Autumn is a special time of year that brings color to artists and aspens. 28

Local woodworker points to practicality while onlookers appreciate the art.

Where to start? And when to finish? It’s the Sunday brunch at The Broadmoor.

Hungry in the Mile High City? These five restaurants have mastered the grill.

Embrace the final days of summer and first days of fall with a meal outdoors.

Western Slope earns place on the wine map with dozens of impressive vineyards.

The life and legacy of Captain Ellen Jack is a colorful and complicated story.

Saving wolves remains the mission at Colorado Wolf & Wildlife Center in Divide.

Director of Content/Magazine Editor

Nathan Van Dyne

Art Director/Designer

Nichole Montanez

Designers

Elizabeth Holderfield

Cat Kammerer

Photographer

Christian Murdock

Writers

Seth Boster

Jennifer Brookland

Kelly Hayes

Debbie Kelley

Jennifer Mulson

Contributors

Daliah Singer

Irene Thomas

Publisher

Christopher P. Reen

President/Chief Operating Officer

Rich Williams

VP of Advertising

Stacey Sedbrook

Executive Editor/VP of Content

Vince Bzdek

Editor

John Boogert

Products

Picnic gear provided by

Sparrowhawk Cookware

Cover Photo/Photograhy

Mark Reis

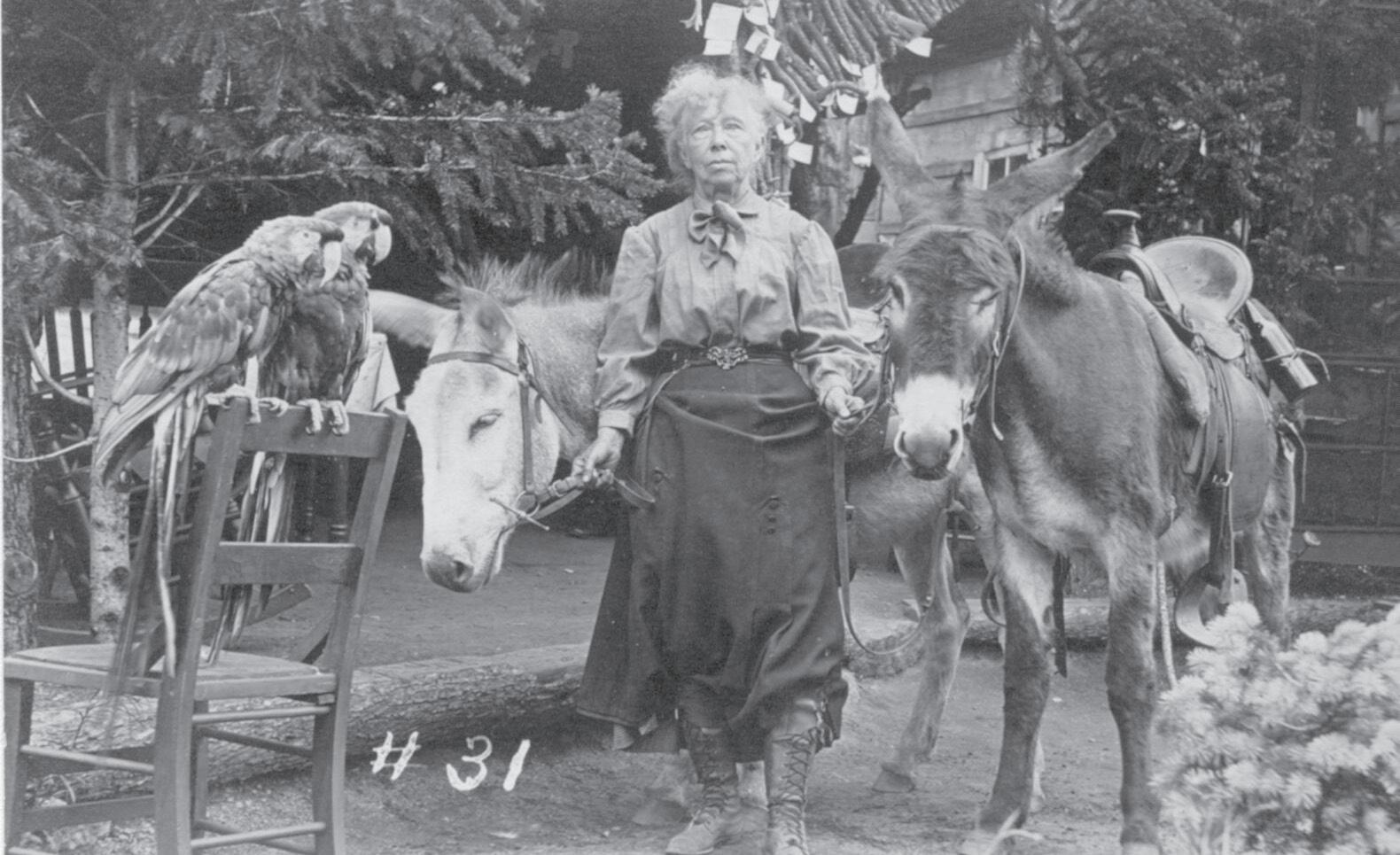

Historical Photos

Ellen Jack images provided by

Jane Bardal, Colorado Springs

Pioneers Museum and Pikes

Peak Library District

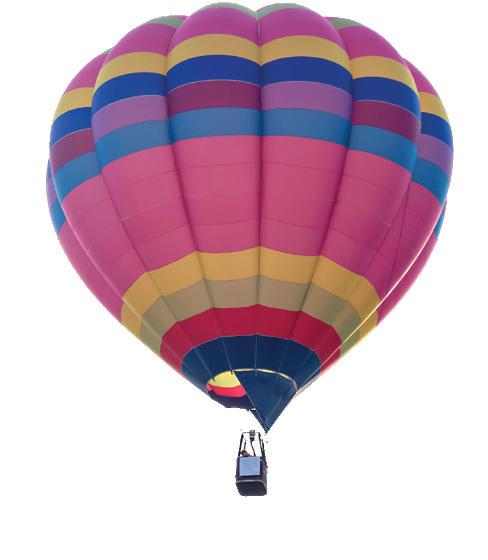

isLoveland residents John and Caroline Bell own the country’s only red, heart-shaped balloon. They call it Agape, an ancient Greek word that means the highest form of love.

It’s a solid fit for their new business, Love Hot Air Balloon Rides. Founded about a year ago, they cater to couples for engagements, weddings and anniversaries.

John Bell, a longtime airline pilot who first got a taste for flight as a naval officer, picked up a ballooning habit about five years ago. When it came time to buy his own balloon, he and his wife decided a heart shape would be fun since they were moving to Loveland from Highlands Ranch.

When they discovered the price, however, they opted for a conventional model. But

then John Bell was diagnosed with breast cancer and in 2022 had a double mastectomy.

“That made the decision to spend the money on the heart-shaped balloon (easier),” he says. “We both thought, ‘You only live once.’ It wasn’t the most financially sound decision, but it was based on emotion.”

Now, he’s cancer-free and a witness in the clouds to that highest form of love. As an officiant, he’s married two couples while on board the balloon and played a supporting role in several engagements and at least four anniversaries.

“We both are fortunate and blessed and want to share the love,” Bell says. “That’s the motivation.”

TEXT BY JENNIFER MULSON

The American balloonist with the most records is contemplating another one.

Troy Bradley believes he might be able to better the hot air duration record of 55 hours. He could make it 60 to 72 hours, he says, if stocked with propane. But the key to success relies on one thing: extremely cold temperatures. The colder it is outside, the better the fuel economy — as less hot air is needed to rise.

“We’d probably have to take off in Montana in subzero temperatures,” explains Bradley, a Denver native who lives in Albuquerque, N.M. “To be able to stay in the basket in subzero temperatures for

three days is a big part of that one.”

Bradley likely has the chops to do it. His 64 world records in distance, duration and altitude in all three types of balloons (hot air, gas and a hybrid of gas and hot air) and all 15 sizes of balloons prove his willingness to be uncomfortable, patient and pragmatic, as death is a possibility should the mission go awry.

“I’m usually not nervous,” he says. “I’m very calculated in risks. I’m not an adrenaline risk junky. It’s about doing it in a safe and sane manner. We wait for the right weather system so we have a high percentage of success.”

Bradley estimates that he’s spent 9,300 hours in balloons — more than a year of his life. He’s landed in thunderstorms and winds of 40 mph, and once needed to be rescued by helicopter in Canada after competing in a contest to see who could fly their gas balloon the greatest distance from Albuquerque. He and his wife won, going for two-plus days, but it came at a cost.

“We were the only ones to fly into Canada, but we flew so far there were no roads,” says Bradley, who got his commercial license at age 18 and has flown professionally for more than four decades. “We

Colorado Springs Labor Day Lift Off, Aug. 30 to Sept. 1, Memorial Park, coloradospringslabordayliftoff.com

landed safely but couldn’t get out. There was no way to drive anything in there. It was a 75-mile walk out. A helicopter took us back to town, then back to the chase vehicle.”

As the chief pilot for Rainbow Ryders, which operates out of Albuquerque, Bradley offers hot air balloon rides in Colorado Springs, Phoenix and Park City, Utah. He’ll be in town doing what he loves this summer during Colorado Springs Labor Day Lift Off, the annual festival held in Memorial Park. “I still love every morning of it,” Bradley says. “It’s hard to beat my office view.”

U R E W I T H

F U R N I T

Brian Hubel’s studio is teeming with power tools and carries the distinct scent of sawdust.

For nearly three decades, the self-taught craftsman has been fashioning original pieces here at the end of a gravel driveway in Colorado Springs. Wood is his medium, furniture is his art. But it’s the practicality of the works that he admires most.

“They are designed to be used,” Hubel says. “I want people to use them. They should be used, in my opinion. I want them to be passed down through generations and for multiple families to get value and use out of something that I built.”

Rusty handsaws hang on a wall of Hubel’s studio. Worn with dull teeth, they were from his grandparents’ farm in Nebraska. He credits much of his passion and drive to his grandfather, a handyman who had a small workshop.

