WRITING CENTER EXPERIENCES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS COLUMNS

Editors’ Introduction: Voicing Writing Center Experiences

Alexandra Gunnells and Samantha Turner

FOCUS ARTICLES

Mapping It Out: Rhizomatic Learning of Peer Embedded Tutors for Composition Classes – A Case Study

Iwona Ionescu

Untapped Potentials: Leveraging Disciplinary Expertise for Graduate Writing Consultant Education

Vicki R. Kennell, Ashley Garla, and Genevieve Gray

“How I Speak Doesn’t Really Matter, What I Speak About Does”: BIPOC Tutor Voices on Linguistic Justice in the Writing Center

Chloe Ray and Erin Goldin

Reexamining “Attitudes of Resistance”: A Survey-based Investigation of Mandatory Writing Center Appointments

Chris Borntrager and Taylor Weeks

Coming to Terms: A Quantitative Analysis of Naming Conventions and of U.S. Writing Centers

Abraham Romney

Evolving Perceptions of GenAI Writing Tools: Why Writing Centers Should Be GenAI Pioneers

Nathan Lindberg

BOOK REVIEWS

Review of Critical Thinking in Academic Writing: A Cultural Perspective

Jonathan Faerber

Review of The Creative Argument: Rhetoric in the Real World

Alex (Oleksiy) Ostaltev

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Iwona Ionescu earned an MA degree in English Philology from Warsaw University, Poland, and an MEd from the University of New Orleans. She is currently a PhD candidate in Composition and Applied Linguistics at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Iwona works at Rider University where she teaches first year-composition (FYC) and has coordinated composition tutoring. She has also worked as an English as a Second Language (ESL) instructor, a professional writing tutor, and a high school English teacher. Iwona’s academic interests include writing centers, FYC pedagogies, L2 writers, and students’ development of their writing voices in the era of AI.

Vicki R. Kennell, PhD, is an associate director for graduate and multilingual education at the Purdue OWL. She has mentored graduate writers and graduate consultants for over a decade. Her research focuses primarily on graduate writing and the administration of programs to support it.

Ashley Garla holds an MS in Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences and is an SLP clinical fellow. During graduate school, she worked as a generalist writing consultant at the Purdue OWL.

Genvieve Gray holds an MS in Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences and is an SLP clinical fellow. During graduate school, she worked as a generalist writing consultant at the Purdue OWL.

Chloe Ray is the Assistant Director of the Center for Writing and Public Discourse at Claremont McKenna College. Her research interests include the development and practical implementation of anti -racist and justiceinformed pedagogy, writing center administration and tutor training, Mixed-Critical Race Theory, and environmental rhetoric.

Erin Goldin is Director of the University Writing Center at University of California, Merced. She is a board member of the Northern California Writing Centers Association. Her scholarly activity is centered on examining the complex, multi-faceted nature of academic literacy development and work that contributes to effective, inclusive practices that meet the needs of diverse student populations.

Chris Borntrager is the Writing Studio Coordinator at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Oriented around questions posed from within discourse studies, his research agenda focuses on the teaching of writing and its role in social life, focusing on literacy studies, media ideologies, critical discourse analysis, and critical analyses of educational practices.

Taylor Weeks is an instructor at the University of Arkansas, emphasis in Rhetoric, Composition, and Literacy. His research interests include writing center pedagogy, military student veteran services/support, first-year writing, labeling theory, technical communication and professional writing, and curriculum design, program administration, and digital content creation.

Abraham Romney is Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Composition at Idaho State University. He studies the history of rhetoric in Latin America and contemporary approaches to rhetoric and the teaching and administration of writing. Before coming to Idaho State University, where he has served as Interim Director of Composition, he worked at Michigan Technological University as the Director of their Composition Program and as director of the Michigan Tech Multiliteracies Center.

Nathan Lindberg is a Senior Lecturer for the English Language Support Office (ELSO) at Cornell University and Director of ELSO’s Writing & Presenting Tutoring Service. This spring, he’s teaching a new class called Strategies for Writing with AI and writing a blog about it the URL is in his article’s Works Cited.

Johnathan Faerber has worked as a writing tutor and instructor at five institutions over the past decade and is currently an Academic Writing Specialist at Royal Roads University, located on the traditional lands of the Lekwungen-speaking peoples in present day Victoria, British Columbia.

Alex (Oleksiy) Ostaltev is a PhD Candidate at University of Texas at Austin (Comparative Literature). He is currently working on his dissertation dedicated to the problem of representation of a person in literary texts of Classical, Medieval and Modern periods. In 2020 he received an M.A. degree in British and American Literature. His primary sphere of interest is classical texts of national European traditions (Russian, British, French, German). Alex is the author of two books of short stories.

EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION: VOICING WRITING CENTER EXPERIENCES

Alexandra Gunnells

University of Texas – Austin praxisuwc@gmail.com

Throughout our Summer 2025 issue, authors highlight the roles and perspectives of those engaged in the daily work of the writing center across institutional contexts and from various angles. Furthermore, the calls to action across this issue are as varied as the methods employed, reminding us that what we often call “the” writing center is actually composed of abundant complexity and diverse voices.

This issue begins with “Mapping it Out: Rhizomatic Learning of Peer Embedded Tutors for Composition Classes A Case Study” by Iwona Ionescu, who applies the theoretical framework of rhizomatic learning to investigate the diverse experiences of how course-embedded tutors develop their expertise outside of formal training. Ten years after the 2014 Praxis special issue on course-embedded tutoring, Ionescu’s article invites both reflection and innovation as the work of training embedded tutors continues.

Next, Vicki R. Kennell, Ashley Garla, and Genevieve Gray offer “Untapped Potentials: Leveraging Disciplinary Expertise for Graduate Writing Consultant Education,” which examines the intersections between the disciplinary homes of generalist graduate consultants and their writing center work and highlights the untapped potential of the theory and pedagogy of consultants’ home disciplines in developing effective consultant training programs.

Responding to the call for more attention on the perspectives and practices of tutors who employ equitable, inclusive, and anti-racist pedagogies, Chloe Ray and Erin Goldin’s “‘How I Speak Doesn't Really Matter; What I Speak About Does’: BIPOC Tutor Voices on Linguistic Justice in the Writing Center” highlights the factors that impact how tutors at a Hispanic Serving Institution understand and enact linguistic justice in their writing center practices.

Chris Borntrager and Taylor Weeks “Reexamining ‘Attitudes of Resistance’: A Survey-based Investigation of Mandatory Writing Center Appointments,” which “arose out of a need to better understand what happens in writing center appointments that are incentivized or mandated by instructors.” Borntrager and Weeks’ findings encourage future studies into how the field may inhabit a more

Samantha Turner

University of Texas – Austin

praxisuwc@gmail.com

welcoming stance toward the writers who visit WCs at the behest of their instructors.

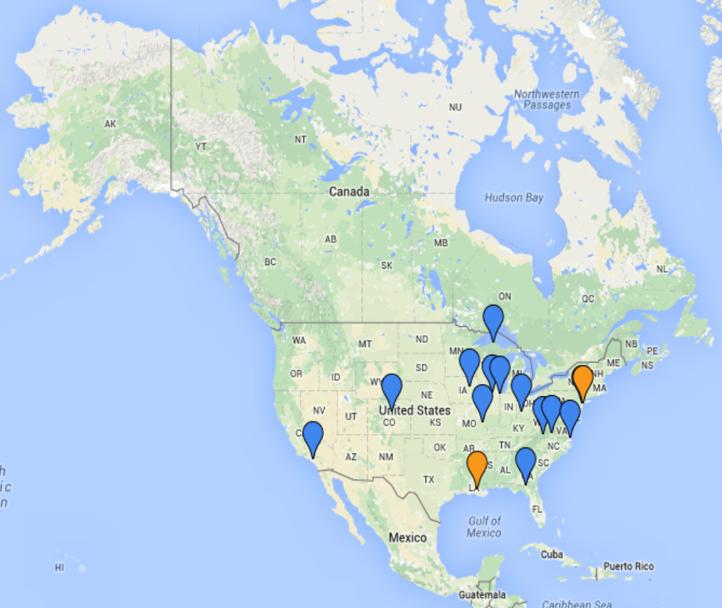

Next, Abraham Romney takes up the issue of naming in “Coming to Terms: A Quantitative Analysis of Naming Conventions in and of U.S. Writing Centers.” Romney assesses workplace and worker naming conventions across nearly 600 US-based writing centers and builds upon conversations that attempt to define the work we do in the midst of a “complex academic landscape of multiple literacies and modes.”

