Front cover features Acorn Days, an original artwork by L. Frank (Tongva, Acjachemen, Raramuri)

Front cover features Acorn Days, an original artwork by L. Frank (Tongva, Acjachemen, Raramuri)

Dr. Henrietta Mann

Virulent diseases, such as smallpox that would all but elimate Indigenous People; The strangers‘ unquenchable greed for the land; Culturally impactful assimilation-oriented education; Forgetting the peoples’ cultural ways to embrace those of the strangers. FinallyMost heart-rending and utterly defying human imagination, this good-hearted man sadly stated: The earth will burn.

The contemporary world now knows that he predicted global warming. He articulated the necessity of watching for changing and extreme weather conditions from the windows and doors of one’s home and to institute appropriate safety measures as necessary. However, he said some individuals would “be so incapacitated by fear they would crouch in the corners of their homes, pulling their blankets over their heads” naively expecting to be safe from the dangerous and sometimes lethal storms/floods raging around them.

Tragically, our ancestral intergenerational knowledge has contemporary relevance in that this land’s first people now live in the time predicted by that good-hearted Cheyenne man. The light-colored strangers found our homelands and claimed our land, justified under the racially prejudiced 1493 Doctrine of Discovery, which also touted Christian conversion. Some Indigenous peoples embraced Christianity, some continue to adhere to their age-old ceremonies, and others practice both ways. Today the people hold on to about 1% of this country’s land base, which has prompted the Land Back Movement. Furthermore, their homelands are at more risk in terms of climate change.

Indigenous peoples were virtually slated for extinction under the principles of Manifest Destiny/Cultural Imperialism. However, their knowledge systems forewarned them of the strangers whose diseases would be as deadly as their firearms. As predicted, immigrants carried some European diseases into this country. Eager to find wealth, they moved west across Indigenous lands infecting untold numbers of Indigenous peoples with diseases such as smallpox and cholera. Some have referred to this as biological germ warfare. Consequently, the recent Covid epidemic is but a continuation of the people’ tragic experience with foreign diseases.

Westward expansion eventually resulted in treaties, some of which mandated the education of Indian children that would integrate them into America’s melting pot. Such schools created generations of Anglicized Indigenous children, whose languages and culture were literally stripped away along with their traditional clothing, and Anglo haircuts. Anglo educators did not understand that one’s hair is indicative of the strength of one’s mind.

The Indian Boarding School curriculum had three broad components: First a rudimentary English education which included learning to speak English. The second was industrial training, and the third was religious instruction. Various religious denominations were tasked with educating Indian children in their reservation and off reservation boarding school systems. Indian children had no choice but to embrace the ways of their oppressor and they discarded their cultural ways to became “good Indians.” However, some who returned home picked up their ways, which was negatively referred to as “returning to the blanket.” The good-hearted Cheyenne man had warned the people to not allow the strangers to educate their children, because those they educated would know nothing.

Entanglement in the strangers’ web of education prevented generations of Indian children from having the privilege of being educated by their tribal teachers. Consequently, they did not learn their strong ways of being. Such tribal educational systems taught that people are more important than material items; that a person must respect all people and all life; that the individual must be honest, gentle, kind, and polite to everyone; and that they must each cooperate with one another and help each other.

Regrettably, historical aggression and assimilationist oriented educational institutions have resulted in some contemporary Indigenous individuals who are not heart-centered and who appear to be blind to the good and beauty in life. Some carry the burden of historical intergenerational trauma that can result in self-destructive and damaging patterns of behavior. Guided by negativity, some fail to see the good that results from love, respect, compassion, and understanding. It is time for all contemporary Indigenous people to be positive role models for all the children of the world and to be the beloved and sacred people our ancestors prayed for seven generations back. It is now our time to honor and embrace our sacredness and to love and pray for the seven generations into tomorrow.

Beverly Bushyhead

Generational trauma profoundly affects Indigenous communities, manifesting in social, emotional, and psychological challenges. The legacy of colonization—marked by stolen land, genocide, the reservation system, the forced removal of children, boarding school legacies, and systemic oppression—have created deep wounds that persist across generations. This trauma often leads to a cycle of pain and struggle, making it difficult for individuals and communities.

We are amid an Indigenous Renaissance; where generational trauma heals through traditional history, medicines, practices, cultural revitalization, and access to culturally relevant mental health resources. Indigenous communities are remembering and using pathways to health through heritage, culture, and pride.

It is my honor to align my personal healing journey with my purpose. I am an enrolled citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (Big Cove Community), the name my nation calls itself is Kituwah Nation. I grew up with my tribe on our original lands in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina. As a restorative practitioner, transformative leader, and strengths-based community builder, I focus on the intersection of cultural trauma response. I share original curricula through cohort designed learning, workshop facilitation, and restorative circles.

There is a purpose that belongs only to us – deep in our core, related to what we have gone through collectively, endured and continue to confront. Our spirit elevates what has happened and makes it a source of strength we carry with us every day.

Covid is a recent collective trauma. Entire communities may be feeling heightened anxiety in response to COVID-19, while complex trauma survivors might experience intensified reactions most pertinent to their own life stories. It warrants our attention and care. Our beautiful tribal nations have experienced the fullest collective traumas possible more than once and over multiple generations.

Researchers suggest traumatic historical events create a collective memory. This collective memory transcends individual memory. The study of epigenetics has researched and documented this. Generational transmission of memory and strength is a way to ensure the survival of future generations, to prepare them to withstand and survive what they might experience. Alongside the challenges of intergenerational trauma, Indigenous peoples carry forward immense strengths rooted in history, culture, and resilience. The knowledge, intelligence, and wisdom passed down through generations serve as vital resources for healing and empowerment. It occurs to me in this moment, in this body, in this heart we may be stronger because of our histories. The collective memory of Indigenous communities is a powerful force, infused with endurance and survival. These are strengths crucial for the survival and flourishing of Indigenous cultures.

We are experts at survival and at focusing our collective memory toward recovery. We are restoring and immersing ourselves and our children in preservation of the language. We are knocking down statues, advocating for restoration of original names in our geographies, and elevating the voices of water protectors and leaders. We are fighting policies that prohibit us from wearing our ceremonial regalia at graduations, and we are building a place for economic shares for our people. The world is turning toward us, as our warnings about colonial values and practices manifest in the growing concerns of climate change. As the signs we named become visible and as our practices make sense; We emerge as survival experts.

We are a transformational people. We are brilliant at adapting. Indigenous peoples will continue to fight for survival under the conditions of settler colonialism. Because colonization has NOT ended. Supremacy must be a hard addiction to give up. But we know it is an illusion. It is my prayer each of us use our influence in the workplace, in our families, in the community, and in our own spirits because these practices are ours in all fullness.

The spirit of our peoples retained for centuries is unshakeable. Unshakeable and focused through every challenge, every loss, every doubt, and fear. That is the core of our hope. It is our purpose. A purpose larger than us.

Our ancestors are cheering and rooting for us and want us to hear them guiding us back to ourselves. Surviving unveils courage, creativity, and compassion, fueling possibilities. Being survival experts equips us with tools to lead ourselves, each other, and all people to the Indigenous liberation, freedom, and wholeness we seek!

