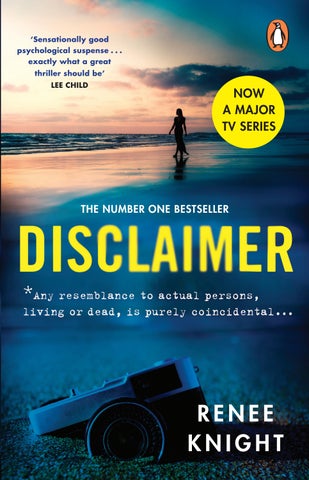

‘Sensationally good psychological suspense . . . exactly what a great thriller should be’

LEE CHILD

THE NUMBER ONE BESTSELLER

‘Sensationally good psychological suspense . . . exactly what a great thriller should be’

LEE CHILD

‘Disclaimer is something special . . . an outstandingly clever and twisty tale that’s been perfectly engineered to make heads spin’

New York Times

‘Sensationally good psychological suspense . . . exactly what a great thriller should be’

LEE CHILD

‘You may as well just surrender now and read it and enjoy it because it’s not going to go away – and deservedly so’

BBC Radio 2 Arts Show

‘An addictive novel with shades of Gone Girl ’

Sunday Times

‘I read Disclaimer in two sittings . . . It’s that good . . . The premise is the star of the show but Knight’s success lies in keeping her plot, characterisation and unpredictability up to that same standard’

Daily Express

‘Prepare to cancel all other commitments’

Stylist

‘Fabulously gripping, I just could not put it down’

MARIAN KEYES

‘A finely crafted puzzle box’ Spectator

‘The narrative is elegantly written . . . a maelstrom of appalling revelations and twists’

Daily Mail

‘A really clever twist . . . superior fodder for your summer hols’

Evening Standard

‘An original plot, well-paced to its unexpected climax’ The Times

‘Disclaimer forms a trinity alongside Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train as the best of domestic noir’ New York Daily News

‘Assured debut novel . . . strong and compelling portrait of two individuals who are forced to confront unpalatable, even unbearable, truths’ Guardian

‘Disclaimer stealthily steals your attention and by the end holds you prisoner – a searing story that resonates long after the final page. The best thriller I’ve read this year’

ROSAMUND

LUPTON, bestselling author of Sister

‘If it’s a creepy read you’re after, look no further’ Good Housekeeping (Thriller of the Month)

‘A fine example of the genre . . . unbearably tense’ Sunday Express

‘An ingenious and involving tale and a very successful first novel’ Literary Review

‘Superb debut . . . Knight paces the novel beautifully’ The Times

‘An intelligent and twisty thriller’ Elle

‘A terrific novel with a brilliantly creepy central premise. One of the best debut thrillers I have ever read’

PAULA

DALY, author of Keep Your Friends Close

‘An unsettling page-turner of The Girl on the Train variety that will live on in readers’ imaginations’ Grazia

‘A deeply probing, intense psychological thriller that was gripping and very difficult to put down’

Huffington Post

‘A faultlessly constructed, page-turning debut, Disclaimer delivers its twists and surprises with ease. It is both clever and moving, and I’m full of admiration’

JOANNA BRISCOE

‘An enthralling thriller’ Heat

‘A brilliant premise, superbly executed. I love this book’ CLARE MACKINTOSH, bestselling author of I Let You Go

‘A superior piece of dark emotional fiction that will get under your skin’ Sainsbury’s Magazine

‘A genuinely original debut novel, nail-bitingly tense and chilling’

Irish Independent

‘A highly assured debut novel with a cracking premise . . . a remarkable well-written page-turner’ Euro Crime

‘Renée Knight’s stunning debut is a thriller with a particularly literary flavour, but also with a heart. Best enjoyed slowly, with no skipping to the heartwrenching conclusion. Terrific’ Saga Magazine

‘Renée Knight skilfully peels away the layers of her story to reveal a tale that is dark, deep and skin-crawlingly sinister. I thought it was faultless, a masterclass in thriller writing’

COLETTE MCBETH

Renée Knight worked as a documentary-maker for the BBC before turning to writing. She is a graduate of the Faber Academy ‘Writing a Novel’ course, and lives in London with her husband and two children. Her widely acclaimed debut novel, Disclaimer, was a Sunday Times No.1 bestseller. Her most recent novel is The Secretary.

