1917 – 2000

I AM WHAT YOU MIGHT CALL A SUEMURA SHOBUN FANATIC. I have liked his characteristic black bamboo works since I first saw them; they were distinctive and eccentric, with sharp bends and a beautiful patterning of nodes. Then, in 2015, I encountered School of Fish , and I was lost. The power and presence of the piece hit me the moment I stepped into the room. The asymmetric curve and gentle inward curl of the front rim are such an exquisitely thrilling counterpoint to the scale and heft of the body. The spacing between lengths of bamboo, the rhythm of the nodes, and judicious use of decorative rattan are perfectly considered. The thought, ambition, and attention to detail that went into School of Fish are unmistakable without coming across as belabored or fussy. Even elements that I might consider flaws in other (lesser ) works, such as the drilling of superfluous holes for the rattan stitching, just made the work even more charming to me.

Of course, I had to have it.

Over the next decade, I went on to acquire nearly 40 additional works by Suemura. They range from his jaw - dropping exhibition pieces to karamono (Chinese - style ) flower baskets with an almost awkward whimsicality, to architectonic assemblages, to works destined for sophisticated tea rooms made with the impeccable style and refinement of the Kansai bamboo tradition. In Suemura’s hands, bamboo swoops, rolls, and coils. It can curve gracefully, angle crisply, loop acrobatically, or trail off in a scribble.

At the moment I am writing this, I believe I might have one of the world’s finest Suemura Shobun collections. By the time you read this, that may no longer be true.

I admit to being ambivalent about mounting this show. However, I do recognize that, logically and as a responsible gallery owner and employer, buying art and refusing to show or sell it is not a sound business plan. I will console myself with the thought that having an exhibition at least gives me the opportunity to print a catalogue.

I don’t think Suemura currently gets the level of appreciation he deserves as an artist. This was not always true Higashi Kiyokazu shared his father Takesonosai’s thoughts on Suemura, saying “My father seemed to consider him as the best regarded bamboo artist of his generation in the Kansai region…He also said that the fact that Mr. Suemura never won a Tokusen Prize despite his long career at the Nitten exhibitions was evidence of the poor judgment of the Nitten judges.”

I want Suemura to be counted among the great bamboo artists of the 20th century. I want people to use superlatives when they mention his name.

Most of all, I want you to fall in love with Suemura’s work the way I have.

n Margo Thoma

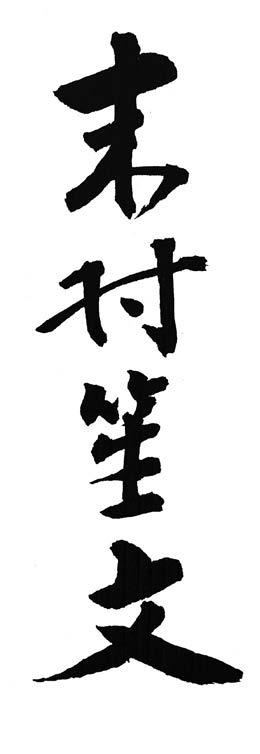

SUEMURA SHOBUN n 1917 – 2000

Suemura Bunzo was born in 1917 in Uchiawaji, Osaka City. As a child, he contracted polio. His family feared Suemura would not survive. Fortunately, he recovered from the disease, but his leg was impaired. Worried about his son’s future, his father thought that Suemura should learn an occupation that would allow him to work while seated. He approached a business acquaintance, who was a patron of the bamboo artist Yamamoto Chikuryusai I (1868 –1945), for an introduction, hoping that Yamamoto would consider taking Suemura as an apprentice.

Yamamoto Chikuryusai I was a master bamboo artist, who had won renown through his participation in both national and international expositions. It was not the custom of the Yamamoto family to take on students from outside the family. However, after meeting Suemura, Chikuryusai agreed to accept him as a live -in apprentice after high school, provided he completed a series of preparatory assignments beforehand. Suemura was directed to take lessons in tea ceremony, ikebana, and Japanese - style painting in addition to his regular schooling. In 1929, while Suemura was still in school, Chikuryusai passed his artist name to his eldest son and took on the name of Shoen. In 1936, at the age of 18, Suemura moved in with the Yamamoto family and began five years of intensive training under Shoen.

