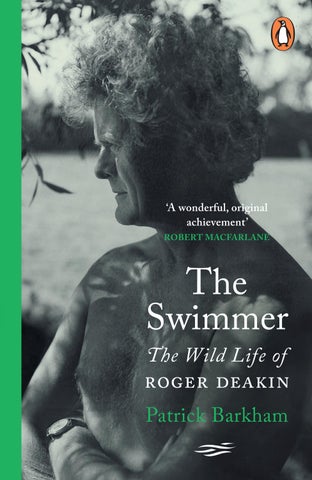

‘A wonderful, original achievement’

ROBERT MACFARLANE

ROBERT MACFARLANE

ROBERT MACFARLANE

ROBERT MACFARLANE

‘Reading Patrick Barkham’s brilliant biography of this fascinating man, I felt both that I was meeting again the Roger Deakin I knew – and also encountering a Roger I never met. The Swimmer is a wonderful, original achievement; teeming with stories, glittering with images and experimental in form and tone. The narrative form Patrick has chosen allows Roger’s own voice to sing through and with Patrick’s – and also introduces us to a chorus of voices, memories and perspectives of those who knew Roger over the course of his wild and various life’

Robert Macfarlane‘Barkham conjures the life of the wild swimming champion and author of Waterlog in a bravura act of creative memoir . . . a rich, strange and compelling work of creative memoir that beautifully honours and elevates the life and work of its subject’ Observer

‘A remarkable book . . . The Swimmer is an unconventional biography of an unconventional person . . . A tapestry-like life of the influential nature writer’ Guardian

‘Barkham’s book succeeds in evoking a fascinating, creative, complicated man’ Times Literary Supplement

‘Despite having published just one book during his lifetime – the instant classic, Waterlog – Deakin has become the unofficial patron saint of wild swimmers and his posthumous Wildwood inspired many of today’s nature writers. Barkham mines Deakin’s notebooks and interviews his family, friends and lovers to create this beautifully immersive biography’ Financial Times

‘The voice is rich and authentic – just like Deakin’s . . . What The Swimmer grasps is that Deakin was an extraordinary man in an extraordinary moment’ The Times

‘Vivid . . a magical kind of post-mortem autobiography . The Swimmer is a wonderful testament to a unique and very charming man’ Daily Mail

‘A long-awaited biography of the late, great writer, environmentalist and moat-dipper . . . This is a mightily accomplished biography . . . a skilful piece of theatre’ Caught by the River

Patrick Barkham is an award-winning author and natural history writer for the Guardian. His books include The Butterfly Isles, Badgerlands, Islander and Wild Child. He is President of Norfolk Wildlife Trust and lives in Norfolk with his family.

Also by Patrick Barkham

The Butterfly Isles

Badgerlands

Coastlines

Islander

Wild Child

The Wild Isles (editor)

Wild Green Wonders (collected journalism)

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Hamish Hamilton 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Patrick Barkham, 2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–47148–7

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

For Roger’s friends, who came up ‘like weeds, spontaneous and unstoppable’

Life is not a walk across an open field.

Ken Worpole, friend of Roger, citing a consolatory Russian proverb

Try and see life steadily and see it whole. That’s what one of our schoolmasters would say to us.

Ben Barker-Benfield, schoolfriend of Roger

a brief chronology

Introducing some of Roger’s friends and relations (see back pages for full index of people)

1940s

11 February 1943 Roger Stuart Deakin born in Watford to Gwen and Alvan Deakin. They are thirty-four and he is their first and only child. He grows up in a two-bedroom semi-detached bungalow in Hatch End, an outer suburb of London.

1950s

September 1953 Roger wins a ‘direct grant’ paid by his local council so he can attend Haberdashers’ Aske’s Hampstead School. Here he meets lifelong friends Tony Axon and Tony Weston, who later, with his wife, Bundle Weston, inspires Roger’s purchase and restoration of Walnut Tree Farm.

1960s

October 1960 Roger is following the trial of D. H. Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the newspapers when his father, Alvan, dies suddenly of heart failure on the London Underground. He is fifty-one.

1961 Roger obtains a place to study English at Peterhouse College, Cambridge. In his final year, he becomes friends with Dudley Young, who later takes an academic post at the University of Essex. Roger looks up to him but Dudley divides opinion among his friends; the pair eventually fall out over Waterlog.

1964 Roger graduates from Cambridge and moves to London, renting a ramshackle flat in Bayswater. His first job in advertising is with Colman, Prentice and Varley but he also buys and sells furniture on the Portobello Road. He becomes friends with flatmate Tony Barrell, a great wit and rebel, who later moves to Australia.

1967 Takes a copywriting job with Leo Burnett, buys a Morgan sports car and falls in love with Margot Waddell, a friend of Dudley in Cambridge. Roger is turned down by Margot but she becomes a trusted friend and confidante.

1968 Meets Jenny Kember née Hind; they marry in 1973 and their son, Rufus Deakin, is born in 1974. The couple separate in 1977.

1969 House-hunting with Jenny in Suffolk, they find the ruin that becomes Walnut Tree Farm in the village of Mellis.

1970s

1970 Buys Walnut Tree Farm for £2,000; soon after acquires four fields: a total of twelve acres. Begins restoring the old farm, helped by friends and local builders.

1972 Appointed creative director of Interlink advertising agency; commutes between London and Suffolk.

1974–75 Affair with Jo Southon, a colleague at Interlink.

1975 Takes a position teaching English at Diss Grammar School.

1978 Leaves Diss Grammar and becomes a freelance consultant for Friends of the Earth, working on campaigns including Save the Whale!

1980s

1980 Meets Serena Inskip who becomes his partner until 1990. In 1981, she moves into Walnut Tree Farm with Roger.

1982 Co-founds the charity Common Ground with Angela King and Sue Clifford

1982–83 Promoter for Aldeburgh Festival, successfully bringing rock, pop and folk concerts to Suffolk, including American star Carole King.

1990s

1990 Works on A Beetle Called Derek, an ITV series for young people about the environment.

1990 Splits from Serena and gets together with his old friend Margot, now an influential psychotherapist at the Tavistock Centre in London.

1991–95 Makes ITV documentaries covering subjects including allotments, the Southend rock-music scene and glass houses.