“I was one of those kids that always would take things apart and try to fix them and put them back together,” he says. “We would go out there and play in the shop and just kind of tinker and play with scraps. And so I guess it’s just kind of my upbringing, and it stuck.”

On his 17th birthday, Hubel received a table saw from his mother. At the time, it seemed no more than a hobby. But that hobby quickly became a bigger part of his life.

It started as a way to pay the bills, working odd jobs in college and completing projects for the gymnastics facility where his wife worked. After earning degrees in

chemistry, biology and criminal justice, Hubel found himself at a career crossroad.

“What if I continued doing this?” he thought. Soon, he would open a workshop out of his parents’ garage. He would pursue the future he never expected.

“I actually never used any of my degrees,” Hubel says. “I went straight into building furniture and custom cabinets for a living, and I’ve been doing that ever since.”

Hubel’s furniture bears a subtle East Asian influence, with an emphasis on sleek lines and flowing limbs. That style has always been appealing to Hubel, but he struggles to understand why it sneaks into his pieces. His process, after all, is fluid. He often revisits designs while actively crafting. It’s a push and pull to get to the final product. Before sending off a piece, he signs and

dates it, marking it in black ink as an original.

Hubel is drawn to wood for a variety of reasons. He talks about its beauty. He talks about its uniqueness.

“I can cut it. I can carve it. I can burn it,” he says. “It still looks gorgeous.”

Hubel’s work has earned plenty of accolades, including first-place honors in the wood art category at the Scottsdale Arts Festival. He’s been featured in exhibitions at Tri-Lakes Center for the Arts and Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum.

Yet he often struggles to see himself as an artist.

“Most people tend to group me into that category, which is fine. I’m not offended by it,” he says. “But the functionality side, from my perspective, is far more important. The art side of it is great — I love being creative and figuring out a design and the engineering behind it — but it really does have to be a functional piece.

“For me, that’s what gives it purpose.”

As tongs transport hunks of raw pork and balls of meat through the metal fence, Sitka eagerly awaits on the other side. His white canines flash as he gobbles. Judging by his growls, he approves of his afternoon snacks.

“The better the piece, the louder his grumbles,” says Courtney Rogers, registrar at Cheyenne Mountain Zoo. “Sometimes if a piece is really good, he’ll run away and eat it in private.”

Mountain lions have no interest in your sweet potatoes and kale. They want meat, meat and more meat. They also enjoy bones and trout. When it comes time for an unpleasant husbandry task at the zoo, they receive whipped cream afterward as a thank you for participating.

Sitka came to the zoo with his sister in 2019 after they were found orphaned in Washington. He weighs more than 160 pounds, making him substantially larger than the normal 120-pound male mountain lion.

Cats share many behaviors across species, Rogers says. Mountain lions love a high spot to snooze, just like Sparkles does at home. They purr when they’re cuddled together. They love warmth, which is why their exhibit includes hot rocks and a heated cave. And they need to sharpen their claws, too, just not on the back of a couch. They opt for logs.

TEXT BY SETH BOSTER PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARK REIS

piano softly plays as a monarch butterfly dances outside the window near my cushioned seat, amid the greenery and the lake glistening from the sun rising in the blue sky above Cheyenne Mountain and The Broadmoor’s regal towers. Pink flowers catch my eye, finely arranged at the center of my linen-draped table. Across the Lake

Terrace Dining Room — the first dining room in the hotel’s illustrious, 107-year history — champagne is being poured from a bottle and orange juice from a small mug into the flute glasses of some of the hundreds of guests with reservations this Sunday.

Brunch has begun. Not just any brunch, but a brunch as legendary as The Broadmoor itself. An all-youcan-eat brunch worthy of the $105 price, say

The Broadmoor’s all-you-can-eat brunch runs from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. every Sunday. Cost is $105 ($50 for age 10 and younger). Reservations required at broadmoor.com/ dining/sunday-brunch

regular visitors and others celebrating special occasions. A brunch worthy of the Forbes FiveStar and AAA Five-Diamond awards that this Colorado Springs institution has maintained longer than any resort in the world.

The buffet has apparently been served for as long as those distinctions have been awarded, both dating to the 1970s. The Broadmoor’s historian, Cynthia Leonard, showed me a photo from back then, capturing what appeared

to be a long table of seafood before servers in suits.

“A little simpler than the extravaganza we have now,” Leonard observed. Into the extravaganza I go. Where, oh where, to begin?

Surely at a showstopper: an ice sculpture overlooking a bed of ice for oysters, plump shrimp and equally plump crab meat ready for plucking from the claw. Butter simmers in

a neighboring pot.

Surf and turf, I’m thinking, as I move on to a man carving prime rib. Then I move to another attendant preparing eggs benedict.

Smiling attendants beckon all around. One carves bourbon-glazed ham; another makes omelets; another pours buttermilk on a griddle for pancakes; another rolls sushi; another sears chicken to place atop pasta coated in a lemon caper cream sauce.

Every pasta needs a salad: the signature Broadmoor Caesar, which is close to the ceviche station. Two choices here: one with tuna, mango and a coconut lemongrass dressing, and another with shrimp, cilantro, garlic, tomato, lime and avocado, beside a bowl of more shrimp for the taking.

The choices go on and on.

Charcuterie is next to dripping honeycomb from The Broadmoor’s own bee farm. The biscuits are next to the gravy, which is next to the pecan sticky buns. Other baked goods, done the French way of the hotel’s French-born pastry chef: croissants and a sugary brioche bun that

oozes with lemon curd. The bagels are over by the fresh salmon, smoked trout, cream cheese, onions and capers.

Over here: herb-roasted salmon on orzo and red sauce. Over there: green chili casserole. Here’s the loaded mac and cheese, which I’d heard was a staff favorite, along with the fried rice. And there’s the jambalaya and the gyros and the slow-braised kale and on and on.

And on to dessert.

For a last yet perhaps main event, a chef cuts a banana into a hot pan of caramel and rum that is poured over homemade ice cream. I’m also eyeing a piña colada parfait, and also the bread pudding, and also a slice of chocolate fudge cake, and also a round key lime tart, and also a rectangular strawberry-hibiscus cake — among other colorful, glossy confections.

“We want everything beautiful and eye-catching,” Sydney Braden, the sous chef in the bakery, had told me. “We try to make sure it’s grand.”

Braden is among dozens of staffers who make The Broadmoor brunch happen.

“It’s a big production,” says Nicole Wilson, the Lake Terrace Dining Room manager.

It starts Wednesday and Thursday, as the team gets a good idea of reservation numbers for the coming Sunday. Much of the fruit and vegetable cutting, sauce and garnish mixing, marinating and other prep work happens before Saturday night, says Bethany Fahey, the chef who’s overseen the process over the years.

“They’ll fire the hams starting at 11 at night,” she says, “and then just go low and slow all night until the next team comes in at 4 in the morning.”

That team gets going on the prime rib, bacon and sausage, and the oysters that need cleaning and shucking. Behind the main kitchen is the bakery, where work also continues hours before dawn.

By the time others arrive around 7 a.m., a diagram has been posted, with names of servers assigned to table sections and other names written by buffet stations. Others are running food and replacing tongs and spoons every 10 or 15 minutes.

“It’s all teamwork,” says Daniella Gonzalez, junior sous chef and supervisor. “We all come together as a team and make it happen every Sunday.”

This Sunday morning finds her high-fiving teammates while moving briskly through the kitchen, like the chef in charge. Luis Alcantara is not above menial tasks; here he is whipping up some hollandaise, dipping his spoon for a taste before pouring it into three jars.

“For a VIP,” Alcantara says with a smile. “They wanted three mason jars of hollandaise. Whatever they want!”

The Broadmoor brunch is more than anyone could possibly want. However refined, I even notice specialties for children: funfetti pancakes and waffles and a purple parfait topped with Fruit Loops.

Kids are given a penny as they leave. Outside the dining room, there’s a fountain for wishing.

I meet a boy tossing his penny now. “I can’t say my wish!” he says. I make a guess: a return trip to brunch.

Mexican barbecue spot integrates south-of-the-border flavor profiles

hen Manny Barella was growing up in Monterrey, Mexico, barbecue was part of daily life.

The smell of charcoal hung in the air wherever he drove on weekends. On Thursdays, his family, like everyone else he knew, would grill carne asada and play dominoes.

On Saturdays, he and his friends would cook together after playing soccer.

Asada is about “cooking with an open fire,” and it’s deeply ingrained in the culture and the community, Barella explains. “A boy becomes a man when he’s able to get the charcoal going without his dad.”

But the chef didn’t see that style of cooking represented in his adopted home of Denver, where Tex-

as–style barbecue typically reigns. So Barella — who previously led the kitchen at the now-shuttered Bellota and also finished in the top five on season 21 of Bravo’s reality television series Top Chef — decided to start his own Mexican barbecue joint. He teamed with local pitmaster Patrick Klaiber, and Riot BBQ opened in the Overland neighborhood in June.

The menu is familiar, with meats such as an ultra-tender smoked brisket, coffee-rubbed smoked turkey and pulled pork served by the half-pound along with accompaniments such as paprika-dusted potato salad, gooey mac and cheese, and banana pudding.

But the south-of-the-border influences are also present: Coleslaw becomes a macha slaw inspired by

salsa macha, a chile-forward Mexican condiment. The cornbread incorporates the zest of jalapeños and the creaminess of esquites (Mexican street corn); fire-roasted corn is added to the bread batter and a charred corn crema “emulates the ashes of corn husks” that Barella grew up with. Brisket tacos are topped with avocado crema and folded into bison tallow tortillas from local producer Raquelitas Tortillas.

“It’s the perfect marriage of Mexico and Texas,” Barella says. “But it’s not Tex-Mex.”

Klaiber began smoking meats at the age of 16. “I just thought it was so cool — meat and fire,” he says.

Most recently, the self-taught pitmaster led the crew at AJ’s Pit Bar-B-Q to a Bib Gourmand nod

from Michelin Guide in 2023. The eatery shuttered in March, and Riot took over the industrial space with its communal tables and sizable back patio.

