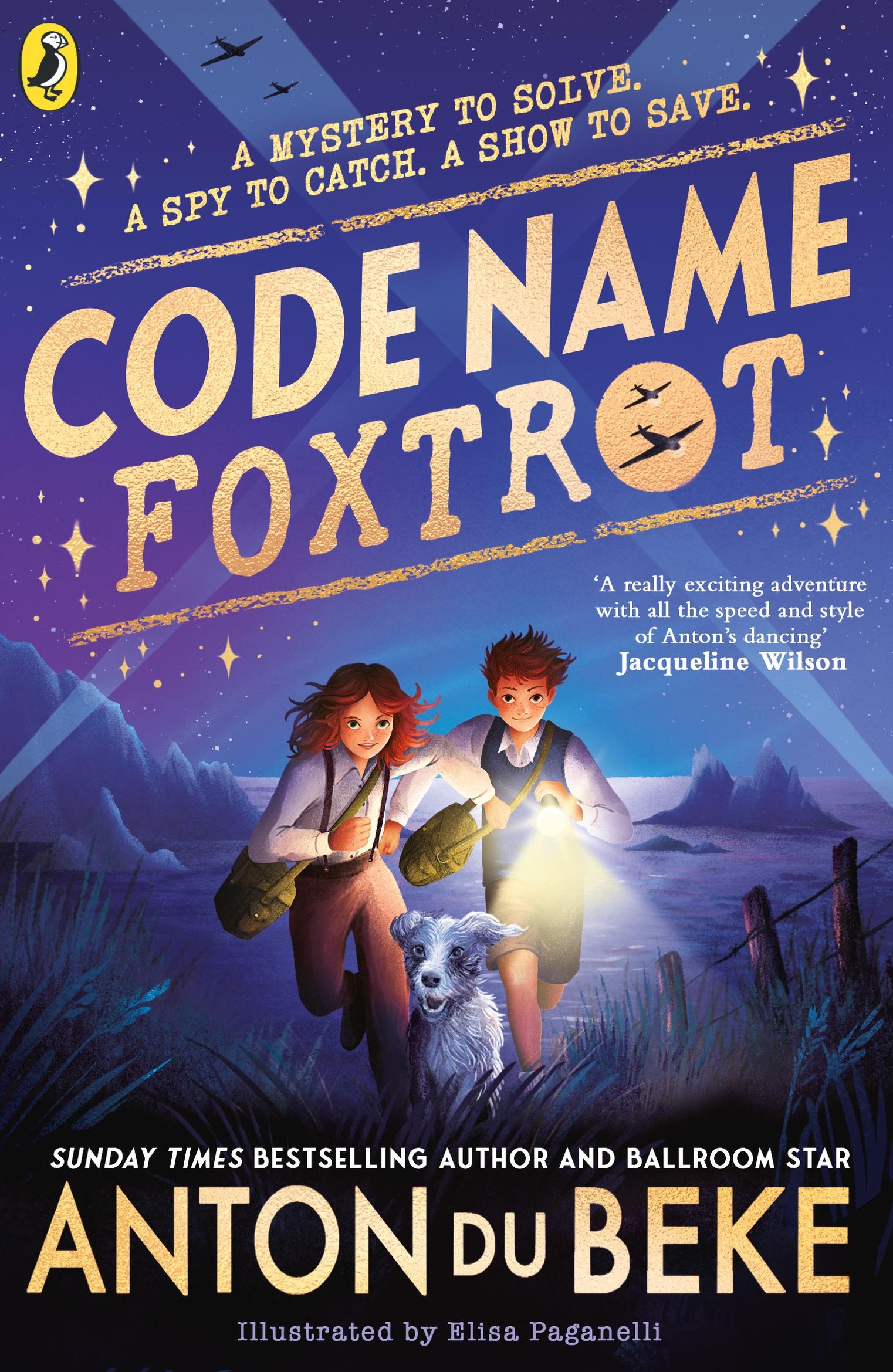

PUFFin bOOKs

PUFFIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Puffin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

www.penguin.co.uk

www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2024

Text copyright © Anton Du Beke, 2024 Illustrations by Elisa Pagnelli

Illustrations copyright © Elisa Paganelli, 2024 Endmatter content by Lucy Doncaster

The moral right of the author and illustrator has been asserted

Set in 13.3/18pt Bembo Book MT Pro Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn : 978–0–241–69915–7

All correspondence to: Puffin Books

Penguin Random House Children’s

One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London s W 11 7b W

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This book is dedicated to and inspired by my twins. Without you this book wouldn’t have happened.

