‘Offers a tidy lesson in not just getting more from art, but more from life itself . . . lucid and revealing . . . Gompertz is at his best’

Michael Prodger, The Times

‘By going straight to the essence of each [artist’s] work, Will Gompertz provides a fluent and refreshing introduction to the way art can enable us, in the most unexpected ways, to see the world anew’

Michael Peppiatt‘Gompertz insightfully explores the processes and personalities of a remarkable roster of artists . . . effortless prose and laser focus on the communicative potential of art make this a worthwhile read’

James Woods Marshall‘Gompertz doesn’t have it in him to be boring’ The Times

‘He is a natural communicator whose passion for art is expressed with wit and verve’

Sir Nicholas Serota, Chair of Arts Council England

Will Gompertz is a world-leading expert in, and champion of, the arts. Having spent seven years as a director of the Tate Galleries followed by eleven years as the BBC’s Arts Editor and two years as Artistic Director at the Barbican, he is now the director of the Sir John Soane’s Museum. Gompertz has interviewed and observed many of the world’s leading artists, actors, writers, musicians, directors and designers. Creativity magazine in New York ranked him as one of the fifty most original thinkers in the world. He is the author of the internationally bestselling What Are You Looking At? and Think Like an Artist, both translated into more than twenty languages.

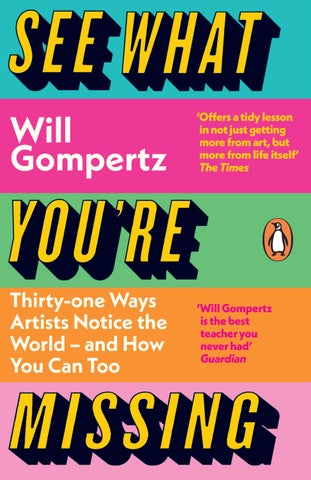

Thirty-one Ways Artists Notice the World – and How You Can Too will gompertz

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Viking 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Will Gompertz, 2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 0 2 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn : 978–0–241–31548–4

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

To my late parents, Frances Gompertz and Dr Hugh Gompertz, who dedicated their professional lives to the NHS, and their spare time to keeping the show on the road at home –always with love and kindness.

Inset 1

1. David Hockney, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire (2011)

2. John Constable, Cloud Study (1822)

3. Frida Kahlo, Las Dos Fridas (The Two Fridas) (1939)

4. Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII (1913)

5. Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field (1965)

6. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Notary (1983)

7. Rembrandt, Self-Portrait at the Age of 63 (1669)

8. Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin (1971–95)

9. Kara Walker, Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994)

10. Fra Angelico, The Annunciation (c.1438–45)

11. El Anatsui, Earth’s Skin (2007)

12. Edward Hopper, Office at Night (1940)

Inset 2

13. Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes (1620)

14. Agnes Martin, Friendship (1963)

15. Jennifer Packer, Tia (2017)

16. Alice Neel, The Soyer Brothers (1973)

17. Paul Cézanne, Large Bathers (1894–1905)

18. Tracey Emin, My Bed (1998)

19. Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995)

20. Cy Twombly, Quattro Stagione (1993–5)

21. Cy Twombly, Primavera, Quattro Stagione (1993–5)

22. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, An Education (2010)

23. Isamu Noguchi, Akari lighting (1951 to present day)

Inset 3

24. Xochipala sculpture, Seated Adult and Youth (400 bc –ad 200)

25. Paula Rego, The Dance (1988)

26. Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, The Smoker’s Case (c.1737)

27. Hilma af Klint, The Ten Largest, No. 7 Adulthood Group IV (1907)

28. Eva Hesse, Ennead (1966)

29. Georgia O’K eeffe, Poppy (1927)

30. Guo Xi, Early Spring (1072)

31. Peter Paul Rubens, Minerva Protects Pax from Mars (1629–30)

32. Jean Dubuffet, Dhôtel Nuancé d’Abricot (1947)

The idea for See What You’re Missing began with an unsolicited email, sent by a man called Tom Harvey, asking me to speak at an event for creative folk in Soho, London. I was working for the BBC as an arts journalist and presenter at the time, a job that generated frequent requests from viewers and listeners inviting me to judge an art competition or give a talk. I accepted as many as I could, but had recently promised my publisher that I wouldn’t take on any more extra-curricular work until I had at least started writing my longpromised book on perception. In truth, the commitment to focus on the book was a stalling device. I hadn’t actually formed a concrete idea about what to write on the topic of ‘seeing’, but I knew it was a rich subject that could be wonderfully enlightening if only I could find the right way into it and overcome the dreaded ‘writer’s block’.

