Exploration of Waiting Spaces: Emotional Regulation Through Use of Playful Intervention

Exploration of Waiting Spaces: Emotional Regulation Through Use of Playful Intervention

Sophie Lee – 200418890

ARC3060 – Project Dissertation

Playful Cities - Alkistis Pitsikali

Newcastle University 23/24

Architecture, Planning & Landscape

5633 Words

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my dissertation tutor, Alkistis Pitsikali, for her unwavering support and guidance throughout this project. I must also thank the workshop technicians, Richard Chippington, Nathan Hudson, and Sean Mallen for their dedicated encouragement and instruction throughout the construction phase. Thank you to module leader, Toby Blackman, and Stage 2 module leader, Rosie Parnell for their comprehensive teachings. A huge thank you to Dr Andrew Langley for his incredible insight and guidance. I could not have done this without the support of Koda, my dog. My mother helped too. Special thanks to Benjamin Gath for being an incredible aid during this time.

This project is dedicated to my dad, Geoffrey Lee, who just really loved sitting down.

‘Architecture can accommodate the condition of queuing by spatially translating the factors that make it a positive experience, ultimately increasing human psychology and curing the city of toxic waiting spaces ’ 1

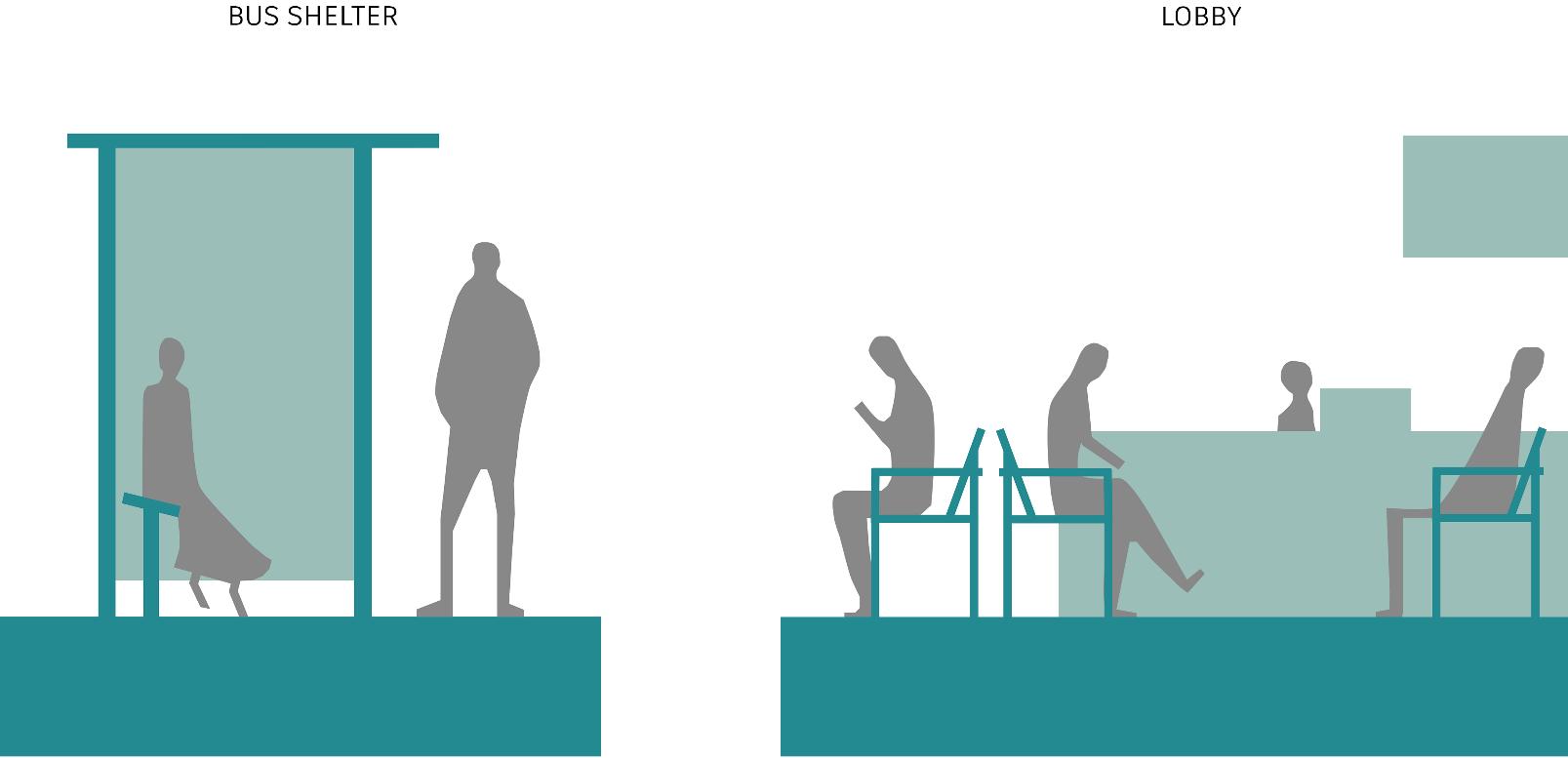

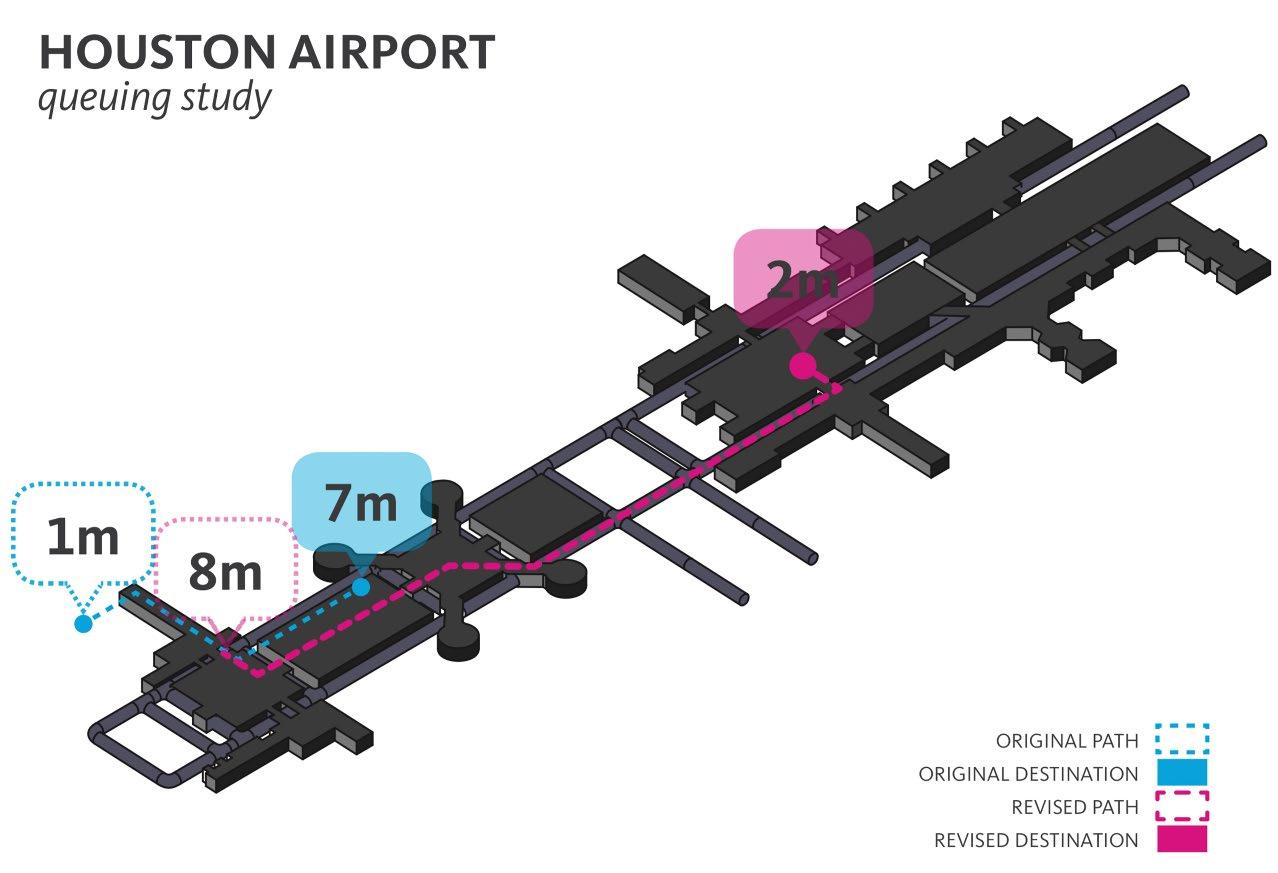

Cities are rife with various waiting spaces, considered as ‘any space that is designed for people to use to pass time while they wait for something else to happen’, including spaces such as bus shelters, train stations, and public seating areas. 2 These are connected using transitionary spaces, known as ‘spatial bodies that are experienced in motion’ 3 Negative psychological impacts have been observed in people while waiting, including stress and restlessness, which manifest in a range of typically unconscious behaviours 4 This makes it important to consider how transitionary and waiting spaces can be altered in order to provide a moment of pause in the rush of daily life Researchers have attempted to apply psychology to improve the experience, with focus on the area of pre-occupation. 5

Play in people of all ages can be considered as a form of both emotional regulation and pre-occupation, defined as a ‘behaviour or activity that is carried out withthegoalofamusementandfun’ 6 Considering these concepts, it appears as though there is a problem surrounding the negative experience of pausing and waiting with a potential solution using play as a form of distraction.

Therefore, this project will question whether play can be applied to relieve the negative psychological symptoms associated with processes of waiting in both aforementioned spaces. While this study originally explored only waiting spaces, the project research was adapted due to limitations This concerned the placement of the tool for measurement, which had to be situated in a transitionary space. To answer this question, I draw from various sources including books, articles, and websites. This process will start with the analysis of waiting and transition from one space to a destination, covering the psychological experiences involved. In response, different, existing, and potential solutions will be considered. A similar process will be used to look at play, regarding definitions and examples of playful behaviours, considering how psychology both influences and is influenced by play, setting the stage for the analysis of playful behaviour

1 Foster, D. G., ‘Waitingandthe Architecture of Pre-Occupation’, Architecture Thesis Prep, (2012) p.11

2 Natvisa, ‘WaitingAreasatInternationalAirports’ <https://www.natvisa.com/blog/waiting-areas-at-international-airports>

3 Boettger, T , ThresholdSpaces:TransitionsinArchitecture.AnalysisandDesignTools (Birkhäuser, 2014)

4 Durrande-Moreau, A , Usunier, J., ‘Time Styles and the Waiting Experience.’, Journal of Service Research , 2.2 (1999), p.174; Durrande-Moreau, A., Usunier, J., ‘Time Styles and the Waiting Experience: An Exploratory Study’, Journal of Service Research , 2.2 (1999), p.180; Janeja, M. K , Bandak, A., EthnographiesofWaiting (Bloomsbury, 2018)

5 Klingemann, H , Scheuermann, A., Laederach, K., Krueger, B., Schmutz, E., Stähli, S., and others, ‘PublicArtandPublicSpace – WaitingStressandWaitingPleasure’, Time & Society, 27.1 (2018), p.69–91

6 Van Vleet, M., Feeney, B. C., ‘YoungatHeart:APerspectiveforAdvancingResearchonPlayinAdulthood’ , SageJournals, 10.5, p.640 (2015)

Following this analytical review, I will document the project process, beginning with the analysis of existing waiting spaces and some transitionary spaces - as well as playing spaces - used to inform the development of the intervention. The intervention will be an instrument of measure in the form of a rocking bench, inspired by the common seesaw found in children’s playgrounds; this form was reached after considering various behaviours that allow for preoccupation with minimal effort for the users. The development will then begin, and once the making of the instrument is finished, this will lead to the installation. Here, the chosen site will be highlighted, compiling the results of the intervention itself after an observational study has taken place. This will include observations of the selected site, both before and during the installation placement, to determine its effect on the environment through exhibited behaviours. The findings and discussion will consider these results in conjunction with existing research, followed by concluding remarks.

