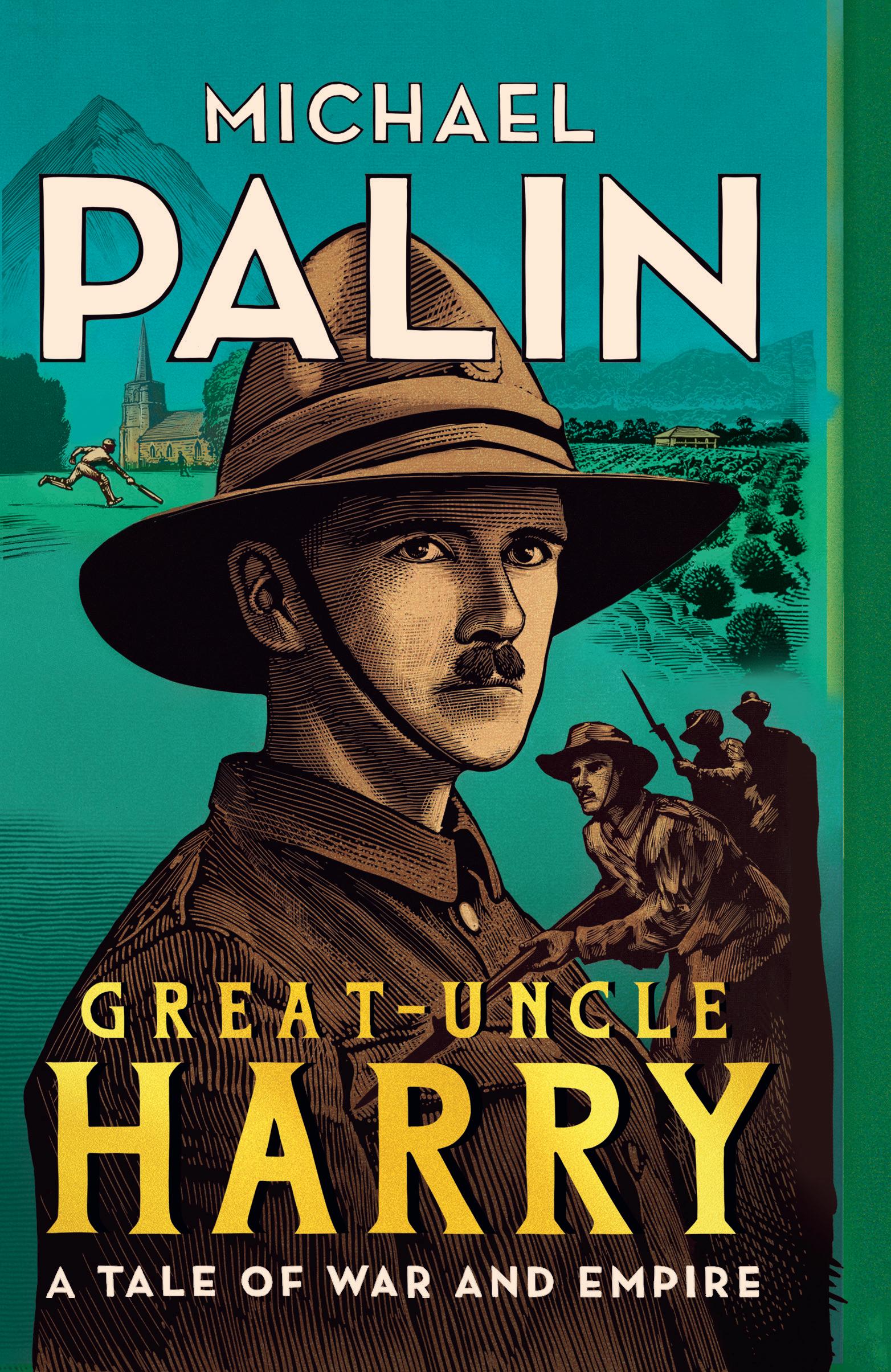

‘A tremendous act of love’

‘A tremendous act of love’

Michael Palin has written and starred in numerous TV programmes and films, from Monty Python and Ripping Yarns to A Fish Called Wanda and The Death of Stalin. He has also made several much-acclaimed travel documentaries, his journeys taking him to the North and South Poles, the Sahara Desert, the Himalayas, Eastern Europe, Brazil, North Korea and Iraq. His books include accounts of his journeys, novels (Hemingway’s Chair and The Truth), several volumes of diaries and Erebus: The Story of a Ship. From 2009 to 2012 he was president of the Royal Geographical Society. He received a BAFTA fellowship in 2013 and a knighthood in the 2019 New Year Honours list. He lives in London.

