Prologue

Courtroom 2B, Toronto, 1937

Mae betrays Lily for the second time in a courtroom. It is 20 October. It is the anniversary of Lily’s son’s death. A dull winter morning, the pale light seeping in through the high windows and gilding the spiralling dust motes so that, for a moment, the room is almost beautiful. Although this isn’t what Lily is thinking as she sits, her hands clasped in her lap, answering the lawyer’s final questions.

All around her, polished wood and winter furs; all around her, the smell of money ‒ tobacco, co ee, leather and cologne. It is the first time in weeks that Lily has been warm and she pulls her thin coat more closely around her shoulders.

Lily wonders how to answer the most recent question, only she can’t remember what it is. Her attention must have wandered, because the lawyer isn’t asking what they rehearsed. She was supposed to state only how many children she has, their names and ages. But the lawyer, the man employed by Mae to argue her case and Lily’s, is talking about morality and respectability.

Outside, there will be frost. Streets away, where the leaky-roofed houses are crammed together, the mud will

1

be loosening on the paths, and Lily’s children will be wrapping rags around their feet to keep out the cold while they stand in the bread line.

At the thought, her hands grip the plush velvet seat beneath her. She no longer tries to calculate how many meals she could make from selling even the cheapest chair in the courtroom.

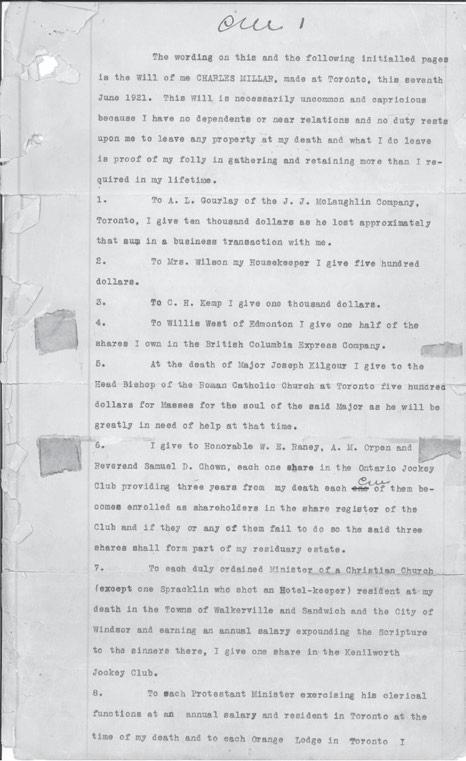

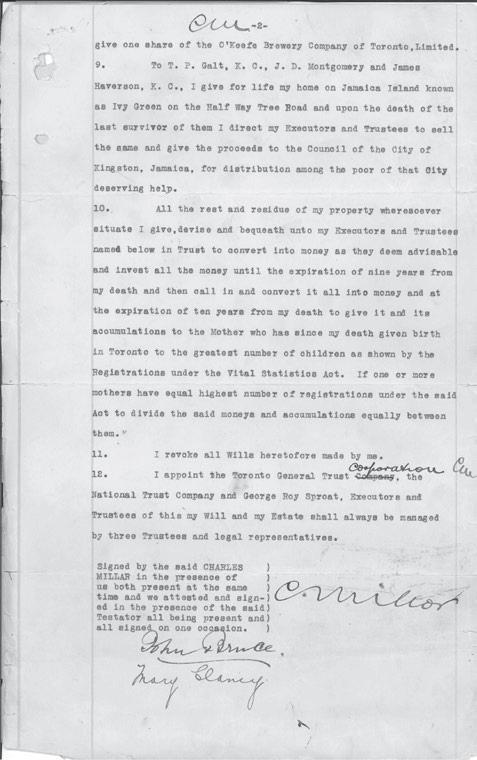

The lawyer has been speaking loudly and at length about the amount of money at stake: hundreds of thousands of dollars to the mother who has had the most children in ten years. But, the lawyer explains to the court, pu ng out his chest and pacing as he speaks ‒ very specific criteria have to be fulfilled. As if the people watching don’t already know, as if the Stork Derby hasn’t been in every newspaper in Toronto for months.

‘And,’ the lawyer says, ‘it is this court’s task to ensure that the successful mother is a deserving, morally upright member of the community. That her representation of herself and her family is honest.’

He talks on, his cheeks reddening as he warms to his theme. Lily’s thoughts begin to drift again, to the children back at home and what she can possibly give them to eat; to her breasts, aching and heavy with milk from missed feeds.

There is a pause, and Lily becomes aware of the number of eyes fixed upon her, of the sniggers from the gallery. ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t hear you,’ she says quickly, sitting up and trying to smile, to look appealing to the judge, to the people watching, to the reporters scribbling in their notebooks. Another titter from the gallery

2

and this time the lawyer smiles too, though he tries to hide the grin by stroking his moustache.

‘I’m sorry,’ she repeats more loudly, smoothing her thin cotton skirt. ‘Could you say that again?’

The lawyer’s smile widens. ‘Would you like me to word it di erently, so that you can understand?’

More snickering from the gallery.

‘Yes, please.’

‘I asked,’ the lawyer said, ‘what motivated you to come to Toronto? What made you leave Chatsworth and New Brunswick, your home? What made you leave your husband?’