2.1 - SPACES OF WAITING & TRANSITION

Transitionary spaces can be ‘spatial bodies that are experienced in motion’, which allow for the connection of other areas, such as waiting spaces. 7 Transitionary spaces can encompass pathways, entrances, corridors, and borders. A waiting space is generally considered as a ‘space that is designed for people to use to pass time while they wait for something else to happen’, including bus shelters, train stations, public seating, and food establishments. 8 The space in which the waiting occurs is generally bound by the end-goal, where the individual hoping to catch a bus would take a seat in the relevant bus shelter. This may also define the type of waiting, whether it takes the form of a queuing system or a less organised assortment. As acknowledged by Edwin Heathcote, there is a profound intersection between spaces of waiting and social areas, for example, adolescents may adopt waiting spaces as their hangout spot during nighttime. 9 These spaces often have more focus on commercialism as opposed to user comfort. Bus shelters are clad with an array of advertisements to be viewed by commuters attempting to find comfort on the angled, narrow seats provided, if any seating is provided at all. Other waiting spaces which adopt a more open environment may seem as though their placement was merely an afterthought in the landscape arrangement. Despite existing research showing the method ineffective, many seating areas opt for an array of scattered benches in the centre of a space with little viewing stimulus to occupy the user. 10 However, a growing body of research suggests that introducing playful elements in these spaces could significantly alter the dynamics and user experience

7 Boettger, T , ThresholdSpaces:TransitionsinArchitecture.AnalysisandDesignTools , 19 (Birkhäuser, 2014)

8 Natvisa, ‘WaitingAreasatInternationalAirports’ <https://www.natvisa.com/blog/waiting-areas-at-international-airports> [accessed 19 January 2024]

9 Heathcote, E , On the Street: In-Between Architecture (Heni Publishing, 2022)

10 Gehl, J., LifeBetweenBuildings:UsingPublicSpace , 224 (Island Press, 2011)

Existing studies surrounding transitionary and waiting spaces have predominately used interviews and questionnaires to gather data in environments such as supermarkets, bus stops, waiting rooms, and lobbies. 11 These methods of data collection offer a great deal of insight into the participant’s experiences but have the potential to introduce bias associated with either the interviewer or social desirability. 12 Amongst several observational studies, one specifically gauged the effects of an intervention on the perceived satisfaction of people during their wait. This focused on their experience of a waiting room both before and after an ‘observationoriented’ artistic intervention to improve the visual quality of the space. This found that the room transformation improved ‘waiting stress behaviour’. 13 Interviews were also carried out within this study, with similar findings to the observations. As a result, it appears that an observational study would be most suitable for the research in this project, so that the results are influenced as little as possible by external variables. 14

11 Durrande-Moreau, A, and Usunier, J., ‘TimeStylesandtheWaitingExperience.’, Journal of Service Research, 2.2 (1999) p.173–86; Aarts, M and others,‘EnvironmentalDeterminantsofOutdoorPlayinChildren:ALarge-Scale Cross-SectionalStudy’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39.3 (2010) p.212219

12 American Psychological Association, ‘APADictionaryofPsychology:InterviewerEffect , <https://dictionary.apa.org/interviewer-effect>

13 Klingemann, H , and others, ‘PublicArtandPublicSpace – WaitingStressandWaitingPleasure’, Time & Society, 27.1 (2018) p.69–91

14 Hess, A., Abd-Elsayed, A., ‘Observational Studies: Uses and Limitations’ , (2019)

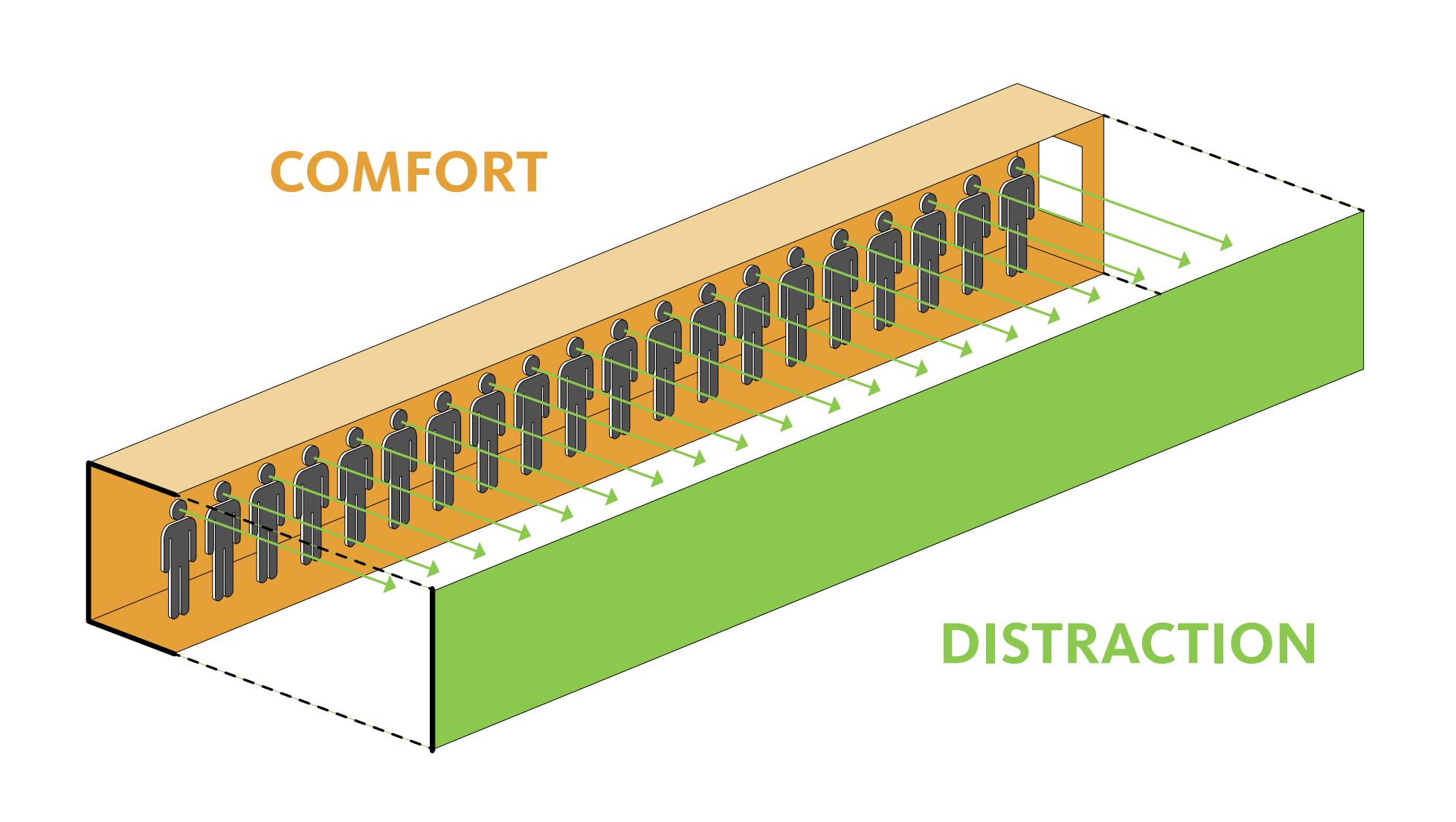

2 - An Example of the Possible Interaction Between Waiting and Transitionary Spaces

2.2 - PSYCHOLOGY OF WAITING

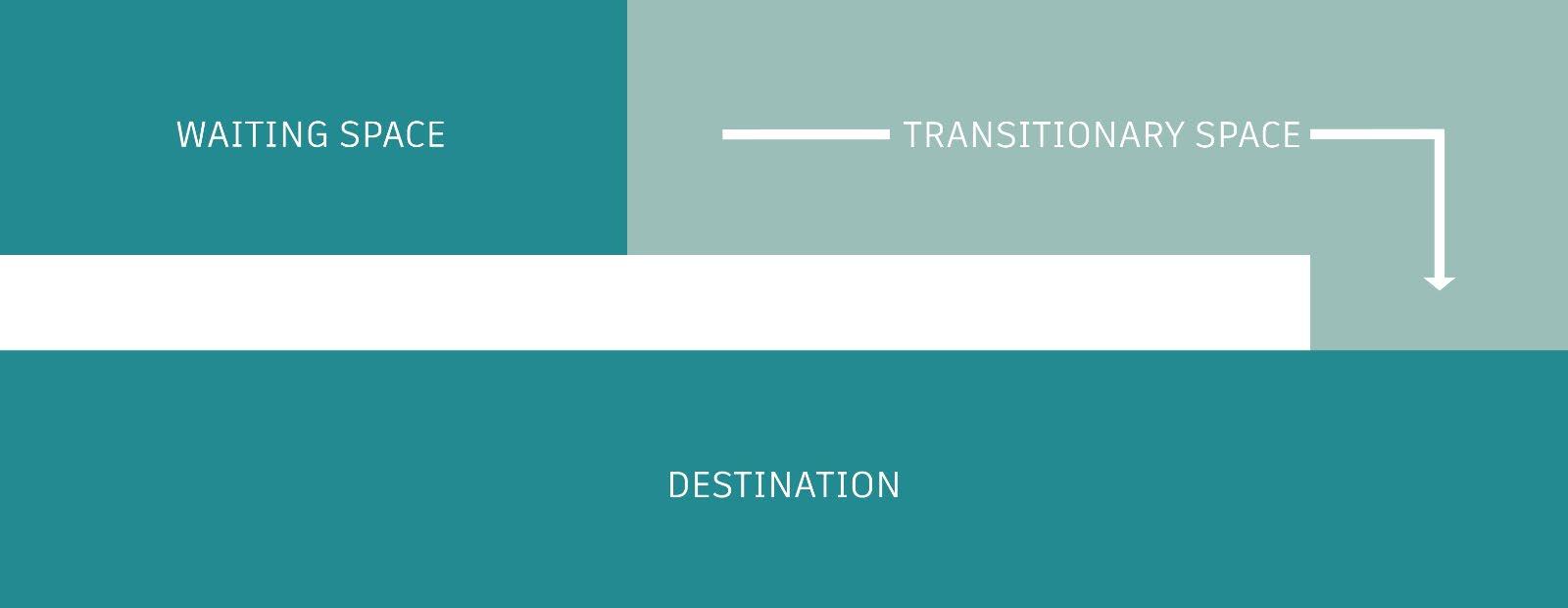

The waiting process involves a loss of time, a cost which the individual is constantly aware of. ‘This anticipation of a loss is anxiety provoking and as such can be considered as an agent for psychological stress’, which only builds the longer the wait extends. 15 The term passiveimpatience may be used to describe the instances where individuals ‘having nothing to do, drift all of their attention to the passage of time’, resulting in an over-awareness that makes time seem suspended and drawn-out 16 The proxemics of waiting dynamics have a significant impact on the level of comfort experienced by waiting individual. Proximity to other individuals may be affected by the dynamics of the waiting process within queues or crowds. It is important to consider the four levels of space shown in Figure 3: public, social, personal, and intimate space. During waiting, it is common for other individuals to intrude on another’s personal space, within a radius of 1metre This typically causes a great deal of discomfort for the person experiencing the intrusion; within queues particularly, there will often be more than 1 person intruding on this space, multiplying the level of discomfort that is experienced. 17

