RAÍCES Roots

From mountain man Isaac Slover to Josefa and Kit Carson, and the enduring legacy of La Hacienda de los Martínez, Raíces uncovers the stories that shaped Northern New Mexico.

Josefa Carson: A quiet force in Taos’ history

La Hacienda de los Martinez de Taos

A living historical testament in time and space

HISTORY IS NOT ONLY FOUND IN DATES ETCHED IN TEXTBOOKS OR IN MONUMENTS WEATHERED BY TIME. It lives in the voices of the people who came before us — in their homes, their hardships and their hopes.

This year’s Raíces, part of the Taos News’ annual Tradiciones series, takes us deeper into those stories. We revisit the fur-trade frontier through the life of Isaac Slover, a nearly forgotten mountain man whose path intertwined with Taos at a pivotal moment. We look again at Kit Carson, whose complex legacy still shapes how we talk about history today. And beside him stands Josefa Jaramillo Carson, whose quiet strength carried her family and whose compassion continues to inspire. We also explore the enduring significance of La Hacienda de los Martínez, a living testament to the resilience of Hispano families in El Norte.

These stories remind us that Taos’ history is not static; it breathes through the lives of ordinary and extraordinary people alike. We hope Raíces stirs you to listen more closely to the voices of the past — and perhaps to discover the roots of your own story here in Northern New Mexico.

Ellen Miller-Goins, magazine editor

Kit Carson: Hero, villain or both? Carson’s story reveals the legends we celebrate … and the truths we must face

Isaac Slover and the Taos trappers

A hidden figure of the fur trade frontier

Josefa Carson A quiet force in Taos’ history

Kit Carson Electric Cooperative (KCEC) stands as a source of local pride—rooted in our land and committed to our community. In summer 2022, we made history by becoming one of the first cooperatives in the continental U.S. to achieve 100% daytime energy from our own solar arrays.

In 2025, we brought two major clean energy projects online: Shallow Basket solar and storage facility, and Amalia II—a new solar array paired with battery storage—which increased our capacity dramatically to 190.75 MW of solar and 25 MW of battery storage.

KCEC is leading the way in innovative, resilient, next-generation energy for northern New Mexico

Photo:

Isaac Slover and the Taos trappers

IN THE

A hidden figure of the fur trade frontier

BY ELLEN MILLER-GOINS

early decades of the 19th century, before railroads snaked across the landscape and before the American flag flew over the Southwest, the mountains and canyons of Northern New Mexico beckoned to trappers. These mountain men helped open the region — physically, economically and culturally — through their pursuit of one thing: the beaver. Among them, one figure stands out for both his perseverance and his little-known but far-reaching impact: Isaac Slover.

Born in 1777 near Fort Pitt, Pennsylvania, Slover’s early life foreshadowed a lifetime of frontier wanderings. His father, a former captive of the Miami and Shawnee tribes, raised Slover with a deep awareness of the tensions between Native and settler worlds. After his wife died in 1816, Slover, by then a father of seven, took five of his children and headed west into Arkansas Territory, eventually settling near present-day Salina, Oklahoma. The area, embroiled in Osage-Cherokee conflict, soon became untenable for white settlers like

Slover, and the federal government pushed him off the land.

That loss set Slover on the trail with the 1821 Glenn-Fowler Expedition — one of the first American trapping parties permitted into Mexican New Mexico following the country’s independence from Spain. While American trappers often found themselves in jail under Spanish rule, Mexico’s more relaxed policies opened the door for Americans like Slover, who arrived in Taos in early 1822.

This image accompanies “Wayfaring Stranger With the Glenn-Fowler Expedition on the Great Plains (1821–1822),” Chapter 4 of “The Edge Rover: The Life and Times of Mountain Man Isaac Slover.” All chapter heading illustrations are by John Wilson of Austin, Texas.

FOR trappers, Taos was more than just a base of operations. It was a multiethnic frontier community that served as the unofficial capital of the mountain man’s world. Spanish, French, American, Genízaro and Indigenous pueblo peoples lived, traded and married in a vibrant, if uneasy, cultural melting pot. The annual Taos Trade Fair became the economic highlight of the region, where trappers exchanged beaver pelts for supplies and indulged in “Taos Lightning,” the local whiskey.

Tim Green, author of “The Edge Rover: The Life and Times of Mountain Man Isaac Slover,” describes Taos during this time as “a magnet for young, aspiring trappers and traders,” but also a cultural battleground where foreigners (or extranjeros) often clashed with local norms. Green, Slover’s direct descendant, paints his ancestor as a quiet but central player in this frontier drama.

“He is both witness to and denizen of multiple frontiers,” Green writes. “Just following his trail ... is an exploration of the American West.”

TRAPPING, TRADING & FAMILY

Slover’s trapping career took him across what is now New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and California. Along the way, he partnered with key figures like William Wolfskill, Ewing Young, and James Ohio Pattie. In the rugged canyons of the Gila and the Colorado River, he trapped beaver and hunted game, often under threat from Apache and Comanche warriors or Mexican authorities levying taxes on fur exports.

But it was in Taos where Slover laid down deeper roots. In 1823, he married María Barbara Aragon, a Genízara woman who had likely been born a Paiute captive and raised by a Taoseño family. Their marriage was emblematic of the complex cultural interweaving of the region—EuropeanAmerican trappers marrying Native or mixed-race women who served as cultural intermediaries, interpreters, and business partners. Maria, known affectionately as “Barbarita,” helped Slover navigate Taos society.

THE FALL of the FUR TRADE & A NEW FRONTIER

The beaver population in the Southwest began to decline in the 1830s, a victim of over-trapping and changing fashion trends as silk hats replaced beaver felt. But for men like Slover, the end of the fur trade didn’t mean the end of adventure. By 1843, Slover had relocated with his family to California via the Old Spanish Trail, leading a party that included Pope and others who would later become prominent settlers in Napa and San Bernardino.

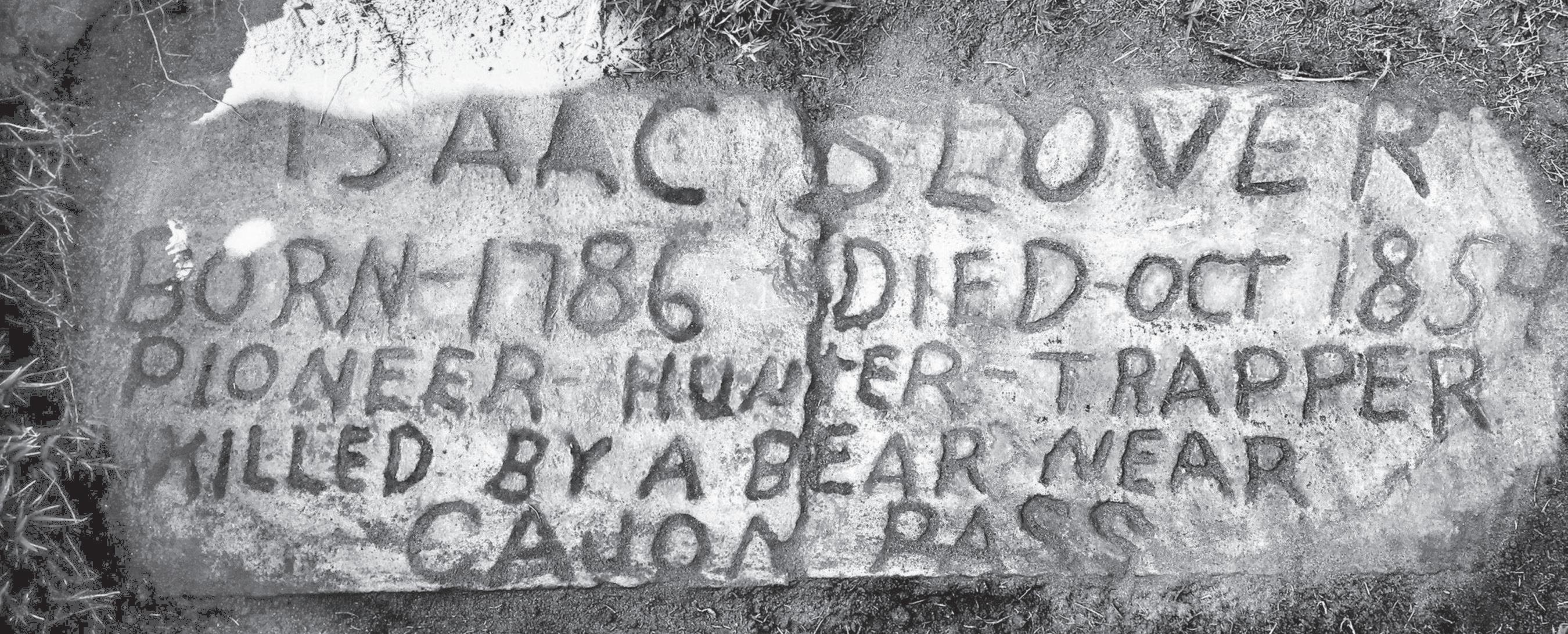

Slover’s final chapter came in San Bernardino, where he continued to hunt and trap. In 1854, he died from injuries sustained in a grizzly bear attack. Today, Slover Mountain in Southern California bears his name — a quiet monument to a man who helped shape the American Southwest.