PENGUIN BOOK S

Michael PalinUK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Hutchinson Heinemann 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Michael Palin, 2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted

The excerpt from Cyprian Brereton’s unpublished memoir on pp. 165–6 is reproduced by kind permission of Annie Coster

Maps by Darren Bennett (www.dkbcreative.com)

Typeset in 11.96/15pt Dante MT Std by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn : 978–1–804–94065–5

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The statue of Sir Philip Sidney atop the Shrewsbury School war memorial.

The statue of Sir Philip Sidney atop the Shrewsbury School war memorial.

At the gates of Shrewsbury School, where three generations of Palins were educated, there is a war memorial on which stands an elegant likeness of Sir Philip Sidney, poet, courtier, scholar and personification of all the finest qualities of the first Elizabethan age.

He died at the Battle of Zutphen in 1586, at the age of thirty-one.

Listed below are the names of 329 other former pupils of the school who gave their lives for their country. Among them is H. W. B. Palin. He died in the Battle of the Somme in 1916, at the age of thirty-two.

Much has been written about the distinguished life of Sir Philip Sidney. Nothing has been written about the life of H. W. B. Palin. But he was my great-uncle, and I felt his story should be told.

Not – I have to confess – that I’ve always thought that. Throughout my childhood and early adult years I was more preoccupied with the present and the future

than the past, more interested in making sense of the course of my own life than that of anyone else. So far as I was concerned, the past was something to be dealt with by people who had time on their hands. It was a luxury.

So when in November 1971 we received a batch of family documents, including a black leather-backed notebook which contained a travel diary kept by my greatgrandfather, a detailed Palin family tree stretching back two centuries, and five barely legible diaries kept by a great-uncle, I’m afraid they seemed nowhere near as relevant to my life as trying to earn a living writing and recording material for a new Monty Python series. Oddly enough, my father and mother seemed equally incurious. The whole bundle of documents ended up being set aside in some dusty cupboard.

Six years later I recorded in my diary the arrival at my parents’ cottage in Reydon, near Southwold, of an Austin 1100, driven by a late-middle-aged lady called Joyce Ashmore, an unmarried cousin of my father. She seemed to be the nearest we had to a custodian of family history, and it was she who had sent the first tranche of documents. Now she had more. ‘A very capable lady with a brisk and confident well-bred manner,’ I wrote. ‘She has a rather heavy jaw, but seems exceedingly well and lively. She is down-to-earth and unsentimental about the family, but interested in and interesting about stories of the Palins.’ It was from her that I first heard the extraordinary tales of the lives of my great-grandparents and how they had met.