Lily scans the courtroom to catch Mae’s eye, but Mae is staring at her own hands, her posture a mirror of Lily’s, knotting and unknotting her fingers. And Lily wonders why Mae won’t look at her, why she won’t meet her eye and somehow communicate the right answer. She wonders how the lawyer knows to ask her about Chatsworth when the only person who knows about that time is Mae.

High above, in the pallid sky, the sun disappears behind a cloud; the light in the courtroom dims. The golden dust motes vanish, as if something has snu ed them out.

part one

How can you frighten a man whose hunger is not only in his own cramped stomach, but in the wretched bellies of his children? You can’t scare him – he has known a fear beyond every other.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

Chatsworth, Canada, October 1926

The weather has been odd all autumn: bright, cold days giving way to an open, star-stamped sky and the sensation of frigid air dropping from frozen space. Along the northern border of the small town of Chatsworth, the black surface of the Miramichi river roils.

It’s hard to pinpoint the moment when something starts. Hard to identify the exact instant when the scales tip, when the hammer begins to fall, when the blade starts to swing downwards. But later, when she thinks about it, Lily will remember the unseasonal ice that rimed the shores of the river for weeks; she’ll recall the poor man whose thumb got jammed in the pulp-mill machinery when it froze; she’ll think of the animals that skulked in from the dense forest all around ‒ moose and foxes and even, it was rumoured, a bear ‒ creeping from the shelter of the trees to try to scrounge food from trash cans.

When she looks back on this time, Lily will see all of these things as warnings. Portents that everyone ignored.

But for now, Lily is in the cold kitchen plucking a chicken they cannot a ord. Her fingers are frozen and she jiggles her legs to keep warm, trying to wrap her

7 1

skirts around eight-year-old Matteo, playing silently with a train at her feet.

Tony isn’t yet back from the paper mill. He will have gone to a tavern, as he has done nearly every night since the mill began laying people o . It is often Tony’s friends who have been let go, and all the men are jumpy and angry, worried that they’ll be next. When Tony staggers in, smelling of whiskey and other women, Lily often pretends to be asleep. But he’ll poke her awake with his finger or his foot, and he’ll sit on the bed, his weight dipping the mattress so that her body is thrown towards him.

‘I don’t understand,’ he’ll say. ‘Business is booming everywhere, so why are they cutting men from jobs out here?’

‘I don’t know.’ And she doesn’t, because it’s true: everyone is making money. New taverns and shops are opening everywhere. Chatsworth sits on a large knuckle of land that juts out towards the Atlantic Ocean, as if pointing back towards Europe, where so many of its inhabitants and their ancestors first lived. In the summers, when the population doubles, tourists go boating in the river, or take picnics into the forest, their faces flushed from drink as they call jokes to each other in their hard city accents and laugh, slurring.

Years ago, Tony used to take her on picnics in those dark pines. He’d lain next to her on a blanket and pointed at the towering trees. ‘See, look at these. These are money. Just growing out of this soil.’ And he’d dug his fingers into the earth and scattered soil along her arm, both of them laughing as she squirmed away from him.

8

His eyes were shadowed, his expression earnest as he’d told her, ‘Everyone wants wood for boats and paper and buildings. I’m going to have my own factory one day. I’ll make us rich. I’ll look after our children.’

‘Children?’ She’d laughed. She wasn’t yet twenty and had known him less than a month.

He’d raised his eyebrows and kissed her, saying yes against her lips, telling her that he wanted children with her dark hair and big eyes, telling her that they would have strong, brave boys and beautiful, gentle girls.

She’d loved this certainty about him. The cockiness, the almost-arrogance that helped him to ask for a raise at the factory, that kept him hopeful even after the miscarriages, even when the demand for wood went down and the factory first began laying men o . But seven years of disappointment have worked hard lines into Tony’s face and a tension around his mouth, especially when he drinks.

‘There’s no chance for us here,’ he often grumbles, when he gets in from the taverns. ‘No hope for dumb dagos like us.’

Lily flinches from the word dago, although she works hard not to show it. She keeps walking if she hears it whispered in the streets, and if people push in front of her at the bakery or the general store, then she knows enough to keep her smile fixed, to wait her turn, not to push back.

But it’s harder to ignore the world outside when Tony brings it into their home.

‘I think they’ve got it in for us,’ Tony will say. ‘The

9

government doesn’t care about the men who work in the factories and the paper mills. We don’t matter.’

‘Of course you matter,’ she’ll murmur, pretending to be half asleep, when every nerve in her body is alert, conscious of the tone of his voice, the twitching muscle in his jaw, the tightening of his hand on hers.

His breath will be sour with whiskey or rum. Since Prohibition, the taverns are only allowed to sell weak beer, or wine with a meal, but there’s always a barman willing to fortify the ale with moonshine, for a price.

She mustn’t ever appear to be frightened, or he will be angry. She mustn’t contradict him too strongly, or he’ll lose his temper and there will be no more sleep for anyone that night.

Afterwards, he will be ashamed. He will hold her and kiss her; he will whisper tenderly into her hair. Sometimes he will weep, and look at her with such bewilderment that she will remember the man she married all over again. The man who never raised his voice or fist, who never sneered about himself, about her, as if he was cursing both of them.