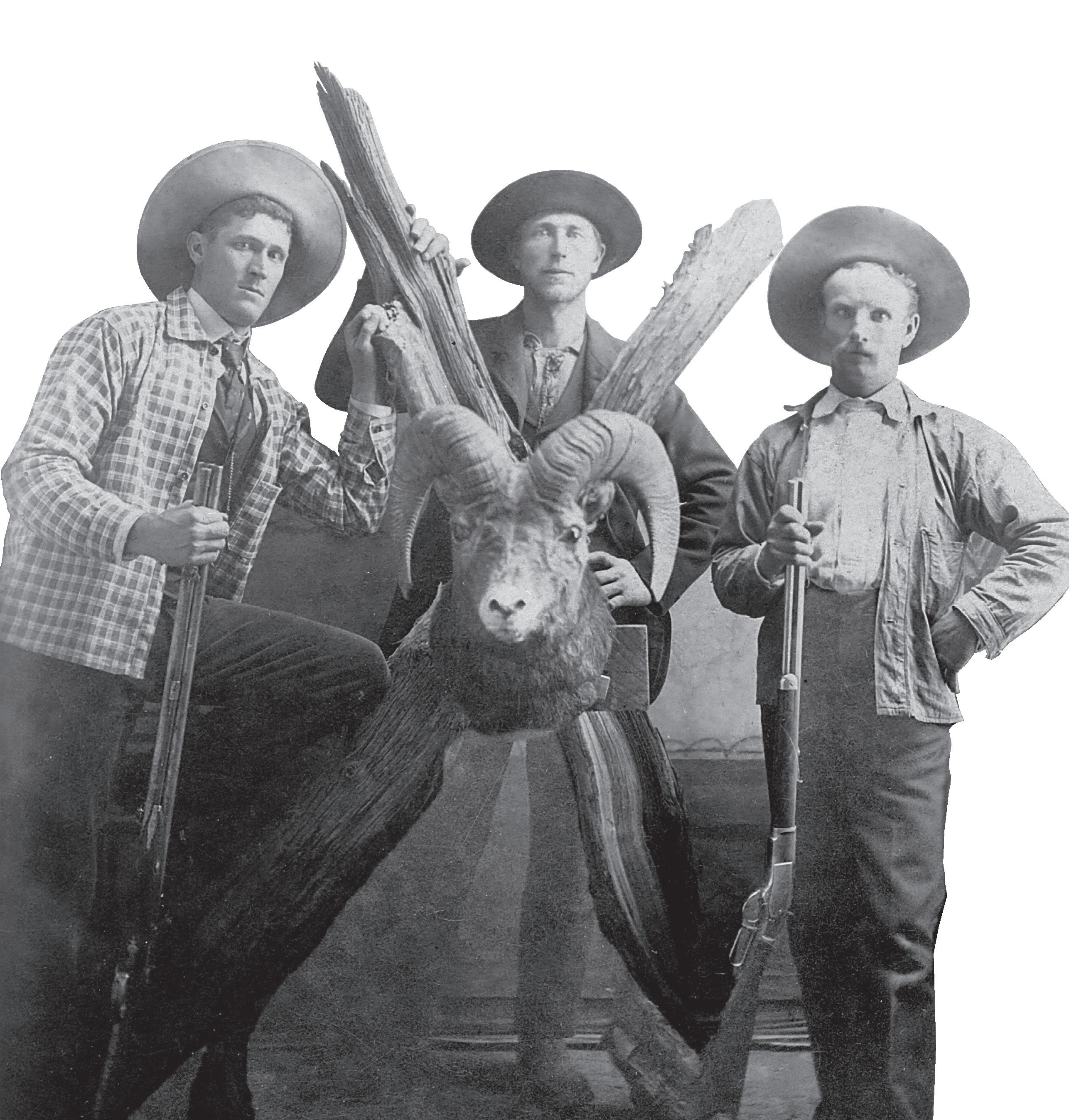

Opposite Top: A photograph taken by Oliver E. Aultman of Taos-area trappers Will Sellers, Charley Compton and Ed Westoby. Aultman opened his photography studio in Trinidad, Colorado in 1890. Westoby homesteaded in Red River.

SOURCES

Tim Green, “The Edge Rover: The Life and Times of Mountain Man Isaac Slover,” Texas Tech University Press, 2024

Loretta Miles Tollefson, “Spring Equals Trappers in Taos,” lorettamilestollefson.com

Hadyn B. Call, “The Infrastructure of the Fur Trade in the American Southwest,” 1821-1840,

Utah State University

“The Story of Isaac Slover,” Pueblo County Historical Society

David J. Weber, “The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest, 1540–1846,” University of Oklahoma Press

SLOVER’S LEGACY & REDISCOVERY

Though largely forgotten in mainstream histories, Slover’s legacy has been rekindled thanks to Green, whose scholarly and personal deep dive into Slover’s life offers new insight into the mountain men of the Southwest. Green’s work not only humanizes his ancestor but also challenges readers to reconsider how American, Mexican, Indigenous, and Genízaro cultures intersected in places like Taos during a time of great flux.

Slover wasn’t a showboating explorer like Kit Carson. He was, in Green’s words, “a hidden gem” of frontier history — quiet, hardworking, culturally adaptable and fiercely independent. Men like Slover, Pope and Young were more than just rugged adventurers. They were economic pioneers, cultural intermediaries, and often, accidental historians. Their journals, marriages and trade routes chart the unwritten history of a region in transition, where the beaver trade temporarily bridged worlds that war and empire would soon divide. In rediscovering Slover and his fellow mountain men, we uncover not just the bones of a forgotten trade, but the sinew of the multicultural Southwest as it once was — and as it, in many ways, remains.

This map from “The Edge Rover: The Life and Times of Mountain Man Isaac Slover” shows Slover’s progress across the U.S. over the course of his life.

PARTIALLY BURIED, SUNKEN GRAVESTONE FOUND IN AGUA MANSA CEMETERY IN COLTON, CALIFORNIA, THAT WAS UNCOVERED. ISAAC SLOVER WAS AN EARLY PIONEER IN THE SAN BERNARDINO VALLEY. SLOVER MOUNTAIN WAS NAMED AFTER HIM.

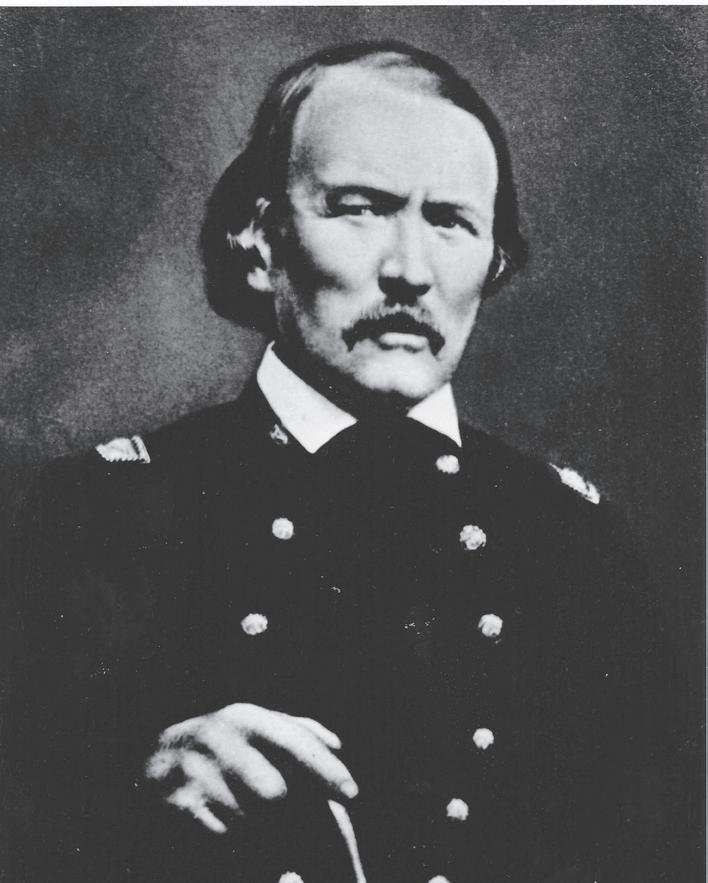

Kit Carson: Hero, villain orboth?

