Wassily Kandins K y Concerning the Spiritual in Art (with

a Focus on Painting)

and

The Question of Form

Translated by Ruth a hmedzai Kemp With an introduction and notes by l isa Flo R man

p enguin Boo K s

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 1912 This translation first published 2024 001

Translation copyright © Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp, 2024 Introduction and notes copyright © Lisa Florman, 2024

The moral right of the translator and of the author of the introduction has been asserted

Set in 10.25/12.25pt Sabon LT Std Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library is B n : 978–0–241–38480–0

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

Introduction vii

A Note from the Translator xxxv

Concerning the Spiritual in Art 1 The Question of Form

Contents

Notes 139 Image Credits 149

115

Introduction*

The first English-language translation of Wassily Kandinsky’s Über das Geistige in der Kunst appeared in 1914, just a little over two years after the original German publication. The translator, Michael T. H. Sadler, rendered the book’s title as The Art of Spiritual Harmony, imparting to it quasi-mystical connotations not present in the original. Subsequent translations, and indeed even subsequent editions of Sadler’s own translation, used the more straightforward On [or Concerning ] the Spiritual in Art. Even so, over the years Anglophone readers have tended to hear in that title – and in the text’s other frequent references to ‘spirit’ – echoes of a ‘spiritualism’ largely foreign to Kandinsky’s thinking. Much of the confusion arises from the fact that the German word Geist has no clear English equivalent. In addition to ‘spirit’, the terms ‘mind’ and ‘intellect’ have frequently been used to convey its meaning. Thus, for example, the word Geistesgeschichte is commonly rendered as ‘intellectual history’ or ‘history of ideas’.

As used by the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), to choose but the most obvious or overdetermined example, Geist referred to a set of beliefs and values that were collectively held but that also developed over time, that development serving as the engine for all consequential religious, political, intellectual and artistic change. Significantly,

* This introduction draws heavily on the much more extended argument presented in my book Concerning the Spiritual – and the Concrete – in Kandinsky’s Art (Stanford, CA : Stanford University Press, 2014).

Hegel regarded such historical change as having a specific shape or form, which he termed ‘dialectical’. Later commentators, seeking to explicate the Hegelian dialectic, have often described it using the terms ‘thesis’, ‘antithesis’, ‘synthesis’. If Hegel himself preferred other language – above all, the word Aufhebung (commonly translated as ‘sublation’) – he still conceived of development as tripartite. An initial set of beliefs or values is negated or rejected, and antithetical views are taken up, before, in a third moment, the apparent contradiction between those positions is reconciled (or ‘sublated’) and belief returns to itself, albeit substantially changed as a result; at that point, the process begins anew. For Hegel, this simply was the structure of history, the form that any progress necessarily took.

As careful readers of Concerning the Spiritual in Art will discover, Kandinsky’s views on the historical development of painting follow much the same pattern. Although he himself never uses the term ‘dialectical’, he clearly conceives of the moment in which he is writing as a ‘Geistige Wendung ’ or, as the present translation has it, a ‘spiritual shift’, in which artists (and others) are looking to the past as a way to overcome the impasse of the present. In Kandinsky’s view, the paintings produced over the previous several decades were driven almost exclusively by materialistic concerns, in keeping with the broader materialism of modern society. As he describes it, an ‘art for art’s sake’ or l’art pour l’art sensibility had taken hold, specifically in order to justify, or perhaps mask, art’s relinquishment of any larger intellectual or ‘spiritual’ ambition. Painters trained their attention on external form – what Kandinsky refers to as the question of ‘how?’ – rather than on ‘what?’, that is, on the work’s content or inner meaning. Nonetheless, Kandinsky claims to see hopeful signs on two fronts: first, in the fact that some contemporary artists had begun to take an interest in the work of earlier periods, when art played a crucial role in the advance of spirit or Geist ; and, second, that some of the more recent experiments with form had yielded new means by which painting might yet progress. As he writes:

viii int R oduction

If this ‘how’ includes the emotions of the artist’s soul, and if the artwork is capable of radiating his subtler experience, then art will find itself on the threshold of the path to where that lost ‘what’ can almost certainly be refound, that ‘what’ which might form the spiritual bread to feed this nascent spiritual awakening. This ‘what’ will no longer be the material, objective ‘what’ of the figurative period we are leaving behind, but rather it will be artistic substance, the soul of art, which is essential if its body (the ‘how’) is to lead a full and healthy life, just as it is for an individual or a population (pp. 22–4).

