EX LIBRIS

VINTAGE CLASSICS

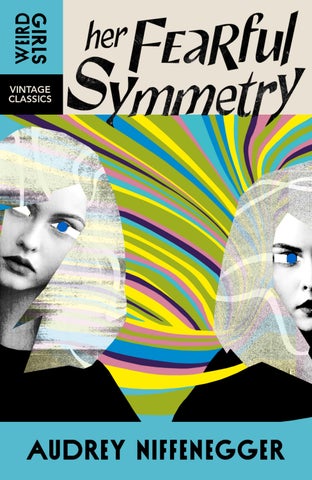

audrey niffenegger

Audrey Niffenegger is a visual artist and writer who lives in Chicago and London. Her book art, prints and paintings are included in the collections of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Newberry Library and the Library of Congress, among others. In 2019, she founded Artists Book House, a non-profit centre for the literary and book arts. Ms. Niffenegger was also one of the founders of the Columbia College Chicago Center for Book and Paper Arts. She was a Professor at Columbia College until 2015.

She has published eight books, including the novels The Time Traveler’s Wife and Her Fearful Symmetry, as well as the graphic novels Raven Girl, The Night Bookmobile and Bizarre Romance (with Eddie Campbell). The Time Traveler’s Wife has been adapted into a film, an HBO television series, and a West End stage musical. Other adaptations include a ballet of Raven Girl, which was created by the choreographer Wayne McGregor in 2013 for the Royal Opera House Ballet. Ms. Niffenegger’s new novel, a sequel to The Time Traveler’s Wife entitled The Other Husband, or, The Apocalypse Follows Me Everywhere Now, will be published in 2026.

also by audrey niffenegger

fiction

The Time Traveler’s Wife

Raven Girl

visual books

The Adventuress

The Spinster

Aberrant Abecedarium

The Murderer Spring

The Three Incestuous Sisters

The Night Bookmobile

Bizarre Romance

non-fiction

Awake in the Dream World: The Art of Audrey Niffenegger

anthologies

Ghostly: A Collection of Ghost Stories

audrey niffenegger

HER FEARFUL SYMMETRY

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © Audrey Niffenegger 2009

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This edition published in Vintage Classics in 2025

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape in 2009

SHE SAID, SHE SAID

© 1966 Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203. All rights reserved. Used by permission

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 9781529955637

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Jean Pateman, With Love.

She said, ‘I know what it’s like to be dead.

I know what it is to be sad.’

And she’s making me feel like I’ve never been born.

The

Beatles

PART O NE

The End

Elspeth died while Robert was standing in front of a vending machine watching tea shoot into a small plastic cup. Later he would remember walking down the hospital corridor with the cup of horrible tea in his hand, alone under the fluorescent lights, retracing his steps to the room where Elspeth lay surrounded by machines. She had turned her head towards the door and her eyes were open; at first Robert thought she was conscious.

In the seconds before she died, Elspeth remembered a day last spring when she and Robert had walked along a muddy path by the Thames in Kew Gardens. There was a smell of rotted leaves; it had been raining. Robert said, ‘We should have had kids,’ and Elspeth replied, ‘Don’t be silly, sweet.’ She said it out loud, in the hospital room, but Robert wasn’t there to hear. Elspeth turned her face towards the door. She wanted to call out, Robert, but her throat was suddenly full. She felt as though her soul were attempting to climb out by way of her oesophagus. She tried to cough, to let it out, but she only gurgled. I’m drowning. Drowning in a bed . . . She felt intense pressure, and then she was floating; the pain was gone and she was looking down from the ceiling at her small wrecked body.

Robert stood in the doorway. The tea was scalding his hand, and he set it down on the nightstand by the bed. Dawn

had begun to change the shadows in the room from charcoal to an indeterminate grey; otherwise everything seemed as it had been. He shut the door.

Robert took off his round wire-rimmed glasses and his shoes. He climbed into the bed, careful not to disturb Elspeth, and folded himself around her. For weeks she had burned with fever, but now her temperature was almost normal. He felt his skin warm slightly where it touched hers. She had passed into the realm of inanimate objects and was losing her own heat. Robert pressed his face into the back of Elspeth’s neck and breathed deeply.

Elspeth watched him from the ceiling. How familiar he was to her, and how strange he seemed. She saw, but could not feel, his long hands pressed into her waist – everything about him was elongated, his face all jaw and large upper lip; he had a slightly beakish nose and deep-set eyes; his brown hair spilled over her pillow. His skin was pallorous from being too long in the hospital light. He looked so desolate, thin and enormous, spooned around her tiny slack body; Elspeth thought of a photograph she had seen long ago in National Geographic , a mother clutching a child dead from starvation. Robert’s white shirt was creased; there were holes in the big toes of his socks. All the regrets and guilts and longings of her life came over her. No, she thought. I won’t go. But she was already gone, and in a moment she was elsewhere, scattered nothingness.

The nurse found them half an hour later. She stood quietly, taking in the sight of the tall youngish man curled around the slight, dead, middle-aged woman. Then she went to fetch theorderlies.

Outside, London was waking up. Robert lay with his eyes closed, listening to the traffic on the high street, footsteps in the corridor. He knew that soon he would have to open his eyes, let go of Elspeth’s body, sit up, stand up, talk. Soon there would be the future, without Elspeth. He kept his eyes shut, breathed in her fading scent and waited.

Last Letter

The letters arrived every two weeks. They did not come to the house. Every second Thursday, Edwina Noblin Poole drove six miles to the Highland Park Post Office, two towns away from her home in Lake Forest. She had a PObox there, a small one. There was never more than one letter in it.

Usually she took the letter to Starbucks and read it while drinking a venti decaf soy latte. She sat in a corner with her back to the wall. Sometimes, if she was in a hurry, Edie read the letter in her car. After she read it she drove to the parking lot behind the hot-dog stand on 2nd Street, parked next to the dumpster and set the letter on fire. ‘Why do you have a cigarette lighter in your glove compartment?’ her husband, Jack, asked her. ‘I’m bored with knitting. I’ve taken up arson,’ Edie had replied. He’d let it drop.

