Drawing Threads is one of a group of newly established research clusters at The Glasgow School of Art’s School of Design. A vibrant grassroots 2022 initiative, the clusters bring together colleagues from a range of specialist design departments to share inter-disciplinary approaches and enquiry across design history, theory and practice. Events we have organised include studio workshops, visiting professor lectures, talks by recent doctoral students, symposia and conference activities, for example, the 2023 European Academy of Design conference held in Glasgow in partnership with the Edinburgh College of Art / University of Edinburgh.

Pulling on shared threads of interest across silversmithing, jewellery and textile design, Drawing Threads develops collaborative approaches to studio research, through a rich experiential, technological and craft enquiry. Our group explores the boundaries of existing studio-based practices and asks how overlapping yet distinct disciplines can bring a new understanding of a subject’s shared material craft heritage.

Re-inSpired is the Drawing Threads Clusters’ first group exhibition that features eleven of our staff and researchers’ work. Our members present designs from donated sheets of the 1960s anodised aluminium metal cladding removed from the sculptural spire of St Michael’s Church, Linlithgow in Scotland, during its renovation in 2024. The spire, known locally as the ‘Crown of Thorns’, was designed in 1964 by the British artist Geoffrey Clarke. The provenance of the site’s material, history, and heritage has offered rich and fertile territory to explore diverse ideas, including value, sustainability and sense of place.

Urban mining is a term credited to Professor Hideo Nanjyo of Tokyo University Research Institute of Mineral Dressing and Metallurgy in the 1980s. Urban mining refers to the recovery and reuse of valuable materials from waste, such as electronics, concrete, bricks, steel, roofing materials, copper pipes, and aluminium. Linlithgow's original gold-coloured aluminium cladding had spent over sixty years exposed to Scottish elements and steadily weathered, changing patina, surface, and colour from golden yellow to its underlying

grey and silvery finish. We might compare the process of maturing whiskey, a significant Scottish export to the world, where casks are left to mature for ten to forty years or more. Some of the cask spirits are lost to evaporation, estimated at 2% per year, and this is referred to as the ‘Angel’s share’, creating another spiritual link. This exposure time becomes an important ageing and maturing process that adds character values and ultimately worth. As makers, we support a process that values all materials in alternative ways through themes like time, space and narrative. This is increasingly important as precious metal prices reach unaffordable levels for many makers starting in business, and the environmental costs of mining and extraction are all too well-known.

The provenance of the site’s material, history, and heritage has offered a rich and fertile ground to explore a rich range of ideas around values, sustainability and sense of place, among others. Approaches to the project are captured in this catalogue with an essay by architect Brian Lightbody, who led the Spires restoration and funding on behalf of the church, and also expertly contextualised by Dr Jane Milosch, the University of Glasgow visiting professor. We are very grateful for the time and energy they and their colleagues have given to support this publication.

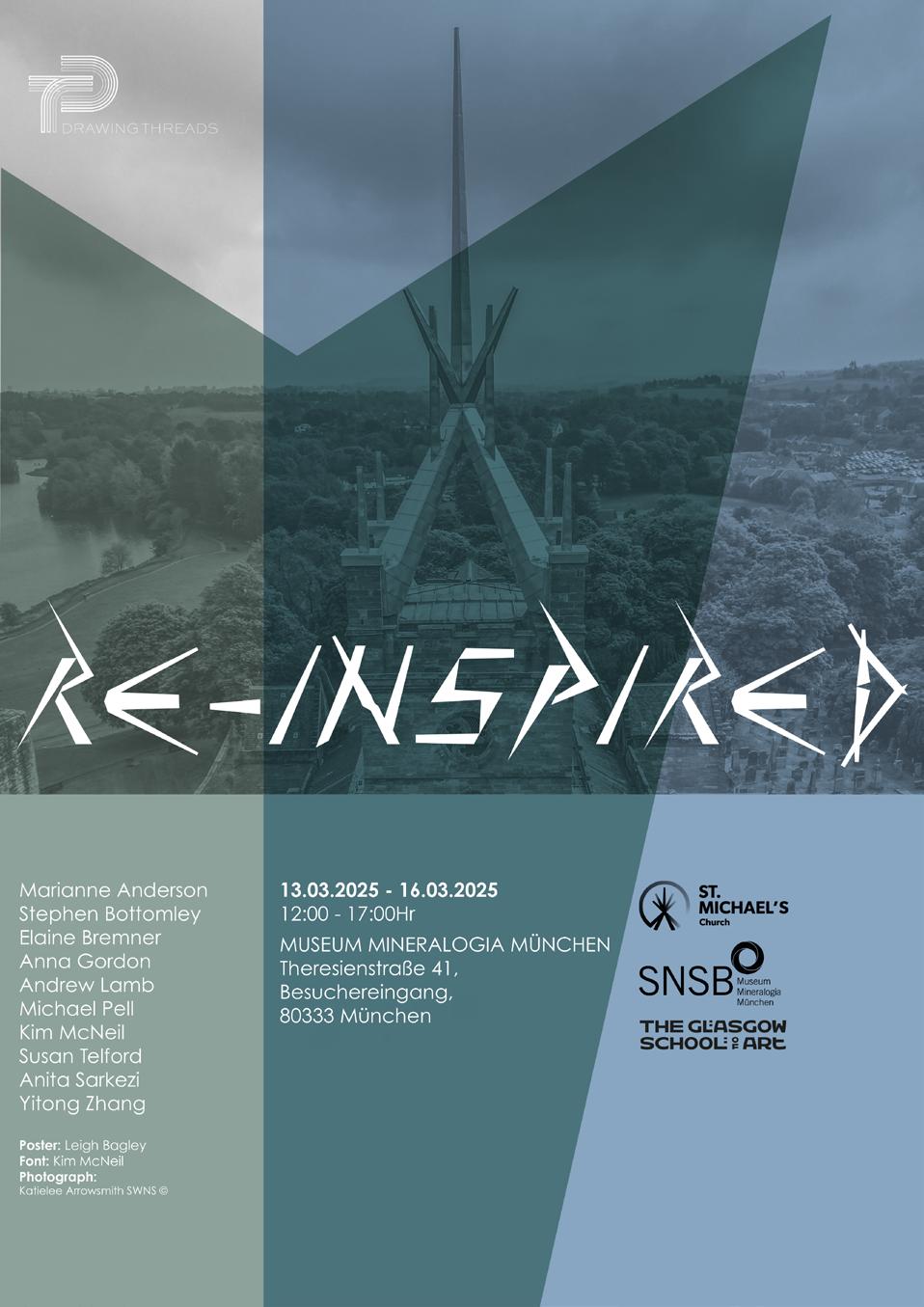

The exhibition first previewed in Munich during International Jewellery Week in March 2025 at the Museum Mineralogia München. The work was displayed within its permanent geology collection exhibition space, generously offered by Dr Melanie Kaliwode, Deputy Director and Senior Conservator. The exhibition then returned to Scotland to be shown In Linlithgow at St Michael’s church over Spring 2025, including ‘Earth Day’ on April 22nd 2025, when worldwide we considered environmental and sustainability issues and encouraged material recycling globally. In celebrating this day, we partnered with the Goethe-Institut Glasgow, the Institut Français Écosse, and ClimateCulture on events that accompanied their Cultures of Action that showcased the essential role of culture in addressing sustainability challenges through film, music, performance, and events through a programme of events over an Earth Month schedule.

