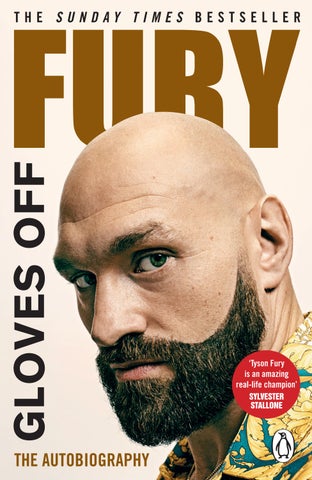

During his storied 36-fight career, Tyson Fury has established himself as one of the best heavyweight fighters of all time.

Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson.

From Irish Traveller heritage, the ‘Gypsy King’ first shocked the boxing world in 2015, when he stunned long-time champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles.

Due to struggles with his mental health, Tyson did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever, until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split-decision tie. Tyson was victorious in the second fight against Deontay Wilder in February 2020, defeating his opponent by seventh-round technical knockout. In October 2021, Tyson concluded the trilogy with victory against Deontay Wilder by an emphatic eleventh-round technical knockout. In March 2022, Fury successfully defended his heavyweight crown at Wembley Stadium against Dillian Whyte, winning by knockout with a devastating uppercut in the sixth round.

Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He lives with his wife Paris and seven children in Morecambe, and most mornings can be found running and training along Morecambe Bay. This book was first published in November 2022 and does not span boxing events that have occurred since then.

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Century in 2022 Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Tyson Fury, 2022

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Typeset in 13.35/17.13 pt Perpetua MT Std by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn: 978–1–804–94157–7 www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This book is dedicated to anyone with mental health problems. Know this: there is hope and nothing is impossible. If I could make my comeback, so can you.

Warning: sensitive content. This book contains depictions of a suicide attempt and suicidal thoughts and may be troubling and triggering for some readers. If you have been affected by mental health problems and have experienced or are experiencing suicidal thoughts please get professional help immediately – a list of mental health resources are available at the end of this book. This book draws on my personal experiences, and I hope you may find some of my approaches to mental health useful. But what works for me will not work for everyone and I am not an expert, so you may require medication and medical help. The author and publishers disclaim, as far as the law allows, any liability arising directly from the use or misuse of the information contained in this book.

23 April 2022. Wembley Stadium. Fury v Whyte. It was show time, dossers.

And the arena went crazy. Lights and camera flashes flickered around the crowd. Lads threw pints; women screamed my name. And who could blame them? This was a showdown for the history books, a bout against the British heavyweight, Dillian ‘The Body Snatcher’ Whyte at a rammo Wembley Stadium heaving with 94,000 punters – the biggest ever crowd for a European boxing match. After two years of pandemic misery, the country was thirsty for a massive party and The Gypsy King was going to give them one. The hype had been so big that ticket sales for Fury v Whyte outsold some of the most famous names in pop music.

Making an entrance to remember on a night like this was a big deal, so I was carried into the arena on a gold throne. And as I was hoisted into the air, I felt like a master of the universe; this is the superstar atmosphere I’ve always enjoyed as a boxer and the experience of connecting with it has always been surreal and incredible. At that moment, I

became super-charged, like I’d been plugged into the electrics and my adrenaline soared. Not bad for an old, fat fella, I thought, looking around at the craziness. A bald-headed lad from Morecambe, a seaside town in the middle of nowhere . . . But even though I was partying too, my eyes were still fixed on the prize. I needed a win to match the pizzazz.

I’d picked a soundtrack to match the mood and it rocked through the Wembley PA . The first cut was ‘Sex on Fire’ by Kings of Leon – a song that had often helped me to find a groove in training. I belted it out with everyone in the stadium, like we were pals in a karaoke pub, or celebrating an England win in the World Cup. The second song, ‘Juicy’ by rapper The Notorious B.I.G. (AKA Biggie Smalls), was there because its lyrics – It was all a dream – reminded me of my own life. Being Tyson Fury was like a dream. In Biggie’s case, he’d read hip-hop magazines as a kid, listened to rap radio and stuck pictures of his heroes to the bedroom wall before becoming a legend. I’d been the same, but with boxing. I’d watched the fights, read about the great heavyweights and tacked photos of my heroes around the place. Some people told me I wouldn’t make it as a fighter and the same had been said to Biggie about his music career, but neither of us had listened to the critics, we’d both reached for the stars instead. And tonight, I was ready to shine.

