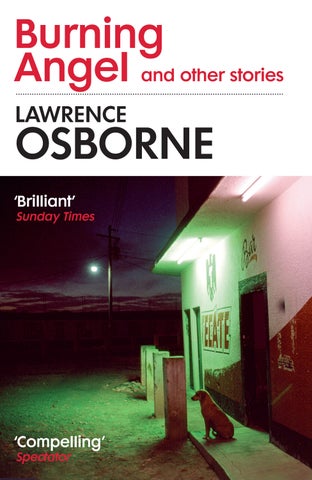

Burning Angel and

other stories

LAWRENCE OSBORNE

‘Brilliant’ SundayTimes

‘Compelling’ Spectator

PRAISE FOR LAWRENCE OSBORNE

‘A modern Graham Greene’ Sunday Times

‘Impossible to put down and beautifully written: a great combo’

Lionel Shriver

‘Surprising and dark and excellent’ New York Times

‘Osborne handles surface and depth with immense skill, as only great writers can’

Deborah Levy

‘Utterly compelling’ Observer

‘If the purpose of a novel is to take you away from the everyday and show you something different, then Osborne is succeeding, and handsomely’

Lee Child

‘As menacing and engrossing as the best McEwan’ Sunday Times

‘The author’s exceptional descriptive skills fuel an overwhelming sense of menace’

Louise Doughty

‘One of Britain’s very best novelists’ Mail on Sunday

LAWRENCE OSBORNE

Born in England, Lawrence Osborne is the author of the critically acclaimed novels The Forgiven, The Ballad of a Small Player, Hunters in the Dark, Beautiful Animals, Only to Sleep: A Philip Marlowe novel (commissioned by the Raymond Chandler estate), The Glass Kingdom and On Java Road. His non-fiction ranges from memoir through travelogue to essays, including Bangkok Days, The Naked Tourist and The Wet and the Dry. His short story ‘Volcano’ was selected for The Best American Short Stories 2012 and The Forgiven was made into a film starring Ralph Fiennes, Matt Smith and Jessica Chastain. Osborne lives in Bangkok.

ALSO BY LAWRENCE OSBORNE

Ania Malina

Paris Dreambook

The Poisoned Embrace

American Normal

The Accidental Connoisseur

The Naked Tourist

Bangkok Days

The Wet and the Dry

The Forgiven

The Ballad of a Small Player Hunters in the Dark

Beautiful Animals

Only to Sleep: A Philip Marlowe novel

The Glass Kingdom

On Java Road

LAWRENCE OSBORNE

Burning Angel

and Other Stories

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Vintage in 2024

First published in hardback by Hogarth in 2023

Copyright © Lawrence Osborne 2023

Lawrence Osborne has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

‘Camino Real’ was first published in the US in Tin House, Fall 2013; ‘Volcano’ was first published in the US in Tin House, Spring 2011, and also appeared in Best American Short Stories 2012 (ed. Tom Peretta, Mariner Books, New York, 2012); ‘Pig Bones’ was first published as ‘Kakua’ in the US by Fiction magazine no. 58, 2012; ‘The White Gods’ was first published in the New Statesman, December 2020.

penguin.co.uk/vintage

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529114966

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

FOR NICHOLAS SIMON

Boats against the current

GHOST

Near the top of the mountain, not far from the Victoria Peak Garden, Rowan Buford kept his company town house in the Overthorpe gated enclave. The $40,000-amonth rent had been paid by his employers, Gilby & Fitch, for seven years. His balcony overlooked the whole city, with glimpses of the South China Sea beyond, and his four bedrooms had accumulated over time artworks culled from nearly a decade of Christie’s auctions, especially works of the Hong Kong ‘New Ink’ movement. The American community called him ‘Party Hyena’ behind his back and yet all the clubs welcomed his membership, and his reckless reputation did not diminish his allure.