Jack knew this much about the letters because he paid a detective to follow his wife. The detective had reported no meetings, phone calls or email; no suspicious activity at all, except the letters. The detective did not report that Edie hadtaken to staring at him as she burned the letters, thengrinding the ashes into the pavement with her shoe. Once she’d given him the Nazi salute. He had begun to dreadfollowing her.

There was something about Edwina Poole that disturbed the detective; she was not like his other subjects. Jack had

emphasised that he was not gathering evidence for a divorce. ‘I just want to know what she does,’ he said. ‘Something is . . . different.’ Edie usually ignored the detective. She said nothing to Jack. She put up with it, knowing that the overweight, shinyfaced man had no way of finding her out.

The last letter arrived at the beginning of December. Edie retrieved it from the post office and drove to the beach in Lake Forest. She parked in the spot farthest from the road. It was a windy, bitterly cold day. There was no snow on the sand. Lake Michigan was brown; little waves lapped the edges of the rocks. All the rocks had been carefully arranged to prevent erosion; the beach resembled a stage set. The parking lot was deserted except for Edie’s Honda Accord. She kept the motor running. The detective hung back, then sighed and pulled into a spot at the opposite end of the parking lot.

Edie glanced at him. Must I have an audience for this? She sat looking at the lake for a while. I could burn it without reading it. She thought about what her life might have been like if she had stayed in London; she could have let Jack go back to America without her. An intense longing for her twin overcame her, and she took the envelope out of her purse, slid her finger under the flap and unfolded the letter.

Dearest e,

I told you I would let you know – so here it is – goodbye. I try to imagine what it would feel like if it was you –but it’s impossible to conjure the world without you, even though we’ve been apart so long.

I didn’t leave you anything. You got to live my life. That’s

enough. Instead I’m experimenting – I’ve left the whole lot to the twins. I hope they’ll enjoy it.

Don’t worry, it will be okay.

Say goodbye to Jack for me.

Love, despite everything, e

Edie sat with her head lowered, waiting for tears. None came, and she was grateful; she didn’t want to cry in front of the detective. She checked the postmark. The letter had been mailed four days ago. She wondered who had posted it. A nurse, perhaps.

She put the letter into her purse. There was no need to burn it now. She would keep it for a little while. Maybe she would just keep it. She pulled out of the parking lot. As she passed the detective, she gave him the finger.

Driving the short distance from the beach to her house, Edie thought of her daughters. Disastrous scenarios flitted through Edie’s mind. By the time she got home she was determined to stop her sister’s estate from passing to Julia and Valentina.

Jack came home from work and found Edie curled up on their bed with the lights off.

‘What’s wrong?’ he asked.

‘Elspeth died,’ she told him.

‘How do you know?’

She handed him the letter. He read it and felt nothing but relief. That’s all, he thought. It was only Elspeth all along. He climbed onto his side of the bed and Edie rearranged herself

around him. Jack said, ‘I’m sorry, baby,’ and then they said nothing. In the weeks and months to come, Jack would regret this; Edie would not talk about her twin, would not answer questions, would not speculate about what Elspeth might have bequeathed to their daughters, would not say how she felt or let him even mention Elspeth. Jack wondered, later, if Edie would have talked to him that afternoon, if he had asked her. If he’d told her what he knew, would she have shut him out? It hung between them, afterwards.

But now they lay together on their bed. Edie put her head on Jack’s chest and listened to his heart beating. ‘Don’t worry, it will be okay’ . . . I don’t think I can do this. I thought I would see you again. Why didn’t I go to you? Why did you tell me not to come? How did we let this happen? Jack put his arms around her. Was it worth it? Edie could not speak.

They heard the twins come in the front door. Edie disentangled herself, stood up. She had not been crying, but she went to the bathroom and washed her face anyway. ‘Not a word,’ she said to Jack as she combed her hair.

‘Why not?’

‘Because.’

‘Okay.’ Their eyes met in the dresser mirror. She went out, and he heard her say, ‘How was school?’ in a perfectly normal voice. Julia said, ‘Useless.’ Valentina said, ‘You haven’t started dinner?’ and Edie replied, ‘I thought we might go to Southgate for pizza.’ Jack sat on the bed feeling heavy and tired. As usual, he wasn’t sure what was what, but at least he knew what he was having for dinner.

A Flower of the Field

Elspeth Noblin was dead and no one could do anything for her now except bury her. The funeral cortège passed through the gates of Highgate Cemetery quietly, the hearse followed by ten cars full of rare-book dealers and friends. It was a very short ride; St Michael’s was just up the hill. Robert Fanshaw had walked down from Vautravers with his upstairs neighbours, Marijke and Martin Wells. They stood in the wide courtyard on the west side of the cemetery watching the hearse manoeuvring through the gates and up the narrow path towards the Noblin family’s mausoleum.

Robert was exhausted and numb. Sound seemed to have fallen away, as though the audio track of a movie had malfunctioned. Martin and Marijke stood together, slightly apart from him. Martin was a slender, neatly made man with greying close-cropped hair and a pointed nose. Everything about him was nervous and quick, knobbly and slanted. He had Welsh blood and a low tolerance for cemeteries. His wife, Marijke, loomed over him. She had an asymmetrical haircut, dyed bright magenta, and matching lipstick; Marijke was big-boned, colourful, impatient. The lines in her face contrasted with her modish clothing. She watched her husband apprehensively.

Martin had closed his eyes. His lips were moving. A stranger might have thought that he was praying, but Robert and Marijke knew he was counting. Snow fell in fat flakes that

vanished as soon as they hit the ground. Highgate Cemetery was dense with dripping trees and slushy gravel paths. Crows flew from graves to low branches, circled and landed on the roof of the Dissenters’ chapel, which was now the cemetery’s office.