1995 Separates from Margot. Comes up with an idea for ‘The Swimming Book’.

1996 Signs a contract to write ‘The Swimming Book’ – later Waterlog – for Chatto.

1997 Roger’s mum, Gwen Deakin, dies on 17 August aged eighty-eight.

1997–98 Relationship with the composer Errollyn Wallen. Important male friends alongside his lifelong school ‘chums’ in the latter part of Roger’s life include the writer Terence Blacker, art director Gary Rowland, and film production designer Andrew Sanders.

1999 Waterlog is published.

2000s

2000–01 Relationship with Annette Kobak, biographer, broadcaster, writer and painter.

2001 Signs a deal to write ‘Touching Wood’ for Hamish Hamilton, which is published in 2007 as Wildwood.

2001–04 Travels widely to research Wildwood, including trips to Australia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine.

2002–06 Relationship with Alison Hastie, Roger’s partner until his death.

2003 Becomes friends with the writer and academic Robert Macfarlane, who later accepts Roger’s request to be his literary executor.

2006 Diagnosed with a brain tumour in April. Roger dies at home, at Walnut Tree Farm, on 19 August. He is sixty-three.

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water

The final lines on the grave of John Keats

The wellspring of Roger Deakin’s life can be found in a small village scattered on the arable plains of north Suffolk. A bumpy track parts a common where the grass ripples like an inland lake in midsummer. At its end, hidden by a thicket of sallow and ash, is a low, old house made of oak from the woods and clay from the ground. Beyond is a patchwork of small meadows, dancing with butterflies and thickly hedged by blackthorn, hawthorn and bramble. Field edges are decorated with unexpected items: a disused railway wagon, a decrepit green truck, a shepherd’s hut like a little chapel. Several abandoned cars appear to float in a sea of grass.

If, in the early years of this century, you stumbled upon Walnut Tree Farm, you might find Roger bent over a battered desk in the shepherd’s hut, writing; or tinkering with the mechanics of an ancient grey tractor in the barn; or stoking a bonfire in the meadow; or wallowing in a claw-footed cast-iron bath set in open air on the sunny south side of the house. If you came on a summer’s day, you might encounter only green silence, broken by the splash of the swimmer in the ‘moat’ hidden behind a curtain of hazel and rosebay willowherb. Shaded by a tall willow at one end and a field maple at the other, this linear pond, thirty-three yards long, five yards wide and nine feet deep, was the starting point for the swimming journey that made Roger’s name. Springfed, its water was soft and sweet. Newts hung among the duckweed that trailed like tiny stars into the depths as the swimmer stroked his way from one end to the other.

Sliding into this cool green water was a kind of shamanism for Roger. It gave him a frog’s-eye view of the world, which entranced readers of his first book, Waterlog. Here he swam out from his moat and around Britain, not along its coastline but really in it, via rivers and streams, lakes, lagoons and lidos; beauty spots, secret spots, forbidden places.

It was an obscure idea, written for a modest advance, by a first-time author who was in his fifties, but Waterlog took off when it was published in 1999. This travel adventure, social history and memoir was so attentive to plants, animals and place that it became part of the burgeoning genre of nature writing. Readers loved seeing the British countryside in a completely new way, and they loved their guide – a funny, enthusiastic, plucky and poetic hero who wooed us with his stories.

Over time, Waterlog ’s influence percolated many parts of society. Most prosaically, it frog-kicked a revival in open-water ‘wild’ swimming in Britain. Outdoor swimming clubs were reinvigorated. The physical and mental benefits of cold water that Roger explored – the ‘endolphins’ – were widely

discussed in the media and further researched by scientists. Books, TV programmes, websites and swimwear manufacturers dived in, while Roger’s reputation grew as he entertained crowds at the emerging network of literary festivals in the early 2000s.

And yet Roger never published another book in his lifetime. Barely seven years after Waterlog swam into the world, he was dead. For most of those years, he laboured on an ambitious book about humanity’s relationship with trees and wood; Wildwood could only be brought into being in 2007, a year after he died. It was followed by another posthumous book, Notes from Walnut Tree Farm, a collection of beautiful observations drawn from his copious notebooks. The precision of his gaze and the metaphoric dazzle of his writing ensured his status grew in the years after his death when he was championed by fellow writers including his friends Robert Macfarlane and Richard Mabey. Roger came to be feted as a writerly sage and an original thinker, a kind of green god, and yet he was much more elusive and interesting.

Writing was one channel that flowed in a braided life. All generations are fascinating but Roger was one of the most compelling members of perhaps the most distinctive generation that ever lived. You will meet many more of them in these pages. The older members of this generation suffered the misfortune to be born in the midst of a war but by the time they were children there was peace, rebuilding, and eventually an economic boom. Those born in the early 1940s, such as Roger, avoided National Service by a few months and entered adulthood just as sex was invented – between the Lady Chatterley trial and the Beatles’ first LP. As Roger himself observed in the sixties, there grew a ‘complete chasm’ between his generation and his parents’. Never before, and I think never since, has there been such a gulf between one generation and the next. Roger was in the vanguard of a cultural, social and psychological revolution as he and his peers cast off traditional tastes and mores, from notions of duty to a short back and sides. Looking back, this seems easy. His generation were given great gifts – a welfare state, social mobility, plentiful jobs, cheap property and accessible global travel – but they made the most of their opportunities. And their renunciation of decades of ossified ways of being did not come easily; it had to be conceived and struggled into existence. Roger and his friends committed to a lifetime of challenge, exploration and change. Some, in their eighties now, are still adventuring and protesting.

Many new ways of doing things that they forged have become commonplace in contemporary life. Roger cast off the conventions of suburbia, the nuclear

family and the nine-to-five. He curated his own ‘family’, a circle of ‘chums’. He was a freelancer with a portfolio career long before such working patterns were widespread and an environmentalist before the word was minted. Alongside such firsts are lasts. He was among the last of an age which is lost to us today – when a child could roam far from home and form their own intimate bonds with animals, plants and places; when life could be improvised and when generalists ruled; when an adult with a certain level of education and a socially acceptable skin colour seemed free to turn their hand to almost anything, without any training, or talk their way in anywhere.

