EvaluationofPerceptionsand ExperimentalPlantingTechniquesat ParqueLaEsperanza,Cataño,Puerto Rico

June 30, 2017

Award Number: NA14OAR4170068

CFDA Number: 11.417

Subaward Agreement Number: 2014-2014-016

Investigators

Concepción Rodríguez Fourquet, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamón

Juan Negrón Ayala, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamon

Steven A. Sloan, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamon

Nancy Villanueva Colón, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamon

Executive Summary

Evaluation of Perceptions and Experimental Planting Techniques at Parque La Esperanza, Cataño, Puerto Rico

June 30, 2017

Award Number: NA14OAR4170068

CFDA Number: 11.417

Subaward Agreement Number: 2014-2014-016

Investigators

Concepción Rodríguez Fourquet, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamón

Juan Negrón Ayala, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamón

Steven A. Sloan, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamón

Nancy Villanueva Colón, Ph.D. University of Puerto Rico at Bayamón

The objectives of this ecological and social study were: (1) To develop and alliance between the University of Puerto Rico Bayamón, Corredor del Yaguazo, Inc. (NGO) and the community of Cataño to work toward the development of a mangrove forest that will provide an important resource to an already extremely transformed coast. (2) To assess the perception of the local community regarding benefits of mangroves and the need to establish ecological sustainable practices. (3) To review and evaluate mangrove planting techniques with experimentation and literature review. (4) To develop and educational campaign geared towardthe protection of theforested mangrove. (5) To ensure its permanencywithinput ofthe community based organizations. (6) To evaluate the geographical natural and anthropogenic factors that have played a role in the development of Parque la Esperanza and the changes that these factors have produced in that area.

The objectives were achieved by accomplishing the following: (1) performing an experimental planting experiment in Parque La Esperanza, (2) conducting an ethnographic assessment to document community members’ perceptions of the ecological attributes, roles and importance of the mangrove, (3) evaluating maps, images and documents to document the physical changes in Parque la Esperanza and (4) visiting several schools to give demonstrative talks about the importance of mangrove forests and to present the results of our planting experiment.

This study provides ecological, geographical and social perspectives that can be used as model for future studies aiming to better understand the role that ecological and social components play in the present and future management of this coastal areas. It provides specific information of the planting of red mangrove in Parque La Esperanza and the best method for planting in areas that are exposed to wave action. For this specific location, which is a human-made peninsula, the planting of red mangroves in the wave exposed side of the peninsula, the use of attenuators specifically PVC pipes would be the best method.

Furthermore, our study contributes to understand the geographic changes of the area, and the social and situational factors enmeshed in shaping people’s ecological perceptions. We have assessed the nature and

human induced physical changes that have shaped this part of Cataño's coast in the past 50 years, and the suburban community members’ perceptions of the ecological changes that have taken place. As a result, we have learned that the attributes, roles and the importance of the mangrove system are defined not by the mangrove itself, but by their location and the social meanings ascribed to it. These meanings might also be shaped by social differences between the different communities that share the space, as the perception of residents in Bay View, Cataño greatly differs from that of the "outsiders" from other nearby lower income communities that use the area for recreation or for its resources. In that sense, our study shows that people's discernmentsand assessments of the natural resourcesare not necessarilyanchored in the “right”ecological information but in the makeup of their worldviews (i.e. aesthetics vs ecological function).

We encountered several difficulties in conducting our study. On the one hand, we faced communication setbacks with the city government and constant city staff turnover which implied having to renegotiate access to the study site, among other things. These complications delayed the beginning the ecological component.

In the sociocultural component, we experienced difficulties in scheduling interviews and meeting with differentstakeholders.Thesedifficultieswerepartiallyexplainedbythefactthatwewereinitiallyperceived as either being part of or working for the local NGO. There has been past animosity between the Bay View community and the local NGO because of their opposing views on the mangrove resources. Because of this perceived association, our ability to reach out to people from the community was affected in the first stages of the research. To overcome these problems, we asked for help from the community gatekeepers to alleviate any suspicions about our intentions and affiliations. Additionally, we intensified our visibility in the community by attending various meetings (i.e. Lions Club, towns meetings).

The project supported two Co-PIs and one associate faculty. All were on a nine month appointment with an amount of effort dedicated to the project of 2.25 person months. Sea Grant provided $28,571 and UPRB provided $28,571 per year of the project for a total of $57,142 provided by Sea Grant and $57,142 from UPRB for thetwo years. Four undergraduatestudentswere supported as researchassistants. Students were paid a total of $3,358.34 of which $1,679.17 was paid by Sea Grant and $1,679.17 by UPRB. An additional associate faculty, provided the geographical context and collaborated in the social component of this study. UPRB awarded $4,087 from the UPRB Research Committee for this purpose during the 2014-2015 academic year (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

We visited Cataño’s schools where we presented to 409 students, ecological information combined with hands-on activities about the mangrove food web and construction and analysis of graphs using data from the planting experiment. We organized a Mangrove Day at Parque La Esperanza. During which, we explained the planting experiments and had different activities related to mangroves. Two conferences about the transformation of Cataño’s coastal areas, were presented in at UPR in Mayaguez UPR-Bayamón.

1. RECAP -A team of ecologists and social scientists from the University of Puerto Rico at Bayamon conducted research that shows that people's discernments and assessment of the natural resources are not necessarily anchored in the “right” ecological information but in the makeup of their worldviews (i.e. aesthetics vs ecological function). The team also concluded that the planting of red mangroves in wave exposed areas is aided using attenuators, particularly ones made of PVC.

2. RELEVANCE - The problem of coastal erosion, people’s vulnerability and property security were the ultimate focus of this study. As part of the Bay of San Juan, the study site is a densely populated urban coast under a lot of anthropogenic development pressure that faces a chronic problem of erosion. The coastal area nearby the urban settlement and Parque La Esperanza are areas where mangrove is part of the natural landscape. Planting mangrove at this site has been seen by a locally based NGO as an option to help stabilize the peninsula and reduce erosion. However, mangrove is perceived by the community as an extraneous and disruptive element to an imagined urban landscape. Consequently, the mangrove planting initiative has been rejected by the community. Our study aim is, therefore, twofold. On the one hand, we reviewed and evaluated mangrove planting techniques to support the replanting initiative. On the other hand, we explored the way that ecological initiatives are perceived by the local communities in Cataño, Puerto Rico.

3. RESPONSE-Byworkingwiththecommunityof BayView,citygovernment officials, and alocal NGO, thisprojectadvancedourunderstandingoftherolethatecologicalandsocialcomponentsplayinthepresent and future management of an urban coastal area. Likewise, this study contributes to our understanding of how geographic changes of the area, and the social and situational factors enmeshed in shaping people’s ecological perceptions and how these factors shape ecological initiatives.

