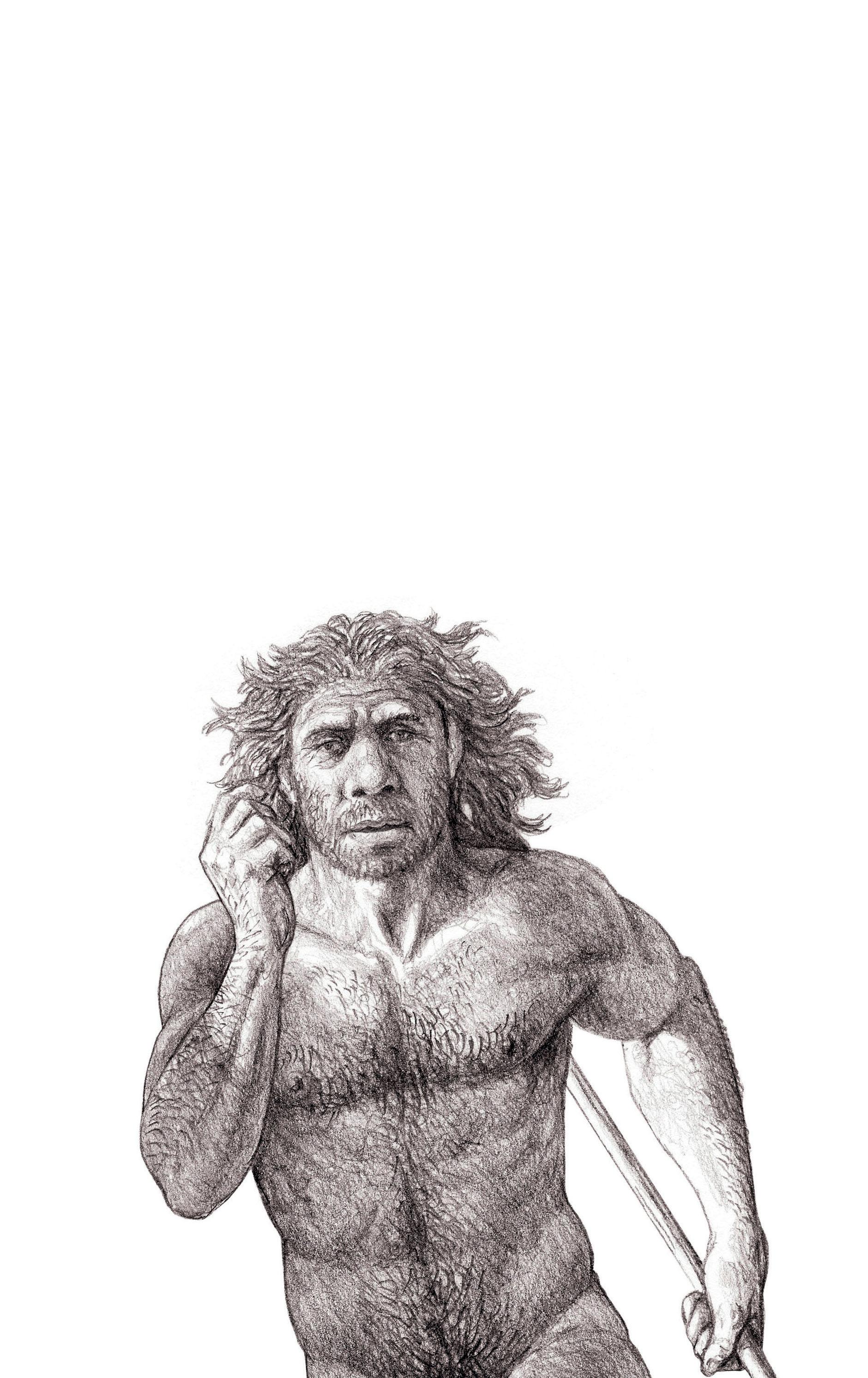

‘With the style of a poet and imagination of a philosopher, Ludovic Slimak probes the minds of Neanderthals’ steve brusatte

