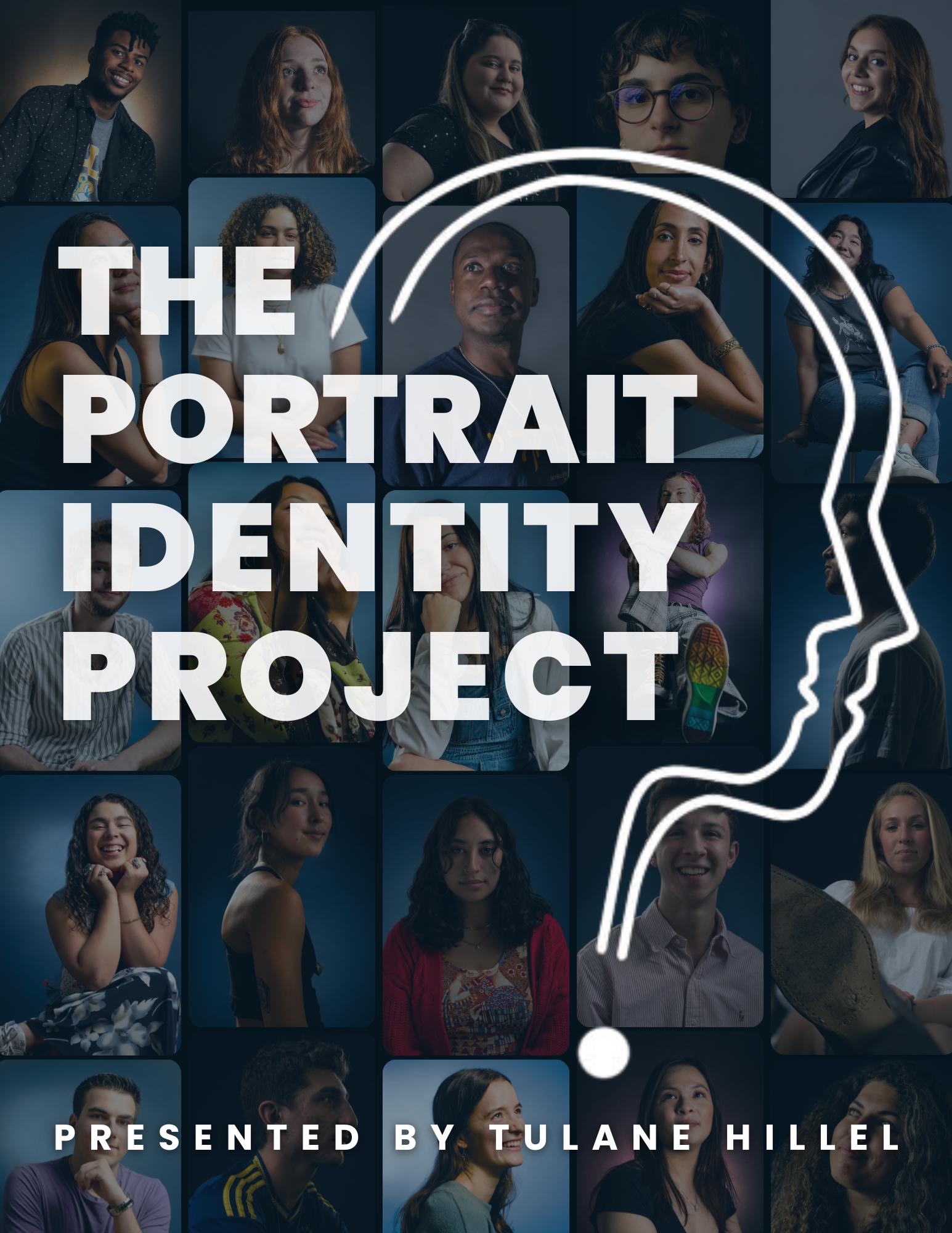

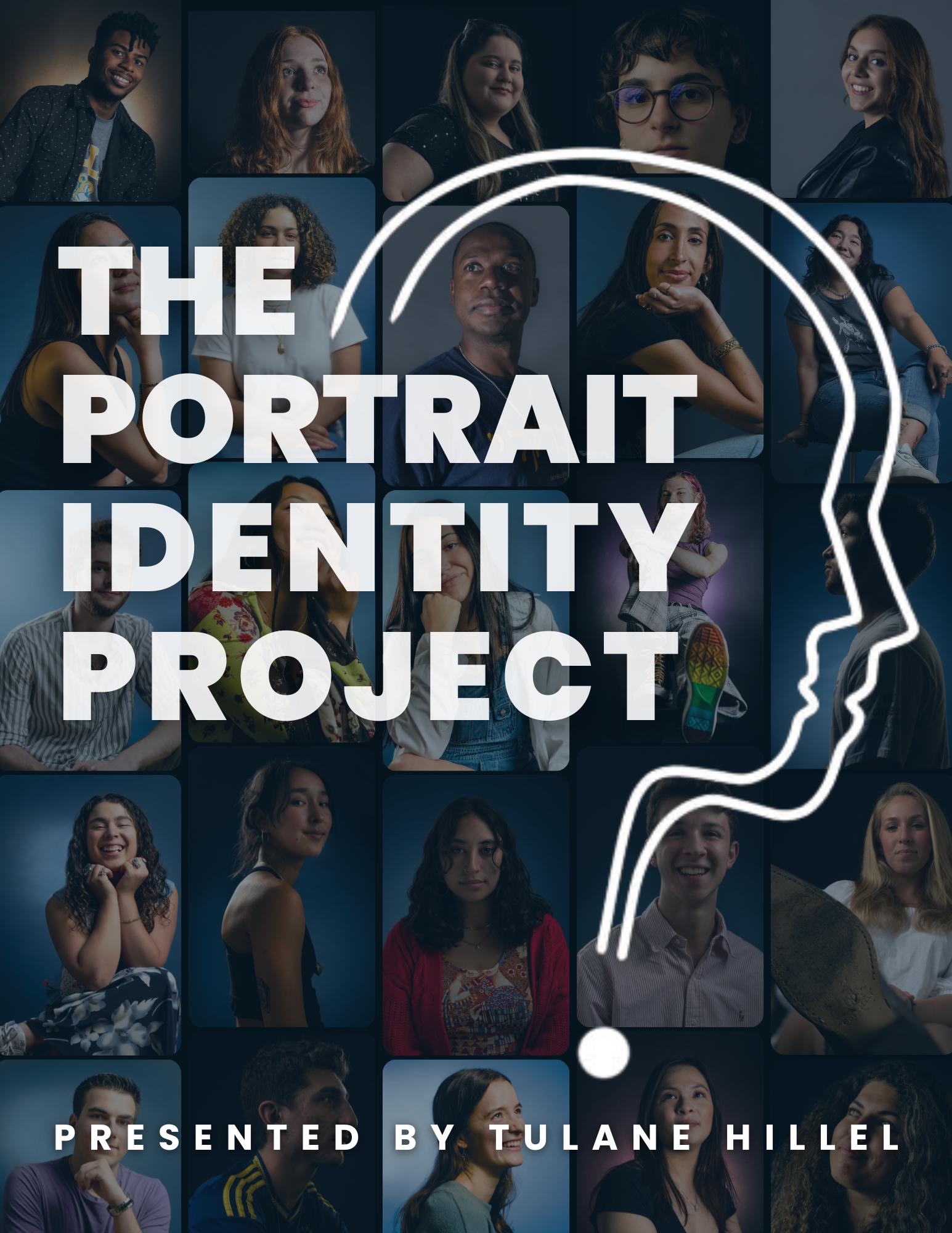

Launched in 2021, The Portrait Identity Project is a social documentary project that broadens the perception of what it "looks like" to be Jewish. Sharing stories paired with professional portraits, this initiative brings communities together to look, listen, and learn from students as they selfreflect on the intersection of their identities and how their perception of being Jewish has evolved. The Portrait Identity Project brings to light students' experiences of feeling as though they struggled to belong, inviting us to change the narrative by celebrating the many ways to be Jewish.

Participants in the project share their stories by reflecting on a series of interview questions about how Jewish identity intersects with other facets of identity, how one's environment impacts how Judaism is viewed and embraced, and how stereotypes affect how Jewish identity is conveyed or internalized. The interviews create the space for participants to process the full range of their experiences with Judaism, and the project amplifies the voices and experiences of underrepresented Jews.

As one looks, listens, and learns from these narratives, all audiences are encouraged to reflect on how their personal experiences have shaped their identity, reconsider past perceptions, and feel connected as they see themselves in others' stories.

About Tulane Hillel

Tulane Hillel is a nonprofit community center that fosters leadership and community engagement. Our mission is to create a radically inclusive community, develop students’ leadership, and encourage curiosity through our Jewish values.

Tulane Hillel is excited to broaden the scope and impact of the Portrait Identity Project by expanding this meaningful project nationally, ensuring more students and community members across the country can learn, grow, and share their stories.