4. RESULTS - Mangroves systems are important coastal barriers that help protect the coastal communities from storm surges and tsunami events. The study area, Parque La Esperanza located at the entrance of the San Juan Bay and is exposed to high energy waves that, through accretion and erosion, limit natural regeneration of mangroves that could otherwise establish and help protect the park. The use of attenuators, specifically PVC tubes, worked best for planting red mangrove and may help Parque La Esperanza to increase the forest cover of the park.

In terms of the social-geographical component, the examination of government maps and documents enabledusevaluatethephysicalchangesthathaveoccurredinthestudyareaandtheimpactofsuchchanges in terms of coastal resources. It also allowed us to examine if those changes have increased stakeholder's vulnerability to heavy rain events. Meetings with focus groups and personal interviews with residents shed light into their perceptions about the resources, environmental issues and hazardous conditions in the study area. It also provided clues on how these perceptions could potentially influences ecological initiatives.

By disseminating information in schools regarding the ecological relevance of the mangrove forest, as well assharingtheresultsofthemangroveplantingexperiment,studentsandteachersbenefitedfromtheproject. In interviews with the study stakeholders we explored the possibility of conducting meetings between Bay View neighbors and the local NGO. We envision these meetings as a prelude to develop a working collaboration regarding the ecological initiatives in the area.

Final Report Narrative

A. Brief Statement of the Problem

The project addressed the issues highlighted in current scientific literature on ecology restoration and community participation by applying a multidisciplinary approach to study the factors influencing the implementation of a mangrove reforestation initiative. In the absence of local research on the subject, this project advanced our understanding of the indigenous ways in which social relationships and the sociocultural context influence ecological initiatives.

B. Methods used

Ecological Component

Since the initial planting of 210 red mangrove propagules in Parque La Esperanza, Cataño (7th February 2015), we returned to census the propagules 16 times (approximately every two weeks) until 13th November 2015 (Table 4). We replaced dead and missing propagules on March 21st , 2015. We then decided to declare in future censuses, any propagule not visible from the surface as missing, that is, it may be alive, but buried or it may be gone from where it was originally planted. Our justification was that confirming whether the propagule is missing is very invasive and could affect growth and therefore the results of the experiment. On June 6th, 2015, we planted an additional 90 propagules in three experimental blocks in a randomized design like the previous planted blocks (I-VI). There are three areas with three blocks per area. Area 1 has blocks (I-III), area 2, blocks IV-VI and area 3 VII-IX. Areas 1-3 are located progressively closer to the ocean. Area 1 is least affected by tidal flux, wave action, and accretion.

Bamboo encasement treatment is segments of cut bamboo that were dried and had inner segmentation membranes removed. Segments ranged in length from 50-70 centimeters. The PVC encasement treatment were 4-inch diameter thin walled PVC cut to 70 cm and split lengthwise on one side and the sticks treatment are wooden dowel rods that were 45 cm in length. A single propagule was planted in each tube or tied to the dowel with grafting tape, in the case of the stick treatment. In blocks VII-XI the encasements and sticks were longer (100 cm) and these blocks were located closer to the high tide mark.

During each census, we photographed plots and noted the status (alive, missing or dead) of

propagules. In September 2015, we began measuring the height of propagules. Height was measured from the top of the propagule to the tip of the shoot.

On March 4th 2016, we returned to the plots to remove the PVC tubes from around propagules before the propagules grew prop roots that would prevent their removal. We could remove most tubes. We poured water over the sand and propagules to permit the PVC tube to move around the propagule and then carefully, we twisted the tube back and forth until the tube could slide free of the propagule, resulting in minimal disturbance to propagule.

Data analyses

To determine if there were differences among treatments (PVC, bamboo and stick) on propagule survival we used a Chi Square. The total number of propagules Alive, Missing, or Dead were compared among treatments.

Growth, in centimeters per day, was calculated by recording the date of first leafing and then counting the number of days to the 9th of October 2015. We then divided the size of the propagule on October 9th by the number of days of growth to determine the per day growth. A KruskalWallis test was then used to determine the treatment effect on propagule growth.

Social Component

The informed consent for the sociocultural component was developed following the guidelines provided by National Institute of Health (NIH). It was then presented and approved by University of Puerto Rico Bayamón Internal Review Board. The participant observation phase was initiated on November 2014 at several sites. Observations were conducted at government meetings, NGO events and at both the community and the ecological areas. This resulted in several connections within the NGO, the government and the community.

Ten semi-structured individual interviews were conducted. These individuals represent members of the NGO, the community, the government and the private sector.

A focus group with community members was conducted in April 2016 with 10 residents of Bay View. We decided to conduct this type of group interview given the reluctance of community memberstobeindividuallyinterviewed.Wehavebeenperceivedas eitherbeingpartoforworking for the local NGO. Because of this perception of the NGO as outsiders by community members

our ability to reach people from the community has been affected. By participating in several community and NGO meetings, we began to dissipate those perceptions. This active participation at meetings helped us access the private sector. An interview was finally conducted with a representative of that sector after multiple attempts. All the interviews were transcribed. Codification and a systematic categorical content analysis of the transcribed interviews and field notes was conducted.

For the geographical perspective, historical maps, documents and images were used to evaluate the physical changes that have occurred at the research site. We wanted to visualize changes on the landscape in terms of hydrography, vegetation, ecological systems and settlements. Historic maps dating from the 19th century were compared to present maps and satellite images. Sites visit and observations were used to document the uses of resources of the area by residents and visitors.

Interviews with people in charge of the water pumping station at Bay View allowed us to see its important role to reduce flood vulnerability of communities located near Las Cucharillas wetland and at the Bay View area. Meeting with other researchers that work at the study area allowed us to gain access to important information about human activities that have compromise the environmental quality of the area. This gives us a greater picture of the human impact and on the geographical context of Parque La Esperanza and neighboring communities.

III. Results and findings

Ecological Component

Results showed no significant difference in propagule germination among the treatments (Figure 1). There is higher germination variability in the wooden dowel treatment (stick) compared to the other treatments.

No difference was observed among treatments for mean percent propagule mortality. Overall, combined propagule mortality was 33% (Figure 2a). Trends were observed for mean percent missing propagules and mean percent propagules survival (Figures 2b and 2c): PVC encasements resulted in fewer missing propagules (13%) and tying propagules to sticks, resulted in the most missing propagules (37%); PVC encasements exhibited the highest mean survival (60%) whereas, in the stick treatment mean survival was lower (32%). Most surviving propagules were found in the PCV encasement treatment. Most missing propagules were in the stick treatment. This shows

that the PVC and bamboo are attenuators of wave action and other conditions to which the propagules were exposed.

Within each block area, block treatments responded similarly (Figure 3). Areas 1-3 were progressively closer to the shore and the associated wave action. While all plots displayed evidence of being washed by tidal influx, namely the buildup of debris (trash and vegetative) and accretion of sand this appeared to increase with proximity to shore. Even though the encasements and sticks were longer in blocks VII-IX, exposure to waves removed most sticks and greater accretion buried most encasements.

The surviving propagules in all treatments, did not show a difference in growth between the treatments (H = 4.96 df = 2 p = 0.084).

