CHARLIE HIGSON

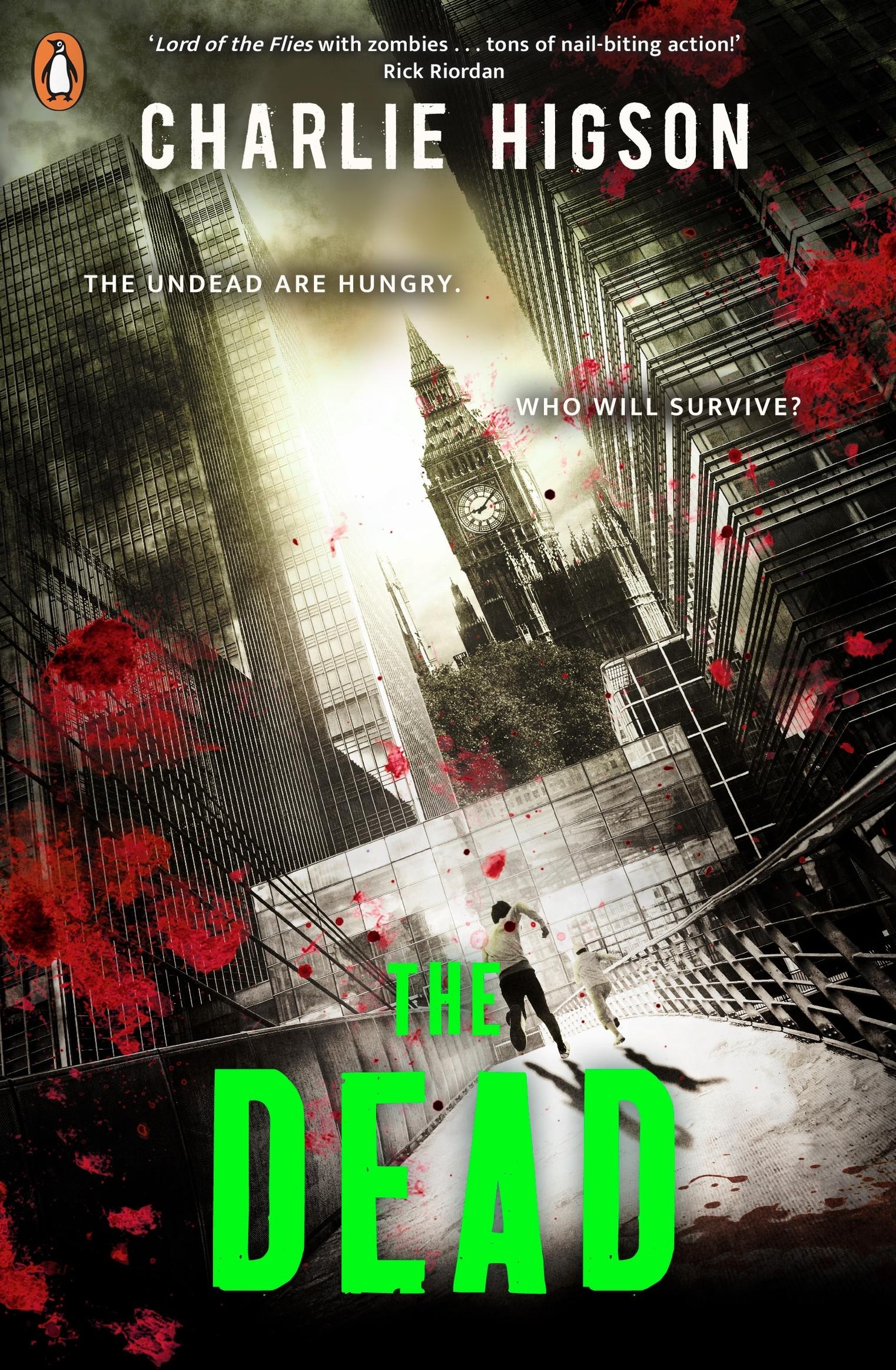

‘Lord of the Flies with zombies . . . tons of nail-biting action!’ Rick Riordan, global bestselling author of the Percy Jackson series

‘The Enemy scores high with its brutal vision of a post-apocalyptic world’ Financial Times

‘Clever . . . fast paced . . . inventive’ Guardian

‘Higson has got the balance of blood and gore just right’ Daily Mirror

‘Brutal, blood-soaked, full of zombies . . . It’s ace’ FHM

‘Adrenaline-inducing’ Sunday Times

‘Entertainment of the highest calibre’ Books Quarterly

‘Ruthless’ SFX

‘Good, gritty and funny’ Daily Mail

‘Charlie Higson’s Young Bond books get an A*’ GQ

Books by Charlie Higson

The Young Bond series: silverfin blood fever double or die hurricane gold by royal command

danger society: young bond dossier

silverfin: the graphic novel

The Enemy series: the enemy the dead the fear the sacrifice the fallen t he h unted t he e nd monstroso (pocket money puffins)

The dead CHARLIE HIGSON

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com. www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published by Puffin Books 2010

Reissued by Penguin Books 2013 Reissued in this edition by Penguin Books 2025

Copyright © Charlie Higson, 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in Bembo MT 11.2/14.5 pt

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 978–0–141–32503–3

All correspondence to: Penguin Books

Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Amanda – for everything

For Alex

I have a lot of help from some wonderful people in researching parts of this series, but I would especially like to thank:

James Taylor and Terry Charman at the Imperial War Museum.

David Cooper at the Tower of London.

Daniel Armstrong at Waitrose Holloway Road for helping me to understand how supermarkets work.

And Jon Surtees at the Oval for a great guided tour that was slightly wasted on a non-cricket fan like myself.

I would thoroughly recommend a visit to any of these fine institutions, whether you want to check out the locations from the books or whether you are interested in English history and culture.

The Scared Kid

When the video is posted on YouTube it’s an instant hit. Within days everyone’s talking about it.

‘Have you seen the “Scared Kid” video?’

‘It’s really freaky.’

‘At first I thought it was a joke, but it looks so real.’

‘It’s definitely fake, but it’s still scary.’

‘I can’t watch it. It’s too frightening.’

‘Who is he? Do you know who he is? Who’s the Scared Kid?’

‘Nobody knows . . .’

