Support fo r TO URING CHICAG O’ S LAKEFRONT WITH GEO FFR EY BAER is prov ided by:

Lead Sponsor: The Negaunee Foundation Lead Corporate Sponsor:

The South Side Weekly is an independent non-profit newspaper by and for the South Side of Chicago. We provide high-quality, critical arts and public interest coverage, and equip and develop journalists, artists, photographers, and mediamakers of all backgrounds.

Volume 12, Issue 16

Editor-in-Chief Jacqueline Serrato

Managing Editor Adam Przybyl

Investigations Editor Jim Daley

Immigration Project Editor Alma Campos

Senior Editors Martha Bayne Christopher Good Olivia Stovicek Jocelyn Martinez-Rosales

Community Builder Chima Ikoro

Public Meetings Editor Scott Pemberton

Interim Lead

Visuals Editor Shane Tolentino

Director of Fact Checking: Ellie Gilbert-Bair Fact Checkers: Bridget Craig Patrick Edwards

Layout Editor Tony Zralka

Executive Director Malik Jackson

Office Manager Mary Leonard

Advertising Manager Susan Malone

The Weekly publishes online weekly and in print every other Thursday. We seek contributions from all over the city.

Send submissions, story ideas, comments, or questions to editor@southsideweekly.com or mail to:

South Side Weekly

6100 S. Blackstone Ave. Chicago, IL 60637

For advertising inquiries, please contact: Susan Malone (773) 358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com

For general inquiries, please call: (773) 643-8533

Trump Kills the Corporation for Public Broadcasting President Donald Trump and his Republican cronies in Congress have finally managed to kill the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), the nonprofit that helps fund National Public Radio (NPR) and dozens of other local news outlets. In response to an executive order from the White House and spending cuts authorized by Congress, CPB has begun winding down and will be completely gone by 2026. Like many of the Trump regime’s destructive and authoritarian moves this year, the death of CPB has long been a goal of Republicans—and its ramifications will be broad, deep, and lasting.

Republicans have been gunning for public media for almost as long as it has existed. The 1967 Public Broadcasting Act created CPB as well as the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), which has hundreds of local member television stations such as Chicago’s WTTW. Within two years, Republicans tried to kill PBS, prompting none other than Fred Rogers, the creator of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, to defend it in a 1969 Congressional hearing.

Rogers was able to convince Congress and in subsequent years CPB and its partners weathered further threats from Republicans, funding cuts by former President Ronald Reagan, and PBS’s loss of Sesame Street to HBO. Part of why CPB wasn’t killed sooner is that every time an attempt to do so came up in Congress, a few Republicans representing rural areas were able to be convinced to join Democrats in keeping it. Without CPB, their far-flung constituents would have no news or information services at all.

Today’s MAGA Republicans are hardly so sensible—and unlike their predecessors, they’re in thrall to the president and deferential to his every whim. If Trump tells them to jump, they say how high; if he tells them to cut services their constituents need, they ask by how much.

In addition to supporting beloved educational programming on television and radio, CPB ensured that viewers and listeners across the country had critically important, up-to-date information about emergencies and natural disasters. It allowed local stations to produce documentaries about area history, news, and culture. It enriched listeners’ and viewers’ lives, expanded their horizons and connected them with neighbors at home and around the globe. And it made all of that for free and available to everyone.

While NPR can weather the loss (only 1 percent of its funding is from CPB), and larger-market outlets such as Chicago Public Media (6 percent of funding from CPB) will survive, countless smaller and rural communities could lose their public stations for good. It’s yet another Trump action that also hurts his own voters.

In an era of FOX on the right wing or MSNBC on the left, much of what’s packaged as news and information today is in fact propaganda or “infotainment.” CPB ensured that public media could strive for true balance in programming even after Reagan killed the Fairness Doctrine, which required news outlets to present balanced coverage of controversial issues. In its absence, our news landscape will grow poorer, misinformation will continue to proliferate, and Americans will become less educated and more polarized.

As with every outrage from the cabal currently occupying the White House, you can do something about it. Support local media. Read, listen, watch, share— and subscribe or become a member. Whether it’s the Weekly (southsideweekly. com/donate/) or one of our friends in the local media landscape, that matters less than it does that you pitch in somewhere. In the meantime, we will keep doing our job: conveying the truth.

public meetings report

A recap of select open meetings at the local, county, and state level.

scott pemberton and documenters .... 4

county ‘data loophole’ lets ice access immigrant info

A clause in the county’s contract lets an information system designed for crime victims funnel sensitive data to ICE-contracted LexisNexis.

alma campos 5

una ‘brecha de datos’ del condado permite que ice acceda a información de inmigrantes

Una cláusula en el contrato del condado permite que un sistema creado para notificar a víctimas de delitos canalice datos sensibles hacia LexisNexis, una empresa contratada por ICE.

alma campos 8

south side sports roundup

The latest results and news from the Chicago sports world.

malachi hayes ....................................... 11

billiken bash

The Bud Billiken Parade, a South Side tradition since 1929, took place this past weekend. k’von jackson, jacqueline serrato ...... 12

‘my refuge, my roof, my safe place’ Migrants were evicted from a cooperative home they helped build.

