PAULO LAPORT

PAULO LAPORT

Essay by Charles A. Riley II, PhD

PAULO LAPORT On the Edge

Barnardo:

Horatio:

--Hamlet, Act I, Scene i “

‘Tis here!

‘Tis here!

[Exit Ghost.]

Marcellus: ‘Tis gone! We do it wrong, being so majestical, To offer it the show of violence, For it is as the air, invulnerable, And our vain blows malicious mockery.”

Words

and paint are often at war. If ever there was an artist who defies ekphrasis or theoretical analysis it would be the arch-painter, Paulo Laport, the painter of paint. He has thrown “intellectuals” out of the studio for taking the wrong end of the brush (“You have to have the courage to talk about the paint itself”) and forgetting the primacy of the medium. “No tales, no external stories to articulate the exercise of painting,” he sternly admonishes the writer. This liberty is offered to the virtuoso—we must not ask too precisely how the feat is accomplished. Whether in music, dance, or other arts the moment of the dazzling technical performance, the object of awe, often signifies a compositional breakthrough of considerable risk and originality. In a recent book on aesthetics, AllThings Shining , that extols the way in which genius emerges in “shining moments” that have a Nietzschean transcendence, the authors Herbert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly progress from Homer’s Odyssey to Nureyev’s impossible leaps and on to sports (human highlight reels such as Pele or Michael Jordan come to mind) to convey the level of ecstasy through performance that elicits wonder: “The great athlete in the midst of the play rises up and shines—all attention is drawn to him. And everyone around him—the players on the field, the coaches on the sidelines, the fans in the stadium, the announcers in the booth—everyone understands who they are and what they are to do immediately in relation to the sacred event that is occurring.” There is a luminous virtuosity, a shining both literal and affective, in Laport that defies complete accounting even as it elicits our wonder.

When the virtuoso swings into action, often the material with which he or she begins can be relatively modest, like the air upon which Bach would build the superstructure of variations (the Goldberg edifice is the most obvious example). Laport’s Cartesian grid and restricted palette are a case in point. He has

reinvented the grid to serve the paint in its viscous state. Its systolic and diastolic pulse is all the more dynamic for the gentle modulation of the never-straight edges (Robert Ryman whispers in this way). Many of the vertical paintings use broader middle horizontal bands and diminishing top and bottom ones to bend the space of the painting (either convexly or concavely depending on your eye), a volumetric effect enhanced by the curved edges of LEKSO, which meet the frame in a tray configuration that is all the more absorbing perceptually, accentuating the hemispheric cloud of white on its left side. The rhythms of the grid, the most regulated part of which is generally the super-controlled vertical bands (twenty-five in all in DELFO, strategically oddnumbered as a nod to symmetry), are defined by edges, not lines. The titles, incidentally, are in capitals because they are derived from navigational aids, vectors in effect, offered to pilots as nodal points on a flight plan. Laport, who is trained as a pilot, says, “I really don’t know how to name things, but ZENIT for instance is a nickname for a crossing point between two routes coupled with a number, and a control tower will tell you to proceed to that coordinate, spelled out precisely, and descend 2,000 feet, for example.” As unrelated as possible to any verbal clue or suggestion of content, they strategically leave the viewer hanging in the air.

The artist emphatically does not draw, or offer himself or us any kind of armature below the improvisatory unfolding of the layers upon layers of paint. The echoes of the geometry have the power of the incantatory infinitives resounding in the most famous soliloquy in theater history, as murmured by Laurence Olivier perilously recumbent on a rampart high above the crashing surf. The pedal point rolls in an hypnotic barcarolle—“to die, to sleep…to die, to sleep, to sleep, perchance to dream,” transmuting hesitation into the highest order of poetry as only a Shakespeare, Proust or Mallarmé could accomplish. Another analogy is offered by the rippling arpeggios of Philip Glass (Laport adores his music), which like the ostinato of good Vivaldi, redirect the listener from a consciousness of the melody or harmony to the individual quality of the tone itself, an effect that can be tried by playing a simple Glass piece on the piano. It takes little or no effort

to recognize the truth of Glass’s own stricture that “all the notes are equal.” Laport, who reveals under duress that he is a drummer in a jazz combo (the construction of rhythm is his role) has this to say about his love of music: “I listen to the sound of the music, not the music. Same thing happens in the painting. I’m not dealing with an image or a method. It is a state of mind to perceive noise.” A similarly loving precision is lavished on the paint, which is why the touch is so admirable—those curls of impasto worthy of Hofmann, those palimpsests—and Laport offers a fleeting glimpse into the “how” of the studio practice:

What gives the sense of scale is the paddle and the brush.I cut and design my own tools.A movement that doesn’t have a strong track or mixes or glazes too much will ruin it. It is not choreographed.I prefer to establish an austere approach.

Sometimes I have to take out of the brush the excess of sensualitysoasnottodisturbwhatisgoingon.Theworkyou see that is made by the relief and tonalities. If I could do it withoutthephysicalmeansIwould.Icalibratethepaintingso that both touch and vision work together.It is not geometric. I am just following the edges of the colors.I cross one coat overanother. IstartwithasensationthatIcannotpredict or control, and then I follow this almost lurid image toward something concrete.All the brush strokes finish as the first start. Left to right, right to left, all the strokes are the same. (Interview with the artist, April 23, 2013).

