THEMARRIAGEQUESTION

GEORGE ELIOT’S DOUBLE LIFE

’Triumphantly enlarges our understanding of its subject, and of her time’ financial times

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE MARRIAGE QUESTION

‘As subtle and silent as a Dutch still life . . . Beautifully balancing literary interpretation with biographical and philosophical reflection, Carlisle explores the gamble of yoking your happiness to “the open-endedness of another human being” ’ Frances Wilson, Daily Telegraph, Books of the Year

‘Carves out a space somewhere between biography and literary criticism in a most satisfying way. Carlisle is a philosopher and reads Eliot like an expert witness, recreating her dynamic, ambitious reading and lifelong commitment to intellectual growth and showing its impact in and out of the novels. It finds another layer of Eliot to contemplate and admire, and is thoroughly absorbing’ Claire Harman, TLS, Books of the Year ‘Perceptive and suggestive . . . a richly considered study that brings one close to the heart and mind of a great writer and a wise soul’ Rupert Christiansen, Daily Telegraph

‘Its grander subject isn’t just that suggested by its title – what women, in particular, stand to gain and lose in marriage – but also what it means to lead the moral, rewarding life in general. With this and her previous book on Søren Kierkegaard, Carlisle has confirmed herself as one of the most deep-thinking writers about deep thought’ Prospect, Books of the Year

‘[A] thoughtful book . . . a clear-eyed, if slightly melancholy, portrait of one of our finest novelists’ The Times, Books of the Year

‘Clare Carlisle brings the work of perhaps our finest English novelist into a brilliant new light. This book manages to be both engrossing and rigorous, inhabiting an intimate and expansive vision of creativity and the lived life. Following the pulsing and ever-vital questions of love, desire, compromise and companionship, The Marriage Question is both a thrilling work on Eliot and a probing, illuminating reflection on modern love’ Seán Hewitt

‘Clare Carlisle’s principal achievement in The Marriage Question – a richly textured and absorbing biographical study – is to reveal how, over the course of her novels, essays and poetry, George Eliot systematically built a secular philosophy that concerned itself with morality . . . Carlisle moves from novel to novel, subjecting them to the exacting lens of philosophy. Her chapter on Middlemarch – the masterpiece of Eliot’s middle life – is a dazzler . . . Carlisle’s intense, empathetic study reflects Eliot back to us, echoes her and rises up to meet her in order to give Eliot her philosophical due’ Marina Benjamin, Prospect

‘A new biography by Clare Carlisle, in which, for the first time, Eliot is placed properly in her full intellectual context, elucidating the ideas of her time in beautifully accessible prose . . . Carlisle’s magisterial book has many facets to it: biographical, philosophical, literary. But as its title suggests, it’s also about the theme of marriage, and Carlisle takes the reader into fascinating territory with the doubleness of Eliot’s life . . . The Marriage Question is a splendid addition to the Eliot biographical canon’ Kathy O’S haughnessy, Financial Times

‘Carlisle explores several kinds of “doubleness” that her subject kept in play throughout her life . . . conveys the fruits of her studies and reflection with a light, sometimes even lyrical touch . . . As Clare Carlisle has shown, balancing breadth of knowledge with an emphatic close reading of her subject’s life and work, Eliot’s greatness – her continuing relevance – needs no special pleading’ Jacqueline Banerjee, The Times Literary Supplement

‘Gripping and insightful . . . A brilliant aspect of this book is that Carlisle takes us deep into the world of each of Eliot’s novels, reminding us what masterpieces they are’ Ysenda Maxtone Graham, Daily Mail

‘Eloquent and original . . . combines a biographer’s eye for stories with a philosopher’s nose for questions . . . Masterly and enriching . . . The ideal historian will need great tact and an impious curiosity. Carlisle has both’ James Wood, New Yorker

‘With formidable erudition and insight, this sympathetic author paints her own memorable portrait of the soft-spoken woman who quietly revolutionized the English novel – and who scandalized society by never marrying her husband’ Anna Mundow, Wall Street Journal

‘Careful but impassioned . . . One need not have read all [Eliot’s] works to appreciate The Marriage Question, but, in the most meta sense, it is an ideal companion volume’ Alexandra Jacobs, The New York Times

‘Carlisle is an empathetic and ambitious interpreter. She delves beneath the surface of marriage in Eliot’s novels, finding a world that hums with big questions – about “desire, freedom, selfhood, change, morality, happiness, belief, the mystery of other minds”’ Ann Hulbert, The Atlantic

‘As both Henry James and Clare Carlisle recognize, readers don’t really want to be told. Instead, we want to be invited into the mystery we can sleuth out for ourselves . . a brilliant and important biography’ Beverley Park Rilett, The George Eliot Review

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Clare Carlisle is Professor of Philosophy at King’s College London. She is the author of seven books, including Spinoza’s Religion, Philosopher of the Heart: The Restless Life of Søren Kierkegaard and On Habit. She has also edited George Eliot’s translation of Spinoza’s Ethics. She grew up in Manchester, studied philosophy and theology at Cambridge, and now lives in Hackney.

George Eliot’s Double Life

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Allen Lane 2023

Published in Penguin Books 2024 001

Copyright © Clare Carlisle, 2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–141–99294–5

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business , our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

‘About marriages one can only rejoice with trembling.’

George Eliot to Benjamin Jowett, 14 April 1875

Preface

There is something dazzling about marriage — that leap into the openendedness of another human being. It is difficult to look directly at it, difficult to think that thought. A philosopher usually swoops on such things like a magpie: Look! a shifting, shimmering question, all indeterminacy and iridescence. Don’t you just want to snatch it up, take it home, and sit on it for a long time?

Yet marriage is rarely treated as a philosophical question. Perhaps domestic life, traditionally a feminine domain, has seemed too trivial a subject for deep thinking. When I studied philosophy at university, most of the authors I read were unmarried men: Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, Hume, Kant, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein. Did they regard marriage as a hindrance to the serious work of philosophy, rather than a spur to thought? My friends and I were constantly analysing relationships — our own and other people’s. We sat up late contemplating our parents’ happy and unhappy marriages, and asked ourselves if we would ever get married. I loved the idea of choosing my own family — but how would I know I was making the right choice?