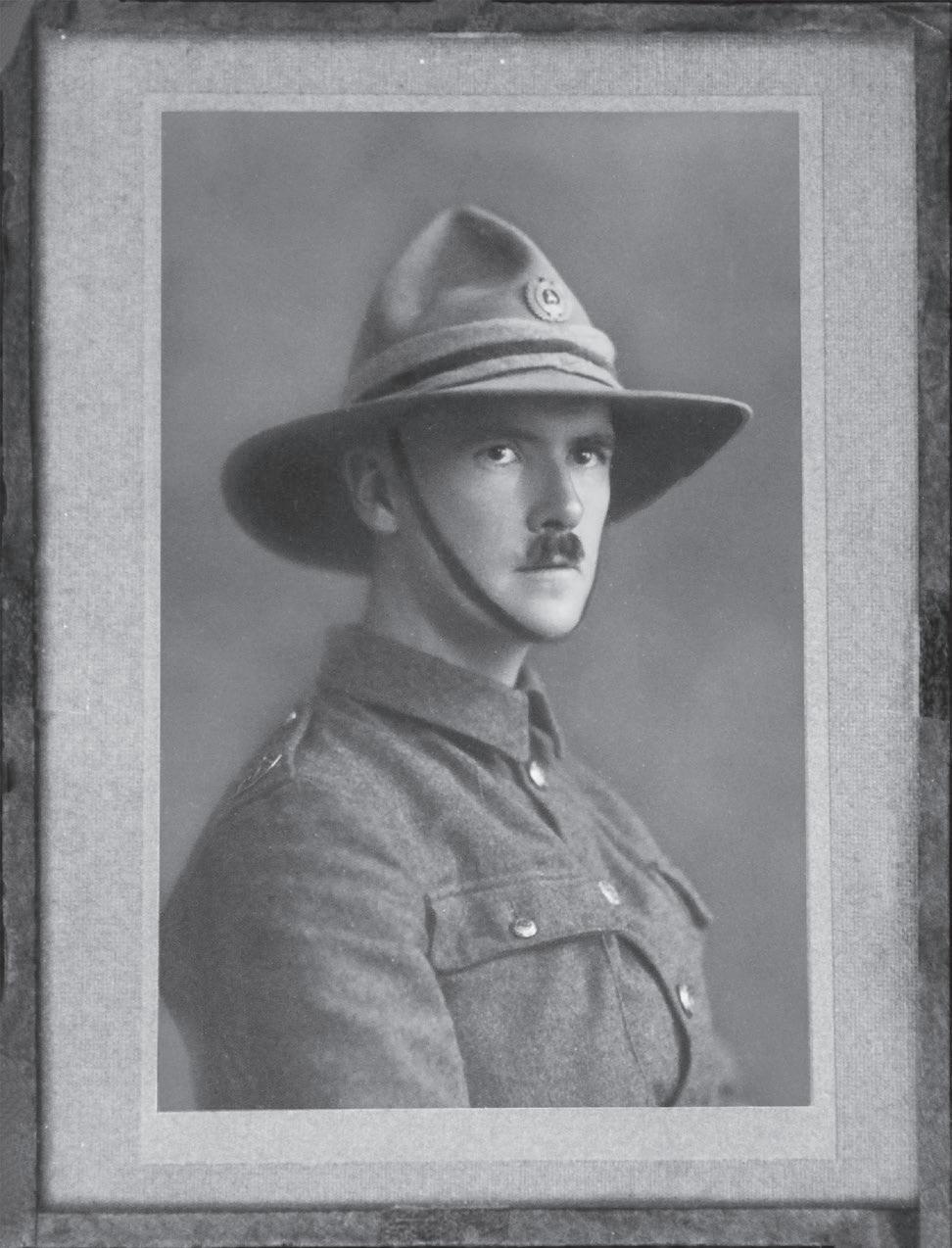

Before Joyce left, she handed over, rather apologetically, a further stash of Paliniana, among which were some photographs. One of these caught my eye. It was of a young man in a military uniform wearing a wide-brimmed hat and throwing a guarded glance at the camera.

I asked Joyce who he was. She was dismissive. It was an unfortunate younger son, she said. Killed in the war. Not much known about him and, by implication, not much worth knowing.

Rather in the same way that being told not to laugh makes you laugh more, her dismissal of this mysterious young man piqued my curiosity. But before I had a chance to do any digging, along came Life of Brian and A Fish Called Wanda and eight televised journeys around the world, and my great-uncle slipped to the back of my mind.

Years later, in 2008, I came across his name again while I was working on a documentary about the last day of the First World War. It was on the wall of another war memorial, this time in one of the Somme battlefields. Just a name, not a grave. H. W. B. Palin. One of many thousands ‘Known Only Unto God’.

I knew then that I had to know more.

The photograph that started it all: Great-Uncle Harry in the uniform of the 12th Nelson Regiment.

The photograph that started it all: Great-Uncle Harry in the uniform of the 12th Nelson Regiment.

Henry William Bourne Palin, known throughout his life as Harry, came into the world on Friday 19 September 1884.

Consulting the On This Day website I find that no one of particular note was born on that day, and that nothing worth recording happened in the wider world.

Harry was delivered in a spacious upper room at the rectory in the village of Linton in Herefordshire. It looks out across rolling hills towards the Welsh border to the west and the Forest of Dean and the Wye valley to the south. At the time of his birth, his mother, Brita, was forty-two. His father, Edward, the vicar of Linton, was two days short of his sixtieth birthday.

