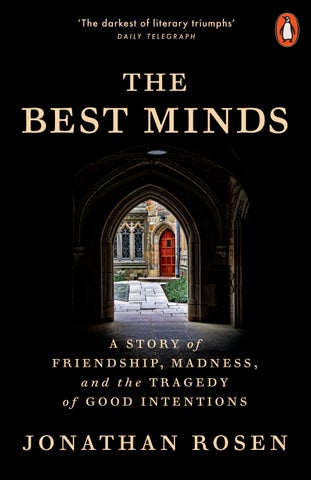

‘The darkest of literary triumphs’ daily telegraph

THE BEST MINDS

A STORY of FRIENDSHIP, MADNESS, and the TRAGEDY of GOOD INTENTIONS

JONATHAN ROSEN

THE BEST MINDS

‘Brave and nuanced . . . Effectively taking over his friend’s unfinished project, braiding it with his own story of clinical anxiety as well as skeins of history, medicine, religion and true crime, the author has transcended childhood rivalry by twinning their stories, an act of tremendous compassion and a literary triumph’ The New York Times

‘A memoir of boyhood friendship, a passionate critique of the failure of American mental health policy and a devastating story of human tragedy . . . his literary imagination shapes the book like a novel . . . This artful, reflective and even entertaining book – one of the best of this or any year – is his powerful effort to take responsibility for changing minds, to persuade us of the danger of allowing compassion to obscure truth. The Best Minds manages to honour both’ Elaine Showalter, TLS

‘Immensely emotional and unforgettably haunting’

Richard J. McNally, Wall Street Journal

‘The darkest of literary triumphs, and the most gripping of unbearable reads. Five stars’ Simon Ings, Daily Telegraph

‘An astounding piece of work, at once a portrait of Laudor made of countless fine brush strokes, a tender memoir of adolescence and young adulthood and, above all, a forensic, unflinching exploration of the factors that led to Laudor’s public rise and bloody fall’ Ben Machell, The Times

‘Extraordinary . . . It’s just so superbly written. I highly recommend it’ Nihal Arthanayake, Radio 5 Live

‘Could be the best book of the year . . . Jonathan Rosen’s The Best Minds takes its title from Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, and could end up as just as enduring a work of American writing. A memoir, a love letter, and a biblical tragedy all at once, it avoids easy answers but clings to difficult questions. A tale told with humility, it charts the path to hell by noting every good intention along the way’ New York Sun

‘A beautifully written meditation on society’s inability to cope with the problem of mental illness’ Gal Beckerman, Atlantic

‘Like all great American texts it is the detail and the flow of ideas that gives it power. This is social and intellectual history of the most powerful sort’ Brian Morton, The Tablet

‘This book gets you in its grip from the first pages. It is the opposite of a magic trick: nothing is hidden but the revelations are constantly stunning, a testament to Jonathan Rosen’s sheer skill as an author. The Best Minds is a heartbreaking story and an astonishing work of art, its tragedy rendered with unbounded humanity and depth’ Stephen J. Dubner

‘Far and away the best book I’ve read this year’ Bari Weiss

‘A work of intimacy, scope and sweeping power, this epic book reads like a classic American novel. Both a heart-rending tragedy and a story of love and companionship, The Best Minds is utterly compelling’ Seán Hewitt

‘This is that rare book that deftly works on several levels at once while remaining a compulsive read . . . Jonathan Rosen writes with searing intelligence and admirable candor about his role in what is ultimately a heartrending story. As unobtrusively researched as it is deeply reflective, informed by a humane and comprehending voice, The Best Minds delivers on its own vaulting ambition. It is nothing short of a contemporary masterpiece’ Daphne Merkin

‘I am not sure when I last read a nonfiction book as satisfying as The Best Minds. It’s a memoir, a medical mystery, the story of a close male friendship, a clear-eyed look at the criminal justice system, and, in a weird way, an academic satire, revealing Ivy League foibles that would make you laugh if they didn’t make you tear your hair out, painfully. Jonathan Rosen has written a long book that felt too short; I wanted it to keep going and going’ Mark Oppenheimer

‘The book is a kind of lighthouse, pointing out the dangers ahead if we don’t pay attention to those small number of people with severe mental illness, who pose a risk to others, and who need long term care from professionals: not from desperate families and partners . . . The Best Minds has its own strange and terrible beauty, and despite the tragedy described therein, it is also a tribute to human love and hope for better things’ Gwen Adshead

‘A riveting narrative . . . The Best Minds is not only about genius and madness. It is about how all of us approach what we can’t understand and how each of must do better for those who can’t fend for themselves’ Thomas Insel

Jonathan Rosen is the author of two novels: Eve’s Apple and Joy Comes in the Morning, and two non-fiction books: The Talmud and the Internet and The Life of the Skies. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic and numerous anthologies. He lives with his family in New York City.

The Best Minds

The Best Minds

A STORY OF FRIENDSHIP, MADNESS, AND THE TRAGEDY OF GOOD INTENTIONS

A STORY OF FRIENDSHIP, MADNESS, AND THE TRAGEDY OF GOOD INTENTIONS

Jonathan Rosen Q

Jonathan Rosen Q

ALLEN LANE an imprint of PENGUIN BOOK S

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Published in the United States by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York 2023

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024

001

Copyright © Waxwing, LLC, 2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–1–802–06325–7

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

In memory of Robert and Norma Rosen

May their memory be a blessing

הכרבל םנורכז

And for Anna Rosen sister, savior, friend

I call to the mysterious one who yet

I call to the mysterious one who yet

Shall walk the wet sands by the edge of the stream

Shall walk the wet sands by the edge of the stream

And look most like me, being indeed my double, And prove of all imaginable things

And look most like me, being indeed my double, And prove of all imaginable things

The most unlike, being my anti-self

The most unlike, being my anti-self

W B Y, “Ego Dominus Tuus”

W B Y, “Ego Dominus Tuus”

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

207

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN • MAKING ILLNESS A WEAPON 220

CHAPTER

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN • UNDERCLASS 228

CHAPTER NINETEEN • HALFWAY 237

CHAPTER

CHAPTER TWENTY- ONE • MENTORS 269

CHAPTER TWENTY- TWO • PRECEDENT 280

CHAPTER TWENTY- THREE • SECRETS 286

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER TWENTY- FIVE • HAPPY IDIOT 311

CHAPTER TWENTY- SIX • POSTDOC 317

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER TWENTY- SEVEN • THOUGHTFUL ENABLING 327

CHAPTER TWENTY- EIGHT • CAREER KILLER 337

CHAPTER TWENTY- NINE • ROLE MODEL 345

CHAPTER THIRTY • TWICE BORN 354

CHAPTER THIRTY- ONE • CREATIVITY, INC. 364

CHAPTER THIRTY- TWO • MICHAEL CALLED KEVIN 374

CHAPTER THIRTY- TWO • MICHAEL CALLED KEVIN 374

CHAPTER THIRTY- THREE • SHAMANS 382

CHAPTER THIRTY- THREE • SHAMANS 382

CHAPTER THIRTY- FOUR • EQUAL OPPORTUNITY 394

CHAPTER THIRTY- FOUR • EQUAL OPPORTUNITY 394

CHAPTER THIRTY- FIVE • THE BACKWARD JOURNEY 405

CHAPTER THIRTY- FIVE • THE BACKWARD JOURNEY 405

CHAPTER THIRTY- SIX • THE TWO ADAMS 416

CHAPTER THIRTY- SIX • THE TWO ADAMS 416

CHAPTER THIRTY- SEVEN • PERSONAL EMERGENCY 426

CHAPTER THIRTY- SEVEN • PERSONAL EMERGENCY 426

CHAPTER THIRTY- EIGHT • GOING BACK 434

CHAPTER THIRTY- EIGHT • GOING BACK 434

CHAPTER THIRTY- NINE • THE FATAL FUNNEL 437

CHAPTER THIRTY- NINE • THE FATAL FUNNEL 437

CHAPTER FORTY • CAIN AND ABEL 450

CHAPTER FORTY • CAIN AND ABEL 450

CHAPTER FORTY- ONE • THE ETERNAL OPTIMIST 466

CHAPTER FORTY- ONE • THE ETERNAL OPTIMIST 466

CHAPTER FORTY- TWO • ENDINGS 474

CHAPTER FORTY- TWO • ENDINGS 474

EPILOGUE • NO GOING BACK 492

EPILOGUE • NO GOING BACK 492

Acknowledgments 525

Acknowledgments 525

A Note on the Sources 531

A Note on the Sources 531

Index 541

Index 541

Part I

The House on Mereland Road

It is an illusion that we were ever alive, Lived in the houses of mothers, arranged ourselves By our own motions in a freedom of air.