chelsea zhao 14

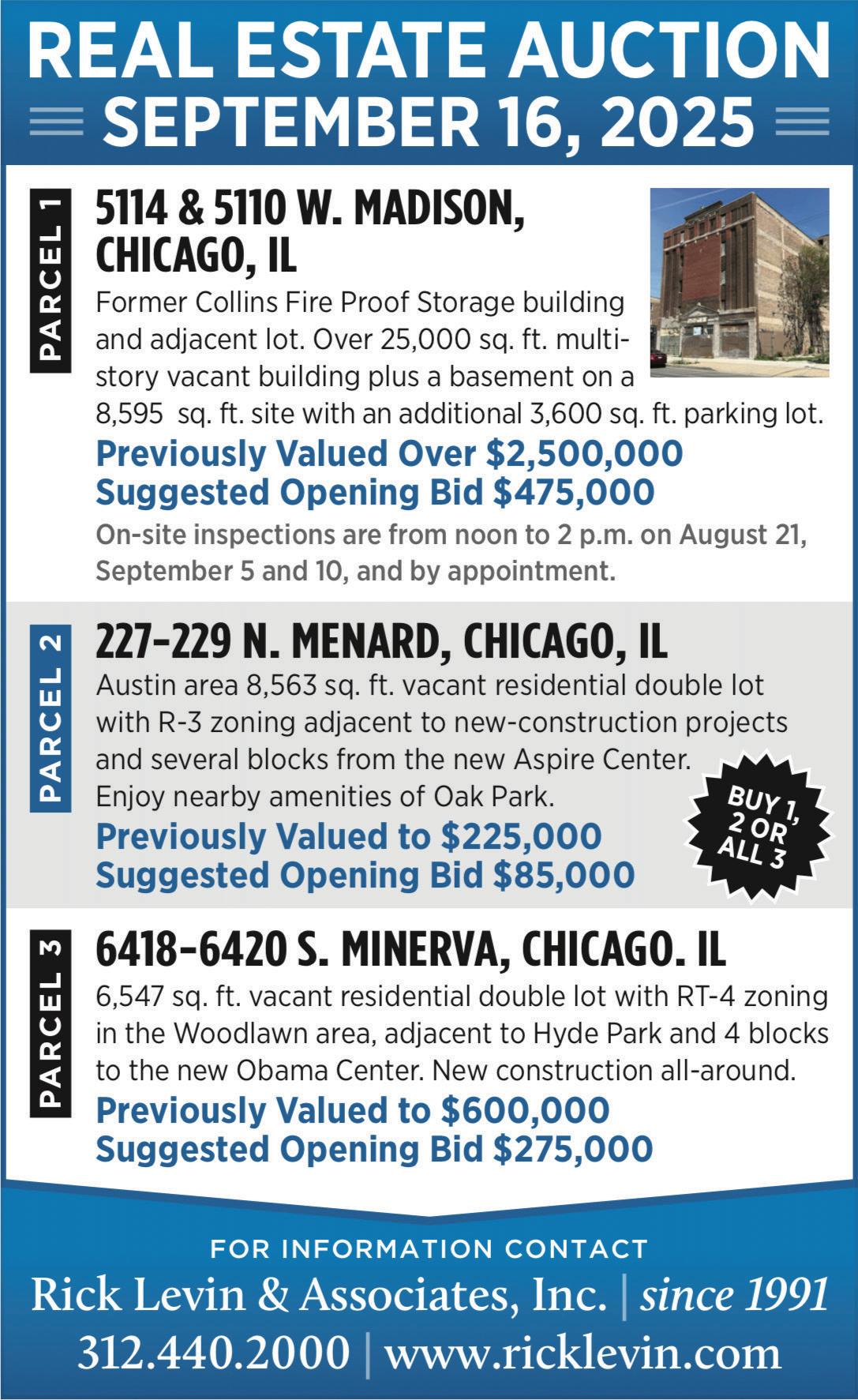

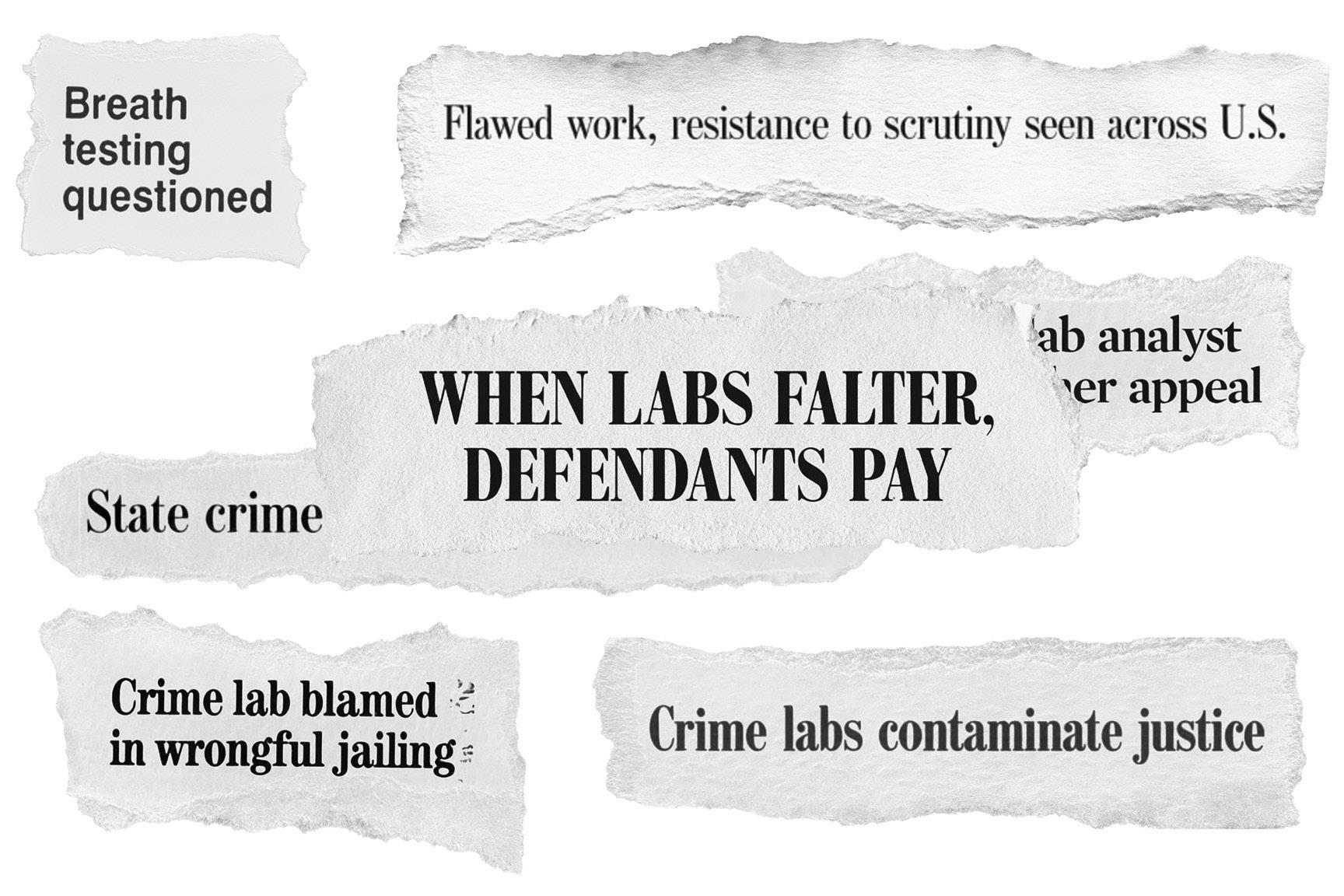

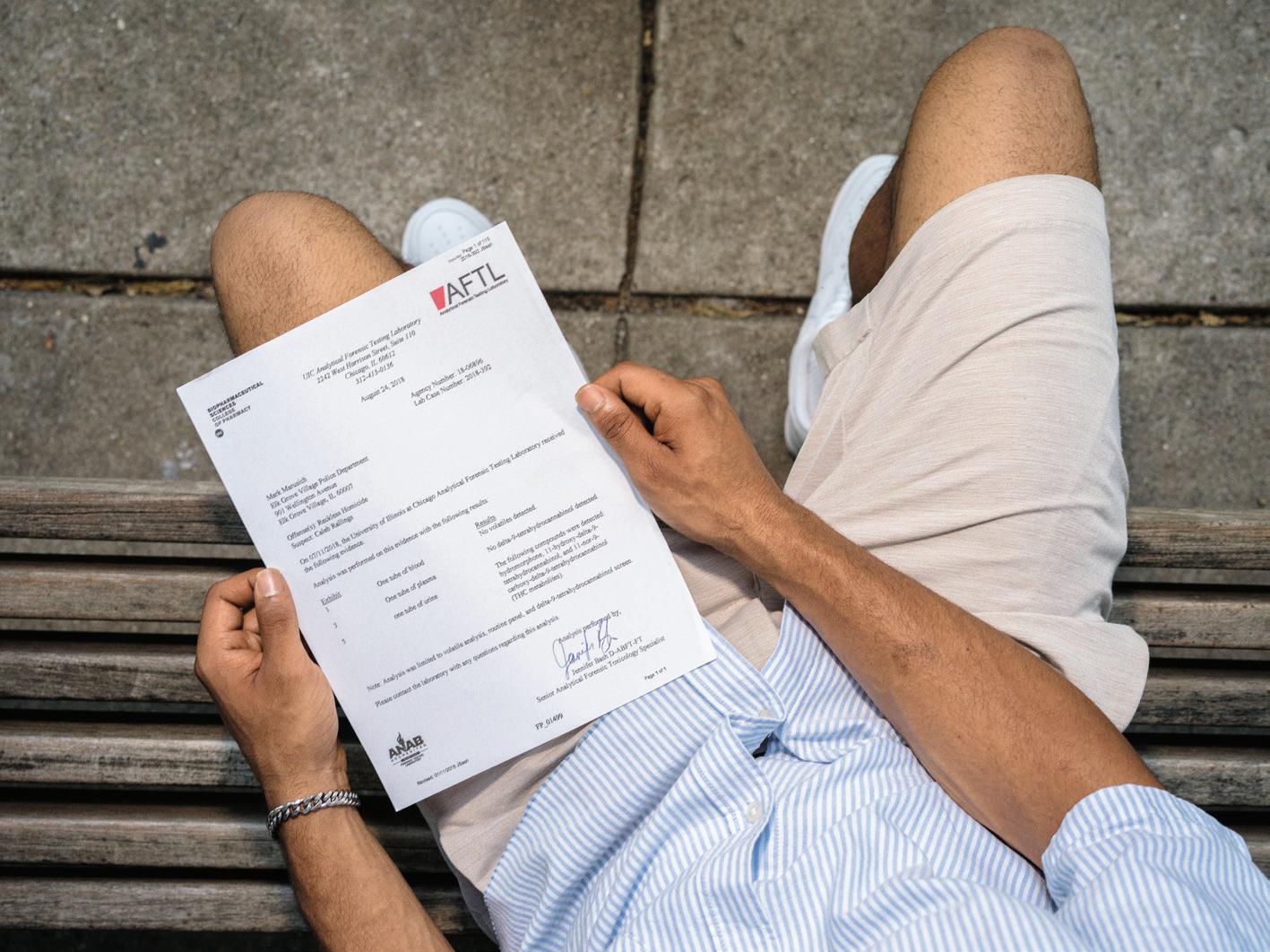

fake science, faulty methods, misleading testimony

How a rogue forensics laboratory at the University of Illinois Chicago got people convicted for driving high.

maya dukmasova, injustice watch 16

illustration by Holley Appold/South Side Weekly

A recap of select open meetings at the local, county, and state level.

BY SCOTT PEMBERTON AND DOCUMENTERS

June 18

At its meeting, the Metra Board of Directors looked toward the future as it took these steps: extending Axon’s contract to March 2030, which emphasizes AI’s role in Metra’s policing methods; highlighting the need to update an aging IT infrastructure in connection with ticketing management and customer service, and projecting cautious optimism about avoiding the projected fiscal cliff in 2026. The Axon website describes the company as “the leading operating system for public safety.” Services in the form of branded products, for example, claim to cut report-writing time by law enforcement “in half” by transcribing and organizing video footage; to scan more license plates faster, and surveil public air space to track “unauthorized drones.” Before the Board of Directors meeting, Metra’s chief financial officer, John Morris, reported on behalf of the Committee on Finance and Budget. He noted that operating revenue is $10 million higher than the projected 2025 budget, offsetting less-than-anticipated revenue from passenger services. At the time of the meeting, expenses for operations were $31.1 million under budget with expenses for May being $8.1 million under budget. Morris attributes the savings to reduced administrative costs. The Capital Delivery and Project Management Office Report was presented by Phil Pasterak, program manager. Thirtyone projects have been completed since 2019, forty-three have begun construction and another fifty-four projects are in preliminary engineering. A majority of projects discussed affected the Metra Electric line. The Board also received a presentation on “Metra’s Comprehensive Approach to Bridges.” Metra lines cross 926 bridges each day, 446 of which Metra owns. A program is designed to replace five bridges and rehabilitate five bridges each year over twenty years. The estimated minimum cost is $140 million annually. There were no public comments.

June 23

The meeting of Police District Council 005: Roseland/Pullman/Riverdale focused on two main topics: the district’s strategic plan and an expected workforce allocation study. In a presentation, council member Thomas L. McMahon reviewed the priorities the council had set in the district’s strategic plan. Shootings were identified as the top priority, and the plan specified “the highest concentration of these shootings occurred on beat 511, which encompasses the area of 95th to 103rd” streets or essentially from Harvard Avenue to Stony Island Avenue. The second priority was robberies, which McMahon described as being in the “20th sector out south.” Third on the priorities list, McMahon said, were drug sales and littering at 111th and State Street. In the development of the district’s strategic plan, he explained that police are believed to be the crime experts but that community engagement needs stronger advocacy. He also suggests the district’s strategic plan can be improved by transparency and measures of progress. The councils are looking to the police department’s superintendent, Larry

Snelling, to include meaningful input from the councils. Regarding workforce allocation, McMahon outlined the question of whether to use police officers from established beats, tactical teams or Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS) teams. Police district councils were recommended by the Community Policing Advisory Panel in 2017 to increase community involvement in “crime reduction and problem-solving strategies” and to ensure “programming … consistent with the principles of community policing.” There are twenty-five councils, seven of which provide reports in Spanish and one that offers its reports in Chinese.

