Maggie Malone | Editor-in-Chief backdropmag@gmail.com

Maggie Malone | Editor-in-Chief backdropmag@gmail.com

Hello Reader,

Thank you for picking up Volume 19, Issue 2 of Backdrop magazine. By the time this issue reaches you, the leaves on College Green will have almost entirely thinned out, and fall semester will be coming to a close. Although campus is inching toward its winter break hibernation, our team’s drive to produce and deliver high-quality stories has not slowed down.

In fact, our momentum has only grown as our staff has expanded. We have had the honor of welcoming fresh faces to our writing, editing, photography and design teams, all of whom displayed excellence in the work they produced. Some writers even worked from across state lines to produce their articles, which was a challenge that did not stop them from putting together outstanding stories. You will find our team’s collective efforts in coverage that digs deep into Athens’ identity and the realities of campus life, alongside pieces that celebrate the small details that make up our vibrant community.

Senior writer Darcie Zudell reports in depth on the effects and pushback of recent federal immigration partnerships in this issue’s feature (pg. 22). Sophomore writer Madeleine Colbert highlights an underutilized archival resource within Ohio University Libraries (pg. 8). Assistant Social Media Director and writer Parker Jendrysik investigates whether OU’s party culture has changed in recent years (pg. 30).

Thank you to our first-time writers, designers and photographers Kendal Akers, Luciana Avila, Nora Dahlberg and Lilly Cochran, whose contributions were impressive and crucial. As always, thank you to our readers for supporting student journalism. We hope you enjoy reading this issue as much as we enjoyed creating it.

For resources and information on how to protect yourself, your loved ones and our community, visit immigrantjustice.org.

Interested in working with us?

Backdrop magazine is an awardwinning, student-run magazine aimed at covering current events and culture with OU and Athens as our "Backdrop." We have positions available for:

• Writers

• Photographers

• Designers

• Copy Editing

• And more! Want

Send an email to backdropmag@gmail.com or to our Marketing Director, Julian Hall at Jh126321@ohio.edu to get started!

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MAGGIE MALONE

MANAGING EDITOR MIYA MOORE

COPY CHIEF SUZANNE PIPER

SECTION EDITORS LUCY RILEY, LILIA SANTERAMO, LUKE WERCKMAN

COPY EDITORS NORA BARNARD, ETHAN HERX, RUBY JOHNSON, CARLY KUNKLER, TAYLOR MURRAY, SUZANNE PIPER, LUCY RILEY, OLIVIA TROWBRIDGE

WRITERS KENDAL AKERS, LUCIANA AVILA, NORA BARNARD, MADELEINE COLBERT, ZOE DUNCAN, PARKER JENDRYSIK, TORI KYER, MIYA MOORE, LUCY RILEY, LILIA SANTERAMO, LIAM SYRVALIN, DARCIE ZUDELL

MARKETING DIRECTOR JULIAN HALL

ASSISTANT MARKETING DIRECTOR DIVY BOSE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR ALLY PARKER

ART DIRECTOR MATTHIAS AGGANIS

DESIGNERS MATTHIAS AGGANIS, SOPHIA CIANCIOLA, LILLY COCHRAN, ELIZABETH DICKERSON, ZOE DUNCAN, SONNY JAY, JULIA PARENTE, ALLY PARKER, ELLIE SABATINO, TOBY SUTHERLAND, CLAIRA TOKARZ

PHOTO DIRECTOR CLAIRA TOKARZ

PHOTOGRAPHERS LILLY COCHRAN, NORA DAHLBERG, CLAIRA TOKARZ

SOCIAL MEDIA DIRECTOR ELIZABETH DICKERSON

ASSISTANT SOCIAL MEDIA DIRECTOR PARKER JENDRYSIK

DIGITAL DIRECTOR JULIA PARENTE

VIDEO DIRECTOR ZACH BAIC

ASSISTANT VIDEO DIRECTOR TORI KYER

Students and advocates across Ohio are urging universities to reject federal immigration partnerships.......................................................22

ROOTED IN ZEN

Just beyond OU’s campus lies a tucked-away wellness sanctuary .................... . . .....6

UNTAPPED STACKS

The often-forgotten branch of Ohio University Libraries ............. .......................8

STREET ART IN ATHENS

The city hides a rich collection of public art for those who take the time to look .. ............10

LIFE OF A ROCKSTAR

Brogan Bosworth has the best of both worlds as a student by day and a rockstar by night ......12

A CROCK-POT MEAL FOR WHEN YOU MISS YOUR MOM

Cure your homesickness with this ham and bean soup recipe . ..

.14

An intimate look at visual identity reflected in personal spaces .............................16

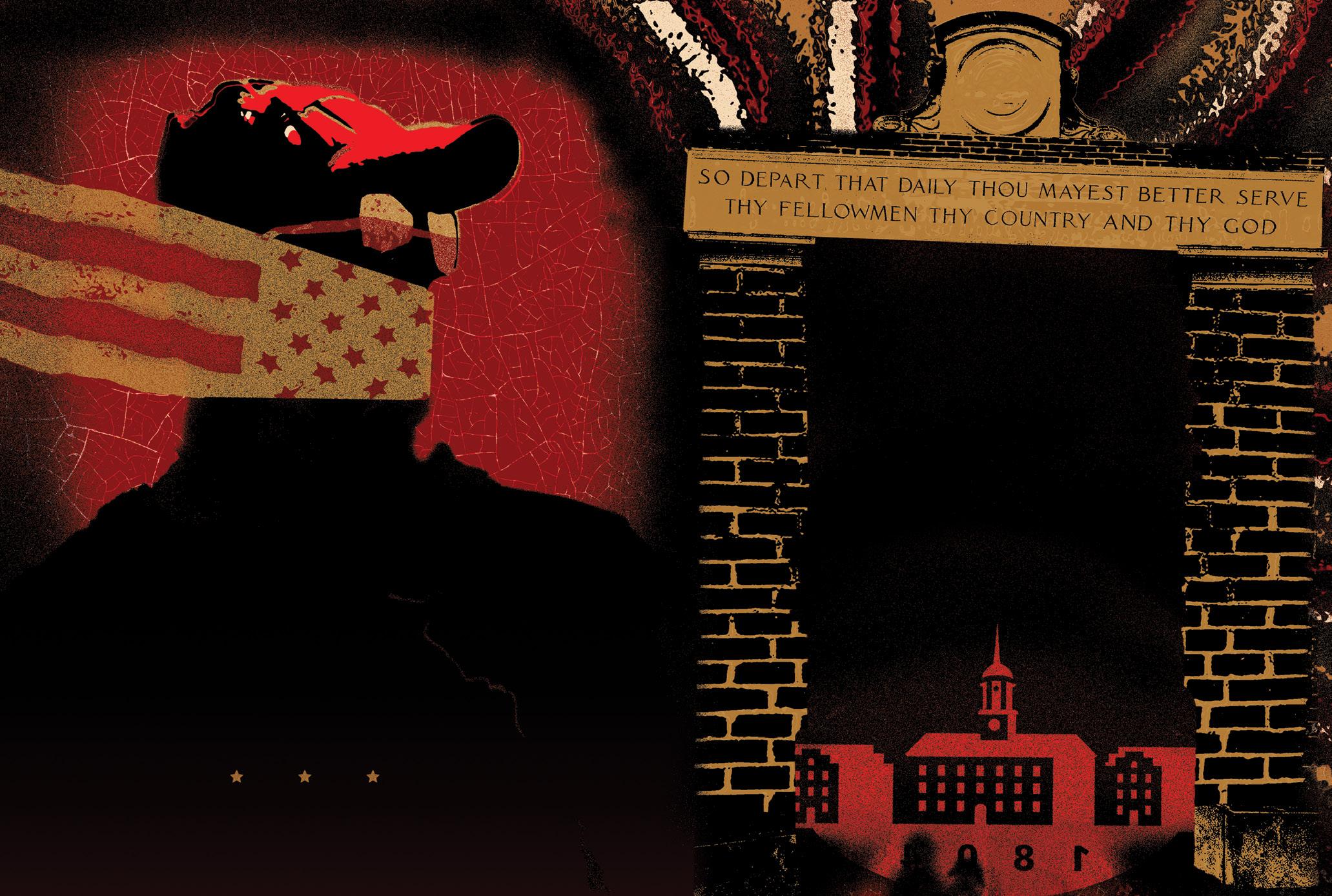

GLORY TO THE DRAFT DODGERS! GLORY TO THE DESERTERS!

The unsung heroes of the Vietnam War ........26

ASOCIAL MEDIA

The pitfalls of digital communication platforms.................................. .... 28

PURITY PANIC

An interrogation of a trending ethos . ...........30

OH, YOU PARTY?

While in the past, OU has been known for its party scene, students now question whether the culture has shifted................................. .... 32

A NEW PECKING ORDER

Raising Cane’s arrival tests Athens’ appetite for national brands and its loyalty to homegrown favorites . ...................................36

HALFWAY BETWEEN HERE AND THERE

A personal reflection on reverse culture shock and its effects . .....................................38

Just

BY LUCIANA AVILA | PHOTOS BY LILLY COCHRAN & NORA DAHLBERG | DESIGN BY ALLY PARKER

Just a 10-minute drive from campus, students can find an escape from the craziness or chaos of college life. Serenity Roots Yoga and Wellness Center sits on four acres of gardens and woods, housing a variety of yoga classes and other activities. It’s a place where students and community members can come to relax, de-stress and wind down. Whether it’s simply sitting by the fireplace or partaking in a yoga class, Serenity Roots has something for everyone.

