Indigenous Issue

Vol. CXLVI, No. 11

21 Sussex Avenue, Suite 306 Toronto, ON M5S 1J6 (416) 946-7600

thevarsity.ca thevarsitynewspaper @TheVarsity thevarsitypublications the.varsity The Varsity

Medha Surajpal editor@thevarsity.ca

Editor-in-Chief

Chloe Weston creative@thevarsity.ca

Creative Director

Sophie Esther Ramsey managingexternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, External

Ozair Chaudhry managinginternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, Internal

Jake Takeuchi online@thevarsity.ca

Managing Online Editor

Nora Zolfaghari copy@thevarsity.ca

Senior Copy Editor

Callie Zhang deputysce@thevarsity.ca

Deputy Senior Copy Editor

Ella MacCormack news@thevarsity.ca

News Editor

Junia Alsinawi deputynews@thevarsity.ca

Deputy News Editor

Emma Dobrovnik assistantnews@thevarsity.ca

Assistant News Editor

Ahmed Hawamdeh opinion@thevarsity.ca

Opinion Editor

Medha Barath biz@thevarsity.ca

Business & Labour Editor

Shontia Sanders features@thevarsity.ca

Features Editor

Sofia Moniz arts@thevarsity.ca

Arts & Culture Editor

Ridhi Balani science@thevarsity.ca

Science Editor

Caroline Ho sports@thevarsity.ca

Sports Editor

Aksaamai Ormonbekova design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Brennan Karunaratne design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Erika Ozols photos@thevarsity.ca

Photo Editor

Simona Agostino illustration@thevarsity.ca

Illustration Editor

Jennifer Song video@thevarsity.ca

Short-Form Video Editor

Emily Shen emilyshen@thevarsity.ca

Front

Sataphon Obra sataphon.ob@gmail.com Back End

Arunveer Sidhu utm@thevarsity.ca UTM

Vacant utsc@thevarsity.ca

UTSC Bureau Chief

Molinaro grad@thevarsity.ca

Vacant publiceditor@thevarsity.ca

The Varsity acknowledges that our office is built on the traditional territory of several First Nations, including the Huron-Wendat, the Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit. Journalists have historically harmed Indigenous communities by overlooking their stories, contributing to stereotypes, and telling their stories without their input. Therefore, we make this acknowledgement as a starting point for our responsibility to tell those stories more accurately, critically, and in accordance with the wishes of Indigenous Peoples.

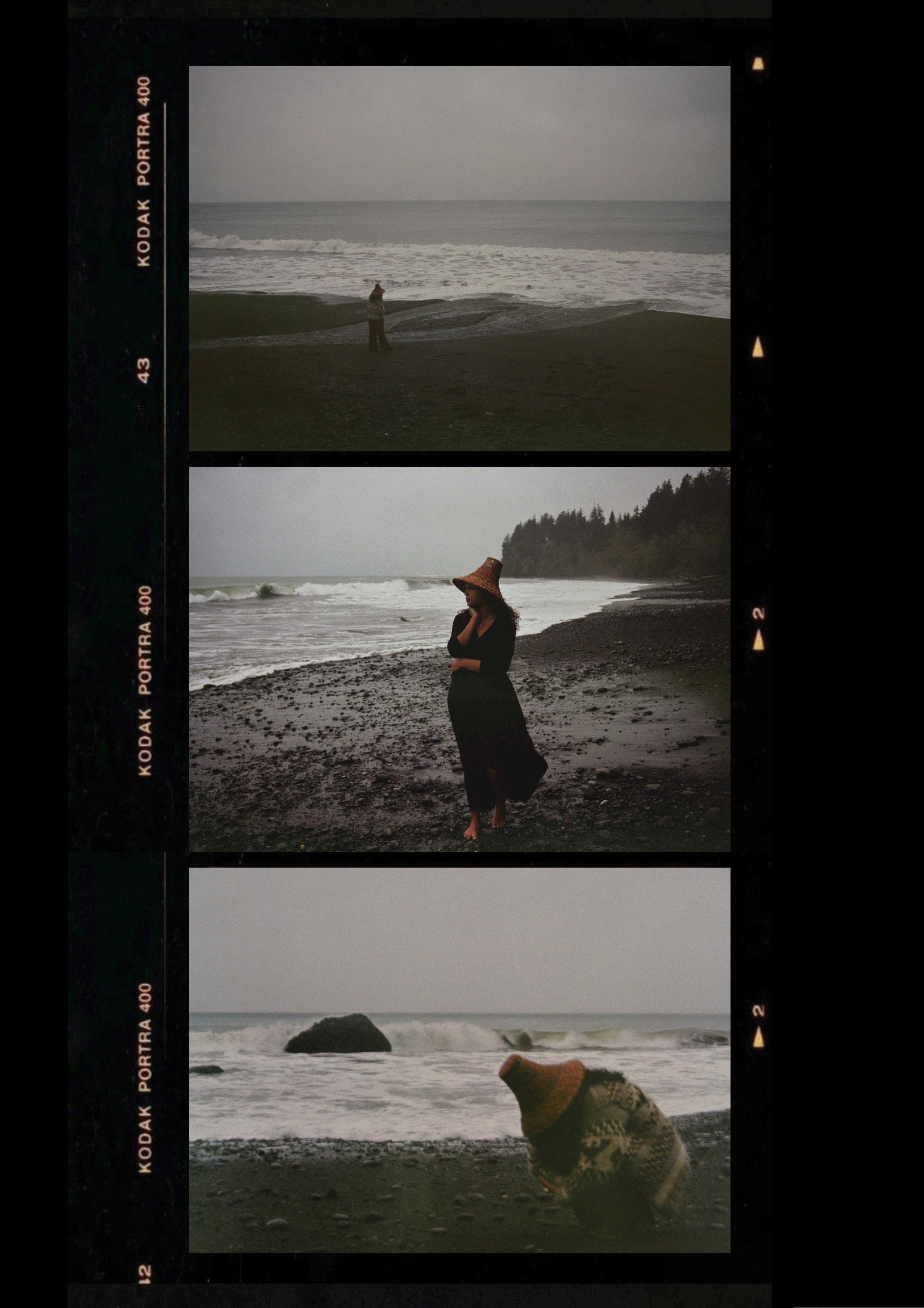

My relationality to the land is accumulated through my lived experiences as a Two-Spirit Anishinaabekwe, realities of mobilization to an urban space, and my encounters with spirituality.

Over the past year, I have spent much thought about how I exist on nimaamaa-aki, Mother Earth. I had the opportunity this summer to participate in SOC437H5 Mnidoo Mnising Indigenous Field School led by Paul Pritchard and Dani Kwan-Lafond this summer. This course provided access to closed-ceremonies, cultural activities, and land-based education that I would not have access to here in Tkaronto.

A prominent theme amongst my educational journey during this trip was my reconnection with water. I spent time in the water ceremony, swimming, and releasing tears. Having spent time learning from water’s teachings, I felt this connection deepen even further during our time at Wikwemikong’s Annual Cultural Festival. I had the opportunity to dance in my jingle dress during the Jingle Dress Special Honouring Nibi.

My piece, titled “nibi bimijiwaninig” or “ᓰᐱ

”, focuses on the movement of water bodies and the sacredness that water carriers hold. Female-bodied individuals are described as water carriers, as our ability to give life and hold specific knowledge in

relation to the spirit of water remains distinct. Water, or nibi, holds spiritual and physical healing properties. My learning journey on the land has been guided by witnessing the healing power of water, to honour water. It is more important than ever that I encourage my Indigenous peers to honour waterways and reciprocal relations to the land. Referring back to traditional teachings and passed-on knowledge of reciprocity has been a grounding practice in my time at university. Honouring the land offers clarity in my positionality within the intricacies of my academic experience. Holding true to my relationship with the land guides me in how I move, learn, and grow within my surroundings.

Oladokun, Simona Berardocco,

Cover: Illustration courtesy of MJ Singleton

PhD study participants are wanted to better understand the experiences of women who return to postsecondary education later in life. If you identify as a woman between the age of 55 and 70 who is currently attending or have attended, in the past two years, a postsecondary institution in Ontario you may qualify to participate in this study. Participants would consent to an interview conducted over Zoom.

Please contact Ursula Cafaro at ucafaro@laurentian.ca for more information.

This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Board at Laurentian University, REB # 6021821