The research cluster are thankful to Kirsten Davies and Brian Lightbody, who first approached us on behalf of St Michael’s church to see if there was an interest in having pieces of the original salvaged sheet metal—anodised aluminium cladding—to work with.

We are delighted to be re-exhibiting the work in the Pangolin Gallery in London this September, alongside the inspiring exhibition of Geoffrey Clarke works of art from a golden age of British sculpture that demonstrate his fearless experimentation with new materials and processes that continues to inspire artists today.

Professor Stephen Bottomley MPhil RCA, MA, BA Hons Head of the School of Design at The Glasgow School of Art Lead for the Drawing Threads Research Cluster

We are delighted to be able to collaborate with Glasgow School of Art and to host the exhibition Re-inSpired, displaying jewellery made from the old metal cladding removed from our iconic modern church spire known as the Crown of Thorns. It’s a great story of recycling, re-imagining and sustainability. Material that appeared to be of no value, and was heading for the rubbish dump after the completion of the refurbishment of the spire in 2024, has been given a new lease of life – pieces of one artwork now re-created as another.

The modern spire, designed by Geoffrey Clarke RA, replaced the original stone crown spire, completed in 1489, but removed in 1821 when it had become unstable and threatened the stability of the entire bell tower of the church. In 1964 the minister, Rev Dr David Steel, concluded that the bell tower had looked unfinished for too long and decided that a new stone spire should be designed. The noted architect Sir Basil Spence was consulted but he swiftly concluded that

only a lightweight solution was structurally possible and he suggested that a sculptor should be employed rather than an architect, and that Geoffrey Clarke, with whom he had worked successfully at the recently completed Coventry Cathedral, should be approached.

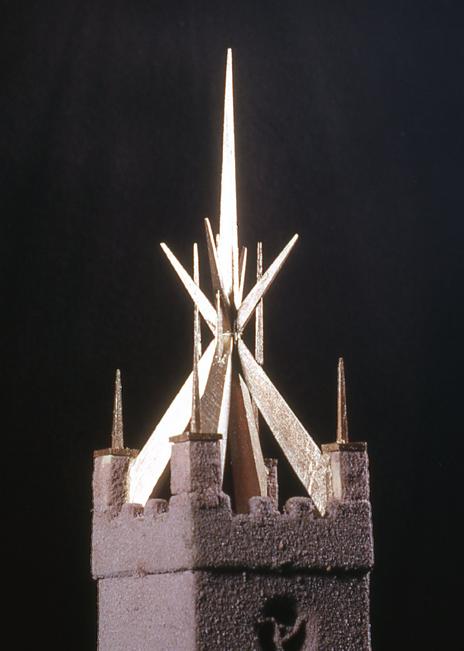

Geoffrey Clarke’s uncompromisingly modern gold design was accepted, despite opposition from some quarters, and the finished structure, although hugely controversial at the time, has over the years become the cherished, admired, and most recognisable feature of the skyline of the town.

Sadly the years of Scottish weather took their toll. The gold anodised aluminium cladding faded to a dull grey, the fixings corroded, and the resulting water penetration started to rot the timber substructure. However it was concluded that the crown could be repaired by cutting out the rotten timber, splicing in new sections, and re-cladding with a colour fast bronze alloy, gold coloured to match the original, and fixed with a modern secret-fix system. The funds were raised from multiple sources, most coming from the church and community, a testimony to the affection that Linlithgow has for its once controversial spire.

St Michael’s Parish Church is regarded as one of the finest late medieval works of gothic architecture in Scotland. Designed by royal master mason John French, the first phase of nave, bell tower and transepts was completed in 1490 and the second phase of chancel and apse completed by his son and grandson in 1540. For many years, because of its proximity to Linlithgow Palace, it was the church of the Stuart kings from James I to James VI and where Mary Queen of Scots was baptised in 1542. The ‘luminous’ vaulted interior is much praised and the window in the south transept, St Katherine’s Aisle, with its elaborate tracery, is regarded as the finest gothic window in the country enhanced by the glowing stained glass designed in 1992 by Crear McCartney.

The dominant stained glass central window in the apse of the church was installed in 1884 in memory of Sir Charles Wyville Thomson, an elder in the church and widely recognised as the world’s first oceanographer. His three year round-world voyage on HMS Challenger discovered what is till the deepest point in the world’s oceans – The Challenger Deep, and gave its name to the space shuttle Challenger.

Brian Lightbody BArch RIBA FRIAS Architect

Members of Drawing Threads Research Cluster St Michael's Church, Linlithgow, 2024

In the Beginning. When Stephen Bottomley and Anna Gordon invited me to join the School of Design’s research cluster, Drawing Threads, in 2024, I was intrigued by its makeup of artist-teachers and designers—silversmiths, jewellers, textile and graphic artists—and its interdisciplinary and collaborative approach to research and making. As a museum-trained curator I am interested in how historic and sacred artworks and architecture can inspire contemporary artists, advancing their research and work by sparking new ideas in terms of their use of materials, techniques, and function.

I am delighted to co-curate with Stephen Bottomley the Research Cluster’s first exhibition project, Re-inSpired, 2025, which will be on view in Munich, Linlithgow, and London, and hopefully travel to other venues. This exhibition does not have a permanent checklist of objects as the show will expand as the artists continue to experiment with the recycled 1960s aluminium salvaged from Geoffrey Clarke’s spire design for St. Michael’s Church, Linlithgow, known as Crown of Thorns (1964). Geoffrey Clarke (1924–2014), renowned for his ecclesiastical projects and cast aluminium sculptures, trained and worked in a variety of media. His innovative approach—to whatever

materials and techniques he used—resulted in original designs in stained glass, mosaics, jewellery, medals, textiles, ceramics, and enamels. His craftsmanship approach led to design solutions that were symbolic and expressive and make his work an ideal match for the Glasgow School of Art’s (GSA) interdisciplinary exhibition project. St. Michael’s Church—with its elaborate masonry, ribbed vaulting, stone tracery, stained glass, textiles, liturgical and sacramental objects—is an exquisite inspirational and visual resource for artists.

