Final Report

I. The Executive Summary

Project title: Building a multi-institutional effort to understand regional connectivity towards effective management of marine resources: linking fish, essential habitats and ecosystems.

Date: 03-31-2018

Project Number: R-101-2-14.

Investigators and affiliation:

Adrian Jordaan, Assistant Professor

Andy J. Danylchuk, Associate Professor

Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 160 Holdsworth Way, Amherst, Massachusetts, 01003

Dates Covered: 12- 31-2014 until 12-31-2016, with extensions to 03-31-2018

A. Objectives

BIRNM was established by Presidential proclamation in 1961, expanded in 2001, and is now one of few fully marine protected areas in the NPS System. Our overall objective was to quantify spatial movements and interactions amongst 5 trophic levels of fish, and make recommendations for management of different life-histories and movement patterns. Our goals specific to this project are to: acoustically tag 25 (divided relatively evenly between each of 5 species) fish each year (50 total) across 5 trophic levels; document spatial movements and habitat connectivity; leverage additional support to tag a greater number of individuals so as to quantify relationships amongst species at different trophic levels.

The use of passive acoustic telemetry is the most efficient method to monitor the longterm movements of fishes and has been used extensively to study fish movement patterns by the PI’s in St. John, USVI and multiple other projects. By 2013, 20 acoustic receivers were deployed to study the spatial ecology of marine turtles. In 2013, Cooperating scientists Gregory Skomal and Bryan DeAngelis will deploy 20-30 more receivers within the BIRNM boundaries. The NPS and NOAA deployed and maintain ~60 receivers in 2014. In total, the BIRNM receiver array comprised 100+ receivers by 2014. Currently, the array comprises 111 receivers, with 28 of those nested in a fine-scale positioning system to examine movements with location data instead of presence data at a receiver location.

Over the course of our research, we have tagged 114 fish around Buck Island Reef National Monument (Table 1), including prior to Sea Grant funding (Table 2). With support from Sea Grant in 2015 a multipurpose trip was taken to St Croix, USVI. During that trip from May 1 to June 5, 24 tags were implanted in a number of shark species, yellowtail and mutton snapper and other species (Table 1). A VEMCO Positioning System (VPS) was installed to allow the capability of tracking fish with greater accuracy, thus improving understanding of fine scale habitat use. The VPS has subsequently been moved to a new location, thus providing another windows with finer resolution. Furthermore, tracking tagged individual fish for multiple years will provide the opportunity to understand habitat selection, movements related to life history events and site fidelity with inter-annual variation in movement patterns. We have built up a large dataset of detections, and collaborators who have tagged other species, and with the support of National Park Service (NPS) through UVI EPSCOR have been working to provide logistical support for partner meetings and workshops to develop data products that provide guidance to NPS.

We demonstrated connectivity between BIRNM and Lang Bank with 1 yellowtail snapper and 6 Horse eye jacks. One yellowtail snapper (tag 19672) spent approximately 26 days outside of BIRNM (from 2/23/16 to 3/19/16), visiting 5 different Lang Bank receivers, managed by both NPS (Lang 01 and Lang 04) and collaborators at UVI (502, 550, and 551). The fish was originally caught and released near West Beach off Buck Island on 6/3/2015 and spent the first ~8 months in the immediate area. The initial timing of the movement to Lang Bank at the end of February coincided with a full moon phase; however, the extent of the stay remains unclear. In total, 224 detections from 6 of the 7 individuals (range: 3 – 91) were recorded on receivers outside of Monument boundaries over the duration of the study. Peak detections outside the MPA occurred March through June 2016 (45.5% of total detections) and began to peak again in March and April 2017 (32.6% of total detections).

B. Advancement of the Field: A 200 to 500 word summary of the interpretation of what the project findings mean to the discipline. New discoveries or methods should be included.

Acoustic telemetry is a relatively nascent field, especially using large arrays in the Caribbean. Understanding aspects of movement when paths are non-directed, in contrast to directed movements such as coastal migrations, are relatively rare. We have been advancing combinations of analyses investigating determination of home range and core use areas, and the first published work (See Becker et al. 2016) was a methods paper addressing typical issues encountered in telemetry data. These include the importance of detection histories and analytical choices on the ability detect ecological patterns. In follow-up work, we demonstrate how current residency metrics are insufficient for describing true residency and thus demonstrating protected area effectiveness.

C. Problems encountered (if any):

Funding was received a year later than expected and the Culebra acoustic array was removed from the water in 2015 as project funding had expired. At the time, 28 bonefish (Albula vulpes) and smaller numbers of permit (Trachinotus falcatus) and great barracuda (Syphraena barracuda) had been acoustically tagged as part of previously funded project. Due to the removal of the majority of the Culebra array when funding was terminated in 2015, no additional fish were tagged in that system. Initial analyses of the 40 acoustic receiver array by graduate student Sarah Becker demonstrated that comparisons of that species were impaired by different array designs and low densities of barracuda inhabiting the Culebra site. Thus, no site comparisons were completed or included in the report.

D. List PI’s supported:

PI Jordaan charged Sea Grant for 0.18 Summer Months ($1564.57 total salary and fringe). No other funds were provided or matched by project PIs, although all contributed time to the greater project effort and supervision of graduate students

E. List students supported:

Ashleigh Novak, Grace Casselberry and Sarah Becker provided 2 months of matched salary per year, which contributed to the writing of thesis and manuscripts, and for field work.

