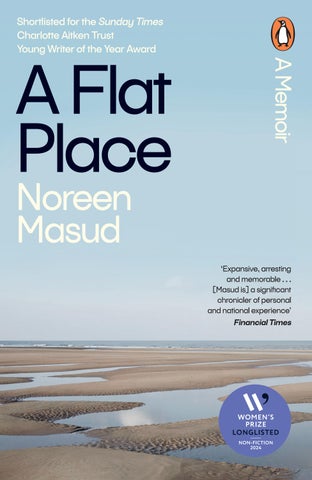

‘Expansive, arresting and memorable . . . [Masud is] a significant chronicler of personal and national experience’ Financial Times

‘It would be easy to assume that A Flat Place, dealing as it does in the currency of trauma, racism and exile, is a bleak book. But this memoir is too interested in what it means and how feels to be alive in a landscape to be anything other than arresting and memorable . . . In the flatlands of Britain, and in the memories they evoke of the flat places of Pakistan, Masud both finds a way to comprehend her own story and establishes a strong voice that confirms her as a significant chronicler of personal and national experience . . . A Flat Place is a slim volume, but that belies its expansive scope’ Financial Times

‘Nature writing can feel a bit samey. Wildlife, folklore, sustainability, emotional connection – all that stuff. Noreen Masud, a lecturer in literature at Bristol, offers a powerful antidote. She visits five distinctively flat British landscapes – Ely, Orford Ness, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor and Orkney. Interwoven into her travelogue is a memoir of her childhood in Pakistan under the thumb of a narcissistic and possibly abusive father, and how it has left her traumatized and numb. A journey into flatness might sound like a tough sell, but this is so worth it. The whole book is zingily fresh’ Sunday Times, ‘Best Books of 2023’

‘A domineering father [. . .] features in Noreen Masud’s lyrical, melancholy A Flat Place, in which the author travels to some of Britain’s starkest landscapes, including Morecambe Bay, Orford Ness and Orkney, while reflecting on themes of exile, heritage and her troubled childhood in Lahore, Pakistan’ Guardian, ‘Best Memoirs and Biographies of 2023’

‘Flat lands are overlooked, the bearers of our inattention. Moors, deserts, floodplains, fens alike have too often been effaced to the point of invisibility. In A Flat Place, Noreen Masud makes brilliantly good this lack; her book fathoms the depths of such landscapes, and their curious abilities to archive and erase, to unsettle and to console. In her prose, terrains of the spirit and the earth begin to slip over one another, like acetate sheets seeking a match. Sharply, subtly and very movingly, Masud thinks with places, seeking as she does to find a way back into, and then out of, the traumas of her early life’ Robert Macfarlane

‘Stark, careful, enlightening’ Guardian, ‘2023 Summer Reads’

‘Between vivid descriptions of their geographical features, Masud confronts her childhood memories, her relationships with others and the post-colonial histories of both of her homelands’ New Yorker

‘Vital . . . Social media can feel like peering into a monetized confessional booth . . . [Masud] offers readers a counterpoint to that atmosphere of abundant divulgence . . . Masud asks readers to listen as they wade into the muck with her, giving voice to lived experiences that might otherwise be considered unrelatable’ Washington Post

‘Noreen Masud’s A Flat Place is very much in the Robert Macfarlane tradition of writing about the natural world, and the idea of a book that forgoes peaks and depths is ambitious’ Scotsman

‘Striking . . . an excellent work of literature’ Chicago Review of Books

‘In this profound and moving book, Noreen Masud shows how what has been overlooked as flat and empty is alive with significance. The writing is not only achingly beautiful, it conveys in its own rhythm how small undulations give nuance and form. We learn how complex trauma gets everywhere, affects everything; who one is, how one is, with whom one is. Stories of violence and memory, colonialism and patriarchy, family and friendship, are interwoven with delicacy and care. A Flat Place teaches us how the struggle some of us have to be in the world can be how we craft different worlds. It reminds us that there is hope in the smallest of gestures’ Sara Ahmed

