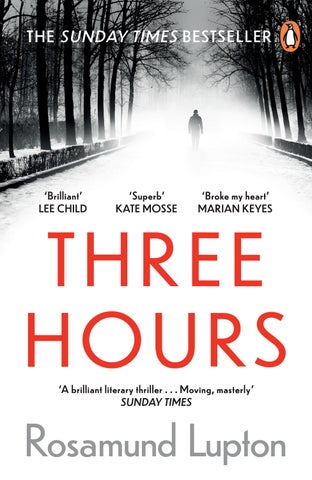

‘Brilliant’ LEE CHILD

‘Superb’ KATE MOSSE

‘Broke my heart’ MARIAN

KEYES

‘A brilliant literary thriller . . . Moving, masterly’ SUNDAY TIMES

‘Brilliant’ LEE CHILD

‘Superb’ KATE MOSSE

‘Broke my heart’ MARIAN

‘A brilliant literary thriller . . . Moving, masterly’ SUNDAY TIMES

‘It is early days but this could be one of the thrillers of the new decade. A sensational depiction of a school under siege in rural Somerset during a violent winter snow storm, it is breathtakingly good . . Intense, horrifying and brilliantly told . . If you read only one thriller this year, make it this one: it is that good’ Daily Mail

‘Moving, masterly . . A flawlessly executed story that owes as much to theatre – the rotating ensemble cast, the echoes of Greek tragedy as well as Shakespeare – as it does to crime fiction. Too often in “literary thrillers” either the genre element or the bookish content is merely gestural; here both part of the label are justified, and the balance is just right’ Sunday Times

‘A beautifully written, incredibly gripping story about a school held under siege by gunmen. But this is not a bloodbath – it’s a drama that celebrates the resilience, courage and love of ordinary people caught in extraordinary circumstances . . . Lupton’s layered storytelling is utterly compelling. I urge you to carve out three hours (or more) of your own time to read this in one sitting; you won’t be able to put it down’ Adele Parks, Platinum

‘A Somerset school is under siege in this tensely emotional thriller, unfolding over the titular three hours: ordinary heroes are revealed, as teachers and pupils are tested by extraordinary events. A breathlessly involving read that is also a disquisition on community, love and self-sacrifice’ Guardian

‘Rosamund Lupton deftly explores the roles played by social media and the press in such a crisis, sometimes with palpable anger, and throws in a few chilling twists, but this novel’s greatest strength is its moving depiction of the anguishes of parenthood and the wild possibilities of first love’ The Times, Book of the Month

‘Lupton’s fourth novel is an extraordinary achievement and kept us on the edge of our seats from start to finish . . . If you’re looking for a tense literary thriller, Three Hours by Rosamund Lupton is outstanding’ Independent

‘An electrifying, pulse-racing novel’ Red

‘An urgent, heady hit of high-octane storytelling’ Metro

‘Propulsively plotted and full of vivid characters, Three Hours held me in its eloquent grip’ Emma Donoghue

‘Wow! This is a stunner of a book, staggeringly good’ Jane Fallon

‘The tension is at times extreme. But the most original and impressive aspect of the novel is its examination of goodness confronted with psychopathic brutality’ Literary Review

‘The drip-feed of information keeps the reader hooked and setting the story over three hours creates extraordinary tension that builds to a nerve-wracking crescendo. A gripping, white-knuckle ride’ Daily Express

‘I hardly dared to breathe as I raced through this incredible book, set in a school under siege by masked gunmen. Although it’s the very definition of a page-turner, the storyline about a pupil who is a Syrian refugee with PTSD makes it especially moving’ Good Housekeeping

‘In a read that’s not for the faint-hearted but is utterly brilliant, Rosamund Lupton explores a three-hour siege by gunmen in a snow-bound Somerset secondary school. This is an incredibly tense book that gets to the heart of violence, terror and the emotional impact of those caught up in events beyond their control. Written with real perception and beauty, Three Hours is set to be a breakout read for book groups and beyond’ Stylist

‘A novel that you live rather than merely read’ Daily Telegraph

‘Three hours of intense, heart-stopping drama are stripped back and relayed from different perspectives in this thrilling novel . . . A truly exceptional read’ Sunday Independent

‘Intersperses scenes of breath-sucking tension with stirring meditations on human nature . . Immensely satisfying as an action driven thriller but its real resonance lies in exploring the mysteries of the human consciousness’ Sara Collins, Guardian

‘Three Hours manages to have the taut crispness of a thriller while also immersing the reader in the personalities of her characters’ Mishal Husain, Radio Times

‘This gripping story over three terrifying hours creates extraordinary tension’ Daily Mirror

‘Lupton’s characterization reveals a profound understanding of the human spirit under intense pressure, as well as the teenage mind’ Canberra Times

‘An unputdownable nail-biter about a siege at a school in Somerset that ends up being deeply affecting and even profound’ India Knight

‘Utterly breathtaking and dazzling’ Jenny Colgan

‘Astonishing, powerful, terrifying, heartbreaking’ Emma Flint

‘Three Hours is Rosamund Lupton’s best book yet, and that is high praise. Chilling, suspenseful, humane and brave’ William Landay

‘An incredible, unbelievably powerful book . . . Simply stunning’ Dinah Jefferies

‘A masterclass in suspense’ Cara Hunter

‘A beautiful book and at the same time heartbreaking, haunting and relentless’ Abi Daré

‘Three Hours has a voice all of its own. Rosamund Lupton makes you race through the pages with her irresistible storytelling. Impossible to stop until you reach the poignant end!’ Jane Corry

‘Wonderful, heart-aching, warm, terrifying. I stole every spare minute to read it’ Gytha Lodge

‘There’s no one else writing quite like Rosamund Lupton in fiction today. Three Hours is exceptional – at turns heartbreaking, warm, terrifying, perceptive and grippingly page turning’ Kate Hamer