I wrote back to Tom and declined his kind invitation to speak. I explained that, with regret, I had to say no on this occasion because I was spending every spare minute of my day gathering myself for an as yet unwritten, or fully conceived, book about art and observation.

‘Fair enough,’ came Tom’s gracious reply.

see what you’re missing

The following day he sent me another email, in which he included the photograph below:

The sculptor Mark Harvey with his young son Tom

And in the accompanying text he wrote:

I found the attached picture the other day, taken in the early sixties, of dad and me on the beach. I send it because, for me, it’s a lovely reminder of an aspect of some artists, the ability to see di erently. Dad was a sculptor, he was ambidextrous and could write in mirror writing with either hand. His stance in the picture is his beach stance. He would always find the best shells and pebbles and washed-up bits of interesting stu , and I never did. I was so fascinated by his ability to see things where others can’t that I would insist on walking along the beach a yard ahead of him so I would

have the best chance of finding the best stu . I can still remember the frustration at his exclaiming ‘Oh look at this!’ as he found some fascinating shell that I had passed by seconds before.

It was a lovely note to receive. It was also inspiring. Tom’s story opened my eyes to what it was I wanted to explore and understand about art, perception and us. Namely, there is so much to learn from artists about noticing the everyday moments of beauty and wonder that are all around but routinely pass us by. With the help of some great painters and sculptors, we too could become more sensitive, more aware, and more conscious. Those invisible blinkers of presumption that narrow our point of view to something approaching tunnel vision could be removed. In short, we could turn to artists to help us see what we are missing.

Tom’s dad isn’t an outlier; all artists are expert lookers. They make it their business to visually interrogate the world and all that is in it: the people, the places, the things. Artists are the ‘wise old fish’ in the allegorical story told by the American author David Foster Wallace at a Commencement Speech he gave at Kenyon College, Knox County, Ohio on a hot summer’s day in 2005.

After inviting the graduating students to perspire as much as he intended to (he was a notoriously nervous public speaker), the writer launched into his tale about two young fish swimming in a river. After a little while they passed an older fish going in the opposite direction,

who said, ‘Morning boys, how’s the water?’ The two young fish carry on for a while before one turns to the other and says, ‘What the hell is water?’

The wry anecdote was designed to provoke a group of Liberal Arts students, brought up on a high-fibre diet of critical thinking, to apply their analytical skills to the seemingly boring but in fact essential and important stu concerning our quotidian existence: the supposedly dull realities of our daily lives that had been rendered invisible to them by their highly educated minds. The point being that they, we, live our lives in a semi-conscious state for much of the time, going from one routine event to another with our senses suppressed like zombies in a world of the undead. We don’t notice the beautiful pebble on the beach, because – like those vacant young fish – so often we are oblivious to our surroundings. But that doesn’t have to be the case; it doesn’t have to be our partial reality. We can master how to look and experience the world with an artist’s heightened awareness: to have the exhilaration of seeing the world with true twenty-twenty vision.

Of course, there are already hundreds of books about how to look at paintings, from John Berger’s famous Ways of Seeing to Peggy Guggenheim’s gloriously candid autobiography Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict. There are also many books about art and perception, with Ernst Gombrich’s Art and Illusion among the best I’ve read. But there are possibly fewer books

combining elements of both approaches – not only to explore how looking can add to our appreciation of artists, but also to explore how artists look, adding to our appreciation of life.

Familiarity doesn’t so much breed contempt as cause a form of blindness, where we stop seeing our surroundings. Siegfried Kracauer, the twentieth-century German film critic, knew this. He wrote in his book Theory of Film (1960): ‘Intimate faces, streets walked day by day, the house we live in – all these things are a part of us like our skin, and because we know them by heart we do not know them with the eye.’

The tree, the building, the colour of a road all become inconspicuous, not registering in our consciousness. We miss so much. Artists do not. They see with an ‘innocent eye’, as John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic, put it. They learn to unlearn: to see as if for the first time rather than the umpteenth. Tom’s dad did just that. He paid attention, focused his mind, and lived in the moment. He taught his son to see what he was missing. It is a gift that many other artists can give: to show us how to look at our world from a di erent perspective, and in so doing – over time – find our very own ‘beach stance’.

