Acclaim

for The Sisters Grimm trilogy:

‘Vividly drawn, evocative and complex, The Sisters Grimm is both absorbing and beautiful – a great achievement.’

BRIDGET COLLINS

‘One of those rare finds: a vivid and fully-realised act of the imagination, written with the page-turning immediacy of the here and now, but overflowing with the wonder of the stories of old.’

ROBERT DINSDALE

‘Van Praag spins a compelling, intensely poetic narrative of empowerment and self-realisation.’

GUARDIAN

‘An entertaining and clever examination of folklore, female empowerment, and the system that attempts to keep women in check.’

SciFiNOW

‘A darkly beguiling delight that’s perfect for fans of rich and imaginative fantasy books akin to Erin Morgenstern and Neil Gaiman.’

CULTUREFLY

‘A very grown up fairy-tale with more than a nod to Angela Carter and Philip Pullman . . . textured and complex . . . genuinely thrilling and emotional . . . it’s never less than spellbinding.’

STARBURST

‘Readers will be drawn to these well-developed characters and their lush world.’

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

‘Van Praag’s character-driven, lush novel . . . is a story determined to exalt the powers of the feminine and of sisterhood.’

LIBRARY JOURNAL

Also by Menna van Praag

Men, Money and Chocolate

The House at the End of Hope Street

The Dress Shop of Dreams

The Witches of Cambridge

The Lost Art of Letter Writing

The Patron Saint of Lost Souls

The Sisters Grimm trilogy

The Sisters Grimm Night of Demons and Saints Child of Earth and Sky

Child of Earth and Sky

Menna van Praag

PENGUIN BOOK S

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2023 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers Penguin paperback edition published 2024