Social Component

Results from observations and individual and group interviews showed that Cataño suburban community members’ perceptions of the ecological attributes, roles and importance of the mangrove are defined not by the mangrove itself but by their location. Participants make distinctions between the mangroves that grow at the ParqueLaEsperanza from the one that grows at the coastline nearby their houses. The former is perceived as a natural barrier to pollution and erosion and as an innate component of the Esperanza Bay. No concerns were articulated against those mangoves. The latter, on the contrary is perceived as a foreign element which was not part of the neighborhood’s original design. This perception is grounded on an idyllic imagined neighborhood environment. On the one hand, old-timer neighbors invoked primal conditions of the neighborhood to portray the mangrove as an obstruction to the harbor view which, according to them, is one of the main assets of their properties, and the mangrove contributes to lower the market value of their properties The presence of mangrove along the neighborhood coastline is seen as wild and unplanned and even attributed to sewage sludge. Hence it is defined by community members as not righteous and therefore, destroyable. On the other hand, mangroves are seen as a source of mosquitoes, garbage and pungency. Some participants stated that the mangrove could harbor criminal activity (mainly related to drug trafficking) which generates a sense of lack of security in the community. The latter perception emerged as the main objection to the neighborhood mangrove. The only practical solution participants proposed was the complete elimination of the coastline mangrove in front of their houses.

A sense of ownership of the communal areas where mangroves are located commonly emerged from participant responses. Some participants explicitly demand to have a word regarding the conditions of these communal areas because they usually mow and clean these areas. The distinction between public and private spaces becomes rather permeable. In fact, they commonly complain about the recreational use of these areas by individuals they consider “outsiders” or “strangers”. This perception of “outsiderness” is extended to the NGO which is promoting the mangrove planting in the coastline zone. This ecological initiative is seen as an unjustified intrusion done without consulting the community to modify an area which is perceived to belong to this specific neighborhood instead to the entire municipality of Cataño. This situation has generated an enormous tension between these two sectors, creating resistance to any ecological initiative in that area in particular. As we reported previously, we were perceived as either being part of or working for the local NGO. Because of this perceived association our ability to reach people from the community was negatively affected. Our findings have shown a lack communication between these two sectors.

Given the reluctance of this group to be individually interviewed, a focus group was conducted with 10 residents of the community At the focus group a meeting/dialog between the community and the NGO was proposed and the participants were interested. This possibility was explored between leaders from both sectors and showed openness to the idea.

Geographic Component

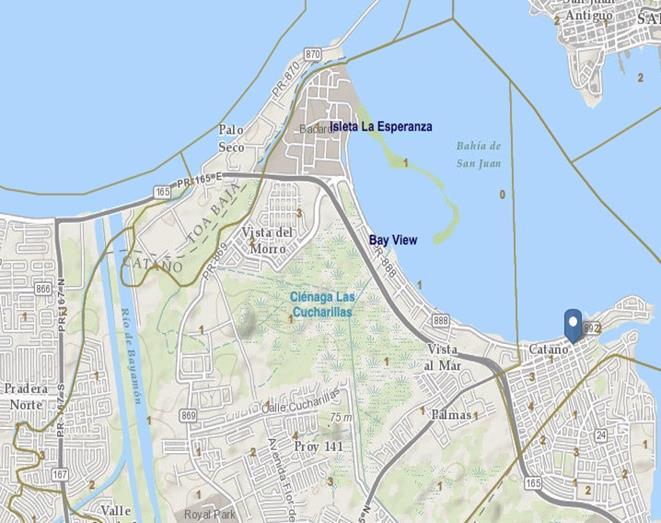

The study area has various physiographic features that have changed though its history. On the west and north portion, it is bordered by the Bayamón River and its floodplain. The coastline on the eastern portion lies across the island of San Juan and extends from the mouth of Bayamón Riversouthward to Punta deCataño, which marks thesoutheast limits ofCataño.A recent addition to the coastline originated as a tidal sandbar caused by human intervention and has evolved as a peninsula that houses Parque La Esperanza, and an elongated islet that extends back to the shore surrounding an interior lagoon. Inland, the most dominant element is the 1,236 acres of marsh wetland of Las Cucharillas, located between the Bayamón River floodplain and the coast. Our study area concentrates on the northern portion of Cataño, from Las Cucharillas to the La Esperanza peninsula and islet.

Study area evolution: 18th to 19th Centuries

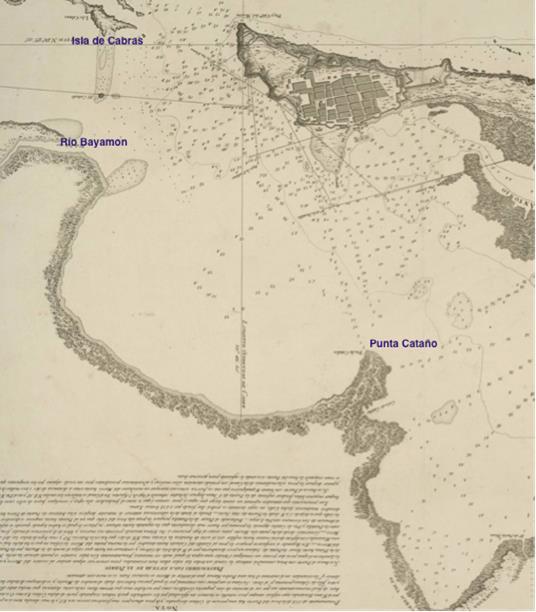

An examination of earlier maps dating from a Spanish colonial period illustrate a completely different coastline of the study area. The map from Cosme de Churruca (1794) unveils an intact area of Cataño, were Isla de Cabras was only an outcrop of rocks (possibly coral rubble) guarding the entrance of the San Juan Bay. La Esperanza peninsula was nonexistent, with a coastline possiblyforestedbymangroves(Figure4). However,lessthan100yearslater,thehumanfootprint is evident. A later map from Roldan y Navarro dating from 1887 shows a small village settled on a portion of the shore of Cataño, south of what todayis Bay View. There are two elements present in both maps; the Bayamón River and Punta de Cataño, without major changes. However, on the 1887 map,it appearsthat theshorelinewas mainlyasandybeach with no signs ofmangroveforest. A possible explanation for this is that the Spanish government had policy that encouraged the elimination of mangroves. In 1873, the governor approved an ordinance allowing people to settle legallyiftheycleared mangroves, filledthewetlands andbuiltstructures on coastal land(Seguinot, 1997). Needless to say, that policy enticed the modification of the coastline along the Bay of San Juan, destroying ecological systems and altering the drainage patterns. That map also depicts in detail intense agricultural activity, surrounding the western portion of Cienaga Las Cucharillas. The abundance of surface water was evident, and water canals, probably used for irrigation or to drain the area, can be seen on that map (Figure 5)

