This report would not be possible without the time, effort, and kind advice of the following people:

Mr. Eric Dueweke, University of Michigan

Ms. Larissa Larsen, Ph.D., University of Michigan

Mr. George Davis

Ms. Kimberly Hill-Knott

Ms. Corinne Kisner

Mr. Kevin Mulder

Ms. Dominic Smith

Ms. Sandra Turner-Handy

Ms. Rachel Wells

Climate

University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture & Urban Planning

Kelly Gregg, Peter McGrath, Sarah Nowaczyk, Andrew Perry, Karen Spangler, Taylor Traub, & Ben VanGessel

Advisors: Larissa Larsen & Eric Dueweke

December 2012

Source: By Michigan Municipal League

Source: By Lowell Boileau detroityes.com

According to projections, the average annual temperature in Detroit is expected to increase 1.5-5.4°F by 2050. In the wake of increasing temperatures and changing climate conditions, many cities across the world recognize the need for climate action planning. This style of planning provides a proactive approach to climate change.

Comprehensive climate action planning involves both mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation aims to decrease the extent of climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Conducting a greenhouse gas inventory informs which mitigation strategies are needed and in which sectors. Adaptation aims to decrease the impacts from climate change by identifying distinct places and groups of people that may be disproportionately affected by a changing climate. Conducting a vulnerability assessment informs which adaptation strategies are needed, and where to implement them.

Literature often defnes climate ‘vulnerability’ as ‘exposure plus sensitivity.’ Exposure refers to the presence of biophysical hazards in the current environment, and sensitivity refers to the degree to which a community is harmed by a given exposure. We conducted an initial vulnerability assessment in order to provide a foundation for future climate action planning.

Community-based non-profts, environmental organizations, universities, state agencies, private organizations and the City of Detroit comprise the DCAC. The DCAC is a grassroots effort, led by Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice (DWEJ). The primary goals of the DCAC include:

1. Reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the sustainability and well-being of Detroit

2. Increase the resilience of Detroit’s social, built and natural environments

Eight ‘Work Groups’ encompass the DCAC in order to ensure fair representation. These eight Work Groups include transportation, solid waste, homes and neighborhoods, businesses and institutions, community public health impacts, energy, research, and parks, public space and water infrastructure. Once assembled, the Work Groups will determine indicators, strategies and goals in order to monitor progress. We compiled a list of potential indicators, strategies and goals that serve to aid these Work Groups.

Our vulnerability assessments focus on two issues: extreme heat and fooding. We selected these two issues because local climatologists have identifed extreme heat and increased precipitation as key concerns for Detroit.

With regard to extreme heat vulnerability, our assessment combines exposure and sensitivity. Exposure factors include areas with high percentages of impervious surfaces relative to pervious surfaces and low tree coverage. Sensitivity factors include the number of people over the age of 65, the number of households without access to a vehicle, household income, and educational attainment.

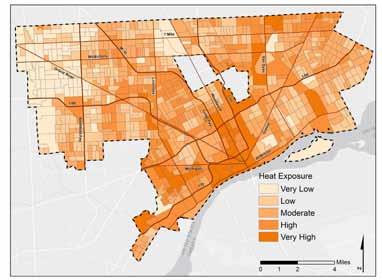

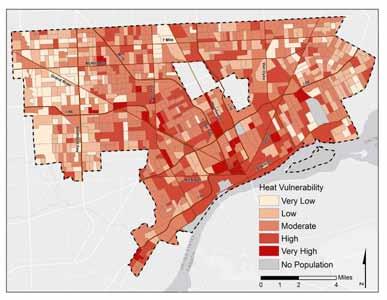

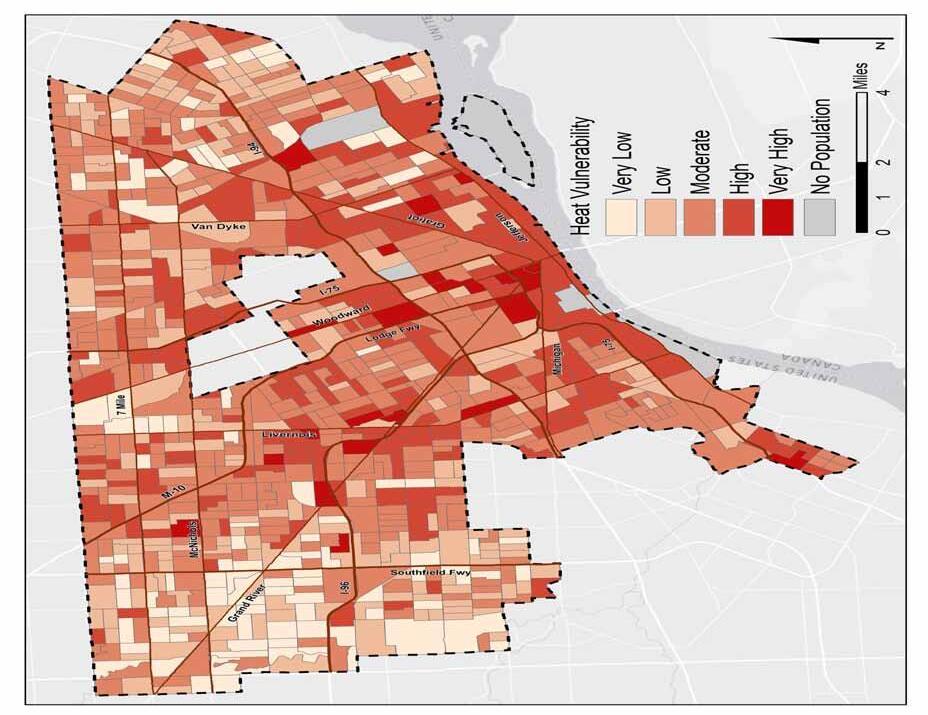

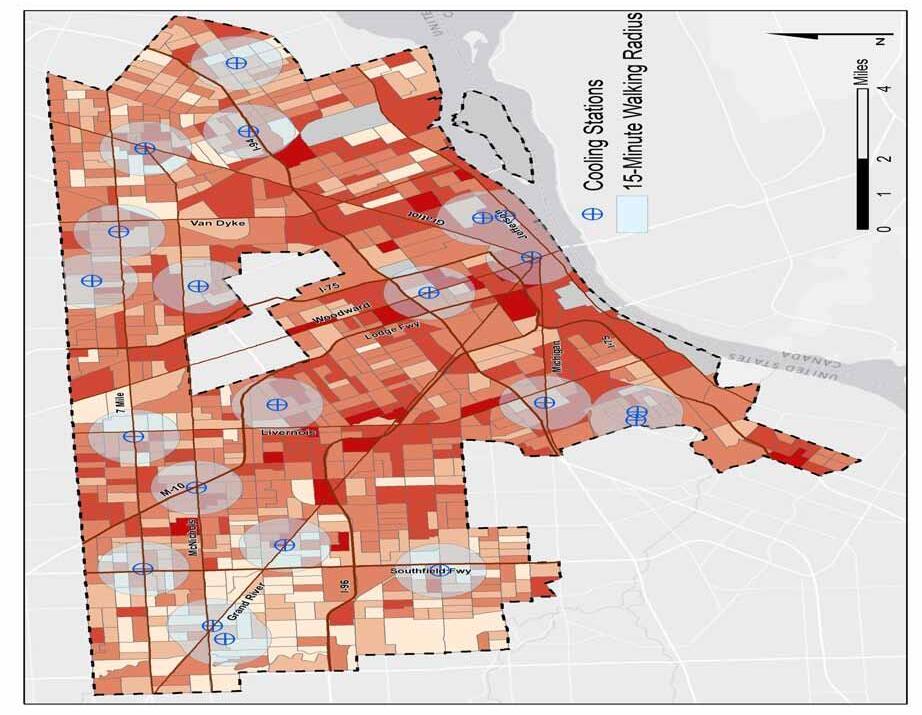

The heat assessment indicates that the greatest areas of vulnerability include the downtown core, along with the adjacent neighborhoods northwest of downtown. In addition, only 29% of the population is within a 15-minute walking distance of designated cooling centers, which the City of Detroit designates on an annual basis.

The fooding vulnerability assessment examines the vulnerability of current infrastructure systems, as well as household level vulnerability.

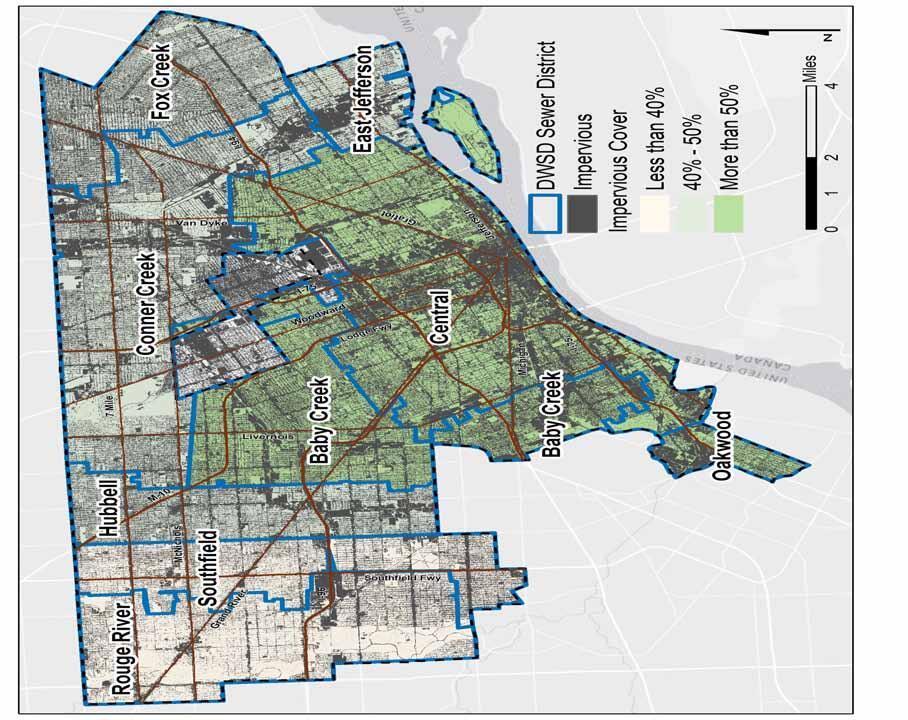

With regard to infrastructure, the analysis focuses solely on exposure factors. The primary exposure factor includes the runoff burden created during intense storm events. Land cover, soil type, and slope are the three factors that determine runoff burden. Data pertaining to the age, size, capacity and technology of existing infrastructure is necessary to determine the sensitivity of the City’s nine sewersheds. Additional information from Detroit Water and Sewerage Department is necessary for a more comprehensive analysis.

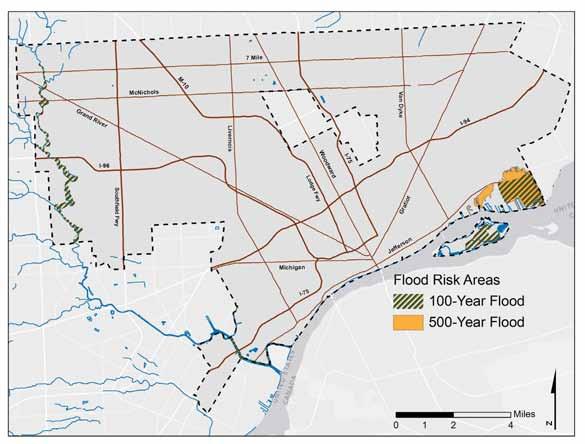

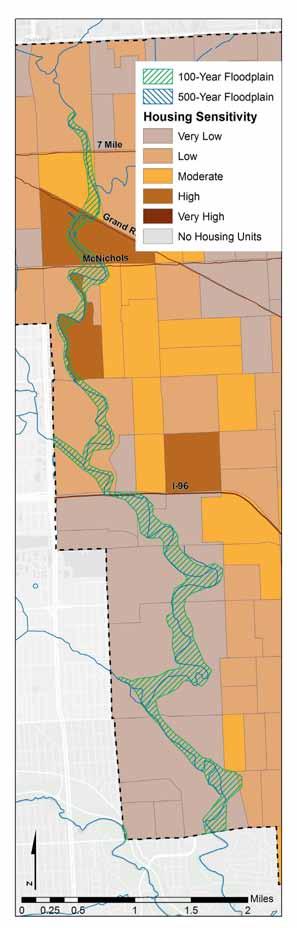

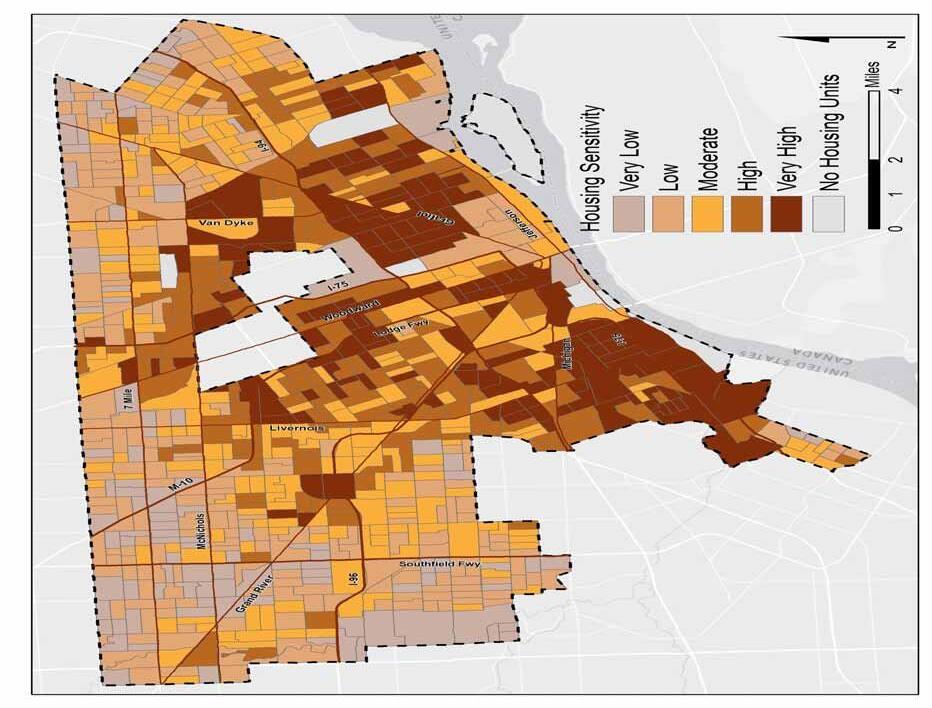

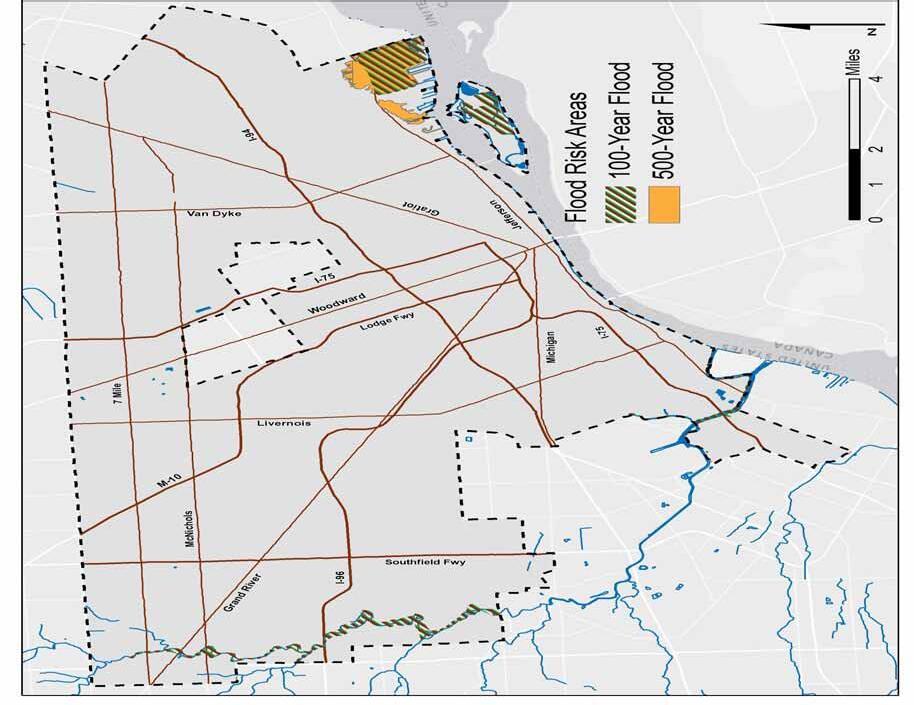

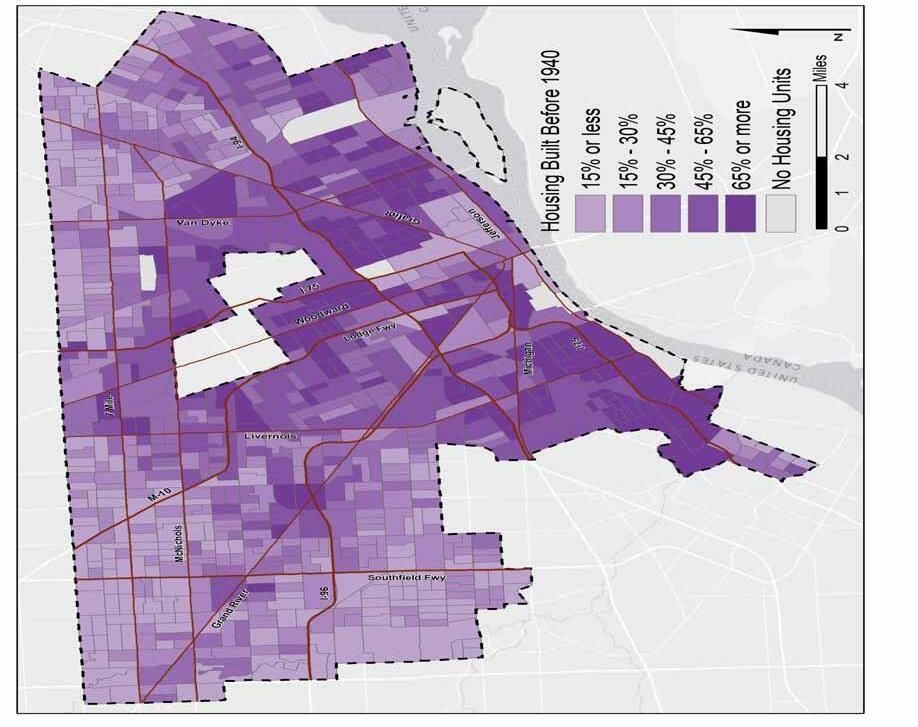

At the household level, the exposure factor is determined from foodplain designations (100 and 500 year). Age of housing stock (pre-1940) and median household income constitute household sensitivity.