A little over two years ago, Serenity Roots opened its doors.

“Serenity Roots became a sanctuary for my healing,” she says. “A combination of yoga and meditation and being surrounded by four acres of gardens, woods and nature helped me through the grieving process.”

Courses are taught in a large room in the studio that overlooks a tall hill and vast nature. The windows let in natural sunlight and a view of trees and wildlife. On the property, you can find flower beds, a goldfish pond, a bonfire, a natural amphitheater and many quiet areas, which are all part of what helps make up the peaceful atmosphere. Several types of yoga classes are

teaching,” she says. “Whether it's the first time you're taking yoga or you're more advanced, they teach at all the different levels and so many different styles.”

Meditation and focusing on holistic health can offer various benefits. Not only does it serve as a de-stresser, but it also helps improve overall physical and mental state. It helps to clear the mind and focus on the present. Painter acknowledges the importance of holistic health and how it can have a positive impact on oneself. “It’s about realizing how you can help treat and heal your own body and learning more and more about what you can do for yourself,” Painter says.

The scenic atmosphere of Serenity Roots allows the space to be used for other events and meetings. Businesses and organizations can host their workshops, retreats, relationshipstrengthening sessions and other events there. The tranquility and seclusion of it allow for a more intimate and nature-based experience that can be hard to get at a hotel, a conference room or other venues. The wellness center also hosts its own events and workshops that include activities like candle making and tarot card reading.

Serenity Roots also houses two book clubs. One of them focuses on health and self-improvement. It’s a space to share and discuss holistic and wellness ideas. Past topics include Mediterranean diets, learning more about yoga and Reiki and how to improve at meditation.

OhioHealth HomeReach Hospice hosts its grief book club at Serenity Roots. The club meets monthly, discussing a different book each meeting. Every book covers topics of grief and healing, and how they may look and differ in varying situations. The club creates a safe space for community members to engage in conversations about death and personal experiences.

Discussions are led by OhioHealth HomeReach Hospice bereavement counselor Kelsey Funk. She has been with OhioHealth for six years and is very passionate about grief. She met Painter while searching for a place to host the club.

“I happened to meet Carin at the hospital, essentially. And we just connected,” Funk continues. “She was very happy to be able to provide a space for us to have this important topic in our community.”

Funk is in charge of leading the discussions. Her role as the facilitator is to ensure that the meetings are productive and meaningful. Attendees are not required to speak or share their last name or any personal information at the meetings.

Funk encourages everyone to attend, regardless of age or

BY MADELEINE COLBERT

DESIGN BY SOPHIA CIANCIOLA

The library holds countless resources, yet Alden never seems big enough to contain them all. That's where the Hwa-Wei Lee Library Annex comes in. Located at 205 Columbus Rd., it's just a short drive away from campus, though many students have never heard of it or realized they’ve used it.

The Hwa-Wei Lee Library Annex contains a collection of rare and historical books, photography, journals, art and more. The materials are found both digitally and physically, and the annex’s staff members work to archive them in a variety of different ways. For example, Aurora Charlow, the annex's digital archivist, works to preserve, organize and restore the digital media found in the annex.

“I keep track of, arrange and describe the materials in the archives. They’re referred to as born-digital materials, and that just means anything that never had a physical component. It covers stuff that's on an optical disk … and goes as far back as floppy disks,” Charlow says.

Charlow is currently working on archiving a photography collection from Dan Dry, who donated his collection, valued at $4.3 million, to Ohio University Libraries back in January 2024. The collection includes between 1 million and 6 million photographs. As seen with Dry’s collection, many of the pieces in the annex are donated by individuals or their families, but not everything found in the annex and library is obtained through donation.

“A lot of our archives and special collections

come to us through donation, but most of our circulation collection is acquired by the library using their acquisitions budget … sometimes that's electronic access and sometimes it's a permanent purchase,” says Miriam Nelson, the director of Mahn Center, Preservation and Digital Initiatives.

The collection of both donated and purchased materials is stored in a giant depository located in the annex. Filled with shelves to the ceiling, the depository contains anything you could think of, ranging from books and journals to VHS tapes.

“We have 650,000 library items out here,” says Sandy Gekosky, a library support associate and preservationist.

The annex works within Ohio’s state depository system, which includes five different depositories located at different colleges throughout the state. The system allows statewide circulation of these archival materials. It’s also part of why students are able to request and use so many different resources through the university.

“People request things that are stored out here. So three days a week, things get delivered to Alden so that people can pick them up there, or they go out through OhioLINK,” Nelson says.

Outside of organization and storage, the annex works to preserve and protect old and rare items. This involves a multitude of different methods, such as building housing or boxes, to protect smaller, rarer or more fragile library items.

“I’m working on the housing that protects these items so that they don’t get damaged in transit or when they’re displayed. I’m making these folders and custom binders that house them ... so we have the ability to pull them out in a way that a person’s not handling them that much,” Gekosky says.

Beyond preventative conservation, staff also work on interventive treatment

for their circulating collections: the collections available to borrow. This includes rebinding, or resewing spines and small paper mends. Many of these repairs are done on the second floor of the annex, and antique machinery is used to complete them, with one machine originating in 1903. The annex receives a variety of different materials that need repair. These materials are often sent to the annex from other parts of the library system. “They’ll send us a preservation form, and they’ll check off ‘spine’ or whatever they think needs work for us to complete,” Gekosky says.

As a whole, the annex’s main goal is to store and preserve materials for researchers to use in their work. Through their giant depository, they frequently make new, different, rare and unique materials available. “Most of what happens out here is work on or with the collection, so we can make them accessible to people doing research. You can absolutely come out here if there's something you want to see that's stored in the depository ... they will also go back to Alden Library in archives and special collections, and so they’ll be made available there,” Nelson says.

Why does this matter to students? Without the work of the university library system, students wouldn’t have access to many of the resources used in day-to-day research. For example, the library’s acquisition budget is why students now have access to the Criterion Collection. Beyond that, the annex is another asset available to students that commonly goes unnoticed or overlooked, even though it contains multitudes of materials that could aid research or simply pique someone's curiosity.

“I would encourage people just to be aware that we do store this material out here ... students should know they can reach out,” Nelson says. b

You can walk down Court Street a hundred times and never notice the graffiti tags on an alleyway corner, a sticker curling on a stop sign or the story behind a mural. Athens hides its art in plain sight.

In Athens, art is not limited to galleries or someone's social media page. It breathes through the city’s bricks and alleyways. These details and expressions — some planned, some impulsive — brand Athens with its connectivity and identity.

Local artist Keith Wilde is the creative mind behind some of the murals that might appear on your daily route.

“I was just a person that always kind of comes back to art,” he says.

In 2015, an explosion of color swept through Athens as murals began appearing more frequently.

“Graduate students, professors, local artists, even locals started putting color on the walls,” Wilde says.

Projects such as the mural titled “Without Labor, Nothing Prospers” on Court Street, led by visiting artist Chris Stain, marked a new chapter for the town.

“That’s what makes Athens different,” Wilde says. “Our stories, our aspirations, even our beliefs, they all come out through how we use color and space.”

For Wilde, murals are not just background images, but reflections of the community itself.

“You can look at what kinds of murals show up in which towns and see what each community values,” Wilde says. “In Athens, we tell different stories because we’re a different kind of community.”

The city hides a rich collection of public art for those who take the time to look

BY TORI KYER | PHOTOS BY CLAIRA TOKARZ | DESIGN BY ELIZABETH DICKERSON

Many of these pieces highlight local history, from the African American brickmakers of Stimson Avenue to figures celebrated at the Mount Zion Black Cultural Center.

“A lot of people don’t know those stories,” Wilde says. “Public art makes them visible again.”

Still, visibility remains a challenge.

“How many murals do you think we have?” Wilde says. “Most people start to count on their fingers which [murals] they have seen. It’s closer to 50.”

Some of the murals hide in alleyways or in neighborhoods. According to Wilde, that habit of inattention runs deep in modern life.

“We live in the age of distraction,” Wilde says.

He argues that if everyone is nose-deep in their phones, they will miss the beauty and art around them.

“Once you see one, you start seeing them everywhere,” Wilde says. “It’s like meeting someone new; you start noticing them all over town.”

“[Street art] strengthens cultural identity by enabling residents to connect with their environment, promoting pride and place attachment,” according to a 2025 research report titled Street Art for Urban Regeneration: Cultivating Community Identity, Social Cohesion and Economic Growth by Minjae Kang. The report cites a study by the National Endowment for the Arts, which found “respondents reported a 60% increase in interaction with neighbors following public art projects.”