At its meeting, the fourteen-member City Council Committee on Pedestrian and Traffic Safety approved without objection “direct” items for prohibited disabled parking spots, recommended items for stop signs and prohibited disabled parking spots, and “no-recommendation” items for stop signs, prohibited disabled parking spots, repeals to prohibited disabled parking spots, residential permit parking zones, and parking restrictions. Committee Chair Daniel La Spata (1st Ward) explained that “norecommendation” items have not received recommendations from City departments but were submitted as “overrides.” There was one public commenter, George Blakemore, who is known as “Concerned Citizen” and the “51st Alderman” because he has for years attended and spoken out at City Council meetings. In his allotted three minutes, he proceeded to recognize the presence of City staff members, calling them “disgraceful” and saying they “set a bad example”; called for the Council meetings to be televised; claimed most of the few attendees were being paid [to attend]; and concluded with “There’s something evil here; there’s something un-American here.” Chair La Spata told Blakemore, “There’s a line and you are stepping on it.” Blakemore left the meeting shouting. Although “safety” in its title, officially, this Committee has “jurisdiction over all orders, ordinances, resolutions and matters relating to regulating vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic,” according to Chicago Councilmatic. That jurisdiction extends to matters that affect the bureaus of Street Traffic, of Parking, and of Police Traffic.

The Chicago Plan Commission considered and acted on four items at its meeting. A residential plan to expand the XS tennis site at 5301 South State was approved. The plan proposes rezoning the area into a community shopping district (B3-3) from its current designation as a limited manufacturing/business park district. The developer plans to construct a five-story building with fifty-one affordable housing units and a six-story, 125-key Marriott Hotel that would include seventy-two parking spaces. The $25 million project would create one hundred temporary jobs and result in twenty-five permanent jobs, the developer claims. It would also provide two thousand square feet of commercial business space. One public commenter, who said her family has lived in the area since 1914, supported the project but criticized the building’s height and the disruption it would cause during construction. Another commenter compared the process to the gentrification of Bronzeville, complaining that residents have not been involved enough and that the focus has been on “elites” or visitors. Three other proposals were also approved. A one-million dollar park at 141 West Diversey Parkway, which was applied for by the Chicago Park District under the Lake Michigan and Chicago Lakefront Protection Ordinance, would occupy 26,781 square feet. The Commission also approved a proposal by Loyola for a six-story building no more than ninetyfeet high at 6551-6581 North Sheridan Road. The space will be used for classrooms, research, and laboratories. The Burnside, Calumet, and Pullman Industrial Corridors were approved for remediation of environmental issues over several years. Job creation along with improved health and safety are the hoped-for results.

This information was collected and curated by the Weekly in large part using reporting from City Bureau’s Documenters at documenters.org.

A

clause in the county’s contract lets an information system designed for crime victims funnel sensitive data to ICE-contracted LexisNexis.

BY ALMA CAMPOS

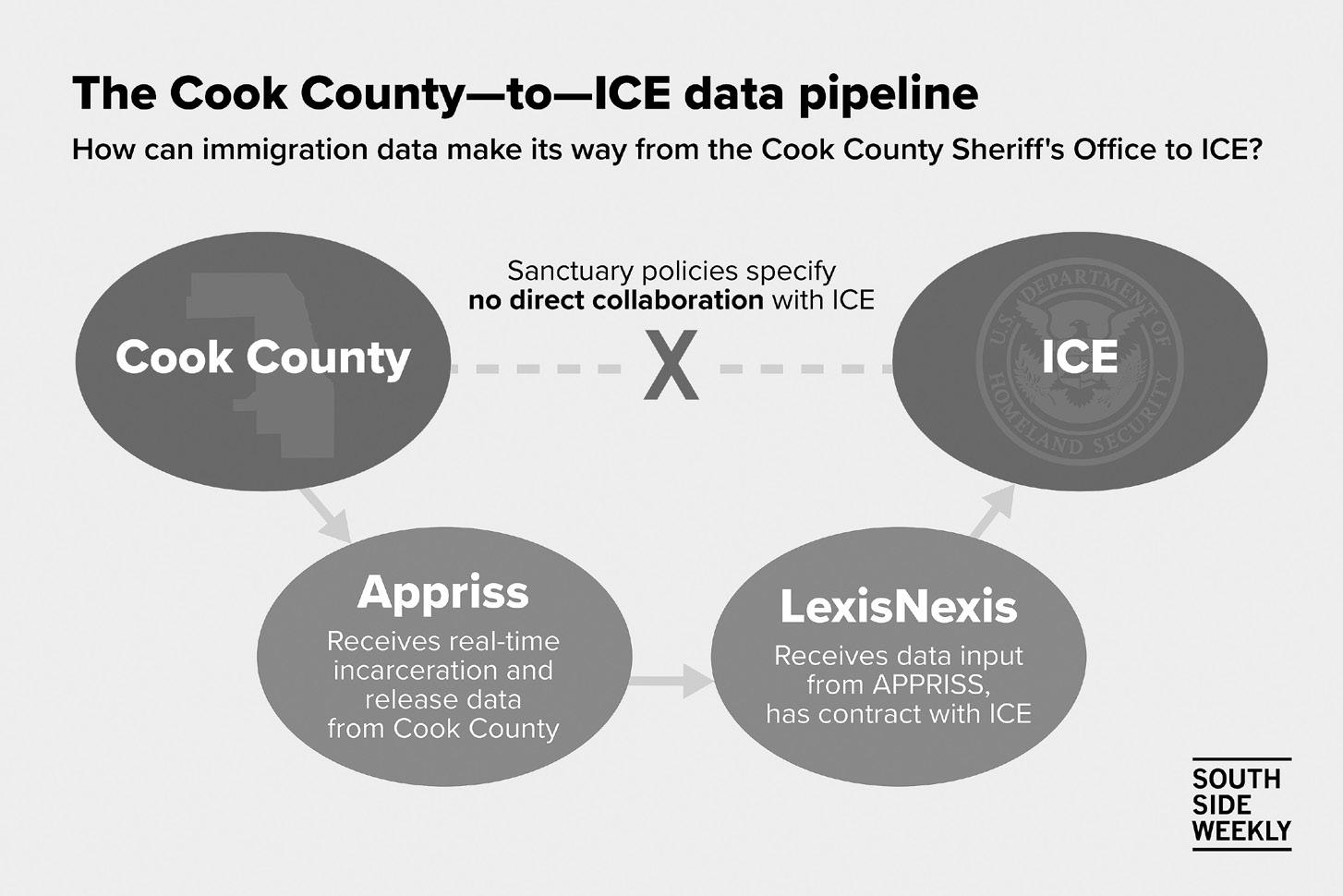

Adata broker that allows users to obtain information about incarcerated people could be a digital backdoor enabling U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents to access the personal data of thousands of immigrants in Cook County

At a Cook County Board meeting last year, commissioners raised concerns about the Sheriff’s use of the system, called VINE (Victim Information [and] Notification Everyday), but voted to keep it. VINE notifies crime victims when an offender or defendant is released from jail, transferred, or has a change in custody status.

ICE’s access to that data goes far beyond the public’s, letting agents combine VINE jail records with personal data to build profiles that can pinpoint where people live and work. Immigrant rights advocates contend that the data, intended for victim notification, has been repurposed into commercial databases ICE uses to locate and arrest immigrants.

Now, advocates are renewing their push to get the Board to amend the County’s contract with VINE after its current contract ends in November.

In 2011, the Cook County Board adopted a “sanctuary” ordinance that prohibits sheriffs from assisting ICE or the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) with immigrant “detainers,” which are requests to alert them when incarcerated immigrants are due to be released. The ordinance also bars the use of county resources to enforce federal immigration laws. This policy stands apart from Chicago’s Welcoming City Ordinance and the Illinois TRUST Act, both of which also limit law enforcement officers from cooperating with ICE’s administrative detention and deportation efforts.

Since 2015, however, the Cook County Sheriff's Office (CCSO) has shared real-time incarceration and release data with Appriss, the company that operates the VINE victim-notification system. Appriss Insights is owned by Equifax, an American company best known for consumer credit reporting. Under Cook County’s contract, a “risk solutions” clause allows Appriss to share jail data with other companies, including LexisNexis Risk Solutions. LexisNexis then packages that data into its Accurint database. Accurint is used by ICE to locate and track individuals, according to a 2022 report by the Electronic Privacy Information Center.

Advocates aren’t asking the Board to get rid of VINE altogether, but instead want commissioners to amend the company’s contract to remove a “risk solutions” clause that authorizes Appriss to share certain jail data with outside companies, including

LexisNexis Risk Solutions. LexisNexis has an active contract with ICE worth up to $22.1 million that grants the agency access to real-time data on jail bookings, as well as names, addresses, court records, driver’s license information, phone data, and more.

Community concerns about ICE’s access to this data have been intensifying over the years according to Cinthya Rodriguez, formerly a national organizer at Mijente who led the #NoTechforICE campaign to expose data-driven surveillance of immigrant communities.

Rodriguez said some people across the U.S. have been picked up by ICE in ways that suggest data-driven surveillance, even in cases where individuals had little or no criminal history.

“Folks were tracking deportation cases, and everyone just kind of had the same question, no matter what part of the country people were in,” she said. “Everyone was

asking, ‘What help is ICE getting? How are they getting access to people’s names and addresses, where they work, what car they’re driving?’”

Rodriguez shared the story of Francisco, a member of the immigrant rights organization Centro Sin Fronteras. Francisco was detained in 2022 by ICE on Chicago’s North Side. “He was taking a shower when ICE came in and literally pulled him out of his house,” she said. The incident raised urgent questions among community members. “People were asking, ‘how did ICE know where he was living and that he was at home at that exact moment?’”

Francisco’s detention prompted Just Futures Law, a legal and advocacy organization that partners with grassroots groups to dismantle mass surveillance systems, to file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request that year with ICE. The documents they obtained confirmed that ICE’s Chicago field office used LexisNexis tools to run over 13,000 searches for civil immigration enforcement in 2021.

In 2022, Cook County Commissioner Alma Anaya (7th District) introduced a resolution calling for an investigation into how the personal data of Cook County residents was being shared or sold—a practice which could violate local and state sanctuary laws, advocates warned. Anaya joined immigrant rights organizers at a press conference to demand action from the Board of Commissioners. On July 27, 2022, the Board held a public meeting to examine the issue.

During the meeting, commissioners heard testimony from members of the public and expert witnesses who argued that VINE was effectively a “digital loophole” to the County’s sanctuary ordinance.

