Article

TheEffectsofDepth-RelatedEnvironmentalFactorsonTraitsin Acroporacervicornis RaisedinNurseries

ClaudiaPatriciaRuiz-Diaz 1,* ,CarlosToledo-Hernández 1,*,JuanLuisSánchez-González 1,2 andBrendaBetancourt 3

1 SociedadAmbienteMarino(SAM),SanJuan00931-2158,PuertoRico;juan.sanchez2@upr.edu

2 DepartmentofBiology,UniversityofPuertoRico,SanJuan00931-3360,PuertoRico

3 DepartmentofStatistics,UniversityofFlorida,Gainesville,FL118545,USA;bbetancourt@ufl.edu

* Correspondence:claudiapatriciaruiz@gmail.com(C.P.R.-D.);cgth0918@gmail.com(C.T.-H.)

Citation: Ruiz-Diaz,C.P.; Toledo-Hernández,C.; Sánchez-González,J.L.;Betancourt,B. TheEffectsofDepth-Related EnvironmentalFactorsonTraitsin Acroporacervicornis Raisedin Nurseries. Water 2022, 14,212. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020212

AcademicEditor:KevinB.Strychar

Received:9December2021

Accepted:7January2022

Published:12January2022

Publisher’sNote: MDPIstaysneutral withregardtojurisdictionalclaimsin publishedmapsandinstitutionalaffiliations.

Copyright: ©2022bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

Abstract: Populationsof Acroporacervicornis,oneofthemostimportantreef-buildingcoralsinthe Caribbean,havebeendecliningduetohumanactivitiesandglobalclimatechange.Thishasprompted thedevelopmentofstrategiessuchascoralfarms,aimedatimprovingthelong-termviabilityofthis coralacrossitsgeographicalrange.Thisstudyfocusesoncomprehendinghowseawatertemperature (ST),andlightlevels(LL)affectthesurvivalandgrowthof A.cervicornis fragmentscollectedfrom threereefsinCulebra,PuertoRico.Theseindividualswerefragmentedintothreepiecesofthesimilar sizesandplacedinfarmsat5,8,and12mdepth.Thefragments,STandLLweremonitoredfor 11months.Resultsshowthatfragmentsfromshallowfarmsexhibitsignificantlyhighermortalities whencomparedtotheothertwodepths.Yet,growthatshallowfarmswasnearly24%higherthan attheothertwodepths.Coralsgrewfastestduringwinter,whentemperatureandLLwerelowest, regardlessofthewaterdepth.Fragmentmortalityandgrowthoriginwerealsoinfluencedbyreef origin.Weconcludethatunderthecurrentconditions,shallowfarmsmayofferaslightadvantage overdeeponesprovidedthehighergrowthrateatshallowfarmsandthehighfragmentsurvivalat alldepths.

Keywords: restauration;coralfarm; Acroporacervicornis;seatemperature;lightlevels

1.Introduction

ThedegradationofCaribbeancoralreefshasreachedunprecedentedrates.Itis estimatedthatnearly80%oftheCaribbeanreefshavebeenlost,whiletheremaining20% areseriouslythreatened[1–3].Thescientificcommunity’sconsensusfortheobserved declinespointstowardshuman-relatedactivitiessuchasextensivesedimentationand nitrification[4,5],theunsustainableexploitationofshellfishandfishresources[6];and morerecently,theincreaseinseawatertemperature,oceanacidification,lightlevels,and coraldiseases[7–12].Thesefactors,actingaloneorsynergistically,havediminishedthe naturalcapacityofcoralstorecover[13,14].

Thesignificantreductioninthestaghorncoral Acroporacervicornis initsnaturalhabitat is,perhaps,thebestexampleofthecurrentsituationofreef-buildingcoralsintheCaribbean. Historically, A.cervicornis wasoneofthemostdominantandessentialreef-buildercoral speciesintheCaribbean[15].Itsbroadverticaldistribution,i.e.,froma1to30mdepth[16], highbranchingrates,andimpressiveasexualproliferationduetobranchfragmentation[17] allowedthisspeciestodominatevastareasofthereefscape.Theseso-called“thickets” alsoprovidedthenecessarystructuralcomplexitytosustainahighdiversityoffishes, invertebrates,algae,andmicrobialorganisms[18–20].

However,duringthe1980sand1990s,over90%of A.cervicornis populationsthroughouttheCaribbeanbasindiedtodiseaseoutbreaksandtemperature-associatedbleaching[4,10,12,21].Furthermore,duringthefollowingdecades,theeffectsofcoastal-water

degradation,coupledwiththeincreasedfrequencyofbleachingandoutbreakevents,hamperedthenaturalcapacityof A.cervicornis torecover,placingthesurvivingpopulations injeopardy[3,21].

Toprovidesomeprotectiontothesurvivingpopulations, A.cervicornis hasbeen includedintheUnitedStatesEndangeredSpeciesAct(50CFR223),andtheIUCNRedList ofThreatenedSpecies[22].Eventhoughtheseconservationmeasureshaveprovidedsome levelofprotection,thesealonehavehadlittlesuccessatpreventingfurtherdeclines[23]. Consequently,implementinginterdisciplinarystrategies,suchascoralfarming,thatdirectly impact A.cervicornis populationsacrossitsentirerangeareimperative[17,24].

Coralfarminghasgainedrecognitionasoneoftheprimarystrategiestorestore depletedpopulationsof A.cervicornis [24,25].Presently,over15countriesandislands acrossthewiderCaribbean,includingPuertoRico,havesuccessfullyimplementedcoral gardeningoperations,primarilyusing A.cervicornis fragmentsasthemainspecies[23].The rationalebehindthisstrategyisthatthesurvivalandgrowthofcoralfragmentsduringthe farmingstagearesignificantlyhigherthanthoseofrecentlyfragmentedorrecentlysettled coralsinthewild[15,23].Therefore,maintainingcoralfragmentsinfarmsuntiltheyreach asafesize(>15cminlength)willdramaticallyimprovesurvival,acceleratepopulation recoveryand,consequently,restore A.cervicornis’ ecologicalfunctions[26].

Nearly30yearsafterimplementation[27],coralfarminghasbeenthesubjectofextensiveresearchaddressingadiversearrayoftopics,includingnurserydesigns(e.g.,fixed versusfloatingmidwaterfarmunits)[28,29];theeffectofcoralpropagulesizeonsurvival and growth[30–32];theeffectsofgenotypiclineageonthesurvivalandgrowthofcoral propagules[29–32];andtheimpactsofnutrientsandsedimentloads[30],algalcompetition andpredationoncoralpropagulesurvivalandgrowth,among others[25,29,33] Together, thesestudieshavehelpedprovidebetterpracticesforcoralpopulation enhancementinitiatives.

Nevertheless,aspectssuchastheinfluenceofdepth-relatedseawatertemperature(ST) andLightLevels(LL)ontheperformanceofcoralfragmentsthatarestillinthefarming stage,havebeenoverlooked[32,34].Suchinformationiscentralforcoralfarmpractitioners tounderstandhowcoralfragmentsbeingrearedwillrespondtostochasticfluctuations inSTandLL.Inthisstudy,wesoughttounderstandtheimpactsofseasonalchanges indepth-relatedSTandLLonthesurvivalandgrowthrateof A.cervicornis fragments duringthefarmingstage.Wecollected150 A.cervicornis fragmentsfromthreedistinct reefs(fiftyfragmentsperreef)andfurtherfragmentedthemintothreesimilarsmallpieces (≈15cminlength),whichweresetatthreedepths:5m,8m,and12m.Wethenrecorded thesurvivalandtotallinearextensionatmonthlyintervalsforelevenmonths.Giventhe greatsensitivityof A.cervicornis coralstochangesinSTandLL[6],whichoftencause bleachingstress,andgiventhattheintensityandvariationoftheseenvironmentalfactors mostlikelydeclinewithwaterdepth[35],wehypothesizedthatthermalandlightlevels stressesandsubsequentmortality,shouldincreasefromdeepertomoreshallowwaters. Wealsohypothesizedthatthegrowthrateoffragmentsintheshallowerwaterwillbe higherthanfragmentsfromdeeperwaterandhigherduringthesummermonths,given thehighdependenceof A.cervicornis onlight[36].Wewillconcludebyprovidinguseful recommendationstocoralgardeningpractitionersbasedinourresults.