Copyright © Menna van Praag 2023

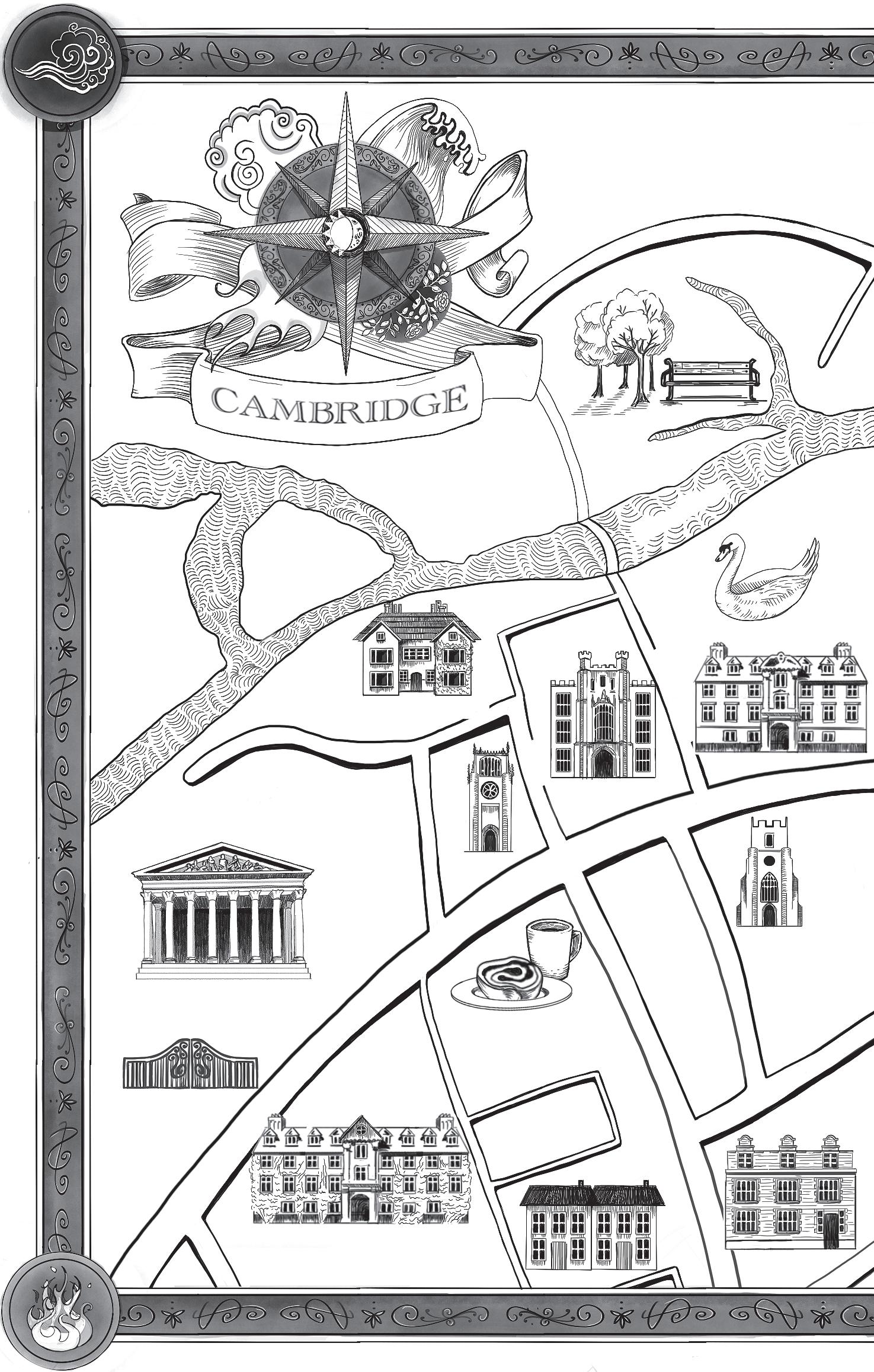

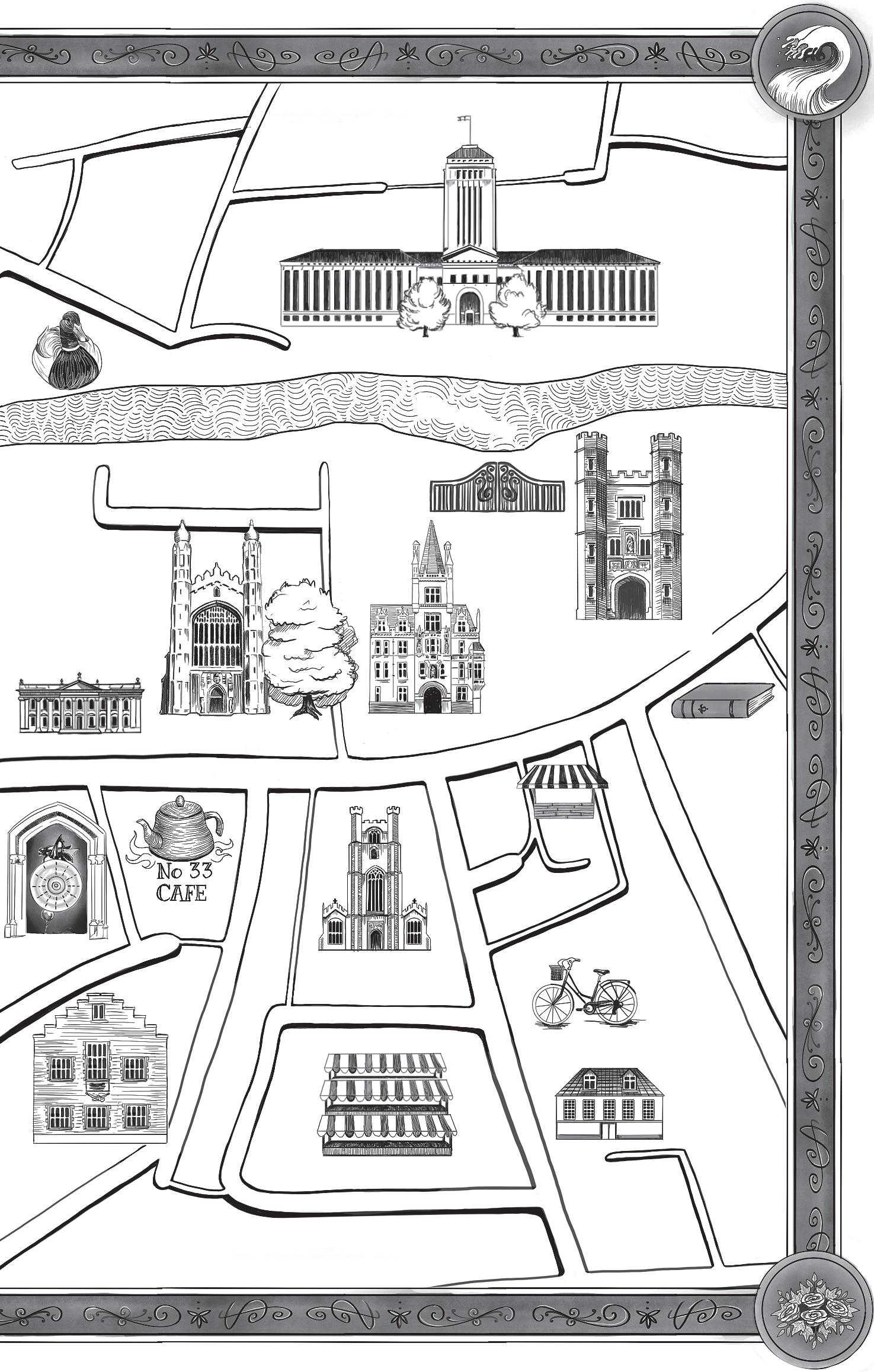

Illustrations on pp. 41 and 73 copyright © Alastair Meikle Map copyright © Naz Ekin Yilmaz

Menna van Praag has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs 9781804991138

Typeset in 10.08/14.4pt Berling LT Std by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Alastair

With great love and deepest gratitude for the splendid gift of your magnificent illustrations for this trilogy.

I’ll be forever grateful to the serendipity that caused our paths to cross again!

Hotel Clamart

Pembroke Street

Botolph Lane

Fitzbillies

Fitzwilliam Hotel

The Fitzwilliam Museum

Market Hill

King’s Parade Trinity Street

St John’s College Heffers

King’s College

Prologue

It happened three years ago, but Goldie can still close her eyes and relive that night as if it were happening now. It had been a perfectly ordinary evening at first, no whisper on the breeze to indicate what was to come. The unwavering moon hung low in the star-speckled sky, seeming to graze the tops of the towering birch trees, and the rivers that twisted through the forests of Everwhere lay calm.

As usual, the sisters were scattered around in their favourite spots: Goldie perched in the low branches of her treasured oak tree in the glade teaching sisters of earth how to coax fresh green shoots from the ground; Scarlet theatrically setting alight fallen branches beside the lake, to the awed gasps of sisters of fire; and Liyana stood in the middle of the lake, showing sisters of water how to conjure waves and whirlpools from the depths.

They all heard the scream.

For a second, the shock of the scream pinned Goldie to the tree, but then she leapt down and ran, barefoot, across moss and stone, a dozen women and girls following in her wake. Fear rippled along the stream of sisters as they fled from the glade towards the source of the sound. For so long now, Everwhere had been a place of safety, a place to flourish, to find inspiration, courage and spirit. It was a long time since soldiers had roamed the forests; a long time since anyone had any reason to be afraid.