Marijke fought the urge to light a cigarette. She had not been especially fond of Elspeth, but she missed her now. Elspeth would have said something caustic and funny, would have made a joke of it all. Marijke opened her mouth and exhaled and her breath hung for a moment like smoke in theair.

The hearse glided up the Cuttings Path and disappeared from sight. The Noblin mausoleum was just past Comfort’s Corners, near the middle of the cemetery; the mourners would walk up the narrow, tree-root-riddled Colonnade Path and meet the hearse there. People parked their cars in front of the semicircular Colonnade, which divided the courtyard from the cemetery, extricated themselves and stood looking about, taking in the chapels (once famously described as ‘Undertaker’s Gothic’), the iron gates, the War Memorial, the statue of Fortune staring blank-eyed under the pewter sky. Marijke thought of all the funerals that had passed through the gates of Highgate. The Victorians’ black carriages pulled by ostrich-plumed horses, with professional mourners and inexpressive mutes, had given way to this motley collection of autos, umbrellas and subdued friends. Marijke suddenly saw the cemetery as an old theatre: the same play was still running, but the costumes and hairstyles had been updated.

Robert touched Martin’s shoulder, and Martin opened his

eyes with the expression of a man abruptly woken. They walked across the courtyard and through the opening in the centre of the Colonnade, up the mossy stairs into the cemetery.

Marijke walked behind them. The rest of the mourners followed. The paths were slippery, steep and stony. Everyone watched their feet. No one spoke.

Nigel, the cemetery’s manager, stood next to the hearse, looking very dapper and alert. He acknowledged Robert with a restrained smile, gave him a look that said, It’s different when it’s one of our own, isn’t it? Robert’s friend Sebastian Morrow stood with Nigel. Sebastian was the funeral director; Robert had watched him working before, but now Sebastian seemed to have acquired an extra dimension of sympathy and inner reserve. He appeared to be orchestrating the funeral without actually moving or speaking; he occasionally glanced at the relevant person or object and whatever needed doing was done. Sebastian wore a charcoal-grey suit and a forest-green tie. He was the London-born son of Nigerian parents; with his dark skin and dark clothes he was both extremely present and nearly invisible in the gloom of the overgrown cemetery.

The pall-bearers gathered around the hearse.

Everyone was waiting, but Robert walked up the main path to the Noblin family’s mausoleum. It was limestone with only the surname carved above the oxidised copper door. The door featured a bas-relief of a pelican feeding her young with her own blood, a symbol of the Resurrection. Robert had occasionally included it on the tours he gave of the cemetery. The door stood open now. Thomas and Matthew, the burial team, stood waiting ten feet along the path, in front of a granite

obelisk. He met their eyes; they nodded and walked over to him.

Robert hesitated before he looked inside the mausoleum. There were four coffins – Elspeth’s parents and grandparents – and a modest quantity of dust which had accumulated in the corners of the small space. Two trestles had been placed next to the shelf where Elspeth’s coffin would be. That was all. Robert fancied that cold emanated from the inside of the mausoleum, as though it were a fridge. He felt that some sort of exchange was about to take place: he would give Elspeth to the cemetery, and the cemetery would give him . . . what, he didn’t know. Surely there must be something. He walked with Thomas and Matthew back to the hearse. Elspeth’s coffin was lead-lined, for above-ground burial, so it was incongruously heavy. Robert and the other pall-bearers shouldered it and then conveyed it into the tomb; there was a moment of awkwardness as they tried to lower it onto the trestles. The mausoleum was too small for all the pall-bearers, and the coffin seemed to have grown suddenly huge. They got it situated. The dark oak was glossy in the weak daylight. Everyone filed out except Robert, who stood hunched over slightly with his palms pressed against the top of the coffin, as though the varnished wood were Elspeth’s skin, as though he might find a heartbeat in the box that housed her emaciated body. He thought of Elspeth’s pale face, her blue eyes, which she would open wide in mock surprise and narrow to slits when she disliked something; her tiny breasts, the strange heat of her body during the fevers, the way her ribs thrust out over her belly in the last months of her illness, the scars from

the port and the surgery. He was flooded with desire and revulsion. He remembered the fine texture of her hair, how she had cried when it fell out in handfuls, how he had run his hands over her bare scalp. He thought of the curve of Elspeth’s thighs, and of the bloating and putrefaction that were already transforming her, cell by cell. She had been forty-four years old.

‘Robert.’ Jessica Bates stood next to him. She peered at him from under one of her elaborate hats, her stern face softened by pity. ‘Come, now.’ She placed her soft, elderly hands over his. His hands were sweating, and when he lifted them he saw that he’d left distinct prints on the otherwise perfect surface. He wanted to wipe the marks away, and then he wanted to leave them there, a last proof of his touch on this extension of Elspeth’s body. He let Jessica lead him out of the tomb and stood with her and the other mourners for the burial service.

‘The days of man are but as grass: for he flourisheth as a flower of the field. For as soon as the wind goeth over it, it is gone: and the place thereof shall know it no more.’

Martin stood on the periphery of the group. His eyes were closed again. His head was lowered, and he clenched his hands in the pockets of his overcoat. Marijke leaned against him. She had her arm through his; he seemed not to notice and began to rock back and forth. Marijke straightened herself and let him rock.

‘ Forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God of his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear sister here departed, wetherefore commit her body to its resting place; earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust; in sure and certain hope of the resurrection to

eternal life through Our Lord Jesus Christ; who shall change the body of our low estate that it may be like unto his glorious body, according to the mighty working, whereby he is able to subdue all things to himself. ’

Robert let his eyes wander. The trees were bare – Christmas was three weeks away – but the cemetery was green. Highgate was full of holly bushes, sprouted from Victorian funeral wreaths. It was festive, if you could manage the mind-flip required to think about Christmas in a cemetery. As he tried to focus on the vicar’s words he heard foxes calling to each other nearby.