Buford, now thirty-seven, had successfully petitioned the building’s management to remove the tasteless decorative elephants from the development’s front doors, but he had failed to limit participation in the Overthorpe’s dismally claustrophobic communal pool. No matter. He belonged to two gyms in the city and shared a yacht moored in Aberdeen with a colleague of his own age. In the city’s foreign hedgefund world ‘the young sharks’, as they were known, constituted a small band – not of brothers, certainly, but at

least of loosely mutual acquaintances. Buford had his tennis comrades, his drinking band, his cigar circle, his wine club and his girlfriend Lily, a nance worker from Shenzhen ten years his junior. He had found ‘The Life’, and each part of that Life had a compartment that suited a hundred di erent and variable moods. It was the dividend o ered by quickly made wealth. What other city could pay those dividends so e ciently or let the earner enjoy them so completely? Buford had calculated at the beginning of his long stint at the rm that his town house on the Peak would place him in the middle of the highest real-estate prices in the world.

The Peak was more expensive than any real estate in human history. Knightsbridge or Central Park West and East were far down the mournful league table of dollars-persquare-foot. And the Overthorpe stood at the summit of the Peak, commanding in both the physical sense and in terms of its actual dollar value.

In the early morning he and Lily shared their croissants and cafetière with a little sni of coke to start their day, lounging in the white deckchairs designed to o set a black wooden oor. They could watch ships moving silently across the harbour, the sun rising over Tsim Sha Tsui. For an hour at dawn the city was quiet enough for them to talk without haste. An adventure trip to Siberia in the o ng, a week in California to meet his parents in Santa Ana. Investments, insider tips. Auctions perhaps, crypto trades, social gossip and small talk. Lily, a dutiful Chinese daughter, wondering how to buy her parents a new house. Buford explaining for the hundredth time his disdain for his superiors at the rm. His plans were tinged with a hard romanticism.

Secretly he was running up formidable debts, but these he kept to himself. It was nothing he couldn’t pay o with a concerted austerity push.

The maid would arrive at nine to clear up the shambolic mess inside the house where they had often been partying all night. Then they went their separate ways. Lily took the cable car down to Wang Chai to work at her mainlander bank, and Buford departed in a tracksuit for his morning run along the pathways and staircases cut through tropical forests, where he gradually worked o the e ects of the previous evening’s drugs. It was on these runs that he did his best thinking, arriving after a full circuit of the Peak at a lookout over the sea, where he sat above the forests for a while reading the papers at an outdoor café and making his rst call to the o ce at eight on the dot. His secretary, Natalie, would take this call and arrange his day. Then his driver would take him down to Sheung Wan directly from the Overthorpe and, after a morning’s trading, he would lunch at midday alone at The Chairman, where his table was always reserved.

Every morning was much the same until early April, one of the rst hot days when kestrels and sea-eagles had reappeared, circling the towers of the Peak. His secretary told him on the phone as he was waiting for the 8 a.m. car that the o ce was having a ‘reorganisation’ and that it would be more expedient, if he didn’t mind, if he could come in a little later that day and meet Alan Fitch for lunch at The Chairman instead. The limo reservation had been altered accordingly.

‘What do you mean, “reorganisation”?’ he said to her.

‘I think Mr Fitch will explain it to you.’

A little put out, Buford retired to his black balcony and

watched the kestrels while the maid cleaned up the takeaway cartons and the beer cans stained with lipstick from the main room. The sun had acquired its rst heat of the year, and the forests all around the complex had burst into wild colour as the bushes owered as if they had been activated overnight. There was a change in the atmosphere of some kind, a recalibration. Even his secretary’s voice was not as it normally was. He thought, My party habits got back to the big boys and they want to bust my balls about it. In his mind, accordingly, he prepared a de ant little speech that he would deliver to Fitch over their poached urchins at lunch. He would point out that in their amoral world only results mattered, not the occasional and entirely private abuse of cocaine. How could the senior partner demur? Buford could then issue a quick reassurance that, in the circumstances, he might be able to modify his behaviour a little. But had he not brought in eight million to the rm that year? The car came for him at eleven and on the way down he read the Financial Times, as he always did. The ongoing realestate crisis in China had nally made the front page. The ghost cities of the mainland were going bankrupt and the banks in Hong Kong were growing nervous. The tremors of a distant crisis were now being felt in a city that was becoming ever closer to her wilful master. Perhaps that was the root of the change in atmosphere. He should have thought of that sooner. Gradually his collar began to feel uncomfortably constraining and he reached up to loosen it with two ngers. He caught a glimpse of his slicked blond hair in the rear-view mirror and for the rst time that he could remember he noticed that his forehead was no longer suavely dry. His heart rate had quickened.