In 1941, Suemura completed his apprenticeship and became an independent artist. Shoen gave him the artist’s name “Shobun,” consisting of two characters “Sho,” from his teacher’s name, and “Bun,” from his own name “Bunzo.”

Two early works from 1941, the first year of Suemura’s professional career, are featured in this exhibition. They make for a striking contrast. Folding Fan Shape Flower Basket ( pg 16) is an Osaka literati - style basket, in which Suemura makes extensive use of the Yamamoto family’s signature tamagumi suehiro (jeweled blind) technique of zigzag rattan decoration. It exemplifies the traditional, refined karamono (Chinese - style) baskets that the Yamamoto family was so well known for. In contrast, Suemura’s Twisting Bamboo Flower Basket, ( pg 16 ) which was exhibited at the 1st Osaka City Exhibition, marks a radical departure from the aesthetics of his master, revealing the young artist’s creativity and nascent individual style. It is a large basket with an assertive composition, highly tactile, stimulating, and vibrant. By splitting the wide strips of bamboo into three layers, he is able to twist the bamboo into free and powerful curves, contrasting them with the soft rattan loops underneath. The complicated weaving and rattan stitching of the base, rim, and handle demonstrates his mastery of the technical skills he learned during his training.

Suemura had been independent for less than a year when Japan entered WWII on December 7, 1941. As the war intensified, the Yamamoto family evacuated to Minoh City to avoid the air raids. Even after he was drafted, Suemura remained in Osaka, where he was assigned to work in a

Twisting Bamboo Flower Basket , 1941, 17.25 × 16.5 × 16.5 inches

factory for the war industry. Osaka was hit hard by the war. From March to August 1945, U.S. bombing raids destroyed 344,000 homes. The war ended on August 15, 1945, but recovery took time. After the war, Suemura continued to work in the same factory, which converted to making card tables. He did not resume his artistic career until after his marriage in 1949. His new wife Katsuko actively supported her husband’s return to artmaking, personally visiting ikebana teachers throughout Osaka to secure orders for baskets. In 1951, Suemura successfully exhibited his first artwork at the governmentsponsored national exhibition Nitten ( Japan Fine Art Exhibition). Though there is no photographic record, the title indicates that it was a mat - weave, jar - shaped flower basket with a diagonal line pattern.