The Church. A mystical and liturgical image of heaven, it is a sacred space designed for worship and contemplation, an earthly glimpse of the heavenly Jerusalem. As Clarke’s father was an architect and his paternal grandfather a church furnisher, Clarke was aware of these symbolic and spiritual associations. St. Michael’s is a very active parish, and its services and charitable work bring the human in contact with the divine.

In January 2025, I was treated to a fascinating tour of St. Michael’s Church, Linlithgow—its long history and artwork—by parishioner and architect Brian Lightbody, who championed the restoration of Geoffrey Clarke’s spire. My visit was a revelation in many ways. This Gothic church dates to the 12th century but was largely rebuilt in the 15th century to the designs of the Royal stone mason John French and richly decorated with sacred art. Due to the Reformation these artworks were destroyed, save a sculpture of St. Michael on the Church’s outside wall. During the 19th and 20th centuries, St. Michael’s commissioned architects, artists, designers, and craftsmen to restore and create new artworks—stained glass windows, metalwork, and textiles, all of which can be seen today.

The Spire. Clarke’s sculptural design is a brilliant, stellar solution to what was both a liturgical commission and a structural challenge. This led me to consider: what were his inspirational sources; and how does this commission fit within his overall oeuvre? I knew that Clarke’s design reimagined what had been a stone “crown” steeple, but from my perspective it did not resemble a crown of thorns, and it made me wonder about the title. Two maquettes for this commission are illustrated in Geoffrey Clarke Sculptor. Catalogue Raisonné (Pangolin, 2017): one dated 1962 with a small cross atop the spire, and the other dated 1963 without a cross, and both are entitled “Crown” with no suggestion of thorns. After consulting with two Geoffrey Clarke experts—Peter Black and Judith LeGrove— about his inspirational sources, they indicated that Clarke had always referred to this commission simply as “The Crown”. Hopefully future archival research will turn up new evidence and shed light as to its now accepted title. Nonetheless, this title helps to make his abstract, spiked-shape forms more

easily interpreted as thorns, simultaneously associating it with both the biblical reference of Christ’s suffering on earth and with His heavenly crown of glory.

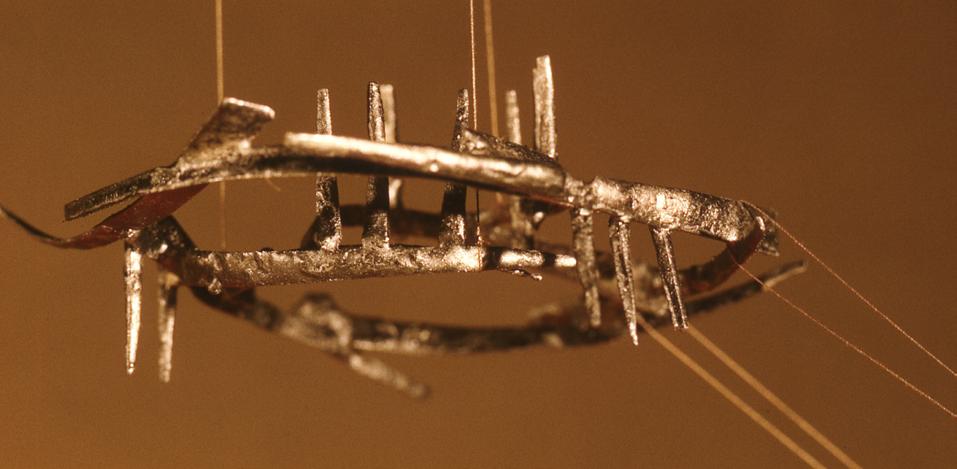

The Crown. An inspirational source that might have helped shape Clarke’s ideas for the Linlithgow commission is his Crown of Thorns (1962) designed for Coventry Cathedral. However, Linlithgow involved different design challenges—as an exterior versus an interior sculpture and needing to relate it to a pre-existing tower structure that could not sustain much weight. One of his maquettes for Coventry, Crown of Thorns (1961) is visibly what the title purports it to be, with its circular form and spiky projections. Thirty years later, Clarke recycled the silver electrodes he used to gold plate the high altar cross for Coventry to create Pendant (1992)—an example of how he revisited and reimagined his designs, materials, and techniques to create something new. This and another of Clarke’s jewellery designs, Neckpiece (1977), are fitting archetypes for the artists’ work presented in the Re-inSpired exhibition. The presentation of the GSA exhibition at Pangolin Gallery in London will include some of Clarke’s sculpture and prints.

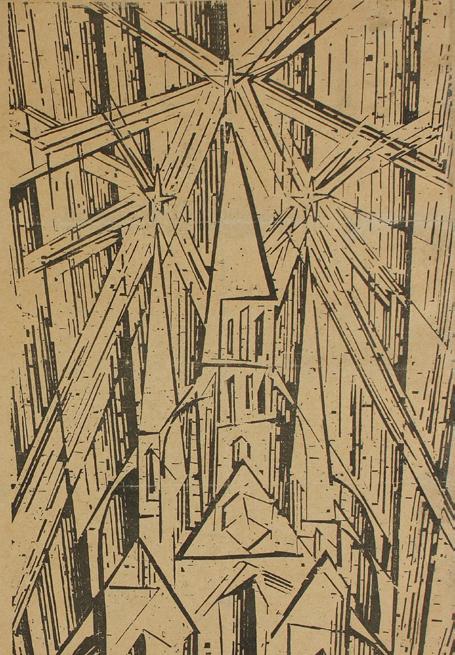

Though perhaps not a direct inspirational source for Clarke’s spire design, the woodblock print Kathedrale (Cathedral, 1919) by the German Expressionist artist Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) serves as an intriguing comparison. Feininger’s rendering of the church—with its dynamic rays of light emanating from the stars above the spire—symbolically connects the heavenly with the earthly, the supernatural with the manmade. Feininger was a teacher at the Bauhaus (1919-33), and his print served as the cover illustration to Walter Gropius’ manifesto for the founding of the Bauhaus (1919). Gropius chose Feininger’s Expressionist image as it reflects both the aura of medievalism and his pedagogical programme for the Bauhaus—new work springing from the type of training employed by Late Gothic craft guilds. Whether Clarke was aware of Feininger’s

Right: Geoffrey Clarke, Crown for St Michael’s Church, Linlithgow (maquette), 1963, balsa wood and gold paint dimensions and location unknown

print or Gropius’ ideas is uncertain, but he was interested in design education, new materials, symbolism, the spiritual, and admired the work of other Bauhaus artist-teachers, Paul Klee (1879-1940) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944).