If you would like to learn more about the Portrait Identity Project and how it would impact your campus and help your organization meet your goals, please get in touch with jmattis@tulane.edu.

For more information, visit tulanehillel.org or find us on Instagram @tuhillel

How to Digest:

As you read each story,

1. Click on each name.

This will open an audio file in Google Drive in a new tab.

2. Click play on the audio file.

3. Listen as each share their story in their voice.

Avi Becker

he/him

Growing up in St. Louis, I always knew I was Jewish, but understanding what that meant took years to untangle. My identity exists at the intersection of two very different Jewish experiences—my dad's side, rooted in American Jewish tradition going back generations, and my mom's side, shaped by the Soviet suppression of Judaism and immigration to America.

My identity exists at the intersection of two very different Jewish experiences…

My paternal family represents the established American Jewish experience. My grandparents were conservative Jews, and my dad definitely went to an Orthodox shul growing up. But this traditional approach didn't suit him. He felt that was very stifling. My mother's story is dramatically different. My mom's side is Soviet Ukrainian immigrants who arrived during the last immigration wave that the Soviet Union was allowing Jews to leave before it collapsed. Under Soviet rule, Judaism was essentially illegal, and religious practice was dangerous—my great-grandfather was almost caught baking matzah that was illegal. The family faced what the Soviets broadly categorized as "Jewish business" crimes. My mom had almost no Jewish heritage growing up because of this systematic suppression.

When my mother's family finally escaped, they spent time in Italy before choosing the United States over Israel, believing it offered more opportunities. During this transition, my mom received some amount of Jewish education but never had formative experiences like a Bat Mitzvah. She truly connected with Jewish tradition only when she met my dad and became close to that sort of family.

Avi Becker he/him

This dual heritage has shaped my own relationship with Judaism. My family is just kind of in this hybrid point where there's a strong Jewish identity that isn't necessarily fully American Jewish. There's also just a lot of mixture of the Soviet Jewish experience. As I've gotten older, my connection to Judaism has deepened. I started becoming more passionate about going to temple for the High Holidays, and I now attend services with my younger brothers, who have both had their bar mitzvahs. This growing involvement reflects something I've come to understand about Jewish identity: it's an experience that no one else will understand. And I think having that connection is incredibly important, because without it, I don't think I feel complete.

My Jewish identity isn't simple or easily categorized. It carries the weight of Soviet persecution alongside American Jewish tradition, immigration stories alongside generational roots. But perhaps that complexity is exactly what makes it authentic —a living bridge between two worlds that somehow creates something entirely my own.

My Jewish identity isn't simple or easily categorized. It carries the weight of Soviet persecution alongside American Jewish tradition, immigration stories alongside generational roots.

Dara Brownstein

she/her

Growing up, my Jewish identity emerged only on holidays, and the rest of the time, being Russian defined me.

I was born in the United States, but my family's immigrant story is deeply intertwined with their Jewish identity. My mom came when the Soviet Union collapsed, and a big part of that was they were persecuting Jewish people. I never truly understood what this meant until college: They sacrificed everything to come here just to be Jewish.

Before university, Judaism existed at the edges of my life. I never really had a rabbi or Jewish friends—instead, my world was filled with Italian Catholic or Albanian Catholic peers. I never went to Shabbat until arriving on campus.

I've always felt the need to choose to be Russian or Jewish. The environments I'm in seem to dictate which identity comes forward

However, I've become way more involved in the Jewish community since coming to college, exploring traditions and trying to understand Jewish morals more than I did at home. But this journey hasn't been without its complications. I've always felt the need to choose to be Russian or Jewish. The environments I'm in seem to dictate which identity comes forward. At school, I'm Jewish. I don't talk about being Russian, while at home, the reverse was true.

This division extends beyond my personal struggle. When I mention "my dad's from Russia, my mom's from Ukraine," it "always elicits a nasty response," though "everyone in my house is obviously pro-Ukraine. They left Russia for a reason.”

Dara Brownstein

she/her

What I've come to love most about exploring my Jewish identity is discovering that Judaism is so oriented toward giving back. This value resonates deeply with me and has inspired me to help plan the service trip and run for service chair. Service has become central to my identity—something I got from being Jewish.

My college experience carries unique weight, knowing my parents worked really hard to get me here. This awareness brings another layer of pride and a little guilt since "I get all these opportunities, and they never did.

Being Jewish in America now feels really weird. With current tensions, I feel I can't really openly be like, 'I'm Jewish.' There's hate towards Jewish people for no reason, often conflating individual identity with government actions.