Ashleigh Novak <ajnovak@umass.edu> and Grace Casselberry <gcasselberry@umass.edu>

$3900.00 wages and $814.00 fringe. TOTAL $4,714.00 x 2 x 2= $18,856

Sarah Becker <sarah.becker3@gmail.com>

$4324.00 wages and $913.00 fringe. TOTAL $5,237.00 x 2= $10,474

F. List thesis and dissertations from students supported by the project.

Becker, S.L. 2016. Spatial ecology of great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda) around Buck Island Reef National Monument, St. Croix, U.S.V.I. MS. Intercampus Marine Science Program. 135 p. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/396/

Novak, A.J. Forthcoming in May 2018. “Movers and stayers” Movement ecology of yellowtail snapper Ocyurus chrysurus and horse-eye jack Caranx latus around Buck Island Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands. MS. Intercampus Marine Science Program.

G. -List presentations, technical reports and special awards.

Becker, S. J.T. Finn, A.J. Danylchuk and A. Jordaan 2014. Movement patterns and site fidelity of great barracuda (Syphraena barracuda) around two Caribbean islands. American Fisheries Society Annual Meeting. Quebec, Canada. (Poster)

Novak, A.J., S.E. Becker, A. Danylchuk, and A. Jordaan. 2016. Fine-scale movement and habitat use of yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus) within a marine protected area in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Intercampus Marine Science Symposium. University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth Massachusetts. (Poster)

Becker, S.L. Jack T. Finn, A. Danylchuk, and A. Jordaan*. 2015. Abundance and Home Range of Great Barracuda Sphyraena barracuda Inhabiting Coastal Waters in the Northern Caribbean. American Fisheries Society Annual Meeting. Portland, OR. (Oral)

Becker*, S.L. Jack T. Finn, A. Danylchuk, and A. Jordaan. 2015. Abundance and home range of great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda) inhabiting coastal waters in the Northern Caribbean. Ecological Society of America Annual Meeting. Baltimore, MD. (Oral)

Novak*, A.J., S.E. Becker, J. Finn, C. Pollock, Z. Hillis-Starr, and A. Jordaan. 2016. Broad-scale movements of three species of reef fish within a marine protected area in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute Conference. Grand Cayman, Cayman Islands. (Oral)

Novak*, A.J., S.E. Becker, J. Finn, C. Pollock, Z. Hillis-Starr, and A. Jordaan. 2017. Fine and broad-scale movement ecology of yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus) within a marine protected area in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Intercampus Marine Science Symposium. University of Massachusetts, Boston Massachusetts. (Oral)

H. -List references for, books, chapters, and peer reviewed publications, in press, and submittals. Sea Grant must be acknowledged and include project number.

Becker, S.L., J.T. Finn, A.J. Danylchuk, C.J. Pollock, Z. Hillis-Starr, I. Lundgren and A. Jordaan. 2016. Influence of detection history and analytic tools on quantifying spatial ecology of a predatory fish in a marine protected area. Marine Ecology Progress Series 562:147-161.

Becker, S.L., J.T. Finn, A.J. Novak, A.J. Danylchuk, C.J. Pollock, Z. Hillis-Starr, I. Lundgren and A. Jordaan. In Prep. Multiple movement patterns, temporal variability in spatial use, and

site fidelity for individual territories of great barracuda Sphyraena barracuda in Buck Island Reef National Monument, St. Croix, U.S.V.I.

Novak, A.J., Becker, S.L. Finn, J.T. Pollock, C. Hillis-Starr, Z. and A. Jordaan. In Prep. Defining residency and using network analysis to explore the broad-scale movement ecology of horse eye jack Caranx latus within a Caribbean marine protected area.

I. Indicate sources of matching funds:

Matching support was provided by graduate student support through the Intercampus Marine Sciences Graduate Program.

J. New extramural funds in addition to match:

Co-PIs Skomal and DeAngelis deploy 20 additional receivers within the BIRNM boundaries. The NPS and NOAA deployed and maintained 60 receivers in 2014. The BIRNM receiver array comprised 120 receivers in 2014-15 with a fine-scale array embedded within the array. We have continued to receive base funding for tagging activities and array maintenance by the National Park Service. Support from Sea Grant in tag purchases and from array partners has provided rational for the NPS to continue array maintenance and additional tags. Other partners include Mark Monaco and Matt Kendall (NOAA Biogeography Branch), Ron Hill and Jennifer Doerr (NOAA Fishery Ecology Branch), Kristen Hart (U.S. Geological Survey), Michael Feeley and David Bryan (South Florida/Caribbean I&M Network), Richard Nemeth (University of the Virgin Islands). Each of these project partners has contributed funds for tag and receiver purchases, leveraging considerable multiagency and organizational assets.

The National Park Service has also contributed funds for annual workshops that convene the PIs towards project development and support. The University of Massachusetts has also supported the project with tag and receiver purchases.

K. In addition to the students indicated above provide a breakdown of time and effort attributed to PI’s, Co-PI’s and associates. This includes man/hour dedicated to project and accumulative amounts paid by SG/Match during the entire grant. Also include time and amounts paid for any partial report period up to the time of closing all project.

PI Jordaan received 2 weeks of support per year for tagging and logistical support. PI Jordaan also led the supervision of field efforts and coordinated with project partners, supervised graduate students, helped lead collaborator meetings and edited manuscripts and theses.