Aviâja Egede Lynge

Trigger warning: This text may have content that triggers trauma such as violence, suicide and loss of loved ones. Reach out to someone you can talk to if you need it.

Kaassassuk: the orphan boy

Inuit have a very old story. It's about the orphan boy, Kaassassuk. As a child, Kaassassuk was severely belittled by his own people and was unwanted and they prevented him from growing. He was subjected to severe mental and physical violence. Only an old woman and an old man cared for him. One day the old man told him to visit “Pissaap Inua” (Power of the Force).

Pissaap Inua had the form of a giant wolf, with a human face. It was terrifying and scary.

Kaassassuk went up to Pissaap Inua, who wrapped him around his big tail and threw him on the ground three times. While this was happening, Kaassassuk's toys fell away from him. Kaassassuk gained so much power that he could now catch three polar bears with his bare hands. This is not the whole story. But the point is that by taking courage, he was able to face his fears and thus overcome his trauma. And in this way, he gained his strength. It wasn't Pissaap Inua who gave him the power. It was Kaassassuk himself who went to the scary creature and took the power. Eventually, the story ends with Kaassassuk taking revenge on his own people. The second point of the story is that it ends with him losing his powers because of his misuse and abuse of them.

Today, thousands of years later, we Indigenous Peoples unfortunately live with similar conditions. Lateral violence against our own people is, to me, one of the biggest problems preventing us from rebuilding healthy and strong communities. Our children, our next generation, are witnessing how this behavior of degrading fellow human beings has become a normality.

Oppression of who we are is something we have all experienced throughout history. There are no Indigenous Peoples in the world who do not have that kind of trauma. Oppression is the source of fragmentation and polarization in our collective societies. Through colonization and assimilation, norms were created for to standardize who, what, and how we were worth as a human being. The difference today is that we ourselves, as a trauma reaction, are doing this to our own. We suppress our own. A trauma reaction rooted in unresolved generational grief.

For about 25 years I have tried to find the answer to why we, Indigenous Peoples, whose cultures are based on collectivity, cohesion, respect and closeness to each other, have reached a point where many behave as if we no longer have empathy towards each other. I tried to look for the answer in a lack of mental decolonization. But I was still missing something. For those 25 years, I sought answers in academia, by studying colonialism, and by trying to go through my own mental decolonization. But it wasn't until I entered the world of trauma consciousness, and by going through my own trauma healing process, that a whole new understanding came to me. Mental decolonization can only succeed if we heal our trauma too. And the answer is not outside of us but lies in our own healing.

Symptoms of collective trauma are dehumanization and disconnection. When you are closed in, living in constant survival, you don't feel yourself. And when you don't feel yourself, you can't feel others and thus you can lose empathy towards other people.

Our nervous systems are designed to be understood by the nervous systems of others so that we can sense others. But if the nervous system is in a constant state of survival or shut down, this cannot happen. And in this, societies become polarized and fragmented. In fact, the reverse of our cultural values, where community is one of the most important values. In addition, collective and generational trauma brings shame. And shame prevents healing. And this is what I believe is the key to understanding, and thus begin to eliminate lateral violence: Dehumanization, shame and lateral violence are connected, and therefore trauma healing is necessary for us to heal lateral violence.

Trauma-based shame can express itself in different ways. You can feel inadequate, unwanted, wrong and compare yourself to others. Shame can create fear of being excluded from communities and thus your existence. For some, this can lead to a strong need to have power and control others through social control. This can also mean becoming destructive towards others by attacking others through physical and psychological violence, showing disrespectful anger, degrading others, denying their own behavior and blaming others. Others may withdraw and isolate themselves and develop social anxiety. Some become self-destructive by self-harming or sacrifice themselves so much for others that they forget their own needs. Because shame takes place in relation to other people, the way we react and behave can become collective norms. This can be seen in how we treat others and how we treat ourselves. And perhaps sometimes we don't realize that we are dealing with trauma reactions, even though in reality they are preventing us from restoring strong and healthy Indigenous societies. Lateral violence is just such an obstacle. Just as it prevented the Kaassassuk from growing.

The ability to feel shame is innate and is necessary for the development of empathy and the ability to engage in relationships and communities. Short-term shame is normal and can be regulated. However, the unacceptable actions taken during colonization and in the attempt to assimilate us into their culture have brought with them shame that, albeit often unconsciously, is still passed on to new generations.

Lateral violence causes powerlessness, disrespect, belittling, denial and harassment. Unhealthy survival strategies make it harder to empathize and to be compassionate. We often become focused on what someone is doing wrong and turn on each other. Even though the perpetrator of lateral violence is actually harboring shame, insecurity, self-hatred and not feeling well. What they do to others can have major consequences in terms of physical and mental health, anxiety, traumatic fear and loss of self-esteem and confidence. In this way, the vicious cycle continues and is passed on to new generations.

Take a moment and think about the feeling of being hurt by another person. They have said or done something that really hurts our feelings. How do we react to them? Many people go into self-defense, get angry, and use harsh words against them. That is, by doing the opposite of what you need emotionally. Imagine instead reacting in this way: you calm yourself down and relax your body. Then, you approach the person who has hurt you in a respectful and gentle way and tell them that you are sorry for what was said or done. And if they get angry, in self-defense, you maintain your calm and caring approach. Can you imagine that? And if you can't, what is it that you need to learn?

We need to find the antidote to lateral violence. And it is found within ourselves. It does so in the healing of our trauma, where presence, contact and empathy can be reawakened. Some believe that lateral violence is what fragments us and that we must first find community again. I do not agree with this. It is the trauma that fragments us and creates lateral violence, which in turn causes us to constantly remain in a survival mode of self-defense and insecurity. We therefore need to find safety, learn to feel ourselves, learn to listen to each other and regain trust in each other.

We have fought for so long and we are still fighting. And we are strong. But I believe that we must dare to ask ourselves the question “are we too strong”. Has the struggle for survival given us the belief that we are only strong when we don't feel our feelings? When, without facing our children's feelings, do we simply tell them to be strong? Because that's what our parents did? Humans are so brilliantly designed that we shut down when something is too violent. But we're not meant to stay in that state.

We do not win any battle while we perpetrate lateral violence against each other. It paralyzes us, leaves us in shame and shames our own people. Should we continue to let our new generations carry our pain? In this connection, I have been allowed to quote my 22-year-old daughter:

“I am proud to be here. We survived colonialism. It's one of the greatest things I've seen. But we forget to be proud that we survived. We could be here now, without our culture and despite colonialism, we seek the path to who we are. I have almost been killed and I have almost killed myself. We must make sure that our new generation lives, not just survives. We must learn how to live first.”

We have an innate ability to heal. We are made to be whole people, with balance in body, mind and soul. Our cultural customs and rituals already contain tools for healing and regulating our nervous systems than most people probably think about on a daily basis. It's already in our cultures where we regulate together. Just feel the effect of drumming and singing when we hear it, how we can feel our body, soul and calmness. They simply tried to take away our lifeblood: our cultures, through which we had developed a regulatory system that allowed us to live together and with nature for thousands of years. Our cultural practices were not just entertainment or a show. They all had a purpose that gave us security, strength and unity. Think of the time before colonial trauma set in, the most important thing was that we were safe - together.

