Great Britain

A guide to Britain through its festivals

Ian Irvine on Colonsay

Michael Bundock on Lichfield

Lucy Deedes on Chiddingstone

Richard Osborne on classical music festivals

Listings of this year’s literary and arts festivals

April 2019 | www.theoldie.co.uk

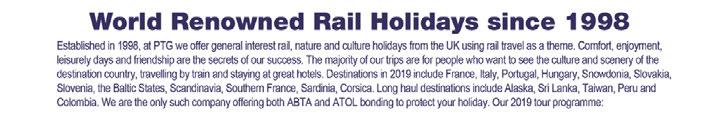

LICHFIELD

BIBURY

HARROGATE

Staffordshire Lichfield

Michael Bundock on the city where Samuel Johnson was born

If ever a city was associated with a particular writer, that city is Lichfield and that writer is Samuel Johnson. It’s true that the tourist tea-towels remind us of his best-known pronouncement, ‘If a man is tired of London he is tired of life’. But he probably never said any such thing, while he certainly did shoehorn a tribute to his native city into his Dictionary of the English Language. He defined ‘lich’ as ‘A dead carcass, whence, Lichfield, the field of the dead, a city in Staffordshire. Salve magna parens.’ (Hail great parent.)

Lichfield Tourist Office has been understandably slow to adopt the slogan ‘Field of the dead’, but among residents there is a tangible sense of civic pride in the local boy who made good in London. (‘Salve magna parens’ is now the motto of the City Council.) Johnson was born in Lichfield on 18th September 1709 and every September one weekend is devoted to celebrating the city and Johnson’s life, with music, readings, theatre, and a number of historic buildings open to the public. This year it takes place on 14th–15th September.

The focus of events is the house where Johnson was born, an imposing four-storey building on the corner of the marketplace. It was built by Johnson’s parents, Michael and Sarah Johnson in 1708 and is now the Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum. Michael Johnson ran a bookseller’s business from the ground floor, so it’s appropriate that the museum operates a secondhand bookshop in the same part of the building. A rather good one it is too – plenty of Johnson, of course, but whenever I have visited there have been excellent general stocks of literature and history as well. There’s something pleasing about being able to handle books in this setting rather

than searching soulless online catalogues.

The centrepiece of the weekend is the civic dinner organised by the thriving Johnson Society of Lichfield in the nearby Guildhall. Johnson scholars and enthusiasts gather with locals and civic dignitaries to mark the occasion with a little light steak and kidney pudding. Clay pipes are smoked, much punch is consumed, and an address is delivered to the assembled throng. (This year the honours are to be performed by the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams.)

The Birthplace Museum lies at the heart of the city, and the market still operates there as it did in the 18th century, with crates of fruit and vegetables leaning against the two contrasting statues which dominate the open space. One is of Johnson, massive, heavy, head on chin and deep in thought. The other is a jaunty James Boswell by the notoriously inept

Further Information

The Johnson Society (Lichfield)

https://johnsonnew.wordpress.com

Lichfield Literature Festival

7th–10th March 01543 306150

https://www.lichfieldfestival.org

Places to stay

The George Hotel 01543 414822

https://www.thegeorgelichfield.co.uk

Swinford Hall 01543 481494

https://swinfenhallhotel.co.uk

Places to eat

The Olive Tree 01543 410208

http://www.olivetreelichfield.co.uk

1709 The Brasserie 01543 257986

http://www.wine-dine.co.uk/1709

sculptor Percy Fitzgerald, who has conferred on Johnson’s biographer a remarkable snub nose.

The market occupies the space to the side of St Mary’s Church. The church now houses the city library and history centre, and it is possible to climb to a viewing platform in the spire to look out over the city centre and the surrounding countryside. One feature dominates the landscape for miles around: Lichfield Cathedral, with its famous three spires. (It is apparently the only three-spired medieval cathedral in the United Kingdom.)

The centre of the city is small, and it is a short stroll to the cathedral along a narrow lane lined with 18th-century houses. The contrast with the busy

marketplace is marked: the cathedral precincts are peaceful and largely traffic-free. The close is little changed since Johnson’s day, with the cathedral surrounded by substantial houses, one of which was at that time the Bishop’s Palace (now Lichfield Cathedral School).

Many people come to the cathedral to see the 8th-century St Chad Gospels or the stunning Lichfield Angel, a medieval sculpted panel discovered only in 2003. Last year these ancient artefacts were joined by a striking modern one when the icon Jesus Crucified, Risen and Lord of All, by a group of painters from Bethlehem Icon School, was suspended from the roof above the altar.

Far left, Samuel Johnson, 1772, by Sir Joshua Reynolds and, below, the Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum, with secondhand bookshop on the ground floor; left, celebrations at the Johnson Festival, below, Lichfield Cathedral

Tucked away in a side chapel are memorials to Johnson and to David Garrick, another Lichfieldian and Johnson’s former pupil. Garrick’s monument quotes Johnson’s words: ‘His death eclipsed the gaiety of nations, and impoverished the public stock of harmless pleasure.’ Not a bad tribute, for any actor. His local origins are also celebrated in the name of the Lichfield Garrick Theatre.

Just off the close is the former house of yet another Lichfield luminary, Erasmus Darwin, physician, poet and grandfather of Charles. Erasmus was the leading figure in the Lunar Society, a group of engineers, designers and experimenters whose members included Josiah Wedgwood, James Watt and Joseph Priestley. (Their story is celebrated in Jenny Uglow’s book The Lunar Men.) The house is now a museum commemorating Darwin’s life and the work of the group.

The Johnson commemoration weekend has taken place every year for over a century, but since 2006 there has been another annual literary celebration, the city’s book festival; this year it runs from 7th–10th March, with a range of writers talking about their work. Many of the events take place in the George Hotel, an old coaching inn which was known to Johnson.

Samuel Johnson never forgot the city of his birth. Forty years after leaving it he told John Wilkes, ‘I lately took my friend Boswell and showed him genuine civilised life in an English provincial town. I turned him loose at Lichfield.’

‘The Fortunes of Francis Barber: The True Story of the Jamaican Slave Who Became Samuel Johnson’s Heir’ by Michael Bundock is published by Yale University Press

What a palaver there was in December 1926 when Agatha Christie, the Queen of Crime, went missing from her home in Berkshire. It could have been a mystery from one of her books: The Case of the Missing Author! The world held its breath for 11 days as people hunted high and low for the celebrated spinner of tales. When, to the barely muffled sounds of huzzahs, she showed her face it was at the Old Swan Hotel in Harrogate, the spa town in the West Riding of Yorkshire; the sort of respectable place where murder mysteries unravel to the clacking of knitting needles, scoffing of scones and flower duties at the parish church.

Harrogate, home of Betty’s, the famous tea room once hymned by Alan Bennett in a BBC documentary, is better-known to the world beyond the Broad Acres as the town where Agatha Christie did a bunk, and what a boon that has proved. Living proof, one might say, of the time-honoured adage that, where murder is concerned, nothing is so shocking as a single body in the living-room of a vicarage.

Of all the events that make up the season of ‘international festivals’ in Harrogate the festival of crime writing is the most apposite. It is staged in the Old Swan Hotel, too, which adds a coat of authenticity. On 18th July they will gather there, thousands of eager readers from all over the globe, to buy books and listen to some of the best-known crime novelists. Last year more than 15,000 attended the festival. Little wonder that Lee Child, the king of current best-sellers, has dubbed it ‘the best in the world’.

It’s a stellar line-up. Val McDermid will be there, along with Nicci French, John Grisham and Don Winslow. Child, who has programmed the festival, will interview Grisham in the Royal Hall on 20th July. As they have sold hundreds of millions of books it is impossible to establish precedence. Either way sparks should fly.

The Old Swan basks in its notoriety. Besides hosting the crime writers, who must feel like masters of all they survey, for four days at least, the hotel also arranges ‘murder mystery events’ throughout the year. One that takes the eye is on 9th August – ‘Carry On Murdering’.

North Yorkshire

Harrogate

This spa town is host to more than 300 annual cultural events, as Michael Henderson discovers

Lucky actors who inhabit the parts of Kenneth Williams, Barbara Windsor and Charles Hawtrey… Luckier still the chap who summons the ghost of Kenneth Connor, and gets to say: ‘Damned filth!’