PENGUIN BOOK S

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Doubleday an imprint of Transworld Publishers Black Swan edition published 2015 Black Swan edition reissued 2024

Copyright © Renée Knight 2015

Renée Knight has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781784160227

Typeset in 11/15pt Giovanni Book by Kestrel Data, Exeter, Devon. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Catherine braces herself, but there is nothing left to come up. She grips the cold enamel and raises her head to look in the mirror. The face that looks back at her is not the one she went to bed with. She has seen this face before and hoped never to see it again. She studies herself in this new harsh light and wets a flannel, wiping her mouth then pressing it against her eyes as if she can extinguish the fear in them.

‘Are you OK?’

Her husband’s voice startles her. She hoped he would stay asleep. Leave her alone.

‘Better now,’ she lies, switching off the light. Then she lies again. ‘Must have been last night’s takeaway.’ She turns to him, a shadow in the dead-hour light.

‘Go back to bed. I’m fine,’ she whispers. He is more asleep than awake, yet still he reaches out and puts his hand on her shoulder.

‘You sure?’

‘I’m sure,’ she says. All she is sure about is that she needs to be alone.

‘Robert. Honestly. I’ll be there in a minute.’

His fingers linger on her arm for a moment, then he does as she asks. She waits until she is certain he is asleep before returning to their bedroom.

She looks at it lying there face down and still open where she left it. The book she trusted. Its first few chapters had lulled her into complacency, made her feel at ease with just the hint of a mild thrill to come, a little something to keep her reading, but no clue to what was lying in wait. It beckoned her on, lured her into its pages, further and further until she realized she was trapped. Then words ricocheted around her brain and slammed into her chest, one after another. It was as if a queue of people had jumped in front of a train and she, the helpless driver, was powerless to prevent the fatal collision. It was too late to put the brakes on. There was no going back. Catherine had unwittingly stumbled across herself tucked into the pages of the book.

Any resemblance to persons living or dead . . . The disclaimer has a neat, red line through it. A message she failed to notice when she opened the book. There is no mistaking the resemblance to her. She is a key character, a main player. Though the names may have been changed, the details are unmistakable, right down to what she was wearing that afternoon. A chunk of her life she has kept hidden. A secret she has told no one, not even her husband and son – two people who think

they know her better than anyone else. No living soul can have conjured up what Catherine has just read. Yet there it is in printer’s ink for anyone to see. She thought she had laid it to rest. That it was finished. But now it has resurfaced. In her bedroom. In her head. She tries to dislodge it with thoughts of the previous evening. The contentment of settling into their new home: of wine and supper; curling up on the sofa; dozing in front of the TV and then she and Robert melting into bed. A quiet happiness she had taken for granted: but it is too quiet to bring her comfort. She cannot sleep so gets out of bed and goes downstairs.

They still have a downstairs, just about. A maisonette, not a house any more. They moved from the house three weeks ago. Two bedrooms instead of four. Two bedrooms are a better fit for her and Robert. One for them. One spare. They’ve gone for open-plan too. No doors. They don’t need to shut doors now Nicholas has left. She turns on the kitchen light and takes a glass from the cupboard and fills it. No tap. Cool water on command from the new fridge. It’s more like a wardrobe than a fridge. Dread slicks her palms. She is hot, almost feverish, and is thankful for the coolness of the newly laid limestone floor. The water helps a little. As she gulps it down she looks out of the vast glass windows running along the back of this new, alien home. Only black out there. Nothing to see. She hasn’t got round to blinds yet. She is exposed. Looked at. They can see her, but she can’t see them.