As I continue navigating college life, I'm learning to embrace both sides of my heritage. The Russian culture that shaped my childhood and the Jewish traditions I'm now exploring aren't competing identities but complementary parts of who I am becoming. It's a journey of honoring my family's past while creating my own future and finding my place in a community that feels increasingly like home.

I've always felt the need to choose to be Russian or Jewish. The environments I'm in seem to dictate which identity comes forward

What parts of your identity have you felt pressured to hide or separate, and how might embracing their coexistence offer a more authentic version of yourself?

sHe/her

In middle school and early high school, I noticed I was raised a little bit differently than my peers. I was born in America. I grew up here. I speak English primarily. Every morning, at school, I’d recite the Pledge of Allegiance. But the moment I walked through my front door, everything shifted. I switched languages. The smells were different. The holidays were louder, more colorful. Even my Jewish friends didn't celebrate like we did—they didn't have a sukkah in the backyard.

I remember going to my friend's parents' house and taking it all in. They didn't have accents. They spoke perfect English. They'd been in the same town for three generations. They had a little white dog that yapped a lot. And I thought: I clearly don't belong here. I'm an outside person. Then I'd go to Israel in the summers, and I was the cool American cousin. Not Israeli—which made sense, because I wasn't. I grew up here. For a while, I felt suspended between two identities, like I was supposed to choose one.

I realized: Wait, I don't have to pick one. I can be both. And I think that's really cool.

Then something clicked. I realized: Wait, I don't have to pick one. I can be both. And I think that's really cool.

College gave me the space to figure out what I wanted my Judaism to look like. And what I discovered surprised me: my Judaism means a lot more to me now. In high school, you just do what your parents do. But with the independence to make my own choices, I've been able to form what I want my Judaism to look like. I joined the Shabbat hosting lab because Shabbat was really interesting to me. I decided I wanted to be a little bit more religious than my parents, to focus more on kashrut. I've added two Magen David to my necklaces since last year—being outward about my Judaism, showing that pride.

sHe/her

Take Shabbat. At my parents' house, it was just lighting candles and eating dinner. Now I like doing kiddush and baking challah when I'm able to. I've started occasionally not using my phone on Friday nights. It's about the kavanah, the intention. But what really shaped how I embrace my Jewish identity was realizing I wanted to share it with others. Throughout my whole life, I've always included nonJewish people in my Jewish activities. I invited my very Christian friend to Passover during my junior year. When I hosted Shabbat in college, ten people came, asked questions, and having the ability to answer them—that's what was really important.

My Jewish identity almost affects the other parts of myself more than any other part. It's not just being religious—it's the culture, the actions you take. It's something that is so special and so unique that you really need to be proud of it. No matter what's going on in the world, no matter if antisemitism is up 300%, it's always going to be a part of you. We all sing the same songs. We all sing the same prayers. At the end of the day, you're one in 15 million. That's not a lot.

At the end of the day, you're one in 15 million. That's not a lot. .

What does it mean to be visibly Jewish in a world where antisemitism is rising, and how does sharing your traditions shape your sense of pride?

Josie Leit

she/her

In college, I became more observant in my Judaism. This wasn't something I anticipated. Growing up, Judaism was part of my background, part of my family's rhythm, but I didn't actively think about the brachot throughout the day or what it meant to truly observe Shabbat. But here, with the freedom to choose my own practices, I've completely started new practices. Last year, I was shomer Shabbat for a couple of months. Now, on Friday nights, I go and observe Shabbat, leaving my phone at home and trying to be very present. I make sure to light the candles every Friday night, do hamotzi over the challah, and recite the different brachot that have become more important to me. It's not that I morphed or changed what I did before– I created something that feels mine authentically.

It's not that I morphed or changed what I did before—I created something that feels authentically mine.

My Jewish identity is also deeply rooted in culture. My dad is an Ashkenazi Jew from Brooklyn, and I carry that heritage with me—having sauerkraut, eating bagels and brisket, even the stomach issues that come with it all. These cultural touchstones ground me, remind me of where I come from, and connect me to generations of Jewish life in America.

What's fascinating is how Judaism has shaped me as a student and thinker. Education has always been one of the main pillars of Judaism—to learn, to investigate, to debate. That principle has guided me in my studies and in wanting to be a leader. As the saying goes, two Jews, three opinions. We've always had discourse, and I think that's definitely made me more of a listener, but also more of a debater.