The international festivals, founded in 1966, when England’s footballers were running around Wembley with the World Cup, has been attracting visitors to Harrogate in ever greater numbers. More than 90,000 attended events in the town last year. There were 300 to choose from, so Harrogate is doing its bit for the cultural life of that part of Yorkshire, which is full of welleducated, well-heeled folk. ‘Outreach’ features prominently, as it does everywhere, even if nobody, other than box-tickers, knows what it means.

Few people reached out to audiences more successfully than

From top: Harrogate War Memorial, Bettys Café Tea Rooms and the Old Swan Hotel, Harrogate

those Victorian knights, William Schwenck Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan. The creators of the Savoy operas conquered the Englishspeaking world when Harrogate was establishing its reputation as a spa. Now it stages the annual International G & S festival (7th–18th August), while Buxton, another spa town, hosts the National G & S Opera Company (24th–29th July).

In August, once the crime writers have taken their daggers home, the Savoyards arrive by boat and plane ‘to dance a cachucha’ and everything else that gondoliers get up to when they imagine nobody is looking. There will be 40 shows this August as Harrogate, a staid and sensible place for 11 months, goes topsy-turvy for three giddy weeks. Oh, she’s gone and married Yum Yum...

There are many cherries to pick. July brings musicians of repute to the Royal Hall, which begs the overwhelming question: why does Yorkshire not boast a professional symphony orchestra when Manchester has three? The day will come, one hopes, when some brave soul grasps that nettle. Cultural provision is at least as important as, say, the Tour de Yorkshire, which is not to decry the Tour’s success.

In October there is a literary festival. Well, you feel such fools if you’re a spa town and you don’t have a literary festival when the leaves are turning, don’t you? Cheltenham may wear the crown when it comes to books in autumn, and that’s not going to change. But Harrogate is making its own contribution to the world of letters, rounding off another year of delight, outreach and education.

Sensible folk will, of course, take advantage of the fact that a Yorkshire brewery, Timothy Taylor of Keighley, supplies the greatest ale in the world. There’s no excuse for not supping a pint or two of Landlord bitter, or Boltmaker, should you prefer. In this respect, as in others, Yorkshire is the land of plenty.

Further information

The Old Swan Hotel

www.classiclodges.co.uk/our-hotels/ the-old-swan/ 01423 500055

Bettys Café Tea Room www.bettys.co.uk/ 01423 814070

For details of all festivals in Harrogate https://harrogateinternationalfestivals. com/festivals/ 01423 562303

Bibury Gloucestershire

Idyllic countryside and long walks followed by large slices of cake make the surrounding area irresistible, says Nigel Summerley

If it weren’t for Anne Boleyn, I probably wouldn’t have had one of the best pieces of chocolate cake I’ve ever tasted. Because the amazing Abbey Home Farm café, just outside Cirencester, wouldn’t have existed.

The chocolate almond cake served here is vegan and expensive – like much of the fare. But every scrumptious bite was worth it. Henry VIII’s desire for AB and resulting spat with Rome meant the confiscation of Cirencester Abbey land – and subsequently an opportunity, in 1564, for Elizabeth I to sell it to her physician, Richard Master. The land was used to establish a farm – which has stayed in his family to the present day.

And it’s now very green – its organic farm shop and café have green doors, green windows, green shelves and, if you missed the message, green shopping trolleys. In fact, it’s so green that it’s stopped stocking Ecover because, it says, that company’s refill bags-in-boxes can’t be reused. The

store sells wool from the farm’s own sheep and offers Sunday roasts: conventional, veggie or vegan.

‘But you need a Black Amex card to shop there,’ said a sharp-tongued chap from nearby Bibury. Not quite. The shop’s organic veg, handprinted duvets from Jaipur and assorted exotic knick-knacks are all on the pricey side; but they have to be to sustain this hidden gem, on a working farm tucked away up a skinny lane off the B4425.

Hidden gems – and cake – are major features of the seductive Cotswolds country around Bibury, the village whose iconic Arlington Row cottages launched a thousand photo shoots. After a lovely stroll through beech-lined avenues on the Sherborne Estate, just north of Bibury – National Trust-owned and offering a variety of walks in beautiful surroundings – I popped into Sherborne’s Village Shop. It’s an old-fashioned grocery store cum trendy café with a touch of mild chaos. The staff didn’t seem to quite know what they were doing; I wasn’t

Barnsley House Hotel, formerly the home of the late Rosemary Verey

NIGEL

Gloucestershire

sure which of a myriad menu boards to look at; and people were politely squeezing onto already-occupied tables... But the tea and the most sumptuous carrot cake were wonderful.

Cake always tastes better postwalking, and around here the scope for walking is unlimited. Westonbirt Arboretum is less than half an hour’s drive from Bibury, offering some of the finest and most varied woodland in the UK, from titanic sequoias to a serene grove of red cedars. And the recent addition of the – now de rigueur, it seems – treetop walk has given it another dimension, taking you on a safe and gentle amble into the air, suitable even for those with trepidation about heights.

Inevitably, Westonbirt draws the crowds. To be far from the madding parents, toddlers and buggies, take a footpath east from Bibury along the southern bank of the River Coln to the

lesser known village of Quenington. The adjectives green and pleasant don’t begin to do justice to this walk through trees and meadows accompanied by the river’s fast, clear water.

Quenington is a quietly charming Cotswold village that lacks – for good or ill – the equivalent of Arlington Row. The Keepers Arms here had no

Further information Bibury Literary Festival 23rd-24th March; www.biburyfestivals. com

Places to stay

The Catherine Wheel, Bibury; 01285 740250; www.catherinewheel-bibury. co.uk; from £75

The Dovecote, Pigeon House, Bibury; www.airbnb.co.uk; £198 Places to eat

The Village Pub, Barnsley; 01285 740421; www.thevillagepub.co.uk

The Village Shop, Sherborne; 01451 844668; www.sherbornevillageshop. com

Clockwise from top, Sherborne's Village Shop; garden at Barnsley House; dovecote at Pigeon House

food on offer, only crisps and nuts – and certainly no cake. So I had to double back to Bibury and settle for a well-deserved apple crumble at the Catherine Wheel pub.

For research purposes I also sampled the apple crumble at the archly named Village Pub in Barnsley, Bibury’s neighbour to the west. It was a close-run thing, but Barnsley won by its crumble.

Over the road from the Village Pub is its associated posh hotel, Barnsley House, based where the late Rosemary Verey used to live and incorporating her garden. It’s still a lovely place; but in the 1990s I had the honour of being shown round the garden by Verey herself and, without her formidable presence, it lacks the magic she wrought.

Verey was a friend of a less celebrated gardener, Doreen Kemp, who lived in Pigeon House at the east end of Bibury. And some of the plants that Verey donated to her are still growing here, tended by Steve and Wendy Hazelwood who bought the house – the oldest in Bibury, dating back to 1580 – after Kemp’s death.

As well as extensive renovations to the Grade II*-listed property, the Hazelwoods have converted the 17th-century dovecote in its grounds into a romantic B&B nest for couples. In the two years they’ve been renting it out, they claim there have been four marriage proposals in the place – so, be warned. On Airbnb it’s listed as the Hidden Dovecote.

Nearby stands Bibury’s St Mary’s Church, sturdily Saxon with Norman embellishments, and filled with architectural treasures. The hidden delight here is the brilliant stainedglass window tucked away in the north wall of the chancel and designed by Karl Parsons. The modernity of this Madonna and Child from 1927 was then controversial for its windswept Mary, looking like a tough mum bringing her baby into a turbulent world.

Talks that are part of Bibury Literary Festival 2019 will be held in the church and given by the likes of Sandra Howard, Angela Levin and Jane Ridley. And I’m told by the organisers that, yes, there will also be plenty of cake.