Representatives from Just Futures Law recommended the Board amend its sanctuary law to ban indirect data-sharing with ICE. They also recommended auditing existing contracts that share jail or court data and strengthening future agreements to explicitly restrict third-party access or resale of sensitive information. The goal, they emphasized, is to prevent local data collection from quietly fueling federal immigration enforcement.

But when the County’s contract with Appriss expired in October 2024, the Board voted to extend it another year, despite mounting pressure from immigrant rights groups. Members of organizations such as Mijente, the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, and Organized Communities Against Deportations (OCAD) attended the meeting and spoke out against the dangers of the loophole.

In January, emergency calls to OCAD’s Family Support Network and Hotline increased significantly: Where they got a few calls per day in 2024, they were now getting between 100 and 150.

Xanat Sobrevilla, an organizer with OCAD who helps families navigate the uncertainty that comes when a loved one is picked up by ICE without warning, is concerned about how ICE obtains information that leads to arrests and finds people in ways that community members don’t understand—often without warrants or clear justification. “We’re seeing people picked up, and it’s raising red flags about how ICE is finding them so quickly,” she said.

While no formal vote date has been set by the Board of Commissioners, another decision is expected to come before the contract’s new expiration in late 2025.

“We have every reason to think that this LexisNexis tool is one of the key tools in ICE’s toolbox to find people,” said Laura Rivera, a senior staff attorney at Just Futures Law. “ICE doesn’t have to go into jails—the data comes to them.”

On June 3, the Weekly sent a FOIA request to ICE for recent documents related to use of LexisNexis Accurint and Appriss by agents in its Chicago field office. A response to that request remains overdue.

Advocates say LexisNexis also collects Cook County residents’ data through other channels—and

that can affect people without a criminal history, as commercial databases like Accurint pull from a vast web of public records, consumer data, and online activity.

Claudia Marchán, the executive director of Northern Illinois Justice for Our Neighbors, testified at an October 2024 Cook County Board meeting about how these data-sharing practices had affected her personally, even though she has never been arrested or involved in the court system. “I was never arrested. I was never convicted. I am not in the court system. And yet, my personal information still showed up in a law enforcement database because of LexisNexis,” she said.

Mijente’s Rodriguez, who also attended that meeting, told the Weekly that some officials said they had heard about the issue before the meeting but were unclear on the contract details, while others seemed unaware of the data-sharing implications until that day. “Everyone was just kind of like, ‘we had no idea,’ or pointing fingers at each other,” Rodriguez said.

Marchán said she requested a copy of her data file from LexisNexis, and was surprised to find it was forty-six pages long.

“I was really shocked,” she told the Weekly. “What struck me most was seeing my full Social Security number listed and even detailed information about my family members. I come from a mixed-status family, and if that kind of information ended up in ICE’s hands, it could put many of us in danger.” She added that she hopes the Board will eventually “make a decision that shows the community that [they’re] backing them up.”

According to Rivera, Marchán’s data likely entered LexisNexis’s system through a network of public and commercial records such as utility bills, mortgage filings, or consumer databases rather than any connection to the jail system or VINE.

Still, Marchán’s case shows the scope and danger of these commercial surveillance systems and why advocates say Cook County should not be feeding its jail data into them.

Through a $22.1 million contract with LexisNexis, ICE has access to detailed personal reports like Marchán’s—part of a vast database that includes information on both citizens and noncitizens. LexisNexis, widely recognized for its legal research tools, also operates as a powerful data broker.

In that October 2024 Board meeting, Adam Newman, a special assistant for governmental and legislative affairs in the State’s Attorney’s Office, directly addressed concerns about Appriss’s contract. He revealed publicly that Equifax, Appriss’s parent company, had warned the County that removing ICE access could result in a higher contract price.

He also said that Appriss provided a written assurance that Cook County Jail data would not be shared with ICE through LexisNexis platforms. The Weekly reached out to a CCSAO spokesperson for comment and requested a copy of the written assurance, but did not receive a response.

Immigrant rights advocates say this agreement is not enough, since there’s no legal enforcement or transparency to ensure compliance. Newman noted that unlike Cook County’s contract, the New York Department of Corrections’ agreement with Appriss does not have the risk solutions clause, demonstrating that it is possible to structure a contract that does not funnel data to ICE through third parties.

Commissioner Anaya told the Weekly that since the October 2024 vote, the Board has held multiple meetings with stakeholders to address concerns about the Appriss contract. She also noted that New York City’s Appriss contract did not include a risk solutions clause.

“We continue to meet with stakeholders to understand the complexities and challenges of this issue,” Anaya said, “and are working together to ensure the right steps are taken and the right steps are taken without causing unintended consequences.” She added, “At a time when civil liberties are being rolled back across the country, it’s critical that Cook County remain a leader in protecting all people who interact with county government.”

At the October 2024 meeting, the Board approved a one-year renewal of the contract without amendments. Commissioners said they intended to review the contract in the following months. The delay left advocates frustrated by what they called a lack of closer scrutiny on the contract before approving it.

Advocates contend that the County’s relationship with Appriss stands in stark contrast to its public stance as a sanctuary jurisdiction.

Rivera at Just Futures Law explained

that it’s hard to trace a direct line between ICE surveillance tools like LexisNexis. ICE is not obligated to record or disclose which surveillance tool or database they used to locate someone, so there’s often no official paper trail connecting the arrest to a specific method or query. “This information usually is not part of a person’s case file with ICE,” Rivera said.

But she said that it’s quite clear from looking at federal procurement documents that ICE considers LexisNexis tools “pivotal to their operations,” Rivera said. “That’s their word, ‘pivotal’. These platforms are essential to how ICE locates and targets individuals, especially in places where local law enforcement can’t legally cooperate.”

In August 2022, immigrant rights groups including Mijente, Just Futures Law, and OCAD filed a lawsuit against LexisNexis Risk Solutions, alleging that LexisNexis was used by ICE to access personal and jail-related data without consent, violating Illinois privacy and consumer protection laws. Marchán was also a plaintiff.

Their concern is that the LexisNexis Risk Solutions platform, Accurint, acts as a digital pipeline that allows ICE to track and target people using data that originally came from local governments, including Cook County, even in sanctuary jurisdictions.

In April 2024, the case was dismissed by a Cook County Circuit Court judge who ruled that the plaintiffs didn’t have legal standing and didn’t show sufficient grounds for the claims.

Advocates say that they’re not opposed to crime-victim notification programs like VINE, but want better safeguards against its misuse by federal immigration agents. “We’re not against keeping survivors informed,” Rivera said. “But why are we paying for a system that also fuels deportations?

“At a minimum, local officials should audit these contracts. If you’re funding something that puts your residents at risk, that’s a public accountability issue,” she added. “Even if this isn’t illegal, that doesn’t make it right. There’s a moral and political responsibility to make sure data isn’t being used to harm the people you’re supposed to protect.” ¬

Alma Campos is the Weekly’s immigration reporter and project editor.

Una cláusula en el contrato del condado permite que un sistema creado para notificar a víctimas de delitos canalice datos sensibles hacia LexisNexis, una empresa contratada por ICE.

POR ALMA CAMPOS

Una empresa intermediaria de datos que brinda acceso a información sobre personas encarceladas podría actuar como una “puerta trasera digital” que permite a agentes del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas de Estados Unidos (ICE) acceder a datos personales de miles de inmigrantes en el condado.

En una reunión de la Junta del Condado de Cook el año pasado, los comisionados expresaron su preocupación por el uso que hace la Oficina del Alguacil del sistema llamado VINE (Victim Information and Notification Everyday o Información y Notificación Diaria para Víctimas), pero votaron a favor de mantenerlo. VINE notifica a las víctimas de delitos cuando una persona acusada o condenada es liberada de la cárcel, transferida o cambia su estatus de detención.

El acceso de ICE a esos datos va mucho más allá del que tiene el público, ya que permite a los agentes combinar los registros carcelarios de VINE con datos personales para crear perfiles que pueden precisar dónde viven y trabajan las personas. Los defensores de los derechos de los inmigrantes sostienen que esa información, originalmente destinada a la notificación a víctimas, se ha reutilizado en bases de datos comerciales que ICE utiliza para localizar y arrestar a inmigrantes.

Ahora, los defensores están renovando su campaña para que la Junta modifique el contrato del condado con VINE una vez que el acuerdo actual finalice en noviembre.

En 2011, la Junta del Condado de Cook adoptó una ordenanza de “ciudad santuario” que prohíbe que la Oficina del Sheriff colabore con ICE o con el Departamento de Seguridad Nacional (DHS) en el cumplimiento de “detainers” o solicitudes para avisar cuando un inmigrante encarcelado vaya a ser liberado. La ordenanza también prohíbe el uso de

recursos del condado para hacer cumplir leyes migratorias federales.

Esta política local es distinta a la Ordenanza de Ciudad Acogedora de Chicago y a la ley estatal conocida como el TRUST Act, que también limitan la colaboración de las autoridades policiales con los procesos administrativos de detención y deportación de ICE.

Sin embargo, desde 2015, la Oficina del Sheriff del Condado de Cook (CCSO) ha compartido datos en tiempo real sobre encarcelamientos y liberaciones con la empresa Appriss como parte del sistema VINE.

Appriss Insights —la división de Appriss que administra VINE— es propiedad de Equifax. Según el contrato del Condado de Cook, una disposición llamada cláusula ‘Risk Solutions’ permite que Appriss comparta datos carcelarios con LexisNexis Risk Solutions, una empresa completamente distinta. Luego, LexisNexis incorpora esos datos en su base de datos Accurint, que ICE utiliza bajo un contrato multimillonario.

Los defensores no están pidiendo a la Junta que elimine por completo a VINE, sino que quieren que los comisionados modifiquen el contrato de la empresa para eliminar la cláusula llamada “risk solutions” que autoriza a Appriss a compartir ciertos datos carcelarios con empresas externas, incluyendo LexisNexis Risk Solutions.

LexisNexis tiene un contrato vigente con ICE por un valor de hasta $22.1 millones, que le otorga a la agencia acceso a datos en tiempo real sobre ingresos a cárceles, así como nombres, direcciones, registros judiciales, información de licencias de conducir, datos telefónicos y más.