Josie Leit

she/her

Yet my experience as a Jewish woman hasn't been without its challenges, particularly around how others perceive me. People have stereotyped me and been shocked when they discover I'm Jewish, as if I don't fit their assumptions about what Jewish people look like. When I was younger, I had pin-straight blonde hair, and I remember a friend asking me, "How are you Jewish? You don't have a big nose?" I was stunned. It was frustrating to realize that people believed these stereotypes, that they thought certain features made someone more or less Jewish.

Through it all, I've learned that my Judaism isn't about meeting anyone else's expectations or fitting into predetermined categories. It's about the choices I make, the traditions I uphold, the community I build, and the values I carry forward. Coming to college gave me the space to grow as a Jewish woman on my own terms, and that growth continues every Friday night when I light the candles, every time I speak up for what matters, every time I choose to be present and intentional in my practice. This is my Judaism, and it's become more meaningful than I ever imagined it could be.

Two Jews, three opinions. We've always had discourse, and I think that's definitely made me more of a listener, but also more of a debater.

Coming to college gave me the space to grow as a Jewish woman on my own terms, and that growth continues every Friday night when I light the candles, every time I speak up for what matters, every time I choose to be present and intentional in my practice.

Amarya Levy-Mazie

she/hers

Iused to think the whole world was Jewish. Growing up in Brooklyn, I had no idea that less than 1% of the world's population was, because in my head, my community was 100% Jewish, and that's what I thought of the world as being.

The stakes of this bubble didn't reveal themselves until I left it. As a child, I felt perfectly secure—almost everyone around me shared the same holidays and cultural understanding. I remember finding out that one of my friends wasn't Jewish, and I was so surprised.

My parents' decision to send me to Jewish camp felt ordinary then, but it created a trajectory I could have never anticipated. Looking back, I am amazed by how significantly camp has shaped my life. If not for camp, I definitely wouldn't have gone on a gap year, and who knows if I’d even be at Tulane!

I met Jews who had grown up as minorities in their own communities, who had fought to maintain traditions I had taken for granted, who had chosen Judaism actively rather than absorbing it passively the way I had.

The transformation began when I left Brooklyn for a gap year in Israel through Young Judaea. This became my bridge between worlds. There, I met Jews who had grown up as minorities, who had fought to maintain traditions I had taken for granted, who had chosen Judaism actively rather than absorbing it passively. I began to see how my Brooklyn upbringing had been both a gift and a limitation to understanding the reality of living as a Jew in many parts of America.

Coming to Tulane, I wasn't the girl who was surprised to meet non-Jews anymore, but I also wasn't willing to let my Jewish identity fade. Instead, I became a bridge-builder, helping others understand traditions while articulating why they mattered to me.

Amarya Levy-Mazie

she/hers

Coming to Tulane, I wasn't the girl who was surprised to meet non-Jews anymore, but I also wasn't willing to let my Jewish identity fade. Instead, I became a bridge-builder, helping others understand traditions while articulating why they mattered to me.

My Brooklyn bubble hadn't been a limitation—it had been preparation. Growing up surrounded by Jews gave me a foundation strong enough to maintain my identity even after the bubble burst. The community my parents built became the blueprint for every Jewish space I would create afterward.

Now I see my Jewish identity as both inherited and chosen. I inherited the comfort of belonging, but I chose to carry those gifts with me, to share them with new communities, and to build bridges between the Jewish universe of my childhood and the wider world I navigate now.

My Brooklyn bubble hadn't been a limitation at all—it had been preparation. Growing up surrounded by Jews gave me a foundation strong enough to maintain my identity even after the bubble burst.

How does growing up immersed in your cultural or religious identity prepare you differently for the wider world than growing up as a minority within it—and what do you gain or lose in each experience?

Dawn Siegall

she/her

Ididn't grow up Jewish. Coming into college with a Christian mom and a Jewish dad, I felt like I didn't really know much about either religion. Judaism felt like something that belonged to others—to my father, to his family—but not quite to me. It was only when I started college that I began actively seeking answers about my religious heritage, declaring a religious studies minor because I wanted to learn more.

Two pivotal moments shifted my relationship with Judaism. First, my father became more religious after marrying my stepmom, who used to be Orthodox. Whenever I went home, they would teach me a little more about Judaism. This coincided with taking a Jewish Studies class at Tulane.

But it was my trip to Israel through Birthright and the Onward program that truly transformed my connection. That summer in Israel was when I really learned about the religion and the culture, experiencing Judaism firsthand and the community that it builds. For me, Judaism became about its community aspect, about the family- and community-oriented lifestyle it fosters.