“Reminded me of home”: In conversation with Indigenous House

Junia Alsinawi Deputy News Editor

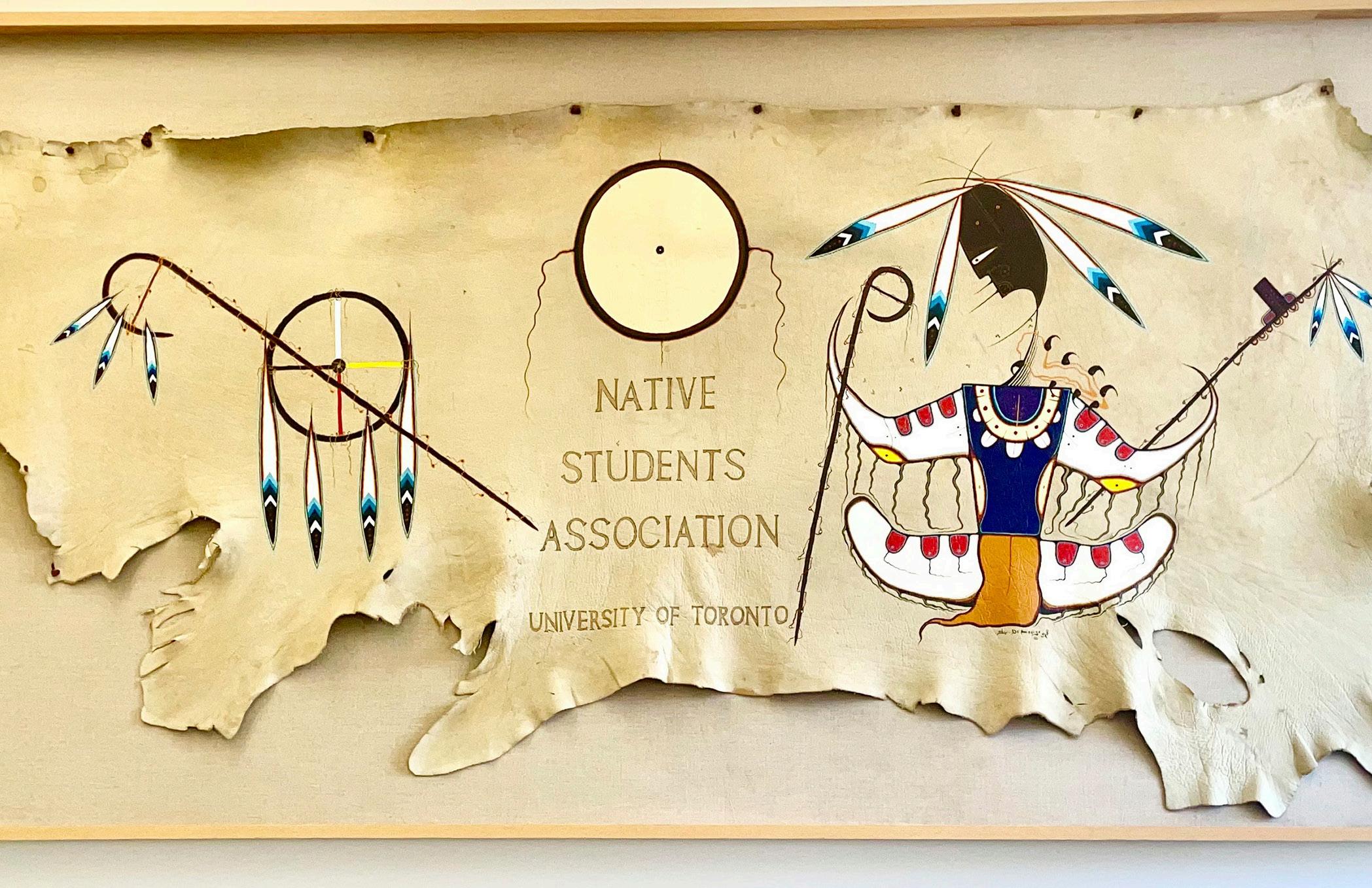

The unassuming red-brick building sitting on the corner of Bancroft and Spadina gives no hint of the colourful art adorning the interior of First Nations House.

Located in the North Borden building, this hub of Indigenous student life — often referred to as Indigenous House — was founded by Diane Longboat in 1992. Today, it has grown to a small but robust community, staffed by Traditional Teachers and coordinators for programming, peer mentorship, wellness, and career education, among others.

The Varsity sat down with Jenny Blackbird, First Nations House Resource Center and Programs Coordinator, to discuss the work of Indigenous House and the joys of building a strong Indigenous community on campus.

The Varsity: Tell me about yourself, your role here — what does a typical day for you look like?

Jenny Blackbird: I’m the Resource Center and Programs Coordinator, First Nations House,

JB: With the library, I can support them by showing them different materials. I want to try and have books mostly written by Indigenous people. There are some older books that are non Indigenous, but I’ve been trying to weed those out, and then bring in contemporary voices as well.

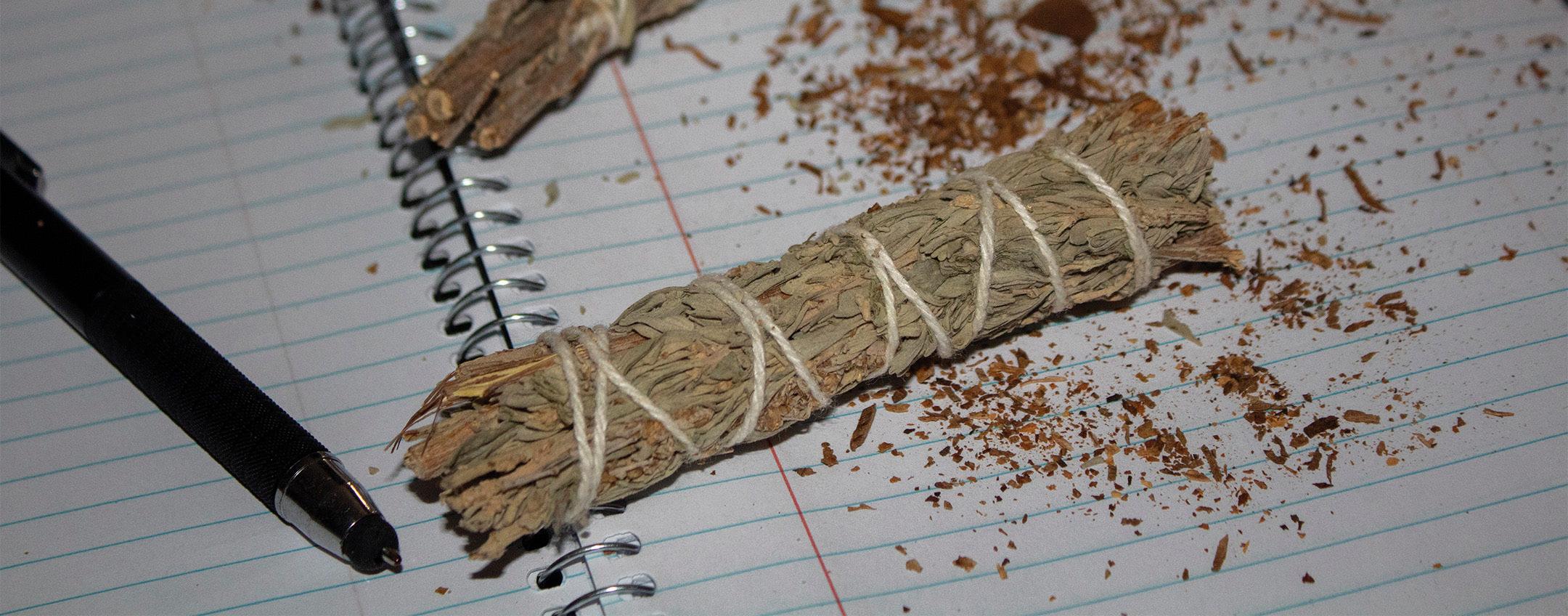

And then I also take care of the Teaching Lodge and the medicine table. So we have the sage, sweet grass, cedar and tobacco, and I make sure that it’s all on the medicine table we have at the lobby so that people can come and take some.

And then, just listening to students, hearing what fun things they’re doing and also, if they come in and they’re having a hard day, they can chat with us.

We also have a Fire Keeper training program, so I organize with them when they come and help us with the full moon fires.

TV: Have you noticed the Indigenous community at U of T change during your time here?

JB: I mean, it’s very different, because many students I’ve met recently didn’t know about First Nations House until maybe, like, their second or third year, and then they walk in and go, ‘I didn’t

Indigenous Student Services. My late father’s side of the family is from Kehewin Cree Nation in Alberta, and my mom’s side of the family is from Finland. I grew up in Toronto, and I’ve been working at First Nations House since November 2021.

I spend a lot of time planning and organizing. We have full moon fires every month, so I have to ask student Fire Keepers if they can help, if they can come learn. Then we have Fire Keepers that already know the ropes, so I just have to arrange who’s going to be where.

And sometimes I go speak to classes and do presentations and talk about different Indigenous topics. I’ll tell them about the Indian Act, or the restrictions, or the things that Indigenous people still face, like the racism, and sometimes people are like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know this.’ They’re shocked.

It’s nice to actually have a chance to meet with people and also remind them that they should continue to listen to various Indigenous voices. So it’s good when people are curious, and they come into the library, they come to First Nations House, they come to the teaching circles we have.

It’s really nice that we can engage with Indigenous students and support them, as well as some non-Indigenous staff or students or faculty.

TV: In what ways do you support students? What does that look like? What services do you provide?

know it was here.’ And then we have time to catch up.

I see that in the last couple of years, because COVID has really isolated us and kind of separated us, it took a while for things to really come back and be very active. There were a few students who were really, really key to creating community here, and one of them is Devo Moosewaypayo, who won a President’s Award.

She was part of the Indigenous Student Association, and she created events like biweekly lunches. She and her fellow students were really active, like Alicia Corbiere, who did Anishinaabemowin lunch.

So they’ve been coming back very slowly; in the last week of August, students were coming in already. So it’s nice because I’m hoping that people are letting each other know the good things that are here, and it feels good when everybody’s hanging out in the lounge.

TV: It seems like Indigenous House is very unique in the fact that it seems almost just as much driven by students as by staff. Can you speak to that relationship and the dynamics?

JB: Well, from what I understand, First Nations House really was here for the original Native Students Association. And so they would say, “Hey, I want to learn how to build a sweat lodge,” or

Check out the themed content in this Issue by looking for this bookmark!

“I want to have this kind of event,” and First Nations House would support in any way they could. We’re really here for the students, and if they tell us they want to do a certain event, we can see if we have the resources, and if we have the people who can come facilitate, we set it up for them.

TV: Are there any struggles that Indigenous House faces, or anything that you want to change or wish would change?

JB: Yeah, I think, obviously, more space, but that is coming at some point. And hopefully that more Indigenous students will come and hopefully feel supported, and let us know what their needs are.

A lot of the things we do here are very open. It’s hard to not be pan-Indigenous in some ways. We have to be willing to be open and learn from each other. And then if there is a specific ceremony that a student or a group wants to conduct or host, they bring their elder.

If a student is coming here and they’re disconnected from their community, I always encourage them to just come anyway, because sometimes people might feel like they don’t belong. If you are an Indigenous student, you’re First Nations, Inuit, or Métis, regardless of your Indian status card. We don’t ask for that. We want to make sure that people can come and they can just be themselves.

It’s lovely when I get to sit with other Indigenous people and just spend time together, you know, create community. And I think the biggest compliment I ever got from a student was when I was in my office talking to a co-worker, and we were laughing really hard. And when I came out of my office, the student looked at me and said, “That was you? Your laughter reminded me of being back home,” he goes, “You have a big auntie laugh.” I was like, “Mission accomplished.”

TV: Have you felt like you’ve changed in any way since working here? Has it changed your

perspective on your Indigenous identity or the Indigenous community in any way?

JB: I’ve always grown up knowing who I am, and so that’s just the way it is for so many of us — we may not have grown up in our community, but we know who our family is, and they know who we are. And I think it’s just, you know, never letting anyone put you in a position where you feel awkward. You know, I’ve had people be like, “Oh, you’re, you’re half white,” because some people think you’re lesser than.