15 Osuna, E., E., ‘ThePsychologicalCostofWaiting’, Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 29.1(1985) p.83

16 Durrande-Moreau, A., Usunier, J., ‘TimeStylesandtheWaitingExperience.’, Journal of Service Research, 2.2 (1999) p.176

17 Foster, D. G., ‘WaitingandtheArchitectureofPre-Occupation’, Architecture Thesis Prep, (2012) p.19; p.19

Some of Maister’s observations are particularly relevant when considering the psychology behind the waiting process, including the fact that ‘occupied time feels shorter than unoccupied time’ and ‘solo waits seem longer than group waits ’ 18 Today, occupying oneself has become easier with the presence of technology, such as smartphones and portable gaming consoles, however there is still a lingering awareness of the wait in the background. Exploring the psychology of waiting reveals individuals seek engagement and distraction, which could be argued to have parallels with notions of play. Preoccupation manifests itself as both a mental and physical activity, forming a state of mind in contemplation or activities, such as reading or exercising. 19 In an urban context, it is typical to see many commuters travelling alone, waiting for transport as an individual rather than a group. 20

18 ‘Until his retirement in 2009, David Maister was widely acknowledged as one of the world’s leading authorities on the management of professional service firms (such as law, accounting, and consulting firms, and companies providing engineering, advertising and executive search services).’ Maister, D., H., ‘MyBio’ , David Maister < http://about.davidmaister.com/bio/> (2023); Maister, D., H , ‘ThePsychologyofWaitingLines’, (2005)

19 Foster, D. G., ‘WaitingandtheArchitectureof Pre-Occupation’, Architecture Thesis Prep, (2012) p.24

20 Department for Transport, ‘AnnualBusStatistics:England2020/21’ (2021)

Interviews and questionnaires form a large portion of studies investigating the experience of waiting, primarily conducted as part of a field study in a natural environment. 21 Surveys have also been completed in this setting, using the Spielberger state anxiety inventory to determine their levels of stress while waiting. 22 Considering existing research, it would appear as though interviews allow for a deeper level of insight into the experience of participants, but this may affect the presence of behaviours which hope to be recorded, whereas an observational study should have minimal impact on this factor.

21 Chang, P , Qian, X , Yarnal, C , ‘UsingPlayfulnesstoCopewithPsychologicalStress:TakingintoAccountBothPositiveandNegativeEmotions’, International Journal of Play, 2.3 (2013), p.277

22 Coffey, P. F., and Di Giusto, J ‘TheEffectsofWaitingTimeandWaitingRoomEnvironmentonDentalPatients’Anxiety’, Australian Dental Journal, 28.3 (1983), p.139–142

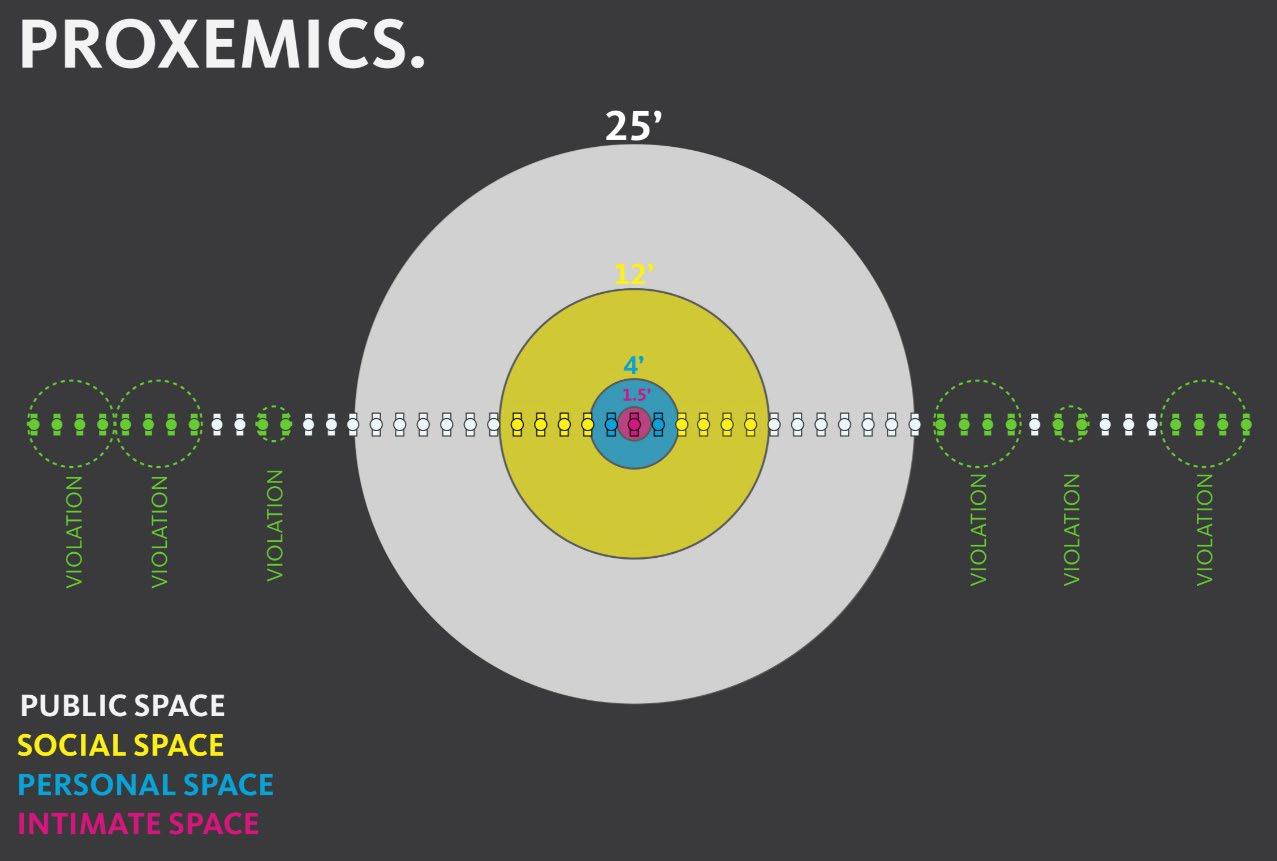

Airports are well-known for frequent periods of waiting. 23 Houston Airport received an excessive number of complaints regarding wait-time for baggage claims, which they responded to by increasing the number of handlers to decrease this time. 24 When the complaints continued, they further considered the issue and found that while the typical walk to baggage claim was only 2 minutes, the wait at the baggage claim carousel was an average of 8 minutes which meant that visitors were spending 80% of their wait standing. As a result, the airport decided to re-direct the baggage to a carousel further from the gate, increasing the average waiting time of visitors but making it so that they were spending the majority of this time walking to the carousel rather than standing, as shown in Figure 5. 25 This had a significant positive impact on the overall experience and no further complaints were received. This example highlights how the transitionary space connected to a waiting area can be adapted to improve the overall waiting experience, highlighting that innovative solutions are emerging that delve beyond mere reduction of waiting time. The designed intervention within this research project revolves around a similar

23 Natvisa, ‘WaitingAreasatInternationalAirports’ <https://www.natvisa.com/blog/waiting-areas-at-international-airports>

24 Burkeman, O, ‘HowaLongerWalktoBaggageReclaimCutComplaints’, The Guardian, (2018) <https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/sep/07/how-to-beat-bottlenecks-oliver-burkeman>

25 Foster, D. G., ‘WaitingandtheArchitectureofPre-Occupation’, Architecture Thesis Prep, (2012)

concept to the study undertaken at Houston Airport, which also shows that the waiting time was not the issue for visitors, but rather what they were doing during that time – or, more precisely, whether their attention was otherwise engaged.

One of Richard Larson’s elements, environment, states that the perception of a wait is heavily impacted by the atmosphere surrounding the queue.a, 26 When teller-aided ATM transactions were first introduced at Manhattan Savings Bank, queue complaints soared during lunch hour, as an influx of people would arrive and suffer from long wait-times. 27 To resolve this, mirrors were placed within the space and concert pianists were brought in to perform, with the aim of distracting customers from the queue, as shown by Figure 6. Larson suggested that ‘waiting time reduction may not be as important as imaginative lobby design’, which provides opportunity for the manipulation of architecture to positively influence these experiences.30 In addition, it shows that efforts are better spent on the preoccupation of waiting individuals rather than reduction of time spent waiting. Even when individuals remain standing, there is ample opportunity to sufficiently distract their attention from the queue. This example suggests that architecture and design can have an even greater impact on the psychological effects of waiting; it shows sensory information is enough to effect individuals, similar to the way that touch and movement are used in the designed intervention within this research project.

a. Richard Larson’ is ‘a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has studied queuing for 40 years, further information about him can be found, starting with Wollan, M., ‘How to Wait in Line’ , The New York Times Magazine, (2021) < https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/16/magazine/how-to-wait-in-line.html>

26Larsen, D. ‘New Research on the Theory of Waiting Line (Queues), Including the Psychology of Queueing’, INFORMS, (2012) < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CBD2z51u5c>

27Foster, D. G., ‘WaitingandtheArchitectureofPre-Occupation’, Architecture Thesis Prep, 214 (2012)

During an investigation into the effect of an ‘action-orientated’ room transformation, introducing stimulating object design and surface design, it was found that tactile and haptic elements reduced stress-waiting-behaviours. This ‘increased both positive overall room perception and the evaluation of specific room characteristics among clients/patients’ in waiting rooms within the service sector. 28 The study on action-orientated room transformation used observational methods to record ‘indicators of stress, relaxation, and social interaction’, like the approach that will be taken in the study of this dissertation research project.31 There is potential that play can be used to mitigate negative behaviours.