2.MaterialsandMethods

2.1.StudySite

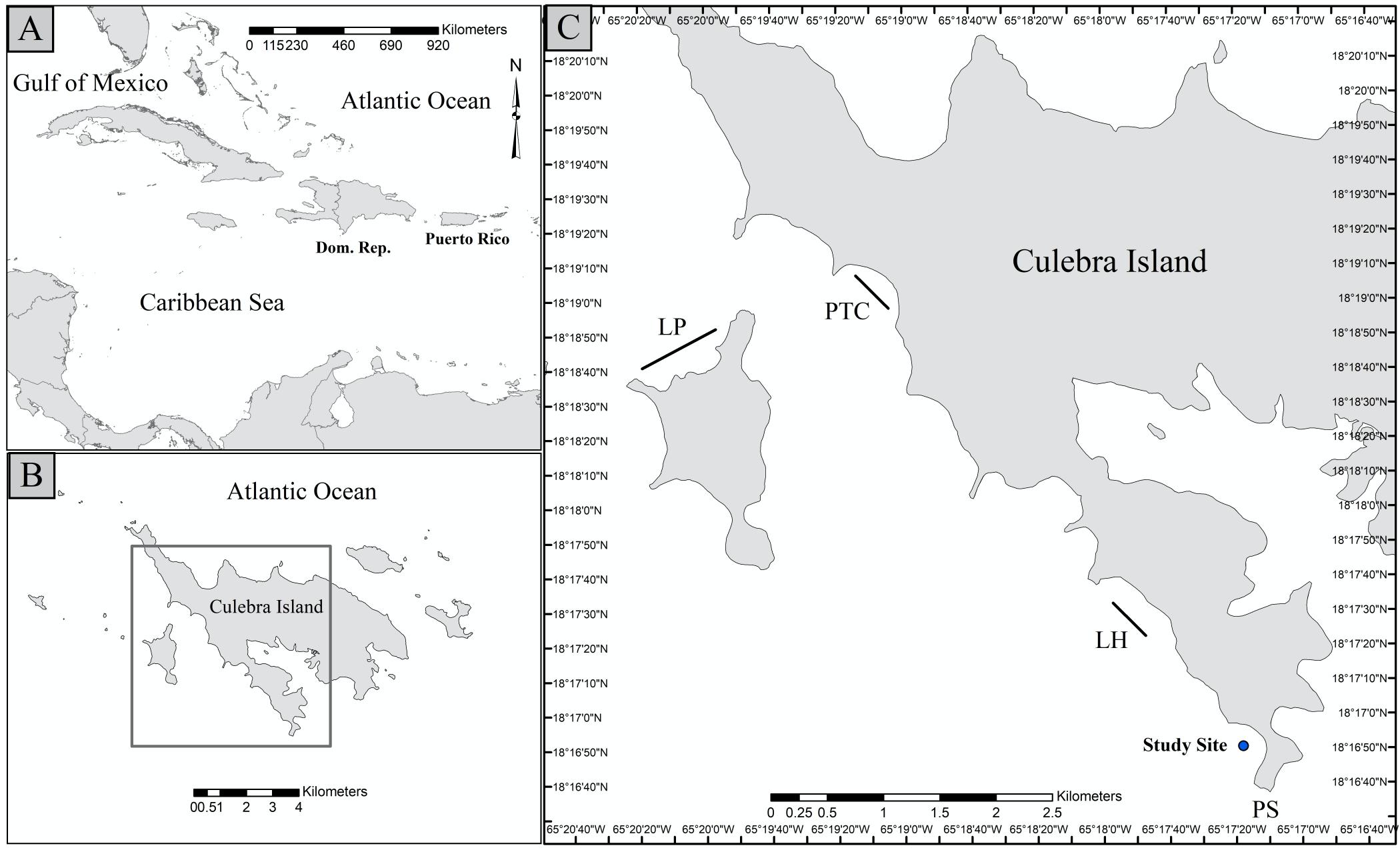

ThestudywasconductedinthePuntaSoldadoReef(PTS),CulebraIsland,Puerto Rico.PTSisasmallbay,approximately1kminwidth,locatedatthesouthern-mostpartof Culebra,Figure 1.PTSisborderedbyaprimarysubtropicaldryforestwithnopermanent humansettlementsandnoagriculturalactivitiesormajorrunoffsflowingintothecoast; consequently,near-shorewatersareclearyear-round.PTShasarelativelyshallowfringing coralreefalongitscoastlineextendingupto60moffthecoast.Seabottomispredominantly sand,gentlyincreasingindeeptowardtheopenwater.Itsreefscapeisdominatedby Porites spp., Orbicella spp., Pseudodiploria spp., Millepora spp., A.cervicornis, andmembersof

the Plexuridae and Gorgonacea families[26].Zonesdeeperthan5–6mfeatureasandy bottomdominatedbytheinvasiveseagrass Halophilastipulacea and,toalesserextent,by macroalgaesuchas Penicilus spp., Udotea spp.,and Gracilaria spp.,amongother.

predominantly sand, gently increasing in deep toward the open water. Its reefscape dominated by Porites spp., Orbicella spp., Pseudodiploria spp., Millepora spp., A. cervicornis, and members of the Plexuridae and Gorgonacea families [26]. Zones deeper than 5–6 m ture a sandy bottom dominated by the invasive seagrass Halophila stipulacea and, to a lesser extent, by macroalgae such as Penicilus spp., Udotea spp., and Gracilaria spp., among other.

Figure1. MapofCulebraillustratingitsgeographiclocationwithrespecttotheCaribbeanRegion (A,B).TheredframeinpanelAindicatesthelocationofCulebraIsland,andsitesoffragment collectionandlocationofthecoralfarms(C).Collectionsites:LuisPeña(LP),LaAhogá (LA),and PuntaTamarindoChico(PTC);farminglocations:PuntaSoldado(PTS).Linesatcollectionsites representthedistancetraveledduringthefragmentcollections.

Figure 1. Map of Culebra illustrating its geographic location with respect to the Caribbean Region (A,B). The red frame in panel A indicates the location of Culebra Island, and sites of fragment lection and location of the coral farms (C). Collection sites: Luis Peña (LP), La Ahogá (LA), Punta Tamarindo Chico (PTC); farming locations: Punta Soldado (PTS). Lines at collection sites resent the distance traveled during the fragment collections.

2.2. Coral Collection and Gardening

2.2.CoralCollectionandGardening

InJune2016,150coralfragments(50fragmentspercollectionsite),fromdifferentA. cervicorniswithnovisiblesignsofdiseasewereusedasdonorcolonies.Thesecolonies werelocatedatthePuntaTamarindoChico(PTC),LaAhogá (LA),andLuisPeña(LP) reefs,Figure 1C.Ingeneral,thethreedonorsitesarereef/hardgroundhabitatswithsimilar coralcover(i.e.,20–30%).LPshowslessrugosityandahigherabundanceofoctocorals thanPTCandLA.Meanwhile,LAismoreexposedtoswellsfromthesouthwestthan PTCandLPandisthelessvisitedbytouristsofthethreedonorsites.Ontheotherhand, PTCreceiveshighertouristvisitsthattheothertwodonorsites,givenitsaccessibilityby landandsea.However,noneofthedonorsiteshavesignificantrunofffloworpermanent humansettlement.Consequently,waterclarityiswellover20myearsaround.Inaddition, thesesitesareatleast1.2kmapartfromeachother,withasandybottomseparatingthem. Therefore,wepresumedthattherewaslowornoasexualrecruitmentamongthesecoral populationsandthereforecoloniesfromeachsitepotentiallyhaddifferentgeneticlineages. Withineachsite,donorcolonieswerefoundatdepthsrangingfrom1to6mandwere morethan15maparttoincreasethelikelihoodoffindinggeneticallydistinctindividuals. Aftercollection,fragmentswerebroughttothevesselandweresubmergedinthree-57L plasticbasketsfilledwithseawater.Tominimizedtransportationstress,fragmentswere completelysubmergedinseawaterandshadedfromthesununtilreachingtheexperimental sitesi.e.,PTS.OnceinPTSeverycolonywasfurtherfragmentedintothreepieces,each of~15cminlength(hereafternamed“clonalfragments”),taggedwithauniquenumber andphotographed.Taggedclonalfragmentsfromthesamedonorcolonyweredeployed tocoralfarmsinstalledatthreedifferentwaterdepths:5m(shallow),8m(medium),and 12m(deep)Figure 2.Coralfarmswereconstructedbyhammeringsixmetalrods,each 2 × 0.02m,tothesandybottom,formingafive-pointedstarwithonecentralrodandthe remainingfiverods(hereafterthe“peripheralrods”)set2mapartfromthecentralrod,

In June 2016, 150 coral fragments (50 fragments per collection site), from different cervicornis with no visible signs of disease were used as donor colonies. These colonies were located at the Punta Tamarindo Chico (PTC), La Ahogá (LA), and Luis Peña reefs, Figure 1C. In general, the three donor sites are reef/hard ground habitats with ilar coral cover (i.e., 20–30%). LP shows less rugosity and a higher abundance of octocorals than PTC and LA. Meanwhile, LA is more exposed to swells from the southwest than and LP and is the less visited by tourists of the three donor sites. On the other hand, receives higher tourist visits that the other two donor sites, given its accessibility by and sea. However, none of the donor sites have significant runoff flow or permanent man settlement. Consequently, water clarity is well over 20 m years around. In addition, these sites are at least 1.2 km apart from each other, with a sandy bottom separating them. Therefore, we presumed that there was low or no asexual recruitment among these coral populations and therefore colonies from each site potentially had different genetic ages. Within each site, donor colonies were found at depths ranging from 1 to 6 m were more than 15 m apart to increase the likelihood of finding genetically distinct individuals. After collection, fragments were brought to the vessel and were submerged three-57 L plastic baskets filled with seawater. To minimized transportation stress, fragments were completely submerged in seawater and shaded from the sun until reaching the experimental sites i.e., PTS. Once in PTS every colony was further fragmented three pieces, each of ~15 cm in length (hereafter named “clonal fragments”), tagged with a unique number and photographed. Tagged clonal fragments from the same donor ony were deployed to coral farms installed at three different water depths: 5 m (shallow), 8 m (medium), and 12 m (deep) Figure 2. Coral farms were constructed by hammering

Figure 3A–C.Theperipheralrodswereconnectedtothecentralrodsbytwosetsoffishing line,oneat1.5mabovethesandybottomandtheotherat1.0m.Intotal,ninefive-pointed starcoralfarmswereinstalled,threeperdepth.Coralfarmsateachdepthwereset20–30m apartfromeachother.Atotalof50fragmentsperfarmwereattachedtothefishinglines foragrandtotalof450fragments.Noticethateverydonorcolonyhaveaclonefragmentat eachdepthandthatnomorethanoneclonalfragmentfromthesamedonorcolonywas placedatthesamedepth,Figure 2

metal rods, each 2 × 0.02 m, to the sandy bottom, forming a five-pointed star with one central rod and the remaining five rods (hereafter the “peripheral rods”) set 2 m apart from the central rod, Figure 3A–C. The peripheral rods were connected to the central rods by two sets of fishing line, one at 1.5 m above the sandy bottom and the other at 1.0 m. In total, nine five-pointed star coral farms were installed, three per depth. Coral farms at each depth were set 20–30 m apart from each other. A total of 50 fragments per farm were attached to the fishing lines for a grand total of 450 fragments. Notice that every donor colony have a clone fragment at each depth and that no more than one clonal fragment from the same donor colony was placed at the same depth, Figure 2.

metal rods, each 2 × 0.02 m, to the sandy bottom, forming a five-pointed star with one central rod and the remaining five rods (hereafter the “peripheral rods”) set 2 m apart from the central rod, Figure 3A–C. The peripheral rods were connected to the central rods by two sets of fishing line, one at 1.5 m above the sandy bottom and the other at 1.0 m. In total, nine five-pointed star coral farms were installed, three per depth. Coral farms at each depth were set 20–30 m apart from each other. A total of 50 fragments per farm were attached to the fishing lines for a grand total of 450 fragments. Notice that every donor colony have a clone fragment at each depth and that no more than one clonal fragment from the same donor colony was placed at the same depth, Figure 2.

