Volume 12 Issue 1

December 2025

Volume 12 Issue 1

December 2025

Winners of the DU Law Society x Eagle Essay Competition on the Law’s Role in the Regulation of Free Speech

Law and Truth: The Limitations of the International Criminal Court

The Defamation (Amendment) Bill 2024: Removing Juries and Its Implications

‘Republic of Tolerance’: Freedom of Expression and Civic Engagement in Modern Ireland

Lawrence Valentine Ó Muirithe

Drawing the Line: The Architecture of Free Speech

Paddy O’Halloran

Does Freedom of Speech Extend to the Freedom to Incite Violence? The Legacy of Charlie Kirk and the Future of the First Amendment in the United States of America

Winta Solomon

On Speech, Silence, and the Edges of Law

Halle

The Silver Jubilee of the Children Act 2001 and the Age of Criminal Responsibility – Time for Further Reform?

Child Maintenance Payments in Ireland: Challenges, Shortcomings, and the Case for Reform

Sophie Eastwood

“Fifty Years of the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions,” An Interview with Ms Catherine Pierce

John Lonergan, TCLR Editor-in-Chief A Conversation with History: Interviewing U.S Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson

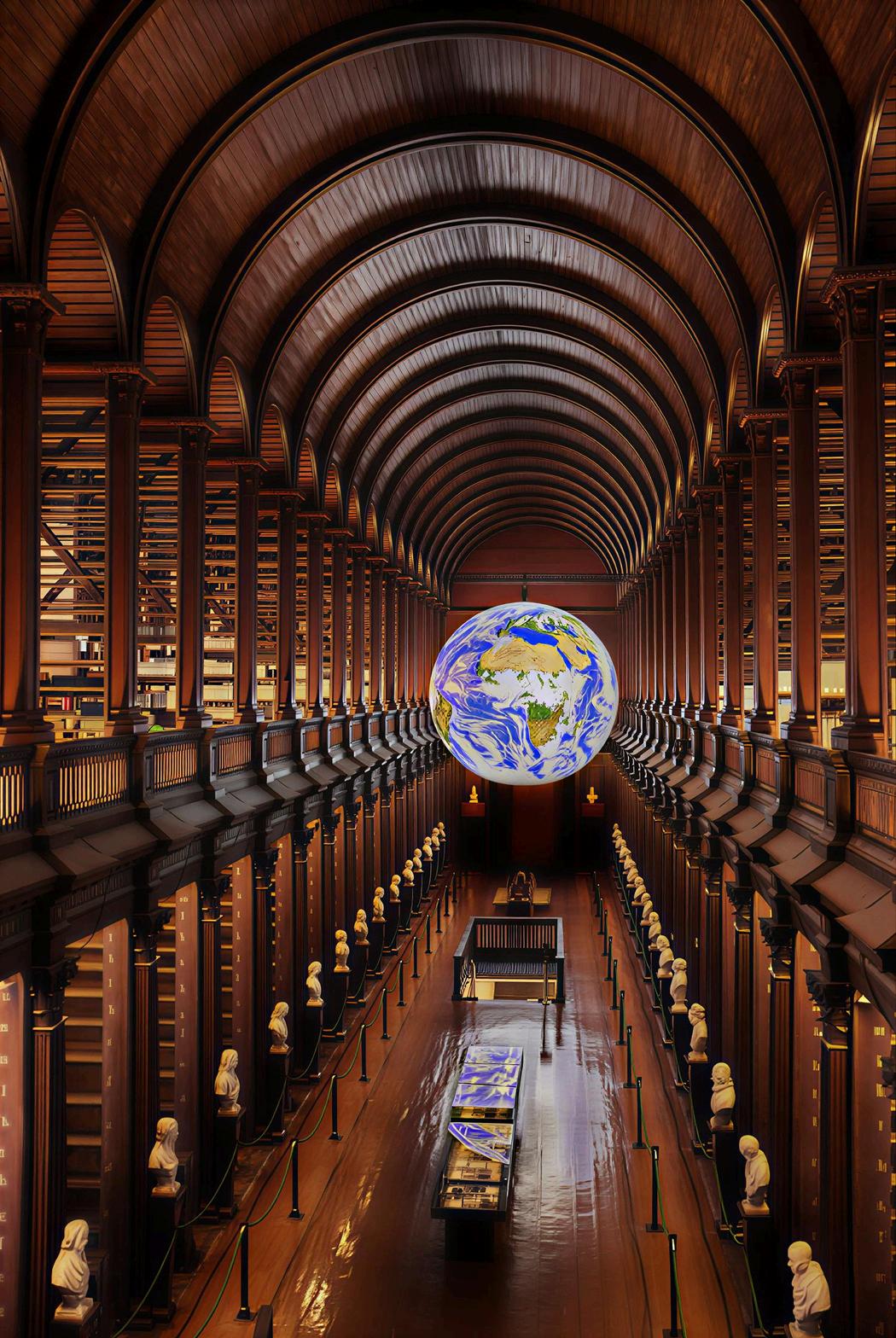

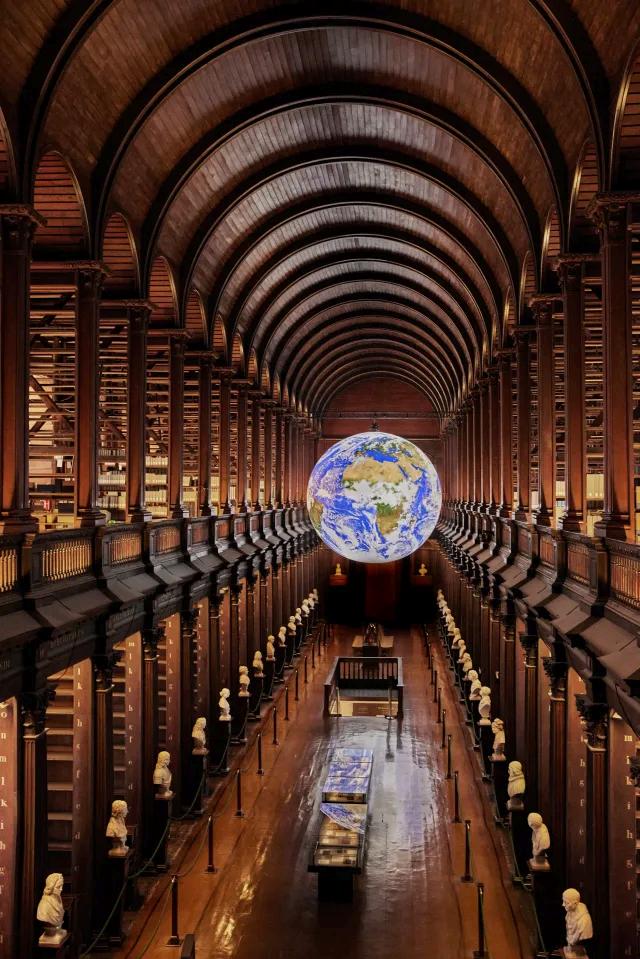

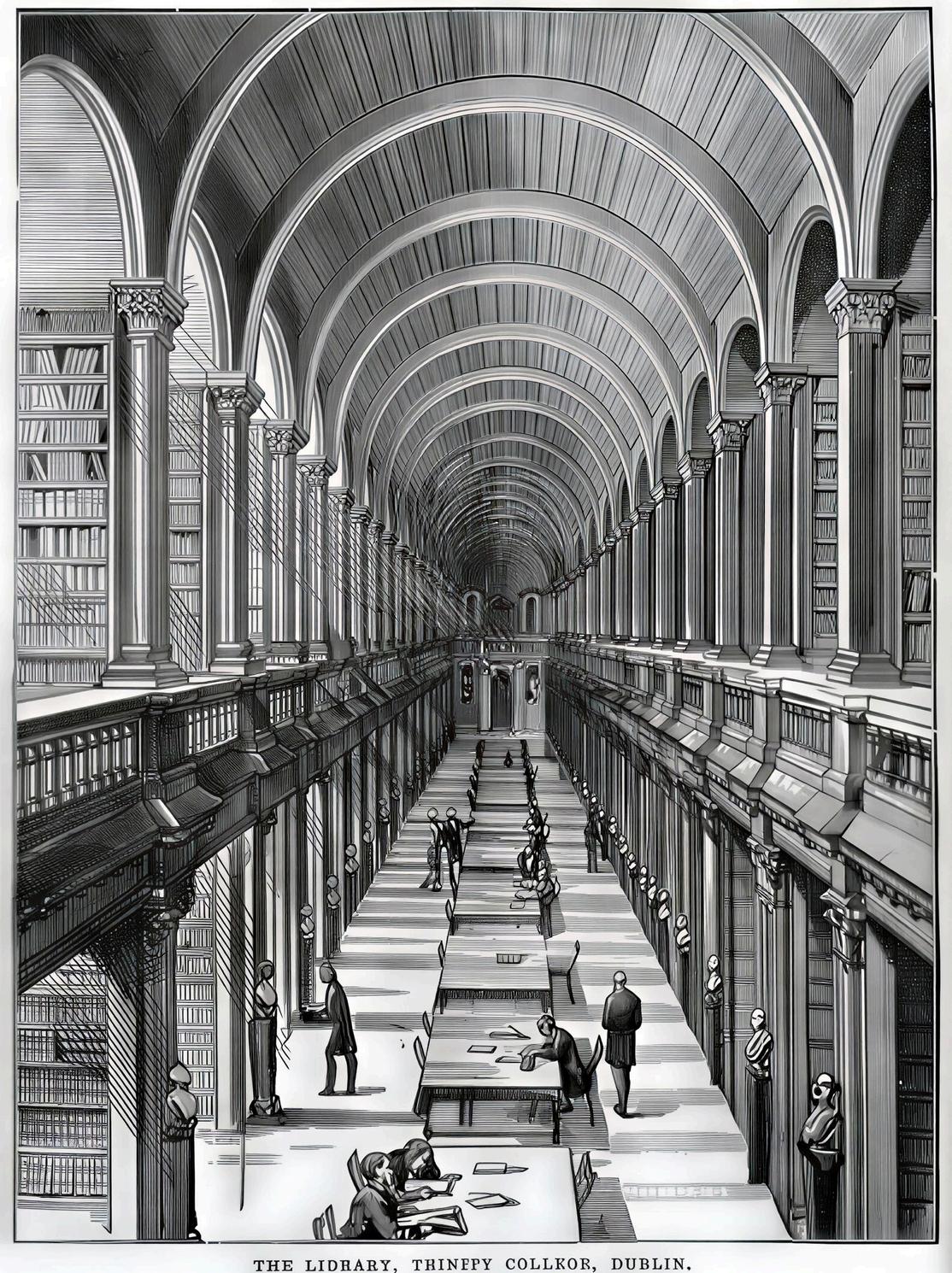

Welcome to The Eagle Gazette’s first issue of Volume 12, and our final publication of 2025.

Since its founding, The Eagle has been guided by a simple mission: to make legal and political writing accessible, engaging, and student-driven. Our aim is to provide a platform where students can examine contemporary issues with clarity and originality, while developing the skills of research, argument, and editorial craft As each year passes, we remain proud of the Gazette’s place within Trinity’s academic and social life as both a forum for ideas and a record of the concerns that shape each generation of students.

This issue brings together work from across the college community and beyond Once again, we partnered with DU Law Society for our annual essay competition, inviting students to respond to the prompt: “A divided age demands a rethink of the law’s role in regulating free speech.” The competition produced a remarkable range of submissions, reflecting deep engagement with questions of democracy, digital regulation, public discourse, and the boundaries of lawful expression.

We are delighted to publish the winning article by Lawrence Valentine Ó Muirithe, the runner-up piece by Paddy O’Halloran, and additional competition submissions by Halle Feest and Winta Solomon Together, these works offer distinct perspectives on the evolving architecture of free speech, drawing on constitutional law, political theory, and comparative analysis

Beyond the competition, this issue includes a wide selection of general articles written by students exploring topics across criminal justice, international law, family law, taxation, defamation reform, and more. I want to thank Amelia Campbell-Foley, Canice Ryan, Ruairi Holohan, Sophie Eastwood, Danielle Power, and Chloé Asconi-Feldman for their thoughtful and engaging contributions Each article brings a different area of law into focus, and collectively they demonstrate the breadth of curiosity and expertise within our student body.

We are also delighted to continue our tradition of collaboration with other student publications This issue features reflections from Trinity College Law Review (TCLR), DU Law Society, and FLAC, allowing us to highlight exceptional work produced elsewhere in Trinity’s legal community.

As ever, an issue of The Eagle is a collaborative endeavour. I extend my sincere thanks to our sponsor, Maples Group, for their continued support. I am deeply grateful to our Deputy Editor Jessica Jiang, Copy Editor Nóra Collins, and Public Relations Officer Danielle Power for their hard work, organisation, and creativity My thanks also go to our Junior Editorial Board, whose dedication and attention to detail make every issue possible

Thank you to all our writers, editors, supporters, and readers for contributing to another year of insightful, student-led analysis We hope that this issue encourages reflection, debate, and curiosity as we look ahead to 2026

David O’Sullivan Editor-in-Chief

Senior Editorial Board

Editor in Chief: David O’Sullivan

Deputy Editor: Jessica Jiang

Copy Editor: Nóra Collins

Public Relations Officer: Danielle Power

Junior Editorial Board

• Gareth McCrystal

• Isobel McSorley

• John Lonergan

