The Yellow Paper

Journal for Art Writing Edition 6 Summer 2025

The Yellow Paper is published online and in print by Art Writing at The Glasgow School of Art theyellowpaper.org.uk

© Art Writing GSofA, the authors and artists, 2025

ISBN: 978-1-9162092-8-2

Expect them to err: an editorial

Laura Haynes 11

From Five Days of Demons

A Mermaid Walks Over Vito Acconci’s Seedbed

Madeleine Kaye 23

Embracing Paris Maman

Aglaé D. Mouriaux

27 The postroom 2022/2025

Catherine Grant

32 a spat-out silver coin and a perfectly rounded stone

Margaret Sheehan-Gray

37 George Square

Maria Howard

42

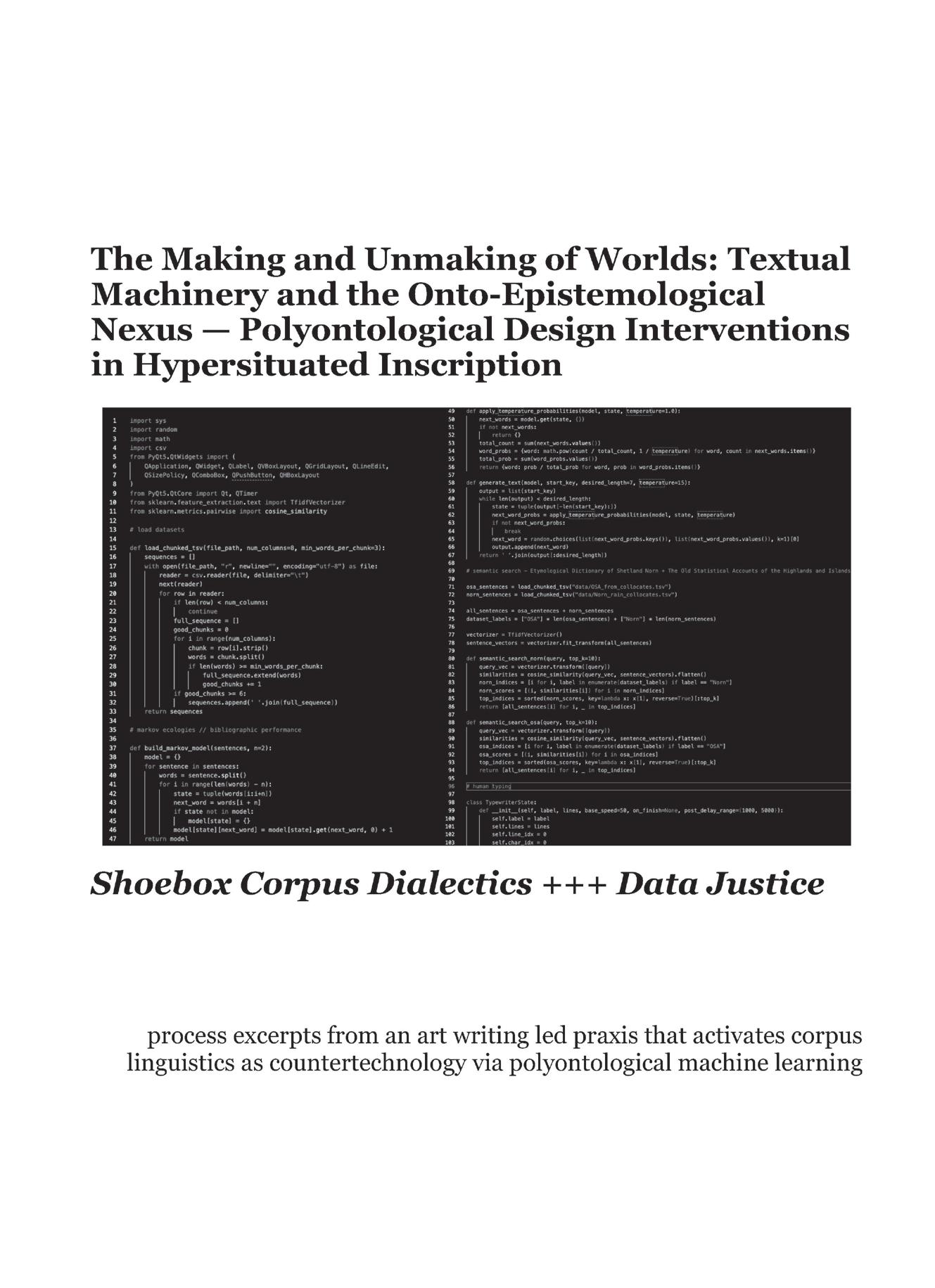

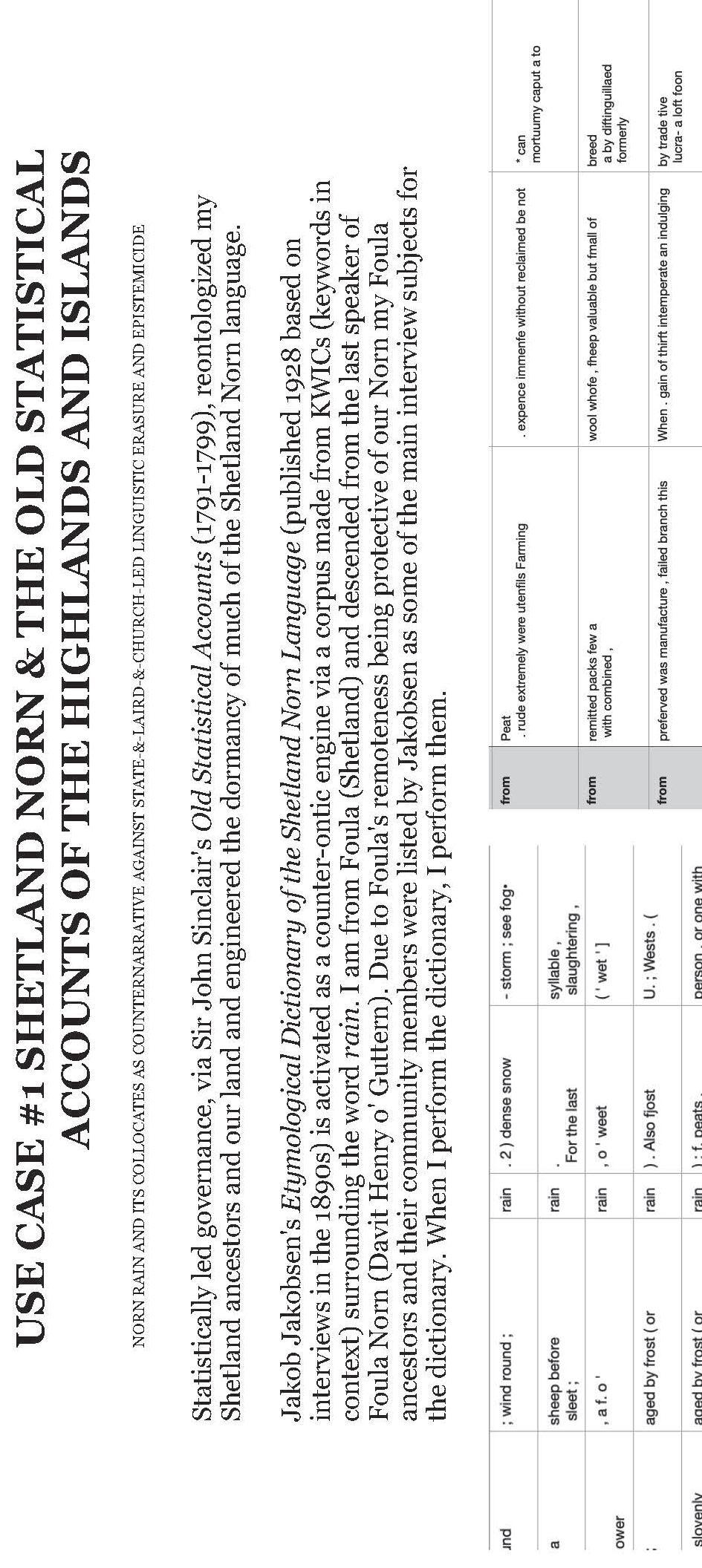

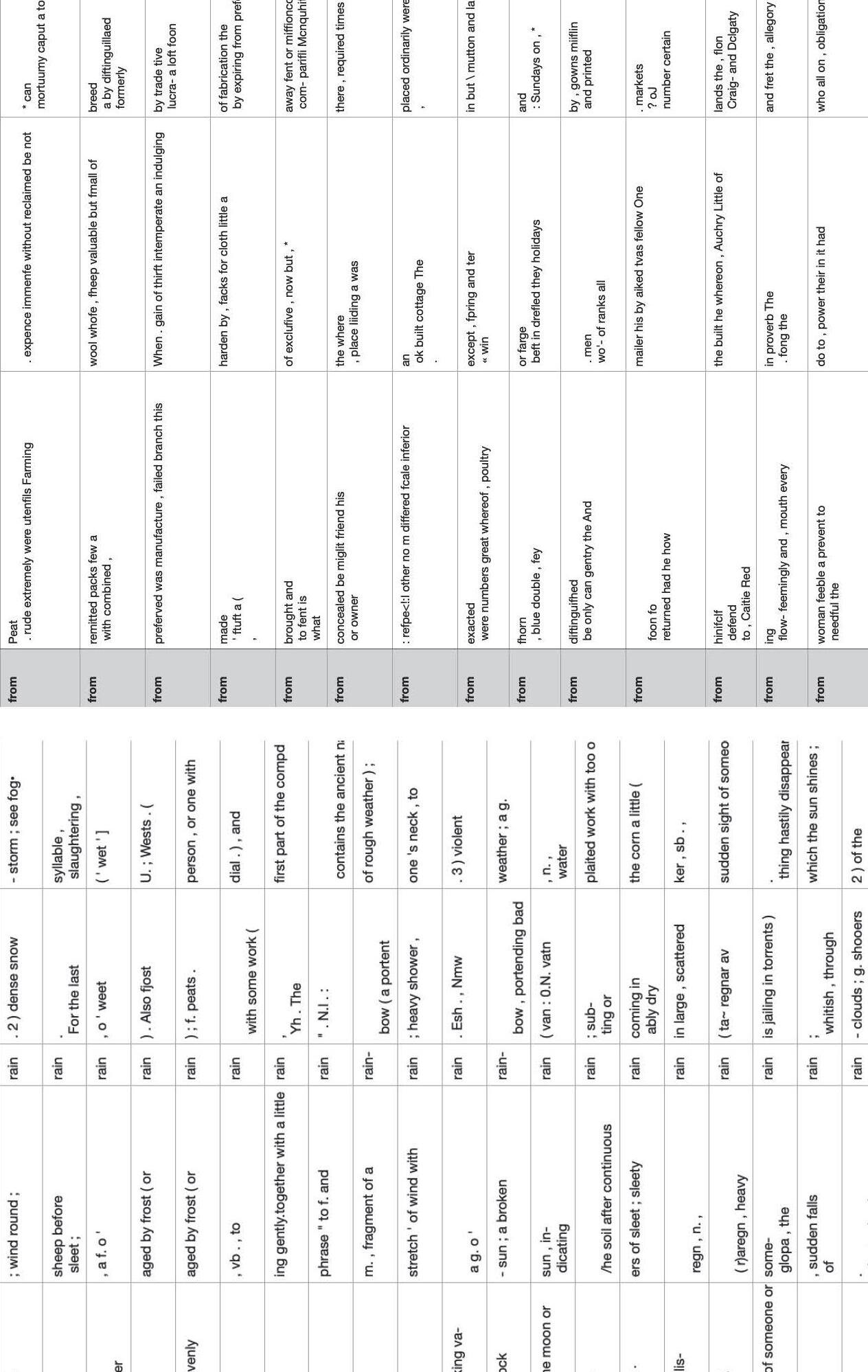

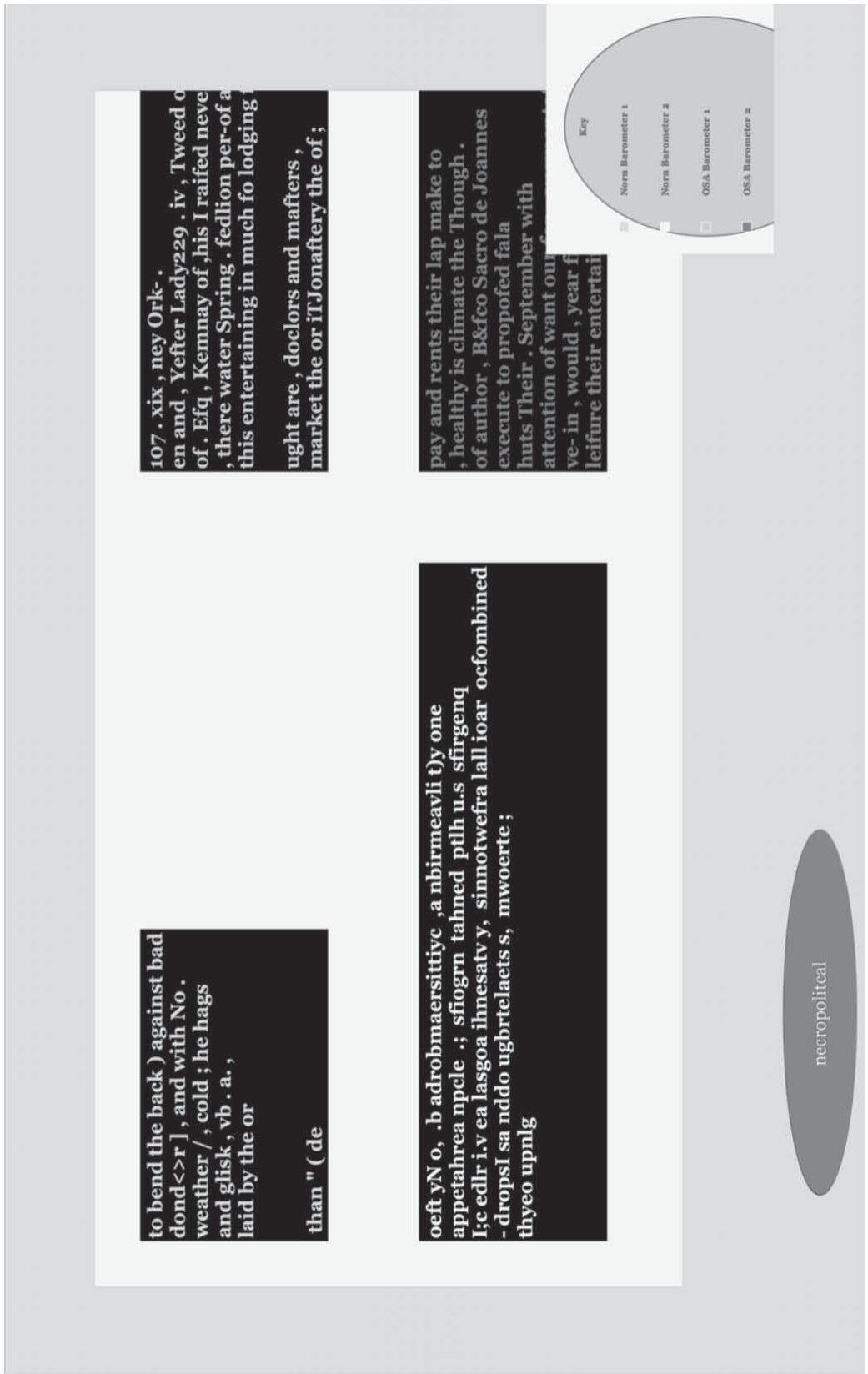

The Making and Unmaking of Worlds: Textual Machinery and the Onto-Epistemological Nexus - Polyontological Design Interventions in Hypersituated Inscription a.w. Cutler-Gear 51