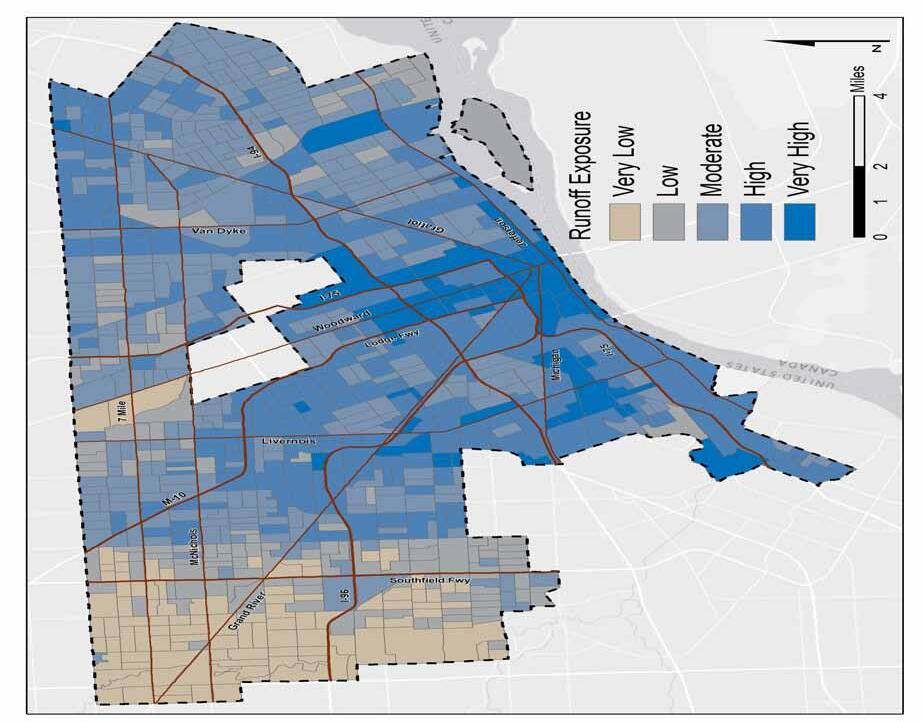

Similar to the heat assessment, system food vulnerability concentrates around the downtown core and extends northward. Household food vulnerability is seen in southeast Detroit and in the northwest fashion along the Rouge River.

The results of the vulnerability assessment informed a set of fnal recommendations. These fnal recommendations include:

• Reconsider distribution and location of designated cooling centers

• Reduce impervious surfaces in identifed ‘hotspots’

• Increase tree planting in identifed ‘hotspots’

• Acquire additional information from DWSD for further food vulnerability analysis

• Ground-truth the most vulnerable heat and food areas to further target efforts at the neighborhood scale

Global climate change threatens to disrupt the function and livability of our cities. Although Detroit, Michigan, will not face the drastic effects of rising sea levels, the city is projected to experience higher temperatures, more frequent and intense precipitation events, and fuctuating lake levels. All of these effects will place further strain on the City of Detroit’s ability to provide services and keep it’s most vulnerable residents safe. With this in mind, the Detroit Climate Action Coalition (DCAC) has partnered with the University of Michigan in order to assess how Detroit can lower it’s current impact on the environment to mitigate efforts and prepare itself for the effects of climate change through adaptation.

Traditionally, municipal-level climate action plans have focused on mitigation— actions that reduce Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions that aim to prevent climate change. Common recommendations included increasing mass transit options and increasing building energy effciency. Although these mitigation policies generate positive outcomes, increasingly, recent climate action plans recognize that mitigation at the global scale must be coupled with adaptation at the local level.

While not a comprehensive document, this report from the University of Michigan intends to positively contribute to the DCAC’s planning process. We begin ith a brief history and current context section that addresses the relevant Detroit-specifc information, and summari es the current trends in climate science. Our Vulnerability Assessment applies current climate science pro ections to Detroit, and identifes places and populations in Detroit that are at risk from specifc effects of climate change. This Vulnerability Assessment ill form the basis for the Work Group reports, hich ill allo DCAC stakeholders to gain an accurate snapshot of where the city of Detroit currently stands, survey other plans and best practices from other cities, and show how stakeholders can measure progress. ased around the DCAC’s ork groups, e ill suggest a set of area specifc indicators from scholarly research, best practices from other climate plans, and feedback from DCAC orkgroup members. Finally, our conclusions section will summarize our fndings, and present our planning priorities to the DCAC.

Strategies that focus on reducing GHG emissions from human activity and promote the use and development of non-fossil fuel energy sources

The adjustment of human or natural systems in response to actual and/or anticipated climate change to lessen the potential negative impacts.

Detroit’s previous triumphs and current struggles are well documented. Once a symbol of American industrial might, the city’s name is now a synonym for urban blight, abandonment, and uncertainty. Today Detroit is a minority-majority city that has lost population at an alarming rate— the city suffered a 25% drop in population from the 2000 to 2010 census, and the city’s current population of 713,777 is 38.5% of its 1950 peak.1 Despite the decline in population, the city is still forced to pay for the infrastructure and legacy costs of a city of 1.8 million people. This creates a tremendous strain on the city’s remaining tax-base, and the city departments charged with providing basic services.

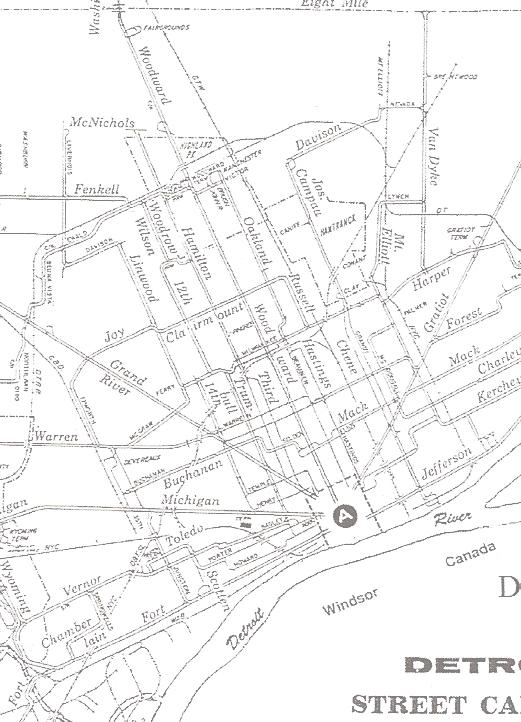

In 1701, the French explorer, Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac recognized the Straits of Detroit as a strategic location on the Great Lakes, and founded the city as Fort Ponchartrain du Detroit. Founded as a military installation to protect the lucrative fur trade, French settlers soon noticed that Detroit had excellent soil for farming. The French Crown offered free land to settlers, who developed ribbon farms—long and narrow farms that allowed every settler to have access to the Detroit River. Detroit became an important agricultural center, and the ribbon farms formed the basis of the city’s unique and often overbuilt street pattern. The fort became one of the largest trading centers in North America by 1760.

From the early 1800s through the turn of the century, while the fur trade declined, Detroit continued to grow as a manufacturing and trading center. Detroit enjoyed a diverse economy, well-known for making stoves, train cars, shipbuilding, cigars, and pharmaceuticals.2 The city expanded in population, from just 1,650 in 1810 to 285,704 in 1900.3 The city itself also grew

in territory, annexing neighboring townships, building over the former farmland, and covering rivers to create sewers. While the city grew, compared to its Midwestern peers of St. Louis, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Cleveland, or Chicago, Detroit was still a relatively small city—a small manufacturing outpost.4 In fact, when the Detroit Tigers baseball franchise began play in 1901, some even wondered how long the Major League team would last in Detroit.5

This perception changed with the advent of the automobile. Following the turn of the century, Detroiters began to apply their expertise in manufacturing, machining, forging, and metallurgy garnered from other industries and applied this knowledge to automobile manufacturing. Within twenty years, Detroit became the undisputed center of the nation’s booming and lucrative auto industry. By 1930, the industry consolidated into an oligopoly of Ford, GM, and Chrysler - the “Big Three” - all of which centered their operations in or around Detroit. Detroit’s economic fortunes have been closely linked to the domestic auto industry ever since.

In many ways, Detroit is the quintessential twentieth century city, mostly due to the rapid, unplanned growth encouraged by the auto industry. The city’s built environment and territory expanded rapidly, from just a small loop located within Grand Boulevard in 1900, to its current borders of 139 square miles by 1926.6 This expansion of territory was not possible without a meteoric rise in population. From 1900 to 1930, the city’s population exploded from 285,704 to 1,568,662. While Detroit is widely known as a blue-collar, manufacturing town, the auto industry created massive fortunes for auto barons such as Henry Ford, John and Horace Dodge, and the Fisher Brothers, and employed thousands in managerial, engineering, and professional ranks.

Also, from 1900 to 1930, Detroit attracted hundreds of thousands of unskilled laborers from Central and Eastern Europe, and from the American South.7 By the roaring twenties,

the former sleepy outpost on the Detroit River became a booming metropolis, fo ing in money from the prosperous auto industry and the prohibition-era illegal alcohol trade with Canada. However, the Great Depression hit Detroit hard, as many factories cut shifts or closed their doors altogether. Production of war material in World War II brought Detroit out of the depression, and Detroit became known as the “Arsenal of Democracy. The city experienced another infux of white and black migrants from the American south to fll the factories that ran on three shifts, but Detroit’s wartime era of full employment was short-lived.8

Following the end of World War II, while the metro area of Detroit continued to grow, the city of Detroit began to decline. A confuence of federal subsidies, structural change in the auto industry, changing tastes, and poor race relations encouraged many whites to leave the city. For many years, Detroit’s population loss was commonly perceived as the classic example of “White Flight.” Indeed, Detroit became the manifestation of the Kerner Commission’s worst fears—a wealthy ring of predominantly white suburbs surrounding an impoverished, underemployed, and majority African American city core.9 However, as the years have gone by, many black residents have left for the suburbs as well. Indeed the decline in services and an increasing tax burden has created a vicious cycle. Today, the city has fe er fnancial resources to serve its most vulnerable residents.

Detroit’s meteoric rise and decline has created unique challenges for the urban environment. The city’s prosperous industrial economy allowed blue-collar autoworkers to purchase their own single-family homes, and Detroit became well known as a city of “house and yard” people.10 Once a symbol of prosperity, many of Detroit’s homes today lack insulation and modern, energy effcient H AC systems. Also, Detroit was built at a time when auto-ownership was on the rise, and the city’s planning professionals favored an auto-dependent urban form. In 1958, the city shut down the last of its streetcars, while highways were constructed throughout the city. Today, Detroit faces the

challenge of large areas of vacant land and an auto-dependent transportation system. Moreover, during the late 1800s, to make way for development, many of the city’s creeks and streams were paved over, or turned into sewers—decreasing pervious surface for storm water management. Much of the city’s infrastructure is technologically out of date and has suffered from years of deferred maintenance. Climate change threatens to increase the pressure on this fragile infrastructure system, and the city’s ability to cope is currently limited.

1. U.S. Census Bureau

2. Hyde, Charles K. Detroit: An Industrial History Guide. Detroit: Detroit Historical Society, 1980.

3. U.S. Census Bureau

4. U.S. Census Bureau

5. Bak, Richard. A Place for Summer: A Narrative History of Tiger Stadium. Detroit, Mich: Wayne State University Press, 1998.

6. City of Detroit Annexation Map, 1932, Detroit City Planning Commission Collection, Roll 4, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, Detroit, MI.

7. Zunz, Olivier. The Changing Face of Inequality: Urbanization, Industrial Development, and Im migrants in Detroit, 1880-1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

8. Gregory, James N. The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

9. United States. Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. Washington: For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off, 1968.

10. Young, Coleman A., and Lonnie Wheeler. Hard Stuff: The Autobiography of Coleman Young. New ork: iking, .

Source: Detroit Skyline 1954. Wayne State Historical Image

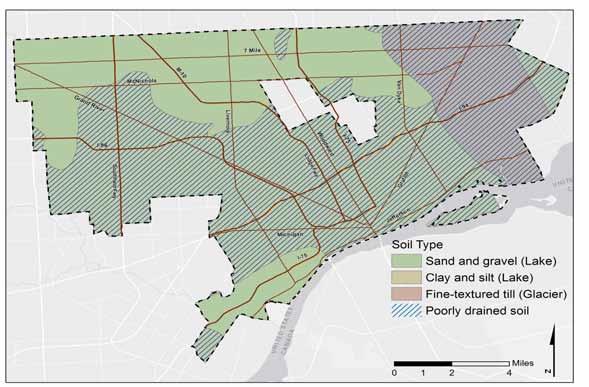

Michigan’s current landscape was shaped predominantly during the last ice age. The movement of the last ice sheet, known as the Wisconsin Glacier, left the most direct impact with its retreat occuring 14,000 years ago. When the planet warmed and the ice melted, the water would carry the scoured soil and rocks away from the retreating glacier, ith fner-grained particles able to travel farther.1 The Great Lakes themselves are a product of this retreating glacier—large basins that became the repository for much of the melted ice.2 These historic processes determined many of the characteristics of the current landscape, from soil types to hydrologic fo s, and in some regards, the historic forest composition as well.

Understanding the soil types is crucial in the face of changing climate. Particle size determines the amount of water and nutrients that soil can hold, which affects agricultural viability, forest and plant dynamics, and stormwater management. Generally, larger particles (sand and gravel) have higher rates of drainage due to the greater amount of space between particles, whereas fner soils silts and clays retain ater for longer periods, and can become saturated quickly. For agricultural purposes, silt soils are ideal for growing crops—they hold water and nutrients, but do not become dense, hard, and brittle like dried clay.3

A key impact of these historic geologic processes is Detroit’s most common current soil types—soils produced from glacial outwash, and soils derived from deposited lake sediments.

Touching briefy on glacial out ash, e see an accumulation of fne-grained material, or till, into ridges that delineate the farthest extent of glaciation. The subtle ridges of accumulated glacial till have over time defned the area’s watersheds, dictating the course of rivers and streams, and infuence drainage dynamics.4

The other surface type that is apparent is derived from the deposition of lake sediments. As the Great Lakes began to fll, they ere not always the shape that we know today. In fact one in particular, Lake Maumee, encompassed an area that included part of present-day Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair, the Detroit river, and inland parts of Canada and Michigan. Lake dynamics are such that sediments will accumulate over time, carried by rivers, wind, and erosion to the lake. Sand and gravel tends to accumulate along the outer portion of the lake, hile fner silt and clay sediments will settle in the inner, deeper lake areas.5 Detroit and the surrounding area has a presence of both types, though silt and clay predominate in the sections closer to the Detroit River.

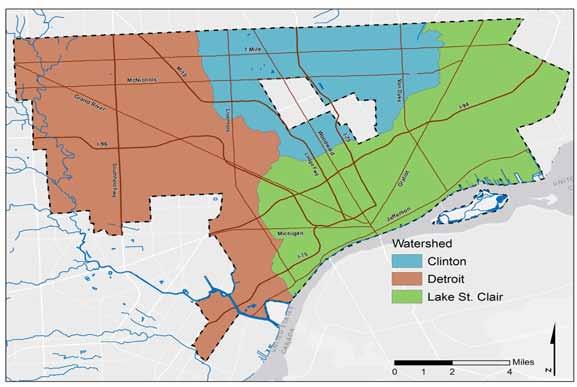

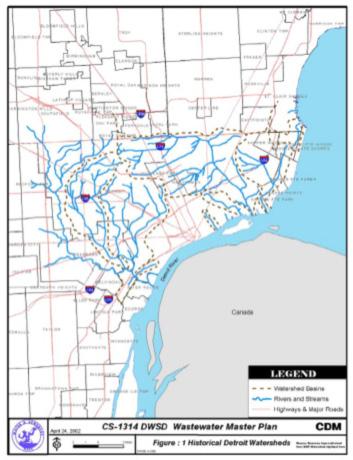

The historic glacial processes played a role in the creation of present day watersheds. The deposited sediments created ridges, essentially boundaries, which charted the course for water to follow. Detroit is placed within the greater context of the Great Lakes watershed, a massive process that moves water, in order, through Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, and out the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic Ocean. Locally, however, there are three watersheds falling within the boundary of Detroit, two emptying directly into Lake St. Clair (Lake St. Clair and Clinton watersheds) and the other into the Detroit River (Detroit watershed). Additionally, the Huron watershed to the west of Detroit, plays an important drainage role in the region, passing through Wayne County and emptying into Lake Erie, south of Detroit.6 Each watershed is further

broken down into subwatersheds, which can be useful scales when analyzing the impacts of impervious surfaces and stormwater management practices.