Recent transformations

The entrance to the 20th Century brought along political and economic changes that accelerated the transformations of the San Juan Bay and the Cataño area through the development of the port and road infrastructure, industrial activity and an increase of population settlements. Maps dating from 1941 (U.S. Geological Survey) illustrate an increase in urban population in the center of Cataño (Figure 6). However, the marsh land surrounding Las Cucharillas remained almost the same,with farmsactivityontheperiphery,lowpopulation densitiesandnewlines thatcrisscrossed the area to collect and deviate surface water. The presence of surface water and swamps and flooding presented constraints to further development. According to documents examined during that period, with the expansion of military operations into Fort Buchanan, the United States government put into effect an intensive program to eradicate the mosquito that carried malaria. Thus, along with aggressive fumigation programs, the construction of channels took place, with

the intention to redirect and pump water into San Juan Bay (Miranda y Casta, 1997). Malaria was eventually eradicated, but this also represented an opportunity to change the landscape significantly. The federal and local government, sponsored the construction of Caño La Malaria (La Malaria Creek), a channel that receives most of the runoff that drains from elevated points west and south of the Bay, helping to keep the northern coastline of Cataño dry. Seizing that opportunity, unplanned communities grew around the Cataño area. At the end of that decade, Bay View, the first planned urbanization of Cataño was built, right were Caño La Malaria flows. This is the community we focused on, for the social component of this research. As of today, the channel is the dividing element between BayView West and Bay View East (Figure 7). The pump station at Caño La Malaria pumps 30,000 gallons per minute, but that quantity is adjusted depending of amount of rain and the sea level fluctuations. This station, together with two other stations keep most of Cataño’s flood waters under control. Flood control projects intensified during the decades of 1970's and 1980's with the channelization and re direction of Rio Bayamon to the north coast, and this allowed for the development of planned urbanizations and industrial activity.

Another human made element helped change this coastal landscape even further. In the early 1980’s, dredged material from the San Juan Bay was deposited by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) near the shore across West Bay View. On 1982 topographic maps there is no sign of the deposited material. Though the past decades, sediments flowing into the area from Caño La Malaria and the dredged material of the bay created a sandbar that attached to the northwestern tip of the shore, trapping the incoming sediments and creating an island that enclosed the area. Eventually the USACE created two openings on the island and built ditches to keep them from closing. This resulted in twonew physical elements; a peninsula (laterdeveloped into Parque La Esperanza), and an island that has been growing by accretion and is reaching the shore. Its northern shore is subject to high wind and currents, making it difficult for mangroves to grow. But there is an area of lower energy that has accrued and created an additional, but smaller peninsula in the leeward side of Parque La Esperanza. That is the study area where mangrove experimentation techniques took place for the ecological component of this research (Figure 8).

There is a major concern for the environmental implications of the sediments flowing from Caño La Malaria towards Parque La Esperanza peninsula and islet. We have to bear in mind that the

creek collects runoff waters from the land surrounding Las Cucharillas Marsh, which has an intensive industrial use. During the past three decades, industrial activities such as distilleries, oil refineries and thermoelectric operations have been encroaching on the area. Studies performed by Mejías, Musa and Otero (2013) evaluated the presence of metals on sediments from three mangrove species. Samples located at various points inside the lagoon and on the shore, pointed to the presence of aluminum, cadmium, lead, arsenic and other toxic metals. Furthermore, most of the communities located inside the basin of Las Cucharillas are not connected to the sewage system.Theyuseseptictanksburiedinthearea.Hencemuchoftherunoff waterthatflowsthrough Caño La Malaria has fecal contamination. The fact that local people use the resources of the area forfishing,andrecreation,andthatthefishandmolluskpopulationslivinginsidethelagoon,might then represent a risk to public health. Local people were interviewed at site and mentioned that there is abundant fish, shrimps and mollusks.

Another concern is that even though the peninsula and the islet creates a protective barrier against storm surge waves and possible tsunamis, in an extraordinary event of rain, the flow of water through Caño La Malaria can increase significantly. The barrier impedes the efficient flow to the bay making residents of Bay View West more vulnerable to floods

III. Objectives accomplished

Objective 1. To develop an alliance between the University of Puerto Rico Bayamon, Corredor del Yaguazo, Inc. (NGO) and the community of Cataño to work toward the development of a mangroveforest thatwill provideanimportant resourceto an alreadyextremelytransformed coast. A working collaboration was established with the directive of the local NGO which facilitated the communication with local government, community gatekeepers, schools and other stakeholders. We participated in important activities of the NGO such as, the signing of the co-management agreement with Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, inauguration of the community technological center at the NGO facilities, the Cataño’s City Council recognition of the NGO directive, and the showing of a documentary about the ecological contribution of the NGO directive to the wetland.

Objective 2. To assess the perception of the local community regarding benefits of mangroves and the need to establish ecological sustainable practices.

Ten semi-structured individual interviews were conducted. These individuals represent members oftheNGO,thecommunity,thegovernmentandtheprivatesector.Afocus groupwithcommunity members was conducted with 10 residents of Bay View. We decided to conduct this type of group interview given the reluctance of community members to be individually interviewed. As we reported previously, we have been perceived as either being part of or working for the NGO. Because of the perception of the NGO as outsiders by community members our ability to reach people from the communityhas been affected. Our participation in a several community and NGO meetings helped to dissipate those perceptions. This active participation also helped in accessing the private sector.

Objective 3. To review and evaluate mangrove planting techniques with experimentation and literature review.

The planting experiment concluded. The review of literature was performed during experimental planting.

Objective 4. To develop an educational campaign geared toward the protection of the forested mangrove.

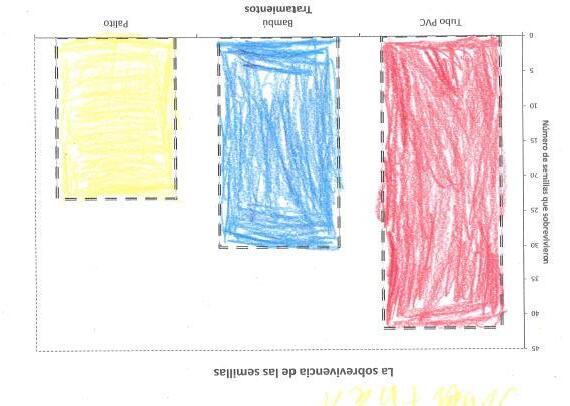

Students participating in the 4-H program and Corredor del Yaguazo assisted in the planting of red mangrove. One of the students supported by the project, Vernadee Ortiz, gave an introduction about mangrove species and highlighted the importance of mangrove forest. We visited five schools in Cataño, one high school, one middle and three elementary schools and talked to 409 students (Table 5). We presented a 20-25-minute talk about the red mangrove, its life cycle and importance in the ecosystem. In the talk we showed red mangrove propagule and propagules and encouraged the children hold the propagules and touch the leaves of the plant. After that, we talked about how red mangroves are habitat for other species and we provided a coloring page showing the red mangrove roots and organisms living among them. In the 2016 school visits, we presented the results of the mangrove planting experiment. The conference included aspects of the scientific method, importance of mangroves and data analysis. We prepared an activity where students constructed a histogram using the data from the experiment. See Appendix C for examples of graphs and evidence of conference.