Roger’s career riffles like a wild river, full of unexpected meanders as improbable dreams become reality. As a child, he developed a profound curiosity about wild life, wild places and people, wondering how they lived and what was on their mind. He brimmed with enthusiasm for so many things. As a young man, he became an advertising executive in swinging Soho in 1964 but (implausibly) claimed he earned more money buying and selling furniture – recycling and upselling stripped pine – on the Portobello Road. As the sixties ended, he dropped out and headed to the country, raised goats and raised his own house. After restoring this timbered ruin, he became an English teacher. Later he morphed into an environmental activist, playing a key role in the Save the Whale! campaign. In 1982, he co-founded a prescient new charity, Common Ground, which championed ‘ordinary’ countryside – hedgerows, verges, orchards – via artistic happenings. Somehow, he also found the time to become an impresario, putting on small gigs and then major concerts. Later, he took up film-making, writing, directing and producing some elegiac stories of everything from allotment life to end-of-the-pier shows. Finally, in writing books, he found a single but constantly changing line of work that seemed a perfect fit for his temperament and desires.

These are his career facts but Roger springs to life via incidents such as: in childhood, he made money by collecting and selling bulrushes; as a teenager, he customised his friend’s lifeguard badge to gain the plum summer job of lifeguarding at a local pool without any qualifications; as an adult, he kept newly hatched chicks in the basement of his ad agency; travelling home, he talked a train driver into slowing down the London to Norwich express so he could jump on to the footpath beside his house rather than proceed, like an ordinary passenger, to the station five miles to the north.

Roger embodied an age of freedom and rebellion but such declarations give solidity to a life that shimmered with constant movement. Jobs, schemes and relationships came and went but the magical kingdom he created at

Walnut Tree Farm was always there. Like the lines Roger admired by the poet John Donne, the farm and its fields were the fixed foot of a compass while he was the foot that moved around it. ‘Thy firmness makes my circle just, / And makes me end, where I begun.’ The farm, he declared in a letter to a friend in the 1970s, is ‘so much a product of my imagination, that I feel complete there as nowhere else. Indeed the more I’m there the more of myself I leave there when I go away, so I feel less and less me when I go away.’ And yet he continued to leave his place in Suffolk, restlessly travelling, adventuring, seeking.

‘Complicated’ is one of his friends’ favourite adjectives for him. Roger was gregarious and he needed to be alone; a countryman who cleaved to the city; a passionate environmentalist who adored fast cars; defiantly modern and worshipping the past; a lover of peace and a loser of his temper. As one partner put it, Roger possessed a compulsion to jump boundaries. Enigmatic, amphibious, watery: whatever he did, slipping through life, the Swimmer was determined to resist the anchor, the mooring, the still water – and the deeps.

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. Roger noted down the lines on the gravestone of John Keats when he visited the Romantic poet’s resting place in the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome in 1982. Roger’s transcription is, literally, watery – his notebook ink blotted by a summer rainstorm. I came to realise the truth of this epitaph for Roger too after I wrote 90,000 words of conventional biography and found they ill-served the fluid spirit of an unconventional man. My first draft had a definitiveness that Roger eschewed. I wanted to shrug off judgements and labels. Besides, Roger wrote more beautifully about his life than I could. So I made him the lead narrator.

Roger was a writer long before he became a published author. His nineyear-old self wrote about his travels. His twenty-five-year-old self penned advertising copy. His fifty-year-old self wrote television documentary scripts for a living. All the while, he scrawled marvellous letters to entertain his friends. And his notebooks were the siblings he never had, to whom he confided his feelings and impressed with stories.

I began mining the shards of memoir he dropped into these notebooks and letters, jottings and journalism, and put them together into a life story that felt true to him. The structure is mine – Roger didn’t really do structure – but each story and its style are his. Roger usually wrote many drafts of the same tale and I’ve tried to create the best version, which wasn’t always the last one. I’ve

excavated fragments of memoir that were deemed superfluous to the final version of a book or a feature story but are relevant here. For instance, the original draft of a magazine story he wrote about ice-skating contained vivid childhood memories which were cut from the published version. Throughout, I’ve added moments of narration, a little extra research and a few factual details in Roger’s voice but I have never invented scenes or introduced feelings that he did not express.

To give you an example of my method, one of my favourite Roger stories is the time he was dispatched to Venice to write some advertising copy for the Royal Navy in the summer of ’69. This tale opens Chapter 5 and the first paragraph, which sets the scene in a ‘biographical’ way, was written by me. But the genius of the story which unfolds was almost word-for-word typed up by Roger at the time in a letter to his friend Margot Waddell. He was entertaining and impressing her; the glorious descriptive writing, the pacing, the swearing, the comic scenes and the denouement are all his. I’ve slipped in a couple of extra details – for instance, ‘Bulwark ’s captain, known by the men as “TC ”, was reputedly famous for a “fastidious wit” ’ – which Roger might have added were he writing it up as autobiography. The two short paragraphs which conclude this episode by revealing the copy he produced and the fate of his advertising career are mine.

In the final three years of Roger’s life, his mind cast back more and more, and he filled his notebooks with vivid recollections from early childhood. He appears to have been inching towards a memoir but he never began one and so the opening chapter is a little more creative: I imagine how Roger might have started this book were he well enough to do so in 2006. Even here, many of the words are his, blended from drafts of Waterlog and transcriptions of voice recordings he made on a Dictaphone while driving between Suffolk and London. Later in this biography, when Roger’s life – and particularly his love life – is beset by cross-currents, I play it very straight, and only quote directly from what Roger wrote at the time or afterwards.

Throughout this biography, Roger’s enraptured view of his world is interspersed with the memories of his friends. Sometimes these are from their letters or published writing but mostly they are from many hours of conversation with me. Their testimonies provide multiple interpretations of the same events, and cast doubt on the idea of life as one simple flow. When the going is good, travelling between Roger’s writing and the recollections of his friends feels like a witty conversation. I can picture the warmth between him and his great friend Tony Axon as they trade comic stories of their

schooldays. But the exchanges between Roger’s viewpoint and those of his lovers provide a more nuanced duet, sometimes harmonious in its mutuality and occasionally discordant, furious or tragic.

My method is not flawless. If history is written by the victors, then survivors have the best opportunity to write biographical history. Roger’s partners have the final word on their relationships with him and he, of course, cannot respond. One person’s portrait of a past relationship, even in the calm distance of many years on, is likely to be coloured by the way it ended. Marrying Roger’s ecstatic ‘before’ to a lover’s cooler ‘after’ might create the impression that Roger was an impossible man, who was gifted glorious relationships and then threw them away. Was he? I can almost hear his protestations: ‘no, no, you misunderstand – it wasn’t like that at all’. Lacking his no-doubt-disarming defence, I hope you have enough evidence here to make up your own mind, if this kind of judgement is important to you.