‘With the style of a poet and imagination of a philosopher, Ludovic Slimak probes the minds of Neanderthals’ steve brusatte

books

‘Intriguing . . . Ludovic Slimak finds unique insights through an exhaustive excavation he conducted of a rock shelter in France – a Rosetta Stone of the Neanderthal world . . . The Naked Neanderthal sets out to free this extinct species of the prejudices we have imposed – and, as such, is a resounding success’ Alison George, New Scientist

‘Vivid, refreshing . . . Absorbing, elegantly written and sometimes mischievously humorous . . . provocative critiques of tendencies to interpret Neanderthals as the intellectual and creative cousins of Homo sapiens. Instead, he argues, they are stranger to us than people might admit, with a culture that is both sophisticated and alien . . a wealth of useful, up-to-date information and debate’ Nature

‘An exhilarating contemplation of human otherness . . . Clear explications of scientific concepts, lively commentary on the implications of competing ideas, and engaging storytelling describing the pursuit of knowledge by dedicated investigators bring a startling picture of an alternate humanity into view . . Also excellent is the author’s broader discussion of how our own human prejudices have limited our appreciation of the Neanderthals’ achievements, a perceptual blindness he convincingly relates to modern forms of racism. Slimak shows how we have much more to learn about ourselves by studying “exotic sensibilities” and more fully acknowledging “our nature not as humanity but as a humanity”’ Kirkus Reviews

‘With the style of a poet and imagination of a philosopher, Ludovic Slimak probes the minds of Neanderthals, our closest cousins. All too often Neanderthals are envisioned as either prehistoric brutes or full humans, but Slimak argues that they were something unique, a species that developed their own forms of consciousness and intelligence. In an age of artificial intelligence, this fun and provocative book is a reminder that we still have a lot to learn about biological intelligence’ Steve Brusatte, author of The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs

‘A thrilling, bracing and scholarly introduction to modes of being and of paying attention to the world which are both akin to ours and importantly and revealingly different. We need urgently to consider less dysfunctional ways of occupying the cosmos and our own heads. The Neanderthals, speaking movingly and iconoclastically through Slimak, might be able to help’ Charles Foster, author of Being a Beast

‘Ludovic Slimak provides a remarkable and well-informed account of the many facets of the lost Neanderthals. It shows us what it means to be human and allows us to better imagine what extraterrestrials might be like’ Avi Loeb, author of Extraterrestrial

‘Who were the Neanderthals, and what do we really know about their artefacts and tools, customs and culture? An eye-opening and refreshing account, full of surprising revelations and personal reflections from a researcher who has spent thirty years coming face-to-face with another human species’ Lewis Dartnell, author of Being Human

‘A fascinating, immensely enjoyable read by a brilliant and original thinker who has dedicated his working life to studying Neanderthals’ Jonathan Kennedy, author of Pathogenesis

‘Roaming through caves, digging through earth and rocks, and unearthing fossils, this adventurous, bearded archaeologist takes us from the Arctic Circle to Mediterranean forests in his search for the famous Neanderthal. His personal quest combined with the scientific argument gives the book its real weight. The writing is lively and the author deftly uses sarcasm and shock factor’ Les Echos

‘A candid and uncompromising approach to a much-debated part of humanity’s early history . . . Slimak immerses us in the daily life of a prehistoric archaeologist . . a bold book’ L’Histoire.fr

‘Ludovic Slimak takes us on an astonishing archaeological quest . . he squarely confronts the myths surrounding this extinct species . . . This human “creature” is the Neanderthal, of course. But it’s us too, whose unexpected portrait emerges from this comparison across millennia’ Les Rencontres Philosophiques de Monaco

Ludovic Slimak is a paleoanthropologist at the University of Toulouse in France and Director of the Grotte Mandrin research project. His work focuses on the last Neanderthal societies, and he is the author of several hundred scientific studies on these populations. His research has been featured in Nature , Science , The New York Times and more. The Naked Neanderthal was published to great acclaim in France.

