‘A brilliant, groundbreaking book that will shift your perspective and expand your mind. Everyone should read it’

Malachy Clerkin, Irish Times Sports Books of the Year

‘A brilliant, groundbreaking book that will shift your perspective and expand your mind. Everyone should read it’

Malachy Clerkin, Irish Times Sports Books of the Year

‘A book that will very soon be acknowledged as a classic of Irish sports writing’ Ciarán Murphy

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Sandycove 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Eimear Ryan, 2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d0 2 yh68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 978–1–844–88533–6

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

Do mo thuismitheoirí, Ber & Séamus, le grá agus buíochas

Imagine us in a shady stand on a hot summer’s day, the whole family sat in a row: my father, Séamus; my mother, Bernadette; my older siblings, Conor and Eileen; and me. The cross-hatch of a Dairy Milk broken, the awkward sharing of eight squares among five. Imagine a few bottles of Scór cola; it was the nineties, after all.

We passed the programme back and forth as we waited for the game to start, and I often kept reading it even after the ball was thrown in. I was a bookish as well as a sporty child, better at reading text than the flow of the game unfolding below us. The programme flopped open to its stapled middle pages: the two teamsheets. Tipp and Cork, maybe, or Tipp and Clare. The Declan Ryan, Johnny Leahy, Skippy Cleary heyday. Then, a name I didn’t recognize.

‘Who’s AN Other, Dad?’

My dad would get antsy at games; still does. Pitched forward, hands on his knees, as if barely able to hold himself back from the fray. He had played senior for Tipp in the luckless seventies, alongside icons like Eamon O’Shea, and was still deeply involved at club level; our summers consisted of traipsing along after him to an endless succession of matches and training sessions, our own hurleys in hand.

Engrossed in the game, he would’ve been startled at the interruption, but Dad is a teacher and a coach at heart.

‘That means they’re not sure who’s starting in that position when they make the programme. The usual fella could be injured, maybe, so they might only decide on the day.’

AN Other. A placeholder from a time when managers were transparent about their lineups and their injury worries – a time before announcing your starting fifteen became a way to lure the opposing manager into a false assumption about your formation. Its use has fallen away, but the name – anonymous, other – has always stuck with me, in part because it captures something of how I’ve felt in the GAA for much of my life. Born into it, but not of it.