Las preocupaciones comunitarias por el acceso de ICE a estos datos han ido creciendo, según Cinthya Rodríguez, ex organizadora nacional de Mijente y conductora de la

campaña “#NoTechforICE”, que expone la vigilancia tecnológica de comunidades inmigrantes.

Rodríguez dijo que algunas personas en Estados Unidos han sido arrestadas por ICE de formas que sugieren vigilancia basada en sus datos, incluso en casos de individuos con poca o ninguna historia criminal.

“La gente estaba siguiendo casos de deportación y todos tenían la misma pregunta, sin importar en qué parte del país estuvieran”, dijo. “Todos preguntaban: ‘¿Qué tipo de ayuda está recibiendo ICE? ¿Cómo están obteniendo los nombres, direcciones, lugares de trabajo y vehículos de las personas?’”.

Rodríguez contó el caso de Francisco, miembro de la organización de derechos de los inmigrantes Centro Sin Fronteras, quien fue detenido en 2022 por ICE en el lado norte de Chicago. “Estaba bañándose cuando ICE entró y literalmente lo sacó de su casa”, relató. El incidente provocó preguntas urgentes en la comunidad. “La gente se preguntaba, ‘¿Cómo supo ICE dónde vivía y que estaba en casa en ese momento exacto?’”.

La detención de Francisco motivó a Just Futures Law, una organización legal y de defensa que colabora con grupos comunitarios para desmantelar sistemas de vigilancia masiva, a presentar una solicitud bajo la Ley de Libertad de Información (FOIA) a ICE ese mismo año. Los documentos obtenidos confirmaron que la oficina de ICE en Chicago utilizó herramientas de LexisNexis para realizar más de 13,000 búsquedas relacionadas con la aplicación de leyes migratorias civiles en 2021.

En 2022, la comisionada del Condado de Cook del distrito 7, Alma Anaya, presentó una resolución solicitando una investigación sobre cómo se estaba compartiendo o vendiendo la información personal de los residentes del condado, una práctica que, advirtieron los defensores, podría violar las

leyes santuario locales y estatales. Anaya se unió a organizadores pro inmigrantes en una conferencia de prensa para exigir acción a la Junta de Comisionados. El 27 de julio de 2022, la Junta tuvo una audiencia pública para examinar el tema.

Durante la reunión, miembros del público y testigos expertos argumentaron que VINE funcionaba como una “brecha digital” en la ordenanza santuario del condado. Representantes de Just Futures Law recomendaron enmendar la ley santuario para prohibir el intercambio indirecto de datos con ICE a través de terceros como LexisNexis, así como auditar los contratos existentes que comparten datos judiciales o carcelarios, y reforzar futuros acuerdos para restringir explícitamente el acceso o la reventa de información sensible. El objetivo, enfatizaron, es evitar que la recolección de datos locales alimente silenciosamente la aplicación federal de leyes migratorias.

Cuando el contrato del condado con Appriss expiró en octubre de 2024, la Junta votó para extenderlo un año más, pese a la creciente presión de grupos pro-inmigrantes para cancelarlo. Miembros de organizaciones como Mijente, la Coalición por los Derechos de Inmigrantes y Refugiados de Illinois (ICIRR) y Comunidades Organizadas Contra las Deportaciones (OCAD) asistieron a la reunión y hablaron en contra de los peligros de la laguna legal. En enero, las llamadas de emergencia a la Red de Apoyo Familiar y Línea Directa de OCAD aumentaron significativamente: de recibir unas pocas llamadas diarias en 2024, pasaron a recibir entre 100 y 150 a principios de 2025.

Xanat Sobrevilla, organizadora de OCAD que ayuda a familias a enfrentar la incertidumbre que surge cuando un ser querido es detenido por ICE sin previo aviso, expresó su preocupación por la forma en que ICE obtiene información que lleva a

arrestos y localiza a personas de maneras que la comunidad no comprende —a menudo sin órdenes judiciales ni justificación clara. “Estamos viendo a personas detenidas, y esto enciende alertas sobre cómo ICE las encuentra tan rápido”, dijo.

Aunque no se ha fijado una fecha de votación formal, se espera otra decisión antes de que el contrato expire nuevamente a finales de 2025.

“Tenemos todas las razones para pensar que esta herramienta de LexisNexis es una de las piezas clave en la caja de herramientas de ICE para encontrar personas”, dijo Laura Rivera, abogada principal de Just Futures Law. “ICE no tiene que entrar a las cárceles porque los datos llegan a ellos”.

ICE no necesita acceder directamente al sistema VINE para obtener datos sobre inmigrantes, dicen los defensores. Cuando se ingresa información sobre liberaciones de cárcel en VINE, esta queda disponible a Appriss. Appriss es una subsidiaria de LexisNexis Risk Solutions, lo que según los defensores significa que los datos pueden canalizarse luego hacia bases de datos más amplias de LexisNexis, incluyendo Accurint.

Accurint es una herramienta de vigilancia comercial propiedad de LexisNexis Risk Solutions y utilizada por ICE para localizar y rastrear personas, según un informe de 2022 del Electronic Privacy Information Center.

El 3 de junio, el Weekly presentó una solicitud de FOIA a ICE para obtener documentos recientes relacionados con el uso de LexisNexis Accurint y Appriss por parte de agentes de su oficina en Chicago. La respuesta a esa solicitud sigue pendiente. Los defensores también afirman que LexisNexis recopila datos de residentes del Condado de Cook de otras formas, lo que también afecta a personas sin antecedentes penales, ya que bases comerciales como Accurint extraen información de una vasta red de registros públicos, datos de consumo y actividad en línea.

Claudia Marchán testificó en una reunión de la Junta del Condado de Cook en octubre de 2024 sobre cómo estas prácticas de intercambio de datos la habían afectado personalmente, a pesar de que nunca ha sido arrestada ni ha estado involucrada en el sistema judicial. “Nunca fui arrestada. Nunca fui condenada. No estoy en el sistema judicial. Y aun así, mi información personal apareció en una base de datos policial debido a LexisNexis”, dijo.

Rodríguez, de Mijente, quien también asistió a esa reunión, le dijo al Weekly que algunos funcionarios reconocieron haber escuchado sobre el problema antes de la reunión, pero no conocían los detalles del contrato, mientras que otros parecían no estar al tanto de las implicaciones hasta ese día. “Todos estaban como ‘no teníamos idea’ o echándose la culpa entre ellos”, dijo.

Marchán dijo que solicitó una copia de su archivo de datos a LexisNexis y se sorprendió al descubrir que tenía 46 páginas.

“Quedé realmente impactada”, dijo al Weekly. “Lo que más me llamó la atención fue ver mi número de Seguro Social completo y hasta información detallada sobre mis familiares. Vengo de una familia con estatus migratorio mixto, y si ese tipo de información llegara a manos de ICE, podría ponernos a muchos en peligro”.

Añadió que espera que la Junta finalmente “tome una decisión que demuestre a la comunidad que los respalda”.

Según Rivera, los datos de Marchán probablemente entraron al sistema de LexisNexis a través de una red de registros públicos y comerciales como facturas de servicios, escrituras hipotecarias o bases de datos de consumo, más que por una conexión con el sistema carcelario o VINE.

Aun así, el caso de Marchán muestra el alcance y el peligro de estos sistemas de vigilancia comercial y por qué los defensores dicen que el Condado de Cook no debería alimentar con sus datos carcelarios a estas plataformas.

Mediante un contrato de $22.1 millones con LexisNexis, ICE tiene acceso a informes personales detallados como el de Marchán —parte de una vasta base de datos que incluye información de ciudadanos y no ciudadanos. LexisNexis, ampliamente conocida por sus herramientas de investigación legal, también opera como un poderoso corredor de datos.

En esa reunión de octubre de 2024, Adam Newman, asistente especial de asuntos gubernamentales y legislativos en la Fiscalía del Estado, abordó directamente las preocupaciones sobre el contrato con Appriss. Reveló públicamente que Equifax, propietaria de Appriss, había advertido al condado que eliminar el acceso de ICE podría resultar en un aumento del precio del contrato.

También dijo que Appriss había dado una garantía por escrito de que los datos carcelarios del Condado de Cook no serían compartidos con ICE a través de las

plataformas de LexisNexis. El <i>Weekly</ i> solicitó comentarios y una copia de la garantía por escrito, pero no recibió respuesta.

Los defensores proinmigrantes afirman que este acuerdo no es suficiente, ya que no hay mecanismos legales de cumplimiento ni transparencia para garantizar su cumplimiento. Señaló que, a diferencia del contrato del Condado de Cook, el acuerdo del Departamento de Correcciones de Nueva York con Appriss no contiene la cláusula Risk Solutions, lo que demuestra que es posible estructurar un contrato que no canalice datos hacia ICE a través de terceros.

La comisionada Anaya le dijo al <i>Weekly</i> que desde la votación de octubre de 2024, la Junta ha mantenido múltiples reuniones con las partes interesadas para abordar las preocupaciones sobre el contrato con Appriss. Señaló que, aunque Appriss también opera en la ciudad de Nueva York, ese contrato no incluye la cláusula “Risk Solutions”.

“Seguimos reuniéndonos con las partes interesadas para comprender las complejidades y desafíos en este tema”, dijo Anaya, “y trabajamos juntos para garantizar que se tomen las medidas correctas sin causar consecuencias no deseadas”. Añadió que, en un momento en que las libertades civiles están siendo debilitadas en todo el país, es fundamental que el Condado de Cook siga siendo un líder en la protección de todas las personas que interactúan con el gobierno del condado.

En la reunión de octubre de 2024, la Junta aprobó una renovación del contrato por un año sin enmiendas. Los comisionados dijeron que planeaban revisar el contrato en los meses siguientes. La demora dejó frustrados a los defensores, quienes criticaron la falta de un escrutinio más riguroso antes de aprobarlo. Los defensores sostienen que la relación del condado con Appriss contrasta fuertemente con su postura pública como jurisdicción santuario.