Within Detroit itself, there were a number of streams and rivers that served to drain the area. Many of these streams were subsequently routed into culverts and underground pipes as the city expanded, trying to conceal its stormwater system. Understanding the hydrologic processes of the city will be important as we move forward facing climate change because of the stresses that will be put on the system from increased storm events. With a combined se er overfo system, additional stress on or relief from the natural drainage system will have impacts on sewage discharges into the Detroit River. One innovative suggestion looks at “daylighting” these streams that have been enclosed by pavement. Opening these waterways could restore some of the historic fo s, landscape, and habitat, while also diverting urban stormwater runoff, lessening the chance for a system- ide overfo .7

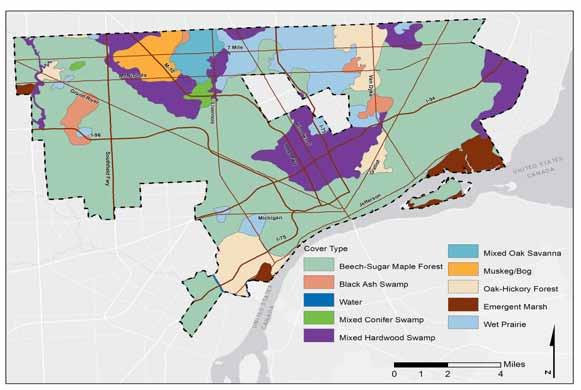

The glacial and soil deposition processes, along with broader climate characteristics, also played a role in determining the vegetation makeup of the region. Categorized as the mesic southern forest, pre-settlement Detroit experienced the presence of beech and sugar maple dominant communities. These species do especially ell on fne-textured glacial till and sandy lake plains that are well drained, conditions that were previously established in this area. Soils are generally fertile with high nutrient content and soil organism content, due to the decomposition of deciduous leaves and branches. Where drainage is poorer and seasonal pools are common, a wetter habitat was formed, favoring beech and an oak-hickory mix.8 Along the eastern border of the city, as well as in the southwest, there were historically much wetter, swamp and marsh conditions. To this day, these areas remain more prone to fooding than other parts of the city.

Today, the U.S. Forest Service undertakes a Forestry Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program to periodically assess the current forest composition as well as develop predictive models. While there is no direct data for the urbanized Detroit metro region, the surrounding areas indicate a fairly high diversity of species, characterized by the historic beech, sugar maple, birch, oak, and hickory, but also a heavy elm and cottonwood presence. Looking into the future, the predictive models tend to emphasize the likelihood for elm and cottonwood to become dominant, with a minor role for oak and hickory. This is largely based on climate modeling processes, where shifting climates may limit a species’ range.9 For local communities, it will become important to take broader predictions on regional or national forest types. In addition, coupled with knowledge about local topography and hydrology, develop a working list of species that can thrive in different biophysical circumstances.

Source: By Sombraala

1. Michigan’s Geological Landscape. Michigan Department of Natural Resources. 3 October 2012 http://www.michigan.gov/ dnr/0,4570,7-153-10370_22664-60296--,00.html.

2. Larson, Grahame; Schaetzl, R. (2001). “Origin and evolution of the Great Lakes”. Journal of Great Lakes Research (Internat. Assoc. Great Lakes Res.) 27 (4): 518–546.

3. http://soil.gsfc.nasa.gov/index.php?section=78

4. http://www.hrwc.org/the-watershed/features/geology/

5. City of Detroit Annexation Map, 1932, Detroit City Planning Commission Collection, Roll 4, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, Detroit, MI.

6. http: cfpub.epa.gov surf county.cfm fps code

7. Detroit Water and Sewerage Department Wastewater Master Plan

8. Mesic Southern Forests. Michigan Natural Features Inventory

9. http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/atlas/tree/ft_summary.html

Detroit Historic egetation

Source: SE C G, egetation Circa Southeast ichigan

Map Prepared By: University of Michigan Detroit Climate Capstone

Although climate and weather are directly related, they are not the same. Weather describes the day-to-day conditions in a specifc place, hile climate is the accumulation of recorded weather trends in a region over a longer period of time. The distinction between weather and climate is important because it differentiates temporary weather variability from long-term projected trends measured over decades.

While the terms “global warming” and “climate change” are often used interchangeably, climate change more accurately conveys the multitude of impacts caused by the trend of higher global temperatures: increased duration and frequency of drought, increased number of extreme precipitation events, rising sea levels, and ocean acidifcation.1 The global climate is sensitive to a number of natural and human caused activities. Natural events that affect the climate include variations in the Earth’s orbit, changes in the intensity of solar radiation, the circulation of the oceanic and atmospheric currents, and volcanic activity. Human activities contribute to climate change through GHG emissions. However, other activities such as deforestation and rapid changes in land cover contribute to global climate change.2

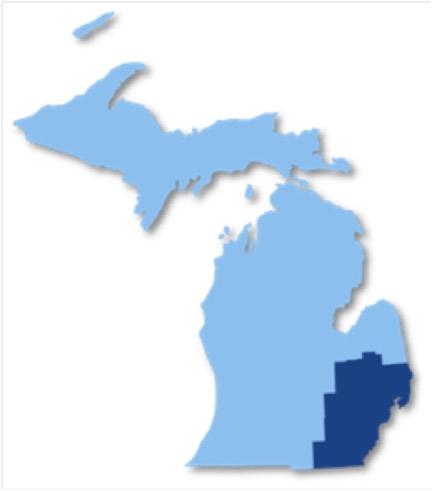

In the United States, climate scientists at the National Climatic Data center use climate divisions as a baseline geography for analysis. Generally, climate divisions are areas that share uniform climate characteristics, and are housed within the boundary of one state. Detroit is located within the Southeast Lower Climatic Division of ichigan see fgure belo . This region is bounded by the Ohio border to the south, Lake Huron, Lake St Clair, and Lake Erie to the east, and extends west to include the cities of Flint and Ann Arbor.3 To predict climate change impacts for a specifc region or city, scientists utilize the technique of downscaling. Climate downscaling connects global-scale predictions, such as Atmosphere-Ocean General Circulation Models (GCMs), with regional dynamics to estimate local- or regional-scale information.4

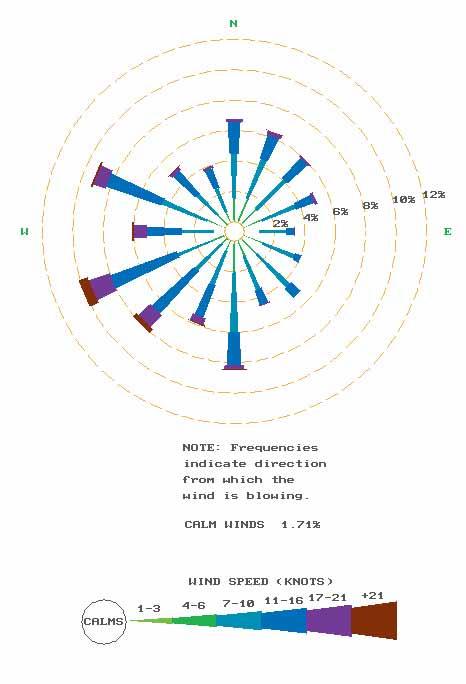

Detroit and the rest of the Southeast Lower Climatic Division of Michigan are categorized as a humid continental climate. Humid Continental climates are known for great variances in seasonal temperatures—warm to hot and humid summers, and cold winters. Historically, Detroit’s temperatures were generally moderate. In the past, the region rarely experienced prolonged periods of hot, humid weather in the summer or extreme cold during the winter. During the summer months, temperatures from the mid 60s°F through 80s°F were the norm, and occasional easterly winds and local lake breezes from Lake St. Clair moderated temperatures. In the winter, the average daily high temperature range was 23°F to 35°F with an average winter temperature of 27°F. The proximity to Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair as also refected in inter temperatures.

Wind Speed and Direction in Detroit

Source: http://climate.geo.msu.edu/Stations/2102/NARRAT.txt

September-November57.1

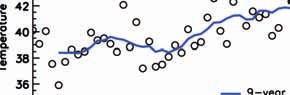

Annual Seasonal Temperature (1958-2012)

Source: Station 202103 National Climate Data Center

Hottest Day on RecordJune 25th, 1988104.3 °F

Hottest Month on RecordJuly 2011Ave. Temp. 79.3 °F

Coldest Day on RecordJanuary 21, 1984-21.1 °F

Coldest Mnth on RecordJanuary 1977Ave. Temp. 12.8 °F

Detroit Temperature Extremes (1958-2012) (Detroit Proper, not DTW)

Source: Station 202103 National Climate Data Center

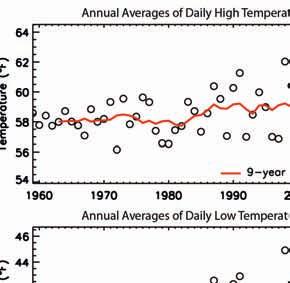

Annual Averages of Daily Temperatures

Source: GLISA The Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Detroit, MI

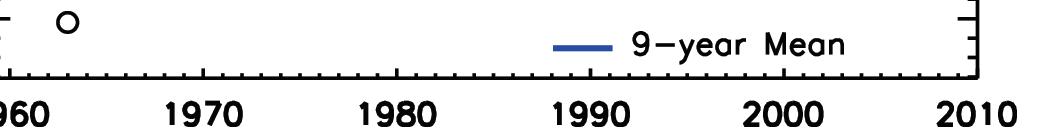

Detroit’s annual precipitation averaged 33.58 inches, and was fairly evenly distributed throughout the year. The driest month for Detroit is February, with 1.85 inches of precipitation, and June was the wettest month, with 3.51 inches of precipitation. Summer precipitation came mainly in the form of afternoon showers and thundershowers. Annually, thunderstorms occurred on an average of 36 days. Winter precipitation was generally a mix of sleet and snow, and January was the snowiest month—averaging 11.29 inches of snowfall, for an average snow depth of 6.38 inches.

In terms of extreme weather, while Michigan is shielded from the worst effects of hurricanes, it is located on the northeast fringe of the Midwest tornado belt.5 Wayne County experienced 27 tornadoes since 1950 while only 4 have crossed into Detroit city limits.5 The lower frequency of tornadoes occurring in Michigan may be, in part, the result of the colder water of Lake Michigan during the spring and early summer months—the national prime period of tornado activity.

Total Annual Precipitation, Southeast Michigan

DETROIT PRECIPITATION EXTREMES

Greatest Single Day TotalJuly 28, 19764.90 inches

Greatest Monthly Total July 18788.76 inches

Driest Month Frebruary 18770.00 inches

Detroit Precipitation Extremes

Source: Station 202103 National Climate Data Center

In Detroit, between 1960 and 2010, average annual temperatures have increased by 1.4°F. This warming trend is expected to continue throughout the 21st Century. Although 1.4°F seems like a modest change, small increases in average annual temperature drastically increase the probability of extreme weather, such as heat waves, excessive heat events, droughts, and torrential rains. In particular, excessive heat events, the number of days per year with a high temperature above 90°F, will likely increase. Between 1960 and 1980, Detroit averaged 11 days exceeding the 90°F mark per year. During the later quarter of the century, the number of days exceeding 90°F rose slightly to 12 and to in the frst decade of the s. Ho ever, by the end of 21st Century, Detroit is projected to experience 36 to 72 days exceeding 90°F per year.

Source: GLISA The Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Detroit, MI

Similar warming trends will affect winter temperatures. Between 1960 and 1980, an average of 50 days had a daytime high of 32°F or lower, an average of 7 days was 0°F or lower, and only 3 years stayed above 0°F. Generally, average winter temperatures are slowly increasing nearer to the freeze-thaw point hich poses signifcant risks to surface and subterranean infrastructure.

The increase in temperatures is expected to bring a rise in precipitation. In the last half century, Michigan experienced an 11% increase in total annual precipitation, and increases in annual precipitation are expected to continue. Precipitation in the summer months is expected to increase slightly, while spring, fall, and winter are expected to see a noticeable increase. While winters will have less snowfalls, they will experience more precipitation in the form of rain. The average number of snowfalls is projected to decrease by 50%. Much like the rise in temperatures, in addition to experiencing more precipitation, Michigan is also expected to experience more frequent and more intense storms, increasing the likelihood of foods.

On the ground, the increases in temperature and precipitation will create a diverse set of challenges for the City of Detroit’s municipal departments and its residents. The large number of excessive heat events can exacerbate the symptoms of other diseases, and increase the risk of heat exhaustion, heatstroke, or death. Because of Detroit’s combined sewer system, more frequent and more intense precipitation can increase the amount

of untreated sewage released into the Detroit and Rouge Rivers. This increases Detroiters’ risk and exposure to waterborne diseases. Also, increased precipitation and fooding can cause severe damage to private property and public infrastructure. These and other adverse effects, of climate change will be discussed further in our ulnerability Assessment section.

SOURCES

1. Pew Center on Global Climate Change, “The Causes of Climate Change,” Science Brief 1 (August 2008) at 2, available at http://www.pewclimate.org/docUploads/globalwarming-science-brief-august08.pdf

2. EPA, “Frequently Asked Questions About Global Warming and Climate Change: Back to Basics,” available at: <http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/downloads/Climate_ Basics.pdf.

3. Great Lakes Integrated Science Assessment, “Historical Climatology: Southeast Lower Michigan”.

4. Bader, D.C., et al. 2008. Climate models: An assessment of strengths and limitations.A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Department of Energy, ffce of Biological and Environmental Research, Washington, D.C.

5. http://www.crh.noaa.gov/grr/education/tornado/

The following section summarizes a few of the major weather-related events in Southeast Michigan since the start of the 20th Century. Often, extreme weather events and shifting weather patterns result in catastrophic blows to economic systems and local infrastructure, as well as outbreaks in health-related issues.

“SNOWIEST WEEK”

Roughly 30 inches of snow fell over a 6 day period — the 3rd & 4th biggest snowfalls in the 20th century.

This winter ranked as the coldest winter in southern Michigan’s history. The average temperature from December to February was 18.7 degrees.

Considered to be one of the worst in history, this storm included nearly 5 inches in snowfall and wind gusts over 70 mph. More than 235 sailors lost their lives on the Great Lakes and dozens of ships, including large freighters, sunk.

Source: The Paragraph.com

“DUST BOWL” & “HEAT WA E

The 1930s represent one of the dryest periods in Michigan, referred to as the ‘Dust Bowl.’ This deade includes the driest year in recorded history (1936). The continual, long-standing droughts placed extreme economic pressures on farmers during The Great Depression. In addition, the ‘Heat Wave’ of 1936 included 7 straight days of extreme heat, resulting in nearly 400 deaths in Detroit.

Source: HourDetroit.com; Illustrated by Arthur E. Giron

THA SGI I G WEEKEND SNOWSTORM”

Recorded as the largest snowstorm of the 20th century, more than 19 inches of snow fell on Southeast Michigan during Thanksgiving weekend.

1976-1977

“COLDEST WINTER E ER

The Winter of 19761977 marks the coldest in Detroit history. Detroit failed to reach 32 °F for 45 consecutive days, resulting in an average January temperature of 12.4 °F (normal averages exceed 24 °F).

EXTREME HEAT AND DRYNESS

This summer included 39 days in which temperatures exceeded 90 °F, along with 5 days that exceeded 100 °F. In addition, some Michigan cities recorded less than oneinch of rainfall from May through June.

This massive cold outbreak resulted in roughly 57 straight hours of sub-zero temperatures, including the coldest day in Detroit history.

Roughly 2.5 inches of freezing rain, snow & sleet fell in Southeast Michigan, resulting in the 3rd largest blackout in history — roughtly 425,000 homes lost power.

JULY 7, 1997

More than 15 tornadoes were reported across the state — the most in Michigan history. Seven deaths and more than 100 injuries occurred, and total damage to property and crops exceeded $140 million.

Source: UPI.com

WINTER, 1997-1998

The average temperature in Detroit during this winter was nearly nine degrees above normal, resulting in only 14.5 inches of snowfall (17.5 inches below normal).

More than 115 cases of West Nile occurred in Wayne County, resulting in three deaths. Elderly populations proved to be most vulnerable to the outbreak. As a result, Wayne County granted $200,000 to city and township governments to eradicate the spread of West Nile.

As a result of poor regulation and reliability standards, 50 million Americans —l ranging from Michigan to the eastern seaboard — lost power for multiple days. Municipalities rallied in order to cater to vulnerable populations and ensure the safety of its citizens.

Source: Pasty.com

Source: Examiner.com

FLOODING & SEWAGE ER L WS

Extreme weather events resulted in more than 37 billion gallons of se age overfo ing into Southeast Michigan waterways — an increase of 11 billion gallons from the previous year.

Nearly 48 inches of rain fell in 2011. A majority of the rainfall occurred as a result of intense May and September thunderstorms. One storm in May resulted in fooding, as Detroit’s infrastructure could not handle the excess downpour.

WEST NILE OUTBREAK & LYME DISEASE

Michigan recorded roughly 170 cases of West Nile, including 10 fatalities (all of which were elderly patients). Local authorities are also paying attention to a sizable increase in black-legged deer ticks — these ticks are often the primary source of Lyme Disease.

Source: By JWhiting360

Based on the projected changes from the Great Lakes Integrated Science Assessment (GLISA), extreme heat and precipitation are the biggest risks for Detroit. Air pollution, specifcally elevated ground-level o one, ill also be a concern ith increasing temperatures, but e ere not able to uantify air pollution for this assessment. In this section, e ill identify areas of high vulnerability pertaining to heat and fooding by uantifying concentrations of exposure and sensitivity in Detroit.