I did feel sorry about what happened, I really did. He was only a child after all: seven years old. And I was, I suppose, in loco parentis, although I jolly well knew that none of the parents would have wanted me being loco anything. By then I had sunk pretty low: Stephen Brigstocke, the most loathed teacher in the school. Certainly I think the children thought so, and the parents, though not all of them: I hope some of them remembered me from before, when I had taught their older children. Anyway, I wasn’t surprised when Justin called me into his office. I’d been waiting for it. It took him rather longer than I’d expected, but that’s private schools for you. They are their own little fiefdoms. The parents might think they’re in control because they’re paying, but of course they’re not. I mean, look at me – I was barely interviewed for the job. Justin and I had been at Cambridge together and he knew I needed the money, and I knew he needed a head of English. You see, private schools pay more than state and I had had

years of experience teaching in a state comprehensive. Poor Justin, it must have been very difficult for him to remove me. Awkward, you know. And it was a removal, rather than a sacking. It was decent of him, I appreciate that. I couldn’t afford to lose my pension, and I was around retirement age anyway, so he merely hastened the process. In fact, we were both due for retirement but Justin’s departure was quite different to mine. I heard that some of the pupils even shed a tear. Not for me though. Well, why should they? I didn’t deserve those kinds of tears.

I don’t want to give the wrong impression: I’m not a paedophile. I didn’t fiddle with the child. I didn’t even touch him. No, no, I never, ever touched the children. The thing is, I found them so bloody boring. Is that a terrible thing to say about seven-year-olds? I suppose it is for a teacher. I got sick of reading their tedious stories, which I’m sure some of them laboured over, but even so, it was that sense they had of themselves, that at seven, for crying out loud, they had anything to say that I might be interested in. And then one evening I had just had enough. The catharsis of the red pen no longer worked and when I got to this particular boy’s essay, I don’t remember his name, I gave him a very detailed critique of why I couldn’t really give a shit about his family holiday to southern India where they’d stayed with local villagers. Well, how bloody marvellous for them. Of course it upset him. Of course it did and I’m sorry for that. And of course he told his

parents. I’m not sorry about that. It helped speed up my exit and there’s no doubt I needed to go for my own sake as well as theirs.

So there I was, at home with a lot of time on my hands. A retired English teacher from a second-rate private school. A widower. I worry that perhaps I am being too honest – that what I have said so far might be a little off-putting. It might make me appear cruel. And what I did to that boy was cruel, I accept that. But as a rule, I’m not a cruel person. Since Nancy died though, I have allowed things to slide a little. Well, OK, a lot.

It is hard to believe that, once upon a time, I was voted Most Popular Teacher in the Year. Not by the pupils at the private school, but by those at the comprehensive I’d taught at before. And it wasn’t a one-off, it happened several years running. One year, I think it was 1982, my wife, Nancy, and I both achieved this prize from our respective schools.

I had followed Nancy into teaching. She had followed our son when he began at infants’. She’d taught the five- to six-year-olds at Jonathan’s school and I was assigned the fourteen- to fifteen-year-olds at the comp up the road. I know some teachers find that age group a struggle, but I liked it. Adolescence isn’t much fun and so my view was, give the poor buggers a break. I never forced them to read a book if they didn’t want to. A story is a story after all. It doesn’t just have to be read in a book. A film, a piece of television, a play – there’s

still a narrative to follow, interpret, enjoy. Back then I was committed. I cared. But that was then. I’m not a teacher any more. I’m retired. I’m a widower.

Catherine stumbles, blaming her high heels, but knowing it’s because she’s had too much to drink. Robert reaches his hand to grab her elbow, in time to stop her falling backwards down the concrete steps. His other hand turns the key and pushes open the front door, his grip on her arm still firm as he leads her inside. She kicks off her shoes, and tries to inject some dignity into her walk as she heads for the kitchen.

‘I’m so proud of you,’ he says, coming from behind and folding his arms around her. He kisses the skin where neck curves into shoulder. Her head stretches back.

‘Thank you,’ she says, closing her eyes. But then this moment of happiness melts away. It is night. They are home. And she doesn’t want to go to bed even though she is desperately tired. She knows she won’t sleep. Hasn’t slept properly for a week. Robert doesn’t know this. She pretends all is well, managing to conceal it from him. Pretending to be asleep, lying next to him,

alone in her head. She will have to invent an excuse to explain why she’s not going to follow him straight to bed.

‘You go up,’ she says. ‘I’ll be there in a minute. I want to check some emails.’ She smiles encouragement, but he doesn’t need much. He has to be up early the next morning, which is why Catherine appreciates even more the real pleasure he seems to have got from an evening where she has been the centre of attention and he the silent, smiling partner. Not once did he hint that maybe it was time to go. No, he had allowed her to shine and enjoy the moment. Of course, she has done this for him on many occasions; still, Robert had played his part with grace.