Jessica Bates stood next to Robert. Her shoulders were straight and her chin was high, but Robert sensed her fatigue. She was Chairman of the Friends of Highgate Cemetery, the charity that took care of this place and ran the guided tours. Robert worked for her, but he thought she would have come to Elspeth’s funeral anyway. They had liked each other. Elspeth had always brought an extra sandwich for Jessica when she came to have lunch with Robert.

He panicked: How will I remember everything about Elspeth? Now he was full of her smells, her voice, the hesitation on the telephone before she said his name, the way she moved when he made love to her, her delight in impossibly high-heeled shoes, her sensuous manner when handling old books and her lack of sentiment when she sold them. At this moment he knew everything he would ever know of Elspeth, and he urgently needed to stop time so that nothing could escape. But it was too late; he should have stopped when she did; now he was running past her, losing her. She was already fading.

I should write it all down . . . but nothing would be adequate. Nothing I can write would bring her back.

Nigel closed the mausoleum door and locked it. Robert knew that the key would sit in a numbered compartment in a drawer in the office until it was needed again. There was an awkward pause; the service was over, but no one quite knew what to do next. Jessica squeezed Robert’s shoulder and nodded to the vicar. Robert thanked him and handed him an envelope.

Everyone walked together down the path. Soon Robert found himself standing again in the courtyard. The snow had turned to rain. A flock of black umbrellas opened almost at once. People got into cars, began to proceed out of the cemetery. The staff said things, hands patted him, there were offers of tea, something stronger; he didn’t quite know what he said to people, but they tactfully withdrew. The booksellers all went off to the Angel. He saw Jessica standing at the office window, watching him. Marijke and Martin had been standing apart; now they came to meet him. Marijke was leading Martin by the arm. His head was still bowed and he seemed to be intent on each sett in the courtyard as he walked across it. Robert was touched that he had managed to come at all. Marijke took Robert’s arm, and the three of them walked out of the cemetery and up Swains Lane. When they reached the top of Highgate Hill they turned left, walked for a few minutes and turned left again. Marijke had to let go of Robert in order to hurry Martin along. They walked down a long narrow asphalt path. Robert opened the gate, and they were home. All three apartments in Vautravers were dark, and the day was giving

way to evening so that the building seemed to Marijke even more heavy and oppressive than usual. They stood together in the entrance hall. Marijke gave Robert a hug. She didn’t know what to say. They had already said all those things, and so she said nothing and Robert turned to let himself into hisflat.

Martin’s voice came out hoarse. He said, ‘Sorry.’ The word startled each of them. Robert hesitated and nodded. He waited to see if Martin would say anything else. The three of them stood together awkwardly until Robert nodded again and disappeared into his flat. Martin wondered if he had been right to speak. He and Marijke began to climb the stairs. They paused on the second landing as they passed Elspeth’s door. There was a small typed card tacked to it that said NOBLIN. Marijke reached out and touched it as she passed. It reminded her of the name on the mausoleum. She thought that it would every time she went by it, now.

Robert took his shoes off and lay on his bed in his austere and nearly dark bedroom, still wearing his wet woollen coat. He stared at the ceiling and thought of Elspeth’s flat above him. He imagined her kitchen, full of food she would not eat; her clothes, books, chairs which would not be worn or read or sat in; her desk stuffed with papers he needed to go through. There were many things he needed to do, but not now.

He was not ready for her absence. No one he loved had died, until Elspeth. Other people were absent, but no one was dead. Elspeth? Even her name seemed empty, as though it had detached itself from her and was floating untethered in his mind. How am I supposed to live without you? It was not a matter

of the body; his body would carry on as usual. The problem was located in the word how: he would live, but without Elspeth the flavour, the manner, the method of living were lost to him. He would have to relearn solitude.

It was only four o’clock. The sun was setting; the bedroom became indistinct in shadow. He closed his eyes, waited for sleep. After some time he understood that he would not sleep; he got up and put on his shoes, went upstairs and opened Elspeth’s door. He walked through her flat without turning on any lights. In her bedroom he took his shoes off again, removed his coat, thought for a moment and took off the rest of his clothing. He got into Elspeth’s bed, the same side he had always slept on. He put his glasses in the same spot theyhad always occupied on the nightstand. He curled into his accustomed position, slowly relaxing as the chill left the sheets. Robert fell asleep waiting for Elspeth to come to bed.

She’s Leaving Home

Marijke Wells de Graaf stood in the doorway of the bedroomshe had shared with Martin for the last twenty-three years. She had three letters in her hand, and she was debating with herself about where to leave one of them. Her suitcases stood on the landing by the front stairs with her yellow trench coat neatly folded over them. She had only to leave the letter and she could go.

Martin was in the shower. He had been in there for about twenty minutes; he would stay in the shower for another hour or so, even after the hot water ran out. Marijke made a point of not knowing what he was up to in there. She could hear him talking to himself, a low, amiable mumble; it could almost have been the radio. This is Radio Insanity, she thought, coming at you with all the latest and greatest OCDhits.

She wanted to leave the letter in a place where he would find it soon, but not too soon. And she wanted to leave it in a spot that wasn’t already problematic for Martin, so that he’d be able to pick the letter up and open it. But she didn’t want to put it in a place which would be contaminated by the presence of the letter, which would then be forever associated with the letter and therefore out of bounds to Martin in the future.

She’d been pondering this dilemma for weeks without settling on a spot. She’d almost given up and resolved to postthe letter, but she didn’t want Martin to worry when she

didn’t come home from work. I wish I could leave it hovering in midair, she thought. And then she smiled and went to get her sewing kit.