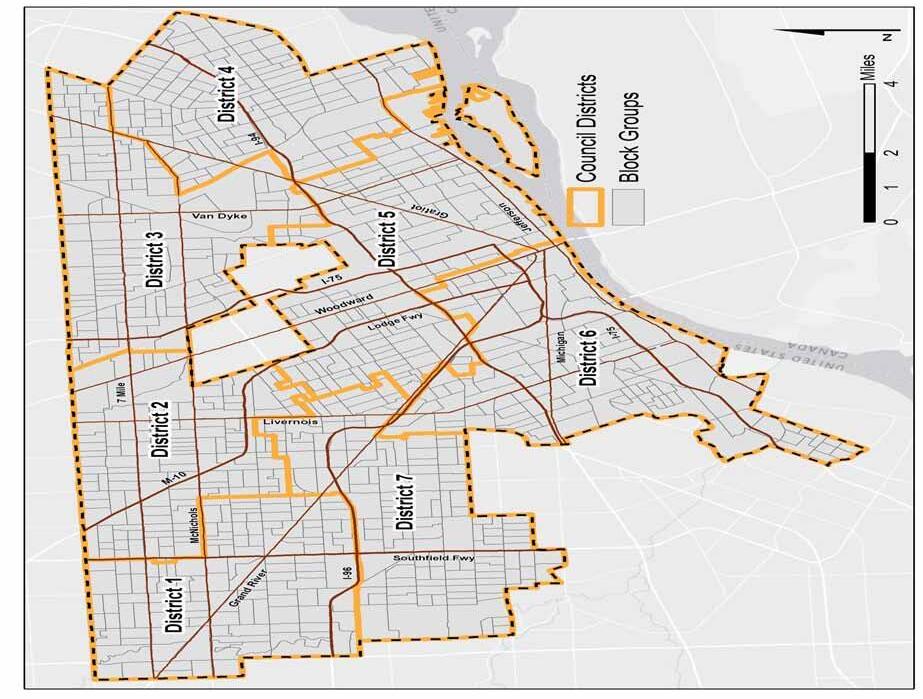

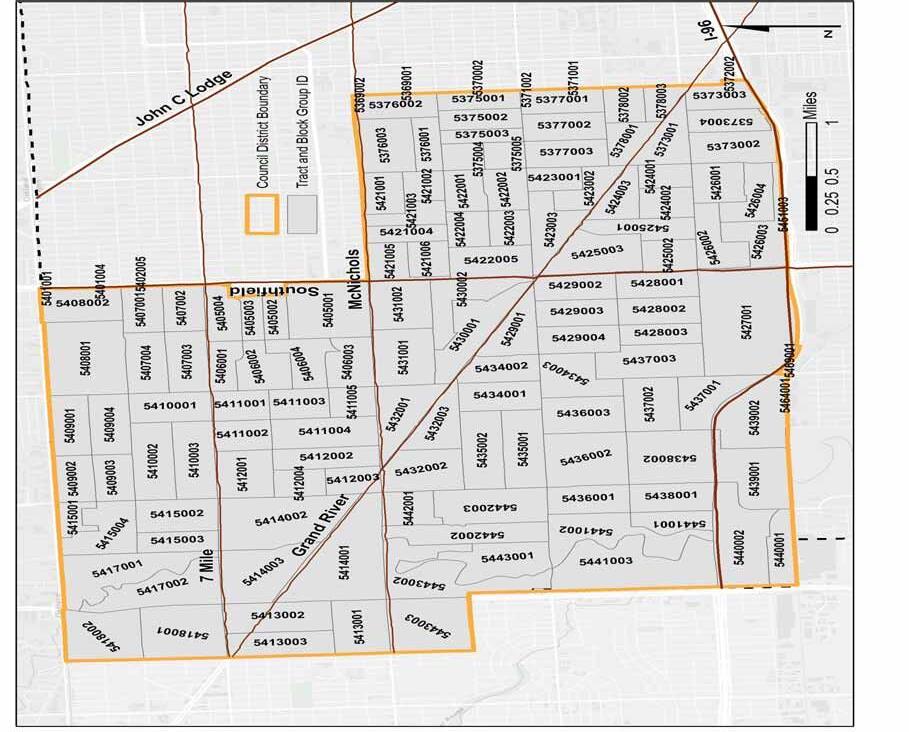

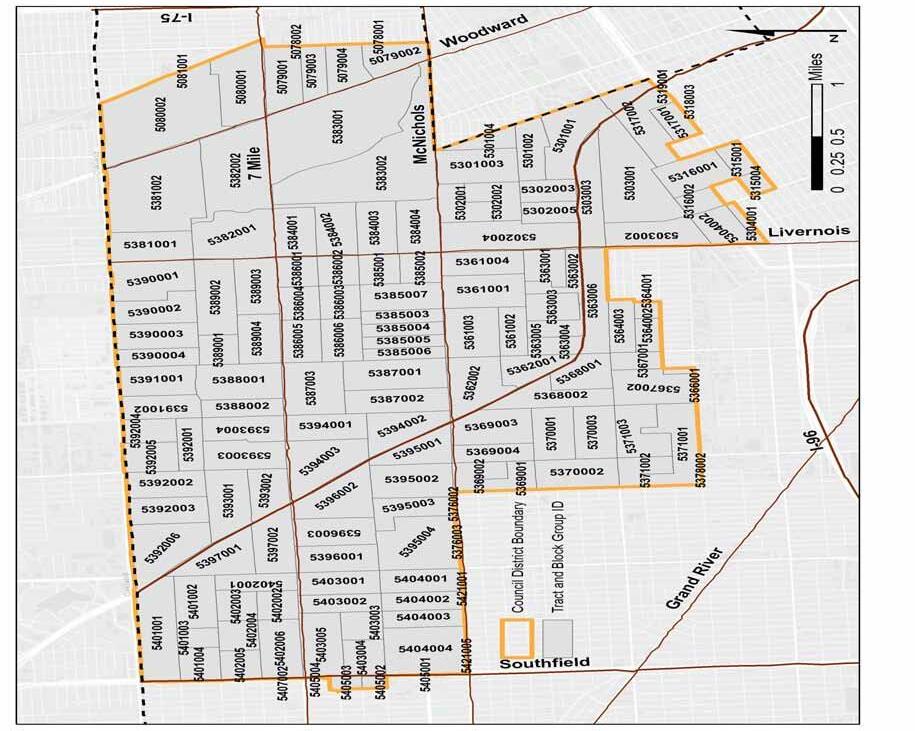

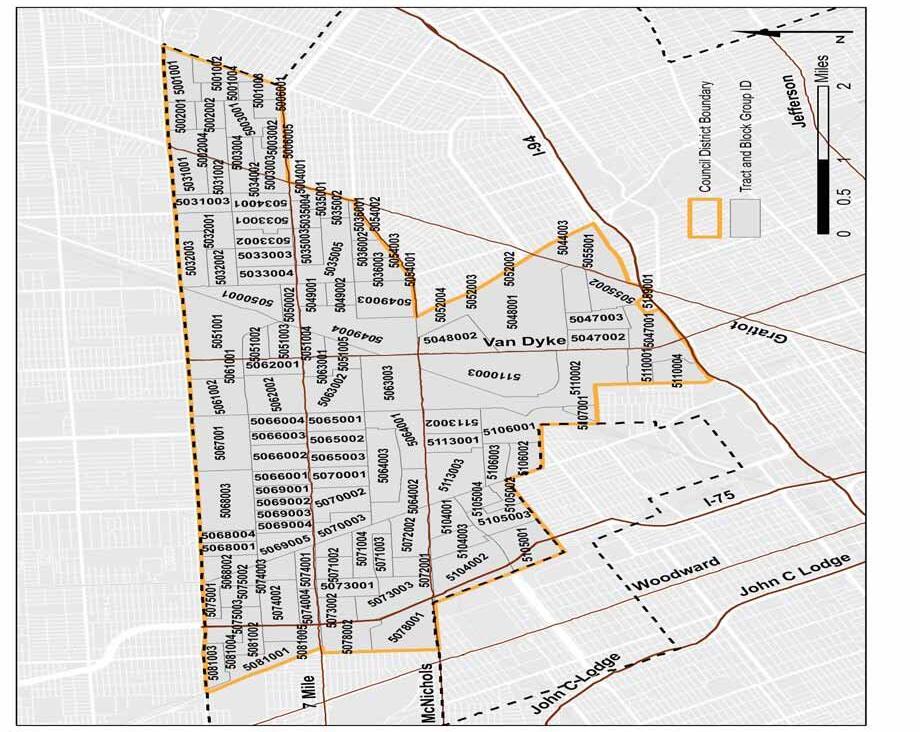

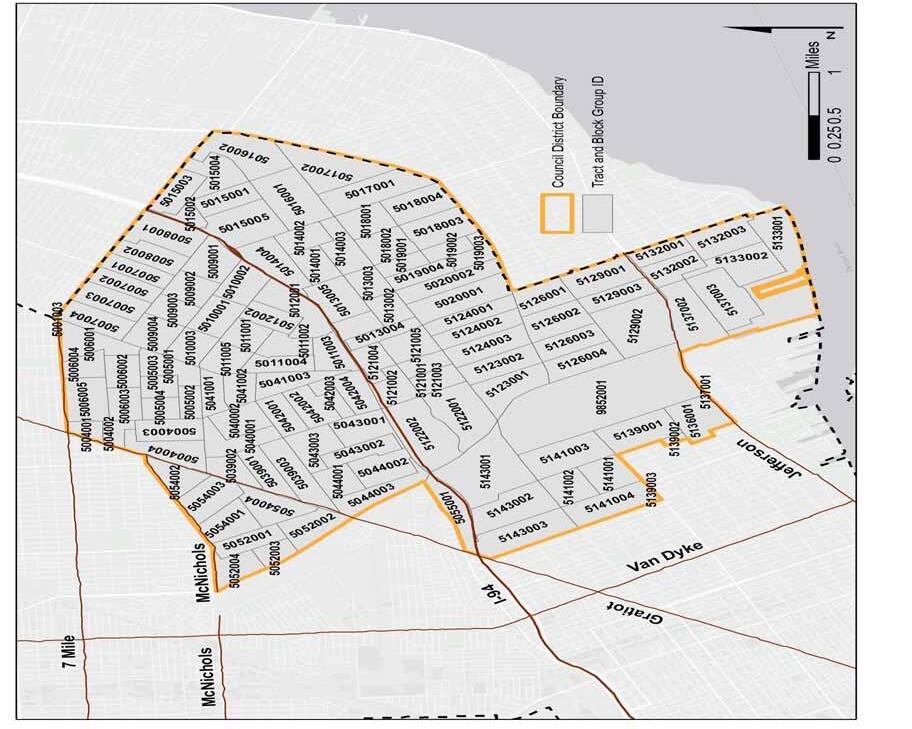

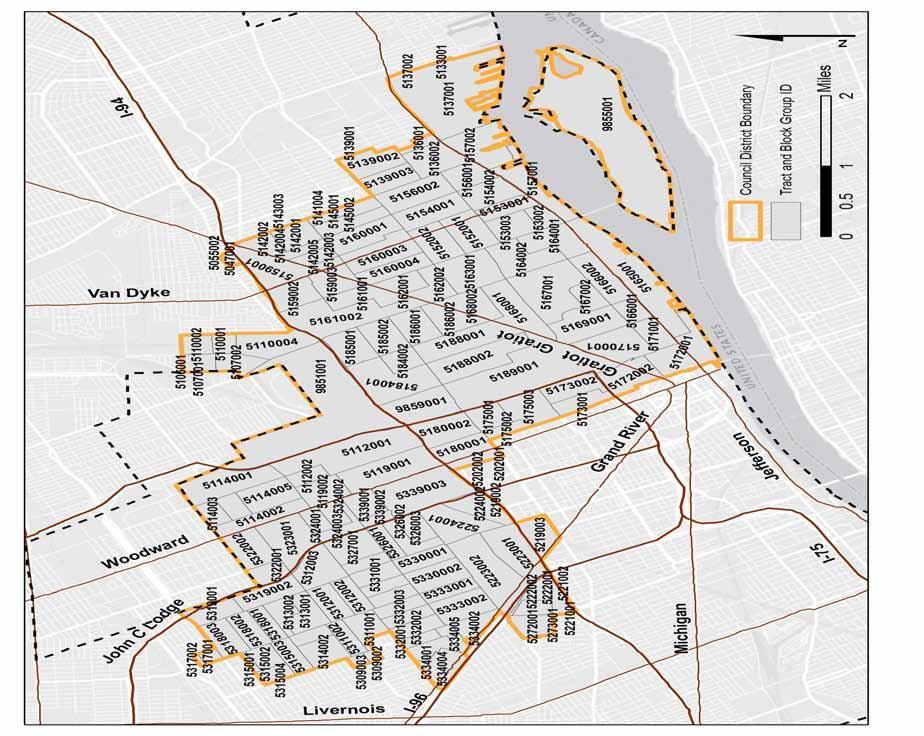

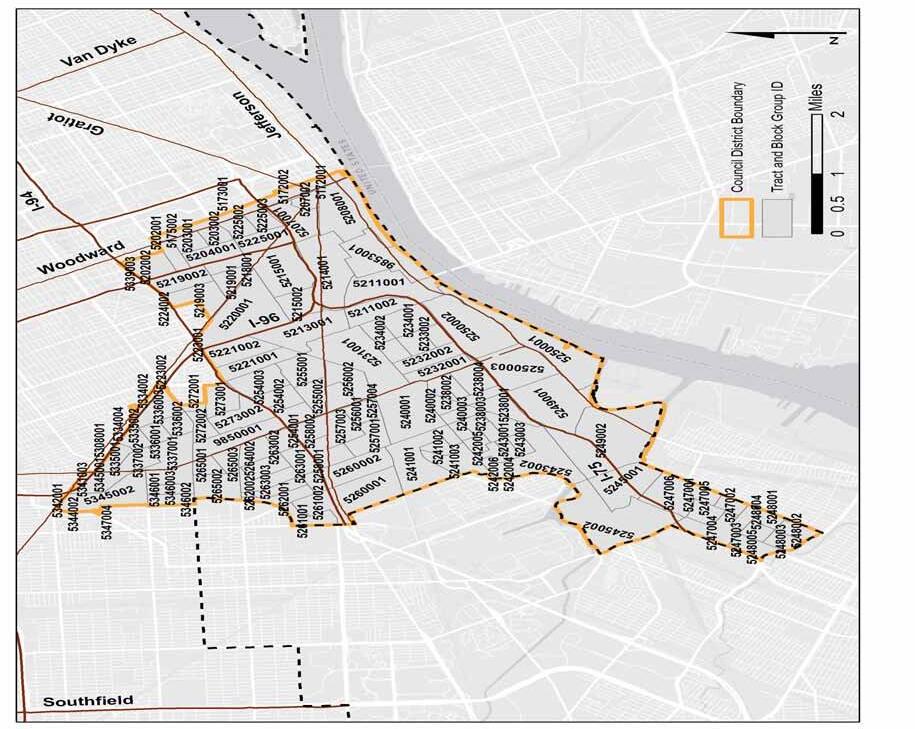

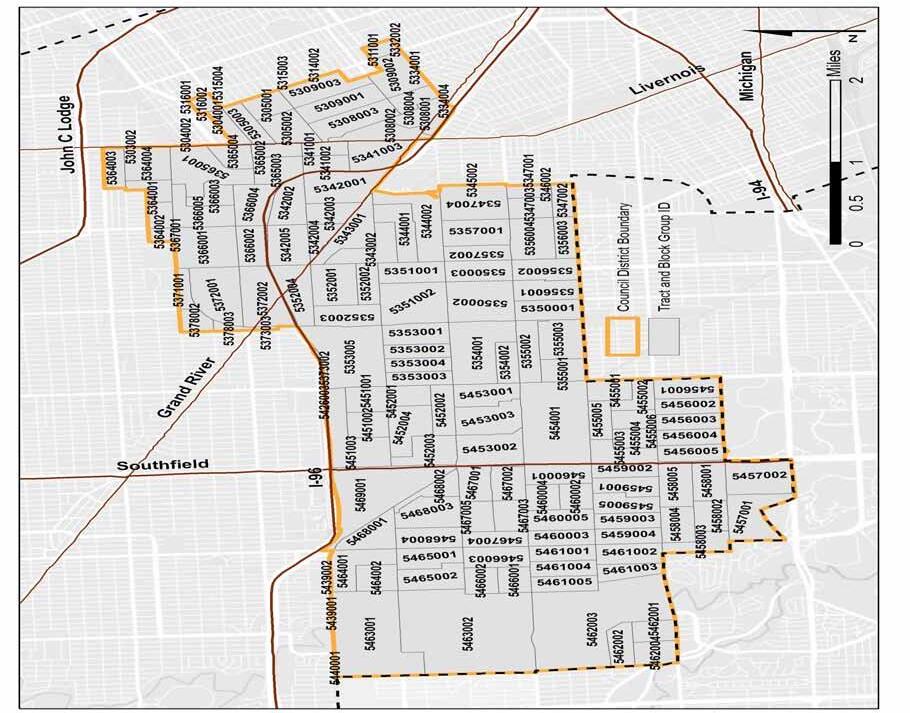

A vulnerability assessment is used to understand and uantify vulnerability. Vulnerability is the combination of biophysical exposures, such as the actual temperature or rainfall change, and sensitivity of a population or system. Sensitivity factors are often human variables such as population demographics. This vulnerability assessment is a geographic overvie of concentrations of vulnerability in Detroit. ur assessment used data from the American Community Survey, an ongoing national survey by the .S. Census ureau that collects detailed information on housing, income, education, and other population characteristics. We obtained data at the block group level, an area that contains bet een and , individuals. This is the smallest geographic level for hich demographic data is published. y mapping areas of high exposure and high sensitivity, these assessments can identify areas of high vulnerability. ur methodology ill explain the process of ho e identifed and combined exposure and sensitivity.