L. Research Impacts/Accomplishments: Response to “4R’s”(see progress report guidelines above) from last progress report.

Our project tagged and monitored movements of a suite of fish species in Buck Island Reef National Monument and found significant species differences in space use and connectivity to adjacent management areas resulting in interactions amongst species that appear to partition habitat-use. Fisheries managers realize that ecosystem-based management is a necessity for conservation of marine fisheries resources and consequently healthy ecosystems and habitats. Still, the value and use of habitats by many species remains understudied or unknown, in particular how species move amongst different habitats to complete their entire life history. This project will contribute to a multi-species study over a large spatial and temporal scale that explores links among species and habitats. The research will leverage considerable support by using an expanding collaboration between academic, territorial, and federal researchers developing a network of acoustic tracking stations that cover PR and USVI waters. The goal of this collaboration is to enhance understanding of ecosystem dynamics by employing acoustic

tagging technology, in conjunction with general fisheries techniques. Instead of focusing efforts on a single species, this project seeks to deploy acoustic tags on a variety of species that include sharks (apex predators), barracuda (mesopredators), reef fish (includes both low trophic level consumers and herbivorous species), and turtles.

II. Final Report Narrative

The body of the final report (narrative) completes the final report. We suggest that the narative includes:

Results and Findings

Objectives accomplished

(See Executive Summary example)

Discussion of project impacts and products

(See Executive Summary example)

Recommendations

Bibliography

FINAL REPORT

A brief statement of Problem Fisheries managers realize that ecosystem-based management is a necessity for conservation of marine fisheries resources and consequently healthy ecosystems and habitats. Still, the value and use of habitats by many species remains understudied or unknown, in particular how species move amongst different habitats to complete their entire life history. This project will contribute to a multi-species study over a large spatial and temporal scale that explores links among species and habitats. The research will leverage considerable support by using an expanding collaboration between academic, territorial, and federal researchers developing a network of acoustic tracking stations that cover PR and USVI waters. The goal of this collaboration is to enhance understanding of ecosystem dynamics by employing acoustic tagging technology, in conjunction with general fisheries techniques. Instead of focusing efforts on a single species, this project seeks to deploy acoustic tags on a variety of species that include sharks (apex predators), barracuda (mesopredators), reef fish (includes both low trophic level consumers and herbivorous species), and turtles. We will utilize two existing platforms for the work: an extensive array of receivers around Culebra, Puerto Rico, maintained by Co-PI Danylchuk (UMass) and another surrounding Buck Island Reef National Monument (BIRNM) on St Croix, USVI, maintained by the National Park Service (NPS). Both arrays will be large and capable of documenting individual movements for many species. However, the strength of the proposed work is a novel application to attempt to understand how each of these components, from apex predators to forage species, interact with one another.

Our overall objective is to quantify spatial movements and interactions amongst 5 trophic levels of fish, and make recommendations for management of different life-histories and movement patterns. Our goals specific to this project are to: acoustically tag 25 (divided relatively evenly between each of 5 species) fish each year (50 total) across 5 trophic levels; document spatial movements and habitat connectivity; leverage additional support to tag a greater number of individuals so as to quantify relationships amongst species at different trophic levels.

Methods

Because many tags used in this study have a battery life of at least a year and there is a need to depict seasonal variation, tagging effort was shifted to BIRNM starting in 2015. From now on all tagging will be completed in BIRNM. There was a second tagging trip executed in late January 2016 and another in August 2016, with an additional 23 tags implanted in a variety of species. The final tagging trip occurred in January 2017, where an additional 11 tags were deployed, again on a number of different species.

Sharks, barracuda and a suite of reef fish including jacks (Carangidae) and small snappers (Lutjanidae) and parrotfish (Scarus iseri) were targeted for tagging in St Croix. Sharks were be caught on bottom or floating longline or rod and reel using appropriate methods. Barracuda were captured by trolling with heavy-action recreational fishing gear (14 kg [30 lb] test fishing line) and artificial lures. Reef fish were captured by appropriate methods in consultation and cooperation with the National Park Service. All fish were caught inside BIRMN by trolling with typical recreational fishing gear that uses artificial lures and by jigging on a full moon event. Upon capture, fish were visually assessed to ensure they were in the best condition possible (i.e. no physical trauma present). VEMCO V16, V13-1L, and V9 tags (largest to smallest) were be implanted surgically in fish of sufficient size to support the tag by trained staff.

All transmitter specifications, identification numbers, and acoustic telemetry systems was be maintained by the National Park Service. Data were be uploaded from acoustic receivers during routine receiver checks conducted by the NPS, primarily on a biannual basis. The current array around BIRNM is made up of 111 passive acoustic receivers (model VR2W; 69 kHz; VEMCO, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada) installed throughout shallow water habitat as part of a large collaborative acoustic network. Of those 111 receivers, 25 are utilized for a relatively new technology called VEMCO Positioning System (VPS) with collocated sync tags (VEMCO, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada) deployed in the VPS array to ensure time synchronization between the receivers. The VPS was installed in May-June 2015. The addition of this tightly spaced grid of receivers will allow for fine-scale movements of multiple species to be obtained. This system triangulates the animal’s position with a potential accuracy between 2 – 6 m. If a transmission is detected by three or more receivers the VPS takes the differences of arrival times at receiver pairs and calculates an intermediate position. The final position is calculated by averaging all of the intermediate positions and weighing them by the quality or the position with the least sensitivity to error will have the stronger influence on the final calculated position. The most recent download of the full array and VPS was in November 2017, with current download frequency occurring biannually. Currently, we are analyzing VPS data for an approximate year period, from time of initial installation (May-June 2015) to the download that occurred in May 2016. All receivers need to be downloaded on a regular basis to obtain the detection data and for cleaning and scheduled maintenance (i.e., firmware upgrades) and this is currently underway. UMass is supporting the effort with planning support.