—W S , The Rock Q

IIam going back fifty years. Before the lurid headlines, the Hollywood deal, the publishing contract, and The New York Times profile of the role model genius who finished Yale Law School against all odds. Before delusions mistaken for stories, and stories mistaken for life. Before the fancy clothes you bought for management consulting and wore into the hospital, the halfway house, and the Gatsby House you guarded with a baseball bat against enemies disguised as friends and family, guarded in turn by beloved neighbors.

am going back fifty years. Before the lurid headlines, the Hollywood deal, the publishing contract, and The New York Times profile of the role model genius who finished Yale Law School against all odds. Before delusions mistaken for stories, and stories mistaken for life. Before the fancy clothes you bought for management consulting and wore into the hospital, the halfway house, and the Gatsby House you guarded with a baseball bat against enemies disguised as friends and family, guarded in turn by beloved neighbors.

I am going back to the time before you graduated from Yale summa cum laude, which I always thought of as summa cum Laudor, since you achieved in three years what I failed to accomplish in four. Before high school, where you ran while I was beaten, and the horror twenty years later when it was my turn to run.

I am going back to the time before you graduated from Yale summa cum laude, which I always thought of as summa cum Laudor, since you achieved in three years what I failed to accomplish in four. Before high school, where you ran while I was beaten, and the horror twenty years later when it was my turn to run.

I am on a road racing backward out of a tragic sorrow whose circles radiate in all directions. Forgive me. I know there is no road and it isn’t racing backward. Or forward. I know there is no going back.

I am on a road racing backward out of a tragic sorrow whose circles radiate in all directions. Forgive me. I know there is no road and it isn’t racing backward. Or forward. I know there is no going back.

But here I am on a short street in New Rochelle. There is a green-andwhite colonial house at the top of the hill and a brown-and-white Tudor house at the bottom. There are two ten-year-old boys who live in those houses. Even now. They’re just illusions but they’re also real. And they’re where I’ve got to start.

But here I am on a short street in New Rochelle. There is a green-andwhite colonial house at the top of the hill and a brown-and-white Tudor house at the bottom. There are two ten-year-old boys who live in those houses. Even now. They’re just illusions but they’re also real. And they’re where I’ve got to start.

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER ONE

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

When you were a small boy, the aim of the suitable playmate could not have been more perfectly fulfilled: across the street was Michael Laudor, the ideal friend. A brilliant peer.

When you were a small boy, the aim of the suitable playmate could not have been more perfectly fulfilled: across the street was Michael Laudor, the ideal friend. A brilliant peer.

—C O , letter to the author

—C O , letter to the author

MMy family moved to New Rochelle in 1973. There were good schools, green lawns, and quaint signs painted in the 1920s bearing legends like - and , , though there were four synagogues and Metro North got you to Manhattan—the rock around which all life revolved—in thirty-three minutes. But the real reason we moved to New Rochelle was so that I could meet Michael.

That, at least, is what my mother’s best friend, the writer Cynthia Ozick, told me:

y family moved to New Rochelle in 1973. There were good schools, green lawns, and quaint signs painted in the 1920s bearing legends like - and , , though there were four synagogues and Metro North got you to Manhattan—the rock around which all life revolved—in thirty-three minutes. But the real reason we moved to New Rochelle was so that I could meet Michael. That, at least, is what my mother’s best friend, the writer Cynthia Ozick, told me:

I heard much of Michael Laudor when you were growing up. And in a way even before you knew of his existence, in this sense: that Michael, or someone like him, was always the goal in choosing where to buy a house.

I heard much of Michael Laudor when you were growing up. And in a way even before you knew of his existence, in this sense: that Michael, or someone like him, was always the goal in choosing where to buy a house.

Michael, in other words, was inevitable. I was destined to meet him, or at least someone like him, because friendship cannot actually be foretold any more than madness or the day of your death. Can it?

Michael, in other words, was inevitable. I was destined to meet him, or at least someone like him, because friendship cannot actually be foretold any more than madness or the day of your death. Can it?

THE BEST MINDS

I met Michael soon after we moved in, as I was examining a heap of junk that the previous owners had left in a neat pile at the edge of our lawn. I was looking for relics of the three athletic boys who had lived there, and wondering if a small aquarium was worth salvaging, when a boy with shaggy red-brown hair and large tinted aviator glasses walked over to welcome me to the neighborhood.

I met Michael soon after we moved in, as I was examining a heap of junk that the previous owners had left in a neat pile at the edge of our lawn. I was looking for relics of the three athletic boys who had lived there, and wondering if a small aquarium was worth salvaging, when a boy with shaggy red-brown hair and large tinted aviator glasses walked over to welcome me to the neighborhood.

He was taller even than I was, gawky but with a lilting stride that was oddly purposeful for a kid our age, as if he actually had someplace to go. His habit of launching himself up and forward with every step, gathering height in order to achieve distance, was so distinctive that it earned him the nickname Toes.

He was taller even than I was, gawky but with a lilting stride that was oddly purposeful for a kid our age, as if he actually had someplace to go. His habit of launching himself up and forward with every step, gathering height in order to achieve distance, was so distinctive that it earned him the nickname Toes.

I didn’t learn he was called Toes until fifth grade started, when I learned he was also called Big. The shortest kid in class was called Small, and when they lined us up in height order, Big and Small were bookends. Sensitive teachers sometimes let the short kids go first, which I’m sure did wonders for their self-esteem.

I didn’t learn he was called Toes until fifth grade started, when I learned he was also called Big. The shortest kid in class was called Small, and when they lined us up in height order, Big and Small were bookends. Sensitive teachers sometimes let the short kids go first, which I’m sure did wonders for their self-esteem.

Big is less imaginative than Toes, but how many kids get two nicknames? And Michael was big. Not big like Hal, who appeared to be attending fifth grade on the GI bill, but through some subtle combination of height, intelligence, posture, and willpower.

Big is less imaginative than Toes, but how many kids get two nicknames? And Michael was big. Not big like Hal, who appeared to be attending fifth grade on the GI bill, but through some subtle combination of height, intelligence, posture, and willpower.

In Brookline—the Boston suburb where my family had lived for three years before moving to New Rochelle—I’d been taller than all my friends, but nobody would have called me Big. I settled too easily at the bottom of myself in a shy sediment. Michael was only an inch or two taller than me, and just as skinny, but he seemed to enjoy taking up space, however awkwardly he filled it.

In Brookline—the Boston suburb where my family had lived for three years before moving to New Rochelle—I’d been taller than all my friends, but nobody would have called me Big. I settled too easily at the bottom of myself in a shy sediment. Michael was only an inch or two taller than me, and just as skinny, but he seemed to enjoy taking up space, however awkwardly he filled it.

Even standing still he had a habit of rocking forward and rising up on the balls of his feet, trying to meet his growth spurt halfway. He stood beside me on Mereland Road in that unsteady but self-assured posture, rising and falling like a wave. He was socially effective the same way he was good at basketball—through uncowed persistence.

Even standing still he had a habit of rocking forward and rising up on the balls of his feet, trying to meet his growth spurt halfway. He stood beside me on Mereland Road in that unsteady but self-assured posture, rising and falling like a wave. He was socially effective the same way he was good at basketball—through uncowed persistence.

I often heard in later years that people found him intimidating,

I often heard in later years that people found him intimidating,

but for me it was the opposite. Despite my shyness— or because of it—Michael’s self-confidence put me at ease. Perhaps because I was conscious of the awkwardness that he overcame, or simply refused to recognize, I fed off his belief in himself.

but for me it was the opposite. Despite my shyness— or because of it—Michael’s self-confidence put me at ease. Perhaps because I was conscious of the awkwardness that he overcame, or simply refused to recognize, I fed off his belief in himself.