Figure2. Diagramshowingtheexperimentaldesignprocedures.Followingcolonycollectionfrom LuisPeña(LP),LaAhogá (LA),andPuntaTamarindoChico(PTC),eachdonorcolonywasfurther dividedintothreefragmentsofsimilarlength(clonefragment),taggedwithauniquenumber,and setatacoralfarmat5,8,and12mdepthsinPuntaSoldado(PTS)soasonlyeachdonorcoralhave onlyonerepresentativeateachdepth.

Figure 2. Diagram showing the experimental design procedures. Following colony collection from Luis Peña (LP), La Ahogá (LA), and Punta Tamarindo Chico (PTC), each donor colony was further divided into three fragments of similar length (clone fragment), tagged with a unique number, and set at a coral farm at 5, 8, and 12 m depths in Punta Soldado (PTS) so as only each donor coral have only one representative at each depth.

Figure 2. Diagram showing the experimental design procedures. Following colony collection from Luis Peña (LP), La Ahogá (LA), and Punta Tamarindo Chico (PTC), each donor colony was further divided into three fragments of similar length (clone ), tagged and set at and 12 m depths so as only each donor coral have only one representative at each depth

Figure3. InstallationandMaintenanceoffarms.Images(A–C)showtheinstallationprocedures fromfarmsat5,8and12mdepthsduringJune2016.Images(D–F);showmaintenanceprocedures fromfarmsat5,8and12mdepthsduringApril2017.

3. Installation and Maintenance of farms. Images (A–C) show the installation procedures from farms

F

maintenance procedures from

2.3.EnvironmentalMeasurements

Seawatertemperature(ST)andtherelativeLightLevels(LL)weremeasuredby deployingaHoboPendanttemperature/lightdataloggers64k-UA-002-64(OnsetCompany,

Tokyo,Japan)perdepth.Eachdevicewassecuredtothecentralrodofacoralfarms followingthemanufactureinstructions.TheSTandLLdeviceswereprogrammedto recordonedatumevery15min.Temperatureswerelefttorecordfor30–40days,whereas LLwasrecordedonlythefirst10daysafterbeendeployed,asalgaeandsedimentscould interferedwiththedetectionoflightafterthe10-daysperiod.Thedeviceswereretrieved monthlyandreplacedwithnewones.Statisticaldifferencesbetweenmonth/depths (independentvariables)andSTandLL(dependentvariables)wereexploredusingtwo, two-wayANOVA.

2.4.SurvivalAnalysis

TwoKaplan–Meiersurvivaltests(KM)withalog-rankanalysiswereperformedto comparethesurvivalcurvesamong(1)clonalfragmentsplacedatdifferentdepths,i.e., at5,8,and12m,and(2)fragmentscollectedfromPTC,LP,andLA.Theseanalyseswere conductedunderthenullhypothesisoftherebeingnodifferencesinsurvivalamongthe depthsandsitesoffragmentcollections.Forthedepth-comparisonanalysis,samplesfrom thesamewaterdepthwerepooledasagroupregardlessoftheircollectionorigin.Similarly, todetectpotentialdifferencesinfragmentmortalitybasedonthesiteoffragmentcollection, samplesfromthesamesiteofcollectionweregrouped,regardlessofthedepthatwhich theywereplaced.ThetimelapsefortheseanalysesranfromJuly2016toJune2017.To estimatetheKMsurvivaltest,wefirstestimatethedeathprobabilityataspecificmonth. Thatis,thetotalnumberofdeadindividualsrecordedduringamortalityeventatagiven month,dividedbythenumberofindividualssurvivingduringthatmortalityevent.We estimatedtheprobabilityofsurvivalduringthatspecificmonthbysubtractingthedeath probabilityduringthatmonthfromone.Finally,themonthlysurvivalprobabilitywas estimatedbymultiplyingthesurvivalprobability,calculatedforeachspecificmortality eventuntilthattime.Thesestatisticalanalyseswerecarriedoutusingthesurvivalpackage version2.38inR[37].

