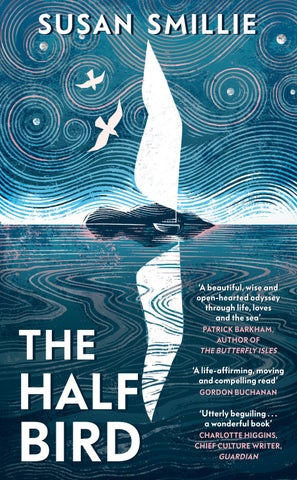

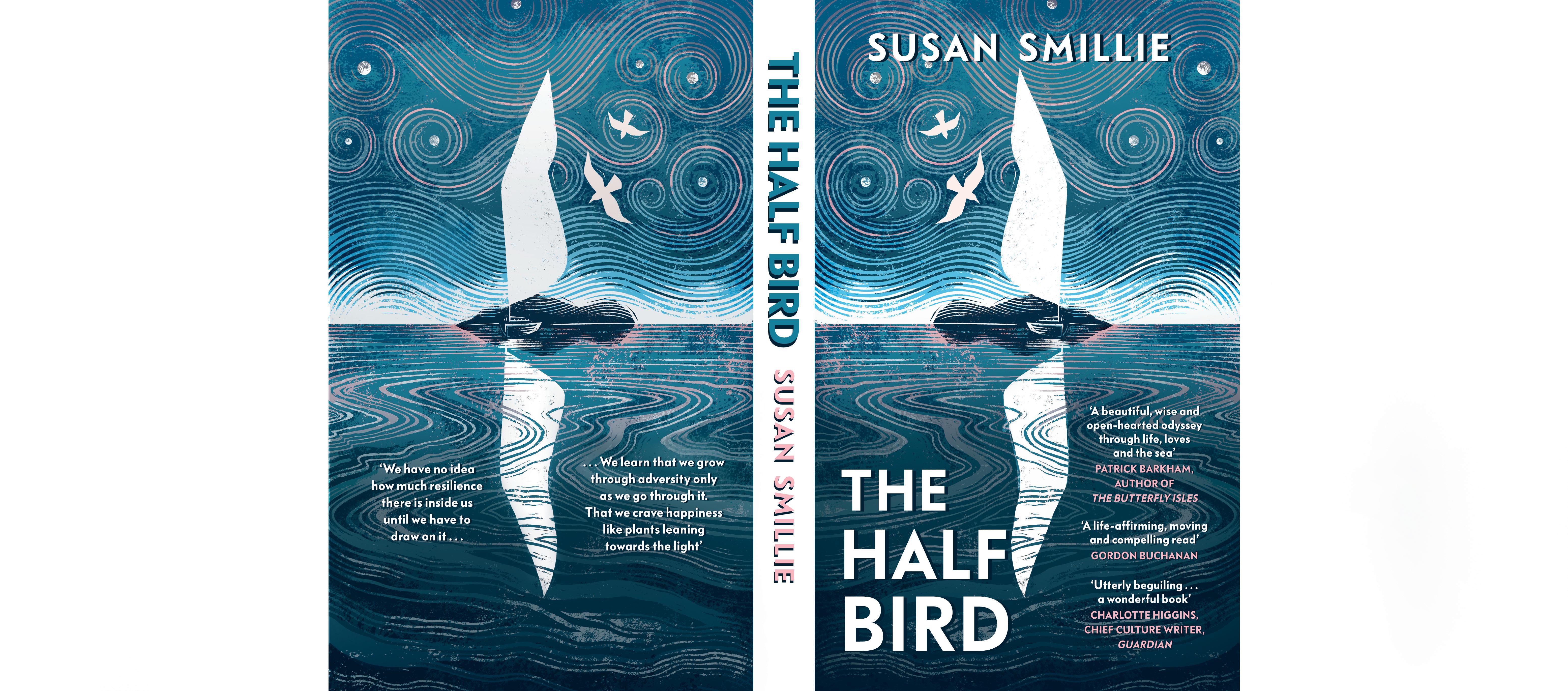

The Half Bird

susan smillie

PENGUIN MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2024 001

Copyright © Susan Smillie, 2024

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Set in 12/14.75pt Bembo Book MT Pro Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn: 978–0–241–55316–9

