A CITY ON MARS

CAN WE SETTLE SPACE, SHOULD WE SETTLE SPACE, AND HAVE WE REALLY THOUGHT THIS THROUGH?

‘Wildly informative, insightful and frequently funny’ sunday times

A CITY ON MARS

‘Rich food for rocketheads and critics alike . . . sharp, well-informed and very funny’ Simon Ings, New Scientist, Books of the Year

‘A refreshing, clear-headed breath of life-support oxygen amidst all the tech-bro naivety and hype on space colonisation. Impeccably researched and argued, yet witty and very easy to read. Superb!’

Lewis Dartnell, author of Being Human

‘Listen up, humans. How to poop in space will be the least of our concerns. Herein are challenges most space-heads, including me, never even considered: not just technological, but legal, ethical, geopolitical. Despite the breadth and depth of research, this is a clear, lively, and hilarious read. Slam dunk, Weinersmiths!’

Mary Roach, author of Fuzz and Packing for Mars

‘A fresh, original take on the “should we or shouldn’t we?” debate . . . a delightfully readable book, full of cartoon illustrations, amusing commentary and real-world case studies’ Erika Nesvold, TLS

‘A romp through the many rooms of space folly . . . amusingly literal and impeccably scientific’ Stuart Jeffries, Guardian

‘Fascinating, hilarious and immaculately researched, A City on Mars is a book that sees beyond the techno-utopia to ask if we should really settle in space. The answer? A resounding “Not yet” . . . Anyone interested in space exploration will love this, and there simply isn’t another popular science book quite like it. If you need a reminder of quite how far the human race has to go, read this’

Katie Sawers, BBC Sky at Night

‘This might be the best book ever written about humans in space, or at least the funniest. I don’t know of anything else quite like it: an extended, comical confrontation between the dreams of space colonies and the gross, dangerous, tedious realities. Read it before you go’ Scott Aaronson, University of Texas at Austin

‘Informative and entertaining’ Andrew Crumey, Literary Review

‘If humanity’s future looks to be in doubt, is living off-world not the ultimate insurance policy for our species? A City on Mars . . . answers this question very bluntly: don’t pin your hopes on it . . . It is peppered with cartoons and jokey-back references, and between each section are interludes tackling some enjoyable anecdotes from space’ James Ball, Spectator

‘Could have been the research notes for an Ursula K. Le Guin, or a James S. A. Corey story, except that it’s filled with jokes, palettecleansing anecdotes and charming cartoon illustrations . . . a popular science book that reads like a conversation with a friend . you can’t get away from this book without thinking about how precious life on Earth is’ Mark Popinchalk, Astrobites

‘Laugh-out-loud-funny’ Scientific American

‘Science writing is rarely as readable (or deflating) as A City on Mars, an informed, irreverent study of how little we actually know of the practical considerations of space colonization, from sex and legal cannibalism to issues of settlement’ Chicago Tribune

‘An excellent book, A City on Mars, sets out persuasively and amusingly why you would have to be wildly optimistic or crushingly stupid to want to set up a space settlement any time soon’ Stephen Bush, Financial Times

‘This playful “homesteader’s guide” to space settlement presents a bleak view of the pursuit . . . The authors examine the increasingly popular dream of a multi-planetary human race with a skepticism informed by ethical, logistical, and legal anxieties’ The New Yorker

‘A wonderful example of what it means to really think a difficult project through, a skill that many of us should acquire . . . The Weinersmiths are self-confessed space geeks who tread a fine line between the sort of constructive critique that would still qualify them as bona fide members of the space-settlement movement and a style of gentle ridicule that might get them rejected as traitors to the cause. A City on Mars is, foremost, a case study in the application of common sense’ Shlomo Angel, Wall Street Journal

‘This witty and wildly informative guide to space colonisation boldly goes where no book has gone before’ Rhys Blakely, Sunday Times

‘Expertise and humour . . . In a world hurtling toward human expansion into space, A City on Mars investigates whether the dream of new worlds won’t create nightmares, both for settlers and the people they leave behind’ Daily Kos

‘The Weinersmiths artfully encourage readers to entertain the thought of living on Mars while skillfully highlighting the absurdity of such a prospect through compelling data and delving into serious questions all through a lighthearted lens . . . [this] tongue-in-cheek narrative will captivate even the skeptics, directing their gaze upward at night’

Debbra Palmer, The New York Journal of Books

‘Painstaking research, clear-eyed objectivity, and good-natured humour . . . Any reader enthusiastic about space settlement will find much to appreciate in this book . . . most importantly, they write with a confident belief that humanity will one day travel off-planet’ Gifford J. Wong, Science

‘A sobering book, but also, ultimately, a hopeful one . . . recommended reading for lots of sci-fi fans out there’

Charles Bonkowsky, Tor.com, Best Books of 2023

‘Hilarious, highly informative and cheeky . . . uses humour and science to douse techno dreams with a dose of reality . . . Even as they shoot down a long list of space fantasies, they explore a lot of really interesting research’ Christie Aschwanden, Undark

‘Entertaining and informative romp through what’s stopping us from moving off-planet . . Well researched and argued, it’s also a very fun read’ Jennifer Rothschild, Arlington Magazine

‘Inventive, funny, and informative . . . Filled with fun illustrations that bring the writing to life, this accessible and thought-provoking book explores what it will really take to build a society on another planet’ American Scientist

‘Of the many books and extensive literature on Space mission architectures, technical and otherwise, this is the only one that is a must-read’ Professor Sinead O’S ullivan, member of the Advisory Council of the European Space Policy Institute

‘Engaging . . . breezy . . . honest yet hilarious . . . delightful cartoons sprinkled throughout the book are sure to pull chuckles out of you’ Space.com

‘Laced with humour but with a real gut punch . . . a fascinating book, packed full of racy space stories, that raises serious questions about the future of human space travel and settlement’ The Explorers Journal

‘An investigation of space settlement that manages to be at the same time informative, sceptical and hilarious’ Engineering and Technology Magazine

‘There’s a tendency to have a rather ethereal and even utopian view of space settlement. Kelly and Zach Weinersmith bring us a highly entertaining and down to Earth (or should one say down to Mars?) view of our future in space, filled with humour and cogent insights’ Charles Cockell, Professor of Astrobiology, Edinburgh University

about the authors

The Weinersmiths, a wife-and-husband research team, co-wrote the New York Times bestselling Soonish. Dr. Kelly Weinersmith is adjunct faculty in the BioSciences Department at Rice University. Her research has been featured in The Atlantic, National Geographic, BBC World, Science, Nature and more Zach Weinersmith makes the acclaimed webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal. His work has been featured in The Economist, The Wall Street Journal, Slate, Forbes, Science Friday and elsewhere.

A City on Mars

Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? KELLY AND ZACH WEINERSMITH

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in the United States of America by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC , New York 2023

First published in Great Britain by Particular Books 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith, 2023

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–0–141–99330–0

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

To the space-settlement community. You welcomed us and you shared your wisdom. Also, your data. We worry that many of you will be disappointed by some of our conclusions, but where we have diverged from your views, we haven’t diverged from your vision of a glorious human future.

7. GiantRotatingSpaceWheels:NotLiterallytheWorstOption148 8. WorseOptions158

Nota Bene: SpaceIsthePlaceforProductPlacement, or,SpaceCapitalisminDaysofYore,Part2167

Nota Bene: SpaceIsthePlaceforProductPlacement, or,SpaceCapitalisminDaysofYore,Part2167

OutputsandInputs:Poop,Food,and“ClosingtheLoop”173 10. There’sNoPlaceLikeSpome:HowtoBuildOuter-SpaceHabitats192 Nota Bene: TheMysteryoftheTamponBandolier213

OutputsandInputs:Poop,Food,and“ClosingtheLoop”173 10. There’sNoPlaceLikeSpome:HowtoBuildOuter-SpaceHabitats192 Nota Bene: TheMysteryoftheTamponBandolier213

11. ACynicalHistoryofSpace219

12. TheOuterSpaceTreaty:GreatforRegulating SpaceSixtyYearsAgo234

13. MurderinSpace:WhoKilledtheMoonAgreement?254

TheOuterSpaceTreaty:GreatforRegulating SpaceSixtyYearsAgo234 13. MurderinSpace:WhoKilledtheMoonAgreement?254

Nota Bene: SpaceCannibalismfromaLegal andCulinaryPerspective273

Nota Bene: SpaceCannibalismfromaLegal andCulinaryPerspective273

Introduction

A Homesteader’s Guide to the Red Planet?

It is no longer a question of if we will colonise the Moon and Mars, but when.