2.5.MonthlyGrowthRates

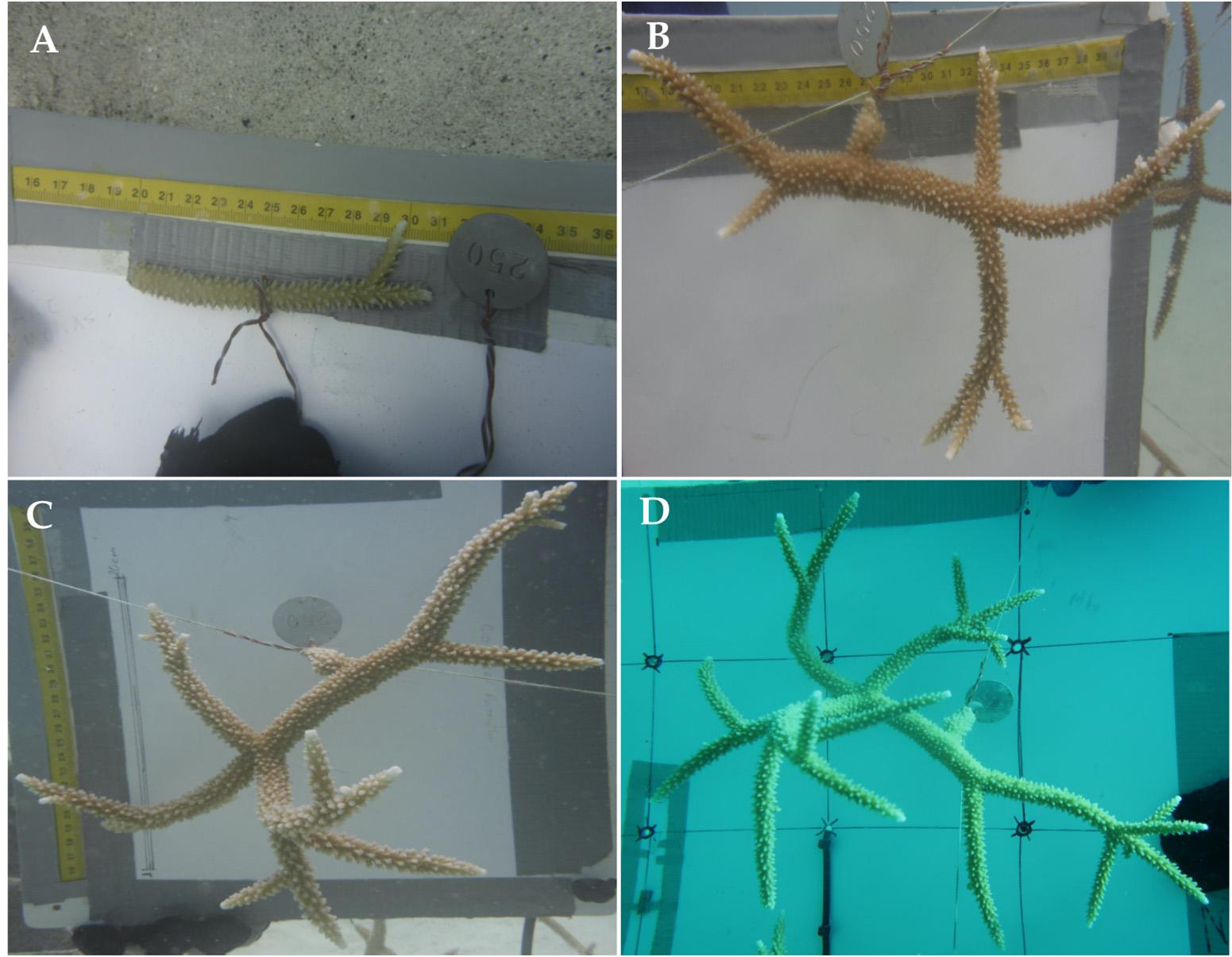

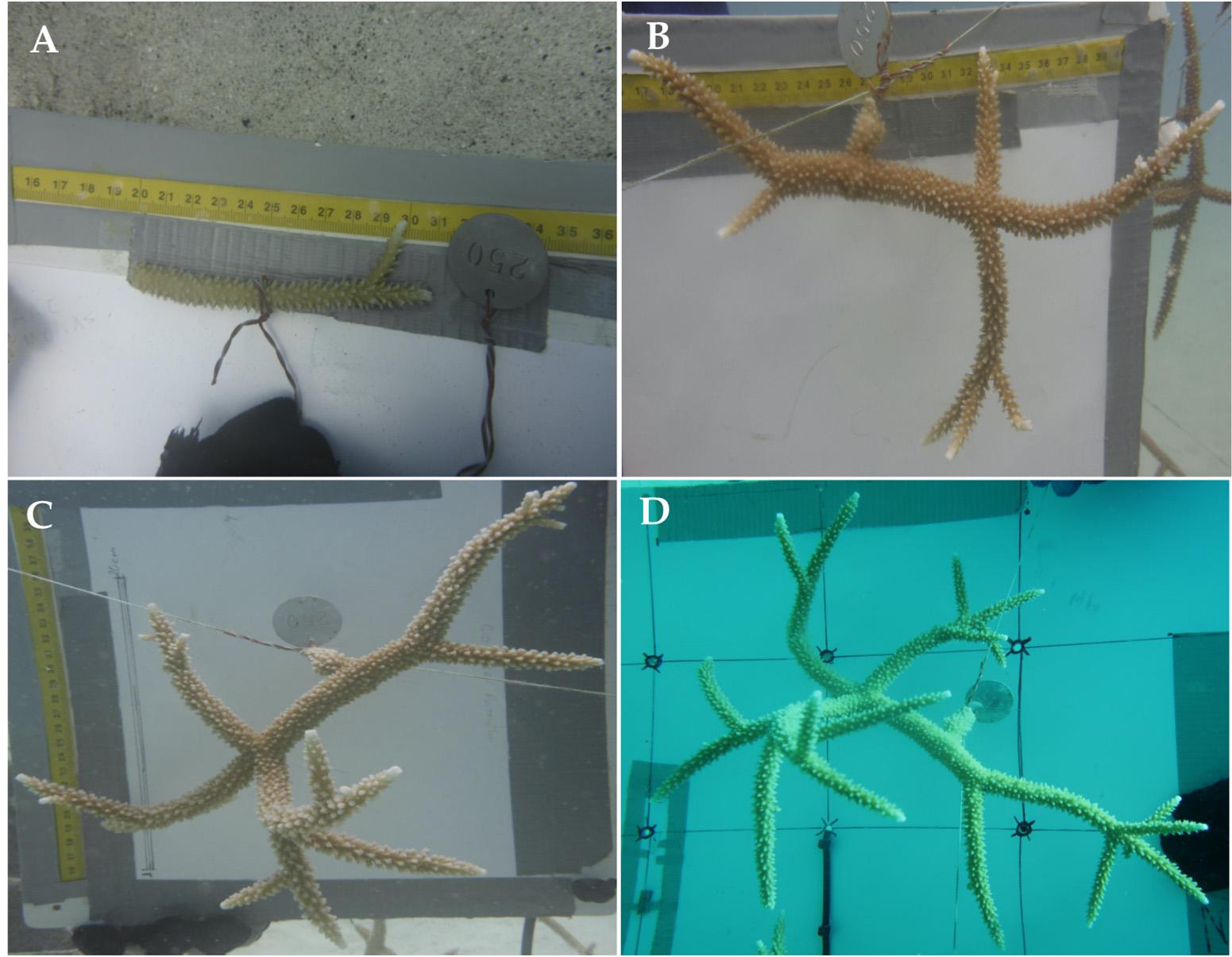

AtmonthlyintervalsfromJuly2016toJune2017,coralfarmswerevisitedtoremove foulingorganismssuchasfilamentousalgaethatcouldpotentiallyharmtheclonalfragments,Figure 3D–F.Additionally,insituphotographs(scale-by-site)weretakentoestimate totallengthextension(TL)tothenearestcm,usingCoralPointCountsoftwarewithExcel extensions(CPCe)[38],Figure 4.Coralfragmentswerephotographedfromdifferentangles toensurethatlengthextensionofbranchesfromeachclonefragmentwerefullyappreciated. ThemonthlyTLestimateswerecalculatedbysummingallbrancheswhoselengthwas greaterthan0.5cm.TheTLswerethentransformedtothemonthlycoralgrowthrate (MGR)bysubtractingthemostrecentTLmeasurementfromthepreviousTLmeasurement, dividedbythenumberofdaysbetweenmonitoringperiods.Thesubsequentanalysiswas performedonlywithcoralindividualswhosethreeclonalfragmentsremainedalivebythe endofthestudy,i.e.,135coralindividualsintotal.

Figure 4. Clone fragment number 250 followed through time. Image of clone fragment 250 before hanged on farm in June 2016 (A), and image showing the same coral in December 2016 (B), March 2017 (C) and June 2017 (D).

Figure4. Clonefragmentnumber250followedthroughtime.Imageofclonefragment250before hangedonfarminJune2016(A),andimageshowingthesamecoralinDecember2016(B),March 2017(C)andJune2017(D).

2.6.

Coral Growth Analysis

2.6.CoralGrowthAnalysis

For the implementation of the statistical model, the Month variable was treated as a numeric variable, which reflects the assumption that the relationship between the growth rate and the Month is linear. This choice is based on exploring the growth profiles of the clonal fragments across depths, collection sites and months.

Fortheimplementationofthestatisticalmodel,theMonthvariablewastreatedasa numericvariable,whichreflectstheassumptionthattherelationshipbetweenthegrowth rateandtheMonthislinear.Thischoiceisbasedonexploringthegrowthprofilesofthe clonalfragmentsacrossdepths,collectionsitesandmonths.

Toevaluatetheeffectsofdepth-relatedvariabilityinSTandLL,andthecollection sitesonthegrowthrateofclonalfragmentsacrosstime,wecreatedalinearmixedmodel (LMM)witharandomeffectanalysis.Themodelincludedthefixedeffectsof(1)the categoricalvariablesofdepthsandcollectionsite,eachwiththreelevels,i.e.,shallow, medium,anddeep,andPTC,LP,andLA,respectively;(2)thecontinuousvariablesof STandLL;(3)Months;(4)first-orderinteractionsbetweenallvariablesexceptMonths; and(5)second-orderinteractionsofSTandLLwithdepthandcollectionsite,respectively. ThemodelalsoincludesrandominterceptsandrandomslopesassociatedwiththeMonth variableforeachcoraltoconsiderpossibleMGRvariabilityonaverageandovertime.For thisanalysis,westandardizedallnumericpredictorsi.e.,ST,LL,Months,andtheresponse variablei.e.,MGRbysubtractingtheoverallmeandividedbytherespectivestandard deviation.Thefinalmodelstructurewasspecifiedthroughbackwardstepwiseselection, startingwiththesaturatedmodel’srandomcomponents,andfollowedbythefixedeffects, excludingtermsthatwerenotsignificant,inahierarchicalfashion.Therelevantmodel componentswereselectedbyperforming χ2 teststocomparenestedmodelsthatonly differinthetermofinterest.Thisimplieschoosingthemoresaturatedmodelonlyif thereductionintheresidualsumofsquareswasstatisticallysignificantcomparedtothe simplermodel.ThestatisticalanalysesinthisstudywereperformedusingthelmerTest packageinR[39,40].

To evaluate the effects of depth-related variability in ST and LL, and the collection sites on the growth rate of clonal fragments across time, we created a linear mixed model (LMM) with a random effect analysis. The model included the fixed effects of (1) the categorical variables of depths and collection site, each with three levels, i.e., shallow, medium, and deep, and PTC, LP, and LA, respectively; (2) the continuous variables of ST and LL; (3) Months; (4) first-order interactions between all variables except Months; and (5) second-order interactions of ST and LL with depth and collection site, respectively. The model also includes random intercepts and random slopes associated with the Month variable for each coral to consider possible MGR variability on average and over time. For this analysis, we standardized all numeric predictors i.e., ST, LL, Months, and the response variable i.e., MGR by subtracting the overall mean divided by the respective standard deviation. The final model structure was specified through backward stepwise selection, starting with the saturated model’s random components, and followed by the fixed effects, excluding terms that were not significant, in a hierarchical fashion. The relevant model components were selected by performing �� tests to compare nested models that only differ in the term of interest. This implies choosing the more saturated model only if the reduction in the residual sum of squares was statistically significant compared to the simpler model. The statistical analyses in this study were performed using the lmerTest package in R [39,40].

3.Results

3.1.EnvironmentalMeasurements

3.1.1.Temperature

Seawatertemperatureacrossalldepthsshowedasimilarpatternofvariationthroughoutthestudyperiod,Figure 5A.Atalldepths,thehighestaveragetemperaturevalues wererecordedfromJulytoSeptember2016(summer),thendecreasedfromOctoberto December2016(fall),reachingthelowestvaluesfromJanuarytoMarch2017(winter),and risingagainfromApriltoJune2017spring:Figure 5A.Nevertheless,themonthlyaverage STwasconsistentlyhigherandmorevariableata5mdepththanat8and12mdepths.The highestrecordedvalue(31.47 ◦C)atthisdepthoccurredinSeptember2016.Meanwhile, thelowestmonthlyaverageSTvalueswereconsistentlyrecordedata12mdepth,with thelowestvalues(25.7 ◦C)occurringinMarchof2017,Figure 5A.Intermediatemonthly averageSTvalueswererecordedatalldepthsinthefallandspringmonths,thevalues

ber to December 2016 (fall), reaching the lo west values from January to March 2017 (winter), and rising again from April to June 2017 spring: Figure 5A. Nevertheless, the monthly average ST was consistently higher and more variable at a 5 m depth than at 8 and 12 m depths. The highest recorded value (31.47 °C) at this depth occurred in September 2016. Meanwhile, the lowest monthly average ST values were consistently recorded at a 12 m depth, with the lowest values (25.7 °C) occurring in March of 2017, Figure 5A. Intermediate monthly average ST values were recorded at all depths in the fall and spring months, the values at 8 m depth during spring 2017 being slightly higher than at the rest of the other depths. These differences were statistically significant, Table 1.

at8mdepthduringspring2017beingslightlyhigherthanattherestoftheotherdepths. Thesedifferenceswerestatisticallysignificant,Table 1

Figure 5. Comparison of temperatures (A), and (B) light levels (measured during the first ten days of every month), from farms set at shallow (5 m, in red), medium (8, in green) and deep (12 m, in blue) depths. Bars represents monthly average and whiskers standard error.

Figure5. Comparisonoftemperatures(A),and(B)lightlevels(measuredduringthefirsttendaysof everymonth),fromfarmssetatshallow(5m,inred),medium(8,ingreen)anddeep(12m,inblue) depths.Barsrepresentsmonthlyaverageandwhiskersstandarderror.

Table1. Two-wayANOVAsresultsbetweenSeawaterTemperature(ST)andLightLevel(LL).**and ***representlevelsofsignificance.