Carson’s story reveals the legends we celebrate … and the truths we must face

BY CINDY BROWN

INTaos, Kit Carson’s name is everywhere — on a road, the electric co-op, his house and museum, and the Carson National Forest. But like many historic figures, his legacy is mixed and complex — so much so that the Town of Taos has undertaken a process to consider renaming Kit Carson Park, the town’s central green space.

To understand how his name became so firmly rooted in the landscape and lore of Taos, we must go back to the beginning of Carson’s remarkable — and at times controversial — life.

Christopher Houston Carson was born in a log cabin in Madison County, Kentucky, on Christmas Eve 1809, according to Hampton Sides in “Blood and Thunder: The Epic Story of Kit Carson and the Conquest of the American West.” A year later, the family moved to the Missouri frontier. Carson’s father died when he was 8. One of 10 children at home, Carson was apprenticed to a saddle maker in Franklin, Missouri, where he learned leatherwork-

ing and listened to the stories of trappers and traders heading out on the Santa Fe Trail. He hated the work. After two years, he secretly signed on as a laborer with a merchant caravan bound for Santa Fe. His employer published notice of his escape and offered a one-penny reward to bring the boy back. Carson, however, made it to Santa Fe and immediately set out for Taos.

He was drawn to the life of a mountain man and trapper and pursued it for more than a decade — until beavers became scarce from overhunting. During this time, he married his first wife, an Arapaho woman named Waa-nibe, translated as Singing Grass. Marriages between Native women and mountain men were common then, according to Marc Simmons in “Kit Carson and His Three Wives.” Waa-nibe died giving birth to their second child. Carson then married a Cheyenne woman whose name has been translated as Making Out Road. Their marriage ended when she placed Carson’s

belongings outside their teepee — a clear sign of divorce in Cheyenne custom.

After taking his oldest daughter, Adaline, to live with relatives in Missouri, Carson met Lt. John Fremont, who had been tasked with leading an expedition up the Platte River into the Rocky Mountains. Carson signed on as a guide and served for three expeditions until 1846. During that time, he met and married a young Taos woman, Maria Josefa Jaramillo. The couple would have eight children and remain married until their deaths — just one month apart — in 1868.

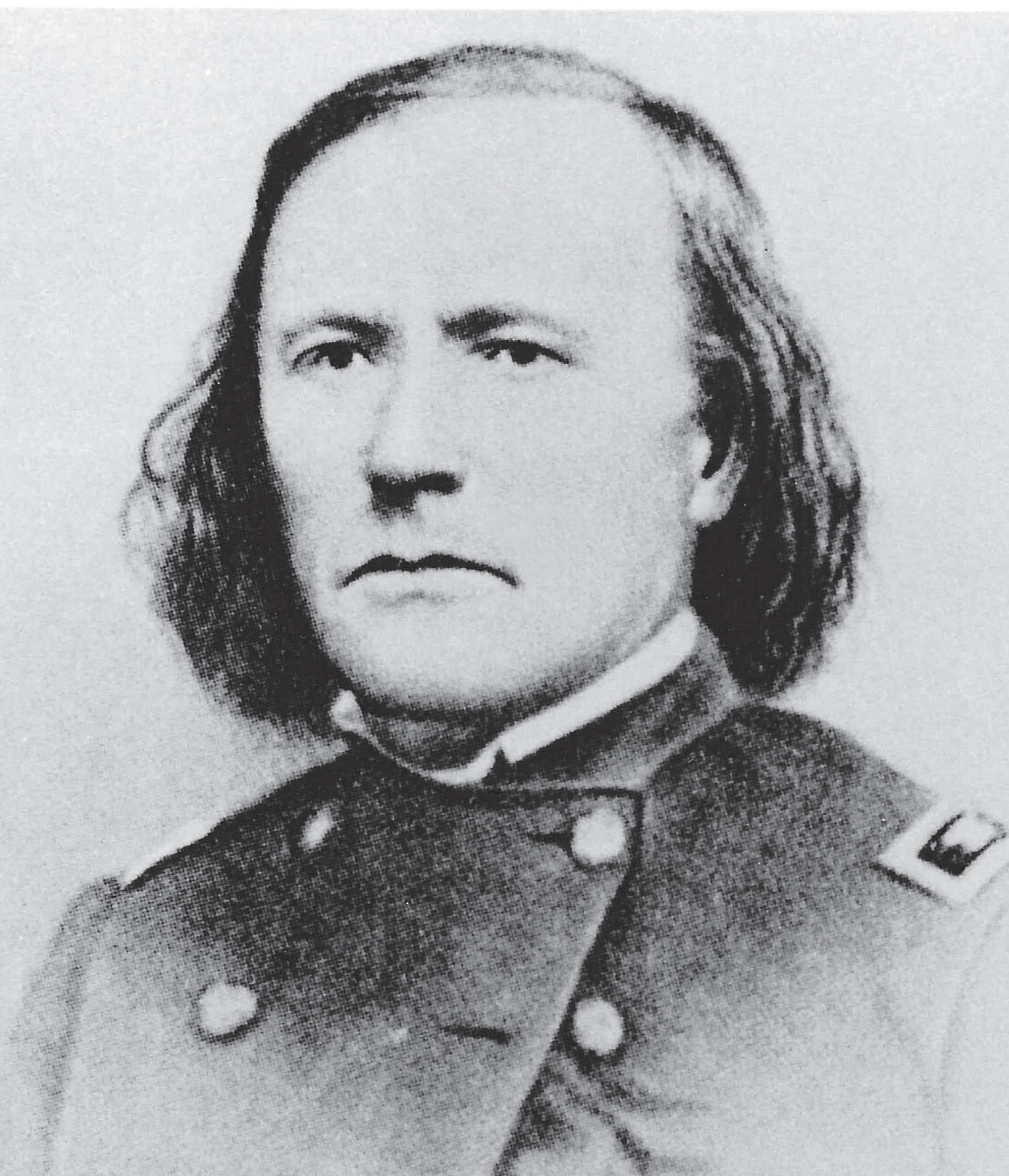

During the Mexican-American War, Carson was made a colonel in the U.S. Army and served as a scout and courier. He further cemented his national reputation by leading General Stephen Kearny from the New Mexico Territory to California, according to the U.S. National Park Service. Later, he served as an agent for the Office of Indian Affairs for Northern New Mexico.

When the Civil War began, Carson helped organize the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry and led troops at Val Verde and in the decisive Battle of Glorieta Pass.

In 1861, Confederate sympathizers tried to remove the American flag that flew over Taos Plaza. Carson and others guarded the flag around the clock, and Congress later granted special permission for it to be flown there both day and night.

KIT CARSON’S MIXED LEGACY

“Yes, Christopher Carson was a lovable man,” Sides recounts. “Nearly everyone said so. He was loyal, honest, and kind. He was a dashing Good Samaritan — a hero, even. He was also a naturalborn killer.”

Carson’s outsize legacy grew during his time as a guide, bolstered by reports written by Fremont and his wife, Jessie.

“He lionized his guide Kit Carson, painting him as a daring and larger-than-life frontiersman,” according to Simmons.

“Kit Carson has a tremendous following,” said Dave Cordova, manager of the Kit Carson House and Museum. “People have a lot of respect for who he was and what he did. A few people question his motives, but like many things in history that we try to understand, a lot of times it doesn’t make sense. That was the condition of life at the time — he did what he did.”