Source:Heat ap by ichael Ho e ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

Geographic location ithin a region can drastically infuence the exposure to heat. In Detroit, the average annual temperature from - has increased by . , hereas the average annual temperature for Ann Arbor has only increased by . over the same period.1 Although . seems like a modest change, a small increase in average annual temperature drastically increases the probability of extreme heat events and droughts. y , Detroit is estimated to experience extreme heat event days per summer, up from days on average bet een - 2

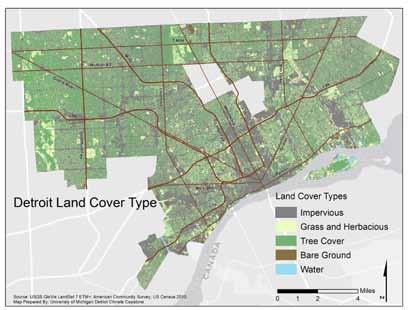

Source: SGS Glo is LandSat ET American Community Survey S Census ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

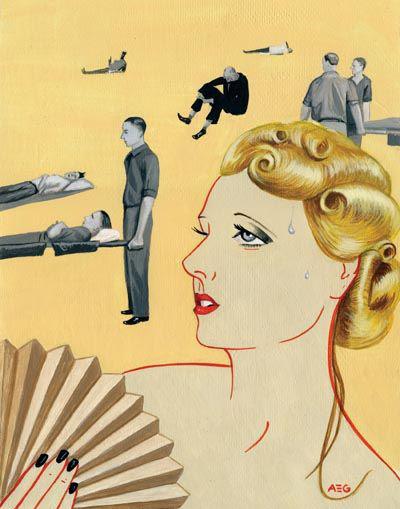

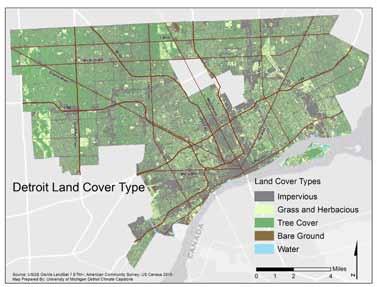

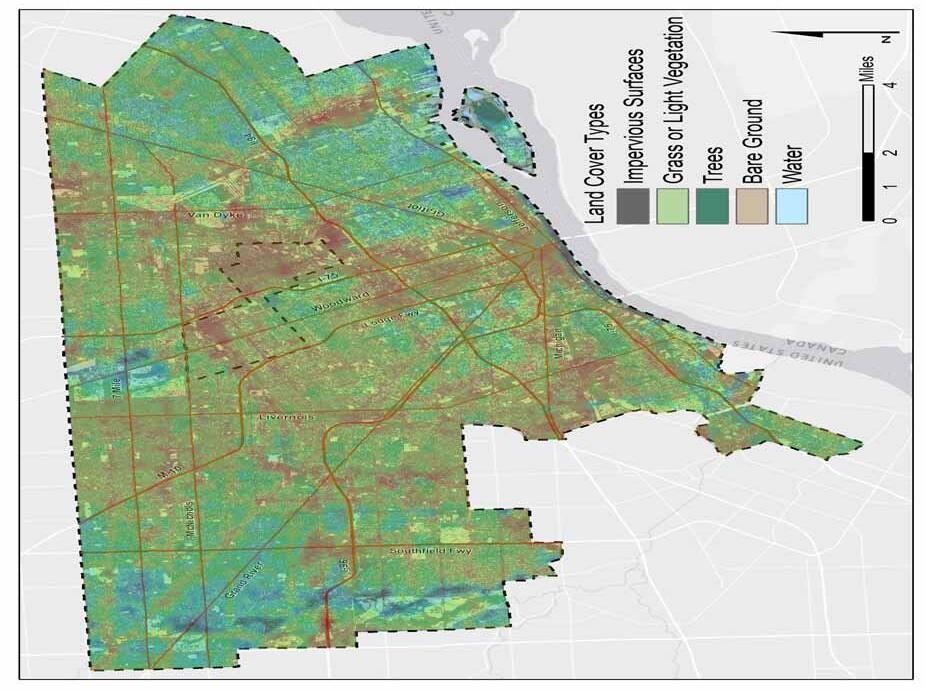

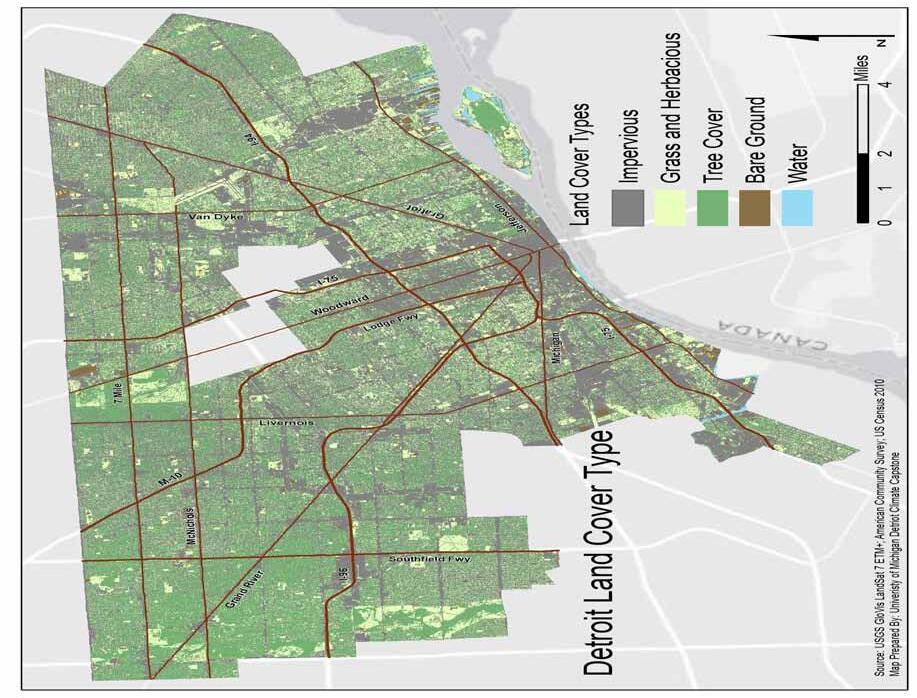

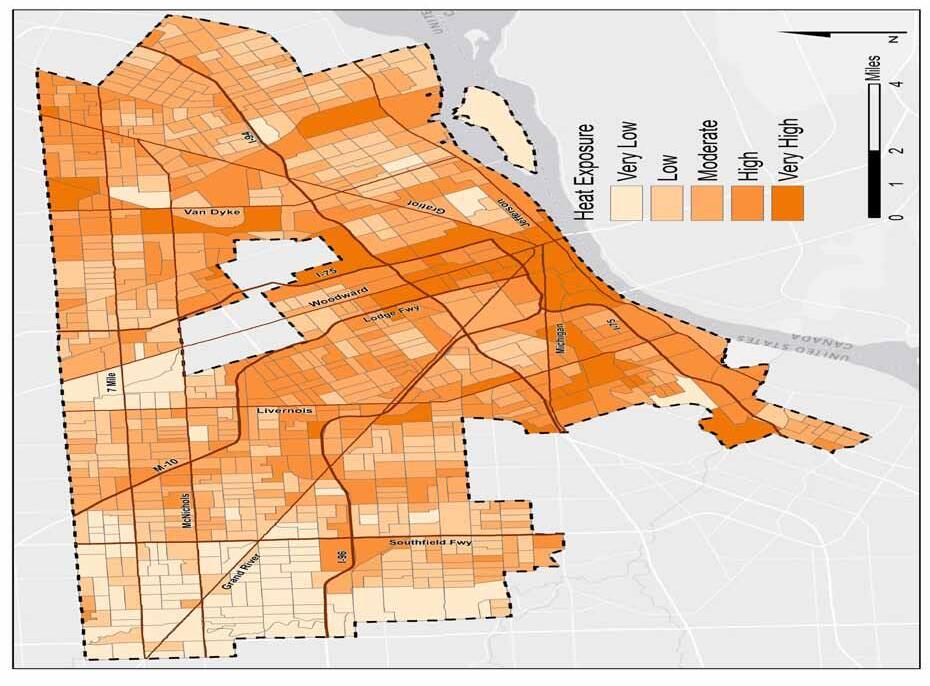

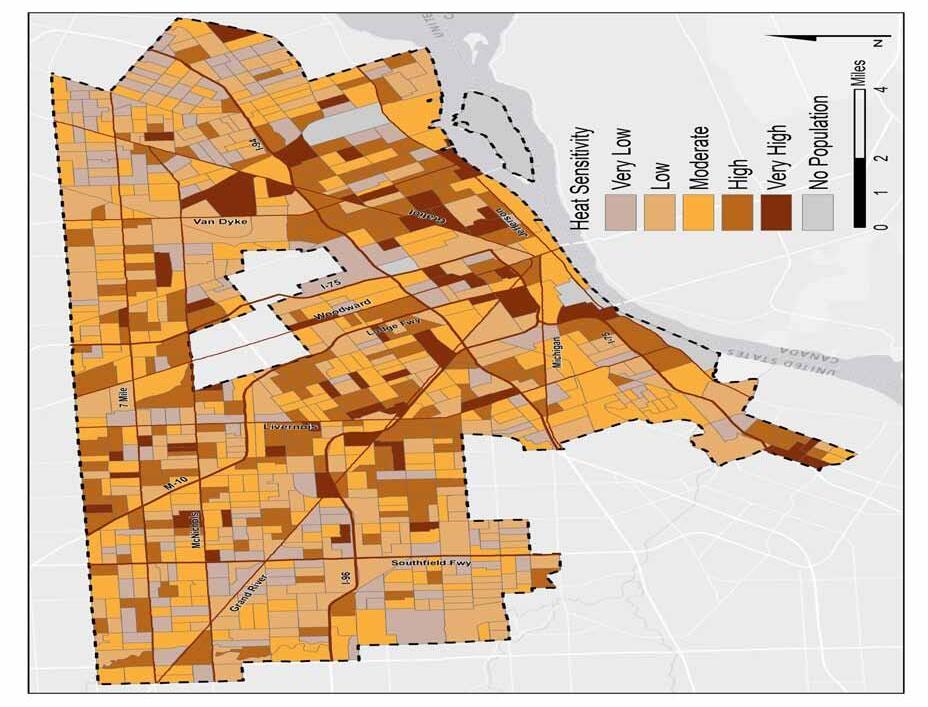

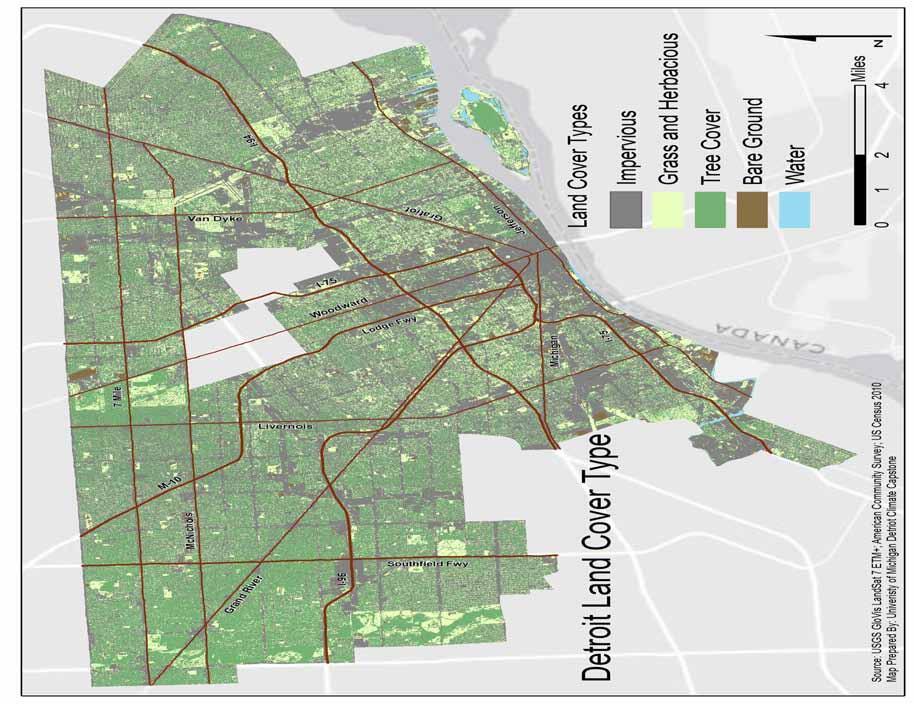

ur analysis included t o land cover variables that impact effects of extreme heat events: impervious surfaces and tree canopy. Impervious surfaces, such as asphalt and concrete, absorb high amounts of heat and radiate it back into the air, increasing the surface temperatures. Tree canopy and other vegetation exert a cooling infuence on the surrounding area. Land use decisions, resulting in the high concentration of impervious surfaces, coupled ith disparities in the distribution of tree cover, interact to make certain areas of the city much armer in summer months thus, more vulnerable to extreme heat events 3. This effect is termed the Urban Heat Island effect (UHI effect) , .

igure sho s the surface temperatures in Detroit. 6 This map demonstrates the temperature variation throughout the city, the dispersed character of the UHIs, and highlights ho different surface materials absorb and reradiate solar energy. or example, roads tend to be hotter and therefore create visible lines on the map. The average annual temperatures of HI areas of Detroit can be . . armer than surrounding areas . Ho ever, vegetation cover reduces surface and air temperatures through evapotranspiration and shading, thereby decreasing vulnerability to extreme heat8 . To analy e local variations in HI effect e obtained land cover data from the nited States Geological Survey Global isuali ation ie er Glo is available at usgs.glovis.gov.

As the above maps demonstrate, impervious surface and lo tree canopy correspond to location of HIs ithin the city. To understand the relative importance of impervious surface and tree canopy, e calculated the percent of each census block group’s land cover covered by impervious surface and by tree canopy. Based on research by Coseo and Larsen, areas of impervious surface ere eighted by a factor of and areas of tree canopy ere eighted by a factor of - .9 The t o layers ere combined to create cumulative heat exposure scores at the block group level, as sho n in igure .

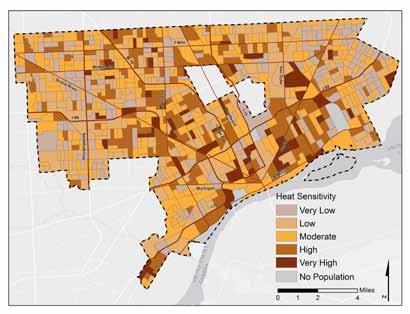

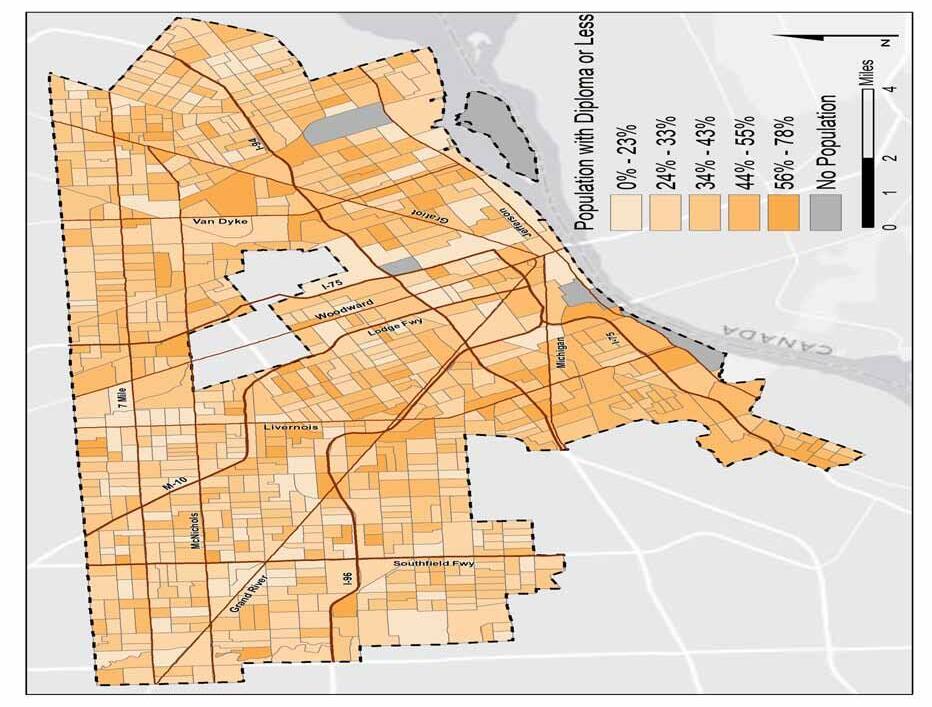

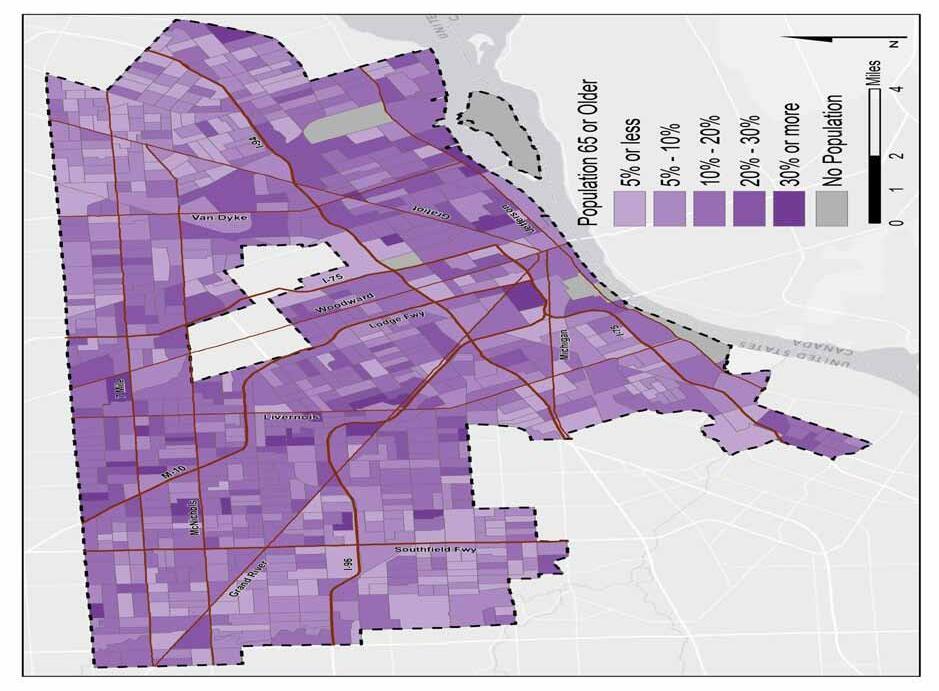

Our analysis used four primary factors that contribute to increased risk of heat-related illness: residents and older, lo er educational attainment, poverty and household access to a vehicle. These four demographic variables measure human sensitivity to extreme heat. The literature used to derive these variables revealed the importance of neighborhood socio-economic positions, or group-level factors, in predicting risk of illness, independent of the infuence of the same variable measured at the individual level10. or this reason, and due to the diffculty in obtaining individual-level income or health data, e conducted our vulnerability analysis at the census block group level.