• Danielle Briody

• Winta Solomon

• Ayda Ozbay

• Orla Bates

• Leah Bernasconi

• Keelin Walshe

• Joshua Griffin

• Ruairí Bates

• Ruairi Holohan

• Sophie Eastwood

• Angele Rogez

• James De Barra

• Cian Goulding

• Raina Bosniac

• Odhrán Lagan

• Henry McNamee

• Síofra O’Donoghue

• Ainsley Hamilton

• Clodagh McGlynn

The Eagle: Trinity Law Gazette

The Eagle: Trinity College Law Gazette

https://eaglegazette wordpress com

The Eagle is a student gazette which aims to engage the student body at Trinity College Dublin in current legalpolitical issues We give students a forum to publish journalistic style articles on contemporary themes, without the formalities attached to other publications.

“A divided age demands a rethink of the law’s role in regulating free speech.”

by Lawrence Valentine Ó Muirithe

For almost a decade, we have seen a slow decline in the quality of our public discourse. Debate, both in person and online, has devolved into an exercise in mockery and derision. The consequences have become starkly apparent in recent times, especially in what has long been regarded as the international stronghold of free speech, the United States. Globally, we have seen a wide range of debate, political and otherwise, suppressed through official and unofficial means

This global trend has slowly bled into Ireland Irish history is pockmarked with legislation that adopted a generally censorious approach to views that were deemed to be contrary to ‘public morality’ or ‘public opinion’. Recent years have seen an upsurge in political (though not necessarily public) support for such laws. Supporters often point to the divisiveness of the age as justification for suppressing dissenting voices. This approach leaves it to legislators to determine what constitutes acceptable speech.

Such an approach to the laws around freedom of expression lacks foresight It will guarantee a large segment of the population is slowly excluded from public debate, ensuring their marginalisation and ensuring frustration with the political process To avoid this, a different approach is needed, one built on republican virtues of civic participation and public debate. This piece will be divided into two parts. Firstly, it will lay out the history and current position of free speech in Ireland. Once this is done, it will then explore the history and value of republicanism, alongside the new legal approach, which seeks to create a politically engaged base of citizens.

The Free State Constitution of 1922 established freedom of expression as a fundamental right under Article 9, being explicitly subject only to ‘public morality’. This stands somewhat at odds with the 1937 Constitution. Freedom of expression is again guaranteed as a fundamental right under Article 40.6.1°(i). However, the 1937 Constitution subjects it to both public order and morality, in addition to seditious and indecent material The unamended right also banned blasphemy, though this was removed through the 37th amendment

Space precludes an in depth analysis of Art. 40.6.1° (i). Needless to say, it is quite restrictive.The initial approach by the courts to the constitutional right to freedom of expression is notable for the nearcomplete lack of consideration they afforded to it This approach failed to create a golden age of free speech, with the Oireachtas taking the chance to implement substantial restrictions on freedom of expression. Legislation such as the Censorship of Films Act 1923 (as amended), Censorship of Publications Acts 1929, 1946, and 1967 were all used to prohibit material the government found objectionable These various provisions ,amongst others, enabled widespread censorship, with over 12,000 publications banned between 1930 and 2016. This was excessive, even by the standards of the early 20th century, and many opponents of such provisions realised the negative picture of Ireland it presented to the global community.

Having been shot with the starting pistol, the right to free speech in Ireland started the race with a hobble It suffered its way through decades of judicial neglect before eventually receiving some consideration in the 1980s and 1990s. The jurisprudence of this period is confused and disorganised, with the result being another extended period of judicial neglect in favour of Article 10 of the ECHR, though it has recently received some attention. This leads us to today, with many legislative provisions still in existence that exploit the weak constitutional formulation of the right to free speech.