Inner Hebrides

Rare

Colonsay

birds and flora, deserted sandy beaches and woodland gardens are only some of the delights of this island, where

a literary

festival

is also held, writes Ian Irvine

It might seem challenging for a Hebridean island with only 120 residents and over two hours by ferry from Oban to hold a successful book festival, but that is far from the case. Colonsay may be remote, but it is not in the least culturally impoverished or isolated. It already boasts a bookshop, a publishing house, an art gallery, a brewery and two separate gin distillers. Started eight years ago its festival has attracted an impressive roster of guests, including many of Scotland’s leading writers, such as Ian Rankin, Liz Lochhead, Alexander McCall Smith, AL Kennedy, Janice Galloway, Candia McWilliam, James Buchan and Val McDermid. This year the detective writer Ann Cleeves heads the line-up. The festival takes place over a weekend and nearly doubles the island’s population. All events take place in either the village hall or the hotel. Even by the standards of most literary festivals, Colonsay’s is remarkably relaxed and convivial, more like ‘a literary lock-in’ as a previous director described it. But this annual weekend is only the most recent of the attractions of Colonsay.

When viewed on a map, the Hebrides seem a scatter of apparently undifferentiated islands of various sizes, but in fact they have remarkably individual characters created by geology and situation. Eight miles long by three miles wide, Colonsay is comparatively lush, impressively wooded in parts and with a benign micro-climate which means it is often several degrees warmer than the mainland, with low rainfall and long hours of sunshine in the summer.

Fertile and green it sustains almost 200 species of bird, including golden eagles and rare choughs and corncrakes, and 400 species of flora. There’s a population of feral goats, a thriving seal colony and otters in almost every bay. There are numerous

sandy coves – including the gorgeous wide sands of Kiloran Bay, one of Scotland’s finest beaches – and beautiful lochs for fishing the native brown trout. The woodland gardens of ‘the big house’, Colonsay House, are stocked with a wonderful range of trees and shrubs, including a famous rhododendron collection. There’s an 18-hole links golf course reputedly over 200 years old. Walking, climbing, fishing, bathing, golfing, birdwatching, bikes for hire: Colonsay naturally lends itself to traditional outdoorsy family holidays – children can be safely left to their own devices. There’s only one road round the island and traffic is – to say the least – infrequent.

For competitive visitors, mention must be made of the island’s equivalent of the mainland’s Munrobagging: McPhie-bagging. A Munro is any Scottish mountain over 3,000 feet, a McPhie is defined as any eminence in excess of 300 feet. There are 22 on the official list. The aim is to climb all of them and it can be done in a single day. The distance is around 20 miles and the current remarkable record is just under four hours.

One visitor to Colonsay last century

Only hotel on the island: Colonsay Hotel

was inspired to make a film about it, the wonderfully romantic I Know Where I am Going (1945) with Wendy Hiller and Roger Livesey. Its director, Michael Powell, was already a passionate aficionado of islands: he had made The Edge of the World in 1938 about the forbiddingly isolated Foula in Shetland. But Colonsay was something else. In 1944 it took him four days to get there from Glasgow: ‘The island had no jetty, and sent a boat out to meet the steamer. There was a comfortable little hotel, and we soon scrambled to a high point of the island, which was only 300 feet above sea level. From here the whole glorious panorama from Iona to Kintyre lay before us, and I shouted out that this wonderful land and seascape could be the only setting for our story. If I could only get a film unit up here, and somehow feed and lodge them, I knew that we would bring back a wonderful film. It wasn’t just the scenery, it was the feel of the place.’

I Know Where I’m Going eventually had to be shot on Mull for practical reasons, but it is filled with references to the island and its remoteness, and the difficulty in getting there provides much of the plot. But Colonsay remains as wonderful today as it was for Powell.

The 2019 Colonsay Book Festival will take place on the 27th and 28th of April. http://www.colonsaybookfestival.org.uk

Getting there

Travel to Colonsay starts in Oban, a two-hour drive from Glasgow, three hours from Edinburgh. There are several trains daily from Glasgow. From Oban Caledonian MacBrayne run daily ferries from April to October. November to March there are four ferries a week. Advance booking for cars recommended www.calmac.co.uk. Hebridean Air has two flights a week to Colonsay from Oban www.hebrideanair.co.uk

Places to stay

The very comfortable Colonsay Hotel is the only one on the island www. colonsayholidays.co.uk/hotel/. Most visitors stay in self-catering properties which are available to rent. There are apartments, sleeping from 2 to 6, in a wing of Colonsay House, the Georgian mansion, home of the island’s laird, Lord Strathcona, and cottages and houses which can accommodate up to 14 www.visitcolonsay.co.uk.

Places to eat

The Colonsay Hotel has a bar and dining room, offering snacks and full meals, using much of the island’s produce.

The Colonsay Pantry, close to the ferry pier, has great views across to Jura and is open for lunch and dinner. www.thecolonsaypantry.co.uk

Chiddingstone

Castles, stately homes and vineyards: Lucy Deedes on the charms of this rural area

Can you hear the people sing? Not exactly, but you might hear the faint scratching of a quill or the clacking of an ancient typewriter for here in West Kent there are ghosts of writers and the written-about all around us –Anne Boleyn and later Anne of Cleves at Hever Castle; the soldier poet Sir Philip Sidney at Penshurst Place, Winston Churchill painting by the fishpond at Chartwell and Vita Sackville-West enjoying her strange tomboyish childhood at Knole. It’s where Siegfried Sassoon spent long ecstatic hunting days with the Southdown and Eridge foxhounds and EM Forster suffered equally long miserable days at Tonbridge school.

Chiddingstone Castle, about to hold its fifth literary festival in May, is a short walk across the bridge from the photogenic Tudor village of Chiddingstone. The village is a sought-after film location and famously featured in A Room with a View. The castle itself started life as a timbered manor house and was much

augmented over the centuries, culminating in its ambitious reincarnation in the 19th century as a medieval castle by its owner Henry Streatfeild, and continued by his son Henry. These days, the rich might show off with a swanky car or a boat; back then, you made a bit of money and went with crenellations.

The house was a Canadian military base during the second world war, then a school, and was finally bought in 1955 by an impecunious bank employee called Denys Eyre Bower, who, wearying of bank clerkery, managed to get himself a 100 per cent mortgage and buy the Castle for £6,000, to house his eclectic and growing collection of art and artefacts and, charging half a crown entrance fee, display his treasures to the public. His enthusiasms were widespread: Buddhism; the Stuart dynasty, stemming from his Derbyshire childhood and obsession with Culloden and Bonnie Prince Charlie; ancient Egypt and Japan – his extraordinary Japanese lacquer

collection is the most important one outside the V & A.

He had a fondness for cars and women; two unsuccessful marriages, far from discouraging him, propelled him into a relationship with a much younger lady from Peckham who claimed to be an Italian Countess. In 1957 there was an unfortunate incident in South London involving the Countess, an antique pistol and a budgie cage, whereupon Mr Bower spent several years in Wormwood Scrubs for attempted murder and attempted suicide (he continued busily corresponding with the British Museum from prison) until his release was secured in 1962 by an intrepid solicitor called Ruth Eldridge, who proved that there had been a miscarriage of justice.

After his release he was painted by Laura Knight and this portrait, along with some of the quirky items from his life, can be seen in his characterful study in the castle. He offered the house to the National Trust before his death in 1977, but it declined; it is now run by a board of trustees, including Mark Streatfeild, a descendant of the original Henry, so that Bower’s collection can still be appreciated. Ask any child about the castle and they will tell you all about the mummified cat in the Egyptian collection, the Samurai suits of armour or possibly the segment of the heart of James II in the Stuart rooms.

This part of Kent was a densely forested area in the Neolithic era, which became criss-crossed with paths

where pigs were driven between dens for summer grazing. The dens soon turned into small scattered farming settlements and wool became the big thing. Then came iron ore, and by the late 16th century there were a hundred iron furnaces and forges, the iron production supported by local timber for charcoal and the quick flowing streams. But by the early 19th century the last of the heavy industries moved north to the coalfields and the blast furnaces fell silent.

Now it’s farms again: hops, apple, cherry and pear orchards and some 50 Kentish vineyards capitalising on the same soil type and growing conditions as the Champagne region.

Unsurprisingly, the Weald is an Area of Outstanding National Beauty covering 560 square miles: the dips and valleys, the scrubbly hedges, patchwork fields and sunken lanes and the historically scattered farmsteads make it appear much less populated than it really is and the unimproved grassland means that crickets, bumblebees and wildflowers thrive, including the prized greenwinged orchid.