Healing happens in relationships, so we need to do it together. And it must be done safely. Everything we do must be safe for ourselves and for others. Trauma makes you lose the ability to feel safe with other people. Safety is therefore the key to healing. So, can we start there? What makes us feel safe? How can we restore safety and trust together? And by healing together, I don't mean small, closed groups where we exclude others because they are not 100% like us. This is another fragmentation and will not bring us together.

How can we learn to be vulnerable together? What can we do to understand our own and other triggers? How can we learn to confront each other but still value each other? How can we get in touch with what we already have built into us: closeness, love for our children, for nature, for our cultures, and not least, the ability to listen to each other and meet each other based on where we are and who we are?

We don't need to look outside ourselves because the essence of trauma healing is to rediscover who we are. Just think of our ancestors. Our shamans did not dictate how people should be, but they listened, met people where they are so they could rediscover balance. I will therefore end where I started: The story of Kaassassuk. The story happened long before colonization. Even back then, people had the wisdom to heal and the morals that you should never put others down and that you should never abuse your power. And we still have that wisdom, passed down through many generations. They didn't take everything from us, but it is now our own task to reunite ourselves with ourselves and with each other.

Tara Trudell

But I know how I feel about making beads. How it regulates and revives my spirit in a purposeful and prayerful way. I’ve been doing this for over 10 years. It started as a project when I went back to school after a very painful divorce. I was left to raise my four children as a single mother in a small northern New Mexico town. I needed to remember who I was to find my will to survive. The beads brought me back, one by one as I started with my divorce decree and income support paperwork. Then my poetry came to life in beads. Now I make beads out of laws, testimonies, statistics, healing, dying, research, and data. I cannot imagine my life any other way as I celebrate this gift from the Ancestors. The return to our reliance on beads as our way of protection, healing, and sharing our stories has given me a purpose and healing that I was never able to reach over the many years of seeking repair for harm done to me, my family, my people, and earth. Creating prayer beads from my poetry or remembrance beads to honor loved ones who have transitioned, taught me to pause and understand how I honored this spirit, words, and how I am to walk in this world. It comes with a huge responsibility to a galaxy of Ancestors who give me guidance with each story I am to retell with beads.

Whether it is Warrior Pamela Foster's powerful testimony typed and rolled word for word; Or Seventh Generation Fund’s Be a Good Ancestor, adorned with beads made from the pages of the United Nations Declaration on The Rights of Indigenous Peoples booklet and the Thriving Women’s Red Paper featuring the story of Abalone Woman. The process revealed how it wanted to be told through me. I am attempting to take words and stories off the pages and make it tangible as another way of sharing, awareness and action. Creating regalia for storytelling and protection in the sharing of beads has been very uplifting for me on my path because I feel the beads chose me to tell the stories and I must really lean into what those entail. And in those moments, I feel a deep healing that makes me stronger. I’ve been making beads from paper in this manner for over a decade now, never imagining I’d be doing what I am doing today, yet this is why I am still here to share and be in Sister Solidarity with many who have sat at my table and made beads with me.

Arriving at this point in my journey, on this red road of our precious Mother Earth aligned here with warrior women around the world to re/tell our stories, one bead at a time, I am heartened and do not take lightly my role in honoring Ancestors in all I do. It is in this prayerful act that it is the most decolonial action I can achieve in my reality of survival in a world of continual war, capitalism, misogyny, patriarchy, and torturous oppression.

As a survival of generational trauma and earth relatedness, the beads, our oldest form of communication, prayer, protection, healing, and adornment has given me back a power to remember a time before harm came to us. I am deeply grateful to hear this warrior woman speak and remind me to remember a time before harm and remember/re-start from there. In doing this I also discovered the history of beads and how important and vital they are to our wellbeing as Indigenous Peoples globally to reclaim our way to value, pray, protect, and strengthen without the influence of the colonizer currency in this process and what this can look like within our communities again.

Beads are known to predate human history to the time of the Neanderthals and have globally been used as a tool for prayer and spiritual practices. The word bead itself comes from the Anglo-Saxon word bidden which means to pray, and the Middle English word bede which means prayer. Early civilizations made beads out of natural materials found in their geographical location, making beads not only a symbol of religious beliefs or political history, but also a blueprint of social circumstances, culture and place.

"Westerners tend to think of beads as adornment. In fact, we confine ourselves for the most part to draping them around our necks. Yet, through the centuries, beads have functioned as more than jewelry. They are kaleidoscopic, combined and recombined in an astonishingly wide range of materials; they express social circumstances, political history, and religious beliefs."

— Lois Sherr Dubin, The History of Beads, From 100,000 B.C. to the Present

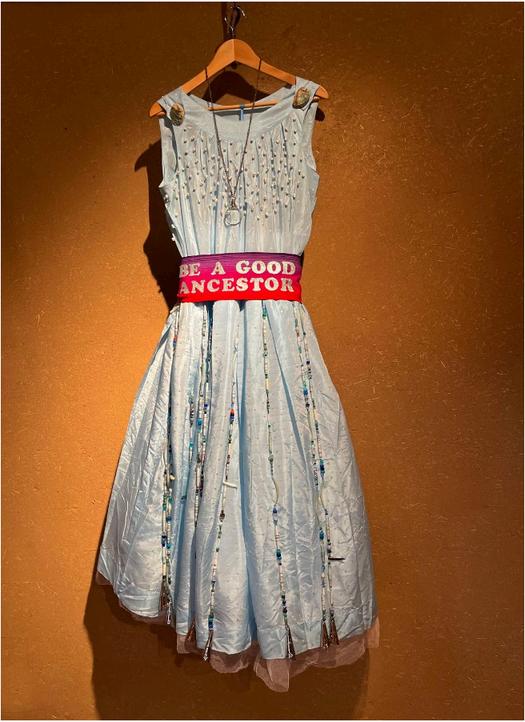

Be A Good Ancestor Dancer

1950’s vintage dress, hand rolled paper beads, wire, jingles, vintage beads; abalone, dentalium, turquoise, crystal, and glass beads, woven belt, iron-on letters, antique magnifying glass

Created in ceremony from the pages of the first Thriving Women publication by the Seventh Generation Fund for Indigenous Peoples. These stories include the story of the Abalone Woman and uplifts the many voices of the good work done by many Indigenous Peoples in the communities across the lands.

The beads are strung together with vintage beads and shells, jingle, and wire. Each strand is attached into the folds of the skirt of the dress and glows in the dark to replicate the northern light energy.

The top of the dress is adorned with tiny beads made from the pages of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Each bead becomes a tangible way to learn our rights as Indigenous Peoples in a manner that can be a spiritual reconnection to our own ancestral ways in determining our own value, medicine, and protection.

Each bead adorning “Be a Good Ancestor Dancer” is a deep and heartfelt tribute to the incredible work and people that make up this powerful and strengthening organization that has taught and empowered me to be on the path of what it means to be a good ancestor in this lifetime and in this realm.

Gifted turquoise beads, grandmother picked ghost berries, vintage shell, crystal beads strung on twine and fastened with deer hide.