‘I’ll take up some water for you,’ he says. They have just returned from a party, the aftermath of a television awards ceremony. Serious television. No soaps. No drama. Factual. Catherine had won an award for a documentary she had made about the grooming of children for sex. Children who should have been protected but weren’t because nobody had cared enough; nobody had taken the trouble to look out for them. The jury had described her film as brave. She had been described as brave. They have no idea. They have no idea what I’m really like. It wasn’t bravery. It was single-minded determination. Then again, maybe she had been a little bit brave. Secret filming. Predatory men. Not now though. Not now she is at home. Even with the new blinds, she fears she is being watched.

Her evenings have become a series of distractions to stop herself thinking about the inevitable time when she will be lying in the dark, awake. She has managed to fool Robert, she thinks. Even the sweating, which comes on as bedtime gets closer, she has laughed off as the menopause. She has other signs of that, sure, but not this sweating. Though she had wanted him to go to bed, as soon as he has, she wishes he was with her. She wishes she was brave enough to tell him. She wishes she had been brave enough to tell him back then. But she wasn’t. And now it is too late. It was twenty years ago. If she told him now he would never understand. He would be blinded by the fact that, for all this time, she has kept a secret from him. She has withheld something that he would feel he had a right to know. He is our son, for Christ’s sake, she hears him say.

She doesn’t need a fucking book to tell her what happened. She hasn’t forgotten any of it. Her son had nearly died. She has been protecting Nicholas all these years. Protecting him from knowing. She has enabled him to live in blissful ignorance. He doesn’t know that he almost didn’t make it into adulthood. And if he had held on to some memory of what happened? Would things be different? Would he be different? Would their relationship be different? But she is absolutely sure that he remembers nothing. At least, nothing that would bring him close to the reality of it. For Nicholas, it is simply an afternoon that has merged in with many others from his childhood. He

might even remember it as a happy one, she thinks.

If Robert had been there, it might have been different. Well of course it would have been different. It wouldn’t have happened. Except Robert wasn’t there. So she didn’t tell him because she didn’t need to – he would never find out. And it was better that way. It is better that way.

She opens her laptop and googles the author’s name. Almost a ritual, this. She has done it before, hoping there’ll be something there. A clue. But there is nothing. Simply a name: E. J. Preston. Made up, probably. ‘The Perfect Stranger is E. J. Preston’s first and possibly last book.’ No clue as to gender even. Not his or her first book. It is published by Rhamnousia; when she looked that up it had confirmed what she had already suspected, that the book is self-published. She hadn’t known what Rhamnousia meant. Now she does. The goddess of revenge, aka Nemesis.

That’s a clue, isn’t it? About gender, at least. But that’s impossible. It can’t be. And no one else knew those details. No one still living. There were others, though – anonymous others. But this has been written by someone who really cares. This is personal. She looks to see if there have been any reviews. There are none. Perhaps she is the only one to have read it. And even if others do, they will never know that she is the woman at its heart. Someone does, though. Someone knows. How the fuck did this book get into her home? She has no memory of buying it. It just seemed to appear

on the pile of books by her bed. But then everything has been so chaotic with the move. Boxes and boxes full of books still waiting to be unpacked. Perhaps she put it there herself. Took it from a box, attracted to the cover. It could be Robert’s. He has countless books she has never read and might not recognize. Books from years ago. She pictures him trawling through Amazon, taking a fancy to the title, to the cover, and ordering it online. A fluke. A sick coincidence. But what she settles on and begins to believe is that someone else put it there. Someone else came into their home, this place that doesn’t yet feel like home. Came into their bedroom. Someone she doesn’t know laid the book down on the shelf next to her bed. Carefully. Not disturbing anything. On her side of the bed. Knowing which side she slept on. Making it look as if she had put it there herself. Her thoughts pile up, crashing into each other until they are twisted and jagged. Wine and anxiety, a dangerous combination. She should know by now not to mix her poisons. She grips her aching head. Always aching these days. She closes her eyes and sees the burning white dot of sun on the book’s cover. How the fuck did this book get into her home?

