DAVID HEPWORTH

Also by David Hepworth

1971: Never a Dull Moment

Uncommon People: The Rise and Fall of the Rock Stars

Nothing is Real: The Beatles Were Underrated and Other Sweeping Statements About Pop

A Fabulous Creation: How the LP Saved Our Lives

The Rock & Roll A Level

Overpaid, Oversexed and Over There: How a Few Skinny Brits with Bad Teeth Rocked America

Abbey Road: The Inside Story of the World’s Most Famous Recording Studio

How Rock’s Greatest Generation Kept Going to the End

WHY ROCK STARS NEVER RETIRE

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © David Hepworth 2024

David Hepworth has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

isbn

9781787632783

Text design by Couper Street Type Co.

Typeset in 11.5/15.75 pt Minion Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Joseph David Robert Hepworth

‘The older you get, the older you wanna get’ – Keith Richards

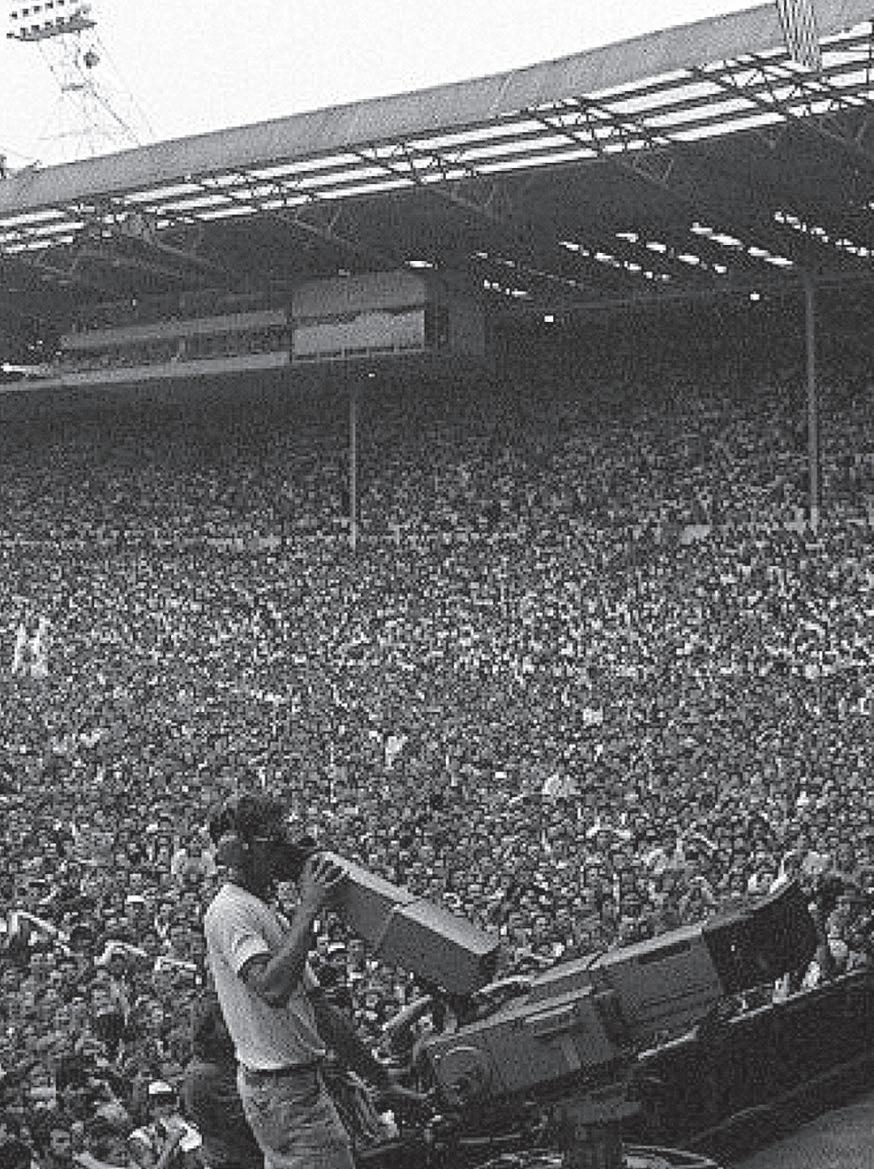

On the evening of 13 July 1985, when Paul McCartney was brought before the crowd at London’s Wembley Stadium in order to close the British end of the Live Aid fundraiser to help relieve famine in Ethiopia by singing his sixteen-year-old anthem ‘Let It Be’, he was greeted in the manner of a venerable ancient briefly stepping down from rock’s notional Mount Rushmore in order to bestow his blessing on the kids who were gathered that day, largely for old times’ sake. At the time it seemed faintly ridiculous to regard a veteran like McCartney as being in the same bracket as the relative youngsters who had planned the day. In fact he had only recently celebrated his forty-third birthday.

On 25 June 2022, when the same Paul McCartney was introduced to an even larger crowd at the Glastonbury Festival in Somerset and simultaneously to the watching millions on TV, an occasion he instigated by singing his fifty-eight-year-old composition ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ – or at least singing along with the crowd, who seemed wholly familiar with the words despite the fact that only a minority of them had been born when it was released – he was seized on as one of the few things a twenty-first-century festival audience, who

had grown up in a wilderness of specialisms and sub-cultures, could possibly be expected to agree upon. This occasion took place only a week after he had celebrated his eightieth birthday. This time there was no thought of apologizing for the years. This time the years were the point.