‘This is an incredible novel: a heady combination of elegant writing, nuanced characterization, deep emotion and heart-stopping tension’ Elizabeth Brooks

‘I read Three Hours in two days, in awe. A modern rumination on the issues that divide twenty-first-century life, a celebration of refugees, of mental health, of love and hope and bravery. I loved it more than I can say’ Gillian McAllister

‘Three Hours is about hate crime, but what rings out from its pages – what is likely to stay with you long after you’ve read that magnificent last line – is love. I wanted to read Three Hours slowly to savour every beautiful word, yet it is so compelling that I couldn’t put it down. It is phenomenal’ Fiona Mitchell

‘Beautifully written, emotionally note-perfect and nail-bitingly tense. It’s BRILLIANT’ Tammy Cohen

‘Lupton tells her story with searing beauty and unbearable tension. Exquisite. Compassionate. Painful. Fantastic. Don’t read this if you want to be able to put it down’ Kate London

‘I finished Three Hours in the wee small hours of this morning. It’s mind blowing. A large cast of characters and yet you feel genuinely emotionally engaged with each one . . Amazing’ Francesca Jakobi

‘Three Hours is a brilliant novel – moving, relevant and honest. An exceptional and heartbreaking read’ Jenny Quintana

About the Author

Rosamund Lupton is the author of Sister, a BBC Radio 4 ‘Book at Bedtime’, a Sunday Times and New York Times bestseller and winner of the Richard and Judy Book Club Best Debut. Her next two books Afterwards and The Quality of Silence, also Richard and Judy Book Club choices, were Sunday Times bestsellers. Her books have been translated into over thirty languages.

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Viking 2020

Published in Penguin Books 2020 001

Copyright © Rosamund Lupton, 2020

Extract from ‘Burnt Norton’, Four Quartets, by T. S. Eliot, reproduced courtesy of Faber and Faber Ltd

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–37451–1 www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

an inspiration and an exceptional person, thank you

And you? When will you begin that long journey into yourself ?

Rumi (1207–1273)

A moment of stillness; as if time itself is waiting, can no longer be measured. Then the subtle press of a ngertip, whorled skin against cool metal, starts it beating again and the bullet moves faster than sound.

It smashes the glass case on the wall by the headmaster’s head, which displays medals for gallantry awarded in the last World War to boys barely out of the sixth form. Their medals turn into shrapnel; hitting the headmaster’s soft brown hair, breaking the arm of his glasses, piercing through the bone that protects the part of him that thinks, loves, dreams and fears; as if pieces of metal are travelling through the who of him and the why of him. But he is still able to think because it’s he who has thought of those boys, shrapnel made of gallantry, tearing apart any sense he’d once had of a benevolent order of things.

He’s falling backwards. Another shot; the corridor a reverberating sound tunnel. Hands are grabbing him and dragging him into the library.

Hannah and David are moving him away from the closed library door and putting him into the recovery position. His sixth-formers have all learnt rst aid, compulsory in Year 12, but how did they learn to be courageous? Perhaps it was there all this time and he didn’t notice it; medals again, walked past a hundred times, a thousand.

He tries to reassure them that even if it looks bad – he is pretty sure it must look very bad indeed – inside he’s okay, the who of him is still intact but he can’t speak. Instead sounds are coming

out of his mouth that are gasps and grunts and will make them more afraid so he stops trying to speak.

His pupils’ faces look ghostly in the dim light, eyes gleaming, dark clothes invisible. They turned o all the electric lights when the code red was called. The Victorian wooden shutters have been pulled shut over the windows; traces of weak winter daylight seep inside through the cracks.

He, Matthew Marr, headmaster and only adult here, must protect them; must rescue his pupils in Junior School, the pottery room, the theatre and the English classroom along the corridor; must tell the teachers not to take any risks and keep the children safe. But his mind is slipping backwards into memory. Perhaps this is what the shrapnel has done, broken pieces of bone upwards so they form a jagged wall and he is stuck on the side of the past. But words in his own thoughts grab at him – risks, safe, rescue.

What in God’s name is happening?

As he struggles to understand, his thoughts careen backwards, too fast, perilously close to tipping over the edge of his mind and the blackness there; stopping with the memory of a china-blue sky, the front of Old School bright with owering clematis, the call of a pied ycatcher. His damaged brain tells him the answer lies here, in this day, but the thoughts that have brought him to this point have dissolved.

Hannah covers Mr Marr’s top half with her pu a jacket and David covers his legs with his coat, then Hannah takes o her hoody. She will not scream. She will not cry. She will wrap her hoody around Mr Marr’s head, tying the arms tightly together, and then she must try to staunch the bleeding from the wound in his foot, and when she has done these things she will check his airway again.

No more shots. Not yet. Fear thinning her skin, exposing her smallness. As she takes o her T-shirt to make a bandage she glances at the wall of the library that faces the garden, the shuttered windows too small and too high up for escape. The other wall,

with oor-to-ceiling bookcases, runs alongside the corridor. The gunman’s footsteps sound along the bookcases as he walks along the corridor. For a little while they thought he’d gone, that he’d walked all the way to the end of the corridor and the front door and left. But he hadn’t. He came back again towards them. He must be wearing boots with metal in the heel. Click- click click- click on the worn oak oorboards, then a pause. No other sounds in the corridor; nobody else’s footsteps, no voices, no bump of a book bag against a shoulder. Everyone sheltering, keeping soundless and still. The footsteps get quieter. Hannah thinks he’s opposite Mrs Kale’s English classroom. She waits for the shots. Just his footsteps.

Next to her, David is dialling 999, his ngers shaking, his whole body shaking, and even though it’s only three numbers it’s taking him ages. She’s worried that the emergency services will be engaged because everyone’s been phoning 999, for police though, not for an ambulance, not till now, and maybe they’ll be jamming the line.