When Goldie reached the edge of the lake, the single scream had spread into a cacophony of chaos: arms waving,

water splashing, a hundred wails and shrieks and howls piercing the air. And, at the centre of it all, two women were caught in a relentless rush of water, a frenzied vortex sucking everything into its core.

It took another second for Goldie to realize that one woman was Liyana, the other Scarlet. Her two beloved sisters: one drowning, the other trying to save her. Goldie had already plunged into the water by the time this realization hit, and she swam all the stronger for it, with every aching limb and gasping breath, trying to reach them.

But she was too late.

By the time Goldie reached the centre of the lake it was already calm, having swallowed Liyana into its depths and left Scarlet floating on its surface. Other sisters were already dragging Scarlet to the bank and Goldie followed. She administered the kiss of life – though she barely had breath left in her own body – and managed, with the assistance of her own life-giving touch, to bring Scarlet back from the brink.

As soon as she’d opened her eyes and coughed up the water from her lungs, Scarlet had asked for Liyana. It was Goldie who’d told her. Together they’d held each other and wept, though Scarlet didn’t speak another word. Not that night, nor for a long time after.

It took them all a long time to accept what had happened, to understand that Liyana wasn’t coming back. At least, not to Earth. They could, of course, still talk to her every night in Everwhere. But it wasn’t the same. They couldn’t see her, they couldn’t hug her; and Liyana couldn’t write and illustrate her stories, though she still told them. And for Kumiko – who’d adored Liyana just as deeply as her sisters

did, yet, with no Grimm blood running through her veins, couldn’t visit her lover in Everwhere – the loss was greatest of all.