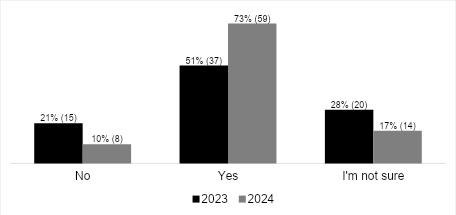

In the last of this issue’s focus articles, Nathan Lindberg contributes to on-going conversations around artificial intelligence by suggesting how writing centers may be well-positioned to explore the affordances of artificial intelligence writing tools. In “Evolving Perceptions of GenAI Writing Tools: Why Writing Centers Should be GenAI Pioneers,” Lindberg reports findings from interviews with students who were “early adopters” of generative AI in order to argue for a future of field-wide engagement with generative AI writing tools.

Finally, this issue ends with two reviews: Shi Pu’s Critical Thinking in Academic Writing: A Cultural Perspective (2023), reviewed by Jonathan Faerber, and Thomas Girshin’s The Creative Argument: Rhetoric in the Real World (2024), reviewed by Alex (Oleksiy) Ostaltsev.

We here at Praxis remain deeply grateful to the reviewers, authors, and copy-editors that helped make this issue a reality. We especially want to thank our brilliant undergraduate intern, Audrey Fife, who provided invaluable assistance (during her summer break!) as we prepared this issue for publication. We close this editors’ introduction with an announcement regarding a change in Praxis’s leadership. Ali Gunnells will be stepping down as co-managing editor to pursue other opportunities, but she would like to express her heartfelt thanks to her co-managing editor Sam Turner and all those involved in Praxis for their continued work and dedication. Though we are sad to say goodbye to Ali, Praxis is excited to welcome Mary Fons to the team this fall as the new co-managing editor.

MAPPING IT OUT: RHIZOMATIC LEARNING OF PEER EMBEDDED TUTORS FOR COMPOSITION CLASSES – A CASE STUDY

Iwona Ionescu Indiana University of Pennsylvania iionescu@rider.edu

Abstract

This article contributes to the writing center scholarship in three ways. First, it revisits and further develops the discussion on courseembedded writing support programs; in particular, it builds on Kelly Webster and Jake Hansen’s “recursive reflection about courseembedded tutoring” and responds to Mary Tetreault et al.’s call for utilizing archival research as a resource for tutor education. Second, it takes a unique approach to tutor education by exploring how embedded tutors for first-year composition classes develop their expertise outside of the formal training sessions. Third, it applies the theoretical framework of rhizomatic learning that has not been previously utilized to investigate the diverse experiences embedded tutors undergo as they acquire and refine their tutoring skills. The qualitative data for this case study were obtained from the Coordinator of Composition Tutoring’s reflective journal as well as session logs and reflections completed by course-embedded peer tutors for composition courses at a four-year Northeastern institution over the period of four semesters. The analysis of the data reveals the rhizomatic character of embedded tutors’ learning, where elements of the learning processes are interconnected and everexpanding (Deleuze and Guattari; Grellier). The discussion includes a set of questions designed to encourage tutors to reflect on their learning processes. Writing center administrators can use these questions to gather data on how tutors develop their skills within their specific contexts.

“Course-embedded tutoring is uniquely complicated and uniquely powerful, and (…) reflective scrutiny is crucial if writing centers hope to realize its potential ” (Webster and Hansen)

Ten years ago, Praxis published a special issue on course-embedded writing support programs, featuring articles on tutoring models for writing intensive or writing across curriculum (WAC) classes, their institutional contexts, elements responsible for their successes, and tutors’ identities. One article concluded with an implicit call for writing fellows program administrators to engage in “recursive reflection” (Webster and Hansen). At that time, I was neither involved in an embedded tutoring program nor familiar with Praxis. Years later, I worked with an embedded tutor (ET) and eventually became the Coordinator of Composition Tutoring (CCT), overseeing the embedded tutoring program for composition classes at the college where I also taught composition as an adjunct. Only then did I come across Praxis and the 2014 special issue. On the tenth anniversary of that issue, striving to ensure the program benefits both students and ETs, I reflect recursively on

the various ways ETs learn their craft outside of training sessions.

When I started my work as CCT, I had experience tutoring at my university’s Writing Studio (WS) and teaching first-year composition (FYC) but no formal background in composition or writing centers. My task was to train twelve peer tutors who would support composition classes, primarily through group workshops. While I found resources for one-on-one tutoring on various websites and received helpful advice from colleagues, I struggled to locate materials for training ETs in group workshop settings. I envisioned ETs’ learning process in a linear, top-down fashion: I would train ETs, and they would apply what they have learned to their work with students (fig. 1). This model reflected Paulo Freire’s banking concept of education, or transmission teaching, where teaching is viewed as “an individual act with casual correspondence” (Strom and Martin 113). This model is echoed by Francesca Gentile: “We train our tutors, we oversee their work with students (to varying degrees), and we hope that something sticks when they move into the classroom or workplace.”

Figure 1. My initial mental representation of ETs’ learning process.

This orderly model was a comfortable starting point, but, as the first semester unfolded, it proved too simplistic. ETs were not blank slates: some had already tutored writing or other subjects; others had taken a course on theories of writing and tutoring offered by another faculty member at our institution; still others studied to become teachers, eager to transfer their teaching skills to a tutoring context. ETs would also work with professors who varied in teaching style, expectations, and understanding of ETs’ roles. These inconsistencies brought to mind Gaelen Hall’s statement: “Every meeting presents unique variables and challenges” (26). Hall uses the expression “navigating chaos” to capture the unpredictable nature of writing conferences and the need to embrace this unpredictability. “Navigating chaos” seemed to describe my experience as well, as each semester worked with unique teams of ETs, who tutored unique cohorts of students, and formed unique dynamics with professors whose classes they supported.

Other writing center (WC) administrators seemed to share my experience. Nicole Caswell et al. cite directors who felt unprepared in their roles, many wishing they had been told how “it’s really done” (15). One director described a situation much like mine: “depending on what populations are, depending on what issues we have from semester to semester, I can’t say that our training will translate to exactly the same for everyone at this place in level 2” (53). New administrators, authors note, had to navigate their unique local variables alone. Similarly, when I spoke with a local Writing Tutor Administrator group, I learned that no two embedded tutoring programs were alike.

The embedded tutoring program for composition classes at my institution operates under the WS, managed by the Assistant Director of Academic Tutoring. The CCT, however, reports directly to the Director of the Academic Success Center. Our program shares many features with the first writing fellows program developed at Brown University in the 1980s, which emphasized collaborative learning (HaringSmith). Our goal is to promote writing as a collaborative, social activity. We support FYC courses and we work with all writers in those classes, regardless of skill level. While not all embedded tutoring programs include mandatory group workshops, ours does. These noncredit bearing workshops are placed on students’ schedules, and students are required to attend eight sessions each semester. Over time, we have built strong partnerships with many faculty members, and each semester, the program supports approximately 25 sections–about half of all the composition sections.

Our ETs are high-achieving undergraduate students selected through faculty recommendations, and they represent a range of majors, such as education, political science, musical theatre, English, and psychology. Their responsibilities include attending their assigned class once a week, planning and facilitating group writing workshops outside of class, meeting with the course instructors, attending weekly training, holding individual appointments, and providing asynchronous feedback on papers.

In the next section, I review scholarship on embedded tutoring that supports writing and present the theoretical lens I use to map ETs’ learning.