Keep Calm and Carry On

Tbe polishing

here weren’t many things Harry Morton didn’t like. His teachers had always remarked upon what a helpful, agreeable boy he was – and certainly at the Little Mayfair Tearoom where his parents worked, he was often to be found polishing the brass rail round the dance floor, fixing a crooked chair or taking the musicians their finger sandwiches before the entertainments began. But the one thing Harry hated, packing was kneeling on his bedroom floor, stuffing socks into his suitcase with all the fury of a storm.

But more than anything in the world, was . Now he his suitcase with all the fury of a storm.

In went his nightshirt.

In went his boots.

In went short trousers, spare shoelaces, his pocket

In went short trousers, spare shoelaces, his pocket knife and gas mask.

He was still wrestling the suitcase shut when his sister Rosie came through the door. ‘Aren’t you forgetting something?’

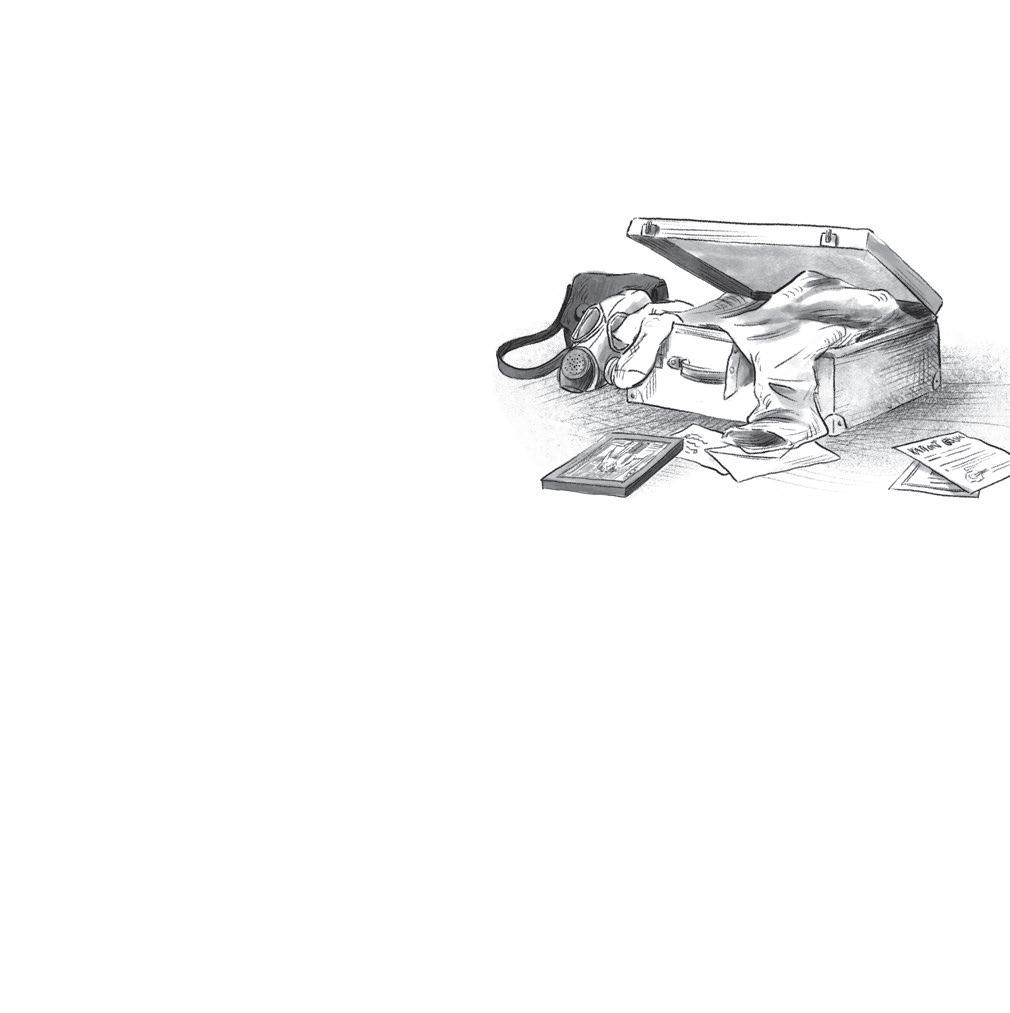

Harry looked round. Rosie was precisely six minutes and thirty-eight seconds older than Harry – and, of course, she’d packed her suitcase perfectly. It wasn’t bulging in one corner, pyjamas weren’t trailing out of it and the clasp didn’t keep popping open.