Readers may ponder how I’ve presented clashing realities. I can only declare that I have tried feverishly hard to be honest and fair, to not load the dice or provide false balance in moments of controversy. Where there is conflict, I’ve only quoted people who have direct knowledge of a particular event. I’ve ignored hearsay. Critical voices have not been silenced but nor have they been amplified. If one person is quoted in these pages making a specific point, it has usually been raised by other unquoted people too. I’ve not included discredited views and I’ve not included information that I know to be wrong just to discredit someone.

*

I never met Roger Deakin, and it is strange to come to know him so intimately and not know him at all. We shared the same sky. I grew up in rural Norfolk and understand his love of nature and his experience of the uncompromising arable landscape of East Anglia. Even though I was born here, I know how Roger felt as an outsider in a region where farmers and landowners call the shots.

My parents belonged to Roger’s generation, and arrived in East Anglia shortly before he did, also buying land and keeping goats. My dad is a month older than Roger, while Roger’s son, Rufus, is a month older than me. Like Roger, my dad grew a mass of curly hair, rebelled against the stultifying mores of his parents’ generation, and became an environmentalist and an inspirational teacher. Surprisingly, given the small worlds that are environmentalism and East Anglia, they never met either.

Early on, I thought not having encountered Roger would bequeath me a crisp, clear and neutral gaze. What was I thinking? How can a dispassionate method well serve a passionate man? There’s a lovely line by Tom Stoppard: biography is the mesh through which real life escapes. Despite watching videos of Roger, listening to his voice and reading a million or so of his words, I came to crave his physical presence to engender that innate sympathy we feel for another living being.

As I learned more of Roger’s life, I became haunted by the possibility that we had passed each other in the street, or inhabited the same space at the same time. In the early 1990s, my dad moved to a cottage on Church Street in Eye, the small town three miles from Roger’s home. I regularly visited Dad there, little knowing that less than fifty yards up the street lived Roger’s mum, Gwen, whom Roger visited regularly at the same era. Roger also researched Waterlog in the University Library in Cambridge just when I was sat there too, swotting for my finals. When I moved to London in the late nineties, I hung out in the North London pubs and restaurants where Roger also arranged to meet friends. Researching this biography, I discovered he had read my Guardian journalism, a distant relative of mine worked with him and, most bizarrely, I bought my first home from one of his neighbours. I hoped a lost memory would pop into my head: suddenly, there was Roger, standing before me. It never arrived.

Finally, early in 2021, Roger materialised, wearing a dark green jumper, in one of my dreams. He was slightly hunched but then he stood up and straightened his shoulders and I saw that he was a formidable person. He was enthusing about something, and punched me lightly on the arm. I saw his energy, and how he took people with him; for the first time, I felt it.

Shortly before I decided to make Roger the narrator, he appeared again in my subconscious. This time, he travelled with me and my family on the train, disembarking at Diss. As the train stopped, he lingered in the carriage by the door and I saw that he was fragile and far more vulnerable than everyone realised. I opened the door for him and held his arm as he stumbled. As he departed, he asked: ‘Is there anything else I can help you with?’

I guess it was a leading question.

Can we rely on a great romantic to be an honest biographer of themselves? Can we rely on anyone to be an honest biographer of themselves? Am I the ghost or is Roger the ghost? After thirty months following in his wake, inhabiting his territory, residing in his mind, meeting him in my dreams, listening

to him and his friends, and interrogating many versions of his shared history, I’m still not sure.

Would Roger like ‘his’ biography? Honestly, I think his first reaction would be shock and probably outrage. Every little detail mattered to him. These are his words, but he would have put them together in another way. And my way isn’t his, no matter how hard I try. Perhaps, one night, I’ll be granted another five minutes with Roger in my dreams where I can explain. I will say, I’ve done my best to be true to you and to your friends who have lived, loved and sometimes suffered with you. Thank you for helping us see more of the world and its glory. Thank you for seeking freedom, for living so fully, for challenging those around you, and for being true to yourself. Thank you for your generation, who have parented my own and who continue to shape our world, for better and for worse, long after they have ceased sharing our skies.

Patrick Barkhamchapter 1

No one, least of all me, can evoke Rog better than he himself. Margot Waddell, memorial service address for Roger, 2007

What we have to decide is whether life is a little, cautious, grasping a air, or whether it is wonderful.

Roger Deakin, The Whale Declaration, 1979

It is early 2006, and Roger is distracted.

*

One day almost a decade ago, a summer storm fell on my moat. Water tumbled from the gutters as I shrugged o everything in the kitchen and ran out through the long wet grass. It was warm and somehow safe in the moat. I swam length after length – thirty yards of clear, green water – breaststroke, enjoying the clean incision of my out-thrust hands as if in prayer, out- ung arms as if in exultation. The frog’s-eye view of the rain on the water was magni cent. Rain calms water, it freshens it, and sinks all the oating pollen, dead bumblebees and other otsam. Each raindrop exploded in a momentary bouncing fountain that turned into bubbles and burst. The downpour intensied, and a haze rose o the water, as though the pond itself was rising to meet the lowering sky. Then the storm eased, and the pond was full of tiny dancers; water-sprites springing up like bright pins over the surface. All water was once rain. Swimming through all this I had the curious sensation of being dry, of having found the best shelter of all from the storm; a guest of the pond goddess.

That June deluge became the beginning of my book, Waterlog, in which I swam through the British Isles. One idea changed my life and it seems to have changed the lives of others, but for months it was simply one idea among a multitude. My brain felt like those pieces of litter blown about on the side of a motorway, scattered between Su olk and London and my too-frequent peregrinations. I was a freelance lm-maker in midlife, an environmentalist, and a creator of charities, campaigns, schemes and adventures. I had a base but no ties, at the end of a long love, with my son Rufus having reached adulthood and journeyed to Australia. I subsisted, as always, on ideas, which I recorded on a Dictaphone as I drove my ageing Citroën CX GTI , at speed, between homes and friends and meetings.

How about a lm about complaining called Moanin’? The London International Festival of Whistling on the South Bank? A documentary about the Norfolk freemasonry? A lm about Welsh male-voice choirs around the

world? A programme on the last pie and mash shops? A lm about lawns? Treehouses? What about that great unheralded workhorse of the garden, the wheelbarrow? A series of string-quartet concerts in swimming pools to replace ghastly piped ‘muzak’? A short story set in an allotment? Or Now Listen Here, a series about contemporary music that would ‘open wide the mind’s cage-door’, as Keats put it?