Wherever you are on this planet, you’ve recently given some thought to leaving it. Space is looking more promising every day. ere’s no political corruption on Mars, no war on the Moon, no juvenile jokes on Uranus. Surely space settlement presents the best chance since about 50,000 BC to try out something completely new and leave all the bad stuff behind. After five decades of stagnation in human spacefaring, we now have the technology, the capital, and the desire to go beyond the age of quick forays to the Moon and seize our destiny as a multiplanetary species. Well . . . maybe not. If you’re like most of the nonexperts we’ve talked to as we researched this book, you might have some ideas about space settlement that aren’t quite right. We don’t blame you—the public discourse around space settlement is full of myths, fantasies, and outright misunderstanding of basic facts.

In 2020, for example, SpaceX’s internet service provider, Starlink, released a Terms of Service agreement that declared that “no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities.” is clause is like many statements about outer space settlement: it was promoted by a powerful

advocate, widely shared and commented upon, and profoundly misleading. Earth-based governments do have authority over Mars activities—Mars is regulated by long-standing treaties and is an international commons. Admittedly, the treaties are weird and vague, but they do exist and can’t be de-existed via a Terms of Service agreement.

advocate, widely shared and commented upon, and profoundly misleading. Earth-based governments do have authority over Mars activities—Mars is regulated by long-standing treaties and is an international commons. Admittedly, the treaties are weird and vague, but they do exist and can’t be de-existed via a Terms of Service agreement.

Not all the bad space-settlement discourse comes from rocket billionaires. Consider the 2015 Newsweek article “ ‘Star Wars’ Class Wars: Is Mars the Escape Hatch for the 1 Percent?” which claims “the red planet will likely only be for the rich, leaving the poor to suffer as earth’s environment collapses and confl ict breaks out.” e only way you could believe this would be if you had no idea how thoroughly, incredibly, impossibly horrible Mars is. e average surface temperature is about -60°C. ere’s no breathable air, but there are planetwide dust storms and a layer of toxic dust on the ground. Leaving a 2°C warmer Earth for Mars would be like leaving a messy room so you can live in a toxic waste dump. e truth is that settling other worlds, in the sense of creating selfsustaining societies somewhere away from Earth, is not only quite unlikely anytime soon, it won’t deliver on the benefits touted by advocates. No vast riches, no new independent nations, no second home for humanity, not even a safety bunker for ultra elites.

Not all the bad space-settlement discourse comes from rocket billionaires. Consider the 2015 Newsweek article “ ‘Star Wars’ Class Wars: Is Mars the Escape Hatch for the 1 Percent?” which claims “the red planet will likely only be for the rich, leaving the poor to suffer as earth’s environment collapses and confl ict breaks out.” e only way you could believe this would be if you had no idea how thoroughly, incredibly, impossibly horrible Mars is. e average surface temperature is about -60°C. ere’s no breathable air, but there are planetwide dust storms and a layer of toxic dust on the ground. Leaving a 2°C warmer Earth for Mars would be like leaving a messy room so you can live in a toxic waste dump.

e truth is that settling other worlds, in the sense of creating selfsustaining societies somewhere away from Earth, is not only quite unlikely anytime soon, it won’t deliver on the benefits touted by advocates. No vast riches, no new independent nations, no second home for humanity, not even a safety bunker for ultra elites.

Yet we find ourselves in a world where space agencies, huge corporations, and media-savvy billionaires are promising something else. According to them, settlements are coming, perhaps as soon as 2050 or so. When they are built, they will fi x just about everything. ey will save Earth’s biosphere or enable a wildly creative frontier civilization or provide huge economic advantages for the United States or China or India or whoever else makes the fi rst big move.

Yet we find ourselves in a world where space agencies, huge corporations, and media-savvy billionaires are promising something else. According to them, settlements are coming, perhaps as soon as 2050 or so. When they are built, they will fi x just about everything. ey will save Earth’s biosphere or enable a wildly creative frontier civilization or provide huge economic advantages for the United States or China or India or whoever else makes the fi rst big move.

While we believe all these claims are false, they are buoyed by genuinely game-changing technological developments that have made accessing space much cheaper. In the next decade, it will almost certainly be easier to build outposts in space than ever before. e problem for any would-be settler is that most of the problems, especially those pertaining to things like biology and economics, are far more complex than making bigger rockets or cheaper spacecraft. As we’ll see, ignoring these problems

While we believe all these claims are false, they are buoyed by genuinely game-changing technological developments that have made accessing space much cheaper. In the next decade, it will almost certainly be easier to build outposts in space than ever before. e problem for any would-be settler is that most of the problems, especially those pertaining to things like biology and economics, are far more complex than making bigger rockets or cheaper spacecraft. As we’ll see, ignoring these problems

while trying to force a near-term settlement is a recipe for social calamity and potential danger to the home planet.

while trying to force a near-term settlement is a recipe for social calamity and potential danger to the home planet.

Meanwhile, the international legal structures that govern space have barely been updated since the 1970s. Space law is often vague, ambiguous, and if you accept the interpretation favored by the United States, highly permissive. In the modern world of fast-growing space capitalism and an ever-increasing number of countries with launch capability, we have the makings of a new Moon Race. But racing in the 2020s or 2030s will be very different from racing in the 1960s, in that it will likely involve attempts to gain priority access to the highly limited best portions of the Moon. In terms of the risk of confl ict, it’s much less like two kids seeing who can run the fastest and much more like a growing group of kids scrapping over a small pile of candy.

Meanwhile, the international legal structures that govern space have barely been updated since the 1970s. Space law is often vague, ambiguous, and if you accept the interpretation favored by the United States, highly permissive. In the modern world of fast-growing space capitalism and an ever-increasing number of countries with launch capability, we have the makings of a new Moon Race. But racing in the 2020s or 2030s will be very different from racing in the 1960s, in that it will likely involve attempts to gain priority access to the highly limited best portions of the Moon. In terms of the risk of confl ict, it’s much less like two kids seeing who can run the fastest and much more like a growing group of kids scrapping over a small pile of candy.

at’s dangerous. If we convince you that there’s no clear return on investment here, then it’s needlessly dangerous. Oh, and actually let’s ruin the metaphor here a little and make it so the kids also have nuclear weapons.

at’s dangerous. If we convince you that there’s no clear return on investment here, then it’s needlessly dangerous. Oh, and actually let’s ruin the metaphor here a little and make it so the kids also have nuclear weapons.

So. Space settlements. Have we really thought this through?

So. Space settlements. Have we really thought this through?

If humanity survives the next few centuries, it’s probable we’ll expand into space. People, nations, and the international community have options about how to proceed. e choices we make now— about the pace of expansion and the rules underpinning it—will shape that future in ways we can’t yet imagine. e wrong choices wouldn’t merely slow us down, they might create existential risk for humanity.

If humanity survives the next few centuries, it’s probable we’ll expand into space. People, nations, and the international community have options about how to proceed. e choices we make now— about the pace of expansion and the rules underpinning it—will shape that future in ways we can’t yet imagine. e wrong choices wouldn’t merely slow us down, they might create existential risk for humanity.

We can’t make these choices properly unless people actually know what the truth is about space settlement. All of it. Not just the size of the rocket or the power needs of a settlement or the available minerals in asteroids, but the big, open questions about things like medicine, reproduction, law, ecology, economics, sociology, and warfare. Detailed treatments that are honest about the severe difficulty of these things are almost invariably left out of books and documentaries about space settlement.

We can’t make these choices properly unless people actually know what the truth is about space settlement. All of it. Not just the size of the rocket or the power needs of a settlement or the available minerals in asteroids, but the big, open questions about things like medicine, reproduction, law, ecology, economics, sociology, and warfare. Detailed treatments that are honest about the severe difficulty of these things are almost invariably left out of books and documentaries about space settlement.

Why is this discourse so often bad? We believe there are two major reasons. First, the general public knows very little about space. Most people can name exactly one astronaut, and with an appropriate mnemonic can say the planets in order. Outside of a few weirdos, most of us don’t know things like what lunar soil is made of, or what the Outer Space Treaty says, or the history of nuclear weapon detonation in space.

Why is this discourse so often bad? We believe there are two major reasons. First, the general public knows very little about space. Most people can name exactly one astronaut, and with an appropriate mnemonic can say the planets in order. Outside of a few weirdos, most of us don’t know things like what lunar soil is made of, or what the Outer Space Treaty says, or the history of nuclear weapon detonation in space.

