Seeking Pleasure in Mumbai

Shreya Kaipa

Shreya Kaipa

“The unconditional claim to public space is only possible once all women and men can walk and loiter without demanding respectability.” (Padkhe)

Preface

My hope for this work is that the women of, from, and related to Mumbai and India have the opportunity to see themselves represented in their lived experiences with fear and ease; in seeking pleasure to their bodies and the city.

Using Mumbai as a site allows me to reveal the incongruencies the city has with women’s rights. This experience speaks broadly to the fear instilled and passed down generationally onto Indian women in the subcontinent and beyond.

Seeking Pleasure in Mumbai

by Shreya KaipaRhode Island School of Design Undergraduate Architecture Thesis

Primary Advisor: Jess Myers

Secondary Advisors: Christopher Roberts, PhD and Carlos Medellin

May 2023

I have included the voices of those in my community whose experiences relate to the city; to join this imagination of a pleasure-based Mumbai. The text of this thesis clarifies and details the embodied experiences of these women.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my thesis advisors: Jess Myers, Christopher Roberts, and Carlos Medellin for guiding me through the process of Thesis and helping me shape the story of this project. Thank you to RISD faculty: Naimah Petigny, Avishek Ganguly, Namita Dharia, Elizabeth Hermann and, those outside the institution: Swati Janu and Meena Agha, for asking pertinent questions and supporting me along the way.

Thank you to my friends: Susanna Yim, Mackenzie Luke, Dway Lunkad, Oromia Jula, Lexi Violet, Anqi Gu, Sophie Weston Chien, and Noah Shipley for insightful conversations, thoughtful critique, and for seeking pleasure with me.

“The unconditional claim to public space is only possible once all women and men can walk and loiter without demanding respectability.” (Padkhe)

Finally, thank you to my fellow women and femme Indian co-creators and family: Mallika Gupta, Reshma Gupta, Anuprita Rao, Nishta Kashyap, Sneha Lakshmi, Kaanchi Chopra, Niyoshi Parekh, Namratha Dhore, my cousin: Neha Thippana, my aunt: Kalyani Sodem, and my mother: Bhagya Sodem for sharing your experiences, engaging in vulnerable conversation, and building this Indian feminist pleasure-filled dream with me.

Preface

My hope for this work is that the women of, from, and related to Mumbai and India have the opportunity to see themselves represented in their lived experiences with fear and ease; in seeking pleasure to their bodies and the city.

Using Mumbai as a site allows me to reveal the incongruencies the city has with women’s rights. This experience speaks broadly to the fear instilled and passed down generationally onto Indian women in the subcontinent and beyond.

I have included the voices of those in my community whose experiences relate to the city; to join this imagination of a pleasure-based Mumbai. The text of this thesis clarifies and details the embodied experiences of these women.

“The unconditional claim to public space is only possible once all women and men can walk and loiter without demanding respectability.” (Padkhe)

Preface

My hope for this work is that the women of, from, and related to Mumbai and India have the opportunity to see themselves represented in their lived experiences with fear and ease; in seeking pleasure to their bodies and the city.

Using Mumbai as a site allows me to reveal the incongruencies the city has with women’s rights. This experience speaks broadly to the fear instilled and passed down generationally onto Indian women in the subcontinent and beyond.

I have included the voices of those in my community whose experiences relate to the city; to join this imagination of a pleasure-based Mumbai. The text of this thesis clarifies and details the embodied experiences of these women.

Introduction

In this thesis, I explore how fear manifests in the women of Mumbai and how pleasure is sought. Over the past summer, I visited the city and country for the first time as a lone traveler. I grew up visiting India on my school summer breaks, but was always sheltered from the “outside world” through the means of gated communities, the family’s car, and exciting malls. Public spaces with “unmannered” men, were deemed unsafe for women and young girls.

Rates of sexual assault and harrassment are extremely common in India; and these experiences embed themselves deep into those living in the country and diaspora. If one is a woman, they are expected to live with restrictions.

My family and community had great fear for my safety as a female foreigner in the country. However, Mumbai is looked up to as the “safest city” in India for women due to its large population of working women, who work late into the night, explore the nightlife, and dress liberally. Despite this being true, I found the fear from my community embodied by most women of the city through their careful decision-making to access public life.

Fear

An awareness of an anticipated or ongoing danger, often inducing an automatic response from the nervous system.

Woman

Anyone that identifies themselves as such. This work acknowledges the identities of those that live alongside and outside the identity of womanhood. Often those that pass as a cis woman, experience the same patriarchal expectations, with even more control and intensity.