The crowd seemed to whirl around me like leaves in a hurricane, and I was the eye. As the noise for my final

entrance continued to build, I knew that these were my people and this was my moment. The nine-year-old version of myself would have loved the buzz and the colour. So soak up every second of it, pal, I thought. And when I saw the ring ahead it was hard not to think about what would happen to the boxing world once I’d left. Who could fill this void? At that point, retirement was on my mind and about to become a major talking point, but if I walked away for good, the sport would probably return to how it was, pre-Gypsy King, full of boring fighters that very few people cared about. The papers were going to miss me too. I only had to crack open a can of lager, or walk into a pub with my shirt off for them to write a front-page headline. These were the nights I lived for. I was like a gladiator striding into his arena and it was hard not to feel a sense of pride because my contest with Whyte seemed like so much more than a boxing match. That had a lot to do with the date: 23 April, St George’s Day, a moment in the calendar that means a lot to me because I’m very proud of my roots. Fury v Whyte was an all-English clash too, a moment in national sporting history and you know how us English do when it comes to a battle: we hold our shit down. Psychologically, the fact that I was fighting on home turf for the first time in years was a motivational boost. It was a death or glory clash and I wanted to do everything in my power to bring a buzz to the nation.

For this momentous occasion I was wearing a white and red robe, England colours. I’d also heard a person could look much bigger than they actually were when dressed in white, thanks to a trick of the eye. (In much the same way that wearing black creates a slimming effect.) To my opponent I must have looked humungous, like a 6 foot 9 monster. And terrifying, because I’d picked a pair of specially designed St George’s Cross boxing gloves for the battle. A fist wrapped in a flag. My plan was to smack Whyte in the mouth so hard that the country would be shaking for days afterwards.

Some people were doubting my chances of winning, but no way was I was messing up at Wembley Stadium, and to make sure I ran through my usual pre- match routines during the build- up. In the dressing room, I moved about in my underpants, singing and dancing, cracking jokes, only stopping to take a seat on the massage table to watch the undercard and have my hands wrapped. I’ve studied boxers my whole life, as both a fan and a fi ghter, and knew that before a title bout I was unlike a lot of the others. Stress ricocheted off me, even in a venue as big as Wembley Stadium, and I liked to mess about with the music cranked loud. I’ve seen many other changing rooms throughout my career and most of them were like death parties. You’d think the boxers involved were going under the guillotine. Blokes were pale and panting; they shook with nerves and punched the walls as a way of firing

themselves up. Everyone alongside them looked frazzled with terror.

But not me: not in my space, and definitely not at Wembley. I was a disco diva getting ready to shine; I was about to get paid and about to get laid and I loved having the cameras and the press around me in the dressing room because it added to the sense of occasion. During those moments I could tell what everybody was thinking: Why is he acting like this? He’s going out there to fight a man who could potentially kill him with one punch. He just don’t give a damn . . . But that’s what sets me apart from most people in life. Giving a damn is not my thing, and knowing my resolve won’t wobble under pressure, I have every confidence my body won’t falter either, no matter the challenge. The faith that I can withstand all punishment then creates even more self-belief in what is an ever-expanding circle of positivity. Wembley, though being my biggest ever fight, was no different. I was ready to go.

I ran through a warm-up with my dad John alongside me, plus my trainer SugarHill Steward – a former Detroit policeman and the nephew of the Boxing Hall of Fame trainer, Emanuel ‘Manny’ Steward – and the nutritionist George Lockhart. Together we moved through some pad work. Bang! Bang! Bang! Everything felt nice and easy, though I wasn’t overconfident or in a massively cocky mood. I always took precautions and as I got myself together for

the walk into Wembley, I pulled my team about me for a group prayer.

‘Dear Lord, please give us strength and the ability to go in there and give our best performance,’ I said. ‘We pray for the opponent to do exactly the same, and most of all, we pray that both men can come out in one piece and go home to their families.’

The time to rock ’n’ roll had arrived.

• • •

My boxing life has been made up of two careers. The first took place between 2008 and 2015, a period in which I was unable to recognise the psychological demons dragging me down. They pulled on me like a rucksack full of stones, despite the fact I was on my way to becoming the heavyweight champion of the world. The second career kicked off in 2018 after a brutal battle with my mental health, a war I’m still locked into today. Through sheer will I was able to overcome my issues and return as the planet’s most entertaining pugilist.