Maybe it’s a clever trailer for a new horror film? Maybe it’s a viral ad for something. A new car or a chocolate bar? Or just maybe it’s real . . .

There’s something about it. Something about the kid. No ten-year-old is that good an actor. And if someone’s playing a trick on him they are really sick and they’ve done way too good a job. Who would do that? Who would deliberately scare a young kid that much? And why has nobody come forward to explain it all?

Even after everything that happens, when the whole world changes forever, when everyone knows that the video wasn’t a hoax, but the start of something terrible, people will remember the Scared Kid. His poor frightened little face.

It’s like the last thing everyone saw before the lights went out.

He sits there at his computer talking into a web cam. It’s clear he’s been crying for ages, his eyes are red raw, his face streaked with tears. He’s shaking uncontrollably and his teeth are actually chattering. You can hear them. It would be funny if it wasn’t so weird. He can hardly get his words out. They tumble over each other.

‘I don’t know what to what to do I don’t know they’ve killed Danny and Eve they killed Danny and Eve Danny and and Eve and Eve and and . . . they’re outside now I can see them I can see them outside there are three mothers and a father . . .’

That’s the freakiest bit, the bit that sticks in people’s minds, that he calls them mothers and fathers.

‘They came to the house and they killed they killed Danny and Eve there’s blood omigod – omigod there’s blood three mothers and a father they’ve killed Danny and Eve make them go away please make them go away . . .’

Then he picks up the web cam and turns it to point out of the window. It veers all over, lights smearing the screen. Now you can see the street. It’s night-time. The picture’s awful but you can just see these four people under the street lights – three mothers and a father – three women and a man, and near to them what looks like a dead body. The body of a child.

There’s something not right about the people. They don’t look like actors. The way they’re standing. And when one of them looks up at the camera it’s the most awful thing . . . a dead-eyed look, like an animal. Are they actors? The picture’s so bad it’s hard to tell.

Then the Scared Kid’s voice again.

‘Can you see them? They’ve gone crazy – three mothers and a father – they’ve been trying to get back in into the house but Danny and Eve they’re dead they’re dead and I don’t know where my mum and dad are there’s nobody else here they’ve all gone it’s only me . . .’

The camera moves again. You can hear crashing and smashing in the background. Shouting. Now the kid’s back at his desk, staring into the lens, like he’s staring into the grave. Even more terrified than before. Shaking. Shaking.

‘I’m going to post the video – Danny showed me how – they killed him three mothers and a father I have to do it quickly I don’t know what’s happening I don’t think anyone will help me I think I’m going to die like like . . .’

And that’s the end of it.

Some other kids do impressions of him, and post them. There’s a remix of the kid done to a death metal soundtrack. But the thing is – the video is scary because it seems so real. People watch it over and over, trying to understand it. And when adults start dying, when it becomes clear that some terrible new disease is striking everybody over the age of fourteen, the Scared Kid begins to look like some kind of prophet.

Within a very short time ‘Scared Kid’ becomes the most watched YouTube clip ever. After a month it’s taken down. There’s a message saying it’s been removed. The day after that the whole YouTube site is taken down without any explanation.

And the day after that the Internet stops working. It just disappears.

That’s when people finally realize that something serious is happening.

Mr Hewitt was crawling through the broken window. Sliding over the ledge on his belly. Hands groping at the air, fingers clenching and unclenching, arms waving as if he was trying to swim breaststroke. In the half-light Jack could just make out the look on his pale yellowing face. A stupid look. No longer human. Eyes wide and staring. Tears of blood dribbling from under his eyelids. Tongue lolling out from between cracked and swollen lips. Skin covered with boils and sores. Jack stood there frozen, the cricket bat held tight in sweating hands. He knew he should step forward and whack Mr Hewitt as hard as he could in the head, but his right arm ached all the way down. He’d been swinging the bat all night and the last teacher he’d hit had jarred his shoulder. Now it hurt just to hold the bat, which felt like a lead weight in his hands.

He knew that wasn’t the real reason, though. When it came down to it, he couldn’t bring himself to hit Mr Hewitt. He’d always liked him. He’d been Jack’s English teacher for the last year. He was one of the youngest and most popular teachers in the school, always talking to the boys about films and TV and console games, not in a creepy way, not to get in with the kids, simply because he was genuinely interested in the same things that they were. When the disease hit,

when everything started to go wrong, Mr Hewitt had done everything he could to help the boys. Trying to contact parents and make arrangements, keeping their spirits up, comforting them, reassuring them, always searching for food and water, making the buildings safe . . .

And when it had got really bad, when those adults who’d got sick but hadn’t died had started to turn on the kids, attacking them like wild animals, Mr Hewitt had helped fight them off

He’d been tireless and it had looked like he might escape the sickness.

He’d been a hero.

And now here he was, crawling slowly, slowly, slowly into the lower common room like some huge clumsy lizard. He raised his head, stretching his neck, and wheezed at Jack, bloody saliva bubbling between his teeth. Jack could see two more teachers behind him, attempting in their own mindless way to get to the window.

Jack swallowed. It hurt his throat. He hadn’t had anything to drink all day. They were running low on water and trying to ration it. His head throbbed. This was the second night the teachers had attacked in force. Jack’s second night without sleep. The stress and the tiredness were turning him slightly crazy. His heart felt all fluttery and he was constantly on the edge of losing it, breaking down into uncontrollable sobbing, or laughter, or both. He was seeing things everywhere, out of the corner of his eye, shapes moving in the shadows. He would shout a warning and turn to look and there would be nothing there.

Mr Hewitt was real, though, something out of a waking nightmare, slithering in, inch by inch.

The last hour had been a chaotic panicked scramble of

running around in the dark from room to room, checking doors, windows, battering back any teachers that got past the defences. And then they’d heard breaking glass in the lower common room, and he and Ed had come charging in to see what was happening.

And there was Mr Hewitt.

Jack couldn’t do this alone. He looked for Ed and saw him crouched down behind an overturned table, his grey face poking over the top, eyes white-rimmed and staring. Ed, his best mate. Ed who everyone thought was cool. Clever without being cocky or a suck-up. Good-looking Ed who all the girls went for. Ed who beat him at tennis without really trying. Jack had always felt second in line to him, even though the two of them did everything together, hung out all the time, shared books and comics and music, played on the same football team, the same cricket team.