A new liquor license will add a margarita, beers and more to Riot’s menu. But warm days (or a spicy bite) may best be eased with a glass of hibiscus aqua fresca topped with a splash of lemonade. Barella calls it a Mexican Arnold Palmer.

More daily specials and more Mexican influences are also coming. Barella wants to play around with smoked goat — as suggestive of Monterrey as lobster is to Maine — and beef barbacoa tacos.

In merging Barella’s heritage with the traditions of American barbecue, Riot BBQ is creating a new flavor profile for diners to discover.

Five other Denver-area BBQ spots worth a visit

• Pit Fiend Barbecue: Michael Graunke and Juan Pablo Llano learned about smoking meats while on the job, and their live-fire cooking has fueled an extensive fan base. Pit Fiend’s menu includes unique offerings such as pulled lamb, a sausage of the week and vegan smoked mushrooms.

• Smok: A 2024 Michelin-recommended eatery, Smok is a casual, counter-service spot in The Source Hotel where diners can find high-quality barbecue — burnt ends, smoked jalapeño-cheddar sausage, pork belly — and an extensive menu of sides and other belly-filling dishes (such as Nashville hot chicken). A second location can be found in Fort Collins.

• Post Oak Barbecue: A favorite stop on the busy Tennyson Street shopping strip, Post Oak serves Central Texas–style barbecue (owner Nick Prince, a self-trained pitmaster, hails from the Lone Star State), which translates to pork ribs, homemade sausage, jalapeño-bacon mac and cheese, and Texas sheet cake. Last year, Food & Wine declared that the eatery serves the best barbecue in Colorado.

• Roaming Buffalo Bar-B-Que: There’s no such thing as “Colorado barbecue,” but if there was, Roaming Buffalo — which recently celebrated a decade in business — would be the place to get it. The small, turquoise-hued eatery features Colorado bison back ribs and pulled Colorado lamb alongside more traditional ‘que options.

• Wayne’s Smoke Shack: You’ll need to set your alarm to scoop up the beef brisket, St. Louis ribs, hot-smoked catfish and peach cobbler at this Texas-style joint in Superior, which only slings meats by the pound on Fridays and Saturdays, from 11 a.m. until sellout.

TEXT BY SETH BOSTER PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARK REIS

Spread out. It’s a common refrain among land managers and advocates all too aware of overcrowding at Colorado Springs’ premier parks and open spaces.

One should take the advice to heart, spreading out to the hills and plains beyond. The best hikes on the city’s outskirts? Here are eight:

Palmer Lake Reservoir Trail

From Colorado Springs, you don’t have to go far to feel like you’ve reached some hidden alpine lake. This trail affords something close to that experience — surprising for the trailhead just below a neighborhood in the town of Palmer Lake. The steep path leads to a small reservoir before a larger one between the forested slopes.

FYI: ~4 miles round trip, moderate-difficult; no dogs

Spruce Mountain Open Space

Near Larkspur, the flattop mountain is an enticing, distant sight from Interstate 25. A trail climbs and loops around the upper woods and bluffs overlooked by the Palmer Divide and Rampart Range. Or take the path less traveled: Eagle Pass Trail runs out and back from the parking lot, leading to a scenic gravesite.

FYI: ~5 miles round trip, moderate

Aiken Canyon Preserve

Colorado 115 runs south to where the city feels distant amid canyons decorated by sandstone. At Turkey Canyon Ranch Road, turn right to immerse yourself deeper in nature. The road leads to this quiet preserve and loop trail that ascends to views of the distant Spanish Peaks and Sangre de Cristo mountains.

FYI: ~3.5 miles round trip, easy-moderate; no dogs

Fountain Creek Regional Park

Residents of Fountain are grateful for this melodious place of birdsong and running water. They are especially grateful on hot days; creekside cottonwoods provide shade. They are grateful, while people in Colorado Springs too often miss out. Start from Fountain Creek Nature Center, where wetlands and Pikes Peak vistas await.

FYI: Variety of flat trails, easy

The masses know of Colorado Springs’ Section 16 trail in the city’s southwest mountains. Fewer know of Black Forest’s Section 16 trail. They are similar in name — for a historic sectioning of land use — but otherwise very different. In Black Forest, you swap the mountains for the dense, charming pines of the area.

FYI: ~4 miles round trip, easy-moderate

The plains around Calhan seem like the place to escape crowds. Not necessarily so at the Paint Mines, this geologic dreamscape that is no longer a hidden gem. It’s still a gem, however — a one-of-a-kind expanse of multi-colored rock. For inspiring solitude, try visiting on a weekday.

FYI: Variety of flat trails, easy

Green Mountain Falls is a hiking paradise, and Catamount Trail might be the crown jewel. From your parking spot in town, it’s an uneventful start up Hondo Avenue to the trailhead. But the rewards soon follow: a waterfall, scenic switchbacks and a wildflower meadow aptly named Garden of Eden before heading onward toward Pikes Peak Highway and South Catamount Reservoir.

FYI: ~6 miles round trip, moderate

Hiding up Park Street in Cascade, people in the know consider this trail to be a perfect alternate to Barr Trail. Like that trail to the top of Pikes Peak, Heizer offers a steep challenge and options for farther-flung adventure in Pike National Forest.

FYI: ~7 miles round trip to the “T” trail split at French Creek, moderate-difficult

There’s much to admire in an aspen tree. Its expansive presence for one; stands of aspen cover 5 million of Colorado’s acres — that’s 20% of the state’s forested land. Its captivating capacity for tree song for another; its fluttering leaves deliver a notorious whisper, or sizzle, as they shimmy in a breeze.

The unique way an aspen photosynthesizes impresses, too; it’s the only tree whose bark can spin sunlight into sugar. Most wondrous, maybe, is its genealogy. From a single seed can grow an entire clonal colony.

Aspens have been used for medicines and messages, lauded in poetry and literature. They attract droves of

hikers and leaf peepers to Colorado each year to experience their towering, quaking beauty.

But above all, the trees’ papery white bark and radiantly golden fall leaves are a siren call for artists.

“I love aspen trees,” says Emily Fair, a painter who coowns the eclectic 45 Degree Gallery in Old Colorado City. She’s inspired by the way their crisp white trunks stand out against a field of greens and browns, the personalities they seem to take on. “And, of course, the golden leaves in the fall — they look like sparkling coins or sequins against the forest.”

Standing among aspens in the fall is “magical,” Fair

says, “almost like you’re in a snow globe but it’s showering golden leaves on you ... I can’t get enough of it.”

When Fair moved to Colorado Springs in 2003 and started working at a gallery, she didn’t understand artists’ or collectors’ fascination with aspens. The trees she saw nearby were scrawny and unimpressive.

That was before an autumn hike on McClure Pass, where Fair took in a magnificent grove resplendent with tall, thick trees crowned in gold and quaking in the wind.

“Then I got it, and then I understood the fascination,” she says.

Fair is now one of many Colorado artists striving to recreate the wonder and beauty of aspens through painting. In some of her works, the trees sit atop geometric patchwork colorscapes that use the stark blackand-white trunk to provide a focal point for the restless, searching eye.

People might not walk into her gallery looking for an aspen painting specifically, but visitors are often “surprised and delighted by the nontraditional approaches our artists take to portraying such an iconic Colorado tree,” she says.

Artist Carl Bork, who owns Bork & Watkins Gallery in Salida, was a figurative artist — depicting people mostly — when he moved west and was struck by the human-like presence of aspens. He’s been painting them ever since.

Painting outdoors recharges his inspiration, and he thinks aspens can present a multitude of ideas and feelings through art. “They all have their own unique look, whether the twisty ones or the great up-and-down ones, the big ones, how knotty they are, and you can play with the composition and how you lay them out in the scene,” he says. “There’s really a lot you could do with them.”

That’s something he pointed out to fellow painter Laura Reilly, a landscape artist who calls “Colorado” her favorite color and paints out of a hole-in-the-wall studio and gallery a few doors down from Fair.

Paintings exalting aspens adorn her walls, with vivid golden hues in textured layers evoking the trees in their autumn attire. Other paintings present the aspens more softly, framing Mt. Silverheels near Alma in shades of green; gently suggesting a path through a sunlit meadow.

Reilly says she is captivated by the way aspens change:

from location to location, season to season, grove to grove. By the way they seem to turn the very light around them golden in the fall, when their leaves announce the season with their recognizable rattle. And by the way these identical trees show off their variations.

“Even though they’re all aspens, in terms of how sparse or compact they are, how tall they are, how delicate or dense the foliage is, they’re all different,” Reilly says.

Those differences stand out to Reilly as she quietly observes a scene, the landscape slowly opening up for her as she sketches what she sees and, somehow, what she feels.

She calls her aspen paintings souvenirs — not in the way of key chains or postcards but in how they can capture and hold a sense of place. “I think that people recognize themselves in paintings, and what they recognize is their experience,” Reilly says.

It could explain why aspen paintings are marketable: they appeal to anyone who has felt that wonder at the natural world, a feeling that speaks to them through a painting even if they haven’t stood in that exact spot.

And why artists, despite the trees’ ubiquitous presence on canvas, continue to paint them.

Maroon Bells outside Aspen, Kebler Pass near Crested Butte and Rocky Mountain National Park are staples for viewing aspens. Here are some other sites where artists have immersed themselves in these inspiring trees.

Laura Reilly: Million Dollar Highway between Ouray and Silverton offers stunning stops from which to view aspen groves. Reilly also recommends the area along Chalk Creek near Mt. Princeton. She’s painted the aspens on Cottonwood Pass many times and loves to see them backed by snowy peaks. Closer to Colorado Springs, Reilly enjoys heading to Teller County for Lovell Gulch Trail, Rampart Range Road and Mueller State Park, where some of the tallest aspens stretch.

Emily Fair: Taking Huntsman Ridge Trail at the top of McClure Pass west of Aspen will allow visitors to experience the best of autumn aspens. Fair also enjoys Horsethief Park Trail south of Divide, a hike her family takes every fall to see the changing colors.