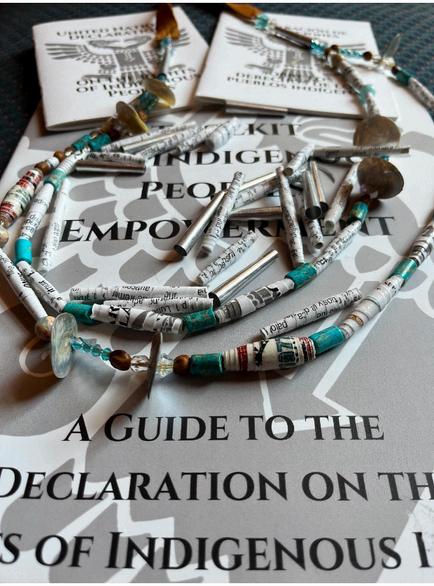

Handmade beads from the Toolkit for Indigenous Peoples Empowerment for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples created by Seventh Generation Fund to accompany the pamphlets.

Naomi Lanoi

One particularly contentious issue involves the OBC (Otterlo Business Corporation) and members of the royal family from the United Arab Emirates, who have engaged in a leasing agreement for Maasai land in Loliondo without the community's consent, effectively leading to large-scale land appropriation. The participation of UAE royals in hunting safaris in Loliondo has heightened tensions with the local Maasai population, who assert their rightful ownership of the land. Allegations of land grabbing and human rights abuses have been directed at these hunting companies operating in the area.

This series of events marked the beginning of Maanda Ngoitiko's activism, a Maasai woman leader from Loliondo, driven by a passion for girls’ education, community empowerment and Maasai land rights. However, her journey has been fraught with challenges, including arrests, harassment, and trauma. Despite these obstacles, Maanda remains dedicated to her cause, advocating for the rights of her people and the healing of her community.

This narrative delves into Maanda's experiences in activism, the obstacles and trauma she has confronted, strategies for supporting healing, gaps and recommendation in grantmaking in fostering resilience among defenders.

Maanda Ngoitiko’s Journey as a defender and activist.

Since then, Maanda embarked on her journey as an activist and advocate, emerging as a voice for her community. Soon, other women from her community joined her cause, amplifying their previously silenced voices and becoming a formidable presence within the Maasai community in Northern Tanzania. Elders now seek her counsel, recognizing her as a spokesperson for their community. Initially, she faced criticism and was labeled as someone who breaks up marriages because of her efforts to rescue girls from early marriages and enroll them in school. This period was incredibly challenging, as accusations came from within her own community. However, the tide has since turned, and now many empowered girls are working and serving as role models. This has created opportunities for numerous other girls in her community. As Maanda posit, the struggle is no longer as intense. Nowadays, Maasai parents willingly sell their land and cattle to ensure their daughters receive an education. It's ironic that despite this progress, there's now a shortage of job opportunities. However, it's a source of pride that they have fourteen lawyers from her community working to benefit their own people.

For the past two decades, Maanda has faced numerous challenges and retaliations due to her involvement and impact in advocating for Maasai land rights in northern Tanzania. An illustrative incident occurred in 2017 when Maanda was apprehended while visiting her daughter at school. She was held in custody in Arusha for two days before being transferred to Loliondo under the cover of darkness, where she spent an additional six days behind bars. The journey, lasting six hours in the back of a speeding double-cabin land rover, escorted by two armed policemen, remains one of the most harrowing experiences of her life. In this disturbing turn of events, she was falsely accused of being a Kenyan and illegally residing in the country and instigating violence against the government. This tactic, exploiting the close ties between the Maasai communities of Tanzania and Kenya separated by a border, has become a convenient method for the government to silence Maasai activists. Despite the unjust charges, Maanda and other women from her village who had joined the land rights movement protest found solace in singing together while in jail until they were eventually cleared of all accusations.

Following that incident, numerous similar arrests have ensued, distinguished by heightened levels of torture and a complete disregard for human dignity. Tragically, Maanda has suffered the loss of her beloved brother who greatly influenced and supported her work but unfortunately fell victim to unidentified attackers and mourned the deaths of many other community members. Moreover, she has been subjected to arrest while pregnant and even while caring for an infant as young as three months old. The ongoing trauma has deeply affected her children, who live in constant fear of police intrusion whenever their mother is at home. They are relentlessly pursued by suspicious vehicles and persistently implore her to seek refuge elsewhere, fearing for her safety within their own community.

Violation and mental health.

The root of Maanda's distress lies in witnessing the deep fear and vulnerability experienced by her children and spouse. As time has passed, her body has suffered from torture, leaving behind bruises and persistent headaches. The displacement of her community to make room for UAE Arab hunting endeavors has inflicted profound distress upon her. She has become a recognizable figure to both law enforcement and the judicial system, her name inseparable from activism and advocacy. Out of love and concern for Maanda's safety, her husband, also a highly respected and influential strategist and advisor in the Maasai land rights movement, continues to shoulder her pain, supporting her to navigate these challenges and occasionally organizing emergency relocations, aiming to shield her from further arrest and harassments. Meanwhile, their children also frequently change residences, moving from one house to another. They departed from their family home in Arusha and now rent a house in town. They continue to relocate whenever they sense that their whereabouts are known to others. In this challenging situation, Maanda's eldest daughter has stepped into a maternal role within the family. She has shouldered the majority of the burdens and responsibilities, essentially becoming a caregiver and source of support for her siblings and parents.

Maanda’s healing approach involves singing and praying alongside women elders and friends. These gatherings provide an opportunity for women to sit together, share stories, and find joy in laughter. Additionally, Maanda finds solace in walking the cows for hours, viewing it as a form of both healing and medicine. The women elders also conduct healing ceremonies using medicinal plants specifically for wounded souls, which she credits with keeping her alive. This personal journey and spiritual connection with the women in her community serves to recalibrate her spirit and replenish her energy.

Witnessing fellow women in the movement struggle with mental breakdowns due to neglecting the healing process deeply affects Maanda. It pains her to see them grappling with trauma and mental distress, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing healing as an integral part of the activism journey.

According to Maanda, mental health remains a neglected concern among human, land, and environmental defenders. These individuals are revered within their communities as voices of advocacy. Community members place immense hope and expectation on them to address pressing social, political and economic issues. However, there is a striking absence of support systems to check on their well-being and even a lesser space for intervention. They are often expected to carry on regardless, without anyone ensuring their own mental health needs are met.

Many of these defenders have unintentionally put their families on the back burner while wholeheartedly serving their communities. Regrettably, there's often a lack of guidance available to emphasize the necessity of rest or to advocate for stepping back and waiting for clarity before proceeding. This is crucial because, due to the mental challenges they face, they may not always be in the right state of mind to engage in protests or other forms of activism.

Maanda stresses the significance of establishing a succession plan for the next generation of human rights defenders. This involves mentoring them from a young age to cultivate leadership skills. Additionally, it's essential to empower community members to assume leadership roles. By encouraging active participation from all members—regardless of age or gender—in advocating against land grabbing or environmental crises, the burden is lifted from a select few individuals. Moreover, this approach prevents these defenders from being singled out and targeted by the government.