All we did was say hello Kate Briggs

Moss Body // Pink Moon // 06/25

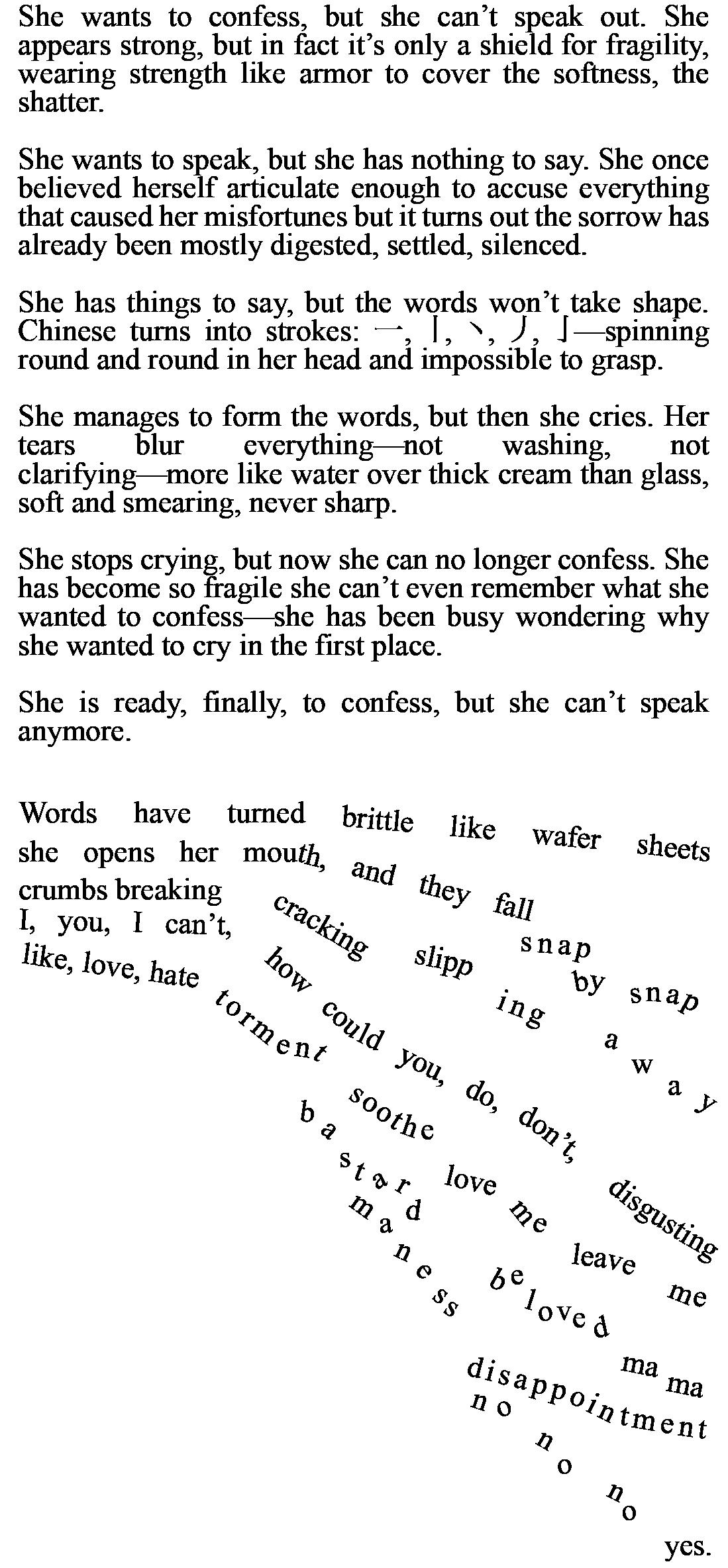

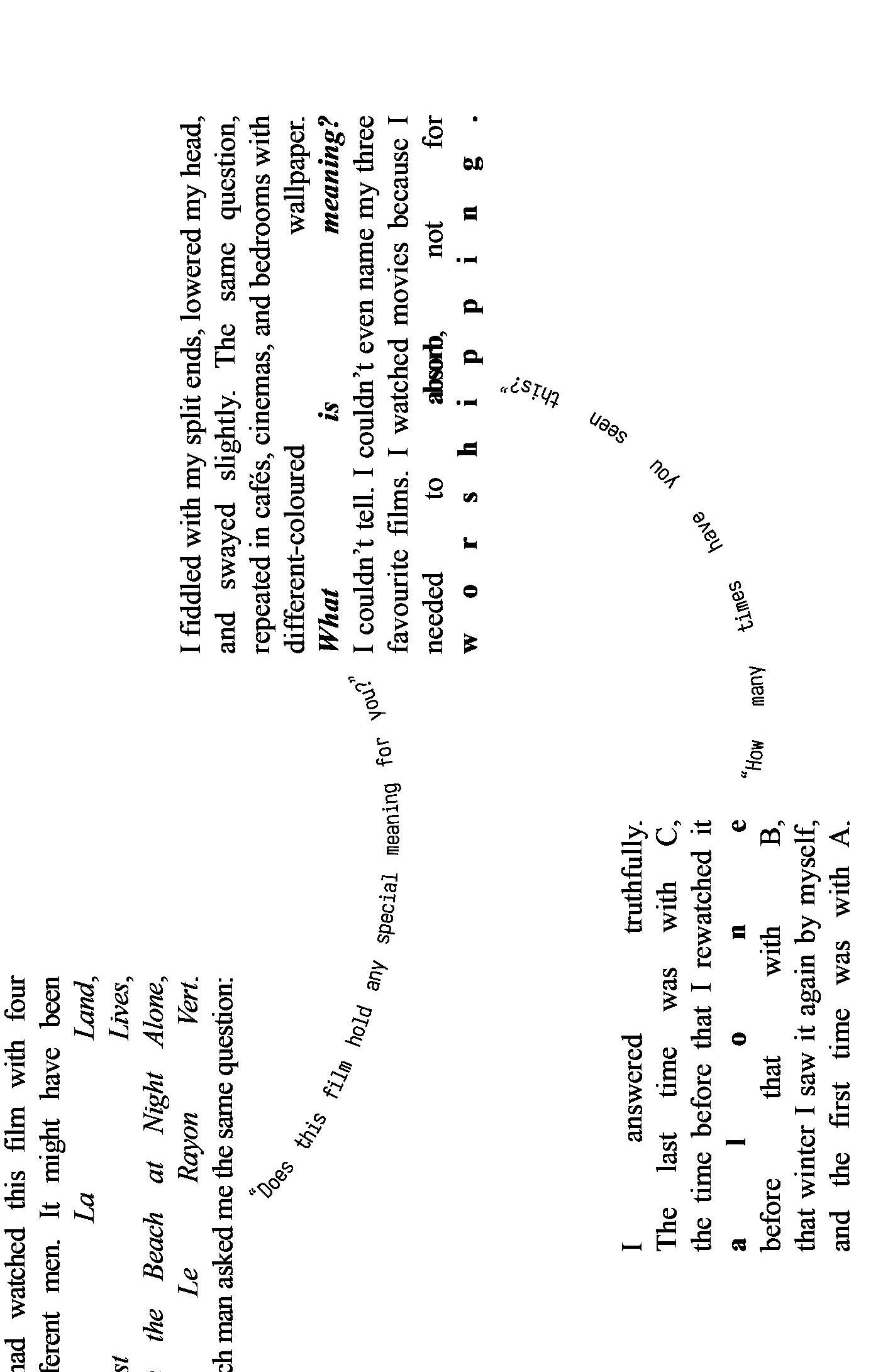

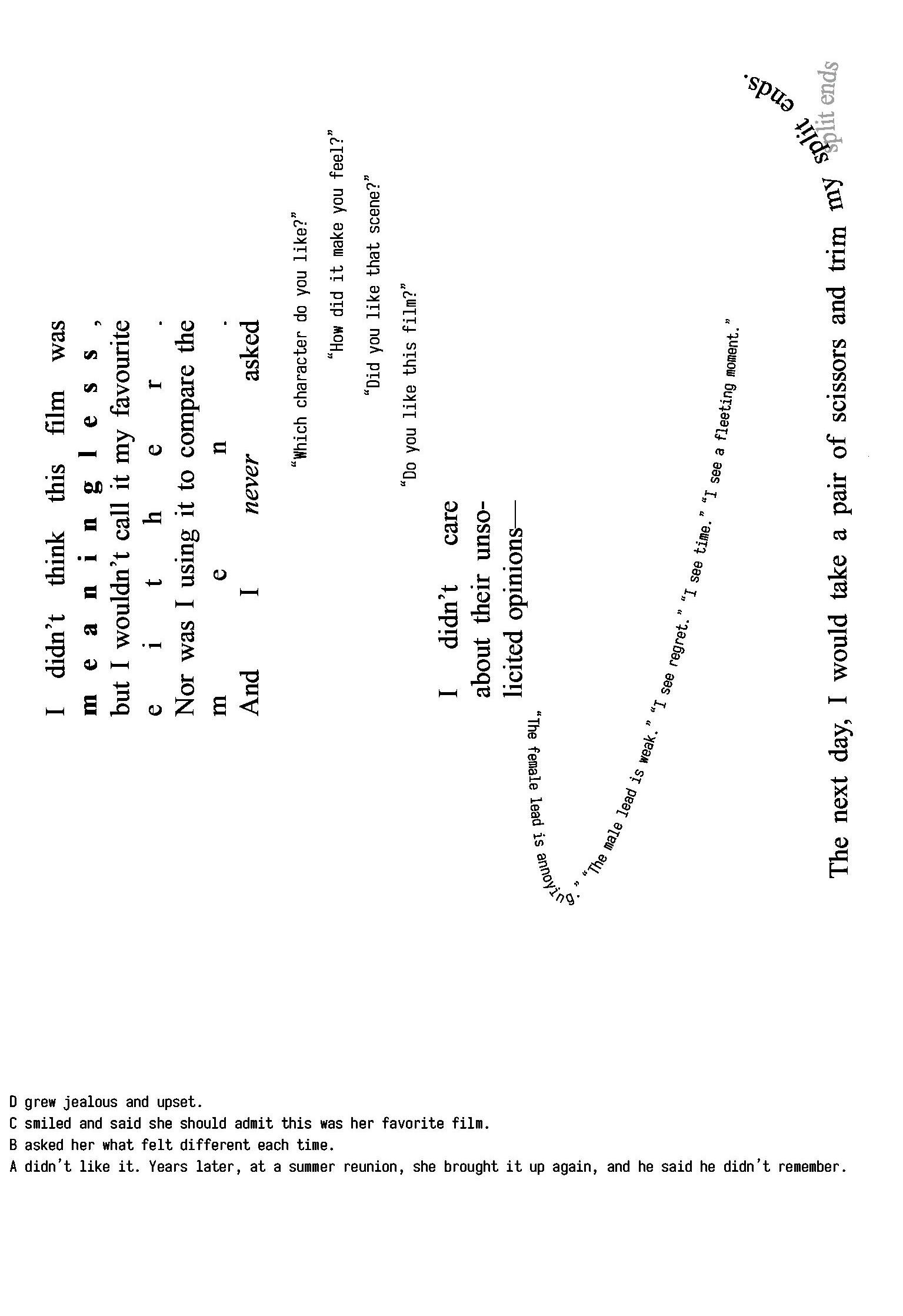

This is not a confession Split Ends

Pinzi Lu 63 The ruckus

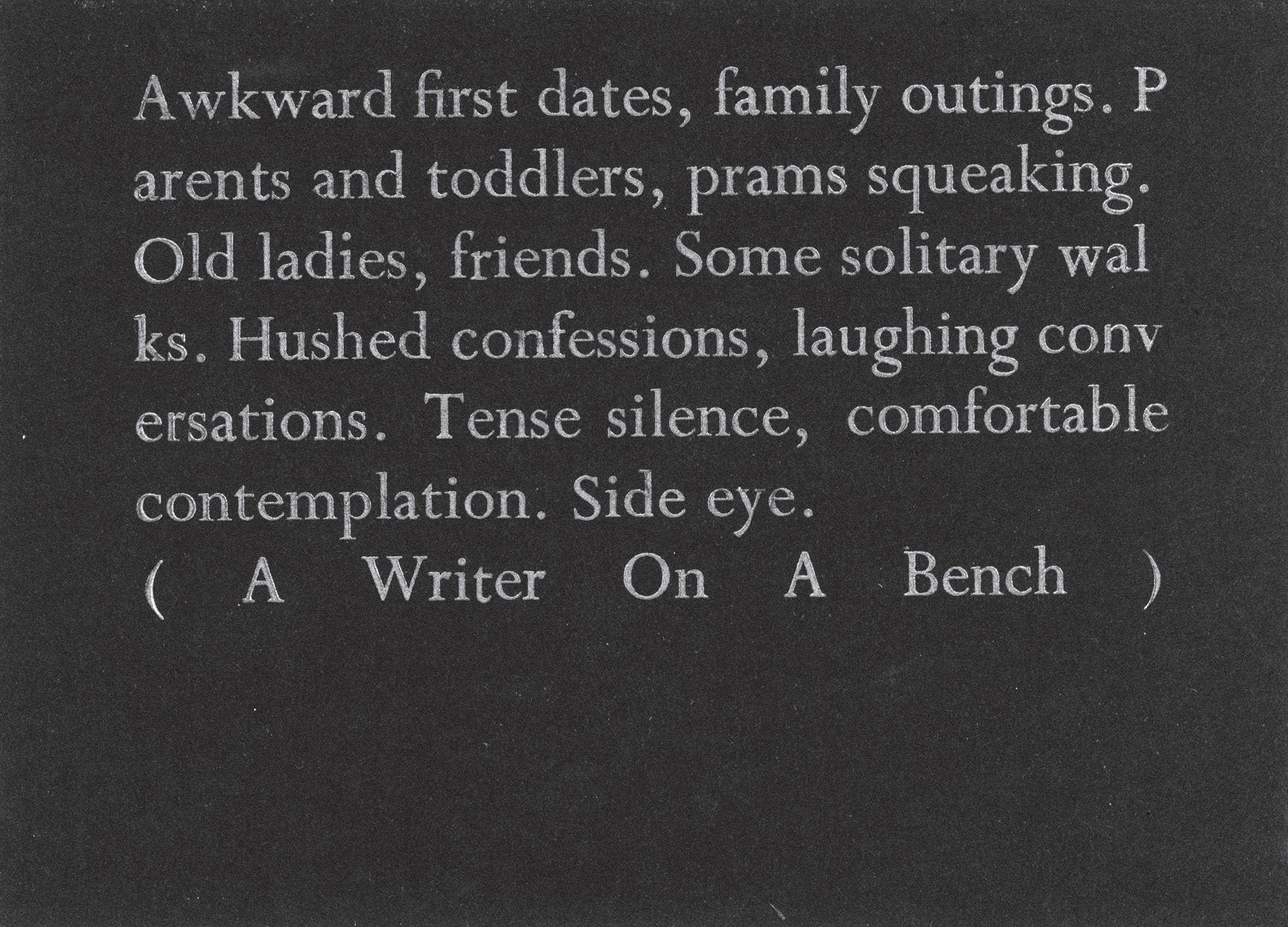

Rebecca Meanley 69 Postcards

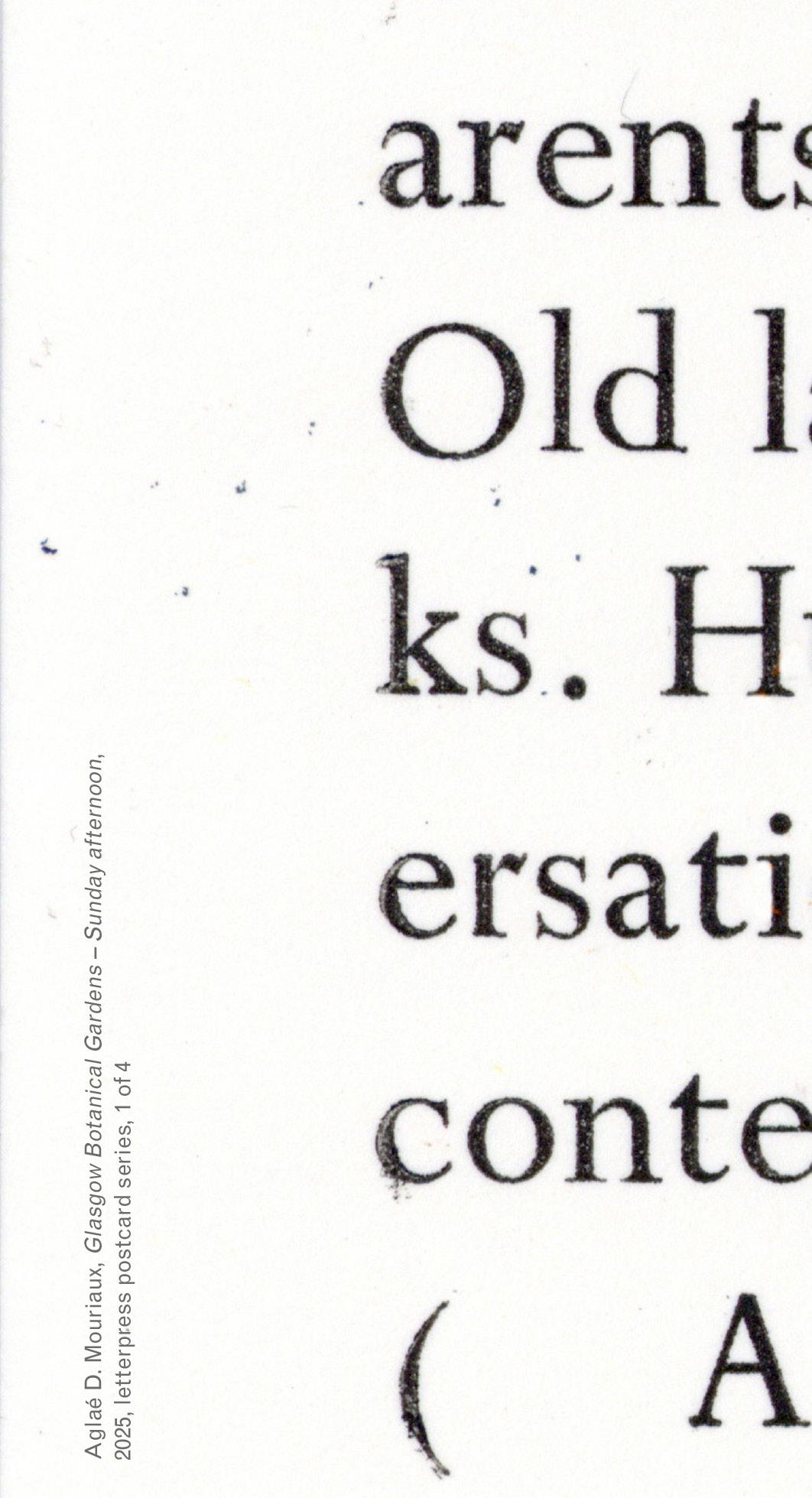

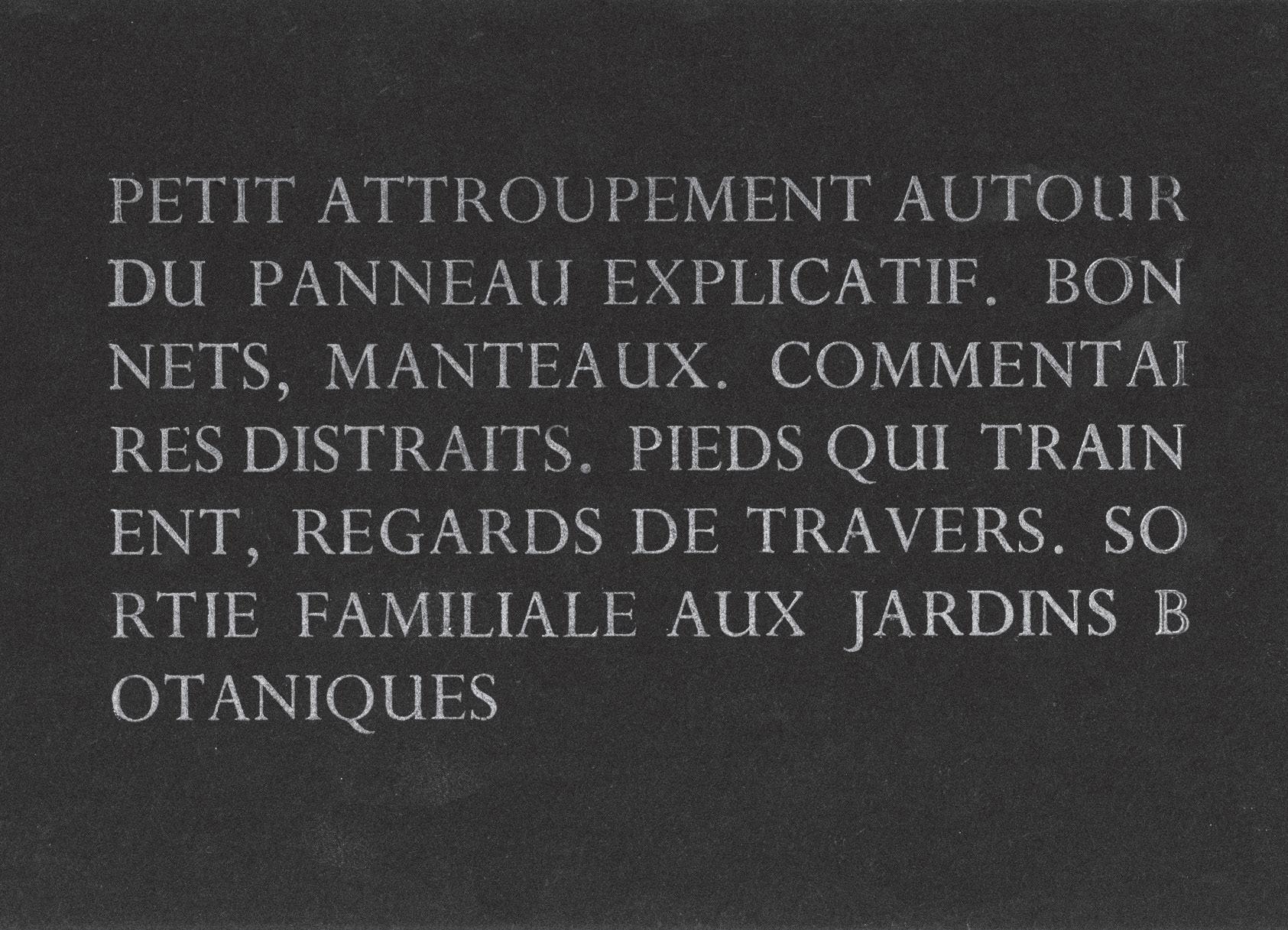