The car let him o at the corner of Aberdeen Street and Kau U Fong, the small alley in which The Chairman was located, and he walked to the restaurant without hurrying in order to calm himself down before Fitch caught sight of him. The Chairman’s sta welcome was the same as usual. Buford’s superior was waiting at a di erent table on the rst oor and had already ordered a plate of crispy enoki mushrooms and a bottle of chilled mineral water. The dry sixty-year-old American did not drink and imposed this restriction on all his lunches. When Buford appeared he didn’t get up or extend a hand, but merely motioned with his head that the younger man was to sit down and tuck into the mineral water. Seated, Buford turned to the waiter and asked in Cantonese for a small pitcher of lemon juice.

‘What do you usually eat here?’ Fitch said coolly.

‘Poached urchins or the pigeon with Longjing tea.’

‘The one with chrysanthemum?’

‘Yes.’

Fitch ordered the pigeon immediately (without the urchins) and added a request for some Chinese buns. The two men then looked at each other. They were both wearing dark-grey suits, but Fitch’s was double-breasted and exuded a slightly di erent heft. A gold tie seemed to x his head in space with the monumentality of a statue.

‘How old are you, Buford?’

‘Thirty-seven.’

‘Fine age for a man. You have a girlfriend, don’t you?’

Buford nodded.

‘Works in nance. Mainlander?’

‘Yes.’

‘Any plans for her?’

Resentfully Buford mumbled something about marriage discussions.

‘Well, you know what they say, Buford.’

‘No, what do they say?’

‘Monogamy is staying with the person until breakfast the next morning.’

‘So that’s what they say.’

‘It has a kernel of truth, don’t you think? You should get married.’

‘You mean it would look better for the rm?’

‘Now that you mention it . . .’

But Buford could not foresee exactly where their conversation was going. He admitted that, all in all, settling down might not be such a bad idea. He had been with Lily for three years. It had already occurred to him that she might be the right one.

‘Of course,’ Fitch went on as the Chinese buns arrived, ‘it’s not the ideal moment to make such a signi cant move. I suppose you heard the news about Evergrand this morning.’

‘I saw it just now in the FT .’

‘The markets are having a conniption t. But as I’m sure you are aware, this is long-term. It’s been going on for months. We’re all going to lose a lot of money.’

‘Ah.’

‘Not only that, but the Chinese authorities are changing their attitude. We’re getting demands to show up for audits. They are taking a rather di erent sort of interest in our operations. You see, Buford, we are going to have to let some people go. It’s not only for nancial reasons, either. I know

this will come as rather unwelcome news for you. You know how I feel about it, so let’s not waste time with sentimental expressions. It is what it is. The rm simply has to cut back its more ostentatious appearances. The rents we are paying for sta are getting quite incredible. I’m sure you already know what I am talking about.’

‘You’re ring me?’

‘That’s a very 1950s word, Buford. I assume you have some savings, don’t you? It would be preposterous if you didn’t, given the bonuses you’ve enjoyed these last three years.’

Free rent, too, was the sour implication.

‘Savings?’ Buford could not quite comprehend the word since he had never employed it, even inside the privacy of his own mind.

‘Leftovers,’ Fitch said, xing the pale eye upon him. ‘You know, the bits you didn’t spend on coke and girls and yachts. The bits, as George Best used to say, that you wasted.’