If Kumiko was struck down by the deepest sorrow, Scarlet suffered the greatest guilt. She believed that she should’ve been able to save her sister and, no matter what anyone said, she couldn’t let it go. Less than a year later, she fled Cambridge for lands unknown. And, despite every effort, Goldie had failed to locate her sister. And because Scarlet never returned to Everwhere, her disappearance for Goldie was, in some ways, a greater loss than Liyana’s death.

3.33 a.m. – the Sisters Grimm

Every night, despite her overwhelming busy daily life running a women’s shelter, Goldie spends at least an hour in Everwhere. It was her promise – to Leo, her sisters and herself – that she’d support and grow the community of Sisters Grimm around the world, to strengthen and empower them, to inspire and motivate them, for their own betterment and the betterment of the oppressed and marginalized everywhere.

Tonight, Goldie sits cross-legged on a rotten tree stump. Before her, a large semicircle of women and girls sit similarly cross-legged on the mossy forest floor. No one speaks; they all watch Goldie, waiting.

‘Many of you have been here before, some of you are quite new, and a few of you have never been.’ Goldie’s voice echoes round the circle of oak trees – an audio effect assisted by her two dead sisters. And, as she speaks, the dead tree stump begins to show signs of life: the wood slowly shifting

from grey to brown, the flaking bark softening, the new shoots of sapling branches twisting between Goldie’s legs, wet bright green leaves unfurling from the fresh twigs. ‘But the reason you’re here, as I always say, is to find your strength, your power, your ability to be and do whatever it is you wish. To be at the mercy of nothing and no one, to triumph over all obstacles, especially your own doubts.’

Applause rises into the air and Goldie takes a breath. The number of Sisters Grimm gathering in Everwhere has been increasing with each passing year; sisters have been spreading the word, for they know there’s strength in numbers. Lately, every month or so Goldie must uproot the trees and expand the circle. Tonight, she thinks, the crowd might even exceed five hundred.

As the cheer reverberates through the glade, Goldie gazes down at Luna, who sits cross-legged at her feet, grinning wildly and cheering louder than anyone. Goldie smiles down at her daughter who has, for as long as Goldie can remember, had an astonishing knack of one minute being a little girl and the next an adult. She’s been bringing Luna to Everwhere every night (restricting it to Saturday nights once school started) since she was born. In the absence of Leo’s physical presence, she’d reasoned that this place was the closest possible experience to being with him. Here, at least, even if she couldn’t feel his touch or hear his voice, Luna could at least sense her father’s spirit. And, sure enough, Luna had grown to love Everwhere more than any place on Earth. Here she’d learned to walk on moss and stone; she’d learned to set fire to dry sticks with her fingertips, to spread those fires with well-aimed gusts of wind and put them out with focused bursts of rain. Which was how

Goldie discovered that her daughter could control not only one element but them all.

‘Tonight, as ever, we’re going to practise a series of exercises, both physical and mental, to strengthen ourselves,’ Goldie continues. ‘So we might better protect the weak and vulnerable on Earth, which must always begin with protecting ourselves.’

A murmur of agreement runs through the crowd, peppered with nods, clapping and the occasional cheer. As usual, Luna does all three. On Earth, Luna is as moody and mercurial as any child, but in Everwhere her adoration of her mother is undiluted and her admiration absolute.

‘It’s time to get together in small groups – no less than ten, no more than twenty – of sisters who share the same elemental force. Those of you more expert in your skills can support those less experienced,’ Goldie says. ‘The space will be held, as usual, by myself and my sisters, Liyana and Bea. So no one need hold back their powers for fear of causing harm. On Earth you’ve been taught to make yourself small, to fit in, to smile, to be pleasing, to swallow your words, to shrink your emotions. In Everwhere you can practise doing exactly the opposite. And we will keep you safe, so let it all out: rage, fear, fury. Let it all out – let yourself go!’

At Goldie’s feet, Luna whoops and cheers, sparks flying from her fingertips, fresh ivy springing up at her feet, a wild wind whipping through her hair, faint cracks of thunder and forks of lightning in the sky directly above her. The first Grimm girl to have command of all the elements with everincreasing, perhaps infinite, power.

Goldie grins at her daughter, internally torn between pride and fear. She wishes, as she does every night, that Leo

was here to witness his daughter’s brilliance, but she tries her best to be both parents at once. All this at only nine years old, she thinks now. What will you be at nineteen?