Dr. Michael Yellowbird

I’d like to begin with a short grounding meditation practice. Find a comfortable place to sit, put your feet flat on the floor, and rest your hands on your lap. Make sure you’re sitting up straight. Lower your chin slightly towards your chest and close your eyes (if it feels safe to do so). Take in four to five deep and slow in-breaths and and out-breaths, consciously relaxing your whole body and mind with each cycle of breaths.

Now, gently bring your awareness to your breath and feel the coolness in your nostrils as you inhale and the warmth as you exhale. Stay with this for several breaths – maintaining your sense of calm and relaxation. When you’re ready, notice how your belly and shoulders rise with the in-breath and fall with the out-breath. Now, on each in-breath, silently say to yourself, “calm breath.” On the out-breath say “beautiful breath.” Keep this up for several breaths while giving yourself permission to enjoy the feeling of calm and beauty entering your body and mind. When you are ready you can express gratitude for the present moment and gently open your eyes and smile to yourself.

My contemplative life is inspired and guided by the sacred beliefs and teachings of my Indigenous Arikara ancestors. I began practicing meditation in 1975 and teaching mindfulness meditation approaches to Indigenous communities, schools, organizations, and groups, in the early 1990s. I experienced many dark, traumatic events growing up that stayed with me for many years. Which is due not only to the psychological nature of trauma, but also to a gene called ADRA2B that’s linked to more intense memories, emotions and negativity. Meditation and neurodecolonization practices (using traditional contemplative approaches) have changed my brain’s structure and function. It’s enabled me to better regulate my emotions, ease my reactivity to negative events and people, increase my sense of calm and optimism under difficult situations, reduce my stress, and improve my awareness, focus, and mental health.

My contemplative life is inspired and guided by the sacred beliefs and teachings of my Indigenous Arikara ancestors. Nearly every morning when I arise, I engage in the contemplative practices of my great-grandfather, Plenty Fox, an Arikara holy man. My father expressed how fortunate he was to be raised by grandpa Plenty Fox, who shared the special stories, prayers, and sacredness of silence that my father passed on to me. Upon waking, before his feet touched the earth, Grandpa Plenty Fox would begin his day by lighting the sage he picked from a special place that was watched over by the spirit guardians of the plants. Closing his eyes, he would rhythmically shake his sacred gourd in the early morning light, while singing a prayer song to thank his dreams for speaking to him. Following this he would go outside, stand in silent meditation for a period of time, and sing a song that thanked the sun for life, for light, and the blessings bestowed upon all the humans and creatures of the earth. All the while, he bid farewell to the stars that were gently fading in the presence of the rising sun.

When I finish, I sit silently meditating for an hour or so, paying close attention to my body, mind, thoughts, breath, and emotions. The smell of burned sage returns me to a state of awareness of what I’m presently feeling. At moments, I will smile and find that I am relieved of my suffering. Other times, I will re-experience my emotions and difficult memories and have to stop to wipe my tears, blow my nose, and gather my thoughts and feelings. But I do not regard my tears as a sign of weakness, distraction, emotional dysregulation, or trauma. I have learned that sensitivity is a blessing and is essential to entering and understanding sacred space. Tears and deep emotions can generate compassion, clear the mind and spirit, and enable one to see and experience reality in different ways.

On some mornings, I begin my meditation practices by burning sweetgrass as an offering to my ancestors who are an important part of my contemplative lineage. My grandfather Crow Ghost was a well-known contemplative who spent time meditating among the spirits of our deceased. His gift was reminding our people that we are in this world for a short time, and we should always use it wisely, and live a life of humility, generosity, sacrifice, and gratitude. My grandfather Bear’s Teeth (kuuNUxaanu’) was a well-known prophet who was gifted, from the spirits, many kinds of medicines that he used to heal animals and people. He was a rainmaker. During a drought, he could call in the rains (nakutsUhihkAxaahú).

Grandfather Yellow Bird was a spiritual leader who collected the sage and sweetgrass for important ceremonies. He would sing the sacred songs to the plants and their guardians asking them to watch over the people and rituals. My grandfathers have long since passed, but remain with me as guides, warriors, and spiritual revolutionaries who, like the Bodhisattva’s of Zen, made vows to always help ease the suffering of the people:

“Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to save them. Desires are inexhaustible; I vow to put an end to them. The Dharmas are boundless; I vow to master them.

The Buddha Way is unattainable; I vow to attain it.”

(Zen Mountain Monastery)

Sweetgrass calls in the good spirits. As it burns, I ask them to be with me on my journey in this life and the other lives that I may have to live. In my meditations, I make space and offer my gratitude to the sun, winds, and fading stars just as Grandpa Plenty Fox once did. I began my meditations sitting in deep awareness noticing the remnants of the harshness of colonization, oppression, and the streams of lingering trauma passing through my brain and body. However, after many years of practice, I am no longer whisked away by the past or present deeds of colonization. I’ve only become stronger, more aware, and compassionate to that which is the human condition that suffers in its attempts to control, manipulate, and subjugate.

Tragic, disturbing words and memories no longer cause me to cringe, withdraw, or flee into another world of denial and safety. Neither do aggressive people. In my meditations, I remember that memories and behaviors have consequences and so do words. Grandpa Plenty Fox said the chatter that goes on in the mind are just words and thoughts. Illusions. The real words and clear thinking only come when we are in ceremony sacrificing and sustaining ourselves in deep prayer and meditation. The first words are spoken by the spirits, not the people. On some days my movement is the focus of my meditation. At those times, I pay close attention to the power and presence of all the life all around me as I run mindfully over the dirt roads, hills, and valleys on my reservation, or on the sidewalks, streets, or the parks in the cities where I have lived. On the running days, I run silently singing an Arikara runner’s prayer song that calls to the winds and speaks gently to our mother Earth:

Mother I call to you as I run upon your lap You cradle me. You give me life. Winds be with me. Winds carry me. Winds protect me. Winds bless us all.

These lines are from a song that came to me in a dream one night at a sun dance ceremony on my reservation in 1992, when I had taken my usual short summer hiatus from my PhD studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. I have previously shared them in a short story called, “Minding the Indigenous Mind: Winds at Sun Dance.”

As I move along, I am reminded that running and movement are holy acts, and I am sustained by that knowledge. The oral histories and running traditions of Indigenous Peoples are filled with references to the importance of and obligation to running as a sacred act and responsibility (Nabokov, 1981). “Gods and animals ran long before Indian men and women ever did. Thereafter the gods told people to do it, and the animals showed them how” (p. 23). Running played an important part in sacred rituals, ceremonies, games, and competitions. Nabokov writes, “Indian runners relied on powers beyond their own abilities to help them run for war, hunting, and sport. To dodge, maintain long distances, spurt for shorter ones, to breathe correctly and transcend oneself called for a relationship with strengths and skills which were the property of animals, trails, stars, and elements” (p.70). According to a western science paradigm, running increases my endocannabinoids and BrainDerived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) levels, which improve my mood, reduce my stress and anxiety, enhance my memory, protect my brain function, blunt my pain, prevent depression, and help to generate new brain cells and protect existing ones (Ratey, 2008). The circle of life is unending.