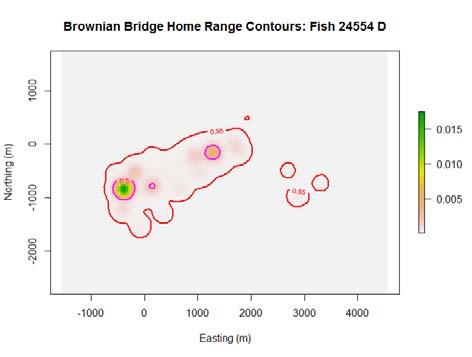

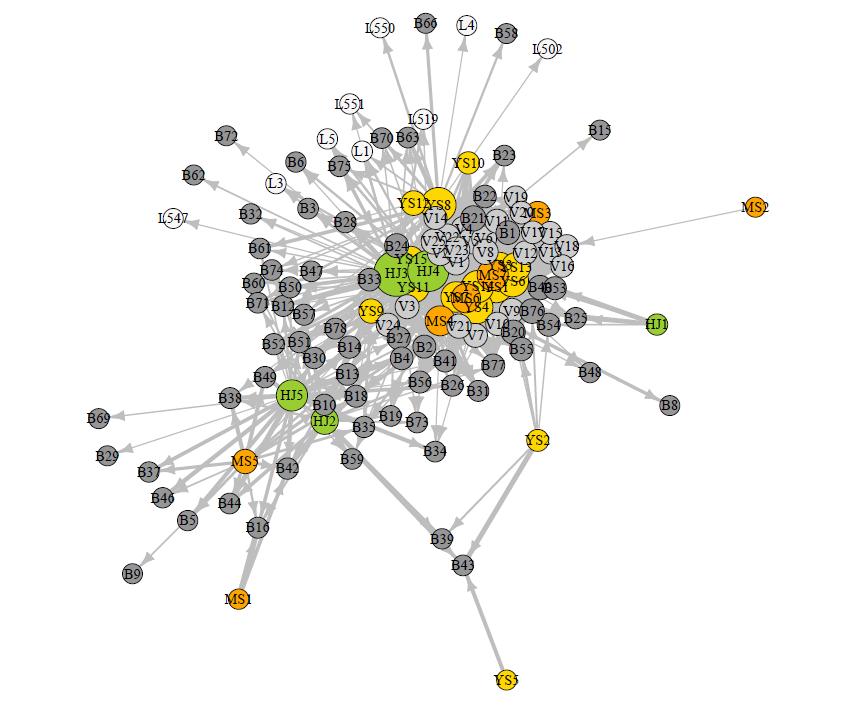

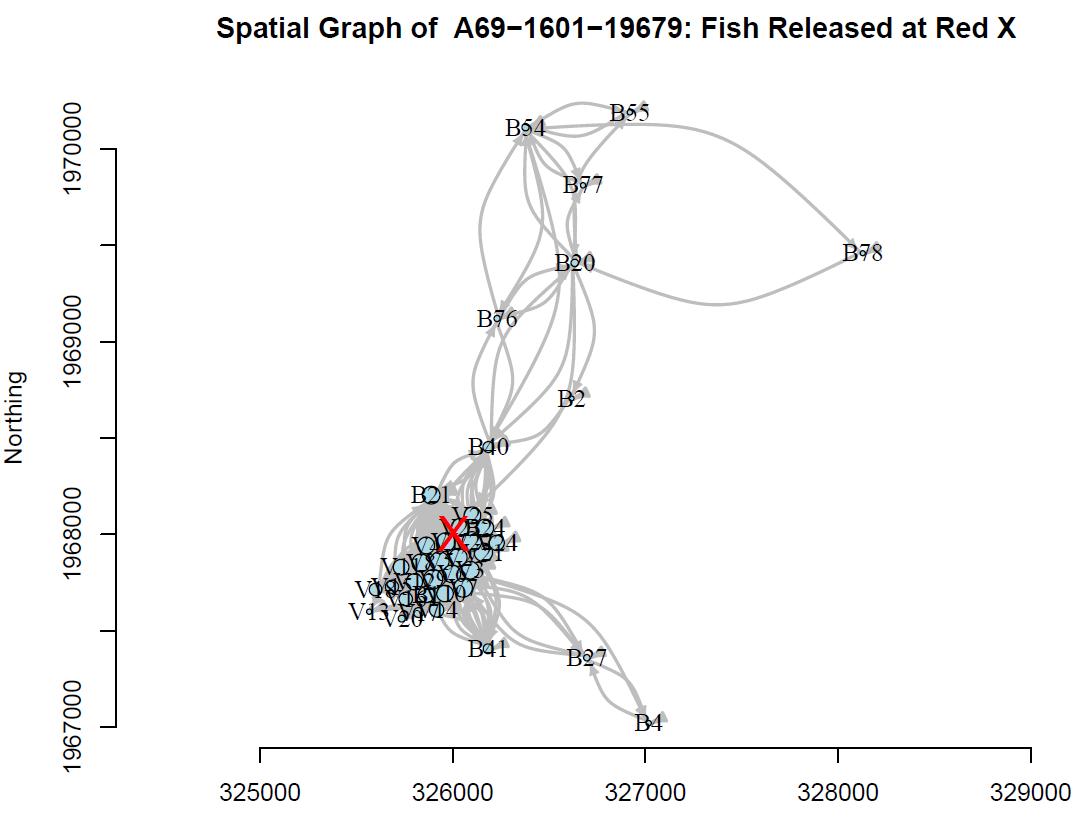

Broad scale movements of reef fish were visually analyzed using network analyses methods described by Finn et al. (2014). A bipartite graph was generated for the three fish species with two types of nodes (vertices) representing both the receivers and tagged individuals. The movements of fish between receivers is represented by the connections or edges between those nodes which can be weighted to indicate more use. Additionally, the amount of edges connecting to a certain node is considered the node’s degree, where a node that is small has relatively few connections (i.e. a fish that could have a small home range) as opposed to a larger node which has many more connections (i.e. a fish that is making large scale movements). Spatial plots were also

produced to assess the actual movements of fish based on placing the receivers in their actual (x,y) locations (Finn et al. 2014). A graph was created for each individual fish to determine if variability was occurring between the same species and across species. Arrows accurately represented the direction of movements to the successive receiver visited. If a fish was detected at the same receiver for two or more consecutive detection a loop back to that receiver is present.

Over the course of three separate tagging trips (May 2015, January 2016, and August 2016), a total of 15 yellowtail snapper, 7 mutton snapper, and 8 horse-eye jacks were acoustically tagged. Yellowtail snapper ranged in size from 21.0 to 35.5 cm (FL) with a mean (±SD) of 29.4 (± 4.02). Mutton snapper were overall much larger and ranged in size from 31.0 to 61.0 cm (FL) with a mean (±SD) of 51.6 (± 8.36). Only five horse-eye jacks were used for this analysis, due to three being recently tagged in August 2016 with no detection history available at the time of this preliminary analyses. Horse-eye jacks ranged in size from 35.5 to 62.0 cm (FL) with a mean (±SD) of 50.5 (±10.4). In total, 27 fish were used for the presented analyses.

Results and Findings

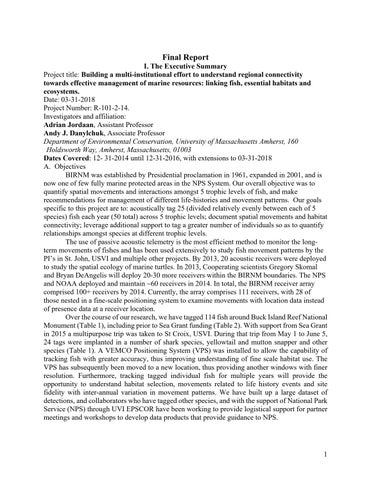

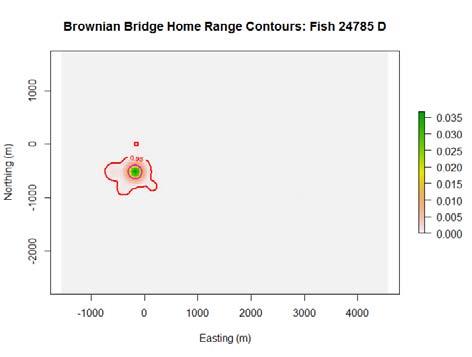

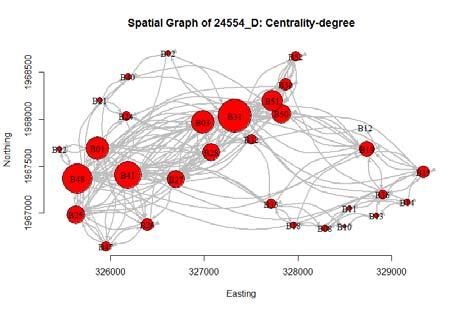