3.1 - PSYCHOLOGY OF PLAY

While play has long been recognised as a vital component of child development, it has become clear that it is also a necessity for adults, given the advantages it has on the ‘physical, mental, and social’ wellbeing for ‘people of all ages ’ 29 Play has the potential to be used as a form of emotional regulation, by means of distraction and preoccupation; it provides people of all ages the opportunity to release stress in a functional manner. 30 While investigating the playfulness of young adults alongside perceived stress and coping strategies, it was found that playful individuals experienced lower levels of perceived stress than those that were less playful. These playful individuals were found to make use of ‘adaptive, stressor-focused coping strategies’ and tended not to employ ‘negative, avoidant, and escape-orientated coping strategies’. 31

Numerous links have been made between play and other positive factors, such as ‘enhanced group cohesion, creativity and spontaneity, intrinsic motivation, quality of life, decreased computer anxiety, positive attitudes towards the workplace, job satisfaction & performance, innovative behaviour, and academic achievement’ 32 The presence of these relationships heavily suggests that investigating the role of play in adult life is a necessity in order to further the current understanding of how playful behaviour can better everyday life.

28 Klingemann, H , Scheuermann, A Laederach, K Krueger, B Schmutz, E Stähli, S & Others, ‘PublicArtandPublicSpace – WaitingStressandWaitingPleasure’, Time & Society, 27.1 (2018), p.69–91

29 Fein, Greta G., ‘PretendPlayinChildhood:AnIntegrativeReview’, Child Development, 52.4 (1981), p.1095–1118; Hartt, M, ‘ExpandingthePlayfulCity:Planningfor OlderAdultPlay’, Cities, 143 (2023)

30 Chang, P, Qian, X, Yarnal, C, ‘UsingPlayfulnesstoCopewithPsychologicalStress:TakingintoAccountBothPositiveandNegativeEmotions’ International Journal of Play, 2.3 (2013), p.274

31 Magnuson, C , D , Barnett, L., A.,‘ThePlayfulAdvantage:HowPlayfulnessEnhancesCopingwithStress’, Leisure Sciences, 35.2 (2013), p.129–44

32 Proyer, R., T., and Willibald R., ‘The Virtuousness of Adult Playfulness: The Relation of Playfulness with Strengths of Character’, Psychology of Well-Being: Theory, Research and Practice, 1.1 (2011) p.2

3.2 - BEHAVIOUR OF PLAY

Play can be considered through very different lenses, determined through the eye of the beholder. For this very reason, playful behaviour has been described using numerous definitions, which serve to encapsulate these behaviours from different perspectives. One viewpoint approaches it as a ‘behaviour or activity that is carried out withthegoalofamusement , and fun ’ while other angles define multiple characteristics which can be applied to potential playful behaviours. 33 This includes Johan Huizinga’s theory that play is free, rule defined, within fixed boundaries, distinct from ordinary life, and not in material interest. 34 These varying definitions can be explored in relation to behaviours observed within this study.

3.3 - APPLICATION OF PLAY

Urban play elements encompass smaller-scale interventions in typically constrained areas, these are considered based on their ability to inspire playful actions and sensory perceptions, such as street furniture, play equipment, and artworks. 35 Providing these spaces in areas near places of work and living allows more opportunity to play. This is because these spaces are integrated into daily life and therefore are easy to access alongside everyday routes. The Volkswagen experiment in Stockholm (Figure 7) carried out the ‘Piano Staircase Initiative’, where piano keys were installed in a transitionary space on the staircase of OdenPlan Subway Station. It was found that ‘66% more people than normal chose the stairs over the escalator’ 36 This highlights the ease of which these playful interactions can be utilised in transitionary spaces particularly if the interventions are placed in convenient locations. Play can be used as a form of emotional regulation in order to mitigate negative psychological symptoms that may be experienced during the waiting process.

33 Van Vleet, M , Feeney, B , C , ‘YoungatHeart:APerspectiveforAdvancingResearchonPlayinAdulthood’, Sage Journals, 10.5, (2015) p.639-645

34 Huizinga, J , ‘HomoLudens:AStudyofthePlay-Elementin Culture’, The Beacon Press, (1944)

35 Candiracci, S , R , Conti L , Dabaj, J , Moschonas, D , Hassinger-Das, B , Donato, J., ‘PlayfulCitiesDesignGuide’, (2023)

36 Volkswagen, ‘TheFunTheory1 – PianoStaircaseInitiative|Volkswagen’, (2009) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SByymar3bds>

4.1 - METHOD

After investigating existing research, the chosen method for this dissertation project will be in the form of an observational study. Due to the public setting of the experiment, it has been decided that informed consent is not required from study participants, given that no personal information will be recorded and there will be no breach of personal space throughout the investigation This study will be conducted on 2 separate days (Friday 10am-2pm, on 24/11/23 and 01/12/23) in the same waiting area. The researcher will note the behaviours exhibited by subjects, both on 24/11/23 when the installation is not present and then on 01/12/23 when the instrument of measure is in place All witnessed behaviours will be recorded with notes, as well as recording the number of people, both passing by and exhibiting behaviours of interest. These behaviours will then be classified and grouped retrospectively. During the brief pilot study (Appendix A) that was conducted with the same methodology, there were no obvious signs of investigator bias

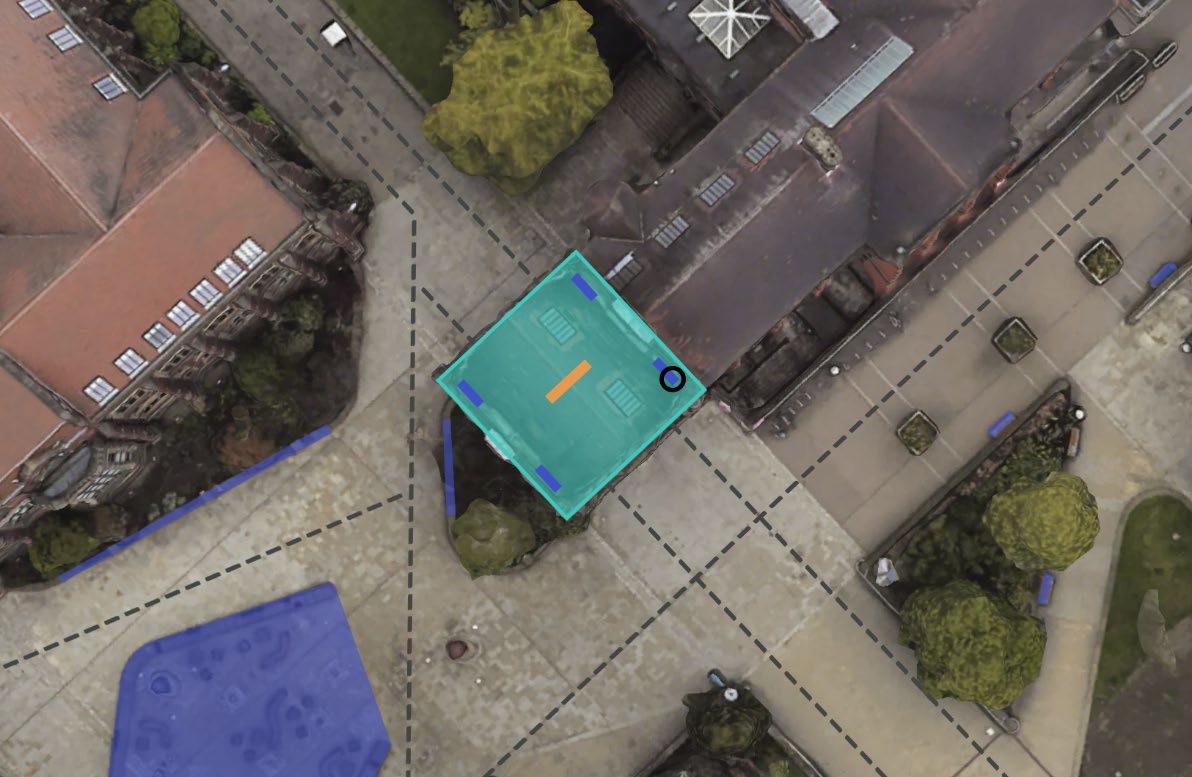

The area of observation that will be used is in the Quadrangle of Newcastle University campus, in the city centre of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. It is primarily a transitionary space but can also be used as a waiting space. The following analysis of this area outlines these aspects, alongside other information that serves to better represent the overall location.

Area of Observation

Seating

Position of Installation

Position of Observer

Pedestrian Routes

4.2 - ETHICS

The ethics of this study have been approved by the Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences at Newcastle University, allowing for the observational study to take place, without the requirement for informed consent, given the public nature of the space that will be used. An extensive risk assessment has been undertaken in collaboration with the technicians from the Architecture, Planning & Landscape Workshop, which was then approved by the school director.

Table 1 - Number of People Exhibiting Behaviours of Interest with and without a Playful Intervention Present

People

The term ‘environmental engagement’ was used to describe participants that did not physically interact with the instrument of measure or surrounding space but did give either their attention in some manner. ‘Playful’ behaviour is used to encompass physical engagement with the installation, or other actions that might be considered playful. ‘Joyful’ behaviours surround expressions of joy, such as smiling or laughing, that were not accompanied by playful behaviours. Walking simply refers to those that did not stray from their route at all.