It had been seven years since Nancy died and yet I still hadn’t got round to sorting through her things. Her clothes hung in the wardrobe. Her shoes, her handbags. She had tiny feet. Size three. Her papers, letters, still lay on the desk and in drawers. I liked coming across them. I liked picking up letters to her, even if they were from British Gas. I liked seeing her name and our shared address written down officially. I had no excuse once I’d retired though. Just get on with it, Stephen, she would have said. So I did.

I started with her clothes, unhooking them from hangers, taking them out of drawers, laying them out on the bed, ready for their journey out of the house. All done, I’d thought, until I saw a cardigan that had slipped off its hanger, and was hiding in a corner of the wardrobe. It is the colour of heather. Lots of colours, actually. Blue, pink, purple, grey, but the impression is of heather. We had bought it in Scotland before we were married. Nancy used to wear it like a shawl: the

sleeves, empty of her arms, hanging limply at her sides. I have kept it; I’m holding it now. It is cashmere. The moths have got at it and there is a small hole on the cuff that I can fit my little finger through. She hung on to it for over forty years. It has outlived her and I suspect that it will outlive me too. If I continue to shrink, as I undoubtedly will, then I might soon be able to fit into it.

I remember Nancy wearing it in the middle of the night when she’d get up to feed Jonathan. Her nightgown would be unbuttoned with Jonathan’s tiny mouth around her nipple and this cardigan draped around her shoulders, keeping her warm. If she saw me watching from the bed she would smile and I would get up and make tea for us both. She always tried not to wake me, she said she wanted me to sleep and that she didn’t mind being up. She was happy. We both were. The joy and surprise of a child delivered in middle age when we had all but given up hope. We didn’t bicker about who should get up or who was stealing whose sleep. I’m not going to claim it was fifty–fifty. I would have done more, but the truth is that it was Nancy who Jonathan needed most of, not me.

Even before those midnight feasts, that cardigan was a favourite of hers. She wore it when she was writing: over a summer frock; over a blouse; over her nightdress. I’d glance over from my desk and watch her at hers, striking out at her typewriter, the limp sleeves quivering at her sides. Yes, before we became

teachers Nancy and I were both writers. Nancy stopped soon after Jonathan was born. She said she’d lost her appetite for it, and when Jonathan started at the infants’ school she decided to get a job teaching there. But I’m repeating myself.

Neither Nancy nor I had much success as writers, although we both had the odd story published. On reflection, I would say that Nancy had more success than me, yet it was she who insisted I carry on when she gave up. She believed in me. She was so sure that one day it would happen, that I’d break through. Well, maybe she was right. It has always been Nancy’s faith which has driven me on. She was the better writer though. I never lost sight of that, even if she didn’t acknowledge it. She supported me for years as I produced word after word, chapter after chapter, and one or two books. All rejected. Until, thank God, she finally understood that I didn’t want to write any more. I’d had enough. It just felt wrong. It was hard to get her to believe me when I said it was a relief to stop. But I meant it. It was a relief. You see I’d always enjoyed reading far more than writing. To be a writer, to be a good writer, you need courage. You need to be prepared to expose yourself. You must be brave, and I have always been a coward. Nancy was the brave one. So, that’s when I started teaching. It did take courage though to clear out my wife’s things. I folded her clothes and put them in carrier bags. Her shoes and handbags I put into boxes that had

once held bottles of wine. No inkling, when that wine came into the house, that the boxes it arrived in would leave containing my dead wife’s accessories. It took me a week to pack everything up, longer to remove it from the house.

I couldn’t bear to let everything go at once and so I staggered my trips to the charity shop. I got to know the two women at All Aboard quite well. I told them the clothes had belonged to my wife and after that, when I dropped by, they would stop what they were doing and make time for me. If I happened to turn up when they were having coffee, they’d make me a cup too. It became strangely comforting, that shop full of dead people’s clothes.

I worried that, once I finished the job of sorting through Nancy’s things, I would fall back into the lethargy I’d been in since I’d retired, but I didn’t. As sad as it was, I knew I had done something Nancy would have approved of and I made a decision: from then on I would do my utmost to behave in a way that, if Nancy were to walk into the room, she would feel love for me and not shame. She would be my editor, invisible, objective, with my best interests at heart.

