Eric Johnson Fade to Black

Eric Johnson Fade to Black

Eric Johnson at The Ranch in San Pedro, July 2025. Photographed by Guillaume Zuili.

Fade to Black, new work by Eric Johnson, features the artist’s transition from polychrome sculpture to entirely black pieces.

The color black can symbolize a wide array of concepts, both positive and negative. It often represents power, elegance, formality, and mystery, but can also be associated with death, mourning, and evil. Black can also symbolize strength, resilience, and the unknown.

Louise Nevelson’s signature use of black in her sculptures was a deliberate artistic choice, not a simple negation of color. She viewed black as a unifying force, a way to create a sense of totality, peace, and even grandeur in her works. Her monochromatic palettes, often employing black spray paint, transformed disparate found objects into cohesive and mysterious assemblages. For painter Ad Reinhardt, addressing the essential attributes of black was a process of negation, or subtraction, of all extraneous elements, including referential imagery, narrative, emotion, gestural incident and superfluous high color. Johnson is on the same journey.

The exhibition offers a first look at a project that the artist has been developing for the past eight years. The work presented has been specifically created for this show.

Fade to Black at solo, curated by Ron Linden.

On view from August 16 until October 4, 2025

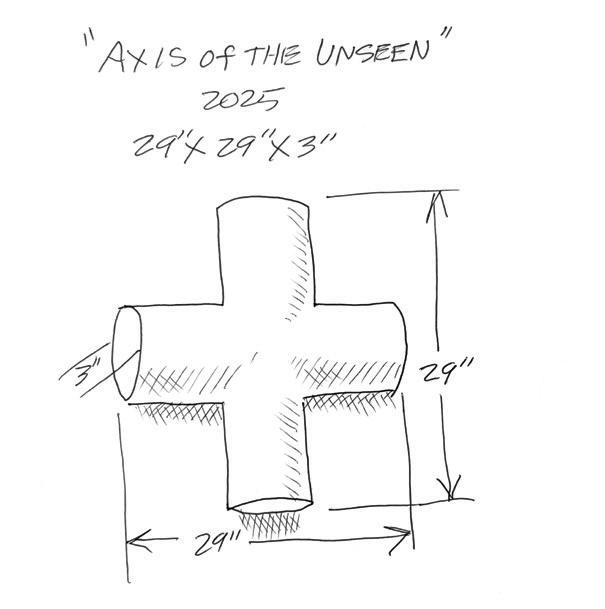

All works are polyester resin and automotive pigment.

Eric Johnson – Darkness is not the absence of light

Eric Johnson’s new body of work consists of a series of black, mysteriously handsome hybrid painting-sculpture, except for a tall Madame X sculpture that commandeers the room. The simple, geometric yet soft shapes hang on the wall but protrude into the space of the room. The shadows they project integrate the works into their surroundings, blurring the distinction between object and environment. The deep, matte black resin they are made of absorbs the light, yet is occasionally reflected, bouncing off angles and soft curvature, getting back to the viewer in intermittent flashes.

Eric Johnson (b. 1949) grew up in Southern California, moving in his early twenties from Burbank to the sun-drenched shores of Laguna Beach. At the time, Johnson made a living as an illustrator, and in Laguna Beach he often rubbed shoulders with New Yorker cartoonists Virgil Pyrch and Dick Olden, surf artist Rick Griffin, and Charles Bukowski, with whom he remembers trading art for a poem. Thanks to the mentorship of art critic and artist Fidel Danieli, who had been his teacher at Los Angeles Valley College1, he met pioneers of the LA Look and Light and Space movements: Craig Kauffman, DeWain Valentine, and Larry Bell, among others. For Johnson, who had so far focused on figurative work, this was a watershed moment. He was mesmerized by their use of bright and sensuous colors, simple shapes, and polished surfaces. Above all, the

way their work engages with light, transforming it into an artistic medium in and of itself and foregrounding perception as a phenomenon, resonated profoundly with Johnson. As the artists of Light and Space, Johnson was enthralled by the vast horizons and bright Southern California light. He had spent much of his life looking at the way light shimmers on top of the ocean waves. He forged lifelong bonds of friendship and mentorship with many of these artists, especially Craig Kauffman and DeWain Valentine. The pioneers of the LA Look made use of plastics, automotive paints and a variety of materials and techniques derived from the California booming aerospace and leisure industries. This was also deeply impactful for Johnson’s art, although not immediately.

