‘Extraordinary masterpieces of the twentieth century’

– John Banville

‘A brilliant writer’

– India Knight

‘Intense atmosphere and resonant detail . . . make Simenon’s fiction remarkably like life’

– Julian Barnes

‘A truly wonderful writer . . . marvellously readable – lucid, simple, absolutely in tune with the world he creates’

– Muriel Spark

‘Few writers have ever conveyed with such a sure touch, the bleakness of human life’

‘Compelling, remorseless, brilliant’

– A. N. Wilson

– John Gray

‘A writer of genius, one whose simplicity of language creates indelible images that the florid stylists of our own day can only dream of’ – Daily Mail

‘The mysteries of the human personality are revealed in all their disconcerting complexity’

– Anita Brookner

‘One of the greatest writers of our time’ – The Sunday Times

‘I love reading Simenon. He makes me think of Chekhov’

– William Faulkner

‘One of the great psychological novelists of this century’

– Independent

‘The greatest of all, the most genuine novelist we have had in literature’

– André Gide

‘Simenon ought to be spoken of in the same breath as Camus, Beckett and Kafka’

– Independent on Sunday

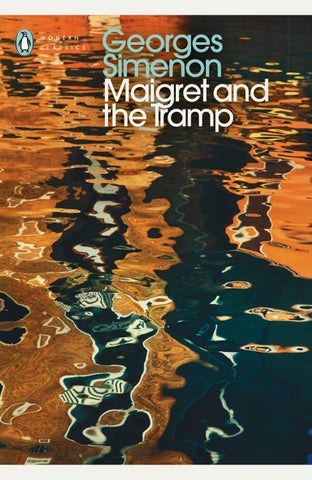

Georges Simenon was born on 12 February 1903 in Liège, Belgium, and died in 1989 in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he had lived for the latter part of his life. Between 1931 and 1972 he published seventy- five novels and twenty- eight short stories featuring Inspector Maigret. Simenon always resisted identifying himself with his famous literary character, but acknowledged that they shared an important characteristic:

My motto, to the extent that I have one, has been noted often enough, and I’ve always conformed to it. It’s the one I’ve given to old Maigret, who resembles me in certain points . . . ‘Understand and judge not’.

Translated by HOWARD CURTIS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK

One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7 BW penguin.co.uk

First published in French as Maigret et le clochard by Presses de la Cité 1963

This translation fi rst published 2018

Published in Penguin Classics 2025 001

Copyright © Georges Simenon Limited, 1963

Translation copyright © Howard Curtis, 2018

GEORGES SIMENON and ® , all rights reserved

MAIGRET ® Georges Simenon Limited, all rights reserved original design by Maria Picassó i Piquer

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright.

Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–30399–3

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

There was a moment, between Quai des Orfèvres and Pont Marie, when Maigret paused, so briefly that Lapointe, who was walking beside him, paid no attention. And yet, for a few seconds, perhaps only a split second, Maigret had been taken back to when he was his companion’s age. It was doubtless something to do with the quality of the air, its luminosity, its smell, its taste. There had been a morning just like this, mornings just like this, in the days when, as a young inspector newly appointed to the Police Judiciaire, which Parisians still called the Sûreté, Maigret worked the beat, tramping the streets of Paris from morning to night.

Although it was already 25 March, this was the first real day of spring, all the more limpid for the fact that there had been a last shower during the night, accompanied by distant rolls of thunder. It was also the first time in the year that Maigret had left his overcoat in his office cupboard, and from time to time the breeze caused his unbuttoned jacket to billow.

Because of this whiff of the past, he had, without realizing it, adopted his old pace, neither slow nor fast, not quite the pace of someone out for a stroll and stopping to look at the minor sights of the street, nor quite that of someone with a particular purpose in mind.

His hands together behind his back, he looked around him, right, left, up in the air, registering images to which he had not paid any attention for a long time.

For such a short journey, there had been no question of taking one of the black cars lined up in the courtyard of the Police Judiciaire, and the two men were walking by the river. Pigeons flew off as they crossed the square in front of Notre-Dame, where there was already a tourist coach, a big yellow coach from Cologne.

Crossing the iron footbridge, they reached Ile SaintLouis. In a window, Maigret noticed a young chambermaid in a uniform and a white lace cap, like something from a boulevard comedy. A little further on, a butcher’s boy, also in uniform, was delivering meat; a postman was just coming out of an apartment building.

