A PROVEN SYSTEM FROM THE WORLD’S MOST SUCCESSFUL STARTUPS

‘The new playbook for building the future’ Reid Ho man, Founder of LinkedIn

‘The new playbook for building the future’ Reid Ho man, Founder of LinkedIn

with JOHN ZERATSKY

New York Times bestselling authors of SPRINT

ALSO BY JAKE KNAPP AND JOHN ZERATSKY

Make Time: How to Focus on What Matters Every Day

Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days (withBradenKowitz)

A Proven System From the World’s Most Successful Startups

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Torva an imprint of Transworld Publishers 001

Copyright © John Knapp and John Zeratsky 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Interior design by Ruth Lee-Mui

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781911709879

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This book is for the founders, leaders, and teams who inspired and taught us along the way.

And you. Yeah, you. This is for you and your team, too.

Dropeverythingandsprintonthemostimportantchallengeuntil it’sdone.

Experimentwithtinyloopsuntilyoursolutionclicks.Thenbuildit.

I run inside Orcas Island High School just as the late bell sounds, stumble on the threshold, and drop my three-ring binder. Sheets of paper explode across the linoleum floor. Panting, face hot with embarrassment, I scoop up the pages. I pat my coat pocket. The disk is still there.

Now, upstairs. Down the hall. First door on the left. I peek through the window, then give the handle a slow turn. The computer lab is empty except for one kid: my friend Ian.

“Dude,” Ian says. He’s spending his free period playing solitaire, stacking cards on the screen, his eyes glazed.

“I’ve got a new game,” I say. I bring out the floppy disk I’ve carried from home and hand it to him.

It’s 1993, I’m fifteen years old, and the software on the disk is not just any old video game. It’s homemade. I’ve spent the past year, including my entire summer vacation, building this game, writing the code and drawing the artwork pixel by pixel. I wanted to keep it a secret until it was ready, and today? It’s ready. I’m excited. But I need an opinion from someone I can trust. Someone brutally honest. Someone like Ian.

He arches an eyebrow and takes the disk. Then the door bangs open and our friend Matt barges into the computer lab.

“What’s this?” he says, joining Ian beside the computer.

“Some new game,” Ian says as he begins to play. I stand back, silent and nervous, and watch.

The game is your typical swords-and-sorcery castle adventure. Ian figures out the controls and begins moving from room to room. His character finds a torch and then a dagger and then . . .

“Eh,” Ian says. He scoots back and looks at Matt. “Want a turn?”

Wait, what? Something’s wrong. Ian’s character hasn’t died. He hasn’t even fought a monster yet. The Ian I know would never willingly hand over the keyboard midgame, unless . . . I wince. Unless the game is boring.

Matt takes over. And yeah, something is off. He’s not leaning forward. He’s not talking trash. This is not the Matt I know. When a giant spider kills his character, Matt does not start over to seek revenge. Instead he stands, stretches, and says, “You guys wanna shoot some hoops before our free period is over?”

“Let’s do it,” Ian says.

Damn it. They’re choosing exercise over a video game? My stomach sinks. All that work. How could I have been so stupid?

This book is about what I learned that day: Turning a big idea into a product that people love is really difficult. Getting it wrong can be a colossal waste of time and energy. Getting it wrong hurts.

But there is a reliable way of getting it right. There is a system for making things that people love, and I first stumbled on it back in high school—although it took me decades to recognize it.

After Ian and Matt shrugged off my castle adventure game, I was bummed. Still, I didn’t want to give up.

I realized it wasn’t enough to just make a game—if I wanted people

to actually play the game, it had to beat out the alternatives. During free period, that meant my game had to be more fun than solitaire—which seemed doable. But my friends could also play basketball. They could listen to mixtapes on their Walkmans. They could walk to Island Market and buy a corn dog.

Basketball, Walkmans, corn dogs. Tough competition.

Now that I knew what I was up against, I went back to work, only this time, I ran experiments.

Every week or so, I would take just the beginning of a new game— a prototype—to school and show it to my friends. I tried space quests, strategy battles, sports games, you name it. Every time, they shrugged.

Until I came up with a game I called “Mealy Mouse.”

In Mealy Mouse, the player moved through a series of mazes. My friends didn’t exactly love it at first, but I saw promise in their reactions. They leaned forward when they tried it. So I kept experimenting. I sped up the pace of the game. I added loud and humiliating sound effects that went off whenever the player made a mistake.