Besides, being shy is not the same as being modest. The same expectation shaping his life was shaping mine; the belief that your brain is your rocket ship and that simply as a matter of course you are going to climb inside and blast off. Propelled by some mysterious process—never specified, almost mystical and yet entirely real—we would outsoar the shadow of ordinary existence and think our way into stratospheric success.

Besides, being shy is not the same as being modest. The same expectation shaping his life was shaping mine; the belief that your brain is your rocket ship and that simply as a matter of course you are going to climb inside and blast off. Propelled by some mysterious process—never specified, almost mystical and yet entirely real—we would outsoar the shadow of ordinary existence and think our way into stratospheric success.

Michael told me his name and my name, too, which he shortened to Jon. He liked to give the answer before the question, and offered his opinion that if the former owners had thrown out the fish tank, it probably leaked even if it didn’t look cracked. I’ve never liked having my name abbreviated but I didn’t correct him.

Michael told me his name and my name, too, which he shortened to Jon. He liked to give the answer before the question, and offered his opinion that if the former owners had thrown out the fish tank, it probably leaked even if it didn’t look cracked. I’ve never liked having my name abbreviated but I didn’t correct him.

It’s possible his mother had sent him. Ruth Laudor was a neighborly woman who came over herself at some point to welcome us— and sometimes came over to escape the roar of her own household—but Michael’s geniality and supreme self-confidence were his own. Even then, he seemed like the ambassador of his own country.

It’s possible his mother had sent him. Ruth Laudor was a neighborly woman who came over herself at some point to welcome us— and sometimes came over to escape the roar of her own household—but Michael’s geniality and supreme self-confidence were his own. Even then, he seemed like the ambassador of his own country.

It was Michael who pointed out that while my house was first on the block, it was number 11 not number 1, something I’d never have wondered about because numbers were always unpredictable, even without the “new math” that had been introduced in the sixties so we could win the Cold War. I didn’t know it was called new math, only that having been shown a decimal point in fourth grade, I was going to spend the rest of my life trying to figure out where to put it.

It was Michael who pointed out that while my house was first on the block, it was number 11 not number 1, something I’d never have wondered about because numbers were always unpredictable, even without the “new math” that had been introduced in the sixties so we could win the Cold War. I didn’t know it was called new math, only that having been shown a decimal point in fourth grade, I was going to spend the rest of my life trying to figure out where to put it.

Michael knew, and played me a song by Tom Lehrer called “New Math,” one of many songs and records we spent hours listening to in his living room. The joke of “New Math” was that it was so simple

Michael knew, and played me a song by Tom Lehrer called “New Math,” one of many songs and records we spent hours listening to in his living room. The joke of “New Math” was that it was so simple

THE BEST MINDS

“that only a child can do it,” which is to say it was a song for adults, which was part of its special pleasure. Michael never believed in the line separating children from adults, or many other lines either.

“that only a child can do it,” which is to say it was a song for adults, which was part of its special pleasure. Michael never believed in the line separating children from adults, or many other lines either.

The Tom Lehrer album was ten years old but new to me, full of names and concepts Michael cheerfully glossed—the Vatican; Wernher von Braun—that gave it an archaic but cutting-edge quality, like the Doc Savage mysteries he also introduced me to.

The Tom Lehrer album was ten years old but new to me, full of names and concepts Michael cheerfully glossed—the Vatican; Wernher von Braun—that gave it an archaic but cutting-edge quality, like the Doc Savage mysteries he also introduced me to.

Michael often seemed like someone who had lived a full span already and was just slumming it in childhood, or living backward like Benjamin Button or Merlin. My parents were amused by the speed with which he took to calling them Bob and Norma, and the unabashed way he looked them in the eye as he cursed the bombing of Cambodia or discussed the Watergate scandal while I waited for him to finish so we could play Mille Bornes or go outside. I knew the president was a crook, but Michael knew who Liddy, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman were, and what they had done, matters he expounded as if Deep Throat had whispered to him personally in the schoolyard just behind his house.

Michael often seemed like someone who had lived a full span already and was just slumming it in childhood, or living backward like Benjamin Button or Merlin. My parents were amused by the speed with which he took to calling them Bob and Norma, and the unabashed way he looked them in the eye as he cursed the bombing of Cambodia or discussed the Watergate scandal while I waited for him to finish so we could play Mille Bornes or go outside. I knew the president was a crook, but Michael knew who Liddy, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman were, and what they had done, matters he expounded as if Deep Throat had whispered to him personally in the schoolyard just behind his house.

Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School was so close, Michael told me, I could wake up fifteen minutes before the bell, eat breakfast, and still get to class on time. Michael treated the schoolyard, which had outdoor basketball hoops, like an extension of his backyard.

Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School was so close, Michael told me, I could wake up fifteen minutes before the bell, eat breakfast, and still get to class on time. Michael treated the schoolyard, which had outdoor basketball hoops, like an extension of his backyard.

I could see the roof of the school building from the window of my mother’s attic office, its ornate cupola suggesting a fancy barn or a village church. I could see Michael’s roof from my own window, screened by branches. There were only six or seven houses on the whole street. The Laudors, number 28, were diagonally across and down; a knight’s move away on a chessboard.

I could see the roof of the school building from the window of my mother’s attic office, its ornate cupola suggesting a fancy barn or a village church. I could see Michael’s roof from my own window, screened by branches. There were only six or seven houses on the whole street. The Laudors, number 28, were diagonally across and down; a knight’s move away on a chessboard.

Michael gave me a tour of the Wykagyl shopping center, two blocks from my house, where there was a store called Big Top that sold toys in the back and candy in the front, an A& P, a pizza place,

Michael gave me a tour of the Wykagyl shopping center, two blocks from my house, where there was a store called Big Top that sold toys in the back and candy in the front, an A& P, a pizza place,

8

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

and a pet shop where I could get a new aquarium. Guppies cost ten cents apiece.

and a pet shop where I could get a new aquarium. Guppies cost ten cents apiece.

Michael was the sort of guide who didn’t just point out George’s Hair Fort, he told you the names of all four Italian brothers who cut hair there. I could only ever remember Rosario, who cut my hair. He cut my father’s hair, too, and called out, Professore! when he walked in. He called Michael’s father professore too.

Michael was the sort of guide who didn’t just point out George’s Hair Fort, he told you the names of all four Italian brothers who cut hair there. I could only ever remember Rosario, who cut my hair. He cut my father’s hair, too, and called out, Professore! when he walked in. He called Michael’s father professore too.

That was something else we had in common. Our fathers were college professors, though my father taught German literature and Michael’s father taught economics. Also, my father was bald on top, with wings of white hair on either side of his head; Michael’s father had a dark pompadour combed dramatically back, like the greasers he’d grown up with on the Brooklyn waterfront.

That was something else we had in common. Our fathers were college professors, though my father taught German literature and Michael’s father taught economics. Also, my father was bald on top, with wings of white hair on either side of his head; Michael’s father had a dark pompadour combed dramatically back, like the greasers he’d grown up with on the Brooklyn waterfront.

The following year, Mr. Summa—who had given up working at the 7-Up bottling plant to become our sixth-grade teacher— started calling Michael “professor” after overhearing him use the word “epiglottis” to tell a joke about hiccups, thus giving him a third nickname.

The following year, Mr. Summa—who had given up working at the 7-Up bottling plant to become our sixth-grade teacher— started calling Michael “professor” after overhearing him use the word “epiglottis” to tell a joke about hiccups, thus giving him a third nickname.

MMichael might have been the reason my parents chose Mereland Road, but my mother’s friend Cynthia was the reason they’d chosen New Rochelle. Cynthia and my mother were both writers, with an all-consuming devotion to literature, a shared commitment to feminism, and a dark awareness of the Holocaust, the black backing of the mirror they held up to reality that made the reflected world visible. They talked on the phone every day. When they got off the phone, they wrote long letters, and when they received each other’s letters, they called, because there could never be too many words, though the written word was the only medium that truly mattered.