‘A startling memoir . . . It is a story of the feeling you get when the stories we tell ourselves refuse to disclose an essential or epiphanic message. A brave style of refusal that somehow still manages to convey a ringing affirmation’ Arts Desk

‘A beautifully written memoir that looks at how landscapes can help us understand ourselves . . terrifically precise and lyrical . . . this book might be called a nature memoir: each chapter engages intimately with the natural world, from the

Fenlands to the Orkney Islands, and even the stillest, flattest and quietest revelations are inextricably tied to the environment. But, equally, Masud pushes against determined traditions of nature writing. The expansive space of this memoir is an invitation to collapse boundaries and make room for experiences and bodies that are often erased from British history, and in doing so, Masud also voices the realities of this nation’s colonial violence’ Big Issue

‘Sorrowful, tender . . . beautiful’ The New York Times Book Review

‘Haunting and generous, beautifully written, revealing and refusing in the best ways – this book is a gift to all who have experienced complex trauma, all who seek the long view, all who crave solitude as we do community, all who see in flat landscapes the chance to reflect on the depths of the self as it heals’ Preti Taneja

‘Psychologically and politically riveting: Noreen Masud dares to poke the bones of the psyche with idiosyncratic brilliance, while she unwraps clingfilm-racism: airtight, watertight, hard to see and vital to name, that sly racism by which experience is exiled’ Jay Griffiths

‘An unusual and enthralling memoir . . . persistently insightful in the way she links landscape to her psychological state . . . the final pages are remarkable for their insights about how childhood, gender, ethnicity and the expectations of society leave their mark. Ultimately it’s a book of endurance and hope’ Daljit Nagra

‘Like the flat places she so values, Masud “refuses to perform beauty in predictable ways”. Mountains are “coercive” in their beauty – likewise a culture that expects survivors of trauma to pinpoint a rupture and overcome it. Noreen Masud invites us to think instead on places without desire – places that are forgiving because they are absorbed in being themselves. She uses them as a balm against a personal trauma that never had a climax, no event that could be scaled like a mountain face in the terrain of therapy. A Flat Place cuts new ground, mixing literary criticism, decolonial history and boldly anti-Romantic “nature” writing in searing prose as sad as it is funny, to confront the noninnocence of writing “nature” and place. This is an important and original interruption of the so-called “nature cure” ’ Abi Andrews

‘Noreen Masud conjures a sensibility that has eluded most – writers hoodwinked into supposing that what’s flat must be empty of significance. But to dwell upon flatness, as Masud does, is to find oneself reoriented. It is to ask who we are and where we are if we no longer take the bait of imagining our lives as a dig or a summit or a horizon’ Devorah Baum

‘A beautifully written, important memoir, exploring environmental experience alongside trauma, belonging, prejudice and the self. It’s a profound look at how landscapes can help us understand our inner worlds, and how our relationship with nature and place might make new ways of being possible’

Rebecca Tamás‘A moving, lyrical and frank reflection on place, space and the shifting contours of self. This is a new kind of migration narrative, one that finds stories in both stillness and movement, in flatness and undulation’ Priyamvada Gopal ‘Marvellous. A radical, affecting testimony to unbroken spaces, histories and notions of selves’ Eley

Williams‘In this compelling, compassionate account of the aftermath of complex trauma, Noreen Masud sets out across the flatlands that fascinate her, in search of “an imperceptible distress in the landscape that you can’t pin down”, reckoning with what it means to connect. Stark and beautiful as the terrain it describes, A Flat Place offers a psychogeography of such trauma, in which flat places become, paradoxically, sites of relief. The book is above all a tribute to (human and animal) friendship, and a testament to the power of forging strange relationships with strange things’ Emily

BerryNoreen Masud is a lecturer in twentieth-century literature at the University of Bristol, and an AHRC /BBC New Generation Thinker. A Flat Place, her first trade book, was longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction 2024.

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Hamish Hamilton 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Noreen Masud, 2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 0 2 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–99433–7

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

To say, as some do, that the self must be narrated, that only the narrated self can be intelligible and survive, is to say that we cannot survive with an unconscious.