Somebody shouldn’t make you feel bad for having a mixed identity. I find I connect with a lot of different students who have a different non-Indigenous parent, or heritage. So it’s nice to connect with them and then hear what their experiences are like, and just reassure people that they’re not lesser of a person.

You know, because the Indian Act really messed up so much. You know, it’s like the government determining who’s Indigenous and who’s not Indigenous.

I’m not gonna ask you for your ID card. We look at them as a joke. You know, when you look at your driver’s license, you’re like, “Oh, I hate this picture,” and you show it to your friend. Sometimes we’ll do that with our status cards. We’re like, “Oh god, look at this horrible picture.”

TV : What is your hope for the future of Indigenous House?

JB : That we keep going, that we keep having the same awesome staff and the space, the capacity, to assist students and that we have continuous relationships with divisions of student life and with Melanie Woodin — establishing a new relationship with her. I would personally just love to see it keep going and keep thriving.

How U of T has been “answering the call” of truth and reconciliation

Matthew Molinaro Graduate Burreau Chief

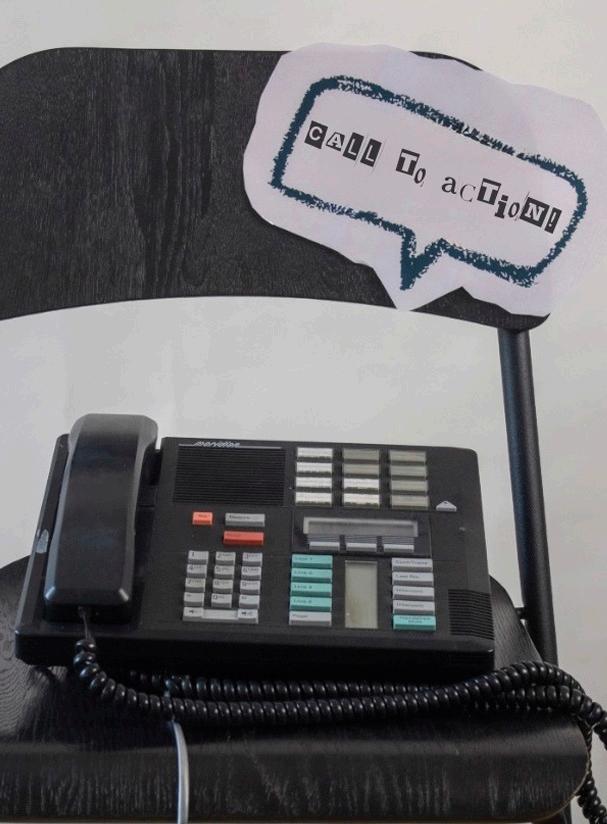

Ten years ago, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its 94 Calls to Action as part of the federal government’s commitment to rebuilding its relationship with Indigenous peoples. The TRC emerged from the 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement, which responded to Canada’s genocidal residential school system.

These Calls to Action span all sectors of public life — from justice to education to health — and aim to address the intergenerational impacts of residential schools across institutions. As of 2025, reports have indicated that only 15 of the 94 calls have been fully implemented.

Several of the TRC’s calls directly relate to post-secondary institutions. Call 11 urges the federal government to provide universities with the resources needed to enroll more Indigenous students. Call 16 calls for courses and programs in Indigenous languages. Call 62 focuses on integrating Indigenous education into teachers’ training, and Call 65 pushes for funding to advance research on reconciliation.

“Answering the Call”

In 2017, U of T students, staff, faculty, and Elders published “Answering the Call: Wecheehetowin Final Report of the Steering Committee for the University of Toronto.” The report outlines dozens of actionable initiatives under six themes: Indigenous Spaces; Indigenous Faculty and Staff; Indigenous Curriculum; Indigenous Research Ethics and Community Relationships; Indigenous Students and Indigenous Co-Curricular Education; and Institutional Leadership/Implementation.

One of the lead advisors was the late Lee Maracle, a Stó:lō Nation writer, teacher, activist, and member of U of T’s Elders Circle. That same year, she helped organize the university’s first pow wow with Indigenous studies students.

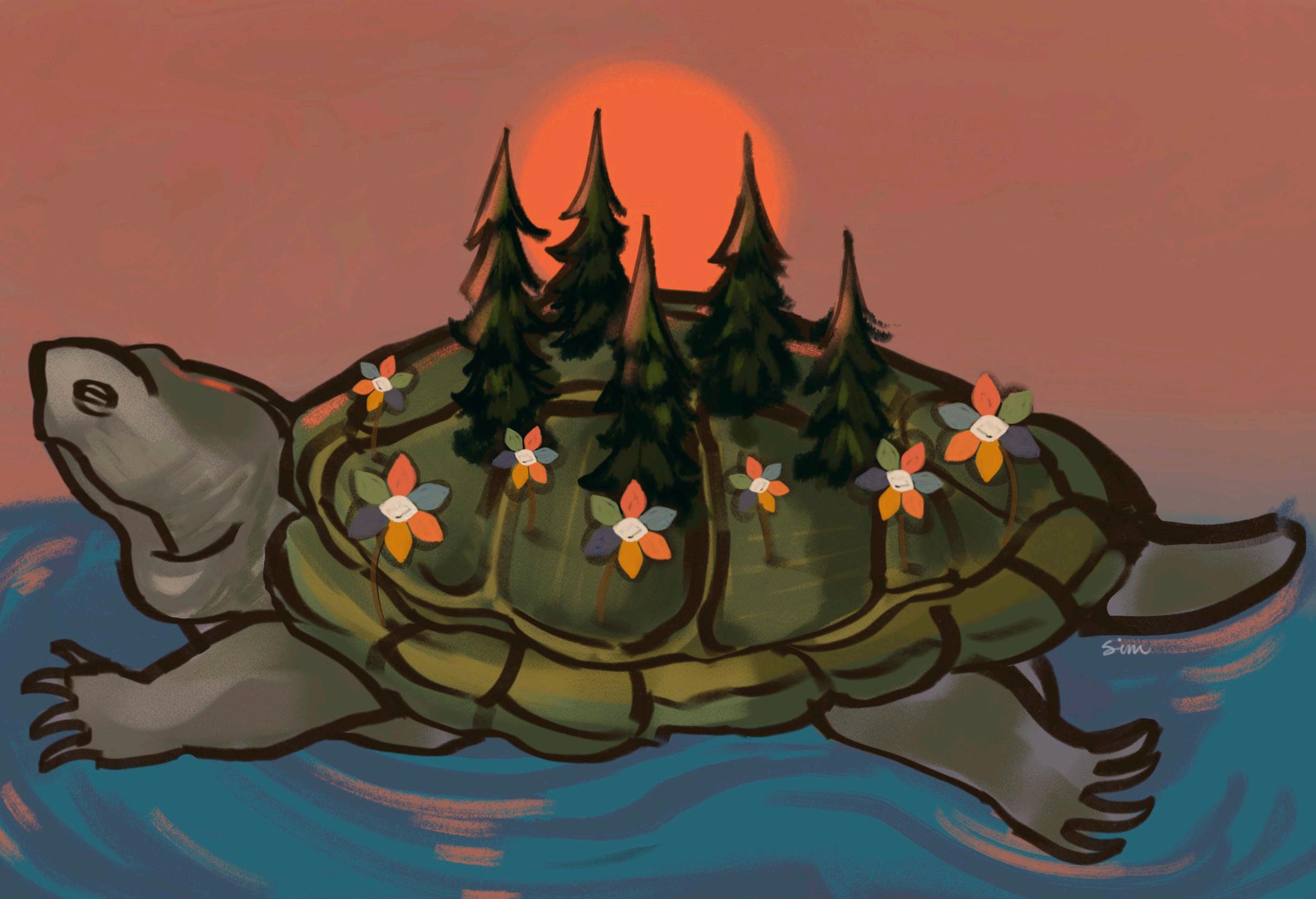

The report’s preface acknowledges U of T’s long history as a site of oppression for Indigenous peoples, noting that the university educated generations of leaders, policymakers, teachers, and bureaucrats who expanded the residential schools system. It situates the university within a broader settler culture on Turtle Island and commits U of T to the greater inclusion of Indigenous people, perspectives, and worldviews into academic and campus life.

The 34 U of T-specific Calls to Action include establishing an Indigenous Advisory Council — similar to those at western Canadian universities — hiring more Indigenous faculty and staff, creating dedicated Indigenous spaces across all three campuses, and regularly assessing the university’s progress on these goals.

Since 2019, U of T’s annual progress reports have outlined efforts to implement these commitments. They highlight new hires of Indigenous faculty and staff, spotlight initiatives and community events, faculty-specific accountability measures, and track the development of dedicated Indigenous spaces such as Ziibiing, a gathering place to reflect on Indigenous culture.

Across the reports, the Indigenous students, staff, faculty, and librarians have identified a common challenge: there are too few Indigenous faculty members to meet the demand for their involvement in projects and initiatives, placing an outsized burden on the limited number who are already at the institution. Other challenges include insufficient sustainable funding for long-term

initiatives, limited administrative infrastructure to support Indigenous-focused projects, and a lack of Indigenous representation across numerous faculties and departments.

Case study of Jackman Law Cameron Smith, co-president of the Indigenous Law Students Association (ILSA), wrote to The Varsity about how Indigenous students at Jackman Law have experienced these multi-year shifts at U of T.

In light of potential scale-backs of diversity initiatives from Canadian law firms, Smith reflected on Jackman’s commitment to the various aspects of Indigenous students’ experience in the faculty. These include the development of a dedicated space for ILSA, the close relationship between students and the Indigenous Initiatives Office, and land-based education open to U of T, Osgoode Hall Law School, Toronto Metropolitan University, and Queen’s University.

TRC Call 28 urges law schools to require that all students take a course on Indigenous peoples and the law. Smith highlighted the leadership of Professor John Borrows — an Anishinaabe/ Ojibway legal scholar and Loveland Chair in Indigenous Law — who teaches the mandatory first-year Indigenous law course.

For Smith, the mandatory course allows all law students to be on the same page with regard to Indigenous legal issues and helps reduce instances of racism among the student body. However, Smith noted that for Indigenous students, this class can still create disparities.

“While the opportunity to learn more about the histories of our peoples is incredibly important, it can still take an emotional toll on you that other students may not have to deal with,” Smith wrote

Devin Botar

Varsity Staff

Students looking for an official U of T page on the social messaging app Telegram can expect to find crime and Mexican pornography instead.