3.1.2.LightLevels

LLshowedatrendsimilartothatoftemperaturewithLLbeingconsistentlyhigher at5mdepththanat8and12mdepth.TheLLata12mdepthwasthelowestandleast variablewhencomparedtotheotherdepths,Figure 5B.However,eachdepthexhibited differentLLpatternsacrosstime.At5mdepth,forinstance,thehighestLLvalueswere observedinJuly2016,thendecreasedlinearly,reachinglowestvaluesinNovember2016

andthereafter,increasingagainFigure 5B.Bycontrast,themonthlyaveragesofLLat8and 12mdepthsexhibitedslightlydifferentpatterns.At8mdepth,LLexhibiteddiscretebut continuedincrementsfromJuly–Septemberandthendroppedtoitslowestrecordedvalue inOctober.Thereafter,LLsteadilyincreasedreachingitshighestvalueinFebruary.LL droppedagainoverthefollowingtwomonths,thenincreasingonceagainduringMay. MeanmonthlyLLat12malsoshowedsimilartrendasthatof8m,althoughslightly droppedduringAugust,Figure 5B.Thesedifferenceswerestatisticallydifferent,Table 1

3.1.3.Survival

Overall,426outofthe450fragmentssurvivedduringthestudyperiod.Survival variedacrosstimeanddepths.Ofthe24recordedtotalfragmentfatalities,eightoccurred duringthefirst30daysofthestudy(i.e.,fromJunetoJuly2016),threeintheshallow nurseries,fouratmediumdepth,andoneinthedeepernurseries.Thiswastheonlytime intervalacrossthestudyperiodexhibitingmortalitiesofclonalfragmentsatallthreedepths. Overall,fragmentmortalityincreasedfromdeeptoshallowerfarms,withmortalitiesin shallowfarmsdoublethemortalitiesrecordedatmedium-depthfarmsandquadruplethe mortalitiesindeeperfarms,Figure 6A.Likewise,mortalitiesinthemedium-depthfarms doubledthoseofthedeepestfarms.Thesedifferencesinsurvivalbetweendepthswere statisticallysignificant(χ2 =8.2,df=2,and p-value=0.0,Figure 6A).Mortalityalsovaried bycollectionsite.Fifteenofthe24recordedmortalitieswerefragmentsfromPTC.Ofthe remainingninemortalities,fourwerefragmentscollectedatLPandfivefromLA.These differenceswerealsostatisticallysignificant(χ2 =10.2,df=2; p-value=0.006,Figure 6B).

of surviving of

by

Figure6. Probabilityofsurvivingof Acroporacervicornis fragmentsacrossthe11-monthstudyperiod bydepths(A)andsiteofcollection(B):LuisPeña(LP),LaAhogá (LA)andPuntaTamarindo Chico(PTC).

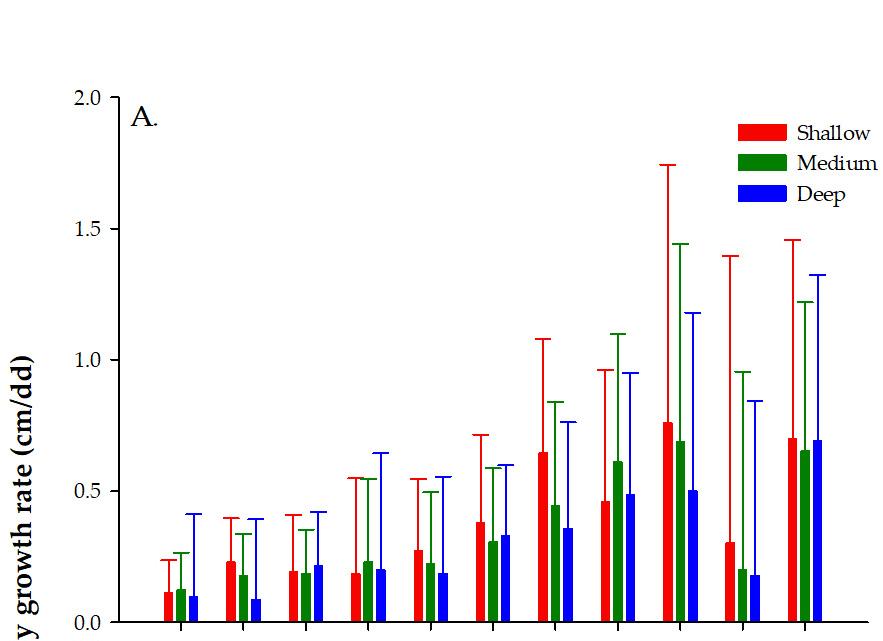

3.2. Monthly Growth Rate (MGR) of Colonies All the fixed-effect terms from our LMM were significant at 5% (Table 2). However, the most relevant results can be summarized as follows: (1) The model shows a strong proportional inverse effect between ST and LL and the average MGR from clonal fragments at all depths. That is, when ST and LL decreased, MGR increased. (2) The model also showed that the mean MGR from fragments at all depths correlated positively with the month, as the mean coral fragments’ monthly growth was always above zero. This suggests

3.2.MonthlyGrowthRate(MGR)ofColonies

Allthefixed-effecttermsfromourLMMweresignificantat5%(Table 2).However, themostrelevantresultscanbesummarizedasfollows:(1)Themodelshowsastrong proportionalinverseeffectbetweenSTandLLandtheaverageMGRfromclonalfragments atalldepths.Thatis,whenSTandLLdecreased,MGRincreased.(2)Themodelalso showedthatthemeanMGRfromfragmentsatalldepthscorrelatedpositivelywiththe month,asthemeancoralfragments’monthlygrowthwasalwaysabovezero.Thissuggests thattherewerenomajorunexpectedfragmentations,i.e.,stronggroundswells.Moreover, theobservednegativeestimateatmediumanddeep-waterfarmssuggeststhatcoralsin shallow-waterfarmshavehigheraverageMGRsthanattheothertwofarmdepths,Table 2. However,MGRvariedacrossmonths,withhighermeanMGRsfromNovember2016to March(thecoldestmonthsofthestudyperiod)andlowerMGRsfromJulytoOctober2016 andApriltoJune2017,Figure 7A.(3)ThemodelalsoindicatesthatthemeanMGRsvaried bycollectionsite(“Locally”,Table 2).HigherMGRsfromclonalfragmentscollectedat PTCwasobservedwhencomparedtotheMGRsfromfragmentscollectedatLPandLA. Thisresultwasfurtherconfirmedaftergroupingcoloniesbythesiteofcollection,farm depth,andwhethertheMGRofeachfragmentwasaboveorbelowtheoverallmeanMGR calculatedbyeachdepth(χ2 =8.4851,df=2, N =61, p <0.05),Figure 7B.

Table2. LinearMixedModel(LMM)resultsfitbymaximumlikelihood t-testsusingSatterthwaite. **and***representlevelofsignificance.

LocalityPTC0.1853.3240.001** LocalityLA0.142.7340.006**

Finally,themodelrevealedthatclonalfragments’MGR(i.e.,themonthlygrowth rateofthethreefragmentsfromanindividualcoral,setatdifferentdepths)variedacross months,witha χ2 = 120, p value = 2 × 10 14 (Randomeffects).Inotherwords,these resultsshowedtherewerefragmentsfromthesamedonorcolonywithaboveaverage MGRsatalldepths.Similarly,therewerefragmentsfromthesamedonorcolonyshowing belowaverageMGRsatalldepths,andfragmentsthatshowedaboveaverageMGRsin onedepthandbelowaverageinotherdepths.

Figure7. Comparisonofthemonthlygrowthrateof Acroporacervicornis fragmentsbyfarmdepth (A)andsiteoffragmentcollection(B).PuntaTamarindoChico(PTC),LuisPeña(LP),andLaAhogá (LA). N =135fragmentindividualsperdepth/site.Barsrepresentsmonthlyaverageandwhiskers standarderror.

Figure 7. Comparison of the monthly growth rate of Acropora cervicornis fragments by farm depth (A) and site of fragment collection (B). Punta Tamarindo Chico (PTC), Luis Peña (LP), and La Ahogá (LA). N = 135 fragment individuals per depth/site. Bars represents monthly average and whiskers standard error.

4.Discussion

4. Discussion

Coralvulnerabilitytocommonstressorssuchastemperatureandlightlevelsare expectedtoincreaseundercurrentclimatechangescenarios.Onestrategytoreducethe impactsoftheseclimate-change-relatedfactorsistomigratetoareaswithmorefavorable environmentalconditions.Giventhattheseawatertemperatureisoftenlowerindeeper watersandlightlevelsdeclineswithdepth,thestressinducedbythesefactorsshouldsimilarlydecline.Infact,thispatternhasbeenextensivelyreportedinthescientificliterature, butwithsomecontroversy[41–43].

Coralfarmingoperationsarenotimmunetotheseclimatechangeissuesandmoving coralfarmsfromshallowtodeeperwatermaybeafeasiblestrategyforloweringtheriskof

Coral vulnerability to common stressors such as temperature and light levels are expected to increase under current climate change scenarios. One strategy to reduce the impacts of these climate-change-related factors is to migrate to areas with more favorable environmental conditions. Given that the seawater temperature is often lower in deeper waters and light levels declines with depth, the stress induced by these factors should similarly decline. In fact, this pattern has been extensively reported in the scientific literature, but with some controversy [41–43].

losingfragmentstounforeseenhightemperatureandlightevents.However,thisstrategy hasnotbeenthoroughlystudiedbasedonfragmentsmortality,growth,andcostsacross timeTherefore,thisstudyassessedtheeffectsofwater-depth-relatedtemperatureandlight levelsonthegrowthandmortalityofcoralfragmentscollectedfromdifferentsitesand furthercomparedtheseresultsacrosstime.

Providedthatthemaingoalofcoralfarmoperationsistooptimizethesurvivaland swiftgrowthofcoral,wewilldiscussthreemajorfindingsthatcouldimprovecoralfarming operations.(1)Theprevailingwatertemperatureandlightlevelsacrossdepthandtime, havecontrastingimpactsonthemortalityandgrowthofcoralfragments.(2)Thecollection siteplaysanimportantroleinthesurvivalandgrowthratesofcoralfragmentsand(3)the magnitudebywhichthesefactorsaffectthemortalityandgrowthratearecolonyspecific.

OurstudyshowedthatthefluctuationinSTandLLacrosstimeanddepthseem tohavenegligibleeffectsonfragmentmortality,giventheoveralllowmortality(≈5%) recordedduringtheelevenmonthsofthemonitoringperiod.