Counting all the servants, upwards of a dozen people would have been in the house to hear Henry’s first cries, and in the mild, dry, early-autumn weather of that month the sounds would have wafted out through open windows to the men working on the home farm.

At that time husbands were kept well away from wives in labour, and as their seventh child was being thrust into the world, Edward would most likely have been down in his study mapping out Sunday’s sermon or hearing tales of hardship from distressed parishioners. But like everyone else inside or outside the house, he would have been

listening out for the sounds from the bedroom above. And not without some anxiety.

By the time Harry made his entrance Brita had had half a dozen children in ten years, the last one being born more than six years earlier. Bearing a child at the age of forty-two was not without risk in an era when so many mothers perished giving birth. For Brita, another pregnancy, so long after the previous one, might well have been something of an unwelcome shock. In any case, of course, she already had a substantial family.

But then, large families were common in those days. With contraception methods limited to abstinence, withdrawal or the rhythm method, it’s not so surprising that the average number of children born to middle-class couples married in the 1860s was far above the two that it is now. Charles and Emma Darwin, for example, had ten.

The impressive stone-walled vicarage at Linton which was the infant’s first home was built in the fashionable Gothic Revival style – part French chateau, part German schloss. It was no ordinary rural rectory, but then Brita and Edward Palin were no ordinary couple. The story of their life together was remarkable by any standards. It was one of achievement, sacrifice and an unrelenting sense of purpose. A Victorian success story of which Henry William Bourne was the latest manifestation.

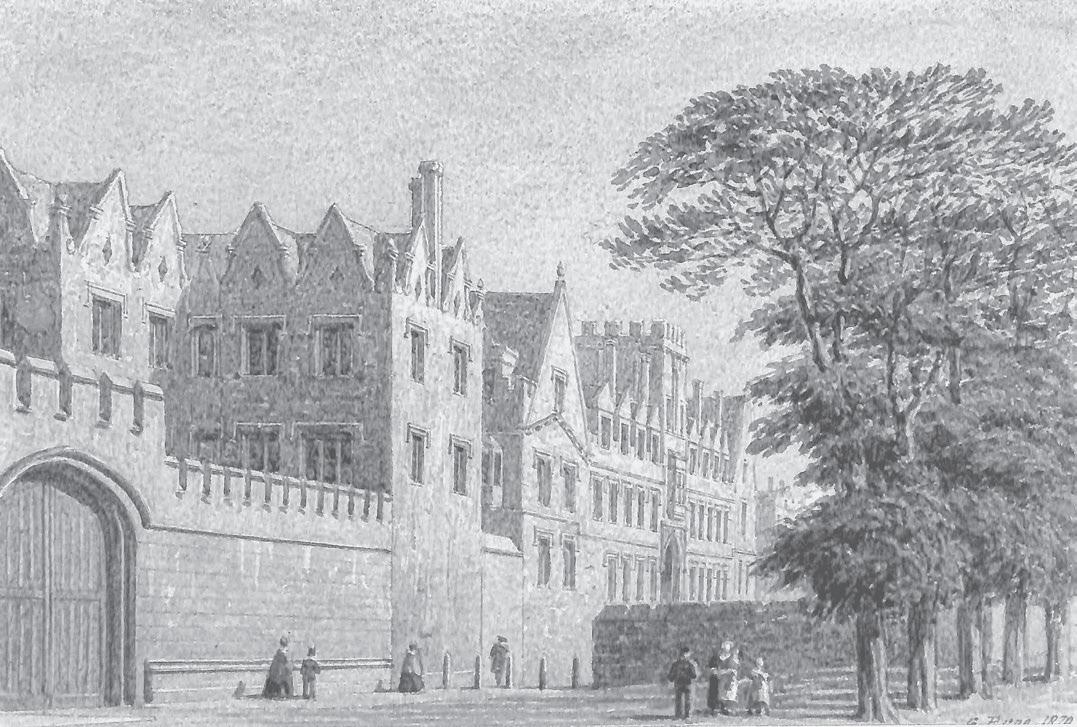

St John’s College, Oxford, where Edward Palin was an undergraduate and a Fellow. A watercolour of the St Giles’ front by George Pyne, c.1870.