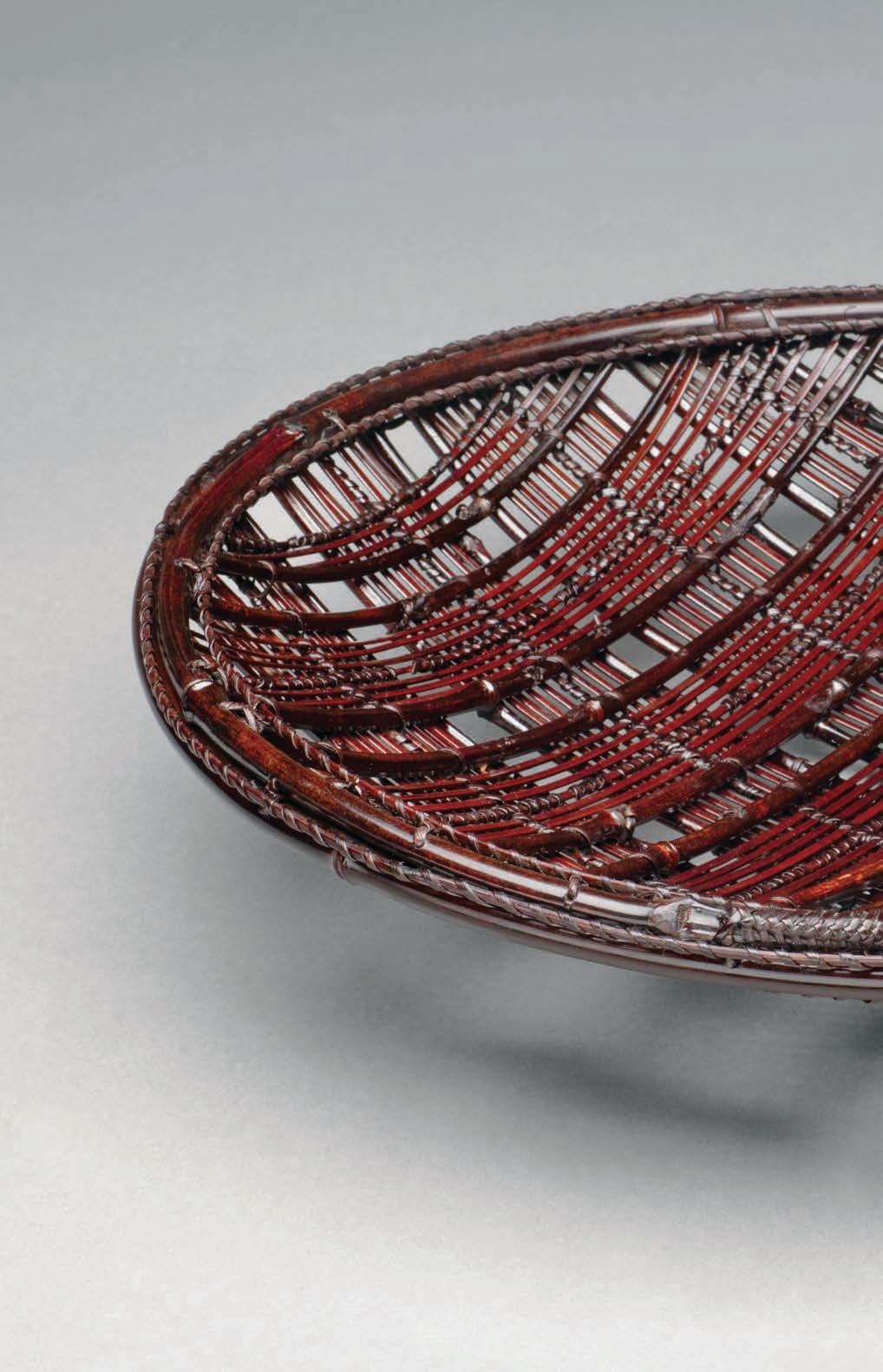

Suemura’s 1953 Nitten exhibition piece was a bold, asymmetric presentation tray called Sitting Crane. He used parallel line - construction, rather than weaving, to create a unique shape that resembled a partially collapsed paper lantern. The following year, he submitted another asymmetric tray in the theme of spreading feathers entitled Peacock. These forms were quite original, with no visible reflection of the influence of the Yamamoto family.

Throughout the 1950s, Suemura continued to use madake ( timber bamboo) and line construction to create unique vessels with a modern feel. The works became increasingly architectural, with modular designs, clean lines, minimal ornamentation, and soft, simple curves. This was a type of bamboo artwork that viewers had not seen before; it had more in common with the emerging design movement of midcentury modernism than traditional Japanese basketry. Suemura created a few pieces in this style, such as Hedge ( pg 18) and Windows. Although he added the designation “flower basket” to the titles of these works, a work like Windows reads far more convincingly as pure sculpture.

In the late 1950s, Suemura began to experiment with black bamboo. Typically called shichiku ( purple bamboo) by Kansai artists, this bamboo gradually darkens from green to to speckled brown to dark ‘purple’ over the course of two years. The use of black bamboo itself was not new to the bamboo artists; earlier Osaka artists used wide strips in their informal, rough - plaited baskets. Suemura’s Purple Bamboo ( pg 41) and Shigarami Flower Basket ( pg 55) are examples of works in this style.

Suemura was, if not the first, then one of the first artists to use unsplit culms of skinny black bamboo to compose his art. In an interview conducted in 2000, Suemura told the author, “I like working with black bamboo from Kyushu, which is traditionally used to make fishing poles. The nodes express distinct patterns and rhythms when I use this material. I find the visual effect so beautiful.”

The fact that Suemura used black bamboo, a visually powerful material with its striking natural color and pronounced nodes, to create unique shapes is what makes him such an original artist. In the kogei (craft art ) tradition, when using materials with such distinctive characteristics, the artist typically does

Windows ,1961, 21 × 12.75 × 11 inches

not seek to create inventive forms but rather to highlight the characteristics of the materials. However, Suemura pursued the creation of even more powerful works by combining the strength of the material with his own sculptural vision.