One idea, ‘The Swimming Book’, rose above the clamour. Various friends had long badgered me to write a book but there was always a more pressing diversion: a house, a renovation, a relationship, a hay-cut; an object, project, event or campaign. I was fty-three and I had always resisted the anchor or becoming becalmed in still waters. ‘The Swimming Book’ demanded to be written. But the act of swimming also turned me into a writer. What you need to write is energy, sexual potency and solitude. Swimming gave me plenty of all three.

I was never a champion swimmer but I have swum since I was a small boy, and usually outdoors. I schemed my way to a job as an unquali ed teenage lifeguard and rowed on England’s rivers for my school and university college. Throughout my life, I have mucked about in vessels of all descriptions: an aquatic bicycle I invented and built; a canoe called Cigarette ; a Royal Navy destroyer. Once, at school, I won a breaststroke race, and I stuck with it in adulthood. Gliding through the water, head up, is the naturalist’s stroke. You see more, placed on equal terms with the animal world around you: the newt, the moorhen and the grass snake, coiling its way across the surface of the water, head held high as if it does not like to get splashed.

The swimming journey rst suggested itself in my moat, a linear pond dug into the clay to the south of my sixteenth-century farmhouse. The yeoman farmer-builder who excavated it found a useful source of clay for the base of the house; it created a barrier of sorts against livestock; and it was a status symbol in this part of Su olk, where late-medieval moats are commonplace. During the three and a half decades I have lived here, the moat has been a leaf- lled swamp, a boating lake, a dining room – when thickly iced – and my own, spring-fed, plant-cleansed natural pool.

When I began Waterlog, I became obsessed with what D. H. Lawrence calls the ‘third thing’. For nearly three years, I gave my life over to the elusive element that is water. The writer and the swimmer in me both had an identical aim – to leave our baggage behind and oat free. Like all swimming, this was an escape, and it was also stimulation and consolation. Immersion in natural water has always possessed a magical power to cure. I can dive in with a long

face and what feels like a terminal case of depression, and come out a whistling idiot. Swimming was my Keatsian ‘taking part in the existence of things’ and it bequeathed a new way of seeing the world. Britain looks very di erent from its ponds, streams, rivers, lakes and seas. On land, so much is signed, interpreted or controlled that reality becomes virtual reality. The watery realm resists all that. Travelling in water becomes a subversive activity, as I discovered when I swam the trout- lled ri es of the Itchen and was accosted by the River Keeper of Winchester College. Crossing the Fowey, in Cornwall, I was chastised by the coastguard for making the swim without the harbourmaster’s permission. I was mistaken for 007 when emerging from a stately home’s ornamental lagoon. I contracted Frenchman’s Creek swamp fever, I was panged by the guilt of being a philanderer of rivers, and I experienced the numbing chill and purple knees provided by the swirling brown North Sea on Christmas Day.

The climax of my aquatic tour of Britain was the discovery of a hidden canyon, a deep gash in the limestone beyond the top of Wensleydale lled with white water. My descent into Hell Gill’s dim and glistening insides, a succession of cold baths, was one long primal scream. It was a rebirth and a rite of passage, like every swim. But there was a greater, cumulative e ect from all these natural swims. Some people pass through holes in trees or walk over hot coals. It is a response to a simple need to change in the same way as trees shed their leaves in autumn or grow new ones in spring. I swam in cold water. The tree has branches lopped o but grows out new shoots. It may bear more fruit the following year.

To my surprise and delight, Waterlog, an obscure idea with a small print run, has continued to bear fruit since it was published in 1999, an occasion we marked with music, drinking and swimming at the outdoor council pool behind Covent Garden. As dog-eared, water-smudged copies are passed between friends, Waterlog ’s journey has inspired people to discover or rediscover wild water. Clubs that coalesce around ancestral swimming spots on stretches of river that were once moribund are busy with members once again. Campaigns to save civic pools gain vigour.

In the six years since, I’ve splashed through the shallows of celebrity life – breakfast shows, columns, literary festivals – which is not something I ever coveted. Meanwhile, I have plunged into the cool depths of researching what Edward Thomas called ‘the fth element’. I have immersed myself in trees to write ‘Touching Wood’, a book about wood as it exists in nature, in our souls and in our lives. ‘A culture is no better than its woods,’ wrote Auden and our

woods, like water, have been suppressed by the modern world. They have come to look like the subconscious of the landscape.

I’ve been telling stories since I could talk, just as in the beginning my mother told stories to me. My rst were boyhood fantasies I shared with friends after escaping my tiny bungalow on the edge of London for the spinneys and ponds then found nearby; next came essays at school where my best teachers did not suppress a child’s natural inventiveness; letters to chums about interesting travels to boost their spirits; and then stories to make a living and sell products, stories to delight and seduce. All the while, my own tales were electri ed by the thousands I read, particularly romantic yarns of adventure and liberation: Blyton, Crompton, Stevenson; Lawrence, Keats, Je eries.

A year after the beginning of sexual intercourse as identi ed by Philip Larkin, I graduated and moved to London. Through the sixties, I wrote blurb for Penguin Books – Rogue Male and other thrillers by Geo rey Household – becoming a copywriter and then creative director for advertising agencies in Soho. I sold stories about Coca-Cola, BMW and British Coal. ‘Come Home to a Real Fire’ was my best-known line, reasserting the pleasure of a real re in an age of central heating. Its plangent note resounded with the public, until it was recycled and subverted, as all the best lines are, by Welsh Nationalists in their incendiary campaign against second homes owned by the English.

In advertising, I learned the discipline of writing and rewriting, sanding and polishing, labouring over a single sentence for days. But I tired of the stories I was selling and so escaped to the country, where I raised goats and my own house, and taught storytelling to young people at the local grammar school. There is no more intimate way of getting to know your neighbours than by teaching their children. It was the time of the Barsham and Albion fairs in the Waveney Valley, a rural culture built by an extended family of quasi-hippy immigrants to the countryside, based on the values of the Whole Earth Catalog and John Seymour’s The Fat of the Land. Self-conscious selfsu ciency sounds dreary but this was a moment of liberation and celebration. For a brief golden epoch, we built with our hands and imaginations ephemeral, dreamlike, Gypsyish, shanty capitals in elds full of folk. Dancing and music played a big part.