Literature Review

Course-embedded writing support

In course-embedded writing support, tutors are assigned to specific courses to help students improve their writing and reading skills while serving as peer role models. These tutors offer course- and instructorspecific support for writing-intensive, WAC, or Writing in the Disciplines (WID) courses. The goal is to improve students’ reading and writing skills, modeling successful student behavior, fostering collaborative learning, and strengthening student and faculty engagement with the WC (Webster and Hansen).

Scholars have documented the effectiveness of course-embedded peer tutoring across disciplines. Tori Haring-Smith argues that peer feedback “helps writers retain authority over their own texts” (124) and it encourages students to revise their work before submission. Kevin Dvorak et al. report that research students who worked with writing fellows “produced significantly stronger writings at the end of the semester.” Mitchel Colver and Trevor Fry indicate that first-generation students, in particular, benefit from embedded tutoring. ETs not only positively influence students' writing but also impact their mindset (Miller), and faculty find embedded tutoring beneficial (Bleakney et al.). Embedded tutoring yields positive results in online contexts as well. Dayra Fallad Mendoza and Elizabeth Kerl report that undergraduate students who were enrolled in online English, history, and economics courses and worked with an ET felt more supported in those courses, were more comfortable participating in class, displayed higher levels of engagement in their learning, and felt a stronger connection to their class. Embedded tutoring has also been found to reduce feelings of loneliness in online courses (Reimers).

Course-embedded tutor learning

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

Training is essential in any writing fellows program (DeLoach et al.; Macdonald). Ross MacDonald notes that the combination of tutoring and tutor training is the most significant factor linked to the academic success of developmental education students, and training for ETs needs to be tailored to their specific support role as working with small groups of students requires learning additional skills, i.e., ensuring all tutees participate actively in a workshop.

A review of scholarship from the past decade, specifically in Praxis, Writing Center Journal, and WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, reveals limited attention to training course-embedded writing tutors. Ben Ristow and Hannah Dickinson stress the need for specific training due to the high level of scrutiny ETs face in their work with faculty and students with respect to their reading, writing, and thinking skills. Tara Parmiter and William Morgan highlight the importance of supporting tutors as they develop disciplinary expertise over time. Danielle Pierce and Aolani Robinson explore the use of an online platform with fiction games to enhance problem-solving skills training for course-embedded tutors. Amanda Greenwell provides ideas for training that focus on strengthening tutor reading skills and on strategies designed to support students’ reading in one-on-one and course-embedded contexts. Finally, Kelly Webster and Jake Hansen suggest that course-embedded programs should offer tutors a chance to undergo a potentially transformative "developmental experience" that will shape their future roles as both tutors and writers. In the current study, I contribute to the scholarship on ET by using the rhizomatic lens to examine the multiplicity of ways in which ETs develop as, or become, tutors at my institution, specifically outside of their formal weekly training sessions.

Rhizomatic Approach to Learning

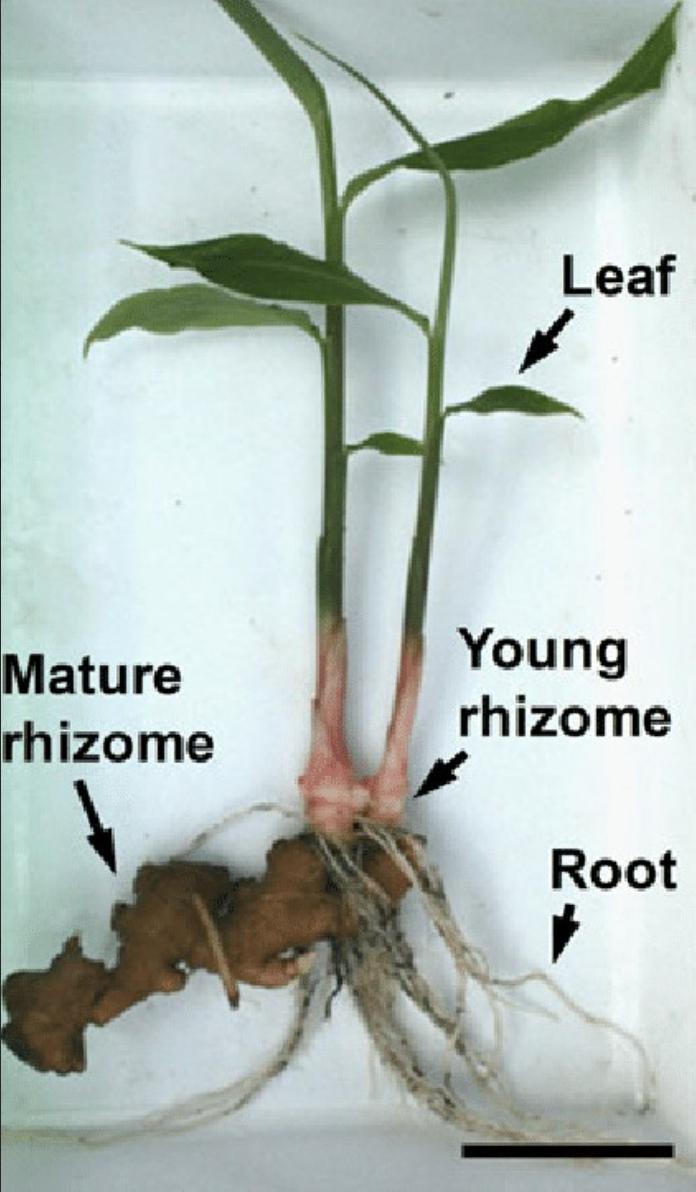

In rhizomatics, a philosophy developed by Gilles Deleuze and Pierre-Félix Guattari, processes or phenomena are seen as networks of interconnected, ever-expanding elements. These networks have no central points, similar to the structure of plants such as ginger or turmeric, which have underground horizontal rhizomes, with nodes from which roots and shoots grow (fig. 2). In Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatics, traditional power dynamics are undermined, as various elements–nodes or points of connection–are linked by lines with no specific direction, referred to as lines of flight

Deleuze and Guattari postulated that the world is in a constant state of flux, with individuals continually becoming new versions of themselves in relation to societal roles such as gender, family, or profession. Another key rhizomatic concept is assemblage: the coming together of various elements to form a complex network. Scanlon et al. define it as “all spaces and elements related to learning and teaching” (3). Here, I adjust this definition to all spaces and elements related to the development of ETs’ craft, which I present in the findings.

Scholars have applied rhizomatics to the learning of English as a Second Language. For example, Miso Kim and Suresh Canagarajah apply the rhizomatic approach to map out the human (e.g. teachers, peers) and non-human (e.g. Internet, laptop, podcast) elements that shape language learning and usage of Korean

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

professionals. Doris Dippold et al. argue for the use of rhizomatics to understand students’ becoming graduate students. Rhizomatics has also informed research on teachers’ professional development and the process of becoming a teacher (Charteris and Smardon; Hordvik; Scanlon et al.; Sherman and Teemant; Strom and Martin), the writing process (Samson et al.), and firstyear college students’ and tutors’ experience (Grellier). Yet, the rhizomatic approach has not been previously applied to map out elements contributing to tutor learning.

Methodology

The primary objective of this case study is to engage in recursive reflection (Webster and Hansen), to make visible the various ways through which ETs developed skills outside of their formal weekly training sessions. The data, collected over four semesters at my institution, spans the start of my work as the CCT and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. I analyzed archived records and my own reflective journal to find whether the program provided meaningful learning experiences for ETs. This process allowed me to revisit and learn from our local practices. The current study captures ETs’ learning experiences and reactions to these experiences that may otherwise have gone unnoticed, offering insights for future program planning and for other WC administrators in charge of embedded tutoring programs.

This research was guided by the following questions:

1. How did ETs develop knowledge and skills outside of formal training? In other words, what experiences contributed to ETs’ development of their craft?

2. Were these experiences beneficial for the ETs?

3. How can the findings inform future training design and planning learning experiences for ETs? Or, in Molly Tetreault et al.’s words, “How can knowledge of the past inform the present?”