Marijke stood in Martin’s office next to his computer, trying to steady her hands enough to thread the needle in the pool of yellow light from his desk lamp. Their flat was very dark; Martin had papered over the windows and she could only tell that it was morning by the white light that showed through the Sellotape at the edges of the newspaper. Needle threaded, she whipped a few stitches around the edge of the envelope and then stood on Martin’s chair to tape the end of the thread to the ceiling. Marijke was tall, but she had to stretch, and for a moment she had a sensation of vertigo, wobbling on the chair in the dark room. It would be a bad joke if I fell and broke myself now. She imagined herself on the floor with her head cracked open, the letter dangling above her. But a second later she recovered her balance and stepped off the chair. The letter seemed to levitate above the desk. Perfect. She gathered her sewing things and pushed in the chair.

Martin called her name. Marijke stood frozen. ‘What?’ she finally called out. She set the sewing supplies on Martin’s desk. Then she walked into the bedroom and stood at the closed bathroom door. ‘What?’ She held her breath; she hid the remaining two letters behind her back.

‘There’s a letter for Theo on my desk; could you post it on your way out?’

‘Okay.’

‘Thanks.’

Marijke opened the door a crack. Steam filled the bathroom and moistened her face. She hesitated. ‘Martin . . .’

‘Hmm?’

Her mind went blank. ‘Tot ziens, Martin,’ she finally said. ‘Tot ziens, my love.’ Martin’s voice was cheerful. ‘See you tonight.’

Tears welled in her eyes. She walked slowly out of the bedroom, edged her way between the piles of plastic-wrapped boxes in the hall, ducked into the office, picked up Martin’s letter to Theo and continued through the front hall and out the door of their flat. Marijke stood with her hand on the doorknob. A random memory came to her: We stood here together, my hand on the doorknob just like this. A younger hand; we were young. It was raining. We’d been grocery shopping. Marijke closed her eyes and stood listening. The flat was large, and she couldn’t hear Martin from here. She left the door ajar (it was never locked) and put on her coat, checked her watch. She hefted her suitcases and carried them awkwardly down the stairs, glancing briefly at Elspeth’s door as she went by. When she came to the ground floor she left one of her envelopes in Robert’s mail basket.

Marijke did not turn to look at Vautravers as she let herself out of the gate. She walked up the path to the street, rolling her suitcases behind her. It was a cold damp January morning; it had rained in the night. Highgate Village had a feeling of changelessness about it this morning, as though no time at all had passed since she’d arrived there, a young married woman, in 1981. The red phone box still stood in Pond Square, though there was no pond in Pond Square now, nor had there

been for as long as Marijke could remember, just gravel and benches with pensioners napping on them. The old man who owned the bookshop still scrutinised the tourists as they perused his obscure maps and brittle books. A yellow Labrador ran across the square, easily eluding a shrieking toddler. The little restaurants, the dry-cleaners, the estate agents, the chemist – all waited, as though a bomb had gone off somewhere, leaving only young mums pushing prams. As she posted Martin’s letter to him, along with her own, Marijke thought of the hours she’d spent here with Theo. Perhaps they’ll arrive together .

The driver was waiting for her at the minicab office. He slung her suitcases into the boot and they got into the car. ‘Heathrow?’ he asked. ‘Yes, Terminal Four,’ said Marijke. They headed down North Hill toward the Great North Road.

Somewhat later, as Marijke queued at the KLMdesk, Martin got out of the shower. A spectator unfamiliar with Martin might have worried about his appearance: he was bright red, as though a superhuman housewife had parboiled him to extract impurities.

Martin felt good. He felt clean. His morning shower was a high point of his day. His worries receded; troubling things could be tackled in the shower; his mind was clear. The shower he took just before teatime was less satisfactory because it was shorter, crowded by intrusive thoughts and Marijke’s imminent return from her job at the BBC. And the shower he took before going to bed was afflicted by anxieties about being in bed with Marijke, worries about whether he smelled funny,

and would she want to have sex tonight or put him off until some other night? (there had been less and less sex lately) not to mention worries about his crossword puzzles, about emails written and emails unanswered, worries about Theo off at Oxford (who always supplied less detail about his daily life and girlfriends and thoughts than Martin would have liked; Marijke said, ‘He’s nineteen, it’s a miracle he tells us anything,’ but somehow that didn’t help and Martin imagined all sorts of awful viruses and traffic accidents and illegal substances; recently Theo had acquired a motorcycle – many, many rituals had been added to Martin’s daily load in order to keep Theo safe and sound).

Martin began to towel himself. He was an avid observer of his own body, noting every corn, vein and insect bite with deep concern – and yet he had hardly any idea what he actually looked like. Even Marijke and Theo existed only as bundles of feelings and words in Martin’s memory. He wasn’t good at faces.

Today everything proceeded smoothly. Many of Martin’s washing and grooming rituals were organised around the idea of symmetry: a stroke of the razor on the left required an identical stroke on the right. There had been a bad period a few years ago when this had led to Martin shaving every trace of hair from his entire body. It took hours each morning, and Marijke had wept at the sight of him. He had eventually persuaded himself that extra counting could be substituted for all that shaving. So this morning he counted the razor strokes (thirty) required to actually shave his beard, and then deliberately put the razor down on the sink and counted to

thirty thirty times. It took him twenty-eight minutes. Martin counted quietly, without hurrying. Hurrying always mucked things up. If he tried to rush he wound up having to start again. It was important to do it well, so that it felt complete.

Completeness: when done correctly, Martin derived a (fleeting) satisfaction from each series of motions, tasks, numbers, washing, thoughts, not-thoughts. But it would not do to be too satisfied. The point was not to please himself, but to stave off disaster.

There were the obsessions – these were like pinpricks, prods, taunts: Did I leave the gas on? Is someone looking in the backdoor window? Perhaps the milk was off. Better smell it again before I put it in the tea. Did I wash my hands after taking a piss? Better do it again, just to be sure. Did I leave the gas on? Did my trousers touch the floor when I put them on? Do it again, do it right. Do it again. Do it again. Again. Again.