Graduate student Sarah Becker completed her analysis of barracuda movements and formalized the ability to estimate home range sizes using acoustic data as part of her M.S degree (2016). This work was submitted and published in Marine Ecology Progress Series. The analysis demonstrated some limitations of acoustic telemetry in accurately delineating the home range size and identified how biases in the interpretation of movement data may occur based on interactions between the ecology of the species and acoustic array design. Barracudas appear to have very small home ranged when sufficient detections are captured (Figure 2), although they also make significant deviations from a core use area (Figure 3). Another key result was that analytic method choice influenced the size of home range estimates. Further, the richness of detection histories influenced these same results, as well as the ability to determine ecological drivers of home range size, in this case changing body size (Becker et al. 2016).

Once appropriate methodological parameters were set, analysis generated estimates of the size and location of home range territories. Becker (2016) used the methods and detection histories determined as appropriate in Becker et al (2016) to expand on the home range assessments, looking more closely at site fidelity, habitat use, and key activity spaces for individuals and across the study population. We generating comparative population densities between BIRNM and a second study site in Culebra, Puerto Rico. We also validated our home range analysis through generating a generalized linear model that analyzes benthic habitat type, season, and fish individuality as drivers of observed spatial patterns. Generally, barracuda did not move long distances and instead use core home activity spaces heavily with occasion haphazard jaunts around the area. Further, no environmental variables explain movements.

Detection histories for each individual fish varied based on the time they were recorded within the receiver array. For example, four yellowtail snapper, two mutton snapper, and two horse-eye jacks were detected almost every day since the time of release by at least one receiver. In contrast, the majority of individuals showed varying levels of detections over time suggesting a more scattered use of the Monument.