How did pop music, which was once supposed to be exclusively about the shock of the new, come to have such a comfortable relationship with its past? What happened between the two dates in the paragraphs above to make such a thing possible? This is what this book sets out to explore. How did the likes of McCartney and hundreds of lesser lights manage to maintain and grow their mystique into their Second and Third ages? How did we end up with rock gods in their eighties? How did they keep it up? There are thousands of volumes devoted to the subject of how your favourite artists got their big break. This one’s about how some of them managed to keep on working longer than the rest of us for the simple reason that they wanted to, and the more important reason that we wanted them to. It turned out they would be addicted to providing what we turned out to be addicted to consuming. They liked to feel young and we liked to feel that they still were. This was a two-way street. The pull was every bit as important as the push.

As he continued profitably to ply the trade he had taken up as a teenager into his seventies, Keith Richards was wont to greet audiences with the words ‘It’s good to be here – it’s good to be anywhere’ as though he recognized that his continued employment was a privilege not always available to other performers, particularly those who became famous in their youth. Keeping on keeping on is nothing like as easy for actors, and for athletes it is clearly impossible. Even the bewigged judge in London’s ancient courts, which had once been cited as an example of a job you could continue to perform well into your dotage, is now compelled to retire at the age of seventy-five. Hence it is one of the richer ironies with which this

subject is ringed that the oiks who were once arraigned before such justices for relieving themselves on garage doors or misappropriating copyrighted chord sequences gaily sailed past all the mandatory retirement ages like the bunnies who advertise batteries and continued hoovering up the cash and gliding on the thermals of acclaim long after their lordships had handed in their gavels. It turned out that there was no such statute of limitations for these formerly snake-hipped glory boys. Of all the jobs that would turn out to last a lifetime, that of rock star was by some distance the least likely.

When the eighty-year-old McCartney headlined Glastonbury he further armoured himself against any charges of being old and in the way by ensuring he was backed up by representatives of more than one generation of relative youngsters, the seventy-two-yearold Bruce Springsteen and the fifty-three-year-old spring chicken Dave Grohl. None of these veterans were having to fight for attention. They were taking advantage of the fact that their stocks appeared to have risen once again. One of the biggest music stories of July 2023 was the unexpected return to live performance of seventy-nineyear-old Joni Mitchell, who appeared to sing and play at what was supposed to be a tribute to her legacy and then promptly announced that she was so bucked by the experience she now had a taste for doing more. The eighty-two-year-old Bob Dylan had no need to return because he had clearly never gone away. Touring was now his natural condition. Tendinitis might mean that he had long since stopped playing the guitar, the keyboard behind which he was stationed on stage was making no audible contribution to the band’s sound, and he appeared to employ the microphone as much for stability as audibility, but he clearly intended to be up there on stage as long as he possibly could. As the old saying goes, being a musician is not a job, it’s an incurable disease.

This book’s intention is to consider these lions of rock in winter, to reflect on what it means to perform songs originally aimed at

xiii

wild youth in front of audiences of grandparents, to bear witness to the gradual transformation of a music which used to be exclusively for the young into the very thing it was supposed to be an alternative to, and to look at rock stars in their Third Age as closely as books like this have traditionally looked at their First. How did it all happen? How did a career which was supposed to last about as long as a boxer’s end up continuing as long as a pope’s? How did Mick Jagger, for instance, who said in his early thirties that he couldn’t possibly imagine still doing the same job at the inconceivably distant age of forty, end up performing the same function beyond the age of eighty? How did all these scrawny scourges of the establishment end up with knighthoods? How did the tie-dyed denizens of Woodstock Nation, who were once viewed as a threat to the American way of life, crown their careers by being garlanded by presidents? How did the Baby Boomers, who had used their sheer weight of numbers and their shrewd avoidance of getting involved in wars to advance the illusion that they had also invented sex, rebellion and fun, manage to remain relevant long enough to effectively write their own obituaries?

This was after all not the way anybody imagined it was going to turn out. When in 1965 the twenty-year-old Pete Townshend had put the line ‘hope I die before I get old’ in the mouth of Roger Daltrey on his anthem ‘My Generation’, nobody argued because his was clearly the generation with which they identified. By the time, thirty years later, that Keith Richards got around to observing that the older you got the older you wanted to get, the same people found themselves agreeing more fervently with the latter sentiment than they had ever done with the former. A hundred years after George Bernard Shaw had complained that youth was wasted on the young, middle-aged rock fans were turning up in their thousands to demonstrate that they appreciated its true value.

As they moved through middle age and beyond, the bands of

former boys kept going just as they had begun, for a variety of reasons, but mainly because they could. And we are the reason they could. Despite the dire predictions of our head teachers and our parents, the Baby Boomers and those who came after had the privilege of growing up without having to conform to traditional expectations. That meant we didn’t have to give up on the heroes and heroines of our teenage years. This was extremely good news for them because as we got older and waxed prosperous we had much more money to send in their direction than was ever the case when we were kids. Unlike preceding generations it seems we never put away our youthful devotion as we grew older, and as the years went by we expressed that devotion in terms ever more financially beneficial to its objects. In many ways we seemed to grow more attached to them as the years went by because they provided a kind of anchor; we preferred to think that no matter how many years they had been citizens in good standing of Planet Showbiz they still somehow stood for us; furthermore we still liked to think that if we got the chance to meet them for a drink they would warm to us every bit as much as we would warm to them. They began as our fantasy friends and they have remained the firmest of fantasy friends right to the end.

This journey was not sunny and benign for everyone. It was not always like The Golden Girls with a soundtrack provided by Martin Scorsese. Some fell by the wayside, others among thieves. The long haul was not without stresses and strains. There were unseemly squabbles between people who had been effectively shackled together since they were teenagers and now had to pretend to like each other in order to cover their grandchildren’s school fees. The tensions between the members who had big houses because their names had turned up among the writing credits and their minimum-wage mates grew more testing as time went by. Advancing years did not in any way reduce these people’s competitive nature. Very often it turned

out that a life spent in the spotlight had not in any way sated their hunger for approbation. If anything it sharpened it. It turned out that the more famous they had been, the more famous they seemed determined to remain.