While they viewed the trip as a rite of passage, I was there seeking something I hadn't grown up with.

Yet my journey hasn't been without doubts. During that summer in Israel, I was constantly aware of not knowing enough. While others shared stories of their Jewish upbringing, I found out that literally everyone was from a very Jewish community, and I was pretty much the only one who came in to learn more. While they viewed the trip as a rite of passage, I was there seeking something I hadn't grown up with.

Dawn Siegall

she/her

Even more complex has been navigating the intersection of my multiple identities. Being Asian American and having both Jewish and Christian influences has meant constantly straddling different worlds. In my Asian family, I'm the white girl, and then in my white family, I'm the Asian girl. Even within my father's family, there's the non-Jewish side, which is where my dad's lineage is, and then the very Jewish side. But I've learned from that experience that it's important to get along with different types of people, and I'm grateful for that. Now I feel like I can connect with almost anyone because I had to while growing up. Being exposed to such diverse people has made me enjoy getting to know different types of people. I think that's why I'm always eager to learn about various cultures and religions. I'm intrigued because I've seen firsthand how Christian families function through my mom, compared to my Jewish upbringing and traditions.

Physical appearance has added another layer to my experience. A lot of people are surprised that I'm Jewish, likely because I'm Asian, and there are not that many Asian American Jewish people. Even in Israel, my appearance elicited reactions of surprise. This reality has sometimes made me hesitant to claim my Jewish identity outright.

Today, I'm more comfortable saying "I'm Jewish" now, even if I follow it with acknowledgment that I'm still learning. Being Jewish for me is about finding connection, community, and a sense of belonging that grows stronger with each step I take.

In my Asian family, I'm the white girl, and then in my white family, I'm the Asian girl. Even within my father's family, there's the nonJewish side, which is where my dad's lineage is, and then the very Jewish side.

Aidian stein

he/his

In North Carolina, being maybe one of 15 to 20 Jewish people at a high school of 4000 meant constant explanations. When people asked what church I attended, I'd say, "Oh, I go to Temple Beth-El," watching their confusion unfold.

My family has always been a melting pot.

My family has always been a melting pot. I have branches of my family living in Israel and South Africa, and other branches living on farms, and I love both equally. I'd spend weekends in the Appalachian Mountains with rural relatives, then connect with Jewish family scattered across metropolis cities worldwide. There are just some weird cultural mixes with that sometimes, but they're both in my blood.

The South shaped my Jewish experience differently from how it did my friends from the Northeast. There are very different dynamics growing up in the South —less pressure for the full duration of Hebrew school, fewer massive Bar and Bat Mitzvah celebrations.

Everything shifted when I arrived at college. Moving from my tiny Jewish community to a college that's almost half Jewish was transformative. Suddenly, there was an active discussion with friends about our Judaism, rather than isolation. I just feel like my day-to-day Jewish life pleases that side of me every single day. I don't have a single day go by here where there isn't something Jewish.

Aidian stein

he/his

But it was October 7th that changed everything. I lost two friends, Noam Shallom and Bar Tomer, at the Nova Festival attack. The grief was devastating, but it also compelled me to dive deeper into Jewish life—to allow myself a space to mourn with other people who were doing the same. I realized I was at the most Jewish university in the country and could literally go outside and find someone to discuss this with. Finding peace within the Jewish community after October 7th, getting support after losing Noam and Bar, became essential to my healing. That tragedy and my own personal grief allowed me to pursue even more of a Jewish life here and have even more pride in it.

Looking ahead, the first time my Appalachian relatives and Jewish community will mix will probably be my wedding day. I'm excited for that integration, knowing that my whole life has been about appreciating the weird dynamic I've got going on—Southern roots intertwined with Jewish branches, creating something beautifully complex and entirely.

That tragedy and my own personal grief allowed me to pursue even more of a Jewish life here and have even more pride in it.

How can moments of profound loss become catalysts for deeper connection to community and identity?

Abigail stevenson

she/her

Ithink the only people I knew growing up in Kentucky who were Jewish were my neighbors, and they were in their 80s. My family is removed from religion of any sort, but I have Jewish family members on both sides, which made exploring my Jewish identity feel both natural and necessary. While everyone around me was going to Young Life or Wednesday Bible studies, I found myself spending countless hours alone in my room reading Jewish books. I became attached to the religion through solitary study and personal connection. In many ways, I was the sole representative in a community that had never met even a vaguely Jewish person.