We appear to be at an impasse To stay the course is to invite disaster, as an ever larger segment of the public is slowly pushed out of public discourse

Substantially amending the right brings no guarantee of improvement, as the government of the day could take the opportunity to further circumscribe free speech. We must examine, then, what solution is available to us within the confines that the Constitution currently sets, rooted in republican virtues.

Republican Virtues in an Authoritarian Age Republicanism can claim a long and storied history. Tracing its roots back to the ancient Greek city-states and Roman Republic, republicanism was grounded on the concepts of civic virtue, popular sovereignty and political participation These values were put into practice in many countries over the centuries until they eventually came into contact with Enlightenment ideas This ultimately led to the form of republicanism that would make its way into Ireland, where it would proliferate among the people of the country.The proliferation of these ideas was handed down over a century until eventually crystallising in the republican nationalism of the Irish revolutionaries of the 1910s and 1920s.

The overview of republicanism’s history shows that it is an idea woven into Ireland’s political tradition

These ideas formed the ideological basis for much of the structure of the 1922 and 1937 Constitutions

While other influences and ideologies have played a role in shaping the Constitution, resulting in issues regarding the general republican classification of the document, the republican influence is undeniable. The power of the state deriving from the people, the separation of powers, and the people’s ability to amend the constitution through referendum are all indicative of a republican ethos.

However, the Constitution’s republican credentials fall short in the fundamental rights section under Articles 40-44, including the right to freedom of expression As shown in the previous section, the right has been historically circumscribed and remains restrictive in the modern Irish state. This is at odds with many of the ideas central to the character of republicanism, namely, freedom from arbitrary rule and domination. The broad and unclear nature of many of the legislative restrictions makes it difficult to determine what is and is not considered legally legitimate speech. As a result, the active civic participation that is expected in a republican society is hindered as citizens fail to articulate their views in the public forum due to fears of prosecution. Such a situation undermines a political system which requires an active citizenry to ensure adequate oversight of the state and its use of power The state’s failure to create this citizenry is an indictment of the current approach.

The situation is, as previously stated, untenable A state that claims adherence to republican principles cannot sustain itself through the continued suppression of speech it disagrees with Action is needed, and the solution will require the government to take two steps on what will be a long road towards creating a society of Citizens rather than one of voters.

Firstly, the government must repeal much of the legislation that currently restricts free speech, helping to encourage people to get involved in political debate. However, this is insufficient and could also lead to much talk about nothing due to the lack of structures in place to direct the emerging debate As such, the government should curate spaces in which citizens can engage in proper civic debate This already exists in the form of citizens’ assemblies and public consultations but they are insufficient, as they fail to draw in the public at large and involve only a tiny fraction of the electorate.

The creation of a new model citizen will require a lifelong education and commitment to civic participation, as well as the devolution of powers to the local level. This will enable the creation of local deliberative forums, which will be authorised to discuss and resolve the issues relevant to them

This will empower citizens to participate in the political process, as well as equip them to better articulate their political beliefs in a setting that does not put them at the mercy of the national stage. Such forums will serve the dual purpose of solving problems at the local level and acting as ‘training grounds’ for citizens to develop their beliefs and oratory in an environment that encourages freedom of expression.

This article has sought to explain the current issues surrounding freedom of expression in Ireland and propose a solution to them Although the scope of this piece is limited, it is hoped that this piece serves, if nothing else, as a small part in the move towards a citizenry that exemplifies the idea of civic engagement. Freedom of expression is the single most necessary brick in the foundation of this idea (second only to the right to vote itself). Engaging in debate is essential to the development of one's political beliefs Conversely, suppressing tough debate leads to an unengaged mass of voters who return to polling stations every five years to vote for the son of the man their father voted for ad nauseam. What is needed is a citizen who engages in the debate surrounding the ideas of the day, rather than being swept up in the partisan nature of the politics around them. Such a base of citizens will become ever more necessary in an increasingly divided world.

by Paddy O’Halloran

“The important point for liberalism is not so much where the line is drawn, as that it be drawn, and that it must under no circumstances be ignored or forgotten”.

~ Judith Shklar.

To say we live in a ‘divided age’ is to say something about a moment in which questions are met with answers that represent not where we stand, but where the polarisation has thrown us The discourse on free speech exemplifies this polarisation in its attempt to answer the question – should we be allowed to say ‘X’? And, like most questions concerning whether or not ‘we’ are ‘allowed’ to do something, law almost automatically enters the discussion, and accordingly we instead ask – should law restrict us from saying ‘X’? In our so-called ‘divided age’, it appears that the available answers to this question congeal around two ideological poles – absolutism and governance, where governance prescribes what counts as free speech, and absolutism does not. In this paper, I want to critique these ideological poles to argue that free speech lives, somewhat paradoxically, by virtue of constraint – a line drawn and recalled which, in Judith Shklar’s words, under no circumstances be ignored or forgotten

To begin, what exactly is ‘free speech’? What shape does it take, what weight does it carry? In legal language, free speech takes shape as a first generation civil and political right termed ‘freedom of expression’. We can take this term, and break it down into two concepts – ‘freedom’ and ‘expression’. So then, what do these terms mean? Jacques Derrida’s

theory of Différance is useful to unpack these abstract concepts. In Différance, Derrida highlighted the impossibility of accessing any inherent meaning in language – rather, he argued that the meaning of a word arises by virtue of its difference from other words. I want to stress this notion of definition by contrast. Looking at ‘freedom’ and ‘expression’ through this lens, we can understand that these terms lack any natural content of their own – its intelligible value, as with anything, is contingent upon identifying where it begins and ends My point is that freedom of expression can be understood as a product of its limitations, which are set by law

It follows that any coherent understanding of freedom of expression is consequentialist. Stanley Fish puts this as follows,

The unavailability of any transcendent truths to invoke can be an advantage to someone who has the skill and resources to advance the truth he or she prefers to a place of honour that has"natural " inhabitants.

The relevance for my argument emerges as follows. Once we accept that freedom of expression has no natural content, and that its meaning is defined by its limitations, we can begin to sharpen down the role this right plays as a tool in safeguarding free speech Manifestly, this problematises the position for an absolute untrammelled right to free speech We ask the question – if the meaning of freedom of expression is identified by its limitations, then what are the absolutists campaigning for?

What I am suggesting, then, is that when we advocate for freedom of expression, we are not really

advocating for freedom of expression per se Rather, we understand freedom of expression as valuable for other ends – for example, the dissemination of truth, or participating in civic discourse. The limitations we set on expression emerge from these values – where an act of expression undermines them, we restrict it. In other words, once we recognise that freedom of expression is valuable because it promotes certain ends, we also accept that expression which frustrates those ends may be justifiably curtailed. All of this unsettles absolute accounts of free speech by compelling us to ask what it is that makes expression worth protecting in the first place From there, we begin to determine what kinds of restrictions are consistent with safeguarding those underlying values. For example, take the Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act, which criminalises material intended to stir up hatred. We might justify this limitation on freedom of expression as a way to preserve the conditions of democratic discourse, as hate speech can undermine equal participation. Or, we might disagree, and consider hate speech as an important component of democratic discourse The obvious question emerges – who decides?

From a legal standpoint, the state establishes and enforces the boundaries of permissible speech. Proponents of an absolute conception of free speech might chime in here, to caution that authorising the state to define the contours of ‘legitimate’ expression is fraught with consequences. In respect of civic discourse for example, the stakes are high. Permitting the state to determine what counts as ‘civic discourse’ – what can and cannot be said – effectively maps the boundaries of collective imagination This carries a disquietingly dystopian undertone – it is the uneasy trade-off of using law to uphold free speech. The socalled ‘Palestinian Exception’ is a pertinent example of this concern, where scholars have documented systematic efforts to silence Palestinian perspectives through discriminatory practices. Consider Kneecap, whose political expression concerning Palestine was met with government scrutiny and attempts at restriction in the UK.

We can debate whether this attempted restriction would serve a legitimate aim, but my point here is that this case illustrates the peril of ceding evaluative authority on free speech to the State In defining what

sort of speech is valuable, and what is not, we risk freezing freedom of expression into a static, sanitized shape. As Justice Gerard Hogan put it,

We cannot live in some sort of antiseptic and sterile society where roust comment on public affairs is treated like some kind of hostile germ against which the most elaborate anti-bacterial precautions must be taken.

It is in this way that freedom of expression can operate as a sort of double-edged sword, as the very framework we have designed to protect free speech can be used to sustain its oppression. Rather than serving purely liberatory ends, it can instead function as a mechanism of governance And so, we ask – how do we confront the paradox of free speech as both a tool for liberation and a tool for governance?