Deborah Sanchez

The people who have created this system and who perpetuate this system, they are out of balance. They have made us out of balance. They have come into our minds and they have come into our hearts and they’ve programmed us. Because we live in this society and it has put us out of balance.

- John Trudell, 1980

The role of colonization in (un)wellness

If you can, imagine having your whole world disrupted, everything you believe in is used as a justification to kill you, to steal your possessions, to enslave you, and to oppress you. Everything about you is despised, the way you look, the clothes you wear, the language you speak, and the way you pray. As a last resort the invaders will spare you, if they can first remake you in their image, to talk like them, dress like them, and believe what they believe. It is a worldwide phenomenon that Indigenous people have the worst health outcomes. After surviving colonization and more than five hundred years of its residual impact, is it any wonder? Many scholars have written about these health disparities and these inequalities are well documented. One researcher, refers to colonialization as a “driver of Indigenous health” and describes racism as alternating between “extermination and exploitation,” but primarily “focused on extermination.” The histories of Indigenous peoples and their colonization experiences have included genocide; slavery; stolen children; sterilization; laws and policies banning ceremony, assembly, languages, and traditional dress; the destruction of the environment; massacres of people and our animal relatives; forced labor; land theft and displacement; physical and biological warfare; genital mutilation of the dead; and the attempts to incentivize assimilation. Jack Forbes in Columbus and other Cannibals, identifies this behavior as the wétiko (cannibal) psychosis. Beset with violence, he calls it “the greatest epidemic sickness known to man.” Being infected by the wétiko results in the exploitation without end, of people, land, and water. Relentless, this psychosis can be spread to anyone. Indigenous people are not immune. Indigenous people exposed to contemporary, westernized lifestyles are rapidly acquiring present-day diseases, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and disorders linked to the misuse of alcohol and drugs.

Spirituality, language and wellness

The commonality among the various Indigenous definitions of wellness is a sense of balance and wholeness, not as a simple lack of disease. Balance is a key concept that has been referred to when explaining what wellness is. This is the condition John Trudell spoke of in his Thanksgiving Address in 1980. Spirituality has been missing from wellness studies involving Indigenous peoples. Many Indigenous people, as distinct as we are from one another, have a concept of balance as one of iconic tenets for good living. It is often said that Indigenous people would like to live according to our original instructions. I am reminded of the term Red Road. This term is broadly understood across many diverse tribal nations. Balance, wholeness, integrity: these are just some of the terms associated with wellness in First Nations/Native American communities. Because the concept of wellness is multifaceted and complex it is difficult to define. On the other hand, wellness is something that is simple, natural, and when understood, needs no words to define it.

Although there is tremendous diversity among the indigenous peoples of North America, most have the concept of balance as integral to well-being. (Weaver, 2002). Many studies have found a robust connection between language and wellness. I began hearing about this at a language conference in 2016. Intrigued by this information, it sparked my curiosity into the relationship between wellness and language. The benefits of revitalizing heritage languages can be inferred through our community stories. Indigenous scholars have given insight into the various definitions of what wellness means to Indigenous peoples, establishing how language reclamation and revitalization may impact the wellness of Indigenous people. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that spirituality and culture affect how language impacts the wellness of Indigenous people. Spirituality and culture are embedded in our languages. Language gives voice to our worldview. It is the embodiment of who we are as a people. Indigenous scholars bring a deeper understanding of wellness from an Indigenous perspective and the crucial role of language. One researcher, Rorick (2023) stated that dreaming is a source of wellness and observed her research approach involved “the recognition of dreams as a wellspring of wisdom and insight,” drawing the innate connections between “First Nations concepts of well-being and Indigenous language reclamation.” She affirms that speaking the “sacred heritage language” reestablishes relationships with land, water, which strengthened her own “ancestral responsibilities.”

In 2007, researchers in Canada specifically examined the link between language knowledge and suicides by reviewing data collected in 1998. This report was based on the research conducted in Indigenous communities in British Columbia, Canada. The data revealed strong ties between language knowledge and suicide rates, finding that heritage language use had predictive power over other cultural continuity factors, such as self-government, land claims, education, health care, cultural facilities, and police and fire services. They indicated that those bands with higher language knowledge had significantly lower suicide rates, or none at all. Specifically, many of those communities with more than 50% language knowledge had no suicides. They found that language knowledge was the primary factor in reduced suicide rates.

In the late 1990’s, I attended a Native conference in Oklahoma while tagging along with my mom. This was about three years after the tragic bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma. One hundred-sixty-eight people were killed and nineteen of the victims were children from the building’s daycare center.

While in Oklahoma we visited the memorial. Large, empty chairs sat solemnly with names etched into each one. Nineteen smaller chairs represented the children. The memorial’s time arch depicted 9:01 a.m. representing the last moments of innocence. At the other end of the memorial the time arch read 9:02 a.m., representing the destruction that followed the bombing.

When I look at the history of this country and the other countries that have been devastated by colonization, I see the Oklahoma bombing as a metaphor for the innocence we were robbed of. Mass devastation after living thousands of years on our sacred bioregions, land we say was given to us by Creator. We live in the aftermath of the chaos and destruction caused by colonization. It is clear there is a remarkable connection between Indigenous wellness and the use of our heritage languages. It’s time for the reclamation and revitalization of our heritage languages, our medicine, our ways of being, and our worldview. The ancestors are calling us. Future generations depend on us.

Mike Duncan

This is what I’ve been taught, and this is what I believe. To each of my children, I want you to know, my prayer is that you teach this to your children and that they teach this to their children. I want them to know that this is my belief and understand that it comes from my love of being your father.

Every piece of art I create begins with the land—a sacred, living entity that is both a source of materials and a spiritual foundation. The forests, rivers, and earth are not simply resources to be harvested; they are part of a larger network that I am honored to not only engage with but to live in right relationship with. When I walk into the forest, I am aware that I am entering into a relationship with the land. This relationship is guided by the teachings passed to me through my relatives and ancestors, who remind me that everything has spirit, story, and life. In Lakota we acknowledge this connection thus acknowledging ourselves as part of their wellbeing and their interconnected to ours. Harvesting these materials is not an act of belligerent consumption but of friendship. It’s taking the time to understand and to know the nature of your relationship, asking permission, giving respect and offering gratitude – Making Relatives.

The unique landscapes where I’ve lived and called home— from the Lakota lands that raised me, to the Yurok, Wiyot, Hupa, and Karuk lands that helped me grow have each influenced my work in profound ways. Redwoods, madrone, and salmon of the pacific coast to the cottonwoods, birch, and buffalo of the plains and beyond. These materials carry the energy and wisdom of their respective lands, shaping not only the physical form and material of the art but also the worldview behind it. Considering that these relationships have existed for a millennium, it is no surprise that each one of our cultures reflects the land’s undeniable influence on the artist’s perspective, process and result.

During the pandemic in 2021, this refuge took on a profound new meaning. The isolation and uncertainty that enveloped the world mirrored a kind of internal stillness, allowing me to focus more deeply on my spiritual practices. The Lakota Sundance ceremony and lifeway, the loadbearing beam of my cultural and spiritual life, was postponed for the first time since my community brought it back again. This absence was felt deeply, but this absence opened a new space for reflection and growth. In a time of both global and personal upheaval, I began work on an envisioned courtroom table for the Redding Rancheria—a project that was innately about healing. The process of building this table was unlike any other, in that it channeled just the slightest bit of the mental and spiritual focus held at Sundance into doing things in my home and workshop. For four days I steamed off every morning in my lodge, prepared meals for my family, and then went to my woodshop, ready integrate that energy into my work, a table meant to bring compassion and healing back where it was needed most.