She goes to the Catholic church on Brunswick Street every Sunday, but she is beginning to suspect that God heeds other people first, in the same way that Mrs Griffin in the post o ce serves Canadians first ‒ the people whose families sailed across from England hundreds of years ago. Then she serves Irish immigrants, then the very few Italians. And Lily assumes God has the same pecking order: why else would the older families have

10

prayers answered so readily, with their big houses and their fancy cars and their healthy children?

Lily was two when her parents brought her across from the north of Italy, just after the turn of the century. She couldn’t remember Italy, except, perhaps, a warmth in the sky and the richness of sunlight on orange stone walls, although maybe these things are memories that her parents gave her, stories about the homeland they missed. She had a slight accent still, mostly from her parents; it has grown stronger since her marriage to Tony. Tony, who grew up just outside Pisa and had been fiercely proud of this when she first met him.

‘How can you call yourself an Italian,’ he’d demanded, ‘when you’ve never tasted a real tomato? These watery things do not count.’

‘I don’t call myself an Italian,’ she’d said. ‘I call myself Liliana.’

Earlier, after Mrs Gri n had talked about the redundancies in the paper mill ‒ after she’d spoken of the rumours that the owners were cutting down on workers, moving more of their business to the bigger cities to the west, Ottawa, Montréal and Toronto, and transporting the trees there by rail, Lily had known: Even if Tony keeps his job today, it won’t be for long. And then how would they a ord the food on their table, the roof over their heads?

Their house is one in a long line, each sharing walls and noises ‒ she knows her neighbours’ sleep patterns; she hears their bickering and their reconciliations. This evening all the curtains are drawn, even though it is not yet ‒ not

11

quite ‒ dark. Further into town there are enormous mansions alive with candlelight, but her neighbourhood is made of cramped buildings, with bad drainage and shared walls. Damp, and crumbling.

Lily sighs. Across the street, she catches glimmers of light behind an identical row of thinly curtained windows, shadows moving and laughter. In her imagination, her neighbours are nearly always dancing or laughing, or making love.

She pulls out the last of the feathers and puts the chicken into the pot with water. Roasted tastes better, but boiled with carrots and onions will last longer: she will be able to skim some of the fat from the broth and spread it on crackers for Matteo.

Matteo never complains that he is hungry. He rarely speaks at all, her only boy; his face crumples and she can see him rubbing his stomach, but he doesn’t cry or moan. Her child has learned to make himself small and quiet and watchful.

‘Why doesn’t he talk ?’ Tony frequently demands.

But Tony’s clenched fist creates its own language. It makes its own silences.

Matteo used to chatter all the time, when he was little. Then he talked only when Tony wasn’t nearby. She last heard his voice a year ago.

With the chicken on the stove Lily has time – just – to take Matteo down to the river before Tony returns. Matteo loves it there. She kisses his soft cheek. And as she does so, there is a jolt, almost as if the earth beneath her feet has jumped. She blinks, stares at him.

12

‘Did you feel that?’ she asks.

He nods, his gaze wide and watchful behind the dark hair that is always messy, that always flops over his eyes. She leaves it longer than she should because he likes to hide behind it.

‘Come on,’ she says brightly, shrugging away a sudden unease. ‘We’ve still time to get to the water.’

Matteo smiles up at her. In his hand, he clutches the white, papery bark he strips from the silver birch trees. He loves to curl it around itself, using other sticks and pieces of wood to make masts and sails. Then he pushes his little boats out and watches them bob on the water, before they’re lost further downriver, as the banks widen and the river becomes tidal, the water cloudy with salt.

Lily has told Matteo that, if he builds a strong enough boat, it will sail downstream, out into the sea and be taken east.

‘All the way to Europe,’ she says. ‘Perhaps even to Italy.’

Lily feels her body relax and her lungs expand as they reach the bank. Matteo holds his boats tightly and she clutches his arm as he lowers the first curved piece of bark onto the river. He doesn’t push it out far enough, and a rippling wave brings it straight back. Matteo grins, grabs the boat, and leans as far out as he can, so far that Lily can feel her hands straining to keep hold of him. ‘Careful!’ she calls. But he gives the boats an almighty shove, all at once, and the fragile craft skate out onto the water, one, two, three, four. And all of them are caught up in the current, carried towards the open sea.

Matteo gives a cry of excitement, and Lily, thrilled by

13

his shout of happiness, picks him up and presses a kiss into the soft skin at the base of his neck, so that he squirms away, giggling.

She laughs too.

And then she feels it: another jolt. As if something has knocked into the ground below her feet.

Matteo’s eyes widen.

‘What was that?’ Lily asks, thinking, absurdly, of the stories in these parts about a salmon that is rumoured to swim in the waters, large enough, it is said, to swallow a child whole. The sky is darker now, the stars disappearing behind a rolling cloudbank and Lily is suddenly aware of how alone they are, that no one knows they are here.

‘We should go.’ She tries to keep her voice steady, not wanting to panic Matteo, but he isn’t looking at her any more. His gaze has slipped past her, out onto the black water, where his tiny boats are travelling upstream. Back towards them, as if pushed by some invisible, impossible hand.

‘I don’t . . .’ Lily says, but the words die in her mouth, as a sudden swell of water rises over the bank, a wave soaking her boots, then receding before rising again.