Translated by David Watson

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in French as Néandertal nu by Odile Jacob, 2022

This translation published by Allen Lane 2023 Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Odile Jacob, 2022

Translation copyright © David Watson, 2023

The moral right of the author and of the translator has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn : 978–1–802–06181–9

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

On 19 October 2017, the Pan-STARRS 1 telescope at the University of Hawaii detected a cake-shaped object a few hundred metres across moving at high speed away from our sun. Telescopes on all continents were immediately trained on the reball. They had to be quick about it – the strange object was travelling at more than 87 kilometres a second. This strange cake-like thing was nothing less than the rst interstellar object ever observed in our solar system. It was swiftly named Oumuamua, literally ‘ rst distant messenger’ in the Hawaiian language. Apart from its surprising shape, it revealed anomalies never before observed on similar objects such as meteorites or asteroids: it was highly but intermittently re ective, had a weak thermal emission and accelerated surprisingly quickly once it had passed close to the sun. Abraham Loeb, the director of the Institute for Theory and Computation at Harvard University, suggested in Astrophysical Journal Letters that ‘Oumuamua had been nothing less than humanity’s rst contact with an artifact of extraterrestrial intelligence’. This hypothesis was hotly debated, but it was the view of rigorous scientists in one of the top institutions in the world, and it ignited media attention around the globe.

The very hypothesis, the tiniest possibility, of an interstellar

The Naked Neanderthal visitor captures everyone’s imagination. The reason that it exerts such fascination is that it involves a form of intelligence external to humanity. A complete intelligence, fully conscious of itself and the immense complexity of material reality. But an intelligence that is not ours.

This interstellar perspective, this suggestion of distant intelligences, reminds us that we humans are alone, orphans, the only living conscious beings capable of analysing the mysteries of the universe that surrounds us. There are countless other forms of animal intelligence, but no consciousness with which we can exchange ideas, compare ourselves, or have a conversation.

These distant intelligences outside of us perhaps do exist in the immensity of space – the ultimate enigma. And yet we know for certain that they have existed in a time which appears distant to us but in fact is extremely close.

The real enigma is that these intelligences from the past became progressively extinct over the course of millennia; there was a tipping point in the history of humanity, the last moment when a consciousness external to humanity as we conceive it existed, encountered us, rubbed shoulders with us. This lost otherness still haunts us in our hopes and fears of arti cial intelligence, the instrumentalized rebirth of a consciousness that does not belong to us.

In our imaginations we create our own unsettling fantasies and form our own images of this ambiguous, disappeared humanity. However, this consciousness external to us, this extinct intelligence, has so far been de ned purely on the narrow basis of human intelligence such as we understand it in the present.

The Neanderthal is one of these distant intelligences, among many others, like the Denisovan or the odd tiny humans discovered on the island of Flores. And of all these

extinct intelligences, it is probably the most fascinating. The Neanderthals are the original ‘last savages’ that are discovered afresh by each generation, from Herodotus to Columbus, from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to the island of Bougainville, from Ishi* to the ‘gentle Tasaday’, that much fantasized Stone Age tribe which in 1971 played the enviable role of the ‘last cavemen’ in the western imagination. Each generation discovers its own ‘last savages’, and we have ours, of course. They pop up from time to time in the media, the recurring last gasp of an immense prehistory. There has been a continuous line of them over the millennia, all ful lling our dreams of lost worlds, from the Yeti and the Barmanou to the shores of Jules Verne’s mysterious geography.

The last Neanderthals take us to an unknown universe where other consciousnesses haunt abandoned wastelands. Despite our colonization of every corner of the natural world, despite our conquest of every inch of our planet, despite all our e orts to destroy natural species, these intelligences refuse to disappear. They continue to haunt our representations of the real – on its fringes, at the world’s extremities, on islets, in valleys, continents, places of refuge, scrubland, liminal spaces, rooted in an uncertain geography, vacillating between Mu and the intangible universe of Hugo Pratt’s The Celts.