Most books begin at the beginning and end at the end, which might work for your average, run-of-the-mill author. But The Gypsy King is a bona fide legend and a once in a lifetime superhero, so why on earth would I tell my story in an average, run-of-the-mill way? It’s for this reason that

Gloves Off starts at the end, and finishes at the beginning of the end, with my full and uncensored roller coaster of a journey jammed in between – and the revelations will spin your head in the best possible way. I’ll tell you about the glories of my second career and discuss the idea that I might leave the stage while still at the peak of my powers. Then I’ll detail where I came from and how I defeated the then champion, Wladimir Klitschko, in 2015 to become a boxing Titan, before explaining how I very nearly lost everything. (But I was able to claw it all back.) Yeah, I wrote about depression in my first book Behind The Mask, but everything was so raw back then. I was still working through my illness at that time and I’ve since found a new sense of perspective, in and out of boxing. I’m also at a point where I have a reckoning to contend with: the realisation that my professional adventure is drawing to a close. It’s from this perspective that I’ll relive several other famous events and fights that I’ve written about previously. I hope you’ll enjoy the new insights and a fresh twist or two.

So while I’ve long been admiral of HMS I Don’t Give A Crap, the most entertaining showman since the days of Muhammad Ali and the greatest fighter of my generation, it’s important to know that, as far as I’m concerned, boxing has always been a business with a shelf life. A sport, yes, a lucrative form of entertainment, for sure, but statistically the people that stay in the game for too long have a

tendency to get damaged, really damaged, and I don’t want that happening to me.

There’s also a risk that my career has been shortened by the way in which I’ve lived my life. Health and nutrition was not exactly a priority for large chunks of my time as a pro: I ballooned in weight between bouts and then, during the mental health breakdown that started in 2015, I boozed, binged and tried cocaine. There was even an attempt at ending it all a year later when I pointed my Ferrari at a bridge and slammed on the accelerator, though I changed my mind at the last second and pulled away – thank God. When I eventually asked for help I was diagnosed as being bipolar, paranoid and suffering from anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD ). I later recovered, but my mental health issues remain a constant work in progress – from time to time I can have suicidal thoughts, though I now understand what’s needed to keep my demons at arm’s length.

It’s not as if boxing is my entire world either. The reality is that I’m a husband, a dad, a son, a brother, and an uncle.

My family are my armour and Paris and my six beautiful kids are always in my thoughts because they’re so precious to me. On the eve of my 2021 fight with Deontay Wilder I slept on a hospital floor as our youngest child, Athena fought for her life shortly after being born and her successful battle inspired me to win mine. Three years earlier,

it was Paris who picked me off the canvas when I’d been poleaxed by depression. At the beginning of my career, my dad and my uncles provided me with the tools to become a top boxer, though I was also taught how to earn an honest day’s wage by selling second-hand cars. Throughout my life, the Fury family has provided all the love and support I’ve needed to succeed. I want them to receive the same love as me, from me.

So while getting my face punched in for a living has put millions of pounds in the bank, a fighter needs to know when their time is up – and mine is near. The issue of whether I will fight again could have been settled by the time you read this book: I might have retired, knocked out another dosser or perhaps agreed to a bout in the near future (and the speculation surrounding that decision has been a right circus). In this book I want you to know the truth about my thinking regarding these decisions. A lot’s been going through my head, and me changing my mind lately isn’t a flippant thing. Walking away from boxing may be the hardest thing I ever do. All I know is that I don’t want to overstay my welcome, ruin my legacy, or die from a big right to the side of the head. And believe me, an ending like that has felt worryingly real at times. I even experienced short-term memory loss following that bruising encounter with Wilder in 2021, when, in the hours after the win, my head covered in tennis ball-sized lumps, it was impossible

to remember how many times I’d gone down. Everything was foggy, and the experience frightened me. No way do I want to end up living out my days in a wheelchair, or eating my dinners through a straw.

So here it all is for the first time: my boxing life set out in full, from the first fight to (maybe) the last, the highs and the lows, and all the hits and knockdowns in between. Over the coming pages I’ll dish out stories and secrets; I’ll tell you about my toughest adversaries in and out of the ring, and lay out the reasons for why I’ll eventually walk away from professional boxing in my prime, as a legend. Believe me, no other boxing story can lay a glove on this one.