To confront this paradox, I want to propose a theoretical framework grounded in the concept of enabling constraints. The concept is relatively simple – certain restrictions, rather than limiting freedom, can paradoxically enable it. Constraints provide structure, and structure can foster creativity, clarity, and meaningful participation. Consider a sonnet, with its strict formal limits – fourteen lines, a precise rhyme scheme – yet these very restrictions push the poet to innovate within the form, and produce work that may never arise in a free-for-all unstructured verse. The constraint is therefore not limitation in the negative sense It is a framework that channels expression in productive and generative ways Applied to freedom of speech, enabling constraints suggest that we can accept targeted limitations on expression so long as they serve to protect and sustain generative civic discourse Consider again the example of hate speech – restrictions on threats, harassment, or speech intended to intimidate others does not merely suppress expression, it can also preserve the capacity of people to participate meaningfully in public debate It is my claim that this understanding is a more narrow and principled

departure from broadly banning any speech deemed hateful, which risks suppressing the very norms and debates that law should enable. In other words, restrictions are justified not because speech is disagreeable, but because it stifles the generative space of civic discourse itself a space where values like truth, autonomy, and democratic engagement can flourish. Interestingly, in the Irish case the courts have begun to somewhat reflect this approach. In Cornec v Morrice for example, Justice Hogan emphasized the constitutional right to freedom of expression as a vehicle for civic participation and the protection of public opinion, rather than a purely abstract entitlement to speak without restraint. This represents a jurisprudential turn from a previous string of case law that was heavily qualified, weak and superficial. This turn exemplifies how enabling constraints can guide law by focusing on whether restrictions enhance or undermine the conditions for generative civic discourse, courts can uphold free speech while preventing its capture as a static, sanitized tool of governance.

Conclusion

The right to freedom of expression is the legal manifestation of our desire to preserve free speech in society Like any legal right however, one person exercising their rights affects the effective exercise of someone else’s right And so, a line must be drawn. Drawing this line poses a particular issue for free speech, because we fear the line will stifle speech, which can only exist in an absolute form What I have tried to suggest here is that the line need not govern Instead, we can understand it as a locus of resistance to preserve speech that promotes generative civic discourse It is this, not unfettered freedom, that is the true bottom line for free speech that we must, under no circumstances, ignore or forget

“A divided age demands a rethink of the law’s role in regulating free speech.”

by Winta Solomon

On September 15th, 2025, US Vice-President JD Vance appeared on the Charlie Kirk Show. The podcast was formerly hosted by Charlie Kirk, a farright activist who was assassinated on September 10th, 2025, at Utah Valley University while conducting his ‘The American Comeback Tour’. In his guest appearance on the show, Vance said, “call them out, and hell, call their employer, but we do believe in civility, and there is no civility in the celebration of political assassination” The statement of the Vice President presented a call to arms to fellow right-wing comrades, asking them to report any person who posted unfavourable references to Kirk’s death, going as far as to suggest that they should be reported to their place of employment.

Charlie Kirk has been made into a martyr, with arguments that no one should be a victim of political violence merely for sharing an opinion. It is, of course, a true and honest sentiment that no person should lose their life to violence. However, is it fair to claim that punishing those who highlight Kirk’s legacy of violence as ‘protecting’ freedom of speech? The death of Charlie Kirk has surfaced two questions relating to the fundamental position of free speech in America: whether calls to action by government officials, like that of JD Vance, should be considered ‘legal’ interference, and what the true meaning of ‘political’ speech is.

State representatives inserting personal opinions into State politics is a dangerous precedent Following the assassination of Kirk, a website called ‘Expose Charlie’s Murderer’ (later renamed as the ‘Charlie Kirk Data Foundation’, and later taken down on September 16th, 2025) was created. This platform is

designed to expose anyone posting unfavourably about the death on social media essentially serving as a doxxing mechanism. A website like this being endorsed by private citizens is troublesome. Endorsement by the Vice President of the United States of America is cause for deep concern. The law’s rule in regulating free speech extends beyond codified legal rules. Government officials indirectly leading to the punishment of citizens speaking their dissent does extend into the legal realm, and poses a threat to the promise of free speech in the USA Risk extends far past national concern Globally lauded as a pillar of ‘freedom’, the United States has created a risky model that other States will now feel enabled to follow. If a country with as prominent a world presence as the United States can freely dox citizens who share non-violent political opinions, there is little to stop other states from following in these footsteps.

Charlie Kirk was a leader of the American far-right whose conservative, Evangelical Christian views consisted of being anti-abortion, anti-Islam, antifeminism, anti-LGBTQ, and anti-immigrant His organization, Turning Point USA (TPUSA), was created to mobilize American youth towards his cause The Charlie Kirk Show, which brought his opinions to the main stage Both during his career and after his death, Kirk has been referred to primarily as a ‘political activist’. The question therein is whether his opinions truly can be classed as political. Oxford Languages defines the word political as ‘relating to the government or public affairs of a country’. The same dictionary defines hate speech as ‘abusive or threatening speech or writing that expresses prejudice on the basis of ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or similar grounds’ The rise of far-right politics across the world has created a worrisome dilution of

what is considered to be political The ideas that Charlie Kirk championed were not political — they were matters of basic human rights. Kirk rarely spoke about pure political matters, such as the economy, trade deals, or globalization. Instead, he worked towards the deportation of non-violent immigrants, the abolishment of reproductive healthcare, and the promotion of Christian religious extremism.

The foundations for Kirk’s beliefs were his ideas of religion, not anything that was fundamentally related to politics. To then claim that his assassination was an attack on free speech, but the website ‘Expose Charlie’s Murderer’ is not, is a misguided conclusion. The idea that the law should regulate political dissidents but not hate speech and inciters of violence completely reframes the idea of the law’s role in regulating free speech In an age where division is the primary rhetoric, creating a just regulation of free speech first requires a separation of political freedom from hate speech and radicalism. It is the purpose of the law to create a balance between allowing political dissent an integral pillar of democracy and prohibiting incitement to violence and extremist ideals The death of Charlie Kirk has brought forth a crossroads for the future of the idea of free speech in America, and whether violent extremism will continue to be protected under the umbrella of free speech.

“A divided age demands a rethink of the law’s role in regulating

by Halle Feest

A divided age asks us a narrow question in a loud voice. It is not whether speech matters. It always has. The question is what shape law must take when speech no longer moves through settled channels but through scattered platforms, partisan networks, and private halls that pretend to be public. In the last decade, the familiar architecture of free expression has been stressed until its joints creak. People who once shared a city now live in different newsrooms. Words that used to be local now travel worldwide in an instant That acceleration has pushed old legal categories to the brink and invited fresh laws, each carrying its own promise and peril

When law enters the field, it carries a blunt instrument and a conscience. Democracies have responded in two roughly opposite ways: by insisting platforms should police content, or by demanding that states restrain the reach of those platforms. Europe’s Digital Services Act envisions a more substantial public role in shaping how very large platforms manage illegal content and protect fundamental rights It places duties on companies and creates oversight that did not exist before For advocates, this is a move toward accountability and safety. For critics, it is a new axis of control that risks chilling speech across borders The act is now live in practice and has already produced friction between regulators and companies that see the internet as borderless.

Across the North Channel, the United Kingdom took a more direct and contested path through the Online Safety Act. The law imposes duties on platforms to protect users, and it creates offences aimed at some forms of false or harmful communication. Defenders frame the act as an overdue correction to an

architecture that once treated speech harms as an acceptable cost of openness Opponents warn that the new rules could force platforms into precautionary removals or intrusive measures in the name of safety Tech companies, civil liberties groups, and platforms themselves have each voiced alarm about the risk of sweeping censorship or privacy intrusions if enforcement is overzealous. The practical result, as commentators have shown, is a public conversation about where state protection ends and state restriction begins.

The United States offers a contrasting laboratory where the First Amendment is often a brick wall and where courts have been sharpening, not softening, doctrinal contours. The Supreme Court’s recent docket has included high-stakes free speech disputes that test the edges of what the state may do about content on social networks and about laws that purport to regulate ideology in public life. Judges who worry about governmental encroachment on speech often answer by narrowing state power The effect is not always simple protection. Narrowing state regulation can transfer power to private actors, most notably the platform owners who now moderate speech with a discretion that is often invisible to the public The law, in short, can free speech from one set of constraints only to place it under another.

Closer to home, the conversation is more public. Ireland’s attempt to modernise hate and incitement law produced a political bargain that peeled back

some of the more controversial proposals. The Criminal Justice bill that once promised new incitement offences was pared down amid concern about vagueness, enforceability, and the risk of chilling legitimate expression. The government proceeded instead with hate crime measures while pausing on broader speech offences That pause is instructive; it tells us that lawmaking in a divided age is not only technical work It is a political theatre in which lawmakers, activists, and global platforms wrestle over definitions, over evidence, and above all, over who counts as harmed and who counts as speaker.