One morning, not long after that clear-out period, I was on my way to the Underground station. I had woken with a real sense of purpose: got up, washed, shaved, dressed, breakfasted and was ready to leave the house by nine. I was in a good mood, anticipating a day spent in the British Library. I had been thinking

about writing again. Not fiction; something more solid, factual. Nancy and I had sometimes holidayed on the East Anglian coast and one summer we had rented a Martello tower. I had always wanted to find out more about the place, but every book I’d found on the subject had been so dry, so lifeless. Nancy had tried too, for various birthdays of mine, but all she had come up with were dull volumes full of dates and statistics. Anyway, that’s what I settled on as my writing project: I would bring that marvellous place to life. Those walls had been soaked in the breath of others over hundreds of years and I was determined to find out who had spent time there from then until now. So that morning I had set off with quite the spring in my step. And then I saw a ghost.

I didn’t have a clear view of her. There were people between us. A woman pushing her child in a pram. Two youths ambling. Smoking. I knew it was her, though. I would know her anywhere. She was walking quickly, with purpose, and I tried to keep up but she was younger than me, her legs stronger, and my heart raced with the effort and I was forced to stop for a moment. The distance between us grew and by the time I was able to move again she had disappeared into the Underground. I followed, fumbling to get through the barrier, fearful that she would get on a train and I would miss her. The stairs were steep, too steep, and I feared I might fall in my rush to join her on the platform. I gripped the rail and cursed my feebleness.

She was still there. I smiled as I walked up to her. I thought she had waited for me. And she turned and looked right at me. There was no smile returning mine. Her expression was anxious, perhaps even scared. Of course it wasn’t a ghost. It was a young woman, maybe thirty. She was wearing Nancy’s coat, the one I had given to the charity shop. She had the same colour hair as Nancy had had at that age. Or at least, that’s what I had seen. When I got up close I realized the colour of this young woman’s hair was nothing like Nancy’s. Brown yes, but fake, flat, dead-brown. It didn’t have the vibrant, living shades of Nancy’s hair. I could see that my smile had alarmed her so I turned away, hoping she would understand I hadn’t meant any harm, that it was a mistake. When the train came, I let it go and waited for the next one, not wanting her to think I was following her.

I didn’t fully recover until halfway through that morning. The quiet of the library, the beauty of the place and the comforting tasks of reading, making notes, making progress got me back to the place I had been when I started my day. By the time I got home in the early evening, I was quite myself again. I’d picked up one of those Marks and Spencer meals as a treat, an easy supper. I opened a bottle of wine, but drank only one glass. I don’t drink much these days: I prefer to have control over my thoughts. Too much alcohol sends them haring off in the wrong direction, like outof-control toddlers.

I was keen to go through my notes before bed, so I went to my desk to make a start. Nancy’s papers were still littering the desktop. I flicked through circulars and old bills, knowing already that I’d find nothing of real importance. If there had been, wouldn’t it have made its presence felt by now? I tipped the lot into the waste-paper basket, then took my typewriter from the cupboard and set it down in the centre of the cleared desk, ready to start work the following morning.

When Nancy had been writing she had had her own desk, a small oak one which now sits in Jonathan’s flat. When she stopped, we agreed that she might as well share mine. She had the right-hand drawers, I the left. She kept her manuscripts in the bottom drawer and although there were others stacked on the bookcase, the three in the desk were the ones she had had most hope for. Even though I knew they were there, it gave me a shock to see them. ‘A View of the Sea’, ‘Out of Winter’ and ‘A Special Kind of Friend’, all unpublished. I picked up ‘A Special Kind of Friend’ and took it to bed with me.

It must have been nearly forty years since I had read those words. She had written the novel the summer before Jonathan was born. It was as if Nancy was in bed with me. I could hear her voice clearly: Nancy as a young woman, not yet a mother. There was energy in it, fearlessness, and it threw me back to a time when the future had excited us; when things that hadn’t happened yet thrilled rather than frightened. I was

happy when I went to sleep that night, appreciating that, even though she was no longer with me, I had been lucky to have had Nancy in my life. We had opened ourselves up to each other. We had shared everything. I thought we knew all there was to know about each other.