In looking at the past and the present, Clarke’s oeuvre and the works by GSA artists in Re-inSpired resonate with parts of Gropius’ manifesto:

There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an exalted craftsman. In rare moments of inspiration, moments beyond the control of his will, the grace of heaven may cause his work to blossom into art. But proficiency in his craft is essential to every artist. Therein lies a source of creative imagination. Let us create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist. Together let us conceive and create the new building of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity….

Repurposed, Reconsidered, & Re-Inspired. The works made by the eleven GSA artists breathe new life into a damaged material that would otherwise have been discarded. Their 2025 Re-inSpired works take inspiration from a variety of sources found in and associated with St. Michael’s as a sacred architectural and functional space, including the church’s stone masonry, the organ’s metal pipes, candlesticks, woven and embroidered altar cloths and hangings, colourful stained glass, and religious imagery and ecclesiastical garments. Their artworks elicit questions about time, place, and memory, as well as what is tangible and intangible, ornamental and functional, personal and universal. Notably, just as Clarke collaborated

Left: Geoffrey Clarke, Neckpiece, 1977 Brass, leather, 150 x 90mm Artist's Estate

Right: Geoffrey Clarke, Pendant, 1992 Recycled electrodes, silver, Cumbrian slate, 52 x 55 x 10mm Collection of Jantien and Peter Black with other artists and craftsman, some of these works were made as collaborations, whether by design or in response to materials and techniques, expression and function.

Jewellery. Marianne Anderson’s Columnar Ring features the anodised aluminium of the spire’s gold cladding that was not exposed to the weathering of the elements; its shape recalls the church’s architectural columns, and the pearls suggest the ornamentation of ecclesiastical vestments. The result is a wearable ornament that is precious and sacred. Andrew Lamb’s Untitled Ring unites the recycled aluminium with the spire’s new metal, which complements and contrasts. Like Clarke, Lamb’s work involves casting and experimentation with different metals and processes, and his work is a conversation between expressive and symbolic elements, through bold and subtle forms and surfaces.

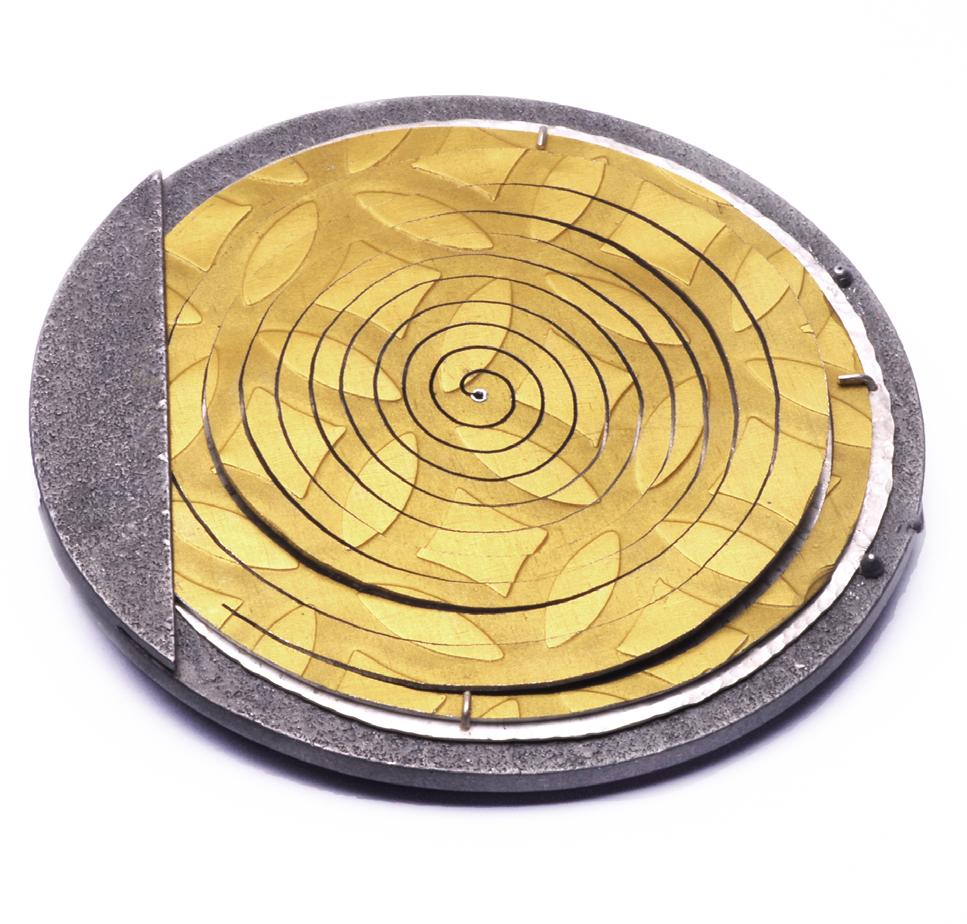

Stephen Bottomley’s brooch, In my End is my Beginning, commemorates Mary, Queen of Scots’ baptism and regal association with St. Michael’s. His materials and techniques meld the old with the new, and vice versa, referencing the temporal and eternal through his gold, pierced spiral design on the original anodised gold aluminium set within a contemporary solid sintered aluminium frame. The title punched into a silver backing plate is evocative of faith, “the evidence of things not seen”. Anna Gordon’s brooch, Time, garners inspiration from many things, especially the passage and weathering of time, both on materials and our perception of things. Through her use and manipulation of the anodised gold aluminium, she restages its history and transforms it into an iconic weaving of looped metal forms that move, recalling the impermanence of things and the glory of beauty. Michael Pell’s Decladation

Neckpiece, with its circular, weathered, and pierced disk was made from the recycled aluminium. Its smooth chain links of silver and gold bring the deteriorated metal into contact with the precious. Layers of religious symbolism and teaching can be culled from this combination: the damaged and discarded redeemed into something beautiful and useful, a supernatural take on the meaning of suffering and redemption.