Universities are a small but revealing stage for the larger drama. Campuses are supposed to be places where contentious ideas meet scrutiny Yet in practice, they have become contested territory. Complaints about deplatforming and cultures that silence dissent are common on both the left and the right. Trinity College itself has seen debates about who should speak, what counts as harassment, and how academic freedom is to be preserved. These episodes show how legal rules cannot be isolated from institutional practice. A law may protect an abstract principle, and yet a university’s culture, complaint mechanisms, and governance determine whether that principle lives or dies in the day-to-day.

So what should the law do when the social ground is riven? There are three modest but necessary moves. First, the law should be clear about harm The venerable harm principle remains useful. John Stuart Mill argued that state power is justified only to prevent harm to others. That simple idea survives because it forces us to care about what counts as harm But in our time, harm can be aggregated, delayed, or structural. Law must adopt a calibrated account that can distinguish between speech that plausibly causes direct, imminent danger and speech that simply offends or troubles A robust definition will help avoid over-broad criminalisation while permitting intervention when the consequences are real

Second, the law must attend to procedure and evidence. When the state or a regulator acts against speech, it should be under transparent standards, with reviewable decisions, and with the burden of proof aligned to the severity of the sanction The DSA and the Online Safety Act point toward governance by agencies and standards that bring procedural safeguards That is a step forward if those frameworks are used to protect rights and not merely to expedite takedowns Independent oversight, public reporting, and remedies for wrongful restriction will keep the balance from tipping into silence Proceduralism is not a panacea, but without it, law becomes blunt and arbitrary.

Third, the law must be modest about what it can achieve alone If polarisation is social and technological, legal remedies must be paired with civic repair. Media literacy, public funding for journalism that fosters cross-partisan norms, and institutional practices inside universities will do much of the heavy lifting that law cannot.16 Laws that penalise only at the highest end of harm must be part of a larger ecosystem that fosters pluralism. Otherwise, legal bans will be like pruning a tree while leaving its roots to fester.

This is not a call for timidity. It is a plea for precision. A divided age tests the capacity of law to be both a shield and a scalpel.

The temptation is to choose one or the other. The defender of liberty hears only the shield and fears every new duty. The advocate for protection sees only the scalpel and presses for total remedies. The wiser course accepts both instruments but insists they be wielded narrowly, transparently, and with respect for due process In practical terms, that looks like laws that define harm with care, procedures that limit error and abuse, and public investments that rebuild the common ground on which speech can again be contested without violence.

When the noise is loudest, the law can do two necessary things It can set the floor below which we must not fall, and it can set the stage upon which contestation happens according to predictable rules The floor protects persons from real danger. The stage invites argument, even rude and imperfect argument, but argument governed by regulations If the law abandons either of these duties, it may fail its most humble promise In a nation of strangers who nevertheless must live together, few things matter more than the ability to speak and to be heard without fear of arbitrary erasure The age is divided. Let the law not be the last instrument that divides it further. Let it be the instrument that remembers why we once learned to speak to each other at all.

By Amelia Campbell-Foley

This paper argues that the Permanent Members’ conflicting views of peace turns veto power into a tool that paralyzes the United Nations Security Council’s legal authority.

Although the definition of “peace” is both evasive and contested, this paper adopts the simplified definition as “the absence of war or armed conflict.”

It is not novel to suggest that the United Nation Security Council (UNSC) is a hotbed of introspective political interests, masquerading as an impartial guardian of global peace. Yet, “peace” itself is rarely examined as the shape-shifting smokescreen it truly is, with member states bending its definition to suit their own agendas.

The concept of peace is intrinsic to the UN Charter and the role of the UNSC. Art. 39 entitles the Council to “determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace [ ]” and to “maintain or restore international peace and security ” Art 1 establishes the UN’s purpose as maintaining peace, while Art 2(3) obliges all members to settle disputes by “peaceful means ” Although the Charter presents peace as a universal and objective standard, in practice, the five Permanent Members (P5) interpret it differently unsurprisingly, given that the “characteristic feature of peace [is] that it cannot be defined.” These conflicting definitions allow them to use the veto to pursue political interests, blocking the Council from enforcing international law and effectively paralyzing its legal authority. Their positions on peace are not legalistic nor contingent on morality, but instead political and shifting in nature By examining how Russia and the United States (US) have different approaches to what constitutes peace, we can see how these members frustrate the UNSC’s legal obligations.

For Russia, peace is a domestic process, achieved internally with limited interventions and minimal international oversight. It sees peace as equivalent to a ceasefire and restored sovereignty, rather than longterm democracy or human rights reforms. Formally, Russia views the termination of hostilities and restored state sovereignty as sufficient for peace This perspective was seen during the Syrian Civil War (2011-2018), when Russia repeatedly vetoed Security Council resolutions deploring the Assad regime While Russia's justification for these vetoes was protecting Syria's sovereignty and opposing intervention, it is clear that the vetoes also served political interests. Syria imported huge amounts of Russian defence equipment and arms, making the Assad regime a valuable ally. These vetoes crystallised into legal consequences, forcing the Council into a standstill and preventing it from fulfilling its obligations under Art. 1 and 39 of the Charter Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also shows this fluctuating nature of peace and non-interventionism, applied selectively when it aligns with political interests

In contrast to Russia’s “statism and nationalism,” the US has repeatedly sought to impose its own fractured democratic system on countries thousands of miles away (e.g. Afghanistan) often viewing external, transformative processes and the promotion of longterm systemic changes as prerequisites to peace.

The US often views itself as the “custodian of international order” as well as the “protector and promoter of human rights, democracy and liberal values ” For example, from the beginning of the Syrian uprising, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton framed peace not just as the restoration of sovereignty, but as removing the oppressive regime and enacting political reform, with the US committing itself to helping Syria prepare for a “democratic transition.” However, Russia is not unique in bending its definition of peace when political interests are at stake. During the Rwandan genocide of 1994, due to the US not wanting to intervene and “repeat the fiasco of US intervention in Somalia” and because there was nothing of capital value to be gained, the US utilised a ‘hidden veto’, threatening to block any resolution labelling the crisis as a genocide This inaction frustrated the Council’s ability to respond to its obligations under international law, including its duties under the 1948 Genocide Convention and the UN Charter duties to maintain international peace, thereforeallowing violations of jus cogen norms, such as prohibition of genocide, to go unchecked. This overhanging threat of a veto from the US forced other members of the UNSC into a state of legal stagnancy, showing how the political interests of the US in that period overrode the UNSC’s legal obligations.

At present, the UNSC veto is grounded in subjective and unstable definitions of “peace ” Reforms are desperately needed to restore the legal integrity of the UNSC and ensure that it is guided by law rather than shifting political interests and fluctuating interpretations of peace Such reforms could include a rotating veto, expanding the P5 to include more member states with the power to veto, limiting the use of the veto in cases involving jus cogens violations or mass atrocities (a principle known as the “Responsibility not to Veto,”), or potentially a complete abolition of the veto power. Such reforms are not simply a mere procedural upgrade, but rather a matter of life and death for the integrity of international law and the protection of humanity.

by Canice Ryan

I have no doubt. Truth will prevail.

These were the words of the former French President, Nicholas Sarkozy, as he began his five year sentence for conspiring to fund his election campaign with funds from the former Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi. This statement captures the tension between truth and law in criminal procedure, a relationship which is particularly visible in international criminal law As projects for peace and justice, the International Criminal Court (ICC, The Court), as well as other International Criminal Tribunals (ICTs), were established to prosecute perpetrators of human rights violations and international crimes Although the prosecutor of the ICC is required by statute to “establish the truth”, the Court is not mandated to do its own investigation into the facts. The Court has an adversarial procedure where prosecution and defence present their case, and each side is responsible for gathering and presenting its own evidence. Rules of evidence and procedure limit the facts produced and the depth of the truth that can be attained. This is compounded by the limited temporal and territorial jurisdiction of the Court, which obstructs a “full picture” understanding of the conflict to emerge at the trial The limited truth finding function of the ICC problematises it as an adequate mechanism for transitional justice and highlights its insufficiency to provide a broad historical context of the conflict.