And all the time the world in which they lived and moved was being roiled by change, technological and cultural, to an extent that rattled everything which had seemed certain. Like every previous generation they had lived long enough to see that things mutated again and again, but their unique position as Children of the Revolution meant that they were the only people who were precluded from mentioning it, lest they appear to be on the wrong side. They had risen to fame saying the first thing that came into their heads and found that their fame had endured into an age when the first thing that came into your head was the very last thing you allowed anywhere near your tongue. By the end of the period covered by this history a handful of them were quietly resting some of their mostloved material on the grounds that the present might find it, in the new lingua franca, ‘problematic’. The Rolling Stones were touring in 2024 but they wouldn’t be doing ‘Brown Sugar’, which, while understandable, rather made you wonder what could possibly be the point of having a Rolling Stones if they couldn’t offend somebody.

What follows, then, is a story of Rock’s Third Act. It’s an act which at the time of writing has lasted almost forty years. In that period of time many things have been turned on their heads. The past has become hip while the future seems oddly passé. The trade in pop records as physical product vanished and then re-emerged as a subdivision of the traffic in antiques. Former icons of the counter-culture have lent their names to best-selling items of confectionery. Exstreetfighting men now do their act for corporate clients in exchange for sums of money which would once have equalled a lifetime’s earnings. Songwriters have sold their catalogues to investment companies that regard old pop songs as one of the few reliable hedges

against uncertainty. The only certainties have been inverted. Former firebrands gripped and grinned with long-time fans who were surprised suddenly to find themselves heads of government. No state occasion could be considered complete without the benediction provided by a star from decades earlier turning up to recapitulate an old favourite. The Nobel Prize in Literature was handed out to an elderly man whose proud boast was that he could bash out a lyric in minutes. There were new dimensions of unlikelihood. A man of pensionable age in tight trousers was invited to perform a solo on the electric guitar from the roof of Buckingham Palace. The star turn at the most notable state funeral of our time was a piano player formerly known as Reg who went on to marry a man.

Rock’s Third Act is a story that has never been told, partly because it is still going on. Like all the best stories about rock it is simultaneously ludicrous, possessed of a strange, unquiet dignity, and has as much to say about us out there in the dark as it has about those on the other side of the red rope.

For the purpose of this telling, the story begins on Saturday, 13 July 1985. Long ago, in a vanished world.

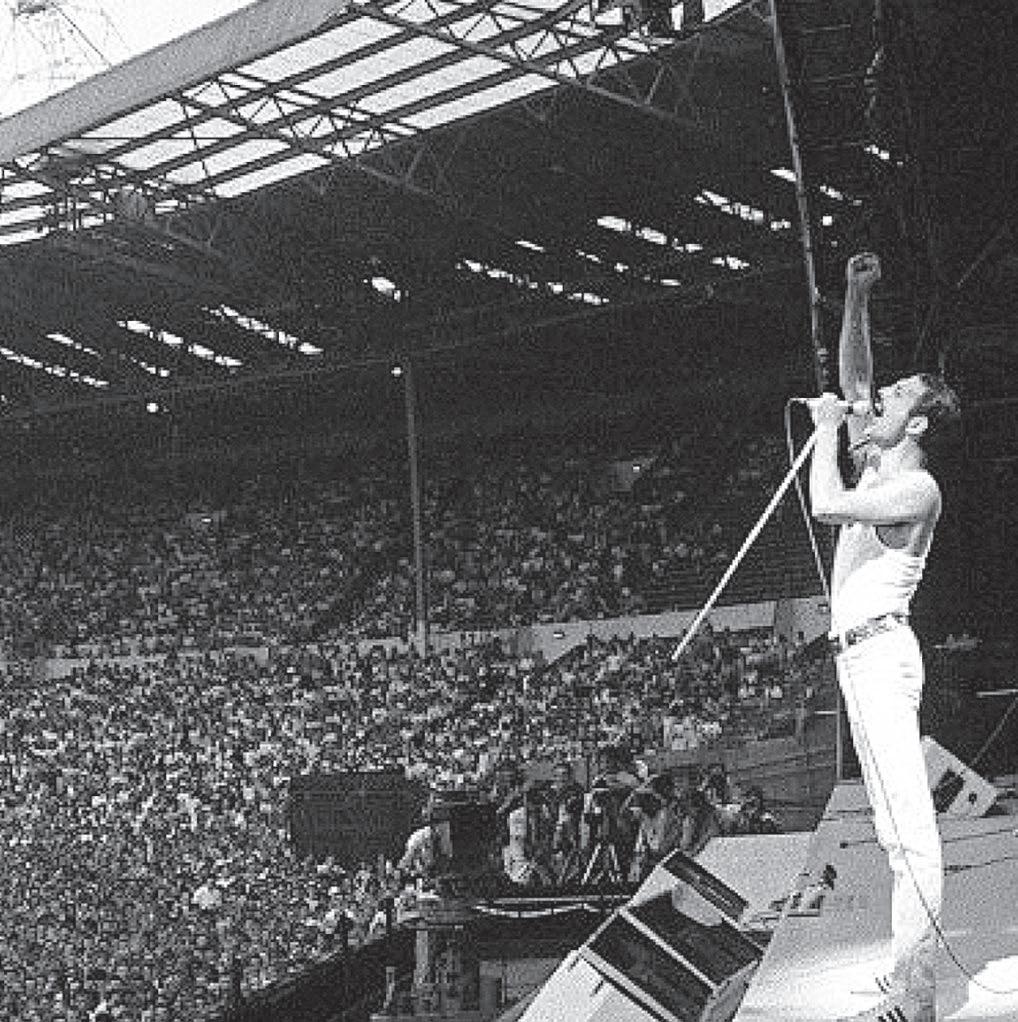

Freddie Mercury’s show-stopping Live Aid performance turned a generation of older TV viewers into concert-goers.