Beneath its conventional surface, marriage simmers with tensions between self and other, body and soul, passion and restraint, the poetry of romantic love and the prose of domestic routine. Each day our partners watch us cross the precarious bridge between our intimate and our social selves. Somehow we are supposed to make a happy home in these fraught, ambiguous double binds. For better or worse, the answers we find to our marriage questions — whether to marry, whom to marry, how to live in a marriage, whether to remain married — are often close to the heart of our life’s meaning. Over centuries these questions have shaped religious, political and social histories. Of course, in such a culture

choosing to be or become single is as significant as choosing to marry — just look at Kierkegaard, whose broken engagement was not just a personal drama but the catalyst for existentialism. As soon as we begin to reflect on marriage we stumble across great philosophical themes: desire, freedom, selfhood, change, morality, happiness, belief, the mystery of other minds.

In the middle years of the nineteenth century Marian Evans found her calling when she transformed herself into George Eliot — an author celebrated for her ‘genius’ as soon as she published her debut novel. During those years she also became a wife. Bruised by a series of messy romantic involvements, she had met the writer George Henry Lewes, whose wife was sleeping with his best friend. After ‘eloping’ to Berlin in 1854 Eliot and Lewes lived together for twenty-four years. They could not be legally married, but she asked people to call her ‘Mrs Lewes’ and dedicated the manuscript of each novel to her ‘Husband’. George Eliot did not appear on my philosophy curriculum, and it was a long time before I discovered that she pursued her marriage question with the tenacity of a great philosopher, as well as the delicacy of a great artist.

Early in her relationship with Lewes she wondered at the ‘great experience’ of marriage — ‘this double life, which helps me to feel and think with double strength’. These words hint at questions that would continue to shape her married life, over the years ahead: ambition, dependence, and the effort to connect thought and feeling which surges through her writing, creating a new philosophical voice. Precisely this combination, and the struggles it entailed, produced the extraordinary works of art — intense, intimate, experimental — that still open our eyes and stretch our souls. George Eliot’s fiction searches the lives of ordinary people to uncover truths we can recognize as our own, truths at once intellectual and emotional. Her literary achievement was so immense that her successors felt bound to break the form of the novel in order to move beyond her.

Eliot’s leap into life with Lewes was a crisis from which she never recovered, though she grew immeasurably within it. Their union was unconsecrated, outside the law: by daring to call it a marriage she was prising the concept from the grip of Church and State. To nearly all her contemporaries the relationship was a scandal, and for years she

was socially ostracized. At the same time, her marriage helped her to become George Eliot. Lewes urged her to begin writing fiction, and gave constant encouragement as she laboured, full of self-doubt, over her work. He acted as her agent, publicist and secretary. For more than two decades ‘Mrs Lewes’ was a role she lived day to day — yet this name was a fiction: the woman she could not be. ‘George Eliot’, too, was an invented self, a male author who was entitled to be a serious thinker as well as a popular novelist.

Eliot belonged to a generation bereft of the old religious certainties. ‘All around us, the intellectual lightships had broken from their moorings,’ wrote J. A. Froude, an historian whose early career coincided with hers. Future generations would ‘never know what it was to find the lights all drifting, the compasses all awry, and nothing left to steer by except the stars.’ In 1851 newly-wed Matthew Arnold wondered if marital fidelity was now the only kind of faith and truth to hope for:

‘Ah love, let us be true / To one another!’ Eliot shared this sense of spiritual search, and likewise turned to long-term love for an anchor in a shifting, spinning modern world. Yet she experienced marriage quite differently from male acquaintances such as Froude, Arnold, and other eminent Victorians. From her youth to her last years she wrestled with what her generation called the Woman Question: how should a woman live in a patriarchal world? In Eliot’s writing as well as in her public and private lives, the Woman Question became inseparable from the marriage question. She lived these questions, often painfully, caught in the tension between her longing for approval and her refusal to compromise.

‘I don’t consider myself as a teacher, but a companion in the struggle of thought,’ Eliot wrote to a friend in 1875, as she worked on her last novel. Writing fiction, she found creative ways to address deep questions: rather than personifying ideas or telling didactic stories, she philosophized through her art. Her willingness to think in the medium of human relations and emotions, and to carry out that thinking in images, symbols and archetypes, expands the canonical view of philosophy that is embedded in universities — institutions that systematically excluded women until the twentieth century. Eliot once reflected that her friend Herbert Spencer, a prominent Victorian philosopher, had an ‘inadequate endowment of emotion’ which made him ‘as good as

dead’ to large swathes of human experience, thereby weakening his arguments and theories. She might as well have been talking about philosophy itself. Her own philosophical style is compassionate, subversive, seasoned with humour, and enriched by an attentiveness in which fleeting moments — a glance, a touch, a flush of feeling — become significant.

Marriage is made of these intimate and ephemeral moments, yet it also has epic proportions. It stretches out through time, into the future, growing and changing: that is why George Eliot had to write grand novels such as Middlemarch to bring it into view. Like a plant, a long-term relationship has its phases of development, its cycles, its seasons, its changing weather. Under adverse conditions, it might wither and die; it might come close to death and then revive. When we imagine a marriage like this, we think about how it is connected with other living things — other people, other relationships — and rooted in an ecosystem. Victorian philosophers learned to call this ecosystem a ‘milieu’ or ‘environment’. We could also call it a world: a mixture of natural, social and cultural conditions.

Getting together with another person means stepping into their world: their family, friendships, culture, career path, ambitions; the places they know and the possibilities they contemplate; their taste and style and habits. Being in a marriage — legal or otherwise — means living in a shared world. We might even say that the marriage is this shared world: again, something that grows and changes.

When Marian Evans met George Lewes in 1853, their worlds already overlapped. They moved in the same circles in London’s literary scene. They had read many of the same books, immersed themselves in intellectual currents that were shaping their century — Spinoza’s philosophy, Carlyle’s histories and satires, Romantic literature. But when their worlds merged, a shared world began to grow.

The effort to understand growth was, in fact, at the heart of this world. Seized by the idea of development, the nineteenth century generated theories of progress and evolution which transformed the way people thought about nature, history, and themselves. From their study

of Goethe, Marian and Lewes learned to see growth as a question at once scientific, philosophical and artistic. When they met Lewes was working on his biography of Goethe, and he finished it during their first year together. It was due to Goethe’s legacy, he explained, that ‘we are now all bent on tracing the phases of development. To understand the grown we try to follow the growth.’