Carl Bork: Fourteener Mt. Shavano outside Salida has been a go-to spot for more than a decade.

I invite everyone to visit and enjoy traditional dishes from Thailand, and innovative Street-style foods! There is something for everyone at the table, with new options each season. My goal is to have you walk away smiling!

Chef Suwanna Meyer

Art comes in many forms. Whether it’s our picturesque mountain setting or our legacy of longest running Five-Star, Five-Diamond service, The Broadmoor is sure to take your breath away. Offering an array of award-winning restaurants, a Five-Star spa, championship golf courses, and adventurous activities like zip lining, The Broadmoor is an experiential destination like no other.

Find your inspiration today at Broadmoor.com.

This annual tour doesn’t require tickets even though it’s sure to draw incredible crowds. It’s aspen season in Colorado, and it never disappoints. Radiant hues of gold, red and orange will soon paint forests across the state as leaves begin to change color.

While it’s not hard to find the striking scene, some places are better than others. Here’s a look at six mountain passes where you’re bound to be awed — even if you don’t leave your vehicle.

Boreas Pass: South of Breckenridge, follow the pavement until it turns to dirt. Soon, the road is lined with aspens. It eventually crests near 11,000 feet at the remains of an old railroad.

Cottonwood Pass: From Buena Vista, head west and just follow the yellow brick road. Swaths of golden aspens blanket the Collegiate Peaks, providing panoramic views of fall at its finest.

Cuchara Pass: The Highway of Legends is indeed legendary, particularly this time of year. Leaf peepers can start in the charming town of La Veta or near the New Mexico border in Trinidad.

Guanella Pass: This scenic route out of Georgetown might prove slow going — with plenty of twists and turns — but you won’t want to be in a hurry with the wondrous show that awaits.

Kenosha Pass: If time is of the essence, look no farther than this drive near the Front Range. Take U.S. 285 out of Denver and quickly replace big city bustle with big mountain beauty.

Red Mountain Pass: Yes, we’ll say it. We’re saving the best for last. That’s what happens when you take fall foliage and add the rugged San Juans. See the show from Ouray or Silverton.

NATHAN VAN DYNE

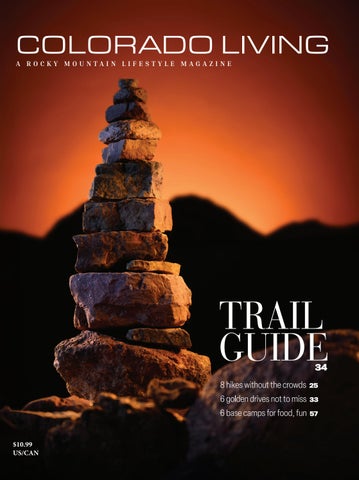

No rock is equal, just as no stack of rocks is equal.

Anyone who has explored Colorado’s outdoors long enough has seen them: cairns, derived from the Scottish Gaelic term “carn,” meaning pile of stones. It’s a term that has traveled space and time to this state’s Rocky Mountains, which are very rocky indeed. Where trails are less obvious amid the rubble, cairns lead the way.

Wrote Graham Ottley, education director of Colorado Mountain Club: “These stone markers originated in Scotland but have become essential navigation tools in Colorado’s alpine environments, particularly above tree line

where trails are difficult to follow.”

Sometimes, however, cairns lead the wrong way. Or they are built for fun, for decoration, serving no purpose but aesthetic, as some see it. Others see cairns as eyesores — “cairn Karens,” as Alex Derr has heard critics called.

Derr runs The Next Summit, a blog that aims to be an educational resource on Colorado’s mountains. Another popular resource is 14ers.com, a site focused on the state’s 14,000-foot peaks where Derr has seen forums flare over the topic of cairns.

If ever the image of a conical pile of rocks was charming

TEXT BY SETH BOSTER PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARK REIS

and idyllic, inspiring dreams of alpine wonder, that might not be the case today.

“They are sort of a good symbol or like a metaphor for what’s happened with mountaineering in Colorado and fourteener culture really over the past 100 years,” Derr said.

A hundred years ago, summit seekers did not have 14ers. com, downloadable maps and GPX files. People then likely had cairns, for which many of today’s peak baggers are still grateful, reassured by directional help that is physical rather than digital. And then there are those who see

cairns infringing upon Leave No Trace, the set of standards at the heart of those online debates.

“There are, in my view, three different types of cairns,” said Lloyd Athearn, executive director of Colorado Fourteeners Initiative (CFI).

CFI constructs and maintains summit paths deemed sustainable. In doing so, CFI abides by U.S. Forest Service specifications — including guidelines for cairn building. Those are outlined in the federal agency’s 307-page Trail Maintenance and Construction Notebook.

One might stack rocks shin- or knee-high, but not one

authorized by the Forest Service.

Reads the notebook: “Cairns are not a few stones piled one on top of the other (sometimes called a rock duck), which can easily be kicked over.”

Per the official blueprint, cairns should measure 3-4 feet wide and stand 4-6 feet tall, with “a 6 1/2-foot guide pole in the center to distinguish the cairn from other piles of rock or snow-covered mounds.”

CFI builds these to keep hikers undoubtedly on the right route.

Otherwise, “people might be cutting across super saturated soils with fragile plant cover,” Athearn explained, “and all of a sudden you can get a huge amount of impact.”

Then there’s a second type of cairn — “many that are unofficial markers,” wrote Ottley, with Colorado Mountain Club. Those “rock ducks,” those crafted by the everyday hiker, “should be treated with appropriate skepticism,” he

wrote. Maybe they lead the right way, maybe they don’t.

A third type of cairn could be called “ornamental,” to borrow a word from the National Park Service (NPS).

Those pleasing to one viewer and detrimental to another.

“A bit like littering using a natural object,” Athearn said. “Some people get super offended by them, and other people think they’re the coolest thing in the world.”

They “can often become a problem for hikers who think they are supposed to follow them,” reads an NPS article.

According to the agency, cairns are “carefully maintained” by some parks while other parks ban them.

“However, they all have the same advice,” the article reads. “If you come across a cairn, do not disturb it. Don’t knock it down or add to it.”

That, by the agency’s account, is following Leave No Trace: “Moving rocks disturbs the soil and makes the area more prone to erosion. Disturbing rocks also disturbs fragile vegetation and micro ecosystems.”

Proponents insist proper cairns uphold other ethical tenets: keeping people on the trail and thus respecting plants and wildlife. However obnoxious and unnatural to some, the benefits of those massive, Forest Service-authorized cairns are “significant,” Ottley wrote. “They enhance safety by remaining visible even in winter conditions, require no technology to function and connect modern climbers to historical traditions.”

Cairns have been traced to prehistoric traditions. Civilizations and tribes around the world stacked stones as part of rituals, to mark burials and to commemorate sites. When construction crews come by cairns, the law requires archaeological review.

Cairns were also built for hunting purposes, according to a 2017 thesis out of Colorado State University.

The thesis was based on previously documented game drives along Rollins Pass, where projectile points had been dated thousands of years ago. Several cairns have been among other rock structures studied high on the pass outside Winter Park, the thesis explained. Several rock walls and “cairn lines” also helped direct man and beast to certain “kill zones” and harvesting places.

It was research that caught Derr’s curiosity. He’s broadly

curious about cairns, about how they’ve come to represent this era of mountaineering.

“In the old days, that was the route; early 1900s, that’s how you did it, and it was a small community of people,” he said. “But with the way it is today, everybody is building cairns everywhere, and it kind of proves the point that things have changed, and we also have to change the way we manage that.”

The internet has spelled “a bizarre phenomenon,” Athearn observed. “With more information, it seems that intuitive, navigational abilities have not been developed as well.”

Cairns can help, he said, and they can also lead lessskilled people astray. Even a well-traveled climber such as Athearn has met the conundrum.

He was once high on Wyoming’s Grand Teton alongside a partner. “All of a sudden, man, we could not figure out where the route was,” Athearn recalled.

They cautiously followed one cairn. They cautiously followed one after another until they felt caution give way to a much different, most welcome sensation: “a certain level of relief,” Athearn said. And then success.

TEXT BY DEBBIE KELLEY PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARK REIS

hen considering a picnic, it’s imperative to think beyond uninvited ants that have food on the brain. Besides, dictionary definitions of picnicking that focus on the “outdoor eating” part just don’t capture the magnanimous essence of the experience.

“Picnicking invites us to slow down and connect,” says Kiara Richardson, a cotillion director for Jon D. Williams Cotillions. For 76 years, that nationwide program based in Denver has educated children in Colorado Springs on modern etiquette, social confidence and respectful behavior.

“Whether it’s a date, a family meal or a gathering of friends, dining outside reminds us that etiquette isn’t about being fancy — it’s about being thoughtful,” she says. “And that’s something everyone can practice, no matter the setting.”

The thought counts in many ways, though, when sharing a meal on a traditional red checkered cloth or a comfy blanket. Or while huddled under a park pavilion or on a creek-side bench.

While picnicking, children can be, well, children and adults can adopt the joyous, carefree attitude

of youth as they savor the feel of grass beneath their bare feet, fly a kite or toss a Frisbee.

And if someone spills a drink or drops some food, that’s not a problem.

Manners should not be forsaken in the wild, however, Richardson says.

In cotillion classes, “we encourage students to treat every outing as a chance to show kindness, courtesy, consideration and respect — even when barefoot in the grass.”

Food, of course, plays a leading role in picnics and should not be overlooked, says Logan Anderson, a former executive chef at The Broadmoor who works the front of the house at The French Kitchen. The business in northern Colorado Springs features a French bakery, café and boutique.

Must-haves for the picnic basket, he says, include fruit, bread, cheese, cold cuts, a salad (leafy, pasta or vegetable such as corn or cucumber), chips and dessert. Don’t forget to pack the bubbly for a romantic time.

“I see picnicking as an activity that is initiated by the desire to be outside and is improved and enhanced with the presence of food,” Anderson says. Some prefer to set up tabletop grills for a barbecue or pick up fried chicken and bring deviled eggs,

baked beans and potato salad.