Last year the school had produced a glossy booklet advertising itself to new parents, and there on the front cover was Ed – the boy most likely to succeed. The happy, smiling, confident face of Rowhurst.

Well, this was the new face of the school, hiding behind a table, scared halfway to death, while the teachers crawled in through a broken window.

Ed reminded Jack of someone.

The Scared Kid.

Ed was totally bricking it, and his fear was making him next to useless.

‘Help me,’ Jack croaked.

‘I’m keeping watch,’ said Ed, a slight catch in his voice. Yeah, right, keeping watch . . . Keeping safe more like.

Jack sighed. His own tiredness and fear were turning him bitter.

‘If you won’t help,’ he said, ‘at least go and get one of the others.’

Ed shook his head. ‘I’m staying with you.’

‘Then do something,’ Jack shouted. ‘Hewitt’s nearly through. I need help here.’

‘What . . .? What do you want me to do?’

Jack rubbed his shoulder. He’d had enough of the school. He’d had enough of this mess, night after night, the same bloody ritual. Right now he’d rather be anywhere else than here.

Most of all he wanted to be at home, though. Back in his own house, in his own room, with his own things. Under his duvet, with the world shut out.

Home . . .

He tossed the bat to Ed. It bounced off the table and ended up on the carpet.

‘Hit him, Ed,’ he said.

‘I’m not sure I can,’ Ed replied.

‘Pick up the bat and hit him.’ Jack felt tears come into his eyes and he squeezed them tight then pinched the wetness away.

‘Please, Ed, just hit him.’

‘And then what?’ Ed asked. ‘They just keep coming, Jack. We can’t kill them all.’

‘Hit him, Ed! For God’s sake, just hit him!’

Ed looked at the bat, lying in a strip of moonlight on the worn-out carpet. The electricity had gone off three weeks ago. Nights were blacker than he had ever known they could be.

He didn’t know what to do. He knew he should help Jack, but he was paralysed. If he did nothing, though, wouldn’t it be worse? The teachers would get him, just as they’d got Jamey and Adam and Will. They’d come in with their horrible filthy nails and their hungry teeth. They’d grab him . . .

Maybe that would be better. To get it over with. All he could see ahead of him was a never-ending string of dark nights spent fighting off adults, as, one by one, his friends were all killed.

Get it over with.

Shut your eyes, lie down and that would be that . . . He saw a hand reaching out towards the bat. As if he was watching a film. As if it was happening to someone else. The fingers closed around the handle.

His fingers.

He picked up the bat and raised himself into a standing position. The blood was pounding in his head and he felt like he was going to throw up at any moment. If he came

out from behind the table and ran forward now, he could get Mr Hewitt before he was fully through the window and on to his feet. He could help Jack. They’d be OK.

Yes.

He pushed the table out of the way and crept forward. What if Mr Hewitt sped up, though? What if all the diseased adults weren’t slow and confused? It was easy to make a mistake. Every boy who’d been taken had made some stupid mistake. Had been careless.

Ed raised the bat just as Hewitt flopped on to the floor. For a moment he lay there, unmoving. Ed wondered if he was dead. Then the teacher rolled his head from side to side and forced himself up so that he was squatting on the sticky carpet. He belched and vomited a stream of thin clear liquid down his front. It smelt awful.

‘Hit him, Ed.’

Ed glanced over at Jack. He was stooped over, breathing heavily, his eyes wild and shining. Exhausted. The strawberry birthmark that covered one side of his face and gave him a permanently angry look was like a splash of blood.

‘Hit him now.’

When Ed turned his attention back to Mr Hewitt, the teacher had straightened up and was shuffling closer. There were three long jagged tears down the front of his white shirt. Ed’s eyes flicked to the window frame where a row of vicious glass shards stuck up along the lower rim. Mr Hewitt must have raked his torso across them as he crawled in, too stupid to realize what was happening. Blood was oozing from behind the rips and soaking his shirt. His tie had been pulled into a tight, stringy knot.

There was a noise from outside. Already other shapes were at the window, jostling with each other to get through.

Hewitt suddenly jerked and lashed out with one hand. Ed staggered back.

‘Hit him, Ed,’ Jack hissed angrily, on the verge of crying. ‘Smash his bloody skull in. Kill him. I hate him. I hate him.’

The thing was, Ed hadn’t hit a single one of them yet and he didn’t know if he could. He didn’t know if he could swing that bat and feel it smash into bone and flesh. He’d never enjoyed fighting, had always managed to avoid anything serious. The fact that most people seemed to like him and wanted to be his mate had kept him out of trouble. He’d grown up thinking it was wrong to hit someone else, to deliberately hurt another person.

And not just any person. It was Mr Hewitt, who until about two weeks ago had been friendly and normal . . .

Normal. How Ed longed for things to be normal again. Well, they weren’t ever going to be normal again, were they? So swing that bloody bat. Feel the bone break under it . . .

He swung. His heart wasn’t in it, though, and there was no force to the blow. The bat bumped feebly into Mr Hewitt’s arm, knocking him to the side. Hewitt snarled and lunged at Ed who cried out in alarm and jumped backwards. One of the table legs poked him in the back, winding him and knocking him off balance. He fell awkwardly, his head bashing against the table. He lay there for a moment in stunned confusion until a shout from Jack brought him back to his senses.

Where was the bat? He’d dropped the bat. Where was it?

It had fallen towards Mr Hewitt who had stepped over it. Ed couldn’t get to it now and neither could Jack. Not without shoving Hewitt out of the way.

And Hewitt was nearly on him. There was just enough light to see the pus-filled boils that were spread across his

face. He raised both his hands to chest height, ready to make a grab for Ed, and his shirt pulled out of his trousers.

‘Help me, Jack!’

But before Jack could do anything there was a bubbling, gurgling sound, like a clogged-up sink unblocking, and an appalling stink filled the room. Mr Hewitt howled. The glass had evidently cut deeper into his belly than any of them had realized. He looked down dumbly as his skin unzipped and his guts spilt out.

Now it was Jack’s turn to vomit.

Mr Hewitt dropped to his knees and started scooping up long coils of entrails, as if he was trying to stuff them back into his body. Jack moved at last. He kicked Hewitt over, grabbed the fallen bat then ran to Ed.

‘Come on,’ he said, seizing Ed’s wrist and pulling him to his feet. ‘We’re getting out of here.’