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

for

Land’s End

0

AUSTRIA

Venice

CROATIA

ALBANIA

GREECE BOSNIA

Naples

Tuscan Archipelago

MONACO

ITALY

Bay of Biscay

FRANCE

Barcelona

Rome

Aeolian Islands

CORSICA SARDINIA

Baleriac Isles

Valencia

SPAIN

PORTUGAL

Lisbon

GIBRALTAR

Mediterranean Sea

SICILY

MALTA

Lampedusa

Tunis

TUNISIA

Algiers

ALGERIA

MOROCCO

Isean is soaring. Wing on wing, snowy white against Jurassic skies. Cliffs packed with relics, traces and tracks, fossils and footprints. Tiny dinosaurs glide on gale-force winds. A sky full of birds. They angle just so, feathers flattened to the gusts. Ascending updraughts, riding currents. Brilliant and bright, the time of their lives. The wind is rushing, the gulls are screaming. A raucous gathering in a storm. I’m flying too, eyes wide, heart lifting, breathing it in. All that air. There’s no one here to break the spell, to crash this party. No one to stop us.

We’re above and apart. Up with the birds. I’ve never known this kind of release, this boundless joy. A sense that I’ve found it, the untold story, about happiness and freedom, and life really giving. That it can be simple. I found something. It was nothing. An absence of something. A yawning empty horizon. No rules or restraints. No one with their better way of how to go. The only way my own. The freedom of that. It rushes and lifts and just overruns you. To belong, unfathomably, right here, in this wild place. We climb higher, we dip lower, we lean with the breeze, judging the gusts. The wind force builds and bends the bluff. Isean responds with grace and with calm, steady she goes. As with the birds, their breastbones like keels, she is made to glide. On the wind, through the waves. Her sails flattened, her hull carving white horses. As joyful as me. We are sailing.

A quarter of a mile off in a collision of cliffs and sea, there’s a raging line of surf. The English Channel churning powerfully, bright foaming crests like teeth untethered, tumbling over sea green. A confused mess of steep waves. I stare in sudden and

quiet horror, scan the horizon from the headland out to sea, searching without luck for a break in the frothing line. St Alban’s tidal race, turbulent overfalls stretching as far as the eye can see. Some fifteen miles on the other side of this barrier lies sandy Weymouth, our destination. Now it feels like a distant dream, approachable as Atlantis. The joy, the freedom, the sense of belonging – gone. What in the world am I doing? I don’t know. I don’t remotely belong here. I don’t know what to do. My friend Saoirse is with me, in her early twenties, on her third ever sail. I’m calm on the surface, like a swan on a lake, feet kicking below. Nerves building, I consider our options. We could turn around, but with the tide against us, we won’t make it back to Poole before nightfall, a place of narrow channels and grounding sandbanks I’d rather not navigate in the dark.

‘It’s going to get rough,’ I say. ‘Hand on the boat at all times.’

My stomach is lurching, my heart thuds as the building swell pummels Isean ’s hull. We are going into the tidal race.

The better choices were the ones I had failed to make. I should have timed our westbound arrival to coincide with high tide at Dover, when the water calms a little here. I could divert four miles to sea and bypass the race, or head inland, weaving round the rocks on the inner passage that runs more gently, but a nerve-wracking fifty metres offshore. If anything goes wrong – snagging a lobster pot, losing steering – you’re right on the rocks. It calls for calm conditions and a confident skipper; we have gale-force winds gusting against the tide . . . and me. In any case, I don’t know these options. In my jaunts day-sailing along the south coast, I had remained blissfully – shamefully – unaware of tidal races. Now, I would be relying on beginner’s luck and my small, sturdy boat to get us through this, the most sobering sailing lesson I’ve ever had.

I had set off west in a kind of madness weeks earlier. Friends had casually mentioned plans for a week’s sailing out of Brixham

and I made it a mission to join them. I dreamed of sky and sea. A disquiet had been forming; life in the city had become oppressive and I needed air. It was a realisation that came gradually, then rushed all at once, overnight, like a dawn chorus rousing me out of a stupor. I responded, ran south, exited the stifling city in a flood of instinct, seeking the salt and space, the silver and blue of a shape-shifting sea. I had always loved the water but hadn’t sailed until my thirties. I was an amateur with a day-skipper qualification, and I longed to put my knowledge of theoretical navigation into practice, plan proper passages, try anchoring – all the things real sailors do. Suddenly, with the prospect of joining my friends in Brixham, I envisaged myself doing so under the guidance of experienced sailors in idyllic Devon bays. In my excitement, I’d glossed over the details of how I’d get there. I lacked experience, I failed to plan, but I did have an excellent little boat. It was my ex-boyfriend Phil who found Isean in our last year together. She’d been languishing in a boatyard on the west coast of Scotland for years – a real project. But what beautiful lines! A Nicholson 26, a long keel, a true classic. I made all the mistakes everyone makes when they fall in love with a boat – the first, technically, was buying her. At a fraction of the cost of most second-hand cars, she seemed cheap in the misleading way boats do to a novice. She was a mess outside and a shell inside: there were thousands to spend. But what a feeling to rescue such a beautiful boat from ruin – worth more than money. And now she’s kin.