She pulls Matteo to her, as she used to when he was much younger, ignoring the strain in her back, ignoring his struggle to be put down, ignoring his desire to run and fetch his boats.

As she turns back to the town, Lily notices that the stars have been obscured by thick swathes of cloud. Clouds tinged with orange, as if, somewhere, something is burning. She stands very still, listening. The night birds

14

have fallen silent and, out of the stillness, a deer runs past, its hoofs clattering on the rocks. It stumbles but doesn’t stop, and Lily can feel the panic emanating from the creature, can feel fear rising through her own body ‒ some age-old animal instinct that something is wrong. Something has begun.

Lily grips Matteo’s hand tightly as she hurries away from the river, pulling him along as they stumble back through the darkness, towards the lights of the town. Matteo slips and falls, but he doesn’t cry out as he hits the ground. Lily stops, panic sluicing through her. He is unhurt but his eyes are large and frightened. She kisses his forehead and attempts a smile; it feels like a fixed rictus. ‘It’s nothing,’ she says, her voice too high-pitched. ‘Let’s get back into the warmth.’

Something sweeps through the air, almost brushing their heads, and they both jump.

‘An owl,’ Lily says, her heart hammering. ‘Just an owl.’ But as its dark shape wings away towards the dense shadows of the forest, it gives a harsh cry, and Lily can’t help thinking that this, too, like the deer, like the sudden clouds, is a portent of something awful.

‘Come on,’ she gasps, and there is no keeping the fear from her voice now. That strange electricity in the air is building, the metallic tension that crackles just before a storm. Matteo must feel it too ‒ he keeps pace with her, his mouth set in a thin, resolute line. She sees, for a moment, her own expression mirrored. It is the look that drives Tony crazy, but Lily feels a fierce pride. Her son will have to be obstinate to survive.

16 2

They hurry past the town hall, which is silent, and the paper mill ‒ in darkness now. They avoid the direct route home, which would take them along the streets of bars and taverns, blaring lights and laughter, and turn instead to the road running past the Catholic hospital and the poorhouse.

Relief washes over her when she sees her little house, still cloistered in darkness. Tony is not yet home. She feels normality slipping back into itself, like a warm hand into a glove. Drawing a deep breath, she pushes Matteo inside, shutting the door behind them and leaning her forehead against the wood, listening to the thrum of her blood.

‘Where have you been?’

Tony is sitting in the darkness, waiting. Her stomach drops. Instinctively, she shoves Matteo behind her.

Tony stays in the chair, his face half lit by the sliver of moonlight stretching through the window. His arm rests on the table, which, she notices, she’d forgotten to wipe down before she left the house. His gaze is intense, his dark eyes shadowed. He is holding a glass: the room is pungent with the sweet, peaty smell of whiskey.

‘You’re early.’ Her voice is bright and strained. ‘I meant to clean the table. I’m sorry. Are you hungry? There’s chicken in a pot on the ‒’

‘Where. Have. You. Been?’ He taps his fingers on the dusty surface, emphasizing every word. He’s always had strong hands. When they were first married, the rough rasp of his fingers against her breast used to make her shudder with desire.

17

‘Where?’ he whispers.

She tries to swallow, to think of something to say. She can’t mention Matteo’s boats, can’t draw attention to him. Tony doesn’t approve of Matteo playing, especially not if it draws Lily from the house. ‘I ‒ I wanted to walk down to the river.’

He stands, and she braces herself, but then he lurches and staggers slightly, before sitting back at the table, leaning his head on his hands. ‘I’m hungry.’ His voice is weary and, perhaps because of her relief, she feels a rush of tenderness.

She exhales. ‘Yes, sorry, of course. There’s chicken in the pot. And bread. Do you want that? Or I can fry some cornbread ‒’

‘Chicken.’

She fetches a bowl, giving him a generous chunk of the chicken, along with four slices of bread and butter ‒ the butter that was supposed to last the week, but never mind that now.

He eats hunching over, putting his arm protectively around the bowl.

She stands by the stove, watching him. Matteo hasn’t moved from the door.

He pauses, mid-mouthful. ‘You’re just going to watch me? Sit! Eat!’ He gestures with his spoon, flashing his teeth. There is something . . . o in his movements. His smile too wide, his voice too loud.

She doesn’t question him, fetching bowls for herself and Matteo. Like her, he will be too nervous to eat, the food like chalk in his mouth; like her, he will eat anyway,

18

forcing himself to swallow. As she stirs the chicken broth, she can feel Tony’s eyes on her face, moving over her body. She doesn’t know when she developed this ability, this extra sense that tells her when he is watching her, what mood he is in. When she was young, she’d seen a farmer showing o his dog’s obedience: it would run to him, would jump up and sit and roll over, all without the farmer saying a word. She’d thought they must be able to read each other’s thoughts, that man and dog. The best of friends! She’d longed for such an animal herself.

Later, she saw the farmer walking home, saw him aim a swift, sharp kick at the animal’s ribs; the dog jumped out of the way without the boot touching him, as if he’d sensed it coming.

Now, before Tony has laid down his spoon, she knows he will want more; she serves three brimming ladlefuls, more bread, the remaining butter. She wants to ask him what happened at the paper mill. She wants to know if he’d felt those strange skips in the land, if he’d noticed anything odd, if he’d felt, as she had, a sense of something dreadful approaching. But if she asks the wrong questions, she will make him angry. She spoons an extra piece of chicken into his bowl. When she places it in front of him, there is a moment when the corner of his mouth curls up. Again, she feels a relief which is almost a ection.