The dry laugh set the younger man on edge and he steeled himself to appear calmly nonchalant. Fitch went on to say that they would need to recuperate the town house by the end of the month. Forty thousand a month was too much to ‘throw away’ in the rm’s changed circumstances. That gave Buford three weeks to make alternative arrangements. It was enough, was it not? Of course they would pay a separation fee. He was not sure what it would be. Not that much, his dour expression betrayed.

Arriving just as Buford’s throat constricted, the teaavoured pigeon could not quite distract him from a quiet desperation.

‘Of course,’ he muttered, and wondered in a tragic moment whether this meant that his days at The Chairman were also over. He was silently calculating the relation between his remaining ‘leftover’ funds and the amounts needed to continue living on the Peak. There was, in fact, no relation.

Buford walked to the o ce alone, since Fitch had another appointment. On the twenty-third oor he greeted his downcast secretary, who helped him pack up a single box of belongings. She was not slow to say how sorry she was. Whispering, even though the o ce was half-empty as the crisis washed over it, she told him that several of his colleagues had been laid o as well. It was a bloodbath.

‘Yet no blood is actually spilled,’ he said with fatalism. The box was primly pathetic in its way; he had always kept a clean and spare desk. When it was packed he called Lily and asked her to meet later that day at a sake bar called Ronin, also on Kau U Fong. It was one of the most secretive bars in Hong Kong, tucked below a wall at the end of the culde-sac, and he wanted to be unseen. Then he went to his gym. He cancelled the following month’s membership and sat in the steam room for an hour, thinking and plotting, naked. He emerged restabilised.

Still in that morning’s business suit, he walked down to Kau U Fong in the heat, threading his way through the usual hectic crowds clambering up and down Sheung Wan’s steeply exhausting hillside streets. It was the hour of indecision between nature’s soothing dusk and the onset of the city’s

excessive electric illumination. Trapped in the suit, his skin broke into a fresh sweat. When he got to Ronin he found it empty, just opened, and the barman stood there alone in his long cavern, twisting a cloth inside freshly cleaned glasses. They were familiar with each other and they shook hands.

Buford ordered a carafe of Junmai sake on ice and gulped down two glasses to steady himself. He was an hour ahead of time. Early in the summer evenings the clientele was entirely single businessmen dressed exactly like him, a lost tribe assuaging their anxieties at a silent bar. But at the same time it was his and Lily’s place. They had been coming there since their rst date. When she arrived at seven, Buford was still drinking alone and they had the place to themselves. Since she had no inkling of his bad news he let her down a glass rst and then related the day’s mournful events, including the largely uneaten pigeon with Longjing tea at The Chairman.

‘They can’t do that,’ she blurted out at once.

‘Can’t?’

‘You can sue them.’

‘In fact, no, I can’t.’

‘What about separation money?’

‘To be discussed. I have a feeling they won’t pay it anyway. We’re in a new world now. The old rules have vanished.’

In the awkward pause he lifted his glass and proposed a sarcastic toast. ‘To the future!’

‘What about the house?’ she said almost at once.

He shrugged, reaching out for her forearm laid across the bar, the Codis Maya bracelet he had recently bought for her. He fondled the metal for a moment, then the cold skin around

it. He could tell she was thinking her own thoughts and that they were racing ahead in time even faster than his own. He said, ‘I’ll have to move out end of the month. Or come up with psychotic rent.’

‘You can move out. You don’t have to pay that kind of money. Just not on the Peak.’

‘It’s a shame that I’m so used to it.’

‘You can get unused to it. I can get unused to it.’

Can you? he thought, and yet there was a thread of sincerity in Lily’s voice and he let it go. The problem was his, not hers. It was he who would be unable to get used to not having that morning run among the Indian rubber trees and not having his pool table in view of the sea. The barman brought them a second bottle and a second ice-bed. They knocked glasses and for the rst time that day the idea occurred to Buford that maybe it wouldn’t be so bad after all. The rm was a collection of corrupt ghouls anyway – better to be out of it. Then, without much delicacy, Lily asked him outright how much money he had saved up. He lied; $28,000 was far from what he actually had, which was in reality closer to $10,000. Not to mention the credit cards.