The UN Secretary-General’s Report on the Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post Conflict Societies, defines transitional justice as “the full range of processes and mechanisms associated with a society’s attempts to come to terms with a legacy of large-scale past abuses, in order to ensure accountability, serve justice and achieve reconciliation”, listing truth-seeking as one such mechanism Truth has been hailed as an important aspect of understanding and reconciliation, as Amartya Sen argues: “violence cannot be maintained

between those who understand and respect each other. It can only be sustained with a breakdown of respect and understanding”. Twenty-three years after the adoption of the Rome Statute in 2002 and the foundation of the ICC, the Court has ended impunity for violations of human rights, which in the fifty years previous had gone unpunished While determining criminal responsibility for crimes, the truth established is incident-specific and falls short of providing a historical narrative of the conflict In the context of the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, where the warrants for the arrest of Vladimir Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu have been issued, recognising the limits of ICTs is vital. Acknowledging these limitations allows other mechanisms such as truth commissions, institutional reform and reparations to fulfil transitional justice requirements.

The ICC and ICTs have rules of evidence and procedure which ensures that only legally permissible facts are presented at trial The evidence admitted must be relevant to the charges in the indictment For example, in the trial of Joseph Nziroera during the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), evidence relating to a meeting between the accused and the Prime Minister in exile was deemed inadmissible as the fact was not contained in the indictment. Pragmatic considerations of the evidence also form part of the admissibility test in ICTs. In Case 001 of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), the judges did not admit certain videos of the Khmer Rouge prison camp as they were deemed to be “cumulative” The Court will limit any evidence which would fail to preserve the fairness of the trial, in particular, evidence which might prejudice a jury. Rule 89(c) of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) allowed courts to exclude evidence if it is “substantially outweighed by the need to ensure a fair trial”. These evidentiary rules, while protecting the rights of the accused, provide essentially a “trial

truth” rather than a “real truth” This distinction has been emphasised by ICT judges reflecting that criminal trials determine legal responsibility and not broader historical understandings of the conflict

The adversarial focus on achieving a guilty or innocent verdict means that only legally relevant evidence will be produced. This, along with the perception that an acquittal is a failure, means that criminal trials are ill-equipped to provide a broader historical narrative of the conflict.

While rules of evidence and procedure limit evidence from being used at trial, limitations of time and territory mean that some evidence is excluded from any examination. The investigation of crimes in ICTs will specify a time period and have jurisdiction over a limited area This was highlighted through the ICTR, in which Rwanda refused to support the tribunal due to the limited temporal jurisdiction of the court. Rwanda argued that since the court focused on dates between 1 January and 31 December 1994, earlier crimes committed between 1990 and 1993 would be left out Similarly, the Special Panels for Serious Crimes in East Timor had jurisdiction over crimes committed between 1 January and 25 October 1999, leaving out mass atrocities committed in the previous twenty-four years. The Court also has a narrow territorial jurisdiction, with only the 125 states parties to the Rome Statute being under the jurisdiction of the Court. This has the potential of excluding evidence which may have historical relevance but is not legally admissible. Along with the limitations of time and territory, many victim’s voices may not be heard as they will not desire to be cross-examined in a criminal trial The exclusion of evidence outside this scope limits a broader understanding of the context in which the human rights violations occurred

Reflecting on the truth finding ability of the ICC and ICTs probes the question of the role of criminal trials in reconciliation. Jacques Derrida brought to our attention that the urgency of a legal decision “obstructs the horizon of knowledge” A legal decision is immediate, and since reconciliation through a narrative truth is the goal, criminal trials are ill-equipped for this task Although criminal accountability may provide justice for victims and their families, it may not provide the broader truth required for reconciliation. Like the sun and the moon, truth and law rarely align perfectly, and unlike an eclipse, it is never clear when they do.

by Ruairi Holohan

As with many landmark statutes, there is often a lot of discourse about their successes, failures, and legacies of landmark statutes. The Children Act 2001 (“the 2001 Act”) is no different. It is one of the cornerstones of the justice system and epitomises juvenile criminal justice in Ireland. However, what was once an influential legal development now represents momentum, and it is time for further reform of the law to reflect modern society.

The 2001 Act delivered long overdue ameliorations to the criminal justice system, with academics declaring it to be the most comprehensive reform of the juvenile justice system in a century. Most notably, the act raised the age of criminal responsibility (“the ACR”), focusing on rehabilitation, and placing the Garda Youth Diversion Programme on statutory footing. The 2001 Act focused on welfare, education, rehabilitation and restorative justice, and provided for anonymity, expunged records, and the Children Court, accordingly

The 2001 Act transformed Ireland’s capacity laws surrounding the age at which a child could be held legally responsible for their actions Section 52 provides that children may be deemed criminally liable for their actions from the age of 12, and from the age of 10 for serious crimes. Historically, common law provided for a rebuttable presumption that children aged 7-14 were doli incapax, lacking the capacity to commit a crime, which was placed on statutory footing in the Children Act 1908. Societal influences restricted the reform of capacity laws, and opinions did not begin to change on the causes of juvenile delinquency until the 1980s

Section 129 of the Criminal Justice Act 2006 (“the 2006 Act”) repealed this historic rebuttable presumption, rendering any capacity-related protections afforded to children aged 13-14 null and void, save for one exception. Section 134 of the 2006 Act provides that where a child under the age of 14 is presented before a court, the Court has the power to dismiss the case if it deems that, in consideration of the child’s age and level of maturity, the child lacks a full understanding of what was involved in the commission of the offence However, it must be noted that while this protection is available, children aged 13-14 have less protection in the Court today than they did 100 years ago. Of course, most young offenders avoid the courts due to the Garda Youth Diversion Programme, but should they be seen before a judge, their capacity is not assessed to the same extent as it once was.

Raising the ACR to 12 acknowledged the need to recognise the offenders as children, remaining cognisant of their level of maturity, their cognitive development, and their welfare. However, it is submitted that the ACR is still too low. Having the lowest ACR in Europe, Ireland has come under pressure from the UN to raise it to 14, in line with international standards. While the Beijing Rules do not explicitly set a minimum ACR, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has criticised Ireland’s low ACR, and has called on the Government to increase the minimum age to 14. Many academics have also recommended this Hanly submits that it is “morally unjust to prosecute someone without knowledge of their wrongdoing.” Mosepele has called for increasing the ACR to 18, and has referred to international standards, and the increased evidence on cognitive development that was not known to society in 2001. The author also referred to Becker’s labelling theory – the idea that deviance is created as a result of labels imposed on people by society. If a child is labelled as a criminal, they are more likely to re-offend, entering into a vicious cycle

It is indeed morally unjust to prosecute children as young as 12 when they are not afforded many other rights in Irish society Under the current system, children face the risk of being imprisoned before they have reached the age of consent for sexual activity and for medical procedures. Furthermore, children can only begin to work from the age of 14. Even then, the level of work that they can endure is heavily restricted. Why is it the case that the law views children as mature enough to be held responsible for their actions when they are deemed incapable of consenting to an elective medical procedure or to leave full time education?

It is submitted that children should be respected as children, and this respect for their age and lack of maturity should be transcribed into the legal system. Due consideration must be given to their age, as prescribed in Article 42A of the Constitution which provides that that the State “recognises and affirms the natural and imprescriptible rights of all children” and that it shall protect and vindicate said rights “as far as practicable”. In recognition of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, this ensures that the juvenile justice system protects

the child’s inviolable rights required for their full development Given Mosepele’s research into the vicious cycle of juvenile crime, respect should be awarded to customary law, which views detention as a last resort for society’s youngest members.

While the 2001 Act revolutionised the juvenile justice system and served as a leader in restorative justice for young people, it is no longer in touch with modern society’s opinions. Society has evolved in its view of young people. The conceptualisation of ‘youth’ has developed in a societal perspective, as well as a scientific perspective. It is time for Ireland to put its two feet on the ground ensure that the underpinning values of the 2001 Act – welfare, education, rehabilitation, and restorative justice – are being actualised in 2025 The ACR must be raised to an age to meet international standards and to view children for what they are – children

by Sophie Eastwood

The enforcement of child maintenance in Ireland is marked by inconsistent judicial discretion, limited enforcement mechanisms, and procedural inefficiencies, which collectively undermine the predictability of outcomes and the welfare of children and custodial parents. In recent years, increased scrutiny has highlighted the inadequacies of the current system, with stakeholders and law reform bodies alike calling for urgent reform Ireland remains an outlier among common law jurisdictions, with fragmented enforcement processes and limited administrative support contributing to low compliance rates and protracted litigation. This paper examines the enforcement of child maintenance payments in Ireland, arguing that comprehensive reform is needed to ensure reliability, predictability, and transparency going forward.