On October 24, 2015 we held an event called “Dia del Mangle” at Parque la Esperanza. The

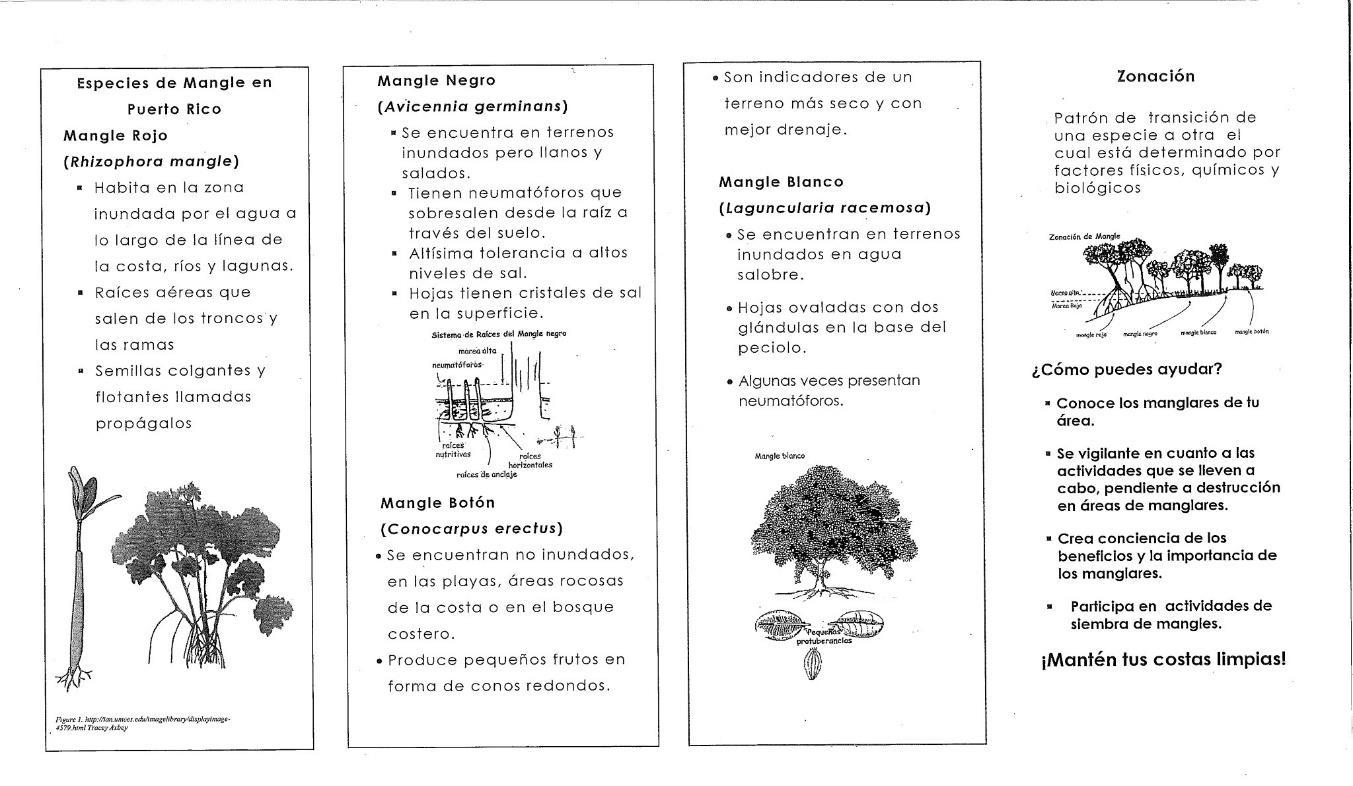

objectiveof the event was to educate students and public about the importanceofmangrove forests and to show experimental planting experiment to the public. We had a program that included a walk to the planting experiment area and a walk to show the different species of mangroves. The program also included games about the importance of red mangrove roots and to develop consciousness about trash in coastal areas. The program ended with a reading of a story, “Celita y el Mangle Zapatero”. The undergraduate student Vernadee Ortiz was the leader in the games and storytelling. A total of 24 persons attended the event. The participants included young people from a group called WhyNot?, 4-H volunteers, representatives from Extension Service in Cataño, Corredor del Yaguazo and the interim administrator of Parque La Esperanza who was also representing Cataño’s mayor. Also, we distributed a brochure with information about the importance of mangrove forest and tips about the identification of the species. See Appendix C for additional information, pictures and brochure.

Objective 5. To ensure its permanency with the input of the community based organizations.

Because of this project, we have developed an active relationship with the NGO. One of the co PI’s is developing a research project about land crabs in the wetland area. In interviews with the study stakeholders, we explored the possibilities of conducting meetings between Bay View neighbors and the local NGO. We envision these meetings as a prelude to the development of potential working collaborations regarding the ecological initiatives in the area.

Objective 6. To evaluate the geographical natural and anthropogenic factors that have played a role in the development of Parque la Esperanza and the changes that these factors have produced in that area.

Research has been made to better understand the geographic context of the study area. It is important that we understand the particular physical characteristics of the study site, and the ways in which the area has been transformed dramatically by human activities related to the San Juan harbor. Contemporary as well as old documents, maps and photos were gathered and examined to assess the changes that have occurred through the decades, in particular, the changes that have directly impacted the communities in the Cucharillas, Bay View and La Esperanza area.

Recommendations

As a result of this study, we make the following recommendations:

1. Conducting meetings between Bay View neighbors and the local NGO. We envision these meetings as a prelude to develop potential working collaborations between these sectors regarding the ecological initiatives in the area.

2. Sharing the results of this study with city government to provide basis for the design of locally- appropriate and sound environmental policy

3. To increase forest cover at the park, we recommend using PVC attenuators for any future planting of red mangrove at Parque la Esperanza

4. Enticing government agencies responsible for the management of the Caño La Malaria to improve the water flow to the bay to reduce flooding risk in the area.

Bibliography

Bauzá-Ortega, J. (2012). Evaluación de riesgos, vulnerabilidad y adaptación ante el cambio climático, Estuario de la Bahía de San Juan. Programa Estuario de la Bahía de San Juan. Programa Estuario de San Juan

Bauzá, J. (2009). Segundo informe sobre la condición ambiental del Estuario de la Bahía de San Juan Edición 2009. Programa del Estuario de la Bahía de San Juan. http://www.estuario.org/index.php/area-cientifica

Bush, D. M., Webb, R., González Liboy, J., Hyman, L., & Neal, W. (1995). Livingwith the Puerto Rican Shore. New York. National Audubon Society and Duke University.

Bush, D. M., Richmond, B., & Willam Neal. (2001). Coastal Zona Maps and Recommendations: Eastern Puerto Rico. Environmental Geosciences 8(10), 38-60.