Community groups in Athens are working to help people learn more about this valuable visual language. Ohio University’s mAppAthens project treats the city as an openair museum, pinpointing public artworks and cultural landmarks. According to the mAppAthens web page, “this interdisciplinary collaborative project offers online maps that can be leveraged as outdoor museum tours to engage visitors of all ages in active, place-based learning experiences to explore an array of topics including art, wellness, history, geology, ecology and more.”

Local nonprofits, such as the Athens Municipal Arts Commission, also organize mural walks and scavenger hunts to draw attention to neighborhood art.

“It’s about getting people to walk around, look around and connect,” Wilde says.

Athens is home to countless creative individuals, and these expressions form the core of the town’s whimsical, welcoming identity. Even the bathroom stalls of Court Street bars are filled with doodles, quotes and signatures — small reminders of how people leave their mark. In the age of digital media, it is easy to overlook the art that surrounds us, but in Athens, creativity is always present and waiting to be noticed.

Brogan Bosworth has the best of both worlds as a student by day and a rockstar by night

BY NORA BARNARD | PHOTOS BY CLAIRA TOKARZ & NORA DAHLBERG | DESIGN BY ALLY PARKER

As a fourth-year student studying creative writing and entrepreneurship by day, then playing a packed show by night with her band, Girl Idiot, Brogan Bosworth is Ohio University’s own rock ‘n’ roll Hannah Montana. Get the inside scoop on Bosworth's daily life as she navigates college, a job and band life.

HOW DID THE BAND GET TOGETHER?

We’ve been together for about two years now. I was scrolling through Instagram, and I kept seeing all these bands, and I've always wanted to do that. It's been on my bucket list forever, and already been singing thought, “I just need to a post saying, “I'm interested in putting a band together. If anyone else is interested, we'll need some instruments: like a drummer, a guitarist and a bassist.” I actually had a lot of people reach out, which was really nice. So I got to sort through all those and host some, I wouldn’t say interviews, but we did audition and see how the group fit together. After a while of trying to find people who fit our approach and could commit the time and energy, we have the group we have now, and it's a pretty great group.

WHAT IS YOUR ROLE IN THE BAND?

I sing and play bass too, but our bass player is incredibly talented, so it’s not often needed.

HOW MANY CLASSES ARE YOU IN THIS SEMESTER?

This semester, there are just five. I'm doing a business cluster, which is very demanding. So just five right now, but usually there are a lot more.

Depending on the day, I usually wake up at 8 or 9 [a.m.]. When I wake up at 8, I go to the gym in the morning before class. If it’s 9, I get up, make breakfast, do my makeup and put on some clothes. The business cluster starts around 11. That's every single day. I sit in the basement of Copeland Hall for three hours with the same group of people, because it's a group project for the whole semester, and them for three hours. Then, usually after that, I have a class that backs up directly to the business clusters, so I cross the street and go sit in another basement for an hour [and] listen to a history lecture.

I just started a new job, so I'm doing that. I'm a line cook up at Jackie O's. I've been working in the restaurant industry for about four years, doing line cooking, and I always find my way back to it. Currently, I go home at 3 [p.m.], have about 40 minutes, and then I head straight to work until 9 or 10 p.m. If I don't have work, then I usually do some light homework. I live by myself right now, so it’s just me and my two cats, Oliver and Alice.

Usually twice a week for two or three hours. We used to practice in the CMDI room in Glidden, but we have lost access since our guitarist is no longer a student in the CMDI program. So now we are in the drummer's attic, which I'm sure his roommates love. It's a tight space, but there are a couple of couches, and we set everything up.

HOW OFTEN DOES YOUR BAND PLAY SHOWS?

Last semester, we had a good stretch where we were playing a show almost every weekend, which was exhausting. We were trying to learn new material in between shows to bring something new to each one. We currently average about one or two shows per month.

WHAT HAS BEEN YOUR BEST PERFORMANCE?

We had an outstanding show at The Union early last semester, about this time last year. I called it our "Blood Sugar Show," just because we were playing “Blood Sugar Sex Magik” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but we had a really good crowd going. We also conducted “The Biggest Cover-Up” last year, which took place at The Union. We covered Pearl Jam, and the turnout for that was just amazing. The Union was packed. Another memorable one, we played up in Cleveland at the Grog Shop over the summer. I'm from Cleveland, so we got everybody out there and really pulled something out of our ass, because not all of us live close to each other. We just practiced in the morning, and then we went straight to the show.

HOW OFTEN DO YOU PRACTICE ON YOUR OWN?

All the time, especially now that I live by myself. I used to go sit in my car, drive around for a while and practice,

and I'm like, “Man, you guys, not to be biased, but that is so good.” It really is so special to be able to come together with some really talented people and make something that is entirely our own. It's such a good sense of community and group, and being able to depend on each other.

WHAT IS THE MOST DIFFICULT PART OF BEING A STUDENT AND A LEAD SINGER IN A ROCK BAND?

The time. Trying to find the time and trying to balance all of my commitments. I set myself a high standard academically, to make the time to get all my work done at the quality that I wanted, and then make time to practice music. And I always write everything out so I have it. So that takes hours at a time. I'd say, really, balance. It is so hard. And sometimes, I say to myself that sometimes you have to do it tired, and I find myself doing that a lot, especially now that I've added work to the mix.

I think music's always been a part of my life. It'll always be a part of my life. I don't know what the fate of the band is. I can’t say I would be mad at it either way; if it fizzles out on its own or if it keeps going. It's something that we take with us, and I'm happy to see where it takes me. Other than that, I'm sure I'll find my way back on a

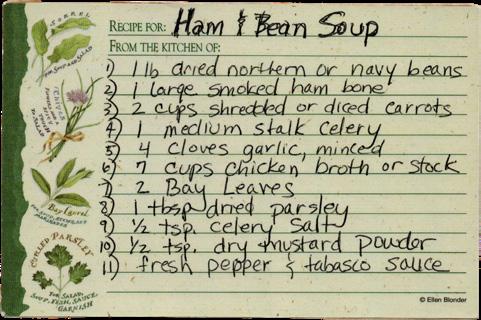

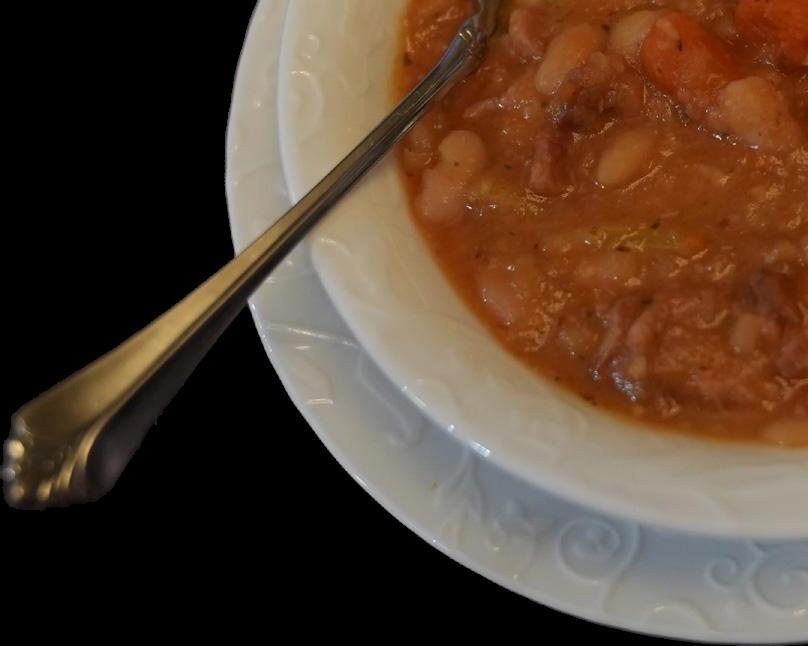

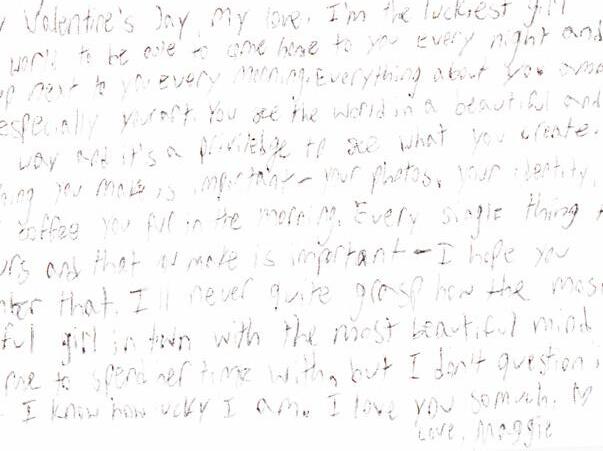

Cure your homesickness with this ham and bean soup recipe

It’s that time of year when the weather gets colder and the days get shorter — crunchy leaves, NFL football, dive bars with Christmas lights, leather and denim. Consequently, this is also the time of year when homesickness really comes to a head. As the ‘ber months come around, the yearning for a home-cooked meal sets in like clockwork. The nostalgia for my mom’s meals is particularly strong — especially when they’re straight from the Crock-Pot.