Their distant testimonies tell us that the Neanderthals were never other versions of us – not brothers, not cousins – when it comes to mental structures, but an utterly di erent humanity. To approach them is to encounter a fundamentally divergent consciousness.

* ‘Ishi’ is the name of the last surviving member of the Yahi Indians of California, an unknown society that died out along with Ishi at the start of the twentieth century.

For the last thirty years I have spent a large part of my time scrabbling through earth on the oors of caves. Not any old caves, and not any old earth, but soil still haunted by the presence of Neanderthals. Thirty years hunting the creatures, squeezing into the cracks and ssures where they lived, ate, slept, encountered other humans, their own and other kinds. Or sometimes where they died. And yet, after thirty years of running my hands through that earth, the mud of those caves, I am no nearer forming a clear picture of the Neanderthals. I extracted material and analysed it, procrastinated, often came to conclusions, before realizing that my theories didn’t hang together. Especially at the beginning, since when you see the creature from afar, you have a deceptive sense that it is very obvious and very easy to understand.

The archaeologist, like the anthropologist, should force themselves to see both from near and from far, to paraphrase Claude Lévi-Strauss. But can we approach the Neanderthals from an anthropological point of view? Rousseau wondered whether the great apes were human, contrary to those who denied the humanity of ‘savages’, even though they were in fact Homo sapiens of a di erent culture. The borders of humanity have always been uncertain and indistinct, and many societies consider animals to be on a level with humans, shifting the centre of gravity, resituating humans as merely part of a whole. A whole that is in nitely more subtle than the one we can perceive by means of our social constructions alone, which arti cially remove and isolate humans from their environment. What is the place of the Neanderthal in this labyrinth? Human or creature – which will take precedence in our unconscious?

Numerous textbooks describe the salient features of this extinct humanity: the lack of chin, the receding brow, the thick brow ridge above the eyes, the brain capacity, larger than ours. Small, stocky, robust, good at making things with their hands, they shared a common ancestor with us, more than 400 millennia ago. These same textbooks will point out the remarkable musculature, or the mechanics of the ngers, which create a grip that is a little di erent from ours. They will talk about the vast territories that the Neanderthals covered, from the shores of the Atlantic to the approaches to the Altay, the vast mountains separating the west of Mongolia from the Siberian plain. And they will recount their rather sudden extinction around forty millennia ago. The closing pages of these textbooks o er often allusive conclusions about what they really were, since of course neither the shape of our skulls nor the curve of our femurs nor the position of our thumbs has ever de ned what it is that makes us human beings. And the best of these textbooks will, in their nal chapters, venture beyond the material evidence of bone morphology and tentatively confront this uncertainty.

The truth is, we have not yet been able to de ne the inner nature of this other humanity. And such is the full extent of our uncertainty that we come face to face with the unde nable nature of humankind and the other human beings with whom, for a while, we shared our planet.

Imagine you are overlooking a vast landscape from the top of a mountain. As the land stretches away into the distance beneath you, you have the feeling that you can encompass it all within a single gaze. But this landscape, seen from on high, is just an expanse of distant reliefs, sublime, picturesque, perhaps, but which tell you nothing of the people who occupy these valleys, of the streets of these villages which to you

appear no more than clumps of buildings, of how the bread in that little baker’s tastes. From up there you can see for miles but you never meet another soul. And what do you know about the smells emanating from that restaurant, of the grain of the stone in the wall of that church? As you get closer, you begin to see the labyrinths of these little villages, the narrow streets that have contained the lives and hopes of a hundred generations of humans.

But the picture is still too impressionistic, and you might conclude that this immense jigsaw puzzle of 300 millennia of human history has too many missing pieces and you need to use your imagination to ll in the gaps. But that does not capture it. The creature escapes us. The Neanderthal stubbornly remains an enigma. If you think otherwise, you can only have dipped your ngers in the mud, or searched in a half-hearted way. Researchers who talk about the creature fall into two broad categories: those who are sure they know what it was and those who have questions and doubts about its true nature. The rst category seems to be predominant, going by the titles in the major scienti c journals, which they seem to ll. The second category is much more discreet, because those who have doubts are usually more reserved in expressing themselves. It is usually this more silent type who has mud under their ngernails and who is constantly scratching around and examining the remains left by the creature. So who the hell was this Neanderthal?