The Varsity has uncovered a pattern on the messaging and social media app Telegram, where networks engaged in illicit or criminal activity have been presenting themselves as official U of T channels to evoke trust or avoid scrutiny.

Telegram, based in Dubai, has become an international hub for criminal activity in recent years.

Two Telegram channels identified by The Varsity used the name “University of Toronto,” and displayed the U of T logo as their icon. One appeared to be linked to an India-based contract cheating service and also hosts potential scammers targeting vulnerable students, along with a forger who charged 100 USD for fake TCards.

The other channel belonged to a Mexico-based deep web pornography ring, which explicitly stated that it was “disguised as a university” to bypass content restrictions.

The contract cheaters, the scammers, and the Post-Impressionist forger

One of the channels, created in 2023, included a link in its description to another Telegram channel belonging to TutorSolve, an India-based contract homework and assignment service. Tutorsolve offered to complete clients’ coursework for them, charging in one instance 200 United Arab Emirates Dirhams –– around 76 CAD –– for a 4,000-word assignment.

Contract cheating has become a growing concern for U of T. Easy Edu, a company offering similar services to Mandarin-speaking

students, is currently being sued by the university in federal court.

In January and February of this year, an anonymous user on the channel posted irregular job offerings, “Need 5/6 workers on immediate [sic] basis… 2 girls 1 boy required,” followed by “Permanent shifts,” “Both sin/cash,” and finally, “Only dm if you can start immediately.”

In July 2023, a since-deleted account asked, “Hello… Any one looking for education loan[?]”

Another user responded, “Is it for international students[?]”

Many members of the channel appeared to be international students — a group often targeted by scammers on apps such as WhatsApp, WeChat, and now Telegram.

The channel also hosted other illicit activities. In February, a user named “IDArtist23” posted, “Anyone need a custom scannable ID?”

The user’s profile photo depicted a forged Massachusetts driver’s license labelled “ID Artist,” using Vincent van Gogh’s 1889 SelfPortrait with Bandaged Ear as its headshot.

In a direct message to The Varsity , IDArtist23 said a forged U of T student card would cost 100 USD or 140 CAD. They added that the fake

to The Varsity. “I think that the faculty has done a good job communicating the supports available for students who may be affected by the material, but it’s still a barrier that Indigenous students face.”

ILSA’s mandate as a support and social group — providing cultural programming, community events, and career panels — helps students counter feelings of self-doubt and imposter syndrome, while also supporting their professional development.

ILSA’s recent work to take part in the Indigenous Bar Association, to learn from the Black Future Lawyers Program, and to expand its reach to Indigenous undergraduate students maintains its goals to help all Indigenous students know that Jackman is available to them. Smith reflected on the opposition to TRC by asking for an open mind from non-Indigenous students.

“Much of the Canadian history we have been taught has been one-sided, if not flat-out wrong. Carrying those misconceptions is not a personal failure, but a resistance to learning or to changing them is. Reconciliation begins with truth, and we all have a duty to understand what that truth is.”

card would not be able to be scanned because “It takes a lot of time to crack its barcode… the cost is tens of thousands of dollars.”

Students have previously been caught with forged TCards when sending impersonators — often hired through contract cheating services — to take exams on their behalf. These fraudulent cards typically displayed the real student’s name but the impersonator’s face, making them difficult for invigilators to detect.

“Channel disguised as a University”

The other channel, which also used the name “University of Toronto” and displayed the U of T logo as its icon, had 62,234 subscribers at the time of accessing. This number may have been artificially inflated by bots, although at least several hundred users appeared to be active.

The channel was created on June 20 this year. That same day, the administrator posted, “It’s the final day of #UofT fall convocation 2025! ��Watch every #UofTGrad25 ceremony live at http:// utoronto.ca/convocation.” The message was identical to one posted earlier that day on U of T’s X account.

The following day, the administrator posted a message in Spanish containing a link to another Telegram channel called “Clancy Legiøn,” or “ClancyNoRules,” which primarily contains sexually explicit content. Since then, most messages on the impersonator channel were deleted shortly after being posted.

Before deletion, a November 9 message contained instructions for purchasing access to an exclusive, “VIP” pornography channel. It advertised a price of 100 MXN — 7.65 CAD — to be transferred to a Mexican bank account traced by The Varsity to the state of Nuevo León state near the Texas border.

Another message included a sexually explicit video with “University of Toronto” embedded as a watermark. The accompanying Spanish caption translated to, “Channel disguised as a university.” Messages also referred to previous channels run by the group that had been banned by Telegram. On the morning of November 12, the ClancyNoRules channel became inaccessible, displaying the notice, “This channel can’t be displayed because it was used to spread pornographic content.” Later that day, the channel reappeared.

In October, the administrator of “ClancyNoRules” messaged the channel, “The creation of my groups has never been intended to harm content creators. While we filter everything for free, I’m always open to dialogue with creators to remove their content. (I’ve already worked with several),” and included a warning to “beware” of scammers frequenting the channel.

The impersonator “University of Toronto” channel appeared to function as a central hub for the operation. While it did not host pornographic content directly, it provided links to other channels that did — and it remained online even when those channels were inaccessible.

The Varsity found no clear reason why U of T was chosen as the group’s cover.

A university spokesperson wrote to The Varsity, “The university does not use Telegram for official purposes. When the university is impersonated in any realm, we take action, including through legal means and the services of the platforms in which such impersonation takes place.

Matthew Johnson, a director at Canadian digital literacy NGO MediaSmarts, wrote in an email to The Varsity, “Unfortunately it is difficult for organizations such as universities to prevent impostor accounts; while there are tools for reporting them, both through email and within the app, large platforms such as Telegram often respond slowly or not at all.”

“While some social networks, including Telegram, do offer verified accounts, this is not always very helpful because verification policies frequently change and because many legitimate official accounts choose not to go through the verification process.”

UTMSU President Park highlights

Arunveer Sidhu UTM Bureau Chief

The University of Toronto Mississauga Students’ Union (UTMSU) has been lobbying to change UTM’s official land acknowledgement since the motion was submitted during their 2024–2025 Annual General Meeting. The Committee for Indigenous Justice and Collaboration was created in response.

Although the motion was passed by the 2024–2025 UTMSU executive committee, the current executives have been engaged in preliminary conversations with UTM’s senior administration.

The UTMSU also have their own land acknowledgement, and is currently lobbying to recognize National Day for Truth and Reconciliation as valid for special consideration requests for extension on coursework.

Current wording concerns

In an email to The Varsity, UTMSU President Andrew Park shared some concerns identified by the student body and the committee about the specific wording of phrases in UTM’s current land acknowledgement.

The current acknowledgement states, “I (we) wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates.” Park criticized

the use of “wish to,” and wrote that “land acknowledgements should be intentional, and not aspirational.”

In the sentence, “we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land,” Park wrote that the word “grateful” can be harmful, as “not all Indigenous community members feel ‘grateful’ given histories of violence and dispossession.”

Apart from the language used in the current land acknowledgement, Park also noted that it contains no references to the treaties that cover the Toronto Area.

UTSG and UTM are on Treaty 13 and 13-A territories, which were negotiated between the

U of T Professor compares

Crown and the Mississaugas of the Credit in 1805 and 1806. Treaty 13 has been legally disputed for its lack of documentation and clear land boundaries, which led to a $145 million settlement with the Mississaugas of the Credit in 2010.

UTSC is on Williams Treaty territory between seven First Nations of the Chippewa of Lake Simcoe and the Mississauga of the north shore of Lake Ontario, which was signed in 1923. This treaty was struck after the government found that Indigenous valid land claims were valued at up to $30 million at the time, but the treaty exchanged the 355,000 acres of land for only $500,000. In 2018, the Government of Canada and the Province of Ontario settled with the seven Williams Treaties First Nations for $1.10 billion.

UTMSU’s current progress

Currently, the UTMSU is in “preliminary conversations with UTM’s senior administration and the Office of the Vice-Provost, Students, all of whom have been receptive to our proposals,” wrote Park.

The UTMSU plans to return with a formal proposal in the spring after finishing their research and consultations over the remainder of the year. The UTMSU will meet with them again in early December.

The original land acknowledgement at UTM was written in 2016 and revised in 2021. The revision was made in consultation with the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation (MCFN) to “better [represent] their past and present identity.” Park cited this revision, sharing that it “demonstrates both the capacity and precedent for future revisions.”

The revision was detailed in a letter to the UTM community on May 12, 2021, in which it was also stated that the revision “represents one of many necessary steps toward realizing a pillar of our institutional future,” and that “we look forward to instituting additional changes together.”

Park wrote, “this work is significant in both scope and impact. While the process will take time and care, it is essential that Indigenous voices across our campuses and communities guide each step.”

Council member Ramy Elitzur says massacre “was horrible, but pales in comparison to what happened on October 7”

Emma Dobrovnik Assistant News Editor

On November 6, U of T’s Governing Council addressed the university’s decision not to shut down the University of Toronto Mississauga Student Union’s (UTMSU) event “Honouring Our Martyrs.” At the meeting, longtime council member and accounting professor Ramy Elitzur compared the event to a commemoration of the massacre at the École Polytechnique.

Following statements from President Melanie Woodin and UTM Principal Alexandra Gillespie, Elitzur said the event was “commemorating the martyrs of the Hamas on the day that the worst massacre of Jewish people ever happened since the Second World War. I cannot imagine the university letting an event commemorating Marc Lépine on the day of the massacre of École Polytechnique, which was horrible, but pales in comparison to what happened on October 7.”

Elitzur continued, “This actually violated the university’s most fundamental principles, inclusivity and safety, and I don't buy the administration response that the union leaders did not intend for the event to be antisemitic or supportive of terrorism… This insults my intelligence and everybody here.”

In an email to The Varsity about the comments he made during his time on the Governing Council, Elitzur wrote, “It’s important that my remarks be viewed in the context of my entire statement,” adding, “I stand behind what I said.”

Elitzur, who began as a teaching staff governor in July 2023, has been an outspoken critic of the university’s response to pro-Palestine student activism. In a June 2024 Governing Council meeting, he said, “When you talk about inclusivity,

I’m not included. Jewish people are not included, Jewish [lives] do not matter… The actions of the university over the last… year showed me I don’t matter.” Elitzur said that U of T is where EDI “became IED, improvised explosive device, which is the preferable weapons of terrorists.”