Rosie picked up a picture frame from the bedside table. ‘Aren’t you going to take it? Who knows how long we’ll be gone?’

Harry gazed at the photograph. Had it really only been taken eight short months ago? In the picture it was after dark at the Little Mayfair Tearoom, the cafe and dance hall directly beneath them. The dancers milled, the

musicians played – and there were Harry and Rosie, together with Mum and Dad. In the corner, the Christmas tree sparkled. Mum’s eyes glittered like the baubles on the tree – and the way Dad stood, so steadfast, made it difficult to believe there was a war on at all.

Harry wasn’t sure he could bear to look at the picture, but Rosie was right. Where they were going, they’d be grateful for the reminder.

As if on cue, his suitcase popped open and he slipped the picture inside.

Rosie got down on her knees. ‘Here, I’ll do it. You go and find Mum. She said she’s got a letter.’

The storm blowing through Harry seemed calmer now Rosie was here. Perhaps it was the effect of the photograph too. Christmas felt such a long time ago, but what a Christmas it had been . . .

Down below, the tearoom was waking up for the lunchtime service. This was what Harry would miss: the buzz of the tearoom, anticipation building for the music and dancing each night. How many times had he crept out of bed and crouched by the back door, listening to the soaring saxophone, the stampeding piano? How often had he dared sneak a peek at the dancers turning underneath the lights?

And now it was being taken from him.

was being sent away from He walked down to the tearoom. The walls here used to be plastered with pictures of the famous dancers who’d come to thrill the crowds. Between those handbills other keep calm and carry on the first – which was exactly what Harry had thought they were doing, until Mum’s announcement last night. he it. posters now loomed. ordered

declared another, as if it might be found in the kitchen garden, buried among the potatoes.

The Little Mayfair Tearoom had sat in the heart of London’s West End for twelve happy years, opening its doors the very same day the midwife told Mum she was carrying twins. Harry and Rosie had grown up listening to the music here.

Tonight, though, neither Harry nor Rosie would hear a single note.

They’d already be hundreds of miles away.