Cynthia lived in New Rochelle’s south end, which had been settled in the seventeenth century by Huguenots—French Protestants fleeing

ichael might have been the reason my parents chose Mereland Road, but my mother’s friend Cynthia was the reason they’d chosen New Rochelle. Cynthia and my mother were both writers, with an all-consuming devotion to literature, a shared commitment to feminism, and a dark awareness of the Holocaust, the black backing of the mirror they held up to reality that made the reflected world visible. They talked on the phone every day. When they got off the phone, they wrote long letters, and when they received each other’s letters, they called, because there could never be too many words, though the written word was the only medium that truly mattered. Cynthia lived in New Rochelle’s south end, which had been settled in the seventeenth century by Huguenots—French Protestants fleeing 9

THE BEST MINDS

the persecution of Louis XIV. Her house was in walking distance to the train station, the Long Island Sound, and a Victorian house in Sutton Manor that my mother had fallen in love with. But the neighborhood, and my mother’s dream house, were “quickly dismissed,” Cynthia told me, “because of the absence of any Jewish ambiance.” This objection came from my father. “The chief reason was to live in an area where there would be children appropriate for befriending.”

the persecution of Louis XIV. Her house was in walking distance to the train station, the Long Island Sound, and a Victorian house in Sutton Manor that my mother had fallen in love with. But the neighborhood, and my mother’s dream house, were “quickly dismissed,” Cynthia told me, “because of the absence of any Jewish ambiance.” This objection came from my father. “The chief reason was to live in an area where there would be children appropriate for befriending.”

Appropriate children lived in the north end, where Jews had been settling since the postwar boom. Rob Petrie—the fictional comedy writer played by dapper Dick Van Dyke—lived in a generic suburb called New Rochelle. Carl Reiner—the bald Jew who based The Dick Van Dyke Show on his own life but wasn’t allowed to play himself— lived in the north end of New Rochelle.

Appropriate children lived in the north end, where Jews had been settling since the postwar boom. Rob Petrie—the fictional comedy writer played by dapper Dick Van Dyke—lived in a generic suburb called New Rochelle. Carl Reiner—the bald Jew who based The Dick Van Dyke Show on his own life but wasn’t allowed to play himself— lived in the north end of New Rochelle.

So did Jerry Bock and Joe Stein, the composer and book writer of Fiddler on the Roof, a musical about a poor Jew who dreams about being a rich Jew, which was beloved by rich Jews who dreamed about being poor Jews, or at least remembered their grandparents who’d been poor Jews once themselves. The musical had closed on Broadway only two years before, after becoming a movie. Even my parents had the cast album, though my father considered it a Jewish minstrel show and my mother dismissed it as middlebrow schlock.

So did Jerry Bock and Joe Stein, the composer and book writer of Fiddler on the Roof, a musical about a poor Jew who dreams about being a rich Jew, which was beloved by rich Jews who dreamed about being poor Jews, or at least remembered their grandparents who’d been poor Jews once themselves. The musical had closed on Broadway only two years before, after becoming a movie. Even my parents had the cast album, though my father considered it a Jewish minstrel show and my mother dismissed it as middlebrow schlock.

Jews had moved to New Rochelle to escape New York City, then moved to the north end to escape the troubled parts of New Rochelle, which wasn’t a true suburb but a small city in its own right. There were housing projects as well as golf courses, and a once-thriving downtown killed by the departure of a department store whose arrival had also killed it, which was more than I could follow but was the sort of thing they talked about with knowing assurance in Michael’s house.

Jews had moved to New Rochelle to escape New York City, then moved to the north end to escape the troubled parts of New Rochelle, which wasn’t a true suburb but a small city in its own right. There were housing projects as well as golf courses, and a once-thriving downtown killed by the departure of a department store whose arrival had also killed it, which was more than I could follow but was the sort of thing they talked about with knowing assurance in Michael’s house.

The big Conservative synagogue my father wanted us to join, Beth El, had relocated from downtown to the leafier north end and

The big Conservative synagogue my father wanted us to join, Beth El, had relocated from downtown to the leafier north end and

10

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

opened its new sanctuary in 1970. Between my mother’s dream house in the south and Beth El in the north lay a patchwork of old Irish and Italian working-class neighborhoods, fancy developments, integrated middle-class neighborhoods, a moribund Main Street, and a highway-fractured zone that like the housing projects were largely Black.

opened its new sanctuary in 1970. Between my mother’s dream house in the south and Beth El in the north lay a patchwork of old Irish and Italian working-class neighborhoods, fancy developments, integrated middle-class neighborhoods, a moribund Main Street, and a highway-fractured zone that like the housing projects were largely Black.

And so instead of streets with opulent and evocative names like Sutton Manor and Echo Avenue, we moved to Mereland Road. The “mere” in Mereland must once have denoted a body of water, but for my mother the “mere” had devolved into its pedestrian homonym: nothing more.

And so instead of streets with opulent and evocative names like Sutton Manor and Echo Avenue, we moved to Mereland Road. The “mere” in Mereland must once have denoted a body of water, but for my mother the “mere” had devolved into its pedestrian homonym: nothing more.

There was no view of the water, only the blind exterior of Beth El looming over North Avenue. Designed by a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright, the building was windowless as a power station or a mausoleum but a comfort to my father, who was making peace with the Jewish observance he’d abandoned in retaliation for God’s abandonment of his parents thirty years before, when they were murdered along with one out of every three Jews in the world.

There was no view of the water, only the blind exterior of Beth El looming over North Avenue. Designed by a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright, the building was windowless as a power station or a mausoleum but a comfort to my father, who was making peace with the Jewish observance he’d abandoned in retaliation for God’s abandonment of his parents thirty years before, when they were murdered along with one out of every three Jews in the world.

Our neighborhood was called Wykagyl. The word is believed to be a corruption of an Algonquin name used by the Lenape, though it sounded vaguely Yiddish as pronounced by my father, who had erased a good deal of his accent but who still said his w ’s like v ’s. If you never understood why the Marx Brothers thought “viaduct” could be mistaken for “why a duck,” then you never heard my father say Wykagyl.

Our neighborhood was called Wykagyl. The word is believed to be a corruption of an Algonquin name used by the Lenape, though it sounded vaguely Yiddish as pronounced by my father, who had erased a good deal of his accent but who still said his w ’s like v ’s. If you never understood why the Marx Brothers thought “viaduct” could be mistaken for “why a duck,” then you never heard my father say Wykagyl.

Our next-door neighbor, Mr. Fruhling, a refugee from Germany who made me squeeze his eighty-year-old bicep (rock hard, he used dumbbells), also said his w ’s like v ’s. So did his tough, tiny sister, who lived in the house with him. So did Harry Gingold, a Holocaust survivor from Poland who lived one street over and gave out the honors at Beth El during Sabbath services, sidling up to congregants and

Our next-door neighbor, Mr. Fruhling, a refugee from Germany who made me squeeze his eighty-year-old bicep (rock hard, he used dumbbells), also said his w ’s like v ’s. So did his tough, tiny sister, who lived in the house with him. So did Harry Gingold, a Holocaust survivor from Poland who lived one street over and gave out the honors at Beth El during Sabbath services, sidling up to congregants and 11

THE BEST MINDS

murmuring furtively when it was time to open the ark, as if he were giving a tip on a horse.

murmuring furtively when it was time to open the ark, as if he were giving a tip on a horse.

To my sister and me he was a comic figure, but to my father he was part of the invisible fellowship of refugees it was his soul’s secret work to gather up. My father could pinpoint an accent and locate the sorrow behind it the way Sherlock Holmes could spot a limp and account for the accident that caused it at a glance.

To my sister and me he was a comic figure, but to my father he was part of the invisible fellowship of refugees it was his soul’s secret work to gather up. My father could pinpoint an accent and locate the sorrow behind it the way Sherlock Holmes could spot a limp and account for the accident that caused it at a glance.

Once, in a coffee shop, while Michael and I played tabletop soccer with three pennies and sugar packet goalposts, my father divined the wartime history of a waitress—Romania, Paris, the Pyrenees, Spain, Palestine, the Bronx—between the ordering of dessert and the bringing of the check. Even allowing for the brewing of a fresh pot of decaf—my father’s one constant demand in life—it was an impressive performance, especially because the information wasn’t journalistically extracted but offered in telegraphic exchanges sparked by mutual recognition. As we were leaving, my father murmured, “Her whole family. Auschwitz.”