In the same meeting, he also claimed he was “pretty sure that if you are a Jew now, you won’t be admitted to the [U of T] medical school.”

In an email to The Varsity, a spokesperson for the university noted that Elitzur’s claims about Jewish students at the U of T medical school “have no basis in fact.”

Since 2024, Elitzur has also voiced concerns about the Occupy for Palestine’s student encampment. In a National Post opinion article, he compared Jewish students who participated in the encampment to Jewish people who served in the Nazi military. In the article, he described the encampment as a “violent mob,” and called on the university to take a more aggressive approach.

In a 2024 interview with The Varsity, when asked why the university had not taken action against Elitzur, former U of T President Meric Gertler said that the university upholds academic freedom and freedom of expression, including “the right to say things that are controversial and even troubling or disturbing,” as long as the speech is not illegal and does not breach university policy.

According to the Governing Council’s “Expectations and Attributes of Governors and Key Principles of Ethical Conduct,” governors are expected to “support the fullest range of respectful and constructive debate.” Governors’ behaviour should also reflect the university’s broader values of academic freedom, collegiality, and civil discourse.

When asked whether Elitzur’s comment constituted respectful and constructive debate, a university spokesperson referred to the Statement on Freedom of Speech, which noted that “the values of mutual respect and civility may, on occasion, be superseded by the need to protect lawful freedom of speech.”

U of T designates National Indigenous Peoples Day as new Presidential Day

Byline: Junia Alsinawi, Deputy News Editor

National Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21 will be recognized as a U of T Presidential Day starting in 2027. When it falls on a weekday, the university will be closed and it will be a paid holiday for employees, as happens on other Presidential Days. Previously, individual departments, faculties, and campuses at the university regarded the day as a holiday, but no sweeping institutional-wide recognition has been in place until now.

In the announcement of the change published by the Division of People Strategy, Equity, and Culture, Shannon Simpson, Senior Director of the Office of Indigenous Initiatives, said, “I think it helps to demonstrate that U of T values the Indigenous community that is here, and beyond.”

University looks for input in search for new Arts and Science Dean

Byline: Junia Alsinawi, Deputy News Editor

On Friday, Faculty of Arts & Science (A&S) students, staff, and faculty received an email from the A&S Office of the Dean asking them to fill out a survey for the Advisory Committee about the ideal candidate for the next Dean of the Faculty of A&S. The email noted that all answers to the survey “are held in absolute confidence.”

The survey has five questions, which ask about the ideal qualities for a new Dean and the challenges they might face. The fourth question gives the opportunity to nominate individuals for the role, and notes that “selfnominations are accepted.”

Since former A&S Dean Melanie Woodin’s appointment as President of the university, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Professor Stephen Wright serves as Interim Dean until June 30, 2026.

Carney’s budget passes in tight confidence vote

Byline: Emma Dobrovnik, Assistant News Editor

On November 17, Prime Minister Mark Carney’s federal budget passed in a confidence vote of 170 in favour and 168 against, meaning that Canada won’t be plunged into a snap election over the holidays. In order to pass the budget and avoid triggering an election, the Liberals needed two opposition votes or four abstentions. In the end, five Members of Parliament (MPs) — two from the New Democratic Party (NDP) and two Conservatives — abstained, with Green Party leader Elizabeth May voting in support of the budget.

Although the budget inflates Canada’s deficit and projects $60 billion in spending cuts, Carney argued that strategic spending will boost Canada’s productivity and global competitiveness.

With new COVID-19 variant emerging, mask mandates return to Toronto hospitals

Byline: Hilary Cheung, Lead Copy Editor

Since November 18, staff, patients, and visitors in the University Health Network (UHN) must wear masks inside hospital facilities in response to the respiratory virus season. This includes the Toronto General Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

From October to November, there was a surge in COVID-19 cases. The new variant — scientifically designated XFG, commonly referred to as “Stratus” — has the usual symptoms of COVID, but with a more severe sore throat than prior strains. The primary concern associated with XFG pertains to its potential to evade antibodies and its effectiveness in binding to human cells.

Medha Barath Business and Labour Editor

Indigenous people remain underrepresented in the Canadian business world — only one to 1.5 per cent of small and mediumsized businesses in Canada had a majority Indigenous ownership in 2020, even though Indigenous people made up five per cent of the population.

Improving Indigenous representation in executive spaces begins at business schools, and the new Rotman Indigenous Business Association (RIBA) aims to support that shift. Evanne Bell, a third-year student in the JD/ MBA program and the President of RIBA, spoke with The Varsity about the club’s goals.

The inspiration behind the club

When she began the MBA portion of her studies, Bell noticed that Rotman had no Indigenous student associations, even though many other cultural associations existed.

After enjoying other leadership roles — including serving as president of the Indigenous Law Students Association — Bell thought, “Why not?” and began the process of creating a club for Indigenous students at Rotman.

One of the RIBA’s main goals is to build greater interest in Indigenous business topics. Bell pointed out that a general lack of awareness about this subject at Rotman could be a challenge for the club. She said,

“[Many students] don’t know a lot about it, and because of that, [they] can be a little hesitant to engage with these topics.”

Still, Bell stresses the importance of understanding these topics. “Lots of big infrastructure projects right now, they’re all going to have Indigenous involvement, right? So even if you’re not an Indigenous person, if you’re going to do business in Canada, you need to be aware of this stuff,” she said.

In fact, two of the club’s executive members — Claudia Velimorovic, a fourth-year MBA/ MGA student, and Aaditya Juvekar, a thirdyear JD/MBA student — are non-Indigenous students. who share this passion and support the club’s mission. “They’ve been an amazing support… they are passionate about the topic and they believe in it,” Bell said.

Economic reconciliation at Rotman

Only 22 per cent of Indigenous employees in business, finance, and administration held professional or middle-management roles, compared to 36 per cent of non-Indigenous employees in these sectors.

Bell believes that this underrepresentation may stem from the limited number of Indigenous students in business schools. As a result, RIBA has been working with the Rotman faculty to address this gap and support efforts to recruit more Indigenous students. “There [have] been conversations about how do we do that? How do we get more interest from

An expansion of U of T’s partnership with Redbird Circle Inc. brings hands-on agricultural learning and entrepreneurial empowerment

Rebecca Liu Associate Business and Labour Editor

Increasing agricultural participation from Indigenous communities can boost production, promote Indigenous health, and increase food security. This is certainly not a small benefit — so why haven’t Indigenous communities been able to participate more in agricultural entrepreneurship?

And what is U of T doing to help create employment opportunities and entrepreneurship training in this sector?

Legislative barriers to entrepreneurship

Indigenous people retain exclusive rights for the use and occupation of reserve lands, or land the Canadian government has designated to be used by First Nations communities. However, these lands are still legally considered to be owned by the Canadian government. This means that Indigenous peoples cannot transfer, sell, or surrender their land. While this protects their ownership, it also means commercial banks are reluctant to loan money for ventures that involve reserve land — they cannot use the land as collateral and seize it if the borrower is unable to pay the loan back.

Additionally, the Indian Act means reserve land cannot be leased to non-Indigenous farmers without explicit approval from the Minister of Indigenous Services. The process of gaining approval can be tedious and acts as a bureaucratic

indigenous students in doing an MBA or a masters degree, and how [we run] those recruitment events?”

Bell is also working to address a lack of Indigenous material in the Rotman MBA curriculum. An essential tool in MBA classes is the case study — a detailed, real-world analysis of a business scenario. “As a first-year MBA student, I didn’t come across a single Indigenous business case,” she said.

Bell sees the introduction of more case studies on Indigenous businesses as the most effective way to Indigenize the curriculum. She has already begun contributing to this effort.

“I’m actually writing a business case study on an indigenous business. My hope for that case study is that it gets included in the business school curriculum,” she said.

How to engage with RIBA

Since its establishment in February, RIBA has hosted several events to encourage student engagement with Indigenous business topics. The club invited lawyers Thomas Isaac and Jeremy Barretto from the Canadian corporate law firm Cassels to discuss their new book, The

Law of Indigenous Ownership and Projects , at its inaugural event — held in collaboration with the Rotman Energy and Natural Resources Association (RENRA).

RIBA’s kickoff event for the new academic year took place in September, featuring a speaker from the Canadian Council for Indigenous Business — an organization that aims to strengthen relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous businesses. Bell described these events as highly educational, and said, “You always learn something new.”

Most recently, in October, RIBA partnered with RENRA again to host an event titled Indigenous Leadership in the Energy Transition. Guest speakers from energy corporations and Indigenous businesses discussed the future of Indigenous leadership in the sector and how Rotman students can contribute.

Students interested in getting involved will be able to visit RIBA’s website once it launches, as it is still being set up. “We also have a LinkedIn page where we’re now posting about events and stuff. So keep an eye [out],” Bell said.

barrier to Indigenous people from profiting from agricultural leasing.

With these legal and bureaucratic frameworks, Indigenous communities face more obstacles to building generational wealth using their reserve land.

Redbird Circle’s partnership with U of T to promote Indigenous entrepreneurship

Despite these existing barriers, Jonathon Araujo Redbird, co-founder of Redbird Circle Inc. — a business dedicated to providing Indigenousfocused skills, education, and training — believes that empowering Indigenous people through entrepreneurship is still possible.

U of T has partnered with Redbird since 2021 to provide the Indigenous Entrepreneurship Program. This initiative, which started with a 16week pilot at UTM, offers free, online workshops on entrepreneurship through an Indigenous lens.

As Redbird said in a 2021 UTM article covering the original pilot program, “we will combine Indigenous knowledge with Western pedagogies to create a new learning framework that empowers the next generation of Indigenous entrepreneurs.”