Child maintenance refers to payments that nonresident parents are obligated to make toward the financial support of their children, typically paid to the parent who resides with and cares for the child Under Irish family law legislation, all parents and certain categories of guardians are required to maintain their children according to their needs. Internationally, Article 27 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises every child’s right to an adequate standard of living, placing a responsibility on parents to meet these needs and obliging states to take measures to secure the recovery of maintenance from parents or other responsible parties

Non-payment of maintenance is a serious issue with wide-ranging consequences Financially, it significantly affects children living in poverty and single-parent households, which face higher economic pressures than two-parent households. Beyond finances, non-payment also affects familial dynamics: non-resident parents who pay maintenance tend to have more frequent contact with their children, and conflicts over payments can further

strain parental relationships. In some cases, withholding maintenance may constitute a form of financial abuse or domestic violence, using economic control to exert power over the resident parent. Finally, enforcement is costly and burdensome, leading families already in precarious financial situations to be forced to bear both the loss of maintenance and the additional costs associated with litigation

In recent years, there has been increased scrutiny on the area of child maintenance, with Ireland facing international criticism on its enforcement mechanisms as a result. Consequently, several reviews of maintenance enforcement have been conducted by the legislature. These developments reflect clear progress but also stalled momentum; many recommendations remain unimplemented, raising concerns that reform may be delayed at this preliminary stage.

The judiciary is vested with wide discretion in maintenance disputes, with few judicial or legislative guidelines to direct decisions Maintenance is awarded on a case-by-case basis with other court orders often ultimately being factored into the figure decided. This results in inconsistent judgments and unclear expectations for families attending court.

The absence of alternative dispute resolution exacerbates these problems. Without mediation or other early intervention services, parents must resort to lengthy and often ineffective court proceedings for issues that could otherwise be resolved outside the courtroom While the new Family Courts System may address some judicial specialisation and training issues, it does not provide additional services such as mediation or counselling, leaving gaps in support.

Courts also face challenges due to limited information. Maintenance decisions rely primarily on statements or affidavits of means, which may omit relevant assets or income. This ad hoc approach

allows parents to understate their financial capacity, prolonging court proceedings and complicating enforcement.

Attachment of earnings orders, intended to ensure payments, are similarly flawed. Applicable only to parents on PAYE or private pensions, these orders are invalidated if the parent changes jobs, fails to name their employer, or is self-employed.

Enforcement powers in Ireland are limited compared with other common law jurisdictions. There are no mechanisms to seize bank accounts, revoke licences, or place liens on property, rendering existing orders ineffective and easily circumvented. Bench warrants are similarly ineffective; without a dedicated Garda to enforce them, legal proceedings can stall, rendering non-compliant parents free from consequence

1

As highlighted above, the absence of judicial or legislative guidelines in Irish family law has resulted in arbitrary and inconsistent outcomes. Introducing clear, regularly updated guidelines would increase both predictability and transparency in decisionmaking, while ensuring that families have realistic expectations before entering into legal proceedings

They would also provide a benchmark for voluntary maintenance agreements, reducing the need for litigation by giving parents a clearer sense of what constitutes a fair payment While the concern may be brought that these would unduly constrain judicial discretion, this can be addressed by structuring the guidelines to be persuasive rather than prescriptive, requiring judges to have regard to them while allowing deviation where justified by the other circumstances of the case.

The Department of Justice's recent announcement of a forthcoming child maintenance calculator represents a step towards these recommendations However, it remains unclear whether this tool will carry legal authority or merely serve as a reference point. In addition, the data that this calculator will consider

remain similarly vague, with income, parenting time, and age the only stated factors. Still, if the calculator is implemented effectively, supported by legislation, and periodic review, it could serve as the foundation for a more accessible maintenance system.

One reform that has received insufficient attention in recent review reports is the potential for Revenue to directly deduct maintenance costs. This approach, modelled on the systems in Australia and New Zealand, would allow maintenance to be automatically deducted from a parent's income, linked to their PPS number, much like property tax. As Senator Lynn Ruanne outlined in her submission to the Child Maintenance Review Group, a revenuebased system would greatly improve compliance rates, ensure regular and predictable payments, and reduce the heavy court burden associated with enforcement proceedings. In light of the Minister for Justice’s rejection of a standalone Child Maintenance Agency, empowering Revenue to oversee maintenance collection represents both a pragmatic and necessary alternative

The establishment of the Family Courts has been a positive step toward a more specialised and efficient system, but it is argued that insufficient attention was given to the role of alternative dispute resolution in resolving maintenance disputes. Mediation services could allow families to settle disputes at an early stage, avoiding lengthy and costly litigation. It is therefore submitted that families should be required to attend a compulsory meeting with Civil Legal Aid before initiating court proceedings to encourage voluntary maintenance agreements and decrease the amount of maintenance being litigated.

To ensure compliance and reinforce the authority of maintenance orders, it is submitted that the new Family Courts should be equipped with expanded enforcement mechanisms, including the ability to

enforce contempt of court orders more efficiently, introduce penalties for repeated non-payment, and attach Garda for the bench warrant process, which is currently overly complex and rarely effective. At present, sanctions are difficult to initiate, leaving judges with limited tools to address persistent noncompliance. Simplifying this process would enable courts to respond more swiftly and proportionately to breaches.

Non-payment of child maintenance has serious financial, social, and familial consequences, disproportionately affecting children and lone-parent households, in some cases constituting a form of financial abuse or domestic violence. The current Irish system is fragmented, overly reliant on court proceedings, and constrained by limited enforcement mechanisms, inconsistent judicial discretion, and insufficient support services. Reform is urgently required to create a system that is predictable, transparent, and effective

by Danielle Power

Ireland is frequently described as a ‘tax haven’. This phrase is often thrown around in the media and in public conversation. But what does it actually mean? And is it an accurate description of the Irish tax system?

This article attempts to explain why Ireland has functioned as an attractive tax destination for multinational organisations throughout the decades This explanation will be contextualised within the recent European Court of Justice decision (“CJEU”), European Commission v Ireland and Apple Sales International (the “Apple case”). The broader implications of this decision will also be briefly considered.

In 2003, Ireland cut its corporate tax rate to 12.5 per cent While this comparatively low rate may appear to provide a satisfactory explanation for the influx of multinational entities into Ireland, it represents only part of the full story The structure of Ireland’s tax regime is the primary source of Ireland’s desirability. An economic indicator of Ireland’s status as a tax haven is the discrepancies between the profits-towages ratios of domestic corporations compared to foreign multinationals, with foreign multinationals having a ratio of 800 per cent. This article aims to provide a look behind the curtains into this observable phenomenon.

Before approaching the issues which arise in the Apple Case, it is necessary to dissect the anatomy of Irish tax law as it stood at the time There are many commercial strategies which, in the absence of rules prohibiting them, allow multinational entities to avoid taxation.

The techniques used by multinational entities are known as base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). These tools allow for a far lower effective tax rate

than Ireland’s headline corporation tax rate of 12 5 per cent. The most prominent BEPS tool, responsible for a large amount of profit shifting, was the ‘Double Irish’ scheme A brief explanation of this technically intricate technique is the employment of intellectual property and royalty payment schemes as a vehicle to shift profits.

This species of BEPS tool allowed for profit shifting by multinationals to countries with preferential tax systems, with these profits eventually being transferred to non-EU tax havens such as Bermuda. The benefit for Ireland in facilitating such a state of affairs is that it allowed Ireland to tax vast amounts of profits albeit at low rates. This scheme has led to some commentators describing Ireland as the world’s largest tax haven.

The “Apple Case”

The CJEU has consistently held that Member States’ sovereignty over taxation is limited by the requirement that such sovereignty must be exercised in accordance with European Union Law The European Commission has increasingly initiated investigations into national tax measures under State Aid provisions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Ireland issued pre-emptive tax rulings to two subsidiaries of Apple Inc, Apple Sales International Ltd (“ASI”) and Apple Operations Europe Ltd (“AOE”). Although both companies were incorporated in Ireland, they were considered nonresident for Irish tax purposes This was possible under Irish law which, until 2015, determined corporate residency by place of management as opposed to place of incorporation. The dispute

specifically concerned ASI, whose capital structure was a modified version under the ‘Double Irish’ scheme.

Apple Inc. granted the subsidiaries royalty-free licences, thus enabling these companies to use Apple’s intellectual property to manufacture and sell products outside of the Americas. The Commission took issue with the fact that the tax rulings allowed for the exclusion of profits generated by this use of Apple’s intellectual property. Essentially, the Commission argued that Ireland’s tax rulings allowed the branch to allocate the vast majority of profits to the ‘head office’ of ASI which were not subject to tax elsewhere. This ‘head office’ was argued by the Commission to be artificial and therefore the profit allocation system was not reflective of the actual structure of operations. This substantially diminished ASI’s Irish tax liability, and the Commission argued that this conferred a selective advantage, thus offending Art 107(1) Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) Additionally, the Commission put forward an alternative argument in the event that the profit allocation mechanism itself was found to be acceptable, asserting that the rulings also allowed for non-arm’s length prices.