He hadn’t hit her after the first miscarriage. Or after the second. Or when Matteo was a sickly baby, howling all night. Or when he didn’t babble or make any noises

19

that might be speech. Tony didn’t hit her, but he’d stopped talking to her. Stopped looking at her or smiling at her. He made love to her with his eyes closed, his face turned away.

Then he’d been overlooked for a promotion at work: a young Canadian-born man had been given the managerial role, while Tony had been relegated to the factory floor again. Lily had felt outraged. ‘But why ? Why would they ignore you like that?’

His fist struck her across the face so quickly that she didn’t have time to duck. She staggered and fell to the floor, cupping her hand over her throbbing cheek.

Tony had crouched next to her. ‘Oh, God, Liliana! I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.’ He helped her up, held a cold glass against her cheek, wrapped his arms around her and rocked her back and forth while she heard words rumbling through his chest, like the growl of far-o thunder. He hadn’t meant to, he said, but she’d just made him so mad. It was the look on her face, you see. No man wants to be looked at like that by his wife. Like he’s a worm or something. It just made him angry, that was all.

‘Good woman,’ he says now. ‘This soup is good.’ And she feels a glow. And she knows that this will make whatever is coming even harder. Because something is coming – like the moment before a glass shatters. It has already been dropped; there will be no repairing it.

‘A whole chicken?’ he asks, looking towards the pan. His voice is still light but she can sense other questions beneath this one: How did we a ord this? Why are you being wasteful with my money?

20

‘Mr Murray let me have it cheaply,’ she lies. Murray has never sold anything for less than its full value, but Tony never goes into the butcher’s, so there’s no reason for him to disbelieve her. She stands; his eyes, gleaming, don’t shift from her face. She feels heat creep over her chest ‒ the tell-tale rise of blood.

At the end of the table, Matteo is chewing fast, his eyes fixed on his bowl.

As she leans across to clear Tony’s dish, he slides his hand around over her skirts, to cup one of her buttocks, then squeezes ‒ too hard. When she winces, he draws her in close to him, kisses her. She tastes ale and whiskey.

He pulls her into the little bedroom they share, barely bigger than the small bed. In the early days, Tony used to talk about the fine house he would buy one day. Now, he glares at the poky room as if the narrow walls are an accusation.

‘Matteo, clear up,’ he says, without looking away from Lily. ‘Quietly, mind. No banging those pots.’

And though Tony shuts the door as he pushes Lily onto the bed, she can’t help listening to the mu ed rattle of dishes in the bucket. Tony hitches up her skirt and pulls down his trousers, giving a groan that sounds torn between frustration and pain.

She bites the inside of her cheek, wraps her legs around him and pulls him close to try to speed things along.

As Tony thrusts, Lily counts how much money they have for the rest of the week.

Not. Enough.

21

The crack on the ceiling has grown. The walls are yellowing. The thin curtains are torn from when Matteo used to pull himself up on them.

At the last moment, Tony turns towards her and she thinks he is going to kiss her. He recoils, groans, shudders and collapses on top of her.

Afterwards, when Tony is asleep, his trousers still around his knees, Lily stands, wipes herself o and goes into the other room, where Matteo is lying on the mattress in the corner. He is pretending to sleep, his breathing light and shallow. As she rinses herself from the bucket, then empties the water outside the door, she sees him squint an eye open to examine her. He’ll be looking for bruises, a limp, blood.

‘Go to sleep,’ she scolds, knowing he will find comfort in her feigned irritation.

The tension eases from his body and he snaps his eyes shut.

He has always seemed ahead of his years: he walked at nine months and is a quick study at school – the other children tease him for being silent, wondering aloud if he can understand English at all, but the teachers praise his writing, his arithmetic. Lily taught him to read in the same way that she learned, from the scraps of newspapers and magazines stu ed into the window frames to keep out the draughts and used as paper for the outhouse, and she enjoys helping him to trace out letters in the dirt.

He must talk more, everyone says. But Lily sees the fear

22

in his eyes when he is forced to say anything: the shadow of his father eclipses every request.

Now she puts the bucket quietly on the floor. Then gently, so as not to pretend-wake him from his pretend sleep, she pulls the blanket over his shoulders, kisses the pale, tender skin of his temple, and returns to bed.

She wakes to a pallid pre-dawn light. Tony is staring at her.

Nothing in his face changes when he takes her wrist and squeezes it so the bones crackle. She sucks breath into her lungs, instantly alert, instantly frozen, as if her body is balanced on a precipice and any movement she makes will risk plummeting downwards.

‘How did you know?’ His voice is dangerously soft.

Her mind flickers back over the past evening, a trapped moth battering against glass – how did she know what ? The safest thing is to say nothing. The safest thing is to wait.

Will Matteo be awake yet?

‘You went to the butcher’s yesterday,’ Tony says. She swallows, nods.

‘You heard talk about men being laid o in the paper mill. You bought a chicken. You knew I’d lost my job but you bought a chicken.’

‘I didn’t know ‒’

His hand tightens around her wrist. Pain like a burst of stars.