Textiles and Metal. A collaboration between weaver Elaine Bremner and embroiderer Susan Telford resulted in Untitled Braid 1 and Untitled Braid 2. These works recall liturgical textiles through their use of materials, techniques, and design elements. They have unified the spire’s recycled aluminium with luxurious, fluid threads, and together these reflect the church’s layered history and space. Another collaboration between metalsmith Yitong Zhang and textile designer Anita Sarkezi resulted in Cloth Holder No. 1, a symbolic union of a textile cloth, metal candleholder, and wax—and hint at the visible and invisible, as we cannot see the holder in which the candle sits. We must take it on faith that it is there. The cloth’s luxurious gold threads reference the geometric forms of the spire as well as the church’s ornamented interior and ribbed vaulting.

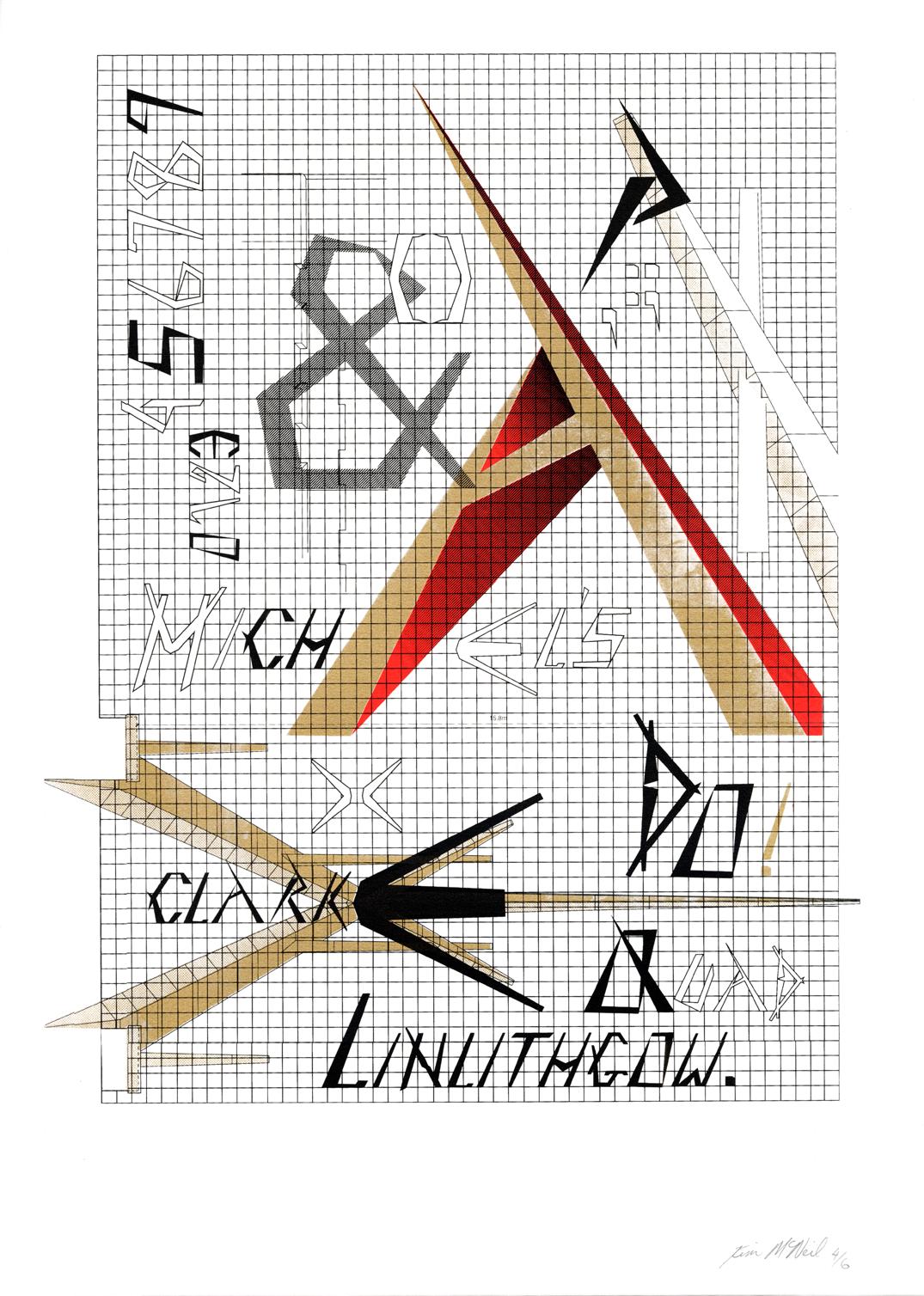

Graphic Design. Leigh Bagley’s poster design for Re- inSpired features a colour palette derived from the metal properties revealed by electron microscope scans of the aluminium, translating this data into colour attributes. The resulting blues and greens recall the sky and landscape that surround the spire. Graphic designer Kim McNeil created an entirely new font featured in this catalogue, inspired by the shapes and lines of the spire and the architectural drawings created for the restoration project. Her pointy and gestural font is an homage to the spire’s iconic status: a monumental, symbolic form that marks a sacred and historic place.

And he that sat upon the throne said, Behold, I make all things new. (Revelation 21:5a). All of the works by the GSA artists resonate with Clarke’s innovative and iconic design for Linlithgow, echoing and embodying his use of materials, penchant for experimentation, devotion to the handmade, and desire to create something new, reaching for the unknown with open eyes. I think he would have been pleased with this exhibition project and joined in too.

Jane Milosch, PhD Visiting Professorial Fellow in Provenance and Curatorial Studies School of Culture and Creative Arts University of Glasgow

Columnar Ring, 2025

Oxidised silver, recycled aluminium and freshwater pearls 50 x 50 x 30mm

Reflecting and investigating the architecture of St Michael’s, my research has focused on the columns.

Sacred structures hold personal significance for me. They were the catalysts that shaped my initial perspectives on architecture and ornament, influences that continue to resonate in my work today.

This work draws inspiration from various archives of ecclesiastical ornaments and motifs characteristic of the architecture and reliquaries. The columnal forms inspired an exploration into the geometry of their cross-sections while reflecting on their meaning beyond the structural support and in what they represent in a religious context.

The ring I have made serves as a tangible example of the decorative aspects of the column, translating silhouettes and architectural proportions of this aspect of divine architecture.

Marianne Anderson, Lecturer Silversmithing & Jewellery Design

The colour palette used for the Re-inSpired poster was derived from Aluminium scan data, which translated the metal properties of the sample into colour attributes.