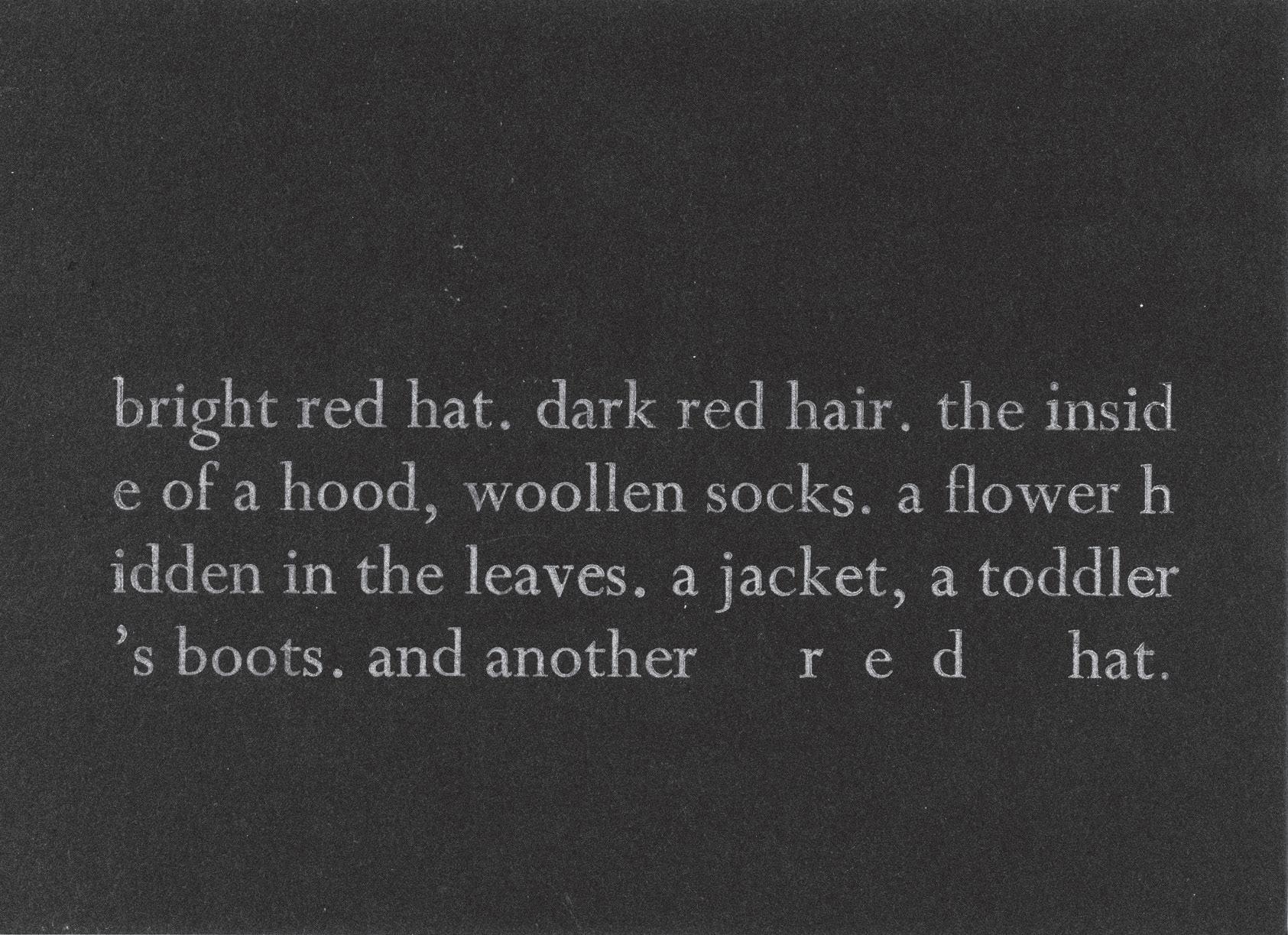

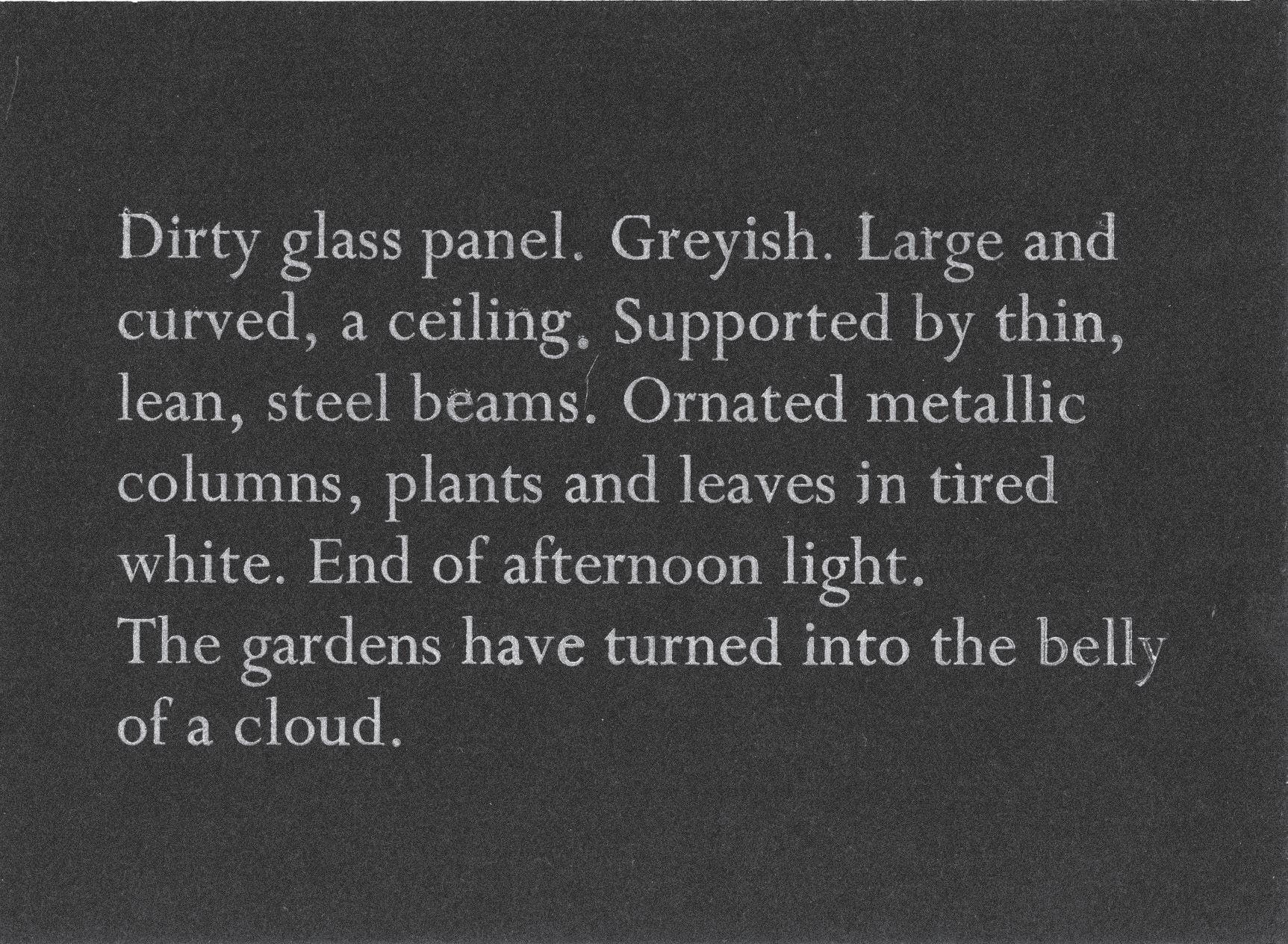

Glasgow Botanical Gardens - Sunday afternoon - 1 to 4

Agl aé D. Mouriaux 73 No One’s Home

Eilidh McDade

77 (shell to ear)

Maeve Dolan 81

Excerpts from a hybrid-fiction

Eilidh Akilade 85 Knock, knock Rosie O’Grady

Expect them to err an editorial

Laura Haynes

This is a story of digression. An excursion in loosening method.