The compulsions were answers to the questions posed by the obsessions. Check the gas. Wash my hands. Wash them very thoroughly, so there can be no mistake. Use stronger soap. Use bleach. The floor is dirty. Wash it. Walk around the dirty part without touching it. Use as few steps as possible. Spread towels over the floor to keep the contamination from spreading. Wash the towels. Again. Again. It feels wrong to enter the bedroom this way. Wrong how, exactly? Just wrong. Do it right foot first. And turn to the left with my body – there, that’s it. That feels better. But what about Marijke? She has to do it this way too. She won’t like it. Doesn’t matter. She won’t do it. She will. She has to. It feels too wrong if she doesn’t. As though something dreadful will happen. What, exactly? Don’t know. Can’t think about it. Quick –multiples of 22: 44, 66, 88 . . . 1,122 . . .

There were good days, bad days, very bad days. Today was shaping up to be a good day. Martin thought about his time at Balliol, when he had played tennis every Wednesday with a bloke from his Philosophy of Mathematics course. There were days when he knew, even before he unpacked his racquet, that every stroke would be sweet. Today had that feeling about it.

Martin opened the bathroom door and surveyed the bedroom. Marijke had laid out his clothes on the bed. His shoes sat on the floor, neatly aligned with the legs of his trousers. Every article of clothing was arranged in a precise pattern. No piece of clothing touched any other. He contemplated the hardwood floor of the bedroom. There were spots where the finish of the wood had been worn away, places where the floor was warped from moisture – but Martin disregarded all that. He was trying to discern whether the floor was safe to walk on in his bare feet. Today, he decided that it was. Martin strode to the bed and began to dress himself very slowly.

As each piece of clothing settled onto his body, Martin felt increasingly secure, enveloped in the clean, worn fabric. He was very hungry, but he took his time. Eventually, Martin slid his feet into his shoes. The shoes were problematic. The brown Oxfords were a sort of negotiation between his clean body and the always unnerving floor. He disliked touching them. But he did, and managed to tie the laces. Marijke had offered to get him trainers with Velcro straps, but Martin felt aesthetically repelled by the very idea.

Martin always dressed in sober, dark clothing; he exuded

formality. He did not go so far as to wear a tie around the flat, but he always looked as though he had just removed one, or was looking for a tie to put on before he rushed out the door. Since he had stopped leaving the flat, his ties stayed on the rack in his wardrobe.

Dressed, Martin walked cautiously through the hall and into the kitchen. His breakfast was laid out on the kitchen table. Weetabix in a bowl, a small jug of milk, two apricots. He pressed the button on the electric kettle, and in a few minutes the water boiled. Martin had few compulsions associated with food (they mainly involved chewing things a certain number of times). The kitchen was Marijke’s domain, and she always made him take whatever was bothering him to another part of the flat. He tried never to turn on the stove, because he found it impossible to be sure that he’d turned it off again and would stand for hours with his hand on the knob, turning it back and forth. But he could make tea with the electric kettle, and he did so.

Marijke had left the newspapers next to his bowl of cereal. They were pristine, still neatly folded. Martin felt a little surge of gratitude – he liked to be the first to open the fresh newspapers, but he never got to them before she did. He unfurled the Guardian and went directly to the crossword.

Today was Thursday, and for Thursdays Martin always set a crossword with a scientific theme. This particular one concerned astronomy. Martin scanned it briefly to be sure that everything was correct. He was especially proud of the puzzle’s form, which sprawled across the grid in the shape of a rather boxy and completely symmetrical spiral galaxy. He then turned

to the solution for yesterday’s puzzle, a strict Ximenean which had been set by his fellow compiler Albert Beamish. Beamish set under the name Lillibet; Martin had no idea why. He’d never met Beamish, though they spoke on the phone occasionally. Martin always imagined him as a hairy man in a ballet costume. Martin’s own setting name was Bunbury.

Martin opened The Times, the Daily Telegraph, the Daily Mail and the Independent and began combing through them for interesting news items. The crossword he was working on at the moment was about the history of warfare in Mesopotamia. He wasn’t sure if this was going to fly with his editor, but like any artist he felt the need to express his preoccupations through his work, and Iraq had been much on Martin’s mind lately. Today the news was full of an especially bloody suicide bombing in a mosque. Martin sighed, got his scissors and began cutting out the articles.

After breakfast, he washed up (in a fairly normal fashion) and stacked the papers neatly (though they had become somewhat lace-like). He went into his office, bent over to turn on the desk lamp. As he straightened up something brushed his face.

Martin’s first thought was that a bat had somehow got into the office. But then he saw the envelope, swinging gently on its thread, hanging from the ceiling. He stood and considered it. His name was written on it in Marijke’s boldhandwriting. What have you done? His mind went blank, and he stood in front of the dangling envelope with his head bowed and his arms crossed protectively over his chest. At last he reached out and took it, giving a little tug that detached thethread from the ceiling. He opened it slowly, unfolded the

letter, groped for his reading glasses and put them on. What has she done?

6 January

Lieve Martin,

My darling husband, I am sorry. I cannot live this way any more. By the time you are reading this letter I will be on my way to Amsterdam. I have written to Theo to tell him.

I don’t know if you can understand, but I will try to explain. I need to live my life without being always vigilant to calm your fears. I am tired, Martin. You have worn me out. I know that I will be lonely without you, but I will be more free. I will find myself a little apartment and open the windows and let the sun and the air come in. Everything will be painted white, and I will have flowers in all the rooms. I will not have to always enter the rooms with my right foot first, or smell bleach on my skin, on everything I touch. My things will be in their cupboards and drawers, not in Tupperware, not wrapped in cling film. My furniture will not wear out from being scrubbed too much. Maybe I will have a cat.

You are ill, Martin, but you refuse to see a doctor. I am not coming back to London. If you want to see me, you can come to Amsterdam. But first you would have to leave the flat, so I am afraid that we may never see each other again. I tried to stay but I failed.

Be well, my love.