Chapter One

3.33 a.m. – Luna

What you’ve heard is true. The gates. The moon. The devil. For years I thought Ma was telling stories, making it all up, like the fairy tales she whispered to me at night, the ones written by my dead aunt Liyana. I still sit in her lap sometimes, pressed against her warmth while I wait for her words. I always wanted those stories; I loved them because they connected us.

I am a Sister Grimm, Ma would tell me. And so are you. But lately something’s changed. I’ve changed; I’m different. Now I don’t snuggle with Ma so much because her stories aren’t my stories anymore. At least . . . I realize now that I’m not just a Grimm; not just a sister but a soldier too. Like my dead father. Half a sister, half a soldier, born from a daughter of earth and a fallen star. At first, I didn’t think it mattered, but then I started to notice how Ma seemed a little scared of me. Or for me – I’m never sure which. She pretends she isn’t, but I know she is. I see the strange looks she gives me when she thinks I’m not looking.

I just wish I knew why.

7.56 a.m. – Goldie

‘Luna, come on, we’ll be late.’ Goldie watches her daughter sitting at the kitchen table, eyes flitting from Luna’s face to the untouched bowl of porridge.

‘O-kay,’ Luna says, scribbling in her notebook without looking up. Goldie’s fingers twitch with the temptation to simply feed the last few spoonfuls into Luna’s half-open mouth. But she holds back.

‘Lu-Lu, please. You need to eat.’ The thought of Luna hurtling around the playground on an empty stomach pushes Goldie’s hand forward, but Luna’s scowl stops her. ‘What are you writing?’

Luna regards her mother suspiciously. ‘A story.’

‘Oh?’ Goldie raises a curious eyebrow, trying to gauge the right balance between interest and respectful distance. ‘Is it a story Aunt Liyana told you?’

Luna nods, but says nothing.

Goldie waits.

At last, Luna glances up. And, as ever when Goldie meets her daughter’s eye, she’s pinioned yet again by loss and longing for the man who looked so much like Luna. For her daughter was born in the image of Leo: blonde hair, broad smile, eyes a dozen different shades of green. Often, Goldie is so overcome by a sudden rush of sorrow at the sight of Luna that she has to turn away, force herself to focus on something else. Often, when she hugs her daughter she must do it with her eyes closed.

‘Shall I tell you what it’s about?’ Luna asks, then absently – to Goldie’s great relief – takes a spoonful of porridge.

Goldie tempers her grin. ‘Yes, please.’

Luna looks thoughtful, as she always does when discussing her stories. It makes her, Goldie thinks, look like a wise old crone. It pleases Goldie deeply that Luna has a love of stories, that she spends so much time chatting with Liyana

in Everwhere, taking dictation and often collaborating with her aunt to create tales together. That her daughter is so connected with her sister brings Goldie great joy, softening the edges of her grief.

‘Perhaps one day you’ll write a book with your aunt and publish it,’ Goldie suggests.

Luna considers this, chewing the end of her pen. ‘I like that idea,’ she muses. ‘But can dead people publish books?’

‘Oh, yes,’ says Goldie, happy to have pleased her daughter. Without thinking, she takes a spoonful of Luna’s porridge and, before she knows it, she’s taken another. She’s not hungry, has already eaten a breakfast of her own, but food smothers the constant sadness threatening to burst forth, while soothing her rising anxiety. ‘Plenty of authors are dead.’

Luna brightens. ‘Really? I didn’t know that. I’ve never met any other dead writers except Aunt Ana.’

Goldie laughs. ‘No, that’s not what I meant . . . I – anyway, weren’t you about to tell me what the story’s about?’

Luna nibbles on her pen again. ‘It’s about . . . you.’

‘Oh,’ Goldie says, a little unnerved. ‘Really. Well, um, what happens to me in the story?’

Luna’s eyes widen. ‘I can’t tell you that. Aunt Ana told me that writers should never discuss their works in progress. It dilutes the process. Didn’t you know that?’

‘No,’ Goldie admits, charmed by Luna’s phrasing. She never fails to be surprised when her daughter suddenly transforms from a girl into an adult. A few months ago, the school had informed Goldie that Luna is a prodigy, not that she was surprised. You should see what she can do in Everwhere, she’d thought. ‘I didn’t.’

‘Well.’ Luna folds her arms. ‘You should.’