Later, the gigs I arranged for our local heroes led me to host major concerts for transatlantic rock stars. The lms I devised with friends became documentaries shown on national television. I also organised street gatherings to save the whale, campaigning for Friends of the Earth to protect disappearing

cetaceans and rainforests. As green concern became concentrated on these far horizons, I co-founded the charity Common Ground, collaborating with artists and writers to speak for our near horizon: the quiet, ordinary, local nature of hedgerows and old orchards that surrounded me at Walnut Tree Farm and should still surround us all.

I have always written down stories – dreams, fragments, re ections, moments of great joy and despair and anger – in old school notebooks that line my shelves. I live in a library made up of millions of my own words. Writing stills my mind. In recent years, I’ve found my thoughts restlessly returning to many minuscule memories from childhood.

My hair has turned from brown to grey and is now frost-white. The crinkles around my eyes and lips are deepening into crevasses. When I cut a branch of fallen elm, the grain seems more resistant to my saw. When I cross the moat on my return from a long adventure, past the ash and the walnut, a pair of guardian trees that watch over the place, I always feel the relief a badger must feel as it eases itself back into the sett after a hard night’s foraging. Now, however, it takes me longer at rest to regain my vitality. Strange pain assails me in the night. And yet when I wake the world seems as young as ever on a glittering winter’s morning. It is time. At the dawn of 2006, the time has come to share some of my stories.

chapter 2

A war baby – reared outdoors – my second home, the Cosy Cabin – the luxury of daydreaming – adventures in the wilds of suburban Hatch End – an unreconstructed hunter-gatherer boy ornithologist – stilt-walking and ice-skating – the romance of travel – my father, Alvan Deakin – my great-uncle, Joseph Deakin, the Walsall anarchist – hook-handed Grandpa Wood and my hero, Uncle Laddie – more about my mother, Gwen, rebel and force to be reckoned with – claustrophobia

The bomb shelter on our street. The cherry tree on the corner. The laurel hedges I raided to ll my butter y killing jars. Singing lessons with Mrs Gillard, putting her hands on my stomach as I sang. Skating with Ann Wilks. The sound of the bass booming into my pillow on Saturday nights from the dance band at the recreation pavilion. The roller skates bump-bumping over the gaps between paving stones as we sped downhill past the railings through which we fed Mr Stimpson’s chickens with bread crusts. Major Cracknell. Mrs Cracknell yelling at Hitler to get o her garden fence. ‘You think I can’t see you, but I know you’re there. Come out of there, you devil!’ She would rattle at the fence with her broomstick. We minded our own business.

Britain was at war when I was born but my earliest memories are of peace. I lay gazing at sunshine dappling the leaves of the trees above me, placed in the optimum spot in the garden for growing by my mother, who believed that leaves ltered sunlight, allowing the most bene cial of its rays to pass through and nourish me with vitamin D. I must be as brown as a berry, and so I was parked in my pram under lilacs, hazels and apple trees behind our tiny halfbungalow at the point where London ended and the countryside began.

There was a run of glorious summers in the forties. Looking back, I remember every daylight moment being in the garden with my mother, who was evangelical about the bene ts of fresh air. My early childhood was mostly a relationship of two, my mother and I, together in the garden that she cherished. I was the apple of her eye. Like most war babies, I saw less of my father, Alvan. He was serving as a warrant o cer in the RAF, controlling the movement of troops. He was at home more than many fathers during the con ict but he was stationed in Germany after the war’s end until 1946. And at home, my father rather shrank from view. Mum was the force of nature.

Gwen and Alvan came to parenting late by the standards of the day. They were in their thirties when they married, in Warwick, in September 1940, and were both thirty-four when I was born on 11 February 1943. No more ospring followed so I was an only child: lively, healthy, much admired and perpetually grubby. Tousled hair, grimy hands, dirty feet, lthy clothes. What a mess. Mum would despair. Sometimes, I eschewed clothes altogether, running naked in our back garden, which was much bigger than our two-bedroomed semi-detached home. I was full of energy and conversation and a lust for adventure. On one occasion I fell into the cess pit in the garden; another time, I tried to bring down the enormous elm in the bottom hedge, aiming a hatchet at a minuscule notch over what seemed like several years, barely making an impression, while my parents benignly turned the other way.

No. 6 Randon Close was built on high ground in the suburbs north of Harrow. Behind our garden was Hall’s dairy farm, which must have been some of the closest farmland to the city. Standing in the garden with London at my back, I gazed out at what seemed to be the whole of rural England stretching into the distance beyond Hatch End and Pinner Hill. Looking from our front door in the opposite direction were rolling suburbs, houses increasing in density all the way to the city’s centre, which could be reached in a three-minute trot to the station at Headstone Lane and a half-an-hour train, or a slower tube on the Bakerloo line. My father was one of the commuters who lined the platform each morning to catch the train to his job with British Railways, based at Euston station. One side country, the other side town; I’ve kept one foot in each throughout my life.

John Mills , older cousin People used to say, ‘He is rather precocious, isn’t he?’ Highly intelligent but people found him trying at times. He was quite hyperactive. He was into everything as a young boy. He had these crazes – from one thing to another – but was particularly involved with wildlife.

Andrew Crook , cousin As a child, Roger told you everything he did. He could be rather bolshy and pushy. He was eighteen months older than me and that gave him a huge amount of power. He was quite intimidating on occasions and he used to make comments that I didn’t understand.

I longed for some alternative habitat to our cramped kitchen and living room, and my father built it for me at the bottom of the garden. It was a wooden shed, and we called it the Cosy Cabin. We wrote the name on a tin sign above the door. It was my refuge from the trials of family life and school, and I was allowed to sleep there on a camp bed in summer.

I assembled a family of animals to live with me: beetles and woodlice in matchboxes, guinea pigs, rabbits, white mice and other pets I procured from the wild, including pigeons. Some creatures, a toad for instance, would enter as guests and be observed for a while before being set free. I remember the toasty aroma of the animals’ straw bedding, fresh hay, the rank hogweed I collected each morning, and the sound of multiplying rodents chewing contentedly. In my bedroom there were grass snakes, lizards, tree frogs, stick insects, fossils, and a praying mantis or two on the curtains. I had a pet crow at one time, which would sit on my shoulder. Gerald Durrell was my favourite author; these creatures were my friends. My parents’ indulgence lls me with amazement and gratitude. I didn’t know it then but my father was much

in uenced by Henry David Thoreau and his retreat was a shed complete with nine bean-rows in the bee-loud glade of the local allotments. He was also fond of quoting William Cobbett, who observed how pigeons gave children ‘the early habit of fondness for animals’. As an only child, relationships with other animals were hugely important to me.