Suemura’s decision to feature the natural beauty of whole black bamboo presented him with certain challenges. Since the bamboo was not split, the artist had to take extra care to ensure that the bamboo he used was free from insects. He dried the bamboo for five years before carefully inspecting each culm for traces of white powder on the surface, a sign that insects might be living inside. Rather than using chemical leaching to remove the oil and sugar from the bamboo, Suemura used the much more laborious process of slowly heating the bamboo over an open flame and wiping off the oil as it came to the surface. This fire - roasting process also helped to intensify the color of the bamboo. Suemura then applied an oil stain to even out the color, followed by a coat of urushi lacquer. Only then would he be ready to begin constructing the form of his work, heating each length and bending it into the desired shape. Great skill would be required to bend bamboo culms of differing thicknesses into matching curves. This distinctive material and the innovative designs crafted from it soon became Suemura’s signature. Even today, a quarter century after the artist’s death, his with marushichiku (round purple bamboo) works are instantly recognizable.

Ledgestone (pg 28), Longevity, and even Ritual Vessel (pg 24) are particularly interesting for understanding Suemura’s progressive thinking towards handling material. In order to materialize the form he envisioned and create a sharp angle, Suemura did not hesitate to bend the whole bamboo so that it buckled, compressing and flattening the round shape of the culm. This may not seem like a big deal to the Western viewer, but in the traditionally conservative world of Japanese kogei , artists are trained to respect their medium. Consequently, there is an instinctive taboo among bamboo artists about intentionally breaking bamboo for solely aesthetic reasons. Even decades later, only a few contemporary artists, such as Nagakura Kenichi and Kawashima Shigeo, have regularly dared to break this unspoken rule. Suemura’s openness to experimentation can be seen also in his willingness to incorporate man - made materials, such as the stainless steel in Hedge, and use newly available technologies such as epoxy in his work.

Suemura was not the only artist who went through a foment of creativity and innovation in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. In fact, these three decades are one of the golden periods in the history of modern bamboo art. Working through the public exhibition system, bamboo artists began liberate bamboo from its utilitarian roots and push the boundaries of what was acceptable when it came to form, scale, material, and functionality. The Japan Contemporary Kogei Artists Association was founded in 1961. The association proclaimed that kogei artists were no longer limited by “functionality.” Suemura was a member of this new organization.

Longevity ( Kotobuki ) , 1960s –1970s, 7.5 × 13.25 × 13.25 inches

Although Suemura pursued new forms of expression, he rarely entered the realm of pure abstraction. Even at their most idiosyncratic, his works almost always retained some connection to the vessel form. By 1979, Suemura’s viewpoint had become a bit more conservative. He joined the Japan New Kogei Artists’ Alliance, which believed that if non - functional expression went too far, it was in danger of becoming expression for expression’s sake and losing kogei ’s human connection.