Goethe’s first scientific work was a little treatise titled The Metamorphosis of Plants. Echoing Spinoza, Goethe saw matter and spirit, body and soul, as the ‘twin ingredients of the universe’. A plant, he argued, is not merely a physical thing. It is an archetype, an idea: a fluid pattern and rhythm of growth, expressed in visible form — root, stem, leaf, flower, fruit. George Eliot would carry Goethe’s obsession with form and flux into her fiction, through her inquiry into the ‘process and unfolding’ of human character, and her increasingly daring experiments in literary form.

If we take a plant as our metaphor for marriage, this must be the plant as Goethe envisaged it: essentially in process, simultaneously ideal and real, symbolic and particular, inward and expressive. What I am calling ‘the marriage question’ should also be thought of as a living, growing thing, frequently branching in new directions, always rooted in and reaching out to a world. Eliot’s marriage question was entangled with meanings of marriage expressed in customs, laws, works of art. It cannot be summed up in a sentence or a paragraph because it stretched through her whole lifetime. It shaped her sense of self, coloured her emotional experience, and continually found expression in her writing.

In pursuit of George Eliot’s marriage question this book will move between biography, philosophy, literary interpretation, and histories of art and religion. It begins with a choice, a momentous day, and a honeymoon; it ends with death, mourning, and another choice.

Within this arc, its structure is thematic as well as chronological. Reading Eliot’s works as she wrote them, we will see her wrestling, in life as in art, with themes that belong to a philosophy of marriage: sanctity and morality, vocation and voice, passion and sacrifice, motherhood and creativity, trust and disillusion, success and failure, destiny and chance, love and loss — and also the nature of philosophy itself.

With its desire to understand human relationships and feelings, its

interest in the form and flux of a life, biography offers another means to expand philosophy into the territory Eliot herself cleared and claimed. By showing how Eliot’s thought grew, biography becomes a medium for philosophical inquiry.

*

Though Eliot and Lewes socialized with many eminent intellectuals and artists during their later years together, the core of their double life was what she called a ‘shared solitude’. Perhaps this description fits all marriages, though of course the experience of solitude can range from blissfully contented to desperately lonely. If marriage is a shared subjectivity, then its truth can only be known from the inside. This inwardness belongs to the sanctity of marriage; it is one of the things betrayed when a marriage is violated.

Phyllis Rose’s 1983 book Parallel Lives peered inside the marriages of five Victorian writers — Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, John Stuart Mill, Charles Dickens and George Eliot — and concluded that Eliot and Lewes had by far the happiest relationship. Was it simply a coincidence that they were the only couple not legally married, and that in this instance the wife was more famous than her astonishingly supportive husband? Or did these exceptional conditions make their partnership freer, less compromised, more authentic? Eliot’s story of marital success seemed the perfect match for Rose’s second-wave feminism. And it is still seductive: we want to watch Eliot flouting convention and having it all — work, love, wealth, fame, even (by a certain definition) motherhood.

Other biographers have tended to share this positive assessment of George Eliot’s unconventional marriage. But as I read her letters and reread her fiction, I feel more and more curious about the image of ‘perfect love’ that both Eliot and Lewes cultivated — at least in part, surely, to prove their critics wrong. How does this defiantly idealized public image connect to the very dark marital interiors portrayed in the novels, with their recurring scenes of ambivalence, brutality and disappointment? Do these scenes retaliate against the moralism that condemned their author, by smashing the façade of respectable marriage? Or do they transmit inward experiences that Eliot knew

first-hand? And how did a woman who once declared that she liked ‘to feel free’ find life with a husband who kept her ‘in a mental greenhouse’, as the Scottish writer Margaret Oliphant once put it? Mrs Oliphant, a widow who churned out dozens of novels, biographies and histories to support her three children, rather envied Eliot’s rarified literary life — but greenhouses can be oppressive as well as nurturing, and are not built for human habitation.

If there were moments when Eliot’s marriage stifled or disappointed her, would she have admitted it? The narrator of Middlemarch suggests that it is ‘not a bad thing’ for wives and husbands to hide their domestic suffering. Our pride demands this, he explains — as if unhappiness were a failure — and Eliot was certainly proud. ‘We mortals, men and women, devour many a disappointment between breakfast and dinner-time; keep back the tears and look a little pale about the lips, and in answer to inquiries say, “Oh, nothing!” Pride helps us; and pride is not a bad thing when it only urges us to hide our own hurts — not to hurt others.’ Daniel Deronda ’s proud young wife Gwendolen Grandcourt believes that revealing her ‘disappointment’ and ‘sorrow’ will bring ‘nothing but a humiliation which would have been vinegar to her wounds’. I am not suggesting that Mrs Lewes was secretly as miserable as Mrs Casaubon, or abused like Mrs Grandcourt, but she might have tasted some of their feelings. At least we might wonder how many tears, how many compromises, how many days of depression and despair a happy marriage can absorb, before its happiness is called into question.

*

It is often said, echoing Plato and Aristotle, that philosophy begins with wonder. Thinking about other people’s relationships tends to begin with wonder, and stay there. The world is full of couples, like it is full of houses: we are surrounded by these everyday mysteries, but we hardly ever get to go inside. Maybe a lighted window now and then lets us glance into the interior of a shared life; we might see a kitchen or a living room, very rarely a bedroom. In our own house, when we were children, we never saw what happened after bedtime when the grown-ups were alone. We didn’t know what they felt

when they touched each other — or when they found themselves far apart.

Some of Eliot’s biographers have speculated about her sex life with Lewes, but we know almost nothing about it. One fourth-hand source has her saying something about birth control and sexual satisfaction — it is not clear whose — early in their relationship; twenty-two years later a close friend saw Lewes seize her hand and kiss it. Eliot seems to have possessed a certain sexual power, particularly over younger women, though it is impossible to say how deliberately she wielded this power, or how it made her feel. Much more certain is the interest in sexuality — its many modes, its fluctuations, its hidden depths, its complexity — that is indirectly yet unmistakably expressed in George Eliot’s writing. Of course, this does not tell us what Eliot herself experienced. It tells us what she thought about, where her imagination could go.