She came to Brighton on the back of a truck. That featureless strip of channel between Shoreham and Seaford made for safe learning – lots of space and depth, not much to hit. If there were too many white horses at sea we wouldn’t venture out, happy to enjoy the boat on her mooring. But I’d wistfully watch sailing boats arrive, salt-crusted sails dropping on the way in, decks glistening with sea spray, crew spilling out in all

their gear – rosy-faced, healthily tousled – all big grins, heading for well-earned showers and dinner. And off they’d go in the morning, on their way out to sea again, their boats doing what boats are meant to do. I began to look at Isean differently. She seemed subdued, this seaworthy boat, her potential wasted on our modest day sails. She was capable of so much more and I was desperate to sail her as she should be sailed.

On New Year’s Eve 2014, I made my only resolution. I would learn to sail my little boat. I spent the first months of 2015 revising navigation, and on a misty April morning, I set off with Phil, by now a dear friend. We were bound west, for somewhere more challenging. ‘If you can sail in the Solent,’ people had said, ‘you can sail anywhere.’ By Easter, with help, we were there. I had expected a busy stretch of water but was still taken aback at the volume of marine traffic and the impressive number of hazards. Sailing around this ship-filled strait was an exercise in concentration, the horizon intermittently blotted out by one giant or another. Cruise ships like gleaming cities floating past, tiny balconies with matchstick figures piled up into the air. Stern steel navy ships under way. Lego-like cargo ships, stacked high with coloured containers. Sunday racers and romantic old tall ships, sails crowding blue skies like a Glasgow tenement laundry day. There were the tankers, tugs and trawlers, tour boats, ferries and hovercraft, speeding in and out of Portsmouth and Southampton. And a multitude of invisible obstacles – man-made defence walls running undersea like piratical freight trains, and natural barriers such as the Brambles, a lumbering sandbank slowly edging west. But these were nothing compared to the Solent’s strongest force – a help or a hindrance, depending on what you’re doing. It’s tides that are king here, rushing between the Isle of Wight and the mainland with the strong winds that also funnel through. The tides dictate your movements above all else; you need to carefully time your passages

with, not against them, especially with a small engine that can’t compete with their power. There’s the unique phenomenon of a double high water too. Great if you love tides! Hurray, more tides!

I was never a stickler for rules in life. ‘You always have to try an unlocked door,’ Phil would sigh as I blithely ignored ‘no entry’ signs or dragged him around abandoned places in the middle of nowhere. At sea, where rules mattered, I converted fast. The collision regulations I’d struggled to memorise took on real and urgent meaning. When learning, I’d cursed the finicky detail of different buoys and beacons, colours and light sequences; now I was filled with admiration for the systems that made such practical sense at sea. I’d find myself in the dark, squinting at flashes, wondering when ‘quick’ becomes ‘very quick’ . . . or wait, is that ‘continuous’? I’d test myself on flags and candy-striped red-and-white safety marks. I was the world’s happiest swot on the most educational fairground ride ever. I got used to the proximity of other boats, learned how fast ships advanced and where to be in relation to them; when to hold my nerve and when to shift. I learned to think much farther ahead after sailing with my friend Gary Bettesworth, a professional skipper I would call upon several times over the years. ‘It would be prudent to tack,’ he’d say, anticipating the movements of others. Prudent became my guiding principle. If I wasn’t sure – or a bit lazy – about the necessity of moving, I’d decide it would be prudent, then do it, beaming like a head girl at Sea Cadets. I took it all in, made my mistakes; after a season, I started to feel reasonably competent.