In January I stood with one of this year’s Art Writing graduates and faced multiplied pangrams rendered in cyan, yellow and magenta across multiple media. This work was part of an ongoing exercise in improvisation and restraint, in the approximate senseless, and in discoveries of the associative profound. It is part of Aglaé D. Mouriaux’s graduate project and I turn to it here to demonstrate and reflect on the manner of Art Writing, the programme, its participants and of the genre or discipline. ‘Expect them to vowel,’ reads the third pangram. ‘To ryegrass, to bird funk, to jazz quartz.’1

Expect them to vowel.

I digress.

Expect them to verb. Let this be an excursion. Let the teller disappear into the act of telling. Expect them to err, to errancy, to assemble a programme of negations and reinventions. Expect them to imagine a genre of the yet to be.2

This is a story of digression. Where do we begin?

1 Aglaé D. Mouriaux, Writing Practice I, Art Writing, The Glasgow School of Art

2 Mary Cappello, ‘Timeless Dwelling: Imagining a Genre of a Yet to Be’, creative|critical, https://creativecritical.net/vanishing-acts-the-embodied-marycappello/

In September 2018 the postgraduate programme in Art Writing at The Glasgow School of Art was launched. This enterprise was part of a broader project to foster Art Writing as a specialism, as a discipline?, a paradiscipline?, a critical theory, as an attuned and philosophical practice in the School of Fine Art. What I have learned since then has concerned a vital practice of deviation and I know myself to be fortunate to have formed, shared and trodden—heavy and light-footed—with trusting, testing and gallant tellers of a moment. Since 2018 I have spent my time with co-conspirators who have been equally invested in knowing what material, critical, experimental, conversational, fictional and nonfictional, performative, aesthetic, instructional, propositional writing can do, what it offers us in a fractured and terrifyingly fracturing world. In edition 1 of The Yellow Paper: Journal for Art Writing, published during the commencing year of Art Writing, I named this a ‘kind of remedial romance’, a form of ‘compassionate theory’—of ‘affection, gratitude, solidarity […] a form of care as a form of practice which situates itself the/a present’.3 This call for reparative practice(s), I noted, is in a spirit of resistance and a necessary form of renarrativising. I would argue that as a collective of people, as a shared inhabitancy of time, the Art Writing programme at The Glasgow School of Art has offered just this: renarrativisation in a spirit of resistance. As a verb Art Writing is far from redundant. Just as a life can bear, it is a form that can accommodate and occupy: as a language-based practice it is material, interdisciplinary, academic, critical, political, gestalt in its objects, visible and invisible. ‘What is to be written of art that evaporates?’ asks Madeleine Kaye, and continues:

We present this piece in the gallery, cork it open and spray all the bare necks of the unsuspecting visitors in their fur coats, and as the perfume lands on their skin, its existence changes, defying a universal description. The absence of this universal description, the unavoidable failures of any attempts at this non-existent text, is the space where I write.4

3 Laura Edbrook (Haynes), ‘As if*: an editorial’, The Yellow Paper: Journal for Art Writing, 1, p 5

4 Madeleine Kaye, ‘Writing Sculptures and Exploding Galleries’, Art Writing, The Glasgow School of Art

Art Writing is ‘heard as tone, not carved as stone,’ as with the chimeric patterning described by Daniela Cascella in edition 2 of The Yellow Paper. It is equally ‘impossible in theory but real in the imagination’. Cascella wrote:

Here is a form of writing that is chimera, composite of parts written in different styles, some of which may seem impossible, monstrous, disturbing. Here is chimeric writing and it demands neologisms, a new vocabulary, wildly imaginative approaches to reading, hear Chimera.5

This deviating practice is chimeric and its changing existence is perennial. This year concludes the seventh year of the Art Writing programme and 2026 will conclude Art Writing as a master’s programme in the School of Fine Art. This news is experienced as loss by inhabitants, but I trust it to not be a marker of redundancy or failed resistance but, let’s hope, a perennial rearrangement where Art Writing as a project continues in the School with new and broader coalition and chimeric initiatives. The last seven years have sparked new forms of colloquy, new partnerships and methodological clusterings in Glasgow and beyond and this constituency of people and places, this atmosphere for dialogue, will continue to thrive, will continue to move with and across affiliations. ‘Each type of punctuation has its own rules and related movements, but against all of that it can be a blank. A moment to reorganise,’6 writes Art Writing student Emma Mortimer.

This last year we have been grateful to work with Olivia Douglass, Catherine Grant and Laura Guy as part of our Form & Field study intensive. Lisette May Monroe returned in the second semester for Publishing & Publics, along with Art Writing graduate Alison Scott and Ailsa Lochhead of Move To Feel. The contributions of Kiah Endelman Music, Maria Howard and Rebecca Meanley as Graduate Teaching Assistants have been invaluable and on behalf of the programme and the students I thank each of them for their

5 Daniela Cascella, ‘My Chimera’, The Yellow Paper: Journal for Art Writing, 2, p 15

6 Emma Mortimer, ‘And/Or’, Art Writing, The Glasgow School of Art

enthusiasm and commitment. Further gratitude is expressed for the distinctive guardianship of Francis McKee in the second semester of this year which allowed for a sabbatical and some writing time. In an extract from Five Days of Demons, Francis writes of Sean Bonney’s call for the incendiary torch during fall, failure or dismantlement. ‘Set against a backdrop of an increasingly volatile and hostile world, these calamities are small but are instructive,’ (p 30) writes Catherine Grant. If you’re alive to it this disconnect is daily and insistent.

In October we contributed to the Cooper Gallery’s Sit-In Curriculum’s fourth chapter of The Ignorant Art School; we invited Esther Kinsky to GSA to be in conversation with Anne-Marie Copestake; worked with Jude Williams towards live readings at Soft Shell: Through the Cracks presented at the Poetry Club, Glasgow. We were delighted that Jude also performed as part of this event. In May we held the group exhibition Floor Boards and published the first part of ‘With Palestine’ as a special dossier of The Yellow Paper online.

In this edition, Rosie O’Grady contributes ‘Knock, knock’ following the award of The Yellow Paper Prize for New Writing for her memoir in three parts, Naming the dog. This work was later awarded The Emerging Art Foundation Art Writing Prize 2024.

Also included is ‘All we did was say hello’ by Kate Briggs, an extract from ‘A Social Process of Unknowing Yourself in Real Time’: Work on Conversation, published by The Yellow Paper Press and to be launched later this year. This book conversationally gathers the activity around Kate’s residency in the School of Fine Art between 2022 and 2023. It is a book of collective thinking, workshop materials, exchanges, pedagogical rituals and new writing.

It has been a full and vibrant year. It has been a full and vibrant year across the realms of different discourses and interdisciplines. In gasps and gaps, its verbing is resonant and reverberant.

For what can be oppressive in our teaching is not, finally, the knowledge or the culture it conveys, but the discursive forms through which we propose them. Since, as I have tried to suggest, this teaching has as its objective discourse taken in the inevitability of power, method can really bear only on the means of loosening, baffling, or at the very least, of lightening this power. And I am increasingly convinced, both in writing and in teaching, that the fundamental operation of this loosening method is, if one writes, fragmentation, and if one teaches, digression, or, to put it in a preciously ambiguous word, excursion.

Roland Barthes, ‘Lecture in Inauguration of the Chair of Literary Semiology’, College of France, 7 January 1977, October, 8, 1979, p 15

From

Five Days of Demons

Francis McKee

The reality is that some of the greatest contemporary poets are published in obscure limited editions that attain little visibility in mainstream culture. Perhaps this was always the way but it feels more jarring now when the makings of our already flawed worlds are being dismantled ruthlessly around us.

In his final book, Our Death (2019), the English poet Sean Bonney wrote about this process with an almost prescient sense of his own death which came just a few months after publication. The book, though, is not entirely doom laden or defeatist. He writes, for instance:

You are not absolutely defenceless. For the torch of the incendiary, which has been known to show murderers and tyrants the danger line, beyond which they may not venture with impunity, cannot be wrested from you.1

Still, in the final lines of a section entitled ‘From Deep Darkness’ he does compose a form of last will and testament:

My five senses I leave to the invisible moons of Pluto, like a cluster of burst and eclipsed stars, like the city’s swifts, flickering in and out of calendrical time, where coffee cups and typewriters and habits and all the rest become a violent disk of knots and tumors trapped

1 Sean Bonney, Our Death, (Commune Editions, 2019), pp 67-68

somewhere far outside of the known world, because obviously after five days without sleep your heart gets into some fairly interesting unknowable rhythms and your connections with the earth and its five senses become increasingly tenuous and I think at this point of Will Alexander’s essay ‘A Note on the Ghost Dimension’, I don’t know if you’ve read it, he writes in it somewhere about the missing five days of the Mayan calendar, which apparently is a time when monsters and poisons will appear, and I don’t know much about the Mayan calendar, but after five days without sleep I know a lot about ghosts and monsters and poisons, and a lot about how the missing five days could be taken to mean the fate of the five senses themselves, and how those missing five senses have been kidnapped and held for no ransom on some irrelevant island deep within the center of some capitalist astrological system. My tiny racist island I leave to the monsters and poisons.2

And Our Death remains a tough book to track down. Just as the essay he mentions above by the poet Will Alexander—‘A Note on the Ghost Dimension’—can be found, with some difficulty, in a 2012 collection of his essays and prose, Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat. The ‘Note’ is couched within a futuristic vision falling in the long wake of September 11, 2001:

The void exists in the illusive dunes of Afghanistan. These upper relics of ghosts charged with the most ferocious diplopia. The mind of the American soldier as if eight months out on Mars, void of provincial guidance, his god refusing to appear, each day and night a poisonous cinnabar smoke. Waking and sleeping amidst the language of the asteroids.3

Alexander imagines the ever-recurring fall of an empire in which escape only resides in breaking the cycle of self-immolation:

2 Bonney, ibid.

3 Will Alexander, Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat: Essays, Prose Texts, Interviews and a Lecture 1991-2007, (Essay Press 2012), pp 22-23

Now, the twin towers and their ongoing aftermath, with the burning glass, and bodies falling through the air to secular burial grounds of dread. But by adherence to unilateral attack America opens itself up to the powers of the fumes of retaliatory ghosts. If all the orchards go astray and burn what will rescue us from Andromeda? If the oceans turn a green Venusian liquid what will survive? Statistics no longer thrive. Popular astrology is misleading. Yet the five empty days on the calendar of the Maya persist in my vision. Days when monsters appeared, when nights reversed and people hovered in a poisonous neutrality. Let’s say it like this. Our bodies are invisible documents because our language continues tracing those other stellar locales where we invisibly glide to other galactic possibilities far beyond the suicidal repartee which the American tenor so fitfully engages. In twenty billion years a new sun will be forming, with green light burning beyond human debate. Only a vatic recitation can overcome rehearsals for destruction.4

4 Alexander, ibid.

A Mermaid Walks Over Vito Acconci’s Seedbed Madeleine Kaye

Afraid of being unfashionable, as always, I ask the mermaid if I may use sweetness to disguise the poem found between her legs. It’s sad that she must realise this is an attempt at delaying the inevitable arrival of a crude joke about seam ripping.

Because it’s still there, below, a hooded eye looking up between the slats. It’s Vito enjoying himself a moist broadcast.

She announces her arrival to his gallery with a dollop of her tail, followed by the scratch of petrol rainbow over a heart. Not the beating heart, it’s not the old man’s foretelling. Just the groove she feels like her own scales, like the glitter she counts where others would weigh themselves, because it is only ever on wood and above water that she faces accusations of weight.

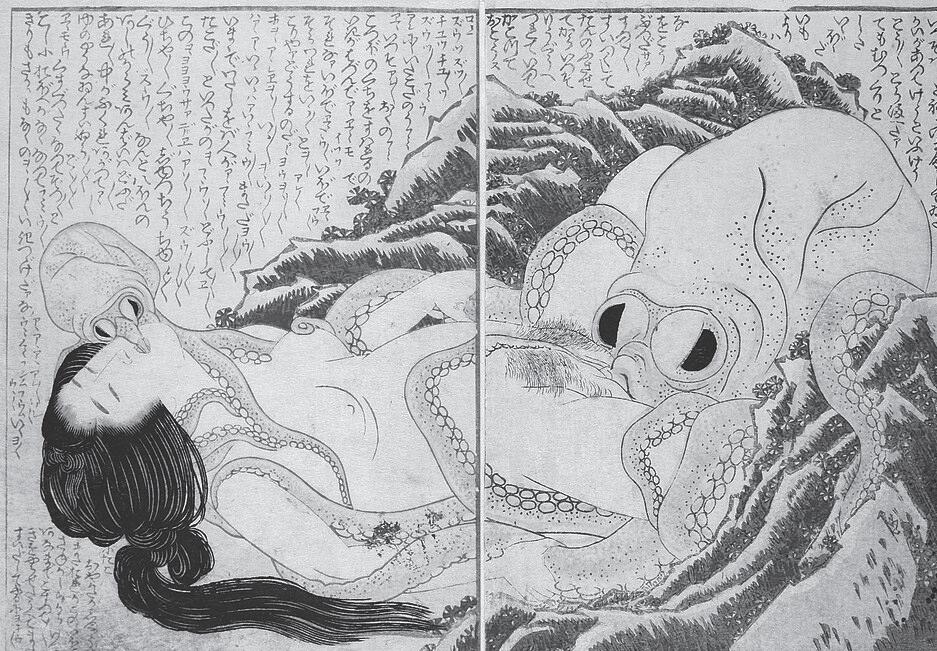

She does not know yet of a once-plump Peggy; a two-legged copywriter with a cigarette dangling from her mouth and an octopus pleasuring a woman tucked under her arm. Somewhere in there is a ship of Theseus story troubled by a wooden mermaid long used to decorate our hulls. She’s removed from the ship and stored in archive dust, and there she tells her son, the salty sconce, in her own wooden way, tales of his father, of his beautiful orange tentacles.