The Live Aid concert on 13 July 1985, which began the day at Wembley Stadium in London and closed in the evening at JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, was an event almost as close to the end of the Second World War as it is to the present time.

At that moment in popular music history – which was a mere thirty years after Little Richard’s unleashing of ‘Tutti Frutti’ but a full thirty-nine removed from the present day – the CD was yet to fully enter our lives, the internet was entirely beyond the imagination of all but a few scientists, and nobody present in London or Philadelphia on that day could possibly have realized that a whole way of doing things would very quickly be utterly overtaken by technology in a way that would render the memory of it difficult to recapture.

Revolutionary though it would prove to be, Live Aid was concertgoing the old way. The audience in London that day turned up clutching paper tickets which had cost them £25. In Philadelphia they were $35. This was 40 per cent more than people were used to paying at the time but it was considered acceptable because it was made clear that most of the cost was in the way of a charitable donation.

The people who worked behind the scenes on the shows were still doing things the way they would have done them in the previous decade. The massive logistical challenge that was Live Aid – two

enormous, interlocking, star-studded shows separated by thousands of miles but linked by television signals sent by satellite – was accomplished without the use of a single mobile phone for the simple reason that such things were unknown at the time to anybody but insanely early adopters or people working in distant oil fields.

The technicians working that day may have had some inkling of how that technology would soon change their work but the audience, in their stone-washed jeans, ‘Frankie Say’ T-shirts and Cyndi Lauper hair-stacks, didn’t have a clue what they were going to get and weren’t aware that they were about to enjoy one of the last unmediated experiences which music would offer. Because there was no mobile phone communication that day there was none of the social media traffic which would, within their lifetimes, come to shape responses to all events even as they were going on. None of us who were inside Wembley Stadium that day had any idea of the reverberations of what had been taking place there until we got home in the early hours of the following morning.

The set-up in Wembley was so pre-technological that Bob Geldof and all the other guests who filled the gaps by talking to broadcasters like me could only be interviewed if they first climbed via a series of catwalks up to a perspex box suspended in the eaves of the old stadium, the same box from which tweedy old commentators would pronounce on the goalscoring feats of footballers with perms. Wembley at the time was an old stadium which had been built for a pre-war world. Only a couple of months earlier it had been the venue for an FA Cup Final between two teams featuring only two players not born in the British Isles and only one of colour. It was mere weeks since the disaster at the Heysel Stadium in Brussels had killed thirty-nine people who had simply turned up to see a football match. In the Who’s crew that day were people who had been present at the concert in Cincinnati when eleven fans had

been killed in a crush. In 1985 Health and Safety was not yet a joke for the simple reason that Health and Safety was not yet a thing.

The crowd that made its way to Wembley that day on the London Underground were only just getting used to the idea that they were no longer permitted to light up on the journey. Pubs, restaurants and places of work were still wreathed in a haze of tobacco smoke. Magazine offices, such as the one I worked in at the time, were soundtracked by the clacking of manual typewriters and pierced by the sound of telephones that actually rang. In 1985 everything that had to be put together was put together by hand. Without spray fixative and Letraset, without ink bought by the barrel and paper delivered by fleets of trucks, without motorcycle messengers and switchboards, without turntables and reel-to-reel tape machines, the media of the time couldn’t possibly function. As for consumer comforts, the Live Aid crowd, an ecumenical bunch who were different in character from the highly partisan fans who would have been in attendance if any one of the acts had been headlining singly, trooped towards the stadium without one waxed cup of fancy coffee between them.

Live Aid was devised as a demonstration of compassion and a fundraiser. For the concert business it turned out to be something else as well: an unpaid advertisement for an entirely new beginning for rock and roll, one in which music would be combined with the gestural arts which have always been an essential component of the pop music racket and mounted on an unprecedented scale in front of huge audiences who had been drawn there as much by the human need to feel part of something vast as the love of the music. Though nobody knew it at the time, Live Aid announced the dawning of the Age of Spectacle.

I didn’t begin to realize this until I got home late that night. I had returned via a post-show party in the unlikely surroundings of a

Mayfair niterie at which representatives of the British bands that had performed at Wembley uncharitably barracked the efforts of the Philadelphia performers, which were being relayed into the club via a big screen, thus ensuring that I didn’t leave with too wide-eyed an impression of the proceedings. In fact it confirmed my conviction that few things occur in the world of rock or show business which aren’t at least partly about career. What I learned when I got home and in the days ahead was that as far as the wider world was concerned, on that one day the rock business had been suddenly transformed from a nest of vipers in which nobody’s motives were ever above question into a greater force for good than any of the established religions. My wife, who has had the good grace not to get too caught up in either the ups or the downs of the way I ended up earning my living, was sitting up in bed, still trying to process the events of the day. I was surprised first of all that she had watched it. I couldn’t help but be impressed by how impressed she had been. ‘Well, that was something,’ she said.

This was my first inkling of the way Live Aid had landed with the people who really mattered, who were of course not the acts, not the organizers and certainly not the people in the stadium; the people who mattered were the TV viewers. My wife was clearly not the only person who felt that way. She told me that parents and in-laws had been on the phone. She explained how she’d been contacted by friends and distant relatives saying they’d got neighbours over and were glued to their TVs as though this was a latter-day coronation. It appeared that the TV audience had grown throughout the day as people phoned each other on land lines and suggested that if they hadn’t already done so they really should switch on. The following day I spoke to no less a figure than the cricketing titan Viv Richards, the captain of West Indies and Somerset, who complained that his team had found it impossible to concentrate the previous day because of the competing attractions of what was going on at

Wembley Stadium. Batsmen were quite happy to be dismissed so that they could get back to the dressing room where they could resume their position in front of the TV.