Cordova explained that people began writing stories about Carson during his lifetime — stories that didn’t necessarily reflect who he truly was.

“In these books, called ‘Blood and Thunder’ books, Carson was more of a cowboy with a sixgun than the mountain man that he was, but the stories took hold all over Europe,” he said. The museum has examples of these graphic novels and booklets translated into many languages, including French and Italian.

“Carson was at the right place at the right time,” Cordova added. “He was taking his first daughter to St. Louis and coming back when he met Fremont. If they hadn’t met, we wouldn’t be talking today.”

THE LONG WALK

Although there is evidence that Carson participated in massacres of Native people during his years as a mountain man and guide, it is his leadership of the Long Walk that perhaps raises the most difficult questions about his legacy.

Carson was ordered to relocate Navajo (Diné) and Mescalero Apache people from their homelands in the Four Corners area to the Bosque Redondo at Fort Sumner — more than 300 miles away. Carson initially refused and tendered his resignation, but it was not accepted, according to the park service.

In 1863, he led efforts to round up the Navajo. When those efforts failed, his troops cut down thousands of peach trees and burned food sources in Canyon de Chelly. Eventually, the Navajo began to surrender. In March 1864, more than 3,000 began the walk to Bosque Redondo. Thousands more would follow. Hundreds died along the way, and another 2,000 died at the reservation.

Carson applied to be the superintendent of the Bosque and was selected for the post.

“Carson worked tirelessly on behalf of the Dine

pleading for more supplies and medicines, goading the soldiers, hearing Navajo grievances,” Sides recounted.

Brig. Gen. James Carleton believed the Navajo and Mescalero would settle down and become farmers, but the land was unfit. Crops failed, and the water was undrinkable. In 1866, Congress began an investigation, and in 1868, a treaty allowed the people to return home.

Carson retired from the Army in 1867 and died in May 1868 — one month before the Navajo began their walk home.

‘SEND a RUNNER’

Navajo runner Edison Eskeets has made several long-distance runs to honor his heritage, including the 330-mile route from Canyon de Chelly to Santa Fe. In 2021, Eskeets and Jim Kristofic co-authored “Send a Runner: A Navajo Honors the Long Walk,” which documents the 2018 run and weaves in the history of the walk and other violence against Native people.

The authors spoke to the Kit Carson Park Renaming Committee on July 23. Chair Genevieve Oswald called the book “a powerful and profound work, offering a perspective on frontier history as it was experienced here in our region of the Southwest.”

Eskeets said, “The book is really about mankind. At the end of the book, there’s a line: ‘If your blood is red, you are my kind.’” He noted there were once 80 to 100 million Indigenous people in what is now the U.S.; today, the number is about 6 million.

Kristofic added, “This book came up out of the ground that Edison ran.” The run began at Canyon de Chelly and ended in Santa Fe — the place where military plans for the Long Walk were made.

He emphasized that the Long Walk was preventable.

“There are always off-ramps to any armed conflict,” he said. “They are ignored.”

According to Kristofic, Gen. Carleton wanted Navajo land for its rumored gold and devised a strategy to remove the people. Carson, though skeptical of the plan, executed it.

“He thought it was a bad idea, yet he went ahead,” Kristofic said, noting Carson had long fought against the Navajo as an agent for the Utes.

“Carson led these raiding parties into Navajo country, burning people’s food,” Kristofic said. “That is why it worked — the corn cannot run.”

At the end of their comments, Eskeets said, “Our responsibility is to grip and understand our backgrounds and try to have a betterment of where we are going with this journey. Collectively we have a duty and a role.”

RENAMING KIT CARSON PARK

Oswald launched the renewed renaming process after a constituent asked what had happened to a 10-year-old effort to rename the park. At that time, the Taos Town Council voted to rename it Red Willow Park, but rescinded the decision after objections from Taos Pueblo leaders. Oswald said she wanted to fulfill the promise to reconsider the name.

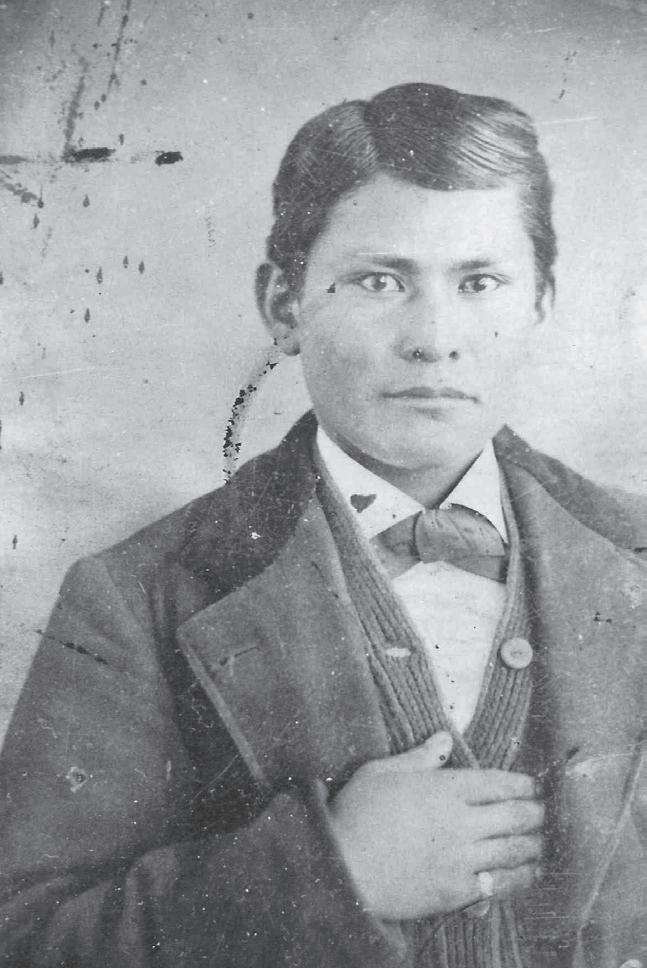

LEFT: JUAN CARSON, ADOPTED APACHE SON OF KIT CARSON. RIGHT: DAUGHTERS OF JOSEFA AND KIT CARSON TERESINA AND STELLA CARSON.

The council voted to form a committee. Oswald met with the Taos Pueblo Council, and Second Tribal Sheriff Jesse Winters was appointed as a representative. The committee began meeting in February and will complete its work before year’s end, making a recommendation based on the value that are identified in the process

Oswald acknowledged not everyone supports the effort.

“It is hard to let go of history and stories. They become personal for everyone,” she said.

“It is difficult but possible to walk in the space between conflicting points of view.”

Despite some pushback, many Native people have thanked her, and Taos Pueblo’s participation signaled support. Oswald summarized: “This effort is about ideas. What do we want to glorify and identify with as a community?”

To read about the Kit Carson Park Renaming Committee’s work, visit taosnm.gov.

All photos are from the collection of Taos Historic Museums. Courtesy of the Lunder Research Center, CouseSharp Historic Site, Taos,

NM.