Rivera, de Just Futures Law, explicó que es difícil trazar una línea directa entre las herramientas de vigilancia de ICE como LexisNexis y arrestos individuales porque ICE no está obligado a registrar o revelar qué herramienta de vigilancia o base de datos utilizó para localizar a alguien, por lo que a menudo no hay un rastro oficial que vincule un arresto con un método o consulta específica. “Esta información generalmente no forma parte del expediente de ICE de

una persona”, dijo Rivera.

Pero señaló que, al examinar documentos federales de contratación pública, está claro que ICE considera las herramientas de LexisNexis “fundamentales para sus operaciones”.

“Esa es su palabra: ‘fundamentales’. Estas plataformas son esenciales para que ICE localice y apunte a personas, especialmente en lugares donde las fuerzas del orden locales no pueden cooperar legalmente”, agregó.

En agosto de 2022, grupos proinmigrantes como Mijente, Just Futures Law y OCAD presentaron una demanda contra LexisNexis Risk Solutions, alegando que la empresa fue utilizada por ICE para acceder a datos personales y relacionados con cárceles sin consentimiento, violando leyes de privacidad y protección al consumidor de Illinois. Marchán también fue demandante. Su preocupación es que la plataforma Accurint de LexisNexis Risk Solutions actúe como un conducto digital que le permite a ICE rastrear y localizar personas usando datos que originalmente provienen de gobiernos locales, incluyendo el Condado de Cook, incluso en jurisdicciones santuario.

En abril de 2024, la Corte de Circuito del Condado de Cook rechazó el caso, al dictaminar que los demandantes no tenían legitimación legal y no demostraron fundamentos suficientes para las reclamaciones.

Los defensores dicen que no están en contra de programas de notificación a víctimas de delitos como VINE, pero quieren mayores protecciones frente a su uso indebido por agentes federales de inmigración. “No estamos en contra de mantener a las víctimas informadas”, dijo Rivera. “Pero, ¿por qué estamos pagando por un sistema que también alimenta deportaciones?”.

“Como mínimo, los funcionarios locales deberían auditar estos contratos. Si estás financiando algo que pone en riesgo a tus residentes, eso es un problema de rendición de cuentas pública”, agregó. “Aunque esto no sea ilegal, eso no lo hace correcto. Hay una responsabilidad moral y política de asegurarse de que los datos no se utilicen para dañar a las personas que se supone deben proteger”. ¬

Alma Campos es la reportera de inmigración y editora de proyectos del Weekly

BY MALACHI HAYES

Welcome to the South Side Sports Roundup! Check back every month for the latest news and updates on everything South Side sports fans need to know.

For the first time in what feels like eons, competent baseball is being played on the South Side of Chicago. The Pale Hose burst out of the gate after last month’s All-Star Game with one of their most successful stretches in years, scoring more than six runs per game en route to ten wins in fourteen contests after the break. Despite coming back down to earth in subsequent weeks, the flash of good baseball strikes fans as particularly promising, as it was primarily driven by rookie hitters who are poised to play a major role in the team’s future. Rookie shortstop Colson Montgomery burst onto the scene following his July debut. He slugged eight home runs in his first twenty-six games, challenging a nearly century-old team record held jointly by former MVP José Abreu and Depression-era first baseman Zeke Bonura. Rookie catchers Kyle Teel and Edgar Quero were also instrumental in the team’s hot streak, and nondescript utilityman Lenyn Sosa has come out of nowhere to amass a .345 batting average and four home runs since the break, with both marks ranking second on the team.

Having covered the White Sox for years, current CHGO host and analyst Sean Anderson has been around for just about all of the too-few ups and many downs in recent Sox memory. Now, he thinks the tide is finally starting to turn. “It felt like they were doing the right things at the plate [earlier in the season], but didn’t have the talent to execute,” Anderson told the <i>Weekly</i>. That’s rapidly changing,

he said. “The optimism was growing with every [Chase] Meidroth multi-hit game or during [Miguel] Vargas’s hot streak. Colson’s streak has just been jet fuel.”

In other news, the MLB trade deadline came and went, with the Sox making a series of minor moves to bolster their roster for future seasons. The team took advantage of pitcher Adrian Houser’s improbable run of dominance after being signed off the street in mid-May, flipping him to Tampa Bay for three minor leaguers including infielder Curtis Mead, who figures to get an extended opportunity on the Sox’ roster this season. However, GM Chris Getz drew heavy scrutiny for his failure to trade erstwhile All-Star Luis Robert Jr., whose lackluster play this season has led to questions about his future with the team.

The Sox will finish the month at home, hosting the Minnesota Twins, Kansas City Royals, and New York Yankees from August 22-31.

A nightmarish season for Chicago’s WNBA side has persisted into August. The Sky have won just one of their last eleven contests while being outscored by more than twenty PPG on average. At 8-23, they still have time to improve on last season’s franchise-worst 13-27 record, but the lack of development under first-year head coach Tyler Marsh has raised alarms. Having traded away their next two first-round picks in deals for star forward Angel Reese and guard Ariel Atkins, roads to improvement in the coming seasons are limited. Four years after bringing home their first-ever championship, the team’s prospects are as bleak as they’ve been in recent memory.

At least one potentially trajectoryaltering wild card remains in the form of

ongoing collective bargaining agreement (CBA) negotiations between the league and the WNBA players’ union. The recent explosion of interest in the league has led to contentious negotiations as players seek a fair cut of the resulting surge of league revenue. With top-end salaries that fail to exceed $250,000, WNBA players are currently among the most poorly compensated professional athletes in major North American sports.

Because of the expected leap in salaries and benefits, an overwhelming number of WNBA stars have negotiated their contracts to expire after the current season. An incredible ten out of the top eleven finishers in last season’s MVP voting are set for free agency next winter, including superstars A’ja Wilson, Breanna Stewart, Napheesa Collier, Sabrina Ionescu, Alyssa Thomas, and Arike Ogunbowale. With a foundational superstar in Reese and a new practice facility under construction, a rapid return to relevance for the Sky may be possible in the form of a glut of high-profile free agent additions after an agreement is reached.

Another highly anticipated season is underway for the Bears, who opened their preseason on Sunday with a 24-24 tie against the Miami Dolphins. Quarterback Caleb Williams remained on the sidelines, ceding QB snaps to fan favorite Tyson Bagent (13-19, 103 YDS, TD, INT) and twelve-year veteran Case Keenum (8-10, 80 YDS, 2 TD), who are locked in a tight battle for the team’s backup QB job. Bagent has held the role for the past two seasons, but is facing stiff competition from the thirtyseven-year-old Keenum, whose football acumen and veteran leadership may make him a better fit alongside the immensely talented but inexperienced Williams.

A number of other position battles are underway as the regular season approaches. Recent comments from longtime Bears reporter Adam Hoge suggested that rookie

second-round pick Ozzie Trapilo has the lead on incumbent Braxton Jones and 2024 second-round pick Kiran Amegadjie for the starting job at left tackle, while the team’s first official depth chart release indicated neither Colston Loveland nor veteran Cole Kmet having a leg up on the other as the team’s leading tight end.

Fans are cautiously optimistic about this year’s squad, though recent disappointments have them hedging their bets. Lifelong fan and South Sider Nate Smith isn’t letting himself get too excited, but still thinks improvements are in store. “I think they have a high ceiling if they stay healthy and things fall into place,” Smith told the Weekly. “If I had to make a prediction, I could see them being a 9-8 fringe playoff team that will have some growing pains and hopefully overcome them.”

We are now just weeks away from new coach Ben Johnson’s regular season debut on Monday, September 8, when the Bears will take on the Vikings on national television. The Detroit Lions remain the overwhelming favorite to win the NFC North, but a playoff spot is well within reach in a conference that lacks clear-cut contenders beyond Detroit and defending champion Philadelphia.

Just months after leading the revitalized Walter Dyett School for the Arts to an improbable 2A state basketball championship, Block Club reported this month that head coach Jamaal Gill will not return to the program amid widespread CPS layoffs. Gill alleged that the loss of income from the elimination of his position as head of security at Dyett, as well as other tensions with school administration, left him unable to return to the team he helped build into an unlikely powerhouse.

Malachi Hayes is a Bridgeport-based writer and South Side native.

The Bud Billiken Parade, a South Side tradition since 1929, took place this past weekend.

BY K’VON JACKSON AND JACQUELINE SERRATO

Summer on the South Side peaks with the annual tradition known as the Bud Billiken Parade, which marks the upcoming back-to-school season and showcases the best young Black talent in town. In its 96th year, the parade saw decked out marching bands, dance troupes, musicians, floats, acrobatics and choreographies along Martin Luther King Drive that drew local families and crowds from out of state. The day was filled with barbecuing, hot dogs, ice cream, and outdoor fun.

Who’s Bud Billiken? The boy was a cartoon character in the youth column of the Chicago Defender newspaper that its founder created in 1923—someone whom he hoped would inspire Black children who perused the paper to pursue education, happiness and pride. The

event has been called the largest African American parade in the United States.

This year, Mayor Brandon Johnson invited the Bud Billiken Royal Court to City Hall for a tour of his office and the City Council chambers. The parade “commemorates Black Chicagoans’ historic roots on the South Side, and celebrates our future by putting a spotlight on academic excellence, vibrant dance, incredible music, and amazing food,” Johnson said. “I am always honored to join the largest and oldest Black parade in the U.S. and to lift up our youth as they prepare to start another school year!” ¬

K’Von Jackson is a freelance photographer for the Weekly since 2021. Jacqueline Serrato is the Weekly’s editor-in-chief.

Migrants were evicted from a cooperative home they helped build.

BY CHELSEA ZHAO

For Yus, a migrant who has lived in Chicago for two years, her ability to make a place home is contingent upon the decisions of authorities and landowners.

When she first arrived by bus from Texas in October 2023, Yus managed to find shelter in a tent with her family near the 9th District police station. After the first waves of asylum-seekers were bussed to Chicago in August 2022, police stations throughout the city had become overcrowded and unsafe "temporary processing units," standing in for shelters but lacking resources. So within a month, Yus set out to seek a safe place for her family.