The literary festival in the castle

Further information

Chiddingstone Castle Literary Festival runs from 4th–7th May

https://www.chiddingstonecastle.org.uk/ literary-festival/ Places to stay:

The Leicester Arms Hotel, Tonbridge, Kent TN11 8BT

https://www.theleicesterarmshotel.com/ 01892 871617

The Hever Hotel, Hever, Edenbridge, Kent TN8 7NP reservations@heverhotel.co.uk 01732 700700

and its grounds has now become a four-day bank holiday (May 4th–7th) programme of readings, talks, workshop and theatre.

You can hear Oz Clarke on food and drink; Joanne Harris talking about The Strawberry Thief, her new Chocolat novel; the Guardian’s Jon Crace talking politics and Brexit with ITN Five News’s Andy Bell; Anna Pasternak considering the parallels between Wallis Simpson and Meghan Markle. Anthony Seldon, contemporary historian, educationalist and thought-provoker, will discuss British prime ministers, and Tom Gregory, author of Boy in the Water, will talk about his extraordinary experience of swimming the Channel as a boy of 11. There will be insights into real life crime with forensic scientist Angela Gallop and barrister Thomas Grant.

Bank Holiday Monday is Family day when everybody’s Gogglebox favourites Giles Wood and Mary Killen share their gently barbed philosophies on life and marriage. Tuesday will be schools day, with children’s theatre and workshops for writing and model-making.

When there’s a moment take some time to look at Denys Eyre Bower’s very individual collection and check out the Orangery for its gorgeous award-winning gridshell roof, made from curved green chestnut lathes and a floating grass frame – an inspired combination of old and new.

It’s expected now that writers will not only entertain us on the page but also appear before us in the flesh. We ask a good deal of them and, fortunately, they indulge us.

Chiddingstone Castle delights: mummified cat and gardens

South-West England

Home of well-heeled students, the graffiti artist Banksy and the foodie capital of Britain, Bristol is considered one of the most youthful cities in Britain. But it is also a richly historic place with a mighty seafaring past, a formidable Georgian inheritance, and a mighty industrial legacy. The last due in large part to the genius — no other word will do — of the engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859).

Brunel’s Grade I-listed Temple Meads station is one of the most important railway sites in the world. In the mid-19th century one could travel on his railway from Paddington, take a carriage to the harbour at Bristol and set sail on his pioneering iron ship (SS Great Britain) arriving in New York 14 days later. Brunel’s famous Clifton Suspension Bridge, completed in 1864 after his death, spans the Avon George. The bridge — circled by peregrines — is a great place to watch the hundreds of hot air balloons at the annual International Bristol Balloon Festival (to be held this year from 9th–11th August), an event Brunel would have adored.

Bristol is as much a city of culture as of technology. The exceptionally pretty Bristol Old Vic — recently fully

Bristol

This historic city has so much to offer – with its culture, technology, food and much else, writes Robert GoreLangton

restored — is Britain’s oldest working theatre, built in 1766. It resides on King Street. A century earlier Pepys wandered here, finding the nearby quay ‘a most large and noble place’. It was a foodie city even back then. Pepys enjoyed a repast of venison pasties, strawberries and Bristol milk sherry — now known as Bristol cream. Almost opposite the theatre is the ancient Llandogger Trow inn. Daniel Defoe met castaway Alexander Selkirk there, his inspiration for Robinson

Crusoe. The pub was also the model for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Admiral Benbow Inn in Treasure Island. The stinking nature of the docks and the city caused the rich folks to flee to what is now Clifton, famous for its high-altitude terraces of Regency splendour: Royal York Crescent is the longest of its type in Europe. The city is full of Georgian literary associations, though these are often overlooked, upstaged perhaps by nearby Bath’s association with Jane Austen and Mary Shelley.

It was the poet Robert Southey who introduced Coleridge to the Bristol Library, and who encouraged him to give his Bristol lectures in 1795. The two poets had a high old time. They drank together and they married the Fricker sisters in Redcliffe where the enormous spire of St Mary’s dominates the south of the city. They also joined in some hilarious experiments with nitrous oxide (laughing gas) at the premises of Humphry Davy — of miner’s lamp fame — at the Pneumatic Institute, still standing in Dowry Square.

William and Dorothy Wordsworth stayed at the house of merchant John Pinney in 1795, now the Georgian House Museum (open from 1st April), a perfect example of a top-end

South-West England

18th-century city dwelling complete with plunge pool in the basement. It was here that Coleridge met Wordsworth, the start of a great and productive friendship. Their joint venture Lyrical Ballads (1798) was published in Bristol and created a revolution in English poetry.

Half of what was built in Bristol

Further information

Bristol Festival of Literature October 18th–27th October

Camra Beer Festival 21st–23rd March

200 different beers in The Passenger Shed, Temple Meads

Bristol Film Festival 8th–15th March

Venues all around the city

St Paul’s Carnival 6th July

Bristol’s version of the Notting Hill carnival, celebrating all things Caribbean

Bristol Harbourside Festival 19th–21st July. A massive event with music, food, drink and aquatic events

The Downs Festival 31st August

Noel Gallagher heads the bill is a rock festival on the Downs

Stay at

Brooks Guest House

came from the profits of sugar plantations and the foul trade that still causes controversy in the city. Many people gave speeches denouncing slavery. One vociferous opponent was John Wesley, whose chapel, New Room, built in 1739, is an oasis of wooden calm in Horsefair. It’s the oldest Methodist building in the

hidden away slap in the middle of town in St Nicholas Street BS1 www.brooksguesthousebristol.com 0117 930 0066

Hotel du Vin

Amazing views from this Clifton hotel, Sion Hill, BS8. www.hotelduvin.com 0117 403 0210

Eating out

Wilson’s

Small new restaurant in Redland with a great reputation 24 Chandos Road, Bristol, BS6 0117 973 4157

Poco’s Tapas Bar

The best tapas in Bristol Jamaica Street, Bristol BS2 www.pocotapasbar.com 0117 923 2233

Left, 19th-century print of Clifton Suspension Bridge; below, Bristol Temple Meads Station

world. It has rooms above the congregation where Wesley and visiting preachers slept. Today the chapel houses an unexpectedly charming museum of Methodism.

In fine weather, the whole of Bristol seems to descend on the docks. The Floating Harbour, built in 1809, impounded the tidal Avon to allow visiting ships to remain afloat all the time. Over the next two centuries it became a teeming commercial port. Having closed as a commercial harbour in 1975, it is now back with a vengeance. Luxury apartments are going up everywhere. A ferry service does trips around from the Cumberland basin and there’s a huge industrial museum (M-Shed) on the waterfront, not far from the betterknown Arnolfini contemporary art gallery. The area is alive with boatyards, industrial cargo units — stacked containers — that are home to dozens of little eateries and shops run by passionate hipsters.

You can’t help pondering on Bristol’s connection with the wider world when ambling along the waterside. Disused railways lines, ancient goods trucks and old steam cranes — like fat grey herons — are still to be seen. Often in dock is the replica of the Matthew, the tiny ship sailed by John Cabot (he was born Giovanni Caboto and, like Brunel’s father, he was an immigrant) from Bristol to Newfoundland in 1497. In pride of place is the Great Britain, now an award-winning floating museum. The ship was designed in 1843 and modestly dubbed ‘the greatest experiment since the Creation’. A screw and sail propelled vessel, she was the first iron steamer to cross the Atlantic. The smell on longer trips must have been worse than Noah’s ark. On one voyage to Australia the ship carried 133 live sheep, 38 pigs, 2 bullocks, 1 cow, 420 chickens, 300 ducks, 400 geese and 30 turkeys.

That lot puts one in mind of the city’s eating frenzy, Bristol Food Connections (12th-23rd June), a festival that fills the city with delicious aromas. Bristol is as beautiful as it is fascinating — and a great place to be peckish in.

Londonderry

Tourists stayed away during the Troubles but now they’re back again to marvel at one of the most spectacular walled cities in Europe, writes William Cook

I’m standing on the ancient walls of Londonderry, amid a crowd of sightseers, watching the marching bands of the Apprentice Boys Parade, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘Blimey! How this place has changed!’ When I first came here, in 1994, this was a city under siege. The IRA and their Loyalist adversaries were still active. Paramilitary murder was routine. No one here would have dared to dream the Good Friday Agreement was just a few years away. The fragile peace that followed has now lasted 21 years, and during that time this historic city has been transformed.