To answer these questions, I used qualitative data collected as part of my regular record keeping and assessment of the ET program during the course of four semesters, between September 2020 and May 2022. Following Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, I read 1,716 tutor log responses filled out after each weekly group workshop by 92 unique ETs. Next, I coded each response, focusing on how and what ETs reported learning through a particular experience. I also coded 85 end-of-semester evaluations of the program, where ETs responded to questions

about the most important skills they learned from one another, the professors they worked with, their tutees, and CCT. I also drew from my reflexive journal, where I recorded informal conversations with ETs during that period. Rather than counting responses, I aimed to capture the diversity of unique experiences, as my aim is to highlight the diversity of those experiences, not their frequency.

I obtained Institutional Review Board approval. This research was conducted in accordance with the institution’s human research guidelines.

Findings: Assemblage of elements through which ETs develop their craft

To present my findings, I draw on Jane Grellier’s method of organizing findings into nodes–elements contributing to ETs’ learning and points of connection in the network of ETs’ learning experiences. Grellier argues that this approach allows for a blending of academic and reflective voices and bringing to the surface the voices of underrepresented groups, such as first-year students. Similarly, here, I use nodes to mix academic tone with my reflective one and bring to the surface the voices of the ETs. Using nodes instead of themes aligns more closely with the rhizomatic metaphor. Themes tend to categorize experiences, which may imply that they are separate and fixed. Nodes, on the other hand, are points in a web of experiences, connected in multiple directions. This encourages mapping relationships between experiences rather than isolating or ranking individual experiences. Like Grellier, I do not number the nodes to emphasize the fact that each learning opportunity is equally important and there is no starting point. Each node begins with a quote from an ET, and all names are pseudonyms.

Node: Tutee for a day

“When I was stuck, the tutor asked me to talk about my idea, so I did that. Then he said: ‘Good. Write that down.’ It was as simple as that, but it worked!”

Since many ETs had never been tutored themselves, I believed it was important for them to experience what Elizabeth Buck calls an “uncomfortable active position” and Mary Pigliacelli describes as “the vulnerable position of student writer.” I encouraged each ET to book an appointment with an experienced tutor in the WS and work on a writing assignment for any of their classes. Kate, for instance, met with a professional tutor and the following semester applied a strategy she learned (quoted above) during that session while tutoring a novice ET in a “tutee for a day”

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

activity. She mentioned this informally to me, and I later read about it in a reflection written by the novice ET. That moment showed me the program’s potential to foster collective knowledge building (Cormier). It also shifted my understanding of my role, from a trainer and transmitter of knowledge to a “context creator” and a liaison between ETs. My task became less about directing and more about being present with ETs and documenting their learning.

Node: Weekly group workshops

“Every group that I have had so far have wanted something different from my sessions and I have had to adapt. Some students are more visual learners, others like to do things themselves and it can be kind of difficult trying to incorporate different learning styles into one session, but I have slowly been able to figure it out.”

Weekly group workshops offered tutees structured support for writing and reading while giving ETs, many of whom were aspiring teachers, space to develop instructional skills. Rebecca Cruz and Katie Galahan reported that tutors believed conducting workshops required a different approach from holding one-on-one sessions and that tutoring and managing groups resembled teaching. Indeed, in our context, ETs often began their workshops with a mini-lesson, followed by tasks where tutees applied the learned skills However, ETs often needed to adjust their session plans, depending on who attended the workshop. One of our ETs designed and led a training session, where she described various realistic group workshop scenarios. She asked ETs to consider what they would do if, for example, they came to a session planning to engage students in peer review work and five students showed up to the session–each at a different stage of the writing process and each needing a different kind of support. Other issues that arose during workshops were giving equal focus to individuals and the group as a whole (Titus et al.); tutees being disengaged; one student dominating a session; or, very rarely, a student disrupting a session. ETs shared and discussed these experiences and offered ideas on how to address them.

ETs noted that a successful session depended on establishing rapport with tutees and learning to read tutees’ energy and responding with greater empathy and flexibility. ETs also learned to guide rather than direct. As one of them put it, “I learned the importance of asking ‘why.’”Another reflected, “I did feel like I still have to get a bit better at leading the students to the answers instead of giving them the answers, but I have more time to get to that point. I'll learn.” Last, but not least, ETs gained insight into their tutees’ writing processes, which in turn deepened their

awareness of their own writing: “I continued to learn that I need to vary how I am integrating sources in my paper.”

Node: Tandem workshops

“Holding a workshop together is so much fun: from prepping for it to actually holding it. It was also much more relaxing for me as I knew I could rely on Anna if something goes wrong. The students seemed to like it a lot, too, and they were more active in the session.”

Two ETs, Melanie and Anna, decided to hold a group workshop together. Melanie noted that holding a workshop alongside another tutor provided an example of effective collaboration for the students, who witnessed how the ETs bounced ideas off each other. The ETs noticed that during that particular session, students became more engaged than usual and opened up to the ETs. This “tandem workshop,” as they called it, allowed Melanie and Anna to split the group in two, offering the tutees choices as to how they would like to spend their time in the workshop and allowed the ETs to provide more individualized assistance. Having learned how successful the tandem session was, I tried to encourage other ETs to prepare and hold sessions together; however, only one more pair of ETs tried that approach during the study period.

Node: Peer observations

“One suggestion Beth had was to include more visuals to help keep the focus and understanding. Another observation she shared was that we tend to put a lot of decision making onto the students both for what to do as well as for speaking up and answering a question which cause some long pauses or indecisiveness at times, so next time I would like to try to be more assertive and direct with instructions/calling on people.”

Julia Bleakney notes that “peer observations are the second most common type of tutor education.” In our program, observations were conducted using session recordings, documented as a valuable resource for tutor learning (Funt and Esposito; Pigliacelli). ETs recorded two workshops per semester and received feedback on at least one. Initially, I tried to review all the recordings by myself, but I quickly realized that watching 50-minute sessions from 25 ETs per semester, about 40 hours of recordings, was unrealistic. Instead, I invited experienced ETs to provide feedback. This approach created a reciprocal learning opportunity: the observed ET received constructive feedback, while the observer gained insight into how their peers approached group tutoring and what techniques they used.

Node: ETs’ coursework

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

“Previously, [a student] was almost too willing to take my feedback. I decided to give her a music analogy. I said your voice as a writer is a classical orchestra. My voice is a rock band. If you accept everything I say, you'll lose your sound as an orchestra and you'll let my rock and roll self overpower you, and we don't want that. We want to hear your beautiful sound. Once I was done explaining this to her, she began challenging my comments. This not only helped make her paper more uniquely hers, but it also helped me to think about what I was saying to her and other students.”

Cruz and Galahan observed that tutors frequently draw on their own classroom experiences when leading workshops. For example, in her publishing course, one ET learned that a writer should not easily accept what an editor suggests; instead, both writer and editor should engage in a negotiation of meaning. Using a music analogy, the ET started encouraging her tutees to question her suggestions. She turned what she learned in one of her classes into a tutoring strategy and thus created “connections between contexts” (Driscoll and Harcourt 2).

Similarly, another ET, a film and television major, connected revising essays with editing interviews she practiced in her documentary class. She guided tutees to cut unnecessary content as part of an effective revision.

Node: ETs’ other employment

“I definitely drew a lot of connections as a dance teacher. I apply teaching techniques that I use as a tutor to my dance students, and I’ve found myself becoming better in that field now, too.”

“The connections that I can make would be my coaching job. They are both helping students just in different ways since this is a writing program and I coach gymnastics. They both involve improving the student’s ability.”

In their reflections and casual conversations, some ETs stated that their outside jobs, such as teaching dance or coaching gymnastics, informed their tutoring and vice versa. One ET recalled how during a campus orientation, where she worked as a peer leader, she made sure she communicated information clearly with a family. She even compiled a written list of the key points, ensuring the information is as accessible as possible, drawing directly from her tutoring strategies. These connections illustrate the value of encouraging tutors to bridge their work with other experiences (Driscoll and Harcourt).

Node: Conferences

“I remembered from a MAWCA conference how music helps to inspire writing, so I tried to put on music that was magic-inspired to help students with their creativity.”