They bundled out into the corridor and Jack pulled the door shut.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Ed. ‘I can’t do this.’

‘It’s all right,’ said Jack, and he hugged Ed. ‘It’s all right, mate, it’s all right.’

Jack felt weird; it had always been the other way round. Ed helping Jack, Ed cool and in control, gently mocking Jack, who worried about everything. Jack never sure of himself, self-conscious about his birthmark. Not that Ed would ever say anything about it, but it was always there, like a flag. What did it matter now, though? In a list of all the things that sucked in the world his stupid birthmark wasn’t even in the top one hundred.

‘Should we try and block the door somehow?’ said Ed, making an attempt to look like he was in control again.

‘What with?’ said Jack. ‘Let’s just get back upstairs to the others, yeah?’

‘What about the teachers?’ said Ed, looking fearfully at the door.

‘There’s nothing we can do, Ed. Maybe the rest of them will be distracted by Mr Hewitt. I don’t know. Maybe they’ll stop to eat him. That’s all they’re looking for, isn’t it, food? You’ve seen them.’

Ed let out a mad laugh. ‘Listen to you,’ he said. ‘Listen to what you’re saying, Jack. This is nuts. Talking about people eating each other. It’s unreal.’

But Ed had seen them. A pack of teachers ripping a dead body to pieces and shoving the bloody parts into their mouths.

No. He had to try not to think about these things and concentrate on the moment. On staying alive from one second to the next.

‘All right,’ he said, his voice more steady now. ‘Let’s get back to the others. Make sure they’re all OK. We’ve got to stick together.’

‘Yeah.’

Ed took hold of Jack’s arm.

‘Promise me, Jack, won’t you?’

‘What?’

‘That whatever happens we’ll stick together.’

‘Of course.’

Ed smiled.

‘Let’s go,’ said Jack, dragging his torch from his pocket and shining it up and down the corridor. There were heavy fire doors at either end that the kids kept shut to slow down any intruders. This part of the corridor was empty. They had to keep moving, though. They had no idea how long the other teachers would be delayed in the common room.

Ed suddenly felt more tired than he’d ever felt in his life. He wasn’t sure he had the energy just to put one foot in front of the other. He knew Jack felt the same.

Then one of the fire doors banged open and Ed was running again.

A teacher had lurched through. Monsieur Morel, from the French department. He’d always been a big, jolly man,

with dark, wavy hair and an untidy beard; now he looked like some sort of mad bear, made worse by the fact that he seemed to have found a woman’s fur coat somewhere. It was way too small for him and matted with dried blood. He advanced stiff-legged down the corridor towards the boys, arms windmilling.

The boys didn’t wait for him; they flung themselves into the fire door at the opposite end but as they crashed through they collided with another teacher on the other side. He staggered back against the wall. Without thinking, Jack lashed out with the bat, getting him with a backhander to the side of the head that left him stunned.

Jack and Ed came to a dead stop. This part of the corridor was thick with teachers. God knows how many of them there were, or how they’d got in. Even though they were packed in here, there was an eerie silence, broken only by a cough and a noise like someone trying to clear their throat.

Ed flashed his torch wildly around, and almost as one the teachers turned towards him. The beam whipped across a range of twisted, diseased faces, dripping with snot, teeth bared, eyes staring, with peeling skin, open wounds and horrible grey-green blisters.

They were unarmed and weakened by the sickness, but they were still larger and on the whole more powerful than the boys, and in a big group like this they were deadly. The boys had fortified one of the dormitories on the top floor where they were living, but there was no way Jack and Ed could make it to the stairs past this lot.

They couldn’t go back and try another way, though, because Monsieur Morel was even now pushing through the fire door, and behind him was a small group of female teachers.

‘Coming through!’

There was a loud shout and Ed was dimly aware of bodies being knocked down, then Morel was shunted aside as a group of boys charged him from behind. At their head was Harry ‘Bam’ Bamford, champion prop forward for the school, and bunched next to him in a pack were four of his friends from the rugby team, armed with hockey sticks. They yelled at Jack and Ed to follow them and cleared a path between the startled teachers who dropped back to either side. The seven boys had the muscle now to power down the corridor and into the empty entrance hallway at the end. They kept moving, Ed running up the stairs three steps at a time, all tiredness forgotten.

They soon reached the top floor and hammered on the dormitory door.

‘Open up! It’s us!’ Bam yelled. Below them the teachers were starting to make their way on to the stairs.

There were muffled voices from the dorm and sounds of activity.

‘Come on,’ Jack shouted. ‘Hurry up.’

Monsieur Morel was coming up more quickly than the other adults, his big feet crashing into each step as his long, muscular legs worked like pistons, eating up the distance.

At last the boys could hear the barricade being removed from the other side of the door. They knew how long it took, though, to move the heavy wardrobe to the side, shunting it across the bare wooden floorboards.

There had to be a better system than this.

Jack turned. Morel was nearly up.

‘Get a move on.’ Ed pounded his fists on the door, which finally opened a crack. The boy on the other side put an eye to the gap, checking to see who was out there.

‘Just open the bloody door,’ Bam roared.

Morel reached the top of the staircase and Jack kicked him hard in the chest with the heel of his shoe. The big man fell backwards with a small, high-pitched cry, toppling down the stairs and taking out a group of teachers on the lower steps.

The door swung inwards. The seven boys made it through to safety.

The adults were scraping the dormitory wall with their fingers and battering at the door. Now and then there would be a break, a few seconds’ silence, and the boys would hear one of them sniffing at the crack down the side of the door like a dog. Then the mindless frenzy of banging and scratching would begin all over again.

‘Do you think they’ll give up and go away?’ Johnno, one of the rugby players, was standing by the heavy wardrobe that the boys used to barricade the door. He was staring at it, as if trying to look through it at the adults on the other side.

‘What do you reckon?’ said Jack, with more than a hint of scorn in his voice.

‘No.’

‘Exactly. So why ask such a stupid question?’

‘Hey, hey, hey, no need to start getting at each other,’ said Bam, stepping over to put an arm round his friend’s shoulder. ‘Johnno was just thinking out loud, weren’t you, J? Just saying what we’re all thinking.’

‘Yeah, I know, I’m sorry,’ said Jack, slumping down on to a bed and running his fingers through his hair. ‘I’m all weird inside. Can’t get my head straight.’