This was most significant. It seemed that rock and roll, which had been going on its own sweet way without the majority of the population much caring, had suddenly come to the attention of people who were by no means rock and roll people. These were not people who needed to know who was playing drums with Led Zeppelin or who was in the current line-up of the Pretenders. These were regular people. Barbecuing people. Car-washing people. Floating voters. People from the suburbs. People who were, although they didn’t know it yet, suddenly being seduced by the appeal of an entertainment experience they had never taken a great deal of notice of before. They had been beguiled by the picturesque combination of big-name bands playing their big-name hits under cloudless skies. In the space of one day, this quite turned their heads.

If you wish to be specific about it, the Age of Spectacle began just after half past six that evening. It was at that point that Queen, a band that had been together for fifteen years, took to the stage. Queen were the turn that went down best on the day and that was because of Freddie Mercury. Freddie was the hit of the day because Freddie, being conversant with the theory and practice of showbiz, fully understood that Live Aid was most of all a TV spectacular and as such was aimed at an audience at home, and an audience at home was certainly not in the market for a few tracks from Queen’s new album. Therefore his performance of their key crowd-pleasers was addressed directly to cameraman Bob Wilson, one of the unsung BBC craftsmen who were decked out in white specially for the occasion so that they could thread their way in and out of the performers without spoiling the picture. The heavy camera on Bob’s strong shoulder sent the images to the big screen, which was the way that most people in Wembley saw the proceedings. Wilson got so near at one point

that Mercury, emboldened by how swimmingly it appeared to be going, lunged for his testes. Certainly at one point Mercury, relishing his role as de facto executive producer of the entire event for the period when he was on stage, led Wilson to centre stage and made him point his camera at the crowd as they imitated the singer as he clapped his hands above his head on ‘Radio Ga Ga’, and thus could be said to have directed the defining image of the day.

There couldn’t have been a better person to usher in this new age because Freddie truly knew spectacle. Six months earlier his band had played in front of three hundred thousand people in Rio de Janeiro and he understood that performing outdoors was all about the broadest of broad gestures, all about wrenching the crowd’s attention away from the competing attractions of the sky, the people in their immediate vicinity and the smell of the hotdog van and making them feel they were part of something bigger. The few years that acts like Queen had on relative greenhorns like U2 really showed that day. When Bono wandered off stage to commune with fans during their act the rest of the band lost sight of him entirely, leaving the stage at the end assuming it had been a disaster and they would never work again. In 1985 even the mega-stars were megashow virgins. The hottest act of 1985, Bruce Springsteen, didn’t even feature that day. He had only just played his very first open-air show a few weeks before at Slane Castle in Ireland and had found the experience so traumatic he had a serious argument with his manager in the dressing room at half-time. The root of his unease was his assumption that he would never be the kind of act who would play shows where he couldn’t look the audience in the eye. It had been one of the key tenets of punk rock that only sell-outs would agree to perform such shows. This view did not come under much challenge because the kind of acts that clung to it as an article of faith were not often invited to betray it. In the Age of Spectacle they would all be invited to betray it, and all of them would. If they felt

bad about that they could take some comfort from the front pages of the newspapers in the week following Live Aid when the headline writers were beginning to describe them in terms not ordinarily employed to characterize famous musicians doing their usual job in front of a worldwide TV audience. They were heroes.