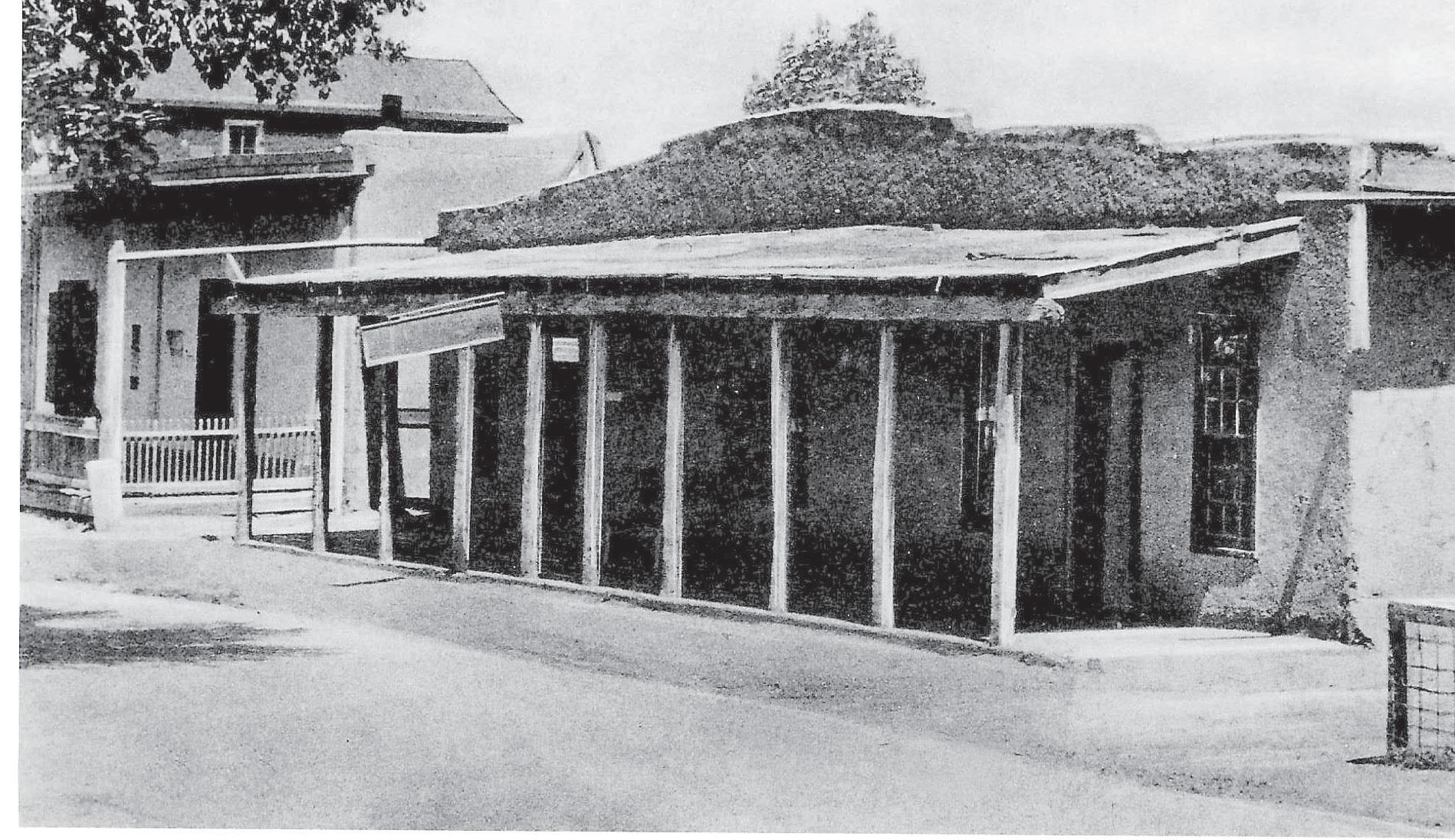

KIT CARSON HOUSE IN AN UNDATED PHOTO

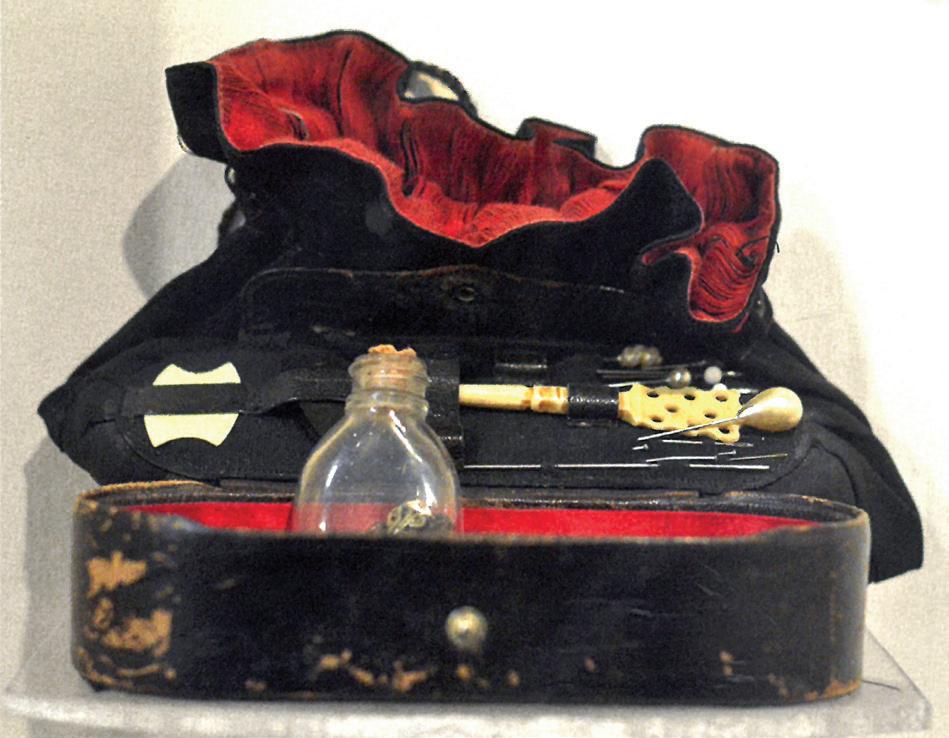

JOSEFA CARSON'S SEWING KIT

KIT CARSON BASEBALL CARDS

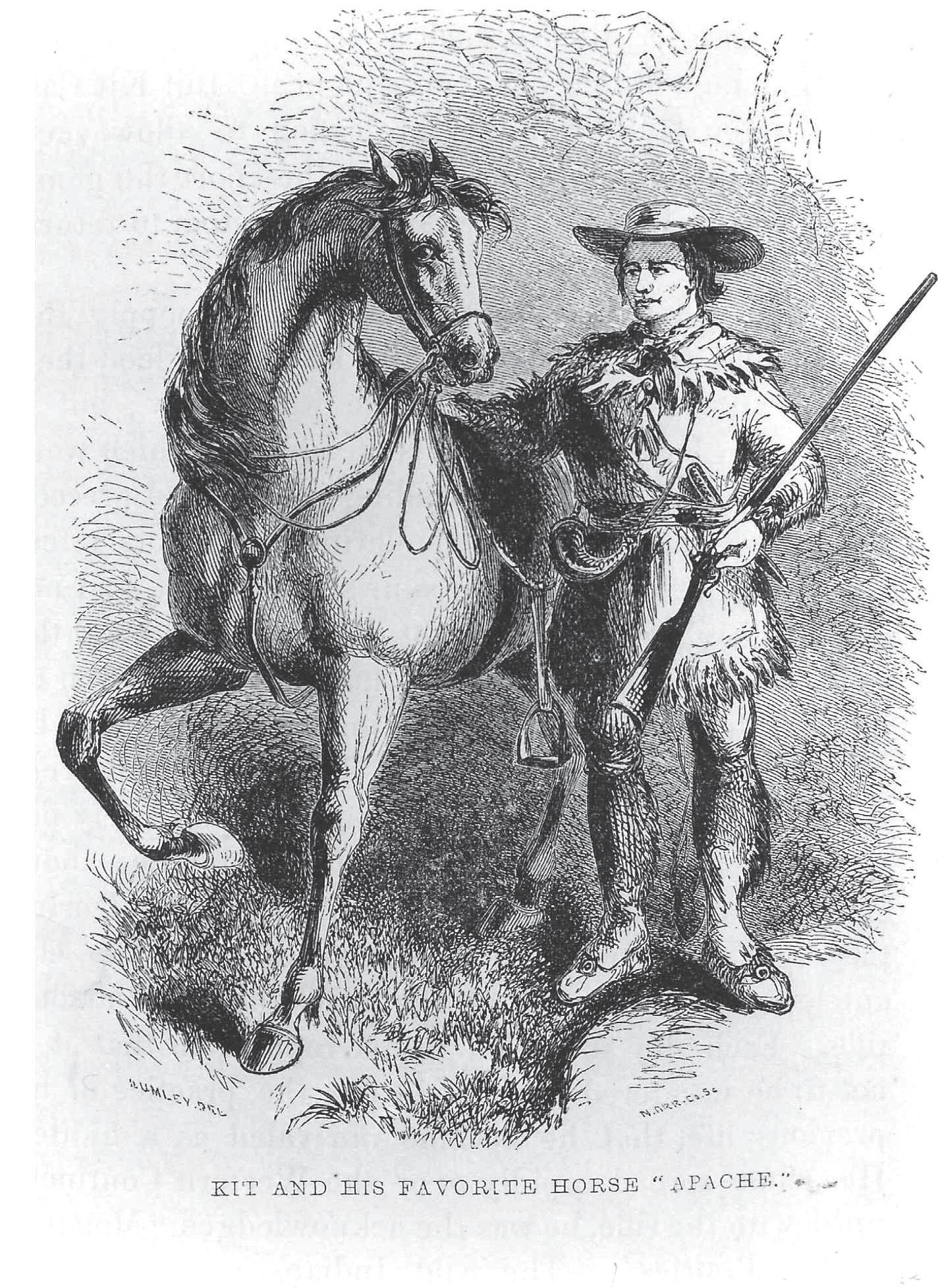

DRAWING OF KIT CARSON AND HIS FAVORITE HORSE APACHE, FROM THE FIRST BIOGRAPHY OF CARSON,"THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF KIT CARSON, THE NESTOR OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS" BY DE WITT. C. PETERS. PRINTED IN 1858.