Transfer pricing rules dictate that profits between affiliates should reflect what parties at arm’s length would charge. The arm’s length principle is directed at commercial relationships between related parties, ensuring that any pricing arrangements between them should be broadly reflective of the market price.

The CJEU overturned the General Court’s decision and held that a departure from arm’s length transfer pricing and profit allocation was indicative of an advantage under Art 107(1). This decision demonstrates the relevance of the arm’s length principle in adjudicating over the capital structure of large multi-national entities Additionally, it is indicative of the CJEU’s willingness to scrutinise areas of national taxation systems under the State Aid provisions

It remains to be seen what the direct implications of this decision are, however, it is clear that this outcome is part of a larger global movement against profit shifting techniques.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”) has been at the forefront of a global campaign against tax avoidance A pivotal development in this campaign has been the “Pillar 2 Solution” which introduces a global minimum effective corporate tax rate of 15 per cent The rationale behind this plan is to disincentivise profit shifting by subjecting multinational entities to the same effective tax rate regardless of which country it chooses to funnel its profits into. Although Ireland was initially hesitant to implement this reform, it eventually dropped this opposition.

These recent developments inevitably prompt the question of whether Ireland has shed the ‘Tax Haven’ moniker and whether this may lead to an exodus of US based multinationals It is submitted that for now, the answer is no An Irish tax partner has shared insights that Ireland has remained attractive to multinationals despite the recent changes, citing the other elements of Ireland’s tax regime and incidental non-tax advantages, such as the skilled Irish workforce. While Ireland may have formally committed to the global minimum tax rate and phased out the notorious “Double Irish” scheme, comparable arrangements are still utilised, such as the ‘Green Jersey” scheme. In summary, Ireland’s status as a ‘Tax Haven’ has arguably not been displaced despite OECD and CJEU activism.

by Chloé Asconi-Feldman

The Defamation (Amendment) Bill 2024 has been in development for several years, culminating in the 2022 Report of the Review of the Defamation Act 2009. The 2009 Act governs defamation law in Ireland and was published at a time when online defamation was only beginning to emerge. Sixteen years later, defamation has taken an entirely new form in a publication landscape that has transformed drastically Publishers are no longer clearly identifiable, given the prominence of private publication without editorial oversight This lack of transparency, couples with the emergence of generative AI systems with the power to widely disseminate defamatory statements, creates a disjointed legal landscape.

Although the Defamation (Amendment) Bill 2024 introduces several reforms, its scope still remains limited. Among its proposed reforms, this paper will focus on one of great concern: the abolition of juries from High Court defamation cases

Juries have been abolished in almost every other type of civil proceeding, most recently under the Courts Act 1988. Part 3 of the proposed legislation will abolish juries in High Court defamation cases. Minister for Justice Helen McEntee justified this reform, stating it would “reduce the likelihood of disproportionate awards of damages, significantly reduce delays and legal costs, and reduce the duration of court hearings” Juries have been abolished in almost every other type of civil proceeding, most recently under the Courts Act 1988

his proposal has faced opposition across the legal landscape, notably from The Law Society, which has expressed concern that abolishing juries could distance the public from the justice system. The purpose of trial by jury is to safeguard litigants from the influence of powerful actors and vested interests, by ensuring that cases are decided by members of the

public who participate in the administration of justice Professor Neville Cox has noted that defamation concerns the right to reputation, a right that exists not in a person’s own head but within the community. Here, a jury functions as the voice of the community in assessing the matter

By contrast, the use of juries in defamation cases has also been contested, with some arguing that their abolition may be beneficial. The abolition may bring greater certainty for stakeholders as the law will be upheld with greater clarity, reducing the need for costly appeals. The Law Reform Commission have argued that juries can lack the expertise required to navigate complex defamation principles, resulting in imprecise and inconsistent awards Jury trials are generally slower than other hearings and are often associated with higher defamation settlements. In Higgins v The Irish Aviation Authority, Justice Binchy described the jury’s award as “so unreasonable as to be disproportionate to the injury sustained”. Critics further note that retaining juries can impede access to justice due to the significant costs involved in pursuing a case However, it remains unclear in practice whether removing the jury would meaningfully address this issue

The role of juries in defamation law has been debated across jurisdictions Section 11 of the UK’s Defamation Act 2013 abolished jury trials in defamation cases, except in exceptional circumstances While the intention was to reduce legal costs, evidence suggests that the reform had the opposite effect, making it more difficult for individuals to pursue defamation claims. Irish law, however, differs from British law in that it provides a

right to a good name under Article 40 of the Constitution

This role of juries in defamation cases has historically been considered more than a procedural matter, serving as an important substantive safeguard. Juries assess whether a statement is defamatory by reflecting community values and social attitudes in a way that judges alone may not Central to defamation law is the concept of the “hypothetical referee”, as in the ordinary reasonable reader who represents the standard by which defamatory meaning is assessed Juries, as laypersons, are generally closer to this standard than judges

This principle is illustrated by several Australian cases in the early 2000s, where judges suggested that imputations of homosexuality could be defamatory, while juries concluded that such imputations were not. In New South Wales, a party may elect to have a jury hear a defamation case, demonstrating the ongoing recognition of the jury’s role in determining defamation.

The landscape surrounding defamation continues to evolve. While the Defamation (Amendment) Bill 2024 is long overdue, the removal of juries may not provide the anticipated solution. While the assumption is that abolishing juries will reduce litigation costs, rising legal costs are not unique to defamation trials, but reflect a broader trend across Irish civil litigation Access to justice should no doubt remain a priority, yet juries represent the community that defamation affects. The community determines what is defamatory, and removing juries may disadvantage laypersons more than it assists them. The Bill is not yet enacted into law, so its impact will become clear in due course.

“Fifty Years of the office of the

by John Lonergan Editor-in-Chief, Trinity College Law Review

On the 21st of October, the Trinity College Law Review was delighted to ring in the new academic year with a visit by Ms Catherine Pierce as part of TCLR’s Distinguished Speaker Series Ms Catherine Pierce is the Director of Public Prosecutions and has over twenty years experience working as a practising solicitor in a range of criminal law and regulatory roles. She was interviewed by Professor David Kenny, and we are immensely grateful for his time.

One aspect of the role Ms Pierce emphasised was the ten-year term of office for the Director. She highlighted the difficulty in removing the DPP from office and touched on the fact that there have been very few officeholders thus far She emphasised that it is a non-renewable term, which ensures that the officeholder does not make decisions based on whether they will be reappointed

Ms Pierce touched on the relatively small size of the DPP’s office compared to similar offices elsewhere. Indeed, the prosecutor’s unit which decides on cases to pursue is comprised of around thirty people. Likewise, few barristers are employed directly by the DPP. Instead, a panel is used for Circuit and Central Criminal work. Still, the office has grown from 4 lawyers in 1975 to 300 staff in 2025.

Ms Pierce also stressed the importance of the duty to give reasons when taking a decision not to prosecute She emphasised that this helps victims of crimes understand why a decision has been made and in what way She stressed the importance of transparency and openness in the office. Part of this push for transparency and openness has been the move to promote the DPP’s fiftieth anniversary and educate the public about the office’s purpose and role. This is in addition to the publication of the book “50 Years of the Office of the Director of Public ProsecutionsOffice of the Director of Public Prosecutions” by Dr Niamh Howlin of UCD

Interestingly, while discussing the decision-making process, Ms Pierce noted that there is a cohort of individuals who are not charged despite the fact there is likely enough evidence to convict. The reasons given for not charging such individuals is that it might not be in the interests of justice to do so, or the offence is so insignificant as to not warrant being charged with the offence

We would like to thank Orlagh Flood in the DPP’s office for her support in organising this event.

TCLR is immensely grateful for the generous support of our patron sponsor, Arthur Cox. Without this kind support, TCLR would be unable to host the Distinguished Speaker Series.

by Zoya Kherani, Auditor, DU Law Society

On 29 September, Trinity College Dublin’s Law Society experienced an unprecedented moment in its long institutional history; we hosted a sitting Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first African American woman appointed to the Court, addressed an audience of more than 400 students in what became one of the most significant events the Society has ever organised.

For me, the experience was not merely historic; it was formative. It marked the moment in which my role as Auditor shifted from a title I had been elected to, into a responsibility I actively inhabited.