Sailing came late but boats had always been in my peripheral vision, quietly working their way into my dreams. There was an old wooden hull in our garden when I was tiny; a hulking great thing, it seemed to me. A place to run when Billy, our hissy gander, chased me, his epic wings flapping, long neck snaking as my

little feet clambered the ladder to safety. I grew up in Dumbarton, a town of geese-guarded distilleries with a rich maritime heritage. A place forever bound with ships and whisky bottles. It was home to one of the most beautiful boats in the world today – the Cutty Sark, built on the River Leven in 1869; the fastest tea clipper of her time. She’s now in Greenwich, her copper hull gleaming like gold behind glass. In a half bottle, she flies through London air. A few miles upriver from Dumbarton, in the shipyards of Clydebank, Edgar, my grandfather on my dad’s side, was one of those hand-riveting the Waverley in the 1940s. In his heavy moleskin trousers, cotton in his ears – no safety gear back then. His work must have been sound. That beautiful little ship now claims to be the world’s last paddle steamer to take passengers to sea.

My dad lives in Dunoon now, a town to the west, where the Clyde opens out and pushes south towards the isles of Bute, Arran and the Irish Sea. My parents moved there twenty years ago, the last of a series of flits orchestrated by my mum. She was a gypsy at heart, would have loved to travel, but raising three kids – Stephen and David and me – filled a couple of decades. She and my dad considered a move to Spain when I was a teenager, but she wouldn’t leave her own mother, Maw Joss, a regular fixture in the calendar of family life. Instead, she got her nomadic fix dreaming outside estate agent windows, always an eye on a new location. She got a buzz from moving home, shifting my dad from place to place; a small profit on each wreck he renovated bought something better. In the nineties they moved briefly to Ireland, but she missed family. I’d left Dumbarton for London at nineteen, happy to visit my parents in Galway or Glasgow, but my brothers lived in Scotland, and by the time I’d finally got myself off to the University of Sussex at twentyfour, my parents had returned to a house right on the banks of Loch Long in Arrochar.

There were special times together in those years. I’d be home for key moments, for Hogmanays when Stephen’s folk band, Shenanigan, incited boisterous gatherings under Scottish night skies that hardly knew how to get dark, a fast and furious blur of music and laughter that petered out to the birdsong of dawn. Stephen was always in the middle of it, head tilted above his accordion, his features knitted in musical concentration. I mostly remember my mum’s face in the early hours, sober and smiling, good-natured and gently steering us all off to bed. Stephen and my dad had a little motorboat and they’d take it around the lochs, Stephen diving for shellfish on a safety line. I remember his stories, delivered with goodnatured exasperation, of how he’d be poised on the seabed, clutches of gleaming mussels just within grasp, when suddenly he’d be hoicked up, his fingers stretching impotently as my dad reeled him back to the surface.

What we couldn’t have known was how limited our time together would be. Shortly after my parents returned to Scotland, we lost Stephen. Suddenly, violently, my eldest brother was gone. A car crash ended his life at thirty-two. I was just finishing my first-year exams, the whole summer ahead. My dad called, his voice cracking on the phone. I recall a numb journey to a house suffocating in the first wave of grief, my nights spent on the shores of Loch Long with a bottle of whisky, talking to the sky, where I thought Stephen might be. Relatives and friends came and went, love and kindness carried in the pots of food, rounds of tea, hot toddies nursed. There were shared stunned silences, sleepless nights spent in tears and conversation, laughter and stories. Stephen was present – in his rightful place at the centre of the gathering, but inexplicably in the past, no longer bringing the room to life with that astute wit, with the music, energy – craic – that drew others to him like moths to a candle. I was afraid of the silence; with Stephen’s music and his articulate

din suddenly gone, the family was fractured. I felt inadequate, quiet, dull. I had no idea how we would fill that vacuum – as if anyone wanted a replacement.

The grief eclipsed everything except my parents’ agony, the enormity of it cutting through even my own pain. My dad was lost in something unfathomable, seemed bewildered by the depth of his suffering. My mum almost died. For a moment in those first days, she turned to the wall. I remember it clearly. I didn’t know back then that her resources were already depleted; that, privately and quietly, she was facing her own mortality, the brutal matter of breast cancer. Her stoicism kept this from us for many years. A heavy weight for her and my dad to carry. I wish I’d had the chance to offer support but she wanted to protect us. It was probably a form of protection for her too, to cope in private. Most of all I think it was a kind of optimistic ‘screw you’ – a determination that her life should continue as normal, that she would not be cast as a victim. When Stephen died, though, she wanted to go too. She held on, for us; took the harder path, in surviving. Her firstborn child. I remember stories of Stephen as a little boy, my mum absent-mindedly wandering off, another kid hanging on to her. ‘You’ve got the wrong boy’s hand,’ he’d cried. ‘So special,’ she told me. In those first days, she articulated the immensity of her grief in a few devastating words. ‘So special, your first child.’ After that, she would always walk out and look over the water before she went to bed, saying goodnight to her boy.