Given the limited public knowledge of space science in general, knowledge of its weird little cousin— space-settlement science—is almost nonexistent. And that’s where we arrive at the second problem. If you are ignorant about space settlement and want to become educated, many of the articles you’ll read, many of the documentaries you’ll watch, and pretty much every single book on the topic have been created by an advocate for space settlement.

Given the limited public knowledge of space science in general, knowledge of its weird little cousin— space-settlement science—is almost nonexistent. And that’s where we arrive at the second problem. If you are ignorant about space settlement and want to become educated, many of the articles you’ll read, many of the documentaries you’ll watch, and pretty much every single book on the topic have been created by an advocate for space settlement.

Now look, there’s nothing wrong with advocacy. e space-settlement geeks we’ve met are smart, thoughtful people. Most of them, anyway. But reading about space settlement today is kind of like reading about what quantity of beer is safe to drink in a world where all the relevant books are written by breweries. Even when they’re trying to be evenhanded, they leave things out. One of the most prominent books on space settlement, e Case for Mars, is over 400 pages long, including obscure historical

Now look, there’s nothing wrong with advocacy. e space-settlement geeks we’ve met are smart, thoughtful people. Most of them, anyway. But reading about space settlement today is kind of like reading about what quantity of beer is safe to drink in a world where all the relevant books are written by breweries. Even when they’re trying to be evenhanded, they leave things out. One of the most prominent books on space settlement, e Case for Mars, is over 400 pages long, including obscure historical

information on Mars conferences of the 1980s as well as detailed chemical equations for plastic production at the Martian surface, but never once mentions the existence of international space law. Of the five decades of legal precedent that will dictate the political nature and geopolitical consequences of any Martian future, not a word.

information on Mars conferences of the 1980s as well as detailed chemical equations for plastic production at the Martian surface, but never once mentions the existence of international space law. Of the five decades of legal precedent that will dictate the political nature and geopolitical consequences of any Martian future, not a word.

e little book you’re reading right now, which admittedly begins with a Uranus joke and contains an explainer on space cannibalism (stay tuned), is nevertheless the only popular science book we’re aware of that offers the whole picture without trying to sell you on the idea of near-term space expansion.* Rather, we’ll try to clear up a lot of misconceptions and then replace them with a much more realistic view of how feasible space settlements are and what they might mean for humanity.

e little book you’re reading right now, which admittedly begins with a Uranus joke and contains an explainer on space cannibalism (stay tuned), is nevertheless the only popular science book we’re aware of that offers the whole picture without trying to sell you on the idea of near-term space expansion.* Rather, we’ll try to clear up a lot of misconceptions and then replace them with a much more realistic view of how feasible space settlements are and what they might mean for humanity.

But fi rst, we should introduce ourselves. Hi. We’re Kelly and Zach Weinersmith. Kelly is a biologist and Zach is a cartoonist. We’re also a wife-and-husband research team who’ve spent the last four years trying to understand how humans will become space settlers. We’ve gone to conferences, conducted endless interviews, and collected, at last count, twentyseven shelves of books and papers on space settlement and related subjects. We are space geeks. We love rocket launches and zero gravity antics. We love space history’s strange corners like red cubes and tampon bandoliers. We love visionary plans for a glorious future. We are also very skeptical people. If you want to visualize us, imagine John F. Kennedy giving a beautiful, uplifting speech on sailing “this new ocean,” and then notice in the background two people squinting at the middle distance, thinking “but is it really like an ocean?”

But fi rst, we should introduce ourselves. Hi. We’re Kelly and Zach Weinersmith. Kelly is a biologist and Zach is a cartoonist. We’re also a wife-and-husband research team who’ve spent the last four years trying to understand how humans will become space settlers. We’ve gone to conferences, conducted endless interviews, and collected, at last count, twentyseven shelves of books and papers on space settlement and related subjects. We are space geeks. We love rocket launches and zero gravity antics. We love space history’s strange corners like red cubes and tampon bandoliers. We love visionary plans for a glorious future. We are also very skeptical people. If you want to visualize us, imagine John F. Kennedy giving a beautiful, uplifting speech on sailing “this new ocean,” and then notice in the background two people squinting at the middle distance, thinking “but is it really like an ocean?”

After a few years of researching space settlements, we began in secret to refer to ourselves as the “space bastards” because we found we were more pessimistic than almost everyone in the space-settlement field, and especially skeptical about the most grand plans of space geeks. We weren’t always this way. e data made us do it. Frankly, we are cowards and would very much like to agree with the consensus. We didn’t like being this

After a few years of researching space settlements, we began in secret to refer to ourselves as the “space bastards” because we found we were more pessimistic than almost everyone in the space-settlement field, and especially skeptical about the most grand plans of space geeks. We weren’t always this way. e data made us do it. Frankly, we are cowards and would very much like to agree with the consensus. We didn’t like being this

* at said, there is a longstanding critical literature with a growing number of recent entries, such as Space Forces by Fred Scharmen and Off -Earth by Erika Nesvold.

* at said, there is a longstanding critical literature with a growing number of recent entries, such as Space Forces by Fred Scharmen and Off -Earth by Erika Nesvold.

pessimistic, especially about an endeavor that so many people think embodies the best of human nature. It makes one feel like, well, a bastard. We think space settlement is possible, but the discourse needs more realism—not in order to ruin everyone’s fun, but to provide guardrails against genuinely dangerous directions for planet Earth.

pessimistic, especially about an endeavor that so many people think embodies the best of human nature. It makes one feel like, well, a bastard.

We think space settlement is possible, but the discourse needs more realism—not in order to ruin everyone’s fun, but to provide guardrails against genuinely dangerous directions for planet Earth.

How We Became Space Bastards . . . and You Can Too!

How We Became Space Bastards . . .

and You Can Too!

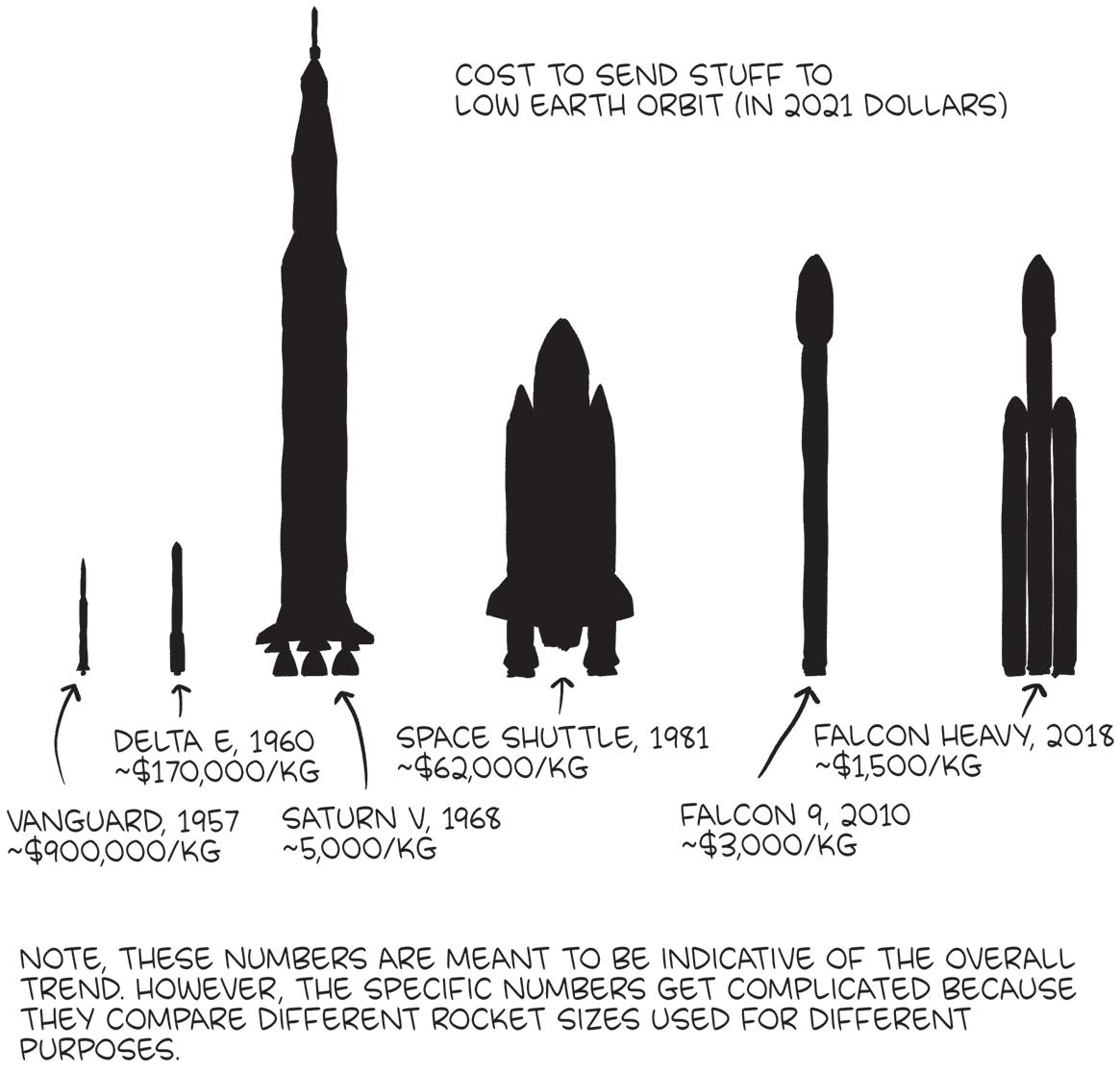

If you’re new to the study of space, you may not be aware of the scale of the revolution in the cost of access, and in the space business generally, that has been ongoing since the mid 2010s.