‘Don’t lie to me. You heard them talking. John Barry said his wife saw you. But you bought that chicken.

23

Throwing money away, trying to butter me up. Treating me like a child.’

‘I wanted to make you feel better.’

‘With a chicken?’ He sounds amused, but she knows him too well to smile.

She looks again at the cracks in the walls, the yellowing paint, the torn curtains. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘For spending all my money? Or for taking my son out to avoid me.’

‘It wasn’t to avoid you.’

‘Stop lying! You knew. You knew I’d lost my job but you didn’t say anything. Why?’

‘I didn’t know ‒’

‘Liar! You were trying to distract me. Like I’m a fool. Is that what you think? You think I’m stupid?’

‘No!’

She can feel the pressure building around her wrist, the muscles in her arm burning as his grip tightens. And she realizes what he is doing. He has done this before: laid a trap for her. There is no way of her winning now, no way of avoiding this wave.

But there is a di erent tension too: the feeling she had yesterday, of something about to slip. She remembers the jerks she’d felt, as if the ground was jumping. The water in the river going the wrong way. The air tasting of iron. She must leave, somehow; she must get away.

Twisting her arm free, she turns and darts through the door, towards Matteo, who is sitting up on the mattress, his eyes huge and terrified, just as Tony reaches her, drags her back, and punches her in the face.

24

An explosion in her skull, a high-pitched whine in her ears. She crouches on the floor, then lurches to her feet, trying to reach Matteo.

As she takes a step, the first real tremor shifts the walls and ripples through the floor, making Lily stagger towards Tony. She reaches out to steady herself against him, as if she wants to embrace him, as if his clenched fist isn’t raised, as if her jaw isn’t throbbing from where he has just backhanded her.

She doesn’t immediately comprehend that the heaving of the floor and the shaking of the walls is an earthquake. At first, she thinks that her vision has changed, that Tony has jolted something loose in her brain, that rather than knocking some sense into her, as he’s always promised to, he’s slammed something out of her.

Tony’s eyes are wide, furious, ba ed, and, for a moment, that’s all Lily can see: the whites of her husband’s eyes with their fine spidering of veins. Those eyes, red-rimmed with last night’s drink, that tell her to stand still and be quiet, woman.

The shaking turns to rattling: pictures fall from the walls and, somewhere behind her, a glass shatters. On the mattress, Matteo cries out in alarm. She pushes Tony away, shoving his shoulders hard so that he staggers backwards, into the wall. Grabbing Matteo, she pulls on his arm, crouching as she drags him under the table.

He is crying silently; she curls her body around his, shielding him. Waiting for Tony’s hand on her shoulder. Waiting for him to yank her away from their son and raise his fist again. Beneath her, the floor heaves and

25

judders. She bites her tongue, tastes copper. There is an almighty crash as the shelves fall. Lily cries out, but the sound is lost in the grinding, groaning, scraping rattle of the world being shaken by its throat.

She squeezes her eyes shut, wraps her arms tighter around Matteo. How small he is. How fragile his bones. Something smashes near their heads; she covers his face with her hands.

Let it hit me, not him, she thinks. Whatever it is, let it hit me.

The shaking slows, the noise quietens, stops.

The stillness is so absolute, the silence so intense, that Lily thinks she has been crushed and killed. The roof has fallen in, she decides, or the walls have collapsed on top of her. She feels disconnected, floating. She thinks of the beliefs of the people who belong to this country, not the milk-skinned European immigrants, who think they own everything, but the native people, whom she rarely sees in the cities, and who are treated like dirt. They have a belief that when the body dies the spirit rises and travels westward, over the grassy prairies where it crosses a river and ascends a mountain into the spirit world. Perhaps the floating sensation she feels is part of that.

Then Matteo shifts in her arms and utters a tiny moan, and ‒ Oh, God, he’s alive! Somehow, miraculously, they are both still breathing, still able to move. She kisses his cheek, her lips leaving a bright bloodstain on his skin.

‘Are you hurt?’ she whispers. Her words sound loud in this newly silent world.

Speak to me, she thinks. He shakes his head.

26

Idiota, Tony often calls him, grabbing him roughly by the shoulders, the collar, the ear, while Matteo stares at him in silence.

Tony!

Lily peers through the dust, across the room, to where she’d last seen her husband, to where she’d pushed him ‒ hard. She can still feel the weight of him against her hands, can still picture the shock in his eyes as he’d stumbled into the wall.

He isn’t there. Tony has gone. Disappeared.

The air is acrid, and thick with a swirling powder that fills her mouth and lungs. Lily coughs, wipes a sleeve across her eyes, then looks again. There is a pile of rubble on the floor and, somehow ‒ Lily blinks ‒ somehow, she can see through the wall to the trees outside, which slant at drunken angles. Slowly, she understands that the wall has collapsed, and that the pile of bricks on the floor is all that remains.

It takes her longer to see Tony.

He is lying underneath the rubble, his hands splayed, as if he is reaching for something, or searching for help, or trying to escape. His skin looks oddly white, like the rest of the room. Lily rubs her eyes again, blinks. Gritty: the dust is settling over everything, draining it of colour.

She turns Matteo so he cannot see his father.

‘Stay here.’ She is surprised by the steadiness of her voice.

Everything inside her is shaking: blood, bones, heart. Every nerve quivering. The earthquake is within her now.