(Judith Butler, Giving an Account of Oneself )Every morning in Lahore, as we drove to school, there came a point when I’d quieten and coil into myself. Jammed together with me in the back seat, my sisters went on quarrelling, poking one another with elbows, voices raised in jeers or protest. But I stared out of the window, holding myself taut as we passed the carpet seller, his rugs spread over the grass embankment on the side of the road and pinned up on the trees with long nails. My favourite moment of the day was coming, and I had to be ready.

If I wasn’t prepared – if a kick broke my concentration, or wrestling siblings knocked my head out of its line of sight – I’d miss the miracle. Because when we reached the end of that cramped road, our car dodging donkey carts and street sellers and dashing children, and turned the corner – in that instant, the world opened out. Lahore vanished around me. All I could see, stretching out for miles, were huge empty elds.

We’d crossed from city into fairy tale. And, every morning, no one noticed but me.

I’ve forgotten so much of my early life, but those elds have

stayed with me. How could there be so much empty land in the middle of crowded, parched, shouting Lahore? How could anything be so deeply, achingly green? I felt that green on my skin and in my dry throat. The school playground never kept its grass more than a few days. Every year it was resown, optimistically, the seeds sending up dark dusty tufts, as though Lahore might decide to change its climate. But within days the ground had baked solid and brown, under the blasting sun and the thousands of small feet in shiny black shoes.

Not those elds. Through summer sun, monsoon downpour and winter mists, and the spring whose creeping heat I experienced like the sound of a distant, sinister drum, they stayed lush. I kept my stare xed on that beautiful alien colour as the trees icked past the window: a long row of trunks, lining the road, which measured out my journey to school as rhythmically as a heartbeat.

The elds were perfectly, shimmeringly at. No people crossed them. No hills, no valleys, no machinery. There was nothing for the eye to light on. Good, I thought. My gaze didn’t want to be distracted. It wanted to y and y, like a bird skimming the grass, without stopping. I imagined picking up every inch of ground and storing that expanse inside me for when I needed it. Later – standing on the edge of the school playground, watching the ies cluster by my feet, or staring blankly at my teacher’s face in the classroom – I could take myself back to the elds, and live there in the cool quiet by myself.

Everything in my Lahore was cramped. Five of us shared a bedroom, four of us shared the back seat. So that expansive emptiness seemed impossible: like a glimpse of the divine. I could send my eyes running o over the elds, even as I stayed jammed in the back seat of the car against my little sister Forget-Me-Not, my hands up against the glass (‘Don’t touch the glass,’ my mother said, from the front seat. ‘It leaves a smear that never comes o .’). Running, in my mind, faster than was possible, stretching my

muscles as hard as they could possibly be stretched. In that space, no matter how I moved – if I ung myself or rolled or cartwheeled (I didn’t know how to cartwheel) – I knew I wouldn’t come up against anything.

If I walked far enough, I thought, over those elds, out past the edges of my vision, soon the road and the car and my ghting sisters would vanish, and there would just be me. Standing in the middle of that atness, turning slowly, with nothing to see on any side. Then, maybe, I could rest.

Near the end of my British grandmother’s life, one memory came back to her again and again, as her appetite dwindled and she shrank into her chair.

‘I’m with my friend Joy,’ she said to me, smiling at the air, one autumn morning six weeks before she died. ‘Oh, Joy. She was wonderful. It was the right name for her. Joy!’

‘How old were you?’ I was arranging ve tiny pieces of dolly mixture on a plate at her elbow, hoping to tempt her.

‘Perhaps about ten. I can just see her now. Walking up the hill in front of me.’ Her smile caught and stayed. Half an hour later, she’d lost the memory of telling me and she described the scene again: watching Joy climb that hill, and climbing up after her.

I think that memory of walking after Joy lay at the core of who my grandmother was. To steal a phrase by Virginia Woolf, it was the base that her life stood upon.