Mortalityinthisstudy,didnotfollowaclearseasonalpattern,intheabsenceof noticeableenvironmentalstress.However,severalconclusionsshouldbehighlighted.First, survivalwaslowerduringthefirst30days,i.e.,JunetoJuly2016,asone-thirdofthetotal mortalities(8/24)wererecordedduringthesedays.Akintoapreviousstudy[25],early mortalitymaybetheresultfromstresscausedbyfragmentmanipulation.Alternatively, UV/bluelightshocksmayalsoproducesomemortality,especiallytocoralscollectedat deeperareasanddeployedinshallowerfarms.Nonetheless,indifferentperiodsafter theconclusionofthisstudy,wehaveoutplantedover400fragmentsontoshallowreefs (e.g.,2to5mdepth),allofwhichhavebeenharvestedfromfarmsat12mdepthandthe survivalestimatesarenearly98%sevenmonthsafterbeingoutplanted.Therefore,further researchmustbeconductedtofullyunderstandeffectofthedifferentformsofradiationon coralfragments.

Secondly,mortalitywashigherinfarmssetatshallowdepthsanddecreasedindeeper farms.Nearly59%ofdeathsoccurredintheshallowerfarms.Movingintodeeperwater, mortalitydecreasedfrom30%infarmssetatan8mdepthto12.5%mortalityinthedeeper farms.Theseresultssuggestthatfragmentsinthedeeperfarmsmayhavesufferedless stressfulconditionsthanfragmentssetintheshallowerfarms.Nonetheless,mortality atshallowwaterwasstillwellabovethebenchmarksproposedby[44].Otherstudies havereportedresultssimilartoours,arguingthatcoralsindeeperzoneswouldbebetter protectedfromdamagingwater-temperatureandlight-intensitylevels,therebyimproving theirsurvivalwithrespecttocoralsinshallowerzones[45–47].Thirdly,mortalitywas higherinfragmentscollectedatPTCwhencomparedtofragmentscollectedatLPand LA,asnearlyfiveofeveryeightdeadfragmentswerecollectedatPTC.Incontrast,oneof eacheightdeadfragmentswascollectedatLPorLA.Theseresultsprovidecircumstantial evidenceregardingpossibleintrinsicanduniquefactorswithineachsampledpopulation, e.g.,geneticandzooxanthellaecomposition.WherebycoralfragmentsfromPTCshow lowerstresstolerancethancoralfragmentsfromLAandLPbuthavehighgrowingcapacity. Thesetrendswherecoralspeciesexhibithigherallocationofresourcesintogrowthbut lessintoimmunecompetence,makingthemmoresusceptibletoperishfromdiseases orabruptenvironmentalchanges,havebeenextensivelydocumented[48].However, intraspecificlevelhasneverbeendocumented.Therefore,furthergeneticstudiesusing coralindividualsfromdifferentpopulationsareneededtocomprehendthepotentialeffects ofgeneticvariabilityandstresstolerance.

Asinpreviousstudies, A.cervicornis exhibitsanimpressivegrowthcapacity.Fragmentsgrewnearlyseventimestheiroriginalsizeintheelevenmonthsofthestudy,(i.e., averagegrowthratesrangingfrom0.02to0.20cmperday),withsomecoloniesgrowing 30timestheiroriginalsize.Growthratesreportedhereareamongthehighest,ifnotthe highestever,reportedfor A.cervicornis fragmentsrearedinsuspendedfarms.Forinstance, ouraveragedailygrowthwasover2.3timeshigherthanthosereportedbyLirmanetal.[25]

fromtheDominicanRepublicandbyGeorgenetal.[23]inFlorida.Andbetween3to 7timeshigherthanthosereportedinPuertoRico[31],Florida[15,49]andJamaica[50].

Thesiteoffragmentcollectionseentohavegreatinfluenceoncoralfragmentgrowth. Overall,meanMGRsfromfragmentscollectedatPTCweresignificantlyhigher(e.g., 0.371cm/day)thanthosefromfragmentscollectedatLPandLA(0.354cm/dayand 0.273cm/dayrespectively),Figure 6.Thispatternwasobservedatalldepths,suggesting thatcoralfromPTChavegreatermetaboliccapacitytogrowatthreedifferentdepthsthat coralfragmentsfromLAandLP.Thecontrarycouldbeinterpretedwithfragmentscollected atLA,asfragmentscollectedfromthissiteshowedthelowestmeanMGRs.Overall,these resultssuggestthatsurvivingcoralsfromPTChavehighertolerancetochangingenvironmentalconditionsthancoralfromLAandLP.Thedifferencesinacclimatizationcapacity maybelikelylinkedtodistinctgeneticheritagesamongthedonor populations[49,51] and orbyenvironmentalmemoryoriginatedthroughepigeneticmodifications[52].

Growthwasalsoinfluencedbydepth.Thedeeperthefragmentswereplaced,the slowertheirgrowthrateswere.Infact,growthwasnearly24%higherinfragments fromshallowerfarmswhencomparedtofragmentsfromdeeperfarms.Theseresults coincidedwithpreviousstudiesthatalsoreporteddifferencesingrowthbasedonwater depth.Forinstance,BakerandWeber[53],workingwith Orbicellaannularis [54],observed thatlinearandmassgrowthvarieswithdepth,withcoloniesindeeperareasshowing reducedcalcificationandthereby,lessgrowthwhencomparedtothoseinshallowareas. Highsmith[55]alsorecordedadecreaseinthelinearandmassgrowthof Faviapallida, Goniastrearetiformis,and Poriteslutea coralswithawaterdepthincreaseinthePacific. Huston[56]reachedsimilarconclusionsinsevenreef-buildingspecies(Agariciaagaricites, Orbicellaannularis, Montastraeacavernosa,Poritesporites,P.astreoides, Colpophyllianatans,and Siderastreasiderea)inDiscoveryBay,Jamaica.Furthermore,adecreaseingrowthrateswith increasesinwaterdepthhasalsobeendetectedongorgoniancorals[57]andalgae[58], amongotherphotosyntheticorganisms.Therefore,anincreaseindepth(andconsequently adecreaseinlightavailability)willcauseadecreaseinphotosynthesisandgrowthratesin mostzooxanthellatecoralsduetoareductionintheresourcesallocatedtogrowth[56,59]. However,seecontrastingresultsforexamplefromTorresetal.[60]where A.cervicornis coloniesweretransplantedtodeeperzonesgrewmoreapparentlyduetoareductioninUV radiationcausingasignificantreductionintheproductionofUV-absorbingcompounds andconsequentlyahigheravailabilityofresourcesforphotosynthesisandgrowth.

Wealsoobservedtemporalvariationinthegrowthrates,withhigherratesduringthe coldestandlowestLLmonths(November2016toMarch2017).Thispatternwasobserved atalldepths.Thisresultwasstrikingbecauseweoriginallythoughtthatcoralgrowth shouldhavebeenhigherduringthelatespring–earlysummermonthswhenenvironmental factorsaretypicallymild,andthestressesinducedbythesefactorshavenotbuiltup asmuchasduringlatesummer–earlyfall.Theseasonalgrowthpatternobservedhere alsocoincidedwithapreviousreportfromnaturallyoccurring A.cervicornis coralsatLa Parguera,PuertoRico[61].Arguably,theobservedseasonalgrowthpatterscouldbefurther linkedtoallocationofresources.Forinstance,thespring,andearlysummer,wherefemale gametesof A.cervicornis coralsdramaticallygainsize[62],andwatertemperatureand lightlevelsalsorises.Giventhenaturallyresourceconstraintof A.cervicornis,andthat, arguably,thisperiodmaybeofintenseresourceallocationintoreproductionandimmunity towithstandtheharshenvironmentalconditions,itwouldbereasonabletoexpectfewer resourceallocatedintogrowth.Thecontrarycouldbearguedduringthewinterseason, whencoralssignificantlyreduceresourceallocationintoreproductionandimmunitywhile increasingallocationsofresourcestowardsgrowth.

5.Conclusions

Ourfindingsprovideusefulinformationfor A.cervicornis coralfarmingpractitioners. Currently,mostcoralfarmslimittheiroperationstorelativelyshallowwaters.Ourresults, however,donotprovidestrongreasonstomovefarmsfromshallowtodeepwaters,given

theenvironmentalconditionsprevailingduringthestudyandthehighfarmingsuccess basedonthebenchmarksproposedby[44].Eventhoughdifferenceintemperatureamong depthswerestatisticallysignificant,fromabiologicalstandpoint,themagnitudeofthese variationsmaynotbesufficienttoinducetheobservedgrowthandmortalitydifferences amongdeeps.Nonetheless,fromaseasonalperspective,temperatureplaysaparamount role,asseasonalvariationintemperaturegreatlyinfluencesgrowthofcoralfragments[61]. Ontheotherhand,lightlevels,asmeasuredinthisstudy,mayhavenotbeenadequately measuredtoclearlydeterminedtherealeffectsoflight.Instead,recordingUVradiation wouldhavebeenabetterpredictorofsurvivalandgrowth.Nonetheless,thefactthatthe mortalityoffragmentswashigherinshallowerfarms,suggestthatlightlevels(asmeasured here),playsanimportantrole,bothatthedepthandseasonallevels.Nonetheless,underthe forecastedincreaseinextremeenvironmentalperturbationssuchashurricanes,maintaining farmsindeeperzonesmaypay-off.Forinstance,aftertheonslaughtofHurricaneIrma andMaríaacrossPuertoRicoin2017,Toledo-Hernandezetal.[63]andCarricketal.[64] reportedhigher A.cervicornis survivalwhenfragmentsweresetinfarmsat12m,as comparedtofragmentssetatshallowerareas.Infact,coralfragmentssetat8mand 5minwaterdeepfarmperishedtothehurricanes.Ourstudyalsodemonstratesthat fragmentoriginisanimportantfactortoconsiderwhencollectingsamples.Therefore,we recommendincludingasmanycollectionsitesaspossibletoensuredifferentialadaptability capacitiesamongthecollectedcoralindividuals.Italsoessentialtotrackthecolonies’ originwhilefollowingthemacrossthenursingperiod,selectingthosepopulationswith individualsowninghigheradaptabilitycapacitiesi.e.,highersurvivorshipandgrowth rates,forfuturerestorationprojects.Finally,knowingthatenvironmentalstressortocorals i.e.,temperatureandlightlevels,areattheirpickfromthelatespringtoearlyfall,itwould bebettertostartthefarmingduringlatefall–earlyspringwhencoralfragmentarefacing lessharmfulenvironmentalconditionsthanduringsummer.Thiswilloptimizethesurvival andgrowthoffragments,duringtheearlyandmostcriticalphaseoffarmingoperations.