How can you talk about Neanderthals if you have not explored their stone lairs, if you have not uncovered thousands of objects that they abandoned or stashed in the corners of cli s? To talk about the creature without ever seeing with your own eyes the spaces where it lived, without having tracked it for decades, like a hunter stalks his prey, is akin to talking in a

void. As a bare minimum, you need to have directly extracted evidence from these cave archives for decades in order to say anything worthwhile about this extinct humanity. To imagine that you have anything pertinent to say about it when your only encounter is through boxes in museums is nonsense in my view. Neither ints nor the skeletal traces of prey nor even rare nds of carnal remains have any meaning when encased within four white walls. To have any hope of perceiving their true signi cance, you have to handle the raw material in the caves. Go searching down the same bushy paths as they did. A few months of dilettante archaeological digging will allow you to get a taste, but without the odour, and perhaps without any real understanding of what you hope to draw from it.

A visit to Neanderthal earth cannot be a casual one, and Neanderthal life cannot be lived by proxy. Archaeologists can no more hope to understand this humanity by opening drawers in a museum than ethnologists can understand a society by looking at antique feather boas behind a sheet of glass or by consulting old black and white photo albums.

And yet we are well aware that the creature will not bend itself to our wishes and desires. As a shy humanoid, it is one of the most unfathomable creatures one could attempt to confront.

A creature a bit like the creature of Frankenstein, who, in trying to create a life, created a thing, endowed with his own consciousness, which he was no longer able to master. Unfathomable, since it is hidden in the shadows of the dead, without thoughts, without any words of its own.

Forty-two millennia after its disappearance from the world of the living, researchers, experimenters and various sorcerer’s apprentices are trying to give a voice to these vestiges of a humanity reduced to silence by biological extinction. To bring

the creature back to life from a collection of corpses. For some people this has become something of a quest, like a search for the Holy Grail. Do we have the audacity to give a voice to a vanished form of humanity, spirits with neither glass nor alphabet? What a strange, macabre game of ventriloquism.

To give voice to this dead matter, this mute thing, we have to plunge our hands in the dust of the caves. Scratch the earth, dig out millions of ints, bones, coals. But such proofs of past existence speak to us only thanks to an alchemy between reason and imagination, in the stills of our conceptions and our representations, the real petri dishes of our theories.

And there is the creature suspended from a thread, like a pendulum swinging between facts and representations, between likeness and otherness; it is us, it is other, it is us, it is other . . .

Poor creature, a disjointed puppet imprisoned in our mental games.

So who the hell was this Neanderthal, then?

For me, the creature has become something like an old travelling companion, one of those guys you walk with but at the end of the day don’t know a great deal about. I’ve been told so many times that it was basically the same as us. But was it really what we are? Good question.

I have the maddening feeling that instead of understanding the Neanderthal better as we pursue our common course, we are progressively fashioning it in our own image. The very idea that a creature with consciousness of itself could be fundamentally di erent from us revolts us. So we invent and reinvent the Neanderthal. Not that we get any clearer an image. We dress the creature up, narcissistically, like we hang clothes on a scarecrow. Having disappeared from the earth, the Neanderthal has been transformed, is still being transformed, by us into a lifeless doll. Victor Frankenstein was only an experimenter,

a precursor. We are the macabre inventors, the puppet masters of these marionettes from times gone by.

The creature looks impressive, of course, even scary sometimes, with all its accessories. You will have seen it too, if you have been paying the slightest bit of attention, dolled up by our fantasies, made up as a Flintstone in suit and tie, dragging his woman by the hair, punching his metro ticket.