Woolf considered her own life founded on an early memory, from when she was a child on holiday in St Ives, in Cornwall. She describes the scene in an autobiographical fragment from ‘Sketch of the Past’:

If life has a base that it stands upon, if it is a bowl that one lls and lls and lls – then my bowl without a doubt stands upon this memory . . . It is of hearing the waves breaking, one, two, one,

two, and sending a splash of water over the beach; and then breaking, one, two, one, two, behind a yellow blind. It is of hearing the blind draw its little acorn across the oor as the wind blew the blind out. It is of lying and hearing this splash and seeing this light, and feeling, it is almost impossible that I should be here; of feeling the purest ecstasy I can conceive.

A base that life stands upon. Woolf connects everything she is to that simple early memory. What base does my life stand upon?

When I read ‘Sketch of the Past’ as an undergraduate, I put down the book and knew, without doubt, that my life stands upon those at, empty elds in Lahore.

Flat landscapes, I realized, had always given meaning to a world that made no sense to me. We grew up watching life through living-room windows which had been covered rst with bars and then with a layer of chicken wire, just in case. My mother was British and bewildered; my father was Pakistani, and knew – he said – how things worked, and what was at stake. He made the rules, and it did not occur to my mother that they might be broken. No speaking to neighbours. No inviting classmates or friends round. And nice girls stayed at home, safe behind the chicken wire.

Usually my mother got on quietly with things, while chaos raged around us. At ve every morning she rose to boil the huge silver daigchees of milk, so that by the time we woke up it would be safe and cool to drink. She killed cockroaches when they crawled out of drains; she ran downstairs when my grandmother hollered for her; she knelt every evening by the power outlet, burning pesticide mats to kill the mosquitoes. My mother thrives in a crisis, and every night in Pakistan was a small crisis. It wouldn’t occur to her to complain. But the relentless noise of Lahore pierced even her stoicism. The car horns, pressed down and held with both hands. The shouting. The motorcycles revving. The sudden bangs that were usually recrackers and not guns. Usually.

So every once in a while, my mother would break, would wander through the house, back and forth, crying out against the relentless noise. She had grown up in rural Scotland, a lonely child in a half-empty house, where you could hear one car coming for a mile and every creak sounded loud. The only life I knew was hot and dirty and crowded, bodies pressed against each other: oil sizzling, loud music on my grandmother’s TV, my uncles arguing. Between fourteen and twenty- ve people lived in my house in Lahore at any one time, coming and going. So did, at various times, rabbits, goats, chickens, geese, budgies, dogs, cats, turkeys, peacocks, chicks and parrots. My father had his own bedroom; the rest of us – my mother, me and three sisters – lived in another, piling over each other, shouting and ghting in hushed voices so as not to wake him while he slept. There was nowhere to run.

Things happened all at once, all the time. My grandfather, half mad, paced the corridors shouting ‘Help!’ The house caught re. Furniture piled up and was covered with sheets, as if the chairs and sofas had died and were waiting to be laid out for burial. Our garden was a little bleached patch, too hot to step into in summer. At night mosquitoes arrived, buzzing malaria, and we hid inside. Armed robbers came to the house; we children sat in the bath and turned o all the lights and waited, holding our breath, as downstairs a man held a gun to my aunt’s head.

Life bit hard, I knew. It was a fact one couldn’t get around. The way things were. Everything was scary and dangerous and happening right in front of me. Reality meant living continuously up against a basic truth: that the world would hide nothing from you, even if you were eight years old.

Those elds on the way to school gave me a fantasy of space to stretch out in, and distance from the chaos at home. And yet they also seemed to sum up the way life was, when I was eight and starting to notice things. The world was a at plain with nowhere to hide.

It was better to know, I thought, than to have teachers and friends pretend that everything was all right. Nothing was all right. I was a small hard creature, knowing what I knew; as resolute and still and enclosed in myself as the at landscape that drew me towards it. I waited, every morning, as the dawn mists rose over Lahore, for the car to round the corner and open out on to those elds. And the at elds told me, wordlessly, that I wasn’t mad. That I knew something important. That they knew too, and would re ect it back to me, whenever I needed.

Flat landscapes have always given me a way to love myself.