Marijke

Martin stood holding the letter. The worst thing has happened. He could not take it in. She’s gone. She would not come back. Marijke. He bent slowly at his waist, hips, knees, until he was crouching on the floor in front of his desk, the harsh light shining on his back, his face inches from the letter. My love. Oh my love . . . All thought fled from him; there was only a great emptiness, the way the water draws back before a tsunami. Marijke.

Marijke sat on the train, watching the flat grey land along the track from Schiphol Airport as it blurred past her. It had been raining; the sky was low. I’m almost home. She checked her watch. By now Martin must have found her letter. She took her mobile phone out of her bag and opened it. No calls. She snapped it shut. The rain streaked sideways across the train’s windows. What have I done? I’m sorry, Martin. But she knew she would not be sorry once she was home, and only Amsterdam could be home to her now.

February

Robert had given a special tour of the Western Cemetery to a group of antiquarians from Hamburg, and now he stood under the arch by Highgate Cemetery’s main gate, waiting for his group to buy postcards and collect their belongings so he could shoo them out and lock up. In the winter there were no regular weekday tours. He liked the subdued, workaday quality the cemetery had on these quiet days.

The antiquarians straggled out of the former Anglican chapel that served as a makeshift gift shop. Robert shook the green plastic donation box at them, and they threw in their change. He always felt embarrassed at this little transaction, but the cemetery didn’t pay VATon donations, so everyone at Highgate begged as enthusiastically as they could manage.

Robert smiled and waved the Germans out, then turned the old-fashioned key in the massive gate’s lock.

He went into the office and put the key and the donation box on the desk. Felicity, the office manager, smiled and dumped out the contents. ‘Not bad, for such a dreary Wednesday,’ she said. She held out her hand. ‘Walkie-talkie?’

Robert patted his mackintosh pocket and said, ‘I’ll bring it back.’

‘Are you going out, then?’ Felicity asked. ‘It’s starting to rain.’

‘Just for a bit.’

‘Molly’s on the gate across the way. Could you give her these?’

‘Okay.’

Robert took the pamphlets from Felicity and an umbrella from the stand by the stairs. He headed across Swains Lane. Molly, a lean elderly woman who wore green dungarees and an anorak, sat on a folding chair inside the Strathcona and Mount Royal memorial, which lurked in pink granite splendour just beside the Eastern Cemetery’s gate. She peered out of the gloom patiently and took the pamphlets from Robert, tucking them into the little rack that sat beside her. The pamphlets featured Karl Marx on their covers; he and George Eliot were the star attractions among the dead on this side of the cemetery.

‘D’you want to go in and warm up?’ Robert asked her.

Molly’s voice was slow, raspy, sleepy; she had a slight Australian accent. ‘I’m all right – I’ve got the heater on. Have you had your visit?’

‘No, I just got done with the tour.’

‘Well go on, then.’

As he recrossed Swains Lane, Robert thought about the way Molly had said ‘your visit’ as though it were now part of the official daily schedule of the cemetery. Perhaps it was. Hethought about the way the staff had made space for his griefasif it were a tangible thing. Out in the world people drew back from it, but at the cemetery everyone was accustomed to the presence of the bereaved, and so they were matter-of-fact about death in a way that Robert had never appreciated until now.

The drizzle turned to rain as Robert came to Elspeth’s mausoleum. He put up his umbrella with a flourish and sat down on the steps with his back against the door. Robert leaned his head back and closed his eyes. Less than an hour ago he had walked right past this spot with his tour. He had been chatting to the group about wakes and the extreme measures the Victorians had taken for fear of being buried alive. He wished that the Noblin tomb was not on one of the main paths; it was impossible to give a tour without passing Elspeth, and he felt callous leading groups of gawking tourists past the small structure with her surname carved into it. It had never bothered him when it was only her family’s grave – but he had never met her family. For the first time he properly understood why Jessica was so adamant about decorum in the cemetery. He had been inclined to tease her about that. For Jessica, Highgate was not about the tours, or the monuments, not about the supernatural or the atmosphere or the morbid peculiarities of the Victorians; for her, the cemetery was about the dead and their grave owners. Robert was working, rather slowly, on a history of Highgate Cemetery and Victorian funerary practices for his doctoral thesis. But Jessica, who never wasted anything and was supremely adept at putting people to work, had said, ‘If you’re going to do all that research, why don’t you make yourself useful?’ So he began to lead tours. He found that he liked the cemetery itself much better than anything he wrote about it.

Robert settled into himself. The stone step he sat on was cold, wet and shallow. His knees jutted up almost to shoulder height. ‘Hello, love,’ he said, but as always felt absurd speaking

out loud to a mausoleum. Silently he continued: Hello. I’m here. Where are you? He pictured Elspeth sitting inside the mausoleum like a saint in her hermitage, looking out at him through the grate in the door with a little smile on her face. Elspeth?

She had always been a restless sleeper. When she was alive her sleep was punctuated by tossing and turning; she often stole all the blankets. When Elspeth slept alone shelay spreadeagled across the bed, staking her territory with limbs instead of a flag. When she slept with Robert he was often awoken by a stray elbow or knee, or by Elspeth’s legs thrashing as though she were running in bed. ‘One of these nights you’re going to break my nose,’ he’d said to her. She had acknowledged that she was a dangerous bed mate. ‘I apologise in advance for any breakage,’ she’d told him, and kissed the nose in question. ‘You’ll look good, though. It’ll add a certain hooliganish glamour to you.’

Now there was only stillness. The door was a barrier he could have passed through; there was a key in Elspeth’s desk, in addition to the one in the cemetery office. Elspeth’s bodysatin a box a few feet away from him. He chose not to imagine what three months had done to it.

Robert was struck once again by the finality of it all, summed up and presented to him as the silence in the little room behind him. I have things to tell you.Are you listening? He had never realised, while Elspeth was alive, the extent to which a thing had not completely happened until he told her about it.