In the Cosy Cabin, I learned the sheer luxury of daydreaming. It has been my making and my undoing. How many days, weeks, months have I lost to it? Perhaps it isn’t lost time at all, but the most valuable thing I could have done.

My nocturnal dream world was a big part of my life too. My lucid, serial dreams are still quite as real to me now as they were then. I had a dream friend, and went to bed each night secure in the certainty that I would continue my serial dream with her. She was slightly older than me, and the relationship was entirely asexual. We went on adventures, we talked, and other dream chums entered our world. I could break o in mid-dream in the morning and resume it that night. This dream world was a happy one, and a consolation from daily life, even though my childhood was far from unhappy. The dream friendship was central to my existence, but so far as I know I spoke of it to no one. My parents never had the slightest trouble in getting me o to bed. Much later, I was reassured to learn from Ronald Blythe that he had a slightly senior female dream friend as well.

Roger Deakin , The Wellingtonian school magazine, Easter 1953My dreams I always dream,

So strange they usually seem,

To trees a furlong high

The birds do backwards y, And leopards lurking in the trees

To feast upon my bonny knees.

The dreary morning comes at last, And all the strangest dreams are past.

*

Like every child of my era, I was soon roaming beyond the con nes of my garden. Through the bottom hedge was a large eld, two ponds and a brook,

still preserved today as they were then in the green belt – we called it London’s Corset as teenagers. The green may remain but the range and abundance of species has long gone. In the fties, I found hares and herons, partridges and plovers. The cuckoo called above the trundle of suburban trains. Occasionally, I might put up a snipe.

My friend David Baldwin and I were kings of this wild frontier. We equipped ourselves with wooden ri es, spud guns and an aluminium Vibro catapult that would shoot out a boy’s eye at twenty paces. We obtained Davy Crockett hats made of rabbit skin with tails down the back and sang the song about the King of the Wild Frontier from the Disney movie as we built dens.

Sticks were our weapons of choice. They were useful in woods for thrashing a path through nettles and also provided hours of fun for me and a family of ve brothers called Winney when we discovered that the whip in green sticks of ash or hazel could be used to propel balls of moist clay impaled on the tip huge distances from our back gardens over the rooftops. As soon as our parents were out, salvoes of mud shells would rain on to the street on a wing and a prayer that no one was passing by.

From sticks we made arrows and shing-net handles. You could never hold a stick without reaching for your penknife, which was the beginning of all craft. Sticks taught me the basic anatomy of wood and how it behaves under the blade: how it splits, how it bends, how it breaks, how bark peels to reveal the white sapwood and how, when you whittle it, you come to the pithy centre, or the brown heartwood, or encounter the sudden toughness at the junction of a branch. Hours of whittling with my penknife taught me about the relative resistance of each di erent wood, the hardest being the seasoned oak lid of my school desk.

We played Robin Hood with Mr Stimpson, the baili of the nearby dairy farm, unwittingly cast in the role of the Sheri of Nottingham. We crept about in the corn, or hid in the fringes of the wood observing Stimpson’s movements intently. We learned to recognise the excitement of his poultry when he fed them and knew he would be su ciently distracted at such moments for us to make a bolt across the green eld to the cover of the trees.

This spinney was the closest wood to home. But Bricket Wood was the ultimate destination for our expeditions, combining the mysteries of nature and of sex. When we were thirteen or fourteen, we messed about on track bikes which were not motorbikes (except in our heads) but rudimentary bicycles made from bits of scrap Rudge, Raleigh or Dawes in our back gardens. They had only one gear, a very low one, and gas-piping cow-horn handlebars

so wide it was all we could do to stretch out and reach the rubber grips, let alone get them through the garden gate. There were no mudguards and, at most, a single unreliable brake. Instead of inner tubes, we put hosepipe in the tyres, so each time the join came round the bike bucked like a bronco and almost threw us o . The machines were endishly uncomfortable and no good for our fertility. Mine was adorned with a squirrel’s pelt with its tail ying out rakishly from behind. It gave me the appearance of an escaped character from The Wind in the Willows. I have no idea why I thought it might be attractive to girls.

Dismounting after a morning’s sport, we would ease ourselves painfully along Hatch End High Street like cowboys in new chaps. If these were pioneering mountain bikes, they di ered from their modern counterparts in a far more fundamental respect than sophistication: we did not consume these things, we invented and made them.

For a long time, I was too scared to climb trees. I was the one left standing at the bottom squinting up through the branches asking, ‘What can you see from up there?’ Letters from chums travelling have always since sounded to me like those shaming accounts of church spires, distant mountain ranges, barrage balloons, re engines dashing down lanes and (from very tall trees) the sea. Things I could have seen for myself if I’d had the guts to risk breaking a leg.

Perhaps my fear dated from the time we Cubs assembled for our rst jamboree on one of the further elds of Hall’s Farm. We arrived ushed with the glory of a grand march, complete with brass band and drums, along the high street. Our arms still ached from holding up the banner of the 1st Hatch End Cubs, now lying furled beside us. Cross-legged and expectant, we sat in rows under a hot August sun, leaning forward for a better view. We didn’t seem to notice the acute discomfort of the stubble- eld assaulting the tender skin of our inner thighs. We waited before a ne old oak in which a gang of Scouts, proud owners of the tree-climbing badge, were going to demonstrate the gentle art to us groundlings.

We were bidden to silence as the rst Scout began to scale the tree, swinging himself up like a gibbon through the lower limbs. He went higher, disappearing now and then in the shadow of foliage. He was tall and blonde and he made it look easy. The higher he climbed, the further his socks slipped down to his plimsolls. Then, quite suddenly as he scrambled into the top branches, there was a loud report – a branch cracking – and he came spinning down through the leaves like a shot pigeon.

His falling seemed to happen very slowly, and the sound of his body crashing through branches and leaves lives on in me now. Then came the thud as he hit the ground. It made us all feel sick and frightened. None of us had ever witnessed a human body being so seriously injured. The blonde boy lay there, winded, silent. Then his groaning began. Scoutmasters and Cub mistresses gathered round him and brought blankets. Two St John Ambulance men in black uniforms appeared and knelt down. It seemed ages before an ambulance came bumping over the eld. Nobody said anything to us, and nobody dared ask. They carried on with the jamboree, minus the tree-climbing. The ambulance drove o with him, leaving the broken branch behind.