The bipartite graph showed a tight clustering of both individual fish and VPS receiver nodes (Figure 4). Most yellowtail snapper (13 out of 15; 87%) showed a high affinity for receivers located within this area. Only seven fish (26%) showed stronger connections to receivers outside of the VPS array. In addition, one yellowtail snapper and two horse-eye jacks traveled to Lang Bank, an area approximately 10 km outside of the closest BIRNM boundary. These directed

movements remain unclear; however, Lang Bank is a known red hind Epinephelus guttatus spawning aggregation site (Nemeth et al. 2007).

The spatial movement plots for each fish varied based on species and between individuals. Yellowtail snapper were predominately detected within the VPS array with some small movements north along the shallow shelf habitat (Figure 5). It became apparent that yellowtail snapper caught and released near or in the VPS array showed a degree of site fidelity to this area. In contrast, the one individual that had sufficient detection history that was tagged off of a patch reef to the southeast of Buck Island showed a unique spatial usage of the Monument, with most detections occurring at the closest receiver to the capture and release location. Despite fishing effort throughout BIRNM, most yellowtail snapper were caught near the VPS therefore for any future tagging effort should be directed in different spots a larger sample of yellowtail snapper is warranted to further explore this movement behavior. Individual mutton snapper exhibited variable movement patterns, with a few fish showing an identical pattern to the yellowtail snapper. Two individuals showed highly variable movements, with one fish only visiting two receivers and the other fish moving between receivers only located south of Buck Island. Interestingly, there also appears to be a relationship between where mutton snapper were caught and released and the areas of BIRNM in which they use spatially and temporally. In contrast, each horse-eye jack showed highly variable movements with most fish exhibiting large movements around the entire Monument.

Part of this research is also interested in understanding the connectivity that tagged individuals have to areas outside of BIRNM boundaries. For example, one yellowtail snapper (tag 19672 or YTS8 in Figure 4) spent approximately 26 days outside of BIRNM (from 2/23/16 to 3/19/16), visiting 5 different Lang Bank receivers, managed by both NPS (Lang 01 and Lang 04) and collaborators at UVI (502, 550, and 551). The fish was originally caught and released near West Beach off Buck Island on 6/3/2015 and spent the first ~8 months in the immediate area. The initial timing of the movement to Lang Bank at the end of February coincided with a full moon phase, however, the extent of the stay remains unclear. Yellowtail snapper from the Campeche Bank in the Southeastern Gulf of Mexico, reach sexual maturity around 21.3 cm FL and 19.4 cm FL for females and males, respectively and had peak spawning in the spring (March to May) and fall (September) months (Trejo-Martínez et al. 2011). Therefore, it is possible that this individual fish (FL: 23.5 cm) was undergoing an extensive spawning migration out to Lang Bank, which has been noted as a spawning area for other species such as red hind. The distance travelled (~13.3 km) from receiver BUIS66 (last receiver visited before movement outside of BIRNM) to receiver 502 took approximately 38.9 hours which may be possible for a fish this small. Interestingly, all other yellowtail snapper of approximately similar size did not exhibit this behavior and stayed around the origin of capture and release with only small scale movements along the western shelf break of BIRNM. These data imply that BIRNM might be of sufficient spatial scale to protect the majority of yellowtail snapper for extended periods of time.

In addition, two horse-eye jacks (HJ3 and HJ4 in Figure 4) of comparable size made extensive movements to Lang Bank. One individual (tag 23603, FL: 56 cm) visited 4 receivers, moving outside of the boundaries of BIRNM during late March 2016 and sporadically reentering and leaving the Monument until the end of April 2016 when the fish moved back to the VPS array. The other horse-eye jack (tag 23601, FL: 62 cm) had a very similar movement pattern but visited 6 Lang Bank receivers, initially leaving BIRNM slightly earlier at the end of February 2016 until eventually moving back to the VPS array, when the last receiver download was collected. It is also interesting to note during these few months both fish, when reentering the Monument, went back

and forth between the VPS array, the place they were both originally captured, tagged, and released. Despite these two individuals being detected at Lang Bank during the same time of year, neither were detected simultaneously at the same receiver. From what little is known about this species, they are reported to form large schools, often numbering over 1,000 individuals, primarily occurring during full moon and waning moon phases between February and October along edges of reef drop-offs (Graham and Castellanos 2005). Usually schools will display extended pair courtship behavior, presumptively for spawning. For both individuals, detections at Lang Bank receivers occurred during full moon and waning crescent periods, suggesting this could be a potential spawning site for horse-eye jacks, supported by the fact that Lang Bank receivers follow the edge of the St. Croix shelf break.