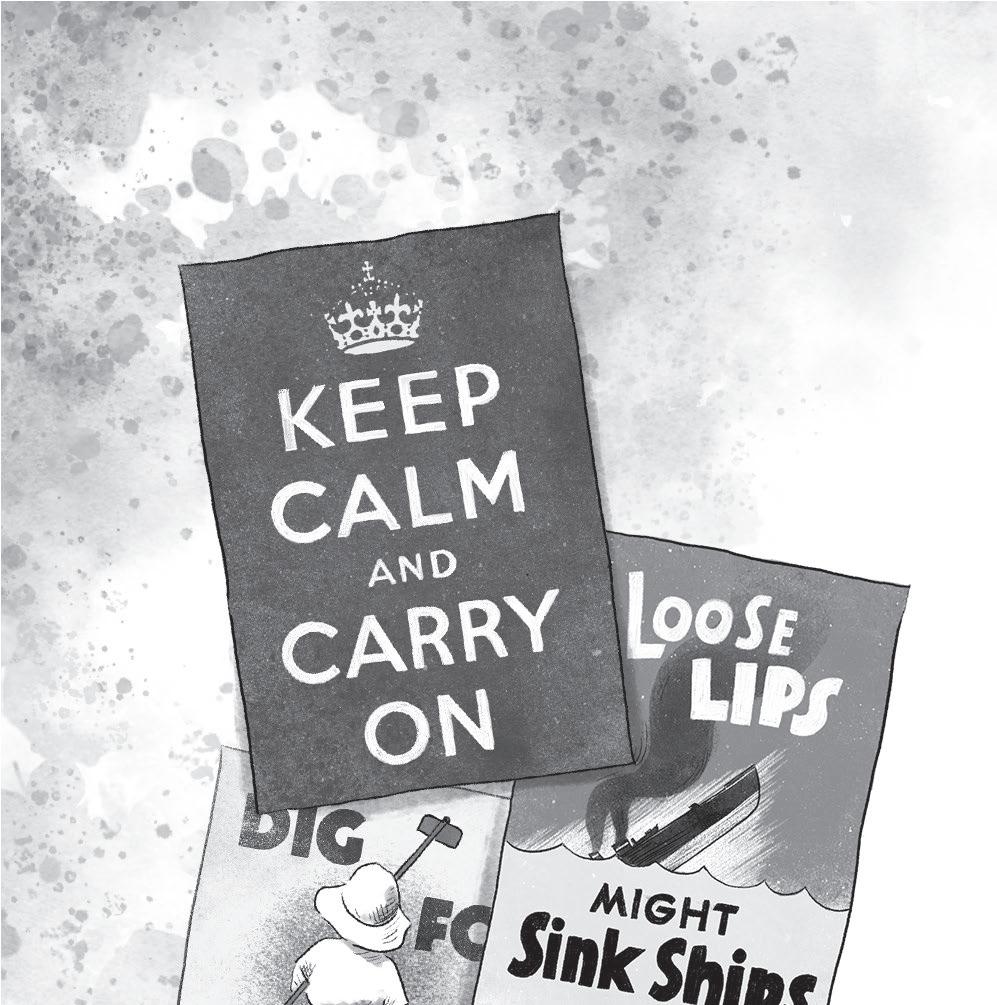

Mum was waiting in the back office. The same photograph from last Christmas was framed on the wall here. Harry stared at it as Mum handed him one envelope, then another.

‘Your tickets are in here,’ she said, ‘and this one’s for when you arrive.’

Harry took the first envelope.

‘I’ve arranged the taxicab at the other end, so look out for the driver at the station. It’s a big house on the edge of the town – where the bluff meets the bay.’ A

pained expression flickered over Mum’s face. ‘Harry, it’s for the best. You do know that, don’t you?’

Harry was still staring at the letter. Rupert Prendergast. He sounded like a gentleman villain from the stories in one of those old penny dreadfuls Rosie loved to read. Nautilus House. Cotterill Cove. Places with names like that were as far away from London as could possibly be. Far away from the tearoom. Far away from . . . His eyes flashed back to the photograph of Mum and Dad, and his heart skipped a beat.

That was when Rosie came into the room, carrying the two cases.

Harry handed her the letter.

‘Rupert . . . Prendergast ?’ she read out loud.

‘You don’t have to do this, Mum. We want to stay – don’t we, Rosie? That’s what we told Dad, before he – before he –’ Harry had to catch his breath – ‘went away. We promised to help with the tearoom and –’

‘Things have changed.’ Mum was trying hard to be firm, but her voice trembled. ‘The war isn’t some faroff thing any more. It’s coming to London, to our home. Last Christmas it was easy to believe it wasn’t really happening. Now . . .’

‘We can help, Mum,’ Harry insisted.

‘You’ll be safe in Cotterill Cove. London’s about to become a very dangerous place – and I can’t have you in harm’s way.’

Harry opened his mouth, but Mum said, ‘No, Harry, please. You’ll write to me, and I’ll write to you. And who knows? Maybe, by Christmas, all this will be over – and we’ll be back here with Dad, listening to the orchestra play.’

Through the office doorway, one of the kitchen staff was waving. It could mean only one thing.

‘Harry, Rosie, the taxicab’s here. You’re to look after each other. I’m afraid this is goodbye.’