Before we meet them, a brief note on the book’s structure and my choices of artist. The starting point for each chapter is an extraordinary painter or sculptor. It might be a contemporary star like Jennifer Packer, or a prehistoric Mexican master – either way it is an artist I admire

whose highly developed powers of observation can prompt us to see the world afresh. In each case I focus on a single work to begin a journey into the artist’s mind and discover their unique way of looking, which, when applied to our own existence, stimulates our senses, heightens our perception, and encourages us to open our eyes fully.

Most people don’t look much. Looking is hard work. You’re always seeing more. That excites me. There’s beauty in everything, even a bag of rubbish. But you really have to look.

It is mid-January 2012. David Hockney is standing in the central gallery of the Royal Academy in London. He is seventy-four years old and is dressed in a loose-fitting grey suit, worn over a cream-coloured polo shirt, to which he has added a haphazardly arranged tie. If he were a door-to-door salesman you’d likely not answer his knock, but he is a famous contemporary artist and is therefore warmly welcomed wherever he goes.

He is looking at the far wall, on which hangs his colossal, billboard-sized painting The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire (2011). He turns to me and smiles. ‘Not a bad e ort, eh,’ he says in that slow, wry way of his. The Bradford-born artist is not fishing for compliments or indulging in self-a rmation. He is simply pleased with

how his thirty-two-canvas painting of the woods near his Bridlington home registers when hung on the grand, mushroom-coloured walls of the RA .

It is an unbelievable work of art. By which I mean, few who have ever been to Woldgate, East Yorkshire, and felt the icy wind from the North Sea cut them in half, would immediately recognize Hockney’s colourful account of his local wood. Not to begin with, at least. Violet trees and brilliant light? Come on! Soggy brown timber and slate grey skies more like. They talk of people seeing the world through rose-tinted glasses; David’s are on a permanent St-Tropez setting, where everything is lit up by an explosion of bright colours in a rapturous celebration of life.

Mention this to him and he stares at you with incredulity and says it is you who are wearing the reality-warping glasses, with huge blinkers to either side to stop you seeing what is actually there. ‘You haven’t really looked,’ he’ll say. People don’t – ‘they scan the ground in front of them so they can move around. Look longer at something, you’ll maybe see more.’ It’s a simple instruction that is not as easy as it sounds to carry out. Really looking is really di cult. There’s a lifetime’s worth of preconceptions to overcome, preconceptions that obscure. Trees are brown, their leaves are green, and paths are mudcoloured. That’s how it is, the fixed image from childhood most of us have in our heads, re-enforced by everything we’ve seen and done since. And then one day you see a painting such as The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East

Yorkshire which o ers a completely di erent view of reality and provokes you to look again.

I went to my local wood, and I stood and stared at the trees. They were brown, no doubt about it. And their leaves were green. And the path was mud-coloured. I could see none of Hockney’s psychedelic iridescence. But I had his encouraging words ringing in my ears, to be patient: ‘Trees are like faces, each is di erent. Nature doesn’t repeat itself. You have to observe closely, there is a randomness.’

Sure enough, as I peered at a gnarly old oak tree with a wide, leathery trunk, willing it to change colour in the spirit of a Hockney painting, a ray of sunlight washed across its contorted features. And there, before my eyes, its bark turned from a mid-brown to a burnt orange to a wonderful bruised purple! Its leaves had a similar chromatic awakening, their uniform green morphing into mellow yellows and silvery greys with little golden acorns glinting on their stems like jewels. The path was still a muddy brown, but then that’s like saying the Beatles were just a four-piece band. When given my full attention the path’s textured personality began to emerge, too. Soon, I could see dozens of di erent shades of brown along its surface, the shadows caused by its undulations creating speckles of red and pink and blue, transforming a once muddy mass into an intricate pattern like a mosaic floor in a Roman villa.