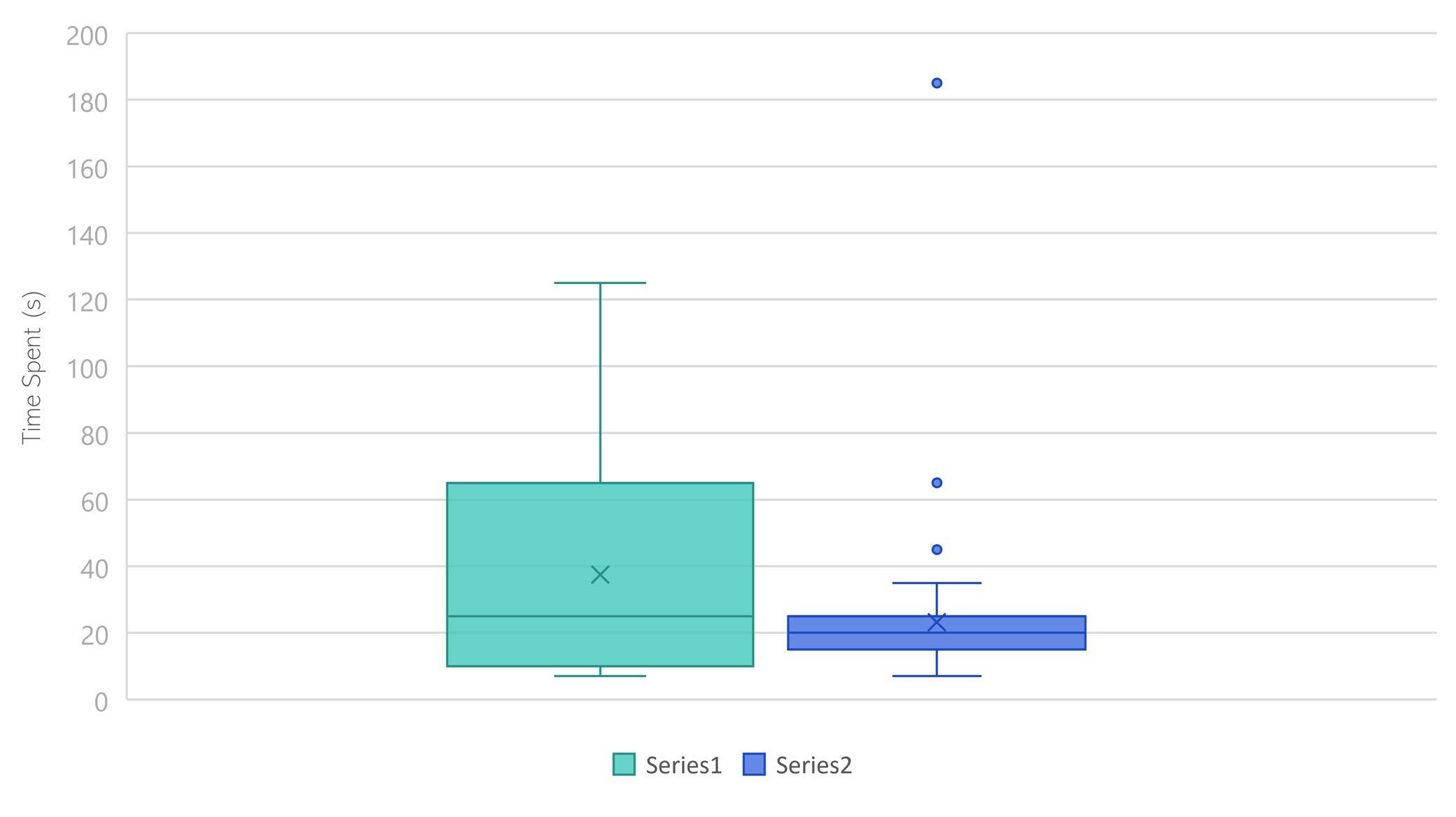

Figure 9 - Number of People Exhibiting Behaviours of Interest with and without a Playful Intervention Present

Behaviours Exhbited

Figure 9 shows a significant increase in the number of people exhibiting environmental engagement and playful behaviours during the day the intervention was present, along with a smaller increase of joyful behaviours.

Figure 10 - Time Spent within Waiting Area with and without Playful Intervention Present

Analysing the time people spent within the waiting area on both days, the range of time spent was larger with the intervention present, varying from 7 to 125 seconds, whereas the range of time spent without an intervention present was from 7 to 35 seconds. This excludes 3 outliers in the data which exceeded the upper bound of the interquartile range

The data collected indicates that people were likely to spend less time within the waiting area with no intervention compared to when the intervention was installed (Figure 10) Figure 9 also shows that people were less likely to exhibit behaviours of interest without an intervention present, including engaging with the environment, playful behaviours, and joyful behaviours.

While interacting with the installation, 21 participants were observed laughing, while a minority of users (3 people) seemed hesitant in their use of the bench, mentioning that “there’s just something weird about it”, while another stated “oh no, I’m scared.” In one instance, the age gap between participants seemed to negatively affect their ability to engage with the installation. In this example a young child and elderly person sat either side, while the child tried their best to propel their side of the bench, the elderly participant on the opposite side sat in a stationary position, meaning that the bench did not rock despite the efforts of the child.

It must also be noted that the positioning of the intervention was in the centre of the waiting area, which has been highlighted as an uncomfortable position for people to sit in public spaces. 37 This could not be avoided due to the poor weather conditions, which required shelter, and the slope of the ground which eliminated the possibility of the bench being rotated, as this would have stopped it from rocking effectively. This may have reduced the number of participants that interacted with the installation.

Walking (96.333%)

Engaging with Environment (2.332%)

Playful Behaviour (0.980%)

Joyful Behaviour (0.355%)

Walking (99.703%)

Other (0.297%)

Engaging with Environment (0.104%)

Playful Behaviour (0.074%)

Joyful Behaviour (0.119%)