MChapter Two

The Lonely Road North

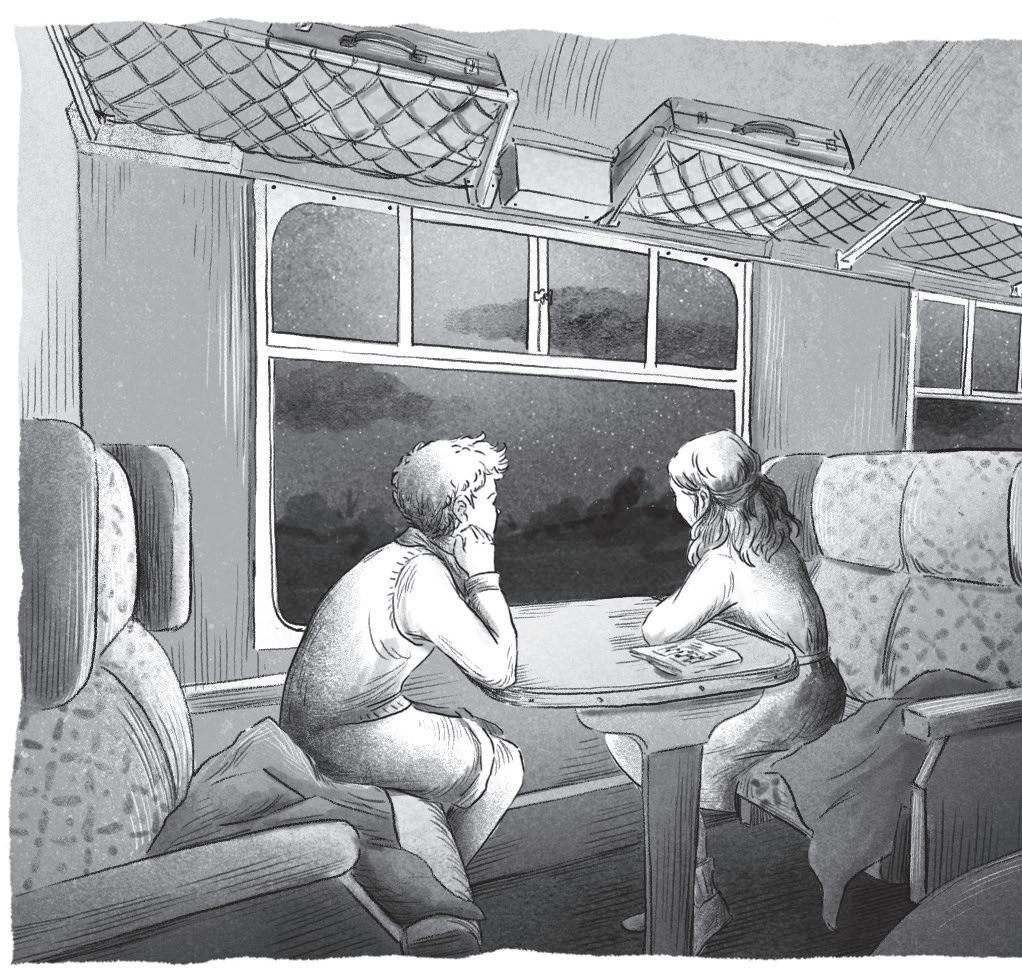

um had prepared potted beef sandwiches for Harry and Wensleydale cheese for Rosie. Both came out of the family rations. Harry was halfway through his while the terraces of London still rushed by.

Rosie sighed. ‘Slow down – we’ve got a long way to go.’

‘A long way is right,’ said Harry sometime later, once London had faded and they were sailing across a landscape of green summer fields. ‘Do you think this is the furthest we’ve ever been away from home?’

Rosie had been focusing on a book of crossword puzzles, the kind she used to love sharing with Dad, but now she looked up. She didn’t like watching the fields and villages flying past. She’d tried to hide it from

Mum, but she was every bit as nervous about this voyage as Harry. Sometimes it just didn’t help to show it. Mum had enough to worry about. ‘We’ve gone further than the distance to Rye.’ It was where they used to spend their holidays.

Harry gawped. ‘And going even further. Hey, Rosie, do you think they have music up north?’

‘I suppose we’ll find out. But in the meantime . . .’

Rosie flipped her book of puzzles round and presented it to Harry. ‘Six down. Eight letters. A man on the run from the law. Any ideas?’

‘That’s too much like schoolwork! I haven’t thought about school all summer . . .’ Harry shot up in his seat so suddenly he nearly crashed into the carriage roof.

‘FUGITIVE !’

‘What?’

‘FUGITIVE – a man on the run from the law. Or . . .’ He slumped back down. ‘Twins sent away when they promised Dad they’d look after Mum.’

This was what was weighing on Harry the most – that Mum would be left on her own. Not for the first time his mind flashed back to the night before Dad decamped. Late at night, helping Dad sweep the dance floor, Harry had thrown his arms round him until, finally, Dad had said, ‘You’ll have to be brave for me, son. You’re going to have to look after Mum while I’m gone.’ And Harry had promised. He’d looked Dad in the eye and made a solemn vow.

A vow he was breaking.

Rosie was scribbling in the puzzle book. ‘We’re not fugitives,’ she said. ‘We’re more like . . . exiles. Yes, that’s it. Exiled twins sent to some far-flung corner of the world where they’ll not know a soul.’