Mumbai

The most dense and populated city in India, occupied by over 21 million people with a strong divide between the elite and poor. It’s glamorized as the Bollywood center of India, and known as a place where one without anything can build their dreams. You see migrants from all parts of the country, bustling to support themselves and their families.

In addition, it’s looked up to as the “safest city” in India for women due to its large population of working women. Despite this, I found the fear from my community embodied by most women of the city through their careful decision-making in order to access public life.

Infrastructure Injustice

Indian societies have held patriarchal traditions for generations, creating challenging conditions for women to posess equal rights. However, due to Mumbai’s progressive political leaders in the early 1990s, the city became one of the first places in the country to normalize working women through policy. Despite this, there are still structures in the city that restrict women. For example, in the 1940s, officials in the city made it illegal for women to work and be seen in public at night.

Today, this legacy continues through a lack of safe public infrastructure for women’s needs. Public transportation is one of the primary zones of sexual violence and the government has responded by trying to protect women through the construction of “Ladies’ compartments,” separate sections in trains for women guarded by policemen. However, this segregation often leads to further gender-based violence against those that are deemed undesirable. Respectable women are protected, but often women that don’t meet these expectations (by their manners) are unfairly policed and excluded.

Undesirability

Determined by one’s caste, class, gender, sexuality, religion and their proximity to sex work. This has a direct relationship with how respectable they are considered, and the degree to which their presence is threatened in public.

Respectability

How a woman is “not” acting poorly, or in other words, avoiding undesirability.

Another main way we see women’s rights to public space inhibited is through the limited number of public bathrooms in the city. In the film “Q2P,” Paromita Vohra asks young women in a girl’s school if they use public restrooms. They reply with laughter, admitting that they have never thought to use one. In addition, one woman admits that she feels shame to even think about using a public toilet, and that “one should have control (over themselves).” This absence inflicts violence among women, especially trans women, into silence, fear, and shame for their bodily needs. The lack of quality and quantity of public restrooms is justified by authorities stating that women who spend too much time outside are not seen as decent. The movement of women is controlled.

Patriarchal systems haunt India through this paternalistic and belittling attitude that men and authority figures have towards women; where they take responsibility for protecting a women’s honor over her true safety. To these men, a woman’s respectability is essential in proving her humanness. The position of women in society is seen as highly important and needing to be protected, yet, the responsibility of violence usually falls on them.

Respectability

Women are vigilant in public. Their primary concern when venturing outside is to avoid being the victim of violence. This comes from a real fear of being physically harmed, but far more than this, they are afraid that any such attacks will mar their respectability. Women’s rights to movement, freedom, and pleasure in India today are shaped by how respectable they are considered. Everyday women are expected to act under certain norms publicly and domestically, such as not being outside at night and not participating in romantic or sexual engagements. The closer one’s identity is to being undesirable, and the more unrespectable they act, increases their likelihood of being targeted and enduring violence in public.

The overwhelming patriarchal ideology is that free women pollute society. Controlled women make society respectable. Although Mumbai is seen as a “safer” Indian city, one thing in common for all women here, is their hypervigilance in seeking to minimize risks to safety even as they seek to maximize access to public space.

Women are not only expected to prove their respectability, but also their desirability.

For example, an Indian woman might wear a skirt out with her friends to prove her femininity and easy nature, but then be reprimanded at home in the same outfit for being too rebellious, western, and disrespectful. She then might find ways to change inconspicuously into different outfits as she travels between various social environments. The manner of a girl is taken personally onto the family, risking their honor and reputation. The way one dresses shapes not only their character, but also controls where and how one moves.

She is respected for taking the train to work everyday, but going one too many times on the weekend is frowned upon. If she comes back home late from work, she is meeting her family’s expectations, but if she’s out late because she was with friends at a bar then she’s considered indecent.

Respect is a tool of survival deemed by one’s clothing, where, and when they were “out”. However, one is always at risk regardless of their status because a woman’s very presence in public begins to move across the threshold of respectability.

For Indian women in the subcontinent and the diaspora it is normalized for them to take responsibility for their and their families honor. Women are expected to do so by projecting decency in their lives.

The British were responsible for constructing these binaries and emphasized existing patriarchal traditions that shape the perceptions of women, their marginality, and their access to space today: Private vs. Public, Desirability vs. Undesirability, and Respectable vs. Unrespectable. Although Mumbai is seen as a “safer” Indian city, everyday women are hypervigilant in seeking to make evident their respectability, as a tool of survival.

“Everyday women strategize to minimize risks to safety even as they seek to maximize access to public space. These strategies are informed by their locations within class, caste, and ethnic contexts and they crystallize mainly due to layered experiences. These experiences of fear, anxiety and violation on one hand and of freedom and security on the other, are both individual and collective” .

Responsibility and Shame

Despite the common belief that women are more in danger when they’re in public, the real structural violence tends to happen more at home; when the rights of wives and daughters are taken away. Even when men are assaulted, the attention in the media tends to turn towards women, claiming that violence among men is more importantly, a threat towards the safety of women. This leads them to question the definition of violence. Structural violence stems from the home, where families reprimand women for being out too late, in the name of “care and love”.

This practice of women being seen as vulnerable, needing to be protected, and responsible for their experienced violence, stems from parts of Hindu mythology. In these stories, women hold the responsibility of strength, in relationship to Mother-ing their husband, children, and community. They have often been portrayed as defenders of the nation, and its values, by acting as warriors and care-givers. Women and goddesses are expected to pull men out of their cowardliness, especially in regards to indecent sexual acts.

There are many Hindu myths where women were raped and then punished. Often the society or community at large faces consequences, and the survivor is blamed for the crime. In other instances, the woman is punished, and/or “purified”. She is seen as being defiled by the violence enacted on her.

Even in contemporary feminist movements, we see the survivor reduced to a symbol of bravery, just as they are done in mythological stories. Often the woman gets depicted as “disgraced” and is “… blamed for ‘crossing the Lakshman Rekha’, the symbol of restrictions put on women in the name of ‘protecting them’” (Priyamvada). Rape is almost always the responsibility of the survivor, and men are expected to have sexual liberty.

Respectability inflicts Shame. Undesirability inflicts Borders.

A myth where the deity Lakshmana draws a line around his brother’s wife, Sita, and their home before he ventures out on a journey. She traverses this line for a need and faces consequences by being captured by Ravana, an evil lord.

Borders

In Mumbai, this line of safety is constantly shifting based on binaries such as class, caste, and gender. These binaries govern how women shape movements, decisions, and behaviors. There is fear around crossing these constantly shifting lines of respectability.

Neighborhoods in the city have different codes for decency which depend on the community’s proximity to undesirability. For example, a more conservative Hindu neighborhood with mostly an older generation of residents may consider it inappropriate for a woman to wear a short skirt. Whereas in Bandra West, a predominantly Christian, liberal, and wealthy neighborhood, one commonly sees women in Western clothing. “Accessing public space in ‘the safe city’ means a subtle dance around multiple defined and undefined borders and boundaries, in other words, the city’s ‘Lakshman Rekhas’” (Phadke).

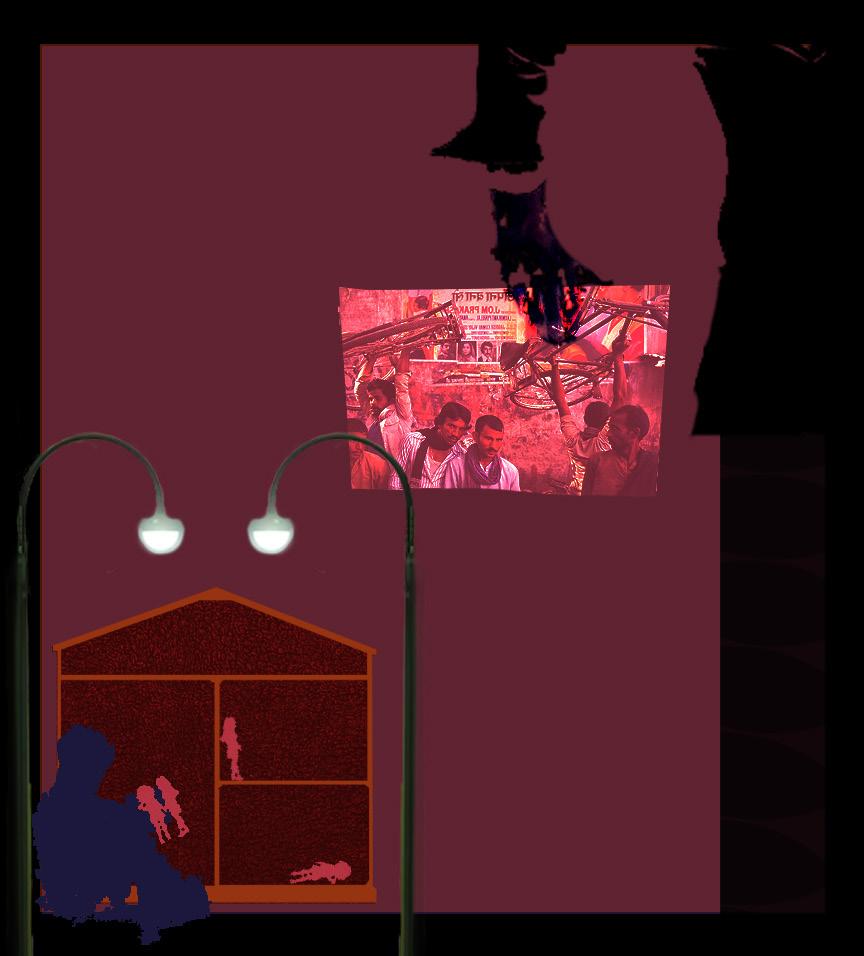

In the following night context, we see a district of the city that is car-centric, with little lighting, and strong physical boundaries. Fear is encouraged in this highly regulated environment.

On the other hand, dense urban environments with opportunities for interaction between communities, different programs, and rest and play encourage people to move with comfort.

In order to reach true liberation, women must be able to navigate their lives without fear of crossing the lines of respectability.

Exploring Mumbai, how has the material, societal, and social construction of the city shaped the way that women’s movements and behaviors are controlled? How can rituals of disobedience, pleasure and love, rerepresent and reshape the city?

“The unconditional claim to public space is only possible once all women and men can walk and loiter without demanding respectability.”1

Pursuit of Power

The pursuit of freedom has often been confused with the pursuit of power. Contemporary femonationalists in the Hindu right-wing similarly use the role of women to exclude others that are deemed antithetical. Here the BJP political party antagonizes Muslims by stressing the role of a respectable Hindu woman who preserves culture and society. Women have joined the party to find agency in their Hindu traditional identities and are encouraged to enact violence towards Muslims, in the name of safeguarding the nation’s sacredness. The Hindu right contradicts democracy and social justice, as it claims “who and what Indian women should be,” and establishes the Muslim minority as alien. The Hindutva believe native Hindus that preserve traditional wisdom are the only legitimate residents. This attempt to uplift the societal position of women subjugates others.

Bengali Muslim women in the early 1900s experienced the Lakshman Rekha through the purdah: a physical curtaining off of a woman’s quarters in the domestic realm. Ultimately, purdah was about upholding respectability for the woman, her husband, and her family. A woman’s survival depended on her behavior and perceptions of her family’s honor. The degree to which women were oppressed directly dictated her husband’s and family’s honor. Respectability and honor for a man and his family lied in the subjugation of the family’s women.

Sultana’s Dream, the first Indian feminist utopian story, was written in the context of the purdah. Rokeya Hossain imagined a world where the gender scripts are reversed; men are shut away in homes and women lead and roam the world. This tale, imagining freedom, instead paints a pursuit of power.

However, other parts of Hindu mythology imagine feminine independence and power through the incorporation of women and/or trans deities such as the goddess Kali, who is the goddess of destruction and change. The comic “Priya’s Shakti” leans into this narrative. In the story, we follow a young woman’s (Priya’s) journey enduring sexual violence and harassment. Hindu deities, including Kali, intervene and support Priya in finding, advocating for, and creating justice for herself and other survivors. Contemporary rape cases in India are referenced throughout the comic, where Priya acts as a symbol for the injustice and activism around sexual assault, over the past 10-20 years in India.

Women constantly seek freedom to their bodies and the public domain. How can rituals of disobedience, pleasure, and love, re-represent and reshape the city?

“If Mumbai is known as a city of freeness, where women can be relatively safe, we should be able to look at it (the city) from the viewpoint of women.”

1

Paromita Vohra

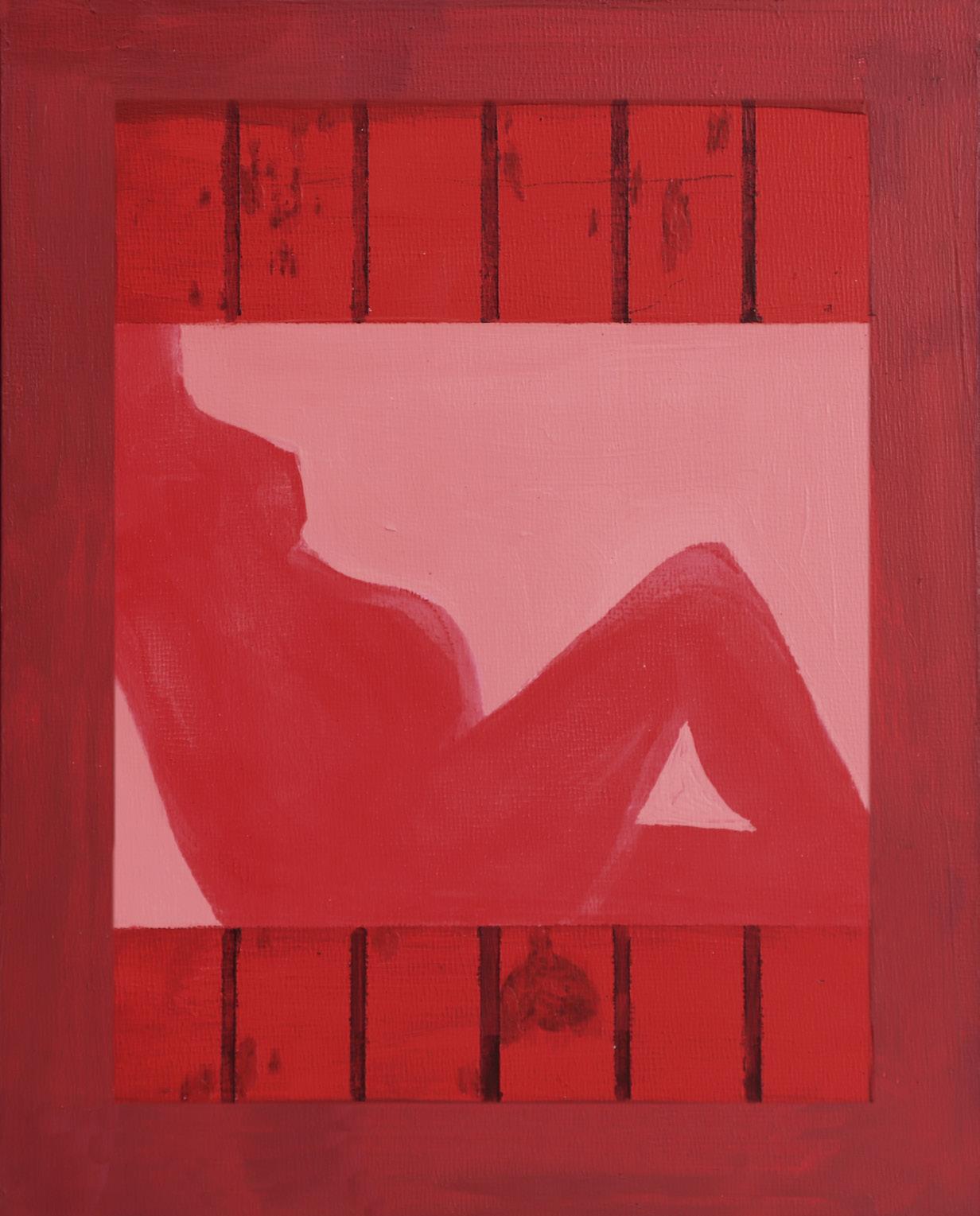

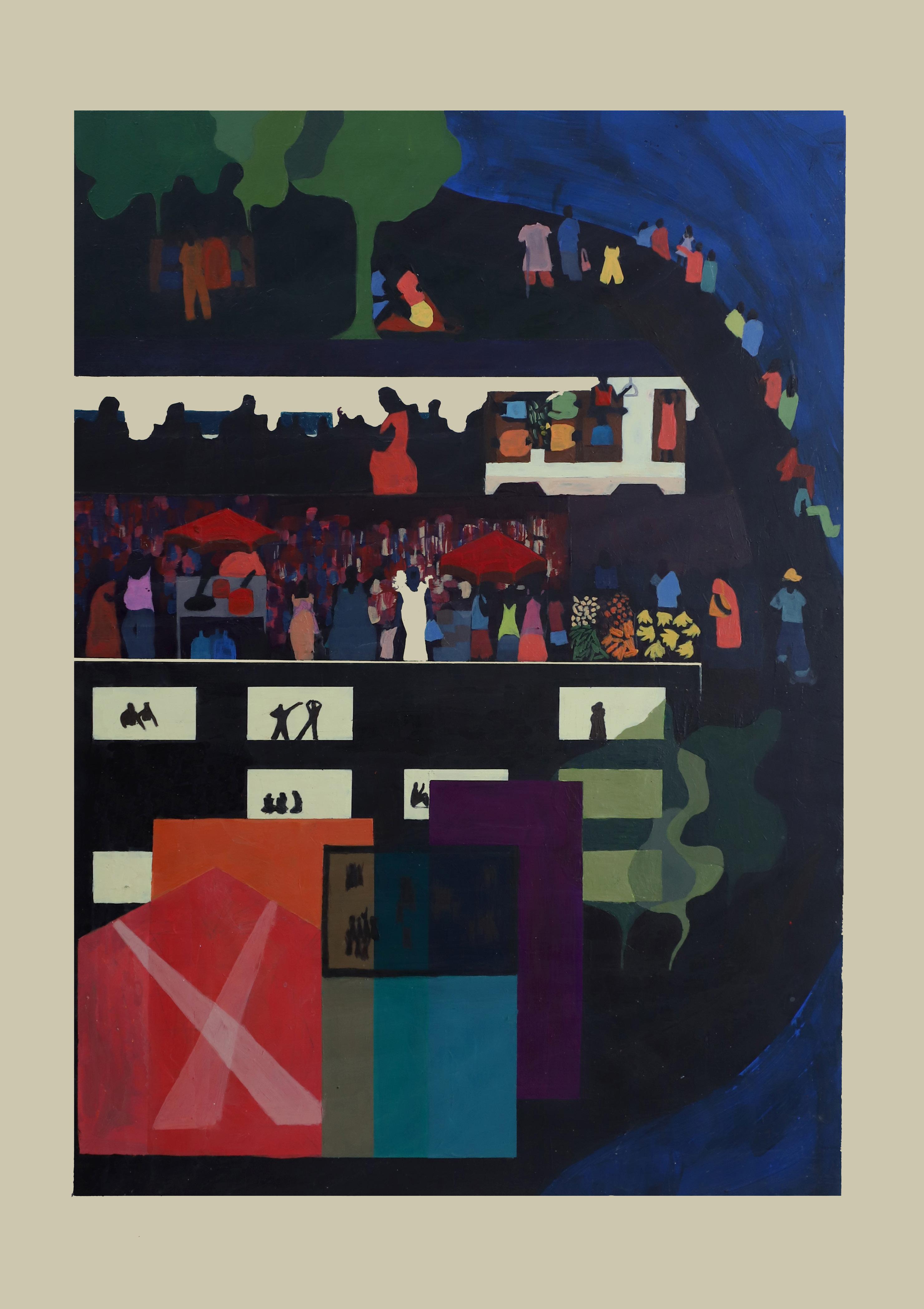

In the following paintings, I borrow the Indian miniature style which merges multiple oblique projection techniques flattening space to communicate a story and landscape. This style was often used to depict royal life in Ancient India. Through these paintings, I ask: What does life look like for those who were never represented through this technique? What are physical and social elements in Mumbai’s landscape that contribute to the story of everyday women seeking freedom and pleasure? How do these women create and sustain space?

Borders of Indian miniature paintings exaggerated the opulence of their royal depictions of life with intricate detailing. In the following paintings, I utilize borders to frame the scene by providing insight to the context and story of each image. They reveal the systems and efforts at play creating the space’s conditions. In other moments, the frames speak to the pursuits and desires that women in the city engage with. I also use them to exaggerate the difference between the performative systems of safety in these spaces, and the reality of conditions for such women.

The Mall

Access to basic infrastructure (transportation, restrooms, etc.) is often privatized and commodified through the means of cars, cabs, and private stores’ restrooms, only allowing for middle-class or walthy women. If one is not willing or able to consume (be inside a store), then one is seen as a hawker, disrupting the decency of society.

Malls are often seen as safe spaces for wealthy women. Many middle class women use these spaces to find refuge from the chaotic city by being in community with one another. However, these glamorized illusions, devoid of public access, exclude most people and dominate much of the city. Malls are policed zones where in order to enter as a woman, one must be ushered through a curtained off section where an officer scans them. The privacy of the curtain claims to protect women from men oversexualizing them when they get scanned. But in reality, the guards isolate her and create a space of discomfort. Outside the mall, people considered undesirable scatter the streets.

Being the Other

The design of both of Mumbai streets and buildings eliminate flexibility in urban space, and by virtue embody exclusion. Neighborhoods, like Bandra West, project liberal ideology, but women still undergo societal pressures that continue to restrict their movement. Most women of the city do not have access to such spaces of wealth and femininity. The facades of the city allure them to a false pleasure. We must imagine liberation as freedom, accessibility, and pleasure for all.

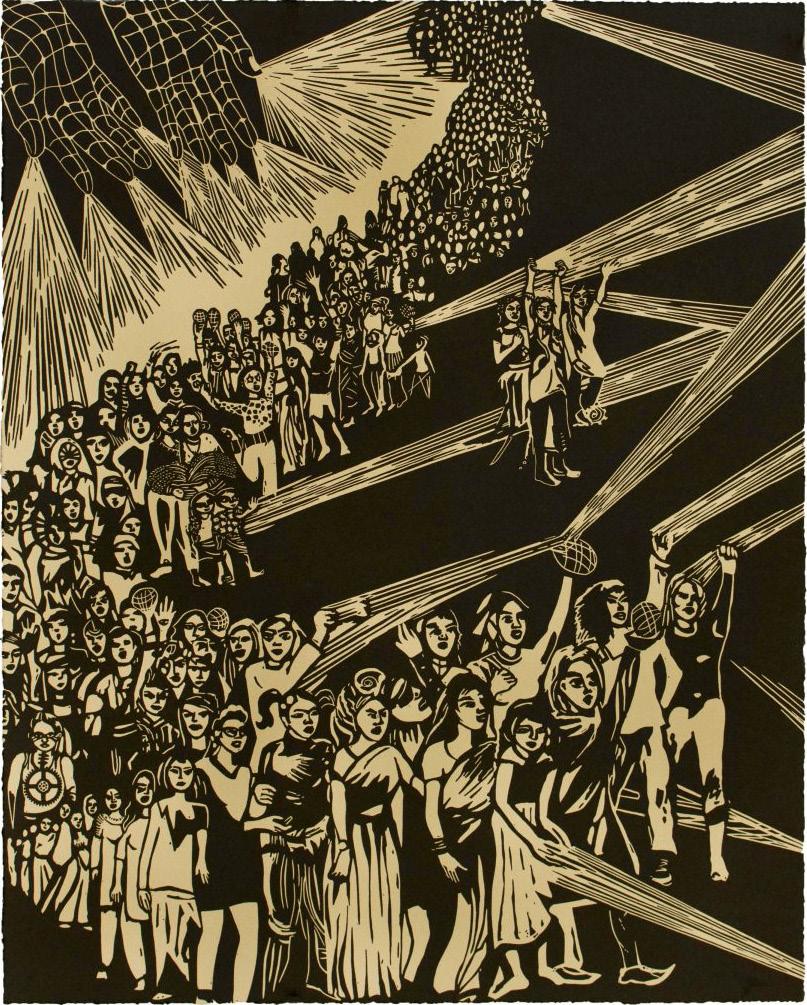

Break the Cage

Feminist collectives in India are often led by university students. Pinjra Tod, translating to “Break the Cage”, is one such movement across the country that demands colleges loosen restrictions for women in dorms. Often these institutions hold strong rules over their female students. For example in the film Q2P, university girls in Mumbai explain they are not allowed to leave their hostel after 8 pm. Young women across the city argue for access to the night, and to destabilize the securitized structures of universities. Here we see the story of these women, avoiding the real dangers of the night, the guard men.

Indecency

The unconditional claim to public space is only possible once all women and men can walk and loiter without demanding respectability.

Loitering mocks the idea that any one group can define a space; it conflicts with the idea of homogeneous spaces and authority. This disobedience resists by no longer operating under the hegemonic systems that constrict and restrain women. Instead, this embodiment paints a new reality, destroying the myths of respectability and silence. Unapologetic pleasure demands equal respect and humanity by leading with courage. Women no longer sustain their silence and are encouraged to take up space; physically, mentally, and socially. This counterwork reimagines the “feminist” Indian woman as one who no longer centers her life and movement around order, status, and honor, but rather as one who sees her humanity and pleasure in life as sacred.

Shilpa Padke in “Why Loiter” states the unconditional claim to public space is only possible once all women and men can walk and loiter without demanding respectability. Loitering mocks the idea that any one group can define a space; it conflicts with the idea of homogeneous spaces and authority . Often, women in poverty are forced to live in a constant state of loitering. Despite such difficult conditions, they

create space for work and life on the streets, disobeying the conventional rules of decency. They cross the threshold of respectability and begin to enter this counter-work.

Chai Tapri

Chai Tapris (informal vendors selling chai and snacks on the side of the streets) invite people of all ages and identities to seek a midday snack and casual conversation. One finds young girls after school paying a few rupees for a bag of chips to gossip.

Professionals around the block walk to share fresh omelet pavs (omelet sandwiches) and to tease one another, breaking away from their stressful work day. These everyday moments abundant across the city defy and encourage everyday people to be informal with one another. The tapri allows people of the city, regardless of their class, to access leisure in public.

Protest for Leisure

“Occupying the night streets” was a series of protests that occurred across India, where women spoke, sang, and danced at night asserting their rights to the city and to leisure. They created and built this imagination by arguing against the rules of private-ness that are enforced after sundown. Their joy pushed men to the borders; demanding uncomfortable questions to be reckoned with.

Pleasure Box

What if we imagine the city as a place where pockets of pleasure zones are designed, built, and occupied by all women and nonwomen of the city? Where we can carefully tend to the fear we and others hold. Instead of surveillance being the primary method

Boardwalk

Marine Drive is a long boardwalk in South Mumbai where people from across the city crowd to find a place to sit along the water’s edge. Separations between groups diffuse and intimate experiences of rest and play occur within and between one another. People reconnect with the sea, often a boundaried commodity in the city.

Day and Night

When speaking to women in and from Mumbai, many revealed a desire to have freedom in their bodies and choice of clothing. They narrated their dreams of meeting friends for a late night hangout with a tank top on and no jacket to cover up; then calling a rickshaw and not having any fear of being judged or assaulted for the amount of skin they show. They dream of being surrounded by big trees, the ocean coast, and community. They imagine talking, laughing, and singing loudly; running without a care, skateboarding down streets, napping soundly, and enjoying the night sky with their friends. They envision being able to “wrap their arms” around the city; that through community and solidarity, Mumbai will make and sustain space for their bodies and their joy.

“How do you push your boundary within yourself? How do you push your boundaries within your family...? How do you take that one step more and then what do you do in your own community to push those boundaries?”1

Nandita Shah

Bibliography

Azad, N. (2015, September 30). Pinjra Tod: Stop caging women behind college hostel bars. Feminism in India. https://feminisminindia.com/2015/09/30/pinjra-tod-stopcaging-women-behind-college-hostel-bars/.

Desai, Madhavi. Gender and the Built Environment in India. New Delhi: Zubaan, 2007.

Devineni, Ram, Vikas K. Menon, and Dan Goldman. Priya’s Shakti. Lieu de publication non identifié: Rattapallax, 2014.

(N.d.). Feminist Freedom Warriors: Nandita Shah. Retrieved June 24, 2023, from http:// feministfreedomwarriors.org/watchvideo.php?firstname=Nandita&lastname=Shah.

Gera, Rohena. Is Love Enough? Sir. PVR Inox Pictures, 2018. 1 hr 39 min.

Ghadially, Rehana. Urban Women in Contemporary India A Reader. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2007.

Magazine, The Site. “Founding the Feminist Utopia.” THE SITE MAGAZINE. THE SITE MAGAZINE, November 10, 2018. https://www.thesitemagazine.com/read/founding-thefeminist-utopia.

Phadke, Shilpa, Sameera Khan, and Shilpa Ranade. Why Loiter?: Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets. Penguin Books, 2011.

Priyamvada, Pooja. “Tracing the Origins of Rape Culture in Mythology.” Feminism in India, October 5, 2017. https://feminisminindia.com/2017/10/06/origins-rape-culturemythology/?amp.

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. Women and Work in Precolonial India: A Reader. SAGE Publications, 2016.

Rokeẏā, Roushan Jahan, Hanna Papanek, and Rokeẏā. Sultana’s Dream and Selections from the Secluded Ones / a Feminist Utopia and Selections from the Secluded Ones. New York: Feminist Press, 1988.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Can There Be a Feminist World?” Public Books, June 17, 2020. https://www.publicbooks.org/can-there-be-a-feminist-world/. The Bridge Project (2020), “Reclaiming Public Spaces “ (9.0), 18 Oct, 2020, URL: https:// www.buzzsprout.com/921337/5945599

Vohra, Paromita, Where is Sandra? Celebrate Bandra Trust, 2006. 18 min

Vohra, Paromita, Q2P. Rai Films, 2006. 55 min.