Once, in a coffee shop, while Michael and I played tabletop soccer with three pennies and sugar packet goalposts, my father divined the wartime history of a waitress—Romania, Paris, the Pyrenees, Spain, Palestine, the Bronx—between the ordering of dessert and the bringing of the check. Even allowing for the brewing of a fresh pot of decaf—my father’s one constant demand in life—it was an impressive performance, especially because the information wasn’t journalistically extracted but offered in telegraphic exchanges sparked by mutual recognition. As we were leaving, my father murmured, “Her whole family. Auschwitz.”

Michael was fascinated by such displays, and in his way had a similar impulse. Friends might notice my father had an accent, but Michael asked where he was from and how he’d gotten out of Vienna, and incorporated the information into his way of referring to my father and perhaps me. He incorporated my father’s accent, too, which he began imitating almost immediately; not with malice, but more the way you might commit someone’s telephone number to memory.

Michael was fascinated by such displays, and in his way had a similar impulse. Friends might notice my father had an accent, but Michael asked where he was from and how he’d gotten out of Vienna, and incorporated the information into his way of referring to my father and perhaps me. He incorporated my father’s accent, too, which he began imitating almost immediately; not with malice, but more the way you might commit someone’s telephone number to memory.

He did the same thing in high school when he worked for Sam and Stella, the elderly Jewish couple who owned Stellar Gifts and like my father had fled Germany after Kristallnacht. You had to be at home with the alien strangeness of such things to find it darkly amusing, as we did, that Sam and Stella sold crystal. Michael would come to see the neighborhood’s survivors as an unseen collective of righ-

He did the same thing in high school when he worked for Sam and Stella, the elderly Jewish couple who owned Stellar Gifts and like my father had fled Germany after Kristallnacht. You had to be at home with the alien strangeness of such things to find it darkly amusing, as we did, that Sam and Stella sold crystal. Michael would come to see the neighborhood’s survivors as an unseen collective of righ-

12

teous protectors, with a mystical aura born of suffering that made them a bulwark against evil.

teous protectors, with a mystical aura born of suffering that made them a bulwark against evil.

Nothing seemed further from the Manichaean struggles of the twentieth century than Mereland Road, even if Betty Friedan called suburban houses “comfortable concentration camps” in The Feminine Mystique, where she warned that housewives “are in as much danger as the millions who walked to their own death in the concentration camps.”

Nothing seemed further from the Manichaean struggles of the twentieth century than Mereland Road, even if Betty Friedan called suburban houses “comfortable concentration camps” in The Feminine Mystique, where she warned that housewives “are in as much danger as the millions who walked to their own death in the concentration camps.”

Surely such hyperbole was an indicator of how far America was from actual concentration camps, like the one where my grandfather was murdered, if it could appear in a bestselling book that came into the world the same year Michael and I did. The book lived comfortably on a family bookshelf where I peeked into it with adolescent curiosity, misled by the title.

Surely such hyperbole was an indicator of how far America was from actual concentration camps, like the one where my grandfather was murdered, if it could appear in a bestselling book that came into the world the same year Michael and I did. The book lived comfortably on a family bookshelf where I peeked into it with adolescent curiosity, misled by the title.

WWas Michael bouncing a basketball the day I met him? He often had one with him the way you might take a dog out for a walk. I’d hear the ball halfway down the block, knocking before he knocked.

as Michael bouncing a basketball the day I met him? He often had one with him the way you might take a dog out for a walk. I’d hear the ball halfway down the block, knocking before he knocked.

Even today when I hear the taut report of a basketball on an empty street, the muffled echo thrown back a split second later like the after-pulse of a heartbeat, I have a visceral memory of Michael coming to fetch me for one-on-one or H-O-R-S-E, or simply to shoot around if we were too deep in conversation for a game or I was tired of losing.

Even today when I hear the taut report of a basketball on an empty street, the muffled echo thrown back a split second later like the after-pulse of a heartbeat, I have a visceral memory of Michael coming to fetch me for one-on-one or H-O-R-S-E, or simply to shoot around if we were too deep in conversation for a game or I was tired of losing.

If you saw Michael in the air, legs splayed, elbows out, you might not think he was going to score, but he had a sort of will to power over the ball that sent it booming off the all-weather backboard and sifting through the chain mail net that hung from the rim in rusted tatters. It took me time to realize this was actually the result of hard

If you saw Michael in the air, legs splayed, elbows out, you might not think he was going to score, but he had a sort of will to power over the ball that sent it booming off the all-weather backboard and sifting through the chain mail net that hung from the rim in rusted tatters. It took me time to realize this was actually the result of hard 13

THE BEST MINDS

work. He shot baskets in the rain and when there was snow on the court and his hands were raw with cold.

work. He shot baskets in the rain and when there was snow on the court and his hands were raw with cold.

I can’t remember if Michael had a basketball with him the day he introduced himself to me. He might just as easily have had a book. He often had several tucked under one arm that he would dump unceremoniously at the base of the steel pole holding up the schoolyard basket nearest the stairs. It was always an eclectic pile: Ray Bradbury, Hermann Hesse, Zane Gray westerns. Some were “assigned” by his father, he told me, like To Kill a Mockingbird, Gideon’s Trumpet, or a prose translation of Beowulf, but they were part of the general jumble stirred in with the Dune trilogy and Doc Savage adventures.

I can’t remember if Michael had a basketball with him the day he introduced himself to me. He might just as easily have had a book. He often had several tucked under one arm that he would dump unceremoniously at the base of the steel pole holding up the schoolyard basket nearest the stairs. It was always an eclectic pile: Ray Bradbury, Hermann Hesse, Zane Gray westerns. Some were “assigned” by his father, he told me, like To Kill a Mockingbird, Gideon’s Trumpet, or a prose translation of Beowulf, but they were part of the general jumble stirred in with the Dune trilogy and Doc Savage adventures.

Thanks to Michael, I became a big fan of Doc Savage, originally published in pulp fiction magazines in the 1930s but reissued as cheap paperbacks in the ’70s. We joked about the archaic language and dated futurisms—long-distance phone calls!—but Doc Savage, charged with righteous adrenaline, formed an important part of the occult archive of manly virtues that I received secondhand from Michael, who got them wholesale from his father, grandfathers, old movies, and assorted dime novels.

Thanks to Michael, I became a big fan of Doc Savage, originally published in pulp fiction magazines in the 1930s but reissued as cheap paperbacks in the ’70s. We joked about the archaic language and dated futurisms—long-distance phone calls!—but Doc Savage, charged with righteous adrenaline, formed an important part of the occult archive of manly virtues that I received secondhand from Michael, who got them wholesale from his father, grandfathers, old movies, and assorted dime novels.

Michael read many more volumes than I did, but he was a great summarizer of plots and situations, which were all essentially the same, and it was the characters that were so appealing. We spent hours talking about Clark Savage Jr., the golden-eyed “Man of Bronze” known as Doc because he was a surgeon, though he was essentially a mortal superman trained from birth by a team of scientists who were not only “the five greatest brains ever assembled in one group” but badass characters in their own right, handpicked by Doc’s philanthropist father to raise his remarkable son.

Michael read many more volumes than I did, but he was a great summarizer of plots and situations, which were all essentially the same, and it was the characters that were so appealing. We spent hours talking about Clark Savage Jr., the golden-eyed “Man of Bronze” known as Doc because he was a surgeon, though he was essentially a mortal superman trained from birth by a team of scientists who were not only “the five greatest brains ever assembled in one group” but badass characters in their own right, handpicked by Doc’s philanthropist father to raise his remarkable son.

Doc was the strongest, smartest, bravest, best-educated, and most dangerous man in the world. He was also so good—the books called him “Christlike,” a usage Michael explained—that rather than throwing bad guys into prison to rot, he used his surgical skills to perform

Doc was the strongest, smartest, bravest, best-educated, and most dangerous man in the world. He was also so good—the books called him “Christlike,” a usage Michael explained—that rather than throwing bad guys into prison to rot, he used his surgical skills to perform

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

a “delicate brain operation” on them, eliminating their criminal inclinations and erasing all memory of their past evil so they could return to normal life.

a “delicate brain operation” on them, eliminating their criminal inclinations and erasing all memory of their past evil so they could return to normal life.