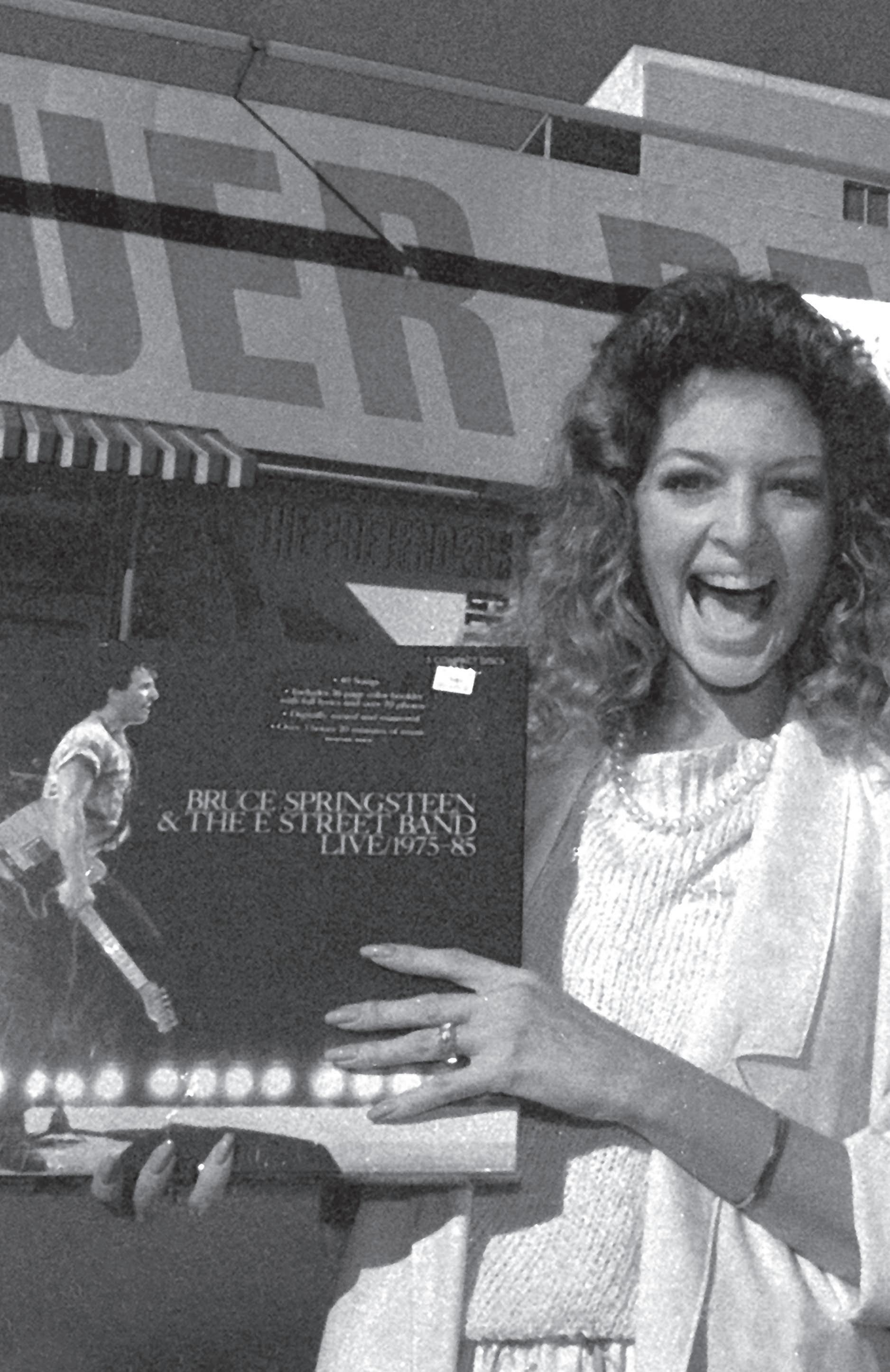

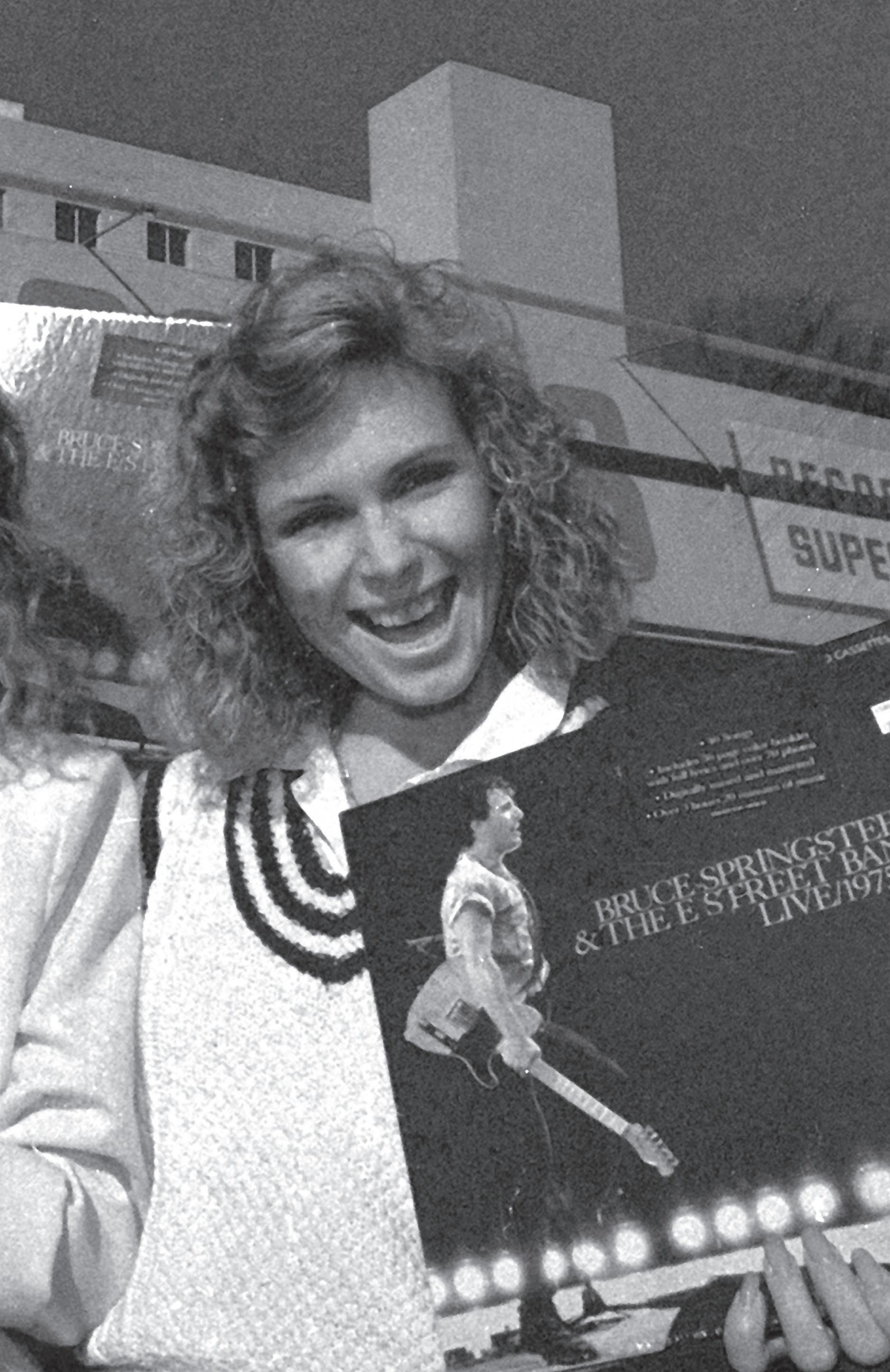

In 1986 record buyers lined up to invest in some reassuringly expensive old recordings from the former future of rock and roll.