‘Sounds delightful.’ Then he stuffed the last of his sandwich into his mouth and beamed.

‘Can I have some of yours?’

The late- summer light was paling – but, by Rosie’s reckoning, they were still miles from their destination. She’d been eking out her sandwich for hours, but she’d never been able to ignore Harry’s pleading eyes. The twins looked alike, with dark auburn hair and faces dusted with freckles – but Harry’s eyes were dark while Rosie’s were green, and he had always been able to use them to get what he wanted.

‘I told you to save yours,’ she said but handed him half all the same.

‘Thanks, Rosie,’ said Harry.

At least he was sheepish about it. Ordinarily, Rosie never minded when Harry got his way – but right now she wished he could just take a breath, slow down and think about things. Mum had cautioned them to be on their best behaviour, and Rosie was determined to see it through . . .

The train had been emptying all day. The soldiers hopping on and off became fewer as they weaved their way north; the flurry of clerks and day trippers gradually petered away. Sometimes Rosie saw a figure tramping past their carriage – but it felt as if the twins were the only ones left on the long, lonely road to Cotterill Cove.

‘It’s like we’ve been gone for days,’ Harry said, pressing his face against the glass. ‘Is this train even moving ? We could walk faster than this!’ He got up and opened the carriage door. The guard was just up ahead. Harry was about to canter after him when the train ground to a halt, throwing him against the wall.

There was too much nervous energy coursing through Harry. There was a lot of it inside Rosie too, but she was managing to keep it in check.

‘I’ll find out what’s happened,’ she said, hoisting him up. Then she revealed the paper packet of mint humbugs she’d been saving since London. ‘Eat your fill. I’ll be back in a moment.’

Rosie picked her way along the train, catching up with the guard as he opened one of the other carriages. Inside sat a dark-haired young man of about twenty, his hazel eyes half hidden beneath his fishing hat, a dark raincoat folded at his side.

‘Sir,’ she began, catching the guard’s eye, ‘is this Cotterill Cove?’

‘We’re not far,’ grumped the guard, ‘but I can’t be sayin’ how long we’ll be sittin’ here. You two young ’uns might want to bed down.’

‘Bed down?’ said Rosie in alarm.

‘We’re waitin’ for a signal. Signalman’s not at his station. Don’t worry. It shan’t be all night. We’ve all got beds to get back to, lassie. My Dash is wai ting. He’ll be wanting his dinner and a lick of my boots.’

Rosie shuddered. She hoped Dash was the train guard’s dog. ‘But where is he?’

The guard shrugged. ‘We’ve all got war duties to attend to on top of our jobs, lass. The signalman will be back when he’s good an’ ready.’

Rosie watched the guard leaving with a heavy heart. She was about to go and tell Harry the news when the dark-haired man piped up.

‘War duties, my foot. If I know that signalman, he’ll be sinking a pint up at the Crown and Anchor.’

Rosie stared.

‘The pub in Cotterill Cove. Just sit tight, girlie. We’ll get there eventually. The track forks here. You don’t want to take the wrong one. All the signs have been taken down – to confuse the Germans if they come.’

It was the same in London. A city could be disorientating without any street signs, so every one had been taken down the moment war began.

‘Are you from Cotterill Cove?’

The young man extended his hand. ‘Name’s Calderdale. Doug if you like. I’ve been working the

fishing boats out in the cove.’ He grinned. ‘Who knows, maybe I’ll get there by dawn and be able to get back on the water.’ Then he pulled the fishing hat over his eyes as if going to sleep.

Harry hadn’t got through as many humbugs as Rosie had thought he would – so, when she got back, there were still some left to share.

‘I bet the dance floor’s full back home,’ said Harry wistfully. ‘I bet there’s music and . . .’ He was tying himself in knots. ‘Maybe we ought to get out and walk. This man who’s waiting for us at the station – he’s not going to wait forever, is he?’

‘He might wait.’

‘He won’t. He’ll get there and we won’t be anywhere in sight. Just like – just like Dad . Dad’s going to come back from France and we won’t be there to meet him.’

Rosie’s cheeks flushed. She tried not to catch Harry’s eye, just stared into the black window instead.

‘You think he’s already dead, don’t you?’ Harry blurted out.