‘It’s the adrenalin,’ came a high-pitched, squeaky voice

from the other side of the room. ‘The fight or flight chemical.’

‘What are you on about now, Wiki?’ said Bam, with a look of amusement on his broad, flat face. Wiki’s real name was Thomas. He was a skinny little twelve-year-old with glasses who seemed to know everything about everything and had been nicknamed Wiki, short for Wikipedia.

‘Adrenalin, although you should properly call it epinephrine,’ he said in his strong Manchester accent. ‘It’s a hormone your body makes when you’re in danger. It makes your heart beat faster and your blood vessels sort of open up so that you’re ready to either fight off the danger or run away from it. You get a big burst of energy, but afterwards you can feel quite run down. It’s made by your adrenal glands from tyrosine and phenylalanine, which are amino acids.’

‘Thanks, Wiki,’ said Bam, trying not to laugh. ‘What would we do without you?’

Wiki shrugged. Before he could say anything else there was an almighty bang from outside and all eyes in the room turned back to the door.

Ed looked around at the grubby faces of the boys, lit by the big candles they’d found in the school chapel. Some of these boys had been his friends before, some he’d barely known. They’d been living in this room together now for a week and he was growing sick of the sight of them.

There was Jack, sitting alone chewing his lip, the fingers of one hand running backwards and forwards over his birthmark. Bam with his four rugby mates, Johnno, Piers and the Sullivan brothers, Damien and Anthony, who had a reputation for being a bit thick and had done nothing to prove that they weren’t. Little Wiki and his friend Arthur, who almost never stopped talking. A group of six boys from Field House, over the road, who stuck together and didn’t say

much. Kwanele Nkosi, tall, elegant, and somehow, despite everything, always immaculately dressed. Chris Marker, sitting by the window, reading a paperback book (that’s all he did now, read books, one after another; he never spoke) and ‘the three nerds’, who were all in Ed’s physics class.

Nineteen faces, all wearing the same expression: dull, staring, slack, slightly sad. Ed imagined this was what it must have been like in a trench in the First World War. Trying not to think about tomorrow, or yesterday, or anything.

Apart from the nineteen boys in this room, Ed was alone in the world. He had no illusions that his mum and dad might still be alive. About the only thing the scientists had been able to say for sure about the disease, before they, too, had got sick, was that it only affected anyone over the age of fourteen. His brother, Dan, was older than him, eighteen, so he’d probably be dead, too, or diseased, which was worse. The last contact Ed had had with his family was a phone call from his mum about four weeks ago. She’d told him to stay where he was. She hadn’t sounded well.

There were probably other boys around the school, hiding in different places. He knew that Matt Palmer had taken a load over to the chapel, but basically Ed’s world had shrunk down to this room.

These nineteen faces.

It scared him to think about it. How shaky his future looked. He felt like a tiny dot at the centre of a vast, cold universe. He didn’t want to think about what was outside. The chaos in the world. How nothing was as it should be. It had been a relief when the television had finally shut down. No more news. He had to concentrate on himself now. On trying to stay alive. One day at a time. Hour by hour, minute by minute, second by second.

‘How many seconds in a lifetime, Wiki?’ he asked.

Wiki’s voice came back thin but sure. ‘Sixty seconds in a minute, sixty minutes in an hour, twenty-four hours in a day, three hundred and sixty-five days in a year, actually three hundred and sixty-five and a quarter because of leap years, so let’s say the average life is about seventy-five years, that’s sixty, times sixty, times twenty-four, which is, er, eighty-six thousand four hundred seconds in a day. Then three hundred and sixtyfive days times seventy-five makes, let me see, twenty-seven thousand three hundred and seventy-five days in seventy-five years. So we multiply those two numbers together . . .’

Wiki fell silent.

‘That’s a big sum,’ said his friend Arthur.

‘Never mind,’ said Ed. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘It’s a lot,’ Arthur added, trying to be helpful. ‘A lot of seconds.’

And too many of them had been spent in this bloody room. They’d dragged beds into here from all round the House, so that they didn’t get split up, but it meant it was crowded, stuffy and smelly. None of them could remember the last time he’d washed, except perhaps Kwanele. He had had his school suits specially made by a tailor in London and used to boast that his haircuts cost him fifty quid a shot. He was keeping himself clean somehow. He had standards to maintain.

The room was made even more cramped by a stack of cardboard boxes at the far end. They’d once contained all their food and bottled water, but there was virtually nothing left now. They had supplies for two more days, maybe three if they were careful. Jack was looking through the pile, chucking empty boxes aside.

There came an even bigger bang and the wardrobe appeared to shake slightly. They’d packed it with junk to

make it heavier and it would need a pretty hefty shove from outside to knock it out of the way, but it wasn’t impossible.

‘We’ve got to get out of here,’ Jack muttered.

‘What?’ Ed frowned at him.

‘I said we’ve got to get out of here.’ This time Jack’s voice came through loud and clear and everyone listened. ‘It’s pointless staying. Completely pointless. Even if that lot out there back off in the morning, even if they crawl back to wherever it is they’re sleeping – which we don’t know for certain they will do – we’re gonna have to spend all day tomorrow going round trying to block up the doors and windows again. And then what? They’ll only come back tomorrow night and get back in. We can’t sleep, we can’t eat. Luckily none of us got hurt tonight, but . . . I mean, if the teachers don’t get us, we’ll basically just starve to death if we stay here.’

‘Yeah, I agree,’ said Bam. ‘I reckon we should bog off in the morning.’ Bam’s voice sounded very loud in the cramped dormitory. He had always had a tendency to shout rather than speak and before the disaster the other boys had found him quite irritating. He was large and loud and boisterous. Blundering around like a mini tornado, accidentally breaking things, making crap jokes, playing tricks on people, laughing too much. Now the others couldn’t imagine how they’d cope without him. He never seemed to get tired or moody; he was never mean, never sarcastic, and totally without fear.

‘We need to find somewhere that we can defend easier than this,’ Bam went on. ‘Somewhere near a source of food and water.’

‘The only source of food around here is us,’ said Jack.