Dunoon was the last place my mum lived, the last place she brought my dad, the place I said goodbye to her, the place I go to him now. In the summer, the Waverley is often there; seventyfive years on, inevitable as the tides, this little ship coming and going. I swim there when I return, seeking solace in the cold water, porpoises rolling, cormorants circling, each stroke pulling me to the Gantocks lighthouse where the steamer paddles

and the seals sing. Through rain and sunshine I go, and best of all, through shifting mist. In the fog, I’d hear the boat before I saw her, the puffs of steam; a wet sound, like the seals snorting, the beating of her giant paddle wheels. A gentle rhythm from a bygone age, the sound of home and kin, of belonging; a sound that, like the muffled call of foghorns on the coast, clings to the landscape and belongs to its people.

Gradually, her lines take shape out of the haze; the elegant curves, the warm timber. Even on the bleakest of days, through rain, through your own tears, you can’t see this boat without smiling. And I saw her, this old friend, on the south coast of England. A good omen, just off Christchurch, and just before my journey west. She was chugging cheerfully along. My heart lifted in recognition. So touching to sail with her here, everything shifting yet solid and familiar. The past and present colliding, home and family connected; the world made smaller, manageable – navigable. I wonder what Edgar would have made of these, my first steps on the water. I didn’t really get to know him, this man’s man. He died while I was young and before that, I was too scared to talk to him. He loved weans, I’m told, but I was timid and he seemed as tough as the white- hot rivets he once hammered into place. I expect he would have been startled at the sight of two women on a little boat in that big sea off St Alban’s Head. I can imagine his furrowed brow, chin jutting in justified concern at my lack of experience too. I shouldn’t have been there – of course I shouldn’t. I’d been driven on that journey west by a determination that bordered on obsessive. What had started as a loose plan suddenly ignited, in a direct reaction to Brexit.

I was in a marina near Deptford for the referendum, on another old boat that was my home. I had that rarest of London things, a close-knit community around me. Saoirse had moved onto a neighbouring boat the previous winter. I remember her

arrival – a big grin in a woolly hat, always on her bike, her voice blasting across the dock like a foghorn. She was bright, funny, almost half my age, with a teenage vernacular that belied great maturity. ‘It is indeed “sick”,’ I’d nod at her enthusiasm for skateboarding or the Shambala Festival. In turn, she laughed at my teenage tendencies, my focus firmly on fun while most women my age were deep in kids. We fast became friends, the two of us single, enthusing about boats and the sea. Life was good in our microcosm, but the surrounding atmosphere had been tense for weeks: families, colleagues and friends all on one side of the vote or the other. It had been strange to witness the evolution of the referendum, a Pandora’s jar for Little Britain. This dry constitutional matter wouldn’t interest the general public, the thinking seemed to go, even as the monster took shape before our eyes. In no time it dominated everything, a highly charged debate about identity that unleashed so much anger and emotion it often defied rational discussion. The leadup to the vote saw PR stunts and headline-grabbing claims paraded on buses and boats, from the infamous ‘£350 million for the NHS ’ slogan to the mad spectacle of a Leave and Remain flotilla trading insults via megaphones on the Thames. I missed Stephen at times like this. He would have laughed at the insanity of the political circus, but he would also have been doing something constructive.

He’d completed his law degree just before he died, intending to specialise in human rights. His finest skill was one I lack – where I take time to gather my thoughts, Stephen was fast-thinking, an articulate and persuasive speaker. He wore his knowledge lightly and had a rare ability to reach out to others, taking on opposing views with a warmth that charmed and disarmed. He was maddening at times, in the way that he’d see straight to the core of you, to the weak link in your chain. But he did it with empathy, with knowing humour, offering himself up to ridicule,

so you’d end up laughing, closer than ever. This easy approach was something many of us seemed to lack at a time it was badly needed. I was deeply frustrated at my own verbal paralysis as I watched everything unfold with a Munchian scream sliding down my face.