Churruca, C. (1794). Plano geométrico del puerto de la capital de la Isla de Puerto Rico. Archivo Histórico de Puerto Rico. Núm. 1161-1162

Conservation and Management Plan. Programa de Estuario de San Juan

Cuerpo de Ingenieros Militares. Roldan y Navarro. 1887. Plano de la Plaza de San Juan de Puerto Rico.

De Blij, H. (2005). Why Geography Matters. Oxford University Press

Depósito geográfico e histórico del ejercito- Defensa de Puerto Rico. Memorial 1859. Madrid.

Ellis S.R. (1976). History of the dredging and fillings of lagoons in the San Juan area. U.S. Geological Survey.

EPA. Dredged Material Management Program.

http://www.epa.gov/region2/water/dredge/prusvi.htm Accedido 10/marzo/2013

Fontánez Aldea, R. (2007). San Juan Waterfront: Evaluación Arqueológica y Subacuática. CSA Arquitects and Engineers. San Juan

García López, G. (2013). Moving Towards a Sustainable Estuary: Google Satellite Images, Google Maps, Google Earth, 2016

Junta de Planificación. (2008). Declaración de Impacto Ambiental Estratégica, área de planificación especial y reserva natural Ciénaga Las Cucharillas. San Juan.

López Marrero, T., & Villanueva Colón, N. (2006). AtlasAmbientaldePuertoRico. Capítulo 10, Costas. Editorial UPR. San Juan

Mejías, C.L., Musa, J.C. & Otero, J. (2013). Exploratory evaluation of Retranslocation and Bioconcentration of Heavymetals in Three Species of Mangrove at Las Cucharillas Marsh, Puerto Rico. The Journal of Tropical Life Science. 3(1), 14-22.

Miranda Franco, R., & Casta Vélez, A. (1997). La erradicación de la malaria en Puerto Rico Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2(2).

Oficina de Planificación de Cataño. (2006). Declaración de Impacto Ambiental (DIA) Estratégica del Plan de Ordenación Territorial. Municipio de Cataño.

Oficina de Planificación de Cataño. (2006). Proyecto de reconocimiento general de propiedades históricas del sector costero del Municipio de Cataño. Informe final, 22 de diciembre de 2006. Municipio de Cataño.

Palacios, L. D. (1961). Departamento de Salud de PR. Negociado de Control de Malaria. Informe sobre la lucha antimalarica en Puerto Rico. Accedido en http://libraria.rcm.upr.edu:8080/jspui/handle/2010/1554

Pico, R. (1975). Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico. Editorial Universitaria. Río Piedras.

Quarto, A. (2003). Local Thai Communities Rescue the Sea and Themselves by Protecting Mangroves. National Wetlands Newsletter. 25(1)5.

Report on the Implementation of the San Juan Bay Estuary’s Comprehensive

Seguinot Barbosa, J. (1997).San Juan, Puerto Rico, una ciudad al margen de una bahía. Ediciones Geo: San Juan

Sepúlveda, A. (1989). San Juan Historia Ilustrada de su Desarrollo Urbano, 1508-1898, Centro de Investigaciones Carimar, San Juan P.R.

Sutton, A. H., Sorenson, L.G. &. Keelye, M.A. (2001). Wondrous Wetlands: Teachers’ Resource

Book. West Indian Whistling-Duck Working Groups of the Society of Caribbean Ornithology, Boston MA. Spanish Edition

U.S. Census. 2010. Censo de población y vivienda

U.S. Department ofCommerce.National Oceanic andAtmosphericAdministrationN.O.A.A.1996 Carta Naútica 25670. Bahía de San Juan.

United Stated Geological Service, Topographic Quadrangles of Bayamón: 1945, 1969, 1982

United Stated Geological Service, Topographic Quadrangles of San Juan: 1945, 1969, 1982

Appendix A – Tables

Table 1. Students supported by the project.

Supported MA/MS

Sea Grant Supported PhD

Sea Grant

Supported BA/BS

Table 3. List of Co-PI’s and associate faculty time and amount paid.

Name Percent Time Dedicated to Project

Aug 2015- June 2017

Amount paid/SG match during reporting period

Aug 2015 - June 2017

Concepción Rodríguez FourquetCo-PI

Juan Negrón Ayala - Co-PI

Steven A. Sloan - Associate Faculty

25% per semester X 4 semesters

25%/semester x 4 semesters

25%/semester x 4 semesters

$7881/semester

$7881/semester

$8743/semester

Table 5. Schools and number of students impacted with the talks and activities about the

August 17, 2015

September, 9 2015

September 14, 2015

September 16, 2015

September 30, 2015

Colegio Génesis de Esperanza, Cataño, PR

Escuela Horace Mann, Cataño, PR

Escuela Rafael Cordero, Cataño, PR

Escuela Horace Mann, Cataño, PR

Escuela José A. Nieves, Cataño, Puerto Rico

November 26, 2016 Escuela José A. Nieves, Cataño, Puerto Rico

November 18, 2016

December 2, 2016

December 7, 2016

Escuela Rafael Cordero, Cataño, PR

Escuela Ernesto Toro Rodriguez, Cataño, PR

Escuela Rafael Cordero, Cataño, PR

Figure 1. Mean percent germination of red mangrove propagules among planting treatments during an experimental planting in Cataño, Puerto Rico. Treatment

Figure 2. Results of a propagule planting experiment wherepropagules wereplanted in PVC and bamboo tubes and others were tied to dowel sticks with grafting tape, were planted in blocks of 35 propagules in a randomized block design. Top Panel Mean propagule mortality in red mangrove propagules from February to October 2015. There was no difference among treatments. Middle Panel. Fewer propagules went missing in the PVC tube compared to the stick treatment.

Bottom Panel More missing propagules in treatments meant that they were unavailable for monitoring. The uncertainty associated with this category lead to an underestimate of mean mortality or survival in the stick treatment. Error bars are ± 1 SE of means.

Figure 3. Area effects in red mangrove planting experiment. Increased missing propagule (Area 1- to Area 3) is thought to be due to closer proximity to the ocean and exposure to greater wave action.

(c) January 2016: Approximately 29.30 meters

Figure 9. Accretion process1995 to 2016

(a) 1995: Approximate distance 241.64 meters (b) 2006: Approximate distance 149.50 meters (c) January 2016: Approximate distance 29.30 meters

Appendix C – Bibliography

Abila, R. (2002). Utilisation and economic valuation of the Yala Swamp wetland, Kenya. Strategiesfor WiseUseof Wetlands:BestPracticesinParticipatoryManagement. Wetlands International Publication, 89–96. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.195.3006&rep=rep1&type=pdf#p age=96

Alongi, D. M. (2002). Present state and future of the world’s mangrove forests. Environ.Conserv., 29(3), 331–349. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892902000231

Álvarez-León, R. (2003). Los manglares de Colombia y la recuperación de sus áreas degradadas : revisión bibliográfica y nuevas experiencias. Madera Y Bosques, 9(1), 3–25. Retrieved from http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/pdf/617/61790101.pdf

BAIGORRÍA, D., RODRÍGUEZ, G., DOMÍNGUEZ, O., & MILIÁN, I. (2008). Nueva experiencia en la restauración de manglares, Playa Las Canas, La Coloma. Revista Forestal Baracoa, 27(2), 3–12.