She said, ‘I shouldn’t really ask you, but maybe I can help. It’s none of my business. But it’s better this way, because now I can help out more. It’s better to know where we stand.’

‘Help?’

‘I know a lot of people here, in case you didn’t know. I’m going to ask around for you. You’re young, you’re talented. You’re good-looking, you conceited asshole. I can help out.’

He took her hand and kissed it.

‘It’s sweet of you. But I doubt it.’

‘You’re not even Chinese. You don’t know anything about anything here. It’s me who can help you, not the other way round. And you’ve been sweet to me. I haven’t forgotten anything.’

When he had met her at a nance party three years earlier, Lily had been a classic small-town rube from a place fty miles back of Shenzhen. Heyuan, he thought the place was. He had traced it on a map. Her father was a mechanic slowly dying of lung cancer. He never asked her much about it, or them, sensing that she did not want to be asked, although she did occasionally bring up the matter of their needing a new house. Instead, they forgot about their respective pasts in order to enter the slow-moving tornado of an a air that swept them through darkened club dance oors and back rooms lled with cocaine tables, through weekend yacht trips to Lamma Island and then other weekends in Tokyo. Here and there, he had splashed out on her. But she liked Rado watches, not Jaegers, her tastes were quiet and unostentatious; she had never drained him of large amounts, for any reason. In fact she had never asked for anything. Patiently, insistently, she had won Buford over in the most important place of all, his unconscious. In that still centre of his being, she had found a secure place that could endure through a crisis.

‘What friends are you talking about?’ he said. ‘Just friends. People who can help you out.’

They went for dinner at the Java Road markets, then passed the hours in a club they liked, dancing together as if alone, his afternoon’s shock and depression gradually ebbing away to be replaced by de ance and lust. It was past one

when they climbed back up to the Peak in a public taxi. Since the night was warm they slept outside on the balcony, with mosquito burners, and nished a bottle of rosé. Now he remembered that for the rst time since he was at college at UCLA he didn’t have to get up in the morning. It was a small upside to his predicament. In the event, however, they woke up at dawn and Buford saw that no messages had ashed up on his phone. It meant that the rm had not yet made any public announcement. He made Lily scrambled eggs and they ate together as the moon disappeared and the cruise ships turned o their lights in the harbour.

‘You already look more relaxed,’ she said. ‘Maybe this was not a bad thing. It’s a shame to give up this balcony, though.’

It’s not real, he wanted to say. No mortal could a ord to live in such a place. But he murmured, ‘I can still nd a bedsit with a view. Every dump in Hong Kong has a view.’

‘You’re not going to live in a dump.’

After Lily had left for work, he put on his jogging gear and headed out to the jungle paths as per his usual routine. He had already decided that he might as well bene t from the vanishing perks of his now-past life.

He took one of the colonial-era pathways, with their old British railings, and ran in solitude under the rubber trees and tropical vines until he reached one of the viewpoints where runners always rested for a few minutes to take in the view. That morning there was no one about, not even the lean bankers taking their morning constitutional. He stopped, unusually exhausted – it had been a long night of ‘entertainments’ – and let his weight lean into the railing to relieve his

joints. His lungs sucked in air and he panted heavily, the sweat pouring o his face. Runner at college, now broken down by too many long nights and stressed by a lifestyle that no longer accorded with his advancing age. For the rst time since the preceding apocalyptic day he felt disgust rising within himself. The city, as everyone now realised, was changing hands as the Communist Party asserted its control, and the future of American expat nance operators such as himself was none too bright. Once he lost his perch on the Peak he would be unlikely to recover it. The house he occupied was likely being coveted by some Party bigwig he had never heard of and his ejection from it had been carefully planned in advance. There was little he could do but acquiesce. The power structure was turning over, throwing all the little men into the void.