‘All right.’ Goldie nods. ‘Noted. Now, will you please at least have one more mouthful of porridge?’

‘Okay, okay,’ says Luna, ignoring the bowl and returning to her notebook. As she writes, Luna absently reaches out with her free hand to rub the leaves of the juniper bonsai tree in the middle of the table. Instantly, the little tree’s leaves perk up like a cat’s ears, then begin to turn a lighter shade of green. Goldie watches, marvelling at her daughter’s power. She’s never been able to do anything like this, especially not so effortlessly. To elicit growth and transformation takes focus and concentration. Effort. Yet Luna does so much without even being aware of it.

Goldie glances at the clock. ‘Right, let’s go.’ She stands, lifting the bowl and polishing off the remaining porridge on her way to the kitchen. Luna, head down over her notebook, doesn’t move.

‘Luna, please.’

Still her daughter ignores her. Goldie feels irritation rising and tries to suppress it.

‘Lu-Lu, come on, we’ve got to go.’

Nothing.

‘Luna!’ Goldie snaps, losing the battle. ‘Now! We’ll be late!’

With a theatrical sigh, Luna snatches up her school bag, stuffs her notebook inside and stomps off in the direction of the front door.

‘It’s raining!’ Goldie calls after her. ‘Coat!’

On the table, in the wake of Luna’s huff, the bonsai’s leaves flutter as if blown by a sudden breeze. Goldie watches

as, one by one, the leaves shrivel and drop from their branches onto the tablecloth.

They live in the little flat above the women’s shelter and must pass each of the eight residents’ rooms to leave the house. The rooms aren’t always occupied, but it’s rare that one lies empty for more than a few days. If the women and children are already up and milling about, this takes a while, but usually Goldie manages to usher her daughter out quickly enough to avoid much delay. If it was up to Luna, she’d stop at every room and engage each occupant in conversation, enquiring as to their well-being, their hopes for the future. It’s highly impractical, of course, but Goldie is still proud to see how deeply Luna cares, how she befriends every arriving child. The children are traumatized, to varying degrees, though not as much as the women, who’ve taken the brunt of the abuse. But, even if they’ve not been beaten, the children have endured years of suffering. Yet Luna always has a healing effect on them and, after only a few hours of play, they usually come out of their shells, a little stronger, a little happier.

If Luna had been an ordinary nearly-ten-year-old, Goldie would never have considered raising her in a women’s refuge, but it became apparent soon after Luna was born that she was very far from ordinary. When she’d slipped out onto the hospital bed after the final agonizing push, the midwife who’d caught her had let out a little cry of astonishment. When she’d rested the baby on Goldie’s chest, the dazed new mother had gazed down at the triplicate scars of crescent moons and stars etched on her daughter’s shoulder

blade. The first time Luna suckled at Goldie’s breast, her throat glowed as if she’d just swallowed sunlight. Sparks showed at her fingertips as soon as she uncurled her tiny fists; she’d created spontaneous waves in her bathtub whenever Goldie bathed her, and inadvertently set fire to flammable objects so often that Goldie had to start hiding toys, and especially books.

Every day while Luna is at school Goldie spends time with each of the women – all Sisters Grimm – encouraging them to come to Everwhere, where she can reinvigorate their strength, teaching them skills and powers they didn’t know they possessed. A volunteer therapist comes one day a week and a few retired women help with the day-to-day running of the shelter. But Goldie does far more than anyone else. Sometimes she wonders if Luna might resent it, but she seems only to relish it.

‘Do you have everything?’ Goldie asks, as they reach the school gates.

‘Yes, Ma,’ Luna says, glancing in the direction of a gaggle of chattering girls. ‘I’ve got everything. I’m fine. Okay? Now—’

‘I wish you’d eaten more,’ Goldie says. ‘What about a biscuit before you go in?’ She starts fishing through her coat pockets. ‘I’m sure I’ve got—’

‘I told you, Ma, I’m fine.’ Luna starts to pull off her coat, an unnecessary accessory even though Goldie insists on it, since rain always seems to slip off her anyway.

‘All right, all right, I’m just . . .’ Goldie leans in to kiss Luna’s head, but her daughter dodges the kiss and slips away to join her friends.

‘Mrs Clayton? May I have a word?’

Goldie turns to see Luna’s teacher looming behind her.