We seemed to retreat further into tribes. For once, media reports of a country divided were not hyperbole. On 16 June we were confronted with Nigel Farage’s anti-migrant poster: ‘take back control of our borders’ across a mass of black and brown faces, the words ‘breaking point ’ screaming in red capitals. A few hours later, the country reeled in horror at news of the brutal murder of Jo Cox at the hands of a far-right terrorist. Cox was a Labour MP, best known for her humanitarian work, for campaigns on loneliness and immigrant rights. She also supported remaining in the EU . It happened on the twentieth anniversary of Stephen’s death. I always say dates don’t affect me but evidence suggests otherwise. In my twenties I temporarily lost my licence for driving drunk on what would have been Stephen’s birthday. In my forties, ten years on from my mum’s death, I sobbed as an osteopath eased the tension my back was holding so tightly. It is often my shallow breathing that reminds me what time of year it is. Our bodies retain memories. Grief finds a way to assert itself. And when you’re already depleted, your capacity for dealing with the hard stuff of life is diminished. Raw with feeling in that bleak week, I read of Jo, a mother who lived with her young family on a boat on the Thames. I listened to the mournful sound of ships’ foghorns just two miles upriver, a collective wail of pain and grief, sounded by those in her community – an extended family, I imagined. The shock of it all silenced the terrible racket for a short time. Everything felt fractured.

After voting to remain, I was up early with a sense of foreboding, watching rolling reports as news of Brexit broke.

The significance of the result was palpable. Saoirse messaged, despondent, from her boat. We’d been in the habit of taking our kayaks out before work. I switched off the television, paddled out to the middle of the dock, where we sat in companionable silence, absorbing it all. From a barge, a neighbour called out, ‘The prime minister’s resigned.’ It was not yet 9 a.m. Back on board, I dressed for work at the Guardian newspaper as anger and dismay poured out online from like-minded friends and colleagues. I knew what the office would be like, the atmosphere heavy and glum. My job – concerned with food features – would be entirely pointless. And it was a Friday. With a sudden and selfish certainty, I made a decision that was at once irresponsible and unprofessional. I sent Saoirse one word: ‘Sailing’. Then we were on a train heading south to Isean. By the afternoon we were at sea, outside Gosport in twenty-five knots of wind, beginning the journey that carried us to that tidal race. I fought the halyard – the line that lifts the mainsail – which had whipped itself into a tangle round the mast as Saoirse learned – fast – how to steer. We headed up the River Hamble and that evening we crashed noisily through the pub doors of the Jolly Sailor. Overhearing conversations, we remembered Brexit had happened – this momentous thing that had dominated for so long had been blown out of our minds. We had been caught up in the sea, the stinging wind, the heeling boat, laughing and shouting with rope-whipped hands; the physical and mental exertion and the exhilaration. The sheer joy of it. That morning now felt a world away. I didn’t know it then, but 24 June 2016 was the day that my life completely changed direction. Stephen would have cheered.

Over the next few weekends I dragged various people aboard to help me west. Phil joined from Beaulieu to Poole on a fine July day with sparkling blue seas. We passed Hurst Point, looking south as the Isle of Wight’s westernmost point hove into

view. Out there, the Needles, that ragged row of incisors gleaming white and harking to the west. Drama in spades, but what struck me more than the atmospheric scenery was the space, a world apart from the busy Solent; an alternate universe to London. Ahead, a vast and glorious expanse of empty water. No other boats in sight. I felt my shoulders drop. With the leeway around the boat, there was now room in my mind – clear, quiet, calm. And conditions were perfect. The sun was shining, a few fluffy clouds were bumped along by the gentle breeze that also pushed us west. I went below deck, glanced at the charts, unhurriedly made lunch, staring out at the glassy water we glided through – a peace I’d forgotten. By the time we arrived at Poole, my feet trailed in the water, like the Brighton days, but I was now marvelling at a rolling Dorset landscape that felt so well earned. It was brilliant – all stress gone. A week later Saoirse and I were at St Alban’s Ledge.

It’s messy, intimidating but doable, I decide. I’m apprehensive but not scared – I know my boat is solid. I trust her. I start the engine for extra power and control. Off we go, into the roaring race, and then it’s too late to change my mind; it’s a case of staying calm and holding on. I’m helming as best I can through steep, heavy waves. Normally, at five tons, Isean cuts easily through rough water. Now, she’s pointing up, bow to sky, then bellyflopping into troughs that feel like chasms in the sea. I have a feeling of weightlessness, my stomach lurching on the drop. The noise of it! How can water feel this solid? Waves are rushing the gunwales, but my worst fear – swamping the cockpit – doesn’t materialise. Saoirse is standing beside me, holding on, facing forward. I’m feeling irresponsible for putting her in this situation. But she’s fine as long as I’m fine. And I’m fine as long as the boat’s fine. Which it is. In fact, both Saoirse and Isean look like they’re having the time of their lives. I’m having a private ordeal. There is a huge wave coming now.