As he stood there, getting back his breath, he gradually became aware that the bench behind him was occupied. A middle-aged Chinese man in a blue-and-white tracksuit sat there reading the morning paper, with a plastic cup of takeaway co ee. The man was partially bald, his grey hair undyed and groomed, and his sneakers were of the expensive variety. Probably one of the bankers out for his morning run, like him. Buford half-turned and o ered a Cantonese ‘Good morning’. The man lowered the paper and replied in kind. He was wearing gold-wire reading glasses, his eyes merry and inquisitive. In English he told Buford that he had seen him out running early the morning before. Buford told him which house he lived in.

‘Ah, I know it. Do you own it?’

‘Rented.’

‘Company rent then. I just come up here for the run. Can’t a ord even the rents.’

They chuckled. Buford turned from the railing and came to the bench. Some part of him felt a need for a conversation with someone who was a stranger. It would be a renewed contact with down-to-earth reality, with the healing power of the ordinary.

‘I’ve never seen you up here before,’ he said to the stranger.

‘Melvin Hui,’ the man replied, extending a dry hand.

Names exchanged, Buford decided he might as well sit down. Hui put down his paper and took o his reading glasses.

‘I avoid the crowds, you know. That’s why you’ve never seen me. I’m a ghost.’

‘Of course.’

It was a pun, since the common Chinese word for a foreigner was gwailo, roughly translatable as ‘ghost’.

‘The ghost of the Peak,’ Hui went on. ‘Me, not you. I was going to walk to the playground around the corner. Would you like to walk with me?’

‘I was going that way anyway.’

‘Hopefully the nannies and kids haven’t arrived yet.’

They set o at a leisurely pace and as they rounded the rst bend of the mountaintop pathway Mr Hui said that he had something to admit. He did not know Buford, obviously, and Buford did not know him, but it had not been entirely by accident that he had been on the pathway at the same time as Buford and at the same spot. Hui began to smile to himself, indicating that it was something completely innocent.

‘The fact is,’ he said, ‘I know your girlfriend, Miss Lily. She told me all about you. I hope you are not too surprised.’

‘More than that.’

For a moment Buford stopped, shook his head and laughed.

‘Wait a minute . . .’

‘It’s all quite ordinary really. She told me last night about your circumstances.’

‘Last night?’

‘She called me right away.’

‘She told you about my circumstances?’

The smile from Hui was, in its way, visibly blameless.

‘You must be a bit startled. Don’t be. I’ve known Lily for years. If you must know, she has been worried about you getting red for months. She has been thinking far ahead – more than you, it would seem.’

‘How do you know Lily, again?’

‘We used to be colleagues at China Construction Bank, years ago. Then I left to start my own company. Then I retired. But we stayed in touch. She helps me here and there with business things. We’re both from Shenzhen, you see. I look on her as my adopted daughter.’

‘But she’s never mentioned you.’

‘I asked her not to mention me to anyone. I prefer to keep it that way. But when she needs a favour, I am here. By the way, she didn’t ask me to come here and meet you. She knows nothing about it. You’ll have to promise me not to mention it to her, either.’

‘Why would I do that?’

‘Because if we keep it between us, Rowan, I am sure I can

help you. I might be able to help you get a new job. Though it might not be in Hong Kong. Of course I don’t know if you’d be agreeable to that, but maybe we can discuss it at some point.’

Reaching the playground park, they found it empty and sat at one of the stone tables under the trees. Buford expected the visitor to now present him with a business card, but he did not. Yet there was something genially furtive about him, an impression of some kind of underhand e cacy. Hui went on. He had been looking for someone like Buford for quite some time and so he had taken it upon himself to ‘leap into the breach’ and seize the opportunity as soon as he could – and before Buford received a more attractive o er from another quarter. It was fortuitous for him, at the very least.

‘What do you mean, someone like me?’ Buford said. But he felt subtly attered and relieved in the same moment. The very day after the catastrophe a potential opportunity had materialised.

‘Why don’t we discuss it over dinner tonight?’ Hui o ered.

‘I don’t know. It’s a bit of whirlwind. What kind of job are you talking about?’

‘It would involve you going back to the States. You might not want to go back, but I could make it comfortable for you. You could return here afterwards and I suppose, if you liked, you could resume renting the house you are in now.’