Yus and others who camped in tents

found each other and united to forge a new life. From there, El Comedor Comunitario literally, the Community Dining Room— flourished.

This “mutual aid collective hosting

many mutual aid groups, but led by and for migrants, it relied on support from other community groups while maintaining its independence.

“We were just migrants looking for the

"We were just migrants looking for the American dream. How naive, right?”

solidarity,” in Yus’ words, created a simple anchor point to feed people who arrived vulnerable and unaided in Chicago. One of

American dream. How naive, right?” Yus said in an email interview. “Now, we are the target of persecution and pointed out for no

apparent reason.”

El Comedor Comunitario was based in The Orphanage, a long-running DIY community space at Bridgeport's First Lutheran Church of the Trinity. Gif, a volunteer with Midwest Books to Prisoners, one of the community organizations that shared the space, called it a “possibility playground.”

For decades, The Orphanage had been a space for everything from punk shows to activist meetups. It operated more or less without interference from First Trinity, itself known as an open, queer-friendly church committed to social and political issues. Gif said that when El Comedor Comunitario first started, the pastor first welcomed the group and had migrants

move into the residential part of the building.

For Yus, The Orphanage was a respite after several months of living in shelters. There, she joined others in addressing the community’s pressing need for healthy food and personal hygiene resources, as even finding a place to shower had become difficult.

Besides housing migrants, The Orphanage also had a zine library, a children’s room stocked with toys and games, and space for DIY underground parties.

With newly arrived immigrants, The Orphanage blossomed and grew. In a year, the Comedor Comunitario team organized biweekly dinners to feed the community. Yus said she helped to cook food for as many as 180 people, with items including arepas (a stuffed, flat cornmeal bread that is a staple in Venezuela), ensalada de payaso (a salad of carrots, beets and potatoes), or simple chicken soup.

Together, the migrants who stayed at the place maintained and repaired the space, with the intention to help those escaping political and social strife in their countries. El Comedor Comunitario became not only a place for migrants to get food, but a resting place of safety and stability—the first many had seen since the start of their long trek across the continent.

“It is a beautiful and experimental intersection of collaborative struggle against detention, prisons, and towards building a new world of mutuality,” Gif said.

“It is so important that we call it home,” Yus said. “It was not just the place where we lived, we made it ours—something very precious; we got used to being here. It is very unfortunate everything that is happening.”

After years of declining attendance, First Lutheran Church of the Trinity held its last service in 2023. The organizers and artists that lived in or used the space pushed for residency and community ownership. But City records show that in June 2024, the bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America's Metropolitan Chicago Synod, which owned the church, authorized the sale of the building to WW Investment, a local LLC owned by Wendy Peiyi Mui. Residents of The Orphanage say that developer Howard Mui is the owner of the building, and that he delivered eviction papers in January.

In April, the City's Department of Buildings filed a stop work order at the site, stating that work had begun on the exterior of the building without a permit. In June, the City sued WW Investment LLC over that building code violation. Mui could not be reached for comment.

As an effort to save The Orphanage, the volunteers put up flyers in Bridgeport and circulated a petition on social media to raise awareness. The petition garnered over 600 signatures in two months, with many comments recalling fond memories over the past decades. In the comments under the petition, people described The Orphanage as “life-changing,” “crucial,” and “vital” to

Bridgeport’s history and culture. Many highlighted the pathbreaking work of the space for migrants, its lively music scene, and Midwest Books to Prisoners' “literacy

But those who had lived, worked, and built a community at The Orphanage were left with no choice but to make plans to leave.

Still, at the end of May, the community organized ORPH Fest, a three-day festival and effort to “go out with a bang” and celebrate the volunteers, artists, organizers, and collaborators who put so much energy and love into this place. El Comedor Comunitario also participated, making empanadas and other fried food for sale.

And then, on June 14, The Orphanage held one last show.

Flores Negras, a Chicago-based techno DJ, performed at the last show. She has performed at The Orphanage for many years, building relationships with many there for nearly a decade. The DIY culture and anti-fascist politics made the space special to her. She says that Midwest Books for Prisoners’ support for an incarcerated family member led her to the artistic scene.

“I think because of my loudness I was able to attract some really great people to feel safe, to come to my events,” Negras said. She, along with other artists, played cumbia and bachata tracks to bring visibility and crowdsource support for residents facing eviction.

What comes next is uncertain. In June, Midwest Books to Prisoners relocated

to Theater Y, an abolitionist free theater in North Lawndale. Adequate future living spaces still remain uncertain for the migrants who collectively cared for each other.

El Comedor Comunitario, a place that offered and gave without asking, was forced to vacate. Still, Yus said it held immense joy for her. It was not only her home for a year and six months but also “my refuge, my roof, my safe place.” If circumstances allow, she would love to continue to cook for people in need.

Yus and other contributors protected and held on to this home in all the ways they knew how, in the narrow spaces to be cleaved out in Chicago.

“I take with me many beautiful memories, and others not so much,” Yus said. “But with the satisfaction that I gave everything of myself for this beautiful project.” ¬

Chelsea Zhao is a Chicago-based freelance journalist who is passionate about covering immigration, health advances, scientific research and civil rights. She works full-time in healthcare and received her MSJ from Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. Her previous works appeared in WebMD, Chicago Health Magazine, Caregiving Magazine, Northwestern Proteomics, Cicero Independiente, etc. In her free time, she likes to rollerskate, take photographs and draw storyboards.

BY MAYA DUKMASOVA, INJUSTICE WATCH

This story was produced by Injustice Watch, a nonprofit news organization in Chicago focused on issues of equity and justice in the court system.

The scientist was on the witness stand explaining how marijuana affects the human body. Forensic toxicologist Jennifer Bash was called by the state as an expert witness, as she had been dozens of times before. But this case in DuPage County wasn’t the typical stuff of courtroom drama; there were no dead victims or tearful relatives in the gallery and no prison time in the cards for the defendant. He was charged with a misdemeanor DUI for allegedly driving under the influence of cannabis.

Late one night in 2017, Lombard police officers pulled over thirty-two-yearold Dwan Thompson for going seventeen miles over the speed limit. Officers suspected he was stoned, reporting he had watery eyes and a blunt in his cup holder. After conducting several field sobriety tests, officers still suspected he was intoxicated, so they arrested him and asked for a sample of his urine back at the station. The sample was sent to Bash’s lab at the University of Illinois Chicago, where she tested it for cannabis.

As he watched Bash testify, Kevin McMahon—who was less than four years into his legal career as a public defender and hadn’t had much experience challenging scientific evidence—grew annoyed, then outraged.

Leading up to the trial, McMahon had several lengthy phone calls with Bash in an attempt to understand her analysis of Thompson’s urine. “After two to four

Police. Her lab at UIC was accredited to international standards. Bash had tested blood and urine for alcohol and drugs “thousands” of times and testified as an expert witness more than 80 times before that day, she told the judge.

At trial, McMahon expected Bash to say she didn’t find any THC in his client’s urine, because the drug doesn’t show up in urine. Its metabolites—chemical byproducts created as the body processes drugs and other toxins—can be found in urine days, even weeks after last use, making them useless for determining whether someone is high while driving.

objection,” the judge said, “but I am not understanding.”

“She should not be allowed to testify to this,” McMahon objected again. But the judge wasn’t convinced.

Next, McMahon tried to fight Bash’s testimony with his own expert—a forensic toxicologist with decades of work experience in the Illinois State Police crime lab who had testified more than 100 times for the state and only one other time for the defense.

Toxicologist

conversations I still felt confused by the lab report,” McMahon told Injustice Watch. The report didn’t specify whether Thompson was over the legal limit for tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC—the component of marijuana that gets people high. “I was like OK, the way she’s describing it this guy is guilty…” and yet “I was still on the fence about whether to advise him to plead because I still didn’t understand if he was guilty,” McMahon said.

He reached out to a toxicologist at another crime lab for a second opinion. “And that’s when I knew I wouldn’t be pleading this out.”

Bash had extensive credentials: a master’s degree in organic chemistry, more than a decade of professional experience, certifications from the American Board of Forensic Toxicology and the Illinois State

On the stand, Bash, in her early forties with short hair dyed reddish pink, used complicated scientific terms to describe how the body processes marijuana and the steps she took to analyze urine. She explained how the body flushes the THC out with a “complex molecule called glucuronide” attached. She described how she performed chemistry on Thompson’s urine to separate that complex molecule from the THC and quantify how much of it Thompson had in his system.

Judge Anthony Coco, struggling to keep up, interrupted Bash. “You are saying glucon—?” Bash spelled it out: “It’s g-l-uc-u-r-o-n-i-d-e.”

The prosecutor continued her questions, driving Bash to her overall point: The metabolites of marijuana in Thompson’s urine were ultimately the same as the drug. By then, McMahon had done enough research to know that wasn’t true.

“I object,” McMahon said. “The scientific community does not treat these compounds as if they are the same.”

“I am going to overrule your

He confirmed THC and its byproducts in urine are not the same thing and said the State Police lab doesn’t test urine for DUIcannabis investigations. McMahon was hoping to make the judge understand there was no THC in his client’s urine until Bash converted metabolites back into the drug. But it was futile.

“This was a very interesting trial,” the judge said in a sincere tone after both sides finished their closing arguments. He found Thompson guilty on one count of speeding and not guilty of impaired driving based on the field sobriety tests. That left only the DUI-cannabis charge hanging on Bash’s lab analysis.

“As to the charge with all the science, a big reason I went to [law] school was because I stunk at math and I stunk at science,” the judge said, and announced he would take some time to review the transcript before ruling.

A month later the judge found Thompson guilty and sentenced him to court supervision, a two-year slog with hundreds of dollars in court costs stacking on top of the loss of his driving privileges, and many ninety-mile round trips from his home on the Far South Side of Chicago to

the courthouse in Wheaton.

McMahon remains convinced the judge made the wrong call by discounting testimony from the State Police toxicologist. But he said he was more stunned by what Bash said in court, and how confidently she testified.