One day, I brought a floppy disk to school, handed it to Ian, and this time? He kept playing until Matt shoved him over. This time? Matt talked trash. This time? My friends Sean and Sean got in on it. This time? Even girls tried the game. Nirvana.

Then our math teacher, Mr. Fleck, walked into the computer lab. He asked what the hell we were doing, then he watched, and then . . . he asked for the next turn.

Me? I sat back and watched them play. I was so stoked, I felt a thousand feet tall. Because, for the first time, I made something that clicked.

Every once in a while, a new way of doing things comes along and everything clicks. The new way solves an important problem. It’s unique. People hear about it and it makes sense, so they try it, and when they do? It delivers. The new way is so good that it makes the old way look like junk.

But most new products don’t click. They flop.

So what’s the difference? What makes one new product a runaway success? What makes another fail?

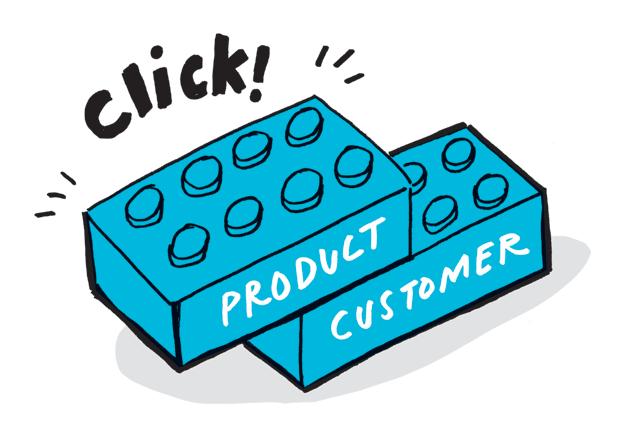

Of course, there are a zillion factors. Team. Management. Technology. Execution. Design. Pricing. Timing. Luck. But all of these lead (or don’t) to one decisive question: Does it click?

This is the most important thing. The product and the customer must fit together, like two LEGO bricks.

If a product solves an important problem, stands out from the competition, and makes sense to people, it clicks. If not, it’s a dud. That’s it. Making it click is the fundamental key to success.

I know, this is pretty obvious stuff. But even though it’s the most important thing for any big project . . . it’s kind of easy to lose track of the click. We get wrapped up in the technology and execution and design and pricing and all the other important factors—and in the noise, we forget the paramount question:

When we offer this to people, will they want it?

All too often, we bet on the wrong strategy, and our products don’t click, they flop.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. There is a better way. And that’s what this book is all about.

This book is based on firsthand experience with some of the world’s most successful startups.

Early in our careers, my coauthor, John Zeratsky (JZ), and I had the good fortune to build several successful products. JZ joined a startup that was acquired by Google, then became a leader on Google Ads and YouTube. I worked on Gmail and cofounded Google Meet. We know what it’s like to start a big project and see it through till it clicks with customers. But what’s special (and unusual) is what happened in the second half of our careers.

Since 2012, JZ and I have worked directly with early-stage startups, first as partners at Google Ventures and now as cofounders with Eli Blee-Goldman of the venture fund Character Capital. Most investors give advice, but when I say “work directly,” I mean precisely that. For more than a decade, dozens of times each year, we’ve cleared our calendars—for a day, a week, or even a month at a time—to work side by side with founders and their teams in “sprints” to kick off their most ambitious projects.

JZ and I have run more than three hundred of these sprints. Along the way, we had a hand in smash hits like Flatiron Health, Gusto, One Medical, Blue Bottle Coffee, and Slack, among many others. Today we work alongside startups at the forefront of artificial intelligence. It’s a unique opportunity and a ton of fun. I mean, who else in the world gets to join founders in these crucial moments, time and time again? We’re like two kids with FastPasses at Disneyland.

But I have to admit that our motivation for working this way is partly selfish: our money is on the line. We run sprints with founders because it’s the best way to make their products click with customers, help their companies succeed, and lead to a positive return on our investment. These sprints are serious business.

The first type of sprint I created was the Design Sprint, which I developed based on methods I used at Gmail and Google Meet. JZ and I refined the Design Sprint at Google Ventures, then wrote a book about it called Sprint. The book became a bestseller, people around the world adopted the Design Sprint, and to this day, we hear stories about teams running these sprints at companies like Airbnb, Amazon, Apple, OpenAI, Tesla, and even LEGO. The success of the Design Sprint surprised us. I guess that’s an understatement—we were blown away.