The structural wonder of major poems, musical compositions and paintings like Laport’s is the way in which they open and close many times before they end, by necessity at a “terminal” edge which Laport (like Barnett Newman before him) reluctantly renders contingent. The works on paper leave the studio under glass, a la Francis Bacon who similarly relished the distancing effect of the in vitro captivity within which light paces back and forth reflectively. Laport unforgettably applied bleach to a sheet of handmade paper because it bore too much trace of the original cedar, its deep-hued burgundy and lavendar, even under layers of paint, were like the whiff of cedar’s equally insistent aroma. The finest expert on Laport’s works is art historian Guilherme Bueno, director of the

Museum of Contemporary Art and professor of Brazilian Art History at the School of Visual Arts in Rio de Janeiro. He comments:

“In Paulo’s works everything is contained precisely to ‘calibrate’ the presence of the painting: the trajectory of the brush and of the paint on the canvas cannot be called gestural or austere; it is not neutral, rather it is anti-expressive. The resulting mesh is not designed, but to call it spontaneous would be to commit the negligence of looking for, outside the geometry, an inconvenient emotiveness in it. That same mesh actually reinforces the self-unfolding relationship between the painting and the space that it simultaneously occupies and founds. This slow painting, in which respect is contradictory to the fast-moving modern world, requests of us a perception that I would not call introspective (which would make it sound romantic), but rather immersive (i.e., it requires accurate attention under prolonged exposition).”

One of the most original and eccentric aesthetic manifestoes of our time is the tectonic theory offered (and quickly forgotten) nearly two decades ago by the eminent historian of Modernist architecture, Kenneth Frampton, to whom the greatest building was the result of a constructive process that weaves vertical and horizontal, whether in the joinery of wood, the interlocking of brick, or the framing of glass by steel. Like Laport, forwhom paintings are things not signs, for Frampton a building is the work of the arche-tekton (where tekton offers an etymological link to carpentry and construction as well as poetry and weaving) that he brilliantly links not only to painting but to textiles and even literary texts. One superb example he offers (among signature buildings of Louis Kahn, Renzo Piano, Mies and others) is Frank Lloyd Wright’s La Miniatura, a brick and glass house he created for Alice Millard in Pasadena in 1923 when he had nicknamed himself “The Weaver.” It would be the ideal space in which to hang these tectonic paintings. Early in the manifesto, Frampton offers this perception that we can directly relate to the constructed space of Laport’s painting: “Everything turns as much on exactly how something is realized as on an overt manifestation of its form. The presencing of a work is

inseparable from the manner of its foundation in the ground and the ascendancy of its structure through the interplay of support, span, seam, and joint—the rhythm of its revetment and the modulation of its fenestration.” Even as an insight into the transition in Laport’s painting from one support to the other, canvas to oil, and the ways in which that influences what is built, moment by moment, upon it, Frampton’s idea has immense validity as a rubric for looking at art. If Laport’s paintings occasionally suggest the shimmer of elegant Beaux Arts façades (New Yorkers will be forgiven for thinking of the delicate play of light on the Flatiron Building in the raking light of morning), then the vocabulary of architecture might be invoked to account, for instance, for the marvelous a literal arched shadows under the hooded crowns of the architrave surrounding Laport’s windows. Inside them, glassy auroras, veined (horizontally in ORANS and ZENIT, vertically in LEKSO and DELFO) like metamorphic marble (speaking of tectonic formations) in the palette of mocha and a range of greys and whites worthy of Twombly, and, like him, conducting the light of Turner. Inside these cells float lilacs and burgundies that are shockingly vibrant in a work that reads from a distance as silvered.

Move a step, dim or raise the lights, and the dance of iridescence is initiated—pearlescent, opalescent, flickering through a spectrum that shifts in and out of the high Cubist palette of tans and greys. Great moments in realism have invoked the optical amazement of iridescence—Jan van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelite Lawrence Alma-Tadema dazzled viewers with marmoreal architectural settings while one of the miracles of illusionism remains one of the tiniest passages in paint, the nacreous earring itself, the most celebrated piece of jewelry in art, that is the focus of Vermeer’s portrait of an unknown girl. Laport eschews the representational, but the optical effect (not the thing itself, as Mallarmé would insist, but its effect) is irresistible and even a little shocking. Consider the artist’s own view, offered during a recent studio interview, which idiosyncratically but firmly adheres to the physical process. Note the violent ending:

The paint remains almost raw on paper or linen, less romantically it slants away from any possibility of illusionism.

My paintings are not allusions to things external to them. On the contrary, they keep literally within what presents itself.Butthemoreausteretheyareinartifice,theybecome more comprehensive to me.That’s the issue. Paddling and brushing the paint drags and leaves their inscription while adding more

paint.The modulation does not exist because the sense of calibrationgivenbythepaddleandthe brush, the width and pressure, are done to pull out the undercoat in the coat being applied over it.That’s why you see both dimensions at the same time.The difficulty of doing means no falsifying ease,and imperfections have to be perfect.It should create a visual collision.Normally you approach to see small things. And when you do,you are hit by a train.

The flight of the virtuoso, like the tenor at the top of his range where cracking is always a possibility or the surgeon for whom the slip of a scalpel is possibly fatal, is always perilous. Laport knows full well that a chromatic harmony as finely tuned as his or edgework as frangible as lace can be ruined in an instant. He issues a vertiginous invitation to conclude the interview, “Get close to the edge and see.”

Charles A. Riley II, PhD is an arts journalist, cultural historian and professor at the City University of New York. He is the author of thirty-one books on art, architecture, business, media and public policy, including Color Codes (University Press of New England), The Jazz Age in France (Abrams), Art at Lincoln Center (Wiley), Rodin and his Circle (Chimei), and Sacred Sister (in collaboration with Robert Wilson). He is a guest curator at the Chimei Museum, Taiwan and curator-atlarge for the Nassau County Museum of Art.

Herbert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly, AllThings Shining (New York: The Free Press 2011), p. 201.

Kenneth Frampton, Studies inTectonic Culture:The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth andTwentieth CenturyArchitecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press 1995) p. 26.