If you’re new to the study of space, you may not be aware of the scale of the revolution in the cost of access, and in the space business generally, that has been ongoing since the mid 2010s.

Most of us have some sense that the 1950s and 1960s were awash in glorious space promises: Moon bases, orbital vacations, Martian pioneers, and especially if we’re talking late-’60s space books, weird low-gravity erotic possibilities. All this gave way to the shag-carpeted misery of the ’70s and forty years of moderate and decidedly chaste human presence in space. is failure is sometimes blamed on a loss of imagination or ambition, but a pretty simple explanation is cost. Changes in the price of launch explain both the wild dreams of the early post–Moon landing era and the forty years of disappointment. If you look at just the period from the fi rst orbit in 1957 to the end of the 1960s, the price of putting something in orbit fell by around 90–99 percent. If each subsequent decade did likewise, sending a package to space would now be cheaper than sending international mail. is is why if you want to find truly extravagant space-settlement proposals, the groovy years are when all the best books got published.

Most of us have some sense that the 1950s and 1960s were awash in glorious space promises: Moon bases, orbital vacations, Martian pioneers, and especially if we’re talking late-’60s space books, weird low-gravity erotic possibilities. All this gave way to the shag-carpeted misery of the ’70s and forty years of moderate and decidedly chaste human presence in space. is failure is sometimes blamed on a loss of imagination or ambition, but a pretty simple explanation is cost. Changes in the price of launch explain both the wild dreams of the early post–Moon landing era and the forty years of disappointment. If you look at just the period from the fi rst orbit in 1957 to the end of the 1960s, the price of putting something in orbit fell by around 90–99 percent. If each subsequent decade did likewise, sending a package to space would now be cheaper than sending international mail. is is why if you want to find truly extravagant space-settlement proposals, the groovy years are when all the best books got published.

Sadly for many a geeky heart, the prices stopped falling around the early 1970s, and the Space Shuttle, which was supposed to make travel routine, cheap, and safe, failed on all three fronts, remaining, by one estimate, the costliest way to put mass in orbit for decades. at was the state of play until the 2010s when, largely as a result of a US policy shift and SpaceX in particular, the cost of putting stuff in space began to fall dramatically again.

Sadly for many a geeky heart, the prices stopped falling around the early 1970s, and the Space Shuttle, which was supposed to make travel routine, cheap, and safe, failed on all three fronts, remaining, by one estimate, the costliest way to put mass in orbit for decades. at was the state of play until the 2010s when, largely as a result of a US policy shift and SpaceX in particular, the cost of putting stuff in space began to fall dramatically again.

is doesn’t just mean more rocket launches, it means more spacecraft. In 2015, there were about fourteen hundred active satellites. As of 2021, there were about five thousand; and as of October 2022, around three thousand working satellites are controlled by SpaceX’s satellite internet service, Starlink.

is doesn’t just mean more rocket launches, it means more spacecraft. In 2015, there were about fourteen hundred active satellites. As of 2021, there were about five thousand; and as of October 2022, around three thousand working satellites are controlled by SpaceX’s satellite internet service, Starlink.

Space tourism, long promised but rarely delivered on, appears to actually be happening. Jeff Bezos’s rocket company Blue Origin regularly sends people on 100-kilometer-high hops, and SpaceX has contracted to send tourists around the Moon. Where once there were only a few government agencies doing space launch, there is now a growing number of private entities competing on cost. Meanwhile, humanity’s appetite for highspeed data everywhere all the time continues to boom, with one paper finding people in the United States interact with satellites an average of

Space tourism, long promised but rarely delivered on, appears to actually be happening. Jeff Bezos’s rocket company Blue Origin regularly sends people on 100-kilometer-high hops, and SpaceX has contracted to send tourists around the Moon. Where once there were only a few government agencies doing space launch, there is now a growing number of private entities competing on cost. Meanwhile, humanity’s appetite for highspeed data everywhere all the time continues to boom, with one paper finding people in the United States interact with satellites an average of

thirty-six times a day. Estimates vary, but investor prospectuses put out by financial organizations tend to agree that the overall space business will be worth at least a trillion dollars by 2040 or so, assuming no huge uptick in the pace of growth.

thirty-six times a day. Estimates vary, but investor prospectuses put out by financial organizations tend to agree that the overall space business will be worth at least a trillion dollars by 2040 or so, assuming no huge uptick in the pace of growth.

In short: the hype is real. Being concerned about the laws pertaining to space expansion in 2005 would’ve been very premature. But 2025 is apt to be a different story.

In short: the hype is real. Being concerned about the laws pertaining to space expansion in 2005 would’ve been very premature. But 2025 is apt to be a different story.

Watching this trend was a weird experience for us. As it began to ramp up, we were writing a book called Soonish about futuristic technology, which included sections on the effects of cheaper access to outer space. In late 2015, reusable rockets, one of the keys to cheap space launch, had become real. By the time the book landed in stores, they were routine. What would humanity do with these new powers?

Watching this trend was a weird experience for us. As it began to ramp up, we were writing a book called Soonish about futuristic technology, which included sections on the effects of cheaper access to outer space. In late 2015, reusable rockets, one of the keys to cheap space launch, had become real. By the time the book landed in stores, they were routine. What would humanity do with these new powers?

One clue came from research we’d done on asteroid mining, the attempt to harvest valuable matter from the asteroid belt or near-Earth objects. Our analysis was that harvesting asteroids for commodities to be used on Earth was economically unlikely and, well, try to imagine explaining to a hadrosaur about your plan to hurl heavy space objects toward Earth for processing.

One clue came from research we’d done on asteroid mining, the attempt to harvest valuable matter from the asteroid belt or near-Earth objects. Our analysis was that harvesting asteroids for commodities to be used on Earth was economically unlikely and, well, try to imagine explaining to a hadrosaur about your plan to hurl heavy space objects toward Earth for processing.

But if you are starting a settlement in space, asteroids are quite interesting indeed. e asteroid belt contains over 2 sextillion kilograms worth of

But if you are starting a settlement in space, asteroids are quite interesting indeed. e asteroid belt contains over 2 sextillion kilograms worth of

stuff: metals, carbon, oxygen, water, all of it already boosted away from Earth and ready for use. With the new rocket technology and huge sums of money pouring into the business, effectively you had a way to get to the space frontier plus homebuilding materials waiting on-site.

stuff: metals, carbon, oxygen, water, all of it already boosted away from Earth and ready for use. With the new rocket technology and huge sums of money pouring into the business, effectively you had a way to get to the space frontier plus homebuilding materials waiting on-site.

Even the legal picture for space settlement appeared to be improving. While there was debate about whether or not the existing international space treaties allowed resource extraction for profit, in 2015, the United States passed a law specifically codifying the idea that Americans can exploit space resources without limit. And at least Luxembourg seemed to agree, passing a similar law and dumping a ton of money into two USbased asteroid mining companies. Space access was getting easier, resources in space were plentiful, countries were starting to give the green light for developers to go nuts, and the guy in charge of the biggest rocket company was Elon Musk— a dynamic tech geek whose stated goal was Mars settlement in his lifetime.

Even the legal picture for space settlement appeared to be improving. While there was debate about whether or not the existing international space treaties allowed resource extraction for profit, in 2015, the United States passed a law specifically codifying the idea that Americans can exploit space resources without limit. And at least Luxembourg seemed to agree, passing a similar law and dumping a ton of money into two USbased asteroid mining companies. Space access was getting easier, resources in space were plentiful, countries were starting to give the green light for developers to go nuts, and the guy in charge of the biggest rocket company was Elon Musk— a dynamic tech geek whose stated goal was Mars settlement in his lifetime.