‘They might go away,’ said Wiki’s friend Arthur. ‘They might all die in the night – lots of them are already dead. If we hold on long enough, they’ll all die, they’ll pop like popcorn. You see when Miss Jessop, the science teacher, died? She was lying on the grass in the sun, lying down dead and her skin started to pop like popcorn, the boils on her kept bursting, like little flowers all over her. You see like when flowers come out in a speeded-up film? Pop, pop, pop, and after a while there wasn’t anything left of her, she was just a black mess, and then a dog started to eat her and the dog died, too.’ Arthur stopped and blinked. ‘I think we should stay here until they all go away or pop like popcorn.’

‘They’re not going to go away,’ said Jack, going over to the window where Chris was still reading his book, his eyes fixed on the pages. There was a bright moon tonight, and it threw a little light into the room, but Jack doubted if it was enough to see the words properly. Not that that stopped Chris. Nothing could stop him now.

Jack looked down into the street. There were two teachers down there and an older teenager, maybe seventeen or eighteen. They were hobbling along, walking as if every step hurt their feet.

‘Some of them die from the disease and some don’t,’ he said. ‘Who knows why?’ He turned back from the window to point towards the door where one of their attackers was rattling the handle. ‘And who knows how long that lot out there are going to take to die? Could be weeks, and in the meantime they know we’re here and they won’t give up until they’ve got us. They’re going to keep on attacking, every night, soon as it’s dark, every bloody night. Most of the other boys left ages ago. Us lot, we stayed in case anyone turned

up to rescue us. Ha, good one. Nobody has turned up, and, let’s face it, nobody will.’

‘Two billion three hundred and sixty-five million and two hundred thousand seconds . . .’ said Wiki quietly. ‘Roughly. In a lifetime. If you’re lucky . . .’

It took four of them to shift the wardrobe aside in the morning. Aware that they were moving it for the last time.

Once the door was clear Bam put his ear to it. He looked at Jack. Jack licked his lips, tense.

‘Well?’

Bam shook his head. ‘Can’t hear anything.’

‘Go on then.’

Bam grasped the handle, turned. It clicked and the door popped open a fraction. He checked that everyone was ready. A row of boys stood waiting. They’d pulled the metal bed frames apart to make weapons out of the struts and heavy springs, and they’d packed up whatever supplies and belongings they had left into backpacks or bundles made out of sheets.

‘Ready?’

The boys nodded. Bam took a deep breath and tugged the door open.

A pale, sickly light washing in from the small windows showed that the area outside was empty.

The teachers had gone.

One by one the boys filed out on to the landing, wary and alert. They were shivering. Their combined body heat had kept them reasonably warm in the dormitory, but it was early March and the air out here was noticeably colder.

‘Look at that.’ Johnno nodded towards the door. The outside of it looked like it had been savaged by a pack of wild animals. There were gouges and great dents, long gashes, as if from claws. It was worst round the handle. The teachers had almost managed to scrape right through the wood. The walls were similarly scarred, with chunks missing and a pattern of bloody handprints.

‘Looks like we only just made it out in time,’ said Bam. ‘One more night and they’d have been on us.’

It stank on the landing. There was evidence that at least one of the teachers had used the carpet for a toilet. There was torn wallpaper down the stairs and a fresh splash of blood up one wall. Maybe they’d been fighting among themselves.

‘Come on.’ Bam led the way down. Behind him came Johnno and his other mates from the rugby team, carrying vicious metal lengths of bed frame, with ripped-up sheets wrapped tightly round the ends to protect their fingers. Next came Jack and Ed, Jack with the cricket bat, Ed with a hockey stick. Behind them were Arthur and Wiki, chatting away to each other, wobbling bedsprings up and down in their hands. Then Chris Marker, still reading a book as he walked, a makeshift pack slung over his back crammed with yet more books. Then the three nerds, carrying wooden clubs made from chair legs. After them came Kwanele, immaculate as ever in his suit and tie, lugging an expensive suitcase and suit bag, filled with his favourite outfits. Finally the six boys from Field House, watching their rear and armed with an odd assortment of garden tools.

At the bottom of the stairs the carpet was black and sticky, as if a tub of treacle had been poured into it. The boys’ trainers stuck to the floor and squelched as they lifted their feet. It smelt worse down here, a foul brew of blood

and dead flesh and unwashed bodies. Sweet and sour and putrid.

The main way in and out of the building was through two big double doors. The first thing Mr Hewitt had organized when they’d decided to secure the House was nailing the doors shut with planks of wood. They’d been using an alternative exit through the back of the kitchen as a way in and out, because it was quicker to open and close and easier to lock. They had keys for the back door as well as the kitchen door, so had an extra line of defence. It had turned out to be a complete waste of time, though, as the sick teachers soon found other ways to get into the House.

Bam put a hand over his mouth to block the stink.

‘This way,’ he said, leading the group down the corridor that led towards the kitchen.

It was dark in the corridor and they walked quickly. All the boys wanted to get outside as fast as possible. They soon arrived at the kitchen door, which had a small, reinforcedglass window set in the centre, crisscrossed with a wire mesh.

Bam strode up to it, as eager as the others to be out of here. He took a big bunch of keys from his pocket, selected the right one and slotted it into the lock. He was just about to turn it when Jack pulled him back.

‘Wait a minute.’

Bam stopped. A flash of irritation. Then a little laugh. Jack sighed. ‘Come on, Bam, you could at least check it before you open it.’

‘Sorry, old mate, brain not in gear. Never did work at a hundred per cent, to tell you the truth, turned to mush now. Still asleep, I think.’ He knocked the side of his head with his fist. ‘Wakey, wakey!’

Jack stuck his nose to the little window and peered into

the kitchen. It was dark; the sun rose on the other side of the building and its light hadn’t reached this far yet. He could see no movement in the gloom. Then he spotted that the back door was half open. Someone had definitely been in there during the night.

‘What do you reckon?’ Bam asked. ‘Is it safe?’

‘Hang on a minute. Can’t tell.’

Jack’s eyes were slowly growing used to the light. He was picking out more details in the kitchen. There was a scarlet smear of blood on the window over the sinks. And there, on the table, what looked like a slab of meat. He realized there was an arm still attached to it. He swallowed, trying not to retch.

‘I’m not sure we should go this way,’ he said.

‘Are there some of them in there?’ Bam asked, trying to see over Jack’s shoulder.

‘It’s hard to tell.’

‘Here, let me look.’ Bam shoved Jack aside and took his place at the window.