The diving board at Watford baths was another terror. In the pool, I measured myself against my own fear; climbing to the rst board, and then the second, and nally the stomach-wrenching top board, where I stepped o into space, as I have done a hundred times since in my dreams. Stepped o for what seemed like a ve-minute fall down to the green tiles at the bottom.

Water was always part of my childhood universe. My friends and I dammed the muddy autumn streams in the eld-ditch just beyond our garden and raced our pooh sticks down its mighty nine-inch ood, clearing the oak leaves and brambles that impeded their progress as diligently as river engineers. In the middle of the eld, behind a veil of willows, was a large pond. Our arrival would send up the heron with a grouchy cry and a slow beating of wings. At the pond’s edge, like the heron, we could pounce on exotic European tree frogs, a small, brilliant-green amphibian which must have been introduced there by local hobbyists who, like me, would routinely top up home-made aquariums with whatever wild treasures they could seize.

The day we rst discovered the carp in that pond was like nding pieces of eight glinting out of the green depths. Keeping an eye out for Mr Stimpson, we would surreptitiously sh for the carp with the relish of poachers. Elsewhere, there were bomb sites to explore, still abandoned a decade after the Blitz. The wild reasserted itself so fast: reweed, brambles and buddleia rampaging over the rubble.

I was an unreconstructed hunter-gatherer boy ornithologist, typical of the fties, when children who loved nature freely collected whatever they could catch. A snail, a pebble, a leaf, a dead beetle, a chrysalis, a bit of sheep’s wool on a fence – my pockets were a bird’s nest, a microcosm of the local landscape, of habitat and haunts. My nds were of great personal value to me, although my most prized possession was the net I used to catch butter ies, which were plentiful during that run of ne post-war summers. Mine was no

home-made bamboo-and-net-curtain a air but a serious professional model with aluminium frame. In the evening, I caught moths by lurking, net poised, beside a bright light run o an extension lead out to the garden. I gathered laurel leaves from the neighbours’ hedges and crushed them in a ‘killing jar’, producing a natural chloroform that rapidly subdued my captives. While the insects’ wings were still soft, I spread them in display and pinned them to a cork board to dry. Collections were typically kept in drawers so they wouldn’t fade in the sunlight but I stuck mine on my bedroom ceiling so I could lie in bed and gaze up at a rmament of Lepidoptera. Later, I took my net to my penfriend’s place in the south of France and captured my rst swallowtail and praying mantis which, smuggled home, was the rst of many a mantis to live on the kitchen curtains.

When we stayed with my cousins, Andrew and Ian Crook, at their home in Painswick, Gloucestershire, Uncle Frank would take us to hunt for belemnites and devil’s toenails, silurian brachiopods, ammonites and an occasional sea urchin at a nearby quarry. Patiently, Frank fostered our passions; owers and fossils, quarried from the beacon. One morning, we rose early to head out with his poacher’s gun and felled a squirrel. I touched the warm, thin fur, as Uncle Frank slotted back the gun into the innocent walking stick. I turned the squirrel into my rst piece of taxidermy.

Andrew Crook This is a bit of poetic licence. Roger said he wanted to stu a squirrel. So he talked Father into getting up at dawn, and Father took his twelve-bore shotgun and Roger and I went into the woods and Father shot a squirrel for Roger, which he brought back to the house. He then went to the chemist to get some alum and carried out the role of taxidermist. It never appeared again so perhaps it wasn’t as good as it should’ve been.

Ian Crook, cousin Speaking to my father later in life, I think he found Roger rather ill-disciplined. His parents were far more tolerant and permissive and that grated a bit with Dad. He told me he disciplined Roger on one occasion, and Roger was really angry about it. Roger thrust a stick or bamboo cane through the window of our garage and hooked paint pots o a shelf as a revenge move. Anarchic is a good word. It’s also asking for trouble.

At home, my spud guns were eventually replaced by a real airgun. As a child-naturalist I took potshots at birds and rabbits in the elds. ‘Consideration’ is the word my parents always used. ‘Have some consideration’ or ‘Show some consideration’, a slightly di erent thing, so I was taught to raise

the peak of my school cap to neighbours in the street and to give up my seat on the Underground to almost anyone unfortunate enough to be standing. Ladies, certainly, and older people. There was sense in this. Who needs to sit down when they’re seven years old and bursting with energy?

This basic idea of consideration is at the heart of all true conservation. You act out of fellow feeling for other living things, and other people. Most of the degradation of our land, air and water is caused by sel shness. Sel shness and consideration are the two opposites that were constantly before me as choices when young. Should I do the sel sh thing, re my airgun through the neighbour’s garden fence, perforating it almost to destruction? Or should I do the considerate thing and re it dutifully at the target pinned to a tree? Or not re it at all? I confess I enjoyed shooting very much and only gave it up when I had ‘worked it out of my system’.

Rodney Jakeman, friend I would cycle over to 6 Randon Close early on weekends and we would head out with our airguns. Often the wildlife was totally untroubled and perfectly safe. Occasionally a pigeon would be brought down.

John Mills Roger had an answer for everything. ‘I didn’t intend to shoot that squirrel but it happened to be in the line of the gun,’ he said when he brought in a dead squirrel, which he took home and skinned. He wasn’t very successful. They were always smelly things.

My natural-history adventures were in the company of male friends but there were plenty of female playmates to share the trends of the fties. After the yo-yo craze, and about a year before the hula-hoop craze, we had a stilt craze. The neighbours, who had been driven half-mad by the sound of roller skates clicking over the gaps between the paving stones and the grinding trundle of steel wheels on concrete, were drawing a collective sigh of relief when the hollow clip-clop of an army of stilts hobbling on the cobbles assailed the net curtains of the neighbourhood.

Stilt-racing had arrived, and my playmates and I discovered the novel experience of greeting the grown-ups in our street with a lofty, condescending ‘good morning’ from a great height. Suddenly, we could look down on them. We could even have patted them on the head. For short-arses like sickly little Colin Voysey, stilts were the perfect answer. Not only did they achieve parity of height by adjusting their blocks a notch or two higher, but smaller children were more nimble stilt-walkers, being less top-heavy.