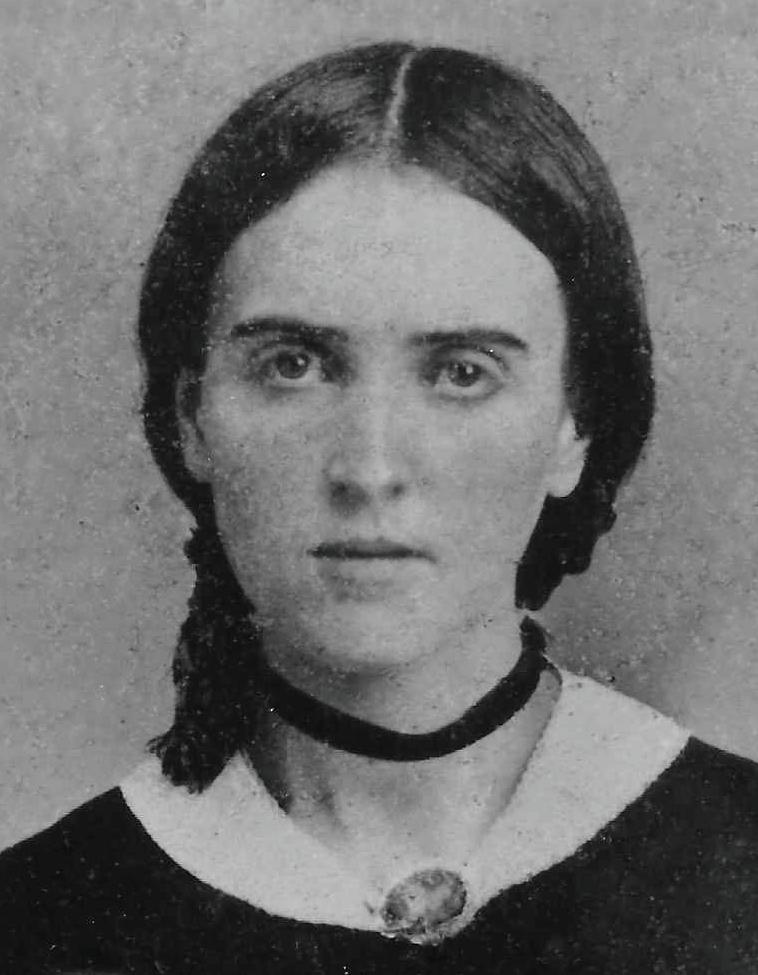

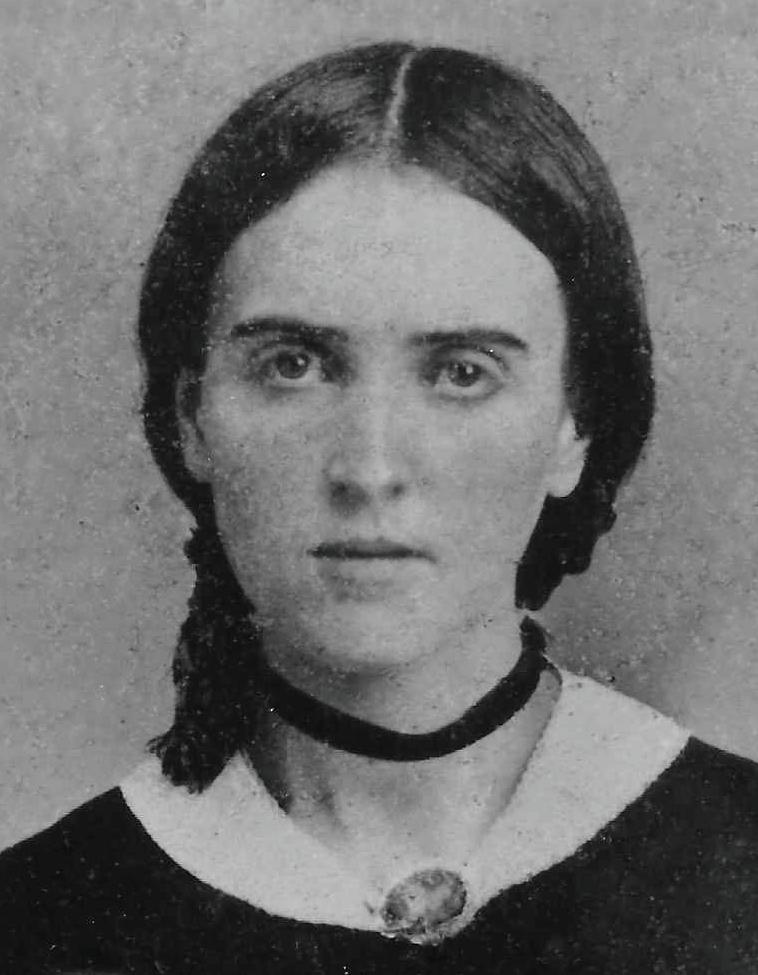

Josefa Carson

A quiet force in Taos’ history

BY ELLEN MILLER-GOINS

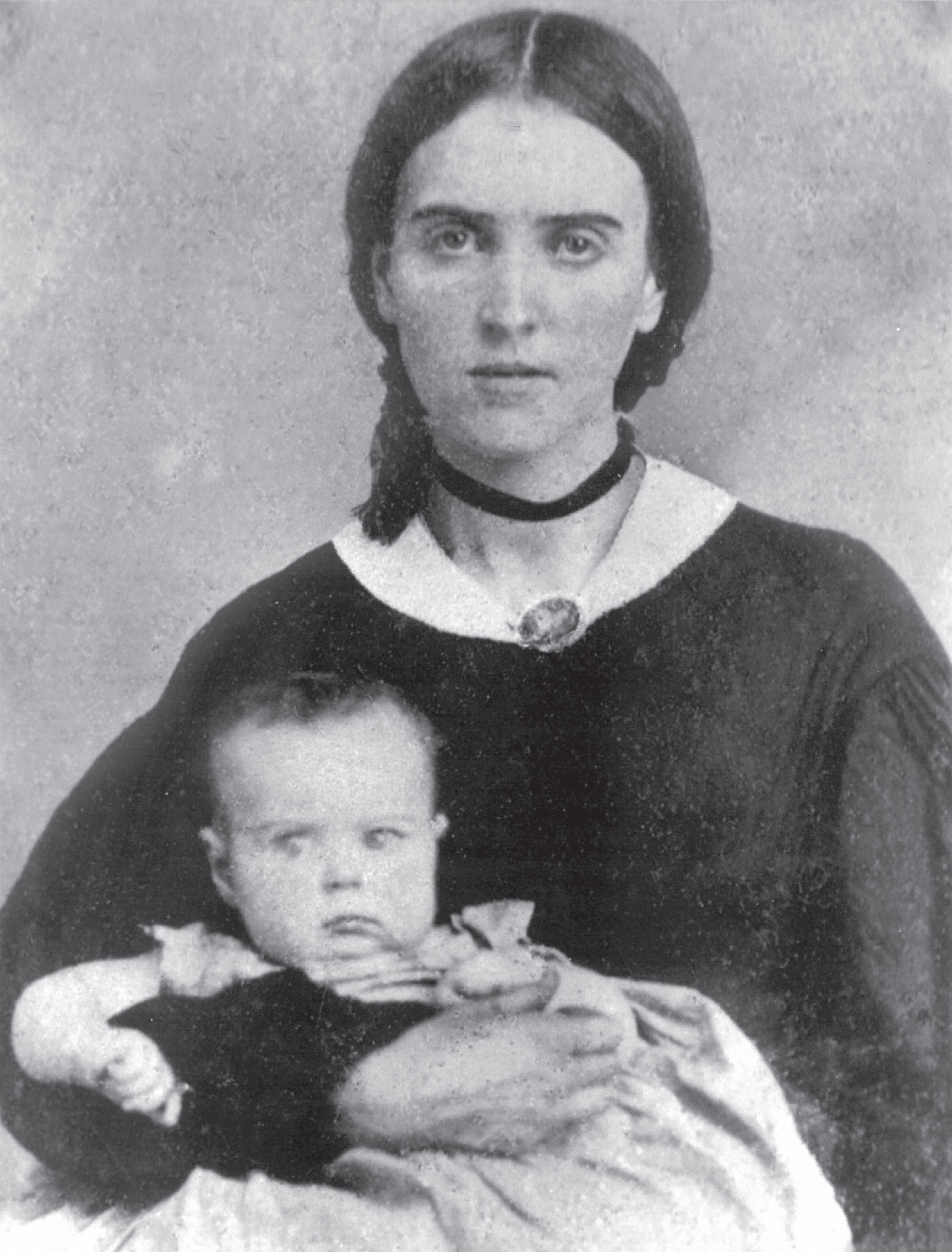

History remembers Kit Carson as scout, soldier and controversial frontiersman. But beside him — often holding the family together while he roamed — was Maria Josefa Jaramillo Carson, a woman whose life mirrored the turmoil and resilience of 19thcentury Taos.

Born in Santa Fe on March 19, 1828, Josefa grew up in a respected Hispano family. Her father, Francisco Jaramillo, was a prosperous merchant; her mother, María Apolonia Vigil, came from landholding stock. Into this world of tradition and upheaval, Josefa stepped into history at the tender age of 15.

When Christopher “Kit” Carson asked for her hand, he was nearly twice her age and already a figure of some renown. To prove his devotion, he converted to Catholicism and won over her formidable father. The two married Feb. 6, 1843, at Our Lady of Guadalupe

Church in Taos, with Gov. Charles Bent and Josefa’s sister Ignacia — Bent’s common-law wife — standing as padrinos. Carson built her a modest home near the plaza, today the Carson Home and Museum.

Life with Kit was rarely easy. He was gone for months, sometimes years, guiding expeditions, fighting wars or serving as an Indian agent. Josefa kept the household running and raised a bustling brood — seven of her own children plus several adopted Navajo youngsters. She became known for her hospitality, offering food, shelter and warmth to neighbors, clergy, soldiers and tribal visitors alike.

But Josefa’s life was far from sheltered. In 1847, she and Ignacia were trapped inside the Bent home during the Taos Revolt. As an enraged mob attacked, the sisters dug desperately through an adobe wall to save themselves and their children. Later, Josefa testified in the trials that followed — an act of bravery that under-

scored the quiet strength she carried all her life. That strength was matched by compassion. When Ute warriors arrived at her home with a captured Navajo boy, Josefa traded one of her horses for his freedom. It was just one of many small acts that revealed her character.

Josefa’s story ended April 1868 with the birth of their eighth child in Boggsville, Colorado. Just two weeks later, she died of complications at age 40. A month later, brokenhearted, Kit followed her to the grave. Today, the two rest side by side in Taos’ Kit Carson Cemetery.

Though history often places her in the shadow of her famous husband, Josefa Carson’s life offers another lens on the American Southwest: one of endurance, grace and courage. As historian Barbara Schultz observed, her story is “not just a history of Josefa — it’s a history of Taos.”