In other words, although art’s earlier orientation towards intellectual or spiritual content (towards the question of ‘what?’) had given way in the modern era to narrow, formalist concerns (i.e. to an art-pour-l’art attention to ‘how?’), the two moments were actually to be seen as existing in dialectical relation to one another. In the third moment, Kandinsky insists, during the ‘spiritual awakening’ just beginning to stir, the apparent contradiction will be reconciled or sublated. The question of spiritual or intellectual content will return but at a higher level, accompanied by newly invented formal means adequate to its visualization.

The dialectical structure that Kandinsky describes in modern painting’s relation to its past and future is but one of several ways that Concerning the Spiritual in Art recalls the philosophy of Hegel. In fact, both at the level of its larger argument and in regard to specific terminology, Kandinsky’s text clearly echoes Hegel’s Aesthetics, in which art had similarly been presented as a vehicle for the developing self-consciousness of spirit or Geist. The opening phrase of Concerning the Spiritual in Art – ‘every work of art is the child of its time’ – is lifted almost verbatim from the Aesthetics. The text’s frequent invocation of ‘inner necessity’ (innere Notwendigkeit ) likewise appears to have its origins there. Given this, it does not seem too much of an exaggeration to say that Kandinsky intended Concerning the Spiritual in Art to serve as a direct response to Hegel, a revision of the philosopher’s account that would culminate not in the end of art proclaimed in the Aesthetics but

int R oduction ix

rather in something on the order of Kandinsky’s own abstract or non-representational paintings.

In order to make the nature of Kandinsky’s response intelligible, it will be necessary to review, however briefly, both the argument of the Aesthetics itself and the role it plays within Hegel’s philosophy at large. For Hegel, art was the sensuous embodiment of spirit and, initially at least, more crucial than philosophy or any other mode of thought to its developing selfconsciousness. According to the history articulated in the Aesthetics, the earliest works of art gave shape to a spirit still trying to extricate itself from its subservience to nature, so that it was not yet fully reconciled with sensuous materiality. As yet vague and undeveloped, with no sense of its own autonomy, spirit could express itself only indirectly; works of art could do nothing more than point to their spiritual or intellectual content through their obdurate material form. This is presumably what Hegel had in mind when he designated the period as Symbolic and declared architecture (the pyramids at Giza, for example, or the ancient Egyptian temple precincts, with their colossal colonnades) its predominant and most characteristic form. The material used in those early structures was inherently nonspiritual – mostly heavy stone, whose shape was limited by the laws of gravity – and their exteriors gave little indication of either the spaces or the meanings contained therein.

During the subsequent Classical period, by contrast, sculpture became the predominant form of art. Classical sculptures were still produced out of heavy matter, of course, but now (especially following the invention of hollow bronze casting) with little regard for its weight or natural properties. Each work’s form was determined solely by its chosen subject matter, which in this period, Hegel observes, was almost always the human form. The Aesthetics emphasizes that the cultural beliefs of ancient Greece were perfectly suited to sensuous embodiment – witness the anthropomorphism of their gods – so that the figures of Classical Greek sculpture seemed not only alive but sentient, thoroughly pervaded by spirit, their form and content fused in an indissoluble unity.

Yet the introduction of subjectivity into both the content of

x int R oduction

the work and the form of its presentation signalled the demise of the Classical era. According to Hegel, in the ensuing Romantic period, which arose with the advent of Christianity, spirit came to be characterized by a profound and ever-growing inwardness that, unlike the beliefs of the ancient Greeks, was only imperfectly expressed in the sensuous externality of art. Clearly, sculpture was no longer up to the task, as it was unable to present consciousness as something withdrawn out of the sphere of material existence into self-reflection. It was instead in the painting of the Romantic era that inner subjectivity found its adequate expression. Painting accomplished this by effectively collapsing the three-dimensional world onto a twodimensional plane. Its subject matter was presented via the irreal or ‘unnatural’ space of visual illusion, which had been created by subjectivity itself, for the explicit purpose of its own self-contemplation. In its very form, then, Romantic painting pointed to the insufficiency of materiality to serve as a vehicle for belief following the rise of Christianity.