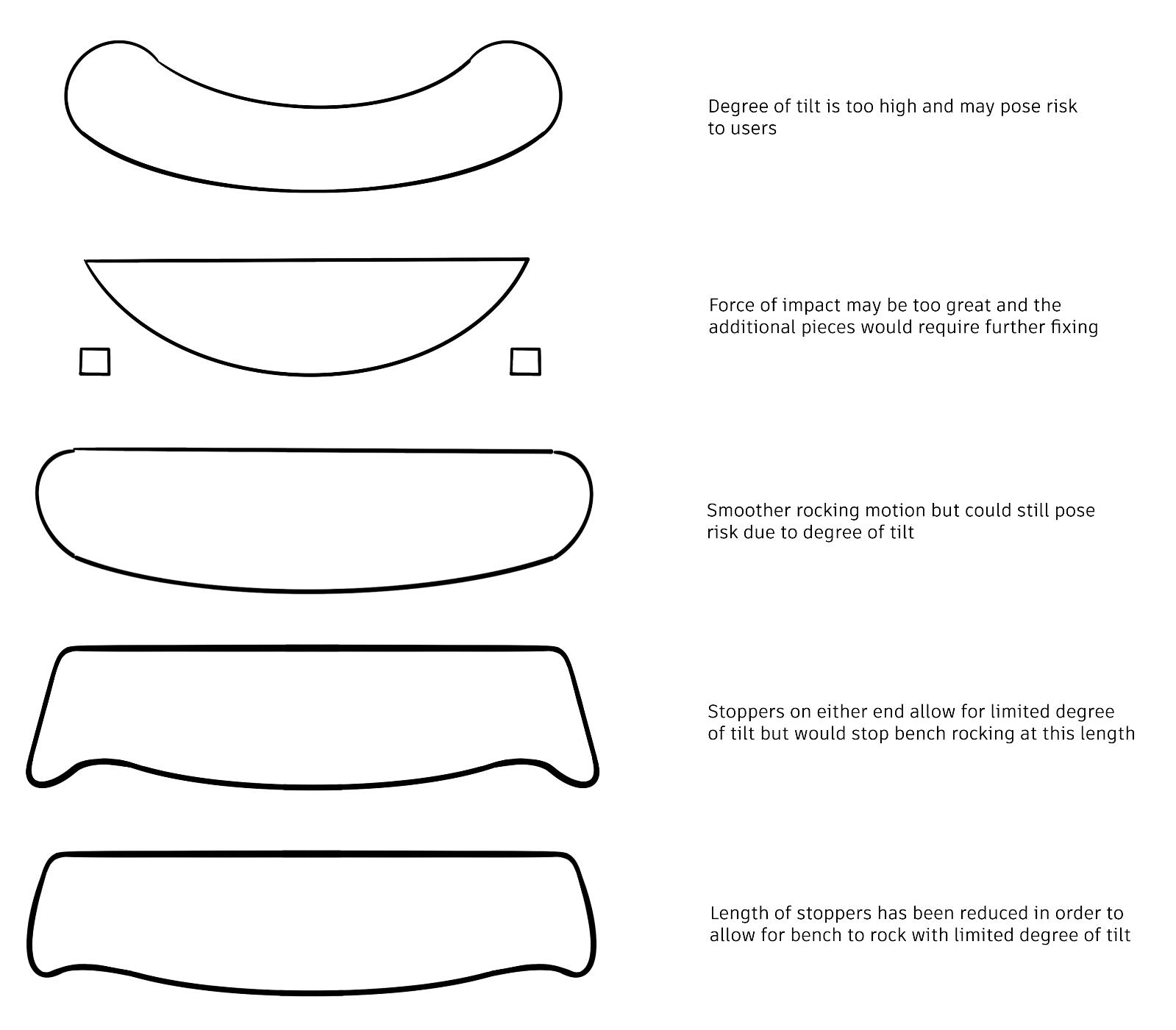

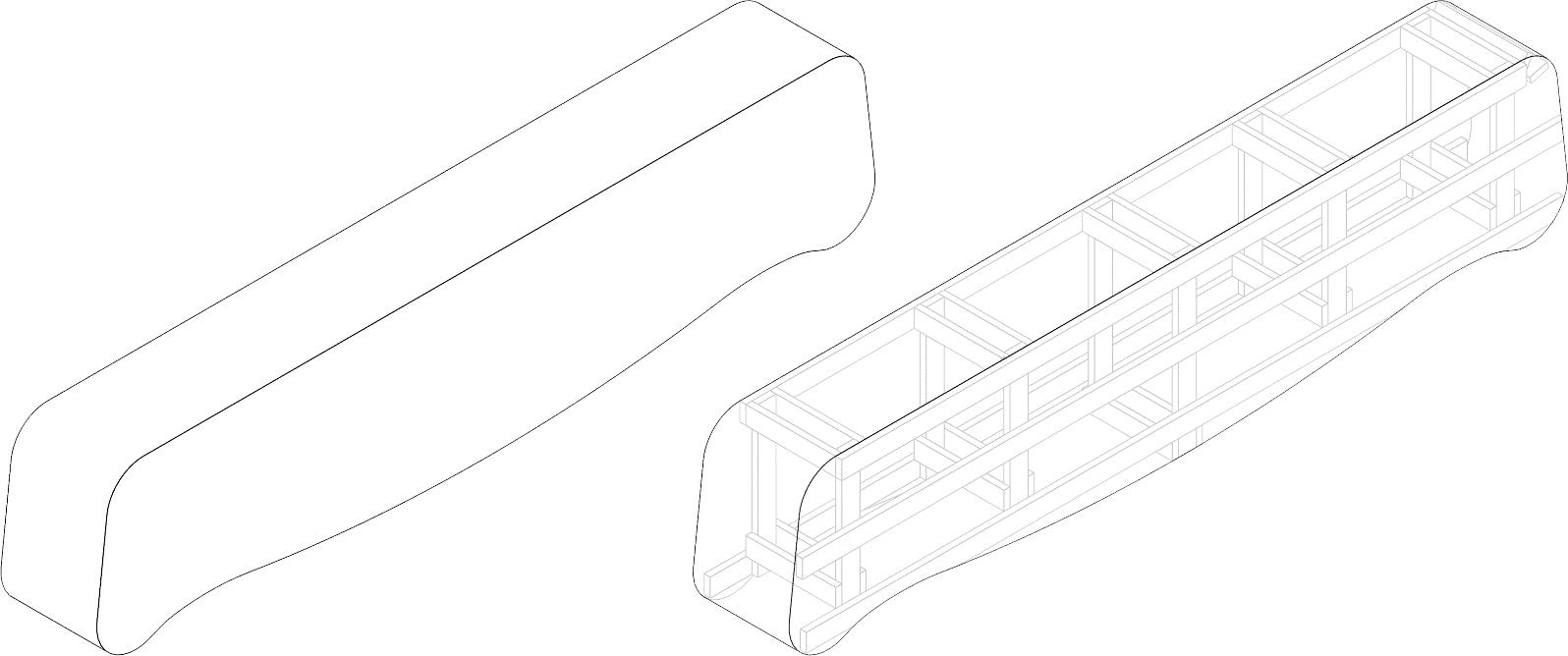

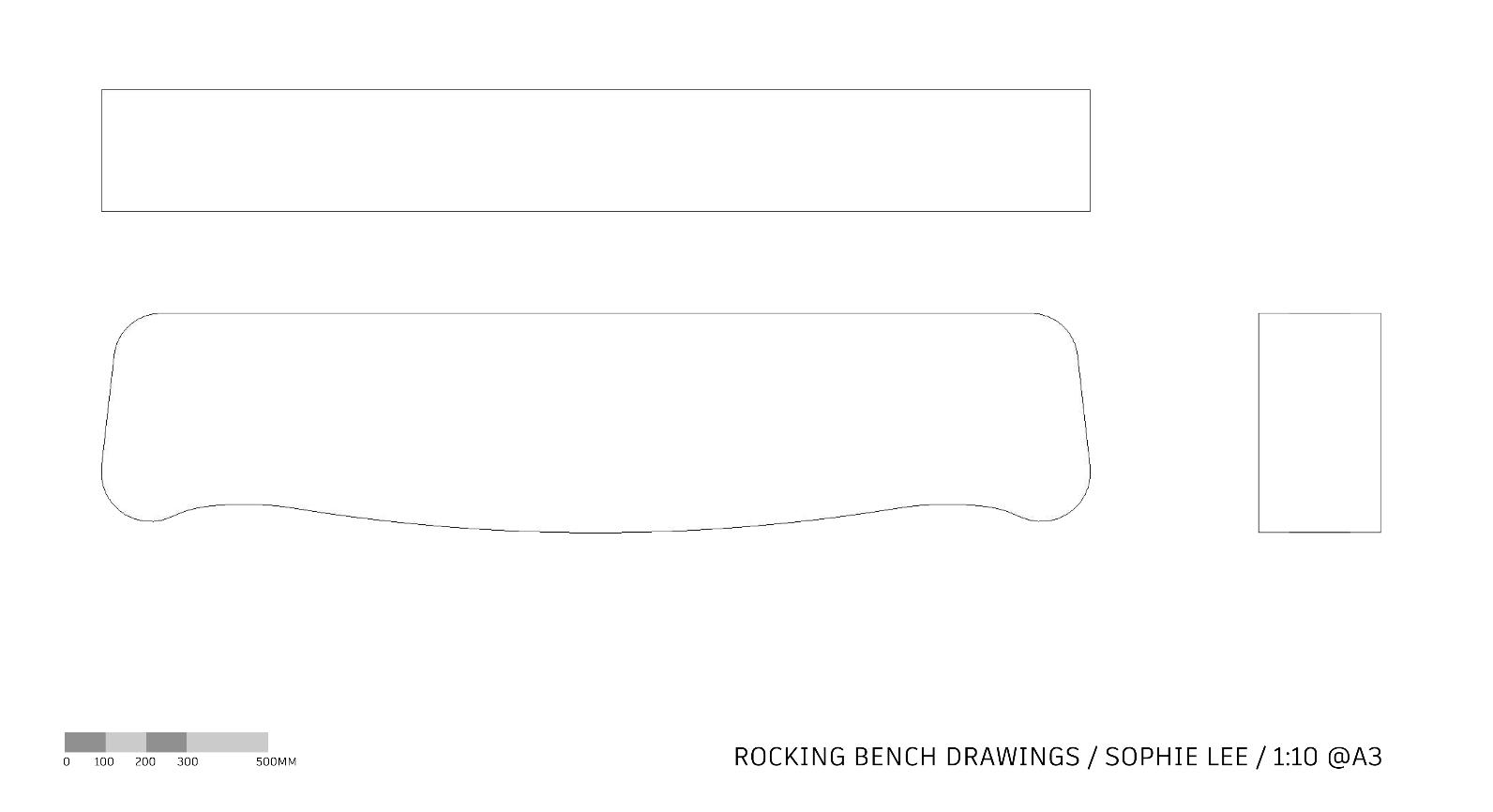

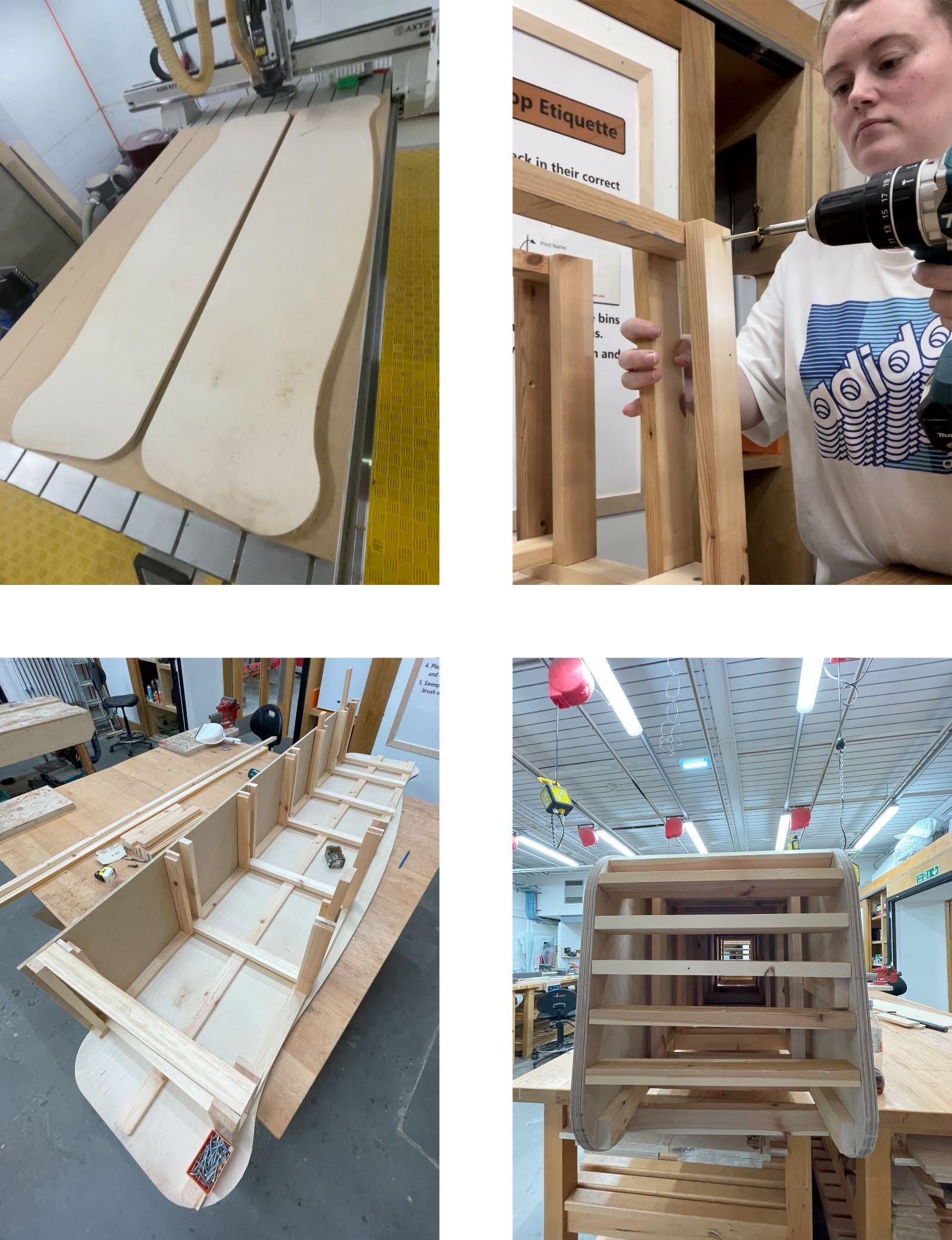

The process of this installation began with precedent research into previous installations developed with a similar intention of encouraging playful behaviour. This will then influence the design of my installation, followed by the construction

5.1 - PRECEDENTS

Many precedents were found during my attendance of a Summer School (2023) at Bauhaus University in Weimar, Germany. A collection of photographs showcasing these precedents will follow, with brief explanations on the influence these works may have had on my own creation.

I was particularly intrigued by the abstract forms installed in the plaza in Figure 13, considering how well they suited this space, which is primarily adopted by youths for skateboarding and roller-skating. It appears this demographic has been catered towards in the design, which saw much use of both obstacles and seating during my stay. Despite the contrast in users and activities between this example and that of my own installation, the design and suitability of the pieces are something that I hope to carry into my own creation.

Out of all the playful installations I witnessed throughout Weimar, those intended as seating generally had the most use compared to other waiting activities. In Figure 14, the swing (top-centre) and the rocking seat (bottomleft) saw the most users, both having an element in common; these pieces allow for movement while in use, as well as the possibility for interaction with more than one user. The swing allows for interaction between a user and a participant, while the rocking seat is wide enough to comfortably allow for two people to sit side by side. Given the success of these examples, I would like to incorporate these two elements into my own instrument of measure and allow for both movement and interaction during its use

Some of the more sculptural installations throughout Weimar tended to be catered towards a younger demographic from children to young adults, given the fact that they generally required more effort to use, through climbing, squatting, or balancing. These examples were very popular amongst children and despite this not being my targeted demographic, it is worth noting that these also inspire movement during use, which aligns with the goals I’ve outlined previously.

Applying 3 coats of varnish to entirety of bench

Using a fine grit sandpaper to create a smooth finish

Considering the various definitions of play that exist, it is worth examining how these align with the playful behaviours exhibited throughout this dissertation study. When considering play as a ‘behaviour or activity that is carried out withthegoalofamusement,andfun ’ it would appear as though all the playful interactions recorded would adhere to this. 38 By engaging with the installation, participants are carrying out an action with the intention of rocking the bench, using hand or body, with little reason for doing so other than their own ‘amusement, enjoyment, and fun’. However, it may be argued that a small number of these interactions were simply motivated by curiosity, following ‘the impulse toward better cognition’. 39 The five characteristics of play outlined by Huizinga summarise that play is free, rule defined, within fixed boundaries, distinct from ordinary life, and not in material interest. 40 Within this context, the play exhibited by participants was certainly voluntary and free, and did take place within fixed boundaries, adhering to the vicinity of the installation. However, it is uncertain whether these behaviours occurred within a pre-determined set of rules, given that they are described to be ‘absolutely binding with room for no doubt’ in Huizinga’s definition.41 If there were any rules within the context of this study, they would likely relate to the reading of the instrument as a seesaw, as many participants referred to it. In line with this concept, the rules may consist of one person sitting on either side of the bench and taking turns to propel their respective side. When groups of people engaged with the bench, this tended to be the order that was adhered to, however there were a small number of instances where this was not the case. Some sat upon the bench in larger groups, while others carried out the actions as an individual, which suggests a lack of defined rules and opposes this aspect of the definition. However, it does appear to conform with the characteristic stating a lack of material gain, as there were no identifiable rewards to be gained from their actions as they engaged in play. Whether or not the behaviours occurred in a setting distinct from ordinary life may require further exploration, but it is worth noting that these interactions did interrupt the activities of participants and were decidedly distinct from their previous walking, in line with this aspect of the characteristic.