This is the best time of year to replicate some cozy recipes from home, so I thought I’d share one with all of you, handwritten by my mom for Backdrop magazine: Mrs. Moore’s very own Ham and Bean Soup! It’s a little labor-intensive, but worth every bite. b

1 pound dried northern or navy beans

1 large smoked ham bone

2 cups shredded or diced carrots

1 medium stalk celery

4 cloves garlic, minced

7 cups chicken broth or stock

2 bay leaves

1 tablespoon dried parsley

½ teaspoon celery salt

½ teaspoon dry mustard powder

Fresh pepper & Tabasco sauce to taste

1. Soak the beans overnight (or rinse and drain them) and put them in a large Crock-Pot

2. Nestle the ham bone into the center of the beans

3. Add the rest of the ingredients to the Crock-Pot

4. Cook on either: low heat for 7-9 hours or high heat for 4-5 hours. Cover and cook until the beans are tender

5. Optional: For thick, creamy soup, partially puree the soup in a blender

6. Shred ham from the bone back into the soup

7. Stir thoroughly and enjoy

An intimate look at visual identity reflected in personal spaces

An look at visual identity reflected in personal spaces

BY DARCIE ZUDELL

Students and advocates across Ohio are urging universities to reject federal immigration partnerships

In recent years, international students across the U.S. have faced heightened scrutiny, with some having their visas revoked or denied reentry into the country because of statements made online or political participation perceived as critical of the U.S.

Lately, immigration enforcement has also intensified nationwide, and college campuses have found themselves caught in the middle. One of the primary mechanisms for this cooperation, the 287(g) Program, lets local and state police perform certain duties traditionally handled by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, also known as ICE.

The Trump administration encouraged the use of these agreements, originally created in 1996, to let local police perform certain immigration duties traditionally handled by ICE. Today, the program is among the most controversial tools in federal immigration enforcement.

“We feel like everything we do could be on their radar, and that doesn’t feel safe at all,” says an undergraduate student from Vietnam who asked to remain anonymous, and will be referred to as Student A.

Her fears are not unfounded. In 2016, only 32 agencies held 287(g) agreements; today, that number exceeds 1,000 across 40 states, with six active and three pending in Ohio.

To Natalie Johnson, an advocacy strategist for the Ohio American Civil Liberties Union, also known as ACLU, the growing number is concerning. The organization recently sent letters to every university in Ohio explaining 287(g) and reminding them of their right to decline participation.

The ACLU chapter at Ohio University also circulated a petition urging university leadership to make that rejection public. This outreach felt urgent to Johnson after noticing a troubling pattern in other parts of the country.

“In states like Florida, we saw an extremely alarming [trend] where universities themselves were actually signing these agreements,” Johnson says.

The majority of Florida’s public university police forces are now in active 287(g) agreements with ICE. The University of Central Florida and the University of Florida entered agreements in April, followed by Florida International University in July, which are among three of the state’s largest public institutions.

“[ACLU Ohio] realized colleges are the epicenter of this fight, not just for freedom of speech, but for immigrant rights,” Johnson says.

287(g) agreements operate under three models: Jail Enforcement, Warrant Service Officer and Task Force. The Task Force Model, reinstated under Trump after being outlawed due to concerns of racial profiling,

allows officers to enforce immigration law during duties such as traffic stops.

Johnson says police often enter these agreements for financial incentives. ICE now offers quarterly awards to participating agencies, and with declining incarceration rates, empty jail beds create new motivation to partner with ICE.

The ACLU chapter at OU argues these agreements will discourage people from calling the police out of fear it could trigger immigration enforcement.

“It's going to cause people to get harmed and be unsafe because of the mass amount of immigrants we have here,” Theo Nalley, a third-year student studying political science, pre-law and a member of ACLU’s OU chapter, says.

Lynn Tramonte is the executive director and founder of the Ohio Immigrant Alliance, an organization she launched in 2007 that gained nonprofit status in 2023 after successfully advocating to end two ICE contracts. Today, Tramonte focuses much of her work on immigration jail monitoring and encourages people with loved ones detained by ICE to share their experiences.

In Ohio, county jails sometimes serve as holding facilities for people detained by ICE. Tramonte says many of those held in these jails are given little time outdoors and have limited contact with family members. She describes the conditions as a “deprivation of liberty.”

“They're locking people up who were working and paying taxes in county jails, and at our expense,” Tramonte says. “[ICE is] taking them out of the workforce, and then we are paying to put them in these county jails.”

Amid increasing restrictions on immigration policy in 2019, retired OU faculty member Anne Sparks and a group of Athens community members founded the Athens United Immigrant Support Project (AUISP), which is now a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit.

Run by a volunteer board, AUISP sponsors people in immigration detention, helps them avoid homelessness and supports them as they work toward economic selfsufficiency. The nonprofit connects immigrants with legal, financial and housing resources while also offering flexible, individualized support.

“Particularly with the international [student] community, we're sensitive to their lack of future predictability regarding policy,” Sparks says. “I think that's one of the stresses that they're all experiencing now.”

Though AUISP operates independently from OU, the group has helped connect people with the linguistics department’s “English for All” classes. Through social media outreach, the nonprofit also distributes red cards, which are double-sided cards that inform immigrants of their constitutional rights when interacting with law enforcement or immigration officials.

With new 287(g) agreements signed every day and videos of violent and public deportations, many international students feel an exhausting sense of uncertainty -– an agonizing fear that stops some from participating in peaceful protests, speaking to press or even traveling back to their country of origin during semester breaks.

Student A has not traveled home to Vietnam in nearly two years. She planned on making the trek in July, but canceled her ticket due to anxiety regarding her immigration status being questioned, or even revoked, when returning to the U.S.

“I feel like it's not safe going home right now,” Student A says. “If anything happens, I would risk my whole degree here. [On] social media, I saw [friends] going out and visiting their parents, and I was like, ‘I wish I could do that.’”

Student A says she feels respected at OU, and that the school has a generally welcoming attitude toward international students, but she and her peers cannot help but feel uneasy about the evolving political climate surrounding immigration and higher education.

Another international student from Pakistan pursuing a doctoral degree in education, who also asked to remain anonymous and will therefore be referred to as Student B, says the fear among international students is undeniable. As a researcher in higher education, Student B is concerned about declining international student enrollment.

There is reason to be concerned, as international student attendance has dropped sharply. According to Inside Higher Ed, international student arrivals fell by 19 percent between the falls of 2024 and 2025.

“The number of international [students] aspiring to come to the U.S. is not going to decline in the future,” Student B says. “It's already on the decline in these times. Universities are able to function the way they [do] because of international students. They bring in a lot of money [and] a lot of labor that makes the university run.”

According to NAFSA: Association of International Educators, international students added more than $40 billion to the U.S. economy in the 2023–2024 academic year through tuition, housing, dining and local spending. Their presence helps sustain thousands of jobs at universities, particularly in smaller college towns such as Athens, where enrollment directly impacts the local economy.

“We have to stand up to authoritarianism because they’ll kill the entire institution of higher education,” Tramonte says. “They’re chipping away at international students so institutions are unable to exist, so that programs their tuition helps pay for crumble. We have to fight for our education, and that means we need to fight for our international students.”

With international student enrollment declining in America and the growing caution among immigrants, students such as Maeve McKeown, a junior studying English and political science, say it is more important than ever to show up for international students who may feel too afraid to speak out. She believes connecting with international

students can invite meaningful relationships.

“I think that people just need to be more involved in their community these days,” McKeown says. “Making connections with people and realizing how we're all very similar, and [that] you got more in common with a trans, undocumented immigrant than you have with literally any politician ever.”

McKeown is the social media manager of OU’s chapter of Young Democratic Socialists of America, a group that often works with other organizations to draft letters and petitions on campuses. As a student terrified of the idea of OU entering a 287(g) agreement, McKeown just wants reassurance from university leadership.

Across Ohio campuses, student organizers seem to want the same sense of clarity.

Matt Grogan — a third-year at Oberlin College studying political science and law and society, and a current ACLU Ohio Campus Action Team intern — says uncertainty from administrators leaves many students anxious.

“A lot of the reason we have to act proactively is because this is a climate of fearful uncertainty,” Grogan says. “We don't know exactly how campus administrators are going to handle these things. I feel what [students] are looking for isn't even action as much as it's just communication.”

In moments of uncertainty, Student B finds strength in the support of his peers and mentors within the Patton College of Education. He wishes other international students could find that same compassion in spaces such as International Student and Scholar Services or the Dean of Students Office.

“International offices work in a very bureaucratic way, and that's not what you need in times like these,” Student B says. “What you need is human interaction and human empathy.”

The debate over whether universities can remain politically neutral opens the door to a larger national question: when does advocacy become political? Johnson says the two should not be confused.

“In this heightened, hyper-polarized universe we're currently living in, people assume by being political they have to take a stance on a political candidate or party, or they have to come out and be anti-Trump,” Johnson says. “Taking a stance on people's right to just exist [and] have their constitutional rights to due process on U.S. soil [is] not a political thing. That's just an integrity thing.”

Today, Student B says he finds hope and support within the local community. Each week, he attends lunches hosted by the Athens First United Methodist Church on College Street. These gatherings provide a space, Student B says he finds deeply grounding.