The majority of the stars who had featured on the Band Aid record in 1984 were acts, like the Boomtown Rats, Ultravox, Duran Duran and Culture Club, that had come up in that boom in pop singles which followed on the heels of the so-called New Wave. This latter movement had positioned itself firmly as the Year Zero of popular music. In their philosophy the young were the pure in heart and the old were guilty until proved innocent. This notion took such a firm hold that it was not always apparent that there wasn’t a great deal in age terms between the members of the Stranglers, for instance, and the members of Fairport Convention (Hugh Cornwell and Richard Thompson having gone to school together), that Ian Dury and the Blockheads featured among their number players who had been full-grown men during the first Summer of Love, or that Debbie Harry was born in the same year as Eric Clapton. Everybody was doing everything in their power to appear to be on the side of the future rather than the past.

Live Aid seemed to put an end to that. Its youngsters were mostly in their thirties. Many of its veterans were still looking at forty. There wasn’t much difference between the two generations except in terms of experience. After Live Aid there was much talk of backstage fraternization between the seniors and the middle-schoolers. There were fewer references to the former being old and in the way. There were no longer any kids, they were all adults. There wasn’t just

one generation gap, there were lots. At Live Aid, Mick Jagger was closing in on his forty-second birthday; David Bowie, who had started at an earlier age, was a positively statesmanlike thirty-eight. Bob Dylan was forty-four. Tina Turner, bless her creaking bones, was all of forty-five. At the time she appeared at the concert she was celebrating more than six months on the British chart with an unlikely comeback album called Private Dancer and a single called ‘What’s Love Got To Do With It’, in the course of which she made the most of the songwriting and production input of the middleschoolers. To many of the younger people watching on TV at the time Tina may have appeared to be a game old girl who was enjoying a well-earned lap of honour. In fact she was just getting started. Something similar could be said of Paul McCartney. In September 1986 he appeared on the cover of a new music magazine called Q, which I had been involved in launching. We managed to secure McCartney not so much because we were guaranteed to give him a fair crack of the whip as because at the time most other media weren’t all that interested. His most recent public outing, the musical film Give My Regards to Broad Street, had endured a painful period in the critical barrel and the media climate of the times was such that nobody was inclined to give a forty-four-year-old apparent has-been an even break.

Whether he meant to or not, McCartney’s interview in Q marked the beginning of his campaign to claw back some of the credit for the Beatles, credit which in the immediate wake of John Lennon’s death in 1980 had been largely given to the man who had styled himself a working-class hero. This interview was the first place where he sought to make it clear that while John had been living out in the stockbroker belt succumbing to his post-touring depression, McCartney had been the one out on the town, doing the avantgarde thing. ‘He was one great guy but part of his greatness was he wasn’t a saint,’ he said. Asked how he felt when the microphone had

failed at Live Aid the previous year he confessed it had been embarrassing but he was honoured to have taken part. ‘The event itself was so great, but it wasn’t for my ego. It was like having been at the battle of Agincourt.’

While it had previously been axiomatic that the best thing a music magazine could offer was the hot new thing, in the years after Live Aid it was evident that there was a market for the hot old thing. Q successfully lined up the grand old men as cover stars because they gave good copy and the magazine found that they sold well. Already at this point it was becoming clear that the fame which had been won in the days when fame was rare had additional value in these MTV days when renown was suddenly cheap. In one 1986 issue there was an interview with Rod Stewart, who was in the middle of an Italian tour. The chat began with an almost accusatory ‘you’re forty-one’, but there was no indication that he was doing anything different as a consequence. At this point in the early middle age of the people who had made their bones in the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was as yet not the smallest sign of the exercise or diet regimes it would take to keep an ageing frame in shape for the demands of touring. Indeed the piece stated that Rod and his then twenty-six-year-old paramour, Kelly Emberg, began every day with forty minutes under a sun-ray lamp and made plain that during the rest of the day he held back from neither Barolo nor osso buco.

Like everyone else he was asked about Live Aid. Rod explained he wished he had played it but his band weren’t available. There was a picture of him with his Hollywood neighbours, who included Gregory Peck and Gene Kelly. At the time he was looking back on what seemed to have been a long career of twenty years and reflecting that if it all ended tomorrow he would have no regrets.

In the third issue, Elton John provided a piece which could have served as the template for many of the interviews that would be

given by the stars of the seventies as they rescued their own careers from the jaws of self-inflicted harm, reflected on how low they had been at their worst and then modestly proffered their new album or tour or book or incarnation. The basic shape of the rock star interview of this time could be distilled into the following four sentences: ‘I flew high. I fucked up. I’m back. Can you forgive me?’ Whether or not any of the people giving these interviews were aware that they were asking for an extension on Rod Stewart’s twenty years, whether or not they were consciously asking us to remain as attached to them in their later years as we had been in their first, that seemed to be the effect these chats had. At the same time they would make a modest bid to be rated among their heroes and offer some reassurance that they weren’t entirely cut off from what was happening at the present time in the shape of a reference to some new album they had really been enjoying.

What was beginning to happen at the time increasingly seemed to be the recent past. On 10 November 1986 crowds began queueing outside Tower Records’ flagship store in Manhattan in the dawn light, long before the trucks came up Broadway and disappeared with a much-ballyhooed cargo into the shop’s loading bay. As fast as they could be unloaded the individual items of that cargo were placed on display in the superstore, which had opened an hour early in honour of just this one release. As fast as they could be stacked up eager hands snatched the shrink-wrapped copies and took them to one of the six tills that had been specially opened to deal with the demand. The price was $25, which many thought an outrageous amount to charge for what were after all old songs. Retailers called it the biggest day in the history of the record business. For once they were probably right.

The boxed set, which opened to reveal five discs, three cassettes or three of the still relatively new-fangled CDs, was a forty-track

compilation of songs by Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band which had been recorded live between 1975 and 1985, the earliest shows at the Roxy, a former strip club in West Hollywood which could just about squeeze in five hundred souls, and the later ones at Giants Stadium in New Jersey, which could accommodate more than eighty thousand. In the interval between them the local boy had made an apparently fairytale transition from seven-stone weakling to national hero. That word again.