Whatever is on the menu, picnics build memories and should be enjoyed as often as possible, Anderson says.

“Many people strive harder than ever to maintain a playful lifestyle and keep the social and outdoor spirit alive,” he says. “(They) make efforts to escape — if only for an afternoon — the sedentary lifestyle that so many of us live nowadays.

“Picnicking can serve as a great reprieve from the hustle of everyday life.”

That’s how the practice originated during the Middle Ages, when hunters sought respite from their work and ate outside.

The concept became fashionable in the 1700s, as French and then English aristocracy partook of elegant meals served outdoors. The modern-day picnic table was introduced in the early 1900s.

An ideal spot for a picnic in contemporary times is an outdoor concert venue, and there are abundant choices throughout the Pikes Peak region. Music and food have paired nicely this summer on the grass in front of the recently remodeled Manitou Springs Library, branch supervisor Karin Swengel says.

Many attendees of the Lawn Concert Series “love to come and picnic as a family, and there are lots of good snacks and good music,” she says. Plus, “dogs are especially happy to be there.”

• Do bring enough to share if you are joining a group — it’s a thoughtful gesture that sets the tone for generosity and hospitality.

• Don’t forget to clean up your space — leaving the area better than you found it shows awareness and respect for others.

• Do consider your setting and company — a romantic picnic may call for quiet connection while family-style gatherings are great for playfulness and group participation.

For children, a picnic is a wonderful way to practice:

• Polite conversation while using “please” and “thank you” when sharing food or drinks.

• Waiting their turn in line at the cooler or picnic table.

• Helping with setup and cleanup — which builds responsibility and teamwork.

JON D. WILLIAMS COTILLIONS

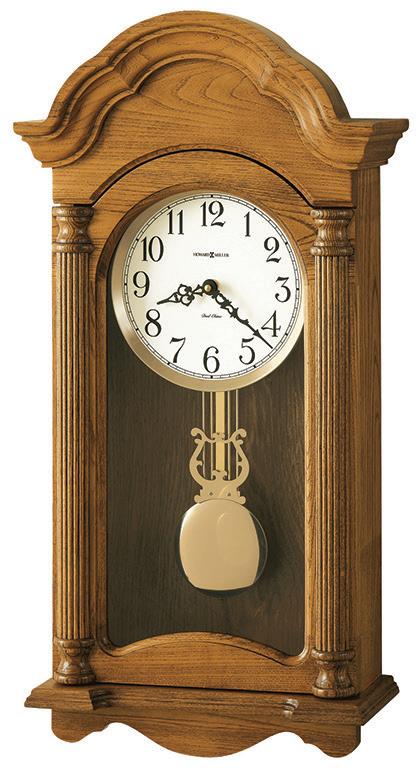

We carry clocks for every room and every budget. From heirloom quality mechanical chiming clocks, to room defining gallery sized wall clocks, or just simple timepieces, we have the right clock.

• HOWARD MILLER HANNES WALL CLOCK

A steampunk wall clock like this is a standout — and it’s also incredibly easy to assemble.

• HOWARD MILLER AMANDA WALL CLOCK

This traditional wall clock with pendulum exudes an old-world quality, yet offers robust functionality. Its the perfect addition to any home or office.

• HOWARD MILLER EARNEST WALL CLOCK

Features a Hampton Cherry finish on select hardwoods and veneers to complement your home decor.

7 N. Circle Drive, Colorado Springs, CO 80909

TEXT BY SETH BOSTER

U.S. 36 escapes the bustling Front Range for the wilds of Big Thompson Canyon — that cool, winding drive between rugged, imposing walls. Soon, the road rises. Those walls fall below. And a quintessential Colorado view emerges.

Rocky Mountain National Park’s jagged peaks march across a big sky, looming above Lake Estes and the town that would expand after one man’s visit in 1864. His name was William Byers, the founding editor of the Rocky Mountain News who was drawn to this valley.

“Eventually this park will become a favorite pleasure resort,” Byers remarked.

Right he was. But how to pack all the pleasure of Estes Park into two days?

Don’t rush to town without a stop at Colorado Cherry Co., the nostalgic, red-roof staple along U.S. 36. The shop sells fruit pies for now and later. We also suggest the hearty hand pies stuffed with meat and veggies (bison chili is our favorite). After all, you’ll want to fill up before a full day of fun.

You think you’ve caught the best view on the way into town, but no. Make your way to Estes Park Aerial Tram The gondola soars 1,000 feet for a perspective that has captivated visitors since 1955.

Another generational staple: Fun City. The amusement park is for the kids and kids at heart, with gokarts, a spinning coaster, bumper boats, a bungee jump, miniature golf, a giant rainbow slide and more.

Now on to the neighboring fun city: downtown Estes. Elkhorn Avenue is a whimsical wonderland of gift shops, boutiques and galleries. And lots of sweets. One window displays a vintage machine pulling colorful taffy. That’s The Taffy Shop, beloved since 1935.

Also beloved: Antonio’s Real NY Pizza. New York is in the name, and thin crust is indeed the specialty. But locals rave as well about the thick, Sicilian hunks.

Pizza and a movie — a fitting, nostalgic end to a nostalgic day. See what’s showing at Historic Park Theatre

It’s the day for the national park. But not before a proper fuel-up at Notchtop Bakery & Cafe If you’re in a hurry, you’ll find an array of freshly baked goods in a case. But you’ll be tempted to sit down for a breakfast burrito, eggs benedict or cinnamon roll French toast.

Through mid-October, Rocky Mountain National Park requires a timed-entry reservation made in advance. If you don’t have a reservation, you can enter before 9 a.m. or after 2 p.m. and access all of the park except the Bear Lake Road corridor.

Maybe you’ve got a hike in mind, a destination lake or waterfall. Maybe you’re here for the iconic drive: Trail Ridge Road crests above 12,000 feet to the Alpine Visitor Center. Or maybe you’re here for the wildlife: elk, moose, deer and more call the park home.

After hours of sightseeing and adventure, nothing hits the spot like a beer. Rock Cut Brewing Co. is a local favorite. As are the food trucks regularly parked outside.

Rocky Mountain National Park is, of course, the most iconic destination in Estes Park, but The Stanley is a close second. Whether you booked a room at the hotel or not, book one of the tours: the historic day tour or The Shining Tour, so named for the Stephen King classic the hotel inspired.

The Stanley is the perfect place to raise a glass in celebration of the trip. Splurge at Cascades Restaurant, with a renowned whiskey bar and Colorado fare on the fancy, hearty side. The bacon-wrapped meatloaf is recommended.

States Olympic & Paralympic Museum, visit history—you experience it. speed. Feel the thrill of competition. Get inspired by the journeys America’s greatest athletes.

more than a museum—it brings history, innovation, and inspiration to life.

If you haven’t discovered Colorado wines yet, it’s probably time for a road trip.

The state is now firmly entrenched on the wine map, and you’ll be deliciously surprised by the variety and complexity.

In 2018, Colorado was listed among Wine Enthusiast’s top 10 wine getaways. But the wine scene started here in 1890, when the first vines were planted on the Western Slope. In less than two decades, the state had harvested more than a million pounds of wine grapes.

The scene has only grown, as Colorado now boasts more than 170 licensed wineries, including 25 cideries, 16 meaderies and a sake producer.

Colorado Mountain Winefest is Sept. 20 at Riverbend Park in Palisade. The festival began in 1992 and is the showcase event for Colorado Wine Week, which runs Sept. 16-22 and includes Colorado wine-focused opportunities statewide, many of which are free to attend. coloradowine.com

The state’s two federally designated American Viticultural Areas are the Grand Valley, along the Colorado River between Palisade and Grand Junction, and the West Elks, along the North Fork of the Gunnison River between Paonia and Hotchkiss. Together, they produce 90% of Colorado’s wine grapes.

These wineries are the highest in the Northern Hemisphere and among the highest globally, and they thrive thanks to plentiful sunshine, cool nights and low humidity.

But the Grand Valley offers much more than award-winning wines. There’s outstanding dining (with most restaurants using locally sourced and grown products), a lavender farm and a long list of charming communities.

Colorado National Monument outside Fruita is a stunning wilderness park, with 23,000 acres of colorful canyons, towering monoliths and high-desert landscapes.

Nearby, some 100 mustangs run freely among the

plateaus and rock canyons at Little Book Cliffs Wild Horse Range. Then there’s Grand Mesa, the world’s largest flattop mountain, and its 300-plus alpine lakes.

Palisade, 12 miles east of Grand Junction, is known as Colorado Wine Country, home to two-thirds of the state’s vineyards. This is no uber-posh Napa, however. Here, the wineries, open year-round, are friendly and unpretentious. Most sit so close that folks can visit several by bicycle or on foot. Or they can opt for shuttles, limos and horse-drawn carriages. Even the library in town sports a grape arbor.

Some of the standout wineries include:

• Carboy Winery at Mt. Garfield Estate, with 11.5 acres of high-elevation vineyards planted with varietals such as Albariño, Teroldego and Cabernet Franc, as well as a recently launched sparkling wine. Carboy hosts events including a concert series, vinyasa yoga and a book club.

• Colterris Estate Winery, the state’s largest fully estate-grown winery. Two years ago, it expanded its

footprint by acquiring Plum Creek Cellars, Colorado’s oldest continuously operating winery. Colterris has since transformed it into a tasting room where visitors can sample legacy Plum Creek bottles as well as Colterris’ new Plum Creek Heritage line.

• The Ordinary Fellow, which offers French-inspired wines from regeneratively farmed vineyards in Colorado and Utah. It continues to push handson winemaking, focusing on sustainable practices at its high-elevation vineyards, including the Box Bar Vineyard situated above Yucca House National Monument south of Cortez.

• Sauvage Spectrum, an innovative winemaker that’s known for Devil’s Prey, a bourbon barrel-aged red wine developed with Peach Street Distillers.