Let us return to those who ‘know’ who the Neanderthal was. A hidden but nonetheless erce war is being waged in the scienti c community. On one side, those who think the Neanderthal is another us. On the other, those who think it is an archaic form of humanity, with vastly inferior intellectual capabilities. A subhuman, a quasi-human, or any other adverb that we can place before or after ‘human’ that is generally un attering, except in a Marvel comic.

It is not so much a war of ideas as a war of ideologies, in which neither camp can advance without getting more and more bogged down in the mud – and I am not talking about the mud of the caves, unfortunately. So, was the Neanderthal a human somewhere between nature and culture, or a gentleman of the caves?

In this battle of competing perspectives, the portrait that we can draw today is either too clear, too obvious, too simplied and too neat to be taken seriously, or else remarkably confusing. As we have pieced it together from the esh of different corpses, the creature itself has managed to escape us. Not as a real historical or scienti c entity but as an egregore possessing its own life. It haunts all our imaginations, including

those of researchers who are not incapable of imaginative thought. So in the last few years, in the wake of archaeological discoveries, the Neanderthal has been portrayed wearing necklaces of shells and eagle claws, playing the ute, painting cave walls, inventing technology, as an armed warrior, king of the North, a vanguard of our biological ancestors, who were still con ned in their cosy Asian and African territories.

The artist Neanderthal is set against its equally powerful opposite number, the pre-human of the woods, the troll of the ancient world. A creature of stone and moss. Two anecdotes spring to mind. In 2006, when I was doing my postdoctoral research at Stanford University, a reputable professor of anthropology gave a lecture on the Neanderthals. His talk related the cognitive capacity of Neanderthals to the characteristics of their archaic anatomy. Showing a slide of a Neanderthal skull, he commented: ‘I don’t know about you, but if I got on a plane and saw that the pilot had a head like that, I’d get o again.’ Laughter all round, a well-timed joke to catch the attention of the audience. But all jokes reveal an underlying thought, and this was not an insigni cant thought. Let me put this another way. A few years later, in Russia, I had a conversation with a leading light of the Academy of Sciences who never stopped telling me, ‘They are di erent.’ I prompted my companion to expand on this concept of di erence. The discussion went on into the small hours: ‘Ludovic, they have no soul.’

I will never be able to thank this researcher enough for saying those words. They threw a bright light on the unspoken, unconscious assumptions which underlie great swathes of our understanding of this humanity. We understand instinctively that the two concepts are irreconcilable. That we have to choose which, of the artist-painter Neanderthal and the Neanderthal of the woods, is real and which is fake. There is no

middle way between the two opposing views. Is the Neanderthal a creature of the lower depths or a genius of hidden depths?

The creature is wedged into our unconscious, and, at this stage, we have to assume that it is neither one nor the other. The Neanderthal is not a brother or a cousin. It is an object of study. The Neanderthal can’t in any case be compared with anything that is familiar to us in a world where di erence, alterity and classi cation have become more than ever taboo subjects. The creature cannot fail to be subversive. And this subversion is a challenge to our intelligence. Are we really up to facing this?

In the West, as in every traditional society, anyone who transgresses taboos is violently rejected, banished from the group.

If the Neanderthal were a humanity di erent from our own, human without being human, it would force us to transgress the deepest taboos of our society. Should we then push the boundaries of our values or should we police our thoughts and stay aligned with our values? Should we meekly direct our gaze only to that which is most comfortable, from a social point of view, to comprehend?

A need for easy answers, a certain cynicism, groupthink – all tend to lead to relativist thinking. It doesn’t matter, in the end, if the truth does not exist: it can be constructed. So let us construct it – why would we want to deal with labyrinthine truths?

This truth lies in nding a subtle de nition of the intelligence of a humanoid creature that cannot be summed up as us or even as our ancestor. A human that is perhaps not subjected to the

mental structures which de ne our very understanding of what it is to be human. Another intelligence, separated from us by hundreds of thousands of years of independent evolution. In this sense, the creature could be seen to be as distant from us as an extraterrestrial being. A distant intelligence of which we know nothing.