So what are you waiting for? Get stuck in!

Tyson Fury, Morecambe Bay, September 2022

Here’s what was going through my mind at the end of 2021. I was tired of boxing. Sick of it. I’d well and truly had enough and the thought of retiring was becoming more and more appealing. It hadn’t been an overnight brainwave though, or a kneejerk reaction. Instead, the idea had been building for a while, over a period of time and a number of hits to the head and body. But despite my feelings, I still wanted to consider the implications long and bloody hard because walking away from the sport I’d once loved for so long wasn’t an easy thing to do.

The bottom line was this: at the time I was thirty-three years old and the feeling that I might have been getting on a bit was playing on my mind. Some people could have argued that, at my age, I was still in my prime as a heavyweight; I suppose ordinarily that would have been the case, but one of the things I’d learned from studying boxing was that too many people struggled to recognise when their time was up. For one reason or another, they couldn’t walk away and in the end they hung around for so long that their decision eventually came back to bite them on the arse. I’m talking about the fighters that didn’t pay enough attention

to their game, or couldn’t recognise their breaking points. Rather than listening to their bodies, or the subtle warnings their brains were sending them, they pressed ahead. Perhaps they’d chosen to ignore the alarm bells because they were in denial, or had become too obsessed with money and fame. Having carried on for too long – taking on one last match, maybe ten – they then tarnished their record by losing a lot of blood in the battle, destroying what might have been an incredible legacy. No way was I following that path. I was the best fighter in the game at the time. What I’d achieved was more valuable than a massive bank account, or the satisfaction of seeing my face on the telly.

I even watched Wladimir Klitschko refuse to accept his truth close up when I came to fight him in 2015. He was thirty-nine years old and clearly slowing down, even though he was still the reigning champion. For some reason, he couldn’t see his end was on the horizon, but I could. So I told him.

‘Every dog has its day,’ I said. ‘The mind might be willing but the body won’t follow.’

He wasn’t having it. ‘Age is just a number, it’s how you feel.’

I shook my head. ‘You’ll find out that’s not true. At the end of the day, you’ve been a great world champion, but boxing’s a young man’s game.’

I proved my point shortly afterwards, beating him in the Esprit Arena in Düsseldorf after a full twelve rounds and a unanimous decision to take the WBA (Super), IBF, WBO, IBO and Ring titles for the first time. So I knew that there was no way of cheating time; what had happened to Klitschko could just as easily happen to me if I wasn’t careful, and a few years after my 2018 comeback, I found myself weighing up my options. I realised there was nothing to be gained by overstaying my welcome like an unwanted party guest.

Losing was one thing, but the risk to my mortality was a whole other ball game, and so far I’d avoided any serious injuries. That said, I was experiencing pain on a daily basis. The wear and tear on my body was becoming noticeable, mainly in my elbows and shoulders, but that was hardly surprising given I’d banged, punched and ripped at things for a living. Most of the time I gritted my teeth through the discomfort and whenever that got too much I’d see a doctor. Still, I understood there was a chance my luck would run out at some point and that I’d injure myself in such a way that I would be screwed up for the rest of my life. A serious back or hand injury didn’t bear thinking about, though the more extreme consequences of violence were much nastier, like a bomb to the side of the head that could kill or paralyse me. There was no way I wanted to put my family through that ordeal, especially Paris, because she would be the one

left to push me around for the rest of my days. Those risks had to be taken seriously.

There was also the understanding that my career had affected everyone around me, from the minute I’d turned pro. Mum never watched me fi ght; she hated it. Paris turned as white as a sheet whenever I took a punch; she hated it too. While the kids had grown up knowing all about my career and loved me being in the limelight, they didn’t like it when another fi ghter laid a glove on me; I was an Invincible to them. Of course, I had a different perspective. (Well, I would.) Whenever I was fi ghting, only the heavyweight world championship was on the line and I didn’t give much thought to anything else because I knew I was going to win. But for the family as a whole, the stakes were so much higher. My making it through a fi ght unhurt was their world and they used to stress that everything might come crashing down were I to mess up in some way. It was time to take that stress into consideration.