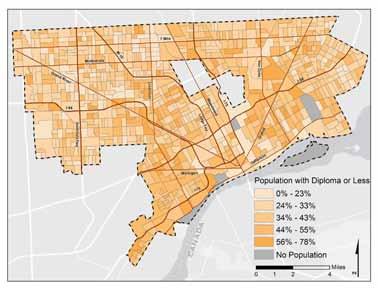

T o indicators of community level socioeconomic status are associated ith increased heat-related mortality these indicators include the percentage of the population ithout a high school diploma, and the percentage of the population living in poverty.11 Research demonstrates a link bet een lo educational attainment and poor health.12 oreover, specifc studies of heat-related deaths in cities across the .S. fnd greater mortality rates among individuals ith lo er levels of education because educational attainment is often a measure of uality of life, occupation and living conditions.13 Using U.S. Census data obtained from Social Explorer, e calculated the percentage of each census block group holding no more than a high school diploma, as sho n in igure .

ap

American Community Survey - S

ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate

Source: American Community Survey - S Census ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

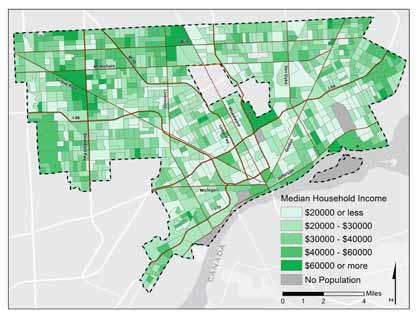

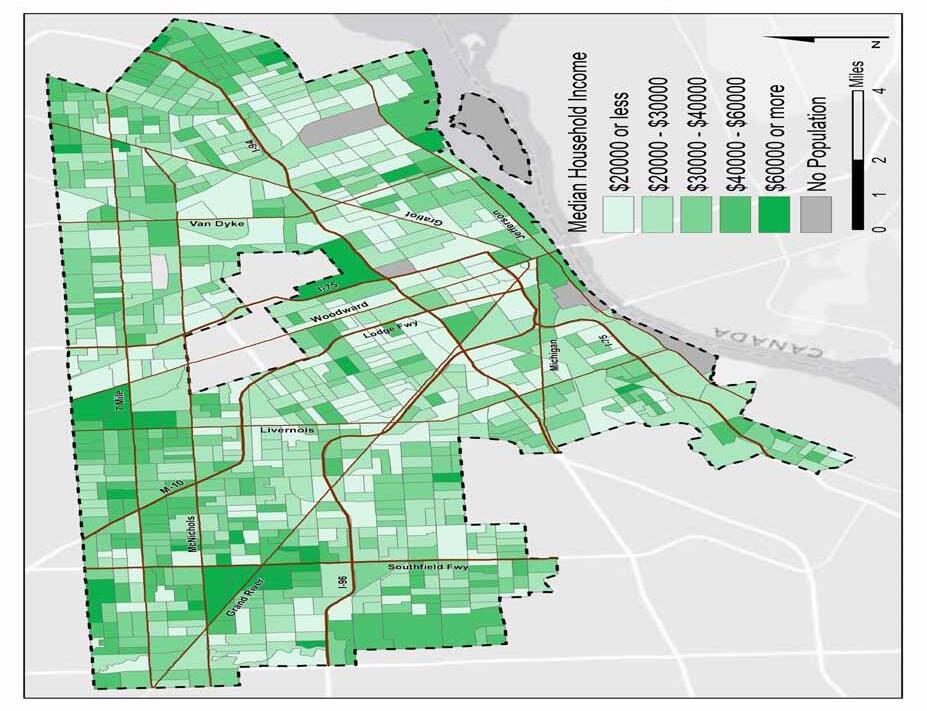

Similarly, ealth mitigates the risk of heatrelated death by increasing access to air conditioning and other opportunities to avoid heat. n an individual level, there is little doubt that poverty leads to ill health, and community levels of poverty have also been demonstrated to play a role in heat-related mortality. Therefore, using census data obtained from Social Explorer, e calculated the median income of each census block group and stratifed the census block groups by income level in order to identify the poorest neighborhoods, sho n in igure .

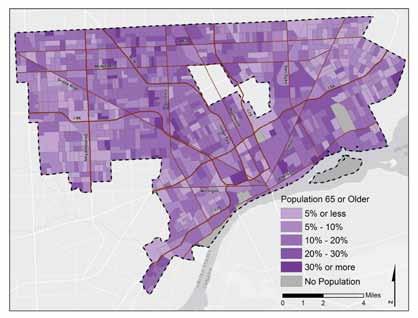

A signifcant body of literature has found old age to be a prominent vulnerability factor during extreme heat, effecting both hospital admission rates and mortality. Since e could not access individual-level age data by household, e calculated the percentage of each census block group over age , as sho n in igure .

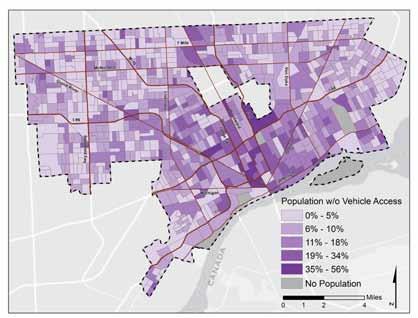

inally, e included household access to vehicles as a contributing factor in the sensitivity index, since individuals ithout a vehicle are less able to drive to an airconditioned cooling center or alternative refuge during extreme heat events. sing census data, e mapped the percentage of households in each census block group that

had no vehicle access, as sho n in igure

In order to understand the cumulative sensitivity, e calculated a sensitivity index. To do so, e converted the four variables to compatible scales so they could be combined to produce a single index. In order to normali e the variables, e computed the -scores for each individual variable by subtracting the mean of the sample from each block group’s score and then dividing the result by the standard deviation of the sample. This ensures that each of the rescaled variables has a mean of ero and a standard deviation of , allo ing them to be combined directly. Areas of high sensitivity to extreme heat ere geographically dispersed throughout the city, ith small clusters in the do nto n, south est, and east sides of the city. The four socioeconomic factors ere e ually eighted.

American Community Survey - S

ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate

Source: American Community Survey S Census ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

Source: SGS

is

ET American Community Survey US Census 2010 ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

To identify areas of vulnerability, e created an index to combine our exposure and sensitivity indices.

This vulnerability index identifes the areas of the city here concentrations of exposure and sensitivity create higher risk for residents. ased on this methodology, vulnerability is distributed fairly randomly ith notably lo er levels in the orth est portion of Detroit. In general, the most vulnerable census block groups are clustered roughly in the do nto n area and the least vulnerable are in the north est area of the city. ecause this is a relative index, the vulnerability index does not represent any sort of absolute risk. Rather, the index identifes the block groups that are more vulnerable in comparison to other block groups in the city.

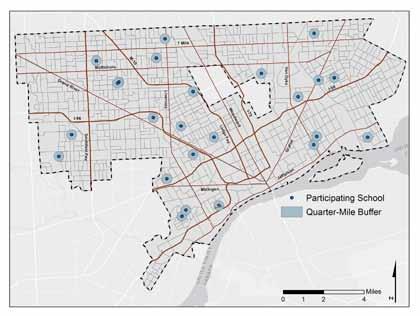

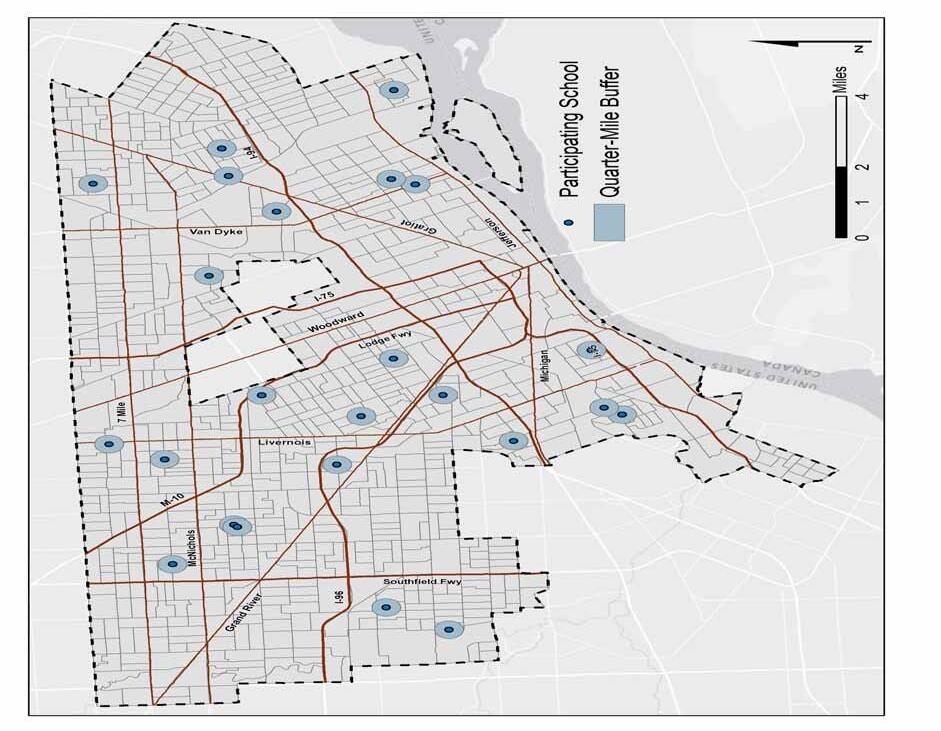

The City of Detroit opens facilities such as libraries and recreation centers to serve as cooling centers here residents can seek refuge during extreme heat events. To evaluate ho residents are served by Detroit’s cooling center net ork, e determined service areas. We used national orking safety standards to determine the appropriate range of cooling center service areas. The ccupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) has determined threshold limit values TL for external orking conditions. The TL s are designed to prevent body temperatures from exceeding . hen experiencing light to moderate exertion. They recommend that during heat events, each minute period of light activity should be matched by minutes of rest. Therefore, e used minutes of outdoor exposure, hile alking, in order to determine each service

area. or pedestrians, minutes translates into . miles, using an average speed of . mph16. We used the Buffer tool, a GIS function, to defne an appropriate alking distance. We found that . of Detroit’s land area is ithin a minute alk of a cooling station. Calculations of the population served by each cooling center reveal that roughly . of Detroit’s population is ithin a -minute alk of a cooling station.

We did not calculate automobile or transit service to cooling centers. While automobiles can often provide the most immediate source of relief, hether by air conditioning in the vehicle or uickest transport to a cooling center, percent of Detroit households do not o n a vehicle . Transit also offers an air-conditioned mode of travel, but service times and coverage are limited, an issue further exacerbated by recent spending cuts 18 .

Combining the cooling center service areas ith the vulnerability map allo ed us to determine hat percent of Detroit’s most vulnerable residents are ade uately served. igure sho s the alking service areas overlaid on the vulnerability index map. y selecting the top percent of most vulnerable census block groups, e calculated that only . percent of the most vulnerable residents are ithin a -minute alk of a cooling station. This service area captures only . percent of the city.

According to these fndings, the city’s offcial response to extreme heat events cooling centers is not suffciently addressing Detroit’s needs. Since cooling centers are co-located ith existing libraries and recreation centers, and are therefore likely to be a cost-effcient service, e ould need to conduct further cost-beneft analysis to determine a recommended relocation strategy. We can, ho ever, recommend opening additional cooling centers to serve more of Detroit’s vulnerable population, especially those reliant on alking.

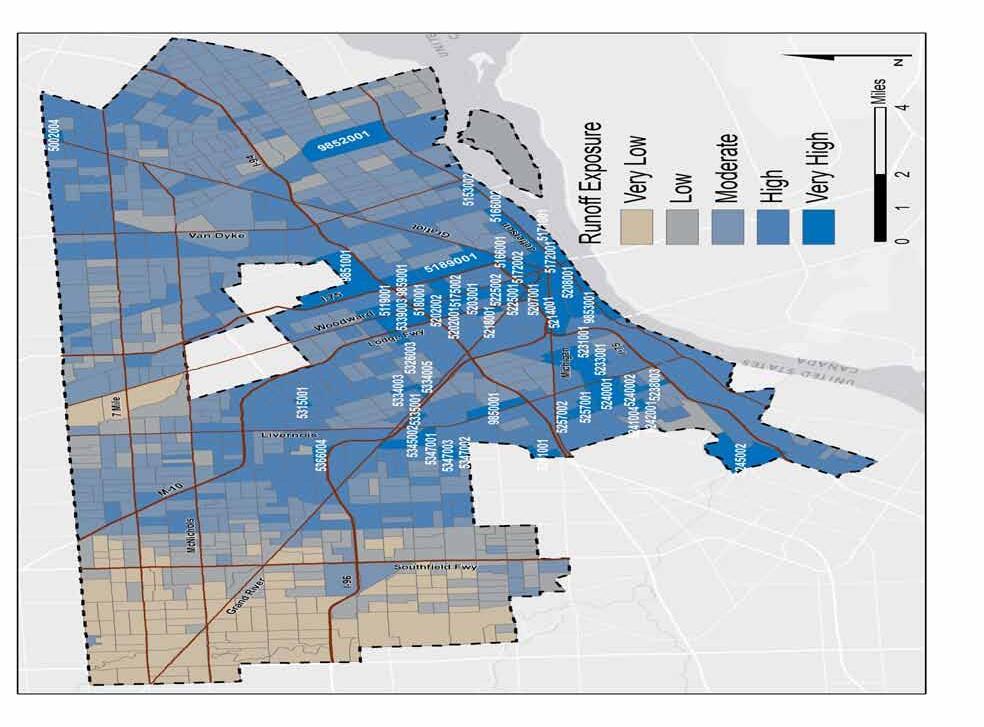

Compared to lo -lying coastal cities such as e ork or e rleans, Detroit is not at risk from sea level rise or hurricaneinduced fooding. either is it at risk for landslides of the type that can occur after heavy rainfalls in mountainous areas. Ho ever, the pro ected high volume of precipitation has the ability to over helm Detroit’s combined se er system and cause outfalls of untreated sanitary se age into the ater ays. At frst glance this appears to be a problem completely for the Detroit Water and Se erage Department DWSD . Ho ever, after further analysis, our land use decisions are linked to, and have signifcant impacts on, se er infrastructure.

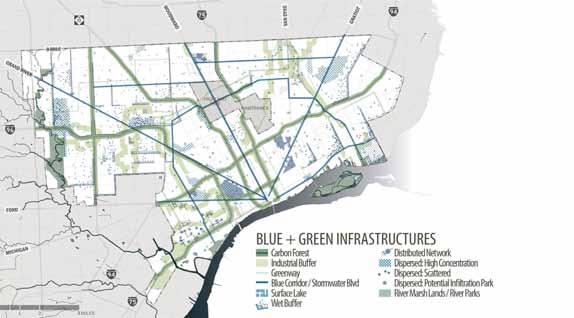

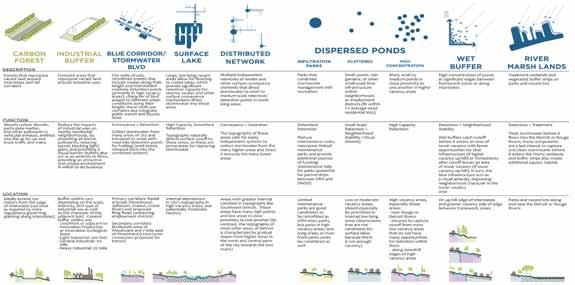

When the se er infrastructure cannot manage the storm ater runoff, excess stormater and se age is directly discarded into the Rouge and Detroit Rivers. ecause the city is serviced by a combined se er and aste ater system, these discharges also contain untreated sanitary se age. In , Detroit discharged billion gallons of untreated se age into the Great Lakes system, making it one of the largest sources of pollution in the Great Lakes system19 While DWSD has embarked on signifcant grey infrastructure projects to address the discharge issue, the DWSD has not pursued green infrastructure projects that seek to deal ith onsite storm ater before it reaches pipes. or this reason, our vulnerability assessment has focused on the burden of runoff into the se er system as the main exposure to fooding.

This vulnerability assessment only considered the exposure element of se er system vulnerability, because e did not have information on the se ersheds’ sensitivity factors. Se ershed information is important to obtain for future research and perhaps represents an important future

:Detroit Land Cover Type

partnership for the DCAC and DWSD. Ho ever, exposure alone provides an excellent idea of hat relative levels of burden ill be imposed on the system by increased rain events and ho these vary across the city by se er district.