‘Not a pretty sight, is it? Don’t think there’s anyone in there, though . . . Whoa!’ He leapt back as a female teacher hurled herself at the door, squashing her face against the glass and smearing it with pus. It looked like Miss Warlock, from the English department, but it was hard to tell.

The shock made Bam burst out laughing and soon most of the other boys had joined in. Jack just stared at the door, which shook on its hinges as Miss Warlock repeatedly rammed herself against it with a whining and a slobbering noise.

Ed crept forward and risked looking in.

‘There’s more than one of them in there,’ he said. ‘We’ll have to go another way.’

‘You don’t say,’ Jack murmured.

‘And we need to be quick,’ said Ed, ignoring Jack. ‘They could break this door down if there’s enough of them. Or they might just figure out that there’s another way in –however they all got in last night.’

They backtracked down the corridor, increasingly nervous and anxious to be out of the building that was feeling more and more like a trap. When they got back to the hallway, they headed for the doors.

Jack saw what looked like a football sitting in the middle of the floor. He had an urge to race forward and kick it, an automatic response. He took several paces then came to a dead stop, almost overbalancing, like someone suddenly finding themselves at the edge of a cliff in a cartoon film.

It wasn’t a football. It was a human head. All that was left of Mr Hewitt. His eyes were open, and he looked calm and at peace. He no longer resembled the deranged maniac he’d been when Jack last saw him.

Now Bam spotted the head.

‘Bloody hell,’ he said with a laugh. ‘Better get rid of that. Bit freaky.’

He picked the head up gingerly by the hair then lobbed it across the room towards a waste bin that sat in a dark corner. Amazingly it landed cleanly inside. Bam cheered and punched the air.

‘Shot!’

Jack didn’t know whether to laugh or curl up in a ball and bang his forehead on the floor in despair. He stood there, drained of all energy, wishing he was a million miles away.

Bam, Johnno and Piers, with bits of iron bedstead, set to work on the door, trying to lever the planks off. It was slow work, made slower by the fact that the boys had hardly slept

again in the night and were strung out, awkward and sluggish, their muscles not working as they should, as if the signals weren’t getting through clearly from their brains. In the end Jack couldn’t bear to watch them clumsily struggling to make any headway; he came back to life and went over to help.

As they worked, they could hear the teachers down the corridor, bashing and thumping against the kitchen door.

‘Can’t you hurry up?’ said Kwanele, who was standing back, watching, his luggage sitting neatly at his feet, for all the world as if he was waiting for a train.

‘We’re going as fast as we can,’ said Bam.

‘If you’re in so much of a hurry,’ said Jack irritably, ‘why don’t you help? Or don’t you want to get your clothes messed up?’

‘I’m not very good with my hands,’ said Kwanele, flattening a lapel on his suit jacket. ‘And, yes, I don’t want to ruin my clothes. This shirt is Comme des Garçons.’

Jack shook his head and tutted. If Kwanele wasn’t so ridiculous, the others would have long ago lost patience with him.

There was one last plank left to remove. Bigger and thicker than the others, with about ten fat nails fixing it to the door. The boys were getting in each other’s way and Johnno’s weapon slipped, gouging Piers’ hand. Piers sucked his fingers and swore at him.

There came an almighty crash from the kitchen.

Jack glanced back. Had the door finally given out?

‘Come on, come on,’ he said, as much to the piece of wood as to the other boys. He was scrabbling at the plank with his fingers, trying to prise it loose, and he was so intent on removing it that he lost track of what was going on behind

him. It was only when he heard a high-pitched scream that he turned round.

There were teachers in the hallway. Six of them, including Monsieur Morel, who had his hands at the throat of one of the Field House boys and was shaking him like a doll. The boy’s friends were battering the teacher with their makeshift weapons. The rest of them were being kept back by the Sullivan brothers and the three nerds, who stayed in a tight pack, yelling and screaming abuse.

Ed was with the rest of the boys, who were milling in a frightened circle, not sure what to do.

Johnno gave his iron strut to Jack and snatched a fire extinguisher from a bracket on the wall.

‘You get the door open,’ he shouted. ‘We’ll deal with this lot.’

Ed ran over to help Jack and between them they managed to get the bit of bedstead behind the plank. They pulled down on it with all their weight and with a horrible squealing noise the nails began to pull loose.

Johnno hit the plunger on the top of the extinguisher and a stream of white foam erupted from the hose. He aimed it at the circling teachers, blinding them.

Monsieur Morel was still savaging the boy from Field House. The blows raining down on his back seemed to be having no effect.

With a final screech, the plank popped off the door. Jack grabbed one end and raced back to Morel.

‘Out of the way!’

He swung the piece of wood at the man’s head and it stuck fast. One of the nails must have punched through his skull. Morel stood up, the plank hanging from the back of his head like a huge ponytail. He stretched out an arm towards Jack,

then went stiff and shuddered before falling sideways, knocking over Miss Warlock, who slipped and slithered about on the floor, unable to stand up in a pool of melting foam.

‘Come on,’ Bam yelled from the doorway. ‘Let’s go! Let’s go!’

‘We don’t know what’s out there.’ Ed looked worried.

‘Can’t be any worse than what’s in here,’ Jack shouted as he ran over and pushed past Ed.

Ed closed his eyes and took a deep breath, trying to find some small scrap of courage hidden deep inside.

When he opened his eyes, he realized that he’d been left behind. The others had already gone outside. He hurried after them and found them in a tight pack, blinking in the early-morning light. The boys from Field House looked shell-shocked. Ed realized their friend hadn’t made it. He said nothing. Too sick to speak.

There didn’t appear to be anyone else around out here, but a low moan from behind him caused Ed to turn around. The teachers were emerging from the House, covered in foam. They were too sick to move fast, and the boils and sores covering their skin made them walk as if they were treading barefoot on broken glass, but the boys knew from experience that they wouldn’t stop. Once they started to follow they wouldn’t give up.

‘Leg it!’ Bam shouted, and the boys raced across the open ground towards the main school entrance.

Ed stayed at the back, helping Wiki and Arthur. They were smaller than everyone else and slower. Ed didn’t know what he’d do if one of them got left behind. He urged them on, shouting encouragement, aware all the time that the teachers were steadily lumbering along behind them.

They rounded the end of School House and headed

towards the archway that led out into School Yard. Ed spotted Jack ahead. He was hanging back, staring at the administrative building by the main gates.