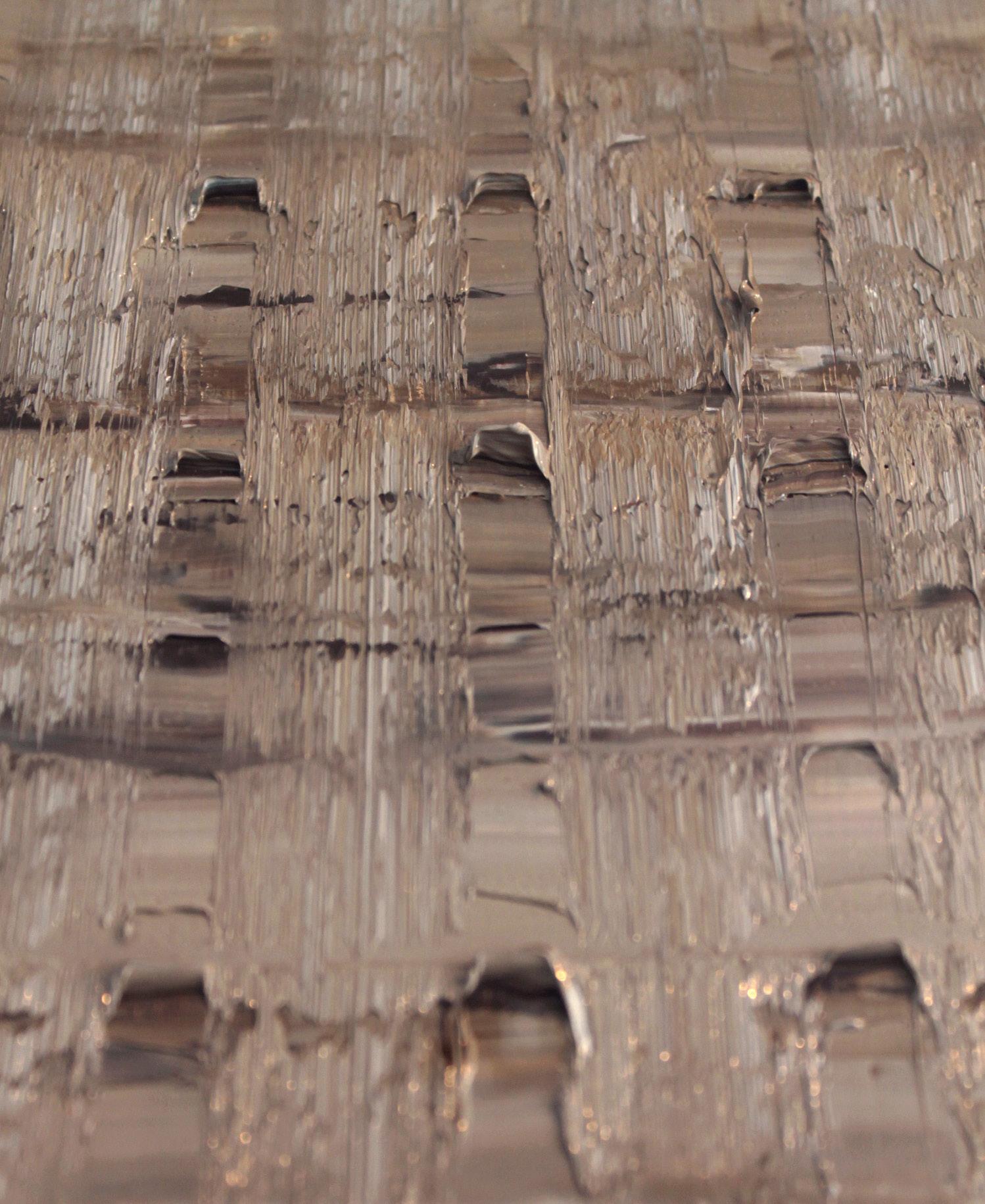

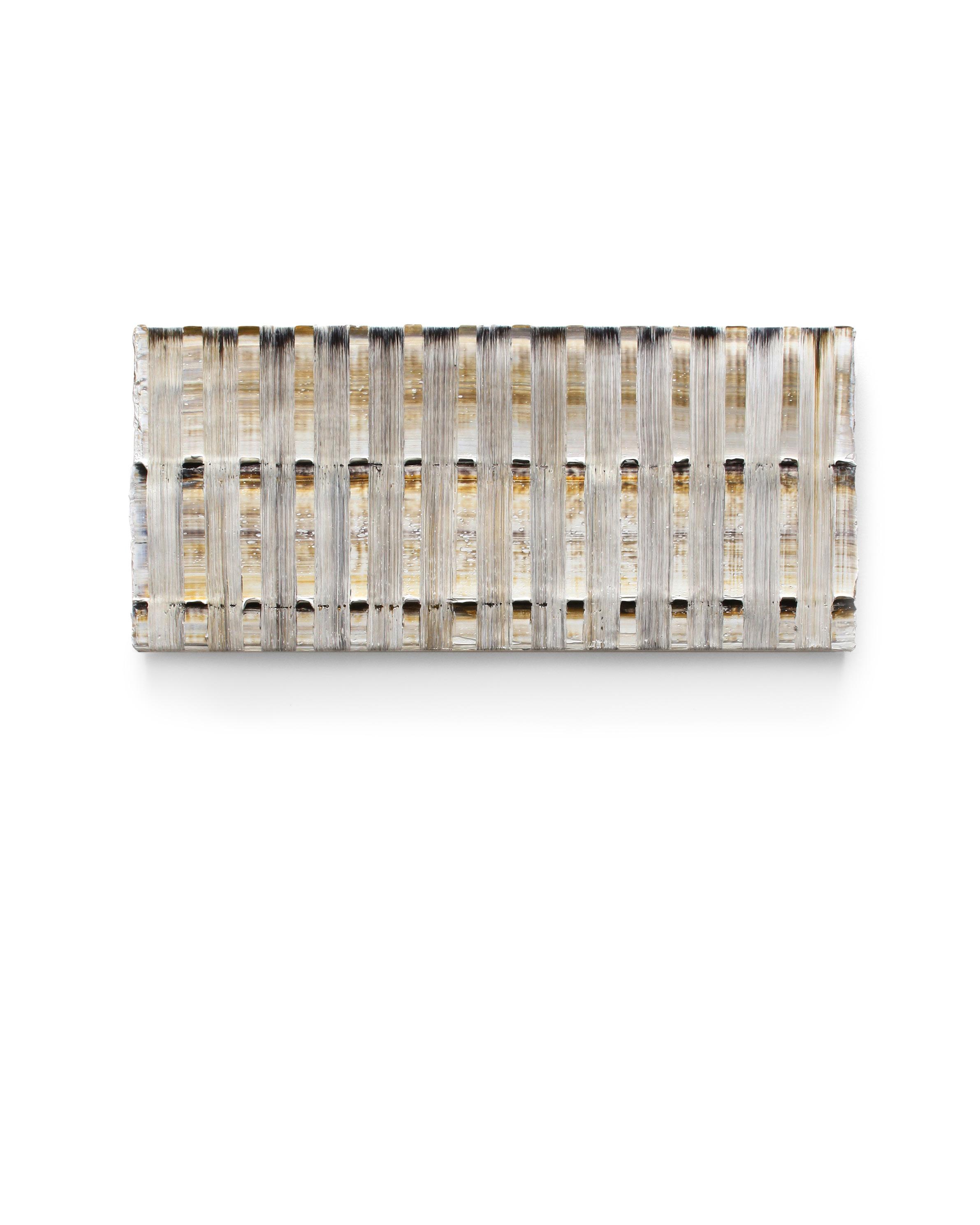

LEKSO (Detail)

LEKSO 2012 oil on plywood, wood and glass 64.6 x 55.3 x 2.8 in (164 x 140.5 x 7 cm)