“[At the lunches] I run into a lot of community folks who I talk to, and that is where I see a lot of hope,” Student B says. “In those human interactions and the ability of human beings to have meaningful conversations, regardless of their differences.” b

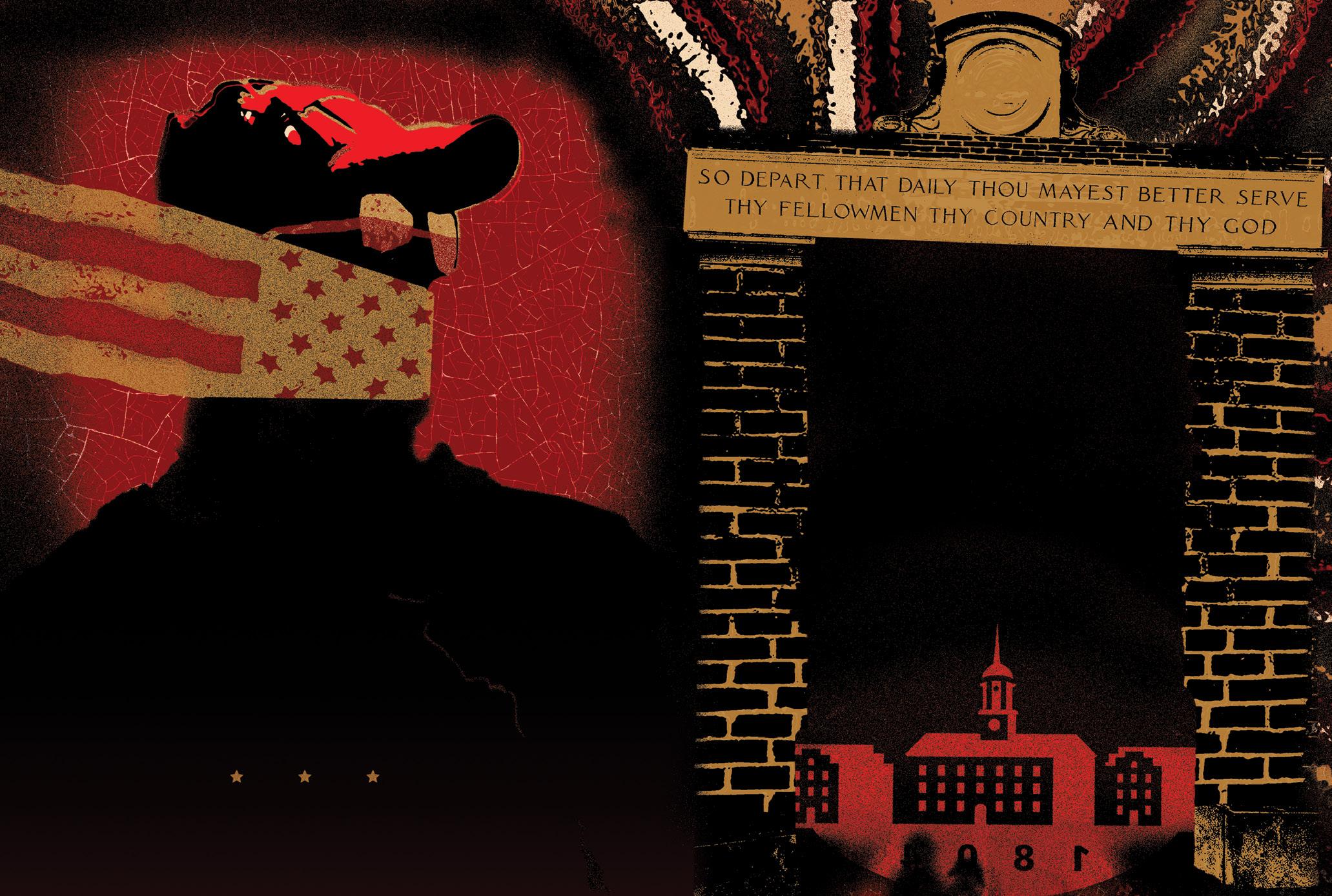

BY LIAM SYRVALIN | DESIGN BY TOBY SUTHERLAND

The 50th anniversary of the end of the brutal Vietnam War – known in Vietnam, incidentally, as the “American War” – passed April 30, just a few months ago, without much recognition or fanfare here in the U.S.

The destruction American forces inflicted on the Vietnamese people during the 20-year conflict is difficult to describe. 4 million tons of bombs were dropped on Vietnamese villages, towns and cities.

That is to say, American-led aerial bombardments alone in Vietnam more than doubled the amount of bombs dropped by the U.S. in the entirety of World War II, a conflict that transcended all national boundaries. The figure does not even include the 400,000 tons of napalm dropped, nor the 19 million gallons of herbicide unloaded from the sky, both of which are still affecting birth defects and abnormalities in Vietnam today.

With all this said, the passing of the anniversary will likely not include any fanfare or remembrance for American antiwar soldiers and deserters. Yet, they were a crucial force in bringing the devastation to an end, reinvigorating our moral conscience and are perhaps the most beautiful example of American democratic expression.

We must engage with the histories and memories of those folks in good faith and attempt to understand their story.

There’s one clear window from the era, one that doesn’t nearly get the attention it deserves: the Underground GI press movement.

The Underground GI press was a decentralized network of anti-war newspapers that were written by GIs, veterans and activists and mostly circulated around domestic bases and U.S. bases in South Vietnam. One of the most well-known publications at the time was Up Against the Bulkhead, printed in the San Francisco Bay Area. Letters from soldiers at the frontlines in Southeast Asia were sent to, and printed in, the publication in droves.

For instance, one Marine Corps GI who took the pseudonym “Fat Al” had his letter printed in Up Against the Bulkhead’s December 1970 issue. He opened his letter despairing he “had been trained to believe, conditioned really, that killing another human being for this country is a good and honorable thing.”

He expressed outrage, in “our ‘democratic’ government can force individuals to be converted into machines of destruction.” He also shared that at the time of writing, he had been in a military prison for “refusing to actively support the military machine of a fascist government.”

Another letter, incidentally from the same issue, came from an Air Force GI, Joel Gaalswak, and covered his personal reflections on his daily work in Vietnam.

“The nature of our defense establishment makes it easy, especially for Air Force members, to make an abstraction out of the death-dealing of warfare ... I refuse to make abstractions out of the actions of war. The result of the use of armed forces is death.” He closed the note by defiantly stating, “We are those who quietly go out of our minds after the day’s mission, as our companions discuss the enemy ‘body count’ over a beer, back at the club.”

The photos and visuals used in the publications are also worth discussing; for one, they often showed extremely graphic yet crucial scenes of the consequences of armed violence. For instance, the cover image of the issue of Up Against the Bulkhead shows an American soldier in a wheelchair with both of his legs amputated. He is positioned under a poster that reads “Ask a Marine,” while the wheelchair-bound soldier cheekily smiles and gives the middle finger to the camera.

Another short-lived publication in the movement, printing out of Los Angeles, Left Face, printed a full-page photo on the cover of their fifth issue with the caption, “God Bless America.” The picture showed an American soldier with his knife inches deep in a Vietnamese person’s stomach. The victim’s left arm is severed off, suggesting the Americans are dismembering and disposing of the body, a war crime by the standards of international humanitarian law.

One entry in the July 1971 issue of Helping Hand contained a poem that would later become one of the most immortal cultural icons of the anti-war GIs. The poem, later arranged and put to folk music, is morbidly titled “Napalm Sticks to Kids.” The description notes the poem “expressed [the writers’] bitterness about the things they had done and toward the military that made them murderers.”

According to Helping Hand, “each verse of the poem depicts an actual event that at least one of the men participated in.”

“Flying low and looking mean, See that family by the stream, Drop some nape’ and hear ‘em scream, Napalm sticks to kids.

“Blues out on a road recon, See some children with their mom, What the hell, let’s drop the bomb, Napalm sticks to kids.”

Napalm, the indiscriminately destructive and hellish weapon developed by Dow Chemical, was used in truly unprecedented amounts upon villages where U.S. forces “suspected” were hiding, or were at least sympathetic to, Viet Cong troops. Demonstrations across the country, including in Athens, were held to protest the use of napalm.

As early as 1967, the Athens Committee to End the War in Vietnam printed leaflets denouncing Dow Chemical as “a symbol of the complicity of the American economic system” in waging war against Hanoi. “The committee is taking this opportunity to make the Ohio University and Athens, Ohio communities aware of the atrocities the government commits in the name of American citizens,” the note stated.

The collection of excerpts is the tip of the iceberg. Since

the publications were usually meant for the rank-and-file of the U.S. Armed Forces, there are minimal censors in place, if any, and they are free from the editorial control of mass media organizations.

There is much cultural significance placed in the conflict, but even so, the perspective of humanist, pacifist GIs is given insufficient thought. The Underground GI press is the immortal window through which, 50 years later, our society can finally re-evaluate our understanding of the Vietnam War for the better.

To truly come to terms with our decades-long conflict in Vietnam, we must salute these brave individuals with patriotic dedication and reappraise their efforts in ending the brutal destruction sown upon the country of Vietnam.