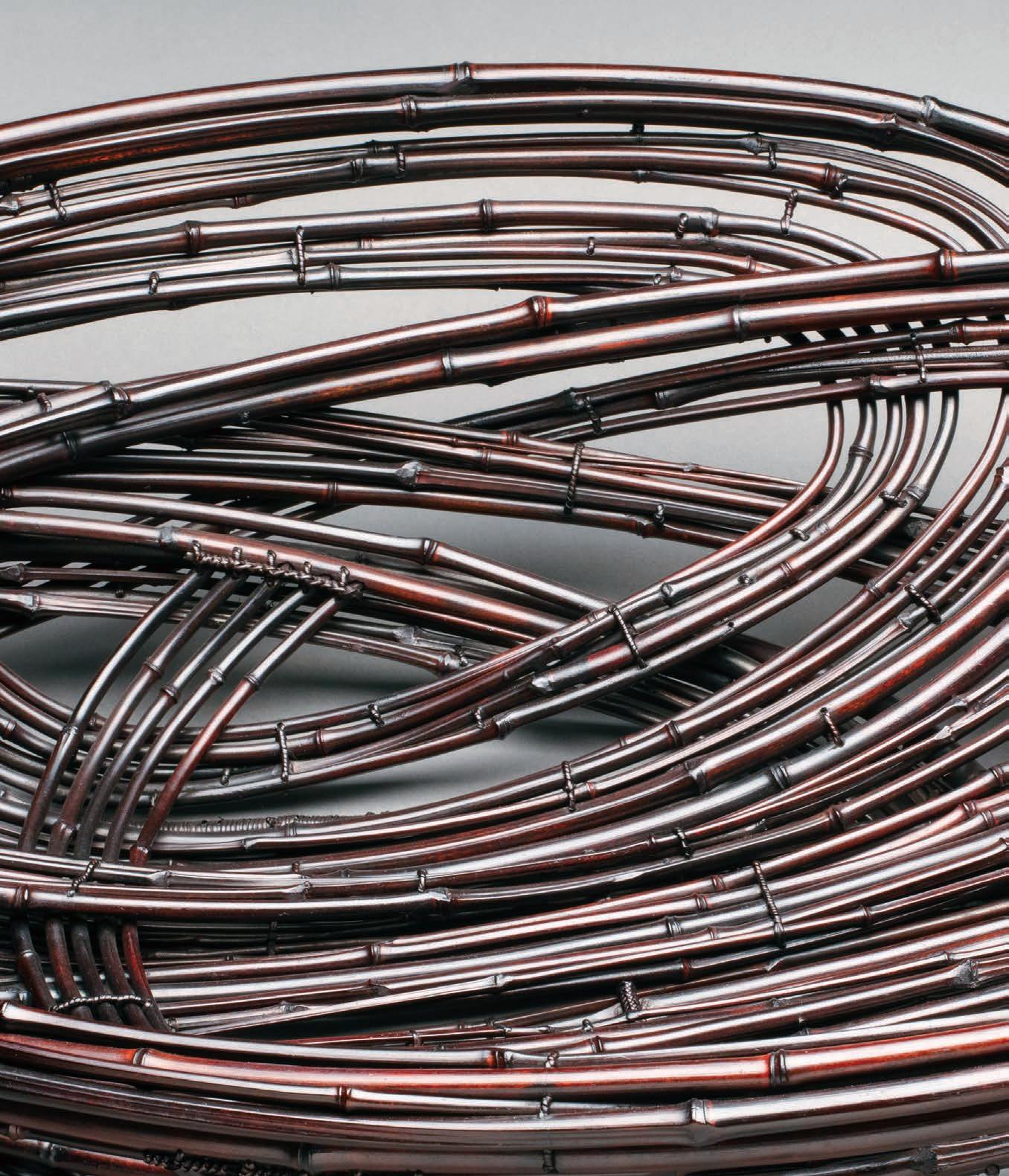

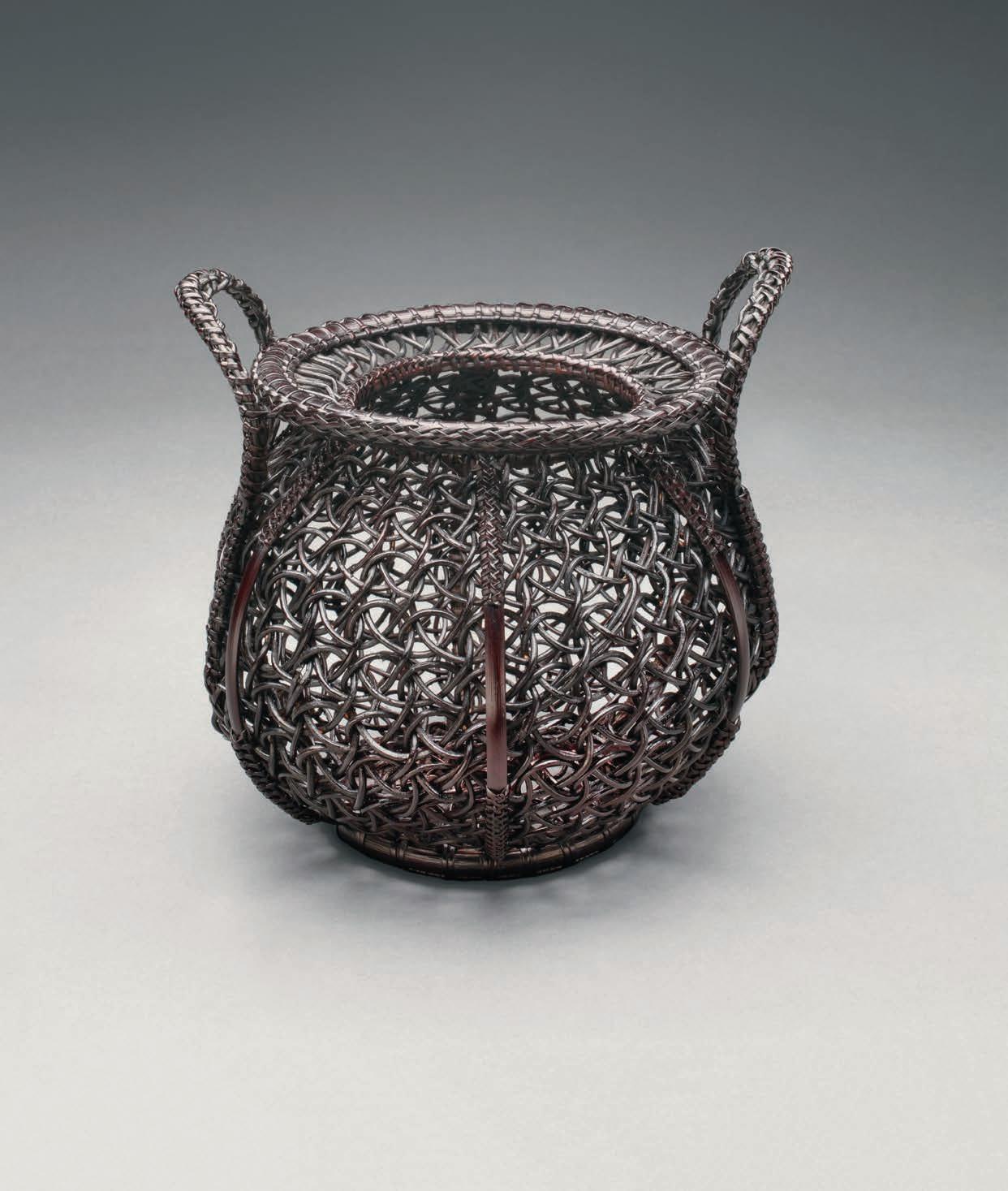

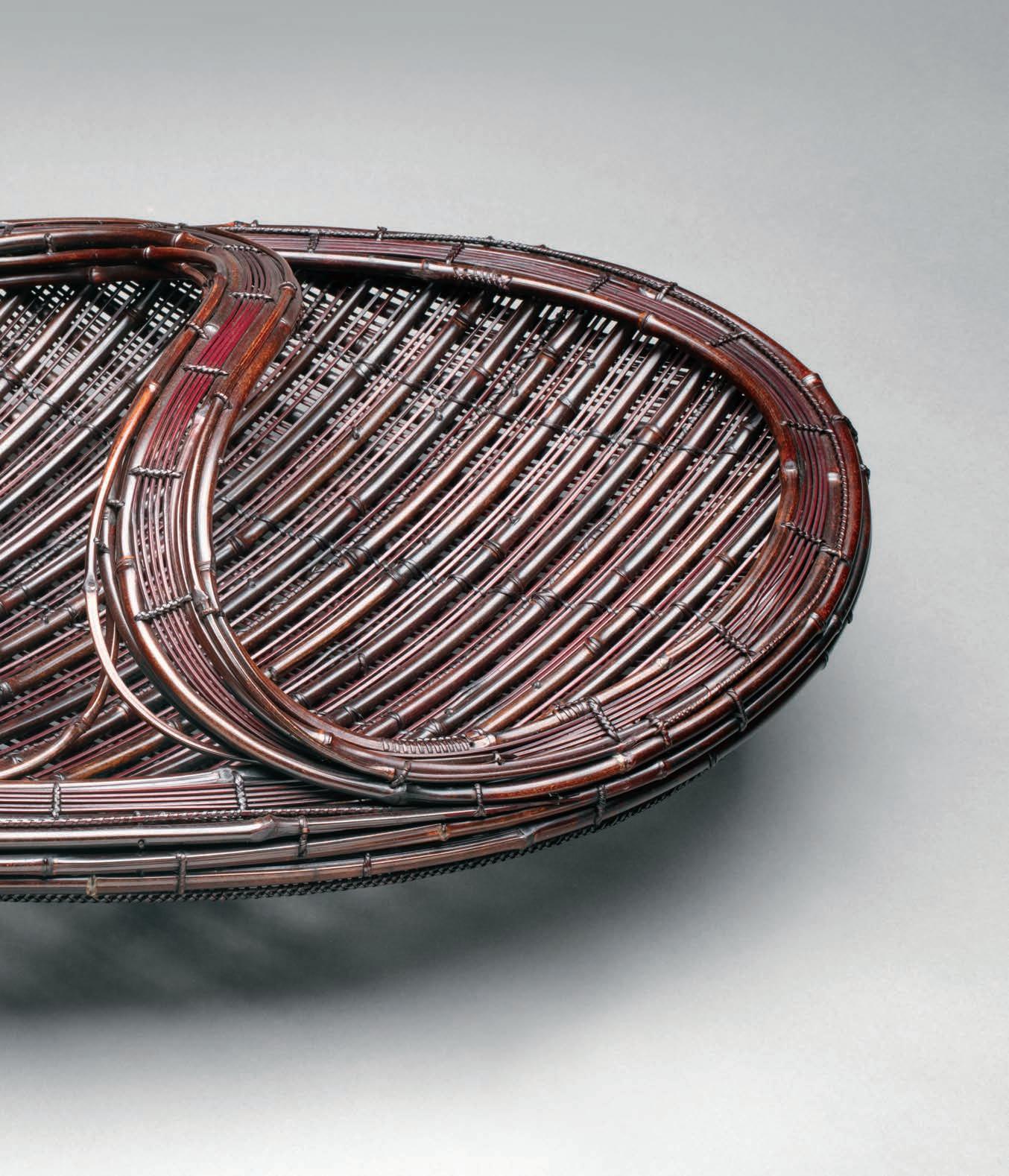

The works Suemura created in the 1980s and 90s reflect this more traditional viewpoint. Bamboo Leaf Boat (pg 50), an oversized offering bowl from 1989, is an iconic piece from this period. It is made from a single length of old smoked bamboo that the artist has carefully split then reassembled into a boat - shaped tray. The artist’s hand rests lightly on this piece, allowing the character and quality of the bamboo to take center stage. Another late work, the tea screen Fragrant Breeze ( pg 47 ) from 1987, is inspired by an early summer day with a gentle breeze scented by young leaves. Suemura’s deep knowledge of tea ceremony and his excellent design sensitivity are beautifully expressed in this