When I am Queen . . . Dad says to her, and she says, When I am Queen there’ll be a separate line for the police and ambulances and re service, but she can’t hear Dad’s voice any more, just David’s saying, ‘Ambulance, please,’ like he’s ordering a pizza at gunpoint, and now he’s waiting to be put through to the ambulance people.

It was the kids who started the rush on 999 calls, not only directly but all those calls to mothers at work, at home, at co ee mornings, Pilates, the supermarket, and dads at work, mainly, but some at home like hers, and the parents said: Have you phoned the police? Where are you? Has someone phoned the police? I’m coming. Where exactly are you? I’m on my way. I’m phoning the police. I’ll be right there. I love you.

Or variations on that call, apart from the I love you ; she’s sure all the parents said that because she heard all the I love you too -s. Dad said all that. She’d been in the English classroom then, where phones are allowed. Not allowed in the library, left in a basket outside, switched o . David is using hers.

She’s trying to rip her Gap T-shirt to make a tourniquet for Mr Marr’s foot, but the cotton is too tough and won’t tear and she doesn’t have scissors. She only wears this T-shirt in winter under something else because everyone wears Superdry or Hollister, not Gap, not since lower school, and now she’s in front of loads of people, including the headmaster, wearing only her bra, because her clothes have had to turn into blankets and bandages, and she doesn’t feel any embarrassment, just ridiculous that she ever minded about something as stupid as what letters were on a T-shirt. She wraps the whole T-shirt around his foot.

Click- click click- click in the corridor. The door doesn’t have a lock. She goes to join Ed, who’s pulling books out of the bookcase nearest to the door, fiction w– z , and piling them up against it.

Why’s he just walking up and down the corridor?

She tries not to listen to the footsteps but instead reads the titles of the books as they use them to barricade the door: The Color Purple by Alice Walker, Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh – click- click – The Time Machine by H. G. Wells – click- click – To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, Godless in Eden by Fay Weldon, The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. She imagines bullets going through the books, leaving splashes of purple, a wrecked time machine, a smashed lighthouse lamp, and everything going dark.

She returns to Mr Marr while Ed continues adding more books to the large heap against the door. As she kneels next to him, Mr Marr’s eyes icker and catch hers. Before he was shot Mr Marr told her love is the most powerful thing there is, the only thing that really matters, and as she remembers this she digs the palm of her hand into her T-shirt bandage covering his foot to staunch the bleeding.

But the word shot lodges in her mind, cruel and bloody, making her nauseous. Shot isn’t written down or spoken so she can’t cover it up with her hand or shout it down and she wonders what a mind-word is if it can’t be seen or heard. She thinks that consciousness is made up of silent, invisible words forming unseen sentences and paragraphs; an unwritten, unspoken book that

makes us who we are. Mr Marr’s eyes are closing. ‘You have to stay awake, Mr Marr, please, you have to keep awake.’ She’s afraid that if he loses consciousness the silent invisible book of him will end.

The footsteps sound louder again alongside the library wall, coming back towards them. She has to try to be calm, has to get a grip. Dad says she’s resourceful and brave; George in Famous Five, Jo in Little Women. Never a pretty girl, especially not a pretty teenage girl, she has developed a sturdy character. Ra says she’s ya amar, like the moon, but she doesn’t believe him .

Ed has moved on to fiction s– v, trying to stay out of the line of re if he shoots, throwing books on to the pile from the side. There’s many more books at the bottom, new ones sliding down from the summit to the base.

The footsteps get to outside their door and stop. She holds her breath, hears her heart beating into the silence, then the footsteps walk past.

Daphne Epelsteiner, the fty- ve-year- old drama teacher, has loved the school theatre since it was built ve years ago for its practical beauty and sensitive aesthetic. Designed to look as if it’s an organic part of the woods surrounding it, it’s formed of two connected cedar boxes. The larger box houses the generous stage, auditorium and foyer; the smaller one has a rehearsal room, dressing rooms and two props rooms.

Now she loves the theatre because it is safe. There are no windows for the bastards to shoot through. The walls are only faced with cedar, beneath is mortar and concrete; a budgeting and re issue. There are re-exit doors at the back leading directly out into woodland, but the headmaster was concerned about vandals and thieves breaking in from the woods so the re doors are exceptionally strong and robust. (Thank the Good Lord for vandals and thieves and budgeting and re issues and the headmaster.)

Teenagers are hiding under the seats in the auditorium, a few

under the stage itself. She can hear them talking to one another and doesn’t silence them, not yet. They don’t need to be quiet until she gives the signal.

Five teenagers are hiding in the barricade left over from last year’s performance of Les Misérables, because no one knew what to do with it and Daphne couldn’t bring herself to throw it out. It looks nished on the outside, but in the cavernous interior rough-sawn wood and half-hammered-in nails scrape at them; they breathe in dust and ecks of old paint. Twelve others are hiding behind a theatrical forest, saplings felled last week from the woods around the school and stored four deep backstage.

Just over half an hour ago a police car was shot at near the gatehouse, they think he was ring from the woods. Then three minutes ago they heard two shots in Old School. So there must be two of them, maybe more.

Old School is linked to them by a corridor, which ends in doors to their foyer. She has left these doors open and feels their openness as a coldness on her back, a terrible vulnerability. But what else could she do? The theatre is the safest place in the school, virtually unassailable, like a huge panic room. The children and teachers in Old School must get here and be safe too; then she’ll lock the doors. But leaving them open might be jeopardizing the safety of her students here in the theatre, which is why she must hide them, as best she can, until everyone in Old School can join them – or until it’s clear that they are not able to – and only then will she lock the doors.