It is the summer of 1859 and Edward Palin, perpetual curate of St John the Baptist’s, Summertown, and Fellow of St John’s College, Oxford, is off on his summer holidays. He is thirty-three years old, a highly successful member of the college, recipient of any number of awards and exhibitions, a lecturer, preacher and since this last summer a Bachelor of Divinity. He takes his teaching seriously and is well respected.

Edward was the older of two children born to Richard Palin, a storehouse clerk from St Luke’s in Middlesex, and Sophia Freeman. Edward’s grandfather, another Richard, had come to London at the end of the eighteenth century. Previously the Palins had been a Cheshire family, and, thanks to Edward’s exemplary record-keeping, I’ve been able to trace them back to a George Palyn of Wrenbury. Born in the reign of Henry VIII, he was a member of the Girdlers’ Company who made enough money to endow exhibitions for ‘poor scholars’ at Brasenose

College in Oxford (something I didn’t find out until after I’d left that establishment in 1965) and almshouses in Finsbury and Peckham in London. The Peckham properties were intended specifically ‘for the relief and sustentation of six poor men’. They’ve since been rebuilt, but still bear the name Palyn’s Almshouses, though you’d have to have around a million pounds to live in one of them now. George also bequeathed £500 for one of the bells at Bow, for which he was thanked with the accolade ‘Cheshire made sweet Bow Bells chime’. His grandson, Thomas Paylin, was one of the three boys who, in 1651, helped hide the future King Charles II from Parliamentary forces after the Battle of Worcester.

For the next two hundred years the Palin family tree was a little less bushy, a little more obscure. Sadly, I’ve been unable to find out that much about Richard Palin – what, for example, his work as a storehouse clerk involved, or how much he earned – though I do know that he and Sophia had a house in Artillery Lane in Shoreditch and that they were listed as living there with four servants in the 1841 census. I have also discovered that he and Sophia were among the first to be buried in Highgate Cemetery, just around the corner from where I live. Their gravestone is next door to those of the family of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Whatever their precise circumstances may have been, it’s clear that Richard and Sophia were determined to give their only son the best start in life. In the mid-nineteenth century it’s estimated that no more than five to six thousand children a year were able to get an education that

fitted them for university, but the couple managed to secure Edward a place at Merchant Taylors’ School, which specialised in subsidised education for bright pupils from the trading – as opposed to the landed or military – classes. From there he proceeded, via a scholarship, to St John’s College, Oxford. Founded within a few years of Merchant Taylors’ in the mid-sixteenth century, and by the same man, St John’s operated something of a closed shop with the school: thirty-seven out of fifty of the scholarships offered by the college were reserved for Merchant Taylors’ pupils (a situation that would change in the light of the report of a Royal Commission in 1852). Edward began his academic studies at Oxford on 26 June 1843. Around the time his future wife was born.

Edward worked hard and did so well in his exams – which would have been both written and oral (the viva voces ) – that he secured an exhibition, ensuring that most of his undergraduate studies were paid for by the college. He then went on, in the Easter term of 1848, to secure a firstclass degree in Literae Humaniores – ‘Lit Hum’, or ‘Greats’, as it was colloquially known; Classics as we’d call it now. He was clearly a talented and assiduous student. A heavy leather-bound, brass-clasped ledger book, in which from November 1849 onwards he began to record his thoughts, ideas and general jottings, offers a treasure trove of clues as to his character and aspirations at this time. There are passages admiringly and laboriously copied out from Scott, Wordsworth, Shelley and Coleridge, which

reveal Edward’s interest in and empathy with nature – for example, he has highlighted Coleridge’s line, ‘O Nature! Healest thy wandering and distemper’d child’. There are odd statistics that clearly caught his fancy: ‘A clergyman writes that a pair of sparrows have been known during the time they were feeding their young, to destroy every week 3360 caterpillars.’ There are jokes he enjoyed: ‘An undergraduate with a cigar in his mouth is accosted by the Proctor [the university police] and stammers out that “he was only just finishing a cigar”. “Oblige me, sir,” said the Proctor, “by informing me who began it”.’ And there are oddities he appreciated, such as the inscription he’d seen on a barber’s shopfront: ‘Hair scientifically cut, and mathematically arranged.’