‘Oh, hello, Ms Walker,’ she says. It seems silly to address her like this; she’s not her teacher, after all, but Goldie is never sure what else to say. She’s also lost the will to tell Miss Walker that she’s not married and, even given that impossible eventuality, she certainly wouldn’t become a ‘Mrs’ anything. Swallowing the desire to lecture the teacher on the finer points of feminism, she smiles. ‘How lovely to—’

‘Mrs Clayton,’ Miss Walker interrupts, never one to waste time on pleasantries. ‘We need to talk about Luna. Will you . . .’

Goldie’s porridge-heavy stomach lurches. Miss Walker keeps talking, but Goldie doesn’t hear a word. She refocuses.

‘I’m sorry, what did you just say?’

‘I said –’ Miss Walker looks irritated at being forced to repeat herself – ‘will you be able to attend a meeting with myself and the head teacher at four p.m. tomorrow?’

‘Yes, of course.’ Goldie thinks of the sparks at Luna’s fingertips. Of her ability to make things grow and, more worryingly, wither. Her tendency to levitate ever so slightly whenever she’s excited. Has she done this in school? Do they know ? ‘But . . . I wonder, um, might you be able to give me some idea what it’s about in advance? Should I be concerned?’

Miss Walker pauses. And in that moment – seeing the tightening of the teacher’s jaw and the concern in her eyes – Goldie realizes that she shouldn’t simply be concerned; she should be scared.

Chapter Two

10.28 a.m. – Goldie

‘Social services?’ Teddy repeats the words for the dozenth time, perhaps attempting to erase reality with a reverse conjuring spell. ‘But . . . why?’

‘I told you, I don’t know.’ Goldie wipes her eyes ineffectually with the back of her hand. She’s trying not to snap at her brother, who’s been nothing but kindness since she collapsed in tears on the dilapidated sofa of the communal living room – the one usually reserved for receiving new arrivals to the refuge – providing her with endless cups of undrunk tea and plates of uneaten biscuits. Not even a chocolate Hobnob could take the edge off at a time like this. ‘They wouldn’t tell me,’ she says again. ‘I suppose they don’t want to give me advance warning or any chance to prepare a defence. Surprise is their mode of attack.’

‘Then why did the teacher tell you?’

Goldie crosses her legs under her and reaches for a cushion to hug. ‘No idea.’ She shrugs. ‘An uncharacteristic bout of kindness? Maybe they have to give just enough notice to be sure you’re available but not enough that you can leg it.’

Teddy considers this. ‘And she didn’t even give you a hint as to what it might be about? They don’t call in social services for nothing.’

Goldie, who’d been plucking a stray thread from the

cushion, now glares at her brother. ‘No shit, Sherlock,’ she snaps, forgetting her resolve. ‘I know that. And no, I’ve been going over the conversation again and again, and the bloody woman didn’t give me a single fucking clue as to why they want to take Luna away from me, all right?’

Teddy sighs. ‘Oh, sis.’ He stands from his chair, steps round the coffee table and sits on the sofa beside his sister. It sags beneath his weight, an unwelcome reminder that the refuge is in dire need of renovations and repairs. The sofa is the least of it. ‘Don’t jump to the worst. They’re not going to—’ He tries to pull Goldie into a hug, but she shrugs him off.

‘They’re not going to sit me down for a cuppa and a chat, Ted.’ Goldie clutches the cushion. ‘This is the fucking social services. It’s their job to take kids away; don’t be so naive.’

‘Come on, Gee-Gee,’ Teddy says, hoping to soothe her with the pet name he’d called her before he could say her name. ‘They take kids from abusive, neglectful parents.’ He slips his arm around her shoulder. ‘And that’s the last thing you are. Quite the opposite, in fact.’

Goldie blinks at him with puffy eyelids. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Well . . .’ Teddy treads carefully. ‘I mean . . . you’re the flip side of neglectful, aren’t you? You spend half your life taking care of Luna and the other half taking care of the women and children who come to the shelter. No one could accuse you of—’

‘Maybe that’s what they’re concerned about,’ Goldie interrupts. ‘That a women’s refuge is an unsafe place to raise a child. After all, they’ve got no idea that this place is protected by . . . spells and the strength of our sisters. If I told

them about us, about me, they’d lock me up and throw away the key.’