work. Even towards the very end of his life, he never lost his ability to wow. The latest work in this show, made in 1996, Double - handled Offering Tray ( pg 52) is dynamic and exciting. Made from Suemura’s beloved black bamboo, two layers of criss - crossing bamboo strips and culms, lashed together with rattan, create a plaid - patterned base, enclosed by a whirling rim made from several lengths of round bamboo, which arc and entwine upwards to create the gorgeous curving handle.

Suemura created a wide range of works in his 60 - year career as an artist. His exhibition pieces are magnificent examples of his exceptional talent, with mesmerizing forms that no other artist had created before. Alongside these ambitious works, throughout his career, even during his most experimental periods, Suemura also continued to make beautiful traditional baskets. For 45 years, he held annual solo exhibitions in Osaka, where he sold baskets meant to be used and appreciated in people’s homes. He worked alone, without students or assistants. To share the full spectrum of his creative genius, TAI has acquired over 30 representational works by Suemura, several of which should be considered masterworks, not only of this artist, but of 20th century bamboo art.

Suemura Shobun told the author in 2000, a few months before his death, “I want to make something beautiful out of bamboo. The problem for me is that the things I see in nature are always so much more beautiful than what I can create. For the last thirty years I have been collecting seashells. The shapes are beautiful. I cannot create such beauty as an artist, but in a way, they challenge me to try harder.”