I had no words for this feeling, in either English or Urdu. There was no space, in the house, in my family, in my head, to say them or struggle towards them. There was no space at all. So, I said nothing, not to my uncle who drove us to school, leaning out of the window to yell the very worst words in Punjabi at other cars, nor to my parents or my sisters. Instead I stared silently at the electric blue signs in front of the elds. They promised a hospital, in Urdu, which I couldn’t read quickly enough – my uncle liked to take the car up to a hundred miles an hour, to make us scream – and English, which I could.

The signs stood there for as long as I can remember, guarding those empty elds. As we grew, and the back seat of the car became more and more cramped, the signs began to ake and peel and buckle, until no one could read them at all. Nothing ever got built there. Or rather, I left Pakistan in a hurry, eight years later, long before any hospital sprang up.

I didn’t think much about those elds again for years, until I took up a place on a Masters course in Cambridge.

I’d never even visited Cambridge before. This didn’t matter. It was part of my stance, at that time, that decisions ultimately meant nothing. It didn’t matter how long you pored over them: you could stare at the surface of a problem from all angles, and still be none

the wiser. So I glanced over my options and said yes to Cambridge and thought no more about it.

Still groggy from a hasty root canal performed that same morning, I wobbled south on the train from Scotland, staying overnight in the beautiful cathedral city of Ely with an old friend of my mother’s. She drove me to Cambridge the next day, as the sun was rising. Halfway through the trip, I bolted upright and stared out of the window, her conversation fading in my ears. Sun cut through the haze on the at sea of the elds, and as the pale brown tree trunks whipped past, I realized that I had been here, or a version of here, before. Without warning, I was back in Lahore.

I spent that year in Cambridge like a ghost, unable to think or feel. My stomach had always hurt, since I was a little girl, and no one could work out why. Now the pain grew so bad that I stopped eating for days at a time. I went to classes and said nothing, fumbling in my bag under the seminar table for painkillers and staring at the opposite wall. The wind which ran its blade down the at land seemed to scrape away all colour. What I remember is bleached green, and my feet in leather shoes, moving over the ground as if through a trance. I remember standing near the River Cam, staring at the pale elds, quivering under frost, and how my gaze looped over and over their at surfaces, hypnotically. As though seeking something it could never nd – and didn’t want to nd, even as it went on looking.

Something was wrong, I knew. Something was beating its wings at the edge of my memory, trying to get in, like a bird hitting a window. But whenever I tried to look straight at that thought, that feeling, all I saw in my mind was an image of the at elds of Lahore, stretching as far as I could see, with nothing particular to focus on. It was as though I was trying to remember something which didn’t exist. I searched the landscape for a clue, anything at all to guide me, and came up with nothing. And yet the image of that bare space held me tight in its grip.

From the outside I seemed ne. I went to classes and wrote my dissertation and did my laundry. We studied W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, a book about haunting and memory. Our tutor took us on a eld trip to Orford Ness, one of the landscapes that Sebald describes in his book: a spit of shingle in Su olk. It was very quiet and very at. Pebbles crunched underfoot, and on the bare horizon the bodies of lost things stuck up out of the land. Abandoned military buildings, rusted and aking. Twisted metal remnants. Orford Ness had been used for aborted army experiments for many years in the twentieth century: grand projects started and cut short before they came to fruition. A few birds walked on long legs around these dead monuments. The place could have been drawn straight out of a post-apocalyptic lm, levelled as though by some catastrophe.

But I didn’t need the rusting military towers or the snapped-o bases of the radio masts to be thrilled by Orford Ness. What fascinated me was its atness. Gazing across the shingle, I felt how little the landscape needed me. It was indi erent. I could have been a tuft of thistledown, blown harmlessly over the at expanse, leaving no trace. Displaying everything on a single plane, Orford Ness gave up everything it had to o er, immediately – as though it had no fear of my judgement; no need to seduce me with deferred promises, of a new delight just round the next bend, of a peak to be scaled, or crevasse to be explored. This was a landscape absorbed, purely, in being itself.

The other students asked intelligent questions and made searching, thoughtful remarks about Sebald, but I stayed silent. I was held captive by this unyielding, silent space, and I began to understand two things. That atness wasn’t an absence – not in the way we might assume it is – but something strong and original and living. And that you could fall in love with atness, gazing at it forever.