AuthorContributions: Conceptualization,C.P.R.-D.andC.T.-H.;methodology,C.P.R.-D.,C.T.-H. andJ.L.S.-G.;software,C.P.R.-D.,J.L.S.-G.andB.B.;validation,C.P.R.-D.andB.B.;formalanalysis, C.P.R.-D.,C.T.-H.andB.B.;investigation,C.T.-H.,C.P.R.-D.,J.L.S.-G.andB.B.;writing—original draftpreparation,C.T.-H.andC.P.R.-D.;writing—reviewandediting,C.T.-H.,C.P.R.-D.andJ.L.S.-G.; visualization,C.P.R.-D.andJ.L.S.-G.;supervision,C.P.R.-D.andC.T.-H.;projectadministration,C.T.H.andC.P.R.-D.;fundingacquisition,C.T.-H.andC.P.R.-D.Allauthorshavereadandagreedtothe publishedversionofthemanuscript.

Funding: ThisresearchwasfundedbyFundaciónToyota,FordMotorCompanyFoundationof PuertoRico,theUniversityofPuertoRicoSeaGrantCollegeProgram(NOAAGrantnumber NA14OAR4170068,ProjectR-102-1-14).9December2021.

InstitutionalReviewBoardStatement: Notapplicable.

InformedConsentStatement: Notapplicable.

Acknowledgments: WethankPedroandNicolasGómez,PedroCarmona,José MéndezRojas,and FrancesGarcíafortheirfieldworkassistanceandalltheSAMandCESAMmembersbyhelpinthe stablishthecoralfarms.Also,wewanttothankDanyDavilaformapdesign,andAlexMercadoMolina,AlbertoSabatandHeatherMooreforcriticalreviewofthemanuscript.Finally,weliketo expressourgratitudetothereviewersandeditorfortheirdetailedrevision.

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.Thefundershadnoroleinthedesign ofthestudy;inthecollection,analyses,orinterpretationofdata;inthewritingofthemanuscript,or inthedecisiontopublishtheresults.

References

1. Gardner,T.A.;Côté,I.M.;Gill,J.A.;Grant,A.;Watkinson,A.R.Long-termregion-widedeclinesinCaribbeancorals. Science 2003, 301,958–960.[CrossRef][PubMed]

2. Lopéz-Peréz,A.;Culpul-Magananes,A.;Ahumada-Sempoal,A.;Medina-Rosas,P.;Reyes-Bonilla,H.;Herrero-Perézrul,M.D.; Reyes-Hernández,C.;Lara-Hernández,J.ThecoralcommunitiesoftheIslaMariasarchipelagoMexico;structureandbiogeographicrelevancetotheEasternPacific. Mar.Ecol. 2016, 37,679–690.[CrossRef]

3. Cramer,K.L.;Jackson,J.B.C.;Donovan,M.K.;Greenstein,B.J.;Korpanty,C.A.;Cook,G.M.;Pandolfi,J.M.Widespreadlossof Caribbeanacroporidcoralswasunderwaybeforecoralbleachinganddiseaseoutbreaks. Sci.Adv. 2020, 6,eaax9395.[CrossRef]

4. Pandolfi,J.M.;Bradbury,R.H.;Sala,E.;Hughes,T.P.;Bjorndal,K.A.;Cooke,R.G.;McAdle,D.;McClenachan,L.;Newman,M.J.H.; Paredes,G.;etal.Globaltrajectoriesofthelong-termdeclineofcoralreefecosystems. Science 2003, 301,955–958.[CrossRef]

5. Bellwood,D.R.;Hughes,T.P.;Folke,C.;Nyström,M.Confrontingthecoralreefcrisis. Nature 2004, 429,827–833.[CrossRef]

6. Miller,M.;Bourque,A.;Bohnsack,J.AnanalysisofthelossofacroporidcoralsatLooeKey,Florida,USA:1983–2000. CoralReefs 2002, 21,179–182.[CrossRef]

7. Heron,S.F.;Maynard,J.A.;vanHooidonk,R.;Eakin,C.M.WarmingtrendsandbleachingstressoftheWorld’scoralreefs 1985–2012. Sci.Rep. 2016, 6,38402.[CrossRef][PubMed]

8. Jokiel,P.L.;Coles,S.L.ResponseofHawaiianandotherIndo-PacificReefcoralstoelevatedtemperature. CoralReefs 1990, 8, 155–162.[CrossRef]

9. Reaser,J.K.;Pomerance,R.;Thomas,P.O.Coralbleachingandglobalclimatechange:Scientificfindingsandpolicyrecommendations. Conserv.Biol. 2000, 14,1500–1511.[CrossRef]

10. Frade,P.R.;Bongaerts,P.;Englebert,N.;Rogers,A.;González-Rivero,M.;Hoegh-Guldberg,O.DeepreefsoftheGreatBarrier Reefofferlimitedthermalrefugeduringmasscoralbleaching. Nat.Commun. 2018, 9,1–8.[CrossRef][PubMed]

11. Ruiz-Diaz,C.P.;Toledo-Hernández,C.;Sabat,A.M.;Marcano,M.Immuneresponsetoapathogenincorals. J.Theor.Biol. 2013, 332,141–148.[CrossRef]

12. Nieves-González,A.;Ruiz-Diaz,C.P.;Toledo-Hernández,C.;Ramírez-Lugo,J.S.Amathematicalmodeloftheinteractions between Acroporacervicornis anditsenvironment. Ecol.Model. 2019, 406,7–22.[CrossRef]

13. Keller,B.D.;Gleason,D.F.;McLeod,E.;Woodley,C.M.;Airame,S.;Causey,B.D.;Friedlander,A.M.;Grober-Dunsmore,R.G.; Johnson,J.E.;Miller,S.L.;etal.Climatechange,coralreefecosystems,andmanagementoptionsformarineprotectedareas. Environ.Manage. 2009, 44,1069–1088.[CrossRef]

14. Toledo-Hernández,C.;Yoshioka,P.;Bayman,P.;Sabat,A.Impactofdiseaseanddetachmentongrowthandsurvivorshipofsea fans Gorgoniaventalina Mar.Ecol.Progr.Ser. 2009, 393,47–54.[CrossRef]

15. O’Donnell,K.E.;Lohr,K.E.;Bartels,E.;Patterson,J.T.Evaluationofstaghorncoral(Acroporacervicornis,Lamarck1816)production techniquesinanocean-basednurserywithconsiderationofcoralgenotype. J.Exp.Mar.Bio.Ecol. 2017, 487,53–58.[CrossRef]

16. Goreau,T.F.;Goreau,N.I.CoralReefProject-PapersinmemoryofDr.ThomasF.Goreau.17.TheEcologyofJamaicanReefs.II. Geomorphology,Zonation,andSedimentaryPhases. Bull.Mar.Sci. 1973, 23,399–464.

17. Mercado-Molina,A.E.;Ruiz-Diaz,C.P.;Sabat,A.M.Branchingdynamicsoftransplantedcoloniesofthethreatenedcoral Acropora cervicornis:Morphogenesis,complexity,andmodeling. J.Exp.Mar.Biol.Ecol. 2016, 482,134–141.[CrossRef]

18. Bruckner,A.W. ProceedingoftheCaribbeanAcroporaWorkshop:PotentialApplicationoftheU.S.EndangeredSpeciesActasaConservation Strategy;NOAATechnicalMemorandumNMFS-OPR:SliverSpring,MD,USA,2002;199p.

19. Graham,N.A.J.;Nash,K.L.Theimportanceofstructuralcomplexityincoralreefecosystems. CoralReefs 2003, 32,315–326.[CrossRef]

20. Yanovski,R.;Nelson,P.A.;Abelson,A.StructuralComplexityinCoralReefs:ExaminationofaNovelEvaluationToolonDifferent SpatialScales. Front.Ecol.Evol. 2017, 5,27.[CrossRef]

21. Jackson,J.;Donovan,M.;Cramer,K.;Lam,V. StatusandTrendsofCaribbeanCoralReefs1970–2012;GlobalCoralReefMonitoring Network,IUCN:Gland,Switzerland,2014.