Something might well go wrong. The thought nags at her, throbs inside her chest. What if she doesn’t reach the doors in time? She could be shot, a decent chance that she will be. She’s pretty sure that the doors are impregnable once you lock and bolt them, like the ones at the back, they are security doors, but they’re not likely to be bulletproof. She just hopes she’ll be shot after, not before, she’s locked them.

Her young colleague Sally-Anne, all corkscrew auburn curls and pink cheeks, is acting as lookout in the foyer and will let her

know by WhatsApp the moment that their colleagues and students – or the gunmen – are coming their way. Although mobile reception in the theatre is patchy, every part of it gets Wi-Fi.

‘Okay everyone in the barricade?’ she asks the kids in the Les Mis prop, her voice sounding extraordinarily jolly, she thinks, as if she’s calling out something in a panto. There are some valiant yes- es. For a moment, she remembers the barricade last year in the triumph of a production, Enjolras holding his red ag aloft, the students on the barricade so courageously idealistic and heart-breakingly naive. It stabbed you in the solar plexus when the parts were played by genuine teenage students, rather than adults in a West End production.

‘You’re doing brilliantly,’ she says to them.

She is missing four students: Dom Streeter, Jamie Alton, Ra Bukhari and Tobias Fern. She’s least worried about indolent Dom, who texted her at 8.20 saying he was running behind, most probably from beneath a fuggy duvet. She imagines him idly pedalling his bike along the road and seeing police cars at the turning to the school; not allowed any further.

Jamie Alton was here earlier this morning but left at 8.15 to get the witches’ cauldron from the CDT room in New School, which means he’s safe, surely it does, because New School is right next to the road, easy as pie to evacuate everyone in New School, so no need to panic about Jamie.

Ra Bukhari didn’t turn up at all this morning and he hasn’t texted. She has a huge soft spot for Ra , nearly all of them do; everything he’s been through, and that smile and quick intelligence. Those liquid dark eyes, like a gazelle. Extraordinary, kind, beautiful boy. But he’s survived a boat in a storm and people smugglers; he has survived Assad and Daesh and Russian bombers, for heaven’s sakes; of all these children, the adults too, he knows how to look after himself.

But Tobias Fern. Anxiety for Tobias feels heavy and unwieldy, like a squirming toddler refusing to be put down, a feeling that

is the opposite of Tobias himself: tall and slim, self- contained and private, a boy who only just tolerates being touched. Tobias sometimes loses track of where he’s meant to be and has been found wandering around the school campus with his noisecancelling headphones. But he was looking pale yesterday, she commented on it to him, urging him to get a good night’s sleep, so she can allow herself to hope that his mother’s kept him home today and in all the chaos her message hasn’t got through.

No WhatsApp message from Sally-Anne in the foyer.

She goes backstage to check on the kids hiding behind her forest. Some are covered by evergreen spruces and are surprisingly well camou aged, but others are sheltering behind deciduous lea ess trees and their clothes and pale faces shine through.

‘Birnam Wood! You need to have make-up. Dirty faces, please.’

The woodland parts. Saplings are laid on the oor.

She hands out make-up cases. ‘Make each other’s faces grubby; browns and greens.’

They hurriedly put make-up on each other’s faces, ngers clumsy. Joanna starts on her friend Caitlin, neatly using a brush. Daphne thinks about telling Joanna just to slap it on, this is not the Make-up Design module of a GCSE drama exam, but suspects this is how Joanna is coping so will leave her be.

‘You’re in a safe place here,’ she says to them all. ‘There’s no windows and the doors are extra strong. There’s no way they will get to us.’

‘But you haven’t locked the doors to the corridor, have you?’ Luisa asks. Her twin brother, Frank, is in the library in Old School.

‘No,’ Daphne says. ‘I haven’t locked them. Right, once your make-up’s done, put on your costumes.’

Their costumes for Macbeth are brown hessian tunics, which are used pretty much for every production in some form or another. For Macbeth, they’re tied with rope round the waist as tunics. They’ll blend better behind the trees than colourful hoodies and T-shirts.

‘Are we going to rehearse?’ Joanna asks.

Mother of Mary, is Joanna even on this planet?

‘Maybe later,’ she says to Joanna.

‘Are Anna and Young Fry safe?’ Josh asks. ‘Have you heard?’

Seven-year- olds Anna and Davy, nicknamed Young Fry, are playing the Macdu children but weren’t due to be here till before their cue, in over an hour’s time.

‘They were doing art in New School this morning,’ she says. ‘So they’ll have been evacuated.’

‘You’re sure, Daphne?’ Josh asks her.

‘Yes, easy to evacuate New School.’

They all call her Daphne, which started when they were much younger because her surname is long and complicated, so they called her ‘Miss Daphne’, and then as they got older they dropped the ‘Miss’, and for heaven’s sakes, what does it matter what they call her? But it does. It’s like they trust her not to be separate from them, to level with them.

‘What about everyone else in Junior School?’ Antonella asks.

‘There will be a contingency plan,’ Daphne says, making it up as she goes along, not levelling with them, because what possible contingency plan can there be for everyone in Junior School, a remote building at the end of the drive, a mile from the road and help? She’s tried ringing colleagues in Junior School but nobody has answered. Focus on these children right now, because they’re the only ones you can help.

Boys and girls are changing in the same room, which wouldn’t normally happen. A few are clearly embarrassed and she’s heartened because they can’t be that afraid if they’re able to be self- conscious; though teenagers can probably be self- conscious in any situation.

‘Once you’re changed I want you behind the trees again. Become Birnam Wood! Method act a woodland!’

A few smiles. Brave kids.

She helps the last few camou age their faces, the ones whose partner’s hands were shaking too much to do it.

‘Won’t be long now till the police are here,’ she says, because surely the police will help them soon. ‘This is just me being ultra- cautious; my OCD kicking in.’