When I arrived at Tulane, I was excited about the prospect of finally finding my people. The strong Jewish population was one of the reasons I wanted to come here so badly. But my entire freshman year, I was too self-conscious to visit Jewish spaces. I would walk past Hillel, knowing I belonged there in some way, but feeling like "I never felt that Jewish" compared to my peers whose families were way more observant than mine. In Jewish spaces, I felt more like an audience member rather than a full participant, constantly questioning whether I belonged.

In Jewish spaces, I felt more like an audience member rather than a full participant, constantly questioning whether I belonged.

This insecurity led me to begin the conversion process—initially, not for the right reasons. At first, I decided to convert because I really wanted to prove myself to others. Since my mom isn't Jewish, I felt I needed that formal recognition to call myself Jewish comfortably. But through conversations with friends and taking classes at Shir Hadash, my motivation shifted. It became more of a thing where it's like, this is something I want to do for myself, not just for recognition.

Abigail stevenson

she/her

The conversion classes opened my eyes to a different dimension of Judaism. Being alongside other people with similar experiences—those whose extended families are Jewish but they're not, or those marrying into Jewish families—helped me realize I wasn't alone in my complicated relationship with Jewish identity. Since coming to Tulane, I have come to appreciate the cultural component I had never really been exposed to before.

But as I've grown more comfortable in Jewish spaces, I've simultaneously experienced something unexpected and painful in other areas of my life. Being a Jewish adult in America varies so much by situation and environment and by individual, and nowhere is this more evident than in my involvement with campus organizations.

I am very involved on campus and in a lot of student orgs, but over the past two years, I've noticed there's a very strong divide on campus, with some people who don't care at all about Jewish identity or Zionism, but many others who are strongly aligned against Israel and without even talking to me about it, they politicize my identity. Friends have pulled people aside, pointing out when I've liked an Instagram post from Jewish on Campus or when I'm featured in a Hillel post, as if my mere existence as a Jewish person is inherently political.

I'm learning that being a Jewish adult in America means existing in this complexity, but I'm no longer seeking validation from others. My conversion process has taught me that Jewish identity isn't about proving myself to anyone—it's about finding home in a tradition that has always felt right to me, even when I was reading alone in Kentucky, and it feels like community.

My conversion process has taught me that Jewish identity isn't about proving myself to anyone—it's about finding home in a tradition that has always felt right to me, even when I was reading alone in Kentucky.

Friends have pulled people aside, pointing out when I've liked an Instagram post from Jewish on Campus or when I'm in a Hillel post, as if my mere existence as a Jewish person is inherently political.

Ohad tessler

he/him

Igrew up modern Orthodox, attending a private day school for 10 of my 12 school years. Judaism wasn't just a part of my life—it was the framework for everything. I went to shul weekly and davened daily, entirely immersed in the rhythm of Jewish life.

At 16, I decided to transfer to a public school. This decision wasn't just about education—it was my first step toward defining my own Jewish identity outside the structured environment that had shaped my childhood.

This decision wasn't just about education—it was my first step toward defining my own Jewish identity outside the structured environment that had shaped my childhood.

When I arrived at Tulane, I connected with Chabad and Hillel, but stopped many practices that once defined my days. No more keeping Shabbat. No more daily prayers. Something was missing, but I knew I would return to Judaism while I focused on building other aspects of my life.

When Oct. 7th happened, I was living in Israel. The Hamas attack forced me to leave Israel, but returning to Tulane revealed something unexpected—our campus had united in the aftermath of October 7th. This solidarity inspired me to resume my religious journey. Since then, Judaism has once again become a core value. As of last Rosh Hashanah, I've tried to wear my kippah as consistently as possible, which is the most significant step I've taken.

This visible symbol has transformed how I embrace my identity. I wear it with pride—at that point, you don't even need to ask if I'm Jewish. It's powerful to see so many others doing the same at Tulane. I don't know how many other campuses have this level of open Jewish expression.

Ohad tessler

he/him

Community makes everything possible. There's no way I could observe Shabbat without others doing it alongside me. You'd be bored all day if you're the only one not using your phone, without others to meet at the same place and time. Instead, we meet at Chabad for shul on Saturday mornings and hang out until Shabbat ends. This belonging has deepened my practice immeasurably.

There's no way I could observe Shabbat without others doing it alongside me.

Now I'm working to grow our religious community. The religious community is often left out when people talk about Jewish life at Tulane. I want to show that you don't need to keep Shabbat to be part of this community. As graduation approaches, I face new questions. My finance career will require 60-70 hours per week, potentially overlapping with Shabbat. While I know Saturdays are safe, I wonder about holidays. Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are nonnegotiable, but what about Sukkot and other observances?