The Romantic period also differed from its predecessors in that no single art form predominated over its entire duration. At a certain moment, according to Hegel, spirit achieved a state of subjective inwardness no longer suited to even the most subtle of paintings, at which point first music and then poetry (with their still greater immateriality) rose to prominence among the arts. Already within the Romantic era, then, we witness the dissolution, and so the beginning of the end, of art. Not that buildings, sculptures, paintings, musical compositions and poems wouldn’t continue to be produced. They would, but they would no longer function as the primary vehicle of spirit – which is to say that they would no longer serve as the place where humanity realized its deepest and most meaningful truths. That role was given over first to religion and finally to philosophy, from whose vantage point it could be seen that the history of art belonged not, ultimately, to art itself; instead it constituted only a moment, now passed, within the larger history of spirit.

Because the story the Aesthetics has to tell is not in the end its own, it doesn’t follow the same dialectical structure of other Hegelian narratives. In Hegel’s other texts, such as The Phenomenology

int R oduction xi

of Spirit or the Science of Logic, thought is seen to progress through three interrelated stages: from abstract universality (characterized by an inchoate unity) to concrete individuality (in which attention is directed towards the differentiation of parts), and finally to an integration of those two earlier moments in a concrete universality able to comprehend not only the whole but the place of the parts within it. If the larger movement from art through religion to philosophy generally follows this pattern, the specifically art-historical narrative of the Aesthetics does not. We are instead presented with an inverted dialectic, an ‘unhappy’ turn of events: art reaches its apex in the second (Classical) moment, and then ends its story in the dispersion of its particular forms. The task of gathering those pieces together and reintegrating them into a meaningful whole is left to philosophy – more precisely, to the comprehensive understanding that Hegel himself presented in the Aesthetics and elsewhere.

If there was plenty that Kandinsky and other artists could admire in the Aesthetics – particularly the crucial role it assigned to art in the early development of Western thought – there was also much to dislike. Its ending was especially unappealing. According to Hegel, art, which had once been the primary vehicle of spirit, no longer even kept company with it; in the modern world, painting had been abandoned to its own devices. For his part, Kandinsky aimed to show that art’s apparent estrangement from spirit was only a temporary phenomenon – only a brief (secondary) moment within a dialectical sequence that would eventually culminate in their reconciliation. Indeed, his principal ambition in Concerning the Spiritual in Art appears to have been to rewrite Hegel’s conclusion so as to restore a properly progressive shape to the dialectic of art’s history and, in the process, assert the continuing spiritual or intellectual relevance of painting and the other Romantic arts. Admittedly, Kandinsky doesn’t use Hegel’s ‘Romantic’ nomenclature, and the contemporary forms that he singles out for attention are painting, music and (in the place of poetry) dance. Nonetheless, in contrast to the ultimate dispersion of the arts in Hegel’s account, Concerning the Spiritual

xii int R oduction

in Art presents an ever-greater convergence – modern dance, music and painting increasingly aligning themselves around their similar ambitions, or what Kandinsky describes as their ‘shared inner endeavour’ (p. 42).

He focuses especially on the relation of painting to music. Whereas Hegel claimed that the former had irrevocably ceded its dominant role to the latter, Kandinsky sought to show how the two art forms were, or at least could become, the equivalent of one another. According to the Aesthetics, music had supplanted painting as the leading art during the Romantic era because painting was inadequate to ‘object-free inner life, to abstract subjectivity as such’.1 To this Kandinsky replied, in effect, that inner subjectivity would, however, find its adequate form in an object-free, abstract painting. Hegel, living in the early nineteenth century, had taken it as given that painting was representational and therefore tied to a kind of pictorial thinking ultimately limiting to spirit. But what if painting could divest itself of figuration and all representational content? In that case, it could become like music, which, except in certain specific cases (i.e. programme music), rarely attempts to portray natural phenomena. One of the recurrent themes of Concerning the Spiritual in Art is that painting was moving ever closer to the condition of music and that, in the increasingly abstracted forms of latenineteenth- and early-twentieth-century art, it had finally found the means by which it could again become adequate to spirit in spirit’s present, advanced stage of development. It should be noted, however, that in 1911 Kandinsky had not yet made any wholly non-representational paintings. Concerning the Spiritual in Art offers a theoretical defence of such work in advance of its actual production. Kandinsky appears to have felt that an audience did not yet exist for abstract painting; Concerning the Spiritual in Art was plainly intended to help with its cultivation. And in fact the book proved enormously successful in that regard. Not only did it sell out almost immediately, going through two subsequent editions in the span of twelve months, its popularity seems to have spurred Kandinsky to produce his first wholly abstract or non-representational work.2 Several other European artists, including the Czech