I’d been back here several times in the intervening years – not enough to know Derry well, but enough to see how much it’s altered. New shops and cafés have sprung up, old buildings have been spruced up, but above all it’s the mood that’s shifted. After 30 years on the front line of a virtual civil

war, Derry feels like a place that’s waking up from a bad dream.

The new Peace Bridge across the River Foyle is the boldest manifestation of this seachange, linking the (mainly Protestant) Waterside with the (mainly Catholic) city centre. For locals this bridge is symbolic, but also practical. For visitors, the big peace dividend is that you can now walk around the walls. Tourists stayed away during the Troubles, but now they’re back again, to marvel at one of the most spectacular walled cities in Europe.

These walls are integral to the troubled story of this city, and the parade I’ve come to see today. As oldies may already know, on 18th December 1688 13 apprentices shut the city gates against the Jacobite army of James II. The resultant siege lasted four months, thousands died of hunger, and since 1689 the relief of that savage siege has been marked by

a parade of marching bands, on the second Saturday in August every year.

Inevitably, this Protestant parade was a focus for tension during the Troubles, but whatever went on before, today it feels like a cultural celebration rather than Sectarian triumphalism. For me, it sums up how Derry has been reborn. What was once a warzone has become a weekend destination, one of the most attractive cities in Ireland – or the British Isles.

For any newcomer to this embattled city, the first problem is what to call it. Originally called Derry (by Irish Catholics), it was renamed Londonderry (by British Protestants) when it was granted to British planters in 1613. Officially it’s still Londonderry, but colloquially it’s more often Derry, maybe because Derry is less of a mouthful. There’s no easy answer to this dilemma, save to try to take your cue from whoever you end up talking to.

County Londonderry

A walk around the walls is a great way to get your bearings. The Catholic Bogside lies down below, marked by some stunning murals. You Are Now Entering Free Derry proclaims a sign on a gable wall. In 1972 this was the site of Bloody Sunday, when British paratroopers killed 13 unarmed, innocent civilians. The Free Derry Museum documents this tragedy, and the harrowing events that surround it. The Tower Museum provides a wider view of this sombre story.

After all that blood and thunder, Saint Columb’s Cathedral is a peaceful respite. Built in 1633, it’s a beautiful building, full of relics of Derry’s turbulent past, including a cannonball from the siege. It’s a parish church as well – no wonder it feels so homely. How nice to discover that Cecil Frances Alexander, who wrote Once in Royal David’s City, There Is A Green Hill Far Away and All Things Bright & Beautiful, used to worship here.

I was back in Derry for FrielFest, an annual celebration of the work of the great Irish playwright, Brian Friel. Born in Omagh in 1929, Friel spent the first half of his long life in Northern Ireland, and the second half in the Republic. Perched on the Irish border, Derry is a perfect spot to perform his plays, and the work of other writers who inspired him.

This festival is the brainchild of Sean Doran, an affable theatre director who grew up in Derry. His company, Arts over Borders, mounts plays in unusual venues, in places with shared identities. On the walls of Derry I heard Niall Cusack recite The Iliad (Friel loved Homer) against a background din of drums and flutes, overlooking the Bogside.

The Peace Process has reunited Derry with its natural hinterland, Friel’s adopted Donegal. It’s only a few miles away, but in the bad old days crossing the border used to be a bore. Nowadays it’s easy – so easy, you hardly notice. On Killahoey Beach in County Donegal, we heard Maxine Peake recite The Odyssey, Part Two. On Magilligan Beach in County Londonderry, we heard Imogen Stubbs recite The Odyssey, Part Four.

These are rehearsed readings rather than full-blown performances, but Doran books some big names. In the pretty seaside town of Moville, we saw Stanley Townsend and Orlad Charlton enact Friel’s The Yalta Game,

but the highlight of my trip was seeing Lorcan Cranitch, Tamsin Greig and the mesmeric Alex Jennings enacting Friel’s dark masterpiece, Faith Healer, in four different venues around Glenties. Glenties is the model for Ballybeg, the fictional village where Friel set so many of his plays. Instead of interval drinks, we shared a barbecue on Portnoo Pier in Inishkeel.

Further information

The City Hotel, Londonderry

This is a comfy modern four-star hotel in an ideal location in the city centre, with an indoor swimming pool and a rooftop terrace overlooking the River Foyle. Doubles from £82 in April (www.cityhotelderry.com)

This year’s FrielFest runs from 5th to 18th August 2019.

For more information, visit www. artsoverborders.com

We finished up in Greencastle, where Friel ended his days. After a spot of lunch in a fantastic little seafood restaurant called Kealy’s, I walked along the waterfront, past a windswept children’s playground, to the ruined castle that gave Friel’s last resting place its English name.

Looking out towards the wide Atlantic it felt like standing on the edge of nowhere, but County Londonderry was just a short ferry ride away, across the bay.

There’s a sobering postscript to this story. A few days after I filed this report, dissident Republicans detonated a car bomb outside Derry’s neoclassical courthouse. Mercifully, no one was hurt. Does this invalidate what you’ve just read? I don’t think so. Derry has changed tremendously since I first came here, at the tail end of the Troubles. I feel safer now in Londonderry than I do in London. But it’s a reminder that peace here is a process, not a settled state.

Opposite, Londonderry city walls; top, Peace Bridge; and, below, Bogside murals

Classical music Forward thinking

Richard Osborne looks ahead to this year’s classical music and opera

festivals

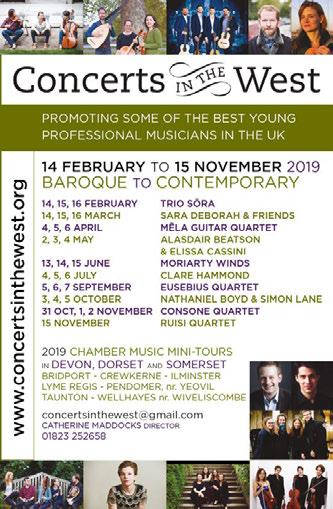

Our first swallows will probably arrive with our first festival, the Ludlow English Song Weekend on 5th–7th April. Early in the season, weekend festivals work well, witness the Carducci Quartet’s weekend of chamber music at Highnam Court near Gloucester on 17th–19th May or the English Music Festival which takes place in Dorchester-on-Thames over the May bank holiday (24th–27th May, booking 15th March).

This year an unusually late Easter may find pilgrims already afoot, possibly deep in Betjeman country in North Cornwall where Easter Week brings the St Endellion Easter Festival of choral and chamber music (13th–21st April). Too chilly? Well, St Endellion has a summer festival of choral music and opera too (30th July–9th August, booking 10th June).

Larger jamborees begin in the fortnight of 11th–25th May with the Newbury Spring Festival and the Chipping Campden Festival whose highlights include Handel’s Israel in Egypt and Chopin’s First Piano Concerto with 2018 Leeds piano competition winner Eric Lu.

Early Music festivals also begin early. Visitors to the prestigious London Festival of Baroque Music (10th–18th May) include Jordi Savall with his Hesperion XXI and a distinguished baroque ensemble from Lyons celebrating one of 17th-century Venice’s most colourful composers, Barbara Strozzi. Further north there is the Beverley Early Music Festival (24th–26th May) and its bigger brother the York Early Music Festival (5th–13th July, booking 4th March) which this year features music associated with that

innovator supreme Leonardo da Vinci (5th–13th July, booking 4th March).

In 1962 counter-tenor Alfred Deller founded Stour Music in his home village of Boughton Aluph in Kent, bringing such pioneers of the Early Music movement as Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt to perform in the local pilgrim church. After 45 years in charge, son Mark Deller steps down with a celebratory programme of Early and English music. Guests include Trevor Pinnock, The Sixteen, and I Fagiolini with their staging of Monteverdi’s Orfeo (21st–30th June, booking 1st April).

Followers of new and experimental music are spoilt for choice. The imperturbably whacky Brighton Festival (4th–26th May) is curated this year by the Malian singer-songwriter Rokia Traoré whose epic celebration of the ancient art of the griots of West Africa will be re-enacted. The Vale of Glamorgan Festival of new and contemporary music marks its 50th anniversary with a retrospective of the work of composer–pianist Graham Fitkin, along with two fascinatingly planned chamber-music evenings by the gifted young Berlin-based Armida Quartet (18th–24th May).