She hides them behind the rows of saplings, then goes to the props rooms. The rst one is locked and Jamie Alton has the key but the second larger one is unlocked and lled with more saplings. She drags them backstage. The bark splinters into her hands and they’re heavy. Last year, when their house was ooded out, Philip had called her a trooper and now she’s acting out that part because she doesn’t know what other part she can play that will be of any use to the children.

They are well hidden behind the trees, surprisingly so. There’s a good chance that if her plan goes wrong and the gunmen come in and just have a quick look, they won’t be seen. A really good chance.

She goes from the auditorium to the foyer. This evening, two students were meant to stand by the auditorium doors, handing out Macbeth programmes to parents and sta .

There’s a bar area in the foyer and security doors to the glass corridor that links to Old School. A hundred feet long, the corridor goes through the woods and was designed so that people could come and go from the theatre to Old School without getting wet, and she’d been snarky about it – has no one ever heard of an umbrella? – but now it means escape and safety.

She’d hoped to see children and teachers running along the glass corridor through the woods to the sanctuary of the theatre. But the corridor is deserted, snow falling all around it. There are no lights shining at the other end from Old School; the door shut and the school in darkness.

There’s just Sally-Anne standing watch at their open doors holding a nail gun. She doubts a gunman will allow Sally-Anne near enough for her to re nails at him but admires her pluck. Good grief, she’s using her grandmother’s war words; there’s a whole vocabulary to go with this new character she’s playing, although she’s starting to feel that this is her most real self; that

how she has been to this point was a just a read-through for who she is now.

‘Anything?’ she asks Sally-Anne.

‘No. How are our kids doing?’

Daphne wonders if she imagined the stress Sally-Anne put on ‘our’, signalling where Daphne’s responsibilities should be; pointing out that the safest thing for their kids would be to lock the doors of the corridor their end and block o the means of escape for everyone in Old School. Sally-Anne could be holding the nail gun not because she’s plucky but because she’s protecting herself with the only available weapon. She’s worked with Sally-Anne for nearly four years, but you don’t know a person, she realizes, including yourself, not until the everyday is stripped away. Sweet young Sally-Anne could be anyone at all; colleagues who’ve worked together for years, friends, can be turned into strangers with one another.

‘Do you think the theatre is really that safe?’ Sally-Anne asks.

Because if the theatre isn’t ‘really that safe’, then they cannot o er a haven to the other teachers and students and so can lock their doors without any guilt.

‘Yes I do,’ she replies.

‘Good,’ Sally-Anne says. ‘We’ll wait then, as long as we have to.’

‘Birnam Wood have make-up on,’ Daphne says. ‘I wanted them to splodge on some camou age but Joanna made up Caitlin like a wood nymph.’

Sally-Anne half laughs.

‘You think a nail gun will do any good?’ Daphne asks.

‘We can always hope. Might slow them down. I thought we should rig up the brightest lights and if we see the gunmen shine the lights in their eyes. It’ll blind them for a bit; buy us a few more minutes.’

Daphne likes the symbolism of blinding with light and feels ugly for doubting her.

9.20 a.m.

Beth Alton is driving her Prius like a bat out of hell, Mum, down the country road, skidding on ice, righting the car and foot at down again. School in lockdown. Told by a PTA group text, not Jamie. Hasn’t heard anything from Jamie. One hand holds her mobile to her ear, other on the steering wheel. Jamie still not answering; pick up, pick up, pick up.

You don’t let me drive like this, Mum, even on a farm track.

You’re a learner.

Dad’s going to be seriously unimpressed if you dent it.

I know.

Pretend it was someone in Waitrose’s car park again. It was.

Jamie’s laughter. All in her head.

His number goes through to message again: ‘Hey, it’s Jamie, leave me a message.’

‘Jamie, sweetheart, it’s Mum again. Are you okay? Please ring me.’

Why isn’t he answering?

Her mobile rings, a jolt of hope, but it’s her husband, Mike, that’s displayed.

‘Anything?’ Mike asks.

‘No.’

‘You know what he’s like with his mobile,’ Mike says.

‘But he’d phone, with this happening he’d phone us.’

‘I meant he forgets to charge it,’ Mike says. ‘Or leaves it somewhere. He was doing the dress rehearsal this morning, wasn’t he?’

Why does that matter?

‘He’ll be in the theatre,’ Mike says. ‘Safest place in the school. No windows. Like a bunker.’

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘Yes, that’s where he’ll be.’

Thank God for Zac and even Victor, who she loathes but now forgives, because Victor and Zac are the reason that Jamie’s in the theatre, they’re the friends who persuaded him to join in the production of Macbeth, otherwise – she doesn’t want to think about otherwise. Safest place in the school.

‘I’m getting the train, should be at the station in an hour, but the snow’s making things slow.’

He’s in Bath, meant to be at a conference.

‘Okay.’

She ends the call. No missed call or message from Jamie. But he’s in the theatre, safe, Zac there too; all of them together.

It’s just props, Mum, wasn’t like I had to audition or anything.

Props are really important. And Zac’s doing the technical side too, isn’t he?

Yeah, lights. Victor is Macbeth.

Props are just as important.

As the main part? Seriously, Mum?

To me, yes.

Heart soft as a baby bird.

Is that from that TV series?

And I try to give her a compliment.