The initial literature research that was undertaken highlighted some key points that can be used as a point of reference when examining the findings of this dissertation study. Maister’s observation that ‘occupied time feels shorter than unoccupied time’ indicates that waiting experiences are more comfortable for people when they are occupied than not. 41 Figure 10 shows a larger number of participants choosing to spend more time within the transitionary space with the intervention present, suggesting its presence made the space more appealing to inhabit in some way, in turn allowing these people to stay in the space for a greater length of time. An exploration

38 Van Vleet, M., Feeney, B. C., ‘YoungatHeart:APerspectiveforAdvancingResearchonPlayinAdulthood’, Sage Journals, 10.5, 640 (2015) p.553

39 Kennedy, J., J., ‘Is EmotionalCuriositytheKey?’, Psychology Today, (2020) <https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/brain-reboot/202011/is-emotionalcuriosity-the-key>

40 Huizinga, J , ‘HomoLudens:AStudyofthePlay-Elementin Culture’, The Beacon Press, (1944)

41 Maister, David H, ‘The Psychology of Waiting Lines’, (2005)

into the thoughts and feelings of participants would be a beneficial area of exploration in further study, to gain more insight into the exact ways the playful intervention affected those passing through.

Many of the precedents which were studied prior to the observational study – had installed their own instrument of measure into a transitionary or waiting space and saw an increase in the playful behaviours that were observed following the installation. 42 The Volkswagen experiment in Stockholm featured the transformation of a transitionary space, by installing piano keys on the stairs into the Odenplan subway station 43 This example found that 66% more commuters used the stairs rather than the escalator during the period that the intervention was present, exhibiting playful behaviour each time they used the stairs and creating music as a result. Similarly, the results of this dissertation project align with this precedent research given the increase in playful behaviours that were exhibited by the public. This number was a smaller proportion of participants than that of the precedent studies. This may be due to the type of installation, which involves sitting, being employed in a transitionary space which is primarily for passing through, therefore walking, rather than sitting. Future study would highly benefit

42 100architects, ‘Projects’ , 100 Street Architecture & Street Interventions <https://100architects.com/projects/> 43 Volkswagen, ‘TheFunTheory1 – PianoStaircaseInitiative|Volkswagen’, (2009) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SByymar3bds>

from the installation of a piece which aligns with the existing actions expected of the space, like the Volkswagen experiment which only required stepping and did not insist upon any further actions.

As shown in the earlier subject research, the use of play as a form of emotional regulation is an effective tool for people of all age groups, typically by means of distraction or preoccupation. 44 Within the collected data, a significant number of people who interacted or engaged with the bench were observed smiling and laughing as a result. Laughing can serve as both a result of humour and social interaction given its contagious nature 45 The presence of laughter in this case could be the result of either factor, where laughing participants may be finding humour through the intervention or responding to other members of the group who are experiencing this. Either way, this would indicate a positive effect on the mental wellbeing of participants, given the release of stress that would accompany the behaviour 46

Conversely, there were no indicators of stress observed in those waiting within the space on either day, unlike the many behaviours recorded during the pilot study in Appendix A. The difference being, the pilot study was conducted by observing interactions surrounding a bus shelter, which is a specific waiting area, rather than the transitionary space under The Arches, observed in this case. This information may indicate that the participants were not experiencing stress during the observations, contrary to the findings of previously mentioned research. The fact that The Arches are not actually a waiting space, so much as they are a transitionary space, may give reason to this, as the majority of participants within the space were simply passing through and the primary use of the space is not waiting. Further study would benefit from a similar approach, using a specific waiting area rather than a transitionary space, to determine whether the lack of stressful behaviours was indeed a result of the space used or a lack of interaction with participants during the study

The observations show a distinct lack of playful behaviour with no intervention present compared to when it had been installed. Within the microcosm of Newcastle University Campus, this suggests that the numerous transitionary areas throughout the site may benefit from the addition of similar playful installations. It could be assumed from these results that making these changes would further encourage playful behaviour on a wider scale, in turn, aiding the mental wellbeing of the student population. At this point, it is worth considering the implications these alterations could have on a larger scale. If such installations could be integrated into the wider urban landscape, it would allow for a multitude of playful environments that serve to encourage play in people of all ages. In transitionary spaces, this could serve to slow down passersby and provide a moment of brief respite

44 Qian, X L , Yarnal, C., ‘TheRoleofPlayfulnessintheLeisureStress-CopingProcessamongEmergingAdults:AnSEMAnalysis’, Leisure/Loisir, 35.2 (2011), p.191–209

45 Provine, R . R., ‘Contagious Yawning and Laughing: Everyday Imitation- and Mirror-like Behavior’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28 (2005), 142 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X05390030>

46 Proyer, R , T , ‘The Well-BeingofPlayfulAdults:AdultPlayfulness,SubjectiveWell-Being,PhysicalWell-Being,andthePursuitofEnjoyableActivities’, European Journal of Humour Research, 1 (2013), p.84–98

throughout a typically busy schedule In waiting spaces, it would allow for the opposite effect. For commuters, in specific waiting areas, that may be forced to wait in a determined area, there is the opportunity to provide a distraction from the potential psychological stress or discomfort that they may experience due to waiting. 47 The presence of a playful intervention may serve to preoccupy lone commuters from their ruminations and provide groups with a topic of discussion, if not a tool for play. In a similar vein, these instances can become much more than a simple interaction. In line with the musings of Gaston Bachelard in The Poetics of Space , buildings and spaces can provide the foundation for moments and memories alike. 48 As playful interventions are introduced into spaces, it is possible for these installations to act as an engine for the creation of memories, small moments in which strangers, families, or friends can come together as they engage with the object of their shared attention. These instances can affect the ways in which we relate to built spaces, as well as the thoughts and feelings they inspire.

8 - CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to determine whether the presence of a playful installation increases the number of playful behaviours observed in transitionary and waiting spaces. This aim was based on the findings of the literature review, which expressed the negative psychological effects of waiting as well as the psychological benefits of play. 49 An observational study was then carried out using an instrument of measure to observe participant behaviours. Ultimately, the findings from this study show that the presence of a playful installation can increase the level of playful and joyful behaviours in spaces of transition and waiting. This suggests that it is possible to provide a means of emotional regulation through playful intervention, by providing some level of distraction for users. However, the overall effectiveness of playful intervention remains unclear and would require further study to gain a better understanding of the effect on a person’s mental state and how this transpires in a specific waiting area with an end goal. Ultimately, this project lies within the subject of Architecture rather than Psychology, meaning that the underlying psychology of the experience was not central to this project.

Even without this data, the fact that the number of playful and joyful behaviours increased with the intervention present, enforces the argument that cities would benefit from playful interventions in waiting areas to encourage play in people of all ages. This would allow for the improvement of both mental and physical wellbeing in the population, while transforming otherwise uncomfortable tasks – such as waiting – into moments that can form

47 Osuna, E E ‘ThePsychological Cost ofWaiting’, Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 29.1 (1985),<https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2496(85)90020-3> p.82–105

48 Bachelard, G., ‘ThePoeticsofSpace’, Beacon Press, (1985)

49 Osuna, Edgar Elías, ‘The Psychological Cost of Waiting’, Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 29.1 (1985), p.82–105; Magnuson, C , D , and L , A , Barnett, ‘The Playful Advantage: How Playfulness Enhances Coping with Stress’, Leisure Sciences, 35.2 (2013), p.129–144 <https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.761905>

memories and stories alike. The question then remains as to the most appropriate types of installations that can be used and what effect these would have on the user experience.

Table 1 – Author’s Table, 2023

10 - LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 – Author’s Diagram, 2024

Figure 2 – Author’s Diagram, 2024

Figures 3, 5 & 6 – Foster, G. D, ‘Waiting and the Architecture of Pre-Occupation’, ArchitectureThesisPrep, SyracuseUniversity, 214 <https://surface.syr.edu/architecture_tpreps/214/>

Figure 4 – Author’s Photo, 2024

Figure 7 – Shuwan, ‘Piano Stairs – A New Reason for Choosing Straicases’, Actipedia , <https://actipedia.org/project/piano-stairs-new-reason-choosing-staircases> [accessed 5 January 2024]

Figure 8 – Author’s Diagram, 2023

Figure 9 – Author’s Bar Chart, 2023

Figure 10 – Author’s Box Plot, 2023

Figure 11 – Author’s Pie Chart, 2023

Figure 12 – Author’s Pie Chart, 2023

Figure 13 – Author’s Collage, 2023

Figure 14 – Author’s Collage, 2023

Figure 15 – Author’s Collage, 2023

Figure 16 – Author’s Drawing, 2023

Figure 17 – Author’s Model, 2023

Figure 18 – Author’s Drawing, 2023

Figures 19 - 26 – Author’s Photos, 2023

Figures 27 & 28 - Author's Photos, 2023

Figure 29 – Author’s Illustration, 2024

BOOKS

Boettger, T, ThresholdSpaces:TransitionsinArchitecture.AnalysisandDesignTools (Birkhäuser, 2014)

Cofer, Charles Norval, and Mortimer H. (Mortimer Herbert) Appley, Motivation:TheoryandResearch (New York, Wiley, 1964) <http://archive.org/details/motivationtheory00coferich>

Deterding, S, and S. P Walz, TheGamefulWorld:Approaches,Issues,Applications. (The MIT Press, 2015)

Doob, L. W, ‘Patterning of Time’, YaleUniversityPress , 1960

Faraone, C, Sarti, A, ‘IntermittentCities:OnWaitingSpacesandHowtoInhabitTransformingCities’, Architectural Design, 78.1 (2008) 40-45 < https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.607>

Gary, A. F., MeaningfulPlay,PlayfulMeaning , Human Kinetics Publishers, (1987)

Gehl, J., LifeBetweenBuildings:UsingPublicSpace , Island Press, (2011)

Gehl, J, and D Sim, SoftCity:BuildingDensityforEverydayLife, Island Press, (2019)

Heathcote, E, On the Street: In-Between Architecture, Heni Publishing, (2022)

Huizinga, J., ‘Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture’, The Beacon Press, (1944)

Janeja, M. K, Bandak, A, EthnographiesofWaiting, Bloomsbury, (2018)

Madanipour, A, WhosePublicSpace?:InternationalCaseStudiesinUrbanDesignandDevelopment, Routledge, (2009)

Montgomery, C, 11.Montgomery,C.HappyCity:TransformingOurLivesthroughUrbanDesign.London:Penguin Books.(2015) (London: Penguin Books, 2015)

Stevens, Quentin, TheLudicCity:ExploringthePotentialofPublicSpaces , 1st edn (Florence: Routledge, 2007) <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203961803>

Walz, Steffen, ‘TowardaLudicArchitecture:TheSpaceofPlayandGames’, Lulu Press, Inc (2023)

‘A Field Study Investigating the Effect of Waiting Time on Customer Satisfaction’ <https://doi.org/10.1080/00223989709603847>

‘A Golden Age of Play for Adults’, BPS<https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/golden-age-play-adults> [accessed 5 January 2024]

American Psychological Association, ‘APA Dictionary of Psychology: Interviewer Effect , <https://dictionary.apa.org/interviewer-effect> [accessed 25 December 2023]

‘A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Adult Play and Playfulness’ <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/21594937.2017.1384307?needAccess=true> [accessed 2 October 2023]

Aarts, Marie-Jeanne, Wanda Wendel-Vos, Hans A. M. van Oers, Ien A. M. van de Goor, and Albertine J. Schuit, ‘Environmental Determinants of Outdoor Play in Children: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 39.3 (2010), 212–19 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.008>