The Aldeburgh Festival, cocurated by Mark Padmore and Austrian composer Thomas Larcher, will stage the UK premiere of Larcher’s The Hunting Gun (7th–23rd June).

Later in the summer the modernist-minded Presteigne Festival on the Welsh border will be staging Stephen McNeff’s The Burning Boy, a Britten-style ‘miracle play for music theatre’ with a characteristically roistering libretto by the late Charles Causley (22nd–27th August, booking 30th April). Meanwhile, the more traditionally minded Gregynog Festival (22nd–30th June) will be extending to Aberystwyth where in 1919 festival founder Walford Davies launched initiatives that

Above, Rokia Traoré (Brighton), left, Carducci Quartet (Highnam Court), below, Eric Lu (Chipping Campden)

Classical music

would change forever the face of Welsh music.

For travellers looking to go further afield as midsummer nears with long days and short nights, there’s Scotland’s Fife coast where this year the East Neuk Festival (26th–30th June) hosts two of the world’s finest string quartets. Or Orkney for the music-rich St Magnus Festival in venues ranging from a three-masted Norwegian barque to the medieval cathedral of St Magnus itself (21st–27th June, booking March).

Holiday destinations for operalovers tend to be abroad, to where Brexit may consign the Wexford Festival Opera in south-east Ireland, a much-loved place of pilgrimage for those in search of operatic rarities staged with understanding and style. This year’s festival (22 October-3 November, booking 13 April) has Vivaldi’s Dorilla in Tempe, a little known one-act opera by Rossini, and Massenet’s Don Quichotte among its attractions.

The annual opera, music and book festival in Buxton in Derbyshire is a similarly pleasing holiday destination. Its programme includes a pasticcio on the life of Georgiana, 5th Duchess of Devonshire using music by Linley, Mozart and Mozart’s good friend Stephen Storace (5th–21st July, booking 6th April). Coincidentally Storace’s comedy about a pair of mismatched newlyweds Gli sposi malcontenti (Vienna, 1785) is being staged (in English) by Bampton Classical Opera in the Deanery Garden, Bampton near Oxford (19th–20th July) and The Orangery, Westonbirt School (26th August).

For visitors to London, Opera Holland Park (4th June–9th August) has a largely Italian season in its canopied theatre in Kensington, with Cilea’s L’arlesiana as the rarity item.

Country house opera famously provides the perfect deluxe excursion, though stretched resources and an ever-expanding market are causing standards to wobble, even at Glyndebourne (18th May–25th August, booking 3rd March) where revivals of proven productions – try Handel’s Rinaldo or Dvořák’s Rusalka – can be the safer bet. Garsington Opera is arguably the most consistent of the festivals artistically. Their season includes new productions of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride, Britten’s The Turn of the Screw and, in his bicentenary year, Offenbach’s neglected but much admired Fantasio (29th May–26th July, booking 19th March).

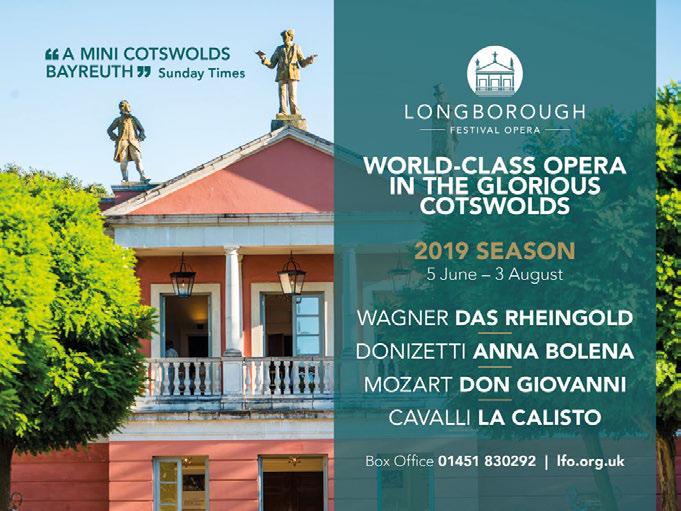

Famed for its Wagner Longborough Festival Opera (5th June–3rd August, booking 4th March) launches a new Ring cycle with Das Rheingold, though Donizetti lovers (a formidable tribe) will be thrilled to see Anna Bolena on the programme.

Further information

Ludlow English Song Weekend

ludlowenglishsongweekend.com

Carducci at Highnam carducciquartet.com

English Music Festival

englishmusicfestival.org.uk

St Endellion Festivals endellionfestivals.org.uk

Newbury Spring Festival newburyspringfestival.org.uk

Chipping Campden Festival campdenmusicfestival.co.uk

London Festival of Baroque Music lfbm.org.uk

Beverley Early Music Festival ncem.co.uk/bemf

York Early Music Festival ncem.co.uk/yemf

Stour Music stourmusic.org.uk

Brighton Festival brightonfestival.org

Vale of Glamorgan Festival valeofglamorganfestival.org.uk

Aldeburgh Festival snapemaltings.co.uk

Presteigne Festival presteignefestival.com

Gregynog Festival gwylgregynogfestival.org

East Neuk Festival eastneukfestival.com

St Magnus Festival stmagnusfestival.com

Wexford Festival Opera wexfordopera.com

The Buxton Festival buxtonfestival.co.uk

Bampton Classical Opera bamptonopera.org

Opera Holland Park operahollandpark.com

Glyndebourne Opera glyndebourne.com

Garsington Opera garsingtonopera.org

Longborough Festival Opera lfo.org.uk

Dorset Opera Festival dorsetopera.com

Grange Park Opera grangeparkopera.co.uk

The Grange Festival thegrangefestival.co.uk

West Green House Opera westgreenhouseopera.co.uk

Cheltenham Music Festival cheltenhamfestivals.com

Three Choirs Festival 3choirs.org

Edinburgh Festival eif.co.uk/edfringe.com

North Norfolk Music Festival northnorfolkmusicfestival.com

The Cumnock Tryst thecumnocktryst.com

Oxford Lieder Festival oxfordlieder.co.uk

Top: Jordi Savall and Hesperion (London), above, Fantasio (Garsington), and Gli sposi malcontenti (Bampton )

Charabancs may also have been booked for Dorset Opera’s staging of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor at Bryanston School near Blandford Forum (23rd–27th July, booking 5th March).

Grange Park Opera’s third season in its new ‘theatre in the woods’ in Surrey (6th June–11th July) will have its own trip to the woods with Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel, whilst The Grange Festival in Hampshire (no relation) goes for gold with Mozart’s Figaro and Verdi’s Falstaff (6th June–6th July, booking 5th March). Also in Hampshire, West Green House Garden Opera (20th–28th July) has Rossini’s richly inventive comic melodrama L’inganno felice as its annual one-act rarity.

July brings the Cheltenham Music Festival (5th–14th July, booking 8th March) and the Three Choirs Festival (Gloucester, 26th July–3rd August, booking 24th April) which marks the sesquicentenary of Berlioz’s death with a Three Choirs speciality La Damnation de Faust. The Edinburgh Festival (2nd–26th August, programme 27th March) and Fringe dominate August, though if you’re holidaying on the Norfolk coast, consider dropping in on the North Norfolk festival of chamber music and song in South Creake (9th–17th August, booking 1st April).

Before the clocks go back, there is Cumnock Tryst in East Ayrshire (3rd–6th October, booking early June) run by Sir James MacMillan, 60 this year, and the now indispensable Oxford Lieder Festival (11th–26th October, booking 31st May). ‘Tales of Beyond: Magic, Myths and Mortals’ will be this year’s theme with song cycles by Schubert, Mussorgsky, Vaughan Williams and Richard Strauss.