The letters exchanged between Eliot and Lewes were buried with them in Highgate Cemetery. Although this puts the intimate details of their relationship beyond our reach, it is itself revealing. It suggests a deep commitment to the privacy of their marriage, which they nevertheless performed for friends and acquaintances — and increasingly, as George Eliot’s fame grew, for posterity. We might be tempted to think that if we dug up those buried letters we could prise open the black box that recorded the inner workings of their shared life. And it is true that most marriages do contain secrets, which may or may not one day come to light. But they also contain questions, ambiguities, grey areas: zones of conflict and confusion that even the partners themselves struggle to understand, let alone resolve.

For example: how do you tell the difference between protectiveness and control, between love and selfishness, between loyalty and submission? Who has compromised more, sacrificed more, suffered more? Who has the most power? Marriages, like people, are not entirely transparent to themselves, and answers to these questions are perhaps more often decided than discovered.

I think that by a combination of close reading and empathy, and also a little imagination, we can lay our hand on Eliot’s marriage questions. We might already inhabit some of them ourselves. If being ‘Victorian’ now seems synonymous with conventional marriage and

its corseted moral codes, it may be surprising to discover that a novelist as solidly Victorian as George Eliot brings new elasticity to the concept of marriage. Many of the themes she explores in her art — desire, dependence, trust, violence, sanctity — could be transferred to wider, less traditional ideas of married life. In this way, Eliot can be our ‘companion in the struggle of thought’ even when this struggle encounters possibilities which she did not inhabit or imagine.

More biographically, too, Eliot’s unusual circumstances brought her closer to a modern experience of marriage. She was involved with several men before settling down with a long-term partner in her midthirties. She chose not to have children, and navigated relationships with Lewes’s sons. Within a few years of her married life she was earning much more than her husband. Living at once inside marriage and outside its conventions, she could experience this form of life — so familiar yet also so perplexing — from both sides. A successful marriage was never, for this woman, an easy lapse into social conformity, but a precarious balancing act — and people were watching to see if she would fall.

A Note on Names

George Eliot’s biographers must wrestle with the question of how to name her. It is usual to refer to one’s subject by their surname, but here this is a contested issue that bears witness to Eliot’s complex, perhaps fractured identity — due partly to her ambiguous marriage. Calling her by her legal surname, Evans, during the period of her unofficial marriage would reject the title ‘Mrs Lewes’ that she claimed for herself (albeit inconsistently), while calling her Lewes poses the problem of distinguishing her from her partner.

Her name changed several times over her life, and she was known by different names to different people. She was born Mary Anne Evans in 1819, and adopted the name Marian when she moved to London, aged thirty-two. A few people, including Lewes, called her Polly, an affectionate variation on Mary. By the end of the 1850s she was signing herself Marian Lewes or Marian Evans Lewes; some people addressed her as Mrs Lewes, while others refused to do so.

As the voice that speaks through her novels and poetry she is, of course, George Eliot. Preserving the distinction between this purely literary voice and the woman formed by choices and experiences which do not lie on the surface of her pages, I want to call this woman Eliot, the surname she created for herself. I also want to register the shift from her lives as Mary Anne and Marian to her life as an artist, by using whichever name she was chiefly known by as we move through her story. But when did Marian become Eliot? Though she adopted her pseudonym in 1857, for more than two years her identity remained secret and she was George Eliot only to Lewes and her publisher.

I have decided to switch to calling her Eliot in the spring of 1859, when her friend Barbara Bodichon guessed that she was the author of Adam Bede. This moment of recognition was joyous for both women, though its triumph was laced with shame. Three months later she became George Eliot to the world.

Question and Answer.*

“Where blooms, O my Father, a thornless rose?”

“That I cannot tell thee, my child; Not one on the bosom of earth e’er grows, But wounds whom its charms have beguiled.”

“Would I’d a rose on my bosom to lie! But I shrink from its piercing thorn; I long, but I dare not its point defy, I long, and I gaze forlorn.”

“Not so, O my child, round the stem again

Thy resolute fingers entwine—

Forego not the joy for its sister pain, Let the rose, the sweet rose, be thine!”

* When she was twenty-one Mary Ann Evans translated this poem from German to share it with her friend Maria Lewis. It was sent in a letter to Maria dated 1 October 1840.

Setting Sail

She had decided, she had prepared, she had waited, and nally the day arrived. Light came into her room around ve in the morning, and she rose early. It was Thursday, 20 July 1854: today she would not be married to George Lewes, and they would set off on their honeymoon.

She got ready for the journey alone. There were no sisters or bridesmaids to calm her nerves, no wedding dress to be helped into, no father to give her away — her father was dead — but no brother, either; Isaac Evans, like her sister Chrissey, was a hundred miles from London, and knew nothing about Mr Lewes. She had told no one about this day except her friends Charles Bray and John Chapman, who had lent her money for the journey. A secret elopement on borrowed funds was the sort of thing expected of a foolish seventeen-year-old. Marian Evans was not seventeen: she was thirty-four, and leaping into a new life. She was expectant, excited, nervous — what if he didn’t come?

She left her Hyde Park lodgings with her belongings in a carpet bag and took a cab east through the city to St Katherine’s Wharf, where the River Thames is very wide. They had arranged to meet on a steamer bound for Antwerp.

That night, in a lyrical mood, she marked the beginning of her marriage story in her diary. Their journey from London to the Continent was a ‘perfect’ passage into a ‘lovelier’ dawn — and also a passage from ‘I’ to ‘we’:

July 20th 1854.

I said a last farewell to Cambridge Street this morning and found myself on board the Ravensbourne, about ½ an hour earlier than a sensible person would have been aboard, and in consequence I had

20 minutes of terrible fear lest something should have delayed G. But before long I saw his welcome face looking for me over the porter’s shoulder, and all was well. The day was glorious and our passage perfect . . . The sunset was lovely but still lovelier the dawn as we were passing up the Scheldt between 2 and 3 in the morning. The crescent moon, the stars, the rst faint ush of the dawn re ected in the glassy river, the dark mass of clouds on the horizon, which sent forth ashes of lightning, and the graceful forms of the boats and sailing vessels painted in jet black on the reddish gold of the sky and water, made up an unforgettable picture. Then the sun rose and lighted up the sleepy shores of Belgium with their fringe of long grass, their rows of poplars, their church spires and farm buildings.