We must praise the legacies and contributions of the rank and file resister, folks like Gerald Gioglio. Gioglio, a veteran and anti-Vietnam War activist, recounted in his book Marching to a Silent Tune, which says, “asking someone what they did in the war comes with the unstated but assumed expectation of stories of courage and bravery under unimaginable conditions ... But what we tend to fail to anticipate is many veterans, especially from the Vietnam War era, also have extraordinary peace stories to share, which are all too often dismissed as neither courageous nor brave.” b

BY LILIA SANTERAMO | DESIGN BY SONNY JAY

The U.S. is experiencing an intense moment of social disconnect and weakened community. Many readers may recall the previous U.S. Surgeon General, Vivek Murthy, declaring an “Epidemic of Loneliness” in 2023. It is easy, perhaps, to attribute this declaration to the COVID-19 pandemic, and leave it at that, but research shows the U.S. has been moving in a direction of social isolation, alienation and individualism for decades.

In an article for The Atlantic called The Anti-Social Century, Derek Thompson writes that since the 1970s, the U.S. government has shifted focus away from promoting public infrastructure and programs. The shift in priorities coincides with Americans gaining more time to spend outside of work. As social spaces disappeared, television proliferated, leading Americans to choose to spend their leisure time alone at home, watching TV.

Currently, Americans continue to spend a significant amount of time at home, but television has largely been replaced by cell phones, which make it easier than ever to not go out. Thompson notes Americans today can work, shop, be entertained and socialize at home, giving them little incentive to leave. Yet, Americans are so lonely that the previous Surgeon General declared it an epidemic, thus

indicating that the “socializing” done at home is not effective.

The illusion of social connectedness provided by social media (which seems, with the few in-person options provided to Americans, like a good way to find companionship) has likely exacerbated the years-long trend of social isolation.

From 2003 to 2019, people aged 15 to 24 went from spending an average of over 150 minutes to less than 50 minutes with their friends per day, according to a 2023 study published in the Social Sciences & MedicinePopulation Health journal. Consider this in tandem with the average screen time of teenagers. A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that over 50 percent of teenagers have four or more hours of screen time a day, much more than they spend with their friends. Social media is likely the primary form through which young people conduct their social lives.

But while social media undeniably has the capacity to foster some connection, it does not replace humanto-human interaction. We do not reap the same physiological or psychological benefits when we interact with people through a screen as we do when we interact with them in person.

Furthermore, we struggle to depict ourselves as fully realized, complex or flawed people online, where we

are always cultivating an image and a persona in a way we cannot in person, simply by the nature of the fact that online, we can control, edit and revoke presentations of ourselves. There is no vulnerability in this, and therefore little capacity for intimacy to be reached in an online setting.

In 2024, the Survey Center of American Life published various findings on the state of modern-day social connectedness as it relates to access to public spaces. The survey found that 21 percent of Americans live in communities with no access to commercial and public spaces to socialize. 36 percent have minimal access (1-3 spaces), and 26 percent have moderate access (4-7). Just 18 percent of Americans have extensive access (7-10).

Americans with less access to community spaces were more likely to report having fewer friends. Additionally, 50 percent of Americans reported “seldom” or “never” talking to someone in their community they did not know well.

In general, Americans participate very little in their communities. The authors of the study state in their findings that fewer than 20 percent of Americans belong to hobby groups, neighborhood associations, sports leagues, parent groups, or youth organizations. Very few Americans report volunteering (28 percent) or

attending a community meeting (33 percent) even a few times a year.

Social media is not to blame for this. When it is used as not only a legitimate form but also the primary method for socializing, one cannot expect a meaningful push for changes that would provide Americans with better social connectivity. It is important, then, to closely examine the role social media plays in our social lives, one that leaves us struggling to fully participate in them.

In her book On Photography, Susan Sontag described photographs as “coveted substitutes for firsthand experience.” Sontag also said photography “offers in one easy, habitforming activity, both participation and alienation in our own lives and those of others — allowing us to participate, while confirming alienation.”

Photography, or image-based social media posts, makes us feel as if we are experiencing the thing being depicted, despite this being far from the truth. This is why we stay at home, rather than pursuing these experiences.

Out in the world, we have adopted a bad habit of documenting everything we do, rather than being present in these moments. And to what end? Does posting a quip or gripe online allow people to be heard by others? Can a picture of someone’s daily life provide insight into who they

might really be? Even a post on one’s private story or account has a degree of impersonality, because all posts on social media are directed at no one in particular, and are generally unlikely to elicit a meaningful response.

And yet, this writer has observed that we often feel closer to others if we follow them on social media, as if it is an important signifier of a stage being reached in a friendship, or a means for us to cultivate intimacy and experience one another’s lives.

We have, in short, become voyeurs rather than participants of our own lives and the lives of others, and we are mistaken in believing that access to the sanitized mundanities being presented to us through a third party brings us closer to the person using it as a medium for communication.

It is worth remembering that social media is first and foremost a money-making endeavor. When we use social media as our primary form of interaction, we are allowing businesses to dictate the conditions of our social lives, which will always ring hollow because socializing under these conditions requires turning ourselves and others into commodities.

This is also observed in social media’s newfound role in driving culture. This culture is not one of authentic connections or nuanced exchanges of ideas or creativity. Instead, it

is based on algorithms designed to promote more of the same, rather than something new, and only things that will sell. A culture based on oversimplification for the sake of commodification does not translate well into our lives offline, leaving it largely meaningless under real-life conditions of complexity.

So why do we regard social media as helpful in our quest to connect with one another? Our current moment is informed by a collective attempt to navigate our social context, which is one largely centered around ourselves rather than the larger world. Social media fits well into this context because it reaffirms it while claiming to do the opposite, creating a false sense of connectedness while keeping us comfortably situated within the status quo.

A possible first step in reversing the hyper-individualist and disconnected moment we are experiencing is recognizing that social media does not truly cultivate intimacy or strong communities. From there, the task of deemphasizing social media as a point of contact and reemphasizing civic engagement is necessary to bring about change. It can be as simple as saying hello to a neighbor or as complex as advocacy, but regardless, there is a path forward if we choose to pursue it. b

America has a purity obsession. The obsession has become glaringly obvious with the uptick in conservatism fostered by the Trump administration. Many associate purity culture with the politics of a distant past, but it remains present in our culture in ways that are somewhat subliminal and undetectable.

The rise in conservatism specifically values clean, sterile tradition. The tradition is white supremacy. To mold a culture into one that values “purity,” be it in bodies, minds, spirituality or race, forces bodies to conform to what the power structure deems “normative.” And in America, the white, male body is what is seen as most pure and normal.

In 1863, Édouard Manet painted “Olympia.” The oil piece depicts a young, white prostitute reclining with an air of authority while her Black maid bears flowers. Manet took inspiration from Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” but reconstructed it to portray Olympia’s sexuality and the racial hierarchies rooted in perceptions of purity.

Olympia’s white skin stands out starkly against her maid’s deep umber complexion, making her an object of desire, marked as docile and pure, while the maid marks her as less than, presenting her as an object of obedience, not desire.

Her presence elevates Olympia’s position, but standing next to Olympia only emphasizes her marginality. The white woman is an idol of lust.

On the other hand, the Black woman’s skin color is a tarnish upon her existence, forcing her out of the frame. She is forever framed as inferior based solely upon the perceived impurity of her race.

We are not beyond this history. It is easy to see ourselves outside of the scope of historical human chronology, and easier yet to ignore the patterns we repeat with each generation. The myth of how far we’ve come blinds us to our

WRITING & DESIGN BY ZOE DUNCAN

conditioning. We still find ourselves surprised to be perpetuating the myth of purity — sexual, racial, moral or otherwise. To understand why we find ourselves repeating history, we must look back for explanations on the roots of our cyclical nature.

From the genesis of Western civilization, we as humans have identified ourselves through a lens of difference. Various social mechanisms were developed to distinguish ourselves from others, in an attempt to uphold order.

Women, for instance, were thought to be deformed men, plagued by menstruation and their wrongness, making them deserving of subservience. As modern nations formed and Europeans found a need to differentiate themselves, binary ways of thinking about race developed. Purity culture became one way in which the normative “us” is made subject against the othered “them.”

By measuring difference through a lens of normal and pure against abnormal and polluted, purity culture establishes a source of difference to oppress the other. Early modern Europeans viewed themselves as pure and others as contaminated. Those within European society who exhibited impurities such as racial difference and non-Christian spiritualities were thus put down by overlapping oppressions.

Disgust, according to Sara Ahmed in The Cultural Politics of Emotion, “shows us how the boundaries that allow the distinction between subjects and objects are undone in the moment of their making.”

Purity culture upholds that boundary, creating a line between what is pure and what is polluting. In the case of American culture, sex, race and class are all vehicles through which purity is

disrupted. The subject becomes firmly rooted in the portrait of the straight, wealthy, white man, while the object, the contaminated other, is all that is not.

White purity is framed as something to strive for, and all that deviates is impure and wrong. These impure characteristics are ingrained with shame, a powerful force in keeping certain bodies marginal.