What was there to say? Dad had gone off soldiering in France, and when France was conquered, he hadn’t made it home. Countless soldiers had been ferried back over stormy seas, but Dad hadn’t been one of

them. Happy endings happened in stories, but how often did they happen in real life? Mum said he was still out there but . . . sometimes people needed to believe more than they really did. Sometimes being brave meant pretending.

‘I can see it on your face. You don’t think he’s ever coming home.’

Harry’s big, pleading eyes were brimming with tears. Rosie reached out and wiped them away. ‘I’m desperate for him to come back. Harry, I do believe.’ She wanted to believe but that was a very different thing. ‘But here we are, little brother, and –’

‘I’m only six minutes younger than you.’

‘Six minutes and thirty-eight seconds.’ Rosie smiled.

‘Harry, if Dad’s still out there, he’s working it out. Down in London, Mum’s working it out too. And me and you? Well, at least we’ve got each other.’ She reached into her pocket and pulled out the envelope from Mum, the one addressed to this Uncle Rupert, whoever he was. ‘Nautilus House, Cotterill Cove,’ she read. ‘How hard can it be? If the driver isn’t there, we’ll just find it ourselves.’

Chapter Three

NWelcome to Cotterill Cove

ight had cast its cloak as the train finally chugged into Cotterill Cove.

Dad’s silver pocket watch – Harry wound it diligently every bedtime – said it was after ten o’clock. The signalman must have been missing for hours – but here was the tiny station at the end of the line. It was nothing like King’s Cross, thought Harry, as he looked out of the train: just a single platform and a ticket office. The night was thick with fog.

Rosie had fallen asleep. As the train ground to a halt, Harry stirred her. ‘Come on, let’s see if he’s here.’

Doug Calderdale was already heaving his haversack out of the train when Harry and Rosie carted their suitcases to the carriage door. He’d barely tramped six feet along the platform before the fog wreathed about

him. ‘Better get used to it, kids,’ he called. ‘This stretch of coast’s a devil for it. There’s many a boat lost out on the Finger when the sea fog rolls in.’

As he vanished, he was nothing more than an indistinct ghost in the haze.

‘It’s darker than London.’ Harry dragged his case along the platform. It felt different up here. It was difficult to believe that you could step on a train in London and step off in a place like this.

‘It’s colder too,’ said Rosie.

‘Dark and cold, just the thing for a nice holiday.’ Harry stopped. ‘I don’t see anyone waiting. Do you?’

The ticket office was empty, not even a ticket inspector in sight – certainly not a local taximan waiting for the train to come in. The sign at the counter read closed – ‘As if we need telling!’ Harry snorted – and the salty smell of seaweed hung heavy in the air.

‘Well, come on,’ said Harry. But even he stalled when they stepped out of the ticket office to be swallowed up by fog.

‘I thought there might be a map,’ said Rosie, searching the station walls.

‘No street signs, no maps,’ said Harry. He peered up and down the snaking lane, but there wasn’t any point:

all around was just fog, fog, fog. ‘Pick a direction, then just go?’

Rosie tried to remember what Mum had said. ‘A big house on the edge of town, where the bluff meets the bay.’

‘I suppose what we ought to do is find the town first. Then we can find its edge.’

‘Good logic, Harry,’ said Rosie, rolling her eyes.

Harry stuck out his tongue. Then he sniffed the air. ‘Follow your nose, Rosie. If we find the coast road, we ought to be able to follow it to this Nautilus House.’

It would have been easy to lose one another. The houses crept up on them, appearing without warning – a higgledy-piggledy chaos of old fishermen’s cottages, winding snickets and cobblestone lanes. Cottages clung to steep slopes. A narrow row of shops looked as if they were banked in swirling grey cloud.

‘Don’t you think it’s strange we haven’t seen anybody yet?’ asked Rosie.

Harry took a breath. It wouldn’t do to tell Rosie about the uneasy feeling at the bottom of his stomach; he tried to put on a brave face but it just looked like a grimace. ‘Not really. Who’d want to be out on a night like this?’

‘But . . . no wardens, no air-raid patrol, no . . . nothing?’

‘Just a village full of ghosts then.’

Rosie shuddered. She wasn’t superstitious but she did wish he hadn’t said the word ‘ghosts’.

Up ahead, Harry reached the mouth of a narrow lane. ‘It’s this way.’

Rosie knew he was right when she heard the sea – but it didn’t make it any less harrowing to follow the zigzagging lane.