Life was merging with art: the crossing became a sequence of forms and colours, painted boats and skies shifting from day to night to day again. She was shifting too, not just an observer this time, but the gure at the centre of this ‘unforgettable picture’. Marian was also travelling through a literary landscape. Early in 1853 she had read Charlotte Brontë’s new novel Villette, whose spirited heroine Lucy Snowe sails from London to Labassecour — a ctionalized Belgium — to begin a new life. She arrives in Villette in the middle of the night, nding a dreamlike town full of surprises, populated with faces from the past, like some region of the unconscious. In this uncanny, passionate place Lucy meets an eccentric little man who bears no resemblance to a romantic hero. They fall in love, but the world does not want them to marry. He is generous and kind; with extraordinary care he creates for her a life that is more truly her own. ‘I am preparing to go to Labassecour,’ Marian wrote elusively to Sara Hennell, her closest friend, a few days before she left England with Lewes. Since she was a girl she had inhabited a world of books, which offered both refuge and adventure. She had taken lessons in German and Italian, taught herself Latin from a grammar book, and devoured thick volumes on history, philosophy, religion, art and science. The few books by female authors were novels, and novels were almost always about marriage. In 1852 she read Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, in which the challenge faced by the charming Dashwood sisters is to marry the right men. ‘The Miss Dashwoods were young, pretty and unaffected . . . Elinor had a

delicate complexion, regular features, and a remarkably pretty gure. Marianne was still handsomer . . . her complexion was uncommonly brilliant; her features were all good; her smile was sweet and attractive.’ Marianne Dashwood is sixteen, and believes that ‘A woman of seven and twenty can never hope to feel or inspire affection again.’ Like Austen’s other stories, Sense and Sensibility depicts the brief, heady period in a young woman’s life when she is conscious of her own power to shape her future — a power limited to accepting or rejecting a prospective husband, but nevertheless exhilarating.

Charlotte Brontë’s novels also moved towards marriage, but they explored a different kind of challenge, closer to Marian’s experience and rendered vivid by the intimate intensity of an autobiographical voice. Jane Eyre and Villette ’s Lucy Snowe — plain, impoverished heroines more or less alone in a world made for prettier women — exist on the margins of eligibility, and do not feel entitled to hope for marriage. At eighteen Jane Eyre is clear-eyed and pure-hearted, accomplished and creative, yet she knows this is not enough. ‘I sometimes regretted that I was not handsomer,’ she con des to the reader — ‘I sometimes wished to have rosy cheeks, a straight nose, and a small cherry mouth: I desired to be tall, stately and nely developed in gure; I felt it a misfortune that I was so little, so pale, and had features so irregular and so marked. And why had I these aspirations and regrets? It would be dif cult to say: I could not then distinctly say it to myself; yet I had a reason, and a logical, natural reason too.’

Why does Jane Eyre, like so many women, want to be married? During the 1840s, when Brontë wrote the novel, radical voices were protesting that marriage deprived women of their legal right to own property, earn money, and keep custody of their children if they separated from their husbands. In 1854, the year Marian set sail to ‘Labassecour’, her friend Barbara Leigh Smith published A Brief Summary, in Plain Language, of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women, which explained that ‘A woman’s body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody.’ Smith’s erce ‘Remarks’ on English marriage laws drew attention to the stark difference between single and married women: ‘A woman of twenty-one becomes an independent human creature,’ she wrote, ‘But if she unites herself to a man, she nds herself legislated for, and her condition of life suddenly and entirely changed.

The Marriage Question

Whatever age she may be, she is again considered as an infant.’ Having been ‘courted and wedded as an angel’, a wife is ‘denied the dignity of a rational and moral being ever after.’ When the philosopher John Stuart Mill prepared to marry Harriet Taylor in 1851, he had felt it his duty ‘to put on record a formal protest against the existing laws of marriage’. This feminist husband made ‘a solemn promise’ never to use the controlling powers that would be conferred on him by law once Harriet became his wife.

Less progressive authors were also alert to the unequal dynamics between married couples. Sarah Stickney Ellis’s popular guidebook for wives — dedicated to Queen Victoria — offered tips for dealing with husbands whose upbringing had nurtured ‘their precocious selfishness’ and accustomed them to ‘the triumph of occupying a superior place’. Ellis counselled women to humour their husbands’ egos. ‘It is perhaps when ill, more than at any other time, that men are impressed with a sense of their own importance,’ she observed sagely, and advised her readers ‘to keep up this idea by little acts of delicate attention.’ Any woman who had ‘not yet crossed the Rubicon’ into marriage should, Mrs Ellis urged, ‘look the subject squarely in the face.’ The longest chapter of her book is devoted to ‘Trials of Married Life’: most wives could expect to endure ‘daily and hourly trials’ of bad temper, idleness, pro igacy, fussy eating and ‘causeless and habitual neglect of punctuality’.

‘ “But why then,” ’ asks Ellis, ventriloquizing a young reader, ‘ “all the ne talk we hear about marriage? and why, in all the stories we read, is marriage made the end of a woman’s existence?” Ah! there lies the evil. Marriage, like death, is too often looked upon as the end ; whereas both are but the beginning of states of existence in nitely more important than that by which they were preceded.’