This process employed both CMYK and RGB profiles, referencing CIELAB values, a color model based on human vision, to create a precise and defined colour palette consisting of three key colours.

The first step involved analysing the scan data, particularly focusing on the highest metallic values present in the sample. These values were then converted into CMYK percentages. For instance, the following values were identified:

O = 50.1% (Cyan)

Al = 25.8% (Magenta)

C = 13.5% (Yellow)

Fe = 5.6% (Black)

HEX - 7ea3c1

Pantone - 7458C

RAL - 240 70 25

By translating the aluminium sample data into these percentages, the colour profile of the material was established. This step was repeated across all scanned data, taking into account not only the primary metallic content but also the subtle nuances of tone, saturation, and reflection inherent in the aluminium surface. These nuanced variations were key in achieving an accurate and harmonious colour match.

Next, the closest average colour match was identified by referencing various colour database. The derived colour palette was cross-checked for accuracy to ensure it aligned with the intended visual representation. After validation, the appropriate colour was selected, and the corresponding colour code was documented.

This comprehensive process ensured that the final colour, derived from the Aluminium Scan data, was both visually accurate and consistent. It also guaranteed that the colour could be reliably reproduced in various design and manufacturing processes requiring precise colour matching.

Leigh Bagley, Subject Leader Knit Textile Design

In my End is my Beginning (brooch), 2025 Recycled & sintered aluminium, silver and steel 83mm Diameter x 8 mm

The origins of the great church of Linlithgow date back to the Royal charter of King David I in 1138. Over 400 years later, Mary, Queen of Scots, was born in Linlithgow Palace on December 8th 1542 and baptised in St Michael’s Church. Mary was a political prisoner of her cousin Elizabeth I for over eighteen and a half years, before her final execution in 1587. During her imprisonment, Mary crafted a number of embroideries; the rectangular hangings were often surrounded by smaller geometric badges or patch-like “decorated with letters or symbols” (V&A archives).

One lost embroidery, recorded as on a ‘Cloth of State’, was stitched with the words “En ma Fin gût mon Commencement” –“In my End is my Beginning”. These words capture a theme that ran throughout her life with the eternal cycle of life and death.

The badge reflects these themes and narratives in its layered construction. The brooch features a central panel of the original 1960’s anodised aluminium cladding of the Crown of Thorns (1964 Clarke) removed during the renovation. Themes of eternity are reinforced by the cutting of spiral motif in the brooches central panel and the traces of Mary’s words on the reverse silver disc. The historic aluminium is juxtaposed when mounted on a frame of modern 21st Century sintered aluminium.

Professor Stephen Bottomley MPhil RCA, MA, BA Hons Head of the School of Design at the Glasgow School of Art Lead for the Drawing Threads Research Cluster

Left: Untitled Braid 1, 2025

Recycled aluminium, textile and mixed media threads

370 x 2 x 170mm

Right: Untitled Braid 2, 2025

Recycled aluminium, textile and mixed media threads

170 x 2 x 130mm

Elaine Bremner and Susan Telford’s collaboration of woven and embroidered textiles offers a fusion of craftsmanship, where traditional techniques meet experimental material approaches. This union draws inspiration from the architecture of St Michael's Church, Linlithgow, resulting in a dynamic exploration of form and texture through the tactile intricacies of embellishment and the structural elegance of weave.

Taking inspiration from the corrosion of the spire's metal, carved marks and details within the stonework and patterns and textures embedded within the church walls left by centuries of weathering, to the textile materials and surfaces that inhabit the interior and have provided comfort and warmth within the church; we seek to capture and translate the tactile and visual layers found in this historical structure.

By utilising the waste aluminium from the spire of the church as a primary material, the project embodies a sustainable ethos, repurposing discarded elements to create new, purposeful material and technical responses. The aluminium serves as a decorative and integrated feature, while the delicate interplay of woven threads transforms it into something visually rich and texturally complex. This process highlights the potential of upcycling and repurposing architectural byproducts in the realm of textile design.

The explorations emerging from this collaboration reflect the intricate beauty found in the architectural structures of the church. The shapes mirror the sharp lines and dynamic geometry of the spire, and the textures within the walls and interiors have informed the design of these experimental textiles, which explore a layering of techniques and materials. The outcome is a harmonious blend of materiality, technique, and inspiration, bridging the realms of textiles, architecture, and sustainability and resulting in a collaborative collection of decorative braid concepts.

Elaine Bremner, Subject Leader Weave Susan Telford, Subject Leader Embroidery Textile Design

Time (brooch), 2025

Recycled aluminium, silver and stainless steel

80 x 80 x 10mm

Using the discarded aluminium from the original Crown of Thorns by Geoffrey Clarke, I was interested in trying to create a piece that visualised the passage of time.

When the aluminium structure was first erected in 1964, it was not popular and many considered it out of place or inappropriate. Over the next 60 years, the spire has become an iconic emblem for the town, much loved and even featured on school uniforms.

The aluminium cladding on the original spire was anodised gold. This however weathered over the years to a pale grey. The pieces retrieved from the spire still have the original gold colour on the inside surfaces that were protected from the elements, creating an interesting bimetallic sheet.

I used the properties of the hard anodised gold surface, rolling it through metal rolling mills, fracturing the anodised coating to make each piece progressively paler in colour. Using 60 folds to represent the passing of 60 years, moving progressively from rich gold to pale silvery grey. This echoes the timeline illustrated on the street leading up to the church. The folded repeated forms took inspiration from the interior columns of the church as well as the pipes from the church organ, following the rhythmic patterns of these interior surfaces and details.

Anna Gordon, Programme Leader Silversmithing & Jewellery Design

The Crown of Thorns is a familiar sight I have often glimpsed through rain-splattered train windows while commuting between Glasgow and Edinburgh. This project has transformed it from a passing landmark into a source of inspiration for an interrogative exploration of materials. Visiting St Michael’s for the first time and researching its history have sparked new methodologies of material transformation within my work.

Working with mixed metal processes is central to my jewellery practice, and for this exhibition, I became particularly interested in the relationship between the spire’s materials—its original redundant aluminium cladding and the newly introduced bronze alloy. I was drawn to their metallurgical properties and the contrast between the cool, industrial grey of aluminium and the warm, golden tones of bronze. Using processes such as lost wax casting, wire drawing, and sheet fabrication, I have experimented with embedding one material within another, layering them, and allowing elements to emerge through careful surface removal.