I needed Doc Savage like a vitamin supplement, starved as I was by high culture and the unintended fallout of my mother’s feminism, developed for use against an entrenched patriarchy but collaterally persuading me not simply that women were equal to men—which between my sister and mother was patently self-evident—but that male nature was itself a piggy corollary to a brutish, chauvinistic world, and that I would do well to keep aspects of my biological self, or at least my adolescence, hidden like a shameful secret. Tennis player Bobby Riggs might cheerfully call himself a male chauvinist pig— despite losing his “battle of the sexes” match to Billie Jean King in front of 50 million people the year we moved to New Rochelle—but he was the product of a different time and place. Besides, we kept kosher. Michael’s mother mysteriously kept a jar of bacon fat on the stove.

I needed Doc Savage like a vitamin supplement, starved as I was by high culture and the unintended fallout of my mother’s feminism, developed for use against an entrenched patriarchy but collaterally persuading me not simply that women were equal to men—which between my sister and mother was patently self-evident—but that male nature was itself a piggy corollary to a brutish, chauvinistic world, and that I would do well to keep aspects of my biological self, or at least my adolescence, hidden like a shameful secret. Tennis player Bobby Riggs might cheerfully call himself a male chauvinist pig— despite losing his “battle of the sexes” match to Billie Jean King in front of 50 million people the year we moved to New Rochelle—but he was the product of a different time and place. Besides, we kept kosher. Michael’s mother mysteriously kept a jar of bacon fat on the stove.

Michael and I both had book-filled houses, but Michael, who liked to quantify, spoke of thousands of volumes. So many, he told me, that books were used to prop up his house, which was sinking like Venice. To prove it, he took me down into his cluttered basement and showed me the makeshift columns his father had contrived using stacks of books and what appeared to be car jacks.

The book piles rose like stalagmites from tables, chairs, and the floor itself. They served as pedestals for the jacks, which could be ratcheted up to increase the tension against the sagging ceiling and doorframes. Michael laughed at this Rube Goldberg system, but he was proud of the fact that books were literally holding up his house, and that his ingenious father’s library was slowing its journey to the center of the earth.

Michael and I both had book-filled houses, but Michael, who liked to quantify, spoke of thousands of volumes. So many, he told me, that books were used to prop up his house, which was sinking like Venice. To prove it, he took me down into his cluttered basement and showed me the makeshift columns his father had contrived using stacks of books and what appeared to be car jacks. The book piles rose like stalagmites from tables, chairs, and the floor itself. They served as pedestals for the jacks, which could be ratcheted up to increase the tension against the sagging ceiling and doorframes. Michael laughed at this Rube Goldberg system, but he was proud of the fact that books were literally holding up his house, and that his ingenious father’s library was slowing its journey to the center of the earth.

My father sometimes took us into Manhattan and turned us loose in the giant Barnes & Noble warehouse store on Fifth Avenue and Eighteenth Street, around the corner from his office at Baruch

My father sometimes took us into Manhattan and turned us loose in the giant Barnes & Noble warehouse store on Fifth Avenue and Eighteenth Street, around the corner from his office at Baruch

THE BEST MINDS

College. Barnes & Noble was just becoming a national retail chain, but the Fifth Avenue store sold used books and was so vast it was in The Guinness Book of World Records.

College. Barnes & Noble was just becoming a national retail chain, but the Fifth Avenue store sold used books and was so vast it was in The Guinness Book of World Records.

There were miles of shelves and bins filled with paperbacks, some pristine, others missing covers and sold for the price of a guppy. There were tables of hardcovers in mint condition marked down to a dollar or two that my mother eyed with sorrow, as if I’d raided a tomb rather than found a bargain. “Remaindered” books did not earn royalties but were sold off to make room for newer and more successful arrivals. The next stop was getting “pulped,” like the horse in Animal Farm they turned into glue, literally worth less than the paper they were printed on.

There were miles of shelves and bins filled with paperbacks, some pristine, others missing covers and sold for the price of a guppy. There were tables of hardcovers in mint condition marked down to a dollar or two that my mother eyed with sorrow, as if I’d raided a tomb rather than found a bargain. “Remaindered” books did not earn royalties but were sold off to make room for newer and more successful arrivals. The next stop was getting “pulped,” like the horse in Animal Farm they turned into glue, literally worth less than the paper they were printed on.

Michael and I threw volumes haphazardly into our carts, though I concentrated on classics since I wasn’t going to read most of them anyway. That was my secret. I treated the volumes more as emblems of aspiration, placeholders shelved for future consumption that meanwhile propped up my metaphorical house. Michael, on the other hand, started reading in the bookstore and continued on the train ride home.

Michael and I threw volumes haphazardly into our carts, though I concentrated on classics since I wasn’t going to read most of them anyway. That was my secret. I treated the volumes more as emblems of aspiration, placeholders shelved for future consumption that meanwhile propped up my metaphorical house. Michael, on the other hand, started reading in the bookstore and continued on the train ride home.

EEntering Michael’s house, I was greeted by a round-breasted Indian dancer framed in the vestibule, and by a signature combination of odors— detergent, heating oil, hamburgers. Mail was piled on chairs and tabletops along with books, folded laundry, and unfolded sections of The New York Times, a familiar stew but stirred with a bigger stick.

ntering Michael’s house, I was greeted by a round-breasted Indian dancer framed in the vestibule, and by a signature combination of odors— detergent, heating oil, hamburgers. Mail was piled on chairs and tabletops along with books, folded laundry, and unfolded sections of The New York Times, a familiar stew but stirred with a bigger stick.

I often heard the Laudors before I saw them. It was hard to tell even with practice if someone was shouting in anger or simply shouting rather than climbing the stairs or turning down the stereo just to make a point. And someone was always making a point.

I often heard the Laudors before I saw them. It was hard to tell even with practice if someone was shouting in anger or simply shouting rather than climbing the stairs or turning down the stereo just to make a point. And someone was always making a point.

16

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

THE SUITABLE PLAYMATE

There were three contentious brothers, each bigger than the one before, like the Billy Goats Gruff. Michael, who was the youngest, may have been Big at school, but at home he was most likely to get butted off the bridge.

There were three contentious brothers, each bigger than the one before, like the Billy Goats Gruff. Michael, who was the youngest, may have been Big at school, but at home he was most likely to get butted off the bridge.

One of the first stories Michael told me was how his brothers had dressed him up in a Superman costume when he was little and thrown him off the roof of their old house to see if he could fly. In another version, he was already wearing the outfit and was merely persuaded to jump. Both versions ended with a broken arm, but either way he was the hero of the story— abused, perhaps, but still Superman.

One of the first stories Michael told me was how his brothers had dressed him up in a Superman costume when he was little and thrown him off the roof of their old house to see if he could fly. In another version, he was already wearing the outfit and was merely persuaded to jump. Both versions ended with a broken arm, but either way he was the hero of the story— abused, perhaps, but still Superman.

Michael celebrated his brothers along with his ability to survive them. He talked about his family with tattling amusement shot through with pride, exposing and mythologizing them all at once.

His mother, Ruth, who had a lovely voice, sometimes sang in the house, unheard, or laughed incongruously when her husband and sons hollered. What else could she do?

Michael celebrated his brothers along with his ability to survive them. He talked about his family with tattling amusement shot through with pride, exposing and mythologizing them all at once. His mother, Ruth, who had a lovely voice, sometimes sang in the house, unheard, or laughed incongruously when her husband and sons hollered. What else could she do?

I’d been raised to think of brain versus brawn, but Michael’s father was an intellectual who participated in the rough household energy. Even his name, Chuck, was a verb. Michael told me about the time his father was cutting vegetables in the kitchen when he saw a man through the window letting his dog go on the lawn. Forgetting the large knife in his hand, Chuck ran to the front door and flung it open, waving his arms and cursing. Man and dog fled.