Literary and arts listings 2019

March

18th Aldeburgh Literary Festival

Suffolk, until 3 March

www.aldeburghbookshop.co.uk

Essex Book Festival

Throughout March www.essexbookfestival.org.uk

Harrogate Spring Sunday Series

Various dates, March–April www.harrogateinternationalfestivals. com

University of East Anglia Literary Festival

Norwich, various dates, March-May www.uea.ac.uk/litfest

StAnza International Poetry Festival

St Andrews, Scotland, 6–10 March www.stanzapoetry.org

Lichfield Literature Festival Staffordshire, 7–10 March www.lichfieldfestival.org

Words by the Water Keswick, Cumbria, 8–17 March www.wayswithwords.co.uk

Aye Write! Glasgow, 14–31 March www.ayewrite.com

The King’s Lynn Fiction Festival Norfolk, 15–17 March www.lynnlitfests.com

Spring Weekend Festival Wimbledon, 15–17 March www.wimbledonbookfest.org/

York Literature Festival 15–31 March www.yorkliteraturefestival.co.uk

International Radio Drama Festival Canterbury, 18–22 March www.radiodramafestival.org.uk

Huddersfield Literature Festival 21–31 March www.huddlitfest.org.uk

Alderney Literary Festival

Channel Islands, 29–31 March www.alderneyliterarytrust.com/ events

Oxford Literary Festival

30 March–7 April www.oxfordliteraryfestival.org

April

Laugharne Weekend

Carmarthenshire, 5–7 April www.thelaugharneweekend.com

Cambridge Literary Festival 5–7 April www.cambridgeliteraryfestival.com

Books by the Beach, Scarborough 11–14 April www.booksbythebeach.co.uk

Chipping Norton Literary Festival Oxfordshire, 24–28 April www.chiplitfest.com

Cheltenham Poetry Festival 26 April–4 May www.cheltenhampoetryfest.co.uk

Hexham Book Festival

Northumberland, 26 April–5 May www.hexhambookfestival.co.uk

Colonsay Book Festival Hebrides, 27–28 April www.colonsaybookfestival.org.uk

Stratford-upon-Avon Literary Festival

28 April–5 May www.stratfordliteraryfestival.co.uk

May

Brighton Festival 4–26 May www.brightonfestival.org

Swindon Festival of Literature 6–19 May

www.swindonfestivalofliterature. co.uk

Chipping Campden Literature Festival

Gloucestershire, 7–11 May www.campdenlitfest.co.uk

Boswell Book Festival

Dumfries House, Ayrshire, 10–12 May www.boswellbookfestival.co.uk

Caitlin Hulcup (Grange Park Opera)

Literary and arts festival listings 2019

Ullapool Book Festival Scotland, 10–12 May www.ullapoolbookfestival.co.uk

The Norfolk & Norwich Festival 10–26 May www.nnfestival.org.uk

Althorp Food and Drink Festival 11–12 May https://spencerofalthorp.com/ althorp-festivals

The Fowey Festival of Words & Music Cornwall, 11–18 May www.foweyfestival.com

Newbury Spring Festival Berkshire, 11–25 May www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk

Sandstone Ridge Festival Cheshire, 16–19 May

Oldie Literary Lunch 17 May at Cholmondeley Castle www.sandstoneridgefestival.co.uk

The Bath Festival 17–26 May www.bathfestivals.org.uk

Charleston Festival East Sussex, 17–27 May www.charleston.org.uk

Hay Festival

Hay-on-Wye, Wales, 23 May–2 June www.hayfestival.com

University of Aberdeen May Festival 24–26 May www.abdn.ac.uk/mayfestival

Islay Festival of Music and Malt Scotland, 24 May–1 June www.islayfestival.com

Chichester Cathedral Flower Festival

30 May–1 June https://worldloveflowers.com

Red Rooster Festival

Euston, Suffolk, 30 May–1 June www.redrooster.org.uk

June

Rochester Dickens Festival Kent, 1–2 June www.rochesterlitfest.com

Borris House Festival of Writing and Ideas

Carlow, Ireland, 7–9 June www.festivalofwritingandideas.com

Sidmouth Literary Festival 7–9 June www.sidmouthlitfest.co.uk

Bedford Park Festival Chiswick, London, 7–23 June www.bedfordparkfestival.org

Isle of Wight Music Festival 13–16 June https://isleofwightfestival.com

Borders Book Festival Melrose, Scotland, 13–16 June www.bordersbookfestival.org

Winchester Writers’ Festival Hampshire 14–16 June www.writersfestival.co.uk

Festival of Chichester West Sussex, 15 June–14 July www.festivalofchichester.co.uk

Farley Music Festival Wiltshire, 18–23 June www.farleymusic.co.uk

Edinburgh International Film Festival 19–30 June www.edfilmfest.org.uk

RS Thomas Festival Aberdaron, Wales, 20–23 June www.rsthomaspoetry.co.uk

Broadstairs Dickens Festival Kent, 21–23 June www.broadstairsdickensfestival.co.uk

Hebden Bridge Arts Festival

West Yorkshire, 21–30 June www.hebdenbridgeartsfestival.co.uk

Ashbourne Festival Derbyshire 21 June–7 July www.ashbournefestival.org

Yorkshire Sculpture International Leeds, Wakefield 22–29 June www.yorkshire-sculpture.org

Chalke Valley History Festival

Wiltshire, 24–30 June www.cvhf.org.uk

Big Malarkey Festival of Children’s Literature Hull, 26–30 June www.thebigmalarkeyfestival.com/ July

Penzance Literary Festival Cornwall, 3–6 July www.pzlitfest.co.uk/

Frome Festival Frome, 5–13 July www.fromefestival.co.uk

Ledbury Poetry Festival Herefordshire, 5–14 July www.poetry-festival.co.uk

Ways With Words Festival

Dartington Hall, Devon, 5–15 July www.wayswithwords.co.uk

Buxton International Festival Derbyshire, 5–21 July www.buxtonfestival.co.uk

John Clare Society Festival Helpston, Northants, 12–14 July johnclaresociety.wordpress.com

West Cork Literary Festival Bantry, Cork, 12–19 July www.westcorkmusic.ie/literaryfestival

Petworth Summer Festival

West Sussex, 16 July–3 August www.petworthfestival.org.uk

Latitude

Southwold, Suffolk, 18–21 July www.latitudefestival.com

Literary and arts festival listings 2019

Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival

Harrogate, 18–21 July www.harrogateinternationalfestivals. com/crime-writing-festival/

BBC Proms 2019 Season

London, 19 July–14 September www.bbc.co.uk/proms

Fishguard International Music Festival

Wales, 20 July–2 August www.fishguardmusicfestival.co.uk

Holt Festival

Norfolk, 21–27 July www.holtfestival.org

National Gilbert & Sullivan Opera Company

Buxton, 24–29 July www.gsfestivals.org

Port Eliot Festival

Cornwall, 25–28 July www.porteliotfestival.com

Dartington International Summer School and Festival

Devon, 27 July–24 August www.dartington.org/summer-school

August

Arts Over Borders Summer Festivals

Derry, Donegal, Enniskillen 1–19 August www.artsoverborders.com

Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2–26 August www.edfringe.com

Edinburgh International Festival 2–26 August www.eif.co.uk

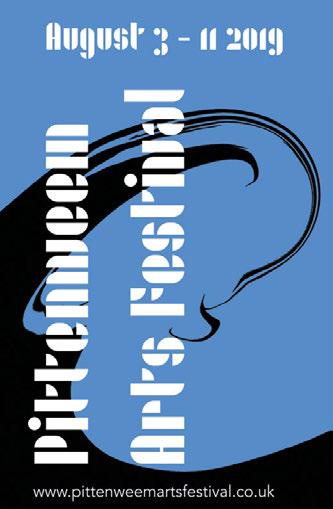

Pittenweem Festival

Fife, 3–11 August www.pittenweemartsfestival.co.uk

International Gilbert & Sullivan Festival Harrogate, 7–18 August www.gsfestivals.org

Llangwm Festival Pembrokeshire, 9–11 August www.llangwmlitfest.co.uk

Rockers Reunited Buxton Blues Festival Derbyshire, 9–12 August www.rockersreunited.co.uk

Edinburgh International Book Festival 10–26 August www.edbookfest.co.uk

Purbeck Valley Folk Festival Dorset, 15–18 August www.purbeckvalleyfolkfestival.co.uk

Curious Arts Festival

Pippingford Park, East Sussex, 23–26 August www.curiousartsfestival.com/

September

Nairn Book and Arts Festival Scotland, 10–15 September www.nairnfestival.co.uk

Chiswick Book Festival London, 12–16 September www.chiswickbookfestival.net

Worcester Music Festival 13–15 September www.worcestermusicfestival.co.uk

St Ives September Festival Cornwall, 14–28 September www.stivesseptemberfestival.co.uk