In archaeology, as in ethnography, only direct evidence has real value. Even if there are whole libraries dedicated to the topic, the only thing that is relevant is a direct confrontation with the remains of these populations. Could the witness here merge with his subject? That is likely. That is also the reason why the subject constantly tends to escape us, to slip through our ngers before we can get a real grasp. We have yet to perceive the creature in any tangible form in our minds. There are thousands of books which tell the story of our research, of our representations of the Neanderthal, the structure of its bones, the cartography of its sites, its technologies or its genetics – huge encyclopedias lled with facts. But beneath their scienti c veneer there is no real thought in them, no philosophy, no overview or close-up view.

If you are interested in the shape of its pelvis or the geometry of the blocks of int it used, the encyclopedias mentioned above will furnish you with more information than you can comfortably digest. But if you are trying to imagine, even super cially, what the world of these di erent humanities was like, such books will only disappoint you.

So this book is something di erent. We need to leave the libraries and go out in the eld, track the creature across its furthest- ung territories, into its rocky dens, get as close as possible, despite the temporal distance, transgress time, a little, in order to try to understand how it became extinct.

And since the subject becomes entangled with its witnesses,

I will also tell you about my own journey as a researcher and hunter of Neanderthals. You will join me on the anks of the polar Urals, where I encountered the most ancient Arctic populations; in the Rhône valley, in search of strange cannibals; or on the slopes of Mount Ventoux, the giant mountain in Provence, to discover mysterious deer hunters – who in fact hunted exclusively stags in the prime of life, a hundred millennia ago, in the vast primary forest of Europe, before the coming of the last ice age. Along the way, I will examine the Neanderthal’s view of the world and question ours. I will try to envisage its rituals of life and death. I will explore its ways of being in the world, which bring us back to our own humanity and the fragility of our own ideas. And the picture I will paint will be an original one: neither human nor ape, with its own way of being human that is not ours. These explorations, these thoughts, these discoveries, these questions, these researcher’s hesitations are an invitation to a journey. A Homeric journey of body and soul, like every true journey. A journey to a distant place, of course – it is always a long journey – but you can remain seated, or rather on all fours, in among the rocks or on the banks of large rivers where in a frozen, fossilized state we nd scenes, actions, events that speak to us of peoples far away, in both space and time. Peoples erased from our irredeemably amnesiac memories. Peoples for ever extinct.

Because there was indeed an extinction. A nal full stop. Sudden, unexpected. And there it is, in front of us, like an enigma with no clues, but a head-spinning enigma. So even humans can die out without warning? The disappearance of a

whole humanity, so near to us in time, should raise many questions. Can a humanity really become extinct?

Of all the questions I discuss here, this one is the easiest, so I answer it in these opening pages. Not only can a humanity come to an end, but this extinction is a clearly and de nitively proven fact, even though geneticists have shown that there are still Neanderthal traces in the genome of the populations who are the current occupants of their ancestral territories. But these same studies have also shown that the Neanderthal was not genetically subsumed within us: the presence of a few genes revealing interactions with our ancestors cannot be interpreted to mean that this population somehow survives. These genetic traces are the marks of distant encounters between biologically diverse populations which were probably only partially fertile. Based on these traces some have suggested that this extinction was only a relative one – a type of dilution, in other words. Such suggestions are not only scienti cally erroneous but also fundamentally specious.

Imagine for a moment that every species of wolf suddenly became extinct on earth. Farewell, Canis lupus. Now apply the theory of the genetic dilution of the Neanderthal in Homo sapiens to the case of the wolf. The result of this sulphurous alchemy would be to suggest that wolves are not really extinct since whole sections of their genes remain detectable in the genome of poodles, Canis lupus familiaris . . .

Well, the wolf has been luckier than the Neanderthal as it hasn’t become extinct, but if it had it is immediately obvious that the poodle that survived it could not seriously claim to be the descendant of its remarkable cousin.

We are the Neanderthal’s poodle. I don’t mean by that that we are the prettied-up, domesticated version of the original wild beast, but that, just as the poodle is not a survivor of the