She looks up Zac’s number on her mobile contacts, swerving into the snow- covered verge as she takes her eyes o the road. She presses dial, two wheels on the verge, the car tipping at an angle. As Zac’s phone rings, she remembers Jamie’s rst day, joining in Year 10 after being bullied at his mean, strict school for the previous three years – not sporty like his older brother, not resilient. The other pupils at Cli Heights School had looked so relaxed in their scru y clothes, so con dent, arms casually ung round each other; Jamie a sti wooden pin, as if still wearing a blazer and balancing a cap. Then he’d made two friends, Victor,

older than Jamie but new like him, and Zac, the same age, who’d been at the school since Reception, a warm-hearted, easygoing boy who’d clap his arm round Jamie’s shoulders and say ‘Jamester!’ and Jamie would look startled but pleased. Zac’s text nickname for him was ‘J-Me’ and Jamie loved it, still uses it for his Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram. Jamie’s never become as outgoing and con dent as Zac, the unchecked cruelty at the previous school leaving a legacy of vulnerability.

Zac’s phone goes through to message.

‘Zac, it’s Beth, Jamie’s mum. Are you with Jamie? Is he okay? Can you ask him to ring me?’

She hangs up and rights the car, jolting back on to the road. She didn’t think to ask Zac if he was okay.

She hasn’t seen much of Zac recently, not for ages, because Jamie hasn’t seen him outside of school, at least not at their house. Yesterday she was actually worried about that.

She’s nowhere near the school yet, but there are police cars blocking the road so you can’t even see the school or your child running down the driveway towards you – because that’s been the spooling lm of fantasy all this time, that he will run to you and you will be there and that’s the end of it.

Other parents’ cars are just stopped any old how along the verge. No one is wearing coats, one father still in pyjamas; everyone running to their cars to get to school. Beth hurries towards the police, surrounded by a group of parents. A man is shouting at them, ‘Why aren’t you in the school? Why aren’t you doing anything?’ Other voices as she tries to push her way through:

‘Armed police are coming.’

‘There’s been shots inside Old School.’

‘Are any children hurt?’

‘A few minutes ago.’

‘Has anyone been hurt?’

‘I thought he was in the woods, by the gatehouse.’

‘Must be more of them.’

‘He’s in the corridor.’

Beth, a slender ve foot two, not a pusher or shover, is at the front, elbows outwards, facing a police o cer. ‘I have to get to the school. My son’s in there.’ A right of entry, because who can argue with that? The police o cer looks at her like everyone else here has said the same thing.

‘We’re asking relatives to go to The Pines Leisure Centre, outside Minehead. Do you know how to get there?’

But how can she possibly leave him?

‘A police o cer at the leisure centre will update parents with information.’

She’s torn between not wanting to leave the place where he is and wanting to be told he’s okay; that he’s safe. She walks back to her car, the icy ground slippery under her shoes, other parents also returning to their cars.

She hadn’t noticed the snow falling, covering her hair and shoulders, but as she drives away, the snow melts, dripping down her neck inside her collar, o her sensibly cut hair and on to her hands, and she feels like she’s abandoning him.

The trees and roads and hedges are being covered in snow, making the familiar landscape unrecognizable.

A text buzzes from Zac.

Hey Beth, J-me went 2 CDT room 2 get cauldron

He’s not safe in the theatre with Zac and his friends. Not safe.

* * *

In the library, Frank is in the alcove furthest from the door, crouched under a Victorian table that’s bolted to the oor, one hand pressing his mobile against his left ear as he talks to his mum. He has his mobile and laptop with him, even though they’re not allowed in the library, jittery if he’s away from his technology. His other hand is over his right ear to try to block

out the sound of the footsteps. They make him feel breathless, like they are hands squeezing his throat. His twin sister, Luisa, is in the theatre, safe.

Feeling a coward, treacherous, he pretends to his mum that he’s almost out of charge and ends the call, because at some point it stopped being her comforting him and turned into him comforting her and he just couldn’t do that any more. He hands his phone to Esme, crouched next to him.

There are thirteen of them in here and to start with it had been almost fun in a weird kind of way, it was all Code red!! Lockdown!! like they were starring in a Net ix series, but now Mr Marr’s been shot and footsteps are walking up and down and it’s something that makes you terri ed and small and huddled into yourself.

He looks up at the shuttered windows, too narrow for a person to get through and too high up. Even if they could t, it wouldn’t do any good. There were gunshots earlier near the gatehouse – back when it was all dramatic and exciting and not frightening, before it really began – so there’s another gunman out there, maybe more than one, and no cover on the lawn. Frank thinks of deer running and a sniper picking them o , and hunches down, as if he can make himself even smaller, as if that will help.

Hannah is with Ed and David; they’re helping Mr Marr and talking to the ambulance people and piling up books against the door. He hates himself for not being brave like them. A nerd, he says to himself, a computer nerd, what do you expect? Furious with himself. Hannah is splattered in blood and just wearing a bra and he’s never seen anyone so impressive in his life before. He’s had a crush on her since Year 7, something delicate and gentle and secret. Other boys wouldn’t understand, they don’t think she’s pretty. Ra does though; Ra thinks she’s gorgeous. Lucky Ra .

Hannah checks Mr Marr’s head wound. It’s not bleeding as much but he’s getting paler.

The footsteps have stopped for almost a minute, he’s just standing still in the corridor. What is he waiting for?

On her phone David is saying ‘but how soon?’ and ‘he needs help right away’, like he doesn’t trust them to get an ambulance here as fast as they can.

She hardly has any charge left and all the time David talks to the 999 people the percentage left for Dad and Ra ticks down, which sounds a bit ‘last dance on the Titanic’ but on this ordinary school morning is true; she’d called goodbye up the stairs to Dad, didn’t kiss him, didn’t even see him.

In the corridor, he’s started moving again, coming closer towards them: click- click click- click. Why couldn’t he have worn trainers and been stealthy? She’d choose stealthy over this, like some deadly kind of tinnitus. He must’ve bought boots with metal in the heels specially. Must’ve known it would make people feel like she does. Arsehole.

David hands her back her phone. ‘Sorry,’ he says because there’s no charge left. ‘They didn’t say when the ambulance will get here.’