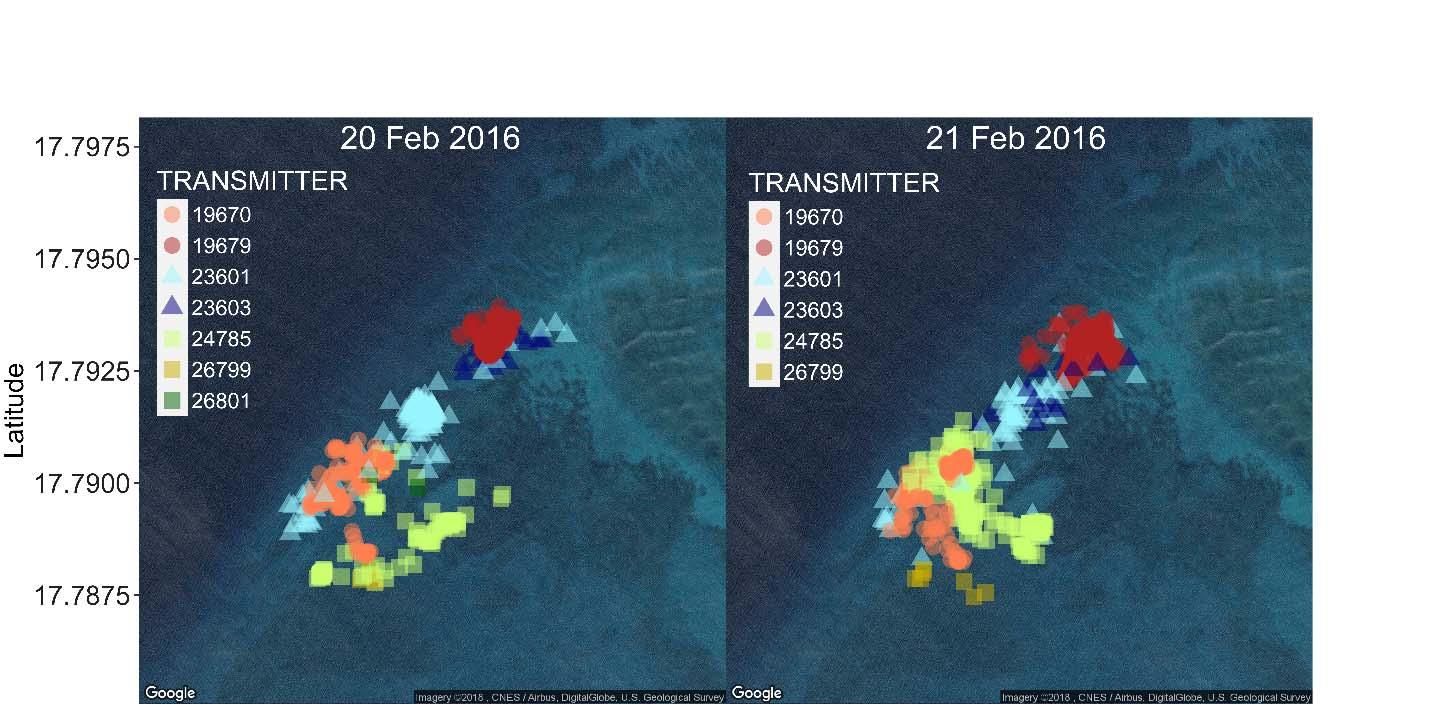

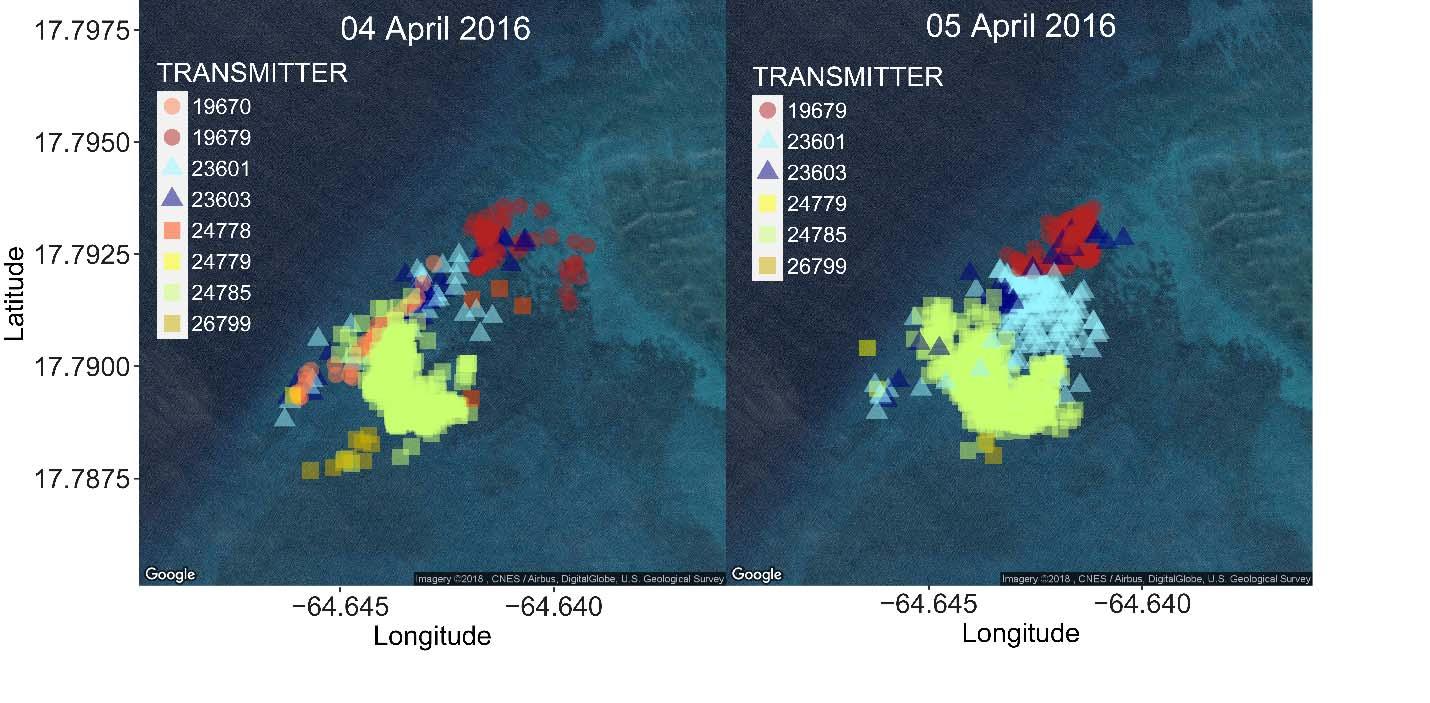

Species appeared to partition space in the location of a fine scale array (Figure 6). The results thus far for three species of reef fish shed light into the variability of movement among individuals and between different species. Incorporation of positioning data collected from the VPS will be used to determine specific habitat preference, movement directionality, and timing of movements for these species. Future analytical techniques, including geostatistical mixed models, will be explored and applied to address remaining questions on habitat usage, effects of environmental variables, and interactions between tagged species occupying the same space.

Products

A public presentation was given to stakeholders at a National Park Service and VIEPSCoR supported workshop. A multi-institutional grant proposal is being generated to help fund a postdoctoral researcher capable of analyzing data towards identifying synchrony and asynchrony at ecosystem levels (all species).

Publications accepted:

Becker, S.L., Finn, J.T., Danylchuk, A.J., Pollock, C.J., Hillis-Starr, Z., Lundgren, I., and A. Jordaan.2016. Influence of detection history and analytic tools on quantifying spatial ecology of a predatory fish in a marine protected area. Marine Ecology Progress Series 562:147-161

In Preparation:

Becker, S.L., Finn, J.T., Novak, A.J., Danylchuk, A.J., Pollock, C.J., Hillis-Starr, Z., Lundgren, I., and A. Jordaan. In Prep. Movement patterns, temporal variability in spatial use, and site fidelity for individual territories of great barracuda Sphyraena barracuda in Buck Island Reef National Monument, St. Croix, U.S.V.I.

Novak, A.J., Becker, S.L., Finn, J.T., Pollock, C.J., Hillis-Starr, Z., Danylchuk, A.J and A. Jordaan. In Prep. Fine and broad-scale movement ecology of yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus) within a marine protected area in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Literature Cited

Becker, S.L., J.T. Finn, A.J. Danylchuk, C.J. Pollock, Z. Hillis-Starr, I. Lundgren and A. Jordaan. 2016. Influence of detection history and analytic tools on quantifying spatial ecology of a predatory fish in a marine protected area. Marine Ecology Progress Series 562:147-161.

Graham R.T., and D.W. Castellanos. 2005. Courtship and spawning behaviors of carangid species in Belize. Fishery Bulletin 103:426–432.