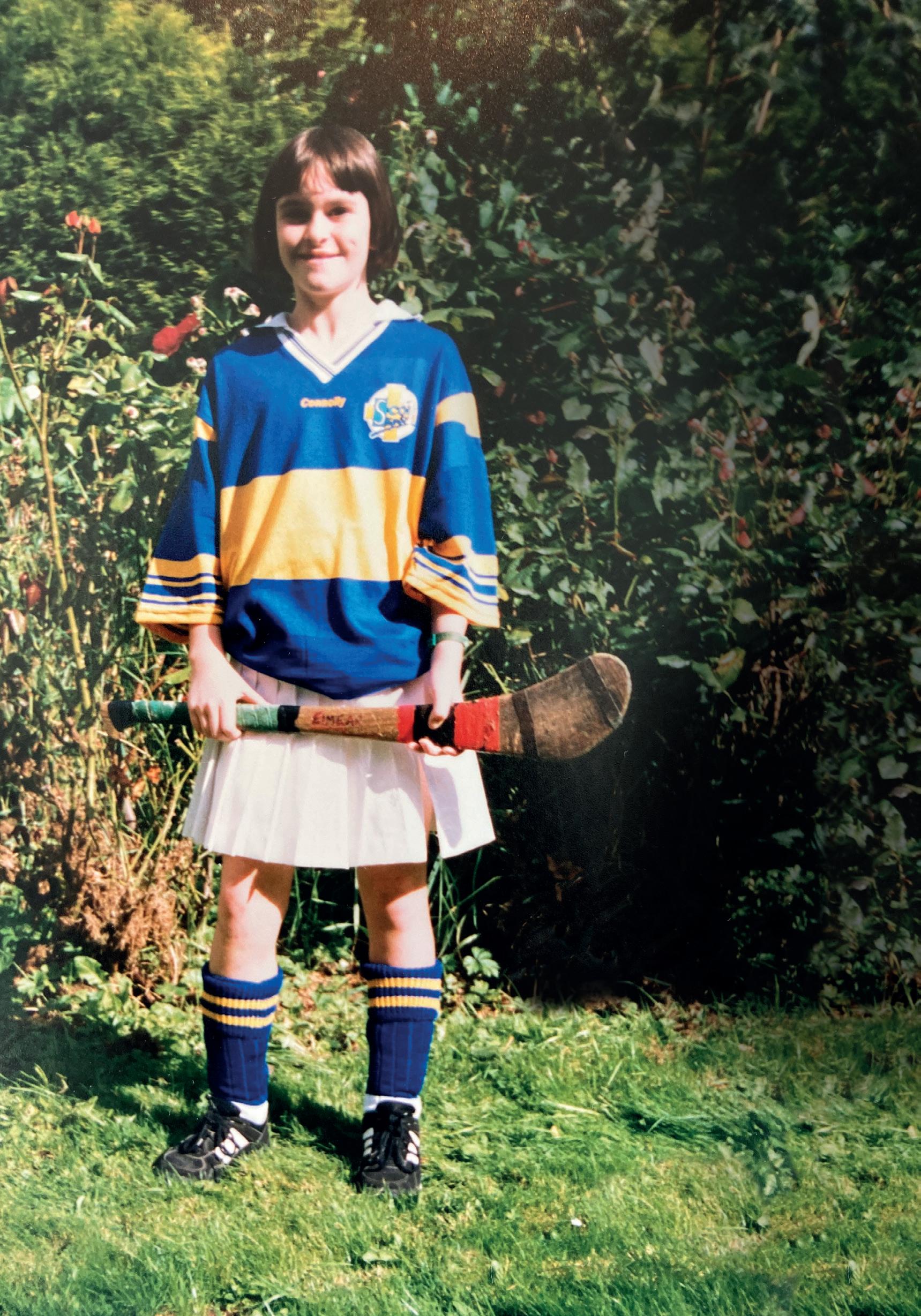

There was a strange androgyny to my childhood, obsessively pursuing a sport that was, back in the eighties and early nineties, very much a man’s game. The summer I was three or four, I would answer only to ‘Nicky’, after Tipperary legend Nicky English. Around the time of my Holy Communion, I received a gift of a framed print of Seamus Redmond’s famous poem ‘The Hurler’s Prayer’, which I immediately added to my bedtime prayer rotation. The speaker of the poem appeals to God to give him all the attributes of the ideal hurler. It begins: Grant me, O Lord, a hurler’s skill, / with strength of arm and speed of limb. As a child, I loved its rhyming couplets and accumulating rhythm. Even now it moves me, especially that daring turn in line 9 where the focus shifts abruptly to the afterlife: When the final whistle for me is blown, / and I stand at last at God’s judgement throne, / may the great referee when he calls my name / say ‘You hurled like a man, you played the game.’ This is really how GAA people talk: everything in life – even death – is a hurling metaphor.

As a kid I used to stumble uncertainly over that last line, and another in the middle where the speaker wishes for his on-field actions to be ‘manly’. I knew how to hurl, but the poem made me feel that manliness was the ultimate quality of a hurler, and I wasn’t even sure what that meant. What did I know of hurling ‘like a man’? What was the great referee going to say to me at the pearly gates? ‘Sorry, you hurled like a girl; I can’t let you in’?

The sport I play is called camogie. When I am abroad I describe it thus: it’s a ball-and-stick game, a bit like hockey, a bit like lacrosse. Have you heard of hurling? I will sometimes ask. It’s, like, the female version of that. No, it’s basically the same sport. Yeah, I know it doesn’t make sense.

As former Camogie Association president Joan O’Flynn memorably pointed out in the 2018 RTÉ documentary The Game, ‘The verb is “to hurl”.’ In my mind I always think of the sport I play as hurling, even though the Camogie Association has been around almost as long as the Gaelic Athletic Association. To be a girl within Gaelic games is to grow up with a sort of dual consciousness. We are hurlers but we are also women, and have to navigate a sporting landscape that sometimes treats those identities as a contradiction. The Camogie Association is culturally linked to the GAA , but it is organizationally separate. Born in 1986, I grew up in a society that treated camogie as a secondary sport.

As players, we can be proud of our exploits and at the same time have completely internalized society’s view of us. For example, if someone says to me, ‘Tipp are playing

on Sunday,’ I will assume they are talking about the hurlers. My subconscious defaults to the men; I betray my own gender.

In this book, I have tried to be true to the ways that I think and the language that I use. I often use ‘GAA’ to signify not the Gaelic Athletic Association – the organization formed in 1884 to promote Gaelic games for boys and men only – but the whole cultural complex of Gaelic games. It is a culture I love, despite its sidelining of girls and women. And it is a culture that needs to change, as I hope this book will show.

When I was in primary school, I told my mother that my ambition was to play senior camogie for Tipperary and senior hurling for my club, Moneygall. I remember the delight in her response – the things kids come out with! – but also the caution, the worry. She let me down gently, explaining that I would most likely not have the physique to compete with men when I was older. Looking back now, I wonder if it was the first time she had to manage my expectations in relation to my gender.