For someone like Edward, who so clearly relished his studies and college life generally, the logical next step, once he had graduated, was to become a Fellow. This would entail making a binding commitment: in an age when higher learning and religion were still intertwined, any undergraduate who sought a Fellowship was required to take Holy Orders within ten years of their graduation. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that in his ledger book Edward should have transcribed ruminations on the nature of God (‘A God understood would be no God at all’), and that he should have included paragraphs with headings such as ‘Preaching and Praying’, ‘Pantheism’, ‘Scepticism’ and ‘Reflections on Anglican and Roman Catholic Differences’, and made notes on the use of wax lights in ritual, and meditations on faith, superstition and immortality.

But there was also another, more intrusive condition for a prospective Fellow. He had to commit to a vow of celibacy. Up until several decades later, only the President of the college was permitted to marry.

Which makes it intriguing, in view of the future course of his life, that I find Edward has taken the trouble to copy out a poem by the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell, entitled ‘The Maid’s Remonstrance’.

Never wedding, ever wooing, Still a love-lorn heart pursuing, Read you not the wrong you’re doing In my cheek’s pale hue?

All my life with sorrow strewing, Wed, or cease to woo.

Had Edward got himself into a similar situation?

Another poem that is constantly revisited in his notebook is ‘The Princess’, a lesser-known work by Alfred Tennyson. Its overall themes are the underestimated strength of women, and the poor provision for their education. But the two passages he’s picked out, about love and loss, suggest that celibacy is not going to be an easy path for Edward.

Dear as remembered kisses after death, And sweet as those by hopeless fancy feigned On lips that are for others; deep as love, Deep as first love, and wild with all regret;

O Death in Life, the days that are no more.

And later:

She ended with such passion that the tear She sang of, shook and fell, an erring pearl Lost in her bosom.

This esoteric collection of his thoughts on politics, history, literature, as well as theology, put together between 1849 and 1853, paints a portrait of a young man with a broad mind and wide-ranging curiosity, but also suggests the temptations that he knew he had to overcome as he prepared to dedicate himself and the rest of his life to God and the college.

They show, in addition, that even as he prepared to commit himself wholly to the donnish life, he was still considering other avenues. Reproduced towards the end of the ledger are some twenty references he assembled to help him procure the headmastership of Durham School.

Dr Wynter, the President of St John’s, talks of ‘the high opinion I entertain of Mr Palin’s merits as a gentleman and a scholar’. The Revd Warburton, Assistant Inspector of Schools, has ‘high esteem for him as a teacher, which is shared by all those who have come under his infl uence as his pupils’. Mr Neate, a Senior Fellow of Oriel, has ‘formed a very high opinion of his disposition, principle, and more especially of his great aptitude for gaining the respect and affection of the young’. The Revd Bellamy, his old headmaster at Merchant Taylors’ School, recommends his ‘scholarship, temper, industry and facility for communicating knowledge’, while the Revd Mansel

notes the ‘zealous discharge of his sound but not extreme theological opinions’.

Despite this avalanche of academic support he failed to get the job. And that decided him: he would take Holy Orders and remain with the college. The same year, 1853, he was ordained a deacon of the church by Samuel Wilberforce (son of the anti-slavery campaigner William), and two years later, after undertaking the Rites of Ordination, he was admitted to the priesthood.

Privately, though, he admitted in his ledger book that it had not been an easy decision and that he had doubts as to his suitability for the role he had now elected to take on. Contrasting himself with ‘the spotless ones’, he wrote, ‘I have to thank God who has counted me faithful, putting me into the Ministry who before was a blasphemer and a persecutor and injurious.’ ‘From my youth up,’ he went on, ‘the mercy of God has never left me quite to myself, but in my most distant wanderings has been over me.’ He touched cryptically on a three-week stay the previous year at the Ehrenbreitstein Hotel in Koblenz when ‘reflection was forced upon me in moments of an unavoidable seclusion’. He noted, equally mysteriously, that ‘illness at Amsterdam threw me upon myself and impressions deepened and resolutions were taken’.