The artworks I have created for this exhibition include jewellery and a selection of experimental works, shaped in part by archival imagery—particularly postcards that document the church’s presence over time. Often inscribed with personal messages, these postcards serve as tangible records of place and memory. Their small, tactile nature has influenced my approach, mirroring the way objects can hold both historical and emotional significance.

Learning more about Geoffrey Clarke’s radical, experimental design has encouraged me to embrace process-driven making, allowing materials to guide and techniques to shape both surface and form.

Andrew Lamb, Lecturer Silversmithing & Jewellery Design

Re-inSpired Display, 2025

Screen print (edition of 4) with metallic gold paint on Fabriano paper 460 x 605 x 30mm (framed size)

When we initially visited St Michael's, I was particularly taken by the church's interior which is full of a diverse array of handcarved lettering and fonts. This led to the idea of creating a commemorative display font for Geoffrey Clarke's iconic spire.

With permission from Pollock Hammond Architects, I studied the architectural plans of the spire to inform the shapes of the letterforms. I developed the Re-inSpired Display font, incorporating its spiky, narrowing lines into letter stems. The font's unconventional design mirrors Clarke's approach, aiming to honour the landmark's unique identity.

The most notable elements breaking convention are the A, D, P & Q letters which cross above the ascender line. This mirrors the spikes which travel high above the rest of St Michael's church. Most stems in the font taper upwards which again mimic the tapering of the spire. The font is only available in upper case as the majestic feel of the spire did not translate well in a lower case version. Intended only for headlines in short lines, this font is strong and impactful just like the spire.

I have created a limited edition screen print series to demonstrate the display font in use. For these, I used a metallic gold paint which is fast drying on the screen. This produced a similar effect to the oxidised cladding on the spire—a moment of fated serendipity.

Kim McNeil, Graphic Designer & Technical Manager Technical Support Department

Decladation Neckpiece, 2025

Recycled aluminium, silver, gold 35mm diameter x 765mm

My creative process is considering and responding to the impact of destruction, removal, stripping back and exposing the inner physical degeneration of material and structure, and how we can respond to this through reinvention and creating a new material future.

This piece seeks to celebrate the potential and opportunity for a new future offered by the act of destruction – a scenario current in my life with the destruction of my own home, a converted church, by fire and the process of re-imagining, re-considering and re-instating it.

In decommissioning the material the forced removal by ripping the cladding from the tower has torn through its skin where it was nailed onto the timber structure, creating a ruptured scare revealing the original golden colour on the reverse of the material installed in 1964, the same year I was born.

Incorporating two 35mm discs cut from the redundant cladding material, each centred on a torn section of material where the fixing nail once was, sitting back-to-back creating a medallion like pendant. The handmade chain of twenty-four links is crafted in the colours of the cladding, silver and gold. The three 18ct gold links reference the ecclesiastical context of the holy trinity, and the circular shape of the pendant was informed by the round consecration marks carved into the interior walls of the cathedral indicating where holy water hit the walls.

Another piece in development includes a long neckpiece with 24 discs joined with silver links intended to be worn over ceremonial ecclesiastic vestments. Each disc references an hour of a day, communicating time and reminding us of our limited earthly existence.

Michael SB Pell, Lecturer Silversmithing & Jewellery Design

The Cloth-holder No.1, 2025

TECU® gold copper alloy, deadstock silk, cashmere, polyester filament 220 x 300 x 250 mm & 70 x 300x 250mm

By integrating three types of materials — metal, fibre and wax — our work explores how materials converse and communicate their symbolic meaning through their material characteristics.

We merge the concepts of a candleholder and a textile cloth — two objects integral to universal ritualistic practices—and re-invent their symbolic significance.

The candleholder is crafted from TECU® Gold copper alloy salvaged from the Crown of Thorns sculpture on the spire of St. Michael's Parish Church in Linlithgow. It has been transformed into a round concave form designed to hold and support.

It is a structure hidden under the woven cloth, whose symmetrical pattern mimics the structural (as opposed to decorative) characteristics of the Gothic church's ceiling.

The candle holder has a singular purpose that is purely functional yet is embedded to support and serve as a resting place for the wax candle.

While our project was to join the materials and methods by which we approach craft-making into one object, we have (perhaps subconsciously) engaged in mimicry of the church's structure itself. As the wax candle towers above the candle holder, its position in relation to the cloth resembles the supportive structure inside the church architecture.

Overall, the work represents the intersection of static space and the continuity of time. It asks a question: Is a heritage landmark bound to retain its original status and function over time, or can it undergo an evolution that redefines its identity?

Yitong Zhang, PhD Researcher

Anita Sarkezi, Textile Designer & Artist in Residence

The

Glasgow School of Art

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, West Tower, St. Michael’s, Linlithgow, Scotland, c. 1880-91, pencil on paper, 174 x 126 mm National Library of Ireland

In researching the history of St Michael’s Church ahead of the Re-inSpired exhibition, 2025, much of our focus was directed upon the unique nature of Geoffrey Clarke’s Crown of Thorns (1964) and his wider body of work. Clarke’s crown has become a defining feature of St Michael’s, but is by no means the sole source of inspiration for the eleven artists at The Glasgow School of Art as their works in this exhibition illustrate. Many were also influenced by the church’s centuries-old history and Gothic architecture.

The original stone imperial crown of St Michael’s was one of the three ancient crown spires of Scotland, alongside most famously St Giles, Edinburgh (1495). The removal of the Linlithgow crown was contentious, although by Summer 1821, it was deemed essential to preserve the structural integrity of the church tower. Records indicate, this removal was never intended to be permanent however, with hopes of later reconstruction or redesign.

In 1894, St Michael’s went through extensive renovations to restore the church to its original late Medieval form. After a community-led campaign, the parish was able to raise £7,300 (approx. £800,000 today) to finance the renovations. The Glaswegian architectural firm, Honeyman & Keppie, oversaw the work in which Reformation-era modifications to the church’s interior were removed and contemporary, liturgical artworks commissioned. It is presumed, that it is also during this time, that Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) was introduced to St. Michael’s, and his studies of the church were produced. His drawing of the church’s tower ca. 1880-91, depicts a crenelated stone parapet topped by taller pillared forms. Could Mackintosh’s sketch possibly have inspired Clarke’s design over a century-and-a-half later?

Re-inSpired reflects upon the intersections of art and architecture, and the interactions that occur within this space, and how artists often revisit earlier designs and materials to create something new. The GSA artworks featured in the exhibition respond to these layered histories, drawing inspiration from the church’s Gothic architecture, its periods of transformation, and its enduring role as a site of contemplation and artistic inspiration.