Attending conferences may offer tutors transferable skills such as public speaking or opportunities to turn presentation topics into research projects. Bleakney reports that some programs include attending and presenting at conferences as part of tutor education. During the period analyzed here, six ETs presented at one local and two national conferences. Some designed, conducted, and analyzed surveys, and all shared their reflections with other ETs during our training sessions. These experiences also shaped our program. One team of presenters emphasized the need for ETs to be taught about empathy more explicitly, leading us to revise our tutor logs to include a question: “How did you show empathy during this session?” One ET later noted that the question prompted her to be more intentional about practicing empathy when working with students.

Node: Mentor groups

“Pauline was my assigned peer ET and I have learned so much from her (even outside of just tutoring stuff). For example, she shared a couple of really great ice breakers I can use with my students. But I think one of my biggest takeaways overall from her and all of the different ETs is the fact that we all have really similar experiences with students. This makes me feel not alone in my struggles and they serve as a really good resource for us to learn from.”

Mentorship is one of “the important aspects of generally-accepted writing center pedagogy” (Aikens). Bonnie Devet emphasizes the importance of creating spaces for novice tutors to learn from experienced consultants, and Holly Ryan notes that peer mentorship can support supervisors in providing feedback. Following these insights, I introduced mentor groups, where novice ETs were paired with veteran ETs to exchange experiences, share knowledge, support one another, and build community. Since most ETs work independently outside of weekly training, these groups offered space for collaboration.

Node: Composition instructors

“My professor was a wonderful example of how to command a room of students while being very personable and individualized to students. Working with her also improved my communication and collaboration skills.”

“Before tutoring for this class, I was unsure of how to write an abstract. Now, I am able to write an abstract, thanks to the professor.”

Megan Titus discusses the importance of instructor-ET collaboration and describes how she gradually gave her ET more responsibility to design and lead class workshops. Ideally, ETs in our program would work with professors whose class they had taken before, but scheduling made this difficult. As a result, ETs sometimes worked with instructors whose teaching styles were unfamiliar to them. In the classroom, ETs’ roles varied: some observed quietly and took notes, while others joined discussions, presented material, or led peer review sessions. Through these experiences, ETs reported learning key professional skills: taking responsibility, expecting the unexpected, staying positive, and managing a classroom. One ET shared that working with his assigned professor inspired him to change his plans after graduation: he decided to pursue an academic career.

Node: Tutees

“I learned about other aspects of what makes a story! The students shared some ideas that originally had not crossed my mind!”

De-emphasizing the traditional hierarchy, where experts pass down their knowledge to novices, repositions tutors as co-learners (Trimbur). One ET reflected on this shift: “It was interesting because both the student and I were confused when figuring out how to structure the essay. The requirements in the assignment itself were a little difficult to work with, so we had a good discussion. We threw ideas back and forth talking about what might work and what might not work. Eventually, the student reached something that worked for them.” Recognizing that they, too, are students, helped ETs feel less pressure to act as experts. Instead, they understood their role as peers, modeling their own approaches to learning and problem solving. In these moments, ETs “co-construct[ed] collaborative sessions with students” (Pigliacelli).

Node: Inventory of strategies

“Sitting Questions: Don't get anxious when the students in your workshop don't respond to questions right away or at all. Let your

question sit before prompting them to respond again. Consider typing the question into the chat so that they actually see it and read it.”

Tutors often build on materials created by other tutors and scholars suggest revising these materials periodically and making them available for other tutors (Cruz and Galahan). The entry above comes from our “Inventory of Strategies,” a living document of strategies ETs have used in their sessions. I began compiling it while viewing workshop recordings, then I invited a group of ETs to revise the document and name each strategy. Arranged alphabetically, these strategies are authentic activities our ETs have used. Each semester, we update and reshare the “Inventory,” connecting ETs across semesters. The document functions as a record of our collective knowledge, a resource that transcends time and space, allowing ETs to learn from one another, reuse strategies, and contribute new ones.

Discussion

In response to the first research question (How did ETs develop knowledge and skills outside of formal training?), the findings reveal that ET learning is far more complex than the two-element vertical depiction I initially created as a novice CCT (fig. 1). To better represent this complexity, I developed a new rhizomatic model (fig. 3), which is an assemblage of nodes (learning experiences) and lines of flight (non-hierarchical connections between the nodes). Seeing tutors’ learning as rhizomatic and composed of interconnected nodes reframes their development as non-linear, collaborative, and continually evolving. It helps us better understand how flexible and messy tutor learning is. It shifts the focus from “What should I teach my ETs?” to “What kinds of experiences, connections, and reflections help ETs become effective tutors?” At the core of this model are reflection and idea sharing, essential to both individual learning and collective knowledge construction.

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

Figure 3. My current rhizomatic model of developing ETs’ craft.

The figure above illustrates the many elements of ETs’ learning assemblage. The nodes discussed in the Findings section are part of a broader web of experiences that also includes other elements such as weekly training sessions, guest trainers, or textbooks. Each node contributes to ETs’ learning and connects, often unpredictably, to other nodes. Empty boxes represent possible, still undefined future experiences. The nodes unfold non-linearly as ETs immersed themselves in the learning processes following their unique paths, shaped by the uniqueness of each semester, sequence of activities, ETs’ individual choices of activities, pace of task completion, and interactions with students, professors, and other ETs. The node metaphor represents not only one element that connects to other elements, but also the potential for new connections and growth. It contains the idea of multiplicity of possibilities as well as equality since all nodes are of equal importance. While Grellier posits that the rhizomatic paradigm emphasizes the disruption of hierarchies, this may be less true in our context. Although working with students in a classroom impacts the sense of authority shared between the instructor and tutor (Spigelman and Grobman), ETs, especially the new ones, still associated authority with CCT and the instructor whose class they supported.

Kathryn Strom and Adrian Martin advocate using rhizomes not just as a metaphor but also as

“analytic tools that provide a more complex, nuanced interpretation of the multiplicity and composition of elements that constitute the nature of teaching” (7). In this sense, the above assemblage of nodes serves both as an analytic tool to understand how the ETs at our institution learned, and a way to record and further archive ETs’ learning experiences. Like a reverse outline, the assemblage maps the learning experiences the program offered to ETs. It consists of human (fellow ETs, tutees, CCT) and non-human elements (video recordings, inventory of strategies) interacting with one another across time (several semesters) and space (in-person: classroom, WS; remote: a dorm room.) Always incomplete, with nodes constantly being added, removed, or replaced, this rhizomatic assemblage captures the richness and messiness of ETs’ development.

To illustrate how a rhizomatic diagram can be used as an analytical tool, Figure 4 maps the relationship between selected nodes and their connecting lines of flight, using the “Tutee for A Day” activity as an example. The entry point is a training session, during which ETs were asked to book a tutoring appointment to receive feedback on their writing. This was followed by an actual tutoring session with a tutor, after which each ET wrote their reflection and shared it with the CCT. The following semester, this activity was repeated. A novice ET met with a writing consultant, also a veteran ET, who completed the activity the previous semester. The

novice ET shared her reflection with the CCT. She described the strategy the writing consultant used: it was the same strategy the veteran ET had learned when she was tutored. In the subsequent training session, ETs

shared their experiences and reflections. The transfer of this strategy across semesters highlights how learning flows across time and individuals.

4. An example of elements involved in the “Tutee for a Day” learning experience.

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

Rhizomatics invites us to see not only the multiplicity of experiences but also their numerous versions. As each ET engaged with training and learning moments differently, they created their unique versions of those experiences and they were also constantly becoming new versions of themselves. This perspective allows WC administrators to view ET learning as complex and unpredictable. While it is important to design core principles and provide training sessions for ETs, it is equally vital to create space for agency, discovery, and co-constructing knowledge, often outside of the supervisor’s presence and control. In fact, much of the ETs’ craft developed when the CCT was not present.