Practical concerns emerge, too: How kosher should I keep? At Tulane, I have Hillel and can prepare my food, but will that be sustainable when I'm working? Are there enough kosher options near my workplace? And will I continue wearing my kippah as I build my professional identity?

How do you balance maintaining religious practices that require community support when entering environments—like demanding careers— that may not accommodate or understand those needs?

Daniel Wiesen

he/him

In Carbondale, Illinois, I was one of just five Jewish kids my age in our entire town. Our small congregation, Beth Jacob, had about 100 members on paper, but any given service saw maybe 20 people. Judaism existed at the periphery of my childhood—something I acknowledged but rarely explored deeply. My dad, a scholar of German history, attempted to run a Sunday school, but without expertise in teaching children about Judaism, these efforts faded. I essentially assimilated into my non-Jewish environment, aware of my difference but not fully embracing what it meant.

Judaism existed at the periphery of my childhood—something I acknowledged but rarely explored deeply.

Coming to Tulane University transformed my relationship with Judaism. Suddenly surrounded by a significant Jewish population, I experienced what many students find in reverse—while others leave self-affirming environments and face challenges in college, I discovered a community that reflected parts of myself I had barely acknowledged. I've had to evaluate the importance of Judaism in my life because its relevance has increased rather than decreased. For the first time, I began thinking critically about what it means to me to be Jewish in today's world.

I don't have definitive answers because it's still evolving for me. I believe Jewish identity for people of my generation exists in a confusing moment. We're witnessing significant shifts between how young Jews and older generations view the future of American Judaism. The Holocaust, once omnipresent in Jewish identity, is gradually becoming more historically distant. Meanwhile, contemporary issues like the war in Gaza feel more immediate, creating tensions within Jewish communities.

Daniel Wiesen

he/him

This has led me to focus on the social, cultural, and political dimensions of Judaism rather than religious practice. I'm drawn to understanding Jews' place in the world, both historically as a persecuted minority and in contemporary contexts where Israel's actions raise difficult questions. One of my greatest challenges has been reconciling what feels like competing aspects of my identity. I understand Jews' position as what some call "the invisible race"—a group that has faced persecution throughout history. Simultaneously, I hold views critical of Israeli policies, particularly regarding Palestinian dispossession in the West Bank. It's like a catch-22—it feels easier to commit fully to one perspective, as public discourse pushes people toward extremes while cutting out the middle ground. The nuances get lost quickly.

This struggle to maintain nuance is reflected in my campus experience. At Tulane, I've observed how homogeneous Jewish student life can be, creating an echo chamber that fails to reflect the diversity of opinions in the wider world. The university bubble fosters certain perspectives while others remain unheard. Step outside this protected space, and suddenly you encounter viewpoints that Tulane students might consider extreme but are quite common elsewhere. This disconnect makes bridging divides feel nearly impossible.

Despite these complexities, I maintain cautious optimism. Education and genuine dialogue can create spaces where people can voice concerns without fear of judgment. Moving forward requires acknowledging painful truths on all sides while refusing to let historical trauma dictate future actions. By embracing the discomfort of nuance rather than retreating to simplistic absolutes, we might find ways to honor both Jewish and Palestinian dignity.

The journey of understanding what my Judaism means to me is far from over —it's a path I'll continue walking long after graduation.

By embracing the discomfort of nuance rather than retreating to simplistic absolutes, we might find ways to honor both Jewish and Palestinian dignity.

A Note from the Photographer and Creator

After hundreds of conversations and hours spent listening to students’ stories, it became clear that the limiting lens through which Jewish narratives have been and continue to be told was a problem that left many students feeling like they struggled to belong.

As an artist and a photographer, I had to do something with this realization. I began using portraiture photography, reflective interviews, and storytelling to change the narrative, foster connection, and instigate reflection on intersectional identities.

Two years and about 90 interviews spanning students from Tulane to Cal Berkley to Ithaca College later, I’m in awe of students’ vulnerability and ability to reflect on how their experiences have shaped their identity.

By sharing their stories, students uplift us all, reminding us of the complexity of the human experience.

I hope the impact of this project extends beyond this book and encourages all to engage with and listen to people’s stories, for what we’re doing with the Portrait Identity Project is telling stories of contemporary that will become history.

It’s also important to note that while this project serves as a platform to share, discover, and document individual stories, it’s limited to the people I had the privilege to interview and photograph. This body of work is ongoing and by no means a complete representation of all people who embrace “Jewish” as a part of their identity.

– Julia Mattis