Okay, sure the path to space settlements, as opposed to space hotels or research bases, was a little hazier, but then again there was so much money going into the design of rockets, spacecraft, and even some life-support technology. At the very least, space settlement was coming closer. e dreams of the 1950s seemed like they might finally manifest by the 2050s.

Okay, sure the path to space settlements, as opposed to space hotels or research bases, was a little hazier, but then again there was so much money going into the design of rockets, spacecraft, and even some life-support technology. At the very least, space settlement was coming closer. e dreams of the 1950s seemed like they might finally manifest by the 2050s.

We wanted to contribute. We saw space settlement as a near-term possibility and intended to write a sort of sociological road map—how to scale to one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand people, and beyond. A little guide to explain to the public what comes next. But we also had a few nagging concerns. ings we didn’t understand, like how to design the legal regime to make it safe to live in a solar system where dozens of nations, corporations, and possibly single individuals can sling dinosaur-annihilationsize objects at the homeworld. A clear protocol would be nice. What we found was that, with just a few exceptions, concerns of this sort were ignored, sometimes even treated with hostility by space-settlement advocates.

We wanted to contribute. We saw space settlement as a near-term possibility and intended to write a sort of sociological road map—how to scale to one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand people, and beyond. A little guide to explain to the public what comes next. But we also had a few nagging concerns. ings we didn’t understand, like how to design the legal regime to make it safe to live in a solar system where dozens of nations, corporations, and possibly single individuals can sling dinosaur-annihilationsize objects at the homeworld. A clear protocol would be nice. What we found was that, with just a few exceptions, concerns of this sort were ignored, sometimes even treated with hostility by space-settlement advocates.

As we dug in, our stack of concerns got bigger and bigger. How does democracy function in a society where air is rationed— and possibly under corporate control? How does sociology change if humans can’t reproduce unless they’re in Earth-normal gravity? How do we avoid a scramble for

As we dug in, our stack of concerns got bigger and bigger. How does democracy function in a society where air is rationed— and possibly under corporate control? How does sociology change if humans can’t reproduce unless they’re in Earth-normal gravity? How do we avoid a scramble for

territory if some regions of space are better than others? Incidentally, what is the actual space law today, how did it get that way, and is it likely to change? ese questions seemed very basic to space settlement, and frankly really interesting, but were typically skipped over as things that would just get worked out as the rockets got bigger. So the book became less about explaining the deal on future settlements and more about getting to the bottom of unexplored questions, the pursuit of which led us to some weird places.

territory if some regions of space are better than others? Incidentally, what is the actual space law today, how did it get that way, and is it likely to change? ese questions seemed very basic to space settlement, and frankly really interesting, but were typically skipped over as things that would just get worked out as the rockets got bigger. So the book became less about explaining the deal on future settlements and more about getting to the bottom of unexplored questions, the pursuit of which led us to some weird places.

We read about caves on the Moon, uncomfortably detailed orbital mating concepts, space madness, Moon law, plans for Martian company towns, hopes for new ways of life in distant worlds. We read dozens of old space books going back to the 1920s, many of them predicting imminent space settlements. We talked to experts in the economic and political fields who had little interest in space, but also to space advocates and space entrepreneurs. Friends, we are practically bursting with weird space knowledge. Did you know the Colombian constitution asserts a claim to a specific region of space? Did you know the fi rst woman to step foot in a space station was “gifted” an apron and asked if she’d handle cooking and cleaning for the rest of her mission? Did you know an early space lifesupport concept involved a substance that could double as shelving and as breakfast? Did you know former US Republican Party presidential nominee Barry Goldwater once advocated sending bull semen to orbit to separate sperm for sex-selection purposes?

We read about caves on the Moon, uncomfortably detailed orbital mating concepts, space madness, Moon law, plans for Martian company towns, hopes for new ways of life in distant worlds. We read dozens of old space books going back to the 1920s, many of them predicting imminent space settlements. We talked to experts in the economic and political fields who had little interest in space, but also to space advocates and space entrepreneurs. Friends, we are practically bursting with weird space knowledge. Did you know the Colombian constitution asserts a claim to a specific region of space? Did you know the fi rst woman to step foot in a space station was “gifted” an apron and asked if she’d handle cooking and cleaning for the rest of her mission? Did you know an early space lifesupport concept involved a substance that could double as shelving and as breakfast? Did you know former US Republican Party presidential nominee Barry Goldwater once advocated sending bull semen to orbit to separate sperm for sex-selection purposes?

While we fell in love with space settlement as a field of study, we became more concerned about all the proposals for doing it in the coming decades. It turns out when you talk about technical things like the size of rockets, or whether Mars has water and carbon, the picture can look pretty solid. When you get into the more squishy details of human existence, things start to look, well, squishy.

While we fell in love with space settlement as a field of study, we became more concerned about all the proposals for doing it in the coming decades. It turns out when you just talk about technical things like the size of rockets, or whether Mars has water and carbon, the picture can look pretty solid. When you get into the more squishy details of human existence, things start to look, well, squishy.

Especially squishy, for example, are space babies. Can we make them? Proposals for settlements often just assume you can safely have natural population growth. We don’t know if this is true, and there are good reasons to suppose it isn’t. A start-up called SpaceLife Origin announced in 2018 their goal of the fi rst human birth in space by 2024. In 2019, their

Especially squishy, for example, are space babies. Can we make them? Proposals for settlements often just assume you can safely have natural population growth. We don’t know if this is true, and there are good reasons to suppose it isn’t. A start-up called SpaceLife Origin announced in 2018 their goal of the fi rst human birth in space by 2024. In 2019, their

CEO left, citing “serious ethical, safety, and medical concerns.” at’s exactly right. Out of all the NASA astronauts, only five have spent nine consecutive months in space, only two of those five have been women, and none of them had to do it while being a fetus. As for the person around the fetus, they might have concerns too. Moms on Earth worry about things like eating sushi or having a beer. Try 1 percent bone loss per month while doing several hours of resistance training every day in a high-radiation, high-carbon-dioxide atmosphere without Earth-normal gravity. It’s certainly possible everything will be fine, but we wouldn’t want to bet on it. Given that population growth requires babies not just to be born, but to grow up to have their own babies, getting appropriate safety protocols would take decades, even if we unethically began doing experiments on humans starting tomorrow. But we aren’t. e current state of the art is short, unsystematic experiments in orbit, like the one where geckos were sent up for some highly documented together time, before the experiment failed and everyone froze to death. C’est la vie dans l’espace.

CEO left, citing “serious ethical, safety, and medical concerns.” at’s exactly right. Out of all the NASA astronauts, only five have spent nine consecutive months in space, only two of those five have been women, and none of them had to do it while being a fetus. As for the person around the fetus, they might have concerns too. Moms on Earth worry about things like eating sushi or having a beer. Try 1 percent bone loss per month while doing several hours of resistance training every day in a high-radiation, high-carbon-dioxide atmosphere without Earth-normal gravity. It’s certainly possible everything will be fine, but we wouldn’t want to bet on it. Given that population growth requires babies not just to be born, but to grow up to have their own babies, getting appropriate safety protocols would take decades, even if we unethically began doing experiments on humans starting tomorrow. But we aren’t. e current state of the art is short, unsystematic experiments in orbit, like the one where geckos were sent up for some highly documented together time, before the experiment failed and everyone froze to death. C’est la vie dans l’espace.

Elon Musk says we’ll have boots on Mars in 2029 and a million-person city is possible by twenty or thirty years later. We’ll assume he’s got space babies worked out for now so we can deal with a bigger problem: space sucks. Our impression talking to nongeeks is that while they realize space sucks, they have underestimated the scale of suckitude. We said above that you’d be crazy to leave Earth for Mars. is is true, but we should add that Mars is easily the most inviting place for space settlement. e runner-up is the Moon, which among its many shortcomings is very poor in carbon, the basic building block of life.