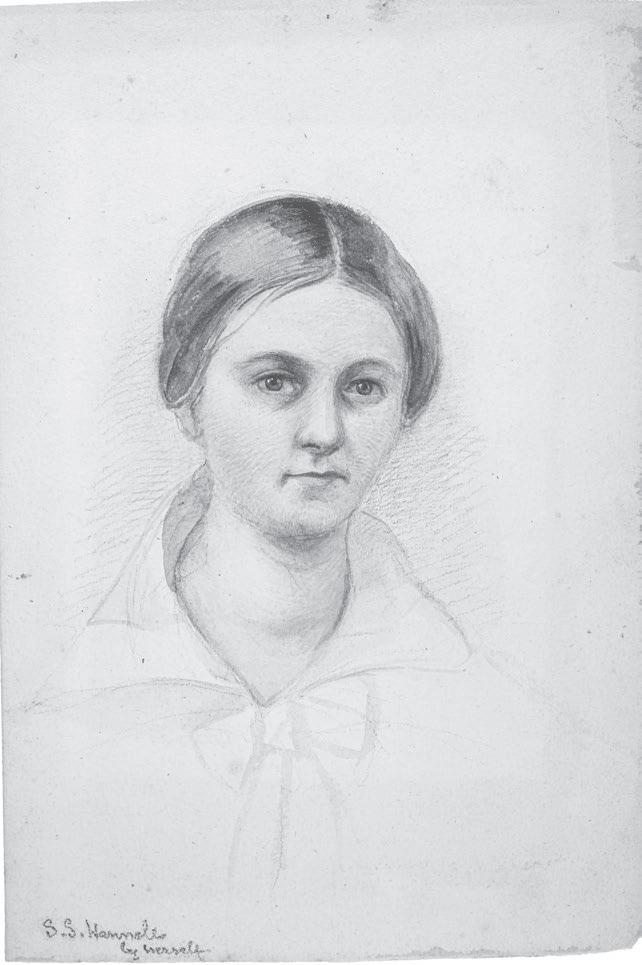

Novels persistently portrayed marriage as a happy ending. Young female readers longed to be ‘courted and wedded as an angel’ — or, if already married, to reimagine this phase of life, so vibrant with possibility. Like Charlotte Brontë’s heroines, Marian Evans struggled with these longings. She had read Jane Eyre in 1848, soon after it was published; then nearly thirty years old, she was, like Jane, conscious of falling far short of the feminine ideal. Though her gure was slender and graceful, she had a large manly nose, a long chin, ‘evasive’ grey-blue eyes, a

formidable intellect and a brooding, sensitive disposition — a ‘temperament of genius’ as her friend Charles Bray put it.

All her life Eliot tended to transform thwarted desire and unspent anger into depression. In her early twenties she had ‘felt a depression’ that, as she wrote to her friend Maria Lewis, ‘has disordered the vision of my mind’s eye and made me alive to what is certainly a fact though my imagination when I am in health is adept at concealing it, that I am alone in the world.’ At that time she was living with her father, and had several close friends; her loneliness revealed her longing for a husband. She could not quite say it outright. ‘I mean,’ she explained delicately, ‘that I have no one who enters into my pleasures and my griefs, no one with whom I can pour out my soul, no one with the same yearnings the same temptations the same delights as myself.’

This need for intimacy was mixed with other yearnings, even harder to confess, for creative ful lment. Throughout her twenties she had lived with the marriage question — not whom she would marry, but whether she could marry — hanging over her. This question seemed less an exhilarating uncertainty than an ominous cloud, growing heavier as the years went by.

*

Now she was with Lewes, and the sun was rising over Europe’s ‘sleepy shores’. But her marriage question, far from dissolving, had taken on a new and unexpected shape. Like Mr Rochester — Charlotte Brontë’s rst ugly, awed, irresistible hero — Lewes had ‘a wife still living’ and could not divorce her, not least because divorces were prohibitively expensive. Agnes Lewes was no end locked in a gothic attic, but a pretty, plump, cheerful woman who had borne Lewes three sons, before having more children by his friend Thornton Hunt.

In 1853 Marian and Lewes had crossed paths in literary London; they became friends, then more than friends. Whatever the state of his marriage, she would be seen to be committing adultery if she lived openly with him. And for the Victorians, being seen to commit adultery was much worse than doing it in secret. Public transgressions not only humiliated those who were betrayed, but also — and this seemed to be the greater sin — threatened social codes of propriety.

The Marriage Question

When Jane Eyre contemplates her future with Mr Rochester after discovering, at the altar, that he is already married, she is resolute. Rochester begs her to travel abroad with him, but Jane chooses to wander into the cold night, homeless and heartbroken, rather than live unmarried with the man she loves. She is eventually rewarded with a large fortune, a blissfully happy marriage, and a baby boy with dark ashing eyes like Rochester’s.

Marian disagreed with the marriage morality of Jane Eyre, and when she faced a similar decision she made the more radical choice. It was a cruel dilemma. Lewes offered a brighter future, and the daily companionship and affection she craved. He had chosen her; at last she could prove to the world that she was worth loving. But now the question of her worthiness would shift from her feminine charm to her moral character. The consequences of a public relationship with Lewes were uncertain, but she knew she might lose her friends. It would have been easier to defy convention if she was aristocratic, bohemian, insouciant — more like George Sand, in other words — and not a lower-middle-class woman from a conservative Anglican family, who harboured ‘a desire insatiable for the esteem of my fellow creatures’.

Her resolve was strengthened by a new philosophy of marriage. During the rst months of 1854, already involved with Lewes, she had translated Ludwig Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity into English. This book argues that the union of a man and woman does not need a church or a priest, since natural human love is ‘sacred in itself’. Like earlier generations of German Romantics, Feuerbach was inspired by a pantheist spirituality which refused to separate God from the world. He saw nature itself — and especially human nature — as divine, and he condemned narrow Christian moralism that treated sensual pleasure as unholy. ‘Life as a whole is throughout of a divine nature. Its religious consecration is not rst conferred by the blessing of a priest,’ argued Feuerbach — and marriage should be ‘the free bond of love,’ not merely ‘an external restriction’. This daring new philosophy made freedom and spontaneous love the essence of a ‘truly moral’ marriage.

‘With the ideas of Feuerbach I everywhere agree,’ Marian wrote to Sara Hennell at the end of April, as she completed her translation — but she did not tell her friend that she was planning to put these ideas

into action. The book was published a couple of weeks before she set sail with Lewes, with her name beneath Feuerbach’s on the cover, as if anticipating the censure to come by de antly asserting her principles. Lewes was not desecrating marriage by leaving his legal wife, and she, Marian Evans, was not just running off with a married man. They were af rming a ‘truly moral’ radicalism.

And now she was entering an uncharted world. In this new dawn she was emerging as an unfamiliar, untested self — what kind of wife would she be? — and quite possibly renouncing her former life. Indeed, she had left more than one old life behind her.

* She had turned sixteen in November 1835. A few months later her mother Christiana died after a long illness, probably breast cancer, and then her elder sister Chrissey left to marry a local man. Her brother Isaac, who had been her best friend and protector when they were children, was already living away from home in Birmingham. On Chrissey’s wedding day Mary Anne and Isaac wept together ‘over the break up of the old home-life’. They were mourning their mother as well as their beloved sister.

Mary Anne now became her father’s chief companion, and mistress of Griff House, her childhood home in Warwickshire. As if to herald a shift in her identity, she altered the spelling of her name to Mary Ann. She was no longer a child; she was becoming a woman — and, at least in theory, eligible for marriage.