The buds had opened that very morning, dappling the trees with soft green flecks.

‘The Seine’s still high,’ Lapointe remarked. It was the first thing he had said.

It was true. For a month now, it had barely stopped raining, and then only for a few hours. Almost every evening, the television showed swollen rivers and towns and villages with flooded streets. The water of the Seine was yellowish, and carried all kinds of litter, old crates, tree branches along with it.

The two men followed Quai de Bourbon as far as Pont Marie, which they crossed at the same calm pace. Downstream, they could see a greyish barge with the white and red triangle of the Compagnie Générale on its bow. Its name was the Poitou, and a crane was unloading sand

from its hold, with a wheezing and creaking that mingled with the indistinct noises of the city.

Another barge was moored upstream of the bridge, some fifty metres from the first. It looked cleaner, as if it had been polished that very morning. A Belgian flag fluttered lazily in the stern. Near the white cabin, a baby lay asleep in a hammock-shaped canvas cradle. A very tall man with light-blond hair was looking in the direction of the riverbank, as if waiting for something.

The name of the boat, in gold letters, was De Zwarte Zwaan, a Flemish name, which neither Maigret nor Lapointe understood.

It was two or three minutes to ten. The two police officers reached Quai des Célestins. As they descended the ramp to the quayside, a car drew up, and three men got out, slamming the door.

‘Ah, we’ve arrived at the same time!’

They, too, had come from the Palais de Justice, but from the more imposing part reserved for magistrates. There was Deputy Prosecutor Parrain, Examining Magistrate Dantziger and an old clerk of the court whose name Maigret could never remember, even though he had met him hundreds of times.

It wouldn’t have occurred to the passers-by on their way to work or the children playing on the pavement opposite that this was an official visit by the prosecutor’s office. In the bright morning, there was nothing at all solemn about it. The deputy prosecutor took a gold cigarette case from his pocket and mechanically held it out to Maigret, even though he had his pipe in his mouth.

‘Oh, of course, I forgot . . .’

He was a tall, thin, fair-haired man, quite distinguishedlooking; it struck Maigret once again that this was characteristic of the prosecutor’s office. As for Dantziger, who was short and round, he was plainly dressed. Examining magistrates came in all shapes and sizes. So why did those from the prosecutor’s office all look more or less like senior civil servants, with manners, elegance and often arrogance to match?

‘Shall we go, gentlemen?’

They walked down the ramp with its uneven cobbles, and came to the quayside, not far from the barge.

‘Is this the one?’

Maigret knew no more than they did. He had read in the daily reports a brief account of what had happened during the night and had received a telephone call half an hour earlier, asking him to be present when the prosecutor’s men arrived.

He didn’t mind. He was back in a world, an atmosphere he had experienced on several occasions. All five men advanced towards the motor barge, which was linked to the quayside by a gangplank, and the tall fair-haired bargee took a few steps towards them.

‘Give me your hand,’ he said to the deputy prosecutor, who was the first in line. ‘To be on the safe side, right?’

His Flemish accent was pronounced. His clear-cut features, his pale eyes, his big arms, his way of moving recalled his country’s cyclists being interviewed after a race.

The noise of the crane unloading the sand was louder here.

‘Is your name Joseph Van Houtte?’ Maigret asked, after glancing at a piece of paper.

‘Jef Van Houtte, yes, monsieur.’

‘Are you the owner of this boat?’

‘Of course I’m the owner, monsieur, who else would be?’

A pleasant smell of cooking rose from the cabin, and at the foot of the staircase, which was covered in flowerpatterned linoleum, a very young woman could be seen coming and going.

Maigret pointed to the baby in its cradle.

‘Is that your son?’

‘Not my son, monsieur, my daughter. Yolande, her name is. My sister’s name is also Yolande, she’s her godmother.’

Signalling to the clerk of the court to take notes, Deputy Prosecutor Parrain now decided to intervene.

‘Tell us what happened.’

‘Well, I fished him out, and the skipper on the other boat helped me.’

He pointed to the Poitou, in whose stern a man stood leaning against the helm, looking in their direction as if awaiting his turn.

A tugboat sounded its siren several times and passed slowly upstream with four barges behind it. Each time one of them came level with the Zwarte Zwaan, Jef Van Houtte raised his arm in greeting.

‘Did you know the drowning man?’

‘I’d never even seen him before.’

‘How long have you been moored here?’