There is a statue also, made boring by birth of bronze and its innate resistance to wet-rot. A statue above the waves is always

unsettling; to be placed before the world was flooded. To shout your defiance, but only ever like a small Danish girl, demurely sitting on the harbour rocks. Secured in place, she is unable to slip into the twenty-four-hour diner where the servers never complain about saltwater on the vinyl seats. It is there that Peggy orchestrates a mermaid meet.

The mermaid never suffers hiccups, lips cleverly gup-gupping to drink from the other side of the cup. At spilt coffee, she dreams of a namesake in original and complete glory; Seattle signage with split tail outstretched, tips held in crooks, bare chest obscured by tendril locks.

A mermaid knows two stories. She cannot tell either to Peggy, who is busy ashing her cigarette into an empty shrimp cocktail glass, because the mermaid sold her voice for a seam ripper. She wanted a silver to hook between the silt.

One: the white clouds of seafoam are the result of a cousin crying at a lost human love.

Two: the white clouds of seafoam are the spend of Poseidon’s seed.

Either way, a mermaid’s purse quivers in anticipation and delight.

To find land, she slid between fishnet tights. She let her Vaseline body be hoisted into the sky, closed lips when sailors sighed at the oil slick crease of her thigh. This is how she found the gallery where Vito hides under ramp, touching himself to thoughts of visitors, and blades and tongue meat, and meat of tongue, and other stolen puns, because the mermaid does not know, for Vito to be happy, she cannot know.

The joke is lost and found in stitched legs. She is as light as the house her ship built. She is where Jack lost his axe. She’s a wet fish-siren, an open-mouth-door-mouse, a musical robot found slapping on the wall of a board and batten tavern.

It’s a lisping wave crash mechanic; the allure of absent gargled sound; a mermaid tail dripping on the fantasies of an artist unfound. Under disguise, like sugar to salt to sand; she is breathing. She is un-drowned.

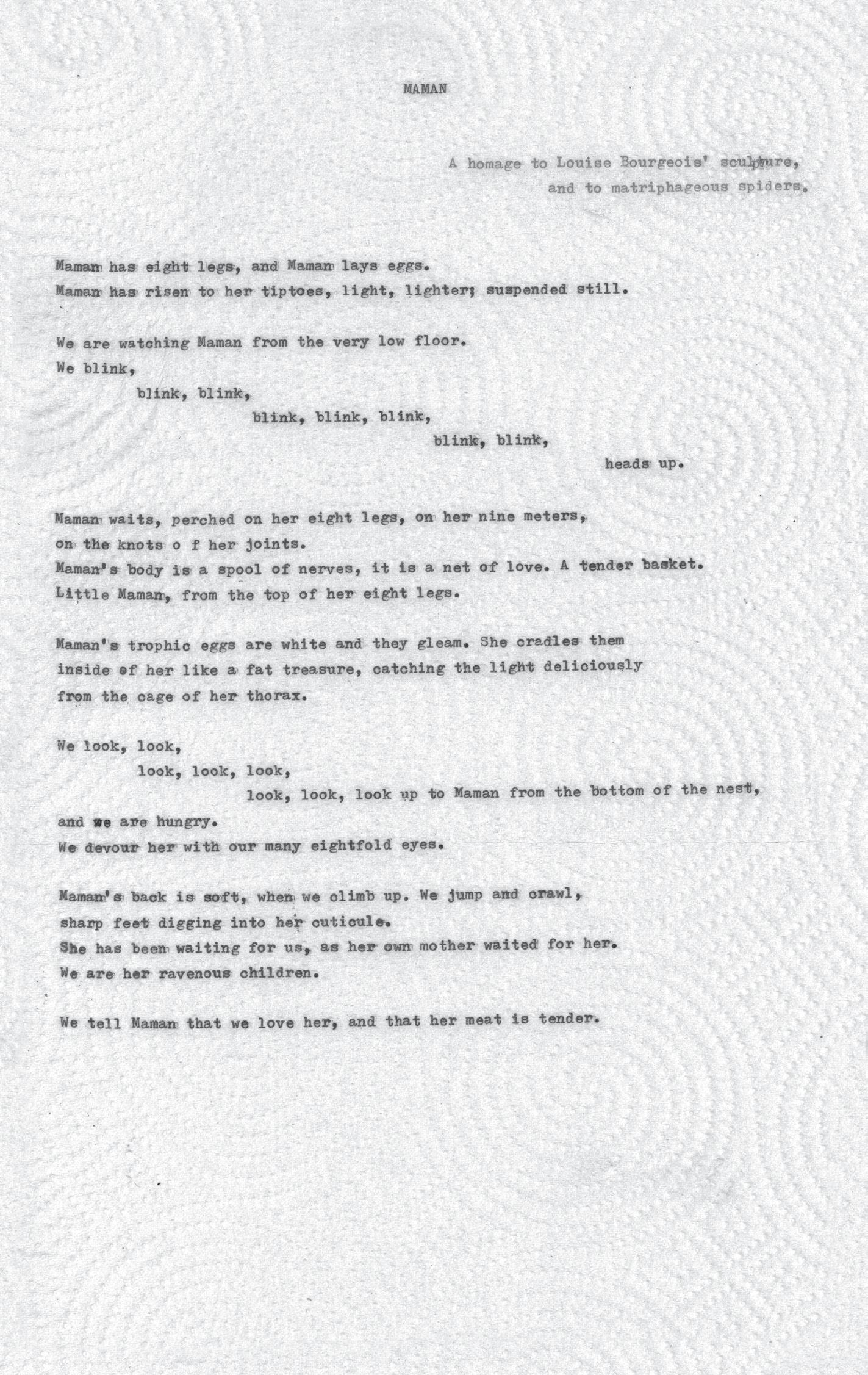

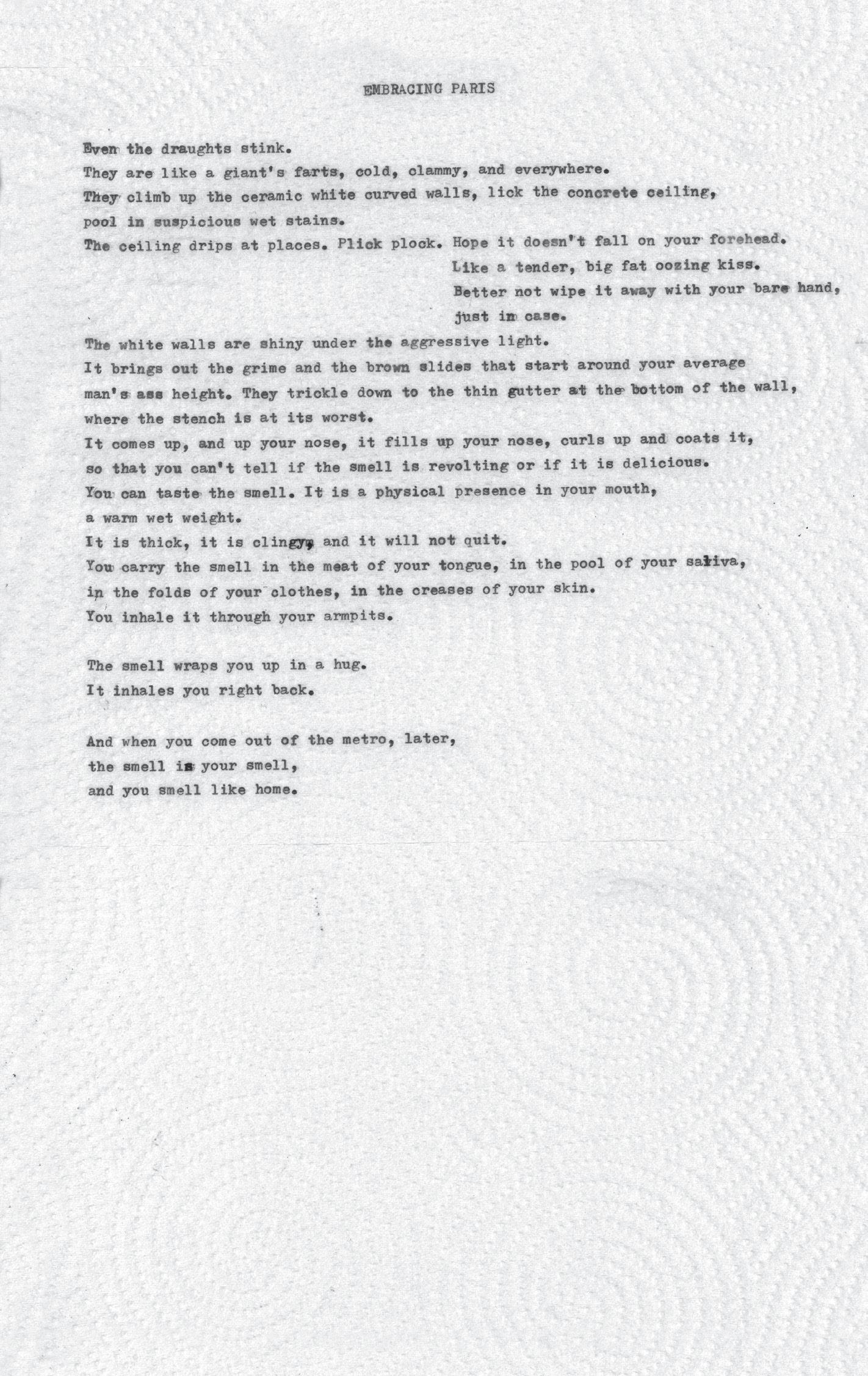

Maman & Embracing Paris

Algaé D. Mouriaux

The

postroom 2022/2025

Catherine Grant

The post isn’t delivered anymore. In this university, like many others, the post used to come to a central room, the postroom, where it would be organised and delivered to each department. Then someone, normally an administrator, would go through the pile, posting parcels and letters into individuals’ pigeonholes. A simple system that occurred without notice, becoming less and less urgent as emails and digital transfer reduced the amount of physical items. Visiting the postroom now is to observe a system halted, disrupted, but not completely dismantled. Piles of letters, circulars and parcels gather in departmental pigeonholes, left for months without anyone seeming to know that they need to be sent out anywhere beyond this room.

It is the end of the academic year, following months of tense industrial action. I think about the post, and how it used to travel around the buildings. This is one tiny element in a new wave of reform, framed as efficiency but experienced as chaos and loss, distilled in the experience of visiting the postroom. I had been going in, on occasion, in my last few months of work, checking on what might have arrived. The replacement for the quiet movement of letters and parcels has been nothing. A drift of not caring, a pile of pretend innovation which is in fact an exodus of people, roles, structures, empathy. I thought that something would be put in the place of the previous system, but over the summer I can see that nothing has been, and probably for most people, this is the smallest problem in a huge pile of completely foreseeable consequences to redundancies and restructures.

To retrieve post, I have figured out that it is best to visit the postroom and request a department’s pile to leaf through. No one has made this clear, so only the curious or those still reliant on pre-digital communication would bother to sift through. Many staff who joined during covid probably have no idea where the postroom is, or that it exists. I go down on occasion and have a chat with the staff working there, speaking about colleagues who have left, taken early retirement, taken redundancy. We exist in a post-reform limbo: the new structures are only sketched out, and departments are working with fewer and fewer people.

It is eerie witnessing a system so easily halted: the departments still exist, the post still arrives, but the connections between the two have been cut, with no fanfare, no Plan B. It has been a number of years since there were porters tasked with internal mail delivery (itself a trace of a pre-digital system, I have faint memories of memos arriving in lined envelopes, multiple addressees crossed out from previous usage). Administrative reform, framed as efficiency, means that there are no longer departmental administrators who had been the ones to take over the task of the porters. These administrators have now gone, or have been centralised, and those who stayed are overwhelmed with monstrous email inboxes, struggling to contain the requests of students from multiple programmes, departments, locations. Department heads and academic staff have got bigger problems than deciding which person will pick up the post.

In the autumn, I have left the university and started a new job. I meet a friend who is still working there. She had been to the postroom more recently than me. She found a parcel labelled with my name and brings it when we meet: acts of kindness and chance now replacing institutional systems. The level of loss and also incomprehension grows like the pile of post. The lack of investment starkly illustrated in the minor details, easier to think about perhaps than those who have ‘chosen’ redundancy, or those whose workload has doubled because they have somehow managed to stay.

A couple of days later I’m sitting on a train, returning home

from my new job. I’ve left the piles of post and am starting to become familiar with a different set of strategies to wrestle the impossible demands on universities teaching the arts and humanities. I think about the external requests to fix education for school children, to ensure graduates get good jobs, to constantly monitor metrics that speak to everything and nothing, and wonder what compromise between fiction and complicity I will need to find. But I’ve got a job in a department with no redundancies on the horizon, and this is a privilege. I try and push the stress and impossibility away, and focus on the luxury of employment.

I’ve been dreaming about babies. In one dream I have a pram, and a baby that I’m looking after for a friend. We are travelling on a bus and somehow I get off without the child. The dream unfolds in nightmarish panic as I try and get on a following bus to catch up with the baby in its pram, alone and possibly now with someone else. I think about how I will tell my friend what I have done. When I wake I think, why didn’t I tell the bus driver? Why didn’t I call the bus company? In the dream there was no one to help, only what I could manage under my own steam, which would never be enough. It’s not a subtle dream, one in which helplessness and care and individual responsibility in the face of institutional indifference stage themselves in my subconscious.

Sitting on the train this dream returns as I see parents with babies struggling on and off at stations. It’s not rush hour, and it’s half term, so families outnumber workers. A small baby starts to cry, and the plaintive sound activates everyone. There is no ease when a baby cries. Its quietly desperate crying outlines unspecified needs that cannot wait for the end of the journey. As I hear it, I am returned to the experience of listening to my own children when they were tiny, remembering my amazement at the righteousness of babies, the exhaustion that would wave over me at the enormity of what it meant to look after them. I realise that those feelings of helplessness in the face of caring for small children connect with my current experiences of universities over these last few years: in the postroom, on the

picket line, in front of piles of demands and competing fictions that move further and further away from what happens in the classroom.

It’s now 2025, three years since I was first visiting the postroom in search of lost post. Writing up these memories I feel faintly embarrassed. However, the post in the postroom still speaks to me. Universities and public bodies continue to cut resources and shred infrastructure in the service of magical thinking, framed as efficiency savings. I’ve lost track of how many friends are on strike, at threat of redundancy, have been off sick due to stress. Set against a backdrop of an increasingly volatile and hostile world, these calamities are small but are instructive. My ear is tuned to the mute sounds of institutional neglect.

a spat-out silver coin and a perfectly round stone

Margaret Sheehan-Gray

Margaret Sheehan-Gray, cardboard, calico, mohair, 2025, 15 x 23 x 7 cms

Between sleeps he is writing letters to each of us and damning the new tendency for his pen to slip through his fingers.