Though she had little control over her future, she was able to give literary shape to her inner life, chie y in the form of letters to Maria Lewis, her former schoolteacher, a devout Christian and at that time her closest friend. Following Maria’s example, she had become fervently religious. Her friend embodied one image of her own destiny: a spinster and a governess — a precarious profession, since the need for one’s services was continually being outgrown. In 1839, aged nineteen, she sent Maria an inventory of her mental landscape: ‘disjointed specimens from history, ancient and modern; scraps of poetry picked up from Shakespeare, Cowper, Wordsworth and Milton; newspaper topics; morsels of Addison and Bacon, Latin verbs, geometry,

Griff House

Griff House

entomology and chemistry, reviews and metaphysics — all arrested and petri ed and smothered by the fast-thickening, everyday accession of actual events, relative anxieties, and household cares and vexations.’ Another day found her ‘plunged in an abyss of books and preserves’, snatching a few minutes in the midst of jam-making to write to her friend.

Her appetite for knowledge and ideas was voracious, yet the woman who would translate Spinoza’s Ethics, edit the Westminster Review and write Middlemarch did not feel entitled to express her intellectual aspirations. Perhaps she was embarrassed by them. Confessing a desire makes a claim on the world — and surely only a woman grander, richer, or at least less plain could have the audacity to imagine herself becoming a great artist? Mary Ann did not tell anyone that she hoped to create an important work of philosophy, or that she wanted to be a writer, widely read and recognized for her genius. Instead she approached these desires sideways, or in reverse. She

could reveal her ‘restless, ambitious spirit’ only in re ecting on her failure to ful l ‘the duty of perfect contentment with such things as we have’. Nevertheless there was a grandeur to her half-spoken ambition, which protested against her ‘walled-in world’ by invoking Shakespeare, Carlyle, Wordsworth and Byron. Her sense of dwelling in ‘a small room’ that cramped her ‘instinctive propensity to expand’ often made her unhappy. Squandering her gifts in intensely literary letters to a Midlands governess clouded her heart with an anxiety she could not explain. Instead she made jokes to belittle herself, or wallowed guiltily in repressed frustration. ‘I have a world more to say, and am very fertile in thoughts that like many greater productions are born to die in unregretted obscurity,’ she wrote at the end of one letter to Maria — ‘How is it that Erasmus could write volumes on volumes and multitudinous letters besides, while I whose labours hold about the same relation to his as an anthill to a pyramid or a drop of dew to the ocean seem too busy to write a few? A most posing query! Solved, after due thought, by the very recondite fact that your poor friend is considerably inferior in mental profundity, power and fertility to the said Erasmus.’

Stuck in her father’s farmhouse, she internalized the constraints of her situation. Her letters to Maria played out an elaborate dialectical dance, offering a ash of her creative power in one sentence, before twisting and withdrawing into self-critique or self-mockery in the next. She denounced as ‘ambition’ her longing to exercise her talents. One day she sent Maria a melancholy sonnet mourning her childish pursuit of a sunlit future, where the grass seemed ‘more velvet-like and green’. Her poem ended with a jaded glimpse ‘Of life’s dull path and earth’s deceitful hope’. Not yet twenty, she was already aestheticizing disappointment, consigning her dreams to the past.

This disappointment was doubled by every glance in the mirror. Her disapproving re ection seemed to forbid even the ordinary feminine ambition to be fallen in love with, let alone her hidden hope to create something extraordinary. Finding a husband was a matter of making a home in the world, and she envisaged herself an outsider. On receiving news from Maria of a friend’s imminent marriage, she cast herself as the Greek philosopher Diogenes the Cynic, a subversive performance artist who lived on the streets of ancient Athens in a clay barrel:

The Marriage Question

When I hear of the marrying and giving in marriage that is constantly being transacted I can only sigh for those who are multiplying earthly ties which though powerful enough to detach their heart and thoughts from heaven, are so brittle as to be liable to be snapped asunder at every breeze. You will think I need nothing but a tub for my habitation to make me a perfect female Diogenes . . .

But she did not disdain marriage; on the contrary, she might have wanted it too much. Channelling her desires into an evangelical fervour, she found spiritual reasons to abstain from the ‘earthly bliss’ of human love. Perhaps others could ‘live in near communion with God’ while relishing ‘all the lawful enjoyments the world can offer,’ she wrote to Maria, ‘but I confess that in my short experience and narrow sphere of action I have never been able to attain this; I nd, as Dr Johnson said respecting his wine, total abstinence much easier than moderation.’ Her complex, crowded sentences, blending earnestness and irony, evoke an inward struggle to keep desires deemed immoderate, unacceptable, under tight control.

In 1840 she was attracted to her tutor Joseph Brezzi, who taught her Italian and German: she found him ‘anything but uninteresting, all external grace and mental power’. This plunged her into acute selfdoubt and fear for the future, ‘such a consciousness that I am a negation of all that nds love and esteem as makes me anticipate for myself — no matter what’. As she approached her twenty- rst birthday, her sense of being excluded from marriage, and at odds with worldly ways, became less pious and more anguished. She remained painfully ambivalent, fearful of her own excessive passion:

Every day’s experience seems to deepen the voice of foreboding that has long been telling me, ‘The bliss of reciprocated affection is not allotted to you under any form. Your heart must be widowed in this manner from the world, or you will never seek a better portion; a consciousness of possessing the fervent love of a human being would soon become your heaven, therefore it would be your curse.’

At a party she stood in a corner, unable to join in the dancing and irting. Her head ached and throbbed, and by the end of the evening she had succumbed to ‘that most wretched and pitied of af ictions, hysteria, so that I regularly disgraced myself’.

All this misery did not make her any more attractive to potential suitors. Through those years the possibility of marriage glowed and pulsed in her psyche, a danger zone, tantalizing and terrifying, exposing her longing for love and her dread of rejection.

*

Another fresh start came as she turned twenty-one and left her childhood home, moving with her father to a house near Coventry. Torn from her roots, she experienced this move as ‘a deeply painful incident — it is like dying to one stage of existence.’ But the new life that replaced the old one was more interesting, bringing new freedom and virtually a new family through friendship with Charles and Cara Bray, a wealthy couple who hosted many thinkers and artists at their home. They were rumoured to have an open marriage. Charles was chronically unfaithful and Cara, people said, was willing to promote her husband’s happiness ‘in any way that his wishes tend’.