ETs’ responses on the end-of-semester evaluations suggest that they found their learning experiences meaningful, which addresses the second research question (Were these experiences beneficial for the ETs?). Since not all ETs engaged in the same experiences, I facilitated knowledge exchange during our training sessions, where ETs shared their experiences, asked questions, and learned from each other. Organizing tutor learning in this flexible way, where the training content is co-created by ETs, is beneficial as predetermined curricula may foster passivity (Cormier). Viewing ET learning as a rhizomatic process where ETs take an active part in co-creating knowledge encourages agency, discovery, and motivation. WC administrators should be open to embracing the “playful, exploratory and collaborative learning, whose outcome may be unpredictable and difficult to determine in advance, but whose whole may be greater than the sum of its parts'' (Schoenborn and Reel). Positive learning experiences for the ETs may have also contributed to the positive outcomes of our ET program. During the study period, students who utilized the embedded tutoring support earned higher grades than the students who did not attend ET sessions.

In response to the third research question (“How can the findings inform planning learning experiences for ETs?”), the findings support continuing the rhizomatic approach to ET learning and CCT’s practice of recursive reflection. Similar programs may benefit from identifying and mapping the elements that contribute to the development of tutor craft within their own contexts. To support this process, WC administrators can embed reflective prompts into tutor logs or reflexive activities, such as:

• How was this session a learning experience for you?

• What is something valuable you learned from a fellow ET this semester?

• What is something valuable you learned from your tutees this semester?

• What is something valuable you learned from the professor whose class you supported this semester?

• What insights from your courses and outside experiences informed your tutoring?

• How did different modalities (remote, asynchronous, in-person) shape your learning and you as a tutor?

• What did you discover about your own writing process?

• What kind of tutor have you become?

• What has shaped you as a tutor?

Alongside reflective writing, with the help of ETs, WC administrators can observe sessions, keep reflective journals, document authentic strategies used in their local contexts, and facilitate knowledge sharing among tutors. Together, these practices foster the kind of recursive, networked learning central to a rhizomatic model.

Conclusion

As course-embedded writing tutoring programs take diverse forms across college campuses, more research is needed into how tutors in these settings develop their craft, particularly since their work differs from that of traditional WC writing consultants, who tutor students individually. The study allowed me to capture ETs’ learning experiences and reactions to these experiences that would have gone unnoticed without revisiting the archived data. The rhizomatic model helps visualize ETs’ learning processes by capturing the nonhierarchical, interconnected assemblage of multiple human and non-human elements that shape tutor learning beyond formal training sessions.

The findings offer guidance for planning future learning opportunities, regardless of the constraints affecting WCs. Other WC administrators may adapt this model and adjust the nodes to suit their unique local contexts, considering factors such as program size, supervisor’s availability, budget constraints, and tutors’ strengths and interests. For instance, instead of requiring every ET to observe another ET’s session, which is a time- and resource-intensive task, supervisors might use a recorded session for collective discussion during training. Even with a reduced budget and frequency of training sessions (e.g., to bi-weekly or monthly), the rhizomatic approach may still be effective.

In any context, WC administrators may think of elements that contribute to ET learning as nodes, each serving as a potential starting point or a new connection. ETs should be encouraged to choose their areas of growth, build their own inventories of strategies, and chart their own learning paths. WC administrators should foster spaces for tutors to collaborate, share resources, and reflect on their learning. What matters most is maintaining the rhizomatic mindset: valuing non-linearity over hierarchy, promoting co-constructed knowledge, and embracing flexibility, connection, and the idea of ETs’ constant evolving or becoming. Like Hall, WC administrators and ETs should learn to embrace the “chaos” of the learning process and recognize the opportunities it creates for ET programs to uncover their own “forms of magic.”

Is our rhizomatic map the ultimate representation of ETs’ learning? Definitely not. Each semester reveals new layers of work, connections, and interpretations of what it means to become an ET. As ETs grow into their roles, they become unique versions of the idea of an ET, thus creating an ever-expanding network of tutors learning from a variety of experiences. As one ET reflected: “Each semester will be a new learning experience. You'll get new batches of students each semester, and it's a process of adjusting your sessions and style to what they need. It requires patience, but also you must trust in your abilities and your training as a tutor.”

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Dana Driscoll for providing feedback on an early draft of this paper, Dr. Curtis Porter for his feedback on a later draft, and Courtney James, a former ET with whom I worked on a previous version of this paper.

Works Cited

Aikens, Kristina. “Prioritizing Antiracism in Writing Tutor Education.” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/book s/dec1/Aikens.html.

Bleakney, Julia. “Ongoing Writing Tutor Education: Models and Practices.” How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bl eakney.html.

Bleakney, Julia, et al. “How Course-Embedded Consultants and Faculty Perceive the Benefits

of Course-Embedded Writing Consultant Programs.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 44, no. 7-8, 2020, pp. 10-18. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v44n7/b leakneyetal.pdf.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Sage, 2022.

Buck, Elisabeth H. "From CRLA to For-Credit Course: The New Director's Guide to Assessing Tutor Education." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Bu ck.html.

Caswell, Nicole, et al. The Working Lives of New Writing Center Directors. Utah State University Press, 2016.

Charteris, Jennifer, and Dianne Smardon. “Professional Learning as 'Diffractive' Practice: Rhizomatic Peer Coaching.” Reflective Practice, vol. 17, no. 5, 2016, pp. 544-556. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2016.1184 632

Colver, Mitchel, and Trevor Fry. “Evidence to Support Peer Tutoring Programs at the Undergraduate Level.” Journal of College Reading and Learning, vol. 46, no. 1, 2016, pp. 16-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2015.1075 446

Cormier, Dave. “Rhizomatic education: Community as Curriculum.” Innovate: Journal of Online Education, vol. 4, no. 5, 2008. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.c gi?article=1045&context=innovate.

Cruz, Rebecca, and Katie Galahan. “The Role of the Tutor in Developing and Facilitating Writing Center Workshops." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Cr ewsGarahan.html.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

DeLoach, Scott, et al. "Locating the Center: Exploring the Roles of In-Class Tutors in First Year Composition Classrooms." Praxis, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014. https://www.praxisuwc.com/deloachet-al-121.

Devet, Bonnie. "The Writing Center and Transfer of Learning: A Primer for Directors." The Writing Center Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, 2015, pp. 119-

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

151. https://doi.org/10.7771/28329414.1801

Dippold, Doris, et.al. “International Students’ Linguistic Transitions into Disciplinary Studies: A Rhizomatic Perspective.” Higher Education, vol. 83, 2022, pp. 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00677-9.

Driscoll, Dana, and Sarah Harcourt. "Training vs. Learning: Transfer of Learning in a Peer Tutoring Course and Beyond.” WLN: The Writing Lab Newsletter, vol. 36, no. 7-8, 2012, pp. 1-6. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v36/36.7 -8.pdf.

Dvorak, Kevin, et al. "Getting the Writing Center into FYC Classrooms." Academic Exchange Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4, 2012, pp. 113-119. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.c gi?article=1078&context=shss_facarticles.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin, 2017. Funt, Alex, and Sarah Esposito. “Video Recording in the Writing Center.” WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 43, no. 5, 2019, pp. 2-10. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v43n5/f unt-esposito.pdf.

Gentile, Francesca. "When Center Catches in the Classroom (and Classroom in the Center): The First-Year Writing Tutorial and the Writing Program." Praxis, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014. https://www.praxisuwc.com/gentile-121.

Grellier, Jane. “First-Year Student Aspirations: A Multinodal Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 27, no. 4, 2014, pp. 527-545. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.7753 76.

Hall, Gaelen. “Forms of Magic: Navigating Chaos as a Tutor in Training. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 45, np. 5-6, 2021, pp. 2427.

https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v45n5/h all.pdf.

Haring-Smith, Tori. “Changing students' attitudes: Writing fellow programs.” Writing Across the Curriculum: A guide to Developing Programs, edited by Susan McLeod and Margot Soven, 1st ed., Sage, 2000, pp. 123-131. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/mcleo d_soven/mcleod_soven.pdf

Hordvik, Mats, “Negotiating the complexity of teaching: a rhizomatic consideration of pre-service teachers’ school placement experiences.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, vol. 24, no. 5, 2019, 447–462.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1623 189

Kim, Miso, and Suresh Canagarajah, S. “Student Artifacts as Language Learning Materials: A New Materialist Analysis of South Korean Job Seekers’ Student Generated Materials Use.” The Modern Language Journal, vol. 105, no. 1, 2021, pp. 21–38.

https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12686.