Thomas Coxon

Graduate Student, Collecting & Provenance in an International Context University of Glasgow

Before researching news items about the commission and 1964 construction of St. Michael’s Crown of Thorns by Geoffrey Clarke (1924-2014), I expected to find disparaging articles due to how often it is said that the crown was ‘controversial’ at the time. While I don’t doubt the crown had its detractors, contemporary reporting was largely positive and welcoming. One ardent supporter was Rev Dr. David Steel who served as

minister at St. Michael’s Church from 1957 until his retirement in 1976. In an early article appearing in The Scotsman on April 21, 1962, he wrote of the ongoing discussion concerning the crown to be a contentious one, but ultimately makes his opinion known that the restoration efforts should embrace the “spirit of the medieval age, to mix our periods and make a contemporary crown”. He is reported again in The Scotsman on January 30, 1964, saying the design “symbolises triumph rising like a spear from the Crown of Thorns.”

“Magnificent” declares another contributor under the “Palace Broadcastings” column of the West Lothian Courier on October 2, 1964, the crown has “given St. Michael’s a new lease of life.” Dr. David Steel appears again one week later under the same column to assure readers that the main critics were not locals but from out with the town.

An early model of Clarke’s design shows a more crown-like appearance as well as the inclusion of a cross atop the “spear.” A sketch of this version appears in the West Lothian Courier on November 16, 1962, along with the pronouncement that “a new Linlithgow is about to take shape.” This is not the design that exists today, and the model changed over time – losing features that made it recognisably Christian. One columnist wrote in 1962 that the crown symbolises “a sign of the Church’s willingness to participate”. The progressive nature of an abstract work atop a historic church was perhaps seen as appropriate for this “new Linlithgow.” This is a throughline when it comes to support for the modern crown, a BBC article from May 15, 2024, refers to the spire as “masterful marriage of modern design to historic architecture.”

More positive reporting following construction in 1964 spoke of how the new crown would define Linlithgow’s skyline and differentiate Linlithgow Palace from other palaces in the region. The crown makes it clearly distinct to visitors who might have no knowledge of the intricacies of medieval Scottish architecture. St. Michael’s crown has become a symbol of Linlithgow, a point of pride for its residents. The current outpouring of support online through words and donations speaks to how beloved the crown has become (and perhaps always was). Though sixty-one years old, Clarke’s crown remains symbolic of renewal and eternity as evidenced by the GSA artists’ statements and artworks in the Re-inSpired exhibition.

Decca Fulton Graduate Student, Collecting & Provenance in an International Context University of Glasgow

Re-inSpired Exhibitions

Munich International Jewellery week

Mineralogy Museum Munich

Germany 13th – 16th March 2025

St Michael’s Parish Church

Linlithgow, Scotland

29th March – 13th April 2025

Pangolin London

Kings Place

9th September – 1st November 2025

The exhibition would not have been possible without the original metal donation and ongoing support of Kirstin Davies, Brian Lightbody and St Michael's Church. Our thanks to Dr Melanie Kaliwoda and the SNSB for electron scanning the 1960s aluminium sheet metal and their sponsorship of the Munich exhibition.

A special thanks to Polly Bielecka, Gallery Director, and Rose Gleadell, Assistant Gallery Manager, at Pangolin London Sculpture Gallery, for their support in hosting Re-inSpired exhibition together with their exhibition Geoffrey Clarke. Extension. Thank you also to John Thorne and GSA Sustainability for their support in printing this catalogue.

pp. 10, 11, 12, & 34: Photographs by Geoffrey Clarke. Courtesy of Judith LeGrove and Pangolin Gallery, London.

p.11 Lyonel Feininger, Kathedrale (Cathedral), 1919, woodcut and cover illustration for the Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar, April 1919, courtesy of Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

p. 32 Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Catalogue design: Kim McNeil gsadesignresearch.com

p. 9: Peter Black, Geoffrey Clarke, Symbols of Man: Sculpture and Graphic Work, 1949-94 (Ipswich Borough Council Museums and Galleries and Lund Humphries, 1995), pp. 54-55; Judith LeGrove, Geoffrey Clarke Sculptor. Catalogue Raisonné (Pangolin and Lund Humphries, 2017), pp. 80-81, 92, 281, and Geoffrey Clarke: A Sculptor’s Materials (Sansom, 2017), p. 154. See “St. Michael’s Church Now Restored. Service of Dedication”, Linlithgowshire Journal & Gazette, 9 October, 1964. I extend my thanks to Peter Black, Judith LeGrove, Polly Bielecka, Pangolin, London, as well as Brian Lightbody for their research assistance for the three University of Glasgow essays. pp. 10 & 11 For Gropius’ complete Bauhaus manifesto and program, see https://open-archive.bauhaus.de/eMP/eMuseumPlus; Hans Wingler, Bauhaus (MIT Press, 7th edition, 1986, pp. 31-35); and Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, Ise Gropius, eds., Bauhaus, 1919-1928 (MoMA, New York, 1938, pp. 18-19). Regarding the reception of the Bauhaus in postwar Britain, see Alan Powers, “Britian and the Bauhaus” (Apollo, May 2006, pp. 48-54). p. 19: St Michael’s Parish Church "The History of St. Michael’s Parish Church." About US, 2025 https://www.stmichaelsparish.org.uk/about/thehistory-of-st.-michaels-parish-church. V&A "The prison embroideries of Mary, Queen of Scots." Collections, 2025. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/prisonembroideries-mary-queen-of-scots/

p. 32: Fergusson, John. 1905. Ecclesia antiqua; or, The history of an ancient church (St. Michael's Linlithgow): with an account of its chapels, chantries and endowments. (Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh, 1905), pp. 119, 121-129. M095 Restoration of St Michael's Church, Linlithgow. n.d. Mackintosh Architecture. University of Glasgow. Accessed Online. For an interesting glimpse into Clarke’s artistic and collaborative practice see: “Cast in a New Mould”. Shell Historical Film Archive. 10 minutes. Accessed Online p. 34: “Preserving Medieval Glories of a Church.” The Scotsman. 21 April 1962.

“New Crown for St Michael’s: Church chooses a modern design.” The Scotsman. 30 January 1964.

“Palace Broadcastings.” West Lothian Courier. 2 October 1964.

“A Crown For St Michael’s: New Line For Landmark.” West Lothian Courier. 16 November 1962.

“Golden restoration for crown of thorns church spire.” BBC. 15 May 2024. Accessed Online

overleaf: photo © Katielee Arrowsmith SWNS