I doubt that I paid much attention. I was as good as or better than a lot of the boys I played against. This has always formed a core part of my confidence as a player. Adolescence came and bodies changed, opening a gulf in size and strength. But my experience of hurling allows me to see that there’s no mystique to men’s sport.

By the time I was ten, I was equally comfortable hitting the ball on my right and left side. This was unusual at underage levels, where a key tactic in marking was to ‘force them on to their bad side’. It was my dad’s doing, really: seeing

that I was striking well on my left, he told me to practise on my right until it was just as good.

For a week, it was horribly frustrating, out at the gable end, throwing it up and missing it. That I was starting from square one was unusual: most right-handed hurlers learn to hit on their right side first, because you don’t have to bring your hurley hand across your body. The right-hand swing is freer and more open for a right-handed hurler, just as the forehand is an easier tennis shot than the backhand. But I had grown comfortable on the more constricted left-hand side – the backhand – and didn’t know what to do with the openness of the right. My first attempts were big loopy swings. Gradually, I began connecting more often than not. I had no control, no accuracy. But it’s like anything: if you have enough time and enough patience to endure the frustration and discomfort of the initial failure, you will get there. And who has more time than a ten-year-old in rural Ireland?

I was lucky to have multiple outlets for my sporting passion: our burgeoning camogie club, founded in 1995; school, where boys and girls competed against each other on the pitch most lunchtimes; and the local boys’ hurling team. At the time, organized camogie began at under-12, and so under-10 hurling was where I got my first proper competitive games. There were a handful of us girls deemed handy enough for hurling: myself, my cousins Mary Ryan and Maria Jones, and my friend and classmate Julie Kirwan.

In a small rural village where numbers were low, we were useful additions to the boys’ team. I loved playing with the lads, and kept playing right through under-14 level, and

even for an awkward, ill-advised year at under-16, togging out surreptitiously in the loo. Being good at hurling was like a secret pass into the mysterious and altogether more interesting world of boys, a way of overriding their preteen disdain for girls. They would say anything around me because I did not count as a girl. I once overheard a teammate remark that I was ‘some man’, and didn’t mind, because I knew he meant it as a compliment. While the majority of my male teammates were nearly always supportive, the boys on opposing teams were sometimes unsettled by the presence of girls on their pitch. You would see it in their gait as they came over to mark you, noticing the ponytail sticking out from under your helmet. First they’d be defensive and try to laugh it o , calling to their teammates: Can you believe I’m marking a girl? Once the game began and they realized you could play, their alarm would grow. Your prowess became an a ront to them. I realized that for these boys, to have a girl get the better of them was the worst thing that could happen to them on the pitch.

They hurled like men. I’ve heard this phrase in one form or another since I was a child. I don’t know if it was in general use before the publication of ‘The Hurler’s Prayer’ in the 1960s, but given the sport’s preoccupation with masculinity, I can only assume that it was. During the winter of 1996–7, when I had just turned ten, every day after school I alternated between two VHS tapes that I had recorded o the TV: the 1996 All-Ireland hurling final between Wexford and Limerick, and Home Alone 2: Lost In New York. The latter began a lifelong obsession with NYC ;

the former was probably the first televised hurling match that I was truly captivated by – perhaps because I wasn’t supporting either team, and could more easily grasp the beauty and symmetry and pathos of the game. I was starting to relate what I saw on the telly to what I did myself on the school pitch or at home out the back. One of the Wexford players performed an outrageous piece of business I’d never seen before: on a solo run, having caught the sliotar twice, he handpassed it on to the ground in front of himself and picked it up again, thus resetting the catch count. I practised this move endlessly on our front lawn, but never had the nerve to try it in real life.

The Wexford players – many of them mustachioed – were dear to me. Some – Billy Byrne and George O’ Connor – seemed old, though they were the same age then as I am now. ‘This is our day in the sun, we’re not going to not walk the full round of the pitch,’ said Liam Gri n, Wexford’s manager that year, motivating his players ahead of All-Ireland final day. ‘We’re walking with our heads up . . . Stand up like soldiers, this is a man’s game, stand up there, can we stand up like men in front of the President, can we stand up and show a bit of respect and then get out and put the lights on to green . . . and let’s go.’

A man’s game. You hear this sort of thing even now, more often than you’d think, from pundits and commentators; some of my favourite hurling minds, in fact. An emotional Michael Duignan tweet, after a promising 2018 performance from O aly: ‘They hurled like men.’ Davy Fitzgerald on RTÉ ’s Morning Ireland in 2021, discussing the ins and outs of the advantage rule: ‘It’s a manly game.’