Barbier, E. B. (2016). The protective service of mangrove ecosystems : A review of valuation methodsMarinePollutionBulletinspecialissue :“Turningthetideonmangroveloss.” MPB, 1–6. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.01.033

Blasco, F., Saenger, P., & Janodet, E. (1996). Mangroves as indicator of coastal change. Catena, 27(3), 167–178. http://doi.org/10.1016/0341-8162(96)00013-6

Blaustein, R. (2008). Global Human Impacts. BioScience, 58(4), 376. http://doi.org/10.1641/B580419

Boromthanarat, S., & Chaijaroenwatana, B. (2006). Community-led Mangr ove Rehabilitation : Exper iences fr om Hua Khao Community , XVI(2), 57–73.

Bosire, J. O., Dahdouh-Guebas, F., Walton, M., Crona, B. I., Lewis, R. R., Field, C., … Koedam, N. (2008). Functionality of restored mangroves: A review. Aquatic Botany, 89(2), 251–259. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2008.03.010

Crooks, S., Herr, D., Tamelander, J., Laffoley, D., & Vandever, J. (2011). Mitigating Climate Change through Restoration and Management of Coastal Wetlands and Near-shore Marine Ecosystems: Challenges and Opportunities. Environment Department Papers, 121(121), 1–69. Retrieved from http://wwwwds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2011/04/07/000333038_ 20110407024117/Rendered/PDF/605780REPLACEM10of0Coastal0Wetlands.pdf

Dahdouh-Guebas, F., Jayatissa, L. P., Di Nitto, D., Bosire, J. O., Lo Seen, D., & Koedam, N. (2005). Erratum: How effective were mangroves as a defence against the recent tsunami? (Current Biology (2005) 15 (R443-R447)). Current Biology, 15(14), 1337–1338. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.025

Das,S.,&Vincent,J.R.(2009).Mangrovesprotectedvillages andreduceddeathtollduringIndian super cyclone. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(18), 7357–7360. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0810440106

Demopoulos, A. W. J., Fry, B., & Smith, C. R. (2007). Food web structure in exotic and native mangroves: A Hawaii-Puerto Rico comparison. Oecologia, 153(3), 675–686. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0751-x

Duarte, C. M., Losada, I. J., Hendriks, I. E., Mazarrasa, I., & Marba, N. (2013). The role of coastal plant communitiesforclimatechangemitigationandadaptation. NatureClim.Change, 3(11), 961–968. JOUR. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1970

Duke, N. C., & Wolanski, E. (2001). Muddy coastal waters and depleted mangrove coastlinesDepleted seagrass and coral reefs. Oceanographic Processes of Coral Reefs : Physical and Biological Links in the Great Barrier Reef, 77–91. Retrieved from CCC:000171871200006

Ellison, J. C. (1999). Impacts of sediment burial on mangroves. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 37(8–12), 420–426. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(98)00122-2

Elster, C. (2000). Reasons for reforestation success and failure with three mangrove species in Colombia. ForestEcologyandManagement, 131(1),201–214.http://doi.org/10.1016/S03781127(99)00214-5

Elster, C., & Perdomo, L. (1999). Rooting and vegetative propagation in Laguncularia racemosa. Aquatic Botany, 63(2), 83–93. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3770(98)00122-3

Erwin, K. L. (2009). Wetlands and global climate change: The role of wetland restoration in a changing world. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 17(1), 71–84. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-008-9119-1

Febles-Patrón, J. L., Ló, P. N., & Sampedro, E. B. (2009). Pruebas de reforestación de mangle en una ciénaga costera semiárida de yucatán, México. Madera Bosques, 15(3), 65–86.

Field, C. D. (1998). Rehabilitation of Mangrove Ecosystems An Overview.pdf. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 37(8–12), 383–392. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00106-X

Flores-Verdugo, F. J., Agraz-Hernández, C. M., & Benítez-Pardo, D. (2005). Creación y Restauración de Ecosistemas de Manglar: Principios Básicos. Manejo Costero Integral: El Enfoque Municipal, 1, 1266.

Francisco, A. M., Díaz, M., Romano, M., & Sánchez, F. (2009). DESCRIPCIÓN MORFOANATOMICA DE LOS TIPOS DE GLÁNDULAS FOLIARES EN EL MANGLE BLANCO Laguncularia racemosa L . Gaertn ( f .), 18(3), 237–252.

G.R., M. (1999). Restoration of coastal wetlands in southeastern florida. Wetland Journal, 11(2), 15–24.

Halide, H., Brinkman, R., & Ridd, P. (2004). Designing bamboo wave attenuators for mangrove plantations. Indian Journal of Marine Sciences, 33(3), 220–225.

Howari, F. M., Jordan, B. R., Bouhouche, N., & Wyllie-Echeverria, S. (2009). Field and RemoteSensing Assessment of Mangrove Forests and Seagrass Beds in the Northwestern Part of the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Coastal Research, 251(August 2015), 48–56. http://doi.org/10.2112/07-0867.1

Imbert, D., Rousteau, A., & Scherrer, P. (2000). Ecology of mangrove growth and recovery in the

Lesser Antilles: State of knowledge and basis for restoration projects. Restoration Ecology, 8(3), 230–236. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-100X.2000.80034.x

Impact, E. (1999). Major coastal management and planning techniques.

Kairo, J. G., Dahdouh-Guebas, F., Bosire, J., & Koedam, N. (2001). Restoration and management of mangrove systems - a lesson for and from the East African region. South African Journal of Botany, 67, 383–389. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0254-6299(15)31153-4

Ke, L., & Tam, N. F. Y. (2005). Toxicity and Bioavailability of Heavy Metals and Hydrocarbons in Mangrove Wetlands and Their Remediation, 371–392.

Kent, C. P. S. (1999). A comparison of Riley encased methodology and traditional techniques for planting red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle). Mangroves and Salt Marshes, 3(4), 215–225. article. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009994725133

Kon, K., Kawakubo, N., Aoki, J. I., Tongnunui, P., Hayashizaki, K. I., & Kurokura, H. (2009). Effect of shrimp farming organic waste on food availability for deposit feeder crabs in a mangrove estuary, based on stable isotope analysis. Fisheries Science, 75(3), 715–722. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12562-009-0060-x

Krauss, K. W., & Ball, M. C. (2013). On the halophytic nature of mangroves. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-012-0767-7

Lakshmanan, P., Mathews, M., & Ho, K. K. (1999). Ecophysiological Adaptations and Genetic Variability in Mangroves. Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, 2nd Ed., 1011–1027. http://doi.org/doi:10.1201/9780824746728.ch48

Lee, S. Y. (2004). Relationship between mangrove abundance and tropical prawn production: A re-evaluation. Marine Biology, 145(5), 943–949. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-004-1385-8

Lewis, R. R. (1979). Large scale mangrove restoration on St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Lewis, R. R. (2001). Mangrove Restoration - Costs and Benefits of Successful Ecological Restoration. Mangrove Valuation Workshoop, 4–8. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/forestry/10560-0fe87b898806287615fceb95a76f613cf.pdf

Lewis, R. R. (2005). Ecological engineering for successful management and restoration of mangrove forests. Ecological Engineering, 24(4 SPEC. ISS.), 403–418. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2004.10.003

LOS MANGLARES Y EL TSUNAMI

M. I. Díaz Lezcano, Ingeniero Forestal (Becaria de la Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional) y J.L. de Pedro Sanz, Profesor Titular E.T.S. Ing. de Montes (Madrid). (n.d.).