There is a view among some art historians that Hockney is not as accomplished a painter as he is a draughtsman

see what you’re missing

(Paul Klee spoke of taking a ‘line for a walk’: Hockney takes it for a dance). The late Brian Sewell, a British art critic, described the experience of visiting Hockney’s 2012 Royal Academy exhibition as ‘the visual equivalent of being tied hand and foot and dumped under the loudspeakers of the Glastonbury Festival’, a comment as vivid and colourful as the art he was excoriating. He thought the pictures gaudy, as in tacky and over the top. It is fair to say they are on the ebullient side, but they are not ostentatious. Not at all. They are rebellious, raucous, revolutionary: a root-and-branch reimagining of the landscape, a subject almost entirely ignored by recent generations of artists preoccupied with the mind games of conceptual art.

‘They said landscape is something you couldn’t do today,’ Hockney mused in an interview with the Van Gogh Museum, ‘and I thought, well, why? Because the landscape has become so boring? It’s not the landscape that’s become boring, it’s the depictions of it that have become boring. You can’t be bored of nature . . . can you?’

Hockney’s East Yorkshire paintings are in keeping with the high-key, Matisse-inspired work he made after leaving overcast England for sun-soaked California in the mid-60s, where he discovered radiant light and acrylic paints. His intention is to bring joy into a world of misery, which is about as uncool as you can get nowadays in the art world, where sneering cynicism is routinely rewarded and applauded. That’s not Hockney’s game. He is too self-confident to care about being

trendy. He is a non-conformist from the tip of his halfsmoked cigarette to the open toes of his leather sandals. It is his nature, it’s in his blood. When he was a boy, his father, Kenneth – who, as his art-loving son would later become, was a conscientious objector – encouraged David to be independently minded and intellectually curious. ‘Never pay attention to what the neighbours think,’ he said. Hockney never did.

He was an openly gay student at the Royal College of Art in the late 1950s and early 60s, when homosexuality was still illegal in Britain. The codified paintings he made back then under the influence of Jean Dubu et and Walt Whitman were audacious and subversive, cheekily tweaking the tail of a hidebound establishment. We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961) is the pick of the bunch, a saucy scene in a gra ti-walled lavatory rendered in oil on board. The two boys are the artist and either Cli Richard, Hockney’s favourite pop star pin-up, or a fellow student called Peter Crutch, on whom the artist had an unrequited crush. Either way, it was hot stu for the not yet swinging sixties. It was also a long way from the formal academic painting the RCA expected its students to pursue. The faculty took a similarly dim view of his work to the one expressed by Brian Sewell all those years later: they too dismissed it as substandard, and Hockney’s brushstrokes as attention-seeking daubs. Until, that is, Richard Hamilton – an avant-garde British artist whom they held in high esteem – dropped in and dished out an award to the young Hockney.

From the day he arrived at the RCA to his most recent pictures of the countryside of northern France, David Hockney has continually and compellingly explored new ways of seeing. He has dabbled in photography, set design, fax collages and photocopies. He has innovated on the iPad and toyed with perspective. He has produced etchings and made prints, presented television programmes on camera obscura, and produced multi-lens tracking shots of country roads. He has been here, there and everywhere in pursuit of one thing: the making of memorable pictures. Anybody can draw, most can paint, but very, very few can make impactful images that help us perceive afresh – images that penetrate our unconscious. Hockney can and does so frequently, which is testimony to his remarkable imagination and talent. His best pictures have a psychological charge, as is evident in his famous Los Angeles swimming-pool series of the 1960s and 70s. You could call it Neo-Impressionism: a fleeting moment distilled on to canvas to exist in perpetuity. Nowhere is his ability to capture the personal and transform it into the universal more evident than in the exceptional large double portraits he began painting in the late 60s.

Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970–71), a play on Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (c. 1750), is probably the most well-known of the series. It is a very good picture, but not his best. That was painted a year later. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) is the climactic apogee of the two themes for which he will

ultimately be remembered: the swimming-pool pictures and the double portraits. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) came to global prominence in 2018 when it broke the then auction record for a living artist, selling at Christie’s for $90 million.

Its asymmetrical, geometric design is meticulously arranged, with every element carefully balanced and counterbalanced. A man in a pink jacket stands at the edge of the rectangular pool and looks down through the water to another man in white trunks swimming beneath the surface. They are separated by axis and environment, so close yet existing in two di erent dimensions. The standing man (modelled on Hockney’s ex-lover Peter Schlesinger) is full of longing. The swimmer (Hockney?) is oblivious to his presence – any feelings he has are literally and metaphorically kept beneath the surface. What has happened? What will happen? The artist has thrown us in at the deep end with little to hold on to. There’s only one option: to wait for this silent picture to speak.