27

Slowly, she inches forward. Limbs aching. Taste of rust. She reaches out towards the inert hand on the floor. On his knuckles, beneath the white dust, she can just make out the blood from where his fist had struck her. She touches her jaw experimentally, runs her fingers over the bruise, swollen like a ripening plum. Through the blur of shock, she feels no pain.

She touches his knuckles. Still warm. Again she feels nothing, just the stunned reverberations that echo through her bones.

His face is pressed against the floor, eyes shut, mouth open. As she leans forward, he gives a wheezing groan.

She jumps back, as if he had reached out to grab her. He wheezes again, then coughs, and she realizes that the emptiness she’d felt ‒ the hollow thud of nothingness when she’d looked at his broken body ‒ had been relief. And that what she feels now that he is alive is panic.

She turns to Matteo, who is staring, his eyes terrified and trusting. She checks him for signs of damage: head, limbs, stomach all intact. No blood anywhere. His gaze flicks to his father on the floor, and when Tony wheezes again, Lily sees Matteo flinch, sees her own fear reflected.

For a moment everything slows: her heart pauses, her mind compresses, and she is breathless, waiting for a spun coin to land. Then, as if she has asked a question, Matteo nods quickly, once.

The coin clatters and Lily’s heart thuds as she moves to the single, battered wooden chest. Quickly now, with a single purpose, she pulls out a bag, along with clothes and shoes, hers and Matteo’s, everything she can find.

28

She stu s the lot into the bag in a jumble of material, not knowing if she has enough of everything, only knowing that she must move.

Quickly, quickly, quickly. Her heart pounds out the rhythm, echoed by her rapid breath: Come on, come on, come on!

Matteo puts a hand on her arm; she pauses. He holds both hands out. In one small palm is his wooden train, which he takes everywhere. In the other is a gold locket Lily’s mother had given her when she died, ten years ago now, from the flu. It’s her only jewellery, apart from her wedding ring.

‘Good boy.’ She kisses his forehead.

Matteo looks towards the rubble, where his father is still lying face down. Tony hasn’t moved, but his groans have become louder and Matteo’s expression is urgent. The doorway is blocked by fallen bricks and plaster: they will have to leave through the hole in the wall, clambering across the rubble and over Tony’s body.

Fear tastes sour ‒ or perhaps it is her blood still. Hard to tell.

They must leave now, before Tony moves, before another quake ripples through the little house, bringing more bricks down around their heads. She remembers Tony telling her about the earthquakes north of Pisa. Sometimes the aftershocks would go on for days.

Lifting Matteo over his father’s body, she clambers over the rubble. As she steps past Tony, he stirs, hand twitching.

‘Please. ’

29

Tony’s eyes are open. He is staring right at her. He used to say that he would take her back to Italy one day. They would walk around the town of Moena in the north; they would find his aunts and uncles near Pisa. They would sit on the banks of the River Arno drinking red wine.

She draws a shaky breath, tries to speak.

‘Please,’ he hisses.

The anger in his eyes ‒ she recognizes the fury building there. If she releases him, if she scrabbles, bloody-fingered, through the rubble and lifts him from the wreckage, he will hit her. Again, and again. He will hit Matteo. Everything will be as it always has been, only worse, because now he will know how much she hates him.

Hanging from the wall behind him is a solid piece of wood, one of the beams that forms part of the structure of the house. It is leaning over Tony’s body. The only thing preventing it from falling is a twist of wire. Her brain trips and slips on the fact of the wire, on the position of the beam, on the bulk of Tony, half trapped under bricks, but struggling to free himself.

He is still staring at her. Matteo, too, is gazing at her.

‘Look and see if the street is clear,’ she says to Matteo.

As soon as he turns away, she reaches out, tugs. For a moment the wire catches on the end of the beam, and she has to pull hard, has to strain, the wire cutting into her flesh.

It jolts loose and Lily steps backwards.

The beam drops, cracking against Tony’s skull. His

30

body goes instantly slack, face inert, eyes closed. She can’t see if he is breathing. And part of her wants to lift the beam o , to dig him out, to take him to the hospital because, dear God, what have I done?

But the other part of her, the part of her that is a mother, turns to Matteo, who is momentarily frozen, his mouth slack with fear.

She puts her arms around him.

She steps over Tony, through the hole in the wall, into the street.

The street outside is pitted and rumpled – the cobbles like a badly made bed. Lily struggles to make sense of a world that looks both familiar and strange. There is the butcher’s window, on the corner, only the glass has gone, and next to the carcasses that still swing in the open air, a ripped pipe spews water onto the road. Many of the neighbouring houses have collapsed; those that remain half standing have gaping cracks in the walls and shattered windows. The road is covered with rubble, wood and glass, as though some beast has ripped through the town. Something crunches underneath Lily’s shoe. When she lifts her foot, she finds the shattered mirror from a lady’s dressing-table. She averts her gaze from her splintered reflection, unwilling to meet her own eyes. She thinks of Tony, lying under the wreckage.

How long will it take before he stops breathing?

She remembers his fingers stroking her neck.

She remembers his hands around her throat.

She kisses Matteo’s soft palm. He is crying soundlessly.