int R oduction xiii

painter František Kupka and the Frenchman Robert Delaunay, did likewise at about the same time. Indeed, the more or less simultaneous appearance of abstract painting in several distinct European contexts is fully in keeping with the model of historical change presented in Concerning the Spiritual in Art. According to Kandinsky, change is always dependent on a small group of pioneering figures who are able to overcome the forces within society bent on maintaining the status quo. Here, too, Kandinsky’s views concerning the history of art diverge somewhat from Hegel’s. In contrast to the fundamentally unified entity described in the Aesthetics, spirit or Geist as presented by Kandinsky exists always in conflict, its progress dependent on a few clear-sighted individuals with the strength and tenacity required to press forward. He explains its internal divisions via the image of an isosceles triangle:

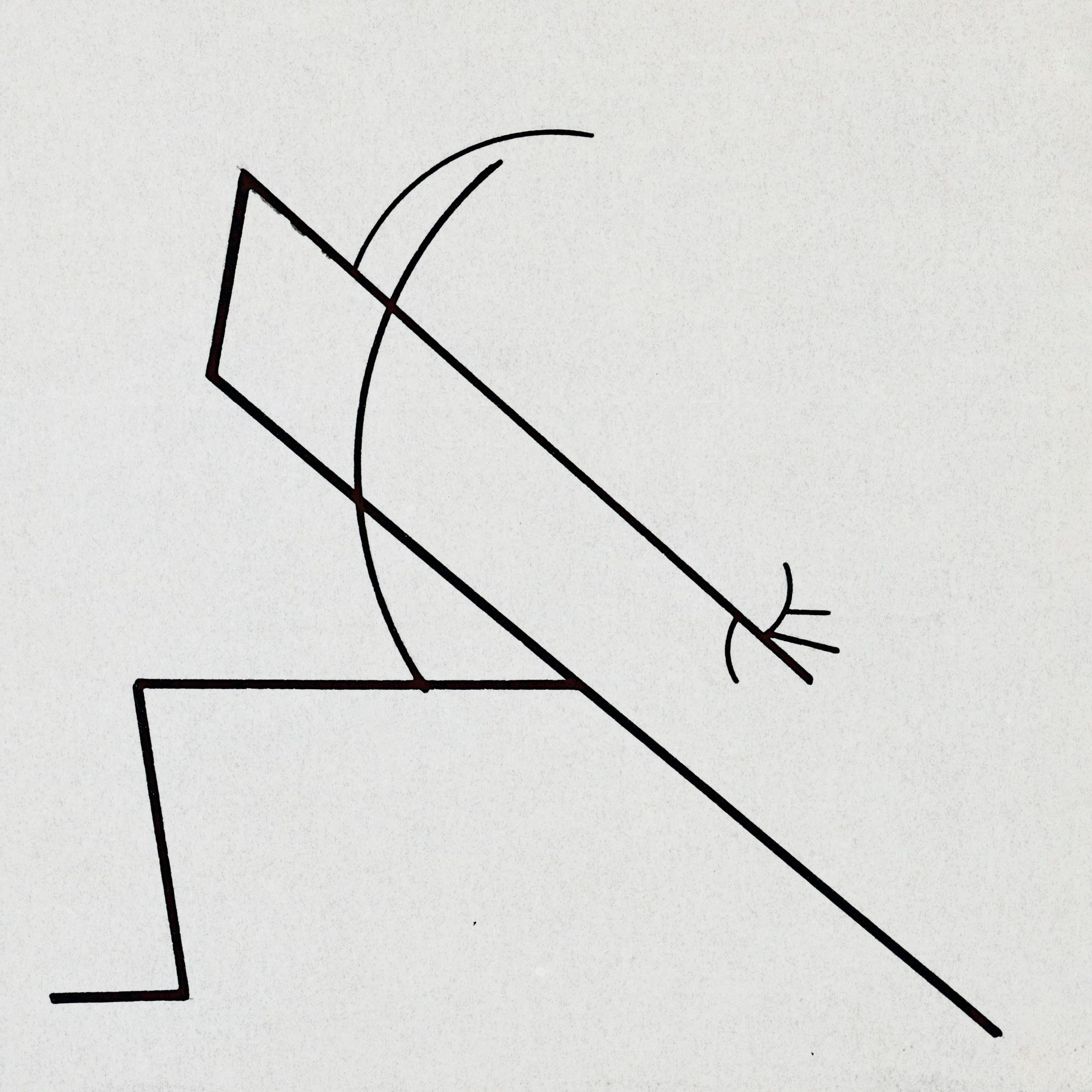

Picture, if you will, a slender triangle pointing upwards, divided into unequal horizontal bands, with the sharpest angle and the narrowest band at its peak: this is a graphical representation of the spiritual life of a society. The lower down in the triangle, the broader and taller are the bands into which the triangle is subdivided, and the larger the area within them.