The scale of that transformation became a story in itself. The man who had once been the special darling of the rock press was now a story big enough and broad enough for the TV news and the serious papers. Hence the New York Times, which in 1986 was printing and selling a million paper copies every single day, had a reporter standing by when Tower opened their tills early. All three shoppers they quoted admitted they had come out to buy the new record early out of some sense of their duty as consumers, one because her husband wouldn’t forgive her if she didn’t bring one home, another because he’d been frightened that if he didn’t get to the shop early they would sell out, and another, a middle-aged surgeon, ‘probably because of the hype’. All three were indicators of a new mainstream audience for what came to be called heritage rock and an early manifestation of what would come to be known as FOMO.

In the United States it went to number one and stayed there for eight weeks, which was unprecedented for a boxed set, a format which at the time was seen as appealing to hardcore collectors rather than impulse shoppers at the mall. By March the following year the box had abruptly stopped selling and many shops, which had been taken in by their own initial enthusiasm, were looking at overstocks they would find difficult to move. This time record retailers were saying ‘it went up like a skyrocket and came down just as fast’. As time went on it seemed unlikely that many of the

people who had bought it really appreciated the record the way Springsteen had hoped, as he explained to me in a suite at the Parker Meridien Hotel where he turned up to be interviewed for British TV wearing a Triumph motorcycle T-shirt. He had agonized – didn’t he always? – about how to make this record, which comprised performances from a ten-year period, read like a story of his life. That’s why, he said, he wanted to finish it with his version of Tom Waits’ ‘Jersey Girl’ in order to signal that he had finally reached some sense of contentment.

This was the version of himself Springsteen was outlining at the time. He had married actress Julianne Phillips in May 1985 and there didn’t seem any reason why that shouldn’t lead to a domestic outcome to match the fairytale career. Now that he had finally made it to the top of the mountain, at the very advanced age of thirty-five, it was surely the time to bring the rest of his life into line. It would not prove to be as easy as that. When a member of our New York film crew commented that the golden couple’s marital unhappiness was already the gossip of Manhattan I chose to ignore it, particularly since not so much as a comma on the subject had found its way into the press. It wasn’t long before it turned out to be true. The two separated and then filed for divorce in 1988, with both parties pronouncing themselves satisfied with the terms of a settlement which under California law could have given her as much as half of the considerable amount he had earned during their time together. The settlement was reached quickly and both parties have been careful not to say anything controversial about their time together in the years since.

Middle age and domesticity clearly brought its own struggles, particularly for those whose working lives involved levels of excitement we civilians could not possibly imagine. Springsteen’s next album, Tunnel Of Love, was to be about the challenges of the personal life, which often come a distant second to the ones rock stars are acting

out as they strut and fret on the boards. On the cover he wore a tie and leaned against a fancy car wearing the rueful look of a disappointed bridegroom. There was only one sleeve note. It read: ‘Thanks Juli.’ It was clearly all grist to the mill. As the writer Nora Ephron put it, everything’s copy.

Solid citizens enjoy a scoop of Cherry Garcia ice cream, a flavour named for the previously alternative Grateful Dead.

In the middle of February 1987, when the American republic was celebrating the birthday of its first president, George Washington, a Vermont-based ice-cream company which burnished its folksy, small-town image by trading under the name Ben & Jerry’s unveiled a new flavour. Featuring chocolate flakes and Bing cherries, it honoured another American folk hero and was to be marketed under the name Cherry Garcia.

The company claimed they got the idea of naming a flavour after Jerry Garcia, the leader of the San Francisco group the Grateful Dead – a figure who would once have been identified as a leading light of the counter-culture, a man so restlessly curious about the consciousness-altering properties of illegal drugs that his nickname was ‘Captain Trips’ – from a correspondent who signed herself ‘a Deadhead from Maine’. The acolyte turned out to be an ice-cream enthusiast named Jane Williamson. Jane had intuited what would ultimately be accepted as the core truth of rock and roll merchandising: the acts that make the most money from merchandising are the ones that appear to be least bothered about that money; simultaneously the fans most ready to invest their money in said merchandising are the very ones who most pride themselves on their lack of interest in such material matters. ‘You know it makes sense,’ Williamson wrote to the company. ‘Dead paraphernalia always sells.’

In this she was entirely correct. The Grateful Dead had begun in 1965 as a mere jug band. It wasn’t until 1976 that they officially became a corporation with the members of the band making up its board of directors. This in itself was an indication they were in it for the long haul. Eschewing some of the corporate cash-grabs that did so much to tarnish the images of bands like the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead wished nonetheless to participate fully in the value they had created. The people at Ben & Jerry’s ice cream were about to discover this.

Having shipped a few pints of their creamy new line to the Grateful Dead’s PR and heard in return that Jerry was pleased to be associated with anything so long as it wasn’t engine oil, they assumed they had all the blessing they needed. That was apparently not the case. Having operated on the ‘don’t ask permission, ask forgiveness’ principle, they couldn’t be entirely surprised to find they received a cease-and-desist letter from the Dead’s lawyers which made it clear that the corporation would not be mollified until a royalty had been negotiated. Since Cherry Garcia immediately became one of Ben & Jerry’s three most popular flavours this proved to be a steady income.

This addition to the revenue line may not have been transformational for either the band or the gelatiers but it was a small but potent symbol of how a band which in the sixties had stood for benign chaos now stood for benign continuity. Ben & Jerry’s even produced a T-shirt bearing the legend ‘what a long strange dip it’s been’ in honour of the band’s slogan ‘what a long strange trip it’s been’. It was what conventional marketeers would call a win-win.

For the confectioners it provided a way of introducing the intangible quality of credibility into the fast-melting world of ice cream. In return it achieved the previously impossible feat of connecting the Grateful Dead with middle America. Now it wasn’t just stoners with the munchies who were going home with pints of the stuff, it