On the warm air breezing over from the triangular hills in the distance come whispers of a story of love and loss, of heartbreak and sorrow, of redemption and friendship, of paradise and beauty. It is a terrific picture, recalling Piero della Francesca’s division of space and time in The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1455), and Fra Angelico’s two-figure masterpiece The Annunciation (c. 1438–47). I could list another twenty artists – from Edward Hopper to Francis Bacon – whose work echoes in this painting. But there is

only one person who could have created it: David Hockney, from whose hand, eye and heart it comes.

It is di erent from his later landscape paintings in style and approach. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) was not made with Hockney standing in front of his subject, but by combining two random photographs he found on his studio floor – one of a submerged figure swimming, the other of a boy peering at the ground beneath his feet. It is largely a work assembled in his imagination with the help of research photos taken in Europe.

The scene as presented to us never happened, but the elements that make up its constituent parts are all based on real experiences: Hockney’s holiday in the hills of the South of France, his Californian swimmingpool, a trip to a London park with Peter. The painting represents a collection of memories capturing the reality of a moment in the artist’s life when he parted from his lover. Months have been distilled into a single fabricated image that is disarmingly honest. Hockney is showing us that the act of seeing isn’t always about focusing on a specific subject at a specific time in a specific place. Sometimes to really see requires gathering together multiple visual sources that can be boiled down into a single, revealing composite image, which can say more than all the others in isolation.

It is a picture-making technique into which Hockney invested a great deal of time and energy. As with everything he does, it is centred on his obsession with looking

properly . He would use a camera to take dozens of photographs of the same person or object from every conceivable angle. He would scale ladders and crawl along the ground to make sure that he had seen everything. Only when he was satisfied he had fully interrogated his subject would he begin to piece together a fragmented artwork made up from the multiple images.

These patchwork creations shared the same essential truth found in Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures): everything we see is in context. Our two eyes immediately provide two points of view, we crane our necks to create a third and a fourth – and then we move a little. Within seconds we have undertaken a complex visual analysis of our subject. This is the reality Hockney is giving us in his composite pictures. That is why they ring true, it is what gives them their psychological power. They are not simply paintings of people and places, they are reflections on the reality of how we see.

David Hockney is in his mid-eighties now, hard of hearing and far from his physical peak. But his mind and eyes are as sharp as ever. As is his ability to see splendour in the everyday. During the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic he sent me some joyous images he had produced of his blossoming spring garden in Normandy, France. I asked if I could post them on the BBC website. He acquiesced. Within hours millions of people had seen them, many thanking the artist for producing images bursting with life and hope at such an unsettling time. Among them was a picture of da odils, to which

he gave the title Do Remember They Can’t Cancel the Spring, a satirical comment on the global lockdown and nature’s glorious indi erence. It was typical of Hockney and his optimistic, idiosyncratic way of viewing the world. The yellow-headed da odils are the size of trees in the foreground, dominating the purple hills in the distance. They appear to move in front of your eyes like a chorus line in a 1920s Parisian nightclub, swinging their limbs in time to the tune of spring. Where you or I might see a pleasant bunch of seasonal flowers, he observes nature at her dramatic best – full of irrepressible life and resplendent in brilliant colour. He has taken the time to have a proper look, not give a cursory glance, his investment handsomely repaid by the revelation of transcendent beauty. It is all the evidence you need to know that there is much to be gained from taking his advice to ‘look longer’.

Boats sail on the rivers, And ships sail on the seas; But clouds that sail across the sky Are prettier far than these.

– Christina Rossetti, ‘The Rainbow’Clouds are like estate agents, they get a bad rap. They are forever being used as the default metaphor for negative situations. If things aren’t looking too good – there’s a cloud on the horizon, or, if more ominous, the storm clouds are gathering. Unable to think clearly? Something must be clouding your judgement. Look guilty and you’ll be under a cloud of suspicion. Lose all your digital data and you’re sure to blame the Cloud. The only good thing about a cloud is its silver lining, but that’s not a cloud, it’s the sun glinting behind. The sun is the good guy, the cloud is an obstructive nuisance.

We are indoctrinated with this downbeat attitude towards clouds. They are the villains in the daily weather report. Sunny days are ‘beautiful’, cloudy days are ‘miserable’. And that is not good if you happen to live in

England, as I do. It means the majority of the year is spent struggling through one grey-day downer after another, with a couple of weeks of respite in August when the sun is so hot you can’t go outside.

That’s life, or so I thought. But then, one cloudy day, I found myself in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (avoiding the overcast weather outside) and came across a sketch by the English romantic painter John Constable (1776–1837). It was a mid-size (48cm x 59cm) landscape painted on paper, dated 1822, and was quite unlike any other depiction of nature I’d seen previously. There were no trees or rivers or fields or hills. In fact, there was no land at all. Or sea. Only sky. An English sky. A cloudy sky! A sky dense with those infamous amorphous blobs containing water and ice crystals. A sky that had been looked at millions of times before but never observed and recorded with the insight of this wealthy miller’s son.

Constable’s clouds weren’t doomy or gloomy, they were beautiful and voluptuous and full of character. His was a skyscape of billowing shapes as joyful and carefree as hippies at a music festival. It was like sitting next to an acquaintance you had always thought a dreadful bore only to discover them to be the best company in the room. It was a strange experience, seeing something so familiar – a cloudy sky – at the same moment as seeing something for the first time – a painting of nothing but a cloudy sky. From that day to this, I see the world di erently. Constable’s clouds transformed my relationship

with overcast days: what was once dull has become marvellous. I now look up into a cloudy sky, not glumly but curiously, to see nature’s ever-changing exhibition of ‘sky sculptures’.

Constable painted clouds of every shape and size, from sun-infused clusters of plump clouds to moody intermingling tones of white and black, or grey and blue, and even pink and brown. Many of his ‘skyscapes’ look like the kind of Abstract Expressionist image Willem de Kooning or Jackson Pollock might have conjured up in a New York studio well over a century later. But Constable wasn’t dealing in the transcendental. He’s not attempting to communicate a suppressed emotion or a hidden meaning, as was the case with De Kooning and Pollock. He was painting what he saw. Truth to nature was his mission – he was a realist, an empiricist. He made this abundantly clear in a lecture at the Royal Institution in 1836 when he said:

Painting is a science and should be pursued as an inquiry into the laws of nature. Why, then, may not a landscape be considered as a branch of natural philosophy, of which pictures are but experiments?

Constable wanted to activate our consciousness, to get us to see what was in plain sight but routinely overlooked. Overlooked not just by us but also by his fellow artists, who, Constable argued, were hoodwinking the public with fabricated images containing stereotypical classical allusions that bore no resemblance to reality.

He didn’t hold back in his assessment of his peers past and present:

And however one’s mind may be elevated, and kept up to what is excellent, by the works of the Great Masters – still Nature is . . . whence all originality must spring – and should an artist continue his practice without referring to nature he must soon form a manner, & be reduced to the same deplorable situation as the French painter . . . who . . . had long ceased to look at nature for she only put him out. For the two years past I have been running after pictures, and seeking the truth at second hand.

Constable’s answer was to leave the sanctuary of the studio and the conventions of academic tradition, where historical, mythological and religious subjects were considered the most appropriate for a painting. Instead, he took his oil paints outside to record the view before him. It was a radical act for the time, only made possible by his portable ‘sketching box’ containing brushes, glass vials full of pigment and medium, and pre-mixed paint stored in pigs’ bladders. It allowed him to set up shop and paint ‘in nature’, or ‘en plein air’, a technique supposedly invented by Monet and his Impressionist friends fifty years later. Those French revolutionaries of modern art owe a lot to Constable. Not least, to his dedication to meticulously observing nature first-hand, and the trouble he took to record accurately what he saw, from a tiny detail on a leaf to the atmospheric e ects of the ever-changing light.

The potency of his Study of Clouds lies in its veracity. The subject is instantly recognizable: the inherent beauty of an everyday phenomenon, which most of us blithely disregard. Here was an artist of extraordinary talent showing us what we were missing, or worse – dismissing.

As far as Constable was concerned, clouds were stimulating and intoxicating in a way a clear blue sky was not, an opinion that was far from universal. In the early 1820s the Bishop of Salisbury, a friend and supporter of the artist, commissioned him to paint a view of his cathedral in south-west England. Constable did as he was asked and in due course proudly presented a splendid painting of the great gothic building, framed by two trees between which its magnificent spire rose as if divine into an evocative, moody skyscape. Constable was thrilled with his work. His friend, the bishop, was not. He took one look at the picture before summarily rejecting it and asking Constable to make another version, but this time with a sunny, cloudless sky!

Annoying, for sure, but that’s the way it goes if you’re a pioneering artist – it takes a while for everybody else to catch up. Constable’s attitude to picture-making was radically di erent from the accepted norm. Even his celebrated competitor, the daring J. M. W. Turner, was lagging behind John C. from East Bergholt. Turner continued to follow in the footsteps of the revered French Baroque artist Claude Lorrain (whom Constable also greatly admired), by embellishing his landscapes with mythical figures and ancient ruins, and prioritizing fixed

compositional conventions over depicting reality. This way his grand canvases could be considered history paintings, a genre that enjoyed a status far higher than down-to-earth landscape painting. Constable disagreed with the Academy’s hierarchy, saying, ‘They prefer the shaggy posterior of a satyr than a true feeling for nature.’ His response was to go large. If history paintings were admired for being expansive and grand, why not give landscapes the same epic treatment. Instead of obeying the rules and producing tea-tray size images of rural life, Constable started to paint what he called his ‘sixfooters’ – massive 6ft x 6ft (1.8m x 1.8m) canvases: pictures so large and realistic that viewers didn’t simply look, they entered them.

The Hay Wain (1821) is his most famous six-footer, a work he made around the same time as the Ashmolean’s Study of Clouds. It is loved for its timelessness and charm; for the way Constable has captured the Su olk scene with a rugged honesty. The rendering of the leaves on the trees and of the light playing on the water are rightly considered masterful. People talk about the eye-catching red of the horses’ saddlebags, and the dog at the river’s edge. They admire the composition, and marvel that the view remains largely unchanged today. But what rarely gets mentioned is the most accomplished element of the painting, the clouds.

Constable shows us the brilliant radiance and pu y texture of a cumulonimbus, the wispiness of a cirrus, and the omnipresent proximity of a stratus. He brings

us their e ervescence, aligned to a sense of drama inherent in the interplay of the dispersed sunlight in a constantly changing scene. So much better than a cloudless sky when the sun has such a monotonous and lonely job, which is to amble from east to west. A bit boring. Unlike when the clouds blow in. Then the sun has a fabulous time as Director of Ceremonies of life on earth. There is a theatricality to the constantly moving light and shade skipping across the land below as a cast of clouds go through their shape-shifting exercises, all the while being backlit by a sun slowly panning over them like the camera in a Tarkovsky movie.

The Hay Wain is more than a painting documenting country life, it is ultimately a study of light.

That landscape painter who does not make his skies a very material part of his composition, neglects to avail himself of one of his greatest aids. [Skies] must and always shall with me make an e ectual part of the composition. It will be di cult to name a class of landscape, in which the sky is not the ‘key note’, the ‘standard of scale’, and the chief ‘organ of sentiment’. The sky is the ‘source of light’ in nature – and governs everything.

Constable’s interest in weather patterns and the e ects of clouds on our perception went beyond a painterly enquiry. He was alive at a time when rational truths of science were challenging the long-held beliefs of religion. It was the Age of Enlightenment, when human knowledge began to usurp Divine Provenance. Travelling

academics gave lectures across the country; science was the new religion. The Meteorological Society of London was founded, and the first books classifying the various types of cloud were published. Constable read these books avidly, making notes in the margins, many of which were his annotated corrections to what he considered factual errors in the original text.

Study of Clouds is an example of how seriously he took his investigations into matters meteorological. He’d talk to friends about his love of ‘skying’, when he would sit outside and quickly sketch a never-to-be-repeated cloudscape, which he would duly date and note with time of day along with a short commentary on the prevailing conditions. His purpose was to undertake research, not to make art. He probably never intended his cloud sketches to end up in museums and galleries – they were preparatory enquiries to be used as source material for future landscape paintings, such as The Hay Wain.

He produced the majority of his cloud studies while living in Hampstead, where he had moved in 1819 from his beloved Su olk with his dear wife Maria, because she was su ering from ill-health (the early symptoms of tuberculosis, from which she would die in 1828). Doctors advised the couple that Maria would benefit from the elevated position of what was then a leafy, rural village to the north of London. They moved into Albion Cottage on the edge of the Heath, which o ered John wonderful, far-reaching views. It is where he learnt so much about light, and he would go on to make this most