I’d been raised to think of brain versus brawn, but Michael’s father was an intellectual who participated in the rough household energy. Even his name, Chuck, was a verb. Michael told me about the time his father was cutting vegetables in the kitchen when he saw a man through the window letting his dog go on the lawn. Forgetting the large knife in his hand, Chuck ran to the front door and flung it open, waving his arms and cursing. Man and dog fled.

Unlike my father, who favored muted Harris Tweed sport coats from Brooks Brothers, Chuck sported a black leather bomber jacket. He walked with the bouncing stride Michael had inherited, but angled for confrontation. Chuck charged at you head-on; my father preferred oblique approaches and swift exits. Even in movie theaters he liked to sit on the aisle in case he had to go to the bathroom or escape the Anschluss.

Unlike my father, who favored muted Harris Tweed sport coats from Brooks Brothers, Chuck sported a black leather bomber jacket. He walked with the bouncing stride Michael had inherited, but angled for confrontation. Chuck charged at you head-on; my father preferred oblique approaches and swift exits. Even in movie theaters he liked to sit on the aisle in case he had to go to the bathroom or escape the Anschluss. 17

THE BEST MINDS

I found the violent energy of Michael’s house thrilling. When my sister and I played Monopoly, she did not buy Park Place if I already owned Boardwalk. I left her the yellow properties because she liked them. In the Laudor house, the brothers wrote their names on items in the fridge, and someone was always shouting, “That better be there when I come back! ” or “Who drank my Dr Pepper? ” Michael was at the bottom of the food chain but could still threaten to piss in the orange juice to teach the others a lesson.

I found the violent energy of Michael’s house thrilling. When my sister and I played Monopoly, she did not buy Park Place if I already owned Boardwalk. I left her the yellow properties because she liked them. In the Laudor house, the brothers wrote their names on items in the fridge, and someone was always shouting, “That better be there when I come back! ” or “Who drank my Dr Pepper? ” Michael was at the bottom of the food chain but could still threaten to piss in the orange juice to teach the others a lesson.

There was a thunderous roar at feeding time, a feeling of eat or be eaten. Out of necessity Michael ate voluminously and at great speed. He could inhale, as he liked to say, an entire pizza. I managed at most three slices but adopted Michael’s habit of taking a bite immediately even though molten cheese adhered like napalm to the roof of my mouth and I was never sure if I was dislodging mozzarella from behind my braces or a small piece of my own seared flesh.

There was a thunderous roar at feeding time, a feeling of eat or be eaten. Out of necessity Michael ate voluminously and at great speed. He could inhale, as he liked to say, an entire pizza. I managed at most three slices but adopted Michael’s habit of taking a bite immediately even though molten cheese adhered like napalm to the roof of my mouth and I was never sure if I was dislodging mozzarella from behind my braces or a small piece of my own seared flesh.

Michael was calmer when his house was empty. He enjoyed playing host in his quiet kitchen. He had a ceremonious way of dealing slices of white bread and squares of American cheese like double hands of blackjack when he made us open-faced grilled cheese in the toaster oven that to me was the height of technological innovation, though microwaves were starting to appear in the houses of the rich, along with other futuristic marvels like answering machines and the video game Pong.

Michael was calmer when his house was empty. He enjoyed playing host in his quiet kitchen. He had a ceremonious way of dealing slices of white bread and squares of American cheese like double hands of blackjack when he made us open-faced grilled cheese in the toaster oven that to me was the height of technological innovation, though microwaves were starting to appear in the houses of the rich, along with other futuristic marvels like answering machines and the video game Pong.

We watched through the tiny glass door as the cheese blistered and rose into a blackened shell you cut away like the top of a softboiled egg, though we ate that too.

We watched through the tiny glass door as the cheese blistered and rose into a blackened shell you cut away like the top of a softboiled egg, though we ate that too.

MMichael had all four grandparents, something I’d seen only in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. I was always a little jealous at this unexpected extravagance despite our roughly equivalent lives. My father’s parents had been murdered in the Holocaust twenty years

ichael had all four grandparents, something I’d seen only in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. I was always a little jealous at this unexpected extravagance despite our roughly equivalent lives. My father’s parents had been murdered in the Holocaust twenty years

before I was born. My mother’s father had died of a brain tumor when I was two. Only my mother’s mother was left to spoil me.

before I was born. My mother’s father had died of a brain tumor when I was two. Only my mother’s mother was left to spoil me.

Michael’s grandparents did not all sleep in one bed, like Charlie’s grandparents, or even in one house, but he saw a lot of them. Like the amber tint of his aviators, they imparted a geriatric aura to his precocity. Getting out of a chair, Michael would sometimes groan like an old Jewish man, a habit borrowed from his father’s father, Max Lifshutz, who like his wife, Frieda, was born in Russia, and who ranked his days as one oy, two oy, or three oy.

Michael’s grandparents did not all sleep in one bed, like Charlie’s grandparents, or even in one house, but he saw a lot of them. Like the amber tint of his aviators, they imparted a geriatric aura to his precocity. Getting out of a chair, Michael would sometimes groan like an old Jewish man, a habit borrowed from his father’s father, Max Lifshutz, who like his wife, Frieda, was born in Russia, and who ranked his days as one oy, two oy, or three oy.

He loved to contrast his old-world grandparents, drinking tea in a glass with a sugar cube between their teeth, with his mother’s parents, assimilated Jews who had retired to a small Connecticut town where they lived like WASPs. I didn’t know what a WASP was. White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, Michael told me, a phrase he unfurled like a battle flag.

He loved to contrast his old-world grandparents, drinking tea in a glass with a sugar cube between their teeth, with his mother’s parents, assimilated Jews who had retired to a small Connecticut town where they lived like WASPs. I didn’t know what a WASP was. White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, Michael told me, a phrase he unfurled like a battle flag.

His improbably named grandfather, Henry James Gediman, known as Jim, had been an “adman” for William Randolph Hearst in the hegemonic heyday of print journalism, something Michael had a real appreciation for. During the Great Depression, while Max and Frieda were having three-oy days in outermost Brooklyn, Henry James had dined at San Simeon and met Hearst’s Hollywood mistress, Marion Davies.

His improbably named grandfather, Henry James Gediman, known as Jim, had been an “adman” for William Randolph Hearst in the hegemonic heyday of print journalism, something Michael had a real appreciation for. During the Great Depression, while Max and Frieda were having three-oy days in outermost Brooklyn, Henry James had dined at San Simeon and met Hearst’s Hollywood mistress, Marion Davies.

I’d never heard of Hearst’s California castle, his mistress, or Hearst himself, though his kidnapped granddaughter Patty was about to become famous. Michael referred to Citizen Kane, the movie Hearst’s life had inspired, so often that even though I hadn’t seen the movie I would murmur, “Rosebud,” in imitation of Orson Welles. In reality I was imitating Michael impersonating Welles pretending to be Charles Foster Kane, a movie character modeled on a real tycoon his grandfather had met long ago.

I’d never heard of Hearst’s California castle, his mistress, or Hearst himself, though his kidnapped granddaughter Patty was about to become famous. Michael referred to Citizen Kane, the movie Hearst’s life had inspired, so often that even though I hadn’t seen the movie I would murmur, “Rosebud,” in imitation of Orson Welles. In reality I was imitating Michael impersonating Welles pretending to be Charles Foster Kane, a movie character modeled on a real tycoon his grandfather had met long ago.

Though Michael was devoted to the Russian-born Max and Frieda, he was grateful to his father for changing Lifshutz to Laudor before

Though Michael was devoted to the Russian-born Max and Frieda, he was grateful to his father for changing Lifshutz to Laudor before

THE BEST MINDS

he was born. His grandparents had kept Lifshutz, and still lived in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, where his father grew up and his grandmother Frieda stuffed money into a hole in the bathroom wall until a plumber came and stole it one day. Michael told stories about “crazy”

he was born. His grandparents had kept Lifshutz, and still lived in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, where his father grew up and his grandmother Frieda stuffed money into a hole in the bathroom wall until a plumber came and stole it one day. Michael told stories about “crazy”

Frieda with such amused affection that it was a shock when he told me, years later, that she had schizophrenia.