MacDonald, Ross. "Group Tutoring Techniques: From Research to Practice." Journal of Developmental Education, vol.17, no. 2, 1993, pp. 2-18. http://www.jstor.com/stable/42774600.

Masaki, Fujisawa, et al. “Cloning and Characterization of a Novel Gene That Encodes (S)-βBisabolene Synthase from Ginger, Zingiber Officinale.” Planta, vol. 232, 2010, pp. 121-130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-010-1137-6

Mendoza, Dayra Fallad, and Elizabeth Kerl. “Student Perceived Benefits of Embedded Online Peer Tutors.” Learning Assistance Review, vol. 26, no. 1, 2021, pp. 53–73. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1317160.p df

Miller, Laura. “Can we Change Their Minds? Investigating an Embedded Tutor’s Influence on Students’ Mindsets and Writing.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 38, no. 1/2, 2020, pp. 103–130.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27031265.

Parmiter, Tara, and William Morgan. “Traction and Troublesome Learning: A Praxis of Stuck Places for Course-Embedded Tutoring.” Praxis, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014. https://www.praxisuwc.com/parmitermorgan-121.

Pierce, Danielle, and Aolani Robinson. “Integrating and Evaluating Twine as a Mode for Training Course Embedded Consultants in the Writing Center. The Peer Review Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, 2021. https://thepeerreviewiwca.org/issues/issue-5-1/integrating-andevaluating-twine-as-a-mode-for-trainingcourse-embedded-consultants-in-the-writingcenter/.

Pigliacelli, Mary. "Practitioner Action Research on Writing Center Tutor Education: Critical Discourse Analysis of Reflections on Videorecorded Sessions." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/dec1/ Pigliacelli.html.

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

Ristow, Ben, and Hannah Dickinson. "(Re)Shapping a Curriculum-Based Tutor Preparation Seminar: A Course Design Proposal." Praxis, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014. https://www.praxisuwc.com/ristowdickinson.

Reimers, Ute. “Writing Fellows as Support for Digital Introductory Lectures: Advantages and Challenges.” Journal of Academic Writing, vol. 12, no. 1, 2022, pp. 86-91. https://doi.org/10.18552/joaw.v12i1.821

Ryan, Holly. "First Things First: An Introduction to Administration at a New Directors' Retreat." How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection, edited by Karen G. Johnson and Ted Roggenbuck, 2019, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/dec1/ Ryan.html.

Samson, Sean, et al. “ ‘I am everywhere all at once’: Pipelines, Rhizomes and Research Writing. Higher Education, vol. 83, no. 6, 2022, pp. 12071223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-02100738-z.

Scanlon, Dylan, et. al. "A Rhizomatic Exploration of a Professional Development Non-Linear Approach to Learning and Teaching: Two Teachers’ Learning Journeys in 'Becoming Different'." Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 115, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103730

Schoenborn, Priska, and Terri Rees. “A Module Designed with Chaos and Complexity in Mind.” Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences, vol. 12, no. 1, 2013, pp. 14-26. https://doi.org/10.11120/ital.2013.00007.

Sherman, Brandon, and Annela Teemant. “Unravelling Effective Professional Development: a Rhizomatic Inquiry into Coaching and the Active Ingredients of Teacher Learning.” Professional Development in Education, vol. 47, no. 2-3, 2021, pp. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1825 511

Spigelman, Candace, and Laurie Grobman. On Location: Theory and Practice in Classroom-Based Writing Tutoring. Utah State University Press, 2005. Strom, Kathryn, and Adrian Martin. Becoming-Teacher: A Rhizomatic Look at First-Year Teaching. Sense Publishers, 2017.

Tetreault, Molly, et al. “Claiming an Education: Using Archival Research to Build a Community of Practice.” Praxis, vol. 16, no. 3, 2019. https://www.praxisuwc.com/163-wilde-et-

al?rq=%E2%80%9CClaiming%20an%20Educ ation%3A%20Using%20Archival%20Researc h%20to%20Build%20a%20Community%20of %20Practice.

Titus, Megan, et al. “Dialoging a Successful Pedagogy for Embedded Tutors.” Praxis, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014. https://www.praxisuwc.com/titus-et-al121.

Trimbur, John. “Peer Tutoring: A Contradiction in Terms?” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 7, no. 2, 1987. pp. 21-28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43441837.

Webster, Kelly, and Jake Hansen. "Vast potential, uneven results: Unraveling the factors that influence course-embedded tutoring success." Praxis, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014. https://www.praxisuwc.com/webster-hansen121.

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

UNTAPPED POTENTIALS: LEVERAGING

DISCIPLINARY

EXPERTISE FOR GRADUATE WRITING CONSULTANT EDUCATION

Vicki R. Kennell Purdue University vkennell@purdue.edu

Abstract

Ashley Garla Purdue University ashley.garla1@gmail.com

Reflecting on the experiences of two graduate students from speechlanguage pathology (SLP) who became generalist writing consultants, this article examines the intersections between the academic homes of generalist graduate consultants and their writing center education and work and analyzes what these intersections tell us about consultant education. We briefly introduce SLP and identify the specific ways that both fields address writing. We then explore how the disciplinary intersections enhance or hinder the work that graduate students do in either field. Based on this foundation, we propose a four-step process for educating graduate consultants that promotes an awareness of how similarities enhance work in either field, how differences can hinder the work, and how bidirectional transference between fields can benefit graduate students as both consultants and as academics in their home discipline. Ultimately, this paper highlights the untapped potential of the theory and pedagogy of consultants’ home disciplines for effective generalist consultant education.

Introduction

A common topic that arises in conversations among graduate communications scholars is the importance of specialist feedback for graduate writers (e.g., some writers prefer content-knowledgeable consultants; Phillips 163). From a writing center perspective, such conversations presuppose a certain context having the resources for a graduate-only writing center a situation in which many writing centers do not find themselves. For most writing centers, graduate writers, if allowed at all, must be folded into the customary peer-tutoring model, where consultants work with writers from all disciplines, but the consulting staff may not possess that disciplinary variety. The need to work with writers across disciplines has led to writing center discussions similar to graduate communications scholars’ conversations about specialist feedback, but with a tendency to favor generalist options. In 1998, Kristin Walker proposed genre theory as a way to fashion a middle ground between generalist and specialist consulting. Layne Gordon revived this theme in 2014, the same year that Sue Dinitz and Susanmarie Harrington’s research clarified the role (and value) of disciplinary expertise in consultations. In 2017, Tomoyo Okuda explored the varying usefulness of generalist strategies, noting a need for improved training of generalist consultants. More recently, in 2021, several chapters of Megan Swihart

Genevieve Gray Purdue University genevieve.gray505@gmail.com

Jewell and Joseph Cheatle’s book Redefining Roles explored issues related to hiring graduate consultants from across campus, including discussions of how to train them, but also raising once again the generalist versus specialist dichotomy.

Centering the generalist-specialist conversation around what is best for writers excludes issues that affect writing centers generally or consultants specifically. Scholars have noted that the logistics of hiring enough consultants for precise disciplinary matches are problematic for writing centers (Dinitz and Harrington 95). Even where specialist matches are possible, assuming that consultants arrive at the writing center with existing expertise in disciplinary expectations around writing is problematic; even graduate consultants (GTAs) may still be in the process of becoming enculturated into their field of study and may not possess a fully formed or confident expertise. Focusing on content specialization also does not take into account graduate students’ wide-ranging concerns around writing. Graduate writers tend to be savvy about developing feedback networks to address that range. For instance, they may reserve their advisor’s time for dissertations and seek consultant help with more general concerns such as funding applications or sentence-level issues (Mannon). Generalist consultants can also offer value as fellow graduate students; they are familiar with academic research and project management and able to commiserate over the more emotional aspects of writing such as lack of confidence and a tendency to procrastinate. The shared experiences of graduate school contribute to generalist graduate consultants being well positioned to offer valuable writing support regardless of disciplinary match.