But after starting Character Capital, we noticed something was missing. Design Sprints are awesome for solving problems and testing ideas, but in the early days of a new company, founders need a different

kind of help. They need a plan for standing out from the competition. And they need to choose a direction and get started—as fast as possible.

JZ and I wanted to help. We looked for patterns in the most successful projects we’ve seen firsthand as designers and investors. We realized these patterns could help any kind of big new project—not just startups. So we reverse-engineered those patterns into a new sprint format that we call the Foundation Sprint. We call it the Foundation Sprint because it creates the foundation on which a team can build a product that clicks.

Today, the Foundation Sprint is the tool we use most often with the companies in our portfolio. In this book, we’ll give you the secret recipe.

This book is about unlocking the power of the fundamentals. Teams who build winning products share some fundamental traits. They know their customers—and what problem they can solve for them. They know which approach to take—and why it’s superior to the alternatives. They know what they’re up against—and how to radically differentiate from the competition.

This combination of customer, approach, and differentiation forms what JZ and I call a Founding Hypothesis. The Founding Hypothesis distills a team’s strategy into one Mad Libs-style sentence:

If we help solve with they will choose it over because our solution is customer problem approach competitors differentiation

The Founding Hypothesis is simple, but that’s exactly what makes it so powerful. Products click when they make a compelling promise—and that promise must be simple, or customers won’t pay attention.

Every winning team JZ and I worked with made one of these simple, compelling promises. For example, when I worked on Gmail in the 2000s, our promise to customers was: “We’ll solve your overflowing inbox problems better than Outlook, Hotmail, and Yahoo because we offer more storage and great search.”

If we help solve with they will choose it over because our solution is tech enthusiasts overflowing inboxes Google data center power Outlook, Hotmail, Yahoo high-capacity & searchable

In our book Sprint, we profiled several startups who built products that clicked. Again, looking back, it’s easy to identify the simple promise each one made to customers.

Here’s how the Founding Hypothesis could have looked for Blue Bottle Coffee, a startup we worked with in 2012:

Founding Hypothesis

If we help solve with they will choose it over because our solution is coffee drinkers need for a break

artisan coffee & chic cafés

Starbucks

delicious & beautiful

For Flatiron Health, a startup we worked with in 2014:

Founding Hypothesis

If we help solve with they will choose it over because our solution is cancer care clinics

finding the best therapy

AI for clinical trials

manual search for trials

fast & comprehensive

And for Slack, a startup we worked with in 2015:

If we help solve with they will choose it over because our solution is teams communication searchable chat email fun & boosts teamwork

Each of these startups turned into a valuable business, and each was eventually acquired for hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars. In each case, they made a simple promise that clicked. Unfortunately, finding the right simple promise is not easy.

When I first began working with startups, I was embarrassed to ask founders basic questions like “Who are your competitors?” or “How will you differentiate?” because I didn’t want to waste their time or appear naive.

But once I worked up the courage, I learned a surprising thing: If I asked three cofounders to write down their startup’s target customer, I got three different answers. If I asked a team what differentiated their product from the competition, I got a sixty-minute debate. The obvious stuff is not always so obvious.

And even if a team does have clarity about their promise, there is no guarantee that customers will care. For every Gmail, thousands of new projects at big companies fizzle. For every Blue Bottle Coffee, Flatiron Health, or Slack, millions of startups fail. Most teams can’t find the right promise. They don’t build what people want. There are just so many ways to get it wrong.

Why do so few teams get their foundation right?

Well, we’re only human. Cognitive biases trip us up. Group dynamics are hard to navigate. People fall in love with their first ideas. Leaders don’t know what’s true vision and what’s false assumption. They don’t know how to run fast experiments. They don’t know how to get the whole team committed and confident.