‘Since last night. I’ve come from Jeumont, with a cargo

of slates for Rouen. I was planning to go through Paris and stop for the night at the Suresnes lock. I suddenly noticed that something was wrong with the engine . . . We don’t especially like spending the night in the middle of Paris, if you know what I mean.’

In the distance, Maigret saw two or three tramps standing under the bridge, among them a very fat woman he had the feeling he had seen before.

‘How did it happen? Did the man jump in the water?’

‘I don’t think so, monsieur. If he’d jumped in the water, what would the other two be doing here?’

‘What time was it? Where were you? Tell us precisely what happened during the evening. You moored here just before nightfall?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Did you notice a tramp under the bridge?’

‘You don’t notice these things. They’re almost always there.’

‘What did you do then?’

‘We all had dinner, Hubert, Anneke and me.’

‘Who’s Hubert?’

‘My brother. He works with me. Anneke’s my wife. Her name’s Anna, but we call her Anneke.’

‘And then?’

‘My brother put on his nice suit and went dancing. At his age, why not?’

‘How old is he?’

‘ Twenty-two.’

‘Is he here?’

‘He went to buy supplies. He’ll be back.’

‘What did you do after dinner?’

‘I went to work on the engine. I saw right away that there was an oil leak, and as I was planning to leave in the morning I did the repairs.’

He kept darting suspicious glances at each of them in turn, like someone who isn’t used to having dealings with the law.

‘When did you complete the work?’

‘I didn’t. I only finished it off this morning.’

‘Where were you when you heard the shouting?’

He scratched his head, looking straight ahead at the spacious, gleaming deck.

‘First, I came up on deck once to smoke a cigarette and see if Anneke was asleep.’

‘What time was that?’

‘About ten. I’m not entirely sure.’

‘Was she asleep?’

‘Yes, monsieur. And the baby was asleep, too. There are nights when she cries, because she’s teething.’

‘Did you go back to your engine?’

‘Of course.’

‘Was the cabin dark?’

‘Yes, monsieur, since my wife was asleep.’

‘The deck as well?’

‘Definitely.’

‘What happened next?’

‘A long time afterwards, I heard the noise of a car engine, as if someone had parked not far from the boat.’

‘Did you go and see?’

‘No, monsieur. Why would I?’

‘Go on.’

‘A bit later, there was a splash.’

‘As if someone had fallen in the river?’

‘Yes, monsieur.’

‘What did you do then?’

‘I went up the ladder and put my head out through the hatch.’

‘What did you see?’

‘Two men running to the car.’

‘So there was a car?’

‘Yes, monsieur. A red car. A Peugeot 403.’

‘It was bright enough for you to make it out?’

‘There’s a street lamp just above the wall.’

‘What did the two men look like?’

‘The shorter one was broad-shouldered and was wearing a light-coloured raincoat.’

‘What about the other one?’

‘I didn’t see him very well because he was the first to get in the car. He immediately started the engine.’

‘Did you see the registration number?’

‘The what?’

‘The number on the licence plate?’

‘I only know there were two 9s and it ended in 75.’

‘When did you hear the yelling?’

‘When the car got going.’

‘In other words, a certain amount of time passed between the moment the man was thrown in the water and the moment he started yelling? Otherwise, you would have heard him earlier?’

‘I suppose so, monsieur. It’s quieter at night than it is now.’

‘What time was this?’

‘After midnight.’

‘Was there anyone walking on the bridge?’

‘I didn’t look up.’

Above the wall, where the street ran, a few pedestrians had stopped, intrigued by these men having a discussion on the deck of a barge. It seemed to Maigret that the tramps had moved forwards a few metres. As for the crane, it was still drawing sand from the hold of the Poitou and emptying it into the lorries waiting their turn.

‘Did he shout loudly?’

‘Yes, monsieur.’

‘What kind of shout? Was he calling for help?’

‘He was yelling. Then there was silence. Then . . .’

‘What did you do?’

‘I jumped in the lifeboat and untied it.’

‘Could you see the drowning man?’

‘No, monsieur, not right away. The skipper of the Poitou must have heard him, too, because he was running along the deck of his barge trying to grab hold of something with his hook.’

‘Carry on.’

Van Houtte was clearly doing the best he could, but it was hard for him, and you could see the sweat form on his forehead.

‘ “There! There!” he was saying.’

‘Who?’

‘The skipper of the Poitou.’

‘And you saw him?’

‘At times I could see him, at other times not.’