Even my blasted hands have lost their grooves,

and his daughters jump to extract from every corner of the home an array of stones, each pebble turned pumice to give grip back.

Unearthed and hoisted from their tumbled bellies, three Roman tombstones line the back wall of a museum in Portugal. Dragging my eyes across their softened stone, I read the chiselled tear of an inscription that spells the letters STTL, and an information panel fills the blanks: Sit Tibi Terra Levis, or May the Earth be Light to You. Unlike the slumbering proclamation of other ancient epitaphs (Here She Rests, Rest in Peace), May the Earth be Light to You bears the weight of experience. It is corpse-shaking well-wishing, an appeal that breaks death open. Out steps life, resisting chronology, asking, how was it for you?

The line comes from the Athenian tragedy Alkestis, a play by Euripides about the slippery tricks of a king who is afraid of dying. Adorning his doting wife with the burden of sacrifice, King Admetus bargains with the gods, resisting death. My dad resisted death with a stone spinning between his palms, a thick sheet of card pulled across his lap to lean letter writing. A different type of trade, he wished to give what he had lived to someone else, to pass on the lucky excitement that he was dealt. I write of him too, but what I learn, and as did Admetus, is that words are not enough.

Softness, memory, a grip of it.

May the Earth be Light for You.

Later, as the gap between inhale and exhale swells, I wish to strike a bargain and for the coin in your mouth to send spit hurling across the room. For you to sit up, wipe the Vaseline from your nose and laugh at the sponge we are using to paint water onto your lips.

George Square, July 2025, photograph courtesy of Maria Howard

George Square

Maria Howard

It’s the weekend and she joins the fringe of protesters in the triangle of sun inching its way around the mass of the City Chambers. The crowd is disjointed, not yet an ordered murmuration, flags still rolled up. While she waits for a friend she turns to face the square and tries once again to make sense of this space. Tiered like wedding cakes, the buildings that border it demand attention. They require the eyes to turn upwards, provoke a comparison of scale that can only find a citizen wanting.

Her friend arrives and together they find the student bloc. She takes a picture of them holding a placard that reads ‘“Decolonise the curriculum” starts now’. It’s time to march and the crowd comes together, filling the road like water finding a channel. Another friend texts to ask where they are in the procession and she says, ‘We are almost parallel with the Walter Scott monument’.

Its fluted column is like a giant sundial, casting a line to the north. She walks slowly past it, enjoying the opportunity to inscribe it with another meaning, to diminish some of its height and power. She notices how the moss has covered the stone lions whose faces adorn the roundels on the base, how the reach of empire can extend beyond the human.

She remembers the first iteration of this protest, how a group

of teenagers used the lions’ noses as footholds and climbed up onto the base of the column draped in Palestinian flags like brightly coloured plumage as the crowd cheered them on and took photographs. She remembers the film in which the same chants provoke a tear gas attack, in which a man wraps his body around a beloved olive tree and is shot.

She’s not wearing a mask this time, though she probably ought to be. Like the statues of great men on their pedestals, the security cameras look down on the crowd from a height. The bird’s eye view must make more sense than the perspective from the ground. From the sky, the square becomes a great clearing in a stone forest. On the pavement it seems too large, too bare, and too open to be a place to relax in.

The gulls have taken up their position on the historic figures, icing the bronze heads with their white shit, occupying one of the few perches free of spikes. She thinks about how hard it is to spot discernible differences among more-than-human animals of the same species. There might be small differences that are obvious upon close inspection but these pale next to the huge range of combinations possible for a human face.

She walks past a poster for the campaign to remove the military grade CCTV cameras that are capable of recognising emotions as well as facial features. First developed for the purpose of surveilling and extorting Palestinians, they record sexual preferences, infidelities, financial problems or family illnesses—intelligence of dubious worth that is used to turn them into collaborators. She wonders if it’s the same camera as the ones posted on the gates of the arms factory, outside the university, if somewhere an algorithm is connecting the lineaments of her features with all these places she passes through as citizen, student, researcher, protester.

As they leave the pedestrianised area of the square the protestors fill city streets. It feels good to stop traffic, to jam the intersections of the grid system.

She remembers another iteration of this protest. A grey day where the mass of the City Chambers cast no shadow. The woman on stage pronounces it with a hard /z/ and it becomes gazza. She happened to be looking up at the cupolas that crown the corners of the building, and noticed the nets strung up in the arches to keep birds from sheltering in them and she hears it in her other mother tongue, where gazza is magpie.

The protesters’ chants are amplified and echoed by the chiselled cliffs of stone. No Justice, No Peace, in the conditional and the conjunctive. A call and response just like those of the songbirds in the park.

On the Monday after the protest she returns, walking the edges of the square, empty now. She maps time as well as space—the memory held in the stones looking down on the site goes back centuries, millennia, overwhelming the nine years of her own recollections. Still each scale creates an echo, a feedback loop that interrupts the present.

Temporary boards fixed to scaffolding poles describe the square as the city’s living room but the humans rarely outnumber the birds unless there is a protest, a football celebration or a festive market. The only benches, encircling the monument at the centre of the square, are mostly unoccupied.

The new headquarters of the refugee charity occupies the former offices of the Bank of Scotland. A video taken at sunset shows the view from the prayer room, the City Chambers bathed in Western light. Next door is the Merchants House, its domed tower topped with a ship sailing on the surface of a globe, its prow pointing west. The organisation’s crest bears a motto that hints unabashed at the logic of triangular trade, toties redeuntis eodiem, so often returning to the same place.

The buildings flaunt their grandeur and their permanence in the face of those confined to temporary contracts, rent hikes,

and situations that make the danger of leaving outweigh that of staying. They are complicit in an unmarked history.

Months later, she passes on the bus. The square is enclosed by hoarding, the promised redevelopment is underway, the plinths temporarily shorn of their statues.

a.w. Cutler-Gear

All we did was say hello Kate Briggs

An extract from ‘A Social Process of UnknowingYourself in RealTime’:Work on Conversation, edited by Kate Briggs and Laura Haynes (The Yellow Paper Press, 2024)

The first workshop was intended as a writing workshop. We were going to share our thoughts and questions and experiences of conversation and then do some writing. An invitation was sent out to the School of Fine Art community inviting anyone with an interest (or a potential interest) in the thematic to join. Conversation—described by the invitation—as, among other things, a form of social involvement. Possibly as Henry Fielding describes it in his ‘Essay on Conversation’ (1741): the ‘grand business of our lives, the foundation of everything either useful or pleasant…’. As something that happens around or happens to or essentially supports a practice. As a modality of teaching and learning. As a material, potentially, in and of itself. (What if a conversation is the artwork?).

The meeting lasted for two hours.

We introduced ourselves, we introduced ourselves, we introduced ourselves.

On Zoom.

All we did, in fact, was introduce ourselves. Offering our faces to each other, our names, our situations within the institution (student, staff, which department, which programme); bits of information about our work.

Then someone said (at the very end): You know what?

I hate group discussions.

Moss

Body // Pink Moon // 06/25

Jodie Whitchurch

Ginger, Zingiber Officinale. Fire-taste, nausea relief, antioxidants, anti-inflammatory compounds. Willow, Salex. Inflammation, liver assistance, metabolisation. Avoid histamines. Cramp bark/Guelder-Rose, Viburnum Opulus. Pain relief, nervous system relaxant, uterine pain management, harvested in spring, of the old world.

Pink body. Tenebrous green. Letters.

Moss from armpits, knee bits, neck cyst, under-breast, ear canals. I wear my condition like a light jacket on a hot day, aware the temperature might dip any second as the entity speaks. Full, strawberry moon, 11th June. Truth, sweetness, energy of coming to.

They are for your tongue, the fruits. Red cabbage on the stove simmers. Seven days in, the form wishes to dive out of the pot and close the divide. I see the name of my hometown in a presentation. A muscle sneaks forward in my mouth, supressing exclamation. A fly frets somewhere behind my head, asks me to reluctantly turn. You should never meet the eyes of the thing masquerading to be a familiar demon.

Last quarter, 18th June. Past. A natural moment, a break in potency. I made a mistake in rinsing the purple with detergent. As a result, saturation succumbs to false scent, pan rust, fade.

Litha, 21st June. Light, abundance, gratitude. Look, all you have been waiting for.

I spread my palms with honey and face the sun. I move to catch winged species and come back with a handful of ants, all ready to do a daily card pull. The last time I did so (Beltane), the cards told me to use my intuition, to figure it out myself. In deference, I took offence and haven’t consulted them since. You caught me here once, wrist deep in salutations, knitting needles in the crook of my arms, yarn strung between my teeth.

The body that sits still for so long, an amalgamation of mosses grow.

Yarrow, Achillea Millefolium. Folkloric, flower and leaf, a reduction of heavy bleeding. For bloat: Chamomile, Fennel, Mugwort, Probiotics. Matricaria Chamomilla, Foeniculum Vulgare, Artemisia Vulgaris. Anaemia: Nettle, Dandelion, Vitamin C. Urtica Dioica, Taraxacum Officinale. Joint pain: Nettle, Omega 3. Urtica Dioica. No cure. Hormones. Synthetic Progesterone. Management techniques, lifestyle changes.

Girlhood, dysfunction, berries left too long at the back of the fridge. The thing that grows and grows and grows until taking over.

Own origins lost. Those that could have been asked, gone too long to answer.

Finding different ways to bring griefs back as apparitions. I use the knitting needles left to me by my grandmother in a wooden chest my grandfather built and varnished. I knit their presences into the room.

I pull grand ideas into a dome. The terrarium condensates, breath fogs until I drop the cards, tether points strewn across the veneer floor. They ask me to stop standing in the crate.

A lack of focus for a moment loses space on the needle. A whisper in the back brain murmurs, no, you were right, do that again. Becomes ravelled and unravelled, closer to sponge green, organic form.

I count as my hand does the motions, looping over and dropping, looping and dropping, looping and dropping. Fuzz, gradient, planted flag, pink moon.

Taken into orbit, led by the bottom lip.

If our brains are rotting, they wish to be seeping into the earth, nosebleeds running chlorophyll green. Desire for sensory moments curling; fingers smoothing through grass, tinged offseason at the edges. The inside joke is… we’re all books on a table. Depends on where the tissue grows.

An ignored twelve-month review cycle. Tiny ecologies. A small inside. Your chest thuds fists against. Something desires to get out.

Swallowed whole, throat leaves, ancient practices with modern medicine. Cinderblock rows of prescriptions contrast tinctures, glycerine, dry herbs and tea blends. Apothecaries for reducing mass cell deterioration. California Poppy, Eschscholzia Californica. Flowerhead and leaves, reduces anxiety and long-term stress, analgesic, adrenal tonic, works well in conjecture with Hawthorne for insomnia formulas.

Chasteberry, Vitex Agnus-Castus. Balance, neuroendocrine pathways, reduction of infertility and fibroids. Asparagus, Asparagus Officinalis. Warming, reduction of oxidative stress, immunity. Five-Flavour Berry, Schisandra Chinensis.

The body gives me small predictions. Next week it will rain. Tomorrow, you will feel this in your lower intestine. Root to be taken as tea or tincture. Timing is everything. They got on the boat, the cards spent their life in the attic, unfinished. Each sprig is plucked, held to lips, pulled as a loose hair from a rainforest. Come, here. One strand climbs higher than the rest. Here, come.

They’ll find me in two thousand years, beneath the ice, preserved just so with the mosses. I’ll be spiralled in on myself, hibernating despite the temperature.

25th June, the new moon finds us. Sea body, ice body. Slipped silk. Submerging, a something to wade into. Light jacket season. We plant our seeds, separated by only a week.

Roots: Dandelion, Burdock, Turmeric. Taraxacum

Officinale, Arctium Lappa, Curcuma Longa. Milk Thistle seed, Silybum Marianum. A portion of issue rests within the gut, another in the liver, pulled and cleared.

This is not a confession & Split Ends

Lu

Pinzi

The ruckus Rebecca Meanley

Agnes has drawn this part of the mesh. We sing and dance along the lines as we bask in the sunlight breaking through the surface of the water. It is warm just beneath the surface where the sun heats the water and forms hazy patches of bleached blueness. We bask just beneath the surface and we see many others, other selves, on their own lines, on their own lines just beneath the surface of the water. We are all waiting for something to happen, it would seem. At this particular point we are all just bobbing beneath the surface of the water, just below on the lines, but fairly static. We are not in rapid motion, we are hovering on our lines, we can even be between points or between intersections— we are hovering you see, we do not need to be at a point of intensity as we realise we can be bobbing up and down a little, just treading water, perhaps lying on our backs and swishing with our hands and arms, gently moving our legs in the sunsoaked warmth. Movement so slight just enough for a hovering, a fluttering, a shimmying.

I am quite happy at this point. The Agnes Martin painting allows me to rest for a while without the immanent urgency of coursing along at high speed. I am aware that if I do progress along my line it will make everyone else move also, everyone else will have no choice but to move. My movement forces the movement of others as we are all interconnected in the mesh. We all know this and we all know that we are interdependent as well as to some extent independent. But if anyone shifts significantly it sends

waves across the surface of the water, impregnating downwards, sending waves beneath the surface, activating a current or force through the water and we will all have to move suddenly as the dynamic has shifted. We move and we are immediately conscious of our motion causing a ripple effect and we are thrown deep into the water to find other points on lines much deeper in the darker regions of the sea.

The depths of the sea are much darker: a Prussian blue, a deep Phthalocyanine blue, so deep we may not easily see each other as we dive down in the mesh as it is immersed in the infinite depths of the ocean. I am much colder here, the surface was warm but the depths of the sea are cold and dark. I do not wish to stay down here but I must navigate this. Perhaps a way is through colour, perhaps a way to understand the immersion into the depths is not necessarily through dark memories but through thinking about mixing colours on my palette. I am very good at mixing pigment—from its raw materials—from the powdered pigment. Agnes struggled with colour I imagine; she did not use a lot of it.

The line you are on is your line for this particular present— another time and another line might be the one you occupy— there are many other lines. Be careful here that you do not become too rigid or assuming about the line you are on. You should perhaps be more open and sharing in the way you conduct your passage on this line. At the junction you arrive at you must slow down to almost stop at the point—the intersection with another oncoming line.

‘I have to breathe for a second,’ she thinks. Here, I meet another thought, another memory. On the line is an intersection—a point of intensity—a point of meeting with something else—with myself on another line—I have been journeying for a long time it seems and my legs are weary.

Suddenly there are many other intersecting lines all coming close together that form a bunching-up, a crusting together of blobs of matter. Matter suddenly becomes viscous and sticky like white sticky rice all stuck together or cancer cells all stuck together in the forming of a great mass. I find myself momentarily stuck at a junction: here I have a memory of cancer—of finding out that the cancer I had was the type that burrows itself into healthy flesh and eats its way through it, jumping some distance from one once healthy cell to the next, devouring healthy flesh—not the type that goes across the surface of the skin but the type that dives straight inside. Here, I am buttressed against a post of intersections in the mesh where a great mound of cancerous flesh has exploded itself across various lines. I am trying desperately to move through and beyond the cancerous zone.