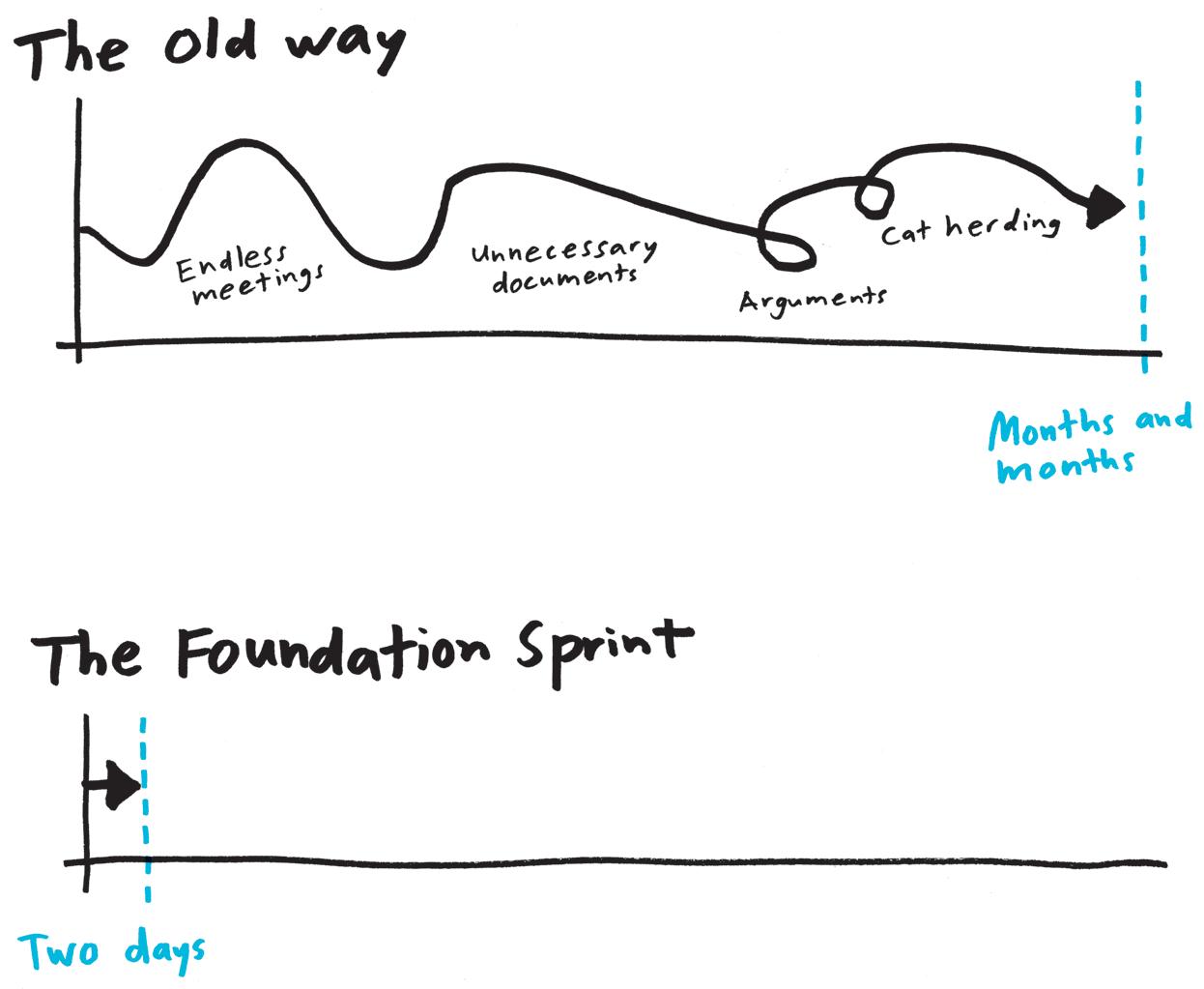

It doesn’t help that the world’s most popular approach to kicking off new projects is . . . chaos. Meet, and meet, and meet. Talk, and talk, and talk. Churn out slide decks, documents, and spreadsheets that no one actually reads. Outlast your opponents in a political cage match. Finally, rely on a hunch and commit to years of work.

That’s the old way. And it is bonkers. Doing things the old way, it can take six months or more to develop a strategy. The old way is like assembling IKEA furniture by tossing parts, an Allen wrench, and a dozen squirrels into a broom closet, then hoping for the best.

There is a new way. You don’t have to rely on luck: JZ and I have built, tested, and proven a system that will allow you to dodge cognitive biases, streamline group dynamics, make rapid decisions, and set up fast experiments. You can use the system to figure out what clicks.

This book compresses six months into ten hours.

Inside, JZ and I will show you how to create clarity on the fundamentals in just ten hours spread across two days.

The Foundation Sprint works like this:

On day one, you’ll focus on basics and differentiation. You’ll identify the problem you’re solving and form a plan to set your solution far apart from the competition.

On day two, you’ll find the right approach for your project. You’ll generate options, put them through rapid and rigorous evaluation, and choose one to try first.

At the end, you’ll have your own Founding Hypothesis.