JOSEFA CARSON

When we work together, we have the power to create positive change in our communities. That’s why Nusenda Credit Union is proud to partner with local organizations whose core values align with our own.

At Nusenda, we are more than just a bank, we are a credit union dedicated to improving our members’ financial wellbeing and the places we serve. The social and economic health of our community drives us, as does supporting innovations that promise to build a brighter future for generations to come.

We’d like to thank our partners for the shared commitment to making our communities better places to live and work. Together, we can do great things!

Learn more at nusenda.org

@NusendaCU |

Our Traditions Run Deeper Than

La Hacienda de los Martínez de Taos

A living historical testament in time and space

BY DAVÍD FERNÁNDEZ DE TAOS

We never tire of declaring that the Taos and Northern New Mexico region is a very special place — one could even say a country of its own — with its stunningly beautiful and mysterious geography; its human story extending far into antiquity, even before “since time immemorial”; the flow of generations through time in the bloodlines and interwoven lives of its people through change and circumstance; and even the homes, dwellings and structures that still stand on the landscape after centuries, some for thousands of years.

We would be remiss if we did not express our sincere and humble gratitude for the lives and works of the ancestral familial lines of blood and spirit that have brought us to where we are now.

So we say, “Gracias a todos nuestros antepasados quienes nos han regalado nuestra herencia de la vida y de los modos de vivir como compadres y comadres en un espíritu del norte bien compartido en El Norte.”

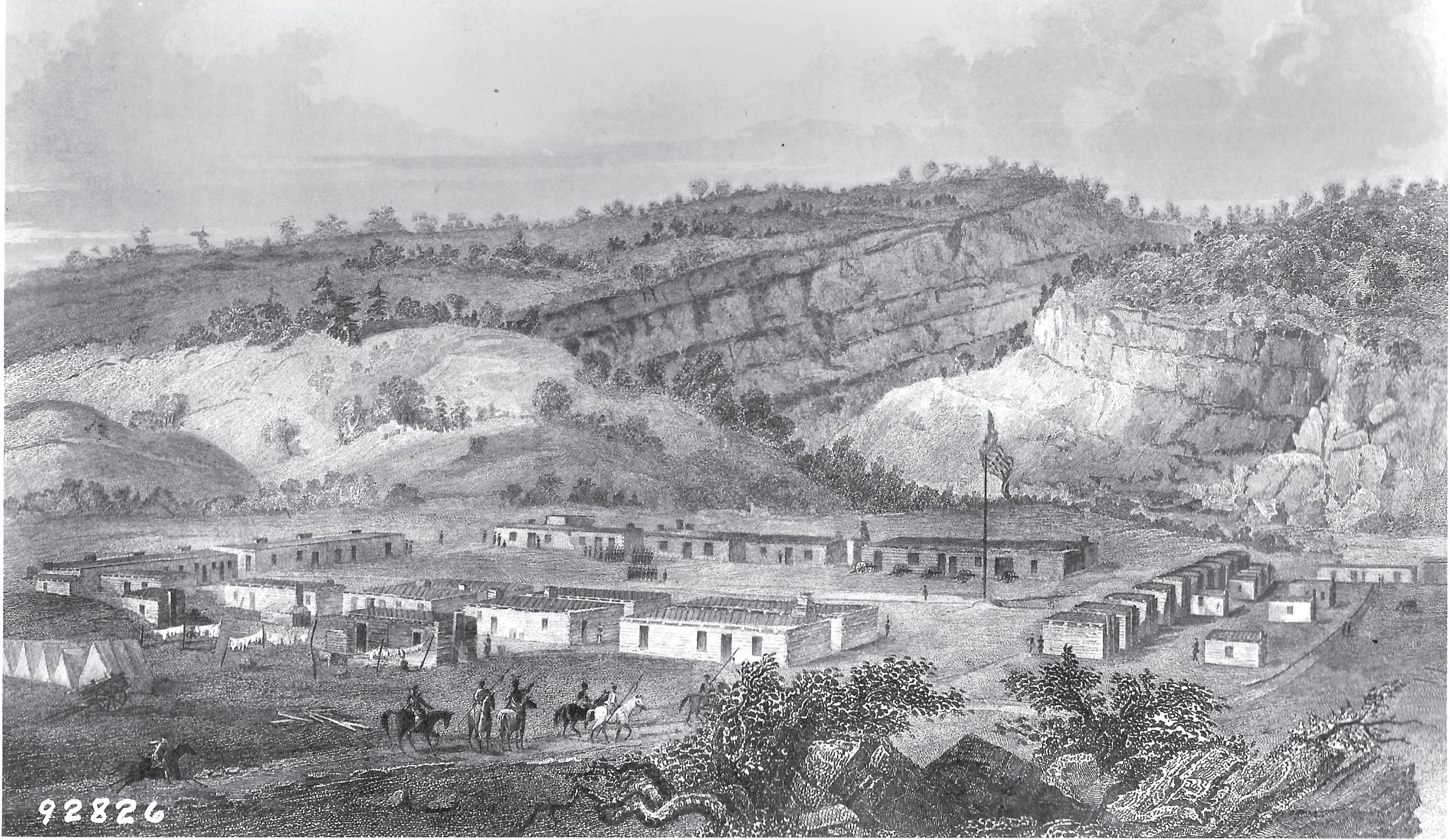

This article focuses on La Hacienda de los Martínez de Taos, built in the early 1800s, during an era when El Norte was still a part of Spain, and Spanish was the predominant language in nearly every aspect of life. Spanish colonists and settlers had arrived in El Norte in the 16th century. In the early 1800s, Spain’s authority was relinquished when Mexico gained independence; yet the Spanish language and customs continued to prevail. By the mid-1800s, the U.S. had assumed governmental and political control of El Norte and

New Mexico; still, the old Spanish customs and language endured, many uniquely infused with the much older ways of Indigenous cultures.