Though Thompson appealed, he lost. The appellate court ruled it had no legal standing to override the trial judge’s decisions about expert witness credibility. As that ruling came down, McMahon’s office was flooded with more clients facing DUI-cannabis charges based on Bash’s urine testing—mostly low-level misdemeanors typically resolved through plea deals.

“We felt forced to dig deep,” McMahon said. “You have so many people you’re representing accused of things they’re not guilty of. … I just knew we gotta do something, we can’t just plead those out.”

Thompson, who otherwise had a clean driving record, is still baffled by his case. Regardless of what Bash said about his urine, he said in an interview with Injustice Watch, he knew he wasn’t high when he got behind the wheel of his black Nissan Altima the night he was pulled over.

He’d driven out to Joliet with a friend to catch his brother’s concert. Before the show, he smoked half a blunt. He was saving the other half for later and left it in the cup holder. By the time he got on the road after the performance it had been several hours since he’d smoked. After years of experience, he said, he knew his limits with marijuana and he was good to drive.

It would take more than six years for Thompson to be exonerated, along with more than a dozen other DuPage County defendants who had been convicted of lowlevel DUI-cannabis charges with the help of Bash’s lab work and testimony.

By then, Bash would resign and UIC would shut down her lab right as an accrediting agency’s audit uncovered a range of unacceptable problems in its operations. Prosecutors’ offices in some of the seventeen counties for which the lab provided testing would also issue disclosures to defendants about Bash’s “inaccurate and unqualified testimony.”

In a months-long investigation— including more than forty-five Freedom of Information Act requests, more than 100 interviews, and a review of some 8,000 pages of public records—Injustice Watch

found more than 2,200 cases in which body fluids were tested for THC by the UIC lab between 2016 and 2024. In addition to improperly testing urine for DUI-cannabis investigations, these sources indicate the lab was for years unable to differentiate between legal and illegal types of THC in people’s body fluids. Worse, internal records examined by Injustice Watch suggest the lab was aware of some of the problems in its testing since at least 2021 but continued to perform tests and report results to law enforcement, mostly in DUI cases. Bash, meanwhile, repeatedly testified about the lab’s findings in inaccurate and misleading ways.

“I take great pride in my work and have always conducted myself ethically,” Bash said in written responses to Injustice Watch questions. “It is deeply upsetting to be falsely accused.”

Injustice Watch also found university officials charged with overseeing the lab were focused on the lab’s financial performance, and not on the quality of its scientific work. According to internal emails, officials’ eventual decision to shut down human testing at the lab came as a result of its failure to generate revenue.

UIC officials declined interview requests from Injustice Watch but recently issued an internal investigation report exonerating themselves from oversight failures. The report concluded the lab’s methods were “at all times appropriate and met accepted scientific standards” and none of its analysts “knowingly provided false testimony in criminal proceedings.”

The investigation was conducted by outside attorneys specializing in business emergencies, class action defense, and white-collar crime. In May 2024, the lab sent a letter to prosecutors in more than a dozen counties reporting one problem in its testing methodologies going back years, but the lab did not report how many cases were affected or issue any corrected lab reports.

To date, the University of Illinois officials have not notified any defendants the lab’s test results of their body fluids may have been wrong. While Thompson’s record was cleared after years of legal battles, defense attorneys estimate hundreds of other people are still dogged by criminal convictions based on the lab’s work and Bash’s testimony. Some are still awaiting trial on DUI charges stemming from her work. At least two people are serving prison

sentences.

The Injustice Watch investigation reveals lax oversight over forensic labs in Illinois, which has a long history of wrongful convictions based on junk science. Despite recent reforms to improve the quality of forensic science, the state is not prepared to stop another crime lab from going rogue.

UIC’s Analytical Forensic Testing Laboratory opened in 2004 when the Illinois Racing Board began using the university to test racehorses for illicit drugs. Bash began working at the lab in 2015, taking a $31,000 pay cut from her prior job as a forensic toxicologist with the Illinois State Police.

By the time she began working there the lab had half a dozen full-time employees, an annual budget of $1.5 million and was testing up to 20,000 horse samples annually. It received coveted accreditation from ANAB, the National Accreditation Board of the non-profit American National Standards Institute.

But the horse racing industry in the state was in decline amid the rise of Internetbased gambling options; two of the state’s four racetracks closed in 2015. The UIC lab was looking to pivot.

In her written response to Injustice Watch’s questions, Bash said she took the job at UIC because building up the lab “was a great career opportunity.” At the time she started, Bash wrote, “no one at the lab had experience conducting human testing.”

According to her hiring documents, Bash’s job duties included helping find “state and private agencies which require forensic toxicological analysis in humans to … assist in bringing their business to our

laboratory.”

As one of the University of Illinois’ “self-supporting units,” the lab had to cover its own operating costs through selling its services and obtaining grants. According to university policy documents, such independent units are expected to support their teaching, research, public service, or economic development missions and to operate like a business “with one important exception: a self-supporting Fund must break even over time. The Fund should not generate a profit or incur a deficit.”

Bash told Injustice Watch she “wasn’t told anything regarding revenue goals.”

The lab was housed in a low-slung concrete building on Harrison Street, inside the Pharmaceutical Sciences Department at the UIC College of Pharmacy. Yet Injustice Watch could find no evidence anyone at UIC or the broader university bureaucracy knew much about the scientific work happening there. The university’s lawyers confirmed this in their recent internal investigation report, which emphasized officials were “unaware of any of the allegations” against the lab as late as March 2024.

Bash’s boss, lab director A. Karl Larsen, was a seasoned lab administrator. They had worked together at one of the State Police crime labs in the early 2000s. A waiver of open job search procedures was requested for Bash’s hire, describing her as “very qualified as a forensic research specialist” with fourteen years of experience.

Larsen declined Injustice Watch’s request for an interview but said through his attorney he “stands behind his work and the work of the Lab.”

As Bash got the UIC lab’s human

testing services running, the years-long battle to legalize marijuana in Illinois achieved a major milestone. In the summer of 2016, possession of small amounts of cannabis was decriminalized, and the state legislature also amended the impaired driving law to include specific reference to cannabis.

There are two ways to be guilty of DUI—by failing field sobriety tests or having certain quantities of alcohol or drugs in your system. Regardless of someone’s ability to walk a straight line, blowing 0.08% or more on a breathalyzer can result in a DUI conviction.

Lawmakers sought to create a similar legal limit for cannabis. The problem, though, was a lack of scientific consensus on how much THC in the body equals impairment. Even more than alcohol, THC affects different people differently, depending on body size, frequency of use, and other individual factors. To make matters more complicated, there are no breath tests to determine cannabis levels in the body.

By the time Illinois lawmakers were puzzling over the problem, several states had DUI statutes that explicitly referenced cannabis, and most of them had a zerotolerance policy. The states that did set legal limits opted for 5 nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood or less—a limit unsupported by science but tolerable for law enforcement.

When lawmakers initially passed a bill with a higher limit, then-Gov. Bruce Rauner vetoed it, saying he would only go as far as other states. In 2016, the legislators yielded and Rauner enacted the legal limit of 5 ng of THC per mL of blood and 10 ng/mL of “other bodily substance,” which wasn’t defined in the law. For some attorneys and scientists the language implied saliva, but cannabis tests using it were still in their infancy.

At the State Police-run labs, forensic scientists determined that only blood testing would provide accurate results for DUI investigations under the new law. But at the UIC lab, Bash and Larsen took the law to mean urine testing was fair game.

Because of the vague statute, Bash told Injustice Watch, “the lab decided to provide the information objectively and allow the attorneys, judges, and courts to interpret the law as is appropriate.” To provide information on the amount of THC in

urine, Bash used a testing method that converted metabolites back into the drug.

No other lab in the country offered to quantify THC in urine for Illinois prosecutions.

After cannabis was added to the DUI law, the lab’s invoicing for cannabis testing skyrocketed. University financial records show the lab billed just ten law enforcement clients for a total of $4,455 for cannabis testing in 2016. The following year the lab’s client list grew to seventy-one agencies with total billing of $37,650, most of which was done specifically for DUI investigations, records show.

“The demand grew rapidly and we developed a backlog,” Bash told Injustice Watch.

The lab was particularly popular in suburban collar counties. Law enforcement from Lake, McHenry, Kane, DuPage, and Will counties accounted for about onethird of its cannabis testing business in

Still, the UIC lab analyzed hundreds of human samples for THC and its metabolites every year, mostly for DUI investigations. In total, it issued more than 2,200 reports on human blood and urine samples tested for cannabinoids between 2016 and 2024, according to statistics obtained by Injustice Watch. The university denied a request for the underlying lab reports, and Injustice Watch has filed a lawsuit against the university to obtain them.

While scientifically unfounded quantification of THC in urine continued at the UIC lab, at the end of March 2021, internal records show, the lab documented another problem—one the lab later acknowledged had compromised the integrity of its blood testing, too.

“Apparently some folks are having problems with the detection and separation of Delta-8 and Delta-9-THC,” Larsen wrote to Bash and two junior analysts. “Has this been an issue yet?” Bash, who by then had been promoted to an additional role as the lab’s quality manager, wrote back she would have one of the junior staffers check.

On March 31 the junior staffer ran the test, according to lab records filed in court. The lab’s machine showed it was not seeing the difference between the two types of THC. The email conversation among the lab personnel about the issue dropped off. After that, Bash told outsiders in emails the lab had no problem distinguishing the THC types while internally Bash and Larsen acknowledged they did.

Meanwhile, the State Police labs, which had discovered the same problem, were scrambling to fix their blood-testing methods.

“I describe it as chemical heresy,” pharmacologist James O’Donnell said of Bash’s methods and testimony.

2017. The following year it was more than half. This growth was driven in large part by DuPage County clients, in particular the Carol Stream Police Department, which has a reputation for aggressive DUI enforcement.

“We were more active in drugimpaired driving arrests perhaps than other agencies,” Carol Stream Police Department Deputy Chief Brian Cluever told Injustice Watch. Testing urine in DUI-cannabis cases “was important because it was less invasive than having to collect the blood,” he added. “With blood you have to have a certified phlebotomist to do that.”