You forget about A as you hurtle towards B but B is not the only place you are going and in fact B is now forgotten as you zoom very fast towards C—yet C is really not a place to stop for long as you catch sight of the beautiful blue sky out there today and decide that moving on to D would likely be a warmer more comfortable place for a sit down and a cup of tea perhaps? A cup of tea at D takes a little while as at point D there is a conundrum occurring. An event appears to be happening—which you might add was not happening when you first arrived at D, but after a little while an event definitely seems to be mounting—an energy is building and others are joining you at point D. What was a calm reflective moment, a subtle quiet moment all alone, where one can examine a subjective state of mind, suddenly becomes intersubjective or even rather rudely shared as an experience— one which you have not really wanted to share at all. Yet, everyone seems to be turning up at point D. There is a ruckus, a disturbance and somebody got hit or fell down spontaneously and suddenly there is a collective need for a decision to be made. What was the event that took place: Did anybody see what happened? We all saw it to some extent, but others might have seen what happened from a different point of view—others might have seen it differently. So, everybody’s account of the event is

important—important so as to form a collaborative effort at depicting the event, so it could be uncovered what happened, what went wrong.

The cancer will not infect all criss-crossing lines—we think—if we can move beyond, through this quickly enough we will not get cancer, we will not get HPV if we move very quickly and hose ourselves down in the shower—very quickly. “Ah my dear, not that type of cleaning—not that type—that won’t help you, dear.” I have long thought that at some point the cancer would come back—“There are a great many lines to go down there, my dear, there are millions of lines which tell us about the cancer.” I have, however, realised that although the cancer occupies this conglomeration of points, I am also experiencing the thoughts that oscillate around the cancer: the body that moves—the body that dances—the body that lives on despite the threat, despite the past—the body that moves to write—the body that paints— the body that also dances in the studio—crushed-up against this point of intensity—is also life.

Postcards

Glasgow Botanical GardensSunday afternoon - 1 to 4

Algaé D. Mouriaux

No One’s Home

Eilidh McDade

Hello again,

How are you? How is your family? Are you well? Did you take a walk this morning? Are you in love? When you wake up, does your bedroom lamp cast a light so bright you cover your eyes, shy away from it?

I’ve been playing cards lately. Going for cold swims. I bought a calendar. It helps me keep track of the days better. I’ve been buying flowers for the table. Drinking lots of wine. Making prints in the garden. Working here and there. My mother has sold the house. I’ve been spending the last few weeks writing eulogies for the floorboards. Kissing the bannisters.

They found out that the circuits under our feet are faulty. The surveyor called it a category three. If you plug the kettle and the toaster in at the same time, the wires trip and the rooms fall into darkness. When it happens we light candles and play charades in the shadows like it’s earth day. You see, I cannot leave a light on for you. You cannot find your way back here. Like me, you will stay homesick for somewhere you know you cannot return to.

I’ve been painting the walls white. Fixing the hinges on the door frames. People have been trampling in and out of this place,

pointing out the cracks in my bedroom walls. As if I did not grow up here. Drew faces in blue marker on the stairs. I think you should know,

I will dream about this house

Long after I have left it

I will return here in my sleep

I will linger in every room.

(shell to ear)

Maeve Dolan

(shell to ear)

I am clasping elaborate conch to ear (like I used to do)

I thought that I may hear the sea but there is only wetness at my tragi someone told me the swooshing or the currents you feel is the sound of your own blood (inner sea) something like that capillaries as tributaries journey, flood into fluid mass or whatever you would like to call a sea fathomless in my ear, sound waters

sometimes I sleep soundly eyes like shells all curled

swooned under eyelids (strange sleep)

I lie at the seabed feel the wash past my eyes they sting in the salt glisten in wavering light— blue is a tranquil colour, sometimes tranquilises; sometimes it is deep and cold and wet, like a sky— bubble closed lips in the salt, eyes sting— hair, sleek slippage like it has no place in water or every place in water, flowing all over with no interest in my hands, it likes the gaps between my fingers

tousled sand, grit of sleep all over my back, I toss, aimless

seabed settles under fingernails— closed lips bubble nibbling flicker of light, in wet refraction obscured cold to touch, I bite toothless bubble lips: closed.

(a dream)

waterlilies float indistinctly and increasingly so with nearness spread into indigo trembling— warm aura licks the face evaporates as ashes flakes distant heat— whelms blue, into petals flickering into nothing, precipitate still

oscillates fervently— (uplifting)

how strange a feeling

a place which I am not hold onto something perhaps I am there in pace, h h hand to face stand in kitchen, self-embrace hold still, hold an acquaintance with pulse— in noticing, steady lift up out of normal, out of plain state

…

I i fear i am losing form— like delight collected, into tear (echo)

she meets solid in a glimpse of quickening scudders fingertips across my lips, spider’s legs to my temples, her whisper bounces in its sameness— tracing me softly.

Excerpts from a hybrid-fiction

Eilidh Akilade

SubmitCross

Semantic sounds like somatic. She taps her feet against the ground, feels the salt and pepper carpet reach for her damp trainer soles. The rain has not let up all day. There is, I guess, still some room in the Programme. Maybe some afternoon later in the Festival, in the gazebo? the Programme Manager says. She takes a sip of her coffee. Excellent! The Festival Director thrusts his hands outwards, leans back in his chair. We’ll need to chat lighting. The Programme Manager makes a note. She is dutiful to her line-manager and makes a note too, although she is not sure of what. It is agreed, then: the Programme team offer slow nods in confirmation. He has chosen 4pm on a Friday for his own ease, she assumes, and their waning, their easy submission, is guaranteed. He heard about it from an Artist in the south— she was striking, so passionate! Comes from a fascinating background—a very interesting heritage, so different to what we’ve got over here. Really diverse stuff. She clenches one thigh: then the other. And no, no—he is certain. It’s semantic, not somatic. The Literature Programme Director puts her phone on the table and the tap of screen to wood conceals a sigh—she will think of a poet, who is also an academic of sorts. This, she says, should not be hard, because they all have PhDs, don’t they. The Art Programme Director will think of some artists working with sound and space. Someone will know someone, his ex, maybe—it is easy money, he supposes. And you’re sure it’s semantic? The Festival Director assures them, just once more.

Let’s not dwell on semantics, ha! She gives a short laugh and it is too loud so the Programme team look elsewhere. She rubs her thumb across the back of her palm. The skin pulls, then gives. Thanks, team—and let’s try to get a range of cultures involved in this, yeah? says the Festival Director. His delight is strained, Botox allows the eyebrows only so much upwards stretch. Fab! His hands slam the table and her resting forearms take the heavy surprise. The Festival Director would like to schedule a semantic soundbath and he is really very excited.

SucceedCross

The semantic soundbath is a success. Critics call it revolutionary, a vision of a world yet unformed. It is transcendent yet profoundly and distinctly earthly. Claims for gazebos as radical spaces, through which we may think through and of and with. And in, too. Nothing quite like it. Many depart the semantic soundbath tearful. They speak of their mothers and the climate crisis. The Programme team have few words—semantic, somatic or otherwise. It is near impossible to run. Often, the high voltage bubble machine ceases, sputtering with defeat. Cellos untune themselves due to stray strips of fake fur. The Poets— who are also Academics—cannot decide which thesaurus to use and change their minds after six hundred copies have been ordered and delivered. The Artist requires participant details in advance; they send emails the morning of, forget to bcc and risk the Festival’s GDPR guidelines. No matter. Hashtag semantic soundbath finds its way on to a former DJ’s Instagram story and a Private Funder faints sixteen minutes into the session, waking to announce a two-fold increase in his annual donations. The Festival Director is delighted. A triumph of the English language—and every other language—the critics are calling it. This excerpt is from a work-in-progress.

knock Rosie O’Grady

Some things are known intuitively, or because of a silence. Her period is late by a few days. The delay is not significant, but the dull ache that usually signals the onset of her cycle is strangely absent. On the first of April, she buys a test from a chemist.

Other things can’t be seen, but are known through sound, or smell. There are rats living in the wall.

One of her first thoughts when the blue emerges is: the child will be feral. To raise a baby in proximity to rodents, for the baby to become familiar with how they haunt the walls, surely will shape their psyche. She presses her ear against the plasterboard, then presses her phone against it and makes a recording.

Other realms exist, even though they cannot be seen, or are only witnessed through her phone screen. There are atrocities being enacted against whole civilisations as she boils a kettle in her kitchen. These discrepancies are dizzying.

The woman does not find it easy to share her news. To announce the pregnancy aloud feels like cliché. She admits, instead, that she has rats. She talks to the rodents, knocks on the wall, and tells them that they have outstayed their welcome, to clear off.

She is walking about the apartment with a towel wrapped around her waist, scrunching wet fists into her hair. There is already nausea, changes visible to her chest.

Knock,

The bathroom is a small L-shaped space. Along one edge, it is the length of the bath. She is not sure when the idea came to her, but the woman has fixed her attention on a new scheme. First, she must lightproof the room. A crest of light breaches the lino floor from the hallway. She seals the rim of the door with sponge tape. On the wall, she installs a hinged rack and rigs up a large rear bike light to provide a red glow. She puts up a hook for a plastic apron, and tucks a box of disposable gloves, beside cotton buds and dental floss, on a shelf. She buys two plastic funnels, a cylindrical measuring flask, a thermometer, and three pairs of silver tongs with rubber tips. Above the bathroom mirror, she hangs a red digital clock. Online, she sources three plastic trays: one red, one white and one green. Each has a lip in the corner, for pouring away or returning excess chemicals into their respective container. She purchases developer, stop-bath and fixer.

Someone says to the woman: seeing a rat is a good omen for fertility. They breed fast. In her fruit bowl, the lemons have turned hard. The woman tests the exposure of her bathroom light, pulling the cord on and off for different increments of time. She watches the seconds closely and writes the duration of exposure in pencil on the reverse of each test strip. The smell of the stop-bath brings on waves of nausea, as she agitates paper in the fluid. She washes the prints down with her showerhead. The woman is stooped over the bath, rinsing away chemical residue when her phone rings. She has taken it off aeroplane mode, and the bathroom light is on. It is a friend, returning a call. You said you have a dilemma?

In each room, the woman fits a socket with an ultrasonic pest deterrent. The high pitch they emit is supposed to make the space hostile to rodents. This does not seem to quieten the rats.

A friend reports that she had access to a portable veterinary ultrasound machine, and used it on her uterus. The woman is not sure whether this is safe. Her research diverges into other applications of ultrasound: the sensor for automatic doors; measurement systems for blocked pipes; and detection processes for faults in metal, or objects submerged in water. Fluid registers black, whereas tissue and other solid materials show as white,

or gradients of grey. She learns that high power ultrasound is employed in killing bacteria in sewage and cleaning surgical instruments.

Working under the red tint of the safelight, the woman is gradually making photograms. From a cardboard folder, she removes the stiff black plastic envelope, and from the envelope takes out one sheet of photographic paper at a time. She doesn’t yet know what image she is going to make but eases herself into the process by gathering waste materials from the kitchen. She stretches out the netting from a purchase of tangerines, holds it flat against the paper beneath a pane of glass.

Each night in the bedroom there is a faint scuffing sound behind the window boxing. It shifts behind the skirting and edges into the shadow space between plasterboard and brickwork. She sleeps with the light on, and her sleep is disrupted. She lies awake in the small hours, watching the clockface, lamp keeping the nudge of darkness at a comfortable distance.

In a dream, she sees all the women she has known to have miscarried. They are stood in a circle, each with an infant strapped to her chest. There is a legend, she remembers, about a rat catcher who clears a town of an infestation by playing a magic pipe and drowning the rats. When the townsfolk refuse to pay him, he leads the children with a melancholy tune, out of the town to a cave.

The next morning, she receives a phone call from an unknown number. It is the city council pest control department, responding to a report she submitted online months ago. The agent can attend her flat the following day, if she can first cut a square, approximately eight inches in width and height, into the plasterboard. The man on the phone says: about the size of a cat-flap.

For the task, she wears blue disposable medical gloves, a dust mask and goggles. She has read online that cat litter should be avoided during pregnancy, because of a risk of exposure to toxoplasmosis, which in turn is contracted from small rodents

and birds. Before making the intrusion with her drill, the woman raps her knuckles up and down the height of the wall. She directs a torch through the small circular hole in each corner of the square that she has measured out, then connects these points with a jigsaw. Over the prepared hole, she screws a board, until the agent arrives.

In the garden, there are two black cats who prowl in the long grass. Only last year, one was a kitten, now both fully grown. The brickwork of the opposite flats is infused with an amber hue. The man brings blue seed in a tray and leaves an information sheet with a skull and crossed bones. After his departure, she takes the disposable gloves into the bathroom. She lays one beneath the glass. The image it produces on the photographic paper shows creases and layers, where light has penetrated through the nitrile. She begins to think about transparency, takes a bar of translucent soap and exposes it on a sheet, revealing streaks and fingerprints.

Her worst fear is returning to find a dead rodent within the flat. A vertical pigmented line emerges beneath her rib cage, intersecting with her belly button, and continues to a point.

In the twelfth week of the pregnancy, the woman attends the hospital. On the way to the appointment, she remembers that she was instructed to drink a pint of water beforehand, to create a window through the fluid to the foetus. She drains her water bottle in successive gulps at each traffic light for the remaining route. There was an image online this week:

The hospital here is fully functioning, no screaming, no spilling of blood, no climbing over rubble to reach reception, no white kite flying above.

By the time she slides onto the bed in the clinic, there is a pressure in her bladder. A disposable towel is tucked like an apron into the front waistband of her trousers. The room is dim, drawn closer by a pleated curtain around the bed. Softly backlit, a violet hue is cast through the scrim. Part forensic, liminal, time

feels suspended, an existence just within the visible spectrum.

It is unlike any previous experience in a medical setting. One winter, the woman’s sister took her to the observatory at Greenwich. In the planetarium, the seats reclined, a concave projection overhead looping the solar system, its many moons. The sonographer applies a cool gel to her belly. Light from the monitor suddenly throws a monochrome haze across the room, the probe is gliding over her skin. There, illuminated on the screen is an image: not craters—a baby. Head, torso, the shadow of four limbs.

The woman laughs! It is a spasm of relief, and surprise. Her diaphragm jumps, her abdomen jolts downwards. The silhouette of the foetus is squeezed, momentarily lost in static. The woman exhales with control and the sonographer relocates the curved torso, the halo of a skull. The woman had readied herself for this image, but the movement of this small body takes her aback. So unlike the ubiquitous flat pattern of a scan, there is life. She senses the chasm between a plate documenting the frozen moment of a horse in gallop, versus a restless horse in the wild. There is kicking and lurching in her uterus as pressure is applied from above. The woman is watching, trying to connect the animated image with her body. A cord runs from probe to computer, across the hospital floor to a metal trolley, wired to the monitor. She studies the foetus. The sonographer is speaking about the rate of the heartbeat. Like a guineapig.