In the Brays’ cosmopolitan circle Mary Ann’s talents were recognized and nurtured. Sara Hennell, Cara’s clever, scholarly sister, became her closest con dante. Sara was a few years older, and unmarried; she shared Mary Ann’s philosophical curiosity, her interest in religion, and her literary aspirations. Sara lived with her mother in Hackney, near London, and they exchanged frequent letters. Maria Lewis’s predictable pious thoughts faded into the background as this new correspondence became Mary Ann’s chief medium for exploring her ideas and feelings. Her sentences became more uid and free. Writing to Sara, she could take her intellectual life seriously. ‘I have had many thoughts,’ she reported in one letter, ‘especially on a subject that I should like to work out, “The superiority of the consolations of philosophy to those of (socalled) religion.” ’

Sara, who knew German, became Mary Ann’s rst collaborator. She helped her translate David Friedrich Strauss’s monumental work The Life of Jesus Critically Examined — a task which took nearly two years, since the book was 1,500 pages long. As their intellectual and emotional intimacy grew, it formed the pattern for an ideal marriage. Mary Ann’s letters addressed Sara as ‘Dearly beloved spouse’, or were signed ‘Your loving wife’. For both women this intense friendship was a substitute

love affair. Usually apart, they looked forward to spending time together — ‘I love thee and I miss thee,’ she wrote to Sara in 1846.

Her freethinking Coventry friends and her wide reading quickly drew her to the conclusion that Christianity was based on ‘mingled truth and ction’. For a while she refused to go to church on Sundays. This angered her father, who made it clear that they had moved closer to town to improve her marriage prospects — a favour that would be withdrawn if she rebelled. She resumed her church-going, but marriage eluded her. The closest she came to nding a husband was in her twenty- fth year, when a young artist who restored paintings for a living asked her to embark on a courtship. She said yes. ‘She came to us so brimful of happiness,’ Cara Bray wrote to Sara. Mary Ann ‘had not fallen in love with him yet, but admired his character so much that she was sure she should.’ Her only objection was that his profession was ‘not lucrative or over honourable’.

Having rushed into this courtship, she rushed out of it. When she saw her young man again a couple of days later, he ‘did not seem to her half so interesting as before.’ The next day she concluded that ‘she could never love or respect him enough to marry him and that it would involve too great a sacri ce of her mind and pursuits.’ She wrote to break it off, feeling guilty and upset, but her swift decision when she thought her ‘mind and pursuits’ were threatened clari ed how much these things mattered. While she longed to be married — and though her other prospects were wholly uncertain — she would not compromise her literary ambitions.

The following year she wrote a satirical story about being proposed to, merging these themes of mind and marriage that had clashed so decisively during her engagement crisis. Her story took the form of a letter to Charles Bray describing a surprise visit from a German scholar, Professor Bucherwurm of Moderig University,* author of a commentary on

* Professor Bookworm of Mouldy University

The Marriage Question

the Book of Tobit, a treatise on Buddhism, and ‘a very minute inquiry’ on an ancient Egyptian pharaoh. The professor has dirty skin and black teeth, and wears a threadbare coat. He hopes to write a new system of metaphysics — and is ‘determined to secure a translator in the person of a wife’. The translator of Strauss’s Life of Jesus seems an ideal match. Professor Buchenwurm explains that he requires, ‘besides ability to translate, a very decided ugliness of person . . . After the most toilsome inquiries I have been referred to you, Madame, as presenting the required combination of attributes, and though I am rather disappointed to see that you have no beard, an attribute which I have ever regarded as the most unfailing indication of a strong-minded woman, I confess that in other respects your person at least comes up to my ideal.’

Mary Ann is surprised, ‘having long given up all hope’ of marriage. She accepts immediately — ‘For you must know, learned Professor, that I require nothing more in a husband than to save me from the horri c disgrace of spinster-hood and to take me out of England.’ She briskly sets out her terms:

My husband must neither expect me to love him nor to mend his clothes, and he must allow me about once in a quarter a sort of conjugal saturnalia in which I may turn the tables upon him, hector and scold and cuff him. At other times I will be a dutiful wife so far as the task of translation is concerned.

She also vows to do her best to grow a beard. They consult her father, who consents, ‘considering that it would probably be my last chance’ — and so ‘on Wednesday next I become the Professorin and wend my way to Germany — never more to appear in this damp atmosphere and dull horizon.’

Naturally, she has thought about clothes, and is planning a bridal look inspired by Joan of Arc: ‘I have ordered a magni cent wedding dress just to throw dust into the eyes of the Coventry people, but I have gone to no further expense in the matter of trousseau, as the Professor prefers as a female garb a man’s coat, thrown over what are justly called petticoats so that the dress of a woman of genius may present a symbolical compromise between the masculine and feminine attire.’ She

has asked Sara to be her bridesmaid, and hopes Charles will come to the wedding.

It is all there in three witty pages: her erudition, her scholarly accomplishments, her anxiety about looking masculine and not being beautiful, her wish to please her father, her sense of disgrace at being unwanted, her pleasure in intellectual companionship, her longing for new horizons, her de ant humour — all except love, which even in this fantasy she denies herself. The jaunty prose and brave selfmockery belie the old pathos: the marriage question still pressed upon her and now, entering her late twenties, time was running out.

*

She did not repeat her mistake with the picture restorer. The men she went on to fall more or less in love with were — like Sara Hennell — intellectuals who understood her ambitions and helped her to pursue them. Through the Brays she met John Chapman, a handsome young publisher who dealt in ideas, theories, philosophies. He published her translation of Strauss. In 1851 he acquired the Westminster Review, London’s leading progressive journal, and invited Mary Ann to lodge in his house on the Strand and help him to edit it.

By then her father had died, leaving her a small income. She had travelled to the Continent with the Brays and stayed on alone in Geneva for a few months. She began to imagine making a living as a woman of letters. To mark her break from provincial life she changed her name to Marian Evans.

When she rst moved into 142 the Strand, her intimacy with Chapman complicated an already fraught ménage à trois between the publisher, his wife, and his mistress. The other two women formed a brief alliance and she was cast out. But after this crushing start she was persuaded to return to Chapman’s house — he needed her editorial skills — and settled into being his friend and colleague. He had opened the door to another new life, right at the heart of literary London.

At the Westminster Review she commissioned, edited and wrote reviews of new works of philosophy, science, history, politics, ction and poetry. Soon she was effectively running the journal, holding its eminent contributors — and Chapman himself — to high standards.