Afonso, A., G, and A. Schieck F, ‘Play in the Smart City Context: Exploring Interactional, Bodily, Social and Spatial Aspects of Situated Media Interfaces.’, Behaviour & Information Technology , 39.6 (2020), 656–80 <https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1693630>

Barnett, L, ‘The Playful Child: Measurement of a Disposition to Play’, Play&Culture , 4 (1991), 51–74

Burkeman, O, ‘How a Longer Walk to Baggage Reclaim Cut Complaints’, The Guardian , 7 September 2018, section Life and style <https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/sep/07/how-to-beat-bottlenecksoliver-burkeman> [accessed 29 September 2023]

Chang, P, Qian, X, Yarnal, C, ‘Using Playfulness to Cope with Psychological Stress: Taking into Account Both Positive and Negative Emotions’, International Journal of Play , 2.3 (2013), 273–96 <https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2013.855414>

Coffey, P. a. F., and Di Giusto, J, ‘The Effects of Waiting Time and Waiting Room Environment on Dental Patients’ Anxiety’, Australian Dental Journal , 28.3 (1983), 139–42 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.18347819.1983.tb05268.x>

Covatta, A, and V Ikalovic, ‘Urban Resilience: A Study of Leftover Spaces and Play in Dense City Fabric.’, Sustainability , 14.20 (2022) <https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013514>

Csikszentmihalyi, M, ‘Play and Intrinsic Rewards’, Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 15 (1975), 14–63 <https://doi.org/10.1177/002216787501500306>

Donoff, Gabrielle, and Rae Bridgman, ‘The Playful City: Constructing a Typology for Urban Design Interventions’, International Journal of Play , 6.3 (2017), 294–307 <https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1382995>

Durrande-Moreau, Usunier, A, ‘Time Styles and the Waiting Experience.’, JournalofServiceResearch , 2.2 (1999), 173–86 <https://doi.org/10.1177/109467059922005>

Fein, Greta G., ‘Pretend Play in Childhood: An Integrative Review’, ChildDevelopment , 52.4 (1981), 1095–1118 <https://doi.org/10.2307/1129497>

Foster, D. G., ‘Waiting and the Architecture of Pre-Occupation’, ArchitectureThesisPrep , 2012

Frankel, Frederick D., Clarissa M. Gorospe, Ya-Chih Chang, and Catherine A. Sugar, ‘Mothers’ Reports of Play Dates and Observation of School Playground Behavior of Children Having High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 52.5 (2011), 571–79 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02318.x>

‘Full Details and Actions for The Ambiguity of Play’ <https://www.vlebooks.com/Product/Index/15567?page=0&startBookmarkId=-1> [accessed 2 October 2023]

Graham, Michael, Matthew Wright, Liane B. Azevedo, Tom Macpherson, Dan Jones, and Alison Innerd, ‘The School Playground Environment as a Driver of Primary School Children’s Physical Activity Behaviour: A Direct Observation Case Study’, Journal of Sports Sciences , 39.20 (2021), 2266–78 <https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1928423>

Hartt, Maxwell, ‘Expanding the Playful City: Planning for Older Adult Play’, Cities , 143 (2023), 104578 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104578>

Hess, Daniel, Jeffrey Brown, and Donald Shoup, ‘Waiting for the Bus’, Journal of Public Transportation , 7.4 (2004), 67–84 <https://doi.org/10.5038/2375-0901.7.4.4>

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL) and Business Research Unit (BRU/UNIDE) and SOCIUS, Sandra Maria Correia Loureiro, Eduardo Moraes Sarmento, Universidade Lusófona and ISEG/UTL, Rui Lopes, Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), and others, ‘Feeling Better While Waiting: Hospital Lobby in Portugal and South Korea’, Asian Journal of Business Research , 5.2 (2015) <https://doi.org/10.14707/ajbr.150017>

Klingemann, Harald, Arne Scheuermann, Kurt Laederach, Birgit Krueger, Eric Schmutz, Simon Stähli, and others, ‘Public Art and Public Space – Waiting Stress and Waiting Pleasure’, Time&Society , 27.1 (2018), 69–91 <https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X15596701>

Koch, R, ‘Review of Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life by Karen A. Franckland Quentin Stevens.’, New Zealand Geographer , 66 (2010), 174–76 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17457939.2010.01183_6.x>

Koole, Sander L., ‘The Psychology of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review’, CognitionandEmotion , 23.1 (2009), 4–41 <https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802619031>

Larsen, L. J, ‘Play and Space – towards a Formal Definition of Play’, International Journal of Play , 4.2 (2015), 175–89 <https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2015.1060567>

Maister, David H, ‘The Psychology of Waiting Lines’, (2005)

Magnuson, Cale D., and Lynn A. Barnett, ‘The Playful Advantage: How Playfulness Enhances Coping with Stress’, Leisure Sciences , 35.2 (2013), 129–44 <https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.761905>

Nijholt, A, ‘Smart, Affective, and Playable Cities’, Interactivity,Game Creation,Design, Learning, and Innovation , 265 (2019), 163–68

Osuna, Edgar Elías, ‘The Psychological Cost of Waiting’, JournalofMathematicalPsychology , 29.1 (1985), 82–105 <https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2496(85)90020-3>

Paris, Rainer, ‘Waiting in the Hallways of Bureaucratic Organizations’, Kolner Zeitschrift Fur Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie - KOLNER Z SOZIOL SOZIALPSYCHOL , 53 (2001), 705–33

Proyer, R. T, ‘A New Structural Model for the Study of Adult Playfulness: Assessment and Exploration of An Understood Individual Differences Variable’, Personality and Individual Differences, 108, (2016) 113-122

Proyer, R, T, ‘The Well-Being of Playful Adults: Adult Playfulness, Subjective Well-Being, Physical Well-Being, and the Pursuit of Enjoyable Activities’, European Journal of Humour Research , 1 (2013), 84–98 <https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-78008>

Proyer, R. T, ‘PerceivedFunctionsofPlayfulnessinAdults:DoesItMobilizeYouatWork,Rest,andWhenBeing with Others? ’, Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée , 64 (2014), 241–50 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.06.001>

Proyer, R. T, F Gander, E. J Bertenshaw, and K Brauer, ‘The Positive Relationships of Playfulness with Indicators of Health, Activity, and Physical Fitness’, Personality and Social Psychology (Frontiers in Psychology) , 9 (2018)

Proyer, René T., and Willibald Ruch, ‘The Virtuousness of Adult Playfulness: The Relation of Playfulness with Strengths of Character’, Psychology of Well-Being: Theory, Research and Practice , 1.1 (2011), 4 <https://doi.org/10.1186/2211-1522-1-4>

Qian, Xinyi Lisa, and Careen Yarnal, ‘The Role of Playfulness in the Leisure Stress-Coping Process among Emerging Adults: An SEM Analysis’, Leisure/Loisir , 35.2 (2011), 191–209 <https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2011.578398>

Rasmussen, K, ‘Places for Children: Children’s Places.’, Childhood , 11.2 (2004), 155–73 <https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568204043053>

Ülkü, S, Hydock, C, Cui, S, ‘MakingtheWaitWorthwhile:ExperimentsontheEffectofQueueingonConsumption’, Management Science, 66.3 (2019) 1149-1171 <https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3277>

Van Leeuwen, Lieselotte, and Diane Westwood, ‘Adult Play, Psychology and Design’, Digital Creativity , 19.3 (2008), 153–61 <https://doi.org/10.1080/14626260802312665>

Van Vleet, Meredith, Vicki S. Helgeson, and Cynthia A. Berg, ‘The Importance of Having Fun: Daily Play among Adults with Type 1 Diabetes’, JournalofSocialandPersonalRelationships , 36.11–12 (2019), 3695–3710 <https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519832115>

Veitch, Jenny, Sarah Bagley, Kylie Ball, and Jo Salmon, ‘Where Do Children Usually Play? A Qualitative Study of Parents’ Perceptions of Influences on Children’s Active Free-Play’, Health & Place , 12.4 (2006), 383–93 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.02.009>

Van Vleet, M., Feeney, B. C., ‘Young at Heart: A Perspective for Advancing Research on Play in Adulthood’, Sage Journals, 10.5, 639-645 (2015)

WEBSITES

100architects, ‘Projects’ , 100 Street Architecture & Street Interventions <https://100architects.com/projects/> [accessed 3 April 2023]

A Playful City, ‘TheSpielMobile’, TheSpiel Mobile , 2018 <https://www.aplayfulcity.com/project-02> [accessed 24 March 2023]

Kennedy, J., J., ‘Is Emotional Curiosity the Key?’, Psychology Today, (2020) <https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/brain-reboot/202011/is-emotional-curiosity-the-key> [accessed 29 December 2023]

Maister, D., H., ‘My Bio’ , David Maister < http://about.davidmaister.com/bio/> (2023) [accessed 20 January 2024]

Mmmm… ‘Mmmm… Bus Stop’ (2014) <https://Www.Mmmm.Tv/Enbusstop.Html> [accessed 20 November 2023]’

National Institute for Play, ‘How We Play’, <https://www.nifplay.org/what-is-play/types-of-play/> [accessed 25 November 2023]

Natvisa, ‘Waiting Areas at International Airports’ <https://www.natvisa.com/blog/waiting-areas-at-internationalairports> [accessed 29 December 2023]

Sanyal, I, ‘PlayfulCitiesAreFreeCities’, Medium, (2017) <https://irasanyal.medium.com/playful-cities-are-freecities-ec76ca3be895>

Shondaland, ‘Adults Need Playtime as Much as Kids’ , (2021) <https://www.shondaland.com/live/body/a36123122/adults-need-playtime-as-much-as-kids/> [accessed 5 January 2024]

The Ethical Choice, ‘Bored at Your Road Crossing? Play Pelican Pong’, (2022) <https://www.eta.co.uk/2022/06/22/bored-at-your-road-crossing-play-pelican-pong/> [accessed 24 November 2023]

Wollan, M., ‘How to Wait in Line’, The New York Times Magazine, (2021) <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/16/magazine/how-to-wait-in-line.html> [accessed 20 January 2024]

World Health Organization, ‘Stress’ (2023) <https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-andanswers/item/stress> [accessed 16 December 2023]

DOCUMENTS

Candiracci, S, R. Conti L, J Dabaj, D Moschonas, B Hassinger-Das, and J Donato, ‘Playful Cities Design Guide’, 2023

Department for Transport, ‘Annual Bus Statistics: England 2020/21’ (2021) <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/618258868fa8f52985dd771c/annual-bus-statisticsyear-ending-march-2021.pdf>

VIDEOS Larsen, D. ‘New Research on the Theory of Waiting Line (Queues), Including the Psychology of Queueing’, INFORMS, (2012) < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_CBD2z51u5c>

Rolighetsteorin, ‘Piano Stairs - TheFunTheory.Com’ (2009) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2lXh2n0aPyw> [accessed 3 January 2024]

Volkswagen, ‘The Fun Theory 1 – Piano Staircase Initiative | Volkswagen’, (2009) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SByymar3bds> [accessed 3 January 2024]