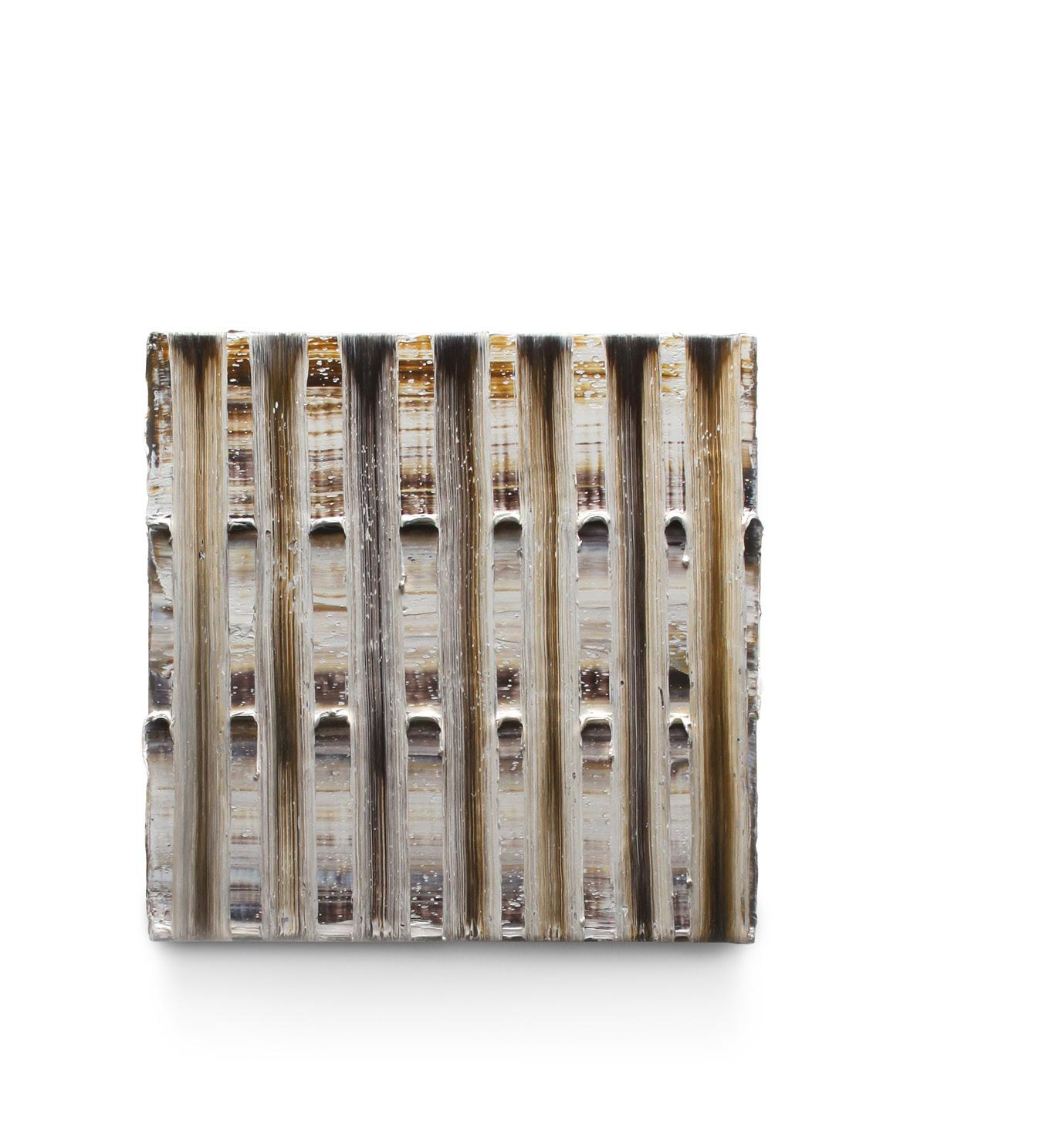

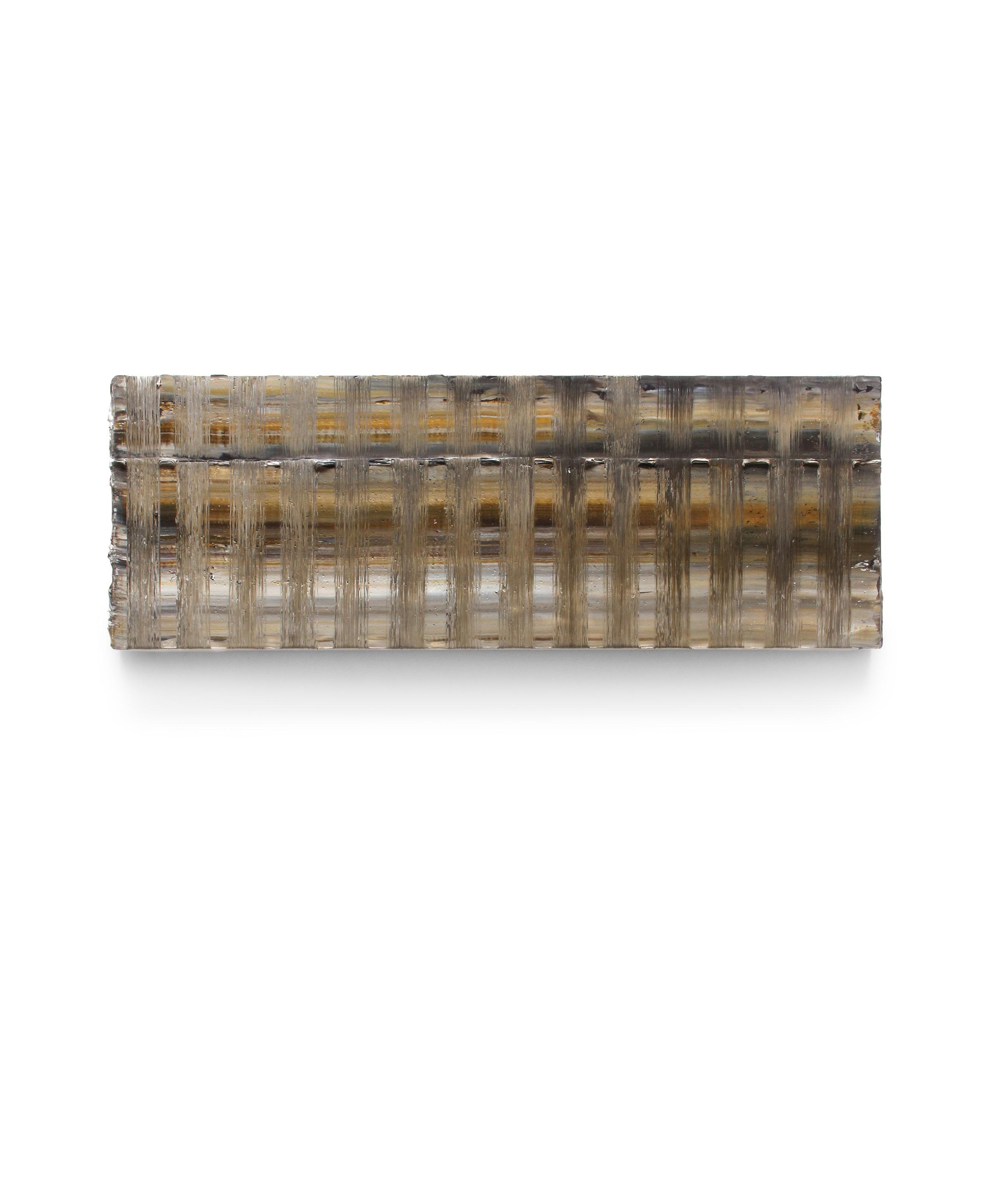

RONIX 2011-13 oil on plywood 59 x 47.2 x 2.8 in (150 x 12 x 7cm)