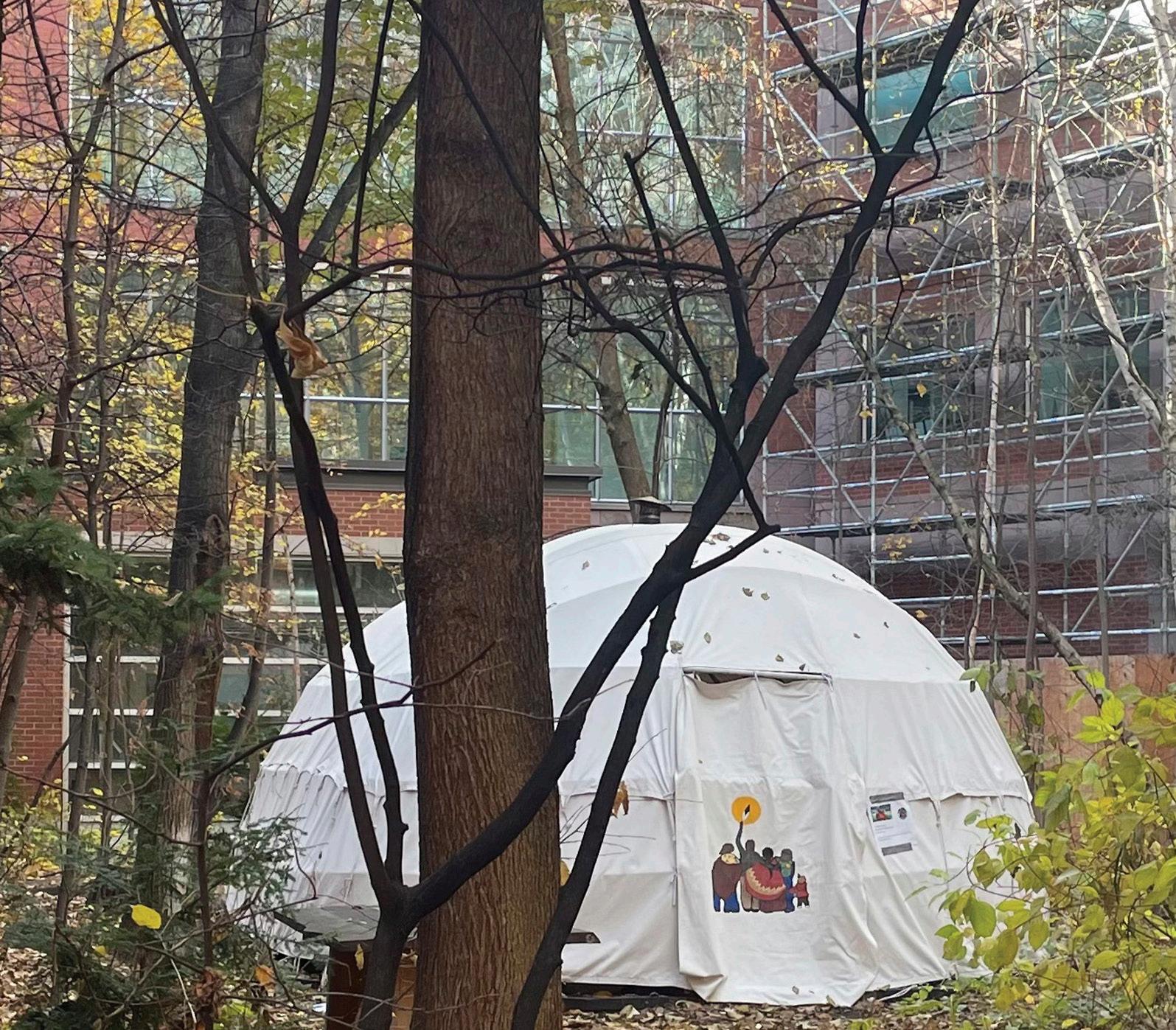

Redbird Circle has now expanded their partnership to UTSC, with the construction of four Indigenous Greenhouse Geodesic Domes beside the tennis courts and near Highland Creek Valley. These domes are hemispherical, self-supporting structures that are each 24 feet tall, connected by accessible

gravel paths, and entirely powered by solar panels.

All of the construction is meant to be temporary — the domes will remain at UTSC for one to five years, according to UTSC’s website about this project. However, extensions are possible based on the program’s success, especially with an expansion to the UTSG campus.

Hands-on learning based on Indigenous knowledge

The four domes will function as hubs for experiential, hands-on learning for people in the virtual Indigenous Entrepreneurship Program.

Redbird wants to use the domes to teach Indigenous youth “how to grow produce from the land and how we can learn entrepreneurship through that process.” Each dome has a distinct function contributing to the goal of fostering collaboration, employment opportunities, food security, sustainability, and Indigenous identity.

The “Innovation Dome” is the first dome where students can try new agricultural technologies, using innovative farming strategies to promote sustainable food security.

In the second dome, students will work with “Just Vertical,” a hydroponics technology business that uses mineral nutrient solutions in water rather

than traditional soil. Just Vertical is a U of T start-up that maximizes growing space by growing plants vertically on levels one on top of each other.

The “Medicine Dome” is third, and it is centred around traditional Indigenous teachings. Specifically, students can learn from elders to plant traditional Indigenous plants for healing, focusing on both spiritual and physical remedies. This dome was designed with the Anishinaabe Medicine Wheel in mind, promoting physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health by growing specific crops.

Finally, the fourth dome offers hands-on training on cultivating high-yield crops for sale at farmers’ markets or to leverage for agricultural entrepreneurial pursuits by Indigenous communities.

Putting the power into their own hands

The continued partnership between Redbird Circle and U of T holds immense potential for promoting empowerment through entrepreneurship.

There is a long way to go to increase Indigenous agricultural participation, but initiatives like UTSC’s Greenhouse Geodesic Domes are a good start.

The most important insight from this project is simple: real change that creates an impact only happens when Indigenous knowledge and decision-making are in communities’ own hands.

November 25, 2025

thevarsity.ca/cateogory/opinion

opinion@thevarsity.ca

Augustus Crysler-Hill Varsity Contributor

In 2001, Ontario introduced the “Native Studies” curriculum for grades 9–12; since then, the province has been expanding Indigenous content in the public school curriculum in an attempt to advance Indigenous visibility and reconciliation.

The Indigenous peoples of this land have been painted as tragic, long-gone peoples who have ceased to exist in modern society. This is partially because the information you will find in most textbooks detailing the history of Indigenous peoples focuses on the arrival of Christopher Columbus, the conflicts between settlers and Indigenous nations, and the history of residential schools in Canada.

While these are important parts of the colonial history of Canada, they tend to leave out the ongoing struggles that Indigenous peoples still face today, and discredit the resilience of Indigenous peoples in the face of assimilation and oppression.

Instead of simply focusing on events of the past and what the government has done to apologize for these atrocities, a better way of reconciling with the people of this land is by supporting our cultures, and learning about modern-day issues affecting Indigenous peoples in significant ways. The quality of life, and dignity of the people living on reserves are impacted by issues such as resource extraction, unsafe drinking water, education inequalities, and high suicide rates.

In urban settings, Indigenous peoples are affected by marginalization in the foster care system, overrepresentation in prisons, and ongoing discrimination in employment, housing, and healthcare. Without considerable attention paid to these issues, nothing will change for Indigenous peoples, and we will continue to be marginalized and oppressed by the society that we live in.

This Western view of Indigenous peoples tends to depict us as victims of atrocities that were perpetrated in the proverbial ‘olden days.’ This not only overshadows the current issues that Indigenous peoples face, but also overlooks the vibrant cultures, joy, and laughter that have persisted despite hundreds of years of oppression.

I believe that it’s important to recognize Indigenous joy as an essential part of colonial resistance. I’ve seen it with my own grandpa and great-grandmother, who both went to residential school. I’ve also seen it with my cousins, who have been subjected to systematic oppression in the foster care system. Despite this oppression, they are still some of the most joyful people that I know.

I consider the joy and humour that are present in Indigenous cultures to be resistance in multiple ways. While the Canadian government may be able to take our land, suppress our cultures and religions, and force settler languages onto our youth, the one thing they cannot take away is our joy. By expressing this joy, Indigenous peoples show that they are still alive and well, and reject the societal narrative that Indigenous peoples are simply victims of the past.

Indigenous joy is not only important in the context of resistance, but also due to its healing and connecting qualities. Laughter serves as a connection between family members and is key to Indigenous communities. It gives relief in times of hardship and allows our people to discuss traumatic events.

Without this sense of humour, it’s more likely for the survivors of trauma to be overridden with negative emotions. Thus, this humour is subconsciously used to process trauma and pain in a healthy way. Indigenous joy is the backbone of our survival, as it serves to create and strengthen community ties.

I think that it’s time to start viewing Indigenous peoples in Canada not just as products of their

Canada prides itself on upholding the Rule of Law, presenting its constitutional framework, democratic principles, and commitment to human rights as defining components of the country. Despite promoting this image, a closer look reveals a different reality. Canada has not consistently honoured the treaties that laid the foundation for its formation.

I believe that the Land Back movement –– an ongoing Indigenous-led movement which calls for the return of land to Indigenous communities ––

draws attention to the tension between the Rule of Law and Canada’s lack of respect for treaties, as a constructive call for accountability and transparency. True justice requires more than performative acts of reconciliation. Land Back necessitates that Canada honour the treaty agreements and commitments made to Indigenous nations and to return land to Indigenous communities.

Canada’s constitutional framework, established through the “British North America Act, 1867,” and reaffirmed by “the Constitution Act, 1982,” advocates the principle of equality under law. However, Canada’s inability to uphold treaty rights reveals a gap between principle and practice.

circumstances, but rather as ongoing participants in colonial resistance, with vibrant cultures and social life. By recognizing the joy that Indigenous peoples exhibit, evident in our oral history, traditions, and communities that still stand today, we can see that Indigenous people are more than just a group to feel sorry for and ‘empathize’ with.

Although we are dealing with the ongoing issues that have been affecting us since the arrival of Columbus, it should be recognized as part of

The Rule of Law forms the foundation of the Canadian legal system, and is meant to ensure that no person or entity is above the law. Upholding the Rule of Law, therefore, requires honouring treaties and respecting Indigenous sovereignty, treating these obligations as equal in importance to the rights of every citizen in Canada.

The Land Back movement is more than a social cause. It is a call to align Canadian law and legislation with the principles that the country claims to uphold. Canada is a nation where millions come seeking opportunity and a better life. That vision must begin with justice for the first communities that called this land home.

Upon closer examination, Canada’s commitment to the Rule of Law begins to unravel in the face of Indigenous land rights, revealing a contradiction that the Land Back movement does not allow us to ignore.