‘Oh?’

‘We – my company and I – have deeper pockets than Mr Fitch, if that’s what you are wondering. Much deeper. I was

being ironic earlier about not being able to a ord the rents up here.’

Then, mutually, they both seemed to relax, and Buford looked over at a mob of jackdaws hopping from table to table, cocking their heads. One appeared to stare back at him malevolently. He shook his head as if in disbelief, then he thought, Fuck it and accepted the dinner invitation. Betrayed by his treacherous company, to which he had contributed so much, he no longer felt inclined to be mistrustful of a stranger, since the latter could no more harm him than the men whom he had, until yesterday, considered to be his allies. If they were all the same – strangers and allies alike – why not toss in your lot with a stranger? Relatively speaking, what were benevolence and malevolence when they both o ered the same pay cheque?

‘I’m very happy to hear it,’ Hui said when Buford accepted his o er. ‘Shall we go to Tin Lung Heen and pretend we are adults?’

‘I’ve heard it’s quite empty now.’

‘Yes. That had occurred to me.’

Hui then stood up and said that he had best be on his way. They shook hands, Buford curious and bemused, and parted ways as the jackdaws scattered around them.

Buford retraced his steps to the house and spent the afternoon answering emails from colleagues and associates – the word of his ring having now got out. He decided to be ippant and o hand, as if it didn’t matter to him. One gets red, one gets re-hired. The nervous tone of his correspondents suggested that they knew otherwise, but he kept up an impeccable façade. He called Lily and told her he would be busy

that night; he left it as a message on her answering service. Then he waited for dusk, playing pool by himself in his grandly austere living room, with Deep Purple on his antique jukebox. At seven, dressed in a dark pinstripe suit, he called a cab for the ride down to Kowloon and the Ritz-Carlton. He intended to be slightly and unfashionably early, and he was.

On the lift ride up to the restaurant on the 102nd oor Buford re ected that for the rst time in his life he was skating over ice of indeterminate thickness. And he no longer cared. He made a con dent entrance into the discreetly elegant restaurant and found, to his consternation, that Hui was already there, reading the same South China Morning Post that he had been reading earlier in the day, but now dressed in a suit almost identical to his own. Fitch the previous day, now this. At least Buford wasn’t picking up the tab for either. Hui looked up calmly and welcomed him courteously. Tea for two had already been served in gold cups, abalone was on the way. Did Buford want a shot of Kaoliang baiju ?

The American thought it would be a good idea. His stress needed a little unpacking.

Hui raised a hand and the alcohol was arranged. When the shot glasses and bottle arrived, he o ered a toast: ‘To semi-strangers!’

They knocked back the rst shot and the bitter liquor went to Buford’s head at once. The tensions of the previous twenty-four hours seemed to burst into his frontal lobes for a moment, then vanish as if for ever. Hui, relaxed and unshakable, put Buford at his ease by describing some of his

background. He had grown up in Guangzhou and migrated to Hong Kong just after college. He had laboured in the storage facilities of a huge meat importer, then gradually worked his way into the real-estate business. He had worked in banks subsequently, had acquired a fortune doing business on the mainland, working as a go-between for government higherups. Buford knew the script. It was a familiar story. Hui had learned English in night school. Now he wanted to expand his real-estate business into the American market. Buford knew perfectly well why. The Chinese wanted to get their money out of a closed capital account like China, whose property market was going through an astonishing crisis, and get it into properties in rule-of-law countries like Canada and the US . Hui had been thinking about it for some time.

He had several contacts in California, which was where he wanted to invest, but he really needed a California native who also knew China. His idea was to send the candidate to California for six months and set him up in an attractive house with a considerable wage. From this base he could survey the landscape of opportunity, as it were, and set out to make advantageous contacts with in uential Americans in that sector.

Hui himself was unsure how such things worked in America. In China you had to know politicians in order to wheel and deal in high-value property. Perhaps America was the same. He assumed it was. He could hardly go in there and do it himself. Anti-Chinese sentiment was running high, was it not?

‘So I’ve heard,’ Buford said.