What now?

Ed was too scared to stop. He sprinted through the arch, but, as he ran past, Jack grabbed hold of his jacket and pulled him back.

Wiki and Arthur ran on.

‘What’s the matter?’ Ed’s voice rasped in his throat.

‘Can you see that?’ said Jack, and he blinked, as if not wanting to trust his own eyes.

Ed turned in the direction Jack was looking. For a moment he could see nothing.

‘What?’ he said, scared and angry and desperate to get away. ‘What am I looking for?’

‘Over there. The office where the school secretaries work.’

‘What? What is it . . .? Oh, my God.’

There was a girl at the window, hammering on the glass, her mouth forming a silent scream.

‘Who the hell is it?’

‘Dunno. Never seen her before in my life.’ Jack’s voice sounded as dry and croaky as Ed’s.

‘We should keep up with the others,’ said Ed, nervously glancing over to the road where Wiki and Arthur were disappearing from view.

‘We can’t just leave her there,’ said Jack.

‘No . . . I know . . . I didn’t mean that.’

‘Then what did you mean?’

‘I don’t know.’ Ed massaged the back of his neck. Couldn’t think of anything else to say.

‘We’re going to go and help her,’ said Jack. ‘OK?’

Ed turned back towards the archway. There was no sign of the teachers yet, but it was only a matter of time before they came through.

‘OK,’ he said.

A look of relief flooded the face of the girl in the window as they hurried over to the building. She was thin, with long hair and a slightly large nose and mouth. Her cheeks were wet with tears and her eyes red.

The boys gestured for her to open the window. She shook her head and indicated that it was locked.

‘Why doesn’t she just use the door?’ Ed asked as he and

Jack went along to the front entrance. His question was immediately answered as they came upon a small pack of teachers scrabbling in the covered entranceway to get inside.

The two boys backtracked quickly and, luckily, the teachers, too intent on trying to get in, didn’t see them. When they got back to the window, the girl was crying again, and knocking uselessly against the glass with a shoe.

‘That’s no good,’ said Jack. ‘It’s toughened glass.’

Ed tried to control his fear, fighting the urge to suggest that they should leave her, and then he spotted two big green wheelie bins on the other side of the yard.

‘We could use one of them,’ he said, pointing. ‘Like a battering ram.’

‘We’ll try it,’ said Jack, and they raced across the cobbled paving to grab a bin. All the other boys had gone down the road and Ed realized he was alone with Jack in the yard.

No. Not totally alone. The first of the teachers who had attacked them inside was shuffling through the arch, still dripping with foam.

The boys trundled the bin across the cobbles, rattling and banging on its small wheels. The noise sounded like thunder and Ed was scared it would attract the teachers in the porch.

‘Stand back!’ he yelled at the girl when they were close, then he and Jack hoisted the bin up on to their shoulders and, still running, launched it at the window. There was a terrific bang as the window disintegrated. For a few seconds there was no sign of the girl, and then she slowly revealed herself in the empty window frame, looking pale and shocked.

‘Can you climb out?’ Jack asked.

‘I think so,’ said the girl, her accent strange, foreignsounding.

‘Be careful of any broken glass,’ said Ed, remembering

what had happened to Mr Hewitt last night. The girl disappeared again and when she reappeared she was carrying a duvet and some blankets which she draped over the windowsill. Then once more she went off to get something.

‘Get a move on,’ Ed murmured under his breath. The teachers were advancing across the yard, and as they drew closer Ed got a good look at them. Their eyes were yellow and bulging, their skin lumpy with boils and growths, horrible pearly blisters nestling in the folds. They were streaked with foam and one or two of them had bright red blood dribbling from their mouths. One had an ear hanging off. It flapped as he waddled along. Another had some sort of huge fleshy growth bulging out from his shirt, as if he’d swallowed a desk lamp. His whole body was twisted and misshapen.

There was a shout from the window. The girl was standing there with a large plastic carrying-box. She passed it out to Ed and he realized that there was a tabby cat inside it, huddled, terrified and shivering, down at the end. Once the cat was safely out the girl manoeuvred herself over the window ledge and Jack helped her to the ground. Her whole body was shaking and her breathing quick and shallow.

She flung her arms around Jack with a great sob and buried her face in his shoulder, soaking his jacket. She kept saying the same thing over and over, her voice muffled.

‘Thank you, thank you, thank you . . .’

‘We’ve got to keep moving,’ said Jack, pushing her away from him. ‘We’ve got to get away from here.’

The girl nodded and took the cat from Ed. She looked inside the box making little reassuring noises, and then spoke to the cat in what sounded like French.

Ed looked at the teachers. The girl hadn’t seen them. They were getting closer by the second.

‘We need to hurry,’ he said, and the girl tore herself away from the cat, her large eyes very wide. Even like this, her hair a mess, her face blotchy from crying, it struck Ed that she was pretty.

He tugged at her arm, but she resisted.

‘My father,’ she said. ‘I don’t know where is my father.’

‘Who’s your father?’ Ed asked, even though he knew it was a stupid thing to say.

‘Monsieur Morel. He is a teacher here. He was looking after me. But yesterday he goes out. He is feeling sick, he goes for medicine, he does not come back. I wait for him. I wait all through the night. He does not come back.’

The girl stopped. She had finally noticed the panicked look on Ed’s face. She glanced over her shoulder and gasped as she saw the teachers, almost close enough to touch.

Jack snatched hold of her arm and dragged her along, forcing her to run at his side.

‘You’ve got to forget about your father,’ he said. ‘All the adults, everyone over the age of fourteen, gets sick. They die, all right? Or they turn into . . . one of them.’

‘Is he . . . Is he sick?’ said the girl, her voice high-pitched with tension. ‘Is he changed?’

‘No,’ said Ed as they ran out of the school gates. ‘No, he’s not.’

‘Have you seen him?’ asked the girl. ‘You must tell me.’

‘Yes.’ Jack exchanged a pained look with Ed. ‘We saw him. He’s dead. Sorry.’

‘I knew it . . .’ The girl choked out the words then wailed in despair. Jack shook his head at Ed. Best not to say any more. At least neither of them had lied.

Ed hadn’t left the school grounds for a few weeks. It hadn’t been safe. And it was strange seeing the main road with no