• TWP (Twee Wingerd Plaas) Winery, which produces small-batch, handcrafted wines inspired by South African traditions and made with estate-grown Colorado grapes. This harvest season, it will have new releases, including Tinkering with Pink rosé, Primitief Primitivo and Cab Franc.

In a naturally beautiful state, Coloradans don’t need a reason to celebrate. And yet there are several — some of them surprising (and maybe creepy). Here’s a look at some upcoming festivals:

Pueblo Chile & Frijoles Festival, Sept. 19-21

The star, of course, is the famous hot pepper that exclusively grows in the fields outside Pueblo. But that’s not all you’ll find over the weekend. Look out for the chili and salsa competitions, hot air balloons and costumed chihuahuas.

La Junta Tarantula Fest, Sept. 26-27

Creepy to some, fascinating to others — including camera-wielding admirers who flock to see furry male tarantulas skitter en masse during mating season. La Junta invites you for a weekend of parades, food vendors and tours.

Elk Fest, Estes Park, Sept. 27-28

Many know it to be the best time in Estes Park: The elk rut brings a wildlife soap opera to the town and neighboring Rocky Mountain National Park, as bugling bulls vie for cows. Bond Park becomes a scene of music, food and performances. And, yes, probably elk.

Cedaredge Applefest, Oct. 3-5

In far western Colorado, rugged mesas loom large and fruit grows plentiful. That includes the orchards in Cedaredge, which has hosted this event for 46 years now. Go for the apples; stay for the music, beer, antique cars and chili cook-off.

Great American Beer Festival, Denver, Oct. 9-11

Colorado Convention Center is a mecca for craft beer lovers, who every year make the pilgrimage to the nation’s biggest brew fest. Necklaces of pretzels and snacks sustain them on a fun- and suds-filled adventure, tasting from some of the hundreds of breweries.

SETH BOSTER

In a game of word association, Palisade belongs with peaches.

The juicy peach is summer’s sweet reward from the Western Slope, where elevation, sunshine and cooling nighttime breezes combine to cause the sugar in the stone fruit to concentrate and become sweeter.

For those who crave even sweeter, cobblers are easy to make. All you need is fruit, butter, sugar and flour.

Another option is Rustic Peach Crostata, a favorite of personal chef and food stylist Mari Younkin. Crostatas are an Italian version of the French galette, which, Younkin says, is “a flat tart that’s free-form, and you fold the dough edges up and over the filling, exposing the center.”

“This peach crostata is filled with thin slices of ripe peaches that have macerated with sugar and their own juices, with a little vanilla and peach brandy,” Younkin says.

TERESA FARNEY

Ingredients

1 (12-inch) pie crust (commercial or homemade)

5 cups fresh sliced peaches

¼ cup light brown sugar

¼ teaspoon cinnamon

1 tablespoon fresh squeezed lemon juice

½ tablespoon pure vanilla extract

2 tablespoons butter (slightly melted)

2 ½ tablespoons all-purpose flour

3 tablespoons sugar

2 tablespoons heavy whipping cream

Vanilla ice cream (optional)

Directions:

1. Place peaches into a large bowl. Sprinkle brown sugar, cinnamon, lemon juice, vanilla extract, melted butter, and flour over peaches and toss to mix slightly. Set aside.

2. Remove the pie crust from the refrigerator. Pour peach mixture with juices in center of the pie crust. Arrange the peaches evenly, leaving at least a 2-inch rim all the way around the peaches. Begin to fold the pie crust up and over the edge of the peaches.

3. Brush the pie crust evenly with heavy whipping cream. Generously sprinkle sugar over the crust. Bake at 400 degrees for 40 to 45 minutes until golden and bubbly. Serve with vanilla ice cream or enjoy as is.

COURTESY OF MARI YOUNKIN, PERSONAL EXECUTIVE CHEF AND FOOD STYLIST

Northeast of Cripple Creek, there’s an empty, windswept meadow where another city rose and fell.

Gillett was the “City of Destiny,” proclaimed the Gillett Forum in 1898, as prospectors rushed for riches in the surrounding hills. The vision came for the town to be the “Monte Carlo of the West,” a gambling epicenter.

There was a track for horse racing. There was a church built by a “determined priest,” reads one account by Virgil L. Kellogg.

There were several saloons, as well as a meat market, a bakery, a sawmill. There was a man named Joseph H. Wolfe, “owner of a hotel and the largest casino in Gillett.”

And there was a bullfight. It was Aug. 24, 1895, billed as the first bullfight in America.

Wolfe oversaw an arena built and ads posted for the “Great Mexican Bull Fight.” True matadors took a train in from the old country. Among them was La Charrita, promoted as “The Only Lady Bull Fighter in the World.” Kellogg retold the festivities in his account, starting with the band’s “off-key tune” — a proper precursor.

Either the first helpless bull was slain and the brutish event promptly called off, as The Gazette Telegraph reported, or fights started and stopped with arrests made in between. At any rate, history collectively recalls the show as a failure.

And fail, too, did the rest of Gillett.

SETH BOSTER

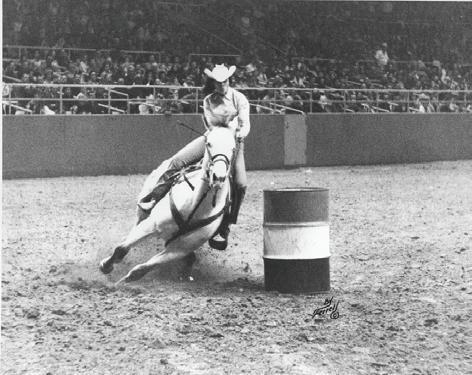

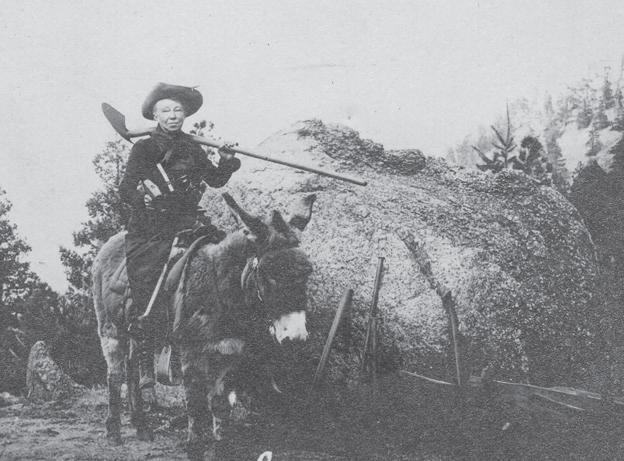

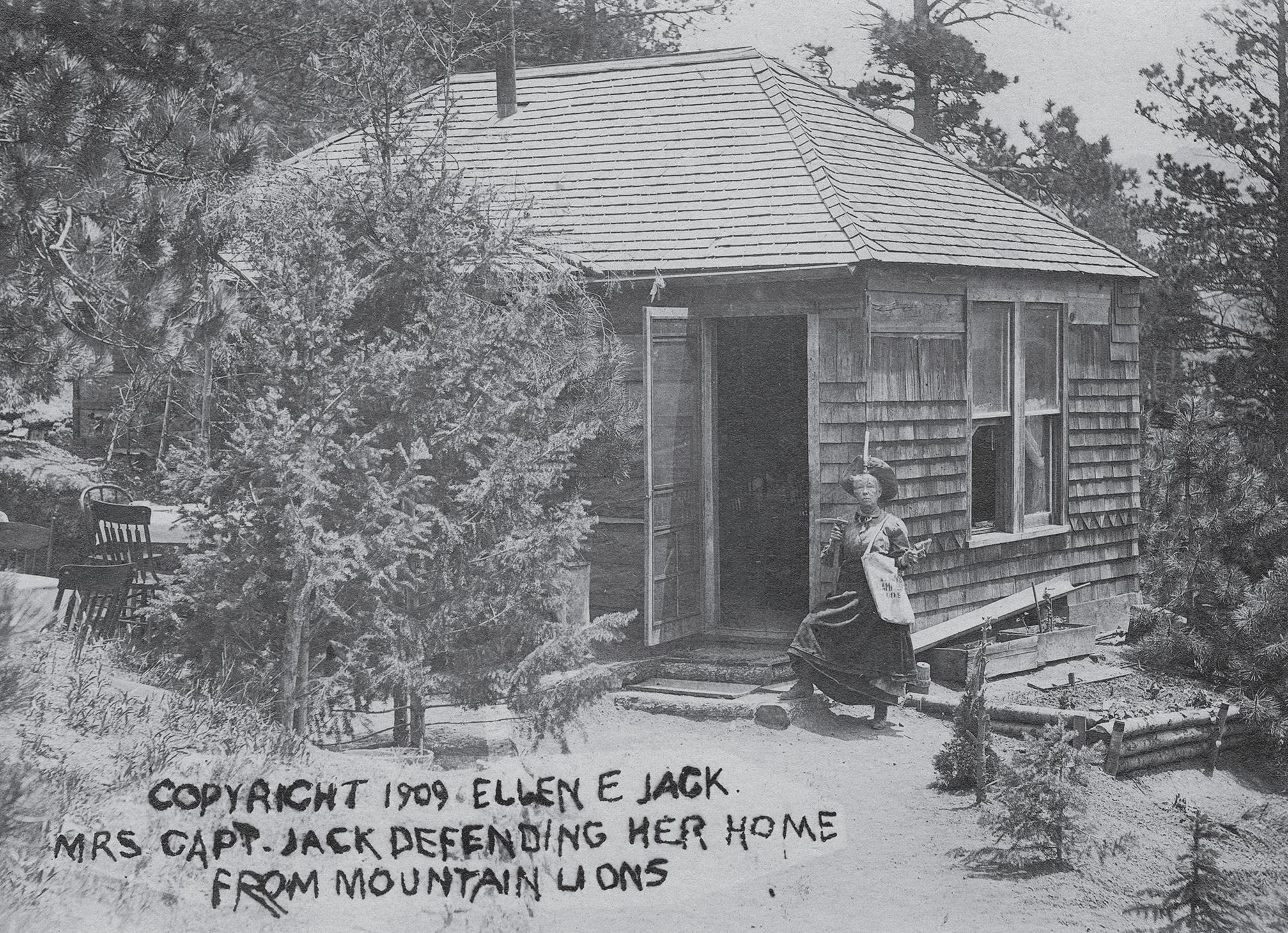

The colorful, complicated life of a Colorado Springs legend

TEXT BY SETH BOSTER

nce upon a time, in the mountains of Colorado Springs, there lived a woman who wore a candlestick atop her hat, who carried a pickax in one hand and a pistol in the other.