Purity culture bleeds from the foundations of America. White settlers arrived and massacred Indigenous people who were othered by their brown skin and “uncivilized” ways. European powers brought enslaved Africans to toil in their fields while their pristine colonnaded homes sat bright and pure against a landscape of bloodied bodies.

The constructed impurity is what made the enslavement permissible in the eyes of the landed elite. Later, when emancipation swept the nation, Jim Crow legislation measured purity in the blood of the people who built the nation — just one drop of brown or Black blood not only made a body impure, but socially wrong.

The wave of progressivism came and went. Many Americans saw the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War as a tarnish upon the nation. Nonetheless, purity politics still found its way into mainstream society.

McCarthyism weaponized fear to root out society’s communist pollutants. Here, the white and heterosexual nuclear family was raised as the pinnacle of American normalcy, but impossible for some to attain.

What we are seeing now is the product of our collective American social values being raised, torn down, reconfigured and raised again. The influx of conservatism mirrors the Ronald Reagan era of the 1980s. America’s society of the Reagan era treated the AIDS/HIV epidemic as an act of God, an eradication of America's social “contaminants” — the impoverished and disproportionately vulnerable communities, such as homosexual men, addicts and prostitutes. Now, it’s being forced on us through different means.

While these same groups and more are targeted today as wrong, contaminating, gross and dirty, we are simultaneously being sold messaging that opposes individualism and is coded with white supremacist meanings.

TikTok’s “clean girl aesthetic” is one such way that individual expression is discouraged. To associate cleanliness with makeup-free skin, perfect slickedback blonde hair, simple jewelry and simpler outfits creates an implicit correlation between cleanliness and rightness.

It becomes trendy to be clean, free of any indication of deviancy. Queer and Black fashion are devalued or modified to be palatable to a normative consumer base. The efforts in banning drag queens from public spaces, most notably children’s library hours, once more speak to the American fear of pollution.

Purity is a weighted word. It brings to mind the Right Evangelical craze of the late 20th century, with women’s sexuality becoming heavy with stigma and shame. It evokes eugenics movements that label disabled and non-white bodies as pollutants to be disregarded.

Ultimately, purity itself is a myth. There is no one right way to be, and striving towards an idol of purity will only achieve the eradication of difference and the erasure of the diversity that gifts America its cultural complexity.

White purity and conformity won’t make America great; it is only a mirage through which fascism will seep into the cracks. Diversity, difference and expression are what can make America achieve greatness, so long as we strive to persist in recognizing and rejecting the tools of white supremacy. b

Olympia, Édouard Manet, 1863.

While in the past, OU has been known for its party scene, students now question whether the culture has shifted

BY PARKER JENDRYSIK | PHOTOS BY CLAIRA TOKARZ | DESIGN BY ELLIE SABATINO

Ohio University is undeniably rich in party scenes. Whether it’s during weekend festivities or athletic events, OU is plentiful in its offerings. Bars? You got it. Trivia? Absolutely. Fraternity parties? Yep. Live music? Always. And so much more.

OU was ranked the 13th best party school in the U.S. in the Princeton Review’s Top Party Schools for 2015, and the number one party school by Playboy magazine the same year. However, OU has been speculated to be on the decline as one of the best college party schools. Bobcats can attest to this theory.

Dan Gordillo, a senior studying linguistics and political science, says he knew he wanted to be a Bobcat when he visited OU during Mill Fest in 2021. At first, college was never on the agenda. “I hated the idea of going to college,” Gordillo says. “And all that changed when I came down here.”

That year, Mill Fest aligned with the day OU played a game in the March Madness tournament. “That was coincidentally the time when OU had their upset No. 13 OU against No. 3, Virginia, in the NCAA March Madness tournament,” Gordillo explained.

“We were not supposed to win that game. And we did,” Gordillo says. “I was in the middle of Court Street watching the party that happened. It was spontaneous. Court Street went from a ghost town to literally full, but it was the largest in my entire life. At that moment, I knew that I had to come here.”

Gordillo emphasized that it wasn’t just the social atmosphere that influenced his decision to become a Bobcat, it was the unique culture of OU that truly set it apart from any other college in the state.

OU’s party ranking at the time of Gordillo’s visit sat at No. 12 by Newsweek. However, that rank has been steadily declining ever since. Iconic events like Palmer Fest being restricted have potentially played a role in this decline in ranking.

“We have a party reputation,” Gordillo says, “and we need to work to maintain it.”

However, with every responsible party scene comes the protection of its inhabitants: the students. While also advocating for a higher ranking on the OU party scale, Gordillo also serves as the President of the Student Senate.

Representing more than 30,000 undergraduate students, Gordillo advocates and represents the student body. Gordillo is a two-time elected president for the Student Senate, which is an event that has not happened in decades. He prides himself on being a voice for the diverse student body in Athens. Each year, the student senate helps fund over 600 student organizations and hosts events such as Pride Week, Finals Fest and Take Back the Night. And with OU’s strong party reputation, Gordillo is responsible for advocating for safety protocols for students who participate in such festivities.

“The biggest thing that we like to do is we help out others. A subsidiary of the student senate is called Students Defending Students. Students defending students before major OU holiday weekends will distribute information, just some basic advice about how to not get in trouble. And we do our best to really promote that,” Gordillo says.

“At the end of the day, let’s also just prioritize safety, prioritize making the right choice. Drinking is not necessarily the wrong choice. Enjoy responsibly. That’s something that almost every alcohol company says. Let’s teach this responsibility. Let’s remind folks that we’re here to make memories, not forget them,” Gordillo explains.

“I believe students see it as part of their identity. I think that’s very valid. As a linguistics major, you can actually notice it,” Gordillo explained. “I once did an in-class project on the local English dialect in Athens. For instance, if I say, ‘I’m going to Court,’ here in Athens, that phrase carries a completely different meaning than if I said it in Cleveland. The word ‘court’ takes on two entirely different connotations depending on where you are.”

OU has been actively attempting to lessen the party reputation that Bobcats hold dear to their hearts. In the minutes of the Board of Trustees’ meeting in 2009, members stated, “A reputation-building campaign measurably increased awareness of the University, improved its reputation for academic excellence, and diminished the image of the University as a party school.”

oh. 2025

But, at OU, parties aren’t the only iconic traditions rumored to be losing their reputation — Court Street’s legendary status is also being called into question.

Alexis Dorr graduated from OU in 2018 with a bachelor’s degree in health administration. As a student, Dorr worked at Stephen’s on Court, highlighting nightlife as a way to have fun but also learn the strength that the OU community has, no matter the setting.

“Summer of junior year, going into senior year, I started working at Stephen’s as a bartender for happy hour. And that was the summer I stayed at OU. That was my favorite time of my life,” says Dorr. “It is the best. So, you know, we would have pool parties, and you’d work for five hours, and then hang out with your friends and go out.”

When it comes to OU's changing party reputation, Dorr says things have become noticeably more tame since her time as a student. “There were a lot of things we could get away with before,” she says. “There just seemed to be fewer rules.”

She recalls the weekends when Athens nightlife was at its peak. The bars, she says, were “packed to the brim” during her undergraduate years. “They would have lines wrapped around the entire block, like, trying to get into J Bar,” says Dorr.

“I just feel like it was maybe a little bit different then. There were way more people in the bars. When I went the past couple of times, they were way more strict on the code of the maximum number of people that could be in the bars, and when I would be there, you literally could be on top of each other. I have so many videos on my phone of being in J Bar, and then them turning all the lights on. Firefighters would come in, and they’d be like, ‘All right, 100 people need to go.’ They wouldn’t play music until literally 100 people walked out of the bar because it was so crammed,” Dorr says.

Now, she notes, things seem far more regulated. The bars, once chaotic and overflowing, appear to have traded some of that energy for order.

With Bobcats scattered everywhere around the world, one thing will always remain the same: they help each other and they know how to have a good time.

“I feel like that community that you build, even at school, still carries on through life. I have some great co-workers that are like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re a Bobcat, I’m gonna help a Bobcat.’ And now we are good friends, because it’s like, well, I know [where] you went to college,” explains Dorr.

The party life at OU will always play an integral role in the culture of Athens, Ohio. The parties may change and the years may pass, but the laughter, friendships and memories woven into this small town will live on forever. b

party

Raising Cane’s arrival tests Athens’ appetite for national brands and its loyalty to homegrown favorites

BY KENDAL AKERS | DESIGN BY JULIA PARENTE

Tucked away in the Appalachian Mountains, Athens is known for its small-town charm and vibrant food scene. Until recently, the town’s fried chicken lineup consisted of four main spots: Miller’s Chicken, Hot Box Chicken Fingers & Tots, Wings Over and Kentucky Fried Chicken. A new competitor joined the flock Oct. 8, 2025, when Raising Cane’s Chicken Fingers opened its doors on Court Street. With the establishment of another competitor to Athens’ crowded chicken market, a familiar debate has reignited over how local businesses can coexist with national chains.

On Court Street, Cane’s and Hot Box now stand as the two primary contenders, both offering small, focused menus centered on chicken tenders and fries. Wings Over, another uptown staple, specializes in wings but offers tenders as a

secondary option. Miller’s Chicken and KFC also serve fried chicken but operate outside the Court Street area, making them less accessible to students. Of the five, only Miller’s and Hot Box are locally owned.