The British North America Act and the Constitution Act were primarily enacted to create and regulate state power. However, rather than serving states, treaties were nation-to-nation agreements that guaranteed the recognition of Indigenous authority and protection of territories.

Despite these agreements, the Crown’s actions in violation of treaties, including resource extraction and the use of force against land defenders, reveal a political system that prioritizes state power –– colonial power –– over nationhood.

Canada's Rule of Law stems from King George III’s 1763 royal proclamation, which outlined “Indian territories” where First Nations “should not be molested or disturbed.” These measures recognized Indigenous authority and established clear legal responsibilities that the Crown has often been unable to fully uphold.

For example, in 2022, the Canadian government allowed for the construction of the Coastal Gaslink pipeline on Wet’suwet’en lands despite the disapproval of Wet’suwet’en leaders. It was described by Ketty Nivyabandi, Secretary General of Amnesty International Canada, as

the process of reconciliation that we are a resilient people. Indigenous peoples are strong-willed, and our communities are deeply connected through laughter, love and joy.

Gus is a first-year political science student with Métis roots, identifying as both Plains Cree and English. Born and raised in Vancouver, BC, he looks forward to finishing his degree and eventually returning home to the West Coast.

a “brazen violation of the community’s right to self-determination” as the project was built on unceded territory.

Ignoring treaties does more than create injustice. I believe it weakens the nation’s moral and legal frameworks.

Movements such as Land Back demand justice, and U of T, situated on treaty lands, has supported Indigenous sovereignty through initiatives such as the Indigenous Research Network and the annual All-Nations Powwow. These efforts should continue, as they represent a step toward progress and awareness while helping to uphold the legal and moral obligations owed to the First Peoples of this land.

In the past, colonial legislation wrongly defined Indigenous governance as inferior. Indigenous legal traditions are living frameworks rooted in community and reciprocity. These values demonstrate integrity and a willingness to negotiate.

Recognizing these systems as legitimate is important.

Supporting the Land Back movement does not attack Canada’s legal system, but it calls on Canada to fully honour its constitutional promises. True adherence to the Rule of Law requires acknowledging the historical and ongoing breaches of treaties. Accountability begins with accepting past mistakes and taking concrete steps to prevent their recurrence.

Land Back demonstrates that justice is achieved not through words or gestures, but through meaningful action and the restoration of what was unjustly taken.

If equality before the law, the foundation of Canada’s legal system, is to be more than a mere image, it must begin with the land and the people whose sovereignty is ignored.

Komal Kalia, a U of T Global Scholar, is a fourth-year student at the University of Toronto Mississauga, currently pursuing a political science specialist and certificates in politics, law, and social justice, and global perspectives.

Photo XX X, 2024 thevarsity.ca/section/photo photo@thevarsity.ca

November 25, 2025

thevarsity.ca/category/arts-culture arts@thevarsity.ca

Chantal Jones

Varsity Contributor

Long ago, on the sacred lands of the Ojibwe people, there lived an elder known as Asibikaashi — affectionately referred to as the ‘Spider Woman.’ Her wisdom ran deep, and her compassion touched every soul in the tribe. With a heart attuned to the spirits of the earth and sky, she watched over her people, shielding them from harm and guiding them through life’s trials. Her presence was a source of comfort and strength, a beacon of nurturing light in times of darkness.

One day, as Asibikaashi wandered through the thick forest, she came upon a small spider and thought, “Ever cute.” She then noticed that it was spinning its web between the branches of an ancient cedar tree. Sunlight streamed through the canopy, casting gentle shadows on the forest floor. Asibikaashi paused, captivated by the spider’s graceful movements, and watched as each thread was woven with loving care. The web shimmered like a precious gem in the fading light, filling her with a sense of peace and awe.

Asibikaashi stood in quiet admiration, watching the little spider work with tireless devotion. Though seemingly fragile, the web held a quiet strength and resilience that stirred something within Asibikaashi. A thought began to form, a vision of a way to shield her people from the darkness that often haunted their dreams. As twilight

descended and stars set about to twinkle overhead, Asibikaashi leaned in and spoke lovingly to the spider.

“Little one,” she murmured, her voice soft and full of respect, “your web is a treasure, a sacred gift from the spirits. Would you share your wisdom with me, and help create a tool that could guard my people from bad dreams?”

The spider paused, recognizing the purity of Asibikaashi’s heart. The little one gazed up at her with its many twinkling eyes, and for a moment, the forest seemed to hold its breath. Then, with an open heart and subtle nod, the spider agreed. Side by side, as one, they worked through the night, weaving a web onto a small, round hoop fashioned from the branch of a fallen willow tree.

Asibikaashi’s hands moved in harmony with the little spider’s, a mirror of its delicate movements, threading and looping to create an intricate web.

Throughout the night, they wove and whispered prayers to the forest spirits, seeking their blessing. Asibikaashi shared tales of her people: their joys, their sorrows, their hopes. The little spider listened in silence, adding its own gentle threads to the growing web. As the first light of dawn pierced the trees, the web within the hoop was complete: a radiant circle of intricate patterns, echoing the rays of the rising sun.

Asibikaashi was in awe. She lifted the hoop, its web glowing softly in the morning light. She

offered words of gratitude to the spider, then directed her voice to the spirits of the earth and sky.

“Spirits of land and air,” she prayed, “gift this web with your protection. Allow it to trap the bad dreams that trouble my people, and allow only the good ones passage, bringing peace and comfort to all who sleep beneath it.”

The spirits, moved by her heartfelt plea, granted her wish. From that moment on, the dreamcatcher became a treasured symbol among the Ojibwe, a reflection of Asibikaashi’s wisdom and the sacred power of the little spiders’ protection.

The symbol is hung above sleeping spaces in our people’s homes, trapping the dark dreams in its threads and letting the good ones slip through the central hole, gently descending to the sleeper below. A bead is placed in the web of strings in honour of the little spider who shared their wisdom.

Nana told me and my siblings this story when we were children. We visited her at Little Otter Lake, where she lives off-grid to this day. The story was also shared with me by my mother when we hung our dreamcatchers over our beds. I expressed creative freedom while writing the teaching to add my own personal flair.

On October 28 at Hugh’s Room Live, I attended a performance of Empire Étrange: The Death of Louis Riel, conducted by Cree composer and conductor Andrew Balfour. The show was part of a series by Toronto-based music presenter Soundstreams called “Encounters,” which puts on free educational performances and talks. The production included a choir, a violinist, a cellist, a percussionist, and a pianist.

Empire Étrange is an oratorio, a musical work for voices and instruments that tells a story — often one that is spiritual or religious.

Balfour explained in a Q&A session after the performance, that this production is a soundscape that tells the story of Métis leader Louis Riel and the Red River Resistance, and speaks from an Indigenous perspective.

Balfour wished to fight against colonial perspectives and instead show a perspective of Riel that is normally not engaged with by settler-colonial historians. Both the English and the French present Riel as being either a hero or a villain. However, Balfour found it interesting that Indigenous depictions of him are often left out, since they could provide a nuanced look into this story that considers the full complexity of who Riel was, both as a person and a political figure.

Balfour is from Fisher River Cree Nation, and grew up in Winnipeg, Manitoba — the same area where Louis Riel was born and raised. In the Q&A session, Balfour suggested that history cannot be read about in a book; “you have to experience it.” He recounted how growing up in downtown Winnipeg, he would walk by Riel’s grave every morning and would think about his resistance movement.

Louis Riel, who lived from 1844–1885, was a Métis leader, the founder of Manitoba, and a central figure in both the Red River and NorthWest resistances. Riel sought to protect Métis political, cultural, and land rights in the face of Canadian expansion, negotiating a “List of Rights” and leading a provisional government in Red River.

Later, frustrated by broken promises over land titles and representation, Riel returned to lead a second uprising in Saskatchewan, asserting Métis nationhood through a provisional government. On November 16, 1885, for his resistance against the Canadian government, Riel was tried for high treason and hanged. Over time, his legacy has shifted from that of being a rebel, to a martyr and founding figure for both Manitoba and Métis rights.

Balfour wrote about Riel because he saw Riel’s life as dramatic, politically powerful, and still shaping Canadian identity long after his execution. Balfour’s goal was to tell the story of a figure considered controversial in settlercolonial narratives through an Indigenous perspective, which he feels is often lost in mainstream history lessons. Every musical moment is meant to explore the Indigenous peoples’ perspective of a political conflict they had no say in.

The oratorio is set during the Battle of Batoche in 1885, at a time when the bison of the land were already nearing extinction, and tens of thousands of Cree and their communities

were being pillaged. The show opened with sounds of wind and grass from a flute and a drum. In the background, whispers from the choir sang ominously, “Do you know me? You cannot escape me. I see you! Ha ha ha! I see you! I’ve found you… Are you watching?” The audience was transported to Riel’s childhood, where he first witnessed a fence being built on the land he grew up on, his home.

Balfour told the audience that it didn’t make sense to Riel that this new border was being placed on the land, and that Riel wrote in his diary that Turtle Island was facing a European settler awakening.

Balfour addressed the audience before the next movement, “Awasis,” to give context. The text in the movement translates to “Always be at peace with oneself, Child.” The next song began with Pôni-Pimâtisiwin, which means “The end of living,” with the drums beating menacingly and the choir joining with a tone of anticipation and foreboding.

The fourth movement was an unconducted interlude scored for piano and violin. It is about the speech John A. Macdonald made about

Indigenous people. The violin and piano make abrupt screeching sounds, while a soloist sings part of the speech, “We must vindicate the position of the White man. We must teach the Indians what law is.”

The piece concludes with the day of Louis Riel’s execution in Regina. On the land the Cree call Oscana, “Pile of Bones,” his rushed political sentencing and death were ordered by MacDonald and the City of Ottawa. Balfour returned to the stage to introduce the final song, “[Riel] thought for all intents and purposes he was going to be pardoned, but he must have realized last minute he was not going to get away with it, so he recited the Lord’s prayer in français.”

In the Q&A, Balfour explained that Empire Étrange is an amalgamation of parts of a different oratorio of his from 2013 with the same name. With this updated oratorio, Balfour wanted to share a broader story about Riel’s advocacy for Indigenous populations.

Balfour shared his experience as a survivor of the Sixties Scoop and how he was colonized at six months old when he had been taken from his family. He shared how it is therapeutic to learn his Cree language, and refers to it as preancestral medicine. Balfour also mentioned how he is relearning his history from an Indigenous perspective. Indigenous language revitalization and reclamation is one of the key components of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as it contributes to healing of a cultural loss.