She dug for treasure around these mountains, burros in tow. Otherwise, she could be found at her cabin with her cats and parrots. She’d take pictures with tourists and tell tales at her place along High Drive.

That old carriage route is now silent, free of motors, left for hikers and mountain bikers to roam. Some say a spirit resides there — the spirit of that woman who died a century ago but maybe never left.

Or maybe it’s a fairy, as Ellen Jack knew herself to be. She titled her autobiography “The Fate of a Fairy,” published before her death in 1921.

By then, she was well known as Captain Jack. She was “one of the West’s most remarkable personages,” read her obituary in The Gazette. Her legend first grew in Gunnison, where the newspaper ran another remembrance: “The history of this remarkable woman reads like a page from some thrilling romance and all the more interesting because it was true.”

Or mostly true, says Leah Davis Witherow, curator of history for Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum.

Several parts of “The Fate of a Fairy” are “exaggerated, if not wholly fabricated,” Witherow says. After all, there on High Drive, Captain Jack was selling a story, a persona.

“I don’t think we can separate fact from fiction with Captain Ellen Jack,” Witherow says. “But I don’t think we necessarily need to.”

Because beyond some of the questionable details — beyond the gypsy that supposedly foretold Captain Jack’s destiny; beyond her story of meeting Abraham Lincoln before pursuing that destiny out West; beyond the gunfights and poison tomahawk that supposedly scarred her forehead — what ultimately matters is what the woman represents, Witherow explains.

“The lives of women in the 19th century West were inherently shaped by race, class, gender and ethnicity,” she says. “Captain Ellen Jack is an example of a woman who sought to live life on her own terms, even if she had to become a caricature of the old or imagined West to do so.”

It’s a sentiment shared by Jane Bardal.

With her 2023 book, “Colorado’s Mrs. Captain Ellen Jack: Mining Queen of the Rockies,” she aimed to parse fact from fiction more than any writer ever had. Bardal pored over documents and newspaper accounts that piled up through Captain Jack’s life.

“She wasn’t always a likable person,” Bardal says. She was always “feisty” and “independent,” the author says — “someone who forged her own path” and “followed her own inner light throughout her life.”

Her life began in England. She was said to be born to a well-to-do family on a homestead settled by a founder

of the Quakers. Ellen clearly developed her own spirituality — perhaps shaped by a childhood encounter with a gypsy.

According to “The Fate of a Fairy,” that gypsy declared Ellen a Rosicrucian, among that secret sect of ancient, powerful people: “[T]his child was born to be a great traveler, and if she had been a male would have been a great mining expert. ... She will meet great sorrows and be a widow early in life.”

She would be a widow in 1874, Bardal found. Ellen had been married to Charles Edward Jack, whom she recalled as the first officer of the ship she took to New York — “my captain,” Ellen called him.

In her book, she recalled him serving the Union during the Civil War. She recalled an aristocratic life with him, a life of church-going and party-going, including a reception hosted by the Lincolns.

She wrote of the home she and her captain built and the children they raised. And she wrote of great sorrows.

She wrote of sickness claiming the lives of two children. She wrote of her husband on his deathbed, of him seeing their daughter in heaven: “Come, papa, come and leave this world of sin and sorrow and come to your God.” Not long after his death, Ellen wrote of losing another sick daughter.

One might be reading a dramatization. Fact or fiction, it’s true that sickness and death swept society at the time.

“Loss was common in the 19th century in a way that’s hard for us in the 21st century to imagine,” Witherow says.

Also true, she says: “People saw the West as a place of economic and social opportunity. And for a woman who has suffered great loss, the West is a place to recuperate. It’s a way to make a living and reimagine yourself in a new identity.”

Ellen Jack would become Captain Jack. It would be a name known around the West years before her arrival in Colorado Springs.

Bardal’s book places her in Gunnison in 1880. She opened a boarding house and restaurant there, continuing a line of work from back East.

Her Bon Ton Hotel on Coney Island had burned in 1876. She suspected friends of arson, prompting a long court battle, Bardal writes: “She said of this experience, ‘I began to see that the only friend on Earth was money, and not only a friend, but power; that I must stir and do something or go somewhere.’”

That somewhere was Gunnison. More enemies awaited, more than just the bandits she wrote of fighting en route to town. Some of the first of her many court battles in Colorado regarded accusations of her assaulting crazed men

with a bottle and her hiding a fugitive.

And there would be more sorrow.

Ellen lost another husband, a hard-drinking man. She reluctantly married again, to a man named Walsh.

“Ellen hoped that Walsh would protect her,” Bardal writes, “but he soon became her adversary.”

While fighting in court for divorce, she also fought Walsh from acquiring the mine near Crested Butte that brought her initial fame and fortune. Maybe more than that, Black Queen Mine brought her turmoil.

Walsh was but one man who claimed rights. Reported the social justice-minded Queen Bee newspaper in Denver: “There is a band of masculine thieves ... who have clubbed together to rob Mrs. Captain Jack.”

She was not exactly innocent. Regarding a claim she oversaw a brothel, “It is possible that charges against Ellen were true,” Bardal determines in her book, which also recounts her winding up in jail for drawing a gun on a man.

That legal trouble constantly followed Captain Jack could have been partly due to her “audacious personality,” Witherow says. She could have also been a victim of an intensely litigious time for mine owners, the historian notes.

“It’s often said the folks who made money were the ones who mined the miners, and that would be attorneys,” she

says. “But certainly as a woman who fought to retain ownership, she would’ve been seen as incredibly challenging and nontraditional. She would’ve perhaps been a larger target.”

Captain Jack left Black Queen Mine behind when she settled in Colorado Springs, after other mining ventures around Ouray and the far western desert. She established new claims around High Drive, calling them Mars.

Writes Bardal: “She regarded herself as a daughter of Mars, born under that sign, which symbolizes strife and war.”

Strife continued in Colorado Springs between business partners who sued her and police who came after her for selling booze at her tourist stop. She lost battles before apparently losing everything toward the end of her life. In 1918, she filed for bankruptcy.

“In the meantime,” Bardal writes, “Captain Jack refused to give up staying at her cabin on High Drive.”

There high in the forest, the Rocky Mountain News found her to be “the epitome of the sublime and the ridiculous.” She was found to be gazing upon the stars: “Anon she communes with the elements ... Messages flash from the skies.”

She shared some messages in “The Fate of a Fairy,” writing of “a power far stronger than that which forces us to

our destiny.” There was a light in us, she wrote, and “some people carry a straight light around them that is destruction to one that carries the opposite light.” And all moved through “a triangle of three powers ... electricity, vibration and this force power. I know not what to call it ...”

Call it fortune and misfortune, blessings from above and troubles from a broken world. Captain Jack knew both, especially the latter it seems.

Having endured loss after loss, there was one more she could not take before her death in 1921.

High Drive had been wrecked by a flood, Bardal says. “What the newspapers said contributed to her death was leakage of the heart and stress caused by not being able to go back up High Drive.”

That place “meant her freedom,” Bardal says. There, she could be whoever she wanted to be — “the Mining Queen of the Rockies,” as she proclaimed herself, and the oddly dressed and armed woman seen in the postcards she made.

“She became a character in her own story,” Witherow says.

Whatever that “force power” was, she could never control it. But there on High Drive, “she controlled the terms,” Witherow says. “It was her sanctuary.”

now has melted from Colorado’s high country. Consider it nature’s invitation to climb.

The state’s tallest summits await. So many to do. So little time.

The most avid climber needs a base camp, a place from which to attain multiple fourteeners. Here are some towns that come to mind, along with a few suggestions while you’re visiting.

In reach: Antero, Belford, Columbia, Elbert, Harvard, Huron, La Plata, Massive, Missouri, Oxford, Princeton, Shavano, Tabeguache, Yale

One might choose Salida to the south or Leadville to the north, but Buena Vista is close enough in the middle while serving as the closest access to the Collegiate Peaks. There’s a reason why BV is home to the annual 14er Fest. It’s true: There might be no greater place to celebrate Colorado’s highest heights.

Overnighting: Among the most popular campgrounds are Cottonwood Lake and Chalk Creek. You might also look elsewhere along Cottonwood Pass, or check out reservable sites within Arkansas River Headwaters Recreation Area. Closer to Leadville, find Turquoise Lake and Twin Lakes. Or spoil yourself at the riverside Surf Hotel or Mount Princeton Hot Springs Resort, with modern hotel rooms and cabins.

After the hike: Pizza and beer at Eddyline Brewery & Pub; Sweetie’s Sandwiches & Baked Excellence in Salida; High Mountain Pies in Leadville

What else to see and do: Catch a movie under the stars in a big field west of BV: Comanche Drive-In

claims to be the highest drive-in theater in the U.S. About 20 miles away, St. Elmo is one of the state’s most accessible, most picturesque ghost towns.

In reach: Bierstadt, Blue Sky, Democrat, Grays, Holy Cross, Lincoln, Sherman, Torreys, Quandary

For Colorado’s central peaks, Breckenridge might come to mind before Frisco; Breck is closer to Quandary, Sherman and the cluster defining the DeCaLiBron loop. But consider Frisco’s convenient location off Interstate 70, leading west to Holy Cross or east to Grays, Torreys, Bierstadt and Blue Sky. Plus, you can come back to the refreshing Dillon Reservoir.

Overnighting: There is a variety of reservable and first-come, first-served sites at these campgrounds along Dillon Reservoir: Peak One, Pine Cove, Heaton Bay, Lowry, Prospector and Windy Point. Among hotels, Frisco Inn and Frisco Lodge are situated near Main Street.