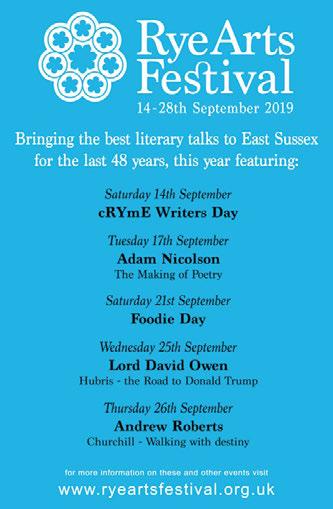

Rye Arts Festival East Sussex, 14–28 September www.ryeartsfestival.co.uk

Budleigh Salterton Literary Festival Devon, 18–22 September www.budlitfest.org.uk

Graham Greene International Festival Berkhamsted, 19–22 September www.grahamgreenefestival.org

Appledore Book Festival Devon, 20–28 September www.appledorebookfestival.co.uk

Wigtown Book Festival Scotland, 27 September–6 October www.wigtownbookfestival.com

Humber Mouth Literature Festival Hull, Dates tbc http://humbermouth.com/

Marlborough Literature Festival Wiltshire, 26–29 September www.marlboroughlitfest.org

Bath Children’s Literature Festival 27 September–6 October www.bathfestivals.org.uk/childrensliterature

Cliveden Literary Festival Buckinghamshire, 28–29 September www.clivedenliterayfestival.org

Warwick Words History Festival Warwickshire, 30 September–6 October www.warwickwords.co.uk

October

Birmingham Literature Festival 3–13 October www.birminghamliteraturefestival.org

Wimbledon Bookfest London, 3–13 October www.wimbledonbookfest.org

Times Cheltenham Literature Festival Gloucestershire, 4–13 October www.cheltenhamfestivals.com/ literature

Ilkley Literature Festival West Yorkshire, 4–20 October www.ilkleyliteraturefestival.org.uk

Manchester Literature Festival 4–20 October www.manchesterliteraturefestival. co.uk

Guildford Book Festival Surrey, 6–13 October www.guildfordbookfestival.co.uk

Beverley Literature Festival Yorkshire, 10–13 October www.beverley-literature-festival.org

To advertise, contact Vicky Ashby on 0203 859 7094 via email vickyashby@theoldie.co.uk scc rate £45+vat. The copy deadline for our next issue is 15th March 2019

Churches Festivals 2019

Isle of Wight Literary Festival 10–13 October www.isleofwightliteraryfestival.org

Two Moors Festival

Dartmoor, Exmoor, 11–20 October www.twomoorsfestival.co.uk

Festival of the Future Dundee, Scotland, 16–20 October www.literarydundee.co.uk

Purbeck Film Festival

Dorset, 18 October–2 November www.purbeckfilm.com

Wells Festival of Literature Somerset, Dates tbc www.wellsfestivalofliterature.org.uk

Canterbury Festival

Kent, 19 October–2 November www.canterburyfestival.co.uk

Petworth Festival Literary Week West Sussex, 26 Oct–3 November www.petworthfestival.org.uk

November

Richmond Upon Thames Literature Festival

Throughout November www.richmondliterature.com

Bridport Literary Festival Dorset, Dates tbc www.bridlit.com

Ways with Words Southwold Literature Festival Suffolk, 7–11 November www.wayswithwords.co.uk

Dublin Book Festival

Dates tbc www.dublinbookfestival.com/

Gibraltar Literary Festival Gibraltar, 14–17 November www.gibraltarliteraryfestival.com

Saving grace

Harry Mount on how the National Churches Trust is helping

preserve our heritage

There are 42,000 Christian churches, chapels and meeting houses in the United Kingdom. And a lot of them are in a pretty ropy state.

Enter the National Churches Trust, which, since 1818, has been keeping the wolf from the door –and the roof over the nave – at thousands of churches. Since 1953, it has given out 12,000 grants and loans, totalling £40 million, to religious buildings.

The NCT has helped lots of churches in or near the places in this supplement. It’s given £20,000 to St Philip and St Jacob Church, Bristol – like so many British churches, a sandwich of styles, from its 13th-century chancel, to its 15th-century tower, to the wooden bosses in the nave ceiling made from oak given by Richard II. The NCT gave it £20,000 to repair the roof which – again like so many British churches – had been attacked by evil lead thieves.

Also in Bristol, the NCT contributed £30,000 to the repair of elegant, neo-Gothic All Hallows, built in 1900 by Sir George Oately, responsible for that other great Gothic Bristol landmark, Bristol University’s Great Tower.

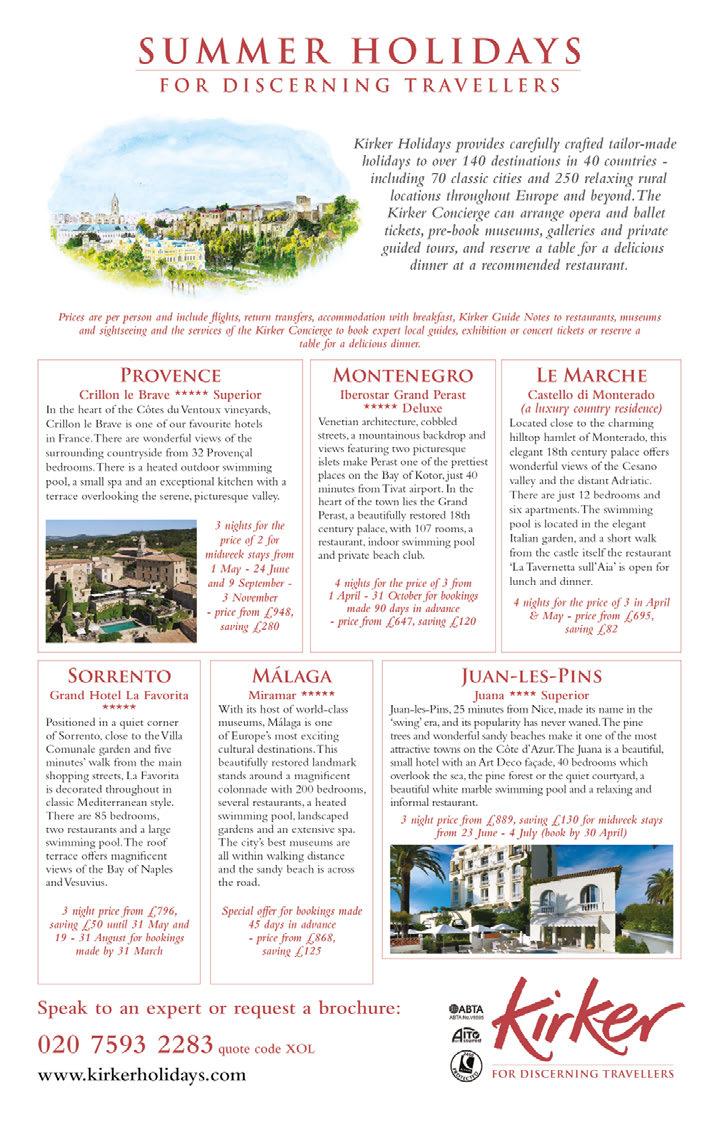

On Colonsay, the parish church

is an enchanting, white-harled kirk, built in 1802 by Michael Carmichael. Among its delights is a birdcage belfry over a pediment punctured with a blind oculus.

That charming belfry was in a terrible state – and, if it hadn’t been repaired, the parish church, a vital building on an island with a population of only 124, would have had to close. The NCT contributed £3,000 to the £60,000 cost of repairs, completed in 2016.

The list of churches saved goes on and on, with each grant an aesthetic and religious buttress against local decline: £60,000 to All Saints, Selsley, in Gloucestershire; £7,000 to All Saints, Ingleby Arncliffe, in North Yorkshire; £10,000 to Holy Cross, Goodnestone, in Kent.

Yes, church congregations have been in freefall for a century. And, yes, atheism is a growing force in the land. But still, again and again, the church is the biggest, most beautiful and often the only religious building in villages, towns and cities. The survival of churches is crucial to our emotional and spiritual health, whatever God you do or don’t worship.

www.nationalchurchestrust.org

Enchanting, white-harled kirk: Colonsay parish church