Since his youth, and to this day, Johnson has been an automotive enthusiast and passionate Hot Rodder. By age 21, he owned twelve cars that he had bought for cheap as “junk” and lovingly brought back to life, enhancing them both mechanically and aesthetically. He became an expert at mechanics, body work, automotive spraying, and was also making surfboards as a hobby. It wasn’t until a decade later, in the early 1980s, however, that Johnson realized he could put these skills to use in his art. A maker and craftsman at his core, Johnson has a deep work ethic, for which he credits Tony Smith as an inspiration, as well as the influence of his own father, an auto body and fender

expert. Johnson works every day in his studio with ascetic discipline, refusing distractions and interruptions. Making art to Johnson is a way of life, the only one he can imagine: it is as necessary to him as breathing. Over a lifetime of practice, he has attained a level of skills and exactitude unthinkable for most people. His sculpture is not only striking – it is very precisely engineered.

Johnson initially created resin sculptures cast around elaborate wooden armatures, integrating automotive pigments into the resin. Being eminently practical and unwilling to delegate the fabrication, he quickly realized that cast resin was very heavy, and as such, it was becoming increasingly difficult to handle the sculptures themselves as they were becoming larger. In the early 2000s, he pioneered a system of gimbals that allowed him to pour the resin into molds and solidify it as an outer layer. The hollow sculptures looked just as the solid pours but were much easier to handle and cheaper to make. In 2014, he motorized some of his gimbals, which allowed him to increase the scale of his production. The pouring became a communal and joyous moment: Johnson would often move around the gyrating gimbals in a ritualistic synchronous dance and invite friends over for a celebratory barbecue. Once the works emerge from the mold, the surface of the sculptures are lovingly polished, in a labor-intensive process familiar to the artists of Light and Space.

Just as impactful as the influence of Southern California Light and Space artists was that of Brancusi and Tony Smith for their focus

on clean lines, form, and volume. Johnson expresses himself through volume and the vocabulary of shapes that he has developed over the years, much more easily, he feels, than with words. Until recently, Johnson’s simple and clean shapes were rounded and often biomorphic, with soft curvatures evoking living organisms - very specifically the female silhouette in his Madame X series. They were inspired by wavelength patterns, dance, and movement. The pearlescent, shimmery automotive pigments he introduced in the resin reinforced the impression of movement. For decades, Johnson’s sculpture was bright, colorful, sensuous, and sensual.

The new body of work is more austere, more subtle - yet just as rich, and eminently tactile. Volume and form take precedence over color. The sculptures are rendered in matte black, giving immediate emphasis to form. However, one soon realizes that they are far from static. The movement is not imparted by the shape of the sculpture but by the surrounding light and by the viewer’s engagement. Past the first impression of black flatness, one is compelled to spend time with each of the works to carefully study how the light interacts with their surfaces. The viewer needs to slow down, move around the sculpture, look, and discover how they are ever changing. The sculptures reveal themselves slowly, in an experience that is just as intimate as it is enchanting.

Rachel Rivenc, July

31st 2025

Rachel Rivenc is head of conservation and preservation at the Getty Research Institute

All works © copyright Eric Johnson. All rights reserved.

Published in August 2025 by

solo. an art gallery by studio mousetrap is located at 366 W 7th Street, San Pedro, California 90731.

Intro by Ron Linden. Essay by Rachel Rivenc. Photography by Guillaume Zuili. Printed at Acuprint.

Studio Mousetrap, LLC.