Elon Musk says we’ll have boots on Mars in 2029 and a million-person city is possible by twenty or thirty years later. We’ll assume he’s got space babies worked out for now so we can deal with a bigger problem: space sucks. Our impression talking to nongeeks is that while they realize space sucks, they have underestimated the scale of suckitude. We said above that you’d be crazy to leave Earth for Mars. is is true, but we should add that Mars is easily the most inviting place for space settlement. e runner-up is the Moon, which among its many shortcomings is very poor in carbon, the basic building block of life.

e result of the general awfulness of space is that you’re likely living underground to keep the environment from touching you. Survival for a million people will require a very good seal-in, enormous amounts of electricity, an insanely large structure, and hardest of all, an artificial ecosystem to sustain everyone inside. Can we do this? e biggest such system ever built was Biosphere 2, created in the 1990s, which sustained a total of eight people for two hungry years. Can we realistically scale from eight people to one million in the next thirty years? Like with space babies, the problem here isn’t just that the technology is challenging. Computers were challenging and so were airplanes, but we still built them. e problem is that getting from here to there is going to require understanding an extremely complex biological system that settlers will be reliant on for food, clean water, air, and not-dying in general. We do it, but at the pace of ecology, not venture capital. Speaking of which, as with space babies, nobody is spending the kind of money necessary to get answers in a hurry, perhaps because there’s no obvious profit in things like orbital obstetrics or airtight greenhouses the size of two Singapores.*

e result of the general awfulness of space is that you’re likely living underground to keep the environment from touching you. Survival for a million people will require a very good seal-in, enormous amounts of electricity, an insanely large structure, and hardest of all, an artificial ecosystem to sustain everyone inside. Can we do this? e biggest such system ever built was Biosphere 2, created in the 1990s, which sustained a total of eight people for two hungry years. Can we realistically scale from eight people to one million in the next thirty years? Like with space babies, the problem here isn’t just that the technology is challenging. Computers were challenging and so were airplanes, but we still built them. e problem is that getting from here to there is going to require understanding an extremely complex biological system that settlers will be reliant on for food, clean water, air, and not-dying in general. We can do it, but at the pace of ecology, not venture capital. Speaking of which, as with space babies, nobody is spending the kind of money necessary to get answers in a hurry, perhaps because there’s no obvious profit in things like orbital obstetrics or airtight greenhouses the size of two Singapores.*

We still don’t know a lot of fi rst-order stuff, and getting that knowledge is going to be expensive, time-consuming, and without an obvious return on investment. If you’re like us, at this point your thought is— okay, the science and tech are hard, but we can still do it, and we should do it because it’s awesome. is unfortunately leads to a problem bigger than science or technology: law.

We still don’t know a lot of fi rst-order stuff, and getting that knowledge is going to be expensive, time-consuming, and without an obvious return on investment. If you’re like us, at this point your thought is— okay, the science and tech are hard, but we can still do it, and we should do it because it’s awesome. is unfortunately leads to a problem bigger than science or technology: law.

Believe it or not, there is space law and there are space lawyers. ey are not briefcase-toting people in space suits, but scholars of international law. ey have conferences, institutes, moot courts, and as far as we can tell are very annoyed that space-settlement fans often pretend they don’t exist. We’ll get into the details later, but the overarching problem is that the way space law interacts with modern technology and geopolitics is practically designed to produce crisis if humanity moves toward space settlements. Here’s why: space is a commons. It is shared. Nobody is allowed

Believe it or not, there is space law and there are space lawyers. ey are not briefcase-toting people in space suits, but scholars of international law. ey have conferences, institutes, moot courts, and as far as we can tell are very annoyed that space-settlement fans often pretend they don’t exist. We’ll get into the details later, but the overarching problem is that the way space law interacts with modern technology and geopolitics is practically designed to produce crisis if humanity moves toward space settlements. Here’s why: space is a commons. It is shared. Nobody is allowed

*Biosphere 2 was about 3.14 acres for eight people. If we scale that to a million people, you’re around 1,600 square kilometers of greenhouse.

*Biosphere 2 was about 3.14 acres for eight people. If we scale that to a million people, you’re around 1,600 square kilometers of greenhouse.

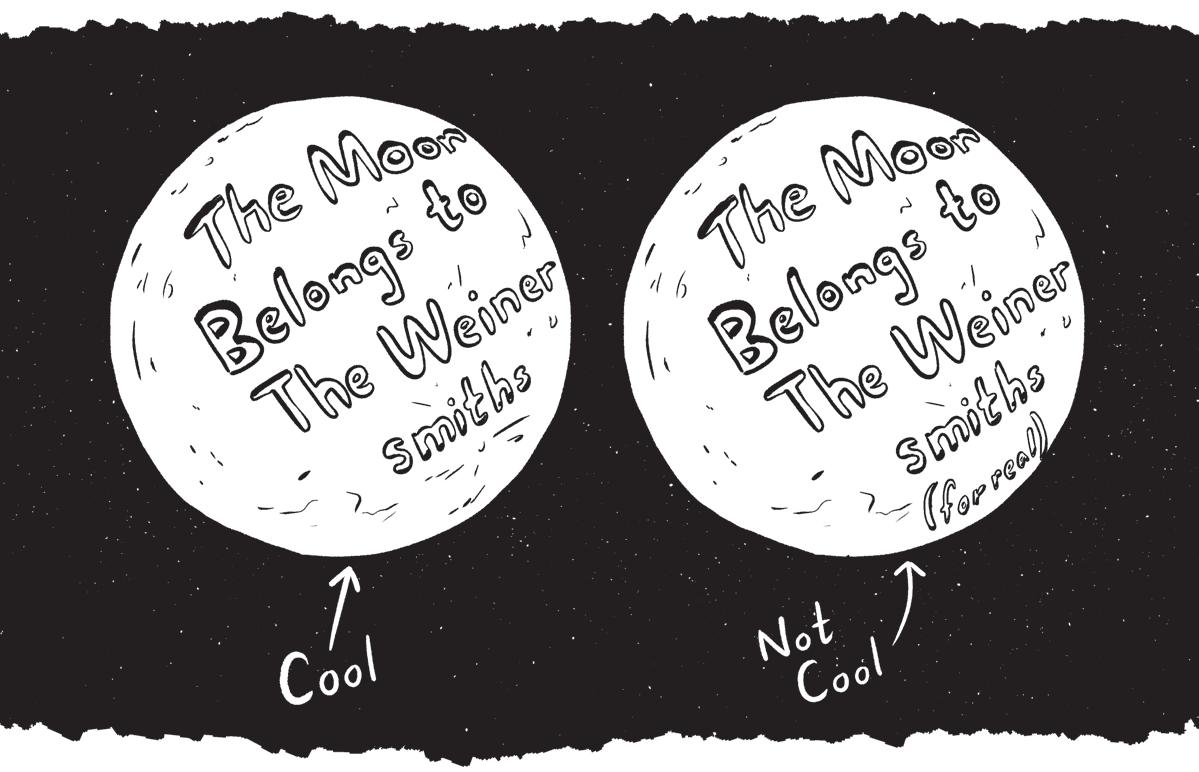

to appropriate any territory. However, under many modern interpretations, and absolutely under the American interpretation, everybody can use as much of the surface as they like. Let’s sit on that a second: you can use the entire lunar surface any way you please, ad libitum, as long as you never say “ is is mine in the sense of being my territory.” Legally, we could probably write “ e Moon Belongs to the Weinersmiths, You Filthy Earth Scum” in giant letters visible from Earth, as long as we didn’t claim to actually believe it.

to appropriate any territory. However, under many modern interpretations, and absolutely under the American interpretation, everybody can use as much of the surface as they like. Let’s sit on that a second: you can use the entire lunar surface any way you please, ad libitum, as long as you never say “ is is mine in the sense of being my territory.” Legally, we could probably write “ e Moon Belongs to the Weinersmiths, You Filthy Earth Scum” in giant letters visible from Earth, as long as we didn’t claim to actually believe it.

Other players could do likewise: China, India, the European Space Agency, or private launch corporations, for that matter. Add in the fact that only a tiny amount of the lunar surface is especially useful, and that the most likely parties to an argument are nuclear powers, and you have what might be called an interesting situation. Kelly attended the 2019 International Astronautical Congress—think space-nerd prom only with major officials from world government and space agencies—where she sat in on a session on space law. e going opinion among US officials? Space law is too slow and nobody agrees on the path forward, so we should just pass national rules, try to get friendly nations to agree to go along with

Other players could do likewise: China, India, the European Space Agency, or private launch corporations, for that matter. Add in the fact that only a tiny amount of the lunar surface is especially useful, and that the most likely parties to an argument are nuclear powers, and you have what might be called an interesting situation. Kelly attended the 2019 International Astronautical Congress—think space-nerd prom only with major officials from world government and space agencies—where she sat in on a session on space law. e going opinion among US officials? Space law is too slow and nobody agrees on the path forward, so we should just pass national rules, try to get friendly nations to agree to go along with

them, and do our thing. e problem as we see it is that doing our thing may involve quasi-territorial claims that push the interpretation of international law to its limits.

them, and do our thing. e problem as we see it is that doing our thing may involve quasi-territorial claims that push the interpretation of international law to its limits.