Now, though, Edward had set his course as a churchman and a Fellow. He had committed himself to a future at Oxford. He acquired a reputation as a tough examiner, earning the nickname ‘Plough Palin’ – a reference to his merciless sinking of the hopes of those who didn’t come

up to standard (palin being the Greek word for ‘again’). And he threw himself enthusiastically into the life of the college and of the university.

A search of Edward’s battels, the accounts of college expenses, reveals that he lived on the premises right through until 1865. This was probably because he was a more active participant in college aff airs than many of his colleagues, lecturing and overseeing exams and taking on for a while the administrative duties of Senior Bursar. To this end he would have had a ‘set’ of rooms, consisting of a bedroom as well as a study for conducting tutorials and entertaining fellow dons. It would have been a congenial existence in what was in many ways more a glorified club than a strict and sheltered community. Among his colleagues would have been tennis players, bridge players, debaters, musicians, card players, actors and, doubtless, a few cads. In a revealing photograph of Edward at Oxford, in which he is shown standing with a group of Fellows in an Oxfordshire garden, he – smaller than most of them and with thick dark hair – looks trim, neat, somehow contained. His dress, and that of those around him, however, is quite informal, with no sign of the long gowns and mortar boards more usually associated with college life.

In 1859, with six celibate years at the heart of college life behind him, Edward set out on his annual walking holiday in Switzerland. He kept an account of his travels in a black leather-covered notebook. From the very first page

it’s clear that he couldn’t help noticing what he was not allowed to have.

He’d barely left Oxford before noting that ‘at dinner off Southend’ he ‘made acquaintance with two young German ladies’. One was a Miss Gebhard, off to stay with her aunt in Worms. Edward wrote in his diary that she was a very nice person, and spoke English. He didn’t catch the name of her companion, which I think he would have liked to have done, as ‘she was a tall beautiful girl’, a governess with a family called Preston, from Lowestoft. Both girls, it seems, were the nineteenth-century equivalent of au pairs.

‘The sea,’ he reports, ‘was delightfully calm, and everybody seemed to enjoy themselves. I did, I know.’ After he had ‘slept like a top’, he went up on deck at 5.30 in the morning to an unexpected bonus. ‘I found my young lady no. 2 already there.’ Fog – fortuitously for him, perhaps – delayed the arrival of the ferry. However, eventually the skies cleared and ‘another roastingly hot day’ began. Even so, they were almost twelve hours late docking at Rotterdam.

Edward had booked his passage on a riverboat down the Rhine, as far as Mannheim, but, when he found out how long this might take, ‘I tore up my ticket and left the boat for the Rail.’ This, coincidentally, allowed him time to escort ‘my two fair German friends’ to their accommodation at the New Bath Hotel (previous guests included the architect Sir John Soane, who has left us a sketch of the room he and his wife occupied when they stayed at the hotel in 1835). Having seen them safely installed, Edward set off, on foot, for the railway station.

Soon another young lady crossed his path. ‘Found a young person going some distance same way as myself named Goodman – travelled together, she had been a governess in a family at St. Petersburg and was going into the household of an Amsterdam banker with a country house at Ede, two stations from Arnhem.’ He took a paternal interest in Miss Goodman. ‘Poor young thing!’ he noted. ‘She was in an utterly strange country and seemed badly cast down.’ When they reached Ede, she was met by what Edward surmised might be her future mistress. ‘A woman with a loud voice, but not, I hope for poor little Miss Goodman’s sake, a hard heart.’

On Edward went, constantly falling in with strangers as he did so. At ‘Brugg’ he met an Englishman, travelling with his daughter (‘such a charming little maiden’). As he made his way further into Switzerland he met a young gentleman in the hardware business at St Gall who ‘expressed a great desire to see Sheffield’. At St Gall, a group of schoolchildren embarked and ‘kept up all the way the celebrated Appenzell musical howl’. Rather than cover his ears, he described it most approvingly: ‘Besides being singular it was very melodious.’

The further he travelled from his academic responsibilities, the sunnier his mood became. One doesn’t have to look far for one source of his rising spirits. At Ragatz, for example, where his lodgings were ‘picturesquely situated’ opposite some flour and sawmills, he was delighted by ‘a bouncing Swiss damsel by the name of Francisca’ who ‘carries my tub full of water as easily as if it were a feather’. At other times he drew pleasure from long,