n Koichiro Okada

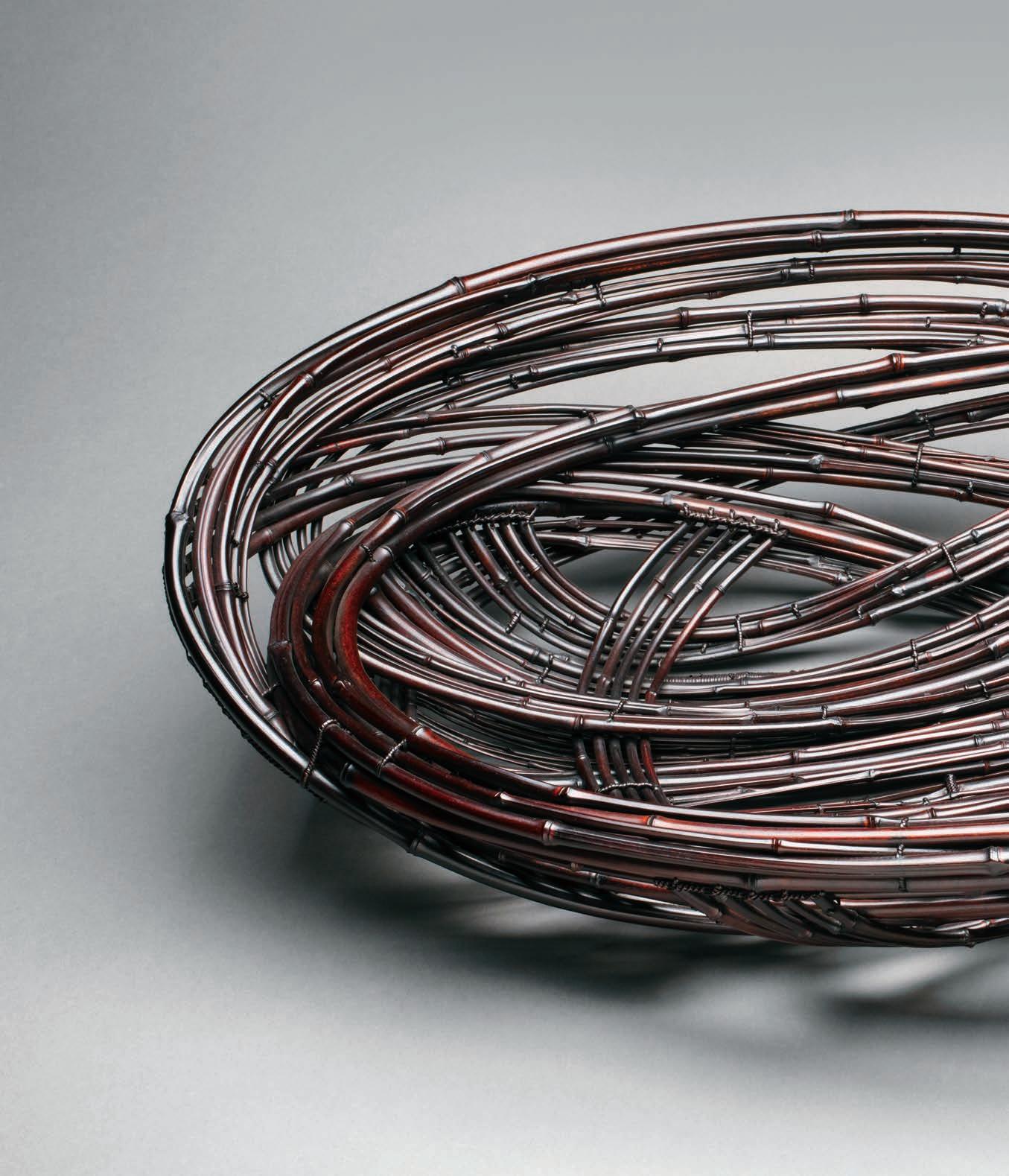

Double - handled Offering Tray ,1996, 5 × 18 × 14.75 inches ( detail )

20 Nest , 1958, 8 × 8 × 8 inches

Flight ,1969, 8.5 × 31.5 × 18 inches

Entwined ,1971, 8.5 × 19 × 19 inches

Opening Fan Flower Basket ,1970s, 6.5 × 11 × 11inches

< Shippo Flower Basket ,1970s –1980s, 8.5 × 8.5 × 8.5 inches

School of Fish ,1973, 8.25 × 26 × 16 inches

This catalogue accompanies the exhibition SUEMURA SHOBUN n 1917 – 2000 August 29 – October 1, 2025 1601 Paseo de Peralta • Santa Fe, NM 87501 505.984.1387 • taimodern.com © 2025 TAI Modern Photography by Paloma Mankus Fan - shaped Flower Basket ,1991, 7.5 × 10.5 × 6 inches