‘There,’ announced Harry once they reached its end. There wasn’t much to see – not just because of the fog but because the tide was so far out. Underneath them were deep and wide mudflats, revealing rock pools and jagged depressions. Something scuttled into the shadows. A seabird soared away, calling out in its strange mournful way. Fleetingly, the moon appeared above the beach – shipwrecked in grey clouds.

‘Which way from here?’ asked Harry.

Rosie hoped it wasn’t far. The winding streets of Cotterill Cove had been eerie enough, but the wideopen black of the coast felt stranger still. ‘Where the bluff meets the bay. I think it means Nautilus House is on the headland, looking down on the town.’

‘So . . . up.’

‘Up,’ agreed Rosie and led the way.

The steeper the road, the more confident Rosie felt that they’d made the right decision. The problem came when they reached the edge of town and there was still no Nautilus House.

‘The edge of town might mean anything,’ remarked Harry. ‘It might be miles.’

Rosie looked seaward. ‘I can’t see anything. Just mudflats and fog.’

They couldn’t even see Cotterill Cove any longer. When Harry looked back, all he saw were thick coils of fog. He joined Rosie, looking out at the shrouded sea. ‘Want to know what I think?’

‘Let’s hear it.’

‘I reckon if the Nazis really did want to invade, they wouldn’t go for London. They wouldn’t be sailing up the Thames or parachuting into Trafalgar Square. They’d come to a place like this. All that talk in

London – there’s going to be a battle over Buckingham Palace? The RAF are going to fight for the skies? Well, up here the signalman can’t even turn up on time. There could be soldiers out there in the fog right now and nobody would know. It’s almost like you could reach out and –’

A short, sharp horn cut through the silence.

Rosie reached for Harry.

Harry grabbed her arm. ‘Let’s go!’

Rosie hoisted her suitcase and raced along the road. Nautilus House couldn’t be far. They’d get there, hammer on the door, take sanctuary inside and then –

The horn sounded again.

Harry wheeled round, ready to defend his sister.

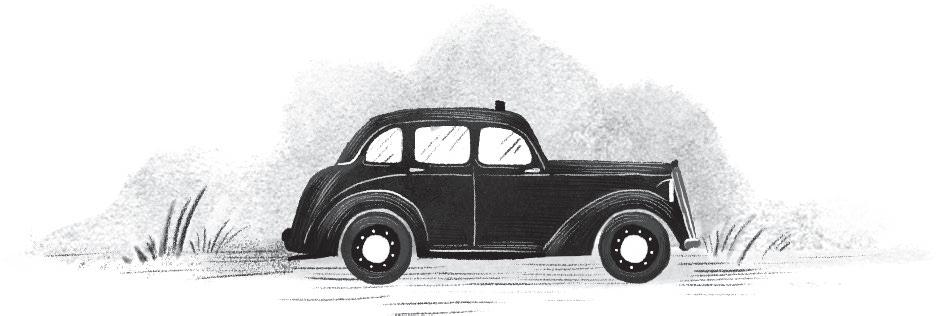

There was a dim outline in the fog, a black Morris Ten, the car Dad used to drive. Its door flew open. A thin, angular figure unfolded from inside.

‘You kids was meant to wait at the station,’ came a deep, throaty voice. The figure strode forward,

revealing a middle-aged man in a dark green jumper, with wisps of greying hair tinged yellow by tobacco.

‘Well, hop on in! We haven’t got all night.’

Rosie came forward. ‘You’re the taxi driver?’

‘No, I’m the Queen of Sheba.’ The stranger guffawed. ‘What do you think I’m doing roving around in the blackout? Sling your cases up back. The name’s Mac and I’ve got a hot toddy waiting for me back at the Crown and Anchor – so let’s get this over with.’

Moments later, they were scrambling into the back of the Morris Ten, and Mac was revving the engine.

‘You kids oughtn’t go wandering, you know? When young Calderdale came in the pub and told me you’d turned up – and then you weren’t there – I almost had a heart attack. You don’t know what’s out there. There’s all sorts at sea.’ He looked over his shoulder with a faintly ridiculous face – his best impression of a monster, Harry presumed. ‘Spooks and ghosts. Spies and crooked sailors. Smugglers, pirates, privateers, corsairs!’

‘You’re joking, aren’t you?’ Harry said.

‘Don’t bet on it. If you’re staying up at old Rupert’s place, you’d better get used to things around here. There’s quicksand that’d gobble you up. If the tide’s