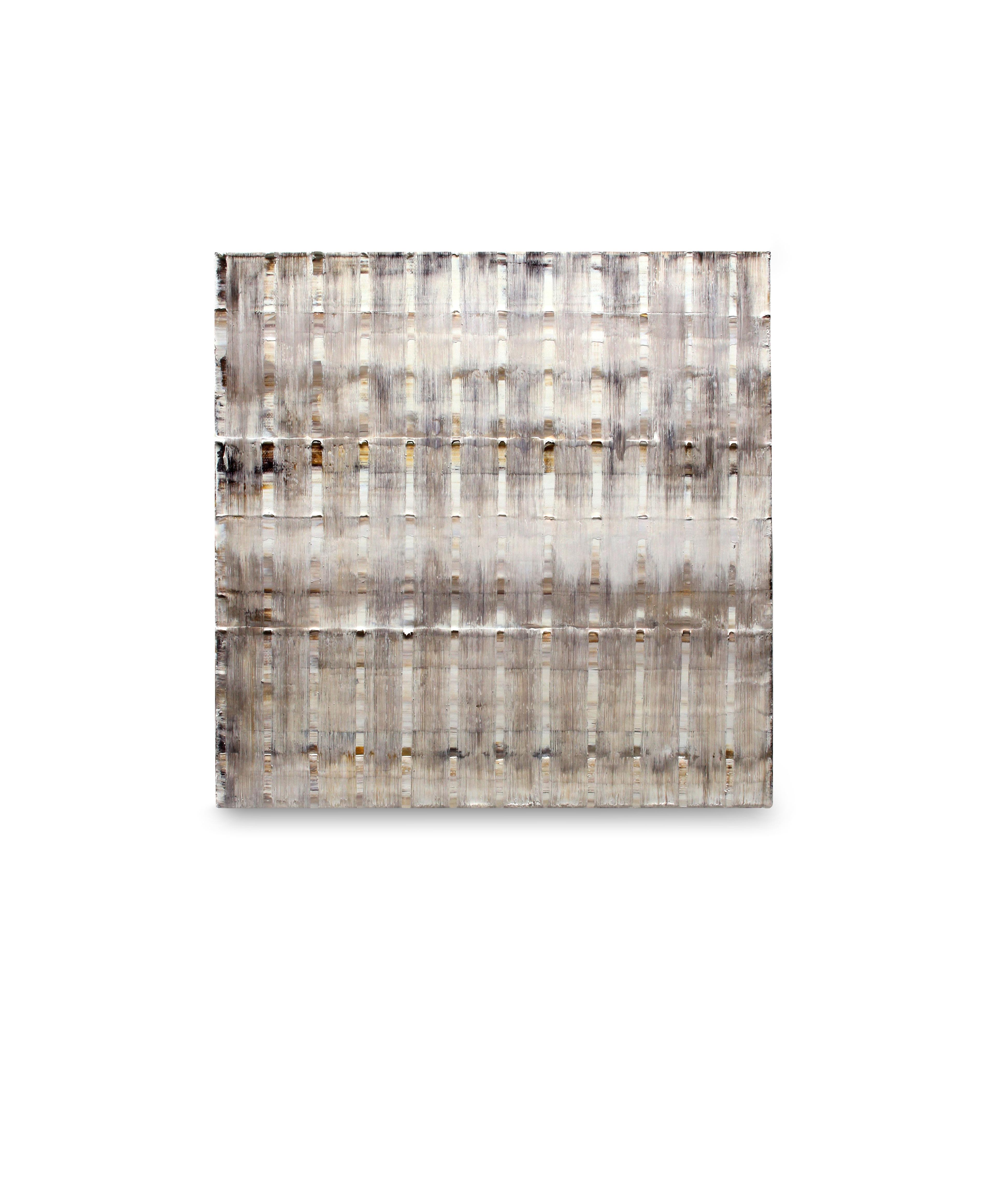

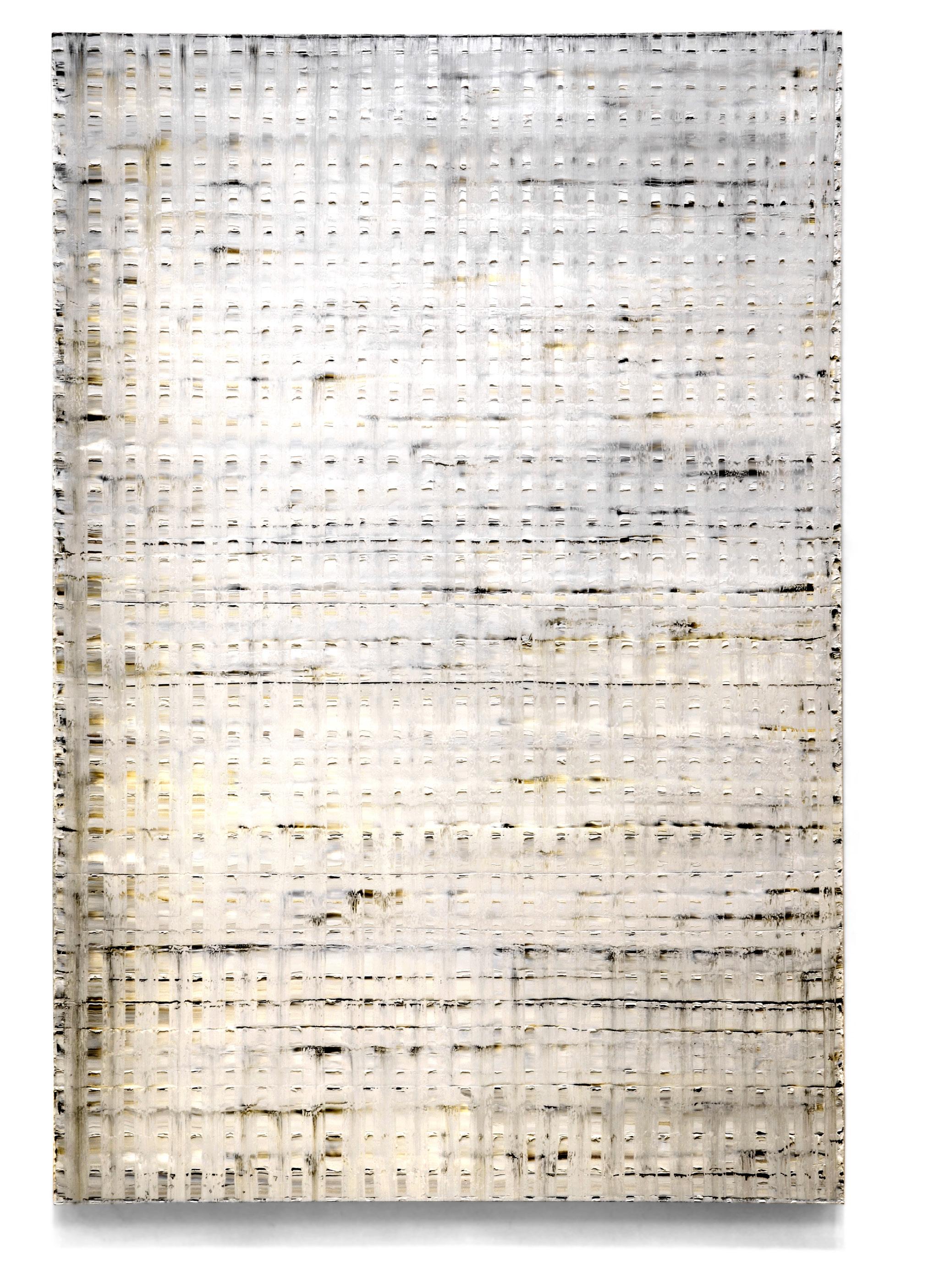

SAXTO 2012 oil on linen

78.7 x 63 x 3.9 in (200 x 160 x 10cm)

DASER 2012 oil on cotton

28.7 x 23.2 x 1.6 in (73 x 59 x 4 cm)

KONIX 2012 oil on paper, wood and glass

44.1 x 32.7 x 2.4 in (112 x 83 x 6 cm)