There’s a mobile being handed round at the back of the library and maybe they should take it but surely the ambulance will get to them as quickly as possible, surely you don’t need to chase up an ambulance when your headmaster’s been shot; and people also really need to talk to their parents.

She doesn’t notice Frank coming over until he’s crouching down next to them. He has a laptop with him; she’d never had him down as a law-breaker.

‘There might be something on the news that’ll tell us what’s happening,’ he says. ‘Maybe about help coming.’

‘Brilliant,’ she says to him.

Tap- tap go Frank’s ngers, con dent once he’s at a keyboard, a di erent person. He must have 4G on his laptop because there’s no Wi-Fi in here, part of Mr Marr’s drive to get them all to read books in the library.

He brings up BBC News 24 with the sound muted, as if the

corridor

gunman in the corridor might forget about them if they make no noise. Hannah can see from the screen that all the news is about their school. Even the bit at the bottom, running like a tickertape, which normally has other news, is just about them.

gunman in the corridor might forget about them if they make no noise. Hannah can see from the screen that all the news is about their school. Even the bit at the bottom, running like a tickertape, which normally has other news, is just about them.

gunman in the corridor might forget about them if they make no noise. Hannah can see from the screen that all the news is about their school. Even the bit at the bottom, running like a tickertape, which normally has other news, is just about them.

gunman in the corridor might forget about them if they make no noise. Hannah can see from the screen that all the news is about their school. Even the bit at the bottom, running like a tickertape, which normally has other news, is just about them.

. . . shots in the school grounds . . . 47 secondary school children and 7 members of staff known to be still in the school . . . 140 junior school children and their teachers are unaccounted for . . . uncon rmed reports of an explosion at 8.20 this morning . . . police not giving more information . . .

. . . shots in the school grounds . . . 47 secondary school children and 7 members of staff known to be still in the school . . . 140 junior school children and their teachers are unaccounted for . . . uncon rmed reports of an explosion at 8.20 this morning . . . police not giving more information . . .

. . . shots in the school grounds . . . 47 secondary school children and 7 members of staff known to be still in the school . . . 140 junior school children and their teachers are unaccounted for . . . uncon rmed reports of an explosion at 8.20 this morning . . . police not giving more information . . .

. . . shots in the school grounds . . . 47 secondary school children and 7 members of staff known to be still in the school . . . 140 junior school children and their teachers are unaccounted for . . . uncon rmed reports of an explosion at 8.20 this morning . . . police not giving more information . . .

‘Junior school’s okay though, right?’ Ed says.

‘Junior school’s okay though, right?’ Ed says.

‘Junior school’s okay though, right?’ Ed says.

‘Junior school’s okay though, right?’ Ed says.

‘They’re a mile away from the road,’ Frank says. ‘And surrounded by woods. So the gunmen probably don’t even know they’re there.’

‘They’re a mile away from the road,’ Frank says. ‘And surrounded by woods. So the gunmen probably don’t even know they’re there.’

‘They’re a mile away from the road,’ Frank says. ‘And surrounded by woods. So the gunmen probably don’t even know they’re there.’

‘They’re a mile away from the road,’ Frank says. ‘And surrounded by woods. So the gunmen probably don’t even know they’re there.’

Frank seems newly bold to Hannah, crouching close to her and Mr Marr.

Frank seems newly bold to Hannah, crouching close to her and Mr Marr.

Frank seems newly bold to Hannah, crouching close to her and Mr Marr.

Frank seems newly bold to Hannah, crouching close to her and Mr Marr.

‘Anything about a rescue?’ David asks. ‘An ambulance?’

‘Anything about a rescue?’ David asks. ‘An ambulance?’

‘Anything about a rescue?’ David asks. ‘An ambulance?’

‘Anything about a rescue?’ David asks. ‘An ambulance?’

‘No,’ Frank says. Hannah thinks he sees her disappointment. ‘But I was being stupid before. I mean, the police aren’t going to say on telly, are they? They’ll keep it secret.’

‘No,’ Frank says. Hannah thinks he sees her disappointment. ‘But I was being stupid before. I mean, the police aren’t going to say on telly, are they? They’ll keep it secret.’

‘No,’ Frank says. Hannah thinks he sees her disappointment. ‘But I was being stupid before. I mean, the police aren’t going to say on telly, are they? They’ll keep it secret.’

‘No,’ Frank says. Hannah thinks he sees her disappointment. ‘But I was being stupid before. I mean, the police aren’t going to say on telly, are they? They’ll keep it secret.’

‘What about the man in our corridor?’ Ed asks.

‘What about the man in our corridor?’ Ed asks.

‘What about the man in our corridor?’ Ed asks.

‘What about the man in our corridor?’ Ed asks.

‘Not yet. But it’ll be the same thing; they won’t say.’

‘Not yet. But it’ll be the same thing; they won’t say.’

‘Not yet. But it’ll be the same thing; they won’t say.’

‘Not yet. But it’ll be the same thing; they won’t say.’

An aerial picture of their school comes up on the screen.

An aerial picture of their school comes up on the screen.

An aerial picture of their school comes up on the screen.

An aerial picture of their school comes up on the screen.

‘Must have a drone with a camera,’ Ed says. ‘A local journalist maybe. Or someone’s sent it to them.’

‘Must have a drone with a camera,’ Ed says. ‘A local journalist maybe. Or someone’s sent it to them.’

‘Must have a drone with a camera,’ Ed says. ‘A local journalist maybe. Or someone’s sent it to them.’

‘Must have a drone with a camera,’ Ed says. ‘A local journalist maybe. Or someone’s sent it to them.’