‘I don’t think they do that sort of thing anymore,’ Teddy suggests. ‘It’s not the nineteen-fifties, thank God. Anyway, if they did lock you up, you’d only need to escape to Everwhere and never come back. Speaking of which, Luna could do the same if they took her a—’

Goldie starts to sob again, gulping air and spluttering words. ‘Wh-what the hell are you t-talking about? I-I can’t raise Luna in Everwhere – how would I educate her? What would we eat? And we’d never see you again for a start, let alone the fact that I can’t abandon the shelter – that’s the most stupid thing you’ve ever said. We wouldn’t survive a week in Everwhere. You might as well say we could run away to the Amazon!’

‘Sorry,’ Teddy says, abashed. ‘I didn’t mean . . . I was only trying to be helpful.’

Goldie drops her head into her hands. ‘I know, I know, I’m sorry. It’s not your fault. It’s just, I’m just . . . terrified. I’ve spent the last nine years doing everything I can to protect her and now . . .’

His arm still over her shoulder, Teddy tries again to pull his sister into a hug. He wants to hold her as she once held him, when he was small enough, comforting him after their mother died, taking care of him every day since. This time she lets him.

‘Look, sis, you’re the most loving, dedicated, allconsumingly caring mother I’ve ever encountered – you put our mum to shame. There’s no way anyone is going to take little Lu-Lu from you. And, if they try, I won’t let them. Okay?’

With her face pressed into her brother’s chest, Goldie nods. But she’s still terrified and she doesn’t know what to do.

‘I just wish Leo was here,’ she sniffs. ‘He should be here.’

‘I know,’ Teddy says sorrowfully. ‘I wish he was too.’

11.57 p.m. – Goldie

Goldie sits with her back pressed into the corner of the sofa in her own flat, Liyana’s Tarot cards in her lap. A large glass of red wine rests on the coffee table beside an already halfempty bottle. Luna is asleep in her bedroom, but Goldie knows there’s no point in going to bed since she won’t sleep tonight. In a feat of Herculean strength she’d managed to pretend that nothing was wrong, had acted (almost) normal with Luna, and if her daughter noticed anything strange she didn’t say anything. Goldie forced herself not to squeeze Luna tight, nor stare at her for too long, though she was desperate to do both. She forced herself to chat and smile and make jacket potatoes with baked beans and cheese (Luna’s favourite) as if life was perfectly normal and she wasn’t teetering on the edge of a nervous breakdown.

But as soon as Goldie was alone and free to hurl herself headlong into said breakdown, she did. Three hours later, after devouring a tub of ice cream, a plate of Hobnobs and half a bottle of wine, while simultaneously working her way through an entire loo roll, Goldie feels nauseous and exhausted. Her stomach hurts, her head hurts, her nose hurts, her eyes hurt. But what hurts most of all, as always, is her heart.

Glancing down at the Tarot cards, Goldie feels a pang of longing in her bruised heart for her sisters. She’d once

thought that a body could only hold so much loss and sorrow before it simply imploded and the unfortunate soul died of a broken heart. But she’s since learned that the human body is cruelly strong and able to absorb what seems an unbearable amount of pain and yet still keep functioning.

‘Oh, Ana.’ Goldie strokes a finger over the facing card: the Three of Cups. Friendship, camaraderie, celebration. ‘I wish you were here. I know, I know.’ She sighs, continuing as if Liyana were sitting beside her now. ‘I can visit you in Everwhere; I can talk with you whenever I wish. But it’s not the same. No one reads the cards like you . . .’

A lump rises in her throat as her thoughts pass, immediately and inevitably, to Scarlet. The sister she can’t even speak to, let alone see or touch. The sister who might be living in Australia, or dead, for all she knows. Yet, if the latter, then surely Scarlet’s soul would return to Everwhere and Goldie would find her there . . . So Goldie still holds out hope that one day she will meet her missing sister again.

After thinking of Scarlet, Goldie’s thoughts don’t pass to her beloved Leo, because they never really leave him. Her awareness of his absence, and her longing for his resurrection is ever present, and a portion of her mind always dwells on him, like a tune she can’t stop humming. Goldie’s love for Luna’s father is the soundtrack to her life.

Absently, her hand slips from the cards and into the pocket of her hoodie. She pulls out a small crystal skull. The stone is black but flecked with starbursts of white, its chin protruding with carved teeth, and its deep eye sockets, though empty, seem to be watching. It belongs, along with the Tarot cards and a small wooden statue of Mami Wata, to Liyana. However, since she has no use for material things in