Most worrisome, this decision to rush headlong into crisis might be taken even if there’s no good economic or military reason to do it. Zach once talked to some international security scholars about why nations do things that make no sense. His specific question was about something called helium-3, which is a substance several governments, companies, and space agencies say they will mine from the Moon for its economic value. For reasons we’ll discuss later, we believe this is a plainly silly idea, and we wondered why all these different players were claiming to be interested. e response was along the lines of “Well, the attitude is . . . if China does it . . . we have to do it too.” Space officials aren’t coy about this either. In a 2022 interview with e New York Times, NASA administrator Bill Nelson said regarding the Chinese presence on the lunar surface: “We have to be concerned that they would say: ‘ is is our exclusive zone. You stay out.’ ”

Most worrisome, this decision to rush headlong into crisis might be taken even if there’s no good economic or military reason to do it. Zach once talked to some international security scholars about why nations do things that make no sense. His specific question was about something called helium-3, which is a substance several governments, companies, and space agencies say they will mine from the Moon for its economic value. For reasons we’ll discuss later, we believe this is a plainly silly idea, and we wondered why all these different players were claiming to be interested. e response was along the lines of “Well, the attitude is . . . if China does it . . . we have to do it too.” Space officials aren’t coy about this either. In a 2022 interview with e New York Times, NASA administrator Bill Nelson said regarding the Chinese presence on the lunar surface: “We have to be concerned that they would say: ‘ is is our exclusive zone. You stay out.’ ”

If you want to safely settle space, technology is hard, but it isn’t enough; we also need at least somewhat harmonious international relations. at’s not looking great on Earth right this second, and space may not be all that much different. In a 2022 report put out by the Defense Innovation Unit, written by workshop attendees hailing from organizations like the US Space Force and Air Force, the authors say a new “Space Race” with China has already started. As they write: “ e competition represents a major inflection point not just for the 21st Century but for all of human history. e New Space Race seeks to achieve nothing less than the permanent establishment of the fi rst off-planet, human settlement propelled and sustained by a thriving to-, and from-space economy.”

If you want to safely settle space, technology is hard, but it isn’t enough; we also need at least somewhat harmonious international relations. at’s not looking great on Earth right this second, and space may not be all that much different. In a 2022 report put out by the Defense Innovation Unit, written by workshop attendees hailing from organizations like the US Space Force and Air Force, the authors say a new “Space Race” with China has already started. As they write: “ e competition represents a major inflection point not just for the 21st Century but for all of human history. e New Space Race seeks to achieve nothing less than the permanent establishment of the fi rst off-planet, human settlement propelled and sustained by a thriving to-, in-, and from-space economy.”

But there’s some room for optimism. Humanity has peacefully regulated Antarctica and the bottom of the sea— areas that are similar to outer space, in terms of being basically terrible and largely inaccessible until the mid-twentieth century. Whether we can continue to do that in outer space, which since the 1950s has been deeply tied to national prestige, is trickier.

But there’s some room for optimism. Humanity has peacefully regulated Antarctica and the bottom of the sea— areas that are similar to outer space, in terms of being basically terrible and largely inaccessible until the mid-twentieth century. Whether we can continue to do that in outer space, which since the 1950s has been deeply tied to national prestige, is trickier.

But now suppose we pull all this off. We’ve got bubble ecologies, China and the United States are getting along great thanks to a brilliant new

But now suppose we pull all this off. We’ve got bubble ecologies, China and the United States are getting along great thanks to a brilliant new

legal framework, and we’re all making top-notch space babies. We still face one last problem: us.

legal framework, and we’re all making top-notch space babies. We still face one last problem: us.

Given the difficulty of settling space, those who favor it generally come to the table with aspirational goals for humanity. One of the most plausible is that a second human civilization is essentially a backup copy in case we accidentally nuke this one. Or cook it. Or it gets hit by an asteroid. In this vision, space settlement is a Plan B for our species, which makes space settlement a worthy goal regardless of risk or short-term return on investment.

Given the difficulty of settling space, those who favor it generally come to the table with aspirational goals for humanity. One of the most plausible is that a second human civilization is essentially a backup copy in case we accidentally nuke this one. Or cook it. Or it gets hit by an asteroid. In this vision, space settlement is a Plan B for our species, which makes space settlement a worthy goal regardless of risk or short-term return on investment.

But are we certain a Plan B strategy actually delivers increased likelihood of species survival? It may not.

But are we certain a Plan B strategy actually delivers increased likelihood of species survival? It may not.

Space Bastardry: The Long View

Space Bastardry: The Long View

e most detailed treatment of the issue comes from international relations scholar Dr. Daniel Deudney and his book Dark Skies: Space Expansionism, Planetary Geopolitics, and the Ends of Humanity. It’s an involved argument, but the basic idea is this: humans being what we are, the move into space creates at least two forms of existential peril: the risk of nuclear confl ict on Earth due to a scramble for space territory, and the risk of heavy objects being thrown at Earth if humans are allowed to control things like asteroids and massive orbital space stations.

e most detailed treatment of the issue comes from international relations scholar Dr. Daniel Deudney and his book Dark Skies: Space Expansionism, Planetary Geopolitics, and the Ends of Humanity. It’s an involved argument, but the basic idea is this: humans being what we are, the move into space creates at least two forms of existential peril: the risk of nuclear confl ict on Earth due to a scramble for space territory, and the risk of heavy objects being thrown at Earth if humans are allowed to control things like asteroids and massive orbital space stations.

e fi rst point could at least in principle be resolved by a proper legal regime, but the second point is trickier. e more capacity we have to do things in space, the more capacity we have for self-annihilation. at doesn’t require anything like interplanetary war either. Terrorism would be enough, and would probably be harder to eliminate.

e fi rst point could at least in principle be resolved by a proper legal regime, but the second point is trickier. e more capacity we have to do things in space, the more capacity we have for self-annihilation. at doesn’t require anything like interplanetary war either. Terrorism would be enough, and would probably be harder to eliminate.

Deudney is not popular among space-settlement geeks,* but we think he needs to be taken seriously. If he’s right, then even if we can make the needed technology and can work out the law, there still remains a strong argument against a massive human presence in space. Note that there are

Deudney is not popular among space-settlement geeks,* but we think he needs to be taken seriously. If he’s right, then even if we can make the needed technology and can work out the law, there still remains a strong argument against a massive human presence in space. Note that there are

*Well, we, the space bastards, like him. He seems like a genuinely nice guy.

*Well, we, the space bastards, like him. He seems like a genuinely nice guy.

at least two different ways things could go badly: e fi rst is simply more human presence in space increasing the odds of a bad outcome. e second issue is what you might call the tendency to space bastardocracy. is will be detailed further, but there are reasons to suppose space settlement as generally imagined might be especially likely to produce cruel or autocratic governments.

at least two different ways things could go badly: e fi rst is simply more human presence in space increasing the odds of a bad outcome. e second issue is what you might call the tendency to space bastardocracy. is will be detailed further, but there are reasons to suppose space settlement as generally imagined might be especially likely to produce cruel or autocratic governments.

Making Deudney’s arguments especially concerning is the fact that among space-settlement advocates, which let’s remember includes two of the richest men on Earth, both of them rocket company owners, there are all sorts of questionable beliefs about how space will improve humanity. Space settlement is something people have wanted to do since the Victorian era. ere are long-standing societies dedicated to the idea, and over the years they have built up all sorts of arguments for why humans must go to space, must go soon, and how everything will be great when we get there.

Making Deudney’s arguments especially concerning is the fact that among space-settlement advocates, which let’s remember includes two of the richest men on Earth, both of them rocket company owners, there are all sorts of questionable beliefs about how space will improve humanity. Space settlement is something people have wanted to do since the Victorian era. ere are long-standing societies dedicated to the idea, and over the years they have built up all sorts of arguments for why humans must go to space, must go soon, and how everything will be great when we get there.

Depending on which theory you believe, space is supposed to: lessen the chance of war, improve politics, end scarcity, save us from climate change, reinvigorate a homogenized and rapidly wussifying Earth, and in one widely held notion called the “overview effect,” make us all as wise as philosophers. If any of these were true, they might defeat Deudney’s arguments. If we’re all going to be philosophers up there, why worry about war? Or if we have a shot at eliminating scarcity, maybe the existential gamble is worth the danger. e problem is that, for reasons that will be detailed in the rest of the book, these ideas are almost certainly wrong.