Source: SGS Glo is LandSat ET American Community Survey S Census ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

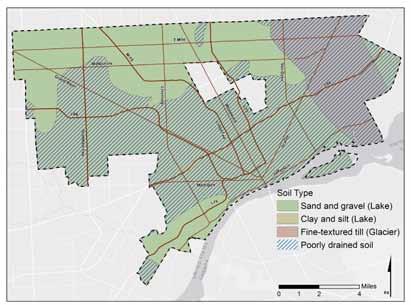

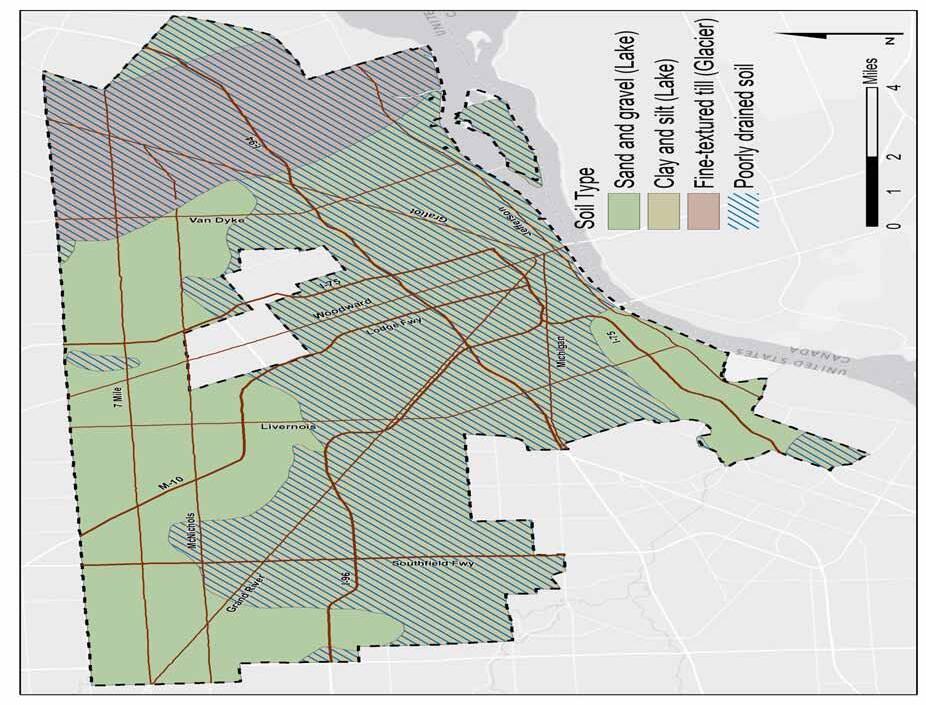

igure : nderlying Soil Type and Soil Drainage

Source: Michigan Geographic Data Library, Michigan Quarternary Geology ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

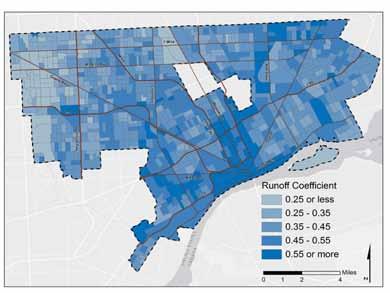

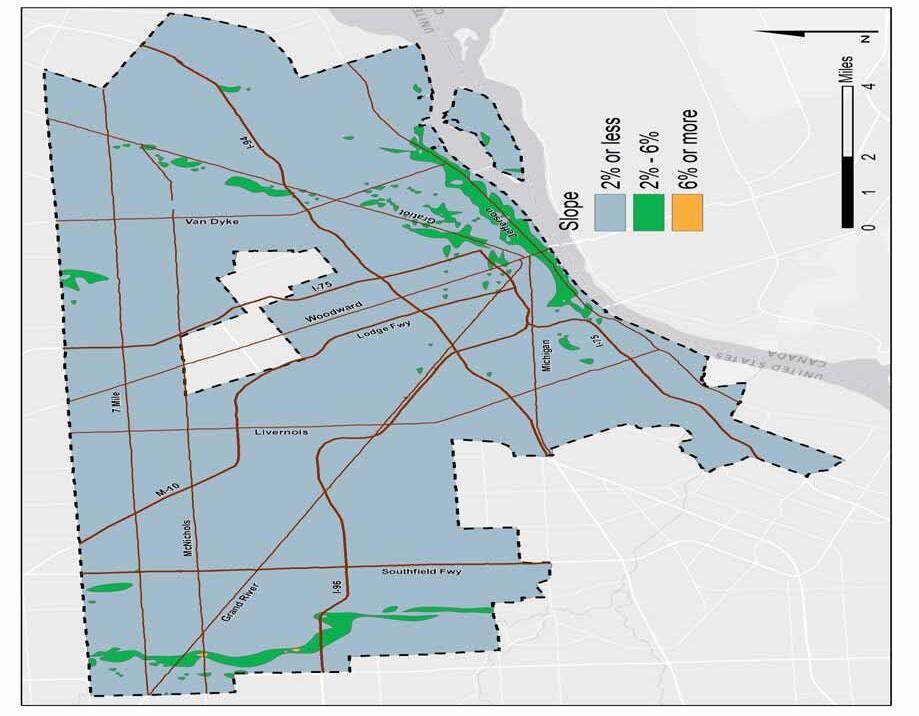

In this instance, exposure is the volume of the runoff from the surface that fo s into the se er system. The manner in hich rain ater moves through the combined storm ater sanity se er system is highly dependent upon here it falls. Impervious surfaces by their nature do not readily absorb ater, and instead channel ater into the se er infrastructure. To uantify this exposure, called runoff burden, e considered three factors: land cover type, soil drainage type, and slope. The combination of these factors creates a runoff coeffcient. This is a score ranging bet een ero and one that represents the amount of runoff that is generated at a particular site. Zero represents a site that generates no runoff and deals ith all rain ater on site hile a value of one represents a site that does not retain any ater on site.

As ith the assessment of heat, e utili ed a land cover map obtained from the nited States Geological Survey Global isuali ation ie er Glo is available at usgs.glovis.gov. Land cover as categori ed into one of four categories: tree canopy, herbaceous cover, bare ground, or impervious surface. Areas covered by tree canopy contributed the least to runoff and areas covered ith impervious surface contributed the most. While grassy and sparsely vegetated areas also have a lo er runoff coeffcient than tree canopy, bare ground and impervious surfaces contribute heavily ith respect to runoff coeffcients. These landcover runoff values are based upon standardi ed engineering tables.

Soil type impacts runoff volumes. In Detroit, three major soil types dominate. These different soil types have different percolation rates. oorly drained soils the clays, silts, and fne matter are unable to remove ater uickly, thus giving runoff more opportunity to go some here else. Therefore, poorly drained soils have higher coeffcients than ell drained sandy soils that uickly absorb ater. Silt and clay soils are found to ards the river and in the east side of the city. Sandy soil, that drains uickly and contributes less to runoff burden, is found primarily in the north and north est areas of the city.

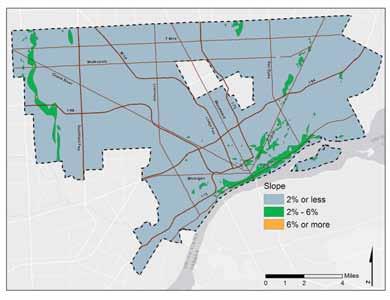

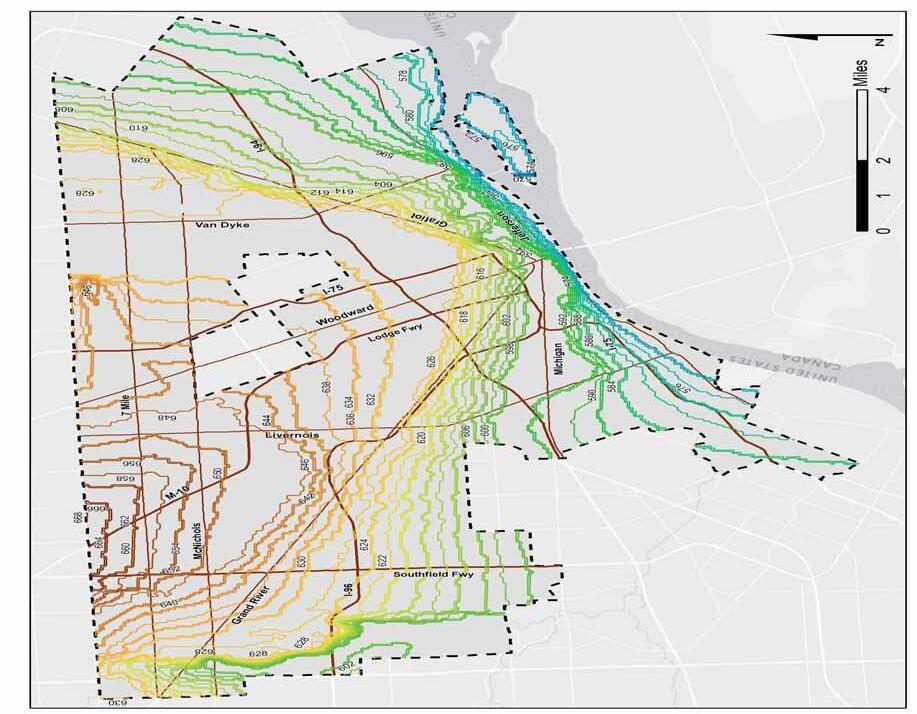

Slope is another factor that impacts runoff volumes. Areas ith higher slopes shed ater more uickly. Detroit has relatively little elevation change and therefore minimal slopes. We categori ed the minimal slopes into three distinct categories: less than 2 percent, 2 to 6 percent, and greater than six percent. Only a fe small areas of the city near the Rouge River in the north est contain slopes of greater than six percent. The map illustrates ho Detroit is a fat city ith a gently sloping topography. The highest elevation points occur near - and Eight ile Road. rom these high point, there it a gently slope south ard to ard do nto n and the Detroit River. ost of the city then falls in an area of less than 2 percent slope.

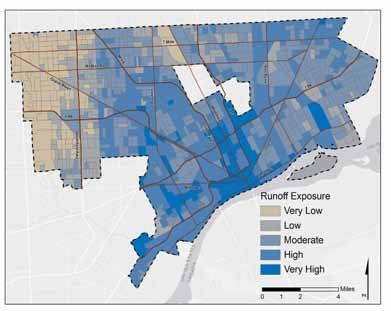

We generated uni ue land cover combinations based on the three factors land cover, soil and slope and determined each combination’s relative abundance ithin each census block group. ased on the relative abundance and associated runoff coeffcient for each combination, e created an aggregate runoff coeffcient for the each census block group. The highest scores (areas of greatest runoff concern) tended to cluster around the do nto n core and in areas of ma or impervious cover.

Michigan Geographic Data Library, ichigan Digital Elevation odel ap repared y: niversity of ichigan

Source: ichigan Geographic Data Library ichigan Digital Elevation odel Glo is Landsat ET S Census ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

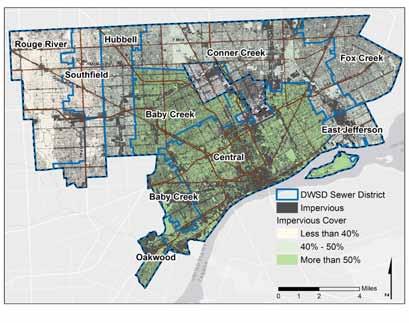

Ho ever, block groups do not exist in isolation. Each block group’s se ershed is part of a larger se er district. Therefore, it is also useful to analy e the system at the se er district level.

or instance, if a block group contributes a great deal to runoff burden, but the surrounding block groups do not, then the se er district ill be less likely to become overloaded. Ho ever, if that block group is surrounded by block groups that generate large volumes of runoff, then the reference block group is more likely to contribute to fooding.

There are nine se ersheds ithin the city. Impervious cover is the most predictive variable, due to its si eable impact on runoff coeffcients. ormali ing by the si e of the individual se er districts, e found that the percentage of land cover that is impervious ithin each se er district varies idely. The percentage that exists as impervious surface ranges mainly bet een and percent, ith only the Rouge River district in the north est falling ell outside the range . We added the se ershed- ide value to the individual block group score in an effort to understand the cumulative impact. In general, the most vulnerable areas cluster around the do nto n core and around large areas of impervious cover note SW Detroit . This assessment illustrates the importance of prioriti ing on-site storm ater management in se ersheds ith higher levels of impervious surfaces.

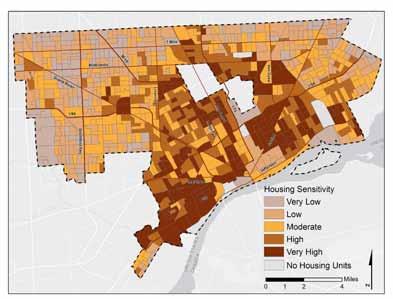

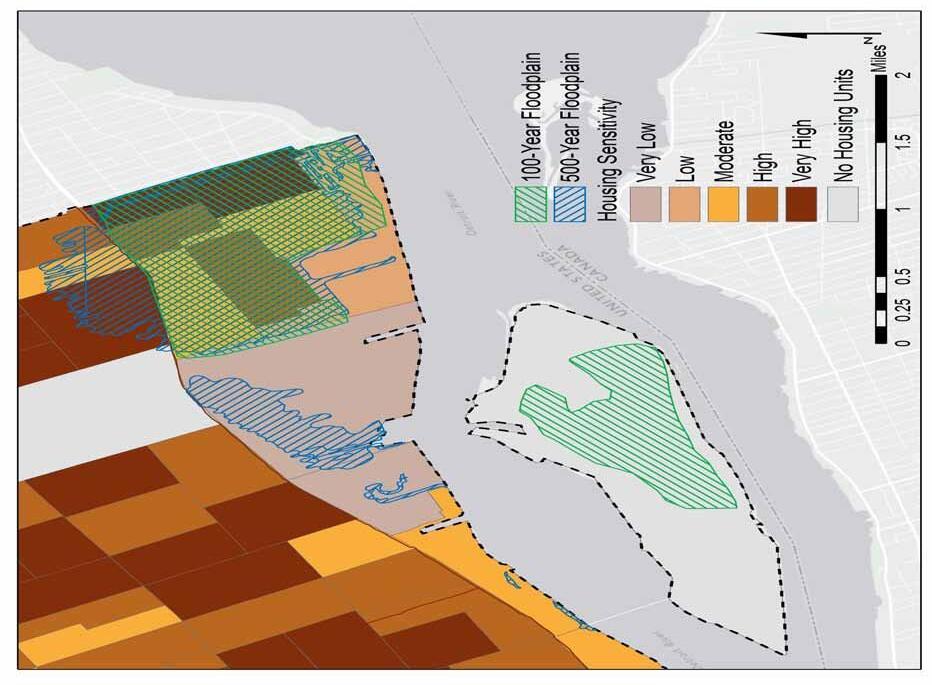

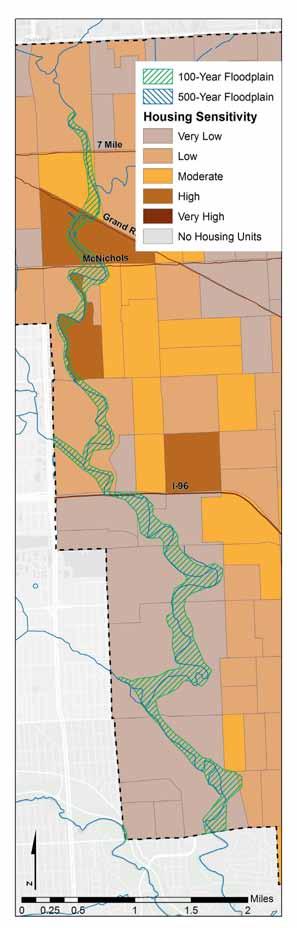

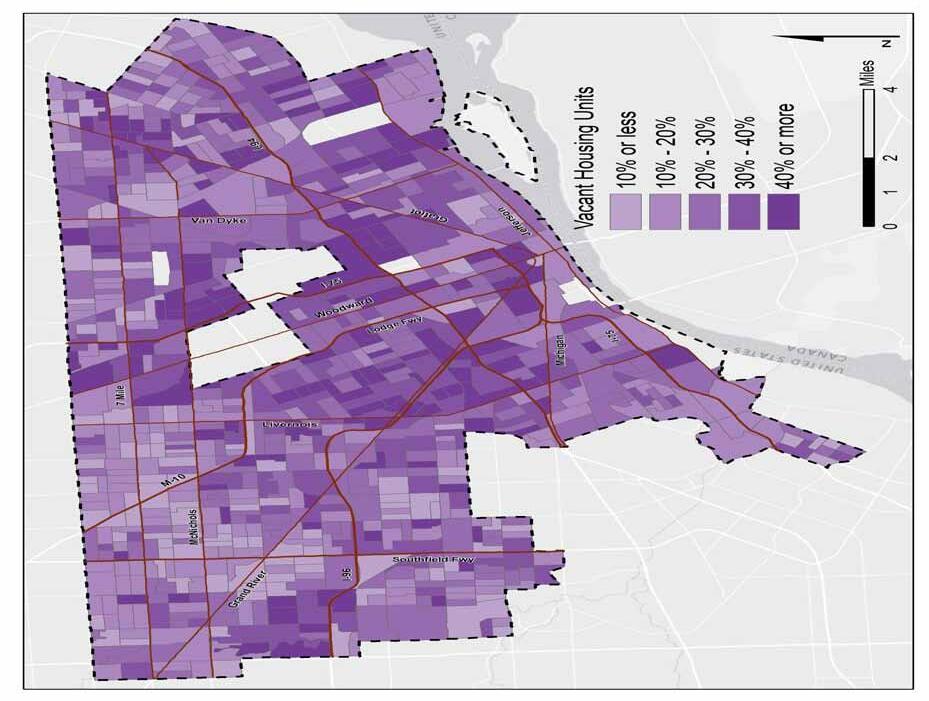

lood risk also exists at the household level. There are certain areas of the city that are more prone to the effects of fooding, and certain citi ens ould be impacted disproportionately. The household level analysis comprises the second component of our vulnerability assessment. The household food risk exposure correlates highly to the household’s relative location to foodplains. Household food risk sensitivity refers to ho ell a household is prepared for or able to respond to that food exposure.

ur exposure assessment used E A’s maps of -year and -year food plains to determine hether a household as in an area of food exposure. E A uses the food plain maps to denote areas of special ha ard and risk in terms of fooding. The terminology of -

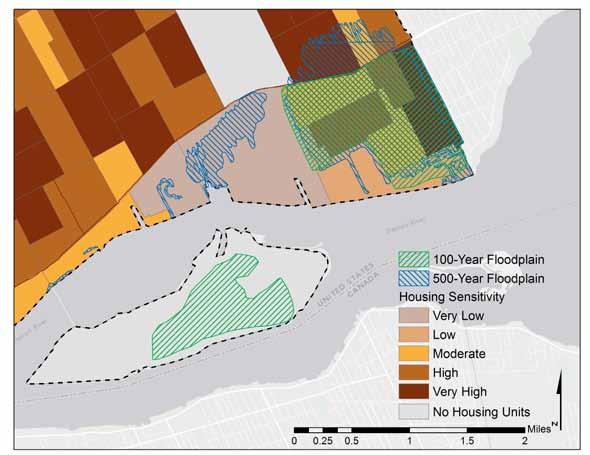

year and -year foods refers to the probability in a given year that is, an area in a -year food plain has a percent in probability of fooding in any given year. Ho ever, many cities are fnding that these designated areas are fooding ith increased fre uency. If this trend persists, the larger -year food plain may in effect become a more relevant area in addition to other lo -lying areas. oreover, areas along the Detroit River may be at increased risk in future years. As igure sho s, areas of food plain exposure are limited predominantly to t o geographic areas: one along the Rouge River in the est, and the other in the southeast alongside Grosse Pointe Park and across from, and on, Belle Isle.