Roche sent the letter to Julia and Valentina yesterday. Robert

imagined the letter making its way from Roche’s office in Hampstead to Lake Forest, Illinois, USA, being dropped through the letter box at 99 Pembridge Road, being picked up by one of the twins. It was a thick, creamy envelope with the return address of Roche, Elderidge, Potts & Lefley –Solicitors debossed in glossy black ink and the twins’ names and address written in the spidery handwriting of Roche’s ancient secretary, Constance. Robert imagined one of the twins holding the envelope, her curiosity. I’m nervous about this, Elspeth. I would feel better if you’d ever met these girls. You don’t have to live with them – they could be awful. Or what if they just sell the place to someone awful? But he was intrigued by the twins, and he had a certain irrational faith in Elspeth’s experiment. ‘I can leave it all to you,’ she’d said. ‘Or I can leave it to the girls.’

‘Let the girls have it,’ he had replied. ‘I have more than enough.’

‘Hmm. I will, then. But what can I give you?’

They were sitting on her hospital bed. She had a fever; it was after the splenectomy. Elspeth’s dinner sat untouched on the wheeled bedside table. He was massaging her feet, his hands slippery with the warm, fragrant oil. ‘I don’t know. Could you arrange to be reincarnated?’

‘The twins are rumoured to be pretty close copies.’ Elspeth smiled. ‘I’ll make them come and live in the flat if they want it. Shall I leave you the twins?’

Robert smiled back at her. ‘That could backfire. That could be quite . . . painful.’

‘You’ll never know if you don’t give it a whirl. But I want to give you something.’

‘A lock of hair?’

‘Oh, but it’s bad hair now,’ she said, fingering her downy silver fuzz. ‘We should have saved a bit when I still had my real hair.’ Elspeth’s hair had been longish, wavy, the colour of winter butter.

Robert shook his head. ‘It doesn’t matter. I just wanted something of you.’

‘Like the Victorians? It’s a pity it isn’t longer. You could make earrings or a brooch or something.’ She laughed. ‘You could clone me.’

He pretended to consider it. ‘But I don’t think they’ve worked all the bugs out of cloning. You might turn out morbidly obese, or flipper-limbed or whatnot. Plus I’d have to wait for you to grow up, by which time I’d be a pensioner and you’d want nothing to do with me.’

‘The twins are a much better bet. They’re fifty per cent me and fifty per cent Jack. I’ve seen photos, you really can’t see him in them at all.’

‘Where are you getting photos of the twins?’

Elspeth covered her mouth with her hand. ‘Edie, actually. But don’t tell anyone.’ Robert said, ‘Since when are you in touch with Edie? I thought you hated Edie.’

‘Hated Edie?’ Elspeth looked stricken. ‘No. I was very angry with Edie, and I still am. But I never hated Edie; that would be like hating myself. She just . . . she did something quite stupid that bollixed up our lives. But she’s still my twin.’ Elspeth hesitated. ‘I wrote to her about a year ago – when I first got diagnosed. I thought she ought to know.’

‘You didn’t tell me.’

‘I know. It was private.’

Robert knew it was childish to feel hurt. He didn’t say anything.

She said, ‘Ah, come on. If your father got in touch would you tell me all about it?’

‘I would, actually.’

Elspeth put her thumb in her mouth and bit gently. He had always found this highly sexual, a huge turn-on, but now it was somehow devoid of that power. She said, ‘Yes, of course you would.’

‘And what do you mean they are half you? They’re Edie’s kids.’

‘They are. They are her kids. But Edie and I are identical twins, so her kids equal my kids, genetically.’

‘But you’ve never even met them.’

‘Does it matter so much? All I can say is, you haven’t got a twin, so you can’t know how it is.’ Robert continued to sulk. ‘Oh, don’t. Don’t be that way.’ She tried to move towards him, but the tubes in her arms overruled her. Robert carefully set her feet on a towel, wiped his hands, got up and reseated himself on the arc of white sheet next to her waist. She took up almost no space at all. He placed one hand on her pillow, just beside her head, and leaned over her. Elspeth put her hand on his cheek. It was like being touched with sandpaper; her skin almost hurt him. He turned his head and kissed her palm. They had done all these things so many times before.

‘Let me give you my diaries,’ Elspeth said softly. ‘Then you’ll know all my secrets.’

He realised later that she had planned this all along. But

then he had only said, ‘Tell me all your secrets now. Are they so very terrible?’

‘Dreadful. But they’re all very old secrets. Since I met you I’ve lived a chaste and blameless life.’

‘Chaste?’

‘Well, monogamous, anyway.’

‘That’ll do.’ He kissed her, briefly. She was more feverish now. ‘You ought to sleep.’

‘Do my feet more?’ She was like a child asking for her favourite bedtime story. He resumed his place at her feet and squeezed more oil onto his hands, warmed it by rubbing it between his palms.

Elspeth sighed and closed her eyes. ‘Mmm,’ she said after a while, arching her feet. ‘That’s bloody marvellous.’ Then she had slept, and he’d sat there holding her slippery feet in his hands, thinking.

Robert opened his eyes. He wondered briefly if he had fallen asleep; the memory had been so vivid. Where are you, Elspeth? Perhaps you’re only living in my head now. Robert stared at the graves across the path, which were dangerously tilted. One had trees growing on both sides; they had lifted the monument slightly off its base so that it levitated an inch or so in the air. As Robert watched, a fox trotted through the ivy that choked the graves behind the ones on the main path. The fox saw him, paused for a moment and disappeared into the undergrowth. Robert heard other foxes howling to each other, some close by, some off in the deeper parts of the cemetery. It was the mating season. The daylight was going; Robert was chilled and wet. He roused himself.

‘Goodnight, Elspeth.’ He felt silly saying it. He got up and began to walk back to the office, feeling much the wayhe had as a teenager when he realised that he was no longer able to pray. Wherever Elspeth might be, she wasn’t here.