That’s why boxing is such a selfi sh profession and boxers are such selfi sh people. A fi ghter risks his or her health alone. That means they have to think about themselves a lot of the time. And if you think I’m chatting bollocks, take a look at the fans screaming and yelling at the men or women in the ring the next time you’re watching

a fi ght in a rowdy stadium or pub. You think they’d want to take a punch or ten? The only person that can take those blows, or throw those shots back, is the person in the battle. So don’t be surprised when that person then dedicates every hour of their day to being the best, because the reality is that if they don’t, there’s a good chance their next opponent will cause them some serious damage. That’s the reason why any fi ghter worth their salt makes everything about them during the build- up to a big fi ght, even if it means living away from home in a training camp for two to three months at a time. They have to be a selfi sh motherfucker. The chances of them being a success are slim otherwise, no matter how many amazing trainers, nutrition experts or advisers they have about the place.

That is exactly my attitude. During training camps, I am like a Spartan warrior. It doesn’t matter whether I’m preparing to fi ght one bloke or an army, I’m going to do everything to win, my opponents are losing, and I’m not going to let anybody distract me as I work. Everything is blocked out; life’s petty matters have to wait until the fi ght is over. I don’t want to know about any news until the right time has arrived, and at the start of every camp I set out the rules: ‘I can’t be hearing about day- to- day life. I don’t want to know about what happened at the

supermarket. I don’t want to know that someone’s been to the dentist. Tell me about it after the fi ght.’

Like I said, boxing’s a selfish sport. I have to live in a different world.

Paris was OK with that attitude because life had always been that way for us, ever since we’d been kids. I’d always boxed and she’d always understood that I had to become a different person in training camp. I couldn’t be in Husband Mode; I couldn’t be in Daddy Mode; or Brother, Son, or Friend Mode, for that matter. I had to be in Fight Mode because so much was on the line, but there was no doubt it had been a massive sacrifice for everyone. Throughout my career I’ve been away from my family for long periods of time, whether that was by being on the road, travelling or training, so coming home was another reason to consider retirement – I owed it to everyone I loved.

None of these motives for retiring should be mistaken for fear by the way. I certainly don’t feel scared for myself; it’s the people around me I worry for. I’ve never been intimidated by an opponent and I’ve always stepped into the ring knowing I’m going to smash the other fella to bits, whatever happens. In fact, around the time I first considered leaving the sport, I took the kids to a fairground. As we walked past the stalls and through the arcades, I saw a punch ball

machine. A picture of my face glowed on the front in bright lights and underneath, in big letters, was something I’d said in a press conference a few years previously:

I’m not even scared of the devil. If the devil confronted me, I’d confront him as well.

That line pretty much sums up my attitude. I stare down the devil every day, especially when I am dealing with life’s distractions and temptations, though that only really happens when I haven’t been in the gym for a while, or if my routine is thrown out of kilter. My dad thinks I’m weird; as do my cousins and brothers. The other day, Dad said to me: ‘You’ve achieved everything. You’re a multimillionaire. And the best thing you can think of in life is to go to the gym twice a day? You need your head testing.’ But that’s what makes me happy; not exercising makes me sad. So I went for a run to feel better about it all and my dad, brother and cousin ‘kidnapped’ me. They took me for a drive that ended up with them dragging me to all these places that were supposed to be fun, but actually turned out to be non- existent rubbish. It took me away from the house and out of my routine at a time when I wanted to be moving from errand to errand. By the time I’d fi nished running around with them like a headless chicken I felt thoroughly depressed. It messed my day up because I don’t like being idle. I want to get

up at the crack of dawn and work, not stopping until I’ve closed my eyes at night.

In those situations, if ever I do feel bad, I think back to the country song, ‘I’m Gonna Have a Little Talk With Jesus’ by Randy Travis. In the lyrics, the devil tries to drag Randy into a dark spot. The singer even speaks about seeing his face a hundred times, and to get over it, he checks in with Jesus at the end of the day. I’ve decided that’s what I’ll do too, because my belief is that before anyone does anything in life, good or bad, there is a get-out moment. A split second of opportunity where they can either fall prey to the temptation in front of them, or regain some composure and move on. It’s down to the individual to know how to stand strong, but it requires a healthy state of mind to succeed. I want to do everything possible to be emotionally ready for these moments. That way I can make the right call whenever the devil comes around.

So considering my daily showdowns, what makes you think I’d be afraid of a boxing match? • • •

There was another reason to think about quitting while I was still ahead: I’d watched too many of my heroes retiring badly.

The clichéd backstory of a boxer speaks of someone without a lot of brains, certainly someone who hasn’t