Other people are emerging from the surrounding houses, all of them pale, covered with the same white dust as she and Matteo. It is hard to tell who they are ‒ everyone looks dazed, as though walking through some dark dream.

32 3

Far o , in the centre of town, Lily can hear alarm bells and the chimes of churches ringing out a warning, although she doesn’t know if people are pulling on the ropes, or if the bells are simply swaying by themselves, as if whatever invisible hand has shaken the earth under their feet has also set the bells ringing.

In the distance, incongruously, she hears the howl of wolves.

I must be going mad. Wolf packs never come this close to the town.

Then she remembers the tiny zoo, which has become bigger and more popular over recent years, as more people from surrounding towns have visited Chatsworth to boat on the river, play golf and see wild creatures in cages. Lily wonders if the animals are loose. She imagines them prowling through the ruins of the hotels and taverns. She pictures them scavenging through the wreckage.

‘Come on,’ she says to Matteo, her voice falsely cheerful. Her son is staring at everything, his face slack with shock. He has never been a boy to venture out alone, preferring to stay near to her and only go the short distance to the grocer’s or butcher’s ‒ the sole trips Tony had permitted. The only place Matteo truly wanted to go was the river, but if she went, Tony would glare and growl that she shouldn’t be taking risks. He wanted to keep her safe, he said, because his own mother had been badly beaten in the street when his family first came to Canada.

Is it possible for anger to be passed from mother to child?

33

She hears a cry of ‘Liliana ! ’ and she turns, sure it is Tony’s voice, calling the name she used to have before he insisted that they become Lily and Tony, to blend in. It had made no di erence.

It is not Tony calling, but a turkey vulture circling overhead, in search of meat.

‘Quickly now!’ Lily’s voice is tight as she pulls on Matteo’s arm and they begin to pick their way over the wreckage. There are more people on the streets now. Like ghosts emerging from a graveyard, they stir and stand upright. One woman is lifting bricks from an impossibly high mound of rubble and weeping, a highpitched, repetitive sound, like an alarm bell. Lily wishes she could block it out. A vivid splash of blood stains the woman’s neck and collar; Lily looks away, ignoring the twinge of guilt. She can’t help anyone else: she must get her son safely away. Away from the risk of more quakes. Away from the memories of Tony and his body, and the stories it could tell.

Where can she take Matteo? Where will he be safe? Nowhere in this town: Tony is too well-known from the paper mill and the bars. People will recognize her. They will ask where he is. They will discover that her husband is dead and that she is fleeing and oh, God, what will they do? She knows then, that they won’t be allowed to leave this ruined town: they will be made to stay in this place that pushes her to the back of lines, that never truly sees her, never wonders who she really is, what she really feels.

She smears brick dust across Matteo’s cheeks, over the plaster dust, so that he is striped in red and white.

34

‘You look like a monster.’ She smiles, keeping her voice light, trying to reach him somehow through the shock that has gripped him. Matteo’s teeth are chattering; his stare is fixed and glassy. She rubs the dust across her own face. ‘Now I’m a monster.’ She forces her grin wider.

His mouth creases. She pulls him close, cursing herself. He has enough to be afraid of, without imagining his mother as a beast. Although perhaps only a beast would leave her husband crushed beneath a wall.

How long until someone finds him? How long before they begin searching for her?

She thinks of the train tracks, the whole rail system that carries goods and people back and forth from here to the big cities to the west. She could live in Ottawa or Montréal, a thousand kilometres away. No one would know them there. No one would know what she had done.

She holds Matteo’s shoulders, staring intently at his face. ‘We’re getting a train. Just the two of us.’ She tests the weight of the coins in the pouch in her pocket. How much would two tickets cost? She closes her fist around it, hoping it is enough.

He opens his mouth and, for a moment, her heart lifts. He’s going to speak. She waits.

A wind gusts pieces of paper through the air around them. A man shu es past, a bloody gash across his cheek. Somewhere, in the distance, a woman screams.

Lily kisses her son’s cheek, and they begin to pick their way through brick and wood and glass.

35

At the crossroads in the centre of town, she stops amid the wreckage of broken wood and shattered bricks, the fractured shape of the monument for the men who died in the Great War. The statue of the man has cracked, so that only the legs and torso remain.

Pallid limbs stick out from under buildings. Lily tries not to look. As they pass what used to be the grocer’s, Lily has to step over an outflung arm. The fingers are curled inwards, as though their owner has tried to grasp something. Lily can hear a voice rasping, Help me.

She pauses mid-step.

Help me.

She is about to walk on, but Matteo tugs on her sleeve and stares at the mound of bricks, the smashed glass, the limp hand. The fingers twitch.

Matteo’s face is pinched and he refuses to move. She looks over her shoulder, imagining Tony emerging from the rubble, rising from the dead, limping towards her. There are many figures in the street, bloody, dazed, stumbling, but none looks like Tony.

Lily crouches. ‘Hello?’ she says.

On the fingers of the hand are two rings that she recognizes as belonging to the grocer’s wife, Marie. Stern-faced, red-haired and curt with customers, but she would always wink at Matteo. Once, she gave him a windfall apple that was too bruised to sell.

‘Hello?’ Lily calls, more quietly.

No reply, and those pale, ringed fingers lie unmoving. Lily stays very still, aware of the rise and fall of her chest, the whoosh of her blood in her ears, aware of her son’s

36