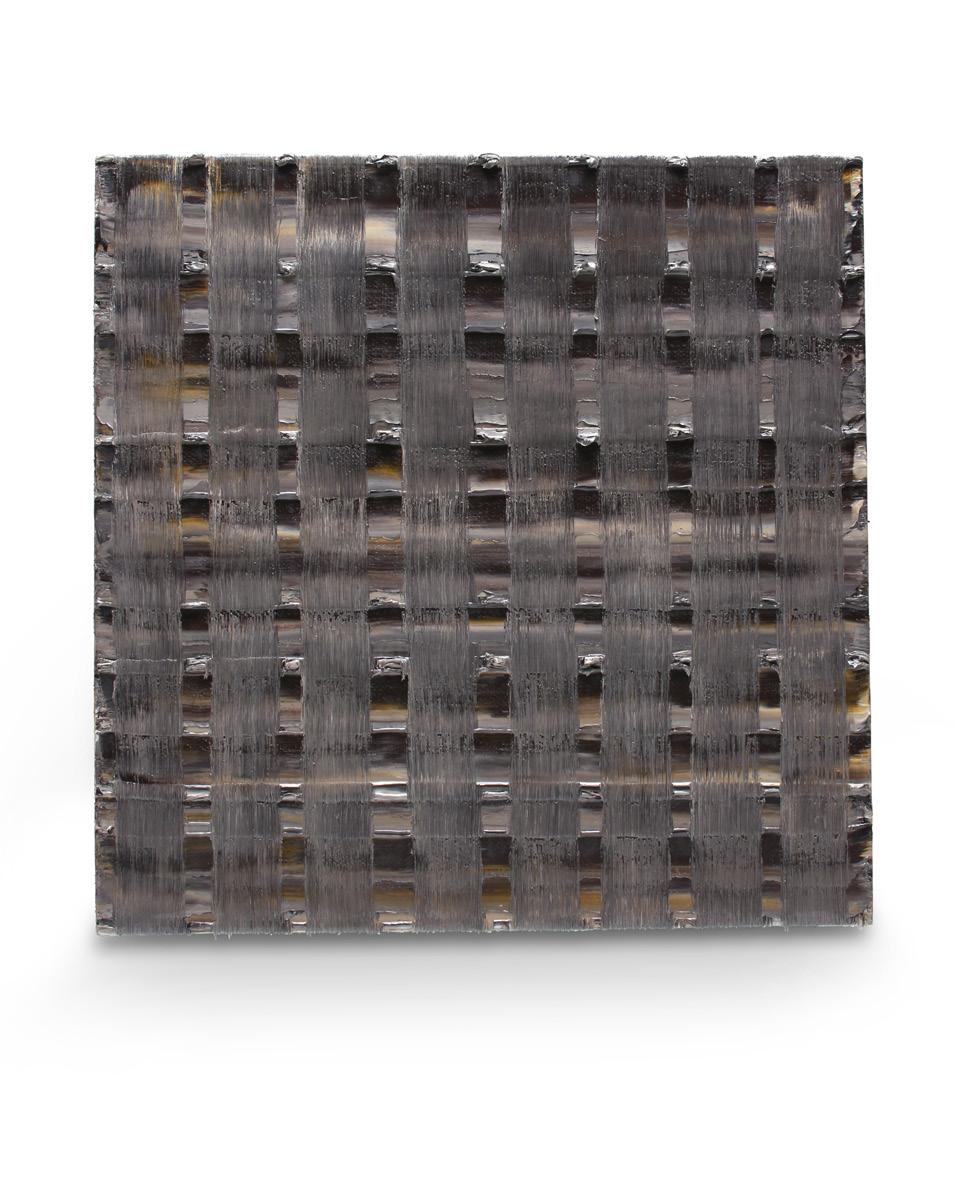

DELFO 2012 oil on plywood, wood and glass

63.4 x 47.8 x 2.8 in (161 x 121.5 x 7 cm)

KIWER 2011 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

KATSEN 2013 oil on linen 37 x 27.6 x 2 in (94 x 70 x 5 cm)

ELKAM 2012 Oil on cotton

47.2 x 31.5 x 1.6 in (120 x 80 x 4cm)

GAPSO 2011 oil on linen

28.3 x 19.7 x 1.8 in (72 x 50 x 4.5 cm)

TWYTE 2012 oil on linen 17.7 x 17.7 x 1.6 in (46 x 46 x 4 cm)