The entire triangle is slowly moving forwards and upwards, its motion so gradual that it is barely perceptible. What is at the peak ‘today’ will shift down to the next section ‘tomorrow’. This means that what today only those at the highest point can fathom, and what is unintelligible nonsense to everyone in the rest of the triangle, will tomorrow become a meaningful and soulful part of life for those in the next band down. (p. 19)

The image Kandinsky provides is thus one in which society not only is stratified but also encompasses disparate temporalities. Those individuals at the acute tip of the triangle live, in some sense, in advance of those nearer the base and, as an unfortunate consequence, are frequently subject to widespread scorn and derision.

Kandinsky singles out for example the case of the Viennese composer Arnold Schoenberg, ‘recognized and celebrated by

xiv int R oduction

precious few’, dismissed ‘as a “swindler” and a “charlatan” ’ by almost everybody else (p. 34). Significantly, while Kandinsky was working on his manuscript, he attended a concert of the composer’s work.3 Two weeks later, after making several sketches and a painting inspired by that evening’s programme, Kandinsky wrote to Schoenberg himself, thereby initiating a remarkable correspondence and, eventually, friendship. At the time, Schoenberg was also working on a book, his Theory of Harmony (Harmonielehre ), which would be published in 1911, between the completion of the manuscript for the first edition of Concerning the Spiritual in Art and its second printing. Kandinsky, after receiving a copy of the text from the composer, clearly read it as being closely aligned with his own project; in fact, in his preface to the second edition of Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky expressed the hope that his own ‘reflections [would] eventually form the elements of a sort of Theory of Harmony for painting’, which would be a ‘natural continuation’ of his previous efforts (p. 9).

Kandinsky seems to have grasped relatively early in their exchange one of the central arguments of Schoenberg’s text, namely, that ‘consonance’ and ‘dissonance’ were conventional and relative terms, rather than the poles of an immutable opposition, as they were usually taken to be. In the book, Schoenberg would assert that ‘dissonance’ was simply a ‘consonance’ more remote from the fundamental tone, and that the evolution of Western harmonic technique could be analysed in terms of music’s increasing incorporation of dissonance within itself, in an ongoing climb up the overtone series. Kandinsky, at least, appears to have understood this history as essentially dialectical. Which combination of notes was at any moment regarded as ‘harmonious’ was always determined via others considered antithetical to harmony – until, that is, their opposition was discovered not to be an opposition at all. From this perspective, even the atonal music that Schoenberg was then producing would one day be folded into the historical narrative, the compositions’ apparent dissonance becoming familiar, accepted, and thereby elevated or ‘sublated’ into a newfound consonance. In a letter to Schoenberg from January 1911, Kandinsky summarized

int R oduction xv

the importance of these ideas to his own thinking: ‘I am certain that our own modern harmony,’ he wrote, is to be found ‘via “dissonances in art”, in painting, therefore, just as in music’. ‘Today’s dissonance,’ he added, in language remarkably similar to Schoenberg’s own, ‘is merely the “consonance” of tomorrow.’4

Despite Schoenberg’s occasional equivocation on the matter, Kandinsky clearly saw atonal composition as defiantly avoiding the ‘natural harmonies’ of the diatonic scale, and so also as moving away from the authority of nature in the direction of spirit’s increasing self-legislation. As he wrote in Concerning the Spiritual in Art : ‘Schoenberg’s music takes us to a new realm where the listener’s response to the music is not an acoustic experience but one felt entirely by the soul. This is the point of departure,’ Kandinsky declared, ‘for the “music of the future” ’ (pp. 34–5). For Kandinsky, then, the lesson of atonality was the same as that of non-representational painting. The history of art and music alike revealed (or at least soon would reveal) the achievement of self-determination, of a mode of artmaking no longer set or in any way limited by nature.