As I worked here, I spoke to the native walnut to the land, stringing together prayers for the people who would gather around this table. I asked for the teachings of the tree to be passed on to them, for the strength of the earth to support their decisions, and for the healing energy of the land to permeate their interactions. I wanted people to not feel alone but at home and feel like a whole human being regardless of the circumstances that brought them there. The significance of this table extended far beyond its function. It was designed to embody the values of the Redding Rancheria’s worldview, the table’s round shape represented equality and inclusivity. The three sections of the table symbolized the accountability of all involved—the judge, the families, and the community—emphasizing a collective commitment and responsibility to healing. The use of California black walnut connected the table directly to the land and people, imbuing it with the power of the materials and their role in healing. I carved the symbols of the Yana, Pit River, and Maidu peoples into the table, honoring the collective identities that make up the tribe. A resin river running across the table resembled the Sacramento River, tying the piece to the natural landscape where their people have lived for generations.

Throughout these four days, I discovered how seamlessly I could work, even while fasting. Initially cautious—aware of the potential dangers of using power tools while fasting—I found that the discipline I had cultivated in this sacred space prior, the way I worked in general in the shop made the process effortless. The workshop had become an extension of the ceremonial space, a place where creation and healing were intertwined. As I worked, as I often do, I sang Lakota songs, filling the space with prayers and resonating with the energy of the wood. When the table was finally complete, I stood back and felt an overwhelming sense of peace and rightness. This was not just a functional piece of furniture; it was a vessel of healing, born out of a time of global turmoil, yet carrying within it the quiet strength of the land and people known for a millennium to the people it was meant to serve. The process reaffirmed my understanding of the workshop as a sacred space—a place where creation and healing can happen simultaneously.

One experience I’ll share that made me aware of this and deeply impacted me was when a childhood friend visited my workshop. We hadn’t spoken since we were teenagers, but she reached out through social media, wanting to reconnect and build something together. She had recently ended a relationship and was navigating the emotions that come with such a life change. She decided to build a TV stand, something she had loved but something that felt emotionally tied to her past relationship. We spent the weekend in the shop, surrounded by the foggy beauty. The smell of fresh-cut wood filled the air, and the rhythmic sound of wood mauls echoed through the space, grounding us in the task at hand. The warm safety of the workshop became a space for her to process and reclaim her power. When the TV stand was complete, she began to cry—an emotional release that symbolized more than just the completion of a project. It was a reclamation of her self-worth and a new step forward in her life. This experience was an eye-opening realization that the sacred space I had cultivated for my own healing could also serve as a powerful tool for others. The workshop, the energy of the land and the living power of the materials, opened a direct path to healing for my friend. This understanding shaped how I approached my work from there on out honing my creative processes into healing process.

Grounded by the spirits of the lands I’ve lived on and the healing safety of my workshop, my creative process unfolds over and over each time anew. Each step—whether it’s cleaning the space for the next project or actively working on one—is deeply intentional. This connection ensures that the art remains true to its origins, has spiritual integrity and resonance with the power and stories of the lands that have shaped it

As I work with the materials, I am not just shaping them—I am engaging in a conversation with them. I listen to the wood, the clay, the fabric, allowing them to guide the process. This is not a one-sided act of creation; it is a partnership, a collaboration between the artist and the material. The process is fluid and adaptable, allowing for the unexpected, for the moments of insight and inspiration that come from deep engagement with the work. I often dream of the design as I’m working on it, using that dream space to think about the next step forward. Every movement and aspect of this process is a weaving of intention. The feel of the wood grain under my fingers, the sound of the chisel cutting cleanly through the wood, and the scent of the earth when working with clay as it spins between my hands contribute to the immersive experience. This intention is to create a piece that carries the energy of healing, transformation, and connection. The art that emerges from this process is more than an object—it is a living vessel of health.

extends far beyond what I could ever imagine. This is the mark I seek to leave in this world—healing, resilience, and connection that will continue to grow and thrive long after I am gone. I invite you, the reader, to reflect on how you engage with the spaces and objects in your own life and to see the potential for healing and connection in every corner of your world.

The process of creation—from the land, to the workshop, to the hands of those who receive the art—is a continuous journey of healing. It is a process that honors the past, nurtures the present, and allows for possibility. Through my art, I am not only healing myself but offering a pathway for others to find their own healing. This is the essence of my work: to create art that is alive, that breathes, and that carries with it the power of healing and the strength of people and culture that can never be erased.

Linda Black Elk & Luke Black Elk

Over the years since meeting Joe, we have made a lot of herbal infused bone broths, soups, stews, and herbal blends for our friends, relatives, and allies on the front lines of battles raging everywhere from the East to the West Coast, and from the North to the South. Of course, we have learned to treat cuts, scrapes, bruises, and injuries caused by pepper spray and other “less-than-lethal weapons”; but many of the issues we treat, such as stress, anxiety, grief, and trauma - are almost always treatable with the right foods - medicinal foods.

If any of this seems overwhelming, remember that it’s ok to take tiny steps towards the ultimate goal of health and wellness. If you’re sitting on the front lines, you probably don’t have time to make bone broth. It’s ok to ask for help and to ask allies to make good food and bring it to you. It’s ok to eat a handful of trail mix and a cup of coffee, as long as you recognize that it’s not sustainable in the long term. Ask for help in the form of good food. Your allies should be sustaining you so that you can sustain the planet.

Turkey bones (1 whole carcass)

6 quarts of water

3 tsp good salt

3 tsp ground beebalm

2 tsp ground sage

3 tsp onion powder

3 tsp garlic powder

3 tsp epazote

3 tsp rosemary

3 tsp paprika

3 tsp dried squash blossoms

1/2 tsp ground osha root

6 tsp dried nettle

3 tsp ground turmeric

1 1/2 tsp ground black pepper

6 tsp mushroom powder

3 TB maple sugar

2 TB maple vinegar

We love and appreciate you. Here’s one of our favorite Medicine Soup recipes. We hope it will nourish and sustain you through tough times and easy times.

Crock pot directions:

Add water, bones, herbs, powders, and vinegar to a large crockpot and cook on low for 12 hours. Strain well, allow it to cool, and freeze if desired. You can also pressure-can this bone broth or make it into soup immediately by adding a protein of your choice, carrots, onions, celery, and your favorite foraged ingredients.

Fireside directions: Add bones, and water to a fire safe stock pot on medium high heat. Add all herbs, powders, and vinegar, then cook over a low burning fire for about eight hours. Keep the broth at a low simmer by keeping the pot near the heat source, but not directly over it. After it’s reduced by a third, strain the broth and allow it to cool. You can now freeze or pressure-can the broth, or you can add soup ingredients such as the protein of your choice, carrots, onions, celery, and your favorite foraged ingredients to make a delicious camp “medicine soup.”