It’s weird to see school from above, blurry with snow, and to know that they’re there, right now, inside a news photo. The photo of the school has arrows and captions. At the bottom of the photo is new school , by far the largest of all the buildings, with road next to it; lucky people in New School, they had an escape route. Further up the photo, half a mile away from the road and an escape route, through the woods, is where they are: old school . A little away from old school they’ve marked theatre . Even further up the map, deep into the

It’s weird to see school from above, blurry with snow, and to know that they’re there, right now, inside a news photo. The photo of the school has arrows and captions. At the bottom of the photo is new school , by far the largest of all the buildings, with road next to it; lucky people in New School, they had an escape route. Further up the photo, half a mile away from the road and an escape route, through the woods, is where they are: old school . A little away from old school they’ve marked theatre . Even further up the map, deep into the

It’s weird to see school from above, blurry with snow, and to know that they’re there, right now, inside a news photo. The photo of the school has arrows and captions. At the bottom of the photo is new school , by far the largest of all the buildings, with road next to it; lucky people in New School, they had an escape route. Further up the photo, half a mile away from the road and an escape route, through the woods, is where they are: old school . A little away from old school they’ve marked theatre . Even further up the map, deep into the 20

It’s weird to see school from above, blurry with snow, and to know that they’re there, right now, inside a news photo. The photo of the school has arrows and captions. At the bottom of the photo is new school , by far the largest of all the buildings, with road next to it; lucky people in New School, they had an escape route. Further up the photo, half a mile away from the road and an escape route, through the woods, is where they are: old school . A little away from old school they’ve marked theatre . Even further up the map, deep into the 20

woods, pottery room . And at the top of the photo, almost in the sea, a mile from the road, is junior school . A dotted red line shows the private drive that links up all the buildings.

Hannah hopes that if Frank’s right about the gunmen not knowing where Junior School is that they’re not watching TV, but it’s general information, it’s on the school prospectus even. Hopefully they haven’t done their research. Hopefully they just grabbed a gun on the spur of the moment. And on the spur of the moment will just fuck o again.

There’s a number to ring ‘if you have any information’ tickertaping along the bottom of the screen. Hannah supposes it’s to keep the story going, little titbits added to keep it fresh and spicy. Because Frank is right, the police won’t be telling them anything.

She’s holding her phone tightly, even though it’s out of charge, like it still connects her to Dad and Ra , and she knows that’s ridiculous but doesn’t loosen her grip.

Frank is searching through news sites; all of them are about their school, not like the usual news, all slick and organized, but hurriedly put together. On one site, there’s a male reporter she recognizes talking straight to the camera, as if directly to her.

‘Could this be a terror attack?’ he asks. ‘We’re going now to our terrorism expert, David Delaney.’

She looks up at the skylight. Snow is falling down on top of them, smothering the daylight.

* * *

In the theatre, Daphne and Sally-Anne get a WhatsApp message from Neil Forbright, the deputy head, who is alone in the headmaster’s o ce in Old School.

We can’t get to you. You must lock the doors

‘What do you think?’ Sally-Anne asks.

Daphne thinks their young deputy head is astonishingly brave.

‘We must do as he says.’

She closes the security doors across the entrance to the glass corridor, then locks and bolts them. Everyone who was critical of Neil Forbright will have to see his courage now, even that wretched father of his, who Daphne could cheerfully throttle. But Daphne has seen Neil’s courage for the last year, because teaching with depression is impossibly hard and he managed it on and o for months. Not bravery like this though; because Neil hasn’t only locked himself out of safety – only! – but is shouldering the burden of that decision so she doesn’t need to. But it’s her ngers that locked the door, slid the bolt across, and her hands feel treacherous.

Neil often comes round to theirs for pasta and a chat; other sta trapped in Old School are friends too. And the teenagers. Dear God. She’s known many of them since they were young children in junior school. And now she’s locked the doors against them and left them with a gunman.

Neil didn’t say if anyone was hurt and he would have told them. Surely he would? She hurriedly WhatsApps him.

‘I’ll wait here by the doors,’ Sally-Anne says. ‘In case something changes. In case they can get to us.’

‘Good plan,’ Daphne replies, because she wants to believe something will change, but fears that if it does the likelihood is that it will be for the worse.

But worrying’s no use to anyone in Old School, Daphne, no use at all. You just have to get on with it; put your best foot forward for the children in the theatre until this terrible thing is over; shove to the back of your mind this terrible anxiety about the people in Old School and the missing children and everyone in Junior School and this new love for your husband that keeps inappropriately pressing itself forward. Right then, a phrase she has never used before, suspicious of people who used it, right then, she must keep everyone calm; keep them busy. They came

to school this morning thinking they were going to be doing a dress rehearsal of Macbeth so that is what they are going to do.

She claps her hands, forces her voice to be loud and strong.

‘Tell your parents that you’re safe in the theatre, if you haven’t already, and that you’re turning your phones o – then all mobiles o , please.’

Phones aren’t allowed in the library but the students in Jacintha’s English classroom will have their mobiles with them. She thinks that, like her kids in the theatre, they’ll be phoning their parents rst, poor loves, of course they will, not yet siblings or friends, but they most probably will. If bad news happens, she doesn’t want her kids in the theatre to get it.

They all protest about turning o their phones. She raises her voice above the hubbub of theirs, but keeps it calm.

‘We are going to rehearse Macbeth – Joanna, that was absolutely the right thing to suggest earlier – and I don’t want phones pinging.’

Amazingly, the kids seem to buy this bit of normality, her usual rule, and turn their mobiles o , though she doubts it will last for long.

‘Finish o your costumes and keep your faces as they are. Zac, Luisa and Benny, lighting and set, please. Once you’re ready, refresh your lines.’

No WhatsApp reply from Neil. She opens her copy of Macbeth, playing her part in this charade, and reads the opening; the same opening Shakespeare’s King’s Men would have read four hundred years ago.

Macbeth

Act 1, Scene 1

A desolate place.

Thunder and lightning. Enter three WITCHES