(Speaking on the same issue, Brendan Cummins did not bring gender into it: ‘It’s a free-flowing game.’)

This is not at all to say that Gri n, Duignan and Fitzgerald are sexist. By now, I know what they’re getting at. They’re invoking the traits of positive masculinity; to hurl like a man means to hurl with strength, courage, integrity, honesty, resilience. But this language excludes women, and seems to suggest (intentionally or not) that camogie players can’t access such qualities. In popular discourse we hurl like men, but throw like a girl, gossip like women, cry like a little girl. You do not hear of people aspiring to hurl like women.

Fitzgerald recently coached the Cork camogie team, and I fondly remember him as a guest coach with Tipperary camogie in the early noughts: challenging, electrifying sessions. While managing the Wexford hurlers, Fitzgerald brought in Mags Darcy, the All-Ireland winning camogie goalie, as a goalkeeping coach. ‘There’s no gender with Davy,’ Darcy remarked at the time, meaning her being a woman was not seen as an impediment for the job. This is the arena of sport. Maleness is elevated, aspirational; femaleness is overlooked, or forgiven.

So where does that leave us camogie players? Do we simply need to magnify our masculine streaks, much like men talk about exploring their feminine sides? Or are the qualities we’re alluding to here – passion, aggression, courage – actually universal and gender-neutral? One might argue that traditionally feminine traits – gentleness, sensitivity, passivity – are of little use on the hurling field. But others, like cooperation, communication and empathy, are essential to being part of a team. Hurling is soft as well

as hard, graceful as well as furious. It is as much dance as it is fight.

‘You’re the best girl hurler I ever met,’ a boy told me the summer I went to the Kerry Gaeltacht. I was twelve at the time and had a hopeless crush on him; I thought I could impress him with my hurling prowess. I was not yet aware of the unspoken rule, that I was supposed to let him impress me and not the other way around. But at night, I turned the phrase best girl hurler over and over in my mind, as if it was a prize.

When I remember my grandfather, I think of his paraphernalia: the trilby hat that was worn summer and winter; the pipe, which he reluctantly gave up in his seventies; the walking stick; the rattling typewriter; the Pioneer pin on his lapel.

I do something similar with Julia, my grandmother on my mother’s side. Whenever I sit in the mid-century armchair I inherited from her, or change the date on her perpetual calendar, I think of her. I don’t own any of my grandfather’s personal e ects. But I do have a copy of each of his books, and his memory card watches over me from the noticeboard above my desk.

When a great character exits, we’re left with the props.

Séamus Ó Riain (1916–2007), my grandfather, was a teacher, sportsperson, writer, administrator, Gaeilgeoir, gardener and historian. He played Junior hurling and football for Tipperary and was an accomplished track and field athlete, specializing in the long jump and races of 220 and 440 yards, known as the two-twenty and the four-forty. In my family, he’s our origin story – the GAA lightning rod from which we all caught a spark. He is still somehow the notional head of the family. His anniversary Mass has eclipsed Christmas as the annual family occasion at which I will reliably catch up with most of my aunts, uncles and cousins.

It may seem strange to begin a book about being a woman in sport with a portrait of a patriarch, but it couldn’t have begun any other way.

He served as President of the GAA from 1967 to 1970. During his tenure, Tipperary lost the All-Ireland hurling final twice. Sometimes I’ll catch him in archive footage on Reeling in the Years or Up for the Match, dapper in a threepiece suit, handing over the Liam MacCarthy Cup with a tight smile.

We are lucky to have the footage. He also featured in an episode of I Live Here, an RTÉ documentary series from the late eighties. I was too young at the time to remember it being filmed, but throughout my childhood the video was a source of wonder to me. It’s very surreal to see the familiar reframed for a wider audience. There’s Nana and Grandad strolling up their well-tended garden, chatting. There’s my dad in his Buddy Holly glasses. My mam in her beloved classroom. My older brother Conor, about eight or nine at the time, out hurling on the school pitch.

After my grandfather died, my cousin Eamonn transferred the episode from VHS on to DVD for all ten branches of the family. Séamus would have approved. He was the village’s amateur historian, and whenever Americans came to Moneygall looking for their roots they were sent to his house on Main Street. He died in January 2007, about ten months before the Irish roots of Barack Obama, then a presidential candidate, were traced to Moneygall. Séamus would have got an almighty kick out of that. ‘Boys, oh boys,’ he would have said, his ready phrase for almost any situation – an expression of pathos, surprise, wonder,