Focusing the generalist-specialist conversation on what each type of consultant offers also leaves open the question of what each might need from their writing center education and professional development experiences and, in particular, what graduate consultants might need. In 2019, Katrina Bell noted that very little advice about preparing students to work as consultants specifically addresses the preparation of graduate consultants. Consultant education often focuses on types of writers (e.g., anxious writers, multilingual writers), types of documents (e.g., literature analyses, lab

reports), and types of situations (e.g., unresponsive or antagonistic writers) in addition to covering session protocols and the writing process (as an example, see Ryan and Zimmerelli). Such a broad range of material related to consulting with writers can be useful, regardless of whether a consultant is an undergraduate or graduate or is hired as a specialist or generalist. However, just as the generalist-specialist discussion tends to ignore consultants’ needs, so material on educating consultants tends to ignore graduate consultants’ need to successfully integrate work in their home disciplines with work in the writing center. Discussions of home disciplines often focus on the outcomes for writers when consultants share their disciplinary background (e.g., benefits of shared background versus too-directive tutoring; Dinitz and Harrington 89-90). In this article, we focus on what has often been left out of the generalist-specialist and consultant education conversations as it relates to graduate consultants themselves: the specific intersections between the academic homes of generalist graduate consultants and their writing center training and work, and, in particular, what these intersections might tell us about consultant education.1

In recent years, the Purdue OWL has experimented with hiring and educating graduate students from outside English to work as generalist writing consultants. During the 2023-24 academic year, we hired four graduate consultants from outside of English: a doctoral student from math education, a doctoral student from counseling psychology, and two master’s students from speech-language pathology (SLP). Two factors contributed to the specific formation of this first cohort. At Purdue, master’s students tend to be less well funded than doctoral students, making them a common source of applicants. Also, while departments may allow doctoral students to work outside the department when departmental funding has contracted, they generally prefer to have students take assistantships in the department when possible. In fact, we lost one of our doctoral consultants during the fall semester when funding tied to her field of study became available. Our experiment filled the consultants’ need for funding and the OWL’s need to expand the potential pool of GTA applicants due to institutional shifts that particularly affected the humanities. For this first cohort from outside English, new GTA education was only slightly changed from previous years.

As the cohort discussed their experiences of being trained as generalist writing consultants, it became obvious that their home disciplines allowed them to bring expertise to their role that had not been considered when planning the training curriculum and,

as a result, was not leveraged to develop them as confident, skilled consultants. In order to illustrate the effects of the intersections between the two forms of expertise, we will focus our discussion on SLP, the home discipline of co-authors Ashley and Genevieve, two of the graduate hires at that time.2 Their training as writing consultants, and hence much of our discussion about disciplinary intersections, was overseen by Vicki, an associate director in the writing center and the other author of this article.

When we first began this project, Ashley and Genevieve were graduate students in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences who were training to be SLPs. They sought employment at the writing center during their first year in their program because of interest in and experience with writing. The vast majority of the writers and documents they worked with fell outside their academic field, so they operated as generalist consultants. However, they also found that their specialist SLP training provided a unique perspective that supported their work with writers. In this paper, we outline the ways in which writing center work and SLP work intersect, beginning with the specific way that both fields address writing and progressing to broader interactions between the fields. In particular, we explore how disciplinary intersections can enhance or hinder the work that graduate students do in either field. We will end by presenting recommendations for writing center administrators seeking to train graduate consultants from academic fields outside of English.

First, a note about terminology. Looking at the intersections of two fields means that we must introduce multiple characters who occupy sometimes-similar roles. For clarity, we will use the following terms to describe our identities as well as those of the people with whom we work: consultant for our role in the writing center; clinician for our role in providing speech therapy services; writers for those we work with in the writing center; and patients for those we work with in the SLP clinic. In discussions pertaining to both consultants and clinicians, we will refer to this collective group as practitioners; and in discussions pertaining to both writers and patients, we will refer to this collective group as clients

SLP and Written Language

To those outside the field, SLPs are commonly known as the people who help children with their /r/ and /s/ sounds; however, speech is only one aspect of what SLPs are trained to treat. More broadly, SLPs treat language disorders, which range from children

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com

struggling to learn and implement the rules of grammar (e.g., omitting -ed for past-tense verbs) to adults with acquired brain injuries relearning sentence structure and parts of speech. Especially pertinent to our discussion, SLPs also address patients’ writing. The reciprocal relationship between oral and written language has been well-documented, building the basis for the SLP’s scope of practice to include both modes of communication (Summy and Farquharson). Children with developmental communication disorders and adults with acquired language disorders often demonstrate difficulty in some aspects of written language as well as spoken language. SLPs therefore diagnose disorders of reading and writing, including dyslexia; establish collaborative relationships with educators to foster students’ written language; and work to prevent academic difficulties that result from difficulties with written language (“Written Language Disorders”). For both written and spoken language, SLPs aim to empower patients to effectively communicate their needs and wants regardless of modality.

Intersections between SLP and Writing Centers

While the overlap between the SLP and writing center fields is most salient in the way that both disciplines deal with written language, intersections extend beyond this explicitly common ground. For any given consultant in our case those from SLP three potential intersections may occur between their home discipline and the writing center:

1. both fields may approach an aspect of working with writers in a similar manner,

2. both fields may differ (and likely conflict), or 3. the work in one of the fields may unexpectedly transfer to and enhance the other.

When both fields have a similar approach, the new consultant may experience increased confidence in consulting with writers, comfort with writing center work, and an easy transition from clinician (in the case of SLP) to consultant. When fields conflict, it can create unease and decrease confidence in working with writers. Differences do not necessarily have to mean conflict, however. When consultants either bring something from their home discipline to their writing center work or carry something from the writing center to their home discipline, the field on the receiving end benefits from an infusion of new ideas, methods, or potential areas for research. Exploring and leveraging these similarities and opportunities for transfer between fields during training and beyond can help facilitate a more effective and time-efficient transition from clinician to consultant.

Similarities

Several similarities between SLP work and writing center work allowed us to transition fairly seamlessly from one to the other. Both fields value professional development of their staff, offering training that combines theories and pedagogies of the field with supervised client interaction. For instance, SLP students gain hands-on practice in education and healthcare settings where they assess and treat patients and apply evidence-based strategies to real-world scenarios, while new writing consultants observe and co-tutor live sessions. In both fields, training requires openness to feedback and emphasizes personal reflection. Our training also involved being observed during a session by a more senior practitioner (writing center administrator or clinical supervisor) and receiving feedback on strengths and areas for improvement. Additionally, reflecting on sessions to process them and think through next steps was an essential element of developing our ability to self-assess our effectiveness as we continued to engage with clients in both fields. The fields also share similar approaches to writing and to supporting writers. Both understand writing as a process from pre-writing through revising, although the terminology varies. For instance, while SLP distinguishes between “process” (e.g., developing ideas, planning, organizing) and “product” (e.g., written form, syntax, effectiveness of intended communication) (“Written Language Disorders”), the writing center views addressing grammar as part of the writing process. In addition, both fields share methods of supporting writers, such as scaffolding to help clients learn to recognize their own errors (patients) or areas for revision (writers) without our input. Clinicians might help a patient with difficulty swallowing to better understand the link between their actions and their body’s response through biofeedback methods such as visualizations of muscle activation (Archer et al. 282). Consultants might move a writer from depending on consultant input for correctly formatting citations to referencing style guides independently. As with approaches to writing, although the strategy may be similar across fields, the terminology varies. While writing centers commonly talk about scaffolding (e.g., I do, we do, you do), SLP divides that into specific strategies like modeling (e.g., demonstrating the correct production of a speech sound) and cueing (e.g., reminding the patient to pay attention to their tongue when attempting the sound). In both cases, however, the strategies are geared toward helping clients acquire, practice, and gain independence with their ability to communicate.

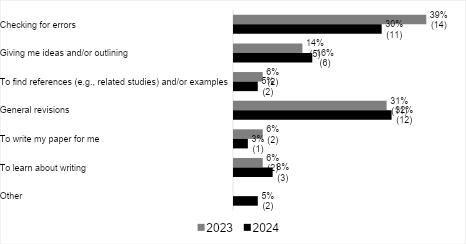

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal • Vol. 22, No. 3 (2025) www.praxisuwc.com