Depending on which theory you believe, space is supposed to: lessen the chance of war, improve politics, end scarcity, save us from climate change, reinvigorate a homogenized and rapidly wussifying Earth, and in one widely held notion called the “overview effect,” make us all as wise as philosophers. If any of these were true, they might defeat Deudney’s arguments. If we’re all going to be philosophers up there, why worry about war? Or if we have a shot at eliminating scarcity, maybe the existential gamble is worth the danger. e problem is that, for reasons that will be detailed in the rest of the book, these ideas are almost certainly wrong.

But they remain widespread and influential among powerful technologists in the space-settlement movement and in space agencies. One longstanding thread of space-settlement ideology is broadly libertarian and conservative, seeing the modern Earth as increasingly homogenized and bureaucratized and in need of the influence of a space-frontier civilization to show us a tougher, freer, better way. Elon Musk likely believes some form of this. Consider his recent tweet arguing that “Unless it is stopped, the woke mind virus will destroy civilization and humanity will never reached [sic] Mars.” A related version of this idea is that space will be like the American West, which purportedly made the United States its

But they remain widespread and influential among powerful technologists in the space-settlement movement and in space agencies. One longstanding thread of space-settlement ideology is broadly libertarian and conservative, seeing the modern Earth as increasingly homogenized and bureaucratized and in need of the influence of a space-frontier civilization to show us a tougher, freer, better way. Elon Musk likely believes some form of this. Consider his recent tweet arguing that “Unless it is stopped, the woke mind virus will destroy civilization and humanity will never reached [sic] Mars.” A related version of this idea is that space will be like the old American West, which purportedly made the United States its

modern, dynamic, and ruggedly individualistic self. is idea goes back to the nineteenth century but hasn’t been mainstream among historians since the 1980s. Yet it lives on in government and military documents, political speeches, the National Space Society’s Statement of Philosophy, and is promoted by Dr. Robert Zubrin, president of the Mars Society.

modern, dynamic, and ruggedly individualistic self. is idea goes back to the nineteenth century but hasn’t been mainstream among historians since the 1980s. Yet it lives on in government and military documents, political speeches, the National Space Society’s Statement of Philosophy, and is promoted by Dr. Robert Zubrin, president of the Mars Society.

Jeff Bezos likely got his theory of space settlement from Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill, a professor at Princeton whose lectures Bezos attended as a young student. O’Neill’s philosophy for space oriented around large solarpowered space stations as the way to save Earth’s economy and ecology. is argument may have been plausible circa 1970, when it was widely believed that space would keep getting cheaper and that energy and food crises would result in unprecedented worldwide famines by the 1980s. Today you can do a much better job of saving Earth’s biosphere with Earth-based solar and wind power. Even if we thought space settlements could take pressure off of Earth’s seas and lands, they will absolutely not arrive in time to thwart any environmental calamity.

Jeff Bezos likely got his theory of space settlement from Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill, a professor at Princeton whose lectures Bezos attended as a young student. O’Neill’s philosophy for space oriented around large solarpowered space stations as the way to save Earth’s economy and ecology. is argument may have been plausible circa 1970, when it was widely believed that space would keep getting cheaper and that energy and food crises would result in unprecedented worldwide famines by the 1980s. Today you can do a much better job of saving Earth’s biosphere with Earth-based solar and wind power. Even if we thought space settlements could take pressure off of Earth’s seas and lands, they will absolutely not arrive in time to thwart any environmental calamity.

Whatever else you could say about these ideas, they do appear to be sincerely held. In our experience, people often think that space billionaires are hucksters or liars or even Ponzi schemers. It’s never fun being in the position of saying “Guys, wait! ese billionaires are misunderstood!” But look, setting aside the hype and showmanship, there is every reason to believe rocket billionaires really care about space settlement. Jeff Bezos gave his valedictory speech as a high school student on the topic of space colonies and today is the most important advocate for large, rotating spacestation settlements of the type advocated for by O’Neill. When Elon Musk fi rst got rich off the sale of PayPal, before he created SpaceX, he looked into sending a mouse colony or a small greenhouse to Mars. ere is no money to be made doing this sort of thing; Musk wanted people to see his vision for space during a time when space activity was lackluster.

Whatever else you could say about these ideas, they do appear to be sincerely held. In our experience, people often think that space billionaires are hucksters or liars or even Ponzi schemers. It’s never fun being in the position of saying “Guys, wait! ese billionaires are misunderstood!” But look, setting aside the hype and showmanship, there is every reason to believe rocket billionaires really care about space settlement. Jeff Bezos gave his valedictory speech as a high school student on the topic of space colonies and today is the most important advocate for large, rotating spacestation settlements of the type advocated for by O’Neill. When Elon Musk fi rst got rich off the sale of PayPal, before he created SpaceX, he looked into sending a mouse colony or a small greenhouse to Mars. ere is no money to be made doing this sort of thing; Musk wanted people to see his vision for space during a time when space activity was lackluster.

In our experience, a lot of people think SpaceX in particular is some kind of scam, using old government-created space technology for personal enrichment, or somehow hiding the true costs of space launch to fleece public coffers. We’ve encountered this idea again and again, and all we can say is that it’s so contrary to the plain facts as to verge on a conspiracy

In our experience, a lot of people think SpaceX in particular is some kind of scam, using old government-created space technology for personal enrichment, or somehow hiding the true costs of space launch to fleece public coffers. We’ve encountered this idea again and again, and all we can say is that it’s so contrary to the plain facts as to verge on a conspiracy

theory. However you feel about Musk, SpaceX has genuinely revolutionized space launch, and every space agency on Earth, including NASA, has failed to duplicate their technology. In fairness, Musk’s SpaceX, Bezos’s Blue Origin, and other rocket launch companies have gotten plenty of government contracts, but that’s been the standard way space has been done in the United States since the early days of space fl ight. e revolution in pricing only arrived with SpaceX.

theory. However you feel about Musk, SpaceX has genuinely revolutionized space launch, and every space agency on Earth, including NASA, has failed to duplicate their technology. In fairness, Musk’s SpaceX, Bezos’s Blue Origin, and other rocket launch companies have gotten plenty of government contracts, but that’s been the standard way space has been done in the United States since the early days of space fl ight. e revolution in pricing only arrived with SpaceX.

Both Bezos and Musk overhype things, yes, but the evidence is that they actually believe in a space-settlement future. What concerns us is not that they’re lying, but that they have weird beliefs about human sociology that may shape the future in undesirable ways.

Both Bezos and Musk overhype things, yes, but the evidence is that they actually believe in a space-settlement future. What concerns us is not that they’re lying, but that they have weird beliefs about human sociology that may shape the future in undesirable ways.

The Case for Space at a Moderate Pace

The Case for Space at a Moderate Pace

So here’s the position we’re in: space settlement isn’t going to eliminate scarcity or make us wise or save the environment. Even if it could, the technological and scientific barriers to doing it safely in the near term are enormous and underappreciated. Even if we had the technology, the legal structures right now would likely produce a confl ict as parties scramble for turf. If we’re really unlucky, international competition might force pointless geopolitical escalation among nuclear powers. And even if all that stuff were handled, there would still be good reasons to curtail our ambitions for the long term. And with all that said, very powerful people, aided by recent national laws and multilateral agreements, are pushing to make these things happen as soon as possible.

So here’s the position we’re in: space settlement isn’t going to eliminate scarcity or make us wise or save the environment. Even if it could, the technological and scientific barriers to doing it safely in the near term are enormous and underappreciated. Even if we had the technology, the legal structures right now would likely produce a confl ict as parties scramble for turf. If we’re really unlucky, international competition might force pointless geopolitical escalation among nuclear powers. And even if all that stuff were handled, there would still be good reasons to curtail our ambitions for the long term. And with all that said, very powerful people, aided by recent national laws and multilateral agreements, are pushing to make these things happen as soon as possible.

We don’t think this has to mean that space settlements should never happen. What we do think is that space settlements probably are, and ought to be, a project of centuries, not decades. In particular, we’ll argue that if humanity wants space settlements, we should take a “wait-andgo-big” approach. Wait for big developments in science, technology, and international law, then move many settlers at once.

We don’t think this has to mean that space settlements should never happen. What we do think is that space settlements probably are, and ought to be, a project of centuries, not decades. In particular, we’ll argue that if humanity wants space settlements, we should take a “wait-andgo-big” approach. Wait for big developments in science, technology, and international law, then move many settlers at once.

But the waiting isn’t just sitting around. In the following pages, we learn about spider bots on the Moon, baby making on Martian roller