Finn, J.T., J.W. Brownscombe, C.R. Haak, S.J. Cooke, R. Cormier, T. Gagne, and A.J. Danylchuk. 2014. Applying network methods to acoustic telemetry data: Modeling the movements of tropical marine fishes. Ecological Modelling 293:139 – 149.

Nemeth, R.S., J. Blondeau, S. Herzlieb, and E. Kadison. 2007. Spatial and temporal patterns of movement and migration at spawning aggregations of red hind, Epinephelus guttatus, in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Environmental Biology of Fish 78:365 – 381.

R-Core Development Team. 2014. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Selby, T.H., K.M. Hart, I. Fujisaki, B.J. Smith, C.P. Pollock, Z. Hillis-Starr, I. Lundgren, and M. K. Oli. 2016. Can you hear me now? Range-testing a submerged passive acoustic receiver array in a Caribbean coral reef habitat. Ecology and Evolution 6(14): 4823 –4835.

Trejo-Martinez, J., T. Brule, A. Mena-Loria, T. Colas-Marrufo, and M. Sanchez-Crespo. 2011. Reproductive aspects of the yellowtail snapper Ocyurus chrysurus from the southern Gulf of Mexico. Journal of Fish Biology 79: 915 – 936.

Tables and Figures

Table 1. Fish acoustically tagged in St Croix during 2015-2017.

Table 2. Fish acoustically tagged previous to 2015.

Figure 2. Brownian bridge estimated core use area for barracuda tag # 24785 (left) and # 24554 (right).

Figure 3. Network analysis developed metric of movements for barracuda tag # 24785 (left) and # 24554 (right). For reference, the arrow points to the location of Buck Island.

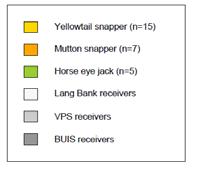

Figure 4. Bipartite graph of three species of reef fish tagged within BIRNM. Data are from May 2015 to May 2016 and have been filtered for simultaneous detections. Receivers have been divided into Lang Bank receiver nodes (outside of the MPA), VPS receiver nodes, and general receiver nodes placed in the broad-scale array (BUIS).

Figure 5. Example spatial movement plot of yellowtail snapper (A69-1601-19679). This individual had a total of 176, 638 filtered detections from May 2015 to May 2016. The red X indicates the release location of this fish. Receiver nodes in the VPS are labeled with “V” and the general receivers in the array are labeled with a “B”.

Figure 6. Daily snapshots of positioning data from O. chrysurus (n = 2; circles), C. latus (n=2; triangles), and S. barracuda (n = 5; squares). Two days in February and April 2016 were chosen based on the highest number of present individuals, although not all were present all days.