Time is suspended, and yet the image defies this—dancing, lurching beneath the transducer. Outside this reality, twenty protesters are fasting, each for forty-eight hours. They are mothers, horrified by facts that should be headlines:

14,000 babies could die in the next 48 hours due to starvation

As she wipes away residual gel, the sonographer prints four images on flimsy reflective film paper. The woman handles the prints as if they are the foetus itself, who might be bruised by a fingerprint. They are approximately to scale. Later, she secures

the images with magnets to the white sheen of the fridge. She photographs them, and messages a friend. A new photography project! The friend replies: sculpture, no?

There is a steep ascent to the Sumatran tiger enclosure. Her friends are already at the zoo and send their location as a red pin on a map. She is breathless from the uphill walk through the site. The results from a recent blood test revealed low iron levels and the woman has been advised to avoid quinine, cranberry, aspartame and tahini. She should also take two sachets of iron-rich water per day. Her breath tastes metallic. Arriving, her friends are animated. The sanctuary is bisected by a glass corridor, and they have just witnessed one of the tigers climbing on top. They show her photos: the white fur of his belly, the split black stripes. She has missed the spectacle, and the tiger has gone into retreat. She scans the site—large foliage, fronds, and high birch branches stirring with a breeze—different geographies and vegetation brought into proximity. A Perspex sign highlights that the tigers are critically endangered.

The main organs of the foetus are now fully formed. The woman usually only looks up the developmental progress one week to the next. It feels like bad luck to skip ahead. Nonetheless, her website search history betrays the fact of the pregnancy and now her browser is infiltrated with advert banners for breast pumps, and videos about swaddling, surpassing the pregnancy. Around week thirteen, she is shopping online for a second-hand dress. Amidst the clothes, there is a small icon showing a fanned pile of printed cards. Each displays striking black and white prints, simplified geometries. The caption: 20 flashcards. The woman has seen these before—high contrast images for newborn sensory development. The pursuit of a dress is immediately forgotten. The woman paces about her flat. She picks utensils from the jug in her kitchen. A corkscrew, a cheese grater, a slotted spatula. She gathers a bunch of keys. From a sewing kit she takes zips, buttons and a pair of scissors.

The medical websites draw approximate comparisons with soft fruit. In the first few weeks, she kept saying perhaps it is a whole

punnet of apricots. The foetus has hair follicles, is measuring roughly the size of a kiwi, then a peach. She imagines the same comparisons could be provided with insects, small mammals. At the clinic, the midwife says that they will use a Doppler ultrasound monitor at the next appointment, to take another reading of the heart rate. The woman switches the radio on. A flotilla is carrying cargo of flour, rice, medical kits and baby formula. The activists on board are attempting to breach a border and deliver this humanitarian aid. It is not the first attempt to break the blockade.

The woman is researching films set in a single room or location: a bunker, a jury room, a canyon, on a life raft, a hotel, in a restaurant, inside a car trunk, a maternity ward, on a bullet train, in a coffin, a darkened room, a convenience store, a police station. She eats in the flat and watches a live webcam of the Sumatran tigers from her laptop. The tigers are camouflaged, or not within the frame. Sometimes she is disturbed by a noise produced within the flat, mistaken for a rodent; the rapid descent of water through a bathroom pipe, the drag of the bedroom blind against the windowsill, moved by the suction of a breeze.

The foetus develops a fine hair across their body. Eyelashes and eyebrows start to form, and they become sensitive to light. For the first time, it begins to detect sounds—the woman’s heartbeat, digestive noises, and her voice. At choir, the woman notices a shifting in her lower abdomen, holds a palm to the hem of her t-shirt as the tenor and bass harmonies surge. She learns that rats can laugh.

The woman is jolted awake on her sofa. A podcast is still playing from her phone. The presenter explains that studies performed on mice and rats have revealed changes that occur in the pregnant brain. Her worst fear is that the foetus will not survive.

In the sixteenth week, the woman feels, with increasing certainty, movements of the foetus. It passes as a light quiver and a change in pressure that could almost be mistaken for movement in a

digestive tract. But its location within her body is distinct. It is evening, and she is lying sideways with legs extended on the sofa. Her hand instinctively goes to her belly in response, sweeps the swell of it in a circular motion. She finds herself returning to this posture the following evening, remaining stationary in waiting. It might be the time of day, or the hot drink, or the stillness that brings it on. The woman learns that this phenomenon is the quickening, historically marked as the start of life. In early law, it indicated when abortion could be tried as murder. The foetus does not yet have tear ducts, or melanin. Though it has been stirring for weeks, it is the perception of movement in the host body that distinguishes this threshold, recognises the foetus as a being. The rats move now with less urgency, their sounds heavy and lethargic. The woman is not sure if it is the light that causes the insomnia, the movement in her belly, or the sound of scratching and dragging within the walls.

At the weekend, she travels to a hostel with eleven friends. Three babies are monitored in their sleep along the corridor with remote devices. One friend says the pixilated image reminds them of an ultrasound. During the day, they walk as a group up a nearby hill. The grass is wet and slippery. Sheep are startled down a bank as the group scuff at paths, dislodge stones. Emerging from a wooded area, a small skull is found at the edge of a field. One of the men probes it with a hiking stick. It flips over, revealing its jawline. A red squirrel, perhaps?

At dusk, she walks alone from the hostel to a river. A gate takes her into a graveyard, where she looks at names, decorated in lichen. She frightens bats in the cemetery, fanning out from under the church eaves. They sprawl across the sky chaotically. A friend tells her that a man in the sauna reported that bats have been observed in the act of midwifery, supporting the birthing bat to hang right way up, surrendering to the influence of gravity. The next morning she has a voice message from the midwife: further blood tests are needed.

When she returns from the weekend away, the smell of death is pungent in the stairwell. The woman works one afternoon

from the flat, the washing machine churning in the kitchen. The midwife visits to take the additional blood. She removes her shoes at the threshold with such discretion that the woman doesn’t notice the gesture until the midwife is departing and pauses again at the door to replace them. The woman wants to apologise for the lingering scent—the rodents, the chemicals. In the bathroom, she has hung a series of photograms.

Now the cavity in the wall is quiet. The woman plans to fill it with expanding foam and wire wool. It remains silent for a week or so. She reads studies about abortion rates, which have increased. There has been a reduction in teenage pregnancies since she was an adolescent. She looks at other trends, learns about an evolution in American baby names: fewer that connote joy, love and benevolence. The status of names meaning intelligence is also on the decline. The names that are growing in popularity are associated with beauty and wealth. The woman is not yet ready to face the task of contemplating names, but in the new calm of the flat, lays a hand to her abdomen. She begins to quietly ask, who’s there?

Author Biographies

Eilidh Akilade is a writer and arts worker from and based in Glasgow. She is currently Intersections Editor at The Skinny and her work can be found in publications such as MAP, Gutter, Extra Teeth, and gal-dem, amongst others. Her debut pamphlet, Nitpicking, was published with Rosie’s Disobedient Press in 2025.

Kate Briggs is a writer and translator based in The Netherlands. Her books include This Little Art, an essay, published by Fitzcarraldo Editions, and The Long Form a novel published by Fitzcarraldo Editions (UK) and Dorothy, a publishing project (US). She co-runs the reading, writing and publishing project called Short Pieces That Move!. Kate was a School of Fine Art Practitioner-in-Residence between 2022 – 2023, hosted by Art Writing.

a.w. Cutler-Gear (aly/willamina) is a Ham Foula Shetland Islands/USA artist, performer, and computational humanities researcher working at the intersection of corpus linguistics, anti-colonial design, and post-studio practice. Lately she has been re-engineering textual infrastructures:activating machine learning, polyontological inscription, and historiographic countertechnologies:to surface situated worldings against techno-ontic violence. Recent shows include Theft During the Lairdic Era 1707-1886 at Market Gallery, Glasgow (2024) and a CHASE-funded performance/talk for Religion & Art Colab (Goldsmiths/UAL) at Holy Trinity Church, South Kensington (2025). She is a retired noise musician due to a neck injury though the spandex computer interface is in the works&water based code alteration system too!

Catherine Grant is Reader in Modern and Contemporary Art at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London. She is the author of A Time of One’s Own: histories of feminism in contemporary art (2022), and co-editor of Fandom as Methodology (2019), Creative Writing and Art History (2012), and the questionnaire on ‘Decolonizing Art History’, Art History, 2020. She is a co-lead of two research networks: ‘Group Work: Feminism and Contemporary Art’ and ‘Animating Archives’. Catherine Grant contributed to the Art Writing ‘Form & Field’ Intensive in November 2024, presented

with Curatorial Practice (Contemporary Art) and the School of Fine Art PhD programme.

Laura Haynes is a writer, editor and academic based in Glasgow. She was co-director of MAP (2011 – 2024) and at The Glasgow School of Art is leader of the studio-based interdisciplinary Master of Letters Art Writing postgraduate programme, where she also edits The Yellow Paper: Journal for Art Writing.

Maria Howard is a British-Italian artist and writer based in Glasgow. She is the recipient of a Gillian Purvis Trust Award for New Writing and The Yellow Paper Prize, and has been shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize and longlisted for the Ginkgo Prize. She is currently undertaking a practice-based PhD at The Glasgow School of Art and is a teaching assistant on the MLitt Art Writing.

Madeleine Kaye is an artist and writer based in Glasgow. Her practice is concerned with femininity, and all its awkward and shameful contradictions. Working with written and sculptural materials, she likes to trace intersecting citations and histories. She also researches scent and sense-making, and is forever attempting (and failing) an embodied olfactory practice.

Endnotes and References

Madeleine Kaye, A Mermaid Walks Over Vito Acconci’s Seedbed, pp. 17-21

Vito Acconci. Seedbed, 15–29 January 1972, Sonnabend Gallery, New York City. Madeleine Kaye. Photo of Starbucks coffee sold at Tesco, 2025, Glasgow, photograph.

Edvard Eriksen. The Little Mermaid, 1913, Denmark, bronze. Peggy walking to her new office with The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife tucked under her arm, Mad Men – Season 7 Episode 12 ‘Lost Horizon’, directed by Phil Abraham, 2015, Lionsgate Television, tv still. Hokusai. The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, ca. 1814, woodblock print.

J.E. Cirlot. A Dictionary of Symbols ‘Twin-Tailed Siren (15th century)’, 2001, Routledge, London.

Pinzi Lu is a writer and interdisciplinary artist from China working across text, image, and digital media. Her practice explores fragmentary writing, engaging with rupture, absence, and delay. Rooted in the tension between language and

embodiment, Pinzi Lu’s work moves between confession and concealment, memory and invention. Drawing on multilingual rhythms and diasporic sensibilities, she constructs intimate, fractured narrative fields through visual poetry, typographic experiment, and non-linear form. She is currently seeking ways to remain in Glasgow, or Scotland, or… somewhere.

Eilidh McDade is writer and artist from Glasgow. Her practice is concerned with reconstructing the relationship between writing and artistic practice, creating installations that treat language as a material presence within visual contexts. Her work incorporates photography, found physical materials, and text—engaging with artistic processes that evoke ephemerality and decay. Drawing on theoretical frameworks from memory studies, Eilidh’s practice explores how personal and collective experiences are held, retold, and articulated through the act of writing and making.

Francis McKee is a lecturer and researcher at The Glasgow School of Art. He is currently writing a book on Krazy Kat (1911–1944) and also working on a smaller project called Five Days of Demons.

Aglaé D. Mouriaux is a letterpress printer and art writer from Paris, currently based in Glasgow. Her written and visual work is interdisciplinary and plays with the materiality of words. She is interested in the construction of meaning as a collective process. One of her poems was published in the 81st issue of Poésie/Pemière in 2022, and she has created two letterpress sets for circus, contemporary dance and music show, Paroles (2024 and 2025).

Rebecca Meanley is an artist, writer, researcher and senior lecturer. She is currently pursuing a practice-led PhD at The Glasgow School of Art, where experimental, auto-textual forms of writing and expanded field painting are navigated within the visual-aesthetic-literary device of ‘the mesh’. Rebecca is a teaching assistant on the MLitt Art Writing.

Rosie O’Grady is a writer, artist and celebrant who was awarded the The Emerging Art Foundation Art Writing Prize and the Yellow Paper Prize for New Writing in 2024.

Margaret Sheehan-Gray is a writer and artist who lives and works between Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Jodie Whitchurch is an art writer, prop maker and scenic artist for theatre based in Glasgow/Nottingham. Her debut poetry collection Haven’t the Foggiest was published in 2022 by Big White Shed. She has contributed to Big Red Cat Zine, From Glasgow to Saturn and The Nottingham Horror Collective. Her pamphlet Moss Girl is stocked at Good Press, Glasgow. She writes, knits, convenes with mysticism, beloved (though tiresome) ghosts, a persistent fixation with mosses and medicinal applications of plants. Her works traverse terrains of poetry, hybrid form, textile and exaggerated soft sculpture.

Art Writing Graduate Programme

The Glasgow School of Art

Passages

Exhibition and events programme presented as part of the School of Fine Art Postgraduate Degree Show at The Glasgow School of Art, 28 August – 7 September 2025. Featuring an evening of reading, performance and screening from the graduating Art Writing students at David Dale Gallery, Glasgow, on 27 August.

Class of 2025

Eilidh Akilade

Maeve Dolan

a.w Cutler-Gear

Madeleine Kaye

Pinzi Lu

Eilidh McDade

Aglaé D. Mouriaux

Margaret Sheehan-Gray

Jodie Whitchurch

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the students and contributors, The Alasdair Gray Archive, Cooper Gallery DJCAD, Cove Park International Residency Centre, David Dale Gallery and Studios, Fitzcarraldo Editions, Good Press, GSA Student Association, GSA Archive & Collections, GSA Library Services, The Hunterian Art Gallery, Mitchell Library & Archives, Move To Feel, National Libraries of Scotland Moving-Image Archive, The Poetry Club, Sunday’s Print Service, Kate Briggs, Duncan Chappell, Nicky Coutts, Anne-Marie Copestake, Sorcha Dallas, Karen Di Franco, Ingrida Danieliute, Olivia Douglass, Kiah Endelman Music, Catherine Grant, Laura Guy, Sophia Hao, Alexia Holt, Maria Howard, Ruth Kirkby, Esther Kinsky, Ailsa Lochhead, Julia Malle, Jen Martin, Mick McGraw, Mary McGuire, Neil McGuire, Francis McKee, Rebecca Meanley, Caitlin Merrett King, Lisette May Monroe, Emily Munro, Martin Newth, Dominic Paterson, Edwin Pickstone, Alison Scott, Max Slater, Nick Thurston, Kate Timney, Susannah Thompson, Gina Wall, Jude Williams.

The Yellow Paper Journal for Art Writing

Edition 6

Summer 2025

Editor Laura Haynes

Design

Neil McGuire, After the News

Editorial Assistance