Frieda with such amused affection that it was a shock when he told me, years later, that she had schizophrenia.

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER TWO

THE GOOD EARTH

THE GOOD EARTH

But when Quinn the Eskimo gets here Ev’rybody’s gonna jump for joy

But when Quinn the Eskimo gets here Ev’rybody’s gonna jump for joy

B D , “Quinn the Eskimo”

B D , “Quinn the Eskimo”

IIdid not learn who Norman Rockwell was until Michael and I saw Annie Hall in junior high school and heard Woody Allen accuse Diane Keaton of growing up in a Norman Rockwell painting. It was the ultimate New York put-down of all the other places where all the unfortunate people had the bad luck to be born.

did not learn who Norman Rockwell was until Michael and I saw Annie Hall in junior high school and heard Woody Allen accuse Diane Keaton of growing up in a Norman Rockwell painting. It was the ultimate New York put-down of all the other places where all the unfortunate people had the bad luck to be born.

But Rockwell himself had been born in New York City, moved to New Rochelle as a teenager, and lived there for twenty-five years. He’d established his style and launched his career in New Rochelle, found models for his paintings among the boys playing in the street, bought a vacation cottage on the water in the south end, a house and studio in the north end, sent his son Jarvis to the Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School, and even painted one of the quaint signs welcoming visitors to New Rochelle.

But Rockwell himself had been born in New York City, moved to New Rochelle as a teenager, and lived there for twenty-five years. He’d established his style and launched his career in New Rochelle, found models for his paintings among the boys playing in the street, bought a vacation cottage on the water in the south end, a house and studio in the north end, sent his son Jarvis to the Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School, and even painted one of the quaint signs welcoming visitors to New Rochelle.

In other words, Michael and I grew up in a Norman Rockwell painting. Every morning, once school started, I’d walk to the bottom of our one-block street, ring his bell, and wait for him to step groggily out from the household chaos. We’d hike up the hidden steps

In other words, Michael and I grew up in a Norman Rockwell painting. Every morning, once school started, I’d walk to the bottom of our one-block street, ring his bell, and wait for him to step groggily out from the household chaos. We’d hike up the hidden steps

THE BEST MINDS

behind his house that led to the basketball court, climb a second flight of outdoor stairs, and slip in the building through a side door that felt like a private entrance.

behind his house that led to the basketball court, climb a second flight of outdoor stairs, and slip in the building through a side door that felt like a private entrance.

One morning early in the fifth grade, Michael emerged from his house wearing a fedora and carrying a man’s jacket draped over one shoulder. Clenched between his teeth was an old-fashioned cigarette holder. He looked pleased with himself, or maybe amused by me. I was wearing a black velvet vest over a ruffled white shirt and carrying a large white feather.

One morning early in the fifth grade, Michael emerged from his house wearing a fedora and carrying a man’s jacket draped over one shoulder. Clenched between his teeth was an old-fashioned cigarette holder. He looked pleased with himself, or maybe amused by me. I was wearing a black velvet vest over a ruffled white shirt and carrying a large white feather.

Our classroom had a festive costume-party feel when we arrived. Everyone was dressed for Biography Day, prepared to give clues and answer questions. Miss Waldman had baked brownies.

Our classroom had a festive costume-party feel when we arrived. Everyone was dressed for Biography Day, prepared to give clues and answer questions. Miss Waldman had baked brownies.

When it was Michael’s turn, he commandeered Miss Waldman’s swivel chair, which she cheerfully surrendered, sitting on her desk as I wheeled him around the room. He wore his jacket cape-like over his shoulders, doffed his fedora, and raised a hand, acknowledging the adulatory multitudes.

When it was Michael’s turn, he commandeered Miss Waldman’s swivel chair, which she cheerfully surrendered, sitting on her desk as I wheeled him around the room. He wore his jacket cape-like over his shoulders, doffed his fedora, and raised a hand, acknowledging the adulatory multitudes.

Lifting his chin defiantly, Michael clamped down on the cigarette holder so that it stuck up at a sharp angle, and declaimed, “Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy —the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the empire of Japan.”

Lifting his chin defiantly, Michael clamped down on the cigarette holder so that it stuck up at a sharp angle, and declaimed, “Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy —the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the empire of Japan.”

Michael looked around in triumph, untroubled by the blank expressions. He was the most powerful man in the free world, and had just declared war. It wasn’t his problem that nobody knew who he was. Besides, Miss Waldman knew, and told the class about the president who had overcome polio and saved the country. Michael stood up stiffly, as if he really had been paralyzed, and gave Miss Waldman back her chair.

Michael looked around in triumph, untroubled by the blank expressions. He was the most powerful man in the free world, and had just declared war. It wasn’t his problem that nobody knew who he was. Besides, Miss Waldman knew, and told the class about the president who had overcome polio and saved the country. Michael stood up stiffly, as if he really had been paralyzed, and gave Miss Waldman back her chair.

Nobody knew who I was either. Even I wasn’t sure, but my mother had been so confident when she suggested Nathaniel Hawthorne, and

Nobody knew who I was either. Even I wasn’t sure, but my mother had been so confident when she suggested Nathaniel Hawthorne, and

22

THE GOOD EARTH

THE GOOD EARTH

reminded me we’d visited his house in Concord, Massachusetts, and gone to Salem, where his ancestors sent witches to the gallows, that I decided I did know. Besides, the black vest gave me an armored manly appearance, and the billowy shirt added a swashbuckling effect: a knightly pirate with a quill pen.

reminded me we’d visited his house in Concord, Massachusetts, and gone to Salem, where his ancestors sent witches to the gallows, that I decided I did know. Besides, the black vest gave me an armored manly appearance, and the billowy shirt added a swashbuckling effect: a knightly pirate with a quill pen.

It was only when I was standing before the class trying to remember The Blithedale Romance and sprouting damp sideburns that I caught a whiff of something familiar rising from my collar, or perhaps the velvet vest, filling me with horror. Perfume! Darkness scribbled before my eyes and Miss Waldman stepped forward and asked me gently to tell the class who I was. She had no idea. How could she? I had gone to school dressed as my mother.

It was only when I was standing before the class trying to remember The Blithedale Romance and sprouting damp sideburns that I caught a whiff of something familiar rising from my collar, or perhaps the velvet vest, filling me with horror. Perfume! Darkness scribbled before my eyes and Miss Waldman stepped forward and asked me gently to tell the class who I was. She had no idea. How could she? I had gone to school dressed as my mother.

Ilearned a lot walking around New Rochelle with Michael, who liked narrating the histories of people and places. The Wykagyl Country Club, a grand plantation-like building across the street from Roosevelt, was not only famous for its golf course but according to Michael still restricted. I didn’t know the word. “No Blacks or Jews allowed,” he said.

I learned a lot walking around New Rochelle with Michael, who liked narrating the histories of people and places. The Wykagyl Country Club, a grand plantation-like building across the street from Roosevelt, was not only famous for its golf course but according to Michael still restricted. I didn’t know the word. “No Blacks or Jews allowed,” he said.

I was shocked, but when I reported this to my father, he did not seem surprised. The whole country had been restricted; otherwise more of my relatives would be alive.

I was shocked, but when I reported this to my father, he did not seem surprised. The whole country had been restricted; otherwise more of my relatives would be alive.

The thought that Wykagyl Country Club might not want us made sneaking onto the grounds in winter all the sweeter. The sledding was great, but even pissing into the snow was a political act, another phrase Michael taught me. He considered a lot of things political acts.

The thought that Wykagyl Country Club might not want us made sneaking onto the grounds in winter all the sweeter. The sledding was great, but even pissing into the snow was a political act, another phrase Michael taught me. He considered a lot of things political acts.

Whether or not the country club was still excluding Jews in 1973, the rest of Wykagyl had clearly unlocked its door. Even the stone church next to Roosevelt, with its tiny Huguenot burial ground, had become an Orthodox synagogue. Converted in the 1960s, the synagogue had

Whether or not the country club was still excluding Jews in 1973, the rest of Wykagyl had clearly unlocked its door. Even the stone church next to Roosevelt, with its tiny Huguenot burial ground, had become an Orthodox synagogue. Converted in the 1960s, the synagogue had 23

THE BEST MINDS