Lugo, A. (2002). Conserving Latin American and Caribbean mangroves. Madera Y Bosques Número Especial, 8, 5–25.

Martinuzzi, S., Gould, W. A., Lugo, A. E., & Medina, E. (2009). Conversion and recovery of Puerto Rican mangroves: 200 years of change. ForestEcologyandManagement, 257(1), 75–84. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.08.037

McKee, K. L. (1995). Interspecific Variation in Growth, Biomass Partitioning, and Defensive

Characteristics of Neotropical Mangrove Seedlings: Response to Light and Nutrient Availability. American Journal of Botany, 82(3), 299–307. article. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2445575

Moberg, F., & R??nnb??ck, P. (2003). Ecosystem services of the tropical seascape: Interactions, substitutions and restoration. Ocean and Coastal Management, 46(1–2), 27–46. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0964-5691(02)00119-9

Morrisey, D. J., Swales, A., Dittmann, S., Morrison, M. A., Lovelock, C. E., & Beard, C. M. (2010). The ecology and management of temperate mangroves. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 48(322), 43–160. http://doi.org/10.1201/EBK1439821169-c2

Olguin, E. J., Hernandez, M. E., & Sanchez-Galvan, G. (2007). Contaminacion de manglares por hidrocarburos y estrategias de biorremediacion, fitorremediacion y restauracion. Revista Internacional de Contaminacion Ambiental, 23(3), 139–154.

Ong, J. E., & Gong, W. K. (2013). Structure,FunctionandManagementofMangroveEcosystems. ISME Mangrove Educational Book Series No. 2. International Society for Mangrove Ecosystems (ISME), Okinawa, Japan, and International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO), Yokohama, Japan.

Perdomo, L., Ensminger, I.,Espinosa, L.fernanda, Elster,C.,Wallner-kersanach,M., &Schnetter, M.-L. (1999). The Mangrove Ecosystem of the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (Colombia): Observations on Regeneration and Trace Metals in Sediment. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 37(8), 393–403. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00075-2

Primavera, J. H. (2005). Quest for Sustainability. Science, 310(October), 57–59.

Primavera, J. H., & Esteban, J. M. A. (2008). A review of mangrove rehabilitation in the Philippines: Successes, failures and future prospects. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 16(5), 345–358. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-008-9101-y

Reese, R. D. (2010). Restauración Ecológica de los manglares en la costa del Ecuador.

Riley R.W., J., & Kent, C. P. S. (1999). Riley encased methodology: Principles and processes of mangrove habitat creation and restoration. Mangroves and Salt Marshes, 3(4), 207–213. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009963124225

Sousa, W. P., Quek, S. P., & Mitchell, B. J. (2003). Regeneration of Rhizophora mangle in a Caribbean mangrove forest: Interacting effects of canopy disturbance and a stem-boring beetle. Oecologia, 137(3), 436–445. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-003-1350-0

Tong, Y. F., Lee, S. Y., & Morton, B. (2006). The Herbivore Assemblage, Herbivory and Leaf Chemistry of the Mangrove Kandelia obovata in Two Contrasting Forests in Hong Kong. WetlandsEcologyandManagement, 14(1), 39–52. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-005-25650

Tri, N. H., Hong, P. N., Adger, W. N., & Kelly, P. M. (2002). Mangrove Conservation and Restoration for Enhanced Resilience. Managing for Healthy Ecosystems.

Uribe, J., & Urrego, L. E. (2009). Gestión ambiental de los ecosistemas de manglar. Aproximación al caso Colombiano. Gestión Y Ambiente, 12(2), 57–72. Retrieved from

http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/gestion/article/view/14254

Valiela, I., Bowen, J. L., & York, J. K. (2001). Mangrove Forests: One of the World’s Threatened Major Tropical Environments. BioScience, 51(10), 807. http://doi.org/10.1641/00063568(2001)051[0807:MFOOTW]2.0.CO;2

Walters, B. B. (1999). Local Mangrove Planting in the Philippines: Are Fisherfolk and Fishpond Owners Effective Restorationists?*. Manuscript Published in Restoration Ecology, 8(3), 237–246.

Walton, M. E. M. M., Samonte-Tan, G. P. B. B., Primavera, J. H., Edwards-Jones, G., & Le Vay, L. (2006). Are mangroves worth replanting? The direct economic benefits of a communitybased reforestation project. Environmental Conservation, 33(4), 335. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892906003341

Wolanski, E., Mazda, Y., Furukawa, K., Ridd, P., Kitheka, J., Spagnol, S., & Stieglitz, T. (2001). Water circulation in mangroves, and its implications for biodiversity. Oceanographic Processes of Coral Reefs: Physical and Biological Links in the Great Barrier Reef, (Figure 1), 53–76.

World, T., Union, C., Programme, G. M., Studies, E., Place, N., & Bag, L. (2007). Efficacy of Alternative Low-cost Approaches to MangroveRestoration,American Samoa. Estuariesand Coasts, 30(4), 641–651. Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/index/V8804T77H1333U0G.pdf

Worley, K. (2005). Mangroves as an Indicator of Estuarine Conditions in Restoration Areas. Estuarine Indicators, 247–260. http://doi.org/doi:10.1201/9781420038187.ch16

Yao, C. E., Edwards, R., Melana, E. E., Edwards, R., Melana, E. E., & Gonzales, H. I. (2000). Mangrove Management Handbook Options

Appendix D – Other evidences

“Dia del Mangle” Parque La Esperanza, Cataño

Saturday, October 24, 2015

Presentation by Dr. Nancy Villanueva

“

September 6, 2016

Dra. Nancy Villanueva Colón

“Ciclo de Conferencias del Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios del Litoral”

University of Puerto Rico Mayagüez

*1=Poor;2=Regular;3=Good;4=Excelet Evaluation of the conference

Photos of the experimental planting techniques

The first two pictures show the same plot with a 2-week difference. Showing how dynamic is the beach area where the experiment is going on. The third picture shows one of the experimental blocks.

Examples of the work done by students as part of the conference about the results of the experimental planting techniques. Top graph done by an 8th grader. Bottom graph by a 2nd grader.

Evidence of school visited to promote the importance of mangrove forest and to communicate results of the experiments.

Brochure prepared and distributed at Dia de Mangle and at schools