‘Wait – I’ll come out with you,’ Catherine calls from the top of the stairs.

Robert turns at the front door and looks up at her.

‘I’m sorry, sweetheart, did I wake you?’

She knows how hard he had tried not to; he kept his shower short, tiptoed around while dressing. Catherine, however, had been awake the whole time. Lying there. Eyes half closed. Watching him and loving him for being so considerate. She had waited as long as she could. As soon as he left the room she had scrambled out of bed, dressed, then chased down after him. She couldn’t be alone yet. Later maybe, but not yet.

She sits on the bottom stair, cramming her feet into trainers.

‘I’ve got a stinker of a head. Best thing to do is get out there and clear it,’ she says, tying her laces with shaky fingers. She hears herself, sounding so normal, so plausible. Shaky fingers could be a hangover. She

has taken the week off work to unpack and settle them in – to turn their new place into a home – but this morning she cannot face it. And it’s true, she does have a stinker of a head. It has nothing to do with last night’s celebrations though.

She sees Robert check his watch. He has to be in early.

‘I’ll be quick, I’ll be quick,’ she says, running into the kitchen, filling a bottle of water, grabbing her iPod before running back to him. They slam the door shut, double-lock and walk together to the Tube. She reaches for his hand and holds it, and he looks at her and smiles.

‘That was fun last night,’ he says. ‘Did you get lots of nice emails?’

‘A few,’ she says, although she hadn’t bothered to check. It had been the last thing on her mind. She’ll have a look later, when she’s home, when her head is clearer. He pecks her on the cheek, tells her he shouldn’t be late home, hopes her head feels better and then disappears into the Underground. She turns round as soon as he has gone, sticking in her ear-buds and running up the road. Back the way they’d come, towards the only green space in the area. Her feet slap in time to the music.

She passes the top of their road and keeps going. Her heart is thumping, sweat is already running down between her shoulder blades. She is not fit. She should be doing a fast walk, not a run, but she needs the

discomfort. She reaches the high, wrought-iron gates of the cemetery and runs through. She manages one circuit then stops, panting for breath, bending down and resting her hands on her knees. She should stretch out, but she feels too self-conscious. She is not an athlete, merely a woman on the run.

Keep going, keep going. She straightens up and sets off again, a gentle jog, not punishing, allowing thoughts to stir. As she reaches the halfway point she slows to a walk, keeping it brisk, wanting her heart to stay strong, to keep pumping. Names float out to her from the gravestones: Gladys, Albert, Eleanor, names from long ago of people long dead. But it’s the children she notices. The children whose stones she stops to read. The beginnings and ends of their short lives. Doesn’t everyone do that? Stop at the graves of the children tucked up for ever in their grassy beds? They take up less space than their grown-up neighbours and yet their presence is impossible to ignore, crying out to be looked at. Please stop for a moment. And she does. And she imagines a stone that could have been there, but isn’t.

Nicholas Ravenscroft

Born 14 January 1988, taken from us on 14 August 1993

Beloved son of Robert and Catherine

And she imagines how she would have been the one who would have had to tell Robert that Nicholas had

died. And she hears his questions: Where were you? How could that have happened? How was it possible? And she would have burst open, poured everything out on to him and he would have sunk under the weight of it. She sees him struggle, pushing against it, trying to raise his head above the deluge, gasping for air but never quite getting enough to make a full recovery.

Nicholas didn’t die though. He is alive, and she didn’t have to tell Robert. They have all survived intact.

I woke the morning after reading ‘A Special Kind of Friend’ refreshed. I was eager to start work and had planned to look through my notes before typing them up. I knew there was some paper in the dresser cupboard: everything seemed to end up either on or in our dresser. I could picture the sheaf of paper sitting beneath the games of Scrabble and backgammon, but when I tried to pull it out, it wouldn’t come. It was trapped in the back of the dresser. A panel had been pushed in and I pressed against it, trying to release the paper; still it wouldn’t budge. Something was stuck between the dresser and the wall. I put my hand around the back and touched something soft. It was an old handbag of Nancy’s: a cunning one that had managed to evade the trip to the charity shop. I leaned against the wall, stretching my legs in front of me with the handbag on my lap. It was black suede with two pearl drops clasped around each other. I dusted it down and looked inside. There was a set of

keys to Jonathan’s flat, a lipstick and a handkerchief still pressed in a square where it had been ironed. I took the top off the lipstick and sniffed it. It had lost its scent yet kept its angled shape from the years it had stroked Nancy’s lips. I held the hanky to my nose, and its perfume conjured up memories of evenings at the theatre. What I hadn’t expected to find was the yellow envelope of photographs with Kodak in thick black lettering on the front. This was a precious find and I wanted to make an occasion of it.