‘Well, that is my idea. It’s a rather simple one, on the face

of it. Do you think you might be interested in doing it? All I ask is six months and after that you’ll have no obligations to me. All I need are contacts, ways in, people who might help me on a basis of mutual pro t.’

‘And what kind of property are you interested in buying?’

Hui leaned back and his eye seemed to track the illuminated tourist junks oating by below. Their red sails stood out against the violent re ections in the dark water.

‘It could be anything. Nothing sensitive. Ranch land, mansions, farms maybe. I’ve heard the lettuce farms in the Imperial Valley turn a nice pro t. Or the land around Rancho Santa Fe. Do you know it?’

‘Of course. Hard to buy.’

‘Then you see what I mean. What about the area around the Russian River?’

‘In the north?’

‘My wife says she would love to own a house there. Maybe you could choose an area and then socialise with the local bigwigs. I’d give you enough money to make that possible – you could contribute to campaigns and such. Charities. American love giving to charities, do they not?’

‘It’s the nicest thing about us.’

‘There you are then. You could go in as a nice guy with deep pockets and impress people with your generosity and altruism. You’ve got the right kind of face. I think it would be surprisingly easy for you. You’re a native, and everyone loves a native.’

‘Do they?’

‘They do, in my experience. They especially like a native

who’s a donor. These are strange times. People will take money from wherever it comes. Like us, when it comes down to it. You know perfectly well you’re going to have to move out of that beautiful house in three weeks and you aren’t going to nd a place like the one you had with Fitch. They tossed you out in a heartbeat as soon as their bottom line was threatened. That’s the way it is. Look out for yourself, Rowan. Yourself.’

It was a perfect re ection of Buford’s own thoughts. He had been sold out, and so all his misgivings and inhibitions had been thrown out as well. Hui was right about the house and the job prospects. A lifeline had been thrown to him and he was beginning to think he had better seize it before he drowned.

‘What exactly do you want me to do?’ he said. ‘I don’t have to pretend to be someone I’m not, do I?’

‘Well, that does rather come with the territory!’

‘You mean I’ll have to change my name?’

‘If you don’t, your real history will be traceable in a minute. Think about it. It will be known, for example, that you were just red from a company in Hong Kong. That would ruin everything. You have to do a Gatsby.’

‘A Gatsby?’

‘Isn’t that the phrase you use? I read that book last summer. Very interesting look at American manners. I think the Chinese title might have been Capitalist Prince.’

Hui winked and, as if orchestrated, the abalone arrived. Only a single other table was now occupied, three young female socialites drinking bottle after bottle of champagne.

‘So,’ Buford ventured, ‘how do I do that exactly?’

‘It will all be done for you. You will enter the country under your own name and then we’ll set you up somewhere under a di erent name. No one is going to check your new identity with Immigration because they don’t have any reason to. And American bureaucracies are totally chaotic and hopeless, as I’m sure you know. Besides, you won’t be doing anything illegal. On the contrary. You’ll be an outstanding citizen contributing to charities.’

‘I suppose you already have a list of charities that you want to get friendly with?’

‘We are not entirely unprepared. I was thinking . . . I hope you don’t mind me saying what has been on my mind? There’s a lot of land I’d like to look at along the border. Most of it is the fty- rst congressional district. I believe the representative there is a man called Eugene Vargas. He’s in his seventies, but his wife Melania is much younger. We bought a property in a place down there called Bella Lago. I don’t suppose you know it?’

‘Not at all.’

‘It’s in Chula Vista, so part of the fty- rst district. But it’s out in the desert, the most expensive area in Chula Vista in fact. Some wealthy Chinese would love to live there. Buy the plots, build the dream house. You know what I mean. It’s the way my clients think. They want to be away from prying eyes. Our prying eyes is what I mean. They want to park their money o shore and have it be invisible.’

‘They want to be ghosts.’

‘Ha, exactly. Very well said. Exactly so.’

‘And I will be the ghost who prepares the way.’

‘You could put it like that. All you would have to do is a