‘The thing is,’ I said to the therapist, ‘nothing that awful ever happened to me.’

Eight years had passed since Orford Ness, and fteen since Pakistan. I was thirty now, mostly made of bones, and things – I had nally admitted – were bad. I tucked myself into the corner of the too-big chair and stared at the waste-paper basket.

‘Not really. Not compared to what happens to some people in Pakistan. I’m a girl with an education. That makes me one of the very, very luckiest people. And everything is okay now, I have a great life. But I just feel so desperate. Like we’re actually all walking through a wasteland, and no one can see it except me. And I can’t stop thinking about Pakistan, and I don’t even know why, because there’s nothing really to think about.’

My therapist screwed up her face, sympathetically.

‘That’s the way with complex trauma,’ she said. ‘It’s more than one event, or even several. It’s like this tinge of horror that su uses everything.’

The rst time the therapist had mentioned complex trauma, I’d stared blankly at her. She was exaggerating, I thought. Trauma derived from properly horrifying experiences, like a war or a terrible attack, and involved ashbacks to the event. How could I be traumatized when there was no event to ash back to? There was nothing I could point to and say: this is what happened to me, this is why I’m the way I am. Nothing to explain the paralysing horror I had always forced myself through; the war zone I saw in the world when other people seemed to see beauty. When I looked back at my childhood, it was impossible to pick out any particular act of violence or fear which stood out as exceptional, as the root of it all. So why did my life in Pakistan continue to grip me so tightly: a smear on my mind which would never come o ?

But I’d begun, slowly, to understand that complex post-traumatic stress disorder, or cPTSD, was di erent. It was particularly dicult to treat, because – like a at landscape – it didn’t o er a

signi cant landmark, an event, that you could focus on and work with. Complex post-traumatic stress, according to the psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman, is the result of ‘prolonged, repeated trauma’, rather than individual traumatic events. It’s what happens when you’re born into a world, shaped by a world, where there’s no safety, ever. When the people who should take care of you are, instead, scary and unreliable, and when you live years and years without the belief that escape is possible.

When you come from a world like this, when all your muscles are trained to tension and suspicion, normal life feels unbearable. It doesn’t make sense, getting up, going to class, eating lunch, returning home, sleeping. You don’t trust it. It doesn’t feel real. And unreality can hurt more than pain.

So, I lived my life in Britain, the one that was supposed to be better – my happy ending, away from my father and that house in Pakistan – feeling as though I was on re, and I couldn’t explain why. I walked around in the world and held a neutral look on my face, all the time, while something inside cried and cried. My body didn’t seem to work properly: I was always tired. Seeing other people, even people I loved, made me panic and vanish inside myself. And I couldn’t seem to feel enough. I couldn’t desire things, desire others, in the way they were o ered to me, while everyone around me was falling in and out of love.

Worse, when I tried to describe what I felt, people seemed bafed, or scared.

‘But it’s okay! You’re here now!’

‘But isn’t that just what life is like in Pakistan?’

And I could only retreat into silence, because I couldn’t explain it.

‘It’s all right that you feel this way,’ my therapist said gently. ‘Things were unsafe, all the time. And no one could help you.’

My father died in August 2019, a month after I turned thirty. I was at a wedding, still chatting to my friend as I picked up my phone and read my sister’s text:

Aba had a heart attack this morning and died.

I showed the text to everyone at the table, including the people I didn’t know, then laughed at their horri ed faces and got up and walked outside. It was raining faintly, and my feet grew wet and slipped around inside their red summer sandals.

There was no question of attending the funeral, even if I had been welcome. My Pakistani passport had expired. Instead, I tracked down footage of it on Facebook. My father was buried within twenty-four hours, amid rain and shouting mourners grappling his body in monsoon mud. I saved photos of that body, grey and bruised, to look at later. So that I would know where he was.

For the rst months after he died I couldn’t bear the thought that he was in the earth. Not that I felt sad for him. It seemed appropriate, and perhaps overdue. But if in life I had been able to put him aside, in death he suddenly existed very physically in the world. The ground had swallowed him up, but he was still there, all bones and eyes and muscle, newly made into an object which wouldn’t go away.