Sensitivity to a given food exposure as determined by the age of the housing stock and the median household income. Homes built before used a more porous concrete material for basement construction. Water fo s easily and more rapidly into these foundations relative to foundations that ere constructed in later years. Additionally, homes that are older may be sensitive in other ays if residents have not had the fnancial resources to make signifcant upgrades. y incorporating median household income, e can distinguish older, ell-maintained homes from older, at-risk homes. Residents ith higher incomes are more likely to renovate their homes to prevent fooding or to repair food damage. Additionally, fooding that displaces residents from their homes ill have a disproportionate effect on lo -income households. These households may not be able to afford to miss ork or rent a hotel room.

This map of the older housing stock and median household income may also be useful for other DCAC Work Groups that target lo er-income housing

ap

igure : lood Risk Ha ard

Source: ichigan Geographic Data Library, Hydrology E A lood aps ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

igure : Household Sensitivity and lood otential

Source: American Community Survey - S Census ap repared y: niversity of ichigan Detroit Climate Capstone

: Household

and lood otential Source: American Community Survey - S

y observing the overlap of the food exposure areas and housing sensitivity, e can identify several block groups that are vulnerable to household fooding risk. We identifed t o areas of exposure concern. igure sho s the efferson-Chalmers area in the east alongside Grosse ointe ark, and igure sho s the area on the city’s est side near the Rouge River. nderlying the foodplain designation in these maps is a map of housing sensitivity using t o variables, median household income and the percent of the housing stock built before these variables ere analy ed at the block group level. This comparison is a relative measure, but it sho s that even ithin the small geographic extents of these t o maps, some census block groups tare more vulnerable than other nearby census block groups.

When examining the maps of heat vulnerability and system fooding vulnerability, there are clear similarities. Because large areas of impervious surfaces ith lo er areas of tree canopy are more vulnerable to both extreme heat and runoff burden, many of the same areas of the city appear in both vulnerability assessments. Ho ever, this also presents the possibility of strategically locating interventions that address both problems.

1. Great Lakes Integrated Science Assessment, Great Lakes Station Climatologies. http://glisa.msu.edu/ great_lakes_climate/climatologies.php

2. Altman, Peter, et al. Killer Summer Heat: Projected Death Toll from Rising Temperatures in America Due to Climate Change. Natural Resources De fense Council issue brief, May 2012. http://www. nrdc.org global arming killer-heat fles killer-sum mer-heat-report.pdf Accessed October 10, 2012.

3. Landsberg, H. (Ed.), 1981. The Urban Climate. Academic Press, New York.

4. Bornstein R. D. Observations of the urban heat island effect in New York City. Journal of Applied Meteorology. 7(1968):575-582.

5. Oke T. R. (1973) Review of Urban Climatology 1968-1973. W.M.O. Report No. 383, TN No. 134, 132 pp.

6. Van Hove, Michael, 2011. Satellite Band Thermal Image. City University of Hong Kong. Contact: vanhove@cityu.edu.hk

7. Great Lakes Integrated Science Assessment, Great Lakes Station Climatologies. http://glisa.msu.edu/ great_lakes_climate/climatologies.php

8. Serrano, SM Vicente, JM Cuadrat Prats, and Miguel A. Saz Sánchez. “Topography and vegetation cover infuence on urban heat island of arago a Spain . Fifth International Conference on Urban Climate 1-5 September, d , oland: proceedings. ol. . Department of Meteorology and Climatology Faculty of Geographical Sciences niversity of d , .

9. Coseo, Paul & Larissa Larsen (2012). How Factors of Land Cover, uilding Confguration, and Ad acent Heat Sources and Sinks Differentially Contribute to Urban Heat Islands in Eight Chicago Neighbor hoods. Unpublished Manscript.

10. Diez Roux AV. The study of group-level factors in epidemiology: rethinking variables, study designs, and analytical approaches. Epidemiology Review. 26 (2004):104–111; Harlan, S. L., Brazil, A.J., Prashad, L.*, Stefanov, W. & Larsen, L. (2006) “Neighborhood Microclimates and Vulnerability to Heat Stress , Social Science and edicine. 63 (2006): 2847-2863; Reid CE, et al. Mapping community determinants of heat vulnerability. Environ Health Perspectives. 117(2009):1730–1736.

11. Smoyer KE. Putting risk in its place: methodological considerations for investigating extreme event health risk. Social Science and Medicine. 47: 11 (1998):1809–1824.

12. Curriero FC, Heiner KS, Samet JM, et al. Tem perature and mortality in 11 cities of the eastern United States. American Journal of Epidemiology. 155 (2002):80–7.

13. Brunner E. Commentary: education, education, education. International Journal of Epidemiology. : . edina-Ramon , anobetti

A, Cavanagh DP, Schwartz J. Extreme temperatures and mortality: assessing effect modifcation by personal characteristics and specifc cause of death in a multi-city case-only analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (2006):1331–1336.

14. O’Neill MS, Jackman DK, Wyman M, Manarolla X, Gronlund CJ, Brown DG, et al. U.S. local action on heat and health: are we prepared for climate change? Interna tional Journal of Public Health. 55:2 (2010):105–112; hipps, Shelley. The impact of poverty on health. ro ceedings of the CPHI National Roundtable on Poverty and Health (2002).

15. Curriero FC, Heiner KS, Samet JM, et al. Temperature and mortality in 11 cities of the eastern United States. American Journal of Epidemiology 155 (2002):80–87.; Knowlton K, Rotkin-Ellman M, King G, Margolis HG, Smith D, Solomon G, et al. The 2006 California heat wave: impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environmental Health Perspectives. 117 (2009):61–67.; Semenza JC, McCullough JE, Flanders D, McGeehin MA, Lumpkin JR. Excess hospital admissions during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 16:4 (1999):269–277.; Conti S, Meli P, Minelli G, Solimini R, Toccaceli V, Vichi M, et al. Epidemiologic study of mortality during the summer 2003 heat wave in Italy. Environmental Research. 2005; 98:3 (2005):390–399.; Fouillet A, Rey G, Laurent F, Pavillon G, Bellec S, Ghihenneuc-Jouyaux C, et al. Excess mortality related to the August 2003 heat wave in France International Archives of Occupational Environmental Health. 80(2006): 16-24.; Hutter HP, Moshammer H, Wallner P, Leitner B, Kundi M. Heatwaves in Vienna: effects on mortality. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 119:7(2007): 223–227.Naughton MP, Henderson A, Mirabelli MC, Kaiser R, Wilhelm JL, Kieszak SM, et al. Heat-related mortality during a 1999 heat wave in Chicago. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 22:4(2002):221–227.; Stafoggia M, Forastiere F, Agostini D, Caranci N, de’Donato F, Demaria M, et al. Factors affecting inhospital heat-related mortality: a multi-city case-cross over analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 62:3(2008):209–215.

16. Levine R, Norenzayan, A. “The Pace of Life in Countries . ournal of Cross-Cultural sychology. 30:2(1999):178–205.

17. U.S. Census Bureau; American Community Survey, 2006-2010, Detailed Tables; generated by Social Ex plore; www.socialexplorer.com; November 15, 2012

18. Kleinfelter, Quinn. Commuters Suffer As Detroit Cuts Bus Service. National Public Radio Online, March 2012. http://www.npr.org/2012/03/08/148225070/commuterssuffer-as-detroit-cuts-bus-service. Accessed November 10, 2012.

19. Lyandres, Olga, and L. C. Welch. “Reducing Combined Se er verfo s in the Great Lakes: Why Investing in Infrastructure is Critical to Improving Water uality. Alli ance for the Great Lakes. (19 June 2012).

This chapter discusses each Work Group in a detailed fashion. This section outlines specifc Detroit-related issues pertaining to each Work Group, as well as a list of possible guidance strategies and indicators. As mentioned, these guidance strategies and indicators serve as a potential foundation for future action. Lastly, each Work Group section provides a list of resources; these resources cite works used in our analysis and provide a basis for further research.

The following encompass the seven Work Groups discussed in this chapter:

• SI ESSES I STIT TI S

• C IT LIC HEALTH I ACTS

• E ERG

• H ES EIGH RH DS

• AR S, LIC S ACE WATER I RASTR CT RE

• S LID WASTE

• TRA S RTATI

Because of the varying size and scope of Detroit’s businesses and institutions, the defnition of vulnerability as it pertains to these organizations) focuses on risk. Climate change often intensifes the risks normally associated with business operations, such as market, fnancial and supply-chain risk. Therefore businesses and institutions must address vulnerability and implement adaptation strategies, not just because of reputational gains, but because climate change can drastically affect consumption, operations and logistics. The following chart illustrates climate change’s impact on risk factors for local businesses and institutions:

The two primary guidance strategies pertaining to Businesses and Institutions include:

1. Review and improve current business practices

2. Create sustainable green markets

Reviewing and improving current business practices ranks as a primary focus because it’s effects are immediate and easily transformed. In order to make gains in eco-effciency, frms and organizations must evaluate and catalogue

This section focuses on guidance strategies for Businesses and Institutions. These guidance strategies serve as an aid for the Work Group chair and members as they address vulnerabilities and risk factors associated with climate change. Moreover, these guidance strategies engage a wide range of businesses and institutions ranging from grass roots organizations and “momand-pop stores to large conglomerates. This section provides options and avenues for Work Group members to explore ideas in an effort to mitigate the impact of climate change. In addition, this section outlines a few actions that will ensure the long-term sustainability of the project.

ongoing practices. Upon the completion of this internal evaluation, frms and organi ations can institute green programs. This strategy targets a broad array of frms and organizations, ranging from large-scale manufacturers to momand-pop retail stores and restaurants.

Secondly, creating sustainable green markets is crucial to the long-term sustainability of this Work Group. This strategy focuses on policy reform, regulatory action, capital attraction and capital investment. This guidance strategy focuses on the review and update of current environmental policy in order to determine areas of opportunity for capital investment. In addition, this strategy focuses on leveraging local incubators and accelerators as key assets in attracting venture capital and seed funding. The combination of these two guidance strategies address current vulnerabilities and build the foundation for future progress.

This guidance strategy focuses on engaging current market movers within Detroit, as well as providing the foundation for future climate adaptation efforts. This section discusses potential actions and programs that ill enhance current systems. Moreover, the indicators provide a framework for measuring the success of each action.

The following actions provide the foundation for the frst guidance strategy:

1. Identify market movers and environment-oriented organizations

2. Engage and contact businesses and organizations

3. Partner with colleges and universities

4. Develop website for businesses and institutions to learn about green practices

5. Formulate and distribute “Green checklist and survey for broad range of businesses

6. Create and distribute ‘preparedness’ checklist for climate emergencies

7. Leverage checklist and survey data for Green Certifcation program

The frst three actions focus on building a strong coalition around climate action. By identifying and engaging key organizations and institutions, this Work Group can move forward in a cohesive, sustained fashion. The fourth action step builds upon the community engagement process by leveraging technology. ore specifcally, an internet presence provides a platform for awareness, education and consensus building with regard to businesses, institutions and climate action.

Actions fve and six motivate businesses and institutions to analyze existing practices. Step fve deals specifcally ith outlining a guide for organi ations to refect upon current behaviors upon completion of this checklist and survey process, companies will have a heightened

roduce supply goods or services that result in: generating and storing renewable energy, recycling existing materials, energy effcient product manufacturing, distribution, construction, installation, and maintenance, education, compliance, and awareness, and natural and sustainable product manufacturing

Vulnerable aspects of organizations that are exacerbated by climate change; Factors of production and capital fo s are infuenced dramatically by extreme weather events and changing climate conditions

Source: By Michigan Municipal League

sense of awareness with regard to company practices and climate action. Step six focuses on extreme weather events and the preparedness of businesses and institutions. As the propensity for extreme weather events increases, organizations must prepare for these events by developing thorough game plans.

The last action deals specifcally ith leveraging data compiled through steps fve and six in order to create an independent agency. This agency would monitor businesses and institutions in their pursuit of green practices and adaptation policies. In some examples, cities created an independent entity that monitors these business practices and rewards environmentally conscious organizations

ith specifc certifcations. The primary goal of this type of program focuses on the idea of creating a strong social contract between the organizations and the community.

As mentioned, the actions for the frst guidance strategy re uires indicators — these indicators serve as metrics with which we can measure success. Some key indicators for the frst guidance strategy are listed below:

1. Number of program participants

2. Website hits and social media presence

3. Receipt of grant money and philanthropic donations

4. Presence of coalition in community

The frst indicator measures the number of program participants, especially with regard to businesses partaking in the checklist process for existing practices and climate preparedness. Although this indicator is basic in nature, it provides a good sense of momentum associated with the Work Group’s efforts.

The second indicator resembles the frst, as it uantifes activity related to the Work Group’s internet presence. Similarly to the frst indicator, an increase in unique visitors to the Work Group’s internet platforms indicate an increase in community interest.

The third and fourth indicators deal with the Work Group’s ability to generate capital and infuence. The receipt of grant funding and philanthropic donations allows for greater investment into the Work Group’s efforts, as well as recognition amongst community members. In addition to funding, the DCAC’s presence within the community further indicates the success of the Work Group’s efforts. Measuring the Work Group’s presence within the community may simply include the DCAC’s ability to meet with City offcials and other leaders ith regard to business development and land use decisions.

AS THE PROPENSITY FOR EXTREME WEATHER EVENTS INCREASES, RGA I ATI S ST RE ARE FOR THESE EVENTS BY DEVELOPING TH R GH GA E LA S.

The guidance strategy centers on the identifcation and pursuit of market opportunities pertaining to green ventures. This guidance strategy focuses on a two-prong approach. The two prongs of this guidance strategy include:

1. Implement “Green rocurement process

2. Attract green social ventures and promote entrepreneurship

The frst prong deals specifcally ith procurement. Procurement processes refer to rules and regulations pertaining to the acquiring of goods and services. Typically, procurement processes focus on the manufacturing and distribution components of the supply-chain. A prime example of a local green procurement process involves Detroit Diesel’s voluntary participation with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in order to improve energy effciency. Detroit Diesel’s initial investment into property, equipment and manufacturing processes led to long-term gains. The company is currently a market leader in green manufacturing and continually receives recognition for their efforts.

Implementing green procurement practices involves conducting a Strengths/Weaknesses/ Opportunities/Threats (SWOT) analysis and determining the key market opportunities. The identifcation of these market opportunities is crucial with regard to the pursuit of policy reform as well as the encouragement of green procurement.

The following indicators pertain to green procurement:

1. Identify a market opportunities with regard to green procurement

2. Complete independent study on economic impact of green procurement implementation

3. Complete study describing capital requirement for green procurement process

The frst step refers to the necessary analysis required for identifying market opportunities and outlining potential strategies for implementation. Although this indicator is not measured quantitatively, it requires thorough discussion and continual engagement. Once market opportunities are identifed, the second indicator serves to support the pursuit of such opportunities. An economic and fscal impact study informs whether the pursuit of such market opportunities results in a positive outcomes for local employment. Such outcomes are often a key selling point with regard to receiving funding, incentives and political support. Lastly, the third indicator refers to capital requirements necessary for green procurement. Studies explaining the costs and benefts of green procurement aim to further encourage the involvement of the business community.

Similarly to the frst strategy, the second strategy — attracting green social ventures and promoting social entrepreneurship — employs a t o-prong approach. The frst prong focuses on attracting green venture capital groups. Organizations such as the Green Garage already exist within Detroit in order to foster incubation. This particular strategy seeks to attract capital in order to aid in the launch and scaling of these businesses.

Source: By Kevin.Ward

The second prong relates to the establishment of social entrepreneurship programs within Detroit. Through leveraging partnerships with institutions of higher learning and local businesses, the Work Group can create an environment that promotes talent attraction and development.

The following indicators pertain to attraction of green venture capital and promotion of social entrepreneurship:

1. Monitor total venture capital investment

2. Measure number of environmentallyoriented start-ups

3. Monitor venture-backed jobs in Detroit

4. Ensure ventures stay in Detroit and do not relocate

The frst three indicators provide a simple, effective measure with regard to the attraction and sustainability of venture capital. The Work Group can identify venture capital groups investing in green business by the number of groups that have already invested in green ventures (or in the process of). Moreover, the number of start-ups and jobs associated with these green ventures provides a way in which the Work Group can measure the sustainability of these pursuits.

Lastly, the creation of a sustainable, fourishing green economy must focus on the retention of green ventures. By collaborating with start-ups and economic development agencies, the Work Group can create an environment conducive to the long-term success of the green economy. Examples of such collaboration include creating a network for green businesses within Detroit, as well as streamlining regulatory processes for green businesses.

Bizdom. <bizdom.com>

Bizdom is an entrepreneurship accelerator that helps entrepreneurs launch, fund, and grow innovative, tech-based startups in Detroit and Cleveland.

Detroit Creative Corridor Center. <detroitcreativecorridorcenter.com>

The Detroit Creative Corridor Center is designed to support the growth of Detroit’s creative economy by delivering business acceleration and attraction services and developing signature programming tailored specifcally to creative professionals’ needs.

Detroit Diesel. May 6 2009. “Detroit Diesel Launches e Green Initiatives. http: . demanddetroit.com/pdf/press/pr-2009-05-06a. pdf>

Detroit Venture Partners. <detroitventurepartners.com>

Detroit-based venture capital frm that invests in early-stage technology companies.

Green Garage Detroit. <greengaragedetroit. com>

Mid-town based business enterprise that is committed to the sustainability of Detroit.

Greening of Detroit. <greeningofdetroit.com>

The Greening of Detroit is a c not for proft organi ation established in to guide and inspire the reforestation of Detroit. In 2006, a new vision was established, expanding The Greening’s mission to guide and inspire others to create a ‘greener’ Detroit through planting and educational programs environmental leadership, advocacy, and by building community capacity.

United Kingdom Climate Impact Programme. Climate Adaptation Wi ard. http: .ukcip. org.uk/wizard/>

Public health works to prevent disease, injury and death, and promote well being for individuals and communities. Because the effects of climate change will worsen many existing health problems, and create potential ne ones, the feld of public health is orking to identify factors that make people more sensitive to these negative effects.