After the hike: Beer and Thai-inspired fried chicken at Outer Range Brewing Co.; chili or a burger at local staple Moose Jaw; elevated pub fare at historic Gold Pan Saloon in Breckenridge

What else to see and do: Check out the concert lineup at Dillon Amphitheater. The venue featuring views of the picturesque lake and surrounding mountains has risen to bucket-list status for music lovers.

In reach: Blanca, Challenger, Culebra, Ellingwood, Kit Carson, Lindsey, Little Bear Alamosa is not popularly thought of as a base camp for fourteeners. And yet Alamosa is in the heart of the world’s largest alpine valley, the San Luis Valley. The

Sangre de Cristo peaks await. And they are far from the only intrigues surrounding Alamosa.

Overnighting: The most enticing nights under the stars are at Great Sand Dunes National Park. Piñon Flats Campground is in high demand, as is Zapata Falls Campground. Outside the park, Sand Dunes Recreation books cabins and sites for tents and RVs — plus hot springs.

After the hike: Finer dining and cocktails in a historic, converted church at The Friar’s Fork; My Brothers Place for pizza; Calvillo’s Mexican Restaurant

What else to see and do: North America’s tallest sand dunes might be the second strangest destination in the San Luis Valley. The first might be Colorado

Gators Reptile Park.

In reach: Capitol, Castle, Conundrum, Maroon, North Maroon, Pyramid, Snowmass

Many come to Aspen for refined luxury, though others come for technical, challenging peaks. That’s the Elk Range, home to two of Colorado’s most photographed fourteeners: the Maroon Bells. Capitol Peak might be the most infamous. The Knife Edge that awaits is not for all. For the victorious, the rewards are endless in town.

Overnighting: For the Maroon Bells, you’ll have to clear logistics for shuttling or parking at Maroon

Lake, on top of regulations within Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness. Reservations are required for go-to campsites, including at Crater, Capitol and Snowmass lakes. Reservable sites are limited at Silver Bar, Silver Bell and Silver Queen campgrounds along Maroon Creek Road. Two top hotels in Aspen not to be missed are the historic Hotel Jerome and The Little Nell.

After the hike: Big Wrap for big, affordable sandwiches and smoothies; Hickory House Ribs & Steaks for no-fuss barbecue; for a splurge, globe-trotting cuisine at Mawa’s Kitchen

What else to see and do: Aspen Art Museum is a gem that’s free to explore. Two must-stops along Independence Pass, other than the top of the Continental Divide: the Grottos and Independence ghost town.

In reach: Handies, Red Cloud, Sunshine, Uncompahgre, Wetterhorn

You won’t find urban spoils at this base camp, within a county considered the most remote in the Lower 48. You’ll find only natural splendor — arguably the finest in all of Colorado. You’ll want a high-clearance, four-wheel drive and know-how to cover the entirety of the Alpine Loop that accesses these San Juan summits, most of which are Class 1- and 2-friendly.

Overnighting: On its Alpine Loop web page, the Bureau of Land Management maps several dispersed campsites. Mill Creek Campground could be an option close to Red Cloud and Sunshine. There are also sites near Grizzly Gulch trailhead for Handies and near Nellie Creek trailhead for Uncompahgre

and Wetterhorn. Back in town, there is Wupperman Campground and several cabin lodges.

After the hike: Packer Saloon and Cannibal Grill recalls the notorious, local legend; Southern Vittles for comfort classics; San Juan Soda Co. for a nostalgic treat

What else to see and do: Lake City gets its name for Lake San Cristobal, the state’s second largest natural lake. The shores offer a scenic rest after the climbing.

In reach: Eolus, North Eolus, Sunlight, Windom

The ideal base camp is actually not Durango, but rather Chicago Basin. Sure, you’ll want to snag a night back in the town of endless fun. But for the fourteeners, you’ll want a night or two in the remote basin. Making the adventure even more unforgettable: starting by train, the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. From the Needleton stop, the trail runs six miles to Chicago Basin.

Overnighting: There’s backcountry camping around the basin. Back in Durango, Strater Hotel is the Victorian memory maker — a 138-year-old landmark that’s home to a Wild West-themed saloon, a fine dining restaurant and a cocktail lounge.

After the hike: James Ranch for farm-to-table burgers and more; pizza and beer in Olde Schoolhouse Cafe & Saloon; Gazpacho for Mexican

What else to see and do: Durango Hot Springs has redeveloped in a big way in recent years. The train to Silverton is especially sought in the fall for aspen colors.

The sounds of howling swirl out into the mountain air. They are spine-tingling, almost mournful tones, like faraway train whistles on a rainy night. In the right weather and terrain, a wolf’s howl can be heard for miles.

Humans like to typecast these animals. They are big and bad above all; they are lone, predatory and fearsome. But here at Colorado Wolf & Wildlife Center in Divide, a host of staff members, volunteers and thousands of visitors a year see them differently: as creatures in need of saving.

On this afternoon, Annie Kosman radios for a refill on kibble as a tour group gathers in anticipation of a visit to the center’s 20 residents, which include not only wolves but foxes, coyotes and two New Guinea Singing Dogs that look like dingos and whose unique call is sonically closest to whale song.

Kosman points to a dry-eraser map depicting the historic range of America’s three wolf species, then flips the whiteboard to reveal their current status. Highly successful extermination efforts by European settlers and the animal’s on-again, off-again inclusion on the endangered species list have diminished the wolf population in the lower 48 states by almost 99%.

We don’t need to trap wolves for fur or food anymore, Kosman points out, but fur farms are still legal, poaching proliferates in states that don’t have strict penalties and trapping is allowed on 11 million acres of National Wildlife Refuge land.

“If there’s one thing you take from my tour today, it’s that your voice matters,” she says. * * *

Saving wolves was not even remotely on Darlene Kobobel’s to-do list when she moved to Green Mountain Falls in the early 1990s and figured she could meet people by volunteering at a nearby animal shelter.

She’d only been helping for a few days when she was asked to drive three surrendered dogs to PetSmart in hopes of getting them adopted. But when Kobobel

popped back inside for some forgotten water bowls, she came face-to-face with a silvery wolf dog.

“Absolutely stunningly gorgeous,” she recalls. “She looked at me and I looked at her, and she starts jumping up and down like, ‘Get me out of here!’”

Kobobel guessed she could take the wolf dog for adoption as well, but the animal control officer at the shelter knew otherwise. Any dog with wolf DNA could not be adopted out. Chinook, as the 2-year-old had been called by the family that surrendered her, would be killed that afternoon.

“Guilty because she had wolf in her name,” Kobobel said.

When Kobobel rushed back to the shelter that after-

noon, the wolf dog was being led into a back room to be euthanized.

Kobobel wondered how, when she got back to her teeny cabin and her own three dogs, she would tell her husband they were now adoptive parents to a wolf. * * *

The one wolf dog living at Colorado Wolf & Wildlife Center is giving Kosman open-mouthed kisses, sticking her head through the wires of the enclosure to vigorously lick her face as tour group members laugh and hold up their phones.

Luna’s tail wags in a way the other wolves’ don’t, and she rolls over for a belly rub in the cutest canine way.

Many who buy wolf dogs are attracted to their looks. People assume they can handle any lupine shenanigans.

But Kosman says discounting the wolf part of a wolf dog sets everyone up for failure and leads a huge percentage of them to be surrendered and killed by their third birthdays.

One reason is wolves are actually quite fearful by nature;

they develop intense neophobia — a fear of new things — by the time they are 3 but often earlier, and it can make their behavior much harder to manage.

Take, for example, Keyni, an 11-year-old grey wolf with piercing yellow eyes that was brought to the center from a Florida sanctuary. He’s afraid of chickens, the resident peacocks and the bubbles that staff blew his way as part of an enrichment activity.

Kosman tells the group that one staff member who had a wolf dog once ran out to the store and came home to find her pet on the roof of the house. The animal had somehow chewed through the drywall on the ceiling.

Clearly, they’re not the kind of pet you take on the family road trip or dress in a costume for your Instagram feed.

Nevertheless, most Coloradans can own one with no special licensing requirements no matter how much wolf DNA is in the mix.

When Kobobel found herself suddenly caring for Chinook and realized how many wolf dogs don’t get a second

chance, she decided to open a rescue. She had moved to Lake George and owned 8.5 acres down a long dirt road. An artist friend painted a sign for her that read: “Wolf hybrid rescue center.”

By the end of the first week, she had 17 animals. And people kept calling.

“I never had a clue about what I was getting myself into,” she said.

But there was no going back. She got a second job, then a third, to afford their food, fencing and care. And she started to learn more, to educate herself about wolf dogs and wolves. She started to take Chinook, who was happy to walk on a leash and meet new people, to elementary schools in order to teach about wolves and their importance to the ecosystem.

After the Hayman fire destroyed the center in 2002, she leased a ranch in Florissant that she believed would be a permanent home for her and the animals. But three years later, the owner changed her mind and Kobobel was on the hunt for land again.

Desperate and practically broke, she went from bank to bank, begging for a loan that would allow her to purchase a 35-acre former llama farm. She was about to sign a deal with a loan shark when she got the call that a bank had finally approved her loan. She cried with relief.

There was no house on the property. No running water, no utilities, no fences for the animals. She’d have to

be her own general contractor. She sat outside one night with a glass of wine and a cocktail napkin and sketched out where the enclosures would be.

A few weeks later, Kobobel found herself outside staring at the moon. It was coming up on full.

“I’m going to do a full moon tour,” she thought, and that week she hung flyers around town. She bought a plastic table, a cash register and an extension cord and set them up under a temporary power pole.

She filled that first tour, garnering enough to pay the first month’s mortgage. “And I was like, ‘I can do this,’” she said.

* * *

Thousands now visit Colorado Wolf & Wildlife Center each year. It’s accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums — the gold standard for institutions that care for wild animals and focus at least part on conservation.

Kobobel looks back and wonders how she did it, how she created this place. But she knows the answer is passion.

“It’s looking in their eyes and saying, ‘I will help you. I’ll do whatever I can,’” she said.