So I did what comforts me: some research. How quickly he rotted, I discovered, would depend on the manner of his burial, the pH and dampness of the soil, the ambient temperature, the depth of the grave, whether he was wrapped in cloths. I scrutinized the photos, trying to work these things out. I didn’t feel con dent in what I concluded. I made a chart of possible options for his decay. There were too many. I hid the chart under a pile of papers.

Through my academic networks, I tracked down and emailed a forensic pathologist, apologetically. The pathologist was kind, but she con rmed my fears: it could be anything up to – what? Nine months? A year? – before all that was left were his bones, and I could bring my gaze back up from the depths of the soil to the tranquil at surface, a world without him, now, on it.

Why do I love at landscapes so much? Why do they quieten the thing in me that’s always crying? Flatness is a puzzling thing to love. Ever since the Romantic poets tramped around Europe, rhapsodizing over the magni cence of dramatic landscapes, it’s mountains – not atlands – which have been considered beautiful, breathtaking, valuable. Mont Blanc was a particular favourite in the nineteenth century, thrusting upwards into the poetry of Percy Shelley and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The iconic Romantic painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818), by Caspar David Friedrich, places mountains swirling with mists at centre-stage. Mountains shape our emotions into surges of joy, plunges of passion; we come away feeling emotionally refreshed.

They’ve also come to symbolize human power, ambition, success. The very sight of a mountain, o ering a summit to reach, pushes one to exceed oneself, to drive beyond one’s limitations. How coercive that is. How cruel, to instil the belief that one must always be striving. People climb Everest, they tell us, because it is there. Pakistan is proud of its K2, perhaps the most dangerous mountain in the world: for every four climbers who reach the summit, a fth dies. In Pakistan, these stories are told with a hint of relish. On mountains – as in stories – tragedy is what counts. The country fought hard to keep territorial control over the Karakoram Mountains, shoving back against India and China for its share of the shaggy range which borders the Himalayas. In 1999, when I was ten, India and Pakistan fought the Kargil War, high up in the mountains, and thousands of people died. As with so many deaths in Pakistani history, no one seems quite sure – or perhaps wants to know – exactly how many. A big number, though. Mountains are the all-important stage for personal and national achievement: summits reached, blood spilled.

If mountains are poetry, atlands are prose: cookbooks or technical manuals, practical but dull. You can build towns on at land, construct railways on it, plant crops for food, walk easily across its

level surface. Flatness enables the boring business of living – but it’s hard to imagine anything really exciting happening there. So how do we make stories about at landscapes? Is there anything at all to say about a space in which nothing important seems to happen?

And if not – why do I want, endlessly, to look at and talk about them?

When we stand in a at landscape, we nd ourselves in a kind of contradiction. Everything there is to see lies freely open to us. And yet there seems to be nothing to see. We don’t know how to organize this space in our minds. How to look at it. We stand scanning, right and left, but there’s nothing to x our eyes on. We are used to ‘reading’ landscapes: moving through a distinct foreground and mid-ground and background. Small, human details in the front; big shadows of relief in the back. But faced with a at landscape, uniform as far as the eye can see, we struggle. It’s as though the landscape is sending us a message that we’re unable to decipher.

And yet we can’t always just pass them by. Underneath all the noisy love songs to mountains, there’s a quiet tradition of writers and artists lingering in at landscapes. L. S. Lowry infuriated local councillors by painting a at seascape for Salford City Council in 1952, where the bare surface of the sea o ers no visual interest. There is a rich line of literary accounts of crossing the wide bare sand ats of Morecambe Bay, where the horizon tricks the eye into disregarding the tide’s swift motion, the patches of treacherous quicksand. And the at landscapes of Orkney hold space open for extraordinary wide skies, inspiring a tradition of uncanny myths and legends, recording the sensation of things lurking just under the surface of our everyday experience. Things which we can never fully know.

I think this is the heart of it. Flat landscapes ask us to tolerate not knowing things. Not knowing what is beneath the surface, whether anything is. A at landscape’s combination of complete exposure