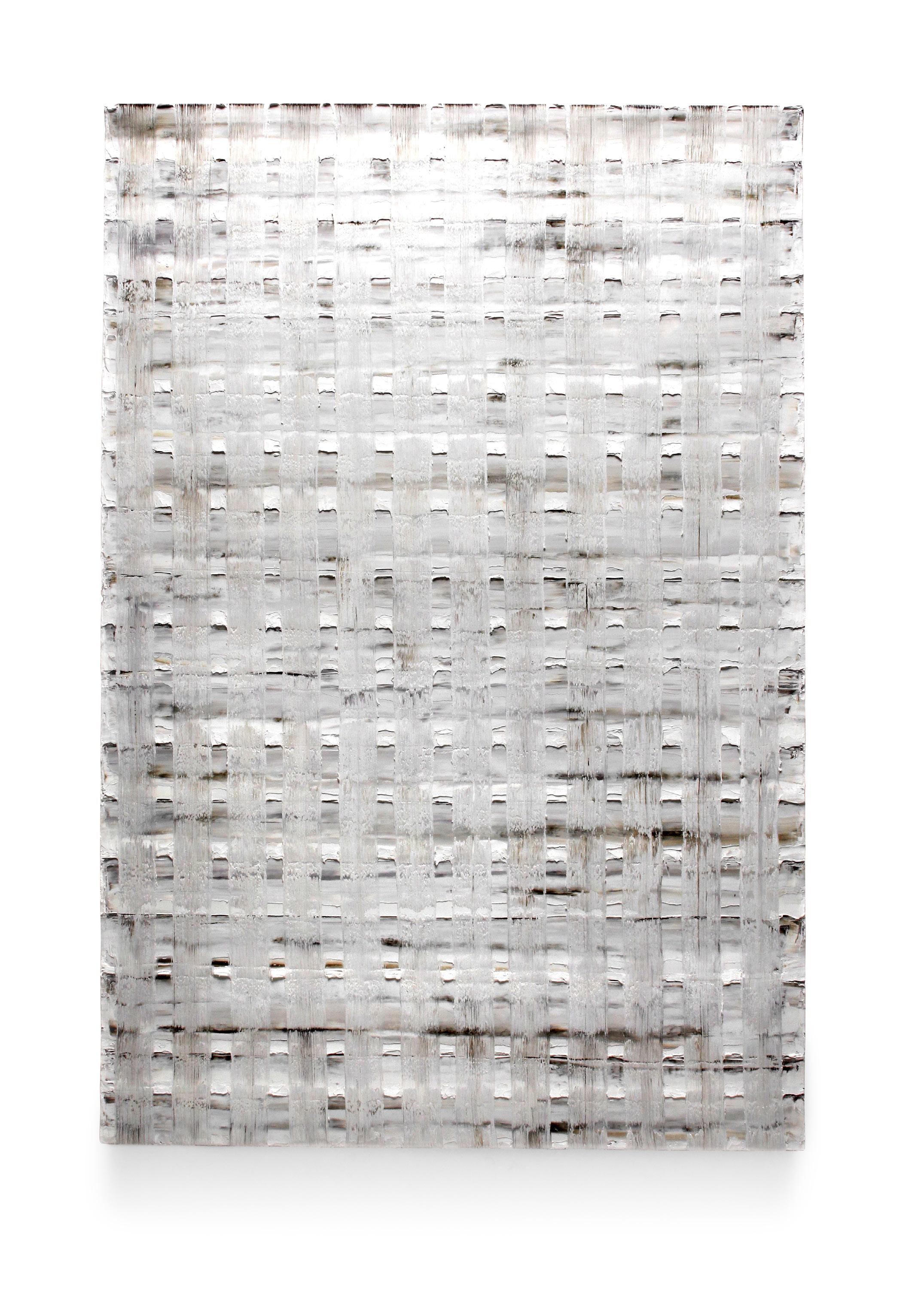

TWANSY 2012 oil on linen

78.7 x 63 x 3.6 in (200 x 160 x10 cm)

MAGMA 2011 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

ZENIT 2011 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

ORANS 2011 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

EZLON 2011 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

LACEN 2013 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

KALOX 2013 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

LEROX 2013 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

TUSKY 2011 oil on linen

13.4 x 13.4 x 1.6 in (34 x 34 x 4 cm)

RALOT 2013 oil on linen 15 x 12.2 x 1.6 in (38 x 31 x 4 cm)

DAKLO 2012 oil on linen

23.6 x 23.6 x 1.6 in (60 x 60 x 4cm)

SLATIN 2012 oil on linen

18.1 x 18.1 x 1.8 in (46 x 46 x 4.5 cm)

TOMKI 2011 oil on linen 70.9 x 47.2 x 2.8 in (180 x 120 x 7 cm)

LAURNE 2013 oil on linen

10.6 x 23.6 x 1.5 in (27 x 60 x 3.8 cm)

OPHEA 2013 oil on cotton 9.1 x 25.6 x 1.5i n (23 x 65 x 3.8 cm)

TORAK 2012 oil on linen 21.3 x 21.3 x 1.8 in (54 x 54 x 4.5 cm)

SPINO 2011 oil on cotton 35.4 x 23.6 x 1.6 in (90 x 60 x 4 cm)

RAKON 2012 oil on paper, wood and glass 44.1 x 32.7 x 2.4 in (112 x 83 x 6 cm)

PAULO LAPORT

b. 1951, Rio de Janeiro

Education

1967-1969

Studied at Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1980-1982 The Art Students League of New York and Pratt Institute, New York.

Solo Exhibitions

2012 Marcia Barrozo do Amaral Galeria de Arte, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2000 GB Arte, Rio de Janeiro Brazil

1992 Galerie Lehmann, Lausanne, Switzerland

1989 Galerie Gerard Leroy, Paris, France

1986 Galeria Montesanti, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1981 Galeria Gravura Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Selected Group Exhibitions

1993 Lehmann Gallery, Lausanne, Switzerland

1992 Art Cologne Galerie Lehman, Germany

1991 FIAC Galerie Lehmann, Paris, France

1991 Musée D’Art Contemporaine FAE, Lausanne, Switzerland

1988 Galerie 1900-2000, Paris, France

1987 Oficina de Gravura e Escultura, MAB/FAA, São Paulo, Brazil

1987 Oficina de Gravura e Escultura, Museu Histórico do Estado, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1985 Velha Mania: desenho brasileiro, EAV – Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1984 Rio Narciso, EAV Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1981 4º Salão Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1980 Sotheby’s Park Bernet Gallery, NYC

1980 Rosto e a Obra Galeria IBEU, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1980 12 Gravadores Brasileiros, Baltimore, USA

1979 4ª Bienal de Gravura Latino-Americana, San Juan, Porto Rico

1979 1ª Bienal Italo-Latino-Americana di Tecniche Grafiche, Roma, Italy

1979 2ª Mostra do Desenho Brasileiro, Curitiba, Brazil

1979 Trienal Latino-americana del Grabado, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1978 2º Salão Carioca de Arte, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1978 1º Salão Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil - Gustavo Capanema Award

1978 1ª Mostra Anual de Gravura Cidade de Curitiba, Curitiba , Brazil– Acquisition Award

1977 3ª Bienal Internacional de Arte, Valparaíso, Chile

1977 1º Salão Carioca de Arte, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1977 Arte Actual de Ibero-América, Madrid, Spain

1976 Bienal Nacional 76, na Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil

1976 25º Salão Nacional de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

1975 Goiânia GO - 2º Concurso Nacional de Artes Plásticas Caixego , Brazil – Acquisition Award

1968 Rio de Janeiro RJ - 1º Salão de Verão – Museum of Morden Art, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

136 East 74th Street

New York, NY 10021

+1 212 472 7770

info@edelmanarts.com www.edelmanarts.com

Charles A. Riley II, PhD

Design and Production: Traffic www.trafficnyc.com

Essay: