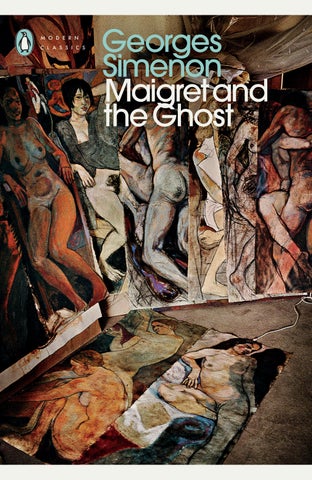

‘Extraordinary masterpieces of the twentieth century’

– John Banville

‘A brilliant writer’ – India Knight

‘Intense atmosphere and resonant detail . . . make Simenon’s fiction remarkably like life’

– Julian Barnes

‘A truly wonderful writer . . . marvellously readable – lucid, simple, absolutely in tune with the world he creates’

– Muriel Spark

‘Few writers have ever conveyed with such a sure touch, the bleakness of human life’

‘Compelling, remorseless, brilliant’

– A. N. Wilson

– John Gray

‘A writer of genius, one whose simplicity of language creates indelible images that the florid stylists of our own day can only dream of’ – Daily Mail

‘The mysteries of the human personality are revealed in all their disconcerting complexity’

– Anita Brookner

‘One of the greatest writers of our time’ – The Sunday Times

‘I love reading Simenon. He makes me think of Chekhov’

– William Faulkner

‘One of the great psychological novelists of this century’

– Independent

‘The greatest of all, the most genuine novelist we have had in literature’

– André Gide

‘Simenon ought to be spoken of in the same breath as Camus, Beckett and Kafka’

– Independent on Sunday

Georges Simenon was born on 12 February 1903 in Liège, Belgium, and died in 1989 in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he had lived for the latter part of his life. Between 1931 and 1972 he published seventy- five novels and twenty- eight short stories featuring Inspector Maigret. Simenon always resisted identifying himself with his famous literary character, but acknowledged that they shared an important characteristic:

My motto, to the extent that I have one, has been noted often enough, and I’ve always conformed to it. It’s the one I’ve given to old Maigret, who resembles me in certain points . . . ‘Understand and judge not’.

Translated by ROS SCHWARTZ

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK

One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7 BW penguin.co.uk

First published in French as Maigret et le fantôme by Presses de la Cité 1964

This translation fi rst published 2018

Published in Penguin Classics 2025 001

Copyright © Georges Simenon Limited, 1964

Translation copyright © Ros Schwartz, 2018

GEORGES SIMENON and ® , all rights reserved

MAIGRET ® Georges Simenon Limited, all rights reserved original design by Maria Picassó i Piquer

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright.

Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–30403–7

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

1. Inspector Lognon’s Strange Nights and Solange’s Ailments 1

2. Lunch at Chez Manière 23

3. Marinette’s Love Affairs 43

4. The Visit to the Dutchman 64

5. The Room Covered in Graffiti 85

6. The Barefoot Drunkard 109

7. Mirella’s Choice 131

It was just after one o’clock in the morning when the light went out in Maigret’s office. Puffy-eyed with tiredness, Maigret pushed open the door to the inspectors’ office, where young Lapointe and Bonfils were on duty.

‘Good night, boys,’ he grunted.

In the vast corridor the cleaning women were sweeping the floor, and he gave them a little wave. As always at that hour, there was a draught, and the staircase he descended in the company of Janvier was damp and freezing.

This was mid-November and it had rained all day. Maigret hadn’t left the stiflingly hot atmosphere of his office since eight o’clock the previous morning. Before crossing the courtyard, he turned up the collar of his overcoat.

‘Shall I drop you off somewhere?’

A taxi, ordered by telephone, was stationed in front of the entrance to Quai des Orfèvres.

‘At any Métro station, chief.’

It was pouring down, the rain bouncing off the pavements. Janvier got out of the car at Châtelet.

‘Good night, chief.’

‘Good night, Janvier.’

It was a moment like so many others they had shared, and they both felt the same slightly weary sense of satisfaction.

A few minutes later, Maigret noiselessly climbed the stairs up to his apartment in Boulevard Richard-Lenoir, fumbling in his pocket for his key. He turned it quietly in the lock, and almost at once heard Madame Maigret stir in bed.

‘Is that you?’

She had asked that same question sleepily hundreds, if not thousands, of times when he came home in the middle of the night, groping for the bedside light and then getting up in her nightdress and glancing at her husband to gauge his mood.

‘Is it over?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did the boy talk in the end?’

He nodded.

‘Are you hungry? Do you want me to make you something to eat?’

He had hung up his wet overcoat on the coat-stand and was loosening his tie.

‘Is there any beer in the refrigerator?’

He had almost stopped the car at Place de la République to down a beer in a brasserie that was still open.

‘Did it turn out to be what you thought?’

A run-of-the-mill affair, as much as a case implicating several people can be described as run-of-the-mill. The newspapers had dubbed them ‘The Bike Gang’.

The first time, two motorbikes had pulled up in front of a jeweller’s in Rue de Rennes in broad daylight. Two men had jumped off one, and a third off the other, their faces masked with red bandanas. All three had dashed into

the shop and emerged minutes later, brandishing guns, with jewels and watches snatched from the window and the counter.

In the heat of the moment, the bystanders had been numb with shock, and when motorists eventually reacted and thought to give chase to the thieves, it had caused such a traffic jam that the culprits were able to get away.

‘They’ll strike again,’ Maigret had predicted.

The haul was meagre, because the jeweller’s, owned by a widow, only sold cheap goods.

‘They wanted to perfect their technique.’

This was the first time that motorbikes had been used in a hold-up.

Maigret was not mistaken, because three days later the scenario was repeated, this time in a luxury jeweller’s in Faubourg Saint-Honoré. The result was the same, only this time the bandits had looted jewellery worth several million old francs, two hundred million according to the newspapers, one hundred said the insurance company.

But, as they made their getaway, one of the robbers had lost his bandana and he had been arrested two days later at the locksmith’s where he worked, in Rue Saint-Paul.

By that evening all three were behind bars, the eldest aged twenty-two and the youngest, Jean Bauche, nicknamed Jeannot, just eighteen.

He was blond, his hair too long, and was the son of a cleaning woman in Rue Saint-Antoine. He too worked in a locksmith’s.

‘Janvier and I took turns all day,’ an irritable Maigret told his wife.

Drinking beer and eating sandwiches.

‘Listen, Jeannot. You think you’re a tough guy. They had you believe you were. But it was neither you nor your little friends who planned those robberies. There’s someone behind you, someone who orchestrated the whole thing, taking care not to get his hands dirty. He was released from Fresnes two months ago and isn’t keen to go back to prison. Admit he was at the scene, in a stolen car, and that he covered your getaway by faking a clumsy manoeuvre and holding up the traffic . . .’

Maigret undressed, taking the occasional sip of beer, bringing his wife up to date in terse sentences.

‘Those kids are the toughest . . . They have a very strong code of honour instilled into them . . .’

He’d had three repeat offenders arrested, including a certain Gaston Nouveau. As was to be expected, he had a watertight alibi; two people had stated that, at the time of the heist, he’d been in a bar in Avenue des Ternes.

For hours, the questioning had stalled. Plump Victor Sidon, nicknamed ‘Granny’, the eldest of the three bikers, looked at Maigret contemptuously. Saugier, known as ‘Banger’, cried, swearing he knew nothing.

‘Janvier and I concentrated our efforts on young Bauche. We had his mother brought in, and she begged him:

‘ “Talk, Jeannot! You can see that these gentlemen aren’t after you. They know you let yourself be led astray . . .” ’

Twenty unpleasant hours, relentlessly pushing a kid to the limits of human resistance. It wasn’t pleasant either to see him suddenly crack.

‘ “All right! I’ll tell you everything. Yes, it was Nouveau

who approached us at the Lotus and who got us involved in the racket . . .” ’

A little bar in Rue Saint-Antoine, where young boys and girls went to listen to the jukeboxes.

‘ “Because of you, when I get out of prison, he’ll have me killed by his friends . . .” ’

That was all! Another day done. Maigret went to bed, his head throbbing.

‘What time do you have to be at the office?’

‘Nine o’clock.’

‘Can’t you sleep in a little?’

‘Wake me up at eight.’

There was no transition to speak of. He didn’t feel as if he’d slept. No sooner had he closed his eyes, it seemed, than the doorbell was ringing and his wife slipping out of bed to go and answer it.

There was whispering in the hallway. He thought he recognized the voice, told himself he must be dreaming and buried his head under the pillow.

Again, his wife’s footsteps padding towards the bed. Was she going to go back to sleep? Had someone rung the wrong bell? No. She touched his shoulder, drew back the curtains and, without needing to open his eyes, he was aware that it was daylight. He asked in a slurred voice:

‘What time is it?’

‘Seven o’clock.’

‘Is someone here?’

‘Lapointe’s waiting for you in the dining room.’

‘What does he want?’

‘I don’t know. Stay in bed for a minute while I make you a cup of coffee.’

Why was his wife talking to him as if she’d just been given bad news? Why had she been loath to answer his question? It was a filthy grey day and the rain was still coming down.

Initially Maigret thought that Jean Bauche, thrown into a panic by his confession, had hanged himself in his police cell. He got up without waiting for his coffee, pulled on his trousers, ran a comb through his hair and opened the dining-room door, still groggy from too deep a sleep.

Lapointe stood by the window, wearing a black overcoat and holding a dark-coloured hat, his cheeks covered in stubble after a night on duty.

Maigret merely gave him a quizzical look.

‘I apologize for waking you up so early, chief . . . Something happened last night, to someone you’re fond of . . .’

‘Janvier?’

‘No . . . Not someone from Quai des Orfèvres . . .’

Madame Maigret brought in two large cups of coffee.

‘Lognon . . .’

‘Is he dead?’

‘Seriously wounded. He was taken to Bichat and Monsieur Mingault, the consultant, has been operating on him for the last three hours . . . I didn’t want to come sooner, or telephone you, because, after the day you’d had yesterday, you needed some rest . . . Besides, at first, they didn’t think there was much chance that he’d live . . .’

‘What happened to him?’

‘Two bullets, one in the stomach, the other just below the shoulder.’

‘Where?’

‘Avenue Junot, on the pavement.’

‘Was he alone?’

‘Yes. For the time being, it’s his colleagues from the eighteenth arrondissement who are investigating.’

Maigret sipped his coffee without experiencing the usual satisfaction.

‘I thought you’d want to be there if he regains consciousness. The car’s downstairs . . .’

‘Do they know anything about the attack?’

‘Almost nothing. They don’t even know what he was doing in Avenue Junot. A concierge heard the shots and called the emergency services. A bullet went through her shutter, smashed the windowpane and lodged itself in the wall above her bed.’

‘I’ll get dressed.’

He went into the bathroom while Madame Maigret set the table for breakfast and Lapointe, having removed his overcoat, waited.

Inspector Lognon didn’t belong to Quai des Orfèvres, even though he was keen to, but Maigret had worked with him often, almost every time there was a major case in the eighteenth arrondissement.

He was a civvy, as they said, one of the twenty plainclothes inspectors whose office was in the Montmartre town hall, on the corner of Rue Ordener and Rue du Mont- Cenis.

Some called him Inspector Hard-Done-By because of

his sullen expression. But Maigret called him Inspector Luckless, and it did indeed seem as if poor old Lognon had a talent for attracting misfortune.

Short and scrawny, he had a permanent cold which gave him a red nose and the watery eyes of a drunkard, even though he was probably the soberest man in the police force.

He was afflicted with a sick wife, who dragged herself from her bed to an armchair by the window. When he was off duty, Lognon had to manage the housework, the shopping and the cooking. He could just about afford to pay a woman to come once a week to do the heavy cleaning.

On four occasions he had sat the Police Judiciaire entrance exam, and he’d failed each time because of careless mistakes, whereas he was in fact an outstanding police officer, a sort of bloodhound who, once on a trail, would not give up. Obstinate. Meticulous. The type who could immediately smell something suspicious passing someone in the street.

‘Do they hope to save him?’

‘At Bichat they reckon he has a thirty per cent chance, apparently.’

For a man nicknamed Inspector Luckless, that was not encouraging.

‘Has he been able to speak?’

Maigret, his wife and Lapointe ate the croissants which the baker’s boy had just left outside the door.

‘His colleagues didn’t tell me, and I didn’t want to press them.’

Lognon wasn’t the only one to suffer from an inferiority complex. Most of the neighbourhood inspectors coveted a post at Quai des Orfèvres and, when they had an interesting case likely to make the headlines, they hated the ‘big boys’ taking it away from them.

‘Let’s go!’ sighed Maigret, putting on his overcoat, which was still damp.

His gaze met his wife’s, and he understood that she wanted to speak to him, guessing that the same idea had just occurred to both of them.

‘Do you expect to be back for lunch?’

‘It’s unlikely.’

‘In that case, don’t you think . . . ?’

She was thinking of Madame Lognon, helpless and alone at home.

‘Get dressed quickly! We’ll drop you off at Place Constantin-Pecqueur.’

The Lognons had lived there for twenty years, in a redbrick apartment building with yellow bricks surrounding the windows. Maigret had never been able to remember the street number.

Lapointe took the wheel of the little Police Judiciaire car. This was the second time in so many years that Madame Maigret had got into one of these with her husband.

They drove past crammed buses. On the pavements, people walked fast, leaning forward, clutching their umbrellas, which the wind was trying to snatch from their hands.

They reached Montmartre, Rue Caulaincourt.

‘It’s here . . .’