I made myself some coffee and settled down on the sofa, anticipating a flood of happy memories. I assumed the pictures were holiday snaps. I think I even hoped there might be a few of the Martello tower: that finding the handbag was Nancy’s way of helping me on with my project. In a way it was, but not the one I had had in mind that morning.

My head, which had been so clear at the start of the day, felt as if the contents of someone else’s had been dumped into it. I could no longer tell which thoughts were mine and which were theirs; which ones were true and which were lies. My coffee had gone cold; the pictures were spread out on my lap. I had expected images I recognized, but I had never seen these pictures before.

She was looking straight into the camera. Flirting? I think so. Yes, she was flirting. They were colour photos. Some were taken on a beach. She was lying there, a smiling sweetheart on holiday in a red bikini.

Her breasts were pushed up as if she was some sort of pin-up girl and she certainly looked as if she thought herself a very desirable woman. Confident. Yes, that’s what it was. Sexual confidence. Others were taken in a hotel room. They were shameless. She was shameless. I couldn’t look away though. I could not stop looking. I went through them again and again, tormenting myself, and the more I looked, the angrier I became because the more I looked, the more I understood. What chewed at my heart was that I knew who had taken these pictures. I knew the handsome face behind the camera even though I couldn’t find him. I looked and looked, but no matter how many times I went through them, all I could see was his shadow caught on the edge of frame in one shot. I even went through the negatives, holding them up to the light in case there was one of him that hadn’t been developed. There were more negatives than prints and I hoped one of these might reveal him, but they were blurred, out of focus, useless.

How could Nancy have brought those photographs into our house? Hiding them from me, allowing them to sit and fester in our home. They must have been there for years. Did she forget about them? Or did she take a risk, knowing that I might come across them one day? But it was too late. By the time I did, she was dead. I would never be able to talk to her about them. She should have destroyed them. If she wasn’t going to tell me, she should have destroyed them. Instead she had

left me to find them when I was a pathetic old man; long after the event; long after a time when I could have done anything about it.

One of the things I had most prized about Nancy was her honesty. How many times did she look through those pictures in private? And hide them again? I imagined her waiting for me to go out before looking through them; hiding them when I came home. Every time I took something out of the dresser, every time we played Scrabble, she knew they were there and didn’t say a word. I had always trusted her, but now I worried what else she might have hidden.

It is extraordinary how much strength anger gives one. I turned the house upside down searching for more secrets. I attacked our home as if it was the enemy. I went from room to room, ripping, spilling, tipping, making a godawful mess, but I found nothing else. The whole experience left me with the sensation that I had reached down into a blocked drain and was groping around in the sewage trying to clear it. Except there was nothing solid to get hold of. All I felt was soft filth, and it got into my skin and under my fingernails, and its stink invaded my nostrils, clinging to the hairs, soaking up into the tiny blood vessels and polluting my entire system.

A speck of dust lands on the pillow. No one else would hear it. Catherine does. She hears everything – her ears are wide open. She sees everything too. Even in the pitch-black. Her eyes have become accustomed to it. If Robert woke now he would be blind; Catherine isn’t. She watches his closed eyes: the twitching lids, the flickering lashes, and she wonders what is going on behind them. Is he hiding anything from her? Is he as good at it as she is? He is closer to her than anyone else and yet she has managed, over all these years, to keep him in the dark. It doesn’t matter how intimate they are, he just can’t see it and she finds that thought frightening. And by keeping everything locked up for so long she has made the secret too big to let out; like a baby that has grown too large to be delivered naturally, it will have to be cut out. The act of keeping the secret a secret has almost become bigger than the secret itself. Robert rolls on to his back and starts to snore so Catherine gently propels him on to his other side so