La Hacienda de los Martínez was — and remains — a reflection of the early- to mid-1800s. It stands today as a living historical, cultural and even spiritual way station, a “living museum” that has evolved alongside the changing landscape of El Norte. Though termed a “museum,” La Hacienda continues to serve as a cultural family house for the people of the region — a multi-faceted cultural and historical gem.

Many are familiar with the historical facts and figures surrounding La Hacienda de los Martínez. Also known as the Don Severino Martínez House, it is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and the New Mexico Register of Cultural Properties.

In 1804, a gentleman named Severino Martínez — later known as Don Antonio Severino Martínez — relocated his family from Abiquiú to Taos and purchased this property on the bank of the Rio Pueblo de Taos, about 2 miles southwest of the Taos Plaza.

His original adobe home expanded into a Casa Grande — a large house — with two inner courtyards surrounded by 21 rooms. The thick-walled, fortress-like structure provided protection against attacks by Comanche and other raiders.

It became the largest hacienda in the Taos Valley, serving as both a working farm and ranch. The Martínez family raised a variety of animals and grew crops such as corn, squash, wheat and chile. Many of the people who worked on the farm were acquired from Indigenous and Mexican traders. Severino prospered through trade along the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, dealing in goods from both El Norte and Mexico. His family gained prominence in the Taos Valley, and Severino himself served as alcalde mayor, the chief governing official, of El Valle de Taos.

One of his sons, Padre Antonio José Martínez — el Cura de Taos — became the pastor of the Taos Valley’s Catholic community. He emerged as the preeminent spiritual and political voice of the region, and his influence in El Norte remains strong to this day.

Today, La Hacienda de los Martínez is owned

by the Taos Historic Museums and stands as one of the few remaining Spanish Colonial haciendas in the U.S. open to the public. It honors the lives and works of the early Hispano settlers in el Valle de Taos. Importantly, the Hacienda is not simply a static museum with exhibitions of an earlier era — though it does display many cultural and historic artifacts. It remains an active, vital part of the Taos Valley’s living heritage.

It hosts the annual Taos Trade Fair in late September, reenacting Spanish Colonial life and trade among Indigenous people, trappers, “mountain men” and Spanish settlers, with demonstrations by blacksmiths, woodcarvers and weavers. It

Gracias a todos nuestros antepasados quienes nos han regalado nuestra herencia de la vida y de los modos de vivir como compadres y comadres en un espíritu del norte bien compartido en El Norte.

is also a venue for traditional Taos Valley Fiesta events and royalty; spiritual and religious customs like San Isidro Labrador in May; Semana Santa/ Holy Week events; Christmas plays; Día de Todos Santos y de los Fieles Difuntos; and many other community cultural events, including educational and scholarly programs.

La Hacienda de los Martínez is indeed a museum, but at a much more active and dynamic community level. Governed by a dedicated and visionary board of directors, it continues to serve as a cultural anchor for Taos, alongside the Ernest Blumenschein Museum of Art.

COURTESY PHOTOS

RIO PUEBLO FLOWS BY THE MARTINEZ HACIENDA / ZOE ZIMMERMAN / TAOS NEWS FILE PHOTO

PADRE MARTINEZ / COURTESY PHOTO

THE MARTINEZ HACIENDA / COURTESY PHOTO

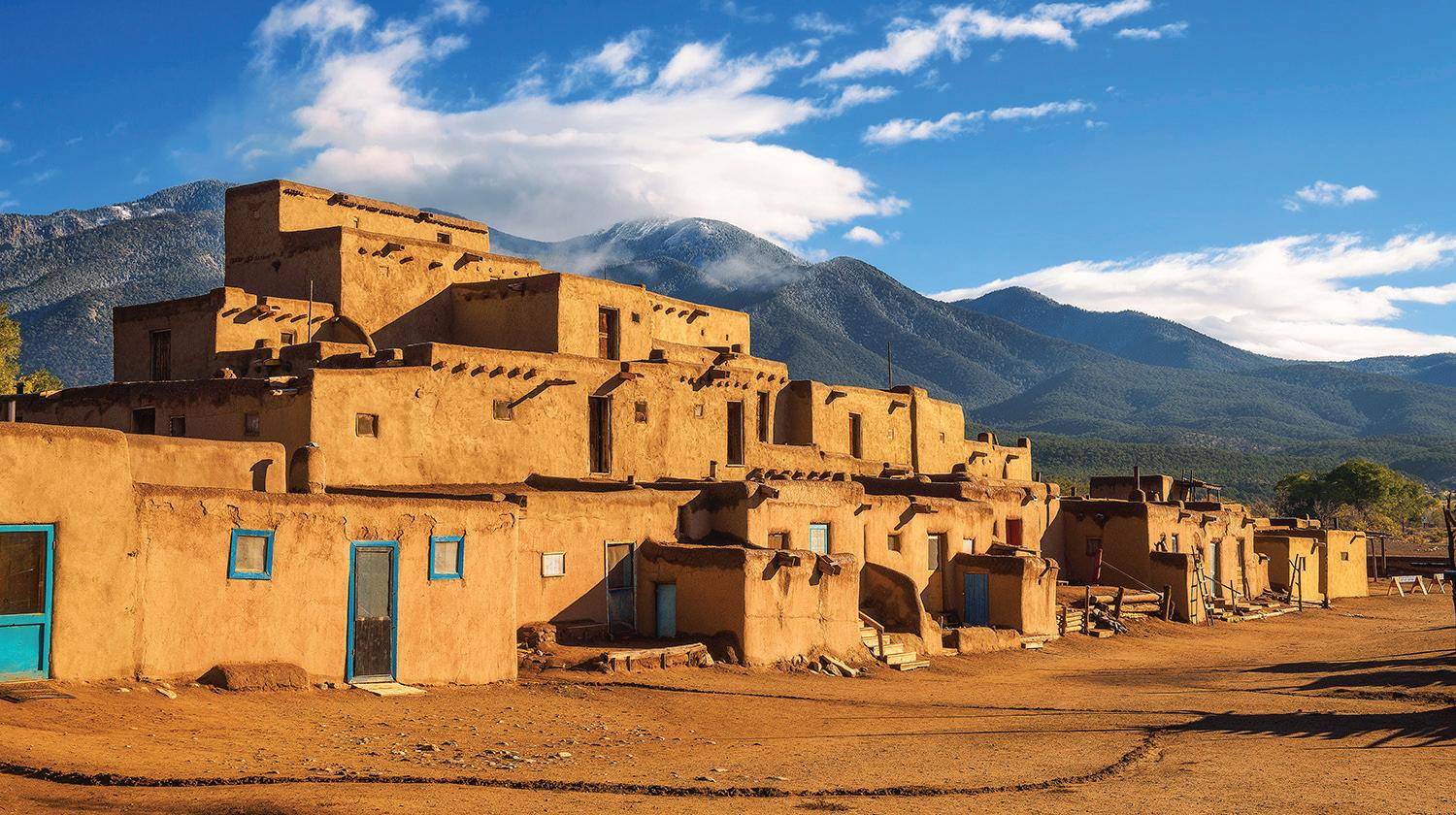

“Taos

Pueblo represents a significant stage in the history of urban, community and cultural life and development in the region . . .continuously inhabited and the largest of the Pueblos that still exist.”

—UNESCO

The Only Living Native American Community Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

2025 Taos Pueblo Governor Edwin Concha. Photo: Rick Romancito for the Taos News