22. Aronson,R.B.;Precht,W.F.White-banddiseaseandthechangingfaceofCaribbeancoralreefs. Hydrobiologia 2001, 460,25–38.[CrossRef]

23. Goergen,E.A.;Ostroff,Z.;Gilliam,D.S.Genotypeandattachmenttechniqueinfluencethegrowthandsurvivaloflinenursery corals. Restor.Ecol. 2017, 26,622–628.[CrossRef]

24. Young,C.N.;Schopmeyer,S.A.;Lirman,D.Areviewofreefrestorationandcoralpropagationusingthethreatenedgenus Acropora intheCaribbeanandWesternAtlantic. Bull.Mar.Sci. 2012, 88,1075–1098.[CrossRef]

25. Lirman,D.;Schopmeyer,S.;Galvan,V.;Drury,C.;Baker,A.C.;Baums,I.B.GrowthDynamicsoftheThreatenedCaribbean StaghornCoral Acroporacervicornis:InfluenceofHostGenotype,SymbiontIdentity,ColonySize,andEnvironmentalSetting. PLoSONE 2014, 9,e107253.[CrossRef]

26. Mercado-Molina,A.;Ruiz-Diaz,C.P.;Sabat,A.M.Demographicsanddynamicsoftworestoredpopulationsofthethreatened reef-buildingcoral Acroporacervicornis J.Nat.Conserv. 2015, 24,17–23.[CrossRef]

27. Rinkevich,B.Restorationstrategiesforcoralreefsdamagedbyrecreationalactivities:Theuseofsexualandasexualrecruits. Rest. Ecol. 1995, 3,241–251.[CrossRef]

28. Shaish,L.;Levy,G.;Gomez,E.;Rinkevich,B.FixedandsuspendedcoralnurseriesinthePhilippines:Establishingthefirststepin thegardeningconceptofreefrestoration. J.Exp.Mar.Biol.Ecol. 2008, 358,86–97.[CrossRef]

29. Levy,G.;Shaish,L.;Haim,A.;Rinkevich,B.Mid-waterropenursery-testingdesignandperformanceofanovelreefrestoration instrument. Ecol.Eng. 2010, 36,560–569.[CrossRef]

30. Baums,I.B.;Baker,A.C.;Davies,W.S.;Grottoli,A.G.;Kenkel,C.D.;Kitchen,S.A.;Kuffner,I.B.;LaJeunesse,T.C.;Matz,M.V.; Miller,M.W.;etal.ConsiderationsformaximizingtheadaptivepotentialofrestoredcoralpopulationsinthewesternAtlantic. Ecol.Appl. 2019, 29,e01978.[CrossRef][PubMed]

31. Shafir,S.;Abady,S.;Rinkevich,B.Improvedsustainablemaintenanceformid-watercoralnurserybytheapplicationofanantifoulingagent. J.Exp.Mar.Biol.Ecol. 2009, 368,124–128.[CrossRef]

32. Griffin,S.;Spathias,H.;Moore,T.;Baums,I.;Griffin,B.A.Scalingup Acropora nurseriesintheCaribbeanandimproving techniques.InProceedingsofthe12thInternationalCoralReefSymposio,Cairns,Australia,9–13July2012.

33. Putchim,L.;Thongtham,N.;Hewett,A.;Chansang,H.Survivalandgrowthof Acropora spp.in-waternurseryandafter transplantationatPhiPhiIslands,AndamanSeaThailand.InProceedingsofthe11thInternationalCoralReefSymposium,Fort Lauderdale,FL,USA,7–11July2008.

34. Foo,S.A.;Asner,G.P.Seasurfacetemperatureincoralreefrestorationoutcomes. Environ.Res.Lett. 2020, 15,074045.[CrossRef]

35. Bridge,T.C.L.;Hoey,A.S.;Campbell,S.J.;Muttaqin,E.;Rudi,E.;Fadli,N.;Baird,A.H.Depth-dependentmortalityofreefcorals followingaseverebleachingevent:Implicationsforthermalrefugesandpopulationrecovery[version3;peerreview:2approved, 1approvedwithreservations]. F1000Research 2014, 2,187.[CrossRef]

36. Enochs,I.C.;Manzello,D.P.;Carlton,R.;Schopmyeyer,S.;vanHooidonk,R.;Lirman,D.Effectsoflightandelevated pCO2 onthe growthandphotochemicalefficiencyof Acroporacervicornis CoralReefs 2014, 33,477–485.[CrossRef]

37. Therneau,T.M.;Grambsch,P.M. ModelingSurvivalData:ExtendingtheCoxModel;Springer:NewYork,NY,USA,2000; ISBN0-387-98784-3.

38. Kohler,K.E.;Gill,S.M.CoralPointCountwithExcelextensions(CPCe):AVisualBasicprogramforthedeterminationofcoral andsubstratecoverageusingrandompointcountmethodology. Comput.Geosci. 2006, 32,1259–1269.[CrossRef]

39. Kuznetsova,A.;Brockhoff,P.B.;Christensen,R.H.B.lmerTestPackage:TestsinLinearMixedEffectsModels. J.Stat.Softw. 2017, 82,1–26.[CrossRef]

40. RCoreTeam. R:ALanguageandEnvironmentalforStatisticalComputing;RFoundationforStatisticalComputing:Vienna,Austria,2014.

41. Rowan,R.;Knowlton,N.;Baker,A.C.;Baker,A.;Jara,J.Landscapeecologyofalgalsymbiontscreatesvariationinepisodesof coralbleaching. Nature 1997, 388,265–269.[CrossRef][PubMed]

42. Marshall,P.A.;Baird,A.H.BleachingofcoralsontheGreatBarrierReef:Differentialsusceptibilitiesamongtaxa. CoralReefs 2000, 19,155–163.[CrossRef]

43. Morais,J.;Santos,B.A.LimitedpotentialofdeepreefstoserveasrefugesfortropicalsouthwesternAtlanticcorals. Ecosphere 2018, 9,e02281.[CrossRef]

44. Schopmeyer,S.A.;Lirman,D.;Bertels,E.;Gilliem,D.S.;Goergen,E.A.;Griffin,S.P.;Johnson,M.E.;Lustic,C.;Maxwell,K.;Walter, C.S.Regionalrestorationbenchmarksfor Acroporacervicornis CoralReefs 2017, 36,1047–1057.[CrossRef]

45. Muir,P.R.;Marshall,P.A.;Abdulla,A.;Aguirre,J.D.;Muir,P.R.Speciesidentityanddepthpredictbleachingseverityin reef-buildingcorals:Shallthedeepinheritthereef? Proc.R.Soc.B 2017, 284,20171551.[CrossRef]

46. Riegl,B.;Piller,W.E.Possiblerefugiaforreefsintimesofenvironmentalstress. Int.J.Earth.Sci. 2003, 92,520–531.[CrossRef]

47. Glynn,P.W.Coralreefbleaching:Facts,hypotheses,andimplications. Glob.Chang.Biol. 1996, 2,495–509.[CrossRef]

48. Palmer,C.V.;Traylor-Knowles,N.Towardsanintegratednetworkofcoralimmunemechanisms. Proc.R.Soc.BBiol.Sci. 2012, 279,4106–4114.[CrossRef][PubMed]

49. Drury,C.;Manzello,D.;Lirman,D.Genotypeandlocalenvironmentdynamicallyinfluencegrowth,disturbanceresponseand survivorshipinthethreatenedcoral, Acroporacervicornis PLoSONE 2017, 12,e0174000.[CrossRef][PubMed]

50. Quinn,N.J.;Kojis,B.L.EvaluationgthepotentialofnaturalpreproductionadnarticicaltechniquestoincreaseAcroporacervicornis populationatDiscoveryBay,Jamaica. Rev.Biol.Trop. 2010, 54,105–116.

51. Bowden-Kerby,A.;Quinn,N.;Stennet,M.;Mejia,A. Acroporacervicornis RestorationtoSupportCoralReefConservationinthe Caribbean. NOAACoast.Zone 2012, 5,7–10.

52. Hackerrott,S.;Martell,H.A.;Eirin-López,J.M.Coralenvironmentalmemory:Causes,mechanisms,andconsequencesforfuture reefs. TrendsEcol.Evol. 2021, 36,1011–1016.[CrossRef]

53. Baker,P.A.;Weber,J.N.Coralgrowthrate:Variationwithdepth. EarthPlanet.Sci.Lett. 1975, 27,57–61.[CrossRef]

54. Budd,A.F.;Fukami,H.;Smith,N.D.;Knowlton,N.TaxonomicclassificationofthereefcoralfamilyMussidae(Cnidaria:Anthozoa: Scleractinia). Zool.J.Linn.Soc. 2012, 166,465–529.[CrossRef]

55. Highsmith,R.C.Coralgrowthratesandenvironmentalcontrolofdensitybanding. J.Exp.Mar.Biol.Ecol. 1979, 37,105–125.[CrossRef]

56. Huston,M.VariationincoralgrowthrateswithdepthatDiscoveryBay,Jamaica. CoralReefs 1985, 4,19–25.[CrossRef]

57. Kinzie,R.A.,III.ThezonationofWestInidangorgonians. Bull.Mar.Sci. 1973, 23,93–155.

58. Birkeland,C.Theimportanceofrateofbiomassaccumulationinearlysuccessionalstageofbenthiccommunitiestothesurvival ofcoralrecruit.InProceedingsoftheThirdInternationalCoralReefSymposium,Miami,FL,USA,1January1977;Universityof Miami:Miami,FL,USA;Volume1,pp.5–21.

59. Kahng,S.E.;Watanabe,T.K.;Hu,H.M.;Watanabe,T.;Shen,C.C.Moderatezooanthellatecoralgrowthratesinthelowerphotic zone. CoralReef 2020, 39,1273–1284.[CrossRef]

60. Torres,J.L.;Armstrong,R.A.;Corredor,J.E.;Gilbes,F.PhysiologicalResponsesofAcroporacervicornistoIncreasedSolar Irradiance. Photochem.Photobiol. 2007, 83,839–850.[CrossRef][PubMed]

61. Weil,E.;Hammerman,N.M.;Becicka,R.L.;Cruz-Motta,J.J.Growthdynamicsin Acroporacervicornis andA.proliferainsouthwest PuertoRico. PeerJ 2020, 8,e8435.[CrossRef][PubMed]

62. Bernardo,V.-A.;Colley,S.B.;Hoke,S.M.;Thomas,J.D.ThereproductiveseasonalityandgametogeniccycleofAcroporacervicornis offBrowardCounty,Florida,USA. CoralReefs 2006, 25,110–122.

63. Toledo-Hernández,C.;Ruiz-Díaz,C.P.;Hernández-Delgado,E.;Suelimán,S.Devastationof15-yearoldcommunity-basedcoral farmingandreefrestorationsitesinPuertoRicobymajorHurricanesIrmaandMaría. Carb.Nat. 2018, 53,1–6.

64. Carrick,J.;Lustic,C.;Lirman,D.;Schopmeyer,S.;Bartels,E.;Burdeno,D.;Dahlgren,C.;Galvan,V.M.;Gilliam,D.;Goergen,L.; etal.HurricaneImpactsonReefRestoration:TheGood,BadandtheUgly.In ActivateCoralRestoration,TechniquesforaChanging Planet,1sted.;Vaughan,D.E.,Ed.;J.RossPublishing:FortLauderdale,FL,USA,2021;Volume1,pp.483–510.