Miller's has been serving the Athens community since the 1940s and remains a local favorite known for its quality and strong connection to the surrounding community.

Andie Walla, a media arts and studies professor, has lived in Athens for over 20 years. “I'm willing to bet that most college students who rave about the new big box store uptown have never been to Miller's or know it even exists,” says Walla. While Miller’s location on West State Street may be less convenient for students, its reputation encourages exploration beyond the main uptown strip.

Hot Box entered the scene in 2024 and, similar to Miller’s,

operates with a mission to support the Athens community. A portion of Hot Box’s profits goes toward the Athens County Scholarship by Hot Box Chicken Fingers & Tots. When Cane’s opened its doors, some residents worried the national chain would threaten smaller, communityfocused establishments.

government shutdown in November halted Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, also known as SNAP, Hot Box began to provide free meals to Athens County recipients, funded through local donations.

“I feel like people are going to be more drawn to Cane’s because it's more well-known and more comforting, and it's just a great comfort food,” says Victoria Glinsky, an engineering technology management student at Ohio University. “I feel like it's going to get a lot of business, especially because it's right in a great location,” she says.

Cane’s did not come quietly to Court Street, as the restaurant's arrival was accompanied by a grand opening and a line of customers stretched down Union Street. With the promise that customers in line had a chance to win free Cane’s for a year, many students waited in line starting at 1 a.m.

The morning of the opening, Cane’s employees emerged from the restaurant bearing merchandise to distribute to those waiting in line. OU's drumline and cheer squad came out to perform. Inside, the restaurant reflects OU’s school pride, decorated in green and white with a mural of the Marching 110.

“Rain or shine, it’s chicken time,” says restaurant leader Zachary Quinn, who greeted customers despite the rainy weather. The Cane’s crew also presented a $1,000 check to Passion Works Studio, an Athens nonprofit.

However, the restaurant’s establishment was not without complications. Cane’s opened in the Lostro building, a development that led to the closure of Cool Digs Rock Shop and Grub-N-Go, two small businesses, after construction blocked pedestrian access to their storefronts. In response, the Athens community rallied together, protesting the construction last March to show their support for the displaced shops.

There are over 900 Cane’s restaurants across the United States, but before October, there were zero in Southeast Ohio. The placement of the Cane’s was strategic, positioned just steps from Alumni Gateway to attract students. The company has a history of engaging with college towns; its partnerships with Ohio State University, including scholarship programs and athletic sponsorships, have built a strong brand presence in Columbus.

Hot Box also offers scholarships to Athens High School students, but competing with the scale of a national chain remains a challenge. Even so, owner Kevin McNamara has maintained a focus on community support. When the federal

Over the course of four days after their initial announcement, Hot Box provided “nearly $4,000 in meals to the people of Athens County who are without SNAP assistance,” according to a post on their Instagram page.

Hot Box “will continue doing this until the government has funded SNAP accounts, giving people the dignity to feed themselves and their families,” according to that post.

Some students believe Athens’ restaurant scene is large enough to sustain both local and national establishments.

“I think Cane’s will be a good addition to the chicken scene, but I don’t think it’s going to take over,” says Emillee Flagg, an OU student studying engineering technology management. “Miller’s has really been here forever, and I think there will still be room for everyone.”

“I don’t think I will necessarily prefer Cane’s over Hot Box because I do really support the local business style that Athens has,” says Ben Jarrell, an electrical engineering student at OU.

Others are less optimistic.

“I think that I would be shocked if it didn't lead to some closures. We saw it before with Oryza coming in and leaving after a year; one can only speculate it was because of the sheer amount of Asian food places around here,” says Jay Cline, a fourth-year film student. Oryza was in Athens for two years before it closed its doors last April.

Oryza Asian Grill, which closed last April after two years in Athens, struggled to compete with the 10 established Asian restaurants already serving similar cuisine, some just a few doors away. The closure raised questions about whether Athens’ tight market can support additional restaurants in already crowded categories.

Still, local examples suggest coexistence is possible.

“There are many coffee places in town, and a Starbucks doesn’t seem to have meaningfully harmed the business of any of them,” says Max Ries, a third-year English student. “I assume this chicken situation will be similar.”

For now, Athens’ food scene continues to balance small-town identity with the inevitability of change. The arrival of another national chain brings convenience and name recognition, but also challenges the community’s commitment to supporting local businesses. As students and residents choose where to eat, they also decide what kind of Athens they want to sustain. b

BY LUCY RILEY | DESIGN BY LILLY COCHRAN

That’s not cake, that’s water,” I responded, completely deadpanned to my 4-year-old cousin. He looked at me with a look of surprise only adults have, that shocked look with a hint of strange amusement. “What the hell is wrong with me?” I thought to myself. He’s a little kid, pretending his cup of water is cake, what’s wrong with that? An active imagination never hurt anyone. Had I really forgotten how to talk to kids or anyone?

Finally, I could stand for more than a few seconds; the 8.5-hour plane ride I booked from London, after spending seven hours in London Heathrow Airport, had landed. Almost immediately, I was hit with a wave of familiar humidity I had forgotten about. The night before, I’d worn my leather jacket and jeans; now I felt like drinking water out of a hose and stripping down to my socks. The excitement of seeing my family and friends was the only thing keeping me from strapping myself to the plane and begging them to go back to Germany.

Not three days ago, I was catching trams and meeting my friends without a phone that fully worked, spending hours on end in immigration services, opening my fifth health insurance and second bank account the university would accept, learning the different characters' names in French SpongeBob — or “Bob l’Eponge.” Now I need to remember staring is rude, I can’t wear the same clothes I used to and the people I’d grown to love were thousands of miles away and 5 to 7 hours ahead. The hum of different languages I’d grown used to over the past six months was gone. Everything sounded sharper, louder — English ricocheting off walls, announcements in an accent I should have found comforting but instead felt jarring. Even a simple, “Hi honey, how are you?”

from a kind older woman felt strange to hear.

That was the first moment I realized: coming home might be harder than leaving.

When I first arrived in Leipzig, I expected to feel disoriented. I prepared for the sting of not knowing, for the awkwardness of fumbling through conversations, for the discomfort of unfamiliar traditions.

And yes, those moments were all there — staying in a six-bed hostel room for a month, navigating public transportation in new cities, walking two hours with all my belongings and my heavy suitcase bumping repetitively, giving me bruises and scraping my calves. But I did not feel “shocked” so much as I felt propelled; I had no choice but to adapt quickly. The city around me was forcing me to. I did not have the time or space to really process the differences.

Being back in the U.S., though, I did. I wasn’t pushed day-to-day by myself in a new country anymore; I was supposed to be comfortable again. I started to wonder if reverse culture shock was more intense than its original. You expect to feel like yourself again. And when you don’t, the dissonance is sharper. The first few weeks back, I had a struggle of keeping down food that made me feel nauseous and bloated beyond being uncomfortable and remembering how I used to act around those I love.

Now, I can recognize this can sound like a bit of a spoiled sob story, “Aw, baby has to go to Europe and it's so hard to come back.” But it’s a different feeling, it’s not a feeling of sadness or a longing to go back, it's more of a feeling of discomfort and disorientation. It’s a feeling of frustration that I can never fully articulate my experiences. I can talk about how funny it is that my friend Guillaume wants to come to Akron to see Lebron, or the time my roommate Casey and I booked a trip to Croatia in 30 minutes and stayed up until our bus to the airport at 2 a.m. or the time I stayed in that six-bed hostel for a month and by some odds met one of my best friends, Hugo. I can never fully encapsulate the beautiful buildings and churches I saw, the cities I visited, the friends I met or the experiences we shared. How do you explain major life experiences that no one else witnessed?

The idea of reverse culture shock isn’t something new; it lingers in small, unexpected moments. Plenty of people who leave the country for an extended period of time on their own experience some form of difficulties readjusting to life in their home country. Oftentimes, the longevity of one's stay makes the readjustment that much harder. Particularly when a person has gone alone, they often create a sort of hard shell mentally, protecting themselves from the unknown and providing a sense of self-protection.

The U.S. Department of State has a healthy-sized section covering culture and reverse culture shock. It illustrates this dilemma in a graphic of a rollercoaster called “The Reverse Culture Shock W-Curve.”

Starting at the beginning of assimilating to a new place as a smaller lift hill (honeymoon) and a small drop (crisis), followed by a larger lift (adjustment) with a rather large peak marking (honeymoon), the return to home

is followed by a much larger drop in the coaster (crisis at home).

The “W-Curve” makes sense: there are constant climbs and dips, feelings of excitement and of disorientation. However, what it can’t show is just how quietly it can all happen. It can’t depict how it sneaks up on you in silly, insignificant ways, like grocery shopping or in conversations, reminding yourself of the subtle differences in humor and conversational cues across seas.

I have come to understand that the comfort I feel is only a fraction of what many others may feel. I am lucky to have experienced such a beautiful journey, and although there are moments of being uncomfortable, just how lucky I am to have that discomfort and how lucky I am to have the ability to come back. Maybe the point of this feeling of discomfort isn’t that you are meant to fit perfectly back into place; growth is, after all, moving ever forward. b