The challenge, of course, was to convince people that if music and painting were both in the process of overcoming nature’s normative authority, they were not, for all that, descending into normlessness. Kandinsky underscored the point in Concerning the Spiritual in Art through a direct quotation of Schoenberg, who had written that ‘any simultaneous combination of sounds, any progression is possible. Nevertheless, even today, I feel that . . . there are certain conditions on which my choice of this or that dissonance depends’ (p. 34). What needed to be proven was that these ‘conditions’ were neither naturally given nor arbitrary – that they were instead the result of art’s internal development up to that point, the product of what Kandinsky referred to as its ‘inner necessity’.

Kandinsky’s own commitment to contradiction and dissonance, and to establishing the conditions of their appearance, is made especially clear in the chapter titled ‘The Language of Form and Colour’. In that chapter, Kandinsky dismisses as outdated the practice of keying a painting to a particular colour or,

xvi int R oduction

more commonly, to a certain, narrowly delimited section of the colour wheel:

Letting one colour permeate another, combining and binding together two adjacent colours: these are all techniques used to construct the chromatic harmony. From what we have said about the effects of colours, from the fact that we live at a time full of questions, explanations and premonitions, and therefore full of contradictions (we might recall the layered bands of the triangle), we might easily conclude that composing harmonies on the basis of a single colour is quite inappropriate for the complex times in which we live. It is perhaps with rueful envy that we hear Mozart’s works. They are a welcome break from the roar of our inner life, a flash of consolation and of hope, but we hear them like an echo from a bygone era, another time that is fundamentally unfamiliar. Whereas notes and tones in conflict, a lost equilibrium, tumbling ‘principles’ . . . contrasts and contradictions – this is the harmony of our times’ (p. 81).

In his pursuit of chromatic conflict, Kandinsky went so far as to create his own colour wheel (Fig. III , p. 78), which was subtly if significantly different from the one devised by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and still widely used today by practising painters. Perhaps the most intriguing deviation in Kandinsky’s version occurs in the lower right quadrant, where the normal positions of blue and purple have been reversed. The reasons underlying this reversal were undoubtedly multiple, though chief among them was almost certainly a desire to discourage artists from thinking in terms of the colour contiguities emphasized by the more traditional arrangement. The separated, self-enclosed circles around every individual hue of Kandinsky’s chart also work to that same end. In fact, as the caption and roman numerals indicate, the chart is oriented far more towards oppositions than adjacencies. Kandinsky seems to have based his views of colour on what was then known as the ‘opponent-process’ theory of vision, first advanced in the 1870s, and passionately championed for several decades thereafter, by the Viennese physiologist Ewald Hering. Hering’s theory represented a radical challenge to

int R oduction xvii

the reigning orthodoxy of the views espoused by Hermann von Helmholtz and Thomas Young. In contrast to the trichromatic (red–blue–yellow) Young–Helmholtz model, Hering’s opponentprocess theory held that there were four primary colours: red, blue, yellow and green. Moreover, Hering argued that in perception those colours exist as oppositional pairs (green versus red, blue versus yellow), sensory responses to one hue of the pair being antagonistic with, or inhibitory to, those of the other. In other words, according to his model, the output of retinal receptors was encoded as either red or green, blue or yellow, but never both simultaneously. The same was true, he asserted, of light and dark, black and white.

Kandinsky’s colour wheel is constructed, as his text makes clear, around precisely the oppositions identified by Hering. Unlike Hering, however, Kandinsky established a hierarchy among the antagonistic pairs. Yellow and blue represent the primary antithesis, he claimed, as they epitomize the most fundamental distinction, that between warm and cold colours. He saw white and black as only slightly less important, in that they determine the relative lightness or darkness of any given shade. These first two oppositions (marked by the roman numerals I and II ) form the horizontal and vertical axes of Kandinsky’s revised colour chart. Hering’s third oppositional pair, red/green, is joined on the circle by the other two hues – orange and purple –that had also been part of Goethe’s schema and that had, as a result, become traditional for every colour wheel since.

With the aid of his revised, antagonistically arranged, wheel, Kandinsky had a means of systematically producing colour dissonance. By juxtaposing hues that, according to Hering’s opponent-process theory of perception, were mutually incompatible, he could produce combinations that were the antithesis of ‘natural harmonies’ and yet were still ‘not to be interpreted as “disharmonious”, but rather [as representing] another possibility and another kind of harmony’ (p. 52).

We can get a fairly good idea of how Kandinsky employed colour dissonance in his early paintings by looking to the highly finished sketch for Composition No. 2, which is now in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum, New York. Kandinsky

xviii int R oduction