In a statement before the production, artistic director of Soundstreams Lawrence Cherney explained that although stories can’t bring stability to a fractured world, they can bring reflection upon and context to our world. Bringing stories from diverse voices, such as Indigenous creators in Canada, is vital to cultural preservation.

Jasmine Wemigwans is an Indigenous artist, researcher, and graduate of the Master of Information and Library Science program at the University of Toronto. Her work bridges Indigenous knowledge systems and information studies, exploring how creativity, digital design, and cultural protocols can coexist in academic and technological spaces.

Meagan Mellor Varsity Contributor

When I researched Tea N Bannock online, I kept seeing identifiers on Google and the Tea N Bannock website that classified it as “Native American” and “Aboriginal,” which confused me — I wondered why the classification was so broad. I suspected that the restaurant was either appropriating or misclassifying Indigenous cuisine. Walking into the restaurant, I was hesitant, but upon diving deeper, I realized that this restaurant is the only one left in Toronto that classifies itself as Indigenous. I realized that the marketing wasn’t a result of my original assumptions; it was about survival.

I think that Tea N Bannock is a symbol of the unfair competition and scrutiny that Indigenousowned businesses face in the GTA and Canada as a whole. While I’m happy to say that I absolutely loved the food, there shouldn’t only be one restaurant left to preserve a timeless cuisine in one of the densest cities in North America.

I grew up beside Kahnawà:ke, Québec, and was raised in a family with several Kanien’kehá:ka or Mohawk cousins and extended family. From my lived experience, I’ve never had to make a distinction between traditionally Mohawk and traditionally Québécois foods.

The two have always been parts of the same meals. Even when eating at Indigenous-owned restaurants that incorporated both Mohawk and Québécois dishes back home, there was never a need to identify the restaurants as “Indigenous” or “Native American,” because the foods and spaces are an unquestioned part of the community.

A quiet restaurant on Gerrard Tea N Bannock is in Leslieville, right outside a 506 streetcar stop, a bustling neighbourhood in

the east end of Toronto. My partner and I visited on a Saturday, and I had anticipated a long wait for a table, like other restaurants in the area. But when we walked in, we were the only customers.

The decor and overall vibes of the restaurant were a little sterile. The tables were simple and made of wood, with some natural branches preserved in the bases, and the walls of the restaurant were a very 2000s orange.

While the decor definitely wasn’t ‘Instagramworthy,’ it really solidified that home-cooked, kitchen feeling. The restaurant displayed Indigenous artwork and animal hides on the walls, and additional wares, such as honey, from Indigenous-owned businesses.

Even though I didn’t connect with the decor, I appreciated the original artwork. I believe that it is so crucial to support independent artists, especially in an evolving art climate full of AI, and a world of art increasingly devoid of nature.

The staff were kind and almost seemed surprised to have customers. We sat ourselves, and were promptly given menus, and served water and popcorn. This was our first time being offered popcorn instead of bread or chips, making it a standout point of our experience. My partner — who ate all the popcorn, thinking there would be more — described it as “Really, really good. It’s kind of salty, and the salt just kind of sneaks up on you.”

The rest of our meal followed that same trend. The flavours were subtle, and snuck up on you after every bite. We ordered the stew of the day made with bison meat, the Three Sisters soup, and took some bear paws to go.

The prices were incredibly fair and budgetfriendly. For example, the large Three Sisters soup was only $8, but it was extremely filling.

The squash was soft and melted in your mouth. The dishes really focused on letting each ingredient shine, rather than trying to overcompensate with spices and oils.

The bison stew was more expensive than the soup, about $10 more for a small, but it was definitely worth the difference. The meat was relatively gamey, but as someone who grew up eating game meat, it had a familiar, homestyle taste, rather than something distinct. My partner, on the other hand, noticed the earthy taste right away.

Each of our dishes came with a side of bannock, so we tried both the fried and the regular. I recommend the fried bannock. It was crispy yet pillowy in the centre. The bear paws — fry-bread rolled in cinnamon sugar — tasted similar. They came out still warm, coated with sugar, and had a light cinnamon taste to them.

I definitely plan on revisiting Tea N Bannock. With every dish we ordered, we could taste that it was made in-house. It felt like it had come out of a home kitchen, rather than a restaurant.

As a student living on my own, I’m still finding my feet with cooking and am always craving something that tastes like home. It’s rare to find a restaurant that cooks food with the level of care you would find in someone’s kitchen, but Tea N Bannock accomplishes that stupendously. For me, it felt like a place of connection, where you could enjoy the simplicity of the conversation around you and the warmth of the food.

While eating, I could feel the love and effort that was put into making our meals. We left so full, didn’t break the bank, and really enjoyed our experience. I will definitely be back to Tea N Bannock. This space deserves to be preserved and uplifted; the fresh quality and affordability of the food are unbeatable, especially considering today’s rising prices in the food industry.

Supporting Indigenous businesses is crucial for community survival. Overall, this experience was a win for me!

In my artwork, I seek to capture some of the emotions that humans experience. Through colour, I attempt to illustrate the feelings that affect us as a result of our environments. This piece was inspired by the book Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese, which demonstrates the struggles in the lives of Indigenous survivors of residential schools, and how, through passion and perseverance, they can reclaim their identity. My painting is meant to reflect the spirit of Saul Indian Horse — the protagonist of the novel — and his ability to find light and freedom through hockey despite his experiences of abuse and trauma. My artwork is meant to honour all Indigenous survivors, who continue to seek the peace and healing they deserve.

November 25, 2025

thevarsity.ca/category/science science@thevarsity.ca

For thousands of years, First Nations people have used tobacco, cedar, sage, and sweetgrass as medicinal compounds

grandmothers during the ceremony. Once brought inside, water is then poured over the glowing red rocks, filling the lodge with steam.

Cedar

Note: This article represents only a small portion of sacred Indigenous teachings and acknowledges the diversity of practices across communities and regions. For more information, consult a Traditional Elder, Healer, or Medicine Person.

For over 12,000 years, Indigenous peoples across the Americas have drawn knowledge from the medicinal properties of plants. The Four Sacred Plants — tobacco, cedar, sage, and sweetgrass — are honoured and burned by First Nations people in blessing and purification ceremonies as the way to “remember to remember” as Robin Wall Kimmerer describes in their book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. The burning is grounded in principles of respect, humility, and patience towards Mother Earth, reaffirming awareness of our relationship with the land, the ancestors, and the Creator.

The circle is the most sacred shape, uniting the important concepts of the Sacred Fire and the Four Sacred Medicines. The circular Medicine Wheel, Medicine Circle, or Mandala has also been used for time immemorial around the world as a map of the cosmos to conceptualize the interconnectedness of existence and cycles of life.

Smoke-based remedies allow for rapid delivery to the brain and greater absorption efficiency in the body, as airborne transmission is a significant route of infection for diseases. The sweat lodge ceremony, a sacred and ancient purification ritual practiced across the Americas, typically takes place in an enclosed dome structure in complete darkness to evoke the primordial darkness of a mother’s womb, or the ‘navel of the universe.’

Outside of the lodge, a respected Firekeeper tends to the Sacred Fire, serving as a spiritual bridge between the Creator and the ancestors. Stones are brought into the lodge in symbolic numbers, placed in the central pit, and greeted as grandfathers and

By bridging ancestral knowledge with concepts now known to modern pharmacology, modern sweat lodges seek to restore harmony in the body, mind, and spirit. Through prayers and songs, smoke is produced and sweating is induced for those in the lodge as the temperature increases. This promotes the absorption of plant-based compounds that support overall balance, wellbeing, and healing for the lungs, heart, and nervous system.

Every plant has a spirit. As the first of the sacred gifts given by the Creator, tobacco is understood as the main activator of all the plant spirits. The term tabako, or tobacco, originates from the TaínoArawak language of the circum-Caribbean islands and was appropriated by the Spanish in 1550 — an act of linguistic erasure foreshadowing centuries of cultural genocide.

For the Lokono-Arawak Eagle Clan in Northeastern South America, tobacco leaves are harvested only when they begin to turn brown, signalling that the plant no longer needs the leaves; picking green leaves harms the tobacco and is disrespectful. Among the Anishinaabeg of the Great Lakes region, when offered properly, tobacco binds truth and honesty to the smoke and completes the circle; as mentioned in a 2004 study published in the Journal of Holistic Nursing that interviewed traditional Indigenous healers, “If tobacco is not used in a sacred manner, the circle is broken and a disconnect occurs in relation to the culture.”

In Indigenous ceremonies, movements often follow a clockwise or ‘sunwise’ direction, in alignment with the cyclical rising and setting of the sun. In this context, a tobacco ceremony is a practice of ‘rituals of healing’: the fire burns and carries thoughts and prayers to the Spirit World, while also cleansing the air we breathe.

Historical displacement, cultural disruption, and structural inequities continue to shape health outcomes

The Tree of Life, or arborvitae, cedar is native to much of north-central and eastern Turtle Island. It is a protective medicine; its presence is heard in the crackle of a fire.

In Anishinaabemowin, the language of the Ojibwe, cedar is known as Grandmother Cedar or the Long-life Maker. Based on terms of respect and affection, the elderly are treasured and considered living libraries. Grandmother Cedar opens and maintains that line of communication.

When cedar leaves are cut and covered with boiling water, inhaling the steam produced stimulates blood flow in the lungs, enabling the absorption of more oxygen into the blood and removing waste. Nutrients flow more readily into lung tissue, whereas debris from fighting the infection is carried away. Cedar helps the body heal more quickly by acting as a mediator, creating a neutral space and assisting the immune system.

The genus Salvia, commonly referred to as sage, repels viruses and other negative energies to cleanse the spirit of harmful thoughts of a person or place. There has been an increase in mainstream medical interest in the antibacterial, antioxidant, antiinflammatory, and antitumor effects of sage. One 2017 pharmaceutical review in the Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine describes the plant as being highly effective in the ongoing development of novel drug candidates for the treatment of diseases such as diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

Found near rivers, lake edges, and wet meadows, sweetgrass is the sacred hair of Mother Earth. To gather sweetgrass is to enter into a relationship with it; the plant gives freely

Bruno Macia Varsity Contributor