Tia Oros Peters

We know the cruel and oppressive systems created to tear apart and devour Indigenous identities, families, and communities are alive and well and set up for mass destruction. We have seen how these show up in different ways and sometimes target and take root in our own lives. Many of us are survivors of all kinds of terrible things we didn’t deserve and that we are still healing from and trying to understand, let alone talk about. The different kind of injuries we have endured and continue to experience can lead to deep spirit wounds that if not remedied, will stay open and fester.

It’s devastating to think of how this shows up in our families because our peoples have been injured, violated, removed, displaced, and dispossessed multi-generationally as part of the colonial process. It’s sad knowing how lateral internalized violence has accelerated in our communities causing more damage. It’s harder yet to recognize how some of us struggle daily for years, and many don’t make it because of pain that runs so deep all we can feel is anger and fear and all we think we know is harm, confusion, and shame. It can be crushing. And those that don’t heal from the harm often live hurtful lives – to themselves and to others - because hurt people hurt others. This shows up as selfishness, jealousy, and an insatiable greed to violate and destroy to re-create a familiar anguish and disjointedness, rather than a healed, balanced self, family, and world.

Perhaps some are more vulnerable to these shifts and show it by aligning with turmoil and perpetuating hurt against people and lives they don’t even know for reasons we may never fully understand. Whatever the profile or form, it’s a psychosis of the spirit in wounded individuals deeply out of balance. Without positive outlets, their desperate hunger to fill emptiness in their own lives leads them to lash out with twisted behaviors committing harm as a form of nourishment when deep healing is what they really need. I hope they find the healing path.

I’ve learned firsthand how that negative energy can shapeshift into many forms and how violence and deceit can be perpetrated by those we once believed in and trusted. I have had perpetrators slander my character, identity, and reputation. They were caught spinning lies, weaponizing misinformation, and fabricating their own brand of disinformation. A tumbleweed meant to do serious damage.

I am thankful to be alive. For deep and unspoken reasons, a lot of us don’t make it out of our childhood or teenage years. Like many, my heart has been broken and torn apart countless times. It has also healed and scarred over, leaving a memory mark and portal for better understanding about myself and the world. Grateful to have connected with relatives who embrace me and nurture my knowledge and love of my people, culture, language, and homeland, at the same time this story is not uniquely mine alone. It has been a struggle for over 500 years. A lot of Native adoptees of my era, or any generation, are on journeys home. While a different lived experience from those who grew up in their families and communities, my truth has been as a forcibly removed Indigenous girl who was determined to, and found, her way back home as a survivor of a colonial system that intentionally fractures hearts, bodies, and spirits just like it dismembers cultures, lands, and waters.

Understanding is a wonderful thing. It can provide courage and help us find compassion for ourselves and others. Although I will never fully understand why anyone would want to target someone on their path back home there are those out there that do. I know there must be an incentive, like money, or attention, or some kind of payback, or they don’t like a stand taken to protect water, or plant gardens, or against man-camps. Whatever the profile or form, it’s a psychosis of the spirit in those deeply out of balance. I learned a long time ago that there is a spiritual dimension to these kinds of things so no matter what the motivation the perpetrators will have to live with the consequences of their actions. There is no timeline in the unseen world.

Over these decades one critical learning has been realizing how many ways my Ancestors have protected me and that they will continue to do so. I pray about this often and try to live into these teachings by staying on a good path and in a good way. I know that how we grow up is out of our control as children and how we live into adulthood and walk on the skin of Mother Earth shows who we are.

A self of SGF comp oples.

y g scholarly essays, transcribed speeches, poetry and more solution oriented narratives.

Co-Edited by Mima Salas (Diné, Chicana, Gabrieliño) and Deborah Sanchez (Chumash, O’odham, Raramuri)

Compiled by Tia Oros Peters (Shiwi)

Design & Layout by Eli Bargas (Ohlone)

Beverly Bushyhead (Kituwah Cherokee) is a restorative practitioner, transformative leader, and strengths-based community builder focused on the intersection of cultural, generational, and complex trauma response.

Luke (Cheyenne River Lakota) and Linda Black Elk (Jeju Korean and Mongolian) are food sovereignty activists and teachers of traditional plant use, gardening, food preservation, and foraging. They spend their time collecting and preparing traditional foods and medicines for Indigenous Peoples and communities in North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and beyond.

Mike Duncan (Maidu, Wailaki, Wintun,Shoshone) is an enrolled member of Round Valley Indian Tribes. In 2012 Mike Duncan founded Native Dads Network and is currently the CEO. Mike is also certified as CADC II substance abuse counselor. In this time Mike has facilitated the “Fatherhood/Motherhood is Sacred” curriculum with great success and has helped create a network of Fatherhood/Motherhood groups in Northern California.

L. Frank (Tongva/Acjachemem/Rarámuri) is the nom d'arte of L. Frank Manriquez, a two-spirited artist, writer, tribal scholar, native canoe maker/revivalist, and Indigenous language activist.

Naomi Lanoi (Maasai) serves as the Coordinator for Global Indigenous Peoples Grantmaking at Global Greengrants Fund (GGF) She champions the Indigenization of Philanthropy, advocating for inclusive grantmaking practices that empower Indigenous Peoples globally in their rights, self-determination, and environmental efforts.

Aviâja Egede Lynge (Inuk) from Greenland. She comes from several generations who have fought for more equality for indigenous people. She holds a degree in Social Anthropology from The Edinburgh University and is trained in human rights advocacy at Columbia University.

Henrietta Mann (Cheyenne) is a master Cheyenne language teacher in her nation’s tribal language program. She has taught in higher education for several decades and filled the Katz Endowed Chair in Native American Studies at Montana State University, Bozeman. President Joe Biden awarded her a National Humanities Medal in 2023. She now serves as a board member of the Seventh Generation Fund.

Tia Oros Peters (Shiwi) has been involved in Indigenous Peoples’ rights and community empowerment, leadership development, philanthropic innovation, advocacy, and justice strategies for nearly four decades, and serves as the CEO for Seventh Generation Fund for Indigenous Peoples.

Stephan Oak (Lakota) is an artist, builder, and organizer whose work spans many mediums, woodworking, clothing, interior design, and ceramics. He is the founder of High Rez Designs and the fiscally sponsored project, High Rez Impact, both rooted in Indigenous values of sovereignty, sustainability, and intergenerational knowledge. .

Tara Trudell (Santee/Raramuri) offers her personal experience of being a grandmother, granddaughter, daughter, mother, sister, and one day a future ancestor as an opening to bear witness to others who are struggling with their own intergenerational abuse and trauma. Tara shares her own healing journey for others to relate and joins her in the navigation of changing this painful and harmful narrative.

Deborah Sanchez (Chumash, O’odham, Raramuri)

Is the founder of the Chumash Cultural Collective and is a language keeper, song maker, song keeper, regalia maker, traditional dancer, and culture bearer. She is a faculty member at CSU Long Beach and is currently serving as the Vice President of the Seventh Generation Fund.

Michael Yellow Bird, PhD,(Arikara) is a former Dean and Professor, Faculty of Social Work